Iberian Revolt on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Iberian revolt (197–195 BC) was a rebellion of the

The

The

The

The

Given the limited success of the

Given the limited success of the

Marcus Porcius Cato ''the Elder'' was endowed by the

Marcus Porcius Cato ''the Elder'' was endowed by the

At this time three legates

At this time three legates

When Cato considered that his soldiers were ready to face the

When Cato considered that his soldiers were ready to face the

In

In

The treatment of the conflict has been greater and more exhaustive than that of other similar campaigns in Hispania. Surely the character of

The treatment of the conflict has been greater and more exhaustive than that of other similar campaigns in Hispania. Surely the character of

The biography of

The biography of

Iberian

Iberian refers to Iberia. Most commonly Iberian refers to:

*Someone or something originating in the Iberian Peninsula, namely from Spain, Portugal, Gibraltar and Andorra.

The term ''Iberian'' is also used to refer to anything pertaining to the fo ...

peoples of the provinces

A province is an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman , which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions outside Italy. The term ''provi ...

Citerior and Ulterior, created shortly before in Hispania

Hispania was the Ancient Rome, Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two Roman province, provinces: Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior. During the Principate, Hispania Ulterior was divide ...

by the Roman state to regularize the government of these territories, against that Roman domination in the 2nd century BC.

From 197 BC, the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

divided its conquests in the south and east of the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

into two provinces: Hispania Citerior

Hispania Citerior (English: "Hither Iberia", or "Nearer Iberia") was a Roman province in Hispania during the Roman Republic. It was on the eastern coast of Iberia down to the town of Cartago Nova, today's Cartagena in the autonomous community of ...

and Hispania Ulterior

Hispania Ulterior (English: "Further Hispania", or occasionally "Thither Hispania") was a Roman province located in Hispania (on the Iberian Peninsula) during the Roman Republic, roughly located in Baetica and in the Guadalquivir valley of moder ...

, each governed by a praetor

''Praetor'' ( , ), also ''pretor'', was the title granted by the government of ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected ''magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to disch ...

. Although several causes have been put forward as possibly responsible for the conflict, the most widely accepted is that derived from the administrative and fiscal changes produced by the transformation of the territory into two provinces.

The revolt having begun in the Ulterior province, Rome sent the praetors Gaius Sempronius Tuditanus Gaius Sempronius Tuditanus was a politician and historian of the Roman Republic. He was consul in 129 BC.

Biography Early life

Gaius Sempronius Tuditanus was a member of the plebeian gens Sempronia. His father had the same name and was senator ...

(XXXII, 27, 7; XXXII, 28, 2 and 11) (39) to the Citerior province and Marcus Helvius Blasio, (39–41) to Ulterior. Shortly before the rebellion spread to the Citerior province, Gaius Sempronius Tuditanus was killed in action. However, Marcus Helvius Blasion, who upon arriving in his province ran headlong into the revolt, won an important victory over the Celtiberians

The Celtiberians were a group of Celts and Celticized peoples inhabiting an area in the central-northeastern Iberian Peninsula during the final centuries BC. They were explicitly mentioned as being Celts by several classic authors (e.g. Strabo) ...

at the Battle of Iliturgi. The situation was still far from under control, and Rome sent the praetor

''Praetor'' ( , ), also ''pretor'', was the title granted by the government of ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected ''magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to disch ...

es Quintus Minucius Thermus and Quintus Fabius Buteo in a further attempt to settle the conflict. However, although the latter achieved some victories, such as at the Battle of Turda

The Battle of Turda lasted from 5 September to 8 October 1944, in the area around Turda, Kingdom of Romania, as part of the wider Battle of Romania. Troops from the Hungarian 2nd Army and the German 8th Army fought a defensive action against ...

, where Quintus Minucius even managed to capture the Hispanic general Besadino, (XXXIII, 44, 4–5) they also failed to fully resolve the situation.

It was then that Rome had to send in 195 BC. the consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states thro ...

Marcus Porcius Cato Marcus Porcius Cato can refer to:

*Cato the Elder (consul 195 BC; called "Censorinus"), politician renowned for austerity and author

* Cato the Younger (praetor 54 BC; called " Uticensis"), opponent of Caesar

*Marcus Porcius Cato (consul ...

in command of a consular army to suppress the revolt, who, when he arrived in Hispania

Hispania was the Ancient Rome, Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two Roman province, provinces: Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior. During the Principate, Hispania Ulterior was divide ...

found the entire Citerior province in revolt, with Roman forces controlling only a few fortified cities. Cato established an alliance with Bilistages, king of the Ilergetes

The Ilergetes were an ancient Iberian (Pre- Roman) people of the Iberian Peninsula (the Roman Hispania) who dwelt in the plains area of the rivers Segre and Cinca towards Iberus (Ebro) river, and in and around Ilerda/Iltrida, present-day Lleida ...

, and had also the support of Publius Manlius, newly appointed praetor of Hispania Citerior and sent as assistant consul. Cato headed for the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

, disembarked at Rhode and put down the rebellion of the Hispanics occupying the square. He then moved with his army to Emporion, where the greatest battle of the contest would be fought, against an autochthonous army vastly superior in numbers. After a long and difficult battle, the consul achieved total victory, (XXXIV) managing to inflict 40 000 casualties on the enemy ranks. After Cato's great victory in this decisive battle, which had decimated the Hispanic forces, the Citerior province fell back under Roman control. (XXXIV, 16, 6–7)

On the other hand, the Ulterior province remained uncontrolled, and the consul had to head towards Turdetania

Baeturia, Beturia, or Turdetania was an extensive ancient territory in the southern part of the Iberian Peninsula (in modern Spain) situated between the middle and lower courses of the Guadiana and the Guadalquivir rivers. From the Second Iron Ag ...

to support the praetors Publius Manlius and Appius Claudius Nero. Cato tried to establish an alliance with the Celtiberians

The Celtiberians were a group of Celts and Celticized peoples inhabiting an area in the central-northeastern Iberian Peninsula during the final centuries BC. They were explicitly mentioned as being Celts by several classic authors (e.g. Strabo) ...

, who acted as mercenaries

A mercenary is a private individual who joins an War, armed conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any other official military. Mercenaries fight for money or other forms of payment rath ...

paid by the Turdetani

The Turdetani were an ancient pre-Roman peoples of the Iberian Peninsula, pre-Roman people of the Iberian Peninsula, living in the valley of the Guadalquivir (the river that the Turdetani called by two names: ''Kertis'' and ''Rérkēs'' (Ῥέ� ...

and whose services he needed, but failed to convince them. After a show of force, passing with the Roman Legion

The Roman legion (, ) was the largest military List of military legions, unit of the Roman army, composed of Roman citizenship, Roman citizens serving as legionary, legionaries. During the Roman Republic the manipular legion comprised 4,200 i ...

s through Celtiberia

The Celtiberians were a group of Celts and Celticized peoples inhabiting an area in the central-northeastern Iberian Peninsula during the final centuries BC. They were explicitly mentioned as being Celts by several classic authors (e.g. Strabo) ...

n territory, he convinced them to return to their lands. The submission of the autochthonous army was only an appearance, and when rumor spread of Cato's departure for Rome, the rebellion resumed. Cato had to act again with decision and effectiveness, defeating the rebels definitively in the battle of Bergium. Finally, Cato sold the captives into slavery and the autochthonous of the province were disarmed.

Historical background

Second Punic War

The Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) was the second of Punic Wars, three wars fought between Ancient Carthage, Carthage and Roman Republic, Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean Basin, Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. For ...

was in its final stretch. The Carthaginian The term Carthaginian ( ) usually refers to the civilisation of ancient Carthage.

