Induced Fission on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Nuclear fission is a

Nuclear fission is a

Fission cross sections are a measurable property related to the probability that fission will occur in a nuclear reaction. Cross sections are a function of incident neutron energy, and those for and are a million times higher than at lower neutron energy levels. Absorption of any neutron makes available to the nucleus binding energy of about 5.3 MeV. needs a fast neutron to supply the additional 1 MeV needed to cross the critical energy barrier for fission. In the case of however, that extra energy is provided when adjusts from an odd to an even mass. In the words of Younes and Lovelace, "...the neutron absorption on a target forms a nucleus with excitation energy greater than the critical fission energy, whereas in the case of ''n'' + , the resulting nucleus has an excitation energy below the critical fission energy."

About 6 MeV of the fission-input energy is supplied by the simple binding of an extra neutron to the heavy nucleus via the strong force; however, in many fissionable isotopes, this amount of energy is not enough for fission. Uranium-238, for example, has a near-zero fission cross section for neutrons of less than 1 MeV energy. If no additional energy is supplied by any other mechanism, the nucleus will not fission, but will merely absorb the neutron, as happens when absorbs slow and even some fraction of fast neutrons, to become . The remaining energy to initiate fission can be supplied by two other mechanisms: one of these is more kinetic energy of the incoming neutron, which is increasingly able to fission a

Fission cross sections are a measurable property related to the probability that fission will occur in a nuclear reaction. Cross sections are a function of incident neutron energy, and those for and are a million times higher than at lower neutron energy levels. Absorption of any neutron makes available to the nucleus binding energy of about 5.3 MeV. needs a fast neutron to supply the additional 1 MeV needed to cross the critical energy barrier for fission. In the case of however, that extra energy is provided when adjusts from an odd to an even mass. In the words of Younes and Lovelace, "...the neutron absorption on a target forms a nucleus with excitation energy greater than the critical fission energy, whereas in the case of ''n'' + , the resulting nucleus has an excitation energy below the critical fission energy."

About 6 MeV of the fission-input energy is supplied by the simple binding of an extra neutron to the heavy nucleus via the strong force; however, in many fissionable isotopes, this amount of energy is not enough for fission. Uranium-238, for example, has a near-zero fission cross section for neutrons of less than 1 MeV energy. If no additional energy is supplied by any other mechanism, the nucleus will not fission, but will merely absorb the neutron, as happens when absorbs slow and even some fraction of fast neutrons, to become . The remaining energy to initiate fission can be supplied by two other mechanisms: one of these is more kinetic energy of the incoming neutron, which is increasingly able to fission a

When a

When a

"The Hydrogen Bomb"

''Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists'', p. 99. appears as the fission energy of ~200 MeV. For uranium-235 (total mean fission energy 202.79 MeV), typically ~169 MeV appears as the kinetic energy of the daughter nuclei, which fly apart at about 3% of the speed of light, due to

The binding energy of the nucleus is the difference between the rest-mass energy of the nucleus and the rest-mass energy of the neutron and proton nucleons. The binding energy formula includes volume, surface and Coulomb energy terms that include empirically derived coefficients for all three, plus energy ratios of a deformed nucleus relative to a spherical form for the surface and Coulomb terms. Additional terms can be included such as symmetry, pairing, the finite range of the nuclear force, and charge distribution within the nuclei to improve the estimate. Normally binding energy is referred to and plotted as average binding energy per nucleon.

According to Lilley, "The binding energy of a nucleus is the energy required to separate it into its constituent neutrons and protons."

where is

The binding energy of the nucleus is the difference between the rest-mass energy of the nucleus and the rest-mass energy of the neutron and proton nucleons. The binding energy formula includes volume, surface and Coulomb energy terms that include empirically derived coefficients for all three, plus energy ratios of a deformed nucleus relative to a spherical form for the surface and Coulomb terms. Additional terms can be included such as symmetry, pairing, the finite range of the nuclear force, and charge distribution within the nuclei to improve the estimate. Normally binding energy is referred to and plotted as average binding energy per nucleon.

According to Lilley, "The binding energy of a nucleus is the energy required to separate it into its constituent neutrons and protons."

where is

John Lilley states, "...neutron-induced fission generates extra neutrons which can induce further fissions in the next generation and so on in a chain reaction. The chain reaction is characterized by the ''neutron multiplication factor k'', which is defined as the ratio of the number of neutrons in one generation to the number in the preceding generation. If, in a reactor, ''k'' is less than unity, the reactor is subcritical, the number of neutrons decreases and the chain reaction dies out. If ''k'' > 1, the reactor is supercritical and the chain reaction diverges. This is the situation in a fission bomb where growth is at an explosive rate. If ''k'' is exactly unity, the reactions proceed at a steady rate and the reactor is said to be critical. It is possible to achieve criticality in a reactor using natural uranium as fuel, provided that the neutrons have been efficiently moderated to thermal energies." Moderators include light water,

John Lilley states, "...neutron-induced fission generates extra neutrons which can induce further fissions in the next generation and so on in a chain reaction. The chain reaction is characterized by the ''neutron multiplication factor k'', which is defined as the ratio of the number of neutrons in one generation to the number in the preceding generation. If, in a reactor, ''k'' is less than unity, the reactor is subcritical, the number of neutrons decreases and the chain reaction dies out. If ''k'' > 1, the reactor is supercritical and the chain reaction diverges. This is the situation in a fission bomb where growth is at an explosive rate. If ''k'' is exactly unity, the reactions proceed at a steady rate and the reactor is said to be critical. It is possible to achieve criticality in a reactor using natural uranium as fuel, provided that the neutrons have been efficiently moderated to thermal energies." Moderators include light water,

Critical fission reactors are the most common type of nuclear reactor. In a critical fission reactor, neutrons produced by fission of fuel atoms are used to induce yet more fissions, to sustain a controllable amount of energy release. Devices that produce engineered but non-self-sustaining fission reactions are subcritical fission reactors. Such devices use radioactive decay or

Critical fission reactors are the most common type of nuclear reactor. In a critical fission reactor, neutrons produced by fission of fuel atoms are used to induce yet more fissions, to sustain a controllable amount of energy release. Devices that produce engineered but non-self-sustaining fission reactions are subcritical fission reactors. Such devices use radioactive decay or

