Ichthyosaurs Of Europe on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ichthyosauria is an

In 1811, in

In 1811, in  In 1814, the Annings' specimen was described by Professor

In 1814, the Annings' specimen was described by Professor  Home was very uncertain how the animal should be classified. Though most individual skeletal elements looked very reptilian, the anatomy as a whole resembled that of a fish, so he initially assigned the creature to the fishes, as seemed to be confirmed by the flat shape of the vertebrae. At the same time, he considered it a transitional form between fishes and crocodiles, not in an evolutionary sense, but as regarded its place in the , the "Chain of Being" hierarchically connecting all living creatures. In 1818, Home noted some coincidental similarities between the coracoid of ichthyosaurians and the sternum of the

Home was very uncertain how the animal should be classified. Though most individual skeletal elements looked very reptilian, the anatomy as a whole resembled that of a fish, so he initially assigned the creature to the fishes, as seemed to be confirmed by the flat shape of the vertebrae. At the same time, he considered it a transitional form between fishes and crocodiles, not in an evolutionary sense, but as regarded its place in the , the "Chain of Being" hierarchically connecting all living creatures. In 1818, Home noted some coincidental similarities between the coracoid of ichthyosaurians and the sternum of the

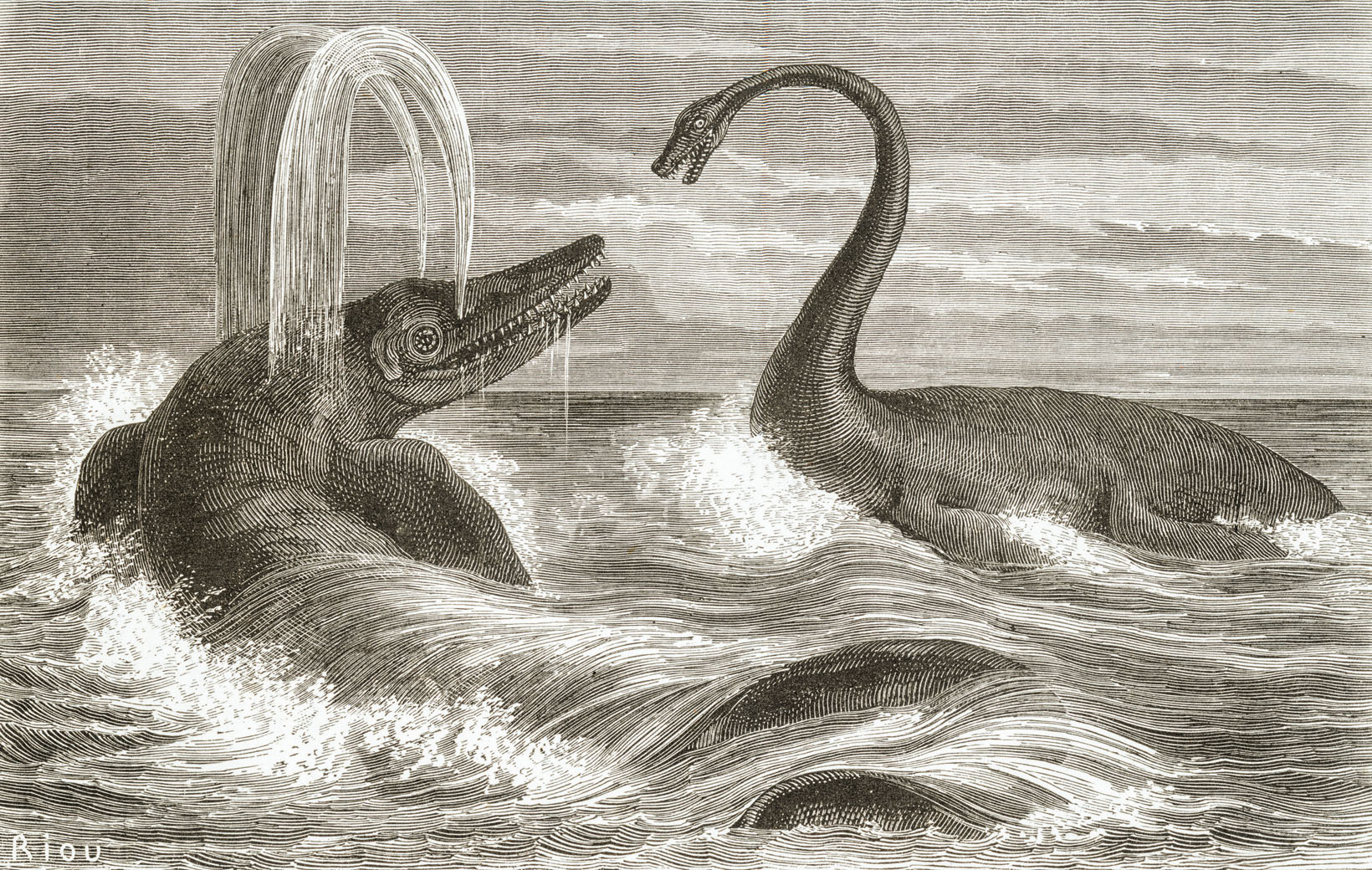

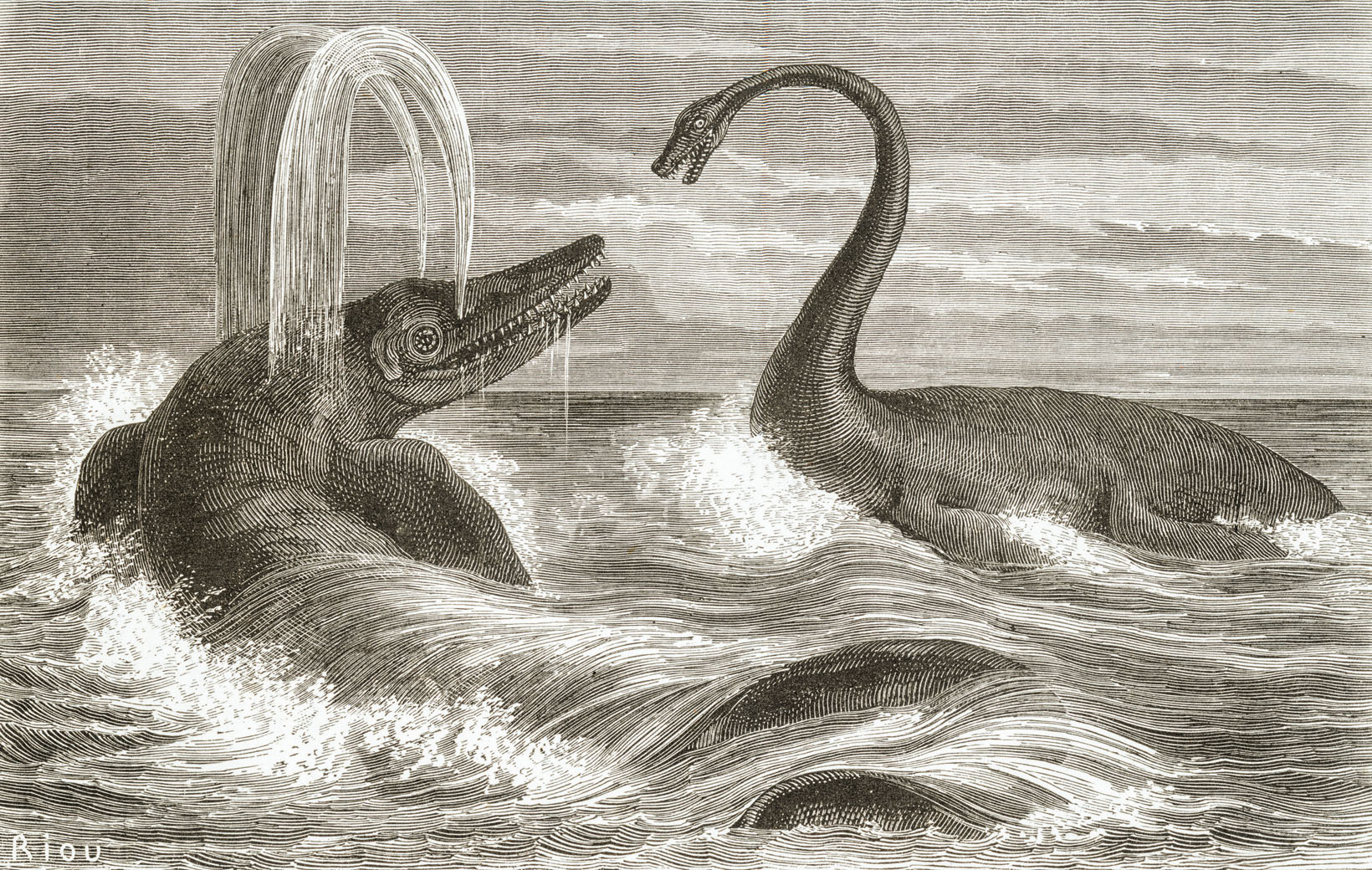

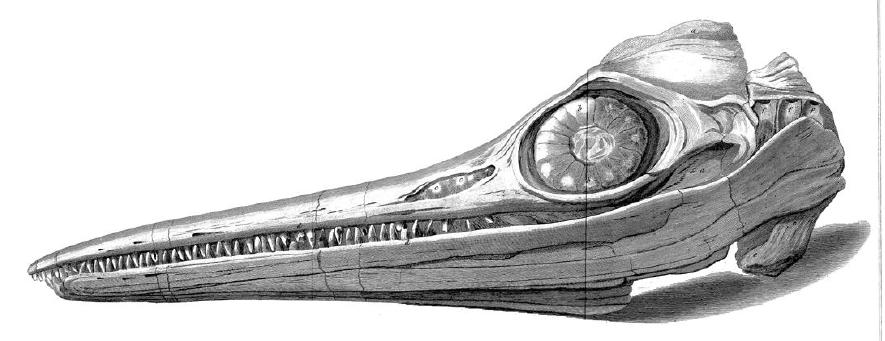

The discovery of a hitherto unsuspected extinct group of large marine reptiles generated much publicity, capturing the imagination of both scientists and the public at large. People were fascinated by the strange build of the animals, especially the large

