Interstate Slave Trade on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

, &c. They were like Haley, they meant to repent when they got through."

The internal slave trade in the United States, also known as the domestic slave trade, the Second Middle Passage and the interregional slave trade, was the mercantile trade of

At the same time, the invention of the

At the same time, the invention of the

The transatlantic slave trade was not prohibited under federal law until 1808. Imports from Africa to Southern states were ongoing from 1776 until that time, most often through the ports of Charleston and

The transatlantic slave trade was not prohibited under federal law until 1808. Imports from Africa to Southern states were ongoing from 1776 until that time, most often through the ports of Charleston and

In their day, slave traders were called everything from ''broker'', the generic term favored in Charleston, to ''nigger-trader'' (sometimes transcribed as ''niggah-tradah''), a term that appears in both slave traders' own descriptions of themselves in oral interviews and in records of African-American folk music of the era. ''Negro trader'', ''negro speculator'', and ''slave dealer'' were common occupational titles that appeared in census records and city directories. Anti-slavery activists called them ''soul drivers''. Slaves sometimes spoke of the ''Georgia-man'' who would take them away to, if not the geographical

In their day, slave traders were called everything from ''broker'', the generic term favored in Charleston, to ''nigger-trader'' (sometimes transcribed as ''niggah-tradah''), a term that appears in both slave traders' own descriptions of themselves in oral interviews and in records of African-American folk music of the era. ''Negro trader'', ''negro speculator'', and ''slave dealer'' were common occupational titles that appeared in census records and city directories. Anti-slavery activists called them ''soul drivers''. Slaves sometimes spoke of the ''Georgia-man'' who would take them away to, if not the geographical

, enslaved people

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

within the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

. It was most significant after 1808, when the importation of slaves from Africa was prohibited by federal law. Historians estimate that upwards of one million slaves were forcibly relocated from the Upper South

The Upland South and Upper South are two overlapping cultural and geographic subregions in the inland part of the Southern United States. They differ from the Deep South and Atlantic coastal plain by terrain, history, economics, demographics, ...

, places like Maryland, Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Missouri, to the territories and states of the Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion of the Southern United States. The term is used to describe the states which were most economically dependent on Plantation complexes in the Southern United States, plant ...

, especially Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Texas.

Economists say that transactions in the inter-regional slave market were driven primarily by differences in the marginal productivity of labor, which were based in the relative advantage between climates for the production of staple goods. The trade was strongly influenced by the invention of the cotton gin

A cotton gin—meaning "cotton engine"—is a machine that quickly and easily separates cotton fibers from their seeds, enabling much greater productivity than manual cotton separation.. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (); ...

, which made short-staple cotton profitable for cultivation across large swathes of the upland Deep South (the Black Belt). Previously the commodity was based on long-staple cotton cultivated in coastal areas and the Sea Islands

The Sea Islands are a chain of over a hundred tidal and barrier islands on the Atlantic Ocean coast of the Southeastern United States, between the mouths of the Santee and St. Johns rivers along South Carolina, Georgia and Florida. The la ...

.

The disparity in productivity created arbitrage opportunities for traders to exploit, and it facilitated regional specialization in labor production. Due to a lack of data, particularly with regard to slave prices, land values, and export totals for slaves, the true effects of the domestic slave trade, on both the economy of the Old South and general migration patterns of slaves into southwest territories, remain uncertain. These have served as points of contention among economic historians. The physical effect of forced labor (on remote plantation camps plagued with yellow fever, cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

, and malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

), and social-emotional effect of family separation in American slavery, was nothing short of catastrophic.

History

The history of the domestic slave trade can very clumsily be divided into three major periods: * 1776 to 1808: This period began with theDeclaration of Independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

and ended when the importation of slaves from Africa and the Caribbean was prohibited under federal law in 1808; the importation of slaves was prohibited by the Continental Congress during the American Revolutionary War but resumed locally afterwards, primarily through the ports of Wilmington, North Carolina

Wilmington is a port city in New Hanover County, North Carolina, United States. With a population of 115,451 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of municipalities in North Carolina, eighth-most populous city in the st ...

(until 1785), Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Brita ...

(until 1798), and Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the List of municipalities in South Carolina, most populous city in the U.S. state of South Carolina. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint of South Carolina's coastline on Charleston Harbor, an inlet of the Atla ...

(reopened the transatlantic slave trade in December 1803 and imported 39,075 enslaved people of African descent between 1804 and 1808). Some slaves shipped to these ports were resold locally, others were forwarded on the Natchez Natchez may refer to:

Places

* Natchez, Alabama, United States

* Natchez, Indiana, United States

* Natchez, Louisiana, United States

* Natchez, Mississippi, a city in southwestern Mississippi, United States

** Natchez slave market, Mississippi

* ...

and New Orleans slave markets of the lower Mississippi.

* 1808 to Indian removal and invention of long-staple cotton gin (1830s): This period of national expansion can arguably be backdated to the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase () was the acquisition of the Louisiana (New France), territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. This consisted of most of the land in the Mississippi River#Watershed, Mississipp ...

of 1803, and includes the cession of Spanish West Florida

Spanish West Florida ( Spanish: ''Florida Occidental'') was a province of the Spanish Empire from 1783 until 1821, when both it and East Florida were ceded to the United States.

The region of West Florida initially had the same borders as the e ...

in 1821. In the years immediately following the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

, the most active slave markets in the deep South were at Algiers, Louisiana

Algiers () is a historic neighborhood of New Orleans and is the only Orleans Parish community located on the West Bank of the Mississippi River. Algiers is known as the 15th Ward, one of the 17 Wards of New Orleans. It was once home to many jaz ...

, and Natchez, Mississippi

Natchez ( ) is the only city in and the county seat of Adams County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 14,520 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Located on the Mississippi River across from Vidalia, Louisiana, Natchez was ...

. One New Orleans historian found evidence of that the "queen of the trade", as New Orleans was later known, was open for business in the first years of the 19th century, but "it was not till the 1820s had well set in that the number of American slave merchants grew to impressive proportions" and by 1827 "New Orleans had become the chief center of the slave trade in the lower South"

* 1830s to American Civil War: This period began when the combination of new lands open for settlement and higher profits for cotton growers led to a massive population transfer of enslaved people from the Chesapeake region to the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

basin. This era also saw the rise of the ever-more vocal and organized abolitionist movement in the United States, as chronicled and publicized by journals like '' The Liberator'', which was established in 1831.

End of the slave trade

The domestic slave trade wilted during American Civil Warthere was a measurable price drop between 1860 and 1862, due to "market uncertainty" discouraging speculators. In May 1861, a "Southern Mississippian" who seemed to oppose secession even though "no man in Mississippi has a larger proportion of his property in negroes" wrote the ''Louisville Courier'' that "The secessionists are carrying out the principles and wishes of the abolitionists. Likely negroes could not be sold here at $500 in good money. Negro traders are as scarce here as in Boston." Still, the business remained brisk and prices rose in the protected interior of the CSA, and according to historian Robert Colby, "Confederates nevertheless interpreted the health of the slave trade as embodying that of their nation." Times got still harder for traders when theUnion blockade

The Union blockade in the American Civil War was a naval strategy by the United States to prevent the Confederate States of America, Confederacy from trading.