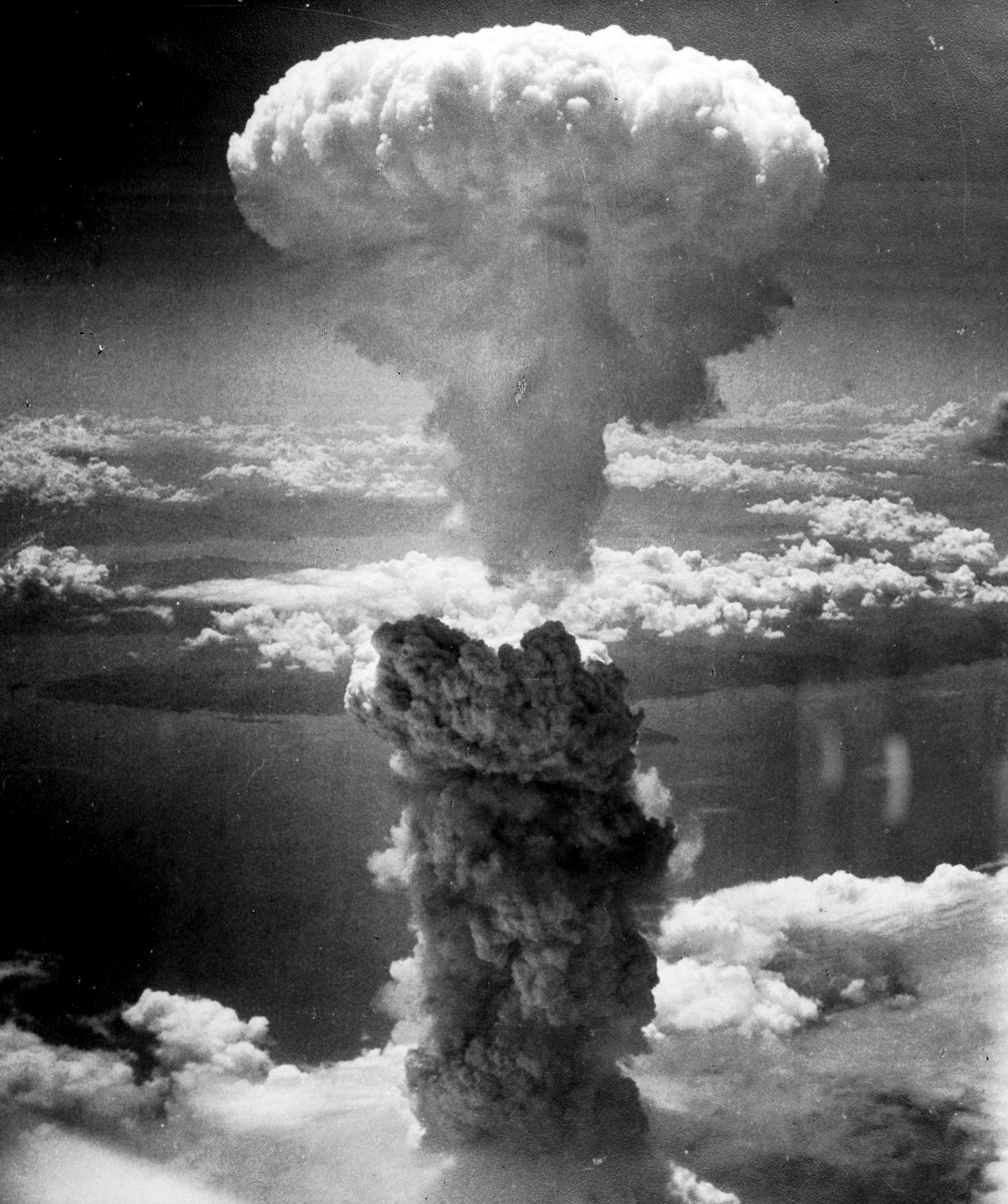

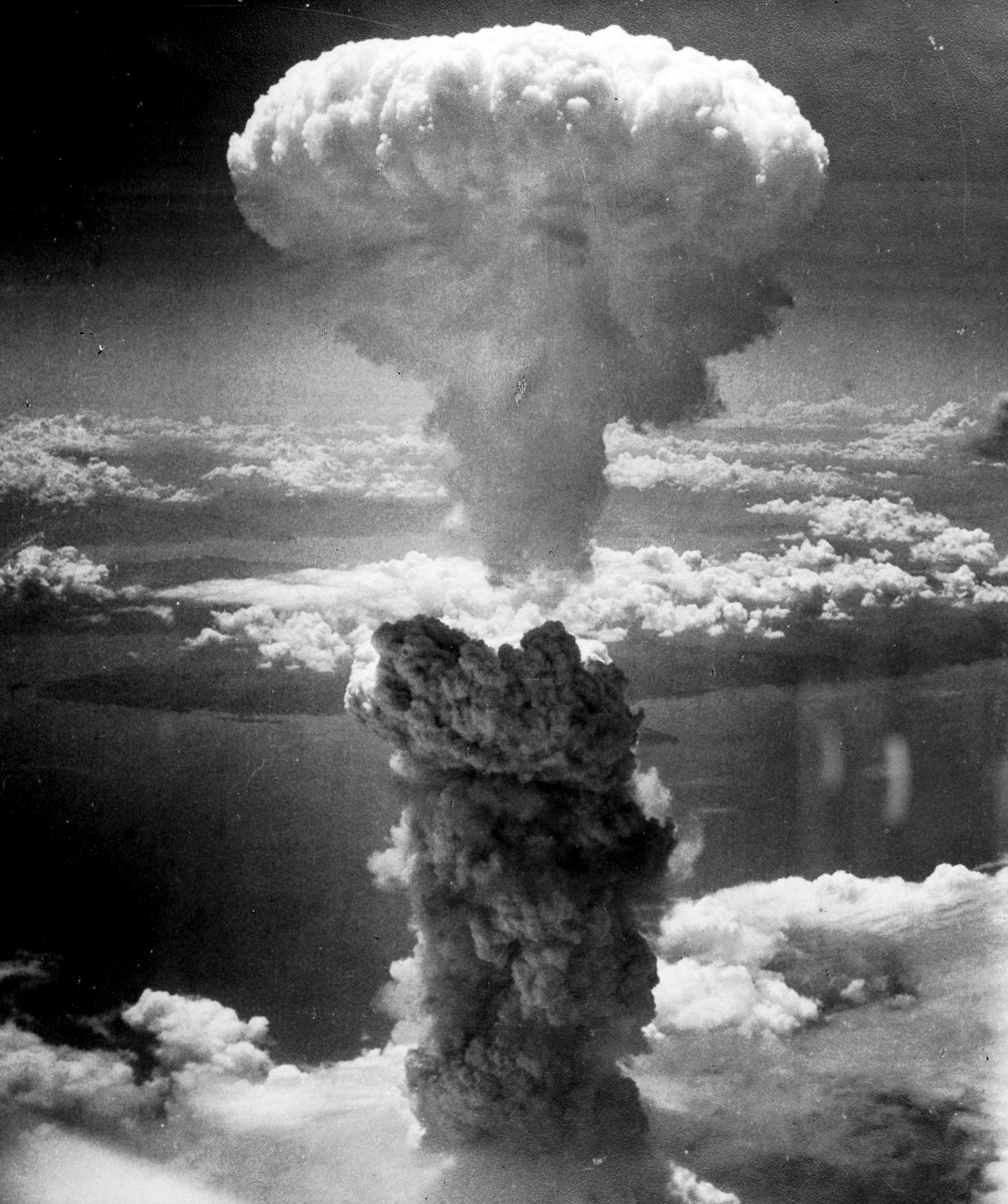

The objective of an atomic bomb is to produce a device, according to Serber, "...in which energy is released by a fast neutron chain reaction in one or more of the materials known to show nuclear fission." According to Rhodes, "Untamped, a bomb core even as large as twice the

The objective of an atomic bomb is to produce a device, according to Serber, "...in which energy is released by a fast neutron chain reaction in one or more of the materials known to show nuclear fission." According to Rhodes, "Untamped, a bomb core even as large as twice the

The discovery of nuclear fission occurred in 1938 in the buildings of the

The discovery of nuclear fission occurred in 1938 in the buildings of the  After the Fermi publication,

After the Fermi publication,

With the news of fission neutrons from uranium fission, Szilárd immediately understood the possibility of a nuclear chain reaction using uranium. In the summer, Fermi and Szilard proposed the idea of a nuclear reactor (pile) to mediate this process. The pile would use natural uranium as fuel. Fermi had shown much earlier that neutrons were far more effectively captured by atoms if they were of low energy (so-called "slow" or "thermal" neutrons), because for quantum reasons it made the atoms look like much larger targets to the neutrons. Thus to slow down the secondary neutrons released by the fissioning uranium nuclei, Fermi and Szilard proposed a graphite "moderator", against which the fast, high-energy secondary neutrons would collide, effectively slowing them down. With enough uranium, and with sufficiently pure graphite, their "pile" could theoretically sustain a slow-neutron chain reaction. This would result in the production of heat, as well as the creation of radioactive fission products.

In August 1939, Szilard, Teller and

With the news of fission neutrons from uranium fission, Szilárd immediately understood the possibility of a nuclear chain reaction using uranium. In the summer, Fermi and Szilard proposed the idea of a nuclear reactor (pile) to mediate this process. The pile would use natural uranium as fuel. Fermi had shown much earlier that neutrons were far more effectively captured by atoms if they were of low energy (so-called "slow" or "thermal" neutrons), because for quantum reasons it made the atoms look like much larger targets to the neutrons. Thus to slow down the secondary neutrons released by the fissioning uranium nuclei, Fermi and Szilard proposed a graphite "moderator", against which the fast, high-energy secondary neutrons would collide, effectively slowing them down. With enough uranium, and with sufficiently pure graphite, their "pile" could theoretically sustain a slow-neutron chain reaction. This would result in the production of heat, as well as the creation of radioactive fission products.

In August 1939, Szilard, Teller and

The Effects of Nuclear WeaponsAnnotated bibliography for nuclear fission from the Alsos Digital Library

Historical account complete with audio and teacher's guides from the American Institute of Physics History Center

atomicarchive.com

Nuclear Fission Explained

What is Nuclear Fission?

Nuclear Fission Animation

{{DEFAULTSORT:Nuclear Fission Nuclear fission Fission, nuclear Nuclear chemistry Neutron sources Radioactivity 1938 in science German inventions German inventions of the Nazi period Austrian inventions

reaction

Reaction may refer to a process or to a response to an action, event, or exposure.

Physics and chemistry

*Chemical reaction

*Nuclear reaction

*Reaction (physics), as defined by Newton's third law

* Chain reaction (disambiguation)

Biology and ...

in which the nucleus

Nucleus (: nuclei) is a Latin word for the seed inside a fruit. It most often refers to:

*Atomic nucleus, the very dense central region of an atom

*Cell nucleus, a central organelle of a eukaryotic cell, containing most of the cell's DNA

Nucleu ...

of an atom

Atoms are the basic particles of the chemical elements. An atom consists of a atomic nucleus, nucleus of protons and generally neutrons, surrounded by an electromagnetically bound swarm of electrons. The chemical elements are distinguished fr ...

splits into two or more smaller nuclei. The fission process often produces gamma

Gamma (; uppercase , lowercase ; ) is the third letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals it has a value of 3. In Ancient Greek, the letter gamma represented a voiced velar stop . In Modern Greek, this letter normally repr ...

photon

A photon () is an elementary particle that is a quantum of the electromagnetic field, including electromagnetic radiation such as light and radio waves, and the force carrier for the electromagnetic force. Photons are massless particles that can ...

s, and releases a very large amount of energy

Energy () is the physical quantity, quantitative physical property, property that is transferred to a physical body, body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of Work (thermodynamics), work and in the form of heat and l ...

even by the energetic standards of radioactive decay

Radioactive decay (also known as nuclear decay, radioactivity, radioactive disintegration, or nuclear disintegration) is the process by which an unstable atomic nucleus loses energy by radiation. A material containing unstable nuclei is conside ...