The discovery of a hitherto unsuspected extinct group of large marine reptiles generated much publicity, capturing the imagination of both scientists and the public at large. People were fascinated by the strange build of the animals, especially the large  Public awareness was increased by the works of the eccentric collector Thomas Hawkins, a

Public awareness was increased by the works of the eccentric collector Thomas Hawkins, a  Ichthyosaurs became even more popular in 1854 by the rebuilding at

Ichthyosaurs became even more popular in 1854 by the rebuilding at

During the nineteenth century, the number of described ichthyosaur genera gradually increased. New finds allowed for a better understanding of their anatomy. Owen had noticed that many fossils showed a downward bend in the rear tail. At first, he explained this as a ''post mortem'' effect, a tendon pulling the tail end downwards after death. However, after an article on the subject by Philip Grey Egerton, Owen considered the possibility that the oblique section could have supported the lower lobe of a tail fin. This hypothesis was confirmed by new finds from

During the nineteenth century, the number of described ichthyosaur genera gradually increased. New finds allowed for a better understanding of their anatomy. Owen had noticed that many fossils showed a downward bend in the rear tail. At first, he explained this as a ''post mortem'' effect, a tendon pulling the tail end downwards after death. However, after an article on the subject by Philip Grey Egerton, Owen considered the possibility that the oblique section could have supported the lower lobe of a tail fin. This hypothesis was confirmed by new finds from

In the early twentieth century, ichthyosaur research was dominated by the German paleontologist

In the early twentieth century, ichthyosaur research was dominated by the German paleontologist

The origin of the ichthyosaurs is contentious. Until recently, clear transitional forms with land-dwelling vertebrate groups had not yet been found, the earliest known species of the ichthyosaur lineage being already fully aquatic. In 2014, a small basal ichthyosauriform from the upper Lower Triassic was described that had been discovered in China with characteristics suggesting an amphibious lifestyle. In 1937,

The origin of the ichthyosaurs is contentious. Until recently, clear transitional forms with land-dwelling vertebrate groups had not yet been found, the earliest known species of the ichthyosaur lineage being already fully aquatic. In 2014, a small basal ichthyosauriform from the upper Lower Triassic was described that had been discovered in China with characteristics suggesting an amphibious lifestyle. In 1937,

Since 1959, a second enigmatic group of ancient sea reptiles is known, the Hupehsuchia. Like the Ichthyopterygia, the Hupehsuchia have pointed snouts and show

Since 1959, a second enigmatic group of ancient sea reptiles is known, the Hupehsuchia. Like the Ichthyopterygia, the Hupehsuchia have pointed snouts and show

The basal forms quickly gave rise to ichthyosaurs in the narrow sense sometime around the boundary between the

The basal forms quickly gave rise to ichthyosaurs in the narrow sense sometime around the boundary between the  During the

During the

During the Early Jurassic, the ichthyosaurs still showed a large variety of species, ranging from in length. Many well-preserved specimens from England and Germany date to this time and well-known genera include ''

During the Early Jurassic, the ichthyosaurs still showed a large variety of species, ranging from in length. Many well-preserved specimens from England and Germany date to this time and well-known genera include ''

Traditionally, ichthyosaurs were seen as decreasing in diversity even further with the

Traditionally, ichthyosaurs were seen as decreasing in diversity even further with the

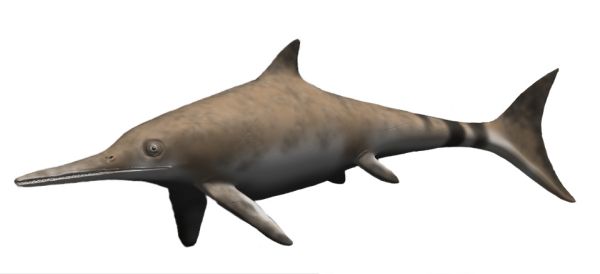

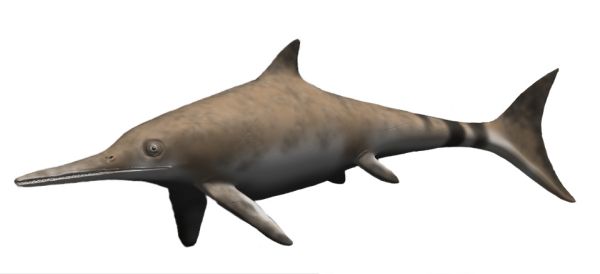

While the earliest known members of the ichthyosaur lineage were more eel-like in build, later ichthyosaurs resembled more typical fishes or dolphins, having a

While the earliest known members of the ichthyosaur lineage were more eel-like in build, later ichthyosaurs resembled more typical fishes or dolphins, having a

Basal Ichthyopterygia, like their land-dwelling ancestors, still had

Basal Ichthyopterygia, like their land-dwelling ancestors, still had  As derived species no longer have transversal processes on their vertebrae—again a condition unique in the Amniota—the parapophyseal and diapophysael rib joints have been reduced to flat facets, at least one of which is located on the vertebral body. The number of facets can be one or two; their profile can be circular or oval. Their shape often differs according to the position of the vertebra within the column. The presence of two facets per side does not imply that the rib itself is double-headed: often, even in that case, it has a single head. The ribs typically are very thin and possess a longitudinal groove on both the inner and the outer sides. The lower side of the chest is formed by

As derived species no longer have transversal processes on their vertebrae—again a condition unique in the Amniota—the parapophyseal and diapophysael rib joints have been reduced to flat facets, at least one of which is located on the vertebral body. The number of facets can be one or two; their profile can be circular or oval. Their shape often differs according to the position of the vertebra within the column. The presence of two facets per side does not imply that the rib itself is double-headed: often, even in that case, it has a single head. The ribs typically are very thin and possess a longitudinal groove on both the inner and the outer sides. The lower side of the chest is formed by

Basal forms have a forelimb that is still functionally differentiated, in some details resembling the arm of their land-dwelling forebears; the

Basal forms have a forelimb that is still functionally differentiated, in some details resembling the arm of their land-dwelling forebears; the  A strongly derived condition show the

A strongly derived condition show the

The earliest reconstructions of ichthyosaurs all omitted dorsal fins and caudal (tail) flukes, which were not supported by any hard skeletal structure, so were not preserved in many fossils. Only the lower tail lobe is supported by the vertebral column. In the early 1880s, the first body outlines of ichthyosaurs were discovered. In 1881, Richard Owen reported ichthyosaur body outlines showing tail flukes from Lower Jurassic rocks in Barrow-upon-Soar, England. Other well-preserved specimens have since shown that in some more primitive ichthyosaurs, like a specimen of ''

The earliest reconstructions of ichthyosaurs all omitted dorsal fins and caudal (tail) flukes, which were not supported by any hard skeletal structure, so were not preserved in many fossils. Only the lower tail lobe is supported by the vertebral column. In the early 1880s, the first body outlines of ichthyosaurs were discovered. In 1881, Richard Owen reported ichthyosaur body outlines showing tail flukes from Lower Jurassic rocks in Barrow-upon-Soar, England. Other well-preserved specimens have since shown that in some more primitive ichthyosaurs, like a specimen of ''

order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* A socio-political or established or existing order, e.g. World order, Ancien Regime, Pax Britannica

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

...

of large extinct

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

marine reptile

Marine reptiles are reptiles which have become secondarily adapted for an aquatic or semiaquatic life in a marine environment. Only about 100 of the 12,000 extant reptile species and subspecies are classed as marine reptiles, including mari ...

s sometimes referred to as "ichthyosaurs", although the term is also used for wider clades in which the order resides.

Ichthyosaurians thrived during much of the Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era is the Era (geology), era of Earth's Geologic time scale, geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous Period (geology), Periods. It is characterized by the dominance of archosaurian r ...

era; based on fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

evidence, they first appeared around 250 million years ago ( Ma) and at least one species survived until about 90 million years ago, into the Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the more recent of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''cre ...