It may also refer to:

* Punic people, the Semitic-speaking people of Carthage

* Punic language

The Punic language, also called Phoenicio-Punic or Carthaginian, i ...

generals Magon Barca and Hasdrubal Gisco

Hasdrubal Gisco (died 202BC), a latinization of the name ʿAzrubaʿal son of Gersakkun (),. was a Carthaginian general who fought against Rome in Iberia (Hispania) and North Africa during the Second Punic War.

Biography

Hasdrubal Gisco was sen ...

had retreated towards Gades, which allowed Scipio Africanus

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus (, , ; 236/235–) was a Roman general and statesman who was one of the main architects of Rome's victory against Ancient Carthage, Carthage in the Second Punic War. Often regarded as one of the greatest milit ...

to take over the entire southern Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

. Scipio then crossed into Africa to hold a meeting with the Numidian

Numidia was the ancient kingdom of the Numidians in northwest Africa, initially comprising the territory that now makes up Algeria, but later expanding across what is today known as Tunisia and Libya. The polity was originally divided between ...

king Syphax

Syphax (, ''Sýphax''; , ) was a king of the Masaesyli tribe of western Numidia (present-day Algeria) during the last quarter of the 3rd century BC. His story is told in Livy's ''Ab Urbe Condita'' (written c. 27–25 BC).

, whom he had previously encountered in Hispania

Hispania was the Ancient Rome, Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two Roman province, provinces: Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior. During the Principate, Hispania Ulterior was divide ...

, with the intention of forging an alliance.

Shortly thereafter, Scipio became seriously ill and seizing the opportunity, 8000 Roman soldiers

This is a list of Roman army units and bureaucrats.

*'' Accensus'' – Light infantry men in the armies of the early Roman Republic, made up of the poorest men of the army.

*''Actuarius'' – A soldier charged with distributing pay and provisions ...

, who were dissatisfied at having received lower pay than usual, and, moreover, lacked authorization to plunder enemy towns, revolted and started a mutiny; this mutiny was the perfect occasion seized by the Ilergetes

The Ilergetes were an ancient Iberian (Pre- Roman) people of the Iberian Peninsula (the Roman Hispania) who dwelt in the plains area of the rivers Segre and Cinca towards Iberus (Ebro) river, and in and around Ilerda/Iltrida, present-day Lleida ...

and other Iberian

Iberian refers to Iberia. Most commonly Iberian refers to:

*Someone or something originating in the Iberian Peninsula, namely from Spain, Portugal, Gibraltar and Andorra.

The term ''Iberian'' is also used to refer to anything pertaining to the fo ...

peoples to revolt, led by the leaders Indibilis (of the Ilergetes) and Mandonius (of the Ausetani

The Ausetani were an ancient Iberian (pre-Roman) people of the Iberian Peninsula (the Roman Hispania). They are believed to have spoken the Iberian language. They lived in the eponymous region of Ausona and gave their name to the Roman city of '' ...

), a rebellion directed above all against the proconsul

A proconsul was an official of ancient Rome who acted on behalf of a Roman consul, consul. A proconsul was typically a former consul. The term is also used in recent history for officials with delegated authority.

In the Roman Republic, military ...

s Lucius Cornelius Lentulus and Lucius Manlius Acidinus. Lucius Manlius succeeded in defeating the Ausetani

The Ausetani were an ancient Iberian (pre-Roman) people of the Iberian Peninsula (the Roman Hispania). They are believed to have spoken the Iberian language. They lived in the eponymous region of Ausona and gave their name to the Roman city of '' ...

and the Ilergetes

The Ilergetes were an ancient Iberian (Pre- Roman) people of the Iberian Peninsula (the Roman Hispania) who dwelt in the plains area of the rivers Segre and Cinca towards Iberus (Ebro) river, and in and around Ilerda/Iltrida, present-day Lleida ...

, who had rebelled against the Republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

in the absence of Scipio Africanus. He returned to Rome in 199 BC, but was not granted the ovation

The ovation ( from ''ovare'': to rejoice) was a lesser form of the Roman triumph. Ovations were granted when war was not declared between enemies on the level of nations or states; when an enemy was considered basely inferior (e.g., slaves, pira ...

that the senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

had awarded him because of opposition from the tribune of the plebs

Tribune of the plebs, tribune of the people or plebeian tribune () was the first office of the Roman Republic, Roman state that was open to the plebs, plebeians, and was, throughout the history of the Republic, the most important check on the pow ...

Publius Porcius Laeca. Publius Scipio succeeded in putting down the mutiny and brought the Iberian revolt to a bloody end. Mandonius was captured and executed (205 BC), while Indibilis managed to escape.

Magon Barca and Hasdrubal Gisco

Hasdrubal Gisco (died 202BC), a latinization of the name ʿAzrubaʿal son of Gersakkun (),. was a Carthaginian general who fought against Rome in Iberia (Hispania) and North Africa during the Second Punic War.

Biography

Hasdrubal Gisco was sen ...

left Gades with all their ships and troops to go to the Italian Peninsula in support of Hannibal

Hannibal (; ; 247 – between 183 and 181 BC) was a Punic people, Carthaginian general and statesman who commanded the forces of Ancient Carthage, Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic during the Second Punic War.

Hannibal's fat ...

, and after the departure of these forces, Rome was master of all southern Hispania. Rome now dominated from the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees are a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. They extend nearly from their union with the Cantabrian Mountains to Cap de Creus on the Mediterranean coast, reaching a maximum elevation of at the peak of Aneto. ...

to the Algarve

The Algarve (, , ) is the southernmost NUTS statistical regions of Portugal, NUTS II region of continental Portugal. It has an area of with 467,495 permanent inhabitants and incorporates 16 municipalities (concelho, ''concelhos'' or ''município ...

, following the coast. The territory controlled by the Roman armies reached as far as Huesca

Huesca (; ) is a city in north-eastern Spain, within the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Aragon. It was the capital of the Kingdom of Aragon between 1096 and 1118. It is also the capital of the Spanish Huesca (province), ...

, and from there southward to the Ebro

The Ebro (Spanish and Basque ; , , ) is a river of the north and northeast of the Iberian Peninsula, in Spain. It rises in Cantabria and flows , almost entirely in an east-southeast direction. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea, forming a de ...

and eastward to the sea. The victory of the Republic of Rome over Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

in the Second Punic War

The Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) was the second of Punic Wars, three wars fought between Ancient Carthage, Carthage and Roman Republic, Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean Basin, Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. For ...

left Hispania

Hispania was the Ancient Rome, Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two Roman province, provinces: Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior. During the Principate, Hispania Ulterior was divide ...

definitively in their hands.

When Scipio Africanus

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus (, , ; 236/235–) was a Roman general and statesman who was one of the main architects of Rome's victory against Ancient Carthage, Carthage in the Second Punic War. Often regarded as one of the greatest milit ...

left after his Hispanic campaigns, the Iberian chiefs who had supported him, and who still enjoyed a certain political structure and capacity to react, considered that they were only linked by a personal relationship with their ''rex'' Scipio and had no duty to the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

, so they took up arms against the latter. Other causes for the uprising have been proposed, however, such as the death of Indibilis and Mandonius at the hands of the Romans; or the most widely accepted, the high tributes that the Hispaniids had to pay to Rome, especially after the transformation of the territory into two provinces.