.

Nuclear fission was discovered by chemists Otto Hahn

Otto Hahn (; 8 March 1879 – 28 July 1968) was a German chemist who was a pioneer in the field of radiochemistry. He is referred to as the father of nuclear chemistry and discoverer of nuclear fission, the science behind nuclear reactors and ...

and Fritz Strassmann

Friedrich Wilhelm Strassmann (; 22 February 1902 – 22 April 1980) was a German chemist who, with Otto Hahn in December 1938, identified the element barium as a product of the bombardment of uranium with neutrons. Their observation was the key ...

and physicists Lise Meitner

Elise Lise Meitner ( ; ; 7 November 1878 – 27 October 1968) was an Austrian-Swedish nuclear physicist who was instrumental in the discovery of nuclear fission.

After completing her doctoral research in 1906, Meitner became the second woman ...

and Otto Robert Frisch

Otto Robert Frisch (1 October 1904 – 22 September 1979) was an Austrian-born British physicist who worked on nuclear physics. With Otto Stern and Immanuel Estermann, he first measured the magnetic moment of the proton. With his aunt, Lise M ...

. Hahn and Strassmann proved that a fission reaction had taken place on 19 December 1938, and Meitner and her nephew Frisch explained it theoretically in January 1939. Frisch named the process "fission" by analogy with biological fission of living cells. In their second publication on nuclear fission in February 1939, Hahn and Strassmann predicted the existence and liberation of additional neutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , that has no electric charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. The Discovery of the neutron, neutron was discovered by James Chadwick in 1932, leading to the discovery of nucle ...

s during the fission process, opening up the possibility of a nuclear chain reaction

In nuclear physics, a nuclear chain reaction occurs when one single nuclear reaction causes an average of one or more subsequent nuclear reactions, thus leading to the possibility of a self-propagating series or "positive feedback loop" of thes ...

.

For heavy nuclide

Nuclides (or nucleides, from nucleus, also known as nuclear species) are a class of atoms characterized by their number of protons, ''Z'', their number of neutrons, ''N'', and their nuclear energy state.

The word ''nuclide'' was coined by the A ...

s, it is an exothermic reaction

In thermochemistry, an exothermic reaction is a "reaction for which the overall standard enthalpy change Δ''H''⚬ is negative." Exothermic reactions usually release heat. The term is often confused with exergonic reaction, which IUPAC define ...

which can release large amounts of energy both as electromagnetic radiation

In physics, electromagnetic radiation (EMR) is a self-propagating wave of the electromagnetic field that carries momentum and radiant energy through space. It encompasses a broad spectrum, classified by frequency or its inverse, wavelength ...

and as kinetic energy

In physics, the kinetic energy of an object is the form of energy that it possesses due to its motion.

In classical mechanics, the kinetic energy of a non-rotating object of mass ''m'' traveling at a speed ''v'' is \fracmv^2.Resnick, Rober ...

of the fragments (heat

In thermodynamics, heat is energy in transfer between a thermodynamic system and its surroundings by such mechanisms as thermal conduction, electromagnetic radiation, and friction, which are microscopic in nature, involving sub-atomic, ato ...

ing the bulk material where fission takes place). Like nuclear fusion

Nuclear fusion is a nuclear reaction, reaction in which two or more atomic nuclei combine to form a larger nuclei, nuclei/neutrons, neutron by-products. The difference in mass between the reactants and products is manifested as either the rele ...

, for fission to produce energy, the total binding energy

In physics and chemistry, binding energy is the smallest amount of energy required to remove a particle from a system of particles or to disassemble a system of particles into individual parts. In the former meaning the term is predominantly use ...

of the resulting elements must be greater than that of the starting element. The fission barrier

In nuclear physics and nuclear chemistry, the fission barrier is the activation energy required for a nucleus of an atom to undergo fission. This barrier may also be defined as the minimum amount of energy required to deform the nucleus to the ...

must also be overcome. Fissionable nuclides primarily split in interactions with fast neutrons

The neutron detection temperature, also called the neutron energy, indicates a free neutron's kinetic energy, usually given in electron volts. The term ''temperature'' is used, since hot, thermal and cold neutrons are moderated in a medium with ...

, while fissile

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material that can undergo nuclear fission when struck by a neutron of low energy. A self-sustaining thermal Nuclear chain reaction#Fission chain reaction, chain reaction can only be achieved with fissil ...

nuclides easily split in interactions with "slow" i.e. thermal neutrons

The neutron detection temperature, also called the neutron energy, indicates a free neutron's kinetic energy, usually given in electron volts. The term ''temperature'' is used, since hot, thermal and cold neutrons are moderated in a medium with ...

, usually originating from moderation

Moderation is the process or trait of eliminating, lessening, or avoiding extremes. It is used to ensure normality throughout the medium on which it is being conducted. Common uses of moderation include:

* A way of life emphasizing perfect amo ...

of fast neutrons.

Fission is a form of nuclear transmutation

Nuclear transmutation is the conversion of one chemical element or an isotope into another chemical element. Nuclear transmutation occurs in any process where the number of protons or neutrons in the nucleus of an atom is changed.

A transmutat ...

because the resulting fragments (or daughter atoms) are not the same element

Element or elements may refer to:

Science

* Chemical element, a pure substance of one type of atom

* Heating element, a device that generates heat by electrical resistance

* Orbital elements, parameters required to identify a specific orbit of o ...

as the original parent atom. The two (or more) nuclei produced are most often of comparable but slightly different sizes, typically with a mass ratio of products of about 3 to 2, for common fissile isotope

Isotopes are distinct nuclear species (or ''nuclides'') of the same chemical element. They have the same atomic number (number of protons in their Atomic nucleus, nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemica ...

s. Most fissions are binary fissions (producing two charged fragments), but occasionally (2 to 4 times per 1000 events), ''three'' positively charged fragments are produced, in a ternary fission

Ternary fission is a comparatively rare (0.2 to 0.4% of events) type of nuclear fission in which three charged products are produced rather than two. As in other nuclear fission processes, other uncharged particles such as multiple neutrons and ...

. The smallest of these fragments in ternary processes ranges in size from a proton to an argon

Argon is a chemical element; it has symbol Ar and atomic number 18. It is in group 18 of the periodic table and is a noble gas. Argon is the third most abundant gas in Earth's atmosphere, at 0.934% (9340 ppmv). It is more than twice as abu ...

nucleus.

Apart from fission induced by an exogenous neutron, harnessed and exploited by humans, a natural form of spontaneous radioactive decay (not requiring an exogenous neutron, because the nucleus already has an overabundance of neutrons) is also referred to as fission, and occurs especially in very high-mass-number isotopes. Spontaneous fission

Spontaneous fission (SF) is a form of radioactive decay in which a heavy atomic nucleus splits into two or more lighter nuclei. In contrast to induced fission, there is no inciting particle to trigger the decay; it is a purely probabilistic proc ...

was discovered in 1940 by Flyorov, Petrzhak, and Kurchatov in Moscow. In contrast to nuclear fusion

Nuclear fusion is a nuclear reaction, reaction in which two or more atomic nuclei combine to form a larger nuclei, nuclei/neutrons, neutron by-products. The difference in mass between the reactants and products is manifested as either the rele ...

, which drives the formation of stars and their development, one can consider nuclear fission as negligible for the evolution of the universe. Nonetheless, natural nuclear fission reactors may form under very rare conditions. Accordingly, all elements (with a few exceptions, see "spontaneous fission") which are important for the formation of solar systems, planets and also for all forms of life are not fission products, but rather the results of fusion processes.

The unpredictable composition of the products (which vary in a broad probabilistic and somewhat chaotic manner) distinguishes fission from purely quantum tunneling

In physics, a quantum (: quanta) is the minimum amount of any physical entity (physical property) involved in an interaction. The fundamental notion that a property can be "quantized" is referred to as "the hypothesis of quantization". This me ...

processes such as proton emission

Proton emission (also known as proton radioactivity) is a rare type of radioactive decay in which a proton is ejected from a atomic nucleus, nucleus. Proton emission can occur from high-lying excited states in a nucleus following a beta decay ...