. During the Early Triassic

The Early Triassic is the first of three epochs of the Triassic Period of the geologic timescale. It spans the time between 251.9 Ma and Ma (million years ago). Rocks from this epoch are collectively known as the Lower Triassic Series, which ...

epoch

In chronology and periodization, an epoch or reference epoch is an instant in time chosen as the origin of a particular calendar era. The "epoch" serves as a reference point from which time is measured.

The moment of epoch is usually decided b ...

, ichthyosaurs and other ichthyosauromorphs

The Ichthyosauromorpha are an extinct clade of Mesozoic marine reptiles consisting of the Ichthyosauriformes and the Hupehsuchia.

The node clade Ichthyosauromorpha was first defined by Ryosuke Motani ''et al.'' in 2014 as the group consisting ...

evolved from a group of unidentified land reptiles that returned to the sea, in a development similar to how the mammalian land-dwelling ancestors of modern-day dolphin

A dolphin is an aquatic mammal in the cetacean clade Odontoceti (toothed whale). Dolphins belong to the families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the New World river dolphins), Pontopori ...

s and whale

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully Aquatic animal, aquatic placental mammal, placental marine mammals. As an informal and Colloquialism, colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea ...

s returned to the sea millions of years later, which they gradually came to resemble in a case of convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last comm ...

. Ichthyosaurians were particularly abundant in the Late Triassic

The Late Triassic is the third and final epoch (geology), epoch of the Triassic geologic time scale, Period in the geologic time scale, spanning the time between annum, Ma and Ma (million years ago). It is preceded by the Middle Triassic Epoch a ...

and Early Jurassic

The Early Jurassic Epoch (geology), Epoch (in chronostratigraphy corresponding to the Lower Jurassic series (stratigraphy), Series) is the earliest of three epochs of the Jurassic Period. The Early Jurassic starts immediately after the Triassic� ...

periods, until they were replaced as the top aquatic predators by another marine reptilian group, the Plesiosauria

The Plesiosauria or plesiosaurs are an order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared in the latest Triassic Period, possibly in the Rhaetian stage, about 203 million year ...

, in the later Jurassic and Early Cretaceous

The Early Cretaceous (geochronology, geochronological name) or the Lower Cretaceous (chronostratigraphy, chronostratigraphic name) is the earlier or lower of the two major divisions of the Cretaceous. It is usually considered to stretch from 143.1 ...

, though previous views of ichthyosaur decline during this period are probably overstated. Ichthyosaurians diversity declined due to environmental volatility caused by climatic upheavals in the early Late Cretaceous, becoming extinct around the Cenomanian-Turonian boundary approximately 90 million years ago.

Scientists became aware of the existence of ichthyosaurians during the early 19th century, when the first complete skeletons were found in England. In 1834, the order Ichthyosauria was named. Later that century, many finely preserved ichthyosaurian fossils were discovered in Germany, including soft-tissue remains. Since the late 20th century, there has been a revived interest in the group, leading to an increased number of named ichthyosaurs from all continents, with over fifty genera known.

Ichthyosaurian species varied from in length. Ichthyosaurians resembled both modern fish and dolphins. Their limbs had been fully transformed into flippers, which sometimes contained a very large number of digits and phalanges

The phalanges (: phalanx ) are digit (anatomy), digital bones in the hands and foot, feet of most vertebrates. In primates, the Thumb, thumbs and Hallux, big toes have two phalanges while the other Digit (anatomy), digits have three phalanges. ...

. At least some species possessed a dorsal fin

A dorsal fin is a fin on the back of most marine and freshwater vertebrates. Dorsal fins have evolved independently several times through convergent evolution adapting to marine environments, so the fins are not all homologous. They are found ...

. Their heads were pointed, and the jaws often were equipped with conical teeth to catch smaller prey. Some species had larger, bladed teeth to attack large animals. The eyes were very large, for deep diving. The neck was short, and later species had a rather stiff trunk. These also had a more vertical tail fin, used for a powerful propulsive stroke. The vertebral column, made of simplified disc-like vertebrae, continued into the lower lobe of the tail fin. Ichthyosaurians were air-breathing, warm-blooded, and bore live young. Many, if not all, species had a layer of blubber

Blubber is a thick layer of Blood vessel, vascularized adipose tissue under the skin of all cetaceans, pinnipeds, penguins, and sirenians. It was present in many marine reptiles, such as Ichthyosauria, ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs.

Description ...

for insulation.

Like other ancient marine reptiles, such as those in the clades Mosasauria

Mosasauria is a clade of aquatic and semiaquatic squamates that lived during the Cretaceous period. Fossils belonging to the group have been found in all continents around the world. Early mosasaurians like dolichosaurs were small long-bodied ...

and Plesiosauria

The Plesiosauria or plesiosaurs are an order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared in the latest Triassic Period, possibly in the Rhaetian stage, about 203 million year ...

, the genera

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family as used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In binomial nomenclature, the genus name forms the first part of the binomial s ...

in Ichthyosauria are not part of the clade Dinosauria.

History of discoveries

Early finds

The first known illustrations of ichthyosaur bones, vertebrae, and limb elements were published by the WelshmanEdward Lhuyd

Edward Lhuyd (1660– 30 June 1709), also known as Edward Lhwyd and by other spellings, was a Welsh scientist, geographer, historian and antiquary. He was the second Keeper of the University of Oxford's Ashmolean Museum, and published the firs ...

in his of 1699. Lhuyd thought that they represented fish remains. In 1708, the Swiss naturalist Johann Jakob Scheuchzer

Johann Jakob Scheuchzer (2 August 1672 – 23 June 1733) was a Swiss physician and natural scientist born in Zürich. His most famous work was the ''Physica sacra'' in four volumes, which was a commentary on the Bible and included his view of ...

described two ichthyosaur vertebrae assuming they belonged to a man drowned in the Universal Deluge. In 1766, an ichthyosaur jaw with teeth was found at Weston

Weston may refer to:

Places Australia

* Weston, Australian Capital Territory, a suburb of Canberra

* Weston, New South Wales

* Weston Creek, a residential district of Canberra

* Weston Park, Canberra, a park

Canada

* Weston, Nova Scotia

* W ...

near Bath

Bath may refer to:

* Bathing, immersion in a fluid

** Bathtub, a large open container for water, in which a person may wash their body

** Public bathing, a public place where people bathe

* Thermae, ancient Roman public bathing facilities

Plac ...

. In 1783, this piece was exhibited by the Society for Promoting Natural History

A society () is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. So ...

as those of a crocodilian. In 1779, ichthyosaur bones were illustrated in John Walcott's ''Descriptions and Figures of Petrifications''. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, British fossil collections quickly increased in size. Those of the naturalists Ashton Lever

Sir Ashton Lever FRS (5 March 1729 – 28 January 1788) was an English collector of natural objects, in particular the Leverian collection., Manchester celebrities], retrieved 31 August 2010

Biography

Lever was born in 1729 at Alkrington, A ...

and John Hunter (surgeon), John Hunter were acquired in their totality by museums; later, it was established that they contained dozens of ichthyosaur bones and teeth. The bones had typically been labelled as belonging to fish, dolphins, or crocodiles; the teeth had been seen as those of sea lions.

The demand by collectors led to more intense commercial digging activities. In the early nineteenth century, this resulted in the discovery of more complete skeletons. In 1804, Edward Donovan

Edward Donovan (1768 – 1 February 1837) was an Anglo-Irish writer, natural history illustrator, and amateur zoologist. He did not travel, but collected, described and illustrated many species based on the collections of other naturalists. Hi ...

at St Donats

St Donats () is a village and community in the Vale of Glamorgan in south Wales, located just west of the small town of Llantwit Major. The community includes the village of Marcross and the hamlets of Monknash and East and West Monkton. It is ...

uncovered a ichthyosaur specimen containing a jaw, vertebrae, ribs, and a shoulder girdle. It was considered to be a giant lizard. In October 1805, a newspaper article reported the find of two additional skeletons, one discovered at Weston by Jacob Wilkinson

Jacob Wilkinson (c. 1722–1799) was an English businessman who served as an MP and as a director of the East India Company.

Career

According to Sir Lewis Namier, he was a Presbyterian from Berwick-upon-Tweed who became rich as a businessman ...

, the other, at the same village, by Reverend Peter Hawker. In 1807, the last specimen was described by the latter's cousin, Joseph Hawker

Joseph is a common male name, derived from the Hebrew (). "Joseph" is used, along with " Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the modern-day Nordic count ...

. This specimen thus gained some fame among geologists as 'Hawker's Crocodile'. In 1810, near Stratford-upon-Avon

Stratford-upon-Avon ( ), commonly known as Stratford, is a market town and civil parish in the Stratford-on-Avon (district), Stratford-on-Avon district, in the county of Warwickshire, in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands region of Engl ...

, an ichthyosaur jaw was found that was combined with plesiosaur

The Plesiosauria or plesiosaurs are an Order (biology), order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared in the latest Triassic Period (geology), Period, possibly in the Rhaetian st ...

bones to obtain a more complete specimen, indicating that the distinctive nature of ichthyosaurs was not yet understood, awaiting the discovery of far better fossils.