Forces in combat

First confrontations

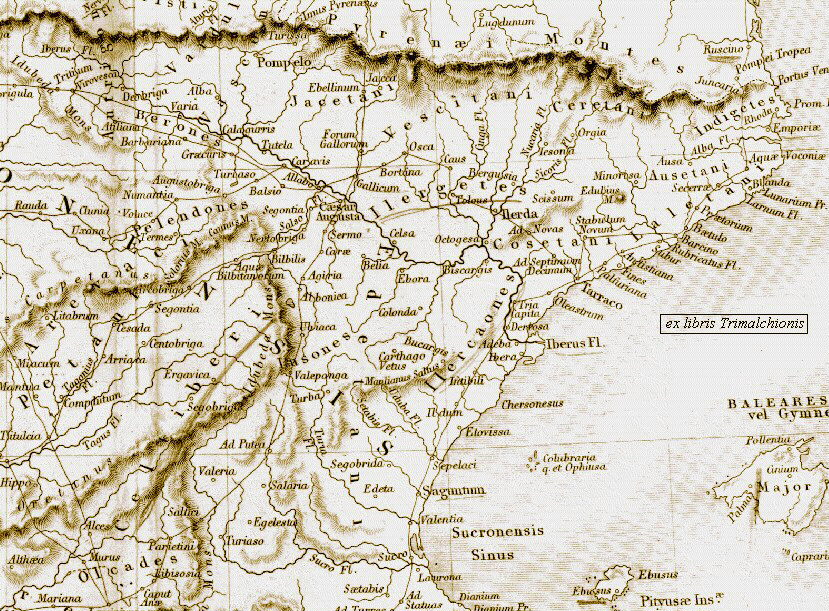

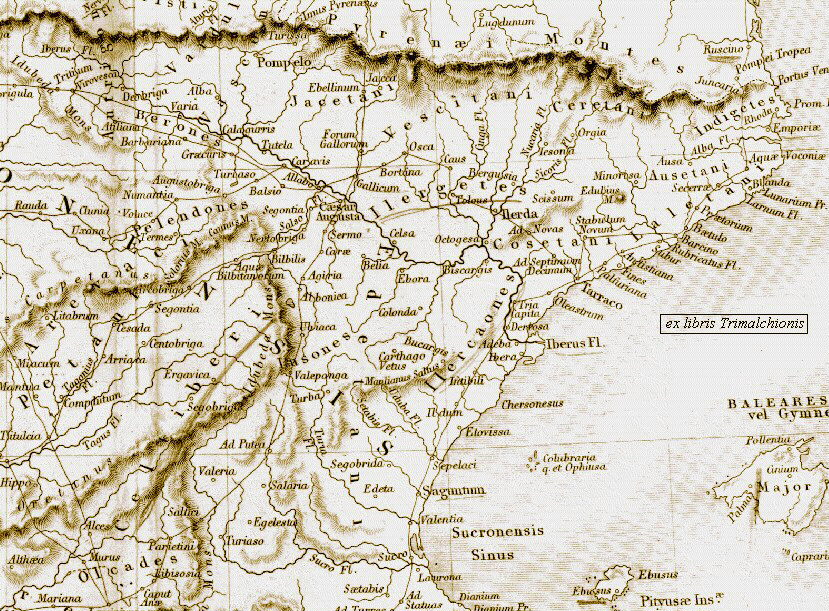

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

divided in 197 BC. its conquests in the south and east of the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

into two provinces: Hispania Citerior

Hispania Citerior (English: "Hither Iberia", or "Nearer Iberia") was a Roman province in Hispania during the Roman Republic. It was on the eastern coast of Iberia down to the town of Cartago Nova, today's Cartagena in the autonomous community of ...

(east coast, from the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees are a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. They extend nearly from their union with the Cantabrian Mountains to Cap de Creus on the Mediterranean coast, reaching a maximum elevation of at the peak of Aneto. ...

to Cartagena), later called Tarraconensis

Hispania Tarraconensis was one of three Roman provinces in Hispania. It encompassed much of the northern, eastern and central territories of modern Spain along with modern northern Portugal. Southern Spain, the region now called Andalusia, was t ...

with capital in Tarraco

Tarraco is the ancient name of the current city of Tarragona (Catalonia, Spain). It was the oldest Roman settlement on the Iberian Peninsula. It became the capital of Hispania Tarraconensis following the latter's creation during the Roman Empire ...

, and Hispania Ulterior

Hispania Ulterior (English: "Further Hispania", or occasionally "Thither Hispania") was a Roman province located in Hispania (on the Iberian Peninsula) during the Roman Republic, roughly located in Baetica and in the Guadalquivir valley of moder ...

(approximately present-day Andalusia

Andalusia ( , ; , ) is the southernmost autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Peninsular Spain, located in the south of the Iberian Peninsula, in southwestern Europe. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomou ...

), with capital in Corduba, each governed by a praetor

''Praetor'' ( , ), also ''pretor'', was the title granted by the government of ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected ''magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to disch ...

. The transformation of the territory into two provinces caused important administrative and fiscal changes, and the imposition of the '' stipendium'' was not accepted by the local tribes, so that in 197 BC, just after the Second Macedonian War

The Second Macedonian War (200–197 BC) was fought between Macedon, led by Philip V of Macedon, and Rome, allied with Pergamon and Rhodes. Philip was defeated and was forced to abandon all possessions in southern Greece, Thrace and Asia Minor. ...

was over, a great revolt broke out throughout the conquered area in Hispania because of the republican spoliation.

The new provinces needed rulers, so the Republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

sent the praetors Gaius Sempronius Tuditanus Gaius Sempronius Tuditanus was a politician and historian of the Roman Republic. He was consul in 129 BC.

Biography Early life

Gaius Sempronius Tuditanus was a member of the plebeian gens Sempronia. His father had the same name and was senator ...

to Hispania Citerior

Hispania Citerior (English: "Hither Iberia", or "Nearer Iberia") was a Roman province in Hispania during the Roman Republic. It was on the eastern coast of Iberia down to the town of Cartago Nova, today's Cartagena in the autonomous community of ...

and Marcus Helvius Blasion to Hispania Ulterior with a total of 8000 infants and 800 horsemen to discharge veterans, and the order to delimit the borders of the provinces. When Marcus Helvius arrived in his corresponding province he encountered a large revolt, whereupon he informed the senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

. Numerous local chiefs had revolted in Hispania Ulterior

Hispania Ulterior (English: "Further Hispania", or occasionally "Thither Hispania") was a Roman province located in Hispania (on the Iberian Peninsula) during the Roman Republic, roughly located in Baetica and in the Guadalquivir valley of moder ...

, among them the regula Culcas at the head of the armies of 17 cities, and the Regulus Luxinio, commanding the forces of the cities of Carmo and Bardo. The cities of Malaca, Sexi and all of Baeturia had also joined the revolt.

Shortly thereafter, the war, which had begun in the Ulterior province, spread also to Citerior, in which its praetor

''Praetor'' ( , ), also ''pretor'', was the title granted by the government of ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected ''magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to disch ...

, Gaius Sempronius Tuditanus, had died of wounds suffered in battle, along with many soldiers, at the end of 197 BC; and the province was left without a praetor until the following year. It is likely that Marcus Helvius himself, praetor of the Ulterior, also assumed control of the Citerior until the arrival of Sempronius' successor.

Quintus Minucius Thermus and Quintus Fabius Buteo were the praetor

''Praetor'' ( , ), also ''pretor'', was the title granted by the government of ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected ''magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to disch ...

es elected in 196 BC to take charge of Hispania Citerior

Hispania Citerior (English: "Hither Iberia", or "Nearer Iberia") was a Roman province in Hispania during the Roman Republic. It was on the eastern coast of Iberia down to the town of Cartago Nova, today's Cartagena in the autonomous community of ...

and Hispania Ulterior respectively. They were given reinforcements consisting of two legions, 4000 infantry and 300 horsemen, (XXXIII, 26, 1–5) and ordered to leave in haste for the provinces to continue the war. Quintus Minucius Thermus defeated the insurgent Budar and Besadines at an undetermined place called Turda

Turda (; , ; ; ) is a Municipiu, city in Cluj County, Transylvania, Romania. It is located in the southeastern part of the county, from the county seat, Cluj-Napoca, to which it is connected by the European route E81, and from nearby Câmpia ...

