infantile paralysis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Poliomyelitis ( ), commonly shortened to polio, is an

Poliomyelitis does not affect any species other than humans. The disease is caused by infection with a member of the

Poliomyelitis does not affect any species other than humans. The disease is caused by infection with a member of the

Poliovirus enters the body through the mouth, infecting the first cells with which it comes in contact – the

Poliovirus enters the body through the mouth, infecting the first cells with which it comes in contact – the

In around one percent of infections, poliovirus spreads along certain nerve fiber pathways, preferentially replicating in and destroying

In around one percent of infections, poliovirus spreads along certain nerve fiber pathways, preferentially replicating in and destroying

Spinal polio, the most common form of paralytic poliomyelitis, results from viral invasion of the motor neurons of the anterior horn cells, or the

Spinal polio, the most common form of paralytic poliomyelitis, results from viral invasion of the motor neurons of the anterior horn cells, or the

Making up about two percent of cases of paralytic polio, bulbar polio occurs when poliovirus invades and destroys nerves within the

Making up about two percent of cases of paralytic polio, bulbar polio occurs when poliovirus invades and destroys nerves within the

Two types of vaccine are used throughout the world to combat polio: an inactivated poliovirus given by injection, and a weakened poliovirus given by mouth. Both types induce immunity to polio and are effective in protecting individuals from disease.

The inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) was developed in 1952 by

Two types of vaccine are used throughout the world to combat polio: an inactivated poliovirus given by injection, and a weakened poliovirus given by mouth. Both types induce immunity to polio and are effective in protecting individuals from disease.

The inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) was developed in 1952 by  Because the oral polio vaccine is inexpensive, easy to administer, and produces excellent immunity in the intestine (which helps prevent infection with wild virus in areas where it is

Because the oral polio vaccine is inexpensive, easy to administer, and produces excellent immunity in the intestine (which helps prevent infection with wild virus in areas where it is

Patients with abortive polio infections recover completely. In those who develop only aseptic meningitis, the symptoms can be expected to persist for two to ten days, followed by complete recovery. In cases of spinal polio, if the affected nerve cells are completely destroyed, paralysis will be permanent; cells that are not destroyed, but lose function temporarily, may recover within four to six weeks after onset. Reproduced online with permission by Post-Polio Health International; retrieved on 10 November 2007. Half the patients with spinal polio recover fully; one-quarter recover with mild disability, and the remaining quarter are left with severe disability. The degree of both acute paralysis and residual paralysis is likely to be proportional to the degree of viremia, and

Patients with abortive polio infections recover completely. In those who develop only aseptic meningitis, the symptoms can be expected to persist for two to ten days, followed by complete recovery. In cases of spinal polio, if the affected nerve cells are completely destroyed, paralysis will be permanent; cells that are not destroyed, but lose function temporarily, may recover within four to six weeks after onset. Reproduced online with permission by Post-Polio Health International; retrieved on 10 November 2007. Half the patients with spinal polio recover fully; one-quarter recover with mild disability, and the remaining quarter are left with severe disability. The degree of both acute paralysis and residual paralysis is likely to be proportional to the degree of viremia, and

Paralysis, length differences and deformations of the lower extremities can lead to a hindrance when walking with compensation mechanisms that lead to a severe impairment of the gait pattern. In order to be able to stand and walk safely and to improve the gait pattern,

Paralysis, length differences and deformations of the lower extremities can lead to a hindrance when walking with compensation mechanisms that lead to a severe impairment of the gait pattern. In order to be able to stand and walk safely and to improve the gait pattern,

The effects of polio have been known since

The effects of polio have been known since

online

* * Hecht, Alan, and I. Edward Alcamo. ''Polio'' (2003

online copy

for middle schools * * , a major scholarly history. * Rai, Anushree, et al. "Polio returns to the USA: An epidemiological alert." ''Annals of Medicine and Surgery'' 82 (2022)

online

* * * * * Zimmermann, Jonas. "War on Disease: Polio Eradication in the United States." ''Historia. scriber'' 15 (2023): 263-280

online

infectious disease

An infection is the invasion of tissue (biology), tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host (biology), host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmis ...

caused by the poliovirus

Poliovirus, the causative agent of polio (also known as poliomyelitis), is a serotype of the species '' Enterovirus C'', in the family of '' Picornaviridae''. There are three poliovirus serotypes, numbered 1, 2, and 3.

Poliovirus is composed ...

. Approximately 75% of cases are asymptomatic

Asymptomatic (or clinically silent) is an adjective categorising the medical conditions (i.e., injuries or diseases) that patients carry but without experiencing their symptoms, despite an explicit diagnosis (e.g., a positive medical test).

P ...

; mild symptoms which can occur include sore throat and fever; in a proportion of cases more severe symptoms develop such as headache

A headache, also known as cephalalgia, is the symptom of pain in the face, head, or neck. It can occur as a migraine, tension-type headache, or cluster headache. There is an increased risk of Depression (mood), depression in those with severe ...

, neck stiffness, and paresthesia

Paresthesia is a sensation of the skin that may feel like numbness (''hypoesthesia''), tingling, pricking, chilling, or burning. It can be temporary or Chronic condition, chronic and has many possible underlying causes. Paresthesia is usually p ...

. These symptoms usually pass within one or two weeks. A less common symptom is permanent paralysis

Paralysis (: paralyses; also known as plegia) is a loss of Motor skill, motor function in one or more Skeletal muscle, muscles. Paralysis can also be accompanied by a loss of feeling (sensory loss) in the affected area if there is sensory d ...

, and possible death in extreme cases.. Years after recovery, post-polio syndrome

Post-polio syndrome (PPS, poliomyelitis sequelae) is a group of latent symptoms of poliomyelitis (polio), occurring in more than 80% of polio infections. The symptoms are caused by the damaging effects of the viral infection on the nervous syst ...

may occur, with a slow development of muscle weakness similar to what the person had during the initial infection.

Polio occurs naturally only in humans. It is highly infectious, and is spread from person to person either through fecal–oral transmission (e.g. poor hygiene, or by ingestion of food or water contaminated by human feces), or via the oral–oral route. Those who are infected may spread the disease for up to six weeks even if no symptoms are present. The disease may be diagnosed by finding the virus in the feces

Feces (also known as faeces American and British English spelling differences#ae and oe, or fæces; : faex) are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the ...

or detecting antibodies

An antibody (Ab) or immunoglobulin (Ig) is a large, Y-shaped protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which is used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as bacteria and viruses, including those that caus ...

against it in the blood.

Poliomyelitis has existed for thousands of years, with depictions of the disease in ancient art. The disease was first recognized as a distinct condition by the English physician

A physician, medical practitioner (British English), medical doctor, or simply doctor is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through the Medical education, study, Med ...

Michael Underwood in 1789, and the virus that causes it was first identified in 1909 by the Austrian immunologist Karl Landsteiner

Karl Landsteiner (; 14 June 1868 – 26 June 1943) was an Austrian-American biologist, physician, and immunologist. He emigrated with his family to New York in 1923 at the age of 55 for professional opportunities, working for the Rockefeller ...

. Major outbreaks

In epidemiology, an outbreak is a sudden increase in occurrences of a disease when cases are in excess of normal expectancy for the location or season. It may affect a small and localized group or impact upon thousands of people across an entire ...

started to occur in the late 19th century in Europe and the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, and in the 20th century, it became one of the most worrying childhood diseases. Following the introduction of polio vaccines in the 1950s, polio incidence declined rapidly. , only Pakistan and Afghanistan remain endemic for wild poliovirus (WPV).

Once infected, there is no specific treatment. The disease can be prevented by the polio vaccine

Polio vaccines are vaccines used to prevent poliomyelitis (polio). Two types are used: an inactivated vaccine, inactivated poliovirus given by injection (IPV) and a attenuated vaccine, weakened poliovirus given by mouth (OPV). The World Healt ...