, alpha decay

Alpha decay or α-decay is a type of radioactive decay in which an atomic nucleus emits an alpha particle (helium nucleus). The parent nucleus transforms or "decays" into a daughter product, with a mass number that is reduced by four and an a ...

, and cluster decay

Cluster decay, also named heavy particle radioactivity, heavy ion radioactivity or heavy cluster decay," is a rare type of nuclear decay in which an atomic nucleus emits a small "cluster" of neutrons and protons, more than in an alpha particle, ...

, which give the same products each time. Nuclear fission produces energy for nuclear power

Nuclear power is the use of nuclear reactions to produce electricity. Nuclear power can be obtained from nuclear fission, nuclear decay and nuclear fusion reactions. Presently, the vast majority of electricity from nuclear power is produced by ...

and drives the explosion of nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear exp ...

s. Both uses are possible because certain substances called nuclear fuel

Nuclear fuel refers to any substance, typically fissile material, which is used by nuclear power stations or other atomic nucleus, nuclear devices to generate energy.

Oxide fuel

For fission reactors, the fuel (typically based on uranium) is ...

s undergo fission when struck by fission neutrons, and in turn emit neutrons when they break apart. This makes a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction

In nuclear physics, a nuclear chain reaction occurs when one single nuclear reaction causes an average of one or more subsequent nuclear reactions, thus leading to the possibility of a self-propagating series or "positive feedback loop" of thes ...

possible, releasing energy at a controlled rate in a nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a Nuclear fission, fission nuclear chain reaction. They are used for Nuclear power, commercial electricity, nuclear marine propulsion, marine propulsion, Weapons-grade plutonium, weapons ...

or at a very rapid, uncontrolled rate in a nuclear weapon.

The amount of free energy released in the fission of an equivalent amount of is a million times more than that released in the combustion of methane

Methane ( , ) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The abundance of methane on Earth makes ...

or from hydrogen fuel cells

A fuel cell is an electrochemical cell that converts the chemical energy of a fuel (often hydrogen) and an oxidizing agent (often oxygen) into electricity through a pair of redox reactions. Fuel cells are different from most batteries in requ ...

.

The products of nuclear fission, however, are on average far more radioactive

Radioactive decay (also known as nuclear decay, radioactivity, radioactive disintegration, or nuclear disintegration) is the process by which an unstable atomic nucleus loses energy by radiation. A material containing unstable nuclei is conside ...

than the heavy elements which are normally fissioned as fuel, and remain so for significant amounts of time, giving rise to a nuclear waste

Radioactive waste is a type of hazardous waste that contains radioactive material. It is a result of many activities, including nuclear medicine, nuclear research, nuclear power generation, nuclear decommissioning, rare-earth mining, and nuclear ...

problem. However, the seven long-lived fission product

Long-lived fission products (LLFPs) are radioactive materials with a long half-life (more than 200,000 years) produced by nuclear fission of uranium and plutonium. Because of their persistent radiotoxicity, it is necessary to isolate them from hum ...

s make up only a small fraction of fission products. Neutron absorption

Neutron capture is a nuclear reaction in which an atomic nucleus and one or more neutrons collide and merge to form a heavier nucleus. Since neutrons have no electric charge, they can enter a nucleus more easily than positively charged protons, wh ...

which does not lead to fission produces plutonium

Plutonium is a chemical element; it has symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is a silvery-gray actinide metal that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibits six allotropes and four ...

(from ) and minor actinide

Minor may refer to:

Common meanings

* Minor (law), a person not under the age of certain legal activities.

* Academic minor, a secondary field of study in undergraduate education

Mathematics

* Minor (graph theory), a relation of one graph to ...

s (from both and ) whose radiotoxicity is far higher than that of the long lived fission products. Concerns over nuclear waste accumulation and the destructive potential of nuclear weapons are a counterbalance to the peaceful desire to use fission as an energy source. The thorium fuel cycle

The thorium fuel cycle is a nuclear fuel cycle that uses an isotope of thorium, , as the fertile material. In the reactor, is transmuted into the fissile artificial uranium isotope which is the nuclear fuel. Unlike natural uranium, natural ...

produces virtually no plutonium and much less minor actinides, but - or rather its decay products - are a major gamma ray emitter. All actinides are fertile

Fertility in colloquial terms refers the ability to have offspring. In demographic contexts, fertility refers to the actual production of offspring, rather than the physical capability to reproduce, which is termed fecundity. The fertility rate is ...

or fissile

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material that can undergo nuclear fission when struck by a neutron of low energy. A self-sustaining thermal Nuclear chain reaction#Fission chain reaction, chain reaction can only be achieved with fissil ...

and fast breeder reactor

A breeder reactor is a nuclear reactor that generates more fissile material than it consumes. These reactors can be Nuclear fuel, fueled with more-commonly available isotopes of uranium and Isotopes of thorium, thorium, such as uranium-238 and t ...

s can fission them all albeit only in certain configurations. Nuclear reprocessing

Nuclear reprocessing is the chemical separation of fission products and actinides from spent nuclear fuel. Originally, reprocessing was used solely to extract plutonium for producing nuclear weapons. With commercialization of nuclear power, the ...

aims to recover usable material from spent nuclear fuel

Spent nuclear fuel, occasionally called used nuclear fuel, is nuclear fuel that has been irradiated in a nuclear reactor (usually at a nuclear power plant). It is no longer useful in sustaining a nuclear reaction in an ordinary thermal reactor and ...

to both enable uranium (and thorium) supplies to last longer and to reduce the amount of "waste". The industry term for a process that fissions all or nearly all actinides is a " closed fuel cycle".

Physical overview

Mechanism

Younes and Loveland define fission as, "...a collective motion of the protons and neutrons that make up the nucleus, and as such it is distinguishable from other phenomena that break up the nucleus. Nuclear fission is an extreme example of large-amplitude

The amplitude of a periodic variable is a measure of its change in a single period (such as time or spatial period). The amplitude of a non-periodic signal is its magnitude compared with a reference value. There are various definitions of am ...

collective motion that results in the division of a parent nucleus into two or more fragment nuclei. The fission process can occur spontaneously, or it can be induced by an incident particle." The energy from a fission reaction is produced by its fission products

Nuclear fission products are the atomic fragments left after a large atomic nucleus undergoes nuclear fission. Typically, a large nucleus like that of uranium fissions by splitting into two smaller nuclei, along with a few neutrons, the releas ...

, though a large majority of it, about 85 percent, is found in fragment kinetic energy

In physics, the kinetic energy of an object is the form of energy that it possesses due to its motion.

In classical mechanics, the kinetic energy of a non-rotating object of mass ''m'' traveling at a speed ''v'' is \fracmv^2.Resnick, Rober ...

, while about 6 percent each comes from initial neutrons and gamma rays and those emitted after beta decay

In nuclear physics, beta decay (β-decay) is a type of radioactive decay in which an atomic nucleus emits a beta particle (fast energetic electron or positron), transforming into an isobar of that nuclide. For example, beta decay of a neutron ...

, plus about 3 percent from neutrino

A neutrino ( ; denoted by the Greek letter ) is an elementary particle that interacts via the weak interaction and gravity. The neutrino is so named because it is electrically neutral and because its rest mass is so small ('' -ino'') that i ...

s as the product of such decay.

Radioactive decay

Nuclear fission can occur without neutron bombardment as a type of radioactive decay. This type of fission is calledspontaneous fission

Spontaneous fission (SF) is a form of radioactive decay in which a heavy atomic nucleus splits into two or more lighter nuclei. In contrast to induced fission, there is no inciting particle to trigger the decay; it is a purely probabilistic proc ...

, and was first observed in 1940.

Nuclear reaction

During induced fission, a compound system is formed after an incident particle fuses with a target. The resultant excitation energy may be sufficient to emit neutrons, or gamma-rays, and nuclear scission. Fission into two fragments is called binary fission, and is the most commonnuclear reaction

In nuclear physics and nuclear chemistry, a nuclear reaction is a process in which two atomic nucleus, nuclei, or a nucleus and an external subatomic particle, collide to produce one or more new nuclides. Thus, a nuclear reaction must cause a t ...

. Occurring least frequently is ternary fission

Ternary fission is a comparatively rare (0.2 to 0.4% of events) type of nuclear fission in which three charged products are produced rather than two. As in other nuclear fission processes, other uncharged particles such as multiple neutrons and ...

, in which a third particle is emitted. This third particle is commonly an α particle

Alpha particles, also called alpha rays or alpha radiation, consist of two protons and two neutrons bound together into a particle identical to a helium-4 nucleus. They are generally produced in the process of alpha decay but may also be produced ...

. Since in nuclear fission, the nucleus emits more neutrons than the one it absorbs, a chain reaction

A chain reaction is a sequence of reactions where a reactive product or by-product causes additional reactions to take place. In a chain reaction, positive feedback leads to a self-amplifying chain of events.

