Ian Carmichael on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ian Gillett Carmichael, (18 June 1920 – 5 February 2010) was an English actor who worked prolifically on stage, screen and radio in a career that spanned seventy years. Born in

Ian Gillett Carmichael was born on 18 June 1920 in

Ian Gillett Carmichael was born on 18 June 1920 in

Tastes in film changed in the late 1950s and early 1960s, with the new wave of British films moving away from plots centred on the

Tastes in film changed in the late 1950s and early 1960s, with the new wave of British films moving away from plots centred on the

BBC Humber feature on Ian Carmichael

{{DEFAULTSORT:Carmichael, Ian 1920 births 2010 deaths Military personnel from Kingston upon Hull British Army personnel of World War II English male film actors English male radio actors English male stage actors English male television actors Officers of the Order of the British Empire People educated at Bromsgrove School Male actors from Kingston upon Hull Royal Armoured Corps officers Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst Alumni of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art People educated at Scarborough College 22nd Dragoons officers

Kingston upon Hull

Kingston upon Hull, usually shortened to Hull, is a historic maritime city and unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England. It lies upon the River Hull at its confluence with the Humber Est ...

, in the East Riding of Yorkshire

The East Riding of Yorkshire, often abbreviated to the East Riding or East Yorkshire, is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the Yorkshire and the Humber region of England. It borders North Yorkshire to the north and west, S ...

, he trained at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art

The Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, also known by its abbreviation RADA (), is a drama school in London, England, which provides vocational conservatoire training for theatre, film, television, and radio. It is based in Bloomsbury, Central London ...

, but his studies—and the early stages of his career—were curtailed by the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. After his demobilisation

Demobilization or demobilisation (see spelling differences) is the process of standing down a nation's armed forces from combat-ready status. This may be as a result of victory in war, or because a crisis has been peacefully resolved and milita ...

he returned to acting and found success, initially in revue

A revue is a type of multi-act popular theatre, theatrical entertainment that combines music, dance, and sketch comedy, sketches. The revue has its roots in 19th century popular entertainment and melodrama but grew into a substantial cultural pre ...

and sketch productions.

In 1955 Carmichael was noticed by the film producers John and Roy Boulting

John Edward Boulting (21 December 1913 – 17 June 1985) and Roy Alfred Clarence Boulting (21 December 1913 – 5 November 2001), known collectively as the Boulting brothers, were English filmmakers and identical twins who became known for thei ...

, who cast him in five of their films as one of the major players. The first was the 1956 film ''Private's Progress

''Private's Progress'' is a 1956 British comedy film directed by John Boulting and starring Richard Attenborough, Dennis Price, Terry-Thomas and Ian Carmichael. The script was by John Boulting and Frank Harvey, based on the novel of the same ...

'', a satire on the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

; he received critical and popular praise for the role, including from the American market. In many of his roles he played a likeable, often accident-prone, innocent. In the mid-1960s he played Bertie Wooster

Bertram Wilberforce Wooster is a fictional character in the comedic Jeeves stories created by British author P. G. Wodehouse. An amiable English gentleman and one of the "idle rich", Bertie appears alongside his valet, Jeeves, whose intellige ...

in adaptations of the works of P. G. Wodehouse

Sir Pelham Grenville Wodehouse ( ; 15 October 1881 – 14 February 1975) was an English writer and one of the most widely read humorists of the 20th century. His creations include the feather-brained Bertie Wooster and his sagacious valet, Je ...

in '' The World of Wooster'' for BBC Television

BBC Television is a service of the BBC. The corporation has operated a Public service broadcasting in the United Kingdom, public broadcast television service in the United Kingdom, under the terms of a royal charter, since 1 January 1927. It p ...

, for which he received mostly positive reviews, including from Wodehouse. In the early 1970s he played another upper-class

Upper class in modern societies is the social class composed of people who hold the highest social status. Usually, these are the wealthiest members of class society, and wield the greatest political power. According to this view, the upper cla ...

literary character, Lord Peter Wimsey

Lord Peter Death Bredon Wimsey (later 17th Duke of Denver) is the fictional protagonist in a series of detective novels and short stories by Dorothy L. Sayers (and their continuation by Jill Paton Walsh). A amateur, dilettante who solves myst ...