, with multiple doses required for lifelong protection. There are two broad types of polio vaccine; an injected polio vaccine (IPV) using inactivated poliovirus and an oral polio vaccine (OPV) containing attenuated (weakened) live virus. Through the use of both types of vaccine, incidence of wild polio has decreased from an estimated 350,000 cases in 1988 to 30 confirmed cases in 2022, confined to just three countries. In rare cases, the traditional OPV was able to revert to a virulent form. An improved oral vaccine with greater genetic stability (nOPV2) was developed and granted full licensure and prequalification by the World Health Organization in December 2023.

Signs and symptoms

The term "poliomyelitis" is used to identify the disease caused by any of the three serotypes of poliovirus. Two basic patterns of polio infection are described: a minor illness that does not involve thecentral nervous system

The central nervous system (CNS) is the part of the nervous system consisting primarily of the brain, spinal cord and retina. The CNS is so named because the brain integrates the received information and coordinates and influences the activity o ...

(CNS), sometimes called abortive poliomyelitis, and a major illness involving the CNS, which may be paralytic or nonparalytic. Adults are more likely to develop symptoms, including severe symptoms, than children.

In most people with a normal immune system, a poliovirus infection is asymptomatic

Asymptomatic (or clinically silent) is an adjective categorising the medical conditions (i.e., injuries or diseases) that patients carry but without experiencing their symptoms, despite an explicit diagnosis (e.g., a positive medical test).

P ...

. In about 25% of cases, the infection produces minor symptoms which may include sore throat

Sore throat, also known as throat pain, is pain or irritation of the throat. The majority of sore throats are caused by a virus, for which antibiotics are not helpful.

For sore throat caused by bacteria (GAS), treatment with antibiotics may hel ...

and low fever. These symptoms are temporary and full recovery occurs within one or two weeks.

In about 1 percent of infections the virus can migrate from the gastrointestinal tract into the central nervous system (CNS). Most patients with CNS involvement develop nonparalytic aseptic meningitis, with symptoms of headache, neck, back, abdominal and extremity pain, fever, vomiting, stomach pain, lethargy

Lethargy is a state of tiredness, sleepiness, weariness, fatigue, sluggishness, or lack of energy. It can be accompanied by depression, decreased motivation, or apathy. Lethargy can be a normal response to inadequate sleep, overexertion, overw ...

, and irritability. About one to five in 1,000 cases progress to paralytic

Paralysis (: paralyses; also known as plegia) is a loss of motor function in one or more muscles. Paralysis can also be accompanied by a loss of feeling (sensory loss) in the affected area if there is sensory damage. In the United States, ...

disease, in which the muscles become weak, floppy and poorly controlled, and, finally, completely paralyzed; this condition is known as acute flaccid paralysis

Flaccid paralysis is a neurological condition characterized by weakness or paralysis and reduced muscle tone without other obvious cause (e.g., trauma). This abnormal condition may be caused by disease or by trauma affecting the nerves associ ...

. The weakness most often involves the legs, but may less commonly involve the muscles of the head, neck, and diaphragm. Depending on the site of paralysis, paralytic poliomyelitis is classified as spinal, bulbar

The medulla oblongata or simply medulla is a long stem-like structure which makes up the lower part of the brainstem. It is anterior and partially inferior to the cerebellum. It is a cone-shaped neuronal mass responsible for autonomic (involun ...

, or bulbospinal. In those who develop paralysis, between 2 and 10 percent die as the paralysis affects the breathing muscles.

Encephalitis

Encephalitis is inflammation of the Human brain, brain. The severity can be variable with symptoms including reduction or alteration in consciousness, aphasia, headache, fever, confusion, a stiff neck, and vomiting. Complications may include se ...

, an infection of the brain tissue itself, can occur in rare cases, and is usually restricted to infants. It is characterized by confusion, changes in mental status, headaches, fever, and, less commonly, seizure

A seizure is a sudden, brief disruption of brain activity caused by abnormal, excessive, or synchronous neuronal firing. Depending on the regions of the brain involved, seizures can lead to changes in movement, sensation, behavior, awareness, o ...

s and spastic paralysis.

Etymology

The term ''poliomyelitis'' derives from theAncient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

(), meaning "grey", ( "marrow"), referring to the grey matter of the spinal cord

The spinal cord is a long, thin, tubular structure made up of nervous tissue that extends from the medulla oblongata in the lower brainstem to the lumbar region of the vertebral column (backbone) of vertebrate animals. The center of the spinal c ...

, and the suffix ''-itis

Inflammation (from ) is part of the biological response of body tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants. The five cardinal signs are heat, pain, redness, swelling, and loss of function (Latin ''calor'', '' ...

'', which denotes inflammation

Inflammation (from ) is part of the biological response of body tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants. The five cardinal signs are heat, pain, redness, swelling, and loss of function (Latin ''calor'', '' ...

, i.e., inflammation of the spinal cord's grey matter. The word was first used in 1874 and is attributed to the German physician Adolf Kussmaul. The first recorded use of the abbreviated version ''polio'' was in the '' Indianapolis Star'' in 1911.

Cause

genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

''Enterovirus

''Enterovirus'' is a genus of positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses associated with several human and mammalian diseases. Enteroviruses are named by their transmission-route through the intestine ('enteric' meaning intestinal).

Serologic ...

'' known as poliovirus

Poliovirus, the causative agent of polio (also known as poliomyelitis), is a serotype of the species '' Enterovirus C'', in the family of '' Picornaviridae''. There are three poliovirus serotypes, numbered 1, 2, and 3.

Poliovirus is composed ...

(PV). This group of RNA virus

An RNA virus is a virus characterized by a ribonucleic acid (RNA) based genome. The genome can be single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) or double-stranded (Double-stranded RNA, dsRNA). Notable human diseases caused by RNA viruses include influenza, SARS, ...

es colonize the gastrointestinal tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the Digestion, digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascula ...

– specifically the oropharynx

The pharynx (: pharynges) is the part of the throat behind the mouth and nasal cavity, and above the esophagus and trachea (the tubes going down to the stomach and the lungs respectively). It is found in vertebrates and invertebrates, though its ...

and the intestine

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascular system. T ...

. Its structure

A structure is an arrangement and organization of interrelated elements in a material object or system, or the object or system so organized. Material structures include man-made objects such as buildings and machines and natural objects such as ...

is quite simple, composed of a single (+) sense RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyrib ...

genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

enclosed in a protein shell called a capsid

A capsid is the protein shell of a virus, enclosing its genetic material. It consists of several oligomeric (repeating) structural subunits made of protein called protomers. The observable 3-dimensional morphological subunits, which may or m ...

. In addition to protecting the virus' genetic material, the capsid proteins enable poliovirus to infect certain types of cells. Three serotypes of poliovirus have been identified – wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1), type 2 (WPV2), and type 3 (WPV3) – each with a slightly different capsid protein. All three are extremely virulent and produce the same disease symptoms. WPV1 is the most commonly encountered form, and the one most closely associated with paralysis. (Available free on Medscape

Medscape is a website providing access to medical information for clinicians and medical scientists; the organization also provides continuing education for physicians and other health professionals. It references medical journal articles, Con ...

; registration required.) WPV2 was certified as eradicated in 2015 and WPV3 certified as eradicated in 2019.

The incubation period

Incubation period (also known as the latent period or latency period) is the time elapsed between exposure to a pathogenic organism, a chemical, or ionizing radiation, radiation, and when symptoms and signs are first apparent. In a typical infect ...

(from exposure to the first signs and symptoms) ranges from three to six days for nonparalytic polio. If the disease progresses to cause paralysis, this occurs within 7 to 21 days.

Individuals who are exposed to the virus, either through infection or by immunization

Immunization, or immunisation, is the process by which an individual's immune system becomes fortified against an infectious agent (known as the antigen, immunogen). When this system is exposed to molecules that are foreign to the body, called ' ...

via polio vaccine

Polio vaccines are vaccines used to prevent poliomyelitis (polio). Two types are used: an inactivated vaccine, inactivated poliovirus given by injection (IPV) and a attenuated vaccine, weakened poliovirus given by mouth (OPV). The World Healt ...