, caused 12 000 casualties in the Hispanic ranks, and trapped general Besadines. Quintus Minucius consequently received the honor of ''triumphus'' upon his return to Rome in 195 BC

Roman victory at Iliturgi

Given the limited success of the

Given the limited success of the praetor

''Praetor'' ( , ), also ''pretor'', was the title granted by the government of ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected ''magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to disch ...

of 196 BC in Hispania Citerior

Hispania Citerior (English: "Hither Iberia", or "Nearer Iberia") was a Roman province in Hispania during the Roman Republic. It was on the eastern coast of Iberia down to the town of Cartago Nova, today's Cartagena in the autonomous community of ...

, the Roman Senate

The Roman Senate () was the highest and constituting assembly of ancient Rome and its aristocracy. With different powers throughout its existence it lasted from the first days of the city of Rome (traditionally founded in 753 BC) as the Sena ...

had declared it a "consular province", since the intervention of a consular army was necessary to control the situation. (XXXIII, 43, 1–3) Elected consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states thro ...

in 195 BC together with his friend Lucius Valerius Flaccus it fell to Marcus Porcius Cato, ''the Elder'' by lot to take charge of Hispania Citerior. Also elected were the praetor

''Praetor'' ( , ), also ''pretor'', was the title granted by the government of ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected ''magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to disch ...

es for Hispania Ulterior

Hispania Ulterior (English: "Further Hispania", or occasionally "Thither Hispania") was a Roman province located in Hispania (on the Iberian Peninsula) during the Roman Republic, roughly located in Baetica and in the Guadalquivir valley of moder ...

and Hispania Citerior, Appius Claudius Nero and Publius Manlius, respectively, with their allotted forces, although, due to the emergency situation, they were allowed 2000 more infantrymen and 200 more horsemen, to be added to the legions their predecessors had disposed of. The consul Marcus Porcius Cato, who had been unable to prevent the annulment of the Oppian Law, embarked with his troops for Hispania

Hispania was the Ancient Rome, Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two Roman province, provinces: Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior. During the Principate, Hispania Ulterior was divide ...

to take charge of the Citerior province with Publius Manlius as assistant, leaving the Ulterior to Appius Claudius.

Marcus Helvius Blasion, although he had already handed over the government of the province to his successor, had to stay in Hispania

Hispania was the Ancient Rome, Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two Roman province, provinces: Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior. During the Principate, Hispania Ulterior was divide ...

due to a long illness. Now recovered, with a guard of 6000 soldiers posted for him by the praetor Appius Claudius Nero, he was attacked by 20 000 Celtiberians

The Celtiberians were a group of Celts and Celticized peoples inhabiting an area in the central-northeastern Iberian Peninsula during the final centuries BC. They were explicitly mentioned as being Celts by several classic authors (e.g. Strabo) ...

near Iliturgi. Marcus Helvius managed to repel the attackers, defeated them, and inflicted about 12 000 casualties on them. Iliturgi was occupied by the Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

, and this victory earned Marcus Helvius Blasion an ''ovatio'' granted by the senate in 195 BC; however, he was ineligible for the ''triumphus'', having fought in a province that belonged to another praetor. Upon his arrival in Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

Marcus Helvius made delivery to the Republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

of 14 732 pounds of uncoined silver, 17 023 coined and 119 439 of oscensian silver. Marcus Helvius was thus arriving in Rome two years later than planned. Such quantities of wealth taken from Hispania give an idea of the unrest of the autochthonous peoples, the probable cause of the uprising.

Landing of Cato in Hispania

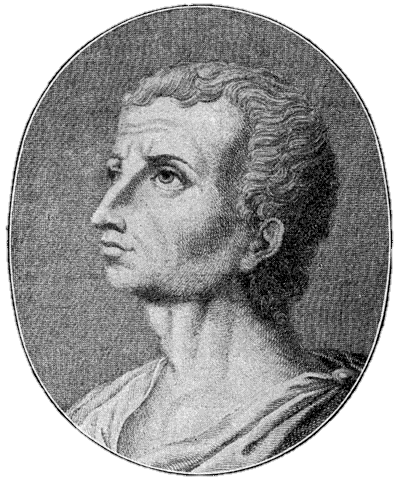

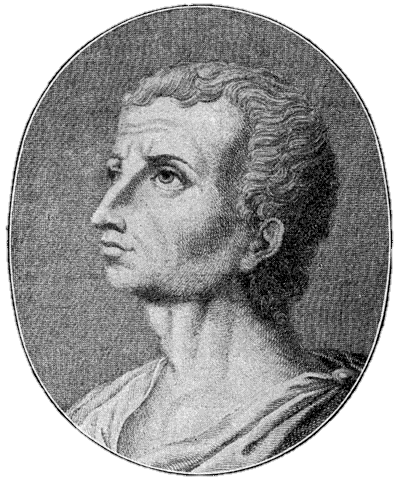

Marcus Porcius Cato ''the Elder'' was endowed by the

Marcus Porcius Cato ''the Elder'' was endowed by the Roman Senate

The Roman Senate () was the highest and constituting assembly of ancient Rome and its aristocracy. With different powers throughout its existence it lasted from the first days of the city of Rome (traditionally founded in 753 BC) as the Sena ...

with a consular army, composed of two legions, 8000 infantrymen, 15 000 allies and 800 horsemen, plus 20 ships

A ship is a large vessel that travels the world's oceans and other navigable waterways, carrying cargo or passengers, or in support of specialized missions, such as defense, research and fishing. Ships are generally distinguished from boats, ...

for the transport of the troops; to all this were added as reinforcements 2000 infantrymen and 200 horsemen for each of the praetors, making a total of 50 000Götzfriez talks of some 70 000 soldiers — which seems to be excessive if the forces of the units present in Hispania

Hispania was the Ancient Rome, Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two Roman province, provinces: Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior. During the Principate, Hispania Ulterior was divide ...

are added up one by one. men among the three armies. Cato embarked his army on 25 ships, 5 of them with allied troops, departed from Portus Lunae ( Luni, Italy) and skirted the Gulf of Leon to reach Hispania, the northern part of the Citerior province. The Roman army disembarked at Rhode, in the Gulf of Roses, around June 195 BC, with its 25 quinquereme

From the 4th century BC on, new types of oared warships appeared in the Mediterranean Sea, superseding the trireme and transforming naval warfare. Ships became increasingly large and heavy, including some of the largest wooden ships hitherto con ...

s, to defeat an autochthonous army of the area. The consul, who on his arrival in Hispania found himself in a complicated military situation, only personally carried about 20 000 men, since the rest were carried by the praetors; so that with these meager forces Cato faced the battle.

Siege of the citadel

TheIberian

Iberian refers to Iberia. Most commonly Iberian refers to:

*Someone or something originating in the Iberian Peninsula, namely from Spain, Portugal, Gibraltar and Andorra.

The term ''Iberian'' is also used to refer to anything pertaining to the fo ...

settlements were usually built on hills, in strategic locations, controlling the passageways, which gave them an important advantage over enemies; they were usually surrounded by large walls, on which watchtowers and the gates of the city were arranged.

The square fell definitively in July 195 BC. Cato sacked the city and then fought against the Indians and put down the resistance of the Iberian garrison located on Puig Rom, or Rhode acropolis, surely the Citadel of Roses.