The first complete skeletons

In 1811, in

In 1811, in Lyme Regis

Lyme Regis ( ) is a town in west Dorset, England, west of Dorchester, Dorset, Dorchester and east of Exeter. Sometimes dubbed the "Pearl of Dorset", it lies by the English Channel at the Dorset–Devon border. It has noted fossils in cliffs and ...

, along the Jurassic Coast

The Jurassic Coast, also known as the Dorset and East Devon Coast, is a World Heritage Site on the English Channel coast of southern England. It stretches from Exmouth in East Devon to Studland Bay in Dorset, a distance of about , and was ins ...

of Dorset

Dorset ( ; Archaism, archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by Somerset to the north-west, Wiltshire to the north and the north-east, Hampshire to the east, t ...

, the first complete ichthyosaur skull was found by Joseph Anning, the brother of Mary Anning

Mary Anning (21 May 1799 – 9 March 1847) was an English fossil collector, fossil trade, dealer, and palaeontologist. She became known internationally for her discoveries in Jurassic marine fossil beds in the cliffs along the English Cha ...

, who in 1812 while still a young girl, secured the torso of the same specimen. Their mother, Molly Anning, sold the combined piece to squire Henry Henley for £23. Henley lent the fossil to the London Museum of Natural History of William Bullock. When this museum was closed, the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

bought the fossil for a price of £47/5s; it still belongs to the collection of the independent Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history scientific collection, collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleo ...

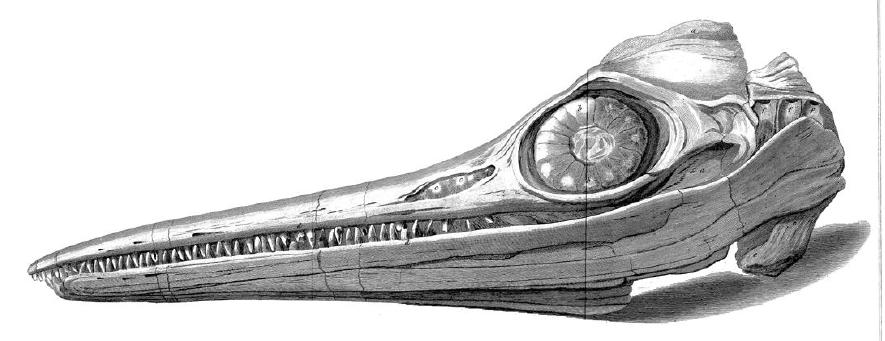

and has the inventory number NHMUK PV R1158 (formerly BMNH R.1158). It has been identified as a specimen of ''Temnodontosaurus

''Temnodontosaurus'' (meaning "cutting-tooth lizard") is an extinct genus of large ichthyosaurs that lived during the Lower Jurassic in what is now Europe and possibly Chile. The first known fossil is a specimen consisting of a complete skull a ...

platyodon''.

In 1814, the Annings' specimen was described by Professor

In 1814, the Annings' specimen was described by Professor Everard Home

Sir Everard Home, 1st Baronet, FRS (6 May 1756, in Kingston upon Hull – 31 August 1832, in London) was a British surgeon.

Life

Home was born in Kingston-upon-Hull and educated at Westminster School. He gained a scholarship to Trinity Colle ...

, in the first scientific publication dedicated to an ichthyosaur. Intrigued by the strange animal, Home tried to locate additional specimens in existing collections. In 1816, he described ichthyosaur fossils owned by William Buckland

William Buckland Doctor of Divinity, DD, Royal Society, FRS (12 March 1784 – 14 August 1856) was an English theologian, geologist and paleontology, palaeontologist.

His work in the early 1820s proved that Kirkdale Cave in North Yorkshire h ...

and James Johnson. In 1818, Home published data obtained by corresponding with naturalists all over Britain. In 1819, he wrote two articles about specimens found by Henry Thomas De la Beche and Thomas James Birch. A last publication of 1820 was dedicated to a discovery by Birch at Lyme Regis. The series of articles by Home covered the entire anatomy of ichthyosaurs, but highlighted details only; a systematic description was still lacking.

Home was very uncertain how the animal should be classified. Though most individual skeletal elements looked very reptilian, the anatomy as a whole resembled that of a fish, so he initially assigned the creature to the fishes, as seemed to be confirmed by the flat shape of the vertebrae. At the same time, he considered it a transitional form between fishes and crocodiles, not in an evolutionary sense, but as regarded its place in the , the "Chain of Being" hierarchically connecting all living creatures. In 1818, Home noted some coincidental similarities between the coracoid of ichthyosaurians and the sternum of the

Home was very uncertain how the animal should be classified. Though most individual skeletal elements looked very reptilian, the anatomy as a whole resembled that of a fish, so he initially assigned the creature to the fishes, as seemed to be confirmed by the flat shape of the vertebrae. At the same time, he considered it a transitional form between fishes and crocodiles, not in an evolutionary sense, but as regarded its place in the , the "Chain of Being" hierarchically connecting all living creatures. In 1818, Home noted some coincidental similarities between the coracoid of ichthyosaurians and the sternum of the platypus

The platypus (''Ornithorhynchus anatinus''), sometimes referred to as the duck-billed platypus, is a semiaquatic, egg-laying mammal endemic to eastern Australia, including Tasmania. The platypus is the sole living representative or monotypi ...

. This induced him to emphasize its status as a transitional form, combining, like the platypus, traits of several larger groups. In 1819, he considered it a form between newt

A newt is a salamander in the subfamily Pleurodelinae. The terrestrial juvenile phase is called an eft. Unlike other members of the family Salamandridae, newts are semiaquatic, alternating between aquatic and terrestrial habitats. Not all aqua ...

s, like the olm

The olm () or proteus (''Proteus anguinus'') is an aquatic salamander which is the only species in the genus ''Proteus'' of the family Proteidae and the only exclusively cave-dwelling chordate species found in Europe; the family's other extant g ...

, and lizards; he then gave a formal generic name: ''Proteo-Saurus''. However, in 1817, Karl Dietrich Eberhard Koenig had already referred to the animal as ''Ichthyosaurus'', "fish saurian" from Greek , , "fish". This name at the time was an invalid and was only published by Koenig in 1825, but was adopted by De la Beche in 1819 in a lecture where he named three ''Ichthyosaurus'' species. This text would only be published in 1822, just after De la Beche's friend William Conybeare published a description of these species, together with a fourth one. The type species

In International_Code_of_Zoological_Nomenclature, zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the spe ...

was ''Ichthyosaurus communis'', based on a lost skeleton. Conybeare considered that ''Ichthyosaurus'' had priority relative to ''Proteosaurus''. Although this is incorrect by modern standards, the latter name became a "forgotten" . In 1821, De la Beche and Conybeare provided the first systematic description of ichthyosaurs, comparing them to another newly identified marine reptile group, the Plesiosauria

The Plesiosauria or plesiosaurs are an order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared in the latest Triassic Period, possibly in the Rhaetian stage, about 203 million year ...

. Much of this description reflected the insights of their friend, the anatomist Joseph Pentland.

In 1835, the order Ichthyosauria was named by Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville

Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville (; 12 September 1777 – 1 May 1850) was a French zoologist and anatomist.

Life

Blainville was born at Arques-la-Bataille, Arques, near Dieppe, Seine-Maritime, Dieppe. As a young man, he went to Paris to study a ...

. In 1840, Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

named an order Ichthyopterygia

Ichthyopterygia ("fish flippers") was a designation introduced by Richard Owen, Sir Richard Owen in 1840 to designate the Jurassic ichthyosaurs that were known at the time, but the term is now used more often for both true Ichthyosauria and their ...

as an alternative concept.

Popularisation during the 19th century

The discovery of a hitherto unsuspected extinct group of large marine reptiles generated much publicity, capturing the imagination of both scientists and the public at large. People were fascinated by the strange build of the animals, especially the large

The discovery of a hitherto unsuspected extinct group of large marine reptiles generated much publicity, capturing the imagination of both scientists and the public at large. People were fascinated by the strange build of the animals, especially the large scleral ring

The scleral ring or sclerotic ring is a hardened ring of plates, often derived from bone, that is found in the eyes of many animals in several groups of vertebrates. Some species of mammals, amphibians, and crocodilians lack scleral rings. The ring ...

s in the eye sockets, of which it was sometimes erroneously assumed these would have been visible on the living animal. Their bizarre form induced a feeling of alienation, allowing people to realise the immense span of time passed since the era in which the ichthyosaur swam the oceans. Not all were convinced that ichthyosaurs had gone extinct: Reverend George Young

George Young may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* George Young (filmmaker), Australian stage manager and film director in the silent era

* George Young (rock musician) (1946–2017), Australian musician, songwriter, and record producer

* G ...

found a skeleton in 1819 at Whitby

Whitby is a seaside town, port and civil parish in North Yorkshire, England. It is on the Yorkshire Coast at the mouth of the River Esk, North Yorkshire, River Esk and has a maritime, mineral and tourist economy.