Chain reactions are one way that sys ...

is possible.

Binary fission may produce any of the fission products, at 95±15 and 135±15 daltons. One example of a binary fission event in the most commonly used fissile nuclide

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material that can undergo nuclear fission when struck by a neutron of low energy. A self-sustaining thermal chain reaction can only be achieved with fissile material. The predominant neutron energy in a ...

, , is given as:

However, the binary process happens merely because it is the most probable. In anywhere from two to four fissions per 1000 in a nuclear reactor, ternary fission can produce three positively charged fragments (plus neutrons) and the smallest of these may range from so small a charge and mass as a proton ( ''Z'' = 1), to as large a fragment as argon

Argon is a chemical element; it has symbol Ar and atomic number 18. It is in group 18 of the periodic table and is a noble gas. Argon is the third most abundant gas in Earth's atmosphere, at 0.934% (9340 ppmv). It is more than twice as abu ...

(''Z'' = 18). The most common small fragments, however, are composed of 90% helium-4 nuclei with more energy than alpha particles from alpha decay (so-called "long range alphas" at ~16 megaelectronvolt

In physics, an electronvolt (symbol eV), also written electron-volt and electron volt, is the measure of an amount of kinetic energy gained by a single electron accelerating through an electric potential difference of one volt in vacuum. When ...

s (MeV)), plus helium-6 nuclei, and tritons (the nuclei of tritium

Tritium () or hydrogen-3 (symbol T or H) is a rare and radioactive isotope of hydrogen with a half-life of ~12.33 years. The tritium nucleus (t, sometimes called a ''triton'') contains one proton and two neutrons, whereas the nucleus of the ...

). Though less common than binary fission, it still produces significant helium-4 and tritium gas buildup in the fuel rods of modern nuclear reactors.

Bohr and Wheeler used their liquid drop model

In nuclear physics, the semi-empirical mass formula (SEMF; sometimes also called the Weizsäcker formula, Bethe–Weizsäcker formula, or Bethe–Weizsäcker mass formula to distinguish it from the Bethe–Weizsäcker process) is used to approxima ...

, the packing fraction curve of Arthur Jeffrey Dempster

Arthur Jeffrey Dempster (August 14, 1886 – March 11, 1950) was a Canadian-American physicist best known for his work in mass spectrometry and his discovery in 1935 of the uranium isotope 235U.

Early life and education

Dempster was born in ...

, and Eugene Feenberg's estimates of nucleus radius and surface tension, to estimate the mass differences of parent and daughters in fission. They then equated this mass difference to energy using Einstein's mass-energy equivalence formula. The stimulation of the nucleus after neutron bombardment was analogous to the vibrations of a liquid drop, with surface tension

Surface tension is the tendency of liquid surfaces at rest to shrink into the minimum surface area possible. Surface tension (physics), tension is what allows objects with a higher density than water such as razor blades and insects (e.g. Ge ...

and the Coulomb force

Coulomb's inverse-square law, or simply Coulomb's law, is an experimental law of physics that calculates the amount of force between two electrically charged particles at rest. This electric force is conventionally called the ''electrostatic ...

in opposition. Plotting the sum of these two energies as a function of elongated shape, they determined the resultant energy surface had a saddle shape. The saddle provided an energy barrier called the critical energy barrier. Energy of about 6 MeV provided by the incident neutron was necessary to overcome this barrier and cause the nucleus to fission. According to John Lilley, "The energy required to overcome the barrier to fission is called the ''activation energy'' or ''fission barrier'' and is about 6 MeV for ''A'' ≈ 240. It is found that the activation energy decreases as A increases. Eventually, a point is reached where activation energy disappears altogether...it would undergo very rapid spontaneous fission."

Maria Goeppert Mayer

Maria Goeppert Mayer (; ; June 28, 1906 – February 20, 1972) was a German-American theoretical physicist who shared the 1963 Nobel Prize in Physics with J. Hans D. Jensen and Eugene Wigner. One half of the prize was awarded jointly to Goeppe ...

later proposed the nuclear shell model

In nuclear physics, atomic physics, and nuclear chemistry, the nuclear shell model utilizes the Pauli exclusion principle to model the structure of atomic nuclei in terms of energy levels. The first shell model was proposed by Dmitri Ivanenk ...

for the nucleus. The nuclides that can sustain a fission chain reaction are suitable for use as nuclear fuel

Nuclear fuel refers to any substance, typically fissile material, which is used by nuclear power stations or other atomic nucleus, nuclear devices to generate energy.

Oxide fuel

For fission reactors, the fuel (typically based on uranium) is ...

s. The most common nuclear fuels are 235U (the isotope of uranium with mass number

The mass number (symbol ''A'', from the German word: ''Atomgewicht'', "atomic weight"), also called atomic mass number or nucleon number, is the total number of protons and neutrons (together known as nucleons) in an atomic nucleus. It is appro ...

235 and of use in nuclear reactors) and 239Pu (the isotope of plutonium with mass number 239). These fuels break apart into a bimodal range of chemical elements with atomic masses centering near 95 and 135 daltons (fission products

Nuclear fission products are the atomic fragments left after a large atomic nucleus undergoes nuclear fission. Typically, a large nucleus like that of uranium fissions by splitting into two smaller nuclei, along with a few neutrons, the releas ...

). Most nuclear fuels undergo spontaneous fission only very slowly, decaying instead mainly via an alpha

Alpha (uppercase , lowercase ) is the first letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals, it has a value of one. Alpha is derived from the Phoenician letter ''aleph'' , whose name comes from the West Semitic word for ' ...

-beta

Beta (, ; uppercase , lowercase , or cursive ; or ) is the second letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals, it has a value of 2. In Ancient Greek, beta represented the voiced bilabial plosive . In Modern Greek, it represe ...

decay chain

In nuclear science a decay chain refers to the predictable series of radioactive disintegrations undergone by the nuclei of certain unstable chemical elements.

Radioactive isotopes do not usually decay directly to stable isotopes, but rather ...

over periods of millennia

A millennium () is a period of one thousand years, one hundred decades, or ten centuries, sometimes called a kiloannum (ka), or kiloyear (ky). Normally, the word is used specifically for periods of a thousand years that begin at the starting p ...

to eons. In a nuclear reactor or nuclear weapon, the overwhelming majority of fission events are induced by bombardment with another particle, a neutron, which is itself produced by prior fission events.

Fissionable

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material that can undergo nuclear fission when struck by a neutron of low energy. A self-sustaining thermal chain reaction can only be achieved with fissile material. The predominant neutron energy in ...

isotopes such as uranium-238 require additional energy provided by fast neutron

The neutron detection temperature, also called the neutron energy, indicates a free neutron's kinetic energy, usually given in electron volts. The term ''temperature'' is used, since hot, thermal and cold neutrons are moderated in a medium with ...

s (such as those produced by nuclear fusion in thermonuclear weapons

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H-bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

). While ''some'' of the neutrons released from the fission of are fast enough to induce another fission in , ''most'' are not, meaning it can never achieve criticality. While there is a very small (albeit nonzero) chance of a thermal neutron inducing fission in , neutron absorption

Neutron capture is a nuclear reaction in which an atomic nucleus and one or more neutrons collide and merge to form a heavier nucleus. Since neutrons have no electric charge, they can enter a nucleus more easily than positively charged protons, wh ...

is orders of magnitude more likely.

Energetics

Input

Fission cross sections are a measurable property related to the probability that fission will occur in a nuclear reaction. Cross sections are a function of incident neutron energy, and those for and are a million times higher than at lower neutron energy levels. Absorption of any neutron makes available to the nucleus binding energy of about 5.3 MeV. needs a fast neutron to supply the additional 1 MeV needed to cross the critical energy barrier for fission. In the case of however, that extra energy is provided when adjusts from an odd to an even mass. In the words of Younes and Lovelace, "...the neutron absorption on a target forms a nucleus with excitation energy greater than the critical fission energy, whereas in the case of ''n'' + , the resulting nucleus has an excitation energy below the critical fission energy."

About 6 MeV of the fission-input energy is supplied by the simple binding of an extra neutron to the heavy nucleus via the strong force; however, in many fissionable isotopes, this amount of energy is not enough for fission. Uranium-238, for example, has a near-zero fission cross section for neutrons of less than 1 MeV energy. If no additional energy is supplied by any other mechanism, the nucleus will not fission, but will merely absorb the neutron, as happens when absorbs slow and even some fraction of fast neutrons, to become . The remaining energy to initiate fission can be supplied by two other mechanisms: one of these is more kinetic energy of the incoming neutron, which is increasingly able to fission a

Fission cross sections are a measurable property related to the probability that fission will occur in a nuclear reaction. Cross sections are a function of incident neutron energy, and those for and are a million times higher than at lower neutron energy levels. Absorption of any neutron makes available to the nucleus binding energy of about 5.3 MeV. needs a fast neutron to supply the additional 1 MeV needed to cross the critical energy barrier for fission. In the case of however, that extra energy is provided when adjusts from an odd to an even mass. In the words of Younes and Lovelace, "...the neutron absorption on a target forms a nucleus with excitation energy greater than the critical fission energy, whereas in the case of ''n'' + , the resulting nucleus has an excitation energy below the critical fission energy."