, the amateur but talented investigator created by Dorothy L. Sayers.

Much of Carmichael's success came through a disciplined approach to training and rehearsing for a role. He learned much about the craft and technique of humour while appearing with the comic actor Leo Franklyn. Although Carmichael tired of being typecast as the affable but bumbling upper-class Englishman, his craft ensured that while audiences laughed at his antics, he retained their affection; Dennis Barker, in Carmichael's obituary in ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'', wrote that he "could play fool parts in a way that did not cut the characters completely off from human sympathy: a certain dignity was always maintained".

Biography

Early life

Ian Gillett Carmichael was born on 18 June 1920 in

Ian Gillett Carmichael was born on 18 June 1920 in Kingston upon Hull

Kingston upon Hull, usually shortened to Hull, is a historic maritime city and unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England. It lies upon the River Hull at its confluence with the Humber Est ...

, in the East Riding of Yorkshire

The East Riding of Yorkshire, often abbreviated to the East Riding or East Yorkshire, is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the Yorkshire and the Humber region of England. It borders North Yorkshire to the north and west, S ...

. He was the eldest child of Kate ( Gillett) and her husband Arthur Denholm Carmichael, an optician on the premises of his family's firm of jewellers. Carmichael had two younger sisters, the twins Mary and Margaret, who were born in December 1923. Robert Fairclough, his biographer, describes Carmichael's upbringing as a "privileged, pampered existence"; his parents employed maids and a cook. His infant education included one term at the local Froebel House School when he was four, but this was curtailed after his parents were shocked at the "alarmingly foul language he began bringing home", according to Alex Jennings, Carmichael's biographer in the ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from History of the British Isles, British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') ...

''.

In 1928 Carmichael was sent to Scarborough College, a prep school in North Yorkshire

North Yorkshire is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in Northern England.The Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority areas of City of York, York and North Yorkshire (district), North Yorkshire are in Yorkshire and t ...

, which he attended between the ages of seven and thirteen. He did not like the spartan and authoritarian regime at the school. He described the discipline as " Dickensian", with corporal punishment

A corporal punishment or a physical punishment is a punishment which is intended to cause physical pain to a person. When it is inflicted on Minor (law), minors, especially in home and school settings, its methods may include spanking or Padd ...

used for even minor infringements of the rules; ablutions in the morning and evening were conducted with cold water—which often had a film of ice on the top during winter.

In 1933 Carmichael left Scarborough College and entered Bromsgrove School

Bromsgrove School is a co-educational boarding and day school in the Worcestershire town of Bromsgrove, England. Founded in 1553, it is one of the oldest public schools in Britain, and one of the 14 founding members of the Headmasters' Confer ...

, a public school in Worcestershire

Worcestershire ( , ; written abbreviation: Worcs) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England. It is bordered by Shropshire, Staffordshire, and the West Midlands (county), West ...

. He soon concluded that "the new curriculum was not arduous", which gave him the opportunity for focus on matters that were of more interest for him: acting, popular music and cricket. In the late 1930s Carmichael decided to go to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art

The Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, also known by its abbreviation RADA (), is a drama school in London, England, which provides vocational conservatoire training for theatre, film, television, and radio. It is based in Bloomsbury, Central London ...

(RADA) in London. His parents would have preferred he went into the family jewellery business, but accepted their son's decision and supported him financially when he left Yorkshire for London in January 1939.

Early career and war service, 1939–1946

Carmichael enjoyed his time at RADA, including the fact that women outnumbered men on his course, which he described as "heady stuff" after his boys-only boarding school. He remembered the time at RADA in the late 1930s fondly in his autobiography, describing it as:A period of unconfined joy, occasioned by my finally shaking off the shackles of school discipline and being able to mix daily with young men and young women who shared my interests and enthusiasms. This joy was, nevertheless, being tempered by the worsening European situation. The fear that now, just as I was standing on the threshold of a future that I had dreamed about for years, the whole thing might be snuffed out like a candle was too unbearable to contemplate.During his second term Carmichael had his first professional acting role: as a robot in

Karel Čapek

Karel Čapek (; 9 January 1890 – 25 December 1938) was a Czech writer, playwright, critic and journalist. He has become best known for his science fiction, including his novel '' War with the Newts'' (1936) and play '' R.U.R.'' (''Rossum' ...