The blockade was proclaimed by President Abraham Lincoln in April 1861, and required ...

and total U.S. military control of the Mississippi River prevented the trafficking of people from, say, rural Missouri to New Orleans. But the slave trade, as an integral part of slavery, persisted throughout Confederate-controlled territory until very nearly the end of the war. Ziba B. Oakes was still listing slaves in Charleston, South Carolina newspaper ads in November 1864. A handful of American-flagged ships were still moving enslaved people from Africa to Cuba and Brazil until 1867, when American participation in the slave trade ended once and for all.

Economics

Slavery was a massive element of the U.S. national economy and even more so the economy of the South: "In 1860, enslaved people were worth more than $3 billion (~$ in ) to their owners. In today's economy, that would be equivalent to $12.1 trillion or 67 percent of the 2015 U.S. gross domestic product...The unpaid fruits of their labors created an interest so strong that between 1861 and 1865, Confederate leaders staked hundreds of thousands of lives and the future of their civilization on it." As told by historianFrederic Bancroft

Frederic Bancroft (October 30, 1860, in Galesburg, Illinois – February 22, 1945) was an American historian, author, and librarian. The Bancroft Prize, one of the most distinguished academic awards in the field of history, was established at Co ...

, "Slave trading was considered a sign of enterprise and prosperity."

The internal slave trade among colonies emerged in 1760 as a source of labor in early America. It is estimated that between 1790 and 1860 approximately 835,000 slaves were relocated to the American South.

The biggest sources for the domestic slave trade were "exporting" states in the Upper South, especially Virginia and Maryland, and as well as Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Missouri. From these states most slaves were imported into the Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion of the Southern United States. The term is used to describe the states which were most economically dependent on Plantation complexes in the Southern United States, plant ...

, to the "slave-consuming states," especially Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. Robert Fogel

Robert William Fogel (; July 1, 1926 – June 11, 2013) was an American economic historian and winner (with Douglass North) of the 1993 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. As of his death, he was the Charles R. Walgreen Distinguished Se ...

and Stanley Engerman

Stanley Lewis Engerman (March 14, 1936 – May 11, 2023) was an American economist and economic historian. He was known for his quantitative historical work along with Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert Fogel. His first major book, co-authored ...

attribute the larger proportion of the slave migration due to planters who relocated their entire slave populations to the Deep South to develop new plantations or take over existing ones. Walter Johnson

Walter Perry Johnson (November 6, 1887 – December 10, 1946), nicknamed "Barney" and "the Big Train", was an American professional baseball player and Manager (baseball), manager. He played his entire 21-year baseball career in Major League Ba ...

disagrees, finding that only one-third of the population movement south was due to wholesale relocation of slave owner and chattel, while the other two-thirds of the shift was due to the commerce in slaves.

Contributing factors

Soil exhaustion and crop changes

Historians who argue in favor of soil exhaustion as an explanation for slave importation into the Deep South posit that exporting states emerged as slave producers because of the transformation of agriculture in the Upper South. By the late 18th century, the coastal and Piedmont tobacco areas were being converted to mixed crops because of soil exhaustion and changing markets. Because of the deterioration of soil and an increase in demand for food products, states in the upper South shifted crop emphasis from tobacco to grain, which required less labor. This decreased demand left states in the Upper South with an excess supply of labor.Land availability from Indian removal

With the forced Indian removal by the US making new lands available in the Deep South, there was much higher demand there for workers to cultivate the labor-intensive sugar cane and cotton crops. The extensive development of cotton plantations created the highest demand for labor in the Deep South.Cotton gin

At the same time, the invention of the

At the same time, the invention of the cotton gin

A cotton gin—meaning "cotton engine"—is a machine that quickly and easily separates cotton fibers from their seeds, enabling much greater productivity than manual cotton separation.. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (); ...

in the late 18th century transformed short-staple cotton into a profitable crop that could be grown inland in the Deep South. Settlers pushed into the South, expelling the Five Civilized Tribes

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by the United States government in the early federal period of the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast: the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Cr ...

and other Native American groups. The cotton market had previously been dominated by the long-staple cotton cultivated primarily on the Sea Islands

The Sea Islands are a chain of over a hundred tidal and barrier islands on the Atlantic Ocean coast of the Southeastern United States, between the mouths of the Santee and St. Johns rivers along South Carolina, Georgia and Florida. The la ...

and in the coastal South Carolina Lowcountry

The Lowcountry (sometimes Low Country or just low country) is a geographic and cultural region along South Carolina's coast, including the Sea Islands. The region includes significant salt marshes and other coastal waterways, making it an impor ...

. The consequent boom in the cotton industry, coupled with the labor-intensive nature of the crop, created a need for slave labor in the Deep South that could be satisfied by excess supply further north.

The increased demand for labor in the Deep South pushed up the price of slaves in markets such as New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

, which became the fourth-largest city in the country based in part on profits from the slave trade and related businesses. The price differences between the Upper and Deep South created demand. Slave traders took advantage of this arbitrage opportunity by buying at lower prices in the Upper South and then selling slaves at a profit after taking or transporting them further south. Some scholars believe there was an increasing prevalence in the Upper South of "breeding" slaves for export. The proven reproductive capacity of enslaved women was advertised as selling point and a feature that increased value.

Resolve financial deficits

Although not as significant as the exportation of slaves to Deep South, farmers and land owners who needed to pay off loans increasingly used slaves as a cash substitute. This had also contributed to the growth of the internal slave trade.Statistics

Economic historians have offered estimates for the annual revenue generated by the inter-regional slave trade for exporters that range from $3.75 to $6.7 million. The demand for prime-aged slaves, from the ages of 15 to 30, accounted for 70 percent of the slave population relocated to the Deep South. Since the ages of slaves were often unknown by the traders themselves, physical attributes such as height often dictated demand in order to minimize asymmetric information.

Robert Fogel

Robert William Fogel (; July 1, 1926 – June 11, 2013) was an American economic historian and winner (with Douglass North) of the 1993 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. As of his death, he was the Charles R. Walgreen Distinguished Se ...

and Stanley Engerman

Stanley Lewis Engerman (March 14, 1936 – May 11, 2023) was an American economist and economic historian. He was known for his quantitative historical work along with Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert Fogel. His first major book, co-authored ...

estimated that the slave trade accounted for 16 percent of the relocation of enslaved African Americans, in their work ''Time on the Cross

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to compa ...