Arrival of the Roman army at Emporion

TheRoman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

army then landed at Emporion, and Cato the Elder

Marcus Porcius Cato (, ; 234–149 BC), also known as Cato the Censor (), the Elder and the Wise, was a Roman soldier, Roman Senate, senator, and Roman historiography, historian known for his conservatism and opposition to Hellenization. He wa ...

had the ships return to Massalia

Massalia (; ) was an ancient Greek colonisation, Greek colony (''apoikia'') on the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean coast, east of the Rhône. Settled by the Ionians from Phocaea in 600 BC, this ''apoikia'' grew up rapidly, and its population se ...

with merchants to force his army into the fight: (40)

(In English: "War feeds itself."), a phrase uttered by Cato during the contest when he refused to buy additional supplies for his army.

Titus Livius

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding i ...

describes what the Roman army finds upon its arrival at Emporion:

Marcus Porcius Cato Marcus Porcius Cato can refer to:

*Cato the Elder (consul 195 BC; called "Censorinus"), politician renowned for austerity and author

* Cato the Younger (praetor 54 BC; called " Uticensis"), opponent of Caesar

*Marcus Porcius Cato (consul ...

would start in Emporion, an almost island surrounded by marshes, where the Greek city and the Iberian city coexisted separated by a wall, a tough confrontation against a huge Hispanic army. Upon their arrival in the city, Cato and his troops received a warm welcome from the Greek inhabitants.

Encounter with the Ilergetes allies

At this time three legates

At this time three legates ilergetes

The Ilergetes were an ancient Iberian (Pre- Roman) people of the Iberian Peninsula (the Roman Hispania) who dwelt in the plains area of the rivers Segre and Cinca towards Iberus (Ebro) river, and in and around Ilerda/Iltrida, present-day Lleida ...

arrived at the Roman camp, one of whom was the son of king Bilistages. These exposed to the consul that the Ilergetes cities were under attack, and that if they did not receive immediate help they would not be able to withstand the siege of their strongholds, for which they asked him for at least 3000 men. Cato replied that he understood the danger and concern of the Ilergetes, but that he had to fight a battle against a large army and could not spare any soldiers. The Ilergetes pleaded with him for help since they had no allies besides Rome, as they were the only ones who had remained loyal to the Republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

and the rest of the autochthonous peoples were now their enemies. /XXXIV, 11, 2–8; 12, 1–8) The legates left the camp disappointed by the Romans' response. The consul did not want to leave the allies to their fate, but neither could he afford to leave soldiers behind, so he hatched a plan to give the Ilergetes hope so that they would fight with higher morale. The next morning Cato called the legates and told them that he would help them; he ordered a third of the soldiers to prepare to go out to the aid of the Ilergetes in two days, and he did the same with the ships. The legates left the camp after seeing the soldiers embark. After a prudent time, Cato ordered the embarked soldiers to leave the ships. (XXXIV, 13, 1–3)

Cato remained a few days on the outskirts of the city analyzing the enemy troops and training his soldiers. At this time he visited the camp Marcus Helvius,According to Martínez Gázquez, the encounter could not have taken place at this time, but must have been later. — making a stop on his return journey to Rome, protected by 6000 soldiers on loan from the praetor Appius Claudius, after having won at Iliturgi. Since the area was now safe, Helvius returned the men to Appius Claudius and embarked for Rome.

Preparations for the decisive battle

autochthonous

Autochthon, autochthons or autochthonous may refer to:

Nature

* Autochthon (geology), a sediment or rock that can be found at its site of formation or deposition

* Autochthon (nature), or landrace, an indigenous animal or plant

* Autochthonou ...

in the open field, he ordered his troops to head for ''castra hiberna'', a second camp

Camp may refer to:

Areas of confinement, imprisonment, or for execution

* Concentration camp, an internment camp for political prisoners or politically targeted demographics, such as members of national or minority ethnic groups

* Extermination ...

located 3000 paces from the city on the mainland, in enemy-controlled territory, from where he whipped the rebels at night by burning their fields and plundering their crops and livestock, thus demoralizing their enemies. In this way he trained the soldiers and terrified the enemies, to the point that they dared less and less to leave the city. Moreover, the consul ordered 300 soldiers to abduct a sentry for interrogation.

Cato's army of about 20 000 men initially, to which casualties from the battle of Rhode

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

would have to be subtracted, was vastly outnumbered by the forces of the autochthonous army. The revolted army besieging Emporion, of about 40 000 men, was partially disbanded in the harvest season, moment taken advantage of by Marcus Porcius Cato Marcus Porcius Cato can refer to:

*Cato the Elder (consul 195 BC; called "Censorinus"), politician renowned for austerity and author

* Cato the Younger (praetor 54 BC; called " Uticensis"), opponent of Caesar

*Marcus Porcius Cato (consul ...

to attack the camp. Then the consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states thro ...

addressed his men:

Tactical disposition used by Cato

During the night, Cato took the most advantageous position, (XXXIV, 14, 1) keeping alegion

Legion may refer to:

Military

* Roman legion, the basic military unit of the ancient Roman army

* Aviazione Legionaria, Italian air force during the Spanish Civil War

* A legion is the regional unit of the Italian carabinieri

* Spanish Legion, ...

in reserve, and placing the cavalry (''equites'') at the ends of the line and the infantry in the center; typical disposition of a " maniple army" of the Republican era

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

. The manipuli were organized in three distinct battle lines (in Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, ''triplex acies'') each based on a type of heavy infantry: ''hastati

''Hastati'' (: ''hastatus'') were a class of infantry employed in the Structural history of the Roman military#Manipular legion (315 BC – 107 BC), armies of the early Roman Republic, who originally fought as spearmen and later as swordsmen. Th ...

'', ''princeps

''Princeps'' (plural: ''Principes'') is a Latin word meaning "first in time or order; the first, foremost, chief, the most eminent, distinguished, or noble; the first person". As a title, ''Princeps'' originated in the Roman Republic wherein the ...

'' and ''triarii

''Triarii'' (: ''triarius'') ("the third liners") were one of the elements of the early Roman military manipular legions of the early Roman Republic (509 BC – 107 BC). They were the oldest and among the wealthiest men in the army and could a ...

'': the ''hastati'', infantrymen covered with leather armor, breastplates and helmets, formed in the front line of battle. They carried a wooden shield, reinforced with iron, a sword called ''gladius

''Gladius'' () is a Latin word properly referring to the type of sword that was used by Ancient Rome, ancient Roman foot soldiers starting from the 3rd century BC and until the 3rd century AD. Linguistically, within Latin, the word also came t ...

'' and two throwing spears

A javelin is a light spear designed primarily to be thrown, historically as a ranged weapon. Today, the javelin is predominantly used for sporting purposes such as the javelin throw. The javelin is nearly always thrown by hand, unlike the slin ...

known as ''pila

Pila may refer to:

Architecture

* Pila (architecture), a type of veranda in Sri Lankan farm houses

Places

*Pila, Buenos Aires, a town in Buenos Aires Province, Argentina

*Pila Partido, a country subdivision in Buenos Aires Province, Argentina

*P ...

'' (a heavy ''pilum'' and a smaller javelin). (VI) The ''princeps'', heavy infantrymen, usually formed the second line of soldiers. They were armed and protected in the same way as the ''hastati'', but wore lighter chain mail

Mail (sometimes spelled maille and, since the 18th century, colloquially referred to as chain mail, chainmail or chain-mail) is a type of armour consisting of small metal rings linked together in a pattern to form a mesh. It was in common milita ...

instead of solid armour. In the third line were the ''triarii''. Their weapons and armor were similar to those of the ''princeps'', with the exception that their main weapon was a p''ike'' instead of the two ''pila''. The ''equites'', finally, were placed on both flanks of the battle formation.

The Iberian warriors, besides being superior in numbers, also had effective weapons, such as the ''gladius

''Gladius'' () is a Latin word properly referring to the type of sword that was used by Ancient Rome, ancient Roman foot soldiers starting from the 3rd century BC and until the 3rd century AD. Linguistically, within Latin, the word also came t ...