's '' R.U.R.'' at the People's Palace theatre, in Mile End

Mile End is an area in London, England and is located in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is in East London and part of the East End of London, East End. It is east of Charing Cross. Situated on the part of the London-to-Colchester road ...

, East London. He recalled the experience as "a dull play performed in a cold and uninspiring theatre and my particular contribution required absolutely no acting talent whatsoever". He then appeared as Flute

The flute is a member of a family of musical instruments in the woodwind group. Like all woodwinds, flutes are aerophones, producing sound with a vibrating column of air. Flutes produce sound when the player's air flows across an opening. In th ...

in ''A Midsummer Night's Dream

''A Midsummer Night's Dream'' is a Comedy (drama), comedy play written by William Shakespeare in about 1595 or 1596. The play is set in Athens, and consists of several subplots that revolve around the marriage of Theseus and Hippolyta. One s ...

'' at RADA's Vanbrugh Theatre. The opening night was 1 September 1939, the day Hitler invaded Poland. After the play's second performance its run was ended, as RADA shut down in anticipation that war was about to be declared; the following day the UK joined the war. Carmichael returned to his familial home and completed the forms to join the Officer Cadet Reserve, hoping to be commissioned as an officer. He helped gather the harvest in a nearby farm until 2 October, when he was attested into the army; he was told he would have to wait until he was twenty—on 18 June 1940—before he started training.

As the early months of the war were marked by limited military action, RADA reassessed its closure, and decided to reopen. Carmichael returned to London and shared lodgings with two fellow RADA students, Geoffrey Hibbert and Patrick Macnee; Carmichael and Macnee became lifelong friends. Between June and August 1940 Carmichael was on a ten-week tour of ''Nine Sharp'', a revue

A revue is a type of multi-act popular theatre, theatrical entertainment that combines music, dance, and sketch comedy, sketches. The revue has its roots in 19th century popular entertainment and melodrama but grew into a substantial cultural pre ...

developed by Herbert Farjeon. After the tour Carmichael reported for training on 12 September at Catterick Garrison

Catterick Garrison is a major garrison and List of modern military towns, military town south of Richmond, North Yorkshire, Richmond, North Yorkshire, England. It is the largest British Army garrison in the world, with a population of around 14 ...

. After ten weeks' basic training, he was posted to the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst

The Royal Military Academy Sandhurst (RMAS or RMA Sandhurst), commonly known simply as Sandhurst, is one of several military academy, military academies of the United Kingdom and is the British Army's initial Commissioned officer, officer train ...

to become an officer cadet. He completed his training and passed out in March 1941 as a second lieutenant in the 22nd Dragoons, part of the Royal Armoured Corps

The Royal Armoured Corps is the armoured arm of the British Army, that together with the Household Cavalry provides its armour capability, with vehicles such as the Challenger 2 and the Warrior tracked armoured vehicle. It includes most of the Ar ...

.

At the end of training manoeuvres in November 1941, near Whitby

Whitby is a seaside town, port and civil parish in North Yorkshire, England. It is on the Yorkshire Coast at the mouth of the River Esk, North Yorkshire, River Esk and has a maritime, mineral and tourist economy.

From the Middle Ages, Whitby ...

, North Yorkshire, Carmichael was struggling to close the hatch of his Valentine tank

The Tank, Infantry, Mk III, Valentine was an infantry tank produced in the United Kingdom during World War II. More than 8,000 Valentines were produced in eleven marks, plus specialised variants, accounting for about a quarter of wartime Britis ...

when it slammed down, cutting off the top of a finger on his left hand. The surgery was botched and caused him pain for several months; he had a second operation several months later. He described it as "dashed unfortunate" and "my one and only war-wound, albeit a self-inflicted one".

In between training for the liberation of France Carmichael began producing revues and productions as part of his brigade's entertainment. On 16 June 1944, ten days after D-Day

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during the Second World War. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

, Carmichael and his armoured reconnaissance troop landed in France. He fought through to Germany with the regiment and by the time of Victory in Europe Day

Victory in Europe Day is the day celebrating the formal acceptance by the Allies of World War II of Germany's unconditional surrender of its armed forces on Tuesday, 8 May 1945; it marked the official surrender of all German military operations ...

in May 1945, he had been promoted to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

and mentioned in despatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face of t ...