''. This estimate, however, was severely criticized for the extreme sensitivity of the linear function used to gather this approximation. A more recent estimate, given by Jonathan B. Pritchett, has this figure at about 50 percent, or about 835,000 slaves total between 1790 and 1850. Without the inter-regional slave trade, it is possible that forced migration of slaves would have occurred naturally due to natural population pressures and the subsequent increase in land prices. In 1965, William L. Miller contended that, "it is even doubtful whether the interstate slave traffic made a net contribution to the westward flow of the population." Historian Charles S. Sydnor wrote in 1933, "The number of slaves brought into Mississippi either by slavetraders or by immigrant masters cannot be precisely stated." Robert Gudmestad found that "Disentangling the various strands of forced migration is like trying to untie the Gordian knot

The cutting of the Gordian Knot is an Ancient Greek legend associated with Alexander the Great in Gordium in Phrygia, regarding a complex knot that tied an oxcart. Reputedly, whoever could untie it would be destined to rule all of Asia. In 33 ...

. Migration with owners, planter purchase, and the interstate trade blended together to form a seamless whole."

Importation, piracy, and interstate kidnapping

The transatlantic slave trade was not prohibited under federal law until 1808. Imports from Africa to Southern states were ongoing from 1776 until that time, most often through the ports of Charleston and

The transatlantic slave trade was not prohibited under federal law until 1808. Imports from Africa to Southern states were ongoing from 1776 until that time, most often through the ports of Charleston and Savannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) biome and ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach th ...

. Imports to Cuba, Brazil, and America often involved similar personnel and practices. Post-1808 importation of slaves to the United States

The importation of slaves from overseas to the United States was prohibited in 1808, but criminal trafficking of enslaved people on a smaller scale likely continued for many years. The most intensive periods of piracy were in the 1810s, before ...

from the Caribbean, South America, and Africa was illegal but piracy continued until the opening of the American Civil War. Piracy was most active in the 1810s, with New Orleans and Amelia Island off Spanish Florida being key centers, and in the 1850s, when pro-slavery activists sought to drive down slave prices by illegally importing directly from Africa.

Kidnapping into slavery in the United States

The pre-American Civil War practice of kidnapping into slavery in the United States occurred in both free and slave states, and both fugitive slaves and free negroes were transported to slave markets and sold, often multiple times. There wer ...

was an ongoing issue. Unaccompanied children and people of color traveling to port cities and border states were particularly vulnerable. There are multiple accounts of armed gangs breaking into the homes of free people in the dead of night and carrying away whole families. The lucky ones were sometimes redeemed from the local slave jail by friends or lawyers before they were shipped south.

Breeding of slave children for sale

According toFrederic Bancroft

Frederic Bancroft (October 30, 1860, in Galesburg, Illinois – February 22, 1945) was an American historian, author, and librarian. The Bancroft Prize, one of the most distinguished academic awards in the field of history, was established at Co ...

in ''Slave-Trading in the Old South

''Slave-Trading in the Old South'' by Frederic Bancroft, an independently wealthy freelance historian, is a classic history of domestic slave trade in the antebellum United States. Among other things, Bancroft discredited the assertions, then c ...

'' (1931) young female slaves were also considered an excellent financial investment: "Not only real estate, but also stocks, bonds and all other personal property were little prized in comparison with slaves...Absurd as it now seems, slaves, especially girls and young women, because of prospective increase, were considered the best investment for persons of small means."

Profits

Irish economic theorist John Elliot Cairnes suggested in his work ''The Slave Power'' that the inter-regional slave trade was a major component in ensuring the economic vitality of the Old South. Many economic historians, however, have since refuted the validity of this point. The general consensus seems to support Professor William L. Miller's claim that the inter-regional slave trade "did not provide the major part of the income of planters in the older states during any period." The returns gained by traders from the sale price of slaves were offset by both the fall in the value of land, that resulted from the subsequent decrease in the marginal productivity of land, and the fall in the price of output, which occurred due to the increase in market size as given by westward expansion. Kotlikoff suggested that the net effect of the inter-regional slave trade on the economy of the Old South was negligible, if not negative. The profits realized through the sale and shipment of enslaved people were in turn reinvested in banking, railroads, and even colleges. A striking example of the connection between the domestic slave trade and higher education can be found in the 1838 sale of 272 slaves by the MarylandJesuits

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

to Louisiana; a small portion of the proceeds of the sale was used to pay down the debts of Georgetown College

Georgetown College is a private Christian liberal arts college in Georgetown, Kentucky. Chartered in 1829, Georgetown was the first Baptist college west of the Appalachian Mountains.

The college offers over 40 undergraduate degrees and a Mas ...

. Caroline Donovan endowed a chair at Johns Hopkins

Johns Hopkins (May 19, 1795 – December 24, 1873) was an American merchant, investor, and philanthropist. Born on a plantation, he left his home to start a career at the age of 17, and settled in Baltimore, Maryland, where he remained for mos ...

in 1889 using part of the fortune accumulated by her late husband, Baltimore trader Joseph S. Donovan

Joseph S. Donovan (April 20, 1800 – April 15, 1860) was an List of American slave traders, American slave trader known for his slave jails in Baltimore, Maryland. Donovan was a major participant in the Slave trade in the United States, interreg ...

.