, develop immunity

Immunity may refer to:

Medicine

* Immunity (medical), resistance of an organism to infection or disease

* ''Immunity'' (journal), a scientific journal published by Cell Press

Biology

* Immune system

Engineering

* Radiofrequence immunity ...

. In immune individuals, IgA antibodies

An antibody (Ab) or immunoglobulin (Ig) is a large, Y-shaped protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which is used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as bacteria and viruses, including those that caus ...

against poliovirus are present in the tonsil

The tonsils ( ) are a set of lymphoid organs facing into the aerodigestive tract, which is known as Waldeyer's tonsillar ring and consists of the adenoid tonsil (or pharyngeal tonsil), two tubal tonsils, two palatine tonsils, and the lingual t ...

s and gastrointestinal tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the Digestion, digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascula ...

and able to block virus replication; IgG and IgM antibodies against PV can prevent the spread of the virus to motor neurons of the central nervous system

The central nervous system (CNS) is the part of the nervous system consisting primarily of the brain, spinal cord and retina. The CNS is so named because the brain integrates the received information and coordinates and influences the activity o ...

. Infection or vaccination with one serotype of poliovirus does not provide immunity against the other serotypes, and full immunity requires exposure to each serotype.

A rare condition with a similar presentation, nonpoliovirus poliomyelitis, may result from infections with enterovirus

''Enterovirus'' is a genus of positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses associated with several human and mammalian diseases. Enteroviruses are named by their transmission-route through the intestine ('enteric' meaning intestinal).

Serologic ...

es other than poliovirus.

The oral polio vaccine, which has been in use since 1961, contains weakened viruses that can replicate. On rare occasions, these may be transmitted from the vaccinated person to other people; in communities with good vaccine coverage, transmission is limited, and the virus dies out. In communities with low vaccine coverage, this weakened virus may continue to circulate and, over time may mutate and revert to a virulent form. Polio arising from this cause is referred to as ''circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus'' (cVDPV) or ''variant poliovirus'' in order to distinguish it from the natural or "wild" poliovirus (WPV).

Transmission

Poliomyelitis is highly contagious. The disease is transmitted primarily via thefecal–oral route

The fecal–oral route (also called the oral–fecal route or orofecal route) describes a particular route of transmission of a disease wherein pathogens in fecal particles pass from one person to the mouth of another person. Main causes of fec ...

, by ingesting contaminated food or water. It is occasionally transmitted via the oral–oral route. It is seasonal in temperate climate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (approximately 23.5° to 66.5° N/S of the Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ra ...

s, with peak transmission occurring in summer and autumn. These seasonal differences are far less pronounced in tropical

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the equator, where the sun may shine directly overhead. This contrasts with the temperate or polar regions of Earth, where the Sun can never be directly overhead. This is because of Earth's ax ...

areas. Polio is most infectious between 7 and 10 days before and after the appearance of symptoms, but transmission is possible as long as the virus remains in the saliva or feces. Virus particles can be excreted in the feces

Feces (also known as faeces American and British English spelling differences#ae and oe, or fæces; : faex) are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the ...

for up to six weeks.

Factors that increase the risk of polio infection include pregnancy

Pregnancy is the time during which one or more offspring gestation, gestates inside a woman's uterus. A multiple birth, multiple pregnancy involves more than one offspring, such as with twins.

Conception (biology), Conception usually occurs ...

, being very old or very young, immune deficiency

Immunodeficiency, also known as immunocompromise, is a state in which the immune system's ability to fight infectious diseases and cancer is compromised or entirely absent. Most cases are acquired ("secondary") due to extrinsic factors that affec ...

, and malnutrition

Malnutrition occurs when an organism gets too few or too many nutrients, resulting in health problems. Specifically, it is a deficiency, excess, or imbalance of energy, protein and other nutrients which adversely affects the body's tissues a ...

. Although the virus can cross the maternal-fetal barrier during pregnancy, the fetus does not appear to be affected by either maternal infection or polio vaccination. Maternal antibodies also cross the placenta

The placenta (: placentas or placentae) is a temporary embryonic and later fetal organ that begins developing from the blastocyst shortly after implantation. It plays critical roles in facilitating nutrient, gas, and waste exchange between ...

, providing passive immunity

In immunology, passive immunity is the transfer of active humoral immunity of ready-made antibodies. Passive immunity can occur naturally, when maternal antibodies are transferred to the fetus through the placenta, and it can also be induced arti ...

that protects the infant from polio infection during the first few months of life.

Pathophysiology

Poliovirus enters the body through the mouth, infecting the first cells with which it comes in contact – the

Poliovirus enters the body through the mouth, infecting the first cells with which it comes in contact – the pharynx

The pharynx (: pharynges) is the part of the throat behind the human mouth, mouth and nasal cavity, and above the esophagus and trachea (the tubes going down to the stomach and the lungs respectively). It is found in vertebrates and invertebrates ...

and intestinal mucosa

The gastrointestinal wall of the gastrointestinal tract is made up of four layers of specialised tissue. From the inner cavity of the gut (the lumen) outwards, these are the mucosa, the submucosa, the muscular layer and the serosa or adventitia.

...

. It gains entry by binding to an immunoglobulin-like receptor, known as the poliovirus receptor or CD155, on the cell membrane. The virus then hijacks the host cell's own machinery, and begins to replicate. Poliovirus divides within gastrointestinal cells for about a week, from where it spreads to the tonsils

The tonsils ( ) are a set of lymphoid organs facing into the aerodigestive tract, which is known as Waldeyer's tonsillar ring and consists of the adenoid tonsil (or pharyngeal tonsil), two tubal tonsils, two palatine tonsils, and the lingual ...

(specifically the follicular dendritic cells residing within the tonsilar germinal center

Germinal centers or germinal centres (GCs) are transiently formed structures within B cell zone (follicles) in secondary lymphoid organs – lymph nodes, ileal Peyer's patches, and the spleen – where mature B cells are activated, prolifera ...

s), the intestinal lymphoid tissue

The lymphatic system, or lymphoid system, is an organ system in vertebrates that is part of the immune system and complementary to the circulatory system. It consists of a large network of lymphatic vessels, lymph nodes, lymphoid organs, lympha ...

including the M cells of Peyer's patches

Peyer's patches or aggregated lymphoid nodules are organized lymphoid follicles, named after the 17th-century Swiss anatomist Johann Conrad Peyer.

* Reprinted as:

* Peyer referred to Peyer's patches as ''plexus'' or ''agmina glandularum'' (cl ...

, and the deep cervical and mesenteric lymph nodes, where it multiplies abundantly. The virus is subsequently absorbed into the bloodstream.

Known as viremia, the presence of a virus in the bloodstream enables it to be widely distributed throughout the body. Poliovirus can survive and multiply within the blood and lymphatics for long periods of time, sometimes as long as 17 weeks. In a small percentage of cases, it can spread and replicate in other sites, such as brown fat, the reticuloendothelial tissues, and muscle. This sustained replication causes a major viremia, and leads to the development of minor influenza-like symptoms. Rarely, this may progress and the virus may invade the central nervous system, provoking a local inflammatory response

Inflammation (from ) is part of the biological response of body tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants. The five cardinal signs are heat, pain, redness, swelling, and loss of function (Latin ''calor'', '' ...

. In most cases, this causes a self-limiting inflammation of the meninges

In anatomy, the meninges (; meninx ; ) are the three membranes that envelop the brain and spinal cord. In mammals, the meninges are the dura mater, the arachnoid mater, and the pia mater. Cerebrospinal fluid is located in the subarachnoid spac ...

, the layers of tissue surrounding the brain

The brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head (cephalization), usually near organs for ...