.

Carmichael's regiment was part of 30 Corps and an initial post-war challenge in Germany was the welfare of the occupying forces. The corps' commanding officer was Lieutenant-General Brian Horrocks, who ordered a repertory company to be formed for entertainment. When Carmichael auditioned he recognised the major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

in charge of the unit as Richard Stone, an actor who had been a contemporary at RADA; Carmichael was taken into the company and assisted Stone with auditioning other members. One of the comedians who auditioned was Frankie Howerd

Francis Alick Howard (6 March 1917 – 19 April 1992), better known by his stage-name Frankie Howerd, was an English actor and comedian.

Early life

Howerd was born the son of a soldier Francis Alfred William (1887–1934)England & Wales, Deat ...

, whom Carmichael thought "very gauche ... too undisciplined and not very funny either. Very much the amateur". Stone disagreed and signed the comic up to perform in a Royal Army Service Corps

The Royal Army Service Corps (RASC) was a corps of the British Army responsible for land, coastal and lake transport, air despatch, barracks administration, the Army Fire Service, staffing headquarters' units, supply of food, water, fuel and do ...

concert party. The corps' company was also joined by actors from Entertainments National Service Association

The Entertainments National Service Association (ENSA) was an organisation established in 1939 by Basil Dean and Leslie Henson to provide entertainment for British armed forces personnel during World War II. ENSA operated as part of the Navy, ...

(ENSA); Carmichael did not often appear on stage with them, but worked as the producer of twenty shows. In April 1946 Stone was promoted and was transferred to the UK; Carmichael was promoted to major and took control of the theatrical company. His leadership of the company was short-lived, as he was demobilised

Demobilization or demobilisation (see American and British English spelling differences, spelling differences) is the process of standing down a nation's armed forces from combat-ready status. This may be as a result of victory in war, or becaus ...

that July.

Early post-war career, 1946–1955

In July 1946 Carmichael signed with Stone, who had also been demobilised and had set up as a theatrical agent. Carmichael obtained his first post-war role in the revue ''Between Ourselves'' in mid-1946 before he appeared in two small roles in the comedy '' She Wanted a Cream Front Door''— a hotel receptionist and a BBC reporter. The production went on a twelve-week tour round Britain from October 1946, and then ran at the Apollo Theatre in Shaftesbury Avenue, London, for four months. Between 1947 and 1951 Carmichael appeared on stage in both plays and revues —the latter often at thePlayers' Theatre

The Players' Theatre was a London theatre which opened at 43 King Street, Covent Garden, on 18 October 1936. The club originally mounted period-style musical comedies, introducing Victorian-style music hall in December 1937. The threat of Worl ...

in Villiers Street, Charing Cross. He made his debut appearance on BBC television

BBC Television is a service of the BBC. The corporation has operated a Public service broadcasting in the United Kingdom, public broadcast television service in the United Kingdom, under the terms of a royal charter, since 1 January 1927. It p ...

in 1947 in ''New Faces'', a revue that also included Zoe Gail, Bill Fraser and Charles Hawtrey. From 1948 he also began appearing in films, including ''Bond Street

Bond Street in the West End of London links Piccadilly in the south to Oxford Street in the north. Since the 18th century the street has housed many prestigious and upmarket fashion retailers. The southern section is Old Bond Street and the l ...

'' (1948), '' Trottie True'' and '' Dear Mr. Prohack'' (both 1949); these early roles were minor parts and he was uncredited. He spent much of 1949 in a thirty-week tour of Britain with the operetta '' The Lilac Domino''. According to Jennings, Carmichael's "first conspicuous success" was ''The Lyric Revue'' in 1951; the production transferred to The Globe (now the Gielgud Theatre

The Gielgud Theatre is a West End theatre, located on Shaftesbury Avenue, at the corner of Rupert Street, in the City of Westminster, London. The house currently has 994 seats on three levels.

The theatre was designed by W. G. R. Sprague and ...

) as ''The Globe Revue'' in 1952. He received a positive review in the industry publication ''The Stage

''The Stage'' is a British weekly newspaper and website covering the entertainment industry and particularly theatre. Founded in 1880, ''The Stage'' contains news, reviews, opinion, features, and recruitment advertising, mainly directed at thos ...