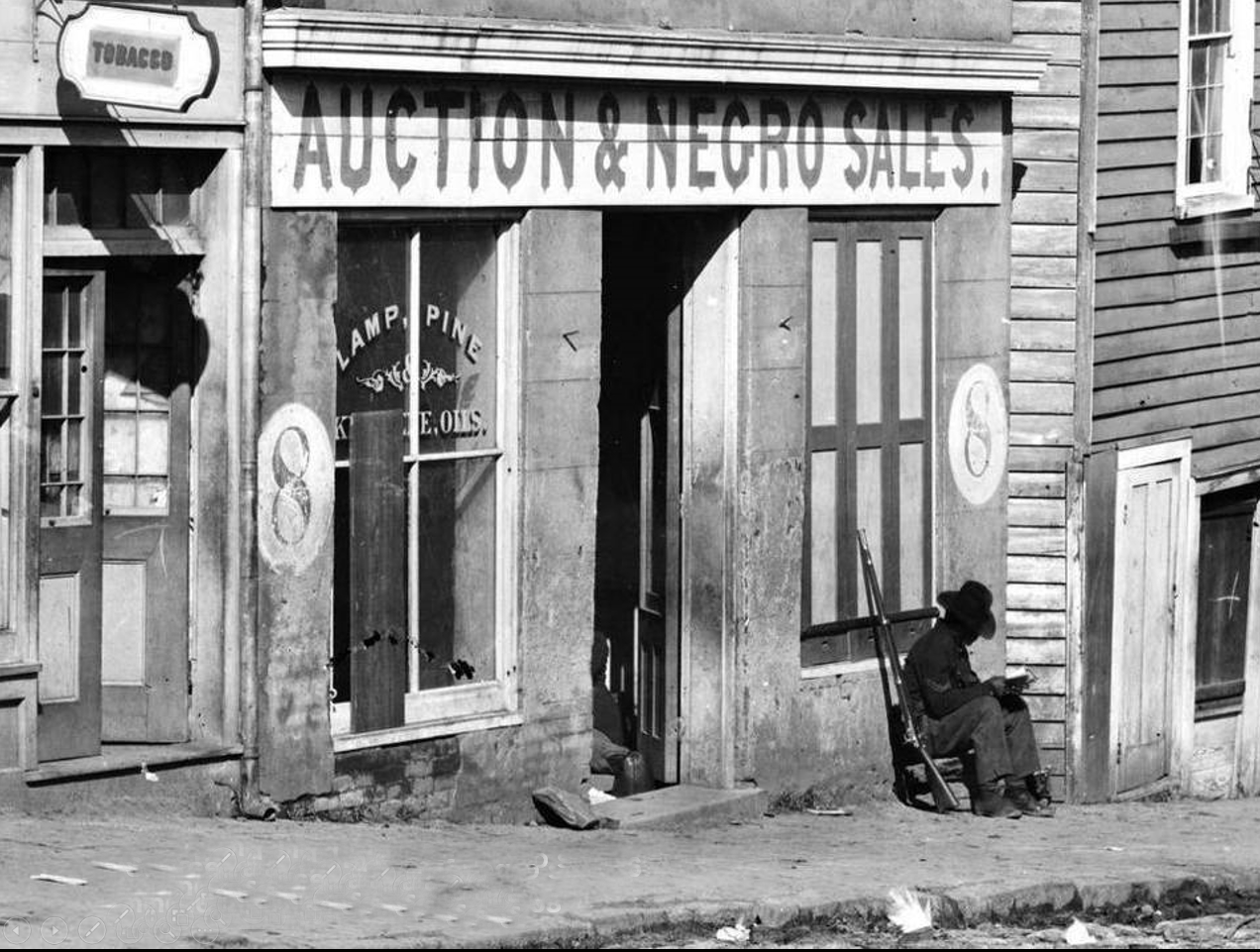

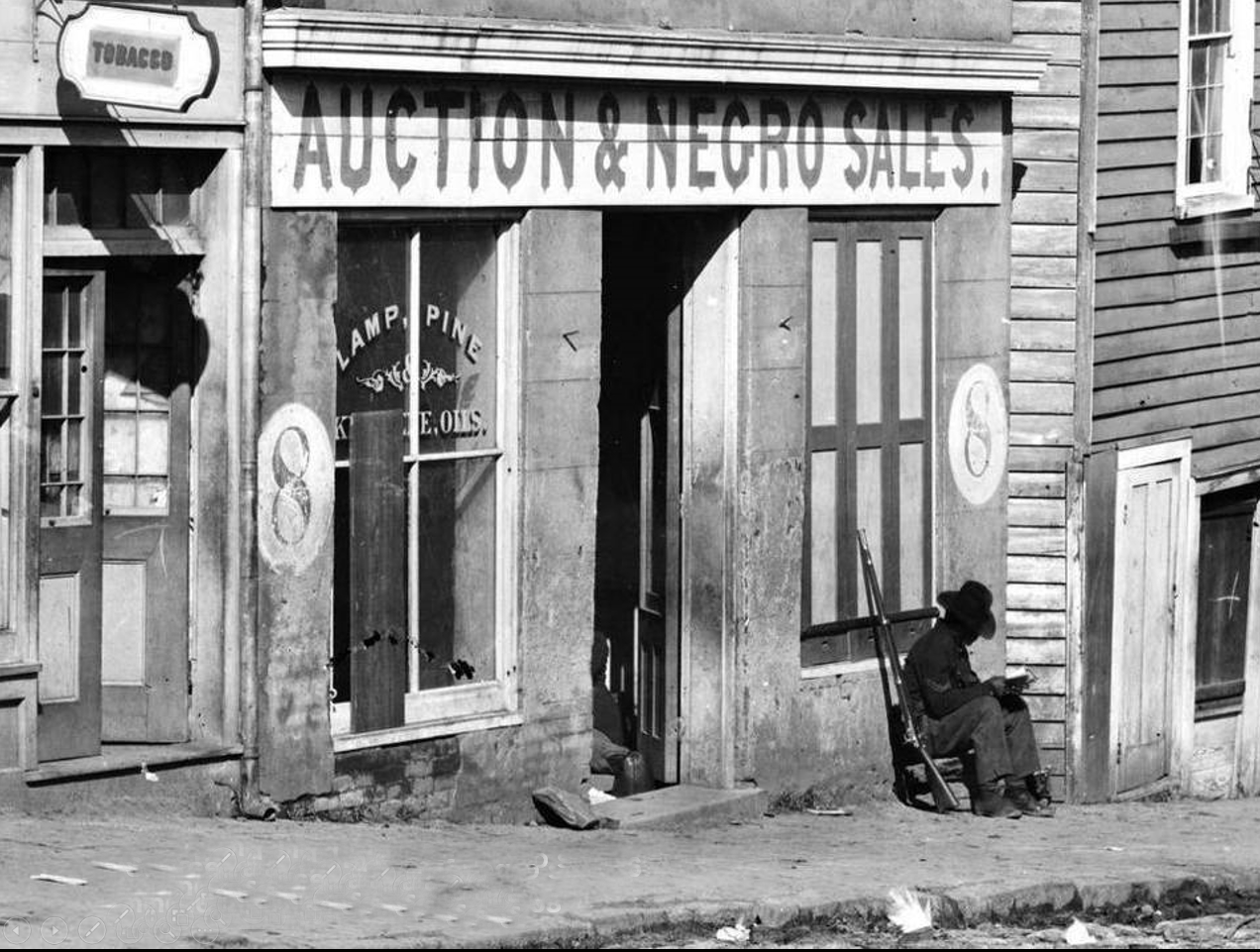

Markets and traders

In their day, slave traders were called everything from ''broker'', the generic term favored in Charleston, to ''nigger-trader'' (sometimes transcribed as ''niggah-tradah''), a term that appears in both slave traders' own descriptions of themselves in oral interviews and in records of African-American folk music of the era. ''Negro trader'', ''negro speculator'', and ''slave dealer'' were common occupational titles that appeared in census records and city directories. Anti-slavery activists called them ''soul drivers''. Slaves sometimes spoke of the ''Georgia-man'' who would take them away to, if not the geographical

In their day, slave traders were called everything from ''broker'', the generic term favored in Charleston, to ''nigger-trader'' (sometimes transcribed as ''niggah-tradah''), a term that appears in both slave traders' own descriptions of themselves in oral interviews and in records of African-American folk music of the era. ''Negro trader'', ''negro speculator'', and ''slave dealer'' were common occupational titles that appeared in census records and city directories. Anti-slavery activists called them ''soul drivers''. Slaves sometimes spoke of the ''Georgia-man'' who would take them away to, if not the geographical Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

, an allegorical "Georgia," elsewhere in the cotton and sugar lands far south from where they were raised.

In the earliest years of the market, "dozens of independent speculators...bought lots of ten or so slaves, generally on credit, in Upper-South states like Virginia and Maryland." In 1836 a Philadelphia paper characterized the work of negro brokers: "They conceive the business of pawn brokers and merchandize brokers. They lend money on the security of slaves, taking the latter as a pledge, to be sold if the pledge be not redeemed. They advance cash on slaves to be sold at auction or private sale, deducting from the proceeds of sale their commission and expenses. They buy and sell slaves upon commission, to suit their customers, and sometimes doubtless, buy and sell free people of color on pretence of their being slaves."