, which is known as nonparalytic aseptic meningitis. Penetration of the CNS provides no known benefit to the virus, and is quite possibly an incidental deviation of a normal gastrointestinal infection. The mechanisms by which poliovirus spreads to the CNS are poorly understood, but it appears to be primarily a chance event – largely independent of the age, gender, or socioeconomic

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interac ...

position of the individual.

Paralytic polio

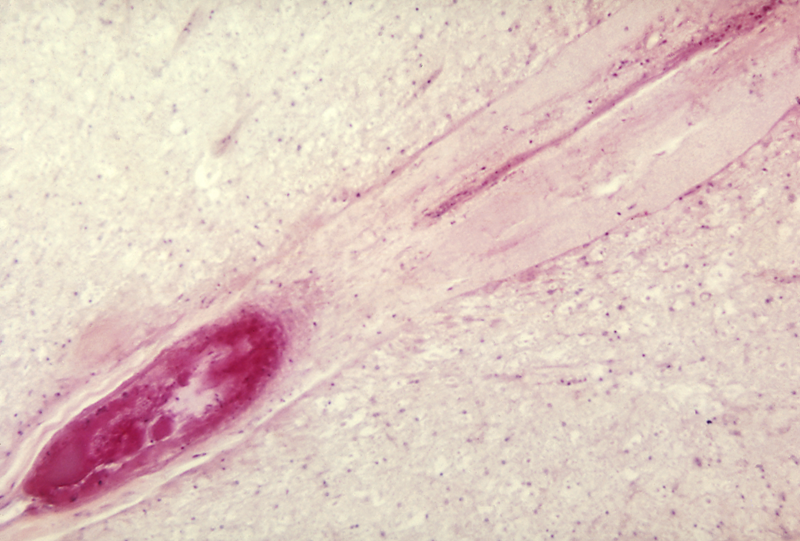

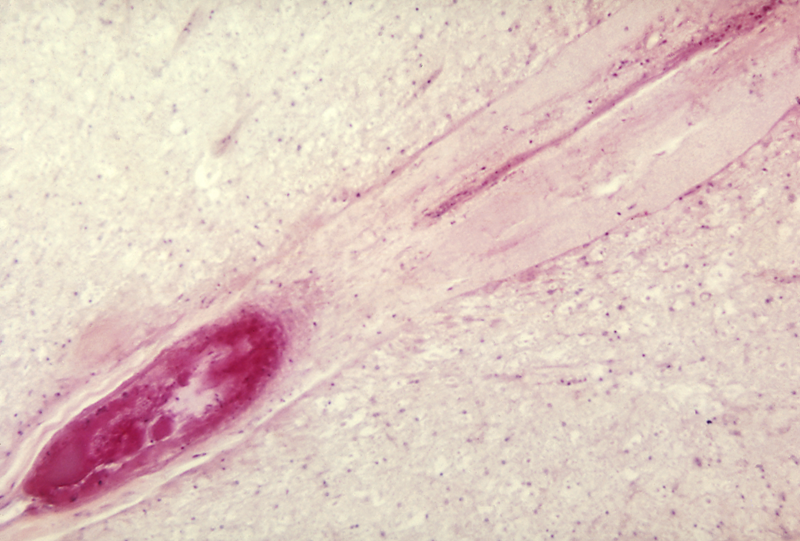

In around one percent of infections, poliovirus spreads along certain nerve fiber pathways, preferentially replicating in and destroying

In around one percent of infections, poliovirus spreads along certain nerve fiber pathways, preferentially replicating in and destroying motor neuron

A motor neuron (or motoneuron), also known as efferent neuron is a neuron whose cell body is located in the motor cortex, brainstem or the spinal cord, and whose axon (fiber) projects to the spinal cord or outside of the spinal cord to directly o ...

s within the spinal cord

The spinal cord is a long, thin, tubular structure made up of nervous tissue that extends from the medulla oblongata in the lower brainstem to the lumbar region of the vertebral column (backbone) of vertebrate animals. The center of the spinal c ...

, brain stem

The brainstem (or brain stem) is the posterior stalk-like part of the brain that connects the cerebrum with the spinal cord. In the human brain the brainstem is composed of the midbrain, the pons, and the medulla oblongata. The midbrain is co ...

, or motor cortex

The motor cortex is the region of the cerebral cortex involved in the planning, motor control, control, and execution of voluntary movements.

The motor cortex is an area of the frontal lobe located in the posterior precentral gyrus immediately ...

. This leads to the development of paralytic poliomyelitis, the various forms of which (spinal, bulbar, and bulbospinal) vary only with the amount of neuronal damage and inflammation that occurs, and the region of the CNS affected.

The destruction of neuronal cells produces lesion

A lesion is any damage or abnormal change in the tissue of an organism, usually caused by injury or diseases. The term ''Lesion'' is derived from the Latin meaning "injury". Lesions may occur in both plants and animals.

Types

There is no de ...

s within the spinal ganglia; these may also occur in the reticular formation

The reticular formation is a set of interconnected nuclei in the brainstem that spans from the lower end of the medulla oblongata to the upper end of the midbrain. The neurons of the reticular formation make up a complex set of neural networks ...

, vestibular nuclei

The vestibular nuclei (VN) are the cranial nuclei for the vestibular nerve located in the brainstem.

In Terminologia Anatomica, they are grouped in both the pons and the medulla in the brainstem

The brainstem (or brain stem) is the poste ...

, cerebellar vermis

The cerebellar vermis (from Latin ''vermis,'' "worm") is located in the medial, cortico-nuclear zone of the cerebellum, which is in the posterior cranial fossa, posterior fossa of the cranium. The primary fissure in the vermis curves ventrolatera ...

, and deep cerebellar nuclei. Inflammation associated with nerve cell

A neuron (American English), neurone (British English), or nerve cell, is an excitable cell that fires electric signals called action potentials across a neural network in the nervous system. They are located in the nervous system and help to ...

destruction often alters the color and appearance of the gray matter in the spinal column

The spinal column, also known as the vertebral column, spine or backbone, is the core part of the axial skeleton in vertebrates. The vertebral column is the defining and eponymous characteristic of the vertebrate. The spinal column is a segmen ...

, causing it to appear reddish and swollen. Other destructive changes associated with paralytic disease occur in the forebrain

In the anatomy of the brain of vertebrates, the forebrain or prosencephalon is the rostral (forward-most) portion of the brain. The forebrain controls body temperature, reproductive functions, eating, sleeping, and the display of emotions.

Ve ...

region, specifically the hypothalamus

The hypothalamus (: hypothalami; ) is a small part of the vertebrate brain that contains a number of nucleus (neuroanatomy), nuclei with a variety of functions. One of the most important functions is to link the nervous system to the endocrin ...

and thalamus

The thalamus (: thalami; from Greek language, Greek Wikt:θάλαμος, θάλαμος, "chamber") is a large mass of gray matter on the lateral wall of the third ventricle forming the wikt:dorsal, dorsal part of the diencephalon (a division of ...

.

Early symptoms of paralytic polio include high fever, headache, stiffness in the back and neck, asymmetrical weakness of various muscles, sensitivity to touch, difficulty swallowing

Dysphagia is difficulty in swallowing. Although classified under " symptoms and signs" in ICD-10, in some contexts it is classified as a condition in its own right.

It may be a sensation that suggests difficulty in the passage of solids or li ...

, muscle pain

Myalgia or muscle pain is a painful sensation evolving from muscle tissue. It is a symptom of many diseases. The most common cause of acute myalgia is the overuse of a muscle or group of muscles; another likely cause is viral infection, espec ...

, loss of superficial and deep reflex

In biology, a reflex, or reflex action, is an involuntary, unplanned sequence or action and nearly instantaneous response to a stimulus.

Reflexes are found with varying levels of complexity in organisms with a nervous system. A reflex occurs ...

es, paresthesia

Paresthesia is a sensation of the skin that may feel like numbness (''hypoesthesia''), tingling, pricking, chilling, or burning. It can be temporary or Chronic condition, chronic and has many possible underlying causes. Paresthesia is usually p ...

(pins and needles), irritability, constipation, or difficulty urinating. Paralysis generally develops one to ten days after early symptoms begin, progresses for two to three days, and is usually complete by the time the fever breaks.

The likelihood of developing paralytic polio increases with age, as does the extent of paralysis. In children, nonparalytic meningitis is the most likely consequence of CNS involvement, and paralysis occurs in only one in 1000 cases. In adults, paralysis occurs in one in 75 cases. Reproduced online with permission by Lincolnshire Post-Polio Library; retrieved on 10 November 2007. In children under five years of age, paralysis of one leg is most common; in adults, extensive paralysis of the chest

The thorax (: thoraces or thoraxes) or chest is a part of the anatomy of mammals and other tetrapod animals located between the neck and the abdomen.

In insects, crustaceans, and the extinct trilobites, the thorax is one of the three main di ...

and abdomen

The abdomen (colloquially called the gut, belly, tummy, midriff, tucky, or stomach) is the front part of the torso between the thorax (chest) and pelvis in humans and in other vertebrates. The area occupied by the abdomen is called the abdominal ...

also affecting all four limbs – quadriplegia – is more likely. Paralysis rates also vary depending on the serotype of the infecting poliovirus; the highest rates of paralysis (one in 200) are associated with poliovirus type 1, the lowest rates (one in 2,000) are associated with type 2.

Spinal polio

ventral

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to describe unambiguously the anatomy of humans and other animals. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position prov ...

(front) grey matter

Grey matter, or gray matter in American English, is a major component of the central nervous system, consisting of neuronal cell bodies, neuropil ( dendrites and unmyelinated axons), glial cells ( astrocytes and oligodendrocytes), synapses, ...

section in the spinal column

The spinal column, also known as the vertebral column, spine or backbone, is the core part of the axial skeleton in vertebrates. The vertebral column is the defining and eponymous characteristic of the vertebrate. The spinal column is a segmen ...

, which are responsible for movement of the muscles, including those of the trunk, limbs, and the intercostal muscle

The intercostal muscles comprise many different groups of muscle

Muscle is a soft tissue, one of the four basic types of animal tissue. There are three types of muscle tissue in vertebrates: skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, and smooth muscle ...

s. Virus invasion causes inflammation of the nerve cells, leading to damage or destruction of motor neuron ganglia

A ganglion (: ganglia) is a group of neuron cell bodies in the peripheral nervous system. In the somatic nervous system, this includes dorsal root ganglia and trigeminal ganglia among a few others. In the autonomic nervous system, there a ...

. When spinal neurons die, Wallerian degeneration takes place, leading to weakness of those muscles formerly innervate

A nerve is an enclosed, cable-like bundle of nerve fibers (called axons). Nerves have historically been considered the basic units of the peripheral nervous system. A nerve provides a common pathway for the electrochemical nerve impulses called ...

d by the now-dead neurons. With the destruction of nerve cells, the muscles no longer receive signals from the brain or spinal cord; without nerve stimulation, the muscles atrophy

Atrophy is the partial or complete wasting away of a part of the body. Causes of atrophy include mutations (which can destroy the gene to build up the organ), malnutrition, poor nourishment, poor circulatory system, circulation, loss of hormone, ...

, becoming weak, floppy and poorly controlled, and finally completely paralyzed. Maximum paralysis progresses rapidly (two to four days), and usually involves fever and muscle pain. Deep tendon reflex

A tendon or sinew is a tough band of dense fibrous connective tissue that connects muscle to bone. It sends the mechanical forces of muscle contraction to the skeletal system, while withstanding tension.

Tendons, like ligaments, are made o ...

es are also affected, and are typically absent or diminished; sensation

Sensation (psychology) refers to the processing of the senses by the sensory system.

Sensation or sensations may also refer to:

In arts and entertainment In literature

*Sensation (fiction), a fiction writing mode

*Sensation novel, a British ...

(the ability to feel) in the paralyzed limbs, however, is not affected.

The extent of spinal paralysis depends on the region of the cord affected, which may be cervical, thoracic

The thorax (: thoraces or thoraxes) or chest is a part of the anatomy of mammals and other tetrapod animals located between the neck and the abdomen.

In insects, crustaceans, and the extinct trilobites, the thorax is one of the three main ...

, or lumbar

In tetrapod anatomy, lumbar is an adjective that means of or pertaining to the abdominal segment of the torso, between the diaphragm (anatomy), diaphragm and the sacrum.

Naming and location

The lumbar region is sometimes referred to as the lowe ...

. The virus may affect muscles on both sides of the body, but more often the paralysis is asymmetrical

Asymmetry is the absence of, or a violation of, symmetry (the property of an object being invariant to a transformation, such as reflection). Symmetry is an important property of both physical and abstract systems and it may be displayed in pre ...

. Any limb or combination of limbs may be affected – one leg, one arm, or both legs and both arms. Paralysis is often more severe proximally (where the limb joins the body) than distally (the fingertips and toe

Toes are the digits of the foot of a tetrapod. Animal species such as cats that walk on their toes are described as being ''digitigrade''. Humans, and other animals that walk on the soles of their feet, are described as being ''plantigrade''; ...

s).

Bulbar polio

bulbar

The medulla oblongata or simply medulla is a long stem-like structure which makes up the lower part of the brainstem. It is anterior and partially inferior to the cerebellum. It is a cone-shaped neuronal mass responsible for autonomic (involun ...

region of the brain stem

The brainstem (or brain stem) is the posterior stalk-like part of the brain that connects the cerebrum with the spinal cord. In the human brain the brainstem is composed of the midbrain, the pons, and the medulla oblongata. The midbrain is co ...

. The bulbar region is a white matter

White matter refers to areas of the central nervous system that are mainly made up of myelinated axons, also called Nerve tract, tracts. Long thought to be passive tissue, white matter affects learning and brain functions, modulating the distr ...

pathway that connects the cerebral cortex

The cerebral cortex, also known as the cerebral mantle, is the outer layer of neural tissue of the cerebrum of the brain in humans and other mammals. It is the largest site of Neuron, neural integration in the central nervous system, and plays ...

to the brain stem. The destruction of these nerves weakens the muscles supplied by the cranial nerve

Cranial nerves are the nerves that emerge directly from the brain (including the brainstem), of which there are conventionally considered twelve pairs. Cranial nerves relay information between the brain and parts of the body, primarily to and f ...

s, producing symptoms of encephalitis

Encephalitis is inflammation of the Human brain, brain. The severity can be variable with symptoms including reduction or alteration in consciousness, aphasia, headache, fever, confusion, a stiff neck, and vomiting. Complications may include se ...

, and causes difficulty breathing, speaking and swallowing. Critical nerves affected are the glossopharyngeal nerve

The glossopharyngeal nerve (), also known as the ninth cranial nerve, cranial nerve IX, or simply CN IX, is a cranial nerve that exits the brainstem from the sides of the upper Medulla oblongata, medulla, just anterior (closer to the nose) to t ...

(which partially controls swallowing and functions in the throat, tongue movement, and taste), the vagus nerve

The vagus nerve, also known as the tenth cranial nerve (CN X), plays a crucial role in the autonomic nervous system, which is responsible for regulating involuntary functions within the human body. This nerve carries both sensory and motor fibe ...

(which sends signals to the heart, intestines, and lungs), and the accessory nerve

The accessory nerve, also known as the eleventh cranial nerve, cranial nerve XI, or simply CN XI, is a cranial nerve that supplies the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. It is classified as the eleventh of twelve pairs of cranial nerv ...

(which controls upper neck movement). Due to the effect on swallowing, secretions of mucus

Mucus (, ) is a slippery aqueous secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. It is typically produced from cells found in mucous glands, although it may also originate from mixed glands, which contain both Serous fluid, serous and muc ...

may build up in the airway, causing suffocation. Other signs and symptoms include facial weakness (caused by destruction of the trigeminal nerve

In neuroanatomy, the trigeminal nerve (literal translation, lit. ''triplet'' nerve), also known as the fifth cranial nerve, cranial nerve V, or simply CN V, is a cranial nerve responsible for Sense, sensation in the face and motor functions ...

and facial nerve

The facial nerve, also known as the seventh cranial nerve, cranial nerve VII, or simply CN VII, is a cranial nerve that emerges from the pons of the brainstem, controls the muscles of facial expression, and functions in the conveyance of ta ...

, which innervate the cheeks, tear duct

The nasolacrimal duct (also called the tear duct) carries tears from the lacrimal sac of the eye into the nasal cavity. The duct begins in the eye socket between the maxillary and lacrimal bones, from where it passes downwards and backwards. The o ...

s, gums, and muscles of the face, among other structures), double vision, difficulty in chewing, and abnormal respiratory rate

The respiratory rate is the rate at which breathing occurs; it is set and controlled by the respiratory center of the brain. A person's respiratory rate is usually measured in breaths per minute.

Measurement

The respiratory rate in humans is mea ...

, depth, and rhythm (which may lead to respiratory arrest

Respiratory arrest is a serious medical condition caused by apnea or respiratory dysfunction severe enough that it will not sustain the body (such as agonal breathing). Prolonged apnea refers to a patient who has stopped breathing for a long period ...

). Pulmonary edema

Pulmonary edema (British English: oedema), also known as pulmonary congestion, is excessive fluid accumulation in the tissue or air spaces (usually alveoli) of the lungs. This leads to impaired gas exchange, most often leading to shortness ...

and shock are also possible and may be fatal.

Bulbospinal polio

Approximately 19 percent of all paralytic polio cases have both bulbar and spinal symptoms; this subtype is called respiratory or bulbospinal polio. Here, the virus affects the upper part of the cervical spinal cord (cervical vertebrae

In tetrapods, cervical vertebrae (: vertebra) are the vertebrae of the neck, immediately below the skull. Truncal vertebrae (divided into thoracic and lumbar vertebrae in mammals) lie caudal (toward the tail) of cervical vertebrae. In saurop ...

C3 through C5), and paralysis of the diaphragm occurs. The critical nerves affected are the phrenic nerve

The phrenic nerve is a mixed nerve that originates from the C3–C5 spinal nerves in the neck. The nerve is important for breathing because it provides exclusive motor control of the diaphragm, the primary muscle of respiration. In humans, t ...

(which drives the diaphragm to inflate the lungs

The lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system in many animals, including humans. In mammals and most other tetrapods, two lungs are located near the backbone on either side of the heart. Their function in the respiratory syste ...

) and those that drive the muscles needed for swallowing. By destroying these nerves, this form of polio affects breathing, making it difficult or impossible for the patient to breathe without the support of a ventilator

A ventilator is a type of breathing apparatus, a class of medical technology that provides mechanical ventilation by moving breathable air into and out of the lungs, to deliver breaths to a patient who is physically unable to breathe, or breathi ...

. It can lead to paralysis of the arms and legs and may also affect swallowing and heart functions.

Diagnosis

Paralytic poliomyelitis may be clinically suspected in individuals experiencing acute onset of flaccid paralysis in one or more limbs with decreased or absent tendon reflexes in the affected limbs that cannot be attributed to another apparent cause, and without sensory orcognitive

Cognition is the "mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses". It encompasses all aspects of intellectual functions and processes such as: perception, attention, thought, ...

loss.

A laboratory diagnosis is usually made based on the recovery of poliovirus from a stool sample or a swab of the pharynx

The pharynx (: pharynges) is the part of the throat behind the human mouth, mouth and nasal cavity, and above the esophagus and trachea (the tubes going down to the stomach and the lungs respectively). It is found in vertebrates and invertebrates ...

. Rarely, it may be possible to identify poliovirus in the blood or in the cerebrospinal fluid

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a clear, colorless Extracellular fluid#Transcellular fluid, transcellular body fluid found within the meninges, meningeal tissue that surrounds the vertebrate brain and spinal cord, and in the ventricular system, ven ...

. Poliovirus samples are further analysed using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is a laboratory technique combining reverse transcription of RNA into DNA (in this context called complementary DNA or cDNA) and amplification of specific DNA targets using polymerase cha ...

(RT-PCR) or genomic sequencing

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, thymine, cytosine, and guanine. The ...

to determine the serotype (i.e., 1, 2, or 3), and whether the virus is a wild or vaccine-derived strain.

Prevention

Passive immunization

In 1950, William Hammon at theUniversity of Pittsburgh

The University of Pittsburgh (Pitt) is a Commonwealth System of Higher Education, state-related research university in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States. The university is composed of seventeen undergraduate and graduate schools and colle ...

purified the gamma globulin

Gamma globulins are a class of globulins, identified by their position after serum protein electrophoresis. The most significant gamma globulins are immunoglobulins (antibodies), although some immunoglobulins are not gamma globulins, and some ...

component of the blood plasma

Blood plasma is a light Amber (color), amber-colored liquid component of blood in which blood cells are absent, but which contains Blood protein, proteins and other constituents of whole blood in Suspension (chemistry), suspension. It makes up ...

of polio survivors. Hammon proposed the gamma globulin, which contained antibodies to poliovirus, could be used to halt poliovirus infection, prevent disease, and reduce the severity of disease in other patients who had contracted polio. The results of a large clinical trial

Clinical trials are prospective biomedical or behavioral research studies on human subject research, human participants designed to answer specific questions about biomedical or behavioral interventions, including new treatments (such as novel v ...

were promising; the gamma globulin was shown to be about 80 percent effective in preventing the development of paralytic poliomyelitis. It was also shown to reduce the severity of the disease in patients who developed polio. Due to the limited supply of blood plasma gamma globulin was later deemed impractical for widespread use and the medical community focused on the development of a polio vaccine.

Vaccine

Two types of vaccine are used throughout the world to combat polio: an inactivated poliovirus given by injection, and a weakened poliovirus given by mouth. Both types induce immunity to polio and are effective in protecting individuals from disease.

The inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) was developed in 1952 by

Two types of vaccine are used throughout the world to combat polio: an inactivated poliovirus given by injection, and a weakened poliovirus given by mouth. Both types induce immunity to polio and are effective in protecting individuals from disease.

The inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) was developed in 1952 by Jonas Salk

Jonas Edward Salk (; born Jonas Salk; October 28, 1914June 23, 1995) was an American virologist and medical researcher who developed one of the first successful polio vaccines. He was born in New York City and attended the City College of New ...

at the University of Pittsburgh, and announced to the world on 12 April 1955. The Salk vaccine is based on poliovirus grown in a type of monkey kidney tissue culture

Tissue culture is the growth of tissue (biology), tissues or cell (biology), cells in an artificial medium separate from the parent organism. This technique is also called micropropagation. This is typically facilitated via use of a liquid, semi-s ...

(vero cell

Vero cells are a lineage of cells used in cell cultures. The 'Vero' lineage was isolated from kidney epithelial cells extracted from an African green monkey ('' Chlorocebus'' sp.; formerly called ''Cercopithecus aethiops'', this group of monk ...

line), which is chemically inactivated with formalin

Formaldehyde ( , ) (systematic name methanal) is an organic compound with the chemical formula and structure , more precisely . The compound is a pungent, colourless gas that polymerises spontaneously into paraformaldehyde. It is stored as ...

. After two doses of IPV (given by injection

Injection or injected may refer to:

Science and technology

* Injective function, a mathematical function mapping distinct arguments to distinct values

* Injection (medicine), insertion of liquid into the body with a syringe

* Injection, in broadca ...

), 90 percent or more of individuals develop protective antibody to all three serotype

A serotype or serovar is a distinct variation within a species of bacteria or virus or among immune cells of different individuals. These microorganisms, viruses, or Cell (biology), cells are classified together based on their shared reactivity ...

s of poliovirus, and at least 99 percent are immune to poliovirus following three doses.

Subsequently, Albert Sabin developed a polio vaccine that can be administered orally (oral polio vaccine - OPV), comprising a live, attenuated virus. It was produced by the repeated passage of the virus through nonhuman cells at subphysiological

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

temperatures. The attenuated poliovirus in the Sabin vaccine replicates very efficiently in the gut, the primary site of wild poliovirus infection and replication, but the vaccine strain is unable to replicate efficiently within nervous system

In biology, the nervous system is the complex system, highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its behavior, actions and sense, sensory information by transmitting action potential, signals to and from different parts of its body. Th ...

tissue. A single dose of Sabin's trivalent OPV produces immunity to all three poliovirus serotypes in about 50 percent of recipients. Three doses of OPV produce protective antibody to all three poliovirus types in more than 95 percent of recipients. Human trials of Sabin's vaccine began in 1957, and in 1958, it was selected, in competition with the live attenuated vaccines of Koprowski and other researchers, by the US National Institutes of Health. Accessed 16 December 2009. Licensed in 1962, it rapidly became the only oral polio vaccine used worldwide.

OPV efficiently blocks person-to-person transmission of wild poliovirus by oral–oral and fecal–oral routes, thereby protecting both individual vaccine recipients and the wider community. The live attenuated virus may be transmitted from vaccinees to their unvaccinated contacts, resulting in wider community immunity. IPV confers good immunity but is less effective at preventing spread of wild poliovirus by the fecal–oral route.

endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

), it has been the vaccine of choice for controlling poliomyelitis in many countries. On very rare occasions, the attenuated virus in the Sabin OPV can revert into a form that can paralyze. In 2017, cases caused by vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV) outnumbered wild poliovirus cases for the first time, due to wild polio cases hitting record lows. Most industrialized countries have switched to inactivated polio vaccine, which cannot revert, either as the sole vaccine against poliomyelitis or in combination with oral polio vaccine.

An improved oral vaccine (Novel oral polio vaccine type 2 - nOPV2) began development in 2011 and was granted emergency licensing in 2021, and subsequently full licensure in December 2023. This has greater genetic stability than the traditional oral vaccine and is less likely to revert to a virulent form.

Treatment

There is nocure

A cure is a substance or procedure that resolves a medical condition. This may include a medication, a surgery, surgical operation, a lifestyle change, or even a philosophical shift that alleviates a person's suffering or achieves a state of heali ...

for polio, but there are treatments. The focus of modern treatment has been on providing relief of symptoms, speeding recovery and preventing complications. Supportive measures include antibiotics

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting pathogenic bacteria, bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the therapy ...

to prevent infections in weakened muscles, analgesics

An analgesic drug, also called simply an analgesic, antalgic, pain reliever, or painkiller, is any member of the group of drugs used for pain management. Analgesics are conceptually distinct from anesthetics, which temporarily reduce, and in s ...

for pain, moderate exercise and a nutritious diet. Treatment of polio often requires long-term rehabilitation, including occupational therapy

Occupational therapy (OT), also known as ergotherapy, is a healthcare profession. Ergotherapy is derived from the Greek wiktionary:ergon, ergon which is allied to work, to act and to be active. Occupational therapy is based on the assumption t ...

, physical therapy

Physical therapy (PT), also known as physiotherapy, is a healthcare profession, as well as the care provided by physical therapists who promote, maintain, or restore health through patient education, physical intervention, disease preventio ...

, braces, corrective shoes and, in some cases, orthopedic surgery

Orthopedic surgery or orthopedics ( alternative spelling orthopaedics) is the branch of surgery concerned with conditions involving the musculoskeletal system. Orthopedic surgeons use both surgical and nonsurgical means to treat musculoskeletal ...

.

Portable ventilator

A ventilator is a type of breathing apparatus, a class of medical technology that provides mechanical ventilation by moving breathable air into and out of the lungs, to deliver breaths to a patient who is physically unable to breathe, or breathi ...

s may be required to support breathing. Historically, a noninvasive, negative-pressure ventilator, more commonly called an iron lung

An iron lung is a type of negative pressure ventilator, a medical ventilator, mechanical respirator which encloses most of a person's body and varies the air pressure in the enclosed space to stimulate breathing. It assists breathing when Musc ...

, was used to artificially maintain respiration during an acute polio infection until a person could breathe independently (generally about one to two weeks). The use of iron lungs is largely obsolete in modern medicine as more modern breathing therapies have been developed and due to the eradication of polio in most of the world.

Other historical treatments for polio include hydrotherapy

Hydrotherapy, formerly called hydropathy and also called water cure, is a branch of alternative medicine (particularly naturopathy), occupational therapy, and Physical therapy, physiotherapy, that involves the use of water for pain relief and ...

, electrotherapy, massage and passive motion exercises, and surgical treatments, such as tendon lengthening and nerve grafting.

Prognosis

Patients with abortive polio infections recover completely. In those who develop only aseptic meningitis, the symptoms can be expected to persist for two to ten days, followed by complete recovery. In cases of spinal polio, if the affected nerve cells are completely destroyed, paralysis will be permanent; cells that are not destroyed, but lose function temporarily, may recover within four to six weeks after onset. Reproduced online with permission by Post-Polio Health International; retrieved on 10 November 2007. Half the patients with spinal polio recover fully; one-quarter recover with mild disability, and the remaining quarter are left with severe disability. The degree of both acute paralysis and residual paralysis is likely to be proportional to the degree of viremia, and

Patients with abortive polio infections recover completely. In those who develop only aseptic meningitis, the symptoms can be expected to persist for two to ten days, followed by complete recovery. In cases of spinal polio, if the affected nerve cells are completely destroyed, paralysis will be permanent; cells that are not destroyed, but lose function temporarily, may recover within four to six weeks after onset. Reproduced online with permission by Post-Polio Health International; retrieved on 10 November 2007. Half the patients with spinal polio recover fully; one-quarter recover with mild disability, and the remaining quarter are left with severe disability. The degree of both acute paralysis and residual paralysis is likely to be proportional to the degree of viremia, and inversely proportional

In mathematics, two sequences of numbers, often experimental data, are proportional or directly proportional if their corresponding elements have a constant ratio. The ratio is called ''coefficient of proportionality'' (or ''proportionality ...

to the degree of immunity

Immunity may refer to:

Medicine

* Immunity (medical), resistance of an organism to infection or disease

* ''Immunity'' (journal), a scientific journal published by Cell Press

Biology

* Immune system

Engineering

* Radiofrequence immunity ...

. Spinal polio is rarely fatal.

Without respiratory support, consequences of poliomyelitis with respiratory

The respiratory system (also respiratory apparatus, ventilatory system) is a biological system consisting of specific organs and structures used for gas exchange in animals and plants. The anatomy and physiology that make this happen varies gr ...

involvement include suffocation or pneumonia from aspiration of secretions. Overall, 5 to 10 percent of patients with paralytic polio die due to the paralysis of muscles used for breathing. The case fatality rate

In epidemiology, case fatality rate (CFR) – or sometimes more accurately case-fatality risk – is the proportion of people who have been diagnosed with a certain disease and end up dying of it. Unlike a disease's mortality rate, the CFR does ...

(CFR) varies by age: 2 to 5 percent of children and up to 15 to 30 percent of adults die. Bulbar polio often causes death if respiratory support is not provided; with support, its CFR ranges from 25 to 75 percent, depending on the age of the patient. When intermittent positive pressure ventilation is available, the fatalities can be reduced to 15 percent.

Recovery

Many cases of poliomyelitis result in only temporary paralysis. Generally in these cases, nerve impulses return to the paralyzed muscle within a month, and recovery is complete in six to eight months. Theneurophysiological

Neurophysiology is a branch of physiology and neuroscience concerned with the functions of the nervous system and their mechanisms. The term ''neurophysiology'' originates from the Greek word ''νεῦρον'' ("nerve") and ''physiology'' (whic ...

processes involved in recovery following acute paralytic poliomyelitis are quite effective; muscles are able to retain normal strength even if half the original motor neurons have been lost. Paralysis remaining after one year is likely to be permanent, although some recovery of muscle strength is possible up to 18 months after infection.

One mechanism involved in recovery is nerve terminal sprouting, in which remaining brainstem and spinal cord motor neurons develop new branches, or axonal sprouts. These sprouts can reinnervate

Reinnervation is the restoration, either by spontaneous cellular regeneration or by surgical grafting, of nerve supply to a body part from which it has been lost or damaged.

See also

* Denervation

* Neuroregeneration

Neuroregeneration is the r ...

orphaned muscle fibers that have been denervated by acute polio infection, restoring the fibers' capacity to contract and improving strength. Terminal sprouting may generate a few significantly enlarged motor neurons doing work previously performed by as many as four or five units: a single motor neuron that once controlled 200 muscle cells might control 800 to 1000 cells. Other mechanisms that occur during the rehabilitation phase, and contribute to muscle strength restoration, include myofiber hypertrophy – enlargement of muscle fibers through exercise and activity – and transformation of type II muscle fibers to type I muscle fibers.

In addition to these physiological processes, the body can compensate for residual paralysis in other ways. Weaker muscles can be used at a higher than usual intensity relative to the muscle's maximal capacity, little-used muscles can be developed, and ligament

A ligament is a type of fibrous connective tissue in the body that connects bones to other bones. It also connects flight feathers to bones, in dinosaurs and birds. All 30,000 species of amniotes (land animals with internal bones) have liga ...

s can enable stability and mobility.

Complications

Residual complications of paralytic polio often occur following the initial recovery process. Muscleparesis

In medicine, paresis (), compound word from Greek , (πᾰρᾰ- “beside” + ἵημι “let go, release”), is a condition typified by a weakness of voluntary movement, or by partial loss of voluntary movement or by impaired movement. Whe ...

and paralysis can sometimes result in skeletal

A skeleton is the structural frame that supports the body of most animals. There are several types of skeletons, including the exoskeleton, which is a rigid outer shell that holds up an organism's shape; the endoskeleton, a rigid internal fram ...

deformities, tightening of the joints, and movement disability. Once the muscles in the limb become flaccid, they may interfere with the function of other muscles. A typical manifestation of this problem is equinus foot (similar to club foot

Clubfoot is a congenital or acquired defect where one or both feet are supinated, rotated inward and plantar flexion, downward. Congenital clubfoot is the most common congenital malformation of the foot with an incidence of 1 per 1000 births. ...

). This deformity develops when the muscles that pull the toes downward are working, but those that pull it upward are not, and the foot naturally tends to drop toward the ground. If the problem is left untreated, the Achilles tendon

The Achilles tendon or heel cord, also known as the calcaneal tendon, is a tendon at the back of the lower leg, and is the thickest in the human body. It serves to attach the plantaris, gastrocnemius (calf) and soleus muscles to the calcane ...

s at the back of the foot retract and the foot cannot take on a normal position. People with polio that develop equinus foot cannot walk properly because they cannot put their heels on the ground. A similar situation can develop if the arms become paralyzed.

In some cases the growth of an affected leg is slowed by polio, while the other leg continues to grow normally. The result is that one leg is shorter than the other and the person limps and leans to one side, in turn leading to deformities of the spine (such as scoliosis

Scoliosis (: scolioses) is a condition in which a person's Vertebral column, spine has an irregular curve in the coronal plane. The curve is usually S- or C-shaped over three dimensions. In some, the degree of curve is stable, while in others ...

). Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disorder characterized by low bone mass, micro-architectural deterioration of bone tissue leading to more porous bone, and consequent increase in Bone fracture, fracture risk.

It is the most common reason f ...

and increased likelihood of bone fracture

A bone fracture (abbreviated FRX or Fx, Fx, or #) is a medical condition in which there is a partial or complete break in the continuity of any bone in the body. In more severe cases, the bone may be broken into several fragments, known as a ''c ...

s may occur. An intervention to prevent or lessen length disparity can be to perform an epiphysiodesis on the distal femoral and proximal tibial/fibular condyles, so that limb's growth is artificially stunted, and by the time of epiphyseal (growth) plate closure, the legs are more equal in length. Alternatively, a person can be fitted with custom-made footwear which corrects the difference in leg lengths. Other surgery to re-balance muscular agonist/antagonist imbalances may also be helpful. Extended use of braces or wheelchairs may cause compression neuropathy, as well as a loss of proper function of the vein

Veins () are blood vessels in the circulatory system of humans and most other animals that carry blood towards the heart. Most veins carry deoxygenated blood from the tissues back to the heart; exceptions are those of the pulmonary and feta ...

s in the legs, due to pooling of blood in paralyzed lower limbs. Complications from prolonged immobility involving the lungs

The lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system in many animals, including humans. In mammals and most other tetrapods, two lungs are located near the backbone on either side of the heart. Their function in the respiratory syste ...

, kidney

In humans, the kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped blood-filtering organ (anatomy), organs that are a multilobar, multipapillary form of mammalian kidneys, usually without signs of external lobulation. They are located on the left and rig ...

s and heart

The heart is a muscular Organ (biology), organ found in humans and other animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels. The heart and blood vessels together make the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrie ...

include pulmonary edema

Pulmonary edema (British English: oedema), also known as pulmonary congestion, is excessive fluid accumulation in the tissue or air spaces (usually alveoli) of the lungs. This leads to impaired gas exchange, most often leading to shortness ...

, aspiration pneumonia

Aspiration pneumonia is a type of lung infection that is due to a relatively large amount of material from the stomach or mouth entering the lungs. Signs and symptoms often include fever and cough of relatively rapid onset. Complications may incl ...

, urinary tract infection

A urinary tract infection (UTI) is an infection that affects a part of the urinary tract. Lower urinary tract infections may involve the bladder (cystitis) or urethra (urethritis) while upper urinary tract infections affect the kidney (pyel ...

s, kidney stone

Kidney stone disease (known as nephrolithiasis, renal calculus disease, or urolithiasis) is a crystallopathy and occurs when there are too many minerals in the urine and not enough liquid or hydration. This imbalance causes tiny pieces of cr ...

s, paralytic ileus, myocarditis

Myocarditis is inflammation of the cardiac muscle. Myocarditis can progress to inflammatory cardiomyopathy when there is associated ventricular remodeling and cardiac dysfunction due to chronic inflammation. Symptoms can include shortness of bre ...

and cor pulmonale.

Post-polio syndrome

Between 25 percent and 50 percent of individuals who have recovered from paralytic polio in childhood can develop additional symptoms decades after recovering from the acute infection, notably new muscle weakness and extreme fatigue. This condition is known aspost-polio syndrome

Post-polio syndrome (PPS, poliomyelitis sequelae) is a group of latent symptoms of poliomyelitis (polio), occurring in more than 80% of polio infections. The symptoms are caused by the damaging effects of the viral infection on the nervous syst ...

(PPS) or post-polio sequelae. The symptoms of PPS are thought to involve a failure of the oversized motor unit

In biology, a motor unit is made up of a motor neuron and all of the skeletal muscle fibers innervated by the neuron's axon terminals, including the neuromuscular junctions between the neuron and the fibres. Groups of motor units often work tog ...

s created during the recovery phase of the paralytic disease. Contributing factors that increase the risk of PPS include aging with loss of neuron units, the presence of a permanent residual impairment after recovery from the acute illness, and both overuse and disuse of neurons. PPS is a slow, progressive disease, and there is no specific treatment for it. Post-polio syndrome is not an infectious process, and persons experiencing the syndrome do not shed poliovirus.

Orthotics

Paralysis, length differences and deformations of the lower extremities can lead to a hindrance when walking with compensation mechanisms that lead to a severe impairment of the gait pattern. In order to be able to stand and walk safely and to improve the gait pattern,

Paralysis, length differences and deformations of the lower extremities can lead to a hindrance when walking with compensation mechanisms that lead to a severe impairment of the gait pattern. In order to be able to stand and walk safely and to improve the gait pattern, orthotics