'', which reported that he " hits the bull's-eye" for his comic performance in one sketch, "Bank Holiday", which involved him undressing on the beach under a mackintosh

The Mackintosh raincoat (abbreviated as mac) is a form of waterproof raincoat, first sold in 1824, made of rubberised textile, fabric.

The Mackintosh is named after its Scotland, Scottish inventor Charles Macintosh, although many writers adde ...

.

Carmichael spent the next three years appearing in stage revues and small roles in films. Although he enjoyed working in revues, he was concerned about being stuck in a career rut. In a 1954 interview in ''The Stage'', he said "I'm afraid that managers and directors may think of me only as a revue artist, and much as I enjoy acting in sketches I feel there must be a limit to the number of characters one is able to create. What I would like now is to be offered a part in light comedy or a farce". Between November 1954 and May 1955 he appeared as David Prentice in the stage production of ''Simon and Laura'' alongside Roland Culver

Roland Joseph Culver, (31 August 1900 – 1 March 1984) was an English stage, film, and television actor.

Early life

After Highgate School, Culver joined the Royal Air Force and served as a pilot from 1918 to 1919.

Career

After considering ...

and Coral Browne at the Strand Theatre, London. The following year a film version was directed by Muriel Box; she asked Carmichael to repeat his role, while Browne and Culver's roles were taken by Kay Kendall

Justine Kay Kendall McCarthy (21 May 1927 – 6 September 1959) was an English actress and singer. She began her film career in the musical film ''London Town (1946 film), London Town'' (1946), a financial failure. Kendall worked regularly unti ...

and Peter Finch. The reviewer for ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' thought Carmichael "comes near to stealing the film from both of them". In 1955 Carmichael also appeared in '' The Colditz Story''. He played Robin Cartwright, an officer in the Guards, and spent much of his screen time appearing with Richard Wattis; the two men provided an element of comic relief

Comic Relief is a British charity, founded in 1986 by the comedy scriptwriter Richard Curtis and comedian Sir Lenny Henry in response to the 1983–1985 famine in Ethiopia. The concept of Comic Relief was to get British comedians to make t ...

in the film, with what Fairclough describes as a " Flanagan and Allen tribute act". ''The Colditz Story'' was Carmichael's ninth film role and he had, Fairclough notes, risen to sixth in the credits behind John Mills and Eric Portman

Eric Harold Portman (13 July 1901 – 7 December 1969) was an English stage and film actor. He is probably best remembered for his roles in three films for Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger during the 1940s.

Early life

Born in Halifax, ...

.

Screen success, 1955–1962

In 1955 Carmichael was contacted by the filmmaker twins the Boulting brothers. They wanted him to appear in two film versions of novels—''Private's Progress'' by Alan Hackney and '' Brothers in Law'' byHenry Cecil

Sir Henry Richard Amherst Cecil (11 January 1943 – 11 June 2013) was a British flat racing horse trainer. Cecil was very successful, becoming Champion Trainer ten times and training 25 domestic Classic winners. These comprised four winners o ...

—with an option for five films in all; the final contract was for a total of six films. The Boultings' first work with Carmichael was the 1956 film ''Private's Progress

''Private's Progress'' is a 1956 British comedy film directed by John Boulting and starring Richard Attenborough, Dennis Price, Terry-Thomas and Ian Carmichael. The script was by John Boulting and Frank Harvey, based on the novel of the same ...

'', a satire on the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

. The film opened in February 1956 and starred Carmichael, Richard Attenborough

Richard Samuel Attenborough, Baron Attenborough (; 29 August 192324 August 2014) was an English actor, film director, and Film producer, producer.

Attenborough was the president of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) and the British Acade ...

, Dennis Price and Terry-Thomas

Terry-Thomas (born Thomas Terry Hoar Stevens; 10 July 1911 – 8 January 1990) was an English character actor and comedian who became internationally known through his films during the 1950s and 1960s. He often portrayed disreputable members ...