The argument has been made that the domestic slave trade was one that resulted in "superprofits" for traders. But Jonathan Pritchett points to evidence that there were a significant number of firms engaged in the market, a relatively dense concentration of these firms, and low barriers to entry. He says that traders who were exporting slaves from the Upper South were price-taking, profit-maximizers acting in a market that achieved a long-run competitive equilibrium.

Using an admittedly limited set of data from Dunning School

The Dunning School was a historiographical school of thought regarding the Reconstruction period of American history (1865–1877), supporting conservative elements against the Radical Republicans who introduced civil rights in the South. It was n ...

historian Ulrich Phillips (includes market data from Richmond, Charleston, mid-Georgia, and Louisiana), Robert Evans Jr. estimates that the average differential between slave prices in the Upper South and Deep South markets from 1830–1835 was $232. In 1876, Tarlton Arterburn told a newspaper reporter that they'd made an average profit of 30 to 40 percent "per head".

Evans suggests that interstate slave traders earned a wage greater than that of an alternative profession in skilled mechanical trades. However, if slave traders possessed skills similar to those used in supervisory mechanics (e.g. skills used by a chief engineer), then slave traders received an income that was not greater than the one they would have received had they entered in an alternative profession. In addition to full-time traders, so-called tavern traders worked on a small scale, especially in the first quarter of the 19th century, examples being the slave auctions held at Garland Burnett's tavern in Baltimore, Washington Robey

Washington Robey (January 1, 1841), sometimes Washington Robie, was an American tavern keeper, livery stable operator, slave trader, and slave jail proprietor in early 19th-century Washington City, District of Columbia.

Life and work

Ro ...

's slave pen and tavern in Washington, D.C., Turner Brashears of Brashears' Stand along the Natchez Trace

The Natchez Trace, also known as the Old Natchez Trace, is a historic forest trail within the United States which extends roughly from Nashville, Tennessee, to Natchez, Mississippi, linking the Cumberland River, Cumberland, Tennessee River, ...

, as well as the notorious Patty Cannon ring in Delaware.

Chesapeake cities like Baltimore

Baltimore is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the 30th-most populous U.S. city. The Baltimore metropolitan area is the 20th-large ...

, Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, and Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, a city in the United States

* Richmond, London, a town in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, England

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town ...

were "slave collecting and resale centers." Major slave-buying markets were located Charleston, Savannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) biome and ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach th ...

, Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Mem ...

, and above all, New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

. Economists estimate that more than 135,000 enslaved people were sold in New Orleans between 1804 and 1862. Some traders only bought and sold locally; smaller interstate trading companies would typically have both upper south and lower south locations, for buying and selling, respectively. Larger interstate firms, like Franklin & Armfield

Franklin may refer to:

People and characters

* Franklin (given name), including list of people and characters with the name

* Franklin (surname), including list of people and characters with the name

* Franklin (class), a member of a historica ...

, and Bolton, Dickens & Co., might have locations or traders under contract in a dozen cities. Dealers in the upper south worked to collect what they called "shipping lots"—enough people to be worth spending time and money arranging for their transport south. There was a trading season, namely winter and spring, because summer and autumn were planting and harvesting time; farmers and plantation owners generally would not buy or sell until that year's crop was in. The seasonality of the trade is visible in the record books of Missouri trader John R. White, which show that "Over 90 percent of the slaves imported to New Orleans were sold in the six months between November and April."

The notion that slave traders were social outcasts of low reputation, even in the South, was initially promulgated by defensive southerners and later by figures like historian Ulrich B. Phillips

Ulrich Bonnell Phillips (November 4, 1877 – January 21, 1934) was an American historian who largely defined the field of the social and economic studies of the History of the Southern United States, history of the Antebellum South and Slavery ...

. Historian Frederic Bancroft

Frederic Bancroft (October 30, 1860, in Galesburg, Illinois – February 22, 1945) was an American historian, author, and librarian. The Bancroft Prize, one of the most distinguished academic awards in the field of history, was established at Co ...

, author of ''Slave-Trading in the Old South

''Slave-Trading in the Old South'' by Frederic Bancroft, an independently wealthy freelance historian, is a classic history of domestic slave trade in the antebellum United States. Among other things, Bancroft discredited the assertions, then c ...

'' (1931) found—to the contrary of Phillips' position—that many traders were esteemed members of their communities. Members of the "best families," and a number of leading lights of the early Republic, including Chief Justice John Marshall

John Marshall (September 24, 1755July 6, 1835) was an American statesman, jurist, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth chief justice of the United States from 1801 until his death in 1835. He remai ...

and seventh President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

, were engaged in slave speculation. Contemporary researcher Steven Deyle argues that the "trader's position in society was not unproblematic and owners who dealt with the trader felt the need to satisfy themselves that they acted honorably," while Michael Tadman contends that "'trader as outcast' operated at the level of propaganda" whereas white slave owners almost universally professed a belief that slaves were not human like them, and thus dismissed the consequences of slave trading as beneath consideration. Similarly, historian Charles Dew read hundreds of letters to slave traders and found virtually zero narrative evidence for guilt, shame, or contrition about the slave trade: "If you begin with the absolute belief in white supremacy—unquestioned white superiority/unquestioned black inferiority—everything falls neatly into place: the African is inferior racial 'stock,' living in sin and ignorance and barbarism and heathenism on the 'Dark Continent' until enslaved...Slavery thus miraculously becomes a form of 'uplift' for this supposedly benighted and brutish race of people. And once notions of white supremacy and black inferiority are in place in the American South, they are passed on from one generation to the next with all the certainty and inevitability of a genetic trait." And yet despite the dehumanizing doctrines of white supremacy that seemingly mandated separatism and black oppression, there is evidence that at least some slave traders were perfectly capable of recognizing enslaved people as human, rather than some form of livestock: a not-insignificant number of white slave traders provided for the families of mixed-raced children they'd formed with women they'd once enslaved. An enslaved woman named Charity Bowery told Lydia Child that she was sold to a trader sometime before 1848 but "Bowery had often served the man oysters from a food stand she operated, even when he was unable to pay. The slave trader remembered her kindness, and after he bought Bowery and several of her children, he set her and one of the children free as recompense." Multiple sources attest that Baltimore slave trader James F. Purvis quit the human-trafficking business and devoted himself to banking and charity projects after a religious conversion, and New Orleans trader Elihu Creswell emancipated his 51 slaves upon his death and even funded their transportation to free states. As historian Deyle put it in ''Carry Me Back'' (2005): "While there is no record of any slave traders feeling guilt over what they did for a living, the actions taken by the New Orleans dealer Elihu Creswell do raise some questions." Abolitionist Lewis Hayden

Lewis Hayden (December 2, 1811 – April 7, 1889) escaped slavery in Kentucky with his family and reached Canada. He established a school for African Americans before moving to Boston, Massachusetts. There he became an Abolitionism in the United ...

wrote to Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher Stowe (; June 14, 1811 – July 1, 1896) was an American author and Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist. She came from the religious Beecher family and wrote the popular novel ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (185 ...