About 6 MeV of the fission-input energy is supplied by the simple binding of an extra neutron to the heavy nucleus via the strong force; however, in many fissionable isotopes, this amount of energy is not enough for fission. Uranium-238, for example, has a near-zero fission cross section for neutrons of less than 1 MeV energy. If no additional energy is supplied by any other mechanism, the nucleus will not fission, but will merely absorb the neutron, as happens when absorbs slow and even some fraction of fast neutrons, to become . The remaining energy to initiate fission can be supplied by two other mechanisms: one of these is more kinetic energy of the incoming neutron, which is increasingly able to fission a fissionable

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material that can undergo nuclear fission when struck by a neutron of low energy. A self-sustaining thermal chain reaction can only be achieved with fissile material. The predominant neutron energy in ...

heavy nucleus as it exceeds a kinetic energy of 1 MeV or more (so-called fast neutrons). Such high energy neutrons are able to fission directly (see thermonuclear weapon

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H-bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

for application, where the fast neutrons are supplied by nuclear fusion). However, this process cannot happen to a great extent in a nuclear reactor, as too small a fraction of the fission neutrons produced by any type of fission have enough energy to efficiently fission . (For example, neutrons from thermal fission of have a mean

A mean is a quantity representing the "center" of a collection of numbers and is intermediate to the extreme values of the set of numbers. There are several kinds of means (or "measures of central tendency") in mathematics, especially in statist ...

energy of 2 MeV, a median

The median of a set of numbers is the value separating the higher half from the lower half of a Sample (statistics), data sample, a statistical population, population, or a probability distribution. For a data set, it may be thought of as the “ ...

energy of 1.6 MeV, and a mode

Mode ( meaning "manner, tune, measure, due measure, rhythm, melody") may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* MO''D''E (magazine), a defunct U.S. women's fashion magazine

* ''Mode'' magazine, a fictional fashion magazine which is the setting fo ...

of 0.75 MeV, and the energy spectrum for fast fission is similar.)

Among the heavy actinide

The actinide () or actinoid () series encompasses at least the 14 metallic chemical elements in the 5f series, with atomic numbers from 89 to 102, actinium through nobelium. Number 103, lawrencium, is also generally included despite being part ...

elements, however, those isotopes that have an odd number of neutrons (such as 235U with 143 neutrons) bind an extra neutron with an additional 1 to 2 MeV of energy over an isotope of the same element with an even number of neutrons (such as 238U with 146 neutrons). This extra binding energy is made available as a result of the mechanism of neutron pairing effects, which itself is caused by the Pauli exclusion principle

In quantum mechanics, the Pauli exclusion principle (German: Pauli-Ausschlussprinzip) states that two or more identical particles with half-integer spins (i.e. fermions) cannot simultaneously occupy the same quantum state within a system that o ...

, allowing an extra neutron to occupy the same nuclear orbital as the last neutron in the nucleus. In such isotopes, therefore, no neutron kinetic energy is needed, for all the necessary energy is supplied by absorption of any neutron, either of the slow or fast variety (the former are used in moderated nuclear reactors, and the latter are used in fast-neutron reactor

A fast-neutron reactor (FNR) or fast-spectrum reactor or simply a fast reactor is a category of nuclear reactor in which the fission chain reaction is sustained by fast neutrons (carrying energies above 1 MeV, on average), as opposed to slow t ...

s, and in weapons).

According to Younes and Loveland, "Actinides like that fission easily following the absorption of a thermal (0.25 meV) neutron are called ''fissile'', whereas those like that do not easily fission when they absorb a thermal neutron are called ''fissionable''."

Output

After an incident particle has fused with a parent nucleus, if the excitation energy is sufficient, the nucleus breaks into fragments. This is called scission, and occurs at about 10−20 seconds. The fragments can emit prompt neutrons at between 10−18 and 10−15 seconds. At about 10−11 seconds, the fragments can emit gamma rays. At 10−3 seconds β decay, β-delayed neutron

In nuclear engineering, a delayed neutron is a neutron released not immediately during a nuclear fission event, but shortly afterward—ranging from milliseconds to several minutes later. These neutrons are emitted by excited daughter nuclei of ce ...

s, and gamma rays are emitted from the decay product

In nuclear physics, a decay product (also known as a daughter product, daughter isotope, radio-daughter, or daughter nuclide) is the remaining nuclide left over from radioactive decay. Radioactive decay often proceeds via a sequence of steps ( d ...

s.

Typical fission events release about two hundred million eV (200 MeV) of energy for each fission event. The exact isotope which is fissioned, and whether or not it is fissionable or fissile, has only a small impact on the amount of energy released. This can be easily seen by examining the curve of binding energy

In physics and chemistry, binding energy is the smallest amount of energy required to remove a particle from a system of particles or to disassemble a system of particles into individual parts. In the former meaning the term is predominantly use ...

(image below), and noting that the average binding energy of the actinide nuclides beginning with uranium is around 7.6 MeV per nucleon. Looking further left on the curve of binding energy, where the fission products cluster, it is easily observed that the binding energy of the fission products tends to center around 8.5 MeV per nucleon. Thus, in any fission event of an isotope in the actinide mass range, roughly 0.9 MeV are released per nucleon of the starting element. The fission of 235U by a slow neutron yields nearly identical energy to the fission of 238U by a fast neutron. This energy release profile holds for thorium and the various minor actinides as well.

When a

When a uranium

Uranium is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Ura ...

nucleus fissions into two daughter nuclei fragments, about 0.1 percent of the mass of the uranium nucleusHans A. Bethe (April 1950)"The Hydrogen Bomb"

''Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists'', p. 99. appears as the fission energy of ~200 MeV. For uranium-235 (total mean fission energy 202.79 MeV), typically ~169 MeV appears as the kinetic energy of the daughter nuclei, which fly apart at about 3% of the speed of light, due to

Coulomb repulsion

Coulomb's inverse-square law, or simply Coulomb's law, is an experimental law of physics that calculates the amount of force between two electrically charged particles at rest. This electric force is conventionally called the ''electrostatic f ...

. Also, an average of 2.5 neutrons are emitted, with a mean

A mean is a quantity representing the "center" of a collection of numbers and is intermediate to the extreme values of the set of numbers. There are several kinds of means (or "measures of central tendency") in mathematics, especially in statist ...

kinetic energy per neutron of ~2 MeV (total of 4.8 MeV). The fission reaction also releases ~7 MeV in prompt gamma ray photon

A photon () is an elementary particle that is a quantum of the electromagnetic field, including electromagnetic radiation such as light and radio waves, and the force carrier for the electromagnetic force. Photons are massless particles that can ...

s. The latter figure means that a nuclear fission explosion or criticality accident emits about 3.5% of its energy as gamma rays, less than 2.5% of its energy as fast neutrons (total of both types of radiation ~6%), and the rest as kinetic energy of fission fragments (this appears almost immediately when the fragments impact surrounding matter, as simple heat).

Some processes involving neutrons are notable for absorbing or finally yielding energy — for example neutron kinetic energy does not yield heat immediately if the neutron is captured by a uranium-238 atom to breed plutonium-239, but this energy is emitted if the plutonium-239 is later fissioned. On the other hand, so-called delayed neutrons emitted as radioactive decay products with half-lives up to several minutes, from fission-daughters, are very important to reactor control, because they give a characteristic "reaction" time for the total nuclear reaction to double in size, if the reaction is run in a " delayed-critical" zone which deliberately relies on these neutrons for a supercritical chain-reaction (one in which each fission cycle yields more neutrons than it absorbs). Without their existence, the nuclear chain-reaction would be prompt critical

In nuclear engineering, prompt criticality is the criticality (the state in which a nuclear chain reaction is self-sustaining) that is achieved with prompt neutrons alone (without the efforts of delayed neutrons). As a result, prompt supercritic ...

and increase in size faster than it could be controlled by human intervention. In this case, the first experimental atomic reactors would have run away to a dangerous and messy "prompt critical reaction" before their operators could have manually shut them down (for this reason, designer Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian and naturalized American physicist, renowned for being the creator of the world's first artificial nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1, and a member of the Manhattan Project ...

included radiation-counter-triggered control rods, suspended by electromagnets, which could automatically drop into the center of Chicago Pile-1

Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1) was the first artificial nuclear reactor. On 2 December 1942, the first human-made self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was initiated in CP-1 during an experiment led by Enrico Fermi. The secret development of the react ...