. The film historian Alan Boulton observed "Reviews were decidedly mixed and the critical response did not match the popular enthusiasm for the film"; it was either the second or third most popular film at the British box office that year. Carmichael received praise for his role, however, including from ''The Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'', which thought he "fulfils his promise as a comedian"; the reviewer for ''The Times'' thought Carmichael acted "with an unfailing tact and sympathy—he even manages to make a drunken scene seem rich in comedy". The film introduced American audiences to Carmichael, and his screen presence in the US was warmly received by reviewers. The reviewer Margaret Hinxman, writing in ''Picturegoer

''Picturegoer'' was a fan magazine published in the United Kingdom between 1911 and 23 April 1960.

Background

The magazine was started in 1911 under the name ''The Pictures'' and in 1914 it merged with ''Picturegoer''. Following the merge it was ...

'', considered that after ''Private's Progress'' Carmichael had become "one of Britain's choicest screen exports".

From June to September 1956 Carmichael was involved in the filming of '' Brothers in Law'', which was directed by Roy Boulting

John Edward Boulting (21 December 1913 – 17 June 1985) and Roy Alfred Clarence Boulting (21 December 1913 – 5 November 2001), known collectively as the Boulting brothers, were English filmmakers and identical twins who became known for thei ...

; others in the cast included Attenborough and Terry-Thomas. When the film was released in March 1957 Carmichael received positive reviews, including from Philip Oakes, the reviewer from ''The Evening Standard'', who concluded that Carmichael "confirms his placing in my form book as our best light comedian". The reviewer for ''The Manchester Guardian'' thought Carmichael was "irrepressibly funny in his well-bred, well-intentioned, bewildered ineptitude".

In September 1957 Carmichael appeared in a third Boulting brothers film, ''Lucky Jim

''Lucky Jim'' is a novel by Kingsley Amis, first published in 1954 by Victor Gollancz Ltd, Victor Gollancz. It was Amis's first novel and won the 1955 Somerset Maugham Award for fiction. The novel follows the academic and romantic tribulations ...

'' in which he appeared alongside Terry-Thomas and Hugh Griffith in an adaptation of a 1954 novel by Kingsley Amis

Sir Kingsley William Amis (16 April 1922 – 22 October 1995) was an English novelist, poet, critic and teacher. He wrote more than 20 novels, six volumes of poetry, a memoir, short stories, radio and television scripts, and works of social crit ...

. Fairclough notes that while the film was not well received by the critics, Carmichael's performance received great praise. ''The Manchester Guardian'' considered that Carmichael, "although in many ways excellent, has fewer chances than in ''Brothers-in-Law'' to delight us with those studies in agonised embarrassment in which he excels", while ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a British daily broadsheet conservative newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed in the United Kingdom and internationally. It was found ...

'' reviewer considered " armichael'sJim, complete with North-Country accent and the ability to pull comic faces, might so easily have been the author's creation brought to life off the page."

Carmichael then appeared in a fourth film with the Boultings, '' Happy Is the Bride'', a lightweight comedy of manners

In English literature, the term comedy of manners (also anti-sentimental comedy) describes a genre of realistic, satirical comedy that questions and comments upon the manners and social conventions of a greatly sophisticated, artificial society. ...

released in March 1958 which also included Janette Scott

Thora Janette Scott (born 14 December 1938) is a British retired actress.

Life and career

Scott was born on 14 December 1938 in Morecambe, Lancashire, England. She is the daughter of actors Jimmy Scott and Thora Hird and began her career as ...

, Cecil Parker

Cecil Parker (born Cecil Schwabe; 3 September 1897 – 20 April 1971) was an English actor with a distinctively husky voice, who usually played supporting roles, often characters with a supercilious demeanour, in his 91 films made between 1 ...

, Terry-Thomas and Joyce Grenfell

Joyce Irene Grenfell (''née'' Phipps; 10 February 1910 – 30 November 1979) was an English diseuse, singer, actress and writer. She was known for the songs and monologues she wrote and performed, at first in revues and later in her solo show ...

. Carmichael spent much of the end of 1957 and most of 1958 on stage with '' The Tunnel of Love''. The journalist R. B. Marriott described it as a "slightly crazy, wonderfully ridiculous comedy", and it had a five-week tour around the UK which preceded a run at Her Majesty's Theatre

His Majesty's Theatre is a West End theatre situated in the Haymarket, London, Haymarket in the City of Westminster, London. The building, designed by Charles J. Phipps, was constructed in 1897 for the actor-manager Herbert Beerbohm Tree, who ...