'', ''falcata

The falcata is a type of sword typical of pre-Roman Iberia. The falcata was used to great effect for warfare in the ancient Iberian Peninsula, and is firmly associated with the southern Iberian tribes, among other ancient peoples of Hispania. ...

'', the ''soliferrum

Soliferrum or Soliferreum (Latin: ''solus'', "only" + ''ferrum'', "Iron") was the Roman name for an ancient Iberian ranged polearm made entirely of iron. The soliferrum was a heavy hand-thrown javelin, designed to be thrown to a distance of up to ...

'' or the ''pugio

The ''pugio'' (; plural: ''pugiones'') was a dagger used by Roman soldiers as a sidearm. It seems likely that the ''pugio'' was intended as an auxiliary weapon, but its exact purpose for the soldier remains unknown though it seems it could have ...

'', a dagger later adopted by Rome for its army.

Several historians have praised the quality of Iberian weapons, such as swords. Dion Cassius

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history of ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

, Polybius

Polybius (; , ; ) was a Greek historian of the middle Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , a universal history documenting the rise of Rome in the Mediterranean in the third and second centuries BC. It covered the period of 264–146 ...

, Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus or Diodorus of Sicily (; 1st century BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek historian from Sicily. He is known for writing the monumental Universal history (genre), universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty ...

, and Titus Livius

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding i ...

in particular make explicit reference to the "Hispanic swords", to which they attribute an unsurpassed quality:

Development of the battle

Early in the morningCato the Elder

Marcus Porcius Cato (, ; 234–149 BC), also known as Cato the Censor (), the Elder and the Wise, was a Roman soldier, Roman Senate, senator, and Roman historiography, historian known for his conservatism and opposition to Hellenization. He wa ...

sent three cohorts to the fence of the Iberian

Iberian refers to Iberia. Most commonly Iberian refers to:

*Someone or something originating in the Iberian Peninsula, namely from Spain, Portugal, Gibraltar and Andorra.

The term ''Iberian'' is also used to refer to anything pertaining to the fo ...

camp, which caused surprise in the Hispanics, who did not expect an attack from behind. The Roman army was then positioned between the enemies and its own camp, a maneuver used by the consul to force his men into the fight, preventing desertions. Cato then ordered the attackers to feign retreat, so that the Iberians pursued them in disorderly fashion, rushing to the outside of the camp fence, at which point the Roman cavalry appeared on their right flank; however the latter was overcome and retreated in fright, and a part of the infantry also, so that Cato had to send two relief cohorts to surround the attackers on the right, which were to arrive before the encounter of the lines of infantry.

The fear provoked in the Hispanic troops by the maneuver matched the initial fear of the Roman cavalry on the right wing. The battle was very evenly matched while fought with throwing weapons; on the right flank the Iberians dominated, while on the left and in the center the Romans were stronger, who also awaited the arrival of two reinforcing cohorts. The battle being evenly matched, in the evening, Cato attacked in wedge

A wedge is a triangle, triangular shaped tool, a portable inclined plane, and one of the six simple machines. It can be used to separate two objects or portions of an object, lift up an object, or hold an object in place. It functions by conver ...

with three reserve cohorts, which had been waiting in the second line, after which a new battle front was established and achieved the disbandment of the Iberians. Cato ordered the second legion

Legion may refer to:

Military

* Roman legion, the basic military unit of the ancient Roman army

* Aviazione Legionaria, Italian air force during the Spanish Civil War

* A legion is the regional unit of the Italian carabinieri

* Spanish Legion, ...

, which had remained in the rear, to form up and attacked the enemy camp by night. The refreshed legion arrived and concentrated at the camp fence, where the Hispanics were fiercely employed to protect it from the assailants; then Cato observed that the Iberian resistance was least at the left gate, so he ordered the ''hastati'' and ''princeps'' of the second legion to move toward it.

The defenders of the gate did not withstand the assault and the Romans managed to enter. Taking advantage of the confusion, the rest of the legion finished off the defenders and the Roman army achieved total victory. According to Valerius Antias

Valerius Antias ( century BC) was an ancient Roman annalist whom Livy mentions as a source. No complete works of his survive but from the sixty-five fragments said to be his in the works of other authors it has been deduced that he wrote a chron ...

, the Hispanics suffered 40 000 casualties in the battle. Once hostilities were over the consul gave his men rest and put the substantial booty up for sale.

After the battle not only the inhabitants of Emporion surrendered, but also those of the nearby cities. Cato treated them with propriety and even helped them, and then let them go to their homes.

End of hostilities in the province of Citerior

With the victory at EmporionMarcus Porcius Cato Marcus Porcius Cato can refer to:

*Cato the Elder (consul 195 BC; called "Censorinus"), politician renowned for austerity and author

* Cato the Younger (praetor 54 BC; called " Uticensis"), opponent of Caesar

*Marcus Porcius Cato (consul ...

had achieved the pacification of all Hispania Citerior

Hispania Citerior (English: "Hither Iberia", or "Nearer Iberia") was a Roman province in Hispania during the Roman Republic. It was on the eastern coast of Iberia down to the town of Cartago Nova, today's Cartagena in the autonomous community of ...

; all the way to Tarraco

Tarraco is the ancient name of the current city of Tarragona (Catalonia, Spain). It was the oldest Roman settlement on the Iberian Peninsula. It became the capital of Hispania Tarraconensis following the latter's creation during the Roman Empire ...

all the cities were surrendering to him, and they were handing over to him the Romans they held as prisoners.

Shortly thereafter news spread that the consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states thro ...

was leaving with his army for Turdetania

Baeturia, Beturia, or Turdetania was an extensive ancient territory in the southern part of the Iberian Peninsula (in modern Spain) situated between the middle and lower courses of the Guadiana and the Guadalquivir rivers. From the Second Iron Ag ...

, which some Bergistani peoples took advantage of to take up arms. Cato easily put down the revolt on up to two occasions, but was not so lenient on the second and sold the vanquished into slavery. The tactic employed by Cato on this occasion was to reach the villages earlier than expected, thus attacking the revolters by surprise. After this, Cato ordered the disarmament of all the inhabitants of the province Citerior. (9, 17)

The consul called upon the representatives of the Hispanic cities in the area to take measures voluntarily so that they could not rebel again against Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

. Finding no response from the Hispanics Cato had the walls of all the cities torn down.

The war in the Ulterior province

Revolt of the Turdetani

Thepraetor

''Praetor'' ( , ), also ''pretor'', was the title granted by the government of ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected ''magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to disch ...

s Appius Claudius Nero and Publius Manlius were in Turdetania

Baeturia, Beturia, or Turdetania was an extensive ancient territory in the southern part of the Iberian Peninsula (in modern Spain) situated between the middle and lower courses of the Guadiana and the Guadalquivir rivers. From the Second Iron Ag ...

, waging war against the Turdetani themselves and against the Celtiberians

The Celtiberians were a group of Celts and Celticized peoples inhabiting an area in the central-northeastern Iberian Peninsula during the final centuries BC. They were explicitly mentioned as being Celts by several classic authors (e.g. Strabo) ...

mercenaries

A mercenary is a private individual who joins an War, armed conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any other official military. Mercenaries fight for money or other forms of payment rath ...

they had hired, achieving some victories. These were not, however, difficult victories, since the praetors had a good number of horsemen and veteran soldiers. But subsequently the Turdetani hired another 10 000 Celtiberians, and began to prepare again for combat.

After a triumphant campaign, Cato led his troops to Sierra Morena

The Sierra Morena is one of the main systems of mountain ranges in Spain. It stretches for 450 kilometres from east to west across the south of the Iberian Peninsula, forming the southern border of the ''Meseta Central'' plateau and providi ...