, "I knew a great many of them, such as Neal, McAnn nowiki/>Neal McCann?">Neal_McCann.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Neal McCann">nowiki/>Neal McCann? David Cobb (slave trader)">Cobb

Cobb may refer to:

People

* Cobb (surname), a list of people and fictional characters with the surname Cobb

* Cobb Rooney (1900–1973), American professional football running back

Places New Zealand

* Cobb River

* Cobb Reservoir

* Cobb Power ...Stone

In geology, rock (or stone) is any naturally occurring solid mass or aggregate of minerals or mineraloid matter. It is categorized by the minerals included, its Chemical compound, chemical composition, and the way in which it is formed. Rocks ...

, Pulliam Pulliam ( , ) is a surname of English and Welsh origin. Notable people with the surname include:

* Dolph Pulliam (born 1946), American basketball player and sportscaster

* Eugene C. Pulliam (1889–1975), American newspaper publisher and businessm ...

, and Hector Davis">Davis

Davis may refer to:

Places Antarctica

* Mount Davis (Antarctica)

* Davis Island (Palmer Archipelago)

* Davis Station, an Australian base and research outpost in the Vestfold Hills

* Davis Valley, Queen Elizabeth Land

Canada

* Davis, Sa ... Stowe commented on slave traders in ''A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (1853), in reference to her fictional character Mr. Haley:

Stowe commented on slave traders in ''A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (1853), in reference to her fictional character Mr. Haley:

Product and price

Male slaves were worth more than female slaves; one study found that on average males sold for nine percent more than females. But female slaves came with "increase"—children born enslaved to an enslaved woman were saleable, thus providing excellent return on investment. Prime age slaves were those ages 10 to 35, or more broadly enslaved children older than eight and enslaved adults younger than 40, because people of those ages were presumed to be able work and/or reproduce for an extended period of time. Overall, buyers competed most for male field hands aged 18 to 30, so "the selling price of this class supplied something of a basis for the sale of all Negroes". As a rule, there was an inverse correlation between age and price for enslaved people over 40. For example, in 1835 South Carolina, when Ann Ball spent almost to buy 215 enslaved people from the estates of her deceased relatives, she made a point to buy several apparently elderly slaves (Old Rachel, Old Lucy, Old Charles) and the lowest-priced single person was Old Peg, purchased for , compared to an average price of $371 per. Another illustration of comparative slave prices is from the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation program: "The highest priced slave was a blacksmith worth $1800, and the lowest riced wasa two-months-old mulatto baby, worth $25." On the other end of the price spectrum from old women and babies is the amount men would pay for sexual access to physically attractive young female slaves, the so-called " fancy girls," such as was the case is this post-war boast by former slave trader Jack Campbell: "Long as you ask about it, I remember the biggest money I ever got for a nigger was $9,000 for a devilish prettyquadroon

In the colonial societies of the Americas and Australia, a quadroon or quarteron (in the United Kingdom, the term quarter-caste is used) was a person with one-quarter African/ Aboriginal and three-quarters European ancestry. Similar classifica ...

wench that I sold in Louisville, about '52 or '53. She was only 18, and was about as white as you or me, and her two children had light, curly hair. Her master lived down near Bowling Green

A bowling green is a finely laid, close-mown and rolled stretch of turf for playing the game of bowls.

Before 1830, when Edwin Beard Budding of Thrupp, near Stroud, UK, invented the lawnmower, lawns were often kept cropped by grazing sheep ...

, and though he didn't want to part with her he was so down on his luck that he had to sell her. I heard, too, that his wife swore that nigger must leave the plantation or she would go home to her family. My instructions were not to take less than $6,000 for the girl, and I was to get a big percentage on all over that, so when they put her on the block I talked her up for all she was worth...There was more than twenty men bidding for her, and the fellow that got her for $9,000 was a rich and gay young bachelor from Tennessee, who happened to be in the city on a spree and was attracted by curiosity to the sale. He was a little drinky and wasn't caring anything for his ducats

The ducat ( ) coin was used as a trade coin in Europe from the later Middle Ages to the 19th century. Its most familiar version, the gold ducat or sequin containing around of 98.6% fine gold, originated in Venice in 1284 and gained wide inter ...

. He was so set on having the girl, I believe he would have given $20,000 for her if anybody had bid her up that high. He carried her home that day, and I ain't going to tell you anything more about him than that he made a big name in the Southern army and was killed at the head of his soldiers. One of this woman's children by her first master lives in a Massachusetts town now and is a rich man. There isn't a sign of black blood in him." The amount $9,000 in 1853 would be over $250,000 today. Another example of the value of enslaved girls most likely sold for sex compared to slaves sold for field labor is found in the papers of slave trader Joseph Erwin. Slave prices were high in the year 1818, and records show Erwin sold $19,000 worth of people that year. The highest prices were paid for three prime-age male field hands, Hooper, Sam, and Peter, priced at $1,250, $1,200, and $1,500, and for "a quadroon

In the colonial societies of the Americas and Australia, a quadroon or quarteron (in the United Kingdom, the term quarter-caste is used) was a person with one-quarter African/ Aboriginal and three-quarters European ancestry. Similar classifica ...

, Chloe, aged 12 and warranted a slave for life...sold to Dominie DeVerbois for the price of $1,800."

There were several broad categories of work for which enslaved people were purchased: agriculture, domestic service, mechanical, and commercial-industrial. Agricultural workers grew and processed cash crops like cotton and sugar, or managed herds of cattle in Texas, etc. Domestics worked in the household or in hotels and taverns, cooking, cleaning, laundering clothes, producing household goods, and providing childcare, including supplying the free white babies they cared for with their own human milk. Mechanics were expensive and prized: these were the smiths, builders, craftsmen, etc. Finally, commercial-industrial slaves were put to work all over the south in ironworks, salt mines, steamboat boiler rooms, on railroads, at gin-houses, bagasse

Bagasse ( ) is the dry pulpy fibrous material that remains after crushing sugarcane or sorghum stalks to extract their juice. It is used as a biofuel for the production of heat, energy, and electricity, and in the manufacture of pulp and building ...

-burners, lumber mills, turpentine stills, and so forth. The owner of a slave might or might not be a slave's ''employer'': owners often rented, leased, or "hired out" their slaves.

According to historian Bancroft, in the great slave market that was New Orleans, enslaved people imported from Virginia, and to a lesser extent Maryland and South Carolina, were advertised as an especially desirable product, whereas "the many slaves brought from Missouri and Kentucky" were rarely advertised by their place of origin. "Acclimated" slaves known to be immune to yellow fever and other communicable diseases also commanded a premium.