, London, between December 1957 and August 1958. During the run, in April 1958, Carmichael was interviewed for ''Desert Island Discs

''Desert Island Discs'' is a radio programme broadcast on BBC Radio 4. It was first broadcast on the BBC Forces Programme on 29 January 1942.

Each week a guest, called a " castaway" during the programme, is asked to choose eight audio recordin ...

'' by Roy Plomley on the BBC Home Service

The BBC Home Service was a national and regional radio station that broadcast from 1939 until 1967, when it was replaced by BBC Radio 4.

History

1922–1939: Interwar period

Between the early 1920s and the outbreak of World War II, the BBC ...

.

Carmichael once again appeared as Stanley Windrush, the character he portrayed in ''Private's Progress'', in his fifth film with the Boultings, '' I'm All Right Jack'', which was released in August 1959. Several other actors from ''Private's Progress'' also reprised their roles: Price (as Bertram Tracepurcel); Attenborough (as Sidney De Vere Cox) and Terry-Thomas (as Major Hitchcock). A new character was introduced in the film, Peter Sellers

Peter Sellers (born Richard Henry Sellers; 8 September 1925 – 24 July 1980) was an English actor and comedian. He first came to prominence performing in the BBC Radio comedy series ''The Goon Show''. Sellers featured on a number of hit comi ...

as the trade union

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

shop steward

A union representative, union steward, or shop steward is an employee of an organization or company who represents and defends the interests of their fellow employees as a trades/labour union member and official. Rank-and-file members of the un ...

Fred Kite. The film was the highest-grossing at the British box office in 1960 and earned Sellers the award for Best British Actor at the 13th British Academy Film Awards. Although Sellers received most of the plaudits for the film, Carmichael was given good reviews for his role, with ''The Illustrated London News

''The Illustrated London News'', founded by Herbert Ingram and first published on Saturday 14 May 1842, was the world's first illustrated weekly news magazine. The magazine was published weekly for most of its existence, switched to a less freq ...

'' saying he was "in excellent fooling" and "delicious both at work and at play". In 1960 Carmichael appeared in '' School for Scoundrels'', based on Stephen Potter's " gamesmanship" series of books. Appearing alongside him were Terry-Thomas, Alastair Sim and Janette Scott

Thora Janette Scott (born 14 December 1938) is a British retired actress.

Life and career

Scott was born on 14 December 1938 in Morecambe, Lancashire, England. She is the daughter of actors Jimmy Scott and Thora Hird and began her career as ...

. The reviews for the film were not positive, but the actors were praised for their work in it.

The release of ''School for Scoundrels'' was Carmichael's tenth film in five years. Fairclough observes that during the late 1950s and early 1960s, Carmichael began to get a reputation among his colleagues as being difficult to work with. Eric Maschwitz

Albert Eric Maschwitz Order of the British Empire, OBE (10 June 1901 – 27 October 1969), sometimes credited as Holt Marvell, was an English entertainer, writer, editor, broadcaster and broadcasting executive.

Life and work

Born in Edgbaston, ...

, the BBC's Head of Light Entertainment for Television, recorded in an internal memo that Carmichael had given "great difficulty" during negotiations, and concluded that "his head seems to have been a little turned by his success". Some actors had to point out to him that he was "doing a Carmichael" whenever he tried to improve his billing, or upstage his fellow actors, including Derek Nimmo

Derek Robert Nimmo (19 September 1930 – 24 February 1999) was an English character actor, producer and author. He is best remembered for his comedic upper class "silly ass" and clerical roles, including Revd Mervyn Noote in the BBC1 sitcom ...

in 1962, during the filming of '' The Amorous Prawn''. Despite the criticism, Carmichael described the period as "I think the happiest five or six years of my whole career".

In December 1961 Carmichael was appearing in the comedy mystery play '' The Gazebo'' every evening and filming '' Double Bunk'' during the day. The mental and physical toll on him was too much, and he collapsed in the middle of a performance. The show's producer, Harold Fielding, instructed Carmichael to take at least two week's holiday to rest, and he paid for Carmichael and his wife to have a holiday in Switzerland. He returned to the show on 23 December, but he lost his voice during the Boxing Day show and could only complete Act 1. He returned to the show after a few days, but left permanently on 28 January 1962 on his doctor's orders.