, Turdetania, in aid of the praetor

''Praetor'' ( , ), also ''pretor'', was the title granted by the government of ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected ''magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to disch ...

es Publius Manlius and Appius Claudius, (XXXIV, 19, 1–2) to the area where the Turdetani had their mines. Turdetani and Celtiberians, mercenaries in the service of the latter, were encamped in different locations. There were initially some skirmishes between Romans and Turdetani, always with a favorable outcome for the former. Cato's tribune

Tribune () was the title of various elected officials in ancient Rome. The two most important were the Tribune of the Plebs, tribunes of the plebs and the military tribunes. For most of Roman history, a college of ten tribunes of the plebs ac ...

emissaries were sent by Cato to convince the Celtiberians to withdraw to their lands without putting up a battle or to join the Roman army, charging double what was promised by the Turdetani. Faced with this proposition the Celtiberians asked for time to think, but, as the Turdetani joined the meeting, no agreement was reached. The Celtiberians, however, decided for their part not to present battle. After losing Celtiberian military support, the Turdetani were defeated. This defeat meant the loss of their mining possessions, which forced the Turdetani to remain in the Guadalquivir

The Guadalquivir (, also , , ) is the fifth-longest river in the Iberian Peninsula and the second-longest river with its entire length in Spain. The Guadalquivir is the only major navigable river in Spain. Currently it is navigable from Seville ...

valley, devoting themselves to agriculture and cattle raising.

Passing through Celtiberia

Cato the Elder

Marcus Porcius Cato (, ; 234–149 BC), also known as Cato the Censor (), the Elder and the Wise, was a Roman soldier, Roman Senate, senator, and Roman historiography, historian known for his conservatism and opposition to Hellenization. He wa ...

returned north across Celtiberia

The Celtiberians were a group of Celts and Celticized peoples inhabiting an area in the central-northeastern Iberian Peninsula during the final centuries BC. They were explicitly mentioned as being Celts by several classic authors (e.g. Strabo) ...

to intimidate the Celtiberians and prevent future uprisings, and in retaliation for having joined the uprising of the Turdetani. He headed towards Segontia, as rumor had reached him that it was the square where greater booty could be obtained, and besieged the city without success due to lack of time. He then headed towards Numantia

Numantia () is an ancient Celtiberian settlement, whose remains are located on a hill known as Cerro de la Muela in the current municipality of Garray ( Soria), Spain.

Numantia is famous for its role in the Celtiberian Wars. In 153 BC, Num ...

, in the vicinity of which he addressed a speech to his ''equites''.

He subsequently returned to the province Citerior, leaving part of his army with the praetor

''Praetor'' ( , ), also ''pretor'', was the title granted by the government of ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected ''magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to disch ...

es after having paid his salary to the soldiers,Everything indicates that in addition to this "regular" salary, the soldiers also received part of the final booty. — (XXXIV, 46, 2) (Cat. Mai. 10, 4) and taking with him seven cohorts.

Returning from Turdetania Cato achieved the subjugation of ausetani

The Ausetani were an ancient Iberian (pre-Roman) people of the Iberian Peninsula (the Roman Hispania). They are believed to have spoken the Iberian language. They lived in the eponymous region of Ausona and gave their name to the Roman city of '' ...

, suessetani

The Suessetani were a pre-Roman people of the northeast Iberian Peninsula that dwelt mainly in the plains area of the Alba (Arba) river basin (a northern tributary of the Ebro river), in today's Cinco Villas, Aragon, Zaragoza Province (westernmos ...

and sedetani. The consul was able to take advantage of the unease of his allies with the Lacetani

The Lacetani were an ancient Iberian (pre- Roman) people of the Iberian Peninsula (the Roman Hispania).

There remains some doubt whether their naming is not a corruption of either '' Laeetani'' or '' Iacetani'', the names of two neighboring pe ...

, who had taken advantage of the Roman expedition to Turdetania to raid their villages. When the Roman contingent reached the city of the Lacetani, Cato sent part of his cohortsPlutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

notes that Cato employed five cohorts and 500 horsemen for this operation. He also indicates that 600 Roman deserters who had joined the Lacetani were immediately executed. — (Cat. Mai. 11, 2) to stand on one side and the others to stand on the opposite side. Thereupon he ordered the allies, Suessetani for the most part, to attack the wall. The Lacetani, confident that they could easily defeat the Suessetani, opened a gate and went out to meet them; the Suessetani fled and the enemies pursued them. Then the consul ordered the cohorts to enter the town immediately, who surprised the Lacetani. After this the Lacetani surrendered.

Third uprising of the Bergistani

Subsequently theconsul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states thro ...

Marcus Porcius Cato Marcus Porcius Cato can refer to:

*Cato the Elder (consul 195 BC; called "Censorinus"), politician renowned for austerity and author

* Cato the Younger (praetor 54 BC; called " Uticensis"), opponent of Caesar

*Marcus Porcius Cato (consul ...

headed back towards the Citerior province, towards the territory of the Bergistani, who had rebelled again and were resisting in the fortress of castrum Bergium.The site of the main castle, castrum Bergium, may correspond to the present-day town of Berga

Berga () is the capital of the ''Catalonia/Comarques, comarca'' (county) of Berguedà, in the province of Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain. It is bordered by the municipalities of Cercs, Olvan, Avià, Capolat and Castellar del Riu.

History

Berga de ...

, although there is also a Berge in Lower Aragon. — Upon arriving in the city the Bergistani leader went to Cato to tell him that he and his people were still loyal to Rome, and that it was outsiders who had taken control of the city and were hostile to the Romans, and that they were also engaged in plundering the inhabitants of the province Citerior. In this way, Cato devises a strategy to test whether or not the Bergistani were loyal to him, and in the process conquer the square more easily. Cato then ordered the Bergistani leader that he and his loyalists should occupy the citadel when the Roman siege began, an order which the Bergistani carried out; the bandits were then surrounded and defeated. After the battle Cato ordered that the citizens who had been loyal to his plan be freed, the remaining Bergistani enslaved, and the foreign bandits executed.

Consequences

Victory management

Once he had reduced the Hispanic insurgents settled in the territory located between the Iberus River and thePyrenees

The Pyrenees are a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. They extend nearly from their union with the Cantabrian Mountains to Cap de Creus on the Mediterranean coast, reaching a maximum elevation of at the peak of Aneto. ...

, Cato the Elder

Marcus Porcius Cato (, ; 234–149 BC), also known as Cato the Censor (), the Elder and the Wise, was a Roman soldier, Roman Senate, senator, and Roman historiography, historian known for his conservatism and opposition to Hellenization. He wa ...

turned his attention to the administration of the province. During his rule revenues increased, as the state's profits from the exploitation of mining resources increased, mainly silver and iron, as well as of a large mount of salt in which the consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states thro ...

took an interest. It seems that Cato was able to see the reasons that had motivated the revolt, surely the excessive taxes on the Hispanians; so he reorganized the collection, increasing the profit that remained in Hispania.

While Cato was still in Hispania

Hispania was the Ancient Rome, Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two Roman province, provinces: Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior. During the Principate, Hispania Ulterior was divide ...

, the new consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states thro ...

who was to succeed him and the successors of the praetor

''Praetor'' ( , ), also ''pretor'', was the title granted by the government of ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected ''magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to disch ...

es were elected in Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

. He was again elected consul Scipio Africanus

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus (, , ; 236/235–) was a Roman general and statesman who was one of the main architects of Rome's victory against Ancient Carthage, Carthage in the Second Punic War. Often regarded as one of the greatest milit ...

, Cato's rival, and praetors Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica for the province Ulterior and Sextus Digitius for Citerior. Scipio's intention was to be posted to Hispania, but the senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

decided that the new consul's destination should be Italy since the Hispanic provinces had been pacified.