From the Middle Ages, Whitby ...

; in his 1821 description, he expressed the hope that living specimens could still be found. Geologist Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known today for his association with Charles ...

, to the contrary, assumed that the Earth was eternal so that in the course of time the ichthyosaur might likely reappear, a possibility lampooned in a famous caricature by De la Beche.

Public awareness was increased by the works of the eccentric collector Thomas Hawkins, a

Public awareness was increased by the works of the eccentric collector Thomas Hawkins, a pre-Adamite

The pre-Adamite hypothesis or pre-Adamism is the theological belief that humans (or intelligent yet non-human creatures) existed before the biblical character Adam. Pre-Adamism is therefore distinct from the conventional Abrahamic belief that Ad ...

believing that ichthyosaurs were monstrous creations by the devil: ''Memoirs of Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri'' of 1834 and ''The Book of the Great Sea-Dragons'' of 1840. The first work was illustrated by mezzotint

Mezzotint is a monochrome printmaking process of the intaglio (printmaking), intaglio family. It was the first printing process that yielded half-tones without using line- or dot-based techniques like hatching, cross-hatching or stipple. Mezzo ...

s by John Samuelson Templeton. These publications also contained scientific descriptions and represented the first textbooks of the subject. In the summer of 1834, Hawkins, after a taxation by William Buckland

William Buckland Doctor of Divinity, DD, Royal Society, FRS (12 March 1784 – 14 August 1856) was an English theologian, geologist and paleontology, palaeontologist.

His work in the early 1820s proved that Kirkdale Cave in North Yorkshire h ...

and Gideon Mantell

Gideon Algernon Mantell Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons, MRCS Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (3 February 1790 – 10 November 1852) was an English obstetrician, geologist and paleontology, palaeontologist. His attempts to reconstr ...

, sold his extensive collection, then the largest of its kind in the world, to the British Museum. However, curator Koenig quickly discovered that the fossils had been heavily restored with plaster, applied by an Italian artist from Lucca

Città di Lucca ( ; ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, Central Italy, on the Serchio River, in a fertile plain near the Ligurian Sea. The city has a population of about 89,000, while its Province of Lucca, province has a population of 383,9 ...

; of the most attractive piece, an ''Ichthyosaurus'' specimen, almost the entire tail was fake. It turned out that Professor Buckland had been aware of this beforehand, and the museum was forced to reach a settlement with Hawkins, and gave the fake parts a lighter colour to differentiate them from the authentic skeletal elements.

Ichthyosaurs became even more popular in 1854 by the rebuilding at

Ichthyosaurs became even more popular in 1854 by the rebuilding at Sydenham Hill

Sydenham Hill forms part of Norwood Ridge, a longer ridge and is an affluent Human settlement, locality in southeast London. It is also the name of a road which runs along the northeastern part of the ridge, demarcating the London Boroughs of ...

of the Crystal Palace

The Crystal Palace was a cast iron and plate glass structure, originally built in Hyde Park, London, to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. The exhibition took place from 1 May to 15 October 1851, and more than 14,000 exhibitors from around ...

, originally erected at the world exhibition of 1851. In the surrounding park, life-sized, painted, concrete statues of extinct animals were placed, which were designed by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (8 February 1807 – 27 January 1894) was an English sculptor and natural history artist renowned for his work on the life-size models of dinosaurs in the Crystal Palace Park in south London. The models, accurately ...

under the direction of Richard Owen. Among them were three models of an ichthyosaur. Although it was known that ichthyosaurs had been animals of the open seas, they were shown basking on the shore, a convention followed by many nineteenth century illustrations with the aim, as Conybeare once explained, of better exposing their build. This led to the misunderstanding that they really had an amphibious lifestyle. The pools in the park were at the time subjected to tidal changes, so that fluctuations in the water level at intervals submerged the ichthyosaur statues, adding a certain realism. Remarkably, internal skeletal structures, such as the scleral rings and the many phalanges of the flippers, were shown at the outside.

Later 19th-century finds

During the nineteenth century, the number of described ichthyosaur genera gradually increased. New finds allowed for a better understanding of their anatomy. Owen had noticed that many fossils showed a downward bend in the rear tail. At first, he explained this as a ''post mortem'' effect, a tendon pulling the tail end downwards after death. However, after an article on the subject by Philip Grey Egerton, Owen considered the possibility that the oblique section could have supported the lower lobe of a tail fin. This hypothesis was confirmed by new finds from

During the nineteenth century, the number of described ichthyosaur genera gradually increased. New finds allowed for a better understanding of their anatomy. Owen had noticed that many fossils showed a downward bend in the rear tail. At first, he explained this as a ''post mortem'' effect, a tendon pulling the tail end downwards after death. However, after an article on the subject by Philip Grey Egerton, Owen considered the possibility that the oblique section could have supported the lower lobe of a tail fin. This hypothesis was confirmed by new finds from Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

. In the Posidonia Shale

The Posidonia Shale (, also called Schistes Bitumineux in Luxembourg) geologically known as the Sachrang Formation, is an Early Jurassic (Early to Late Toarcian) geological formation in Germany, northern Switzerland, northwestern Austria, souther ...

at Holzmaden

Holzmaden is a town in Baden-Württemberg, Germany that lies between Stuttgart and Ulm.

Holzmaden is 4 km south-east from Kirchheim unter Teck and 19 km south-east of Esslingen am Neckar. The A 8 runs south from Holzmaden. The town a ...

, dating from the early Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 143.1 Mya. ...

, already in the early nineteenth century, the first ichthyosaur skeletons had been found. During the latter half of the century, the rate of discovery increased to a few hundred each year. Ultimately, over four thousand were uncovered, forming the bulk of ichthyosaur specimens displayed. The sites were also a , meaning not only the quantity, but also the quality was exceptional. The skeletons were very complete and often preserved soft tissues, including tail and dorsal fins. Additionally, female individuals were discovered with embryos.

20th century

In the early twentieth century, ichthyosaur research was dominated by the German paleontologist

In the early twentieth century, ichthyosaur research was dominated by the German paleontologist Friedrich von Huene

Baron Friedrich Richard von Hoyningen-Huene (22 March 1875 – 4 April 1969) was a German nobleman paleontologist who described a large number of dinosaurs, more than anyone else in 20th-century Europe. He studied a range of Permo-Carbonife ...

, who wrote an extensive series of articles, taking advantage of an easy access to the many specimens found in his country. The amount of anatomical data was hereby vastly increased. Von Huene also travelled widely abroad, describing many fossils from locations outside of Europe. During the 20th century, North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

became an important source of new fossils. In 1905, the Saurian Expedition led by John Campbell Merriam

John Campbell Merriam (October 20, 1869 – October 30, 1945) was an American paleontologist, educator, and conservationist. The first vertebrate paleontologist on the West Coast of the United States, he is best known for his taxonomy of ve ...

and financed by Annie Montague Alexander

Annie Montague Alexander (29 December 1867 – 10 September 1950) was an Exploration, explorer, Natural history, naturalist, Paleontology, paleontological collector, and Philanthropy, philanthropist.

She founded the University of California Museu ...

, found twenty-five specimens in central Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a landlocked state in the Western United States. It borders Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. Nevada is the seventh-most extensive, th ...

, which were under a shallow ocean during the Triassic. Several of these are in the collection of the University of California

The University of California (UC) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university, research university system in the U.S. state of California. Headquartered in Oakland, California, Oakland, the system is co ...

Museum of Paleontology.

After a slack during the middle of the century, with no new genera being named between the 1930s and the 1970s, the rate of discoveries picked up towards its end. Other specimens are embedded in the rock and visible at Berlin–Ichthyosaur State Park

Berlin–Ichthyosaur State Park is a public recreation area and historic preserve that protects undisturbed ichthyosaur fossils and the ghost town of Berlin in far northwestern Nye County, Nevada. The state park covers more than at an elevatio ...

in Nye County

Nye County is a county in the U.S. state of Nevada. As of the 2020 census, the population was 51,591. Its county seat is Tonopah. At , Nye is Nevada's largest county by area and the third-largest county in the contiguous United States, beh ...

. In 1977 the Triassic ichthyosaur ''Shonisaurus'' became the state fossil

Most states in the US have designated a state fossil, many during the 1980s. It is common to designate a fossilized species, rather than a single specimen or a category of fossils. State fossils are distinct from other state emblems like state d ...

of Nevada. About half of the ichthyosaur genera determined to be valid were described after 1990. In 1992 Canadian paleontologist Elizabeth Nicholls

Elizabeth (Betsy) Laura Nicholls (January 31, 1946 – October 18, 2004) was an American-Canadian paleontologist who specialized in Triassic marine reptiles. She was a paleontologist at the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Alberta, Canada.

Early l ...

uncovered the largest known specimen, a ''Shastasaurus

''Shastasaurus'' ("Mount Shasta lizard") is an extinct genus of ichthyosaur from the Late Triassic.Hilton, Richard P., ''Dinosaurs and Other Mesozoic Animals of California'', University of California Press, Berkeley 2003 , at pages 90-91. Specime ...