Wooster and Wimsey, 1962–1979

Tastes in film changed in the late 1950s and early 1960s, with the new wave of British films moving away from plots centred on the

Tastes in film changed in the late 1950s and early 1960s, with the new wave of British films moving away from plots centred on the upper class

Upper class in modern societies is the social class composed of people who hold the highest social status. Usually, these are the wealthiest members of class society, and wield the greatest political power. According to this view, the upper cla ...

es and the establishment

In sociology and in political science, the term the establishment describes the dominant social group, the elite who control a polity, an organization, or an institution. In the Praxis (process), praxis of wealth and Power (social and politica ...

, to works such as '' Look Back in Anger'', '' Room at the Top'' (both 1959), '' Saturday Night and Sunday Morning'' (1960) and '' The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner'' (1962), where working class

The working class is a subset of employees who are compensated with wage or salary-based contracts, whose exact membership varies from definition to definition. Members of the working class rely primarily upon earnings from wage labour. Most c ...

drama came to the fore. One of the effects of the new movement was a downturn in the number of films that wanted a character like those normally played by Carmichael. He was still being offered some film roles, but all, he said, "were variations on the same old bumbling, accident-prone clot" with which he was becoming increasingly bored.

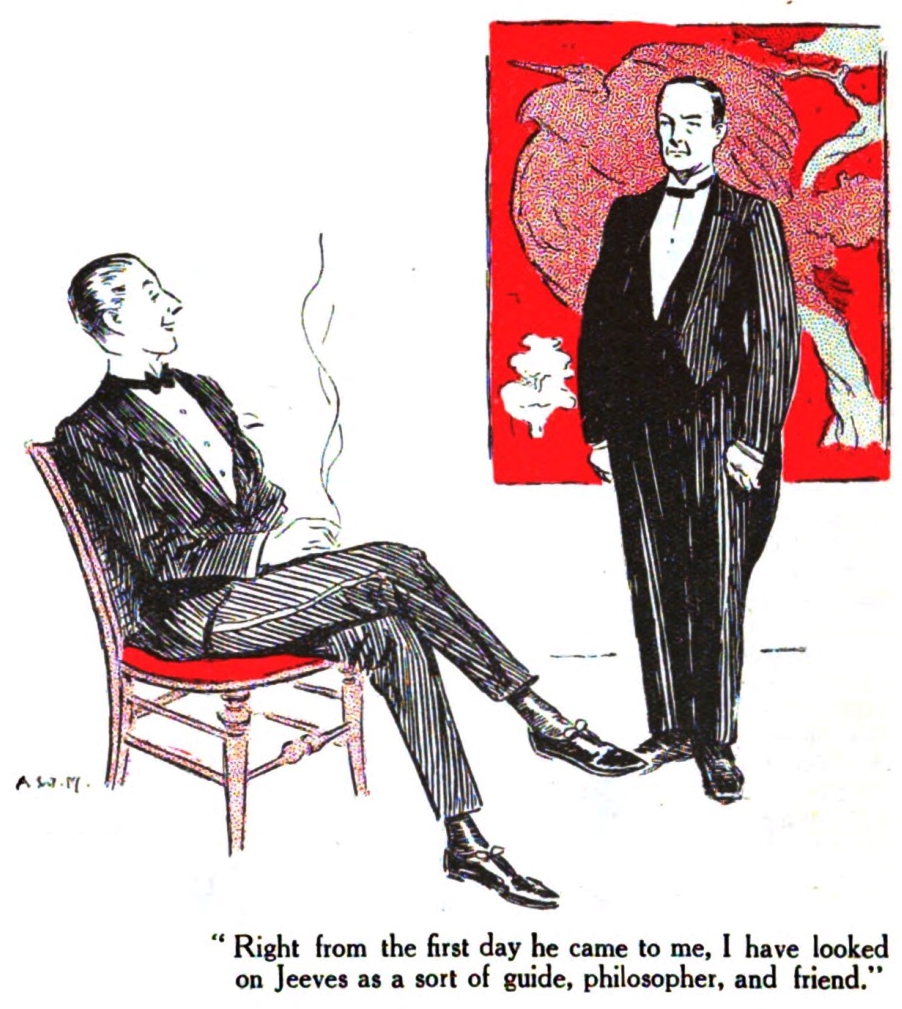