Because of Cato's successes in Hispania, the senate approved three days of public prayers; and resolved also that the soldiers who had acted in Hispania during the revolt be discharged.

In late 194 BC, Marcus Porcius Cato returned to Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

with a huge war trophies

__NOTOC__

A war trophy is an item taken during warfare by an invading force. Common war trophies include flags, weapons, vehicles, and art.

History

In ancient Greece and ancient Rome, military victories were commemorated with a display of capt ...

consisting of 25 000 pounds and 123 000 pieces in ''bigati'' of silver, 540 pieces of silver from '' Uesca'' and 1400 pounds of gold; (XXXIV, 46, 2) all taken from the Hispanic peoples in their military actions.A portion of this treasure is that known as ''argentum oscense''. —The Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

granted him to celebrate a ''triumphus''. — (Cat. Mai. 4, 3) which is documented in the ''Fasti Triumphales

The ''Acta Triumphorum'' or ''Triumphalia'', better known as the ''Fasti Triumphales'', or Triumphal Fasti, is a calendar of Roman magistrates honoured with a celebratory procession known as a ''triumphus'', or triumph, in recognition of an impo ...

''. Cato distributed part of the booty among the soldiers who had served under him.

The victory in the war of Hispania

Hispania was the Ancient Rome, Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two Roman province, provinces: Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior. During the Principate, Hispania Ulterior was divide ...

was a great boost to the career of Marcus Porcius Cato, as it allowed him to reach the military heights of his opponents. This success meant, in particular, that he was able to rub shoulders with his great rival Scipio Africanus

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus (, , ; 236/235–) was a Roman general and statesman who was one of the main architects of Rome's victory against Ancient Carthage, Carthage in the Second Punic War. Often regarded as one of the greatest milit ...

.

Upon the return of Cato the Elder

Marcus Porcius Cato (, ; 234–149 BC), also known as Cato the Censor (), the Elder and the Wise, was a Roman soldier, Roman Senate, senator, and Roman historiography, historian known for his conservatism and opposition to Hellenization. He wa ...

to Rome and the arrival of the new praetors who succeeded him in the Hispanic provinces, another rebellion occurred again. The praetor

''Praetor'' ( , ), also ''pretor'', was the title granted by the government of ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected ''magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to disch ...

Sextus Digitius clashed on many occasions with the revolters, losing in the fighting up to half of his troops.

Continuation of the process of conquest

Celtiberia

Hispania

Hispania was the Ancient Rome, Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two Roman province, provinces: Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior. During the Principate, Hispania Ulterior was divide ...

, the process of conquest continued after the actions of Cato; thus, the proconsul

A proconsul was an official of ancient Rome who acted on behalf of a Roman consul, consul. A proconsul was typically a former consul. The term is also used in recent history for officials with delegated authority.

In the Roman Republic, military ...

Marcus Fulvius Nobilior subsequently fought other rebellions. Then Rome began the conquest of Lusitania

Lusitania (; ) was an ancient Iberian Roman province encompassing most of modern-day Portugal (south of the Douro River) and a large portion of western Spain (the present Extremadura and Province of Salamanca). Romans named the region after th ...

, with two outstanding victories: in 189 BC that obtained by the proconsul Lucius Aemilius Paullus Macedonicus

Lucius Aemilius Paullus Macedonicus (c. 229 – 160 BC) was a Roman consul, consul of the Roman Republic, as well as a general, who conquered the kingdom of Macedon, Macedonia during the Third Macedonian War.

Family

Paullus' father was Luc ...

, and in 185 BC. that obtained by the praetor or proconsul Gaius Calpurnius Pisonus.

The conquest of Celtiberia

The Celtiberians were a group of Celts and Celticized peoples inhabiting an area in the central-northeastern Iberian Peninsula during the final centuries BC. They were explicitly mentioned as being Celts by several classic authors (e.g. Strabo) ...

was initiated in 181 BC by Quintus Fulvius Flaccus, who managed to defeat the Celtiberians

The Celtiberians were a group of Celts and Celticized peoples inhabiting an area in the central-northeastern Iberian Peninsula during the final centuries BC. They were explicitly mentioned as being Celts by several classic authors (e.g. Strabo) ...

and subdue some territories, obtaining for it the honor of an ovation

The ovation ( from ''ovare'': to rejoice) was a lesser form of the Roman triumph. Ovations were granted when war was not declared between enemies on the level of nations or states; when an enemy was considered basely inferior (e.g., slaves, pira ...

in 191 BC. However, most of the conquest and pacification operations were carried out by praetor

''Praetor'' ( , ), also ''pretor'', was the title granted by the government of ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected ''magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to disch ...

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus from 179 BC to 178 BC. Sempronius took some thirty cities and villages, using various types of strategies, sometimes making pacts and sometimes stirring up rivalry between CeltiberiansThe fighting arts and equipment of the Celtiberians were well described by Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus or Diodorus of Sicily (; 1st century BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek historian from Sicily. He is known for writing the monumental Universal history (genre), universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty ...

(1st century BC), who showed his admiration for their bravery and skill. He also described their weapons, as well as their method of making steel, which he described as "excellent". — (V, 33) and Vascones

The Vascones were a pre- Roman tribe who, on the arrival of the Romans in the 1st century, inhabited a territory that spanned between the upper course of the Ebro river and the southern basin of the western Pyrenees, a region that coincides w ...

, and founded over the already existing city of Ilurcis the new city of Gracchurris.

Lusitania

Subsequently problems would come fromLusitania

Lusitania (; ) was an ancient Iberian Roman province encompassing most of modern-day Portugal (south of the Douro River) and a large portion of western Spain (the present Extremadura and Province of Salamanca). Romans named the region after th ...

, where from 155 BC. Punicus

Punicus (known as ''Púnico'' in Portuguese and Spanish; died 153 BC) was a chieftain of the Lusitanians, a proto-Celtic tribe from western Hispania. He became their first military leader during the Lusitanian War, and also led their first majo ...

conducted major campaigns in territory controlled by the Republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

, plundering territories in Baetica

Hispania Baetica, often abbreviated Baetica, was one of three Roman provinces created in Hispania (the Iberian Peninsula) in 27 BC. Baetica was bordered to the west by Lusitania, and to the northeast by Tarraconensis. Baetica remained one of ...

and reached the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

coast, with the Vettones

The Vettones (Greek language, Greek: ''Ouettones'') were an Prehistoric Iberia#Iron Age, Iron Age pre-Roman people of the Iberian Peninsula.

Origins

Lujan (2007) concludes that some of the names of the Vettones show clearly Hispano-Celtic lan ...

as allies. He achieved great victories such as the one against the Roman praetors Marcus Manlius and Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus.

From 147 BC the republic should face a new Lusitanian enemy, the initially shepherd Viriathus

Viriathus (also spelled Viriatus; known as Viriato in Portuguese language, Portuguese and Spanish language, Spanish; died 139 Anno Domini, BC) was the most important leader of the Lusitanians, Lusitanian people that resisted Roman Republic, Roma ...

, who would become from then on a great headache for Rome, so much so that he came to be called ''the terror of Rome''. He managed to flee the slaughter of Servius Sulpicius Galba Servius Sulpicius Galba may refer to:

* Servius Sulpicius Galba (consul 144 BC)

* Servius Sulpicius Galba (consul 108 BC)

* Servius Sulpicius Galba (praetor 54 BC), assassin of Julius Caesar

* Galba, born Servius Sulpicius Galba, Roman emperor fro ...

in 151 BC, and subsequently rebelled, achieving several victories against the Romans. He also conquered several cities, such as ''Tucci'' (probably present-day Martos

Martos is a city and municipality of Spain belonging to the province of Jaén in the autonomous community of Andalusia.

With a population of over 24,000 people, Martos is the fifth largest municipality in the province and the second in Jaén ...