''. The new finds have allowed a gradual improvement in knowledge about the anatomy and physiology of what had already been seen as rather advanced "Mesozoic dolphins". Christopher McGowan published a larger number of articles and also brought the group to the attention of the general public. The new method of cladistics

Cladistics ( ; from Ancient Greek 'branch') is an approach to Taxonomy (biology), biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesiz ...

provided a means to exactly calculate the relationships between groups of animals, and in 1999, Ryosuke Motani published the first extensive study on ichthyosaur phylogenetics

In biology, phylogenetics () is the study of the evolutionary history of life using observable characteristics of organisms (or genes), which is known as phylogenetic inference. It infers the relationship among organisms based on empirical dat ...

.

21st century

In 2003, McGowan and Motani published the first modern textbook on the Ichthyosauria and their closest relatives. Two jawbones of gigantic ichthyosaur were discovered in 2016 and 2020 in Lilstock and Somerset respectively, UK. Simple scaling would suggest that this ichthyosaur has an estimated total length of up to 26 meters (82 feet), the largest known to date marine reptile. The fossils of this individual were dated to be 202 million-year-old.Evolutionary history

Origin

The origin of the ichthyosaurs is contentious. Until recently, clear transitional forms with land-dwelling vertebrate groups had not yet been found, the earliest known species of the ichthyosaur lineage being already fully aquatic. In 2014, a small basal ichthyosauriform from the upper Lower Triassic was described that had been discovered in China with characteristics suggesting an amphibious lifestyle. In 1937,

The origin of the ichthyosaurs is contentious. Until recently, clear transitional forms with land-dwelling vertebrate groups had not yet been found, the earliest known species of the ichthyosaur lineage being already fully aquatic. In 2014, a small basal ichthyosauriform from the upper Lower Triassic was described that had been discovered in China with characteristics suggesting an amphibious lifestyle. In 1937, Friedrich von Huene

Baron Friedrich Richard von Hoyningen-Huene (22 March 1875 – 4 April 1969) was a German nobleman paleontologist who described a large number of dinosaurs, more than anyone else in 20th-century Europe. He studied a range of Permo-Carbonife ...

even hypothesised that ichthyosaurs were not reptiles, but instead represented a lineage separately developed from amphibians. Today, this notion has been discarded and a consensus exists that ichthyosaurs are amniote

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial animal, terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolution, evolved from amphibious Stem tet ...

tetrapod

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek :wiktionary:τετρα-#Ancient Greek, τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and :wiktionary:πούς#Ancient Greek, πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four-Limb (anatomy), limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetr ...

s, having descended from terrestrial egg-laying amniotes during the late Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years, from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.902 Mya. It is the s ...

or the earliest Triassic. However, establishing their position within the amniote evolutionary tree has proven difficult, due to their heavily derived morphology obscuring their ancestry. Several conflicting hypotheses have been posited on the subject. In the second half of the 20th century, ichthyosaurs were usually assumed to be of the Anapsida

An anapsid is an amniote whose skull lacks one or more skull openings (fenestra, or fossae) near the temples. Traditionally, the Anapsida are considered the most primitive subclass of amniotes, the ancestral stock from which Synapsida and Diaps ...

, seen as an early branch of "primitive" reptiles. This would explain the early appearance of ichthyosaurs in the fossil record, and also their lack of clear affinities with other reptile groups, as anapsids were supposed to be little specialised. This hypothesis has become unpopular for being inherently vague because Anapsida is an unnatural, paraphyletic

Paraphyly is a taxonomic term describing a grouping that consists of the grouping's last common ancestor and some but not all of its descendant lineages. The grouping is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In co ...

group. Modern exact quantitative cladistic analyses consistently indicate that ichthyosaurs are members of the clade Diapsida

Diapsids ("two arches") are a clade of sauropsids, distinguished from more primitive eureptiles by the presence of two holes, known as temporal fenestrae, in each side of their skulls. The earliest traditionally identified diapsids, the araeosc ...

. Some studies showed a basal, or low, position in the diapsid tree. More analyses result in their being Neodiapsida, a derived diapsid subgroup.

Since the 1980s, a close relationship was assumed between the Ichthyosauria and the Sauropterygia

Sauropterygia ("lizard flippers") is an extinct taxon of diverse, aquatic diapsid reptiles that developed from terrestrial ancestors soon after the end-Permian extinction and flourished during the Triassic before all except for the Plesiosau ...

, another marine reptile group, within an overarching Euryapsida __NOTOC__

Euryapsida is a polyphyletic (unnatural, as the various members are not closely related) group of sauropsids that are distinguished by a single temporal fenestra, an opening behind the orbit, under which the post-orbital and squamosal bo ...

, with one such study in 1997 by John Merck showing them to be monophyletic

In biological cladistics for the classification of organisms, monophyly is the condition of a taxonomic grouping being a clade – that is, a grouping of organisms which meets these criteria:

# the grouping contains its own most recent co ...

archosauromorph euryapsids. This has been contested over the years, with the Euryapsida being seen as an unnatural polyphyletic assemblage of reptiles that happen to share some adaptations to a swimming lifestyle. However, more recent studies have shown further support for a monophyletic clade between Ichthyosauromorpha

The Ichthyosauromorpha are an extinct clade of Mesozoic marine reptiles consisting of the Ichthyosauriformes and the Hupehsuchia.

The node clade Ichthyosauromorpha was first defined by Ryosuke Motani ''et al.'' in 2014 as the group consisting ...

, Sauropterygia, and Thalattosauria

Thalattosauria ( Greek for "sea lizards") is an extinct order of marine reptiles that lived during the Triassic Period. Thalattosaurs were diverse in size and shape, and are divided into two superfamilies: Askeptosauroidea and Thalattosauroide ...

as a massive marine clade of aquatic archosauromorphs originating in the Late Permian and diversifying in the Early Triassic.

Affinity with the Hupehsuchia

Since 1959, a second enigmatic group of ancient sea reptiles is known, the Hupehsuchia. Like the Ichthyopterygia, the Hupehsuchia have pointed snouts and show

Since 1959, a second enigmatic group of ancient sea reptiles is known, the Hupehsuchia. Like the Ichthyopterygia, the Hupehsuchia have pointed snouts and show polydactyly

Polydactyly is a birth defect that results in extra fingers or toes. The hands are more commonly involved than the feet. Extra fingers may be painful, affect self-esteem, or result in clumsiness.

It is associated with at least 39 genetic mut ...

, the possession of more than five fingers or toes. Their limbs more resemble those of land animals, making them appear as a transitional form between these and ichthyosaurs. Initially, this possibility was largely neglected because the Hupehsuchia have a fundamentally different form of propulsion, with an extremely stiffened trunk. The similarities were explained as a case of convergent evolution. Furthermore, the descent of the Hupehsuchia is no less obscure, meaning a possible close relationship would hardly clarify the general evolutionary position of the ichthyosaurs.

In 2014, ''Cartorhynchus

''Cartorhynchus'' (meaning "shortened snout") is an extinct genus of basal (phylogenetics), early ichthyosauriformes, ichthyosauriform marine reptile that lived during the Early Triassic epoch (geology), epoch, about 248 million years ago. The g ...

'' was announced, a small species with a short snout, large flippers, and a stiff trunk. Its lifestyle might have been amphibious. Motani found it to be more basal than the Ichthyopterygia and named an encompassing clade Ichthyosauriformes

The Ichthyosauriformes are a group of marine reptiles, belonging to the Ichthyosauromorpha, that lived during the Mesozoic.

The stem clade Ichthyosauriformes was in 2014 defined by Ryosuke Motani and colleagues as the group consisting of all ich ...

. The latter group was combined with the Hupesuchia into the Ichthyosauromorpha

The Ichthyosauromorpha are an extinct clade of Mesozoic marine reptiles consisting of the Ichthyosauriformes and the Hupehsuchia.

The node clade Ichthyosauromorpha was first defined by Ryosuke Motani ''et al.'' in 2014 as the group consisting ...

. The ichthyosauromorphs were found to be diapsids.

The proposed relationships are shown by this cladogram:

Early Ichthyopterygia

The earliest ichthyosaurs are known from the Early and Early-Middle (Olenekian

In the geologic timescale, the Olenekian is an age (geology), age in the Early Triassic epoch (geology), epoch; in chronostratigraphy, it is a stage (stratigraphy), stage in the Lower Triassic series (stratigraphy), series. It spans the time betw ...

and Anisian

In the geologic timescale, the Anisian is the lower stage (stratigraphy), stage or earliest geologic age, age of the Middle Triassic series (stratigraphy), series or geologic epoch, epoch and lasted from million years ago until million years ag ...

) Triassic strata of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

, and Spitsbergen

Spitsbergen (; formerly known as West Spitsbergen; Norwegian language, Norwegian: ''Vest Spitsbergen'' or ''Vestspitsbergen'' , also sometimes spelled Spitzbergen) is the largest and the only permanently populated island of the Svalbard archipel ...

in Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

, being up to 246 million years old. These first forms included the genera ''Chaohusaurus

''Chaohusaurus'' is an extinct genus of basal ichthyosauriform, depending on definition possibly ichthyosaur, from the Early Triassic of Chaohu and Yuanan, China.