In 1858 the ''Wiregrass Reporter'' of Georgia advised estimating "the value of enslaved Black people by a formula of '$100 for every cent per pound of cotton.' The example given suggests that if cotton is 10 cents per pound, you should pay $1000 for an enslaved person." In 1860, the editors of the Vicksburg, Mississippi city director reported that the wealth of city included 1,236 slaves collectively valued at $876,300. According to economist Laurence Kotlikoff

Laurence Jacob Kotlikoff (born January 30, 1951) is an American economist who has served as a professor of economics at Boston University since 1984.https://kotlikoff.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Vita-2-21-24-Laurence-Kotlikoff.pdf A specialis ...

, as the American Civil War was beginning in 1861, the typical price of a prime-age male slave sold in New Orleans was . On average the prices for light-skinned female slaves were 5.4 percent higher than the prices for darker-skinned female slaves, possibly indicating colorism

Discrimination based on skin tone, also known as colorism or shadeism, is a form of prejudice and discrimination in which individuals of the same race receive benefits or disadvantages based on the color of their skin. More specifcally, coloris ...

and sexual attraction as a factor in a market dominated by male buyers. Per Kotlikoff's calculations, "Throughout the ante-bellum 1800s, positive premia were paid for males, skilled slaves, slaves with guarantees, and children sold with their mothers."

Routes

There were four main methods of forced transportation of the enslaved. Initially, transport was either on foot or by sailing ship, but following the popularization of therailroad

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport using wheeled vehicles running in railway track, tracks, which usually consist of two parallel steel railway track, rails. Rail transport is one of the two primary means of ...

and the steamboat

A steamboat is a boat that is marine propulsion, propelled primarily by marine steam engine, steam power, typically driving propellers or Paddle steamer, paddlewheels. The term ''steamboat'' is used to refer to small steam-powered vessels worki ...

in the 1840s, both were commonly used.

* Overland transport: In many cases slaves were relocated simply by walking them in chains, double-file, in groups of 50 to 200, between counties or states. Chained columns of slaves could be expected to travel about a day.

* Ocean-going ship: The coastwise slave trade

The coastwise slave trade existed along the southern and eastern coastal areas of the United States in the antebellum years prior to 1861. Hundreds of vessels of various capacities domestically traded loads of slaves along waterways, generally ...

, in which enslaved people were transported on commercial sailing ships and steamships between the East Coast and the Gulf Coast

The Gulf Coast of the United States, also known as the Gulf South or the South Coast, is the coastline along the Southern United States where they meet the Gulf of Mexico. The coastal states that have a shoreline on the Gulf of Mexico are Tex ...

via the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

and the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

, was busiest between the Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula, including parts of the Ea ...

region and the cities of the Mississippi Delta

The Mississippi Delta, also known as the Yazoo–Mississippi Delta, or simply the Delta, is the distinctive northwest section of the U.S. state of Mississippi (and portions of Arkansas and Louisiana) that lies between the Mississippi and Yazo ...

, but virtually any ship that departed south of the Mason-Dixon Line to points further south would have likely carried slaves for sale. A typical trip from the port at Norfolk

Norfolk ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in England, located in East Anglia and officially part of the East of England region. It borders Lincolnshire and The Wash to the north-west, the North Sea to the north and eas ...

to New Orleans might be a three-week journey. A statistical analysis of all known records of Baltimore–New Orleans slave shipments from 1820 to 1860 found that brigs

A brig is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: two masts which are both square-rigged. Brigs originated in the second half of the 18th century and were a common type of smaller merchant vessel or warship from then until the latter part o ...

were the type of ship used in about half of all shipments, and voyages commonly lasted between 21 and 35 days.

* Transportation via navigable inland rivers: Before 1820, keelboats, flatboats, and barges were used for riverine transport of slaves. River steamboat

A steamboat is a boat that is propelled primarily by steam power, typically driving propellers or paddlewheels. The term ''steamboat'' is used to refer to small steam-powered vessels working on lakes, rivers, and in short-sea shipping. The de ...

, by the 1850s, reduced the journey between St. Louis

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a populatio ...

to New Orleans to just a few days. Slaves were transported on virtually every tributary of the Mississippi River watershed where slavery was legal, from as far up the Ohio River

The Ohio River () is a river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing in a southwesterly direction from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to its river mouth, mouth on the Mississippi Riv ...

as Wheeling, West Virginia

Wheeling is a city in Ohio County, West Virginia, Ohio and Marshall County, West Virginia, Marshall counties in the U.S. state of West Virginia. The county seat of Ohio County, it lies along the Ohio River in the foothills of the Appalachian Mo ...

, and Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville is the List of cities in Kentucky, most populous city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky, sixth-most populous city in the Southeastern United States, Southeast, and the list of United States cities by population, 27th-most-populous city ...

, down the Cumberland River

The Cumberland River is a major waterway of the Southern United States. The U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 8, 2011 river drains almost of southern Kentucky and ...

from Nashville

Nashville, often known as Music City, is the capital and List of municipalities in Tennessee, most populous city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the county seat, seat of Davidson County, Tennessee, Davidson County in Middle Tennessee, locat ...

, and up the Red River of the South

The Red River is a major river in the Southern United States. It was named for its reddish water color from passing through red-bed country in its watershed. It also is known as the Red River of the South to distinguish it from the Red River ...

through Louisiana and Arkansas. Any navigable inland waterway or ship that was used to transport goods that were produced with slave labor was also used to transport slaves to buyers: the Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States and is the longest free-flowing (undammed) river in the Eastern United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock, New York, the river flows for a ...

was used to take slaves to market in colonial Pennsylvania; the Chattahoochee River

The Chattahoochee River () is a river in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern United States. It forms the southern half of the Alabama and Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia border, as well as a portion of the Florida and Georgia border. It ...

was access to the slave markets at Columbus, Georgia

Columbus is a consolidated city-county located on the west-central border of the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. Columbus lies on the Chattahoochee River directly across from Phenix City, Alabama. It is the county seat of Muscogee ...

, etc.

* Rail transport: As early as 1841, Southern railroad companies bought male slaves to build railroads, with at least 85 of 113 railroads in the former Confederacy having used enslaved labor for construction within and between states.

Specific routes

* Montgomery became the leading slave market in Alabama because of its accessibility by both water and land, due to its connection to both the Federal Road and the

* Montgomery became the leading slave market in Alabama because of its accessibility by both water and land, due to its connection to both the Federal Road and the Alabama River

The Alabama River, in the U.S. state of Alabama, is formed by the Tallapoosa River, Tallapoosa and Coosa River, Coosa rivers, which unite about north of Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery, near the town of Wetumpka, Alabama, Wetumpka.

Over a co ...

, the latter of which saw steamboats shipping slaves up the river from Mobile.

* The Wilderness Road

The Wilderness Road was one of two principal routes used by colonial and early national era settlers to reach Kentucky from the East. Although this road goes through the Cumberland Gap into southern Kentucky and northern Tennessee, the other ...

connected Virginia to Kentucky and east Tennessee, and from there through the Cumberland Gap to Georgia and Alabama.