). If these delayed neutrons are captured without producing fissions, they produce heat as well.

Binding energy

mass number

The mass number (symbol ''A'', from the German word: ''Atomgewicht'', "atomic weight"), also called atomic mass number or nucleon number, is the total number of protons and neutrons (together known as nucleons) in an atomic nucleus. It is appro ...

, is atomic number

The atomic number or nuclear charge number (symbol ''Z'') of a chemical element is the charge number of its atomic nucleus. For ordinary nuclei composed of protons and neutrons, this is equal to the proton number (''n''p) or the number of pro ...

, is the atomic mass of a hydrogen atom, is the mass of a neutron, and is the speed of light

The speed of light in vacuum, commonly denoted , is a universal physical constant exactly equal to ). It is exact because, by international agreement, a metre is defined as the length of the path travelled by light in vacuum during a time i ...

. Thus, the mass of an atom is less than the mass of its constituent protons and neutrons, assuming the average binding energy of its electrons is negligible. The binding energy is expressed in energy units, using Einstein's mass-energy equivalence relationship. The binding energy also provides an estimate of the total energy released from fission.

The curve of binding energy is characterized by a broad maximum near mass number 60 at 8.6 MeV, then gradually decreases to 7.6 MeV at the highest mass numbers. Mass numbers higher than 238 are rare. At the lighter end of the scale, peaks are noted for helium-4, and the multiples such as beryllium-8, carbon-12, oxygen-16, neon-20 and magnesium-24. Binding energy due to the nuclear force approaches a constant value for large , while the Coulomb acts over a larger distance so that electrical potential energy per proton grows as increases. Fission energy is released when a is larger than approx. 60. Fusion energy is released when lighter nuclei combine.

Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker's semi-empirical mass formula

In nuclear physics, the semi-empirical mass formula (SEMF; sometimes also called the Weizsäcker formula, Bethe–Weizsäcker formula, or Bethe–Weizsäcker mass formula to distinguish it from the Bethe–Weizsäcker process) is used to approxim ...

may be used to express the binding energy as the sum of five terms, which are the volume energy, a surface correction, Coulomb energy, a symmetry term, and a pairing term:

where the nuclear binding energy is proportional to the nuclear volume, while nucleons near the surface interact with fewer nucleons, reducing the effect of the volume term. According to Lilley, "For all naturally occurring nuclei, the surface-energy term dominates and the nucleus exists in a state of equilibrium." The negative contribution of Coulomb energy arises from the repulsive electric force of the protons. The symmetry term arises from the fact that effective forces in the nucleus are stronger for unlike neutron-proton pairs, rather than like neutron–neutron or proton–proton pairs. The pairing term arises from the fact that like nucleons form spin-zero pairs in the same spatial state. The pairing is positive if and are both even, adding to the binding energy.

In fission there is a preference for fission fragment

Nuclear fission products are the atomic fragments left after a large atomic nucleus undergoes nuclear fission. Typically, a large nucleus like that of uranium fissions by splitting into two smaller nuclei, along with a few neutrons, the release ...

s with even , which is called the odd–even effect on the fragments' charge distribution. This can be seen in the empirical fragment yield data for each fission product, as products with even have higher yield values. However, no odd–even effect is observed on fragment distribution based on their . This result is attributed to nucleon pair breaking.

In nuclear fission events the nuclei may break into any combination of lighter nuclei, but the most common event is not fission to equal mass nuclei of about mass 120; the most common event (depending on isotope and process) is a slightly unequal fission in which one daughter nucleus has a mass of about 90 to 100 daltons and the other the remaining 130 to 140 daltons.

Stable nuclei, and unstable nuclei with very long half-lives Half-life is a mathematical and scientific description of exponential or gradual decay.

Half-life, half life or halflife may also refer to:

Film

* ''Half-Life'' (film), a 2008 independent film by Jennifer Phang

* '' Half Life: A Parable for t ...

, follow a trend of stability evident when is plotted against . For lighter nuclei less than = 20, the line has the slope = , while the heavier nuclei require additional neutrons to remain stable. Nuclei that are neutron- or proton-rich have excessive binding energy for stability, and the excess energy may convert a neutron to a proton or a proton to a neutron via the weak nuclear force, a process known as beta decay

In nuclear physics, beta decay (β-decay) is a type of radioactive decay in which an atomic nucleus emits a beta particle (fast energetic electron or positron), transforming into an isobar of that nuclide. For example, beta decay of a neutron ...

.

Neutron-induced fission of U-235 emits a total energy of 207 MeV, of which about 200 MeV is recoverable, Prompt fission fragments amount to 168 MeV, which are easily stopped with a fraction of a millimeter. Prompt neutrons total 5 MeV, and this energy is recovered as heat via scattering in the reactor. However, many fission fragments are neutron-rich and decay via β− emissions. According to Lilley, "The radioactive decay energy from the fission chains is the second release of energy due to fission. It is much less than the prompt energy, but it is a significant amount and is why reactors must continue to be cooled after they have been shut down and why the waste products must be handled with great care and stored safely."

Chain reactions

heavy water

Heavy water (deuterium oxide, , ) is a form of water (molecule), water in which hydrogen atoms are all deuterium ( or D, also known as ''heavy hydrogen'') rather than the common hydrogen-1 isotope (, also called ''protium'') that makes up most o ...

, and graphite

Graphite () is a Crystallinity, crystalline allotrope (form) of the element carbon. It consists of many stacked Layered materials, layers of graphene, typically in excess of hundreds of layers. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable ...

.

According to John C. Lee, "For all nuclear reactors in operation and those under development, the nuclear fuel cycle

The nuclear fuel cycle, also known as the nuclear fuel chain, describes the series of stages that nuclear fuel undergoes during its production, use, and recycling or disposal. It consists of steps in the ''front end'', which are the preparation o ...

is based on one of three ''fissile'' materials, 235U, 233U, and 239Pu, and the associated isotopic chains. For the current generation of LWRs, the enriched U contains 2.5~4.5 wt%

In chemistry, the mass fraction of a substance within a mixture is the ratio w_i (alternatively denoted Y_i) of the mass m_i of that substance to the total mass m_\text of the mixture. Expressed as a formula, the mass fraction is:

: w_i = \frac ...

of 235U, which is fabricated into UO2 fuel rod

Nuclear fuel refers to any substance, typically fissile material, which is used by nuclear power stations or other nuclear devices to generate energy.

Oxide fuel

For fission reactors, the fuel (typically based on uranium) is usually based o ...

s and loaded into fuel assemblies."

Lee states, "One important comparison for the three major fissile nuclides, 235U, 233U, and 239Pu, is their breeding potential. A ''breeder'' is by definition a reactor that produces more fissile material than it consumes and needs a minimum of two neutrons produced for each neutron absorbed in a fissile nucleus. Thus, in general, the ''conversion ratio (CR) is defined as the ratio of fissile material produced to that destroyed''...when the CR is greater than 1.0, it is called the ''breeding ratio'' (BR)...233U offers a superior breeding potential for both thermal and fast reactors, while 239Pu offers a superior breeding potential for fast reactors."

Fission reactors

Critical fission reactors are the most common type of nuclear reactor. In a critical fission reactor, neutrons produced by fission of fuel atoms are used to induce yet more fissions, to sustain a controllable amount of energy release. Devices that produce engineered but non-self-sustaining fission reactions are subcritical fission reactors. Such devices use radioactive decay or

Critical fission reactors are the most common type of nuclear reactor. In a critical fission reactor, neutrons produced by fission of fuel atoms are used to induce yet more fissions, to sustain a controllable amount of energy release. Devices that produce engineered but non-self-sustaining fission reactions are subcritical fission reactors. Such devices use radioactive decay or particle accelerator

A particle accelerator is a machine that uses electromagnetic fields to propel electric charge, charged particles to very high speeds and energies to contain them in well-defined particle beam, beams. Small accelerators are used for fundamental ...

s to trigger fissions.

Critical fission reactors are built for three primary purposes, which typically involve different engineering trade-offs to take advantage of either the heat or the neutrons produced by the fission chain reaction:

*'' power reactors'' are intended to produce heat for nuclear power, either as part of a generating station

A power station, also referred to as a power plant and sometimes generating station or generating plant, is an industrial facility for the electricity generation, generation of electric power. Power stations are generally connected to an electr ...

or a local power system such as a nuclear submarine

A nuclear submarine is a submarine powered by a nuclear reactor, but not necessarily nuclear-armed.

Nuclear submarines have considerable performance advantages over "conventional" (typically diesel-electric) submarines. Nuclear propulsion ...

.

*''research reactor

Research reactors are nuclear fission-based nuclear reactors that serve primarily as a neutron source. They are also called non-power reactors, in contrast to power reactors that are used for electricity production, heat generation, or maritim ...

s'' are intended to produce neutrons and/or activate radioactive sources for scientific, medical, engineering, or other research purposes.

*''breeder reactor

A breeder reactor is a nuclear reactor that generates more fissile material than it consumes. These reactors can be fueled with more-commonly available isotopes of uranium and thorium, such as uranium-238 and thorium-232, as opposed to the ...

s'' are intended to produce nuclear fuels in bulk from more abundant isotopes

Isotopes are distinct nuclear species (or ''nuclides'') of the same chemical element. They have the same atomic number (number of protons in their nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemical element), but ...

. The better known fast breeder reactor

A breeder reactor is a nuclear reactor that generates more fissile material than it consumes. These reactors can be Nuclear fuel, fueled with more-commonly available isotopes of uranium and Isotopes of thorium, thorium, such as uranium-238 and t ...

makes 239Pu (a nuclear fuel) from the naturally very abundant 238U (not a nuclear fuel). Thermal breeder reactors previously tested using 232Th to breed the fissile isotope 233U (thorium fuel cycle

The thorium fuel cycle is a nuclear fuel cycle that uses an isotope of thorium, , as the fertile material. In the reactor, is transmuted into the fissile artificial uranium isotope which is the nuclear fuel. Unlike natural uranium, natural ...

) continue to be studied and developed.

While, in principle, all fission reactors can act in all three capacities, in practice the tasks lead to conflicting engineering goals and most reactors have been built with only one of the above tasks in mind. (There are several early counter-examples, such as the Hanford

Hanford may refer to:

Places

*Hanford (constituency), a constituency in Tuen Mun, People's Republic of China

*Hanford, Dorset, a village and parish in England

*Hanford, Staffordshire, England

*Hanford, California, United States

*Hanford, Iowa, ...

N reactor, now decommissioned).

As of 2019, the 448 nuclear power plants worldwide provided a capacity of 398 GWE, with about 85% being light-water cooled reactors such as pressurized water reactors

A pressurized water reactor (PWR) is a type of light-water nuclear reactor. PWRs constitute the large majority of the world's nuclear power plants (with notable exceptions being the UK, Japan, India and Canada).

In a PWR, water is used both as ...

or boiling water reactors

A boiling water reactor (BWR) is a type of nuclear reactor used for the generation of electrical power. It is the second most common type of electricity-generating nuclear reactor after the pressurized water reactor (PWR).

BWR are thermal neutro ...

. Energy from fission is transmitted through conduction or convection to the nuclear reactor coolant

A nuclear reactor coolant is a coolant in a nuclear reactor used to remove heat from the nuclear reactor core and transfer it to electrical generators and the environment.

Frequently, a chain of two coolant loops are used because the primary co ...

, then to a heat exchanger

A heat exchanger is a system used to transfer heat between a source and a working fluid. Heat exchangers are used in both cooling and heating processes. The fluids may be separated by a solid wall to prevent mixing or they may be in direct contac ...

, and the resultant generated steam is used to drive a turbine or generator.

Fission bombs

The objective of an atomic bomb is to produce a device, according to Serber, "...in which energy is released by a fast neutron chain reaction in one or more of the materials known to show nuclear fission." According to Rhodes, "Untamped, a bomb core even as large as twice the

The objective of an atomic bomb is to produce a device, according to Serber, "...in which energy is released by a fast neutron chain reaction in one or more of the materials known to show nuclear fission." According to Rhodes, "Untamped, a bomb core even as large as twice the critical mass

In nuclear engineering, critical mass is the minimum mass of the fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction in a particular setup. The critical mass of a fissionable material depends upon its nuclear properties (specific ...

would completely fission less than 1 percent of its nuclear material before it expanded enough to stop the chain reaction from proceeding. Tamper always increased efficiency: it reflected neutrons back into the core and its inertia...slowed the core's expansion and helped keep the core surface from blowing away." Rearrangement of the core material's subcritical components would need to proceed as fast as possible to ensure effective detonation. Additionally, a third basic component was necessary, "...an initiator—a Ra + Be source or, better, a Po + Be source, with the radium or polonium attached perhaps to one piece of the core and the beryllium to the other, to smash together and spray neutrons when the parts mated to start the chain reaction." However, any bomb would "necessitate locating, mining and processing hundreds of tons of uranium ore...", while U-235 separation or the production of Pu-239 would require additional industrial capacity.

History

Discovery of nuclear fission

The discovery of nuclear fission occurred in 1938 in the buildings of the

The discovery of nuclear fission occurred in 1938 in the buildings of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society

The Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science () was a German scientific institution established in the German Empire in 1911. Its functions were taken over by the Max Planck Society. The Kaiser Wilhelm Society was an umbrella organi ...

for Chemistry, today part of the Free University of Berlin

The Free University of Berlin (, often abbreviated as FU Berlin or simply FU) is a public university, public research university in Berlin, Germany. It was founded in West Berlin in 1948 with American support during the early Cold War period a ...

, following over four decades of work on the science of radioactivity

Radioactive decay (also known as nuclear decay, radioactivity, radioactive disintegration, or nuclear disintegration) is the process by which an unstable atomic nucleus loses energy by radiation. A material containing unstable nuclei is conside ...

and the elaboration of new nuclear physics that described the components of atoms. In 1911, Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who was a pioneering researcher in both Atomic physics, atomic and nuclear physics. He has been described as "the father of nu ...

proposed a model of the atom in which a very small, dense and positively charged nucleus of protons was surrounded by orbiting, negatively charged electrons (the Rutherford model

The Rutherford model is a name for the first model of an atom with a compact nucleus. The concept arose from Ernest Rutherford discovery of the nucleus. Rutherford directed the Geiger–Marsden experiment in 1909, which showed much more alpha ...

). Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (, ; ; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish theoretical physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and old quantum theory, quantum theory, for which he received the No ...

improved upon this in 1913 by reconciling the quantum behavior of electrons (the Bohr model

In atomic physics, the Bohr model or Rutherford–Bohr model was a model of the atom that incorporated some early quantum concepts. Developed from 1911 to 1918 by Niels Bohr and building on Ernest Rutherford's nuclear Rutherford model, model, i ...

). In 1928, George Gamow

George Gamow (sometimes Gammoff; born Georgiy Antonovich Gamov; ; 4 March 1904 – 19 August 1968) was a Soviet and American polymath, theoretical physicist and cosmologist. He was an early advocate and developer of Georges Lemaître's Big Ba ...

proposed the Liquid drop model

In nuclear physics, the semi-empirical mass formula (SEMF; sometimes also called the Weizsäcker formula, Bethe–Weizsäcker formula, or Bethe–Weizsäcker mass formula to distinguish it from the Bethe–Weizsäcker process) is used to approxima ...

, which became essential to understanding the physics

of fission.

In 1896, Henri Becquerel

Antoine Henri Becquerel ( ; ; 15 December 1852 – 25 August 1908) was a French nuclear physicist who shared the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics with Marie and Pierre Curie for his discovery of radioactivity.

Biography

Family and education

Becq ...

had found, and Marie Curie

Maria Salomea Skłodowska-Curie (; ; 7 November 1867 – 4 July 1934), known simply as Marie Curie ( ; ), was a Polish and naturalised-French physicist and chemist who conducted pioneering research on radioactivity.

She was List of female ...

named, radioactivity. In 1900, Rutherford and Frederick Soddy

Frederick Soddy FRS (2 September 1877 – 22 September 1956) was an English radiochemist who explained, with Ernest Rutherford, that radioactivity is due to the transmutation of elements, now known to involve nuclear reactions. He also pr ...

, investigating the radioactive gas emanating from thorium

Thorium is a chemical element; it has symbol Th and atomic number 90. Thorium is a weakly radioactive light silver metal which tarnishes olive grey when it is exposed to air, forming thorium dioxide; it is moderately soft, malleable, and ha ...

, "conveyed the tremendous and inevitable conclusion that the element thorium was slowly and spontaneously transmuting itself into argon gas!"

In 1919, following up on an earlier anomaly Ernest Marsden

Sir Ernest Marsden (19 February 1889 – 15 December 1970) was an English-New Zealand physicist. He is recognised internationally for his contributions to science while working under Ernest Rutherford, which led to the discovery of new theories ...

noted in 1915, Rutherford attempted to "break up the atom." Rutherford was able to accomplish the first artificial transmutation of nitrogen

Nitrogen is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a Nonmetal (chemistry), nonmetal and the lightest member of pnictogen, group 15 of the periodic table, often called the Pnictogen, pnictogens. ...

into oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

, using alpha particles directed at nitrogen 14N + α → 17O + p. Rutherford stated, "...we must conclude that the nitrogen atom is disintegrated," while the newspapers stated he had ''split the atom''. This was the first observation of a nuclear reaction, that is, a reaction in which particles from one decay are used to transform another atomic nucleus. It also offered a new way to study the nucleus. Rutherford and James Chadwick