Discovery and naming

The type species ''Chaohusaurus geishanensis'' was name ...

'', ''Grippia

''Grippia'' is a genus of early ichthyopterygian, an extinct group of reptiles that resembled dolphins. Its only species is ''Grippia longirostris''. It was a relatively small ichthyopterygian, measuring around long. Fossil remains from Svalba ...

'', and ''Utatsusaurus

''Utatsusaurus hataii'' is the earliest-known ichthyopterygian which lived in the Early Triassic period (c. 245–250 million years ago). It was nearly long with a slender body. The first specimen was found in Utatsu-cho (now part of Minamisa ...

''. Even older fossils show they were around 250 million years ago, just two million years after the Permian mass extinction. This early diversity suggests an even earlier origin, possibly late Permian. They more resembled finned lizards than the fishes or dolphins to which the later, more familiar species were similar. Their bodies were elongated and they probably used an anguilliform

Fish locomotion is the various types of animal locomotion used by fish, principally by aquatic locomotion, swimming. This is achieved in different groups of fish by a variety of mechanisms of propulsion, most often by wave-like lateral flexions ...

locomotion, swimming by undulations of the entire trunk. Like land animals, their pectoral girdles and pelves were robustly built, and their vertebrae still possessed the usual interlocking processes to support the body against the force of gravity. However, they were already rather advanced in having limbs that had been completely transformed into flippers. They also were probably warm-blooded and viviparous

In animals, viviparity is development of the embryo inside the body of the mother, with the maternal circulation providing for the metabolic needs of the embryo's development, until the mother gives birth to a fully or partially developed juve ...

.

These very early "proto-ichthyosaurs" had such a distinctive build compared to "ichthyosaurs proper" that Motani excluded them from the Ichthyosauria and placed them in a basal position in a larger clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

, the Ichthyopterygia

Ichthyopterygia ("fish flippers") was a designation introduced by Richard Owen, Sir Richard Owen in 1840 to designate the Jurassic ichthyosaurs that were known at the time, but the term is now used more often for both true Ichthyosauria and their ...

. However, this solution was not adopted by all researchers.

Later Triassic forms

The basal forms quickly gave rise to ichthyosaurs in the narrow sense sometime around the boundary between the

The basal forms quickly gave rise to ichthyosaurs in the narrow sense sometime around the boundary between the Early Triassic

The Early Triassic is the first of three epochs of the Triassic Period of the geologic timescale. It spans the time between 251.9 Ma and Ma (million years ago). Rocks from this epoch are collectively known as the Lower Triassic Series, which ...

and Middle Triassic

In the geologic timescale, the Middle Triassic is the second of three epoch (geology), epochs of the Triassic period (geology), period or the middle of three series (stratigraphy), series in which the Triassic system (stratigraphy), system is di ...

; the earliest Ichthyosauria in the sense Motani gave to the concept, appear about 245 million years ago. These later diversified into a variety of forms, including the still sea serpent

A sea serpent is a type of sea monster described in various mythologies, most notably in Mesopotamian cosmology (Tiamat), Ugaritic cosmology ( Yam, Tannin), biblical cosmology (Leviathan, Rahab), Greek cosmology (Cetus, Echidna, Hydra, Scy ...

-like ''Cymbospondylus

''Cymbospondylus'' (meaning "cupped vertebrae") is an extinct genus of large ichthyosaurs, of which it is among the oldest representatives, that lived from the Lower to Middle Triassic in what are now North America and Europe. The first known fo ...

'', a problematic form which reached ten metres in length, and smaller, more typical forms like ''Mixosaurus

''Mixosaurus'' is an extinct genus of Middle Triassic (Anisian to Ladinian, about 250-240 Mya) ichthyosaur. Its fossils have been found near the Italy–Switzerland border and in South China.

The genus was named in 1887 by George H. Baur. The n ...

''. The Mixosauria were already very fish-like with a pointed skull, a shorter trunk, a more vertical tail fin, a dorsal fin, and short flippers containing many phalanges. The sister group of the Mixosauria were the more advanced Merriamosauria

Merriamosauria is an extinct clade of ichthyosaurs. It was named by Ryosuke Motani in his 1999 analysis of the relationships of ichthyopterygian marine reptiles and was defined in phylogenetic terms as a stem-based taxon including "the last co ...

. By the Late Triassic

The Late Triassic is the third and final epoch (geology), epoch of the Triassic geologic time scale, Period in the geologic time scale, spanning the time between annum, Ma and Ma (million years ago). It is preceded by the Middle Triassic Epoch a ...

, merriamosaurs consisted of both the large, classic Shastasauria

Shastasauridae is an extinct family (biology), family of ichthyosaurs from the Late Triassic with a possible Early Jurassic record. The family contains the largest known species of ichthyosaurs, which include some of and possibly the largest known ...

and more advanced, "dolphin-like" Euichthyosauria. Experts disagree over whether these represent an evolutionary continuum, with the less specialised shastosaurs a paraphyletic grade that was evolving into the more advanced forms, or whether the two were separate clades that evolved from a common ancestor earlier on. Euichthyosauria possessed more narrow front flippers, with a reduced number of fingers. Basal euichthyosaurs were ''Californosaurus

''Californosaurus'' ('California lizard') is an extinct genus of ichthyosaur, an extinct marine reptile, from the Lower Hosselkus Limestone (Carnian, Late Triassic) of California, and also the Muschelkalk (Ladinian, Middle Triassic) of Germany.

...

'' and ''Toretocnemus

''Toretocnemus'' (meaning 'perforated tibia') is an extinct genus of ichthyosaurs that lived during the Carnian Stage (stratigraphy), stage of the Upper Triassic in what is now North America. Two species are known, ''T. californicus'' and ''T. zi ...

''. A more derived branch were the Parvipelvia

Parvipelvia (Latin for "little pelvis" - ''parvus'' meaning "little" and ''pelvis'' meaning "pelvis") is an extinct clade of euichthyosaur ichthyosaurs that existed from the Late Triassic to the early Late Cretaceous (middle Norian to Cenomanian ...

, with a reduced pelvis, basal forms of which are ''Hudsonelpidia

''Hudsonelpidia'' is an extinct genus of small parvipelvian ichthyosaur known from British Columbia of Canada.

Description

''Hudsonelpidia'' is known only from the holotype, a nearly complete skeleton measuring less than long. It was collected ...

'' and ''Macgowania

''Macgowania'' is an extinct genus of parvipelvian ichthyosaur known from British Columbia of Canada. It was a small ichthyosaur around in total body length.

History of research

The first specimen of ''Macgowania'' is the holotype ROM 419 ...

''.

During the

During the Carnian

The Carnian (less commonly, Karnian) is the lowermost stage (stratigraphy), stage of the Upper Triassic series (stratigraphy), Series (or earliest age (geology), age of the Late Triassic Epoch (reference date), Epoch). It lasted from 237 to 227.3 ...

and Norian

The Norian is a division of the Triassic geological period, Period. It has the rank of an age (geology), age (geochronology) or stage (stratigraphy), stage (chronostratigraphy). It lasted from ~227.3 to Mya (unit), million years ago. It was prec ...

, Shastosauria reached huge sizes. ''Shonisaurus

''Shonisaurus'' is a genus of very large ichthyosaurs. At least 37 incomplete fossil specimens of the type species, ''Shonisaurus popularis'', have been found in the Luning Formation of Nevada, USA. This formation dates to the late Carnian-earl ...

popularis'', known from a number of specimens from the Carnian of Nevada, was long. Norian Shonisauridae are known from both sides of the Pacific. ''Himalayasaurus

''Himalayasaurus'' is an extinct genus of ichthyosaur from the Late Triassic Qulonggongba Formation of Tibet. The type species ''Himalayasaurus tibetensis'' was described in 1972 on the basis of fragmentary remains, including teeth, limb bones, ...

tibetensis'' and '' Tibetosaurus'' (probably a synonym

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means precisely or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are a ...

) have been found in Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ), or Greater Tibet, is a region in the western part of East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are other ethnic groups s ...

. These large (10- to 15-m-long) ichthyosaurs have by some been placed into the genus ''Shonisaurus''.

The gigantic ''Shonisaurus sikanniensis'' (considered as a shastasaurus between 2011 and 2013) whose remains were found in the Pardonet Formation

The Schooler Creek Group is a stratigraphic unit of Middle Triassic, Middle to Late Triassic (Ladinian to Norian) Geochronology, age in the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin. It is present in northeastern British Columbia. It was named for School ...

of British Columbia

British Columbia is the westernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Situated in the Pacific Northwest between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains, the province has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that ...

, has been estimated to be as much as in length. ''Ichthyotitan'', found in Somerset

Somerset ( , ), Archaism, archaically Somersetshire ( , , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel, Gloucestershire, and Bristol to the north, Wiltshire to the east ...

, has been estimated to be as much as 26 m long—if correct, the largest marine reptile known to date.

In the Late Triassic, ichthyosaurs attained the peak of their size and diversity. They occupied many ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of Resource (biology), resources an ...

s. Some were apex predator

An apex predator, also known as a top predator or superpredator, is a predator at the top of a food chain, without natural predators of its own.

Apex predators are usually defined in terms of trophic dynamics, meaning that they occupy the hig ...

s; others were hunters of small prey. Several species perhaps specialised in suction feeding

Aquatic feeding mechanisms face a special difficulty as compared to feeding on land, because the density of water is about the same as that of the prey, so the prey tends to be pushed away when the mouth is closed. This problem was first identifi ...

or were ram feed

Aquatic feeding mechanisms face a special difficulty as compared to feeding on land, because the density of water is about the same as that of the prey, so the prey tends to be pushed away when the mouth is closed. This problem was first identifi ...

ers; also, durophagous

Durophagy is the eating behavior of animals that consume hard-shelled or exoskeleton-bearing organisms, such as corals, shelled mollusks, or crabs. It is mostly used to describe fish, but is also used when describing reptiles, including fossil t ...

forms are known. Towards the end of the Late Triassic, a decline of variability seems to have occurred. The giant species seemed to have disappeared at the end of the Norian. Rhaetian

The Rhaetian is the latest age (geology), age of the Triassic period (geology), Period (in geochronology) or the uppermost stage (stratigraphy), stage of the Triassic system (stratigraphy), System (in chronostratigraphy). It was preceded by the N ...

(latest Triassic) ichthyosaurs are known from England, and these are very similar to those of the Early Jurassic

The Early Jurassic Epoch (geology), Epoch (in chronostratigraphy corresponding to the Lower Jurassic series (stratigraphy), Series) is the earliest of three epochs of the Jurassic Period. The Early Jurassic starts immediately after the Triassic� ...

. A possible explanation is an increased competition by shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch cartilaginous fish characterized by a ribless endoskeleton, dermal denticles, five to seven gill slits on each side, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the ...

s, Teleost

Teleostei (; Ancient Greek, Greek ''teleios'' "complete" + ''osteon'' "bone"), members of which are known as teleosts (), is, by far, the largest group of ray-finned fishes (class Actinopterygii), with 96% of all neontology, extant species of f ...

ei, and the first Plesiosauria

The Plesiosauria or plesiosaurs are an order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared in the latest Triassic Period, possibly in the Rhaetian stage, about 203 million year ...

. Like the dinosaurs, the ichthyosaurs and their contemporaries, the plesiosaurs, survived the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event

The Triassic–Jurassic (Tr-J) extinction event (TJME), often called the end-Triassic extinction, marks the boundary between the Triassic and Jurassic periods, . It represents one of five major extinction events during the Phanerozoic, profoundly ...

, and quickly diversified again to fill the vacant ecological niches of the early Jurassic.

Jurassic

During the Early Jurassic, the ichthyosaurs still showed a large variety of species, ranging from in length. Many well-preserved specimens from England and Germany date to this time and well-known genera include ''

During the Early Jurassic, the ichthyosaurs still showed a large variety of species, ranging from in length. Many well-preserved specimens from England and Germany date to this time and well-known genera include ''Eurhinosaurus

''Eurhinosaurus'' (Greek for 'well-nosed lizard'- eu meaning 'well or good', rhino meaning 'nose' and sauros meaning 'lizard') is an extinct genus of ichthyosaur from the Early Jurassic (Toarcian), ranging between 183 and 175 million years. Fossi ...

'', ''Ichthyosaurus

''Ichthyosaurus'' (derived from Greek () meaning 'fish' and () meaning 'lizard') is a genus of ichthyosaurs from the Early Jurassic (Hettangian - Pliensbachian) of Europe (Belgium, England, Germany and Portugal). Some specimens of the ichthy ...

'', ''Leptonectes

''Leptonectes'' is a genus of ichthyosaur that lived in the Late Triassic to Early Jurassic (Rhaetian - Pliensbachian). Fossils have been found in Belgium, Germany, Spain and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and ...

'', ''Stenopterygius

''Stenopterygius'' is an extinct genus of thunnosaur ichthyosaur known from Europe (England, France, Germany, Luxembourg and Switzerland).

History

''Stenopterygius'' was originally named by Quenstedt in 1856 as a species of ''Ichthyosaurus'', '' ...

'', and the large predator ''Temnodontosaurus

''Temnodontosaurus'' (meaning "cutting-tooth lizard") is an extinct genus of large ichthyosaurs that lived during the Lower Jurassic in what is now Europe and possibly Chile. The first known fossil is a specimen consisting of a complete skull a ...

.'' More basal parvipelvians like ''Suevoleviathan

''Suevoleviathan'' is an extinct genus of primitive ichthyosaur found in the Early Jurassic (Toarcian) of Holzmaden, Germany.

Taxonomy

The genus was named in 1998 by Michael Maisch for ''Leptopterygius disinteger'' and ''Ichthyosaurus integer' ...

'' were also present. The general morphological variability had been strongly reduced, however. Giant forms, suction feeders and durophagous species were absent. Many of these genera possessed streamlined, dolphin-like thunniform

Fish locomotion is the various types of animal locomotion used by fish, principally by swimming. This is achieved in different groups of fish by a variety of mechanisms of propulsion, most often by wave-like lateral flexions of the fish's body a ...

bodies, although more basal clades like Eurhinosauria

Leptonectidae is a family of ichthyosaurs

Ichthyosauria is an taxonomy (biology), order of large extinction, extinct marine reptiles sometimes referred to as "ichthyosaurs", although the term is also used for wider clades in which the order res ...

, which include ''Leptonectes'' and ''Eurhinosaurus'', had longer bodies and long snouts.

Few ichthyosaur fossils are known from the Middle Jurassic. This might be a result of the poor fossil record

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

in general of this epoch. The strata of the Late Jurassic seem to indicate that a further decrease in diversity had taken place. From the Middle Jurassic onwards, almost all ichthyosaurs belonged to the thunnosaurian clade Ophthalmosauridae

Ophthalmosauridae is an extinct family of thunnosaur ichthyosaurs from the Middle Jurassic to the early Late Cretaceous (Bajocian - Cenomanian) worldwide. Almost all ichthyosaurs from the Middle Jurassic onwards belong to the family, until the ex ...

. Represented by the ''Ophthalmosaurus

''Ophthalmosaurus'' (Greek ὀφθάλμος ''ophthalmos'' 'eye' and σαῦρος ''sauros'' 'lizard') is a genus of ichthyosaur known from the Middle-Late Jurassic. Possible remains from the earliest Cretaceous, around 145 million years ago, a ...

'' and related genera, they were very similar in general build to ''Ichthyosaurus''. The eyes of ''Ophthalmosaurus'' were huge, and these animals likely hunted in dim and deep water. However, new finds from the Cretaceous indicate that ichthyosaur diversity in the Late Jurassic must have been underestimated.

Cretaceous

Traditionally, ichthyosaurs were seen as decreasing in diversity even further with the

Traditionally, ichthyosaurs were seen as decreasing in diversity even further with the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

, though they had a worldwide distribution. All fossils from this period were referred to a single genus: ''Platypterygius

''Platypterygius'' is a historically paraphyletic genus of platypterygiine ichthyosaur from the Cretaceous period. It was historically used as a wastebasket taxon, and most species within ''Platypterygius'' likely are undiagnostic at the genus or ...

''. This last ichthyosaur genus was thought to have become extinct early in the late Cretaceous, during the Cenomanian

The Cenomanian is, in the International Commission on Stratigraphy's (ICS) geological timescale, the oldest or earliest age (geology), age of the Late Cretaceous epoch (geology), Epoch or the lowest stage (stratigraphy), stage of the Upper Cretace ...

about 95 million years ago, much earlier than other large Mesozoic reptile groups that survived until the very end of the Cretaceous. Two major explanations have been proposed for this extinction including either chance or competition from other large marine predators such as plesiosaur

The Plesiosauria or plesiosaurs are an Order (biology), order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared in the latest Triassic Period (geology), Period, possibly in the Rhaetian st ...

s. The overspecialisation of ichthyosaurs may be a contributing factor to their extinction, possibly being unable to 'keep up' with fast teleost

Teleostei (; Ancient Greek, Greek ''teleios'' "complete" + ''osteon'' "bone"), members of which are known as teleosts (), is, by far, the largest group of ray-finned fishes (class Actinopterygii), with 96% of all neontology, extant species of f ...

fish, which had become dominant at this time, against which the sit-and-wait ambush strategies of the mosasaur

Mosasaurs (from Latin ''Mosa'' meaning the 'Meuse', and Ancient Greek, Greek ' meaning 'lizard') are an extinct group of large aquatic reptiles within the family Mosasauridae that lived during the Late Cretaceous. Their first fossil remains wer ...

oids proved superior. This model thus emphasised evolutionary stagnation, the only innovation shown by ''Platypterygius