* The Natchez Trace

The Natchez Trace, also known as the Old Natchez Trace, is a historic forest trail within the United States which extends roughly from Nashville, Tennessee, to Natchez, Mississippi, linking the Cumberland River, Cumberland, Tennessee River, ...

was used to bring slaves from middle Tennessee and to the Forks of the Road and Vicksburg slave markets in Mississippi. ''The Devil's Backbone'', a history of the Trace, states that one "traveler on the road described such 'a long procession' of slaves going down the Trace 'like a troop of wearied pilgrims.' The slow pace, the fatigued air, and their tattered garments 'gave to the whole train a'sad and funereal appearance.'"

* Slave trader Byrd Hill was one of the promoters of the Memphis and Hernando Plank Road.

* The South Carolina Rail Road allowed Charleston traders to sell slaves to Georgians "for personal use" at the Hamburg slave market on the Savannah River

The Savannah River is a major river in the Southeastern United States, forming most of the border between the states of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and South Carolina. The river flows from the Appalachian Mountains to the Atlantic Ocean, ...

.

* Kentucky slave traders, for their part, used the Mobile and Ohio Railroad

Mobile may refer to:

Places

* Mobile, Alabama, a U.S. port city

* Mobile County, Alabama

* Mobile, Arizona, a small town near Phoenix, U.S.

* Mobile, Newfoundland and Labrador

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Mobile ...

, the Louisville and Nashville Railroad

The Louisville and Nashville Railroad , commonly called the L&N, was a Class I railroad that operated freight and passenger services in the southeast United States.

Chartered by the Commonwealth of Kentucky in 1850, the road grew into one of ...

, and the southern branches of the present Illinois Central

The Illinois Central Railroad , sometimes called the Main Line of Mid-America, is a railroad in the Central United States. Its primary routes connected Chicago, Illinois, with New Orleans, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama, and thus, the Great Lak ...

railroads to deliver enslaved people to the Deep South.

* The Forrest brothers no doubt used the Mississippi and Tennessee Railroad

The Mississippi and Tennessee Railroad was an American railroad constructed in the 1850s, connecting Memphis, Tennessee with Grenada, Mississippi. In Grenada, the line connected with the Mississippi Central Railroad.

History

The railroad was ...

to deliver enslaved people from Memphis to the wye at Grenada, Mississippi

Grenada () is a city in Grenada County, Mississippi, Grenada County, Mississippi, United States. Founded in 1836, the population was 13,092 at the United States Census, 2010, 2010 census. It is the county seat of Grenada County, Mississippi, Gre ...

, where some of Forrests were known to have traded and lived.

Combining modes was also common, for example, as reported in the ''Anti-Slavery Bugle'' in 1849:

Law

In the early 19th century several slave states had unenforced statutes prohibiting the interstate slave trade in hopes of minimizing the increase of black populations within those states. These laws were undermined in many ways; for example, "

In the early 19th century several slave states had unenforced statutes prohibiting the interstate slave trade in hopes of minimizing the increase of black populations within those states. These laws were undermined in many ways; for example, "Hamburg, South Carolina

Hamburg is a ghost town in Aiken County, South Carolina, United States. It was once a thriving upriver market located across the Savannah River from Augusta, Georgia in the Edgefield District. It was founded by Henry Shultz in 1821 who named ...

was built up just opposite Augusta, for the purpose of furnishing slaves to the planters of Georgia. Augusta is the market to which the planters of Upper and Middle Georgia bring their cotton; and if they want to purchase negroes, they step over into Hamburg and do so. There are two large houses there, with piazzas in front to expose the 'chattels' to the public during the day, and yards in rear of them where they are penned up at night like sheep, so close that they can hardly breathe, with bull-dogs on the outside as sentinels. They sometimes have thousands here for sale, who in consequence of their number suffer most horribly." Similarly, in Alabama, a historian explained in 1845 that a ban had been undermined to the point that it was ultimately abandoned entirely: "...The people of Alabama at one time became alarmed at the evils which they properly anticipated would grow out of this traffic. Their Legislators enacted laws against it, and for a short time they exercised salutary restraints; but soon they were evaded. The Creek Nation

The Muscogee Nation, or Muscogee (Creek) Nation, is a List of federally recognized tribes, federally recognized Native American tribe based in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The nation descends from the historic Muscogee Confederacy, a large grou ...

was then an Indian Territory, under the jurisdiction of the General Government, lying immediately on our eastern border. Here Negro Traders sought a shield for their operations, and our citizens went there to make purchases. Worn out at last with such subterfuges and shifts, the Legislature repealed this restrictive law..." When Louisiana banned slave traders from out of state in 1832, Austin Woolfolk

Austin Woolfolk (17961847) was an American slave trader and plantation owner. Among the busiest slave traders in Maryland, he trafficked more than 2,000 enslaved people through the Port of Baltimore to the Port of New Orleans, and became notorious ...

set up operations at Fort Adams, Mississippi

Fort Adams is a small, river port community in Wilkinson County, Mississippi, Wilkinson County, Mississippi, United States, about south of Natchez, Mississippi, Natchez. It is notable for having been the U.S. port of entry on the Mississippi ...

, which was the first steamboat landing beyond the state line. Similarly, the organizing act for Mississippi Territory prohibited the introduction of slaves from outside the U.S. but "the foreign trade ban seems to have been ignored."

Music

The slave trade appears in the lyrics of working songs sung by African-American slaves in the antebellum U.S.:See also

*Slave Trade Act of 1794

The Slave Trade Act of 1794 was a law passed by the United States Congress that prohibited the building or outfitting of ships in U.S. ports for the international slave trade. It was signed into law by President George Washington on March 22, 1 ...

* Slave Trade Act of 1800

The Slave Trade Act of 1800 was a law passed by the United States Congress to build upon the Slave Trade Act of 1794, limiting American involvement in the trade of human cargo. It was signed into law by President John Adams on May 10, 1800. Thi ...

* Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves

The Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves of 1807 (, enacted March 2, 1807) is a United States federal law that prohibited the importation of slaves into the United States. It took effect on January 1, 1808, the earliest date permitted by the U ...

*

* Treatment of the enslaved in the United States

Treatment may refer to:

* Treatment (song), "Treatment" (song), a 2012 song by

* Film treatment, a prose telling of a story intended to be turned into a screenplay

* Medical treatment also known as "therapy"

* Sewage treatment

* Surface treatment ...

* Torture of slaves in the United States

Torture of slaves in the United States was fairly common, as part of what many slavers claimed was necessary discipline. As one history put it, "Stinted allowance, imprisonment, and whipping were the usual methods of punishment; incorrigibles we ...

* List of largest slave sales in the United States

* Bibliography of the slave trade in the United States

References

Sources

* *Further reading

* * *External links

Texas Domestic Slave Trade Project at University of Texas

{{History of slavery in the United States * Slavery in the United States Antebellum South 19th century in the United States History of the Southern United States Economic history of the United States Economic history of slavery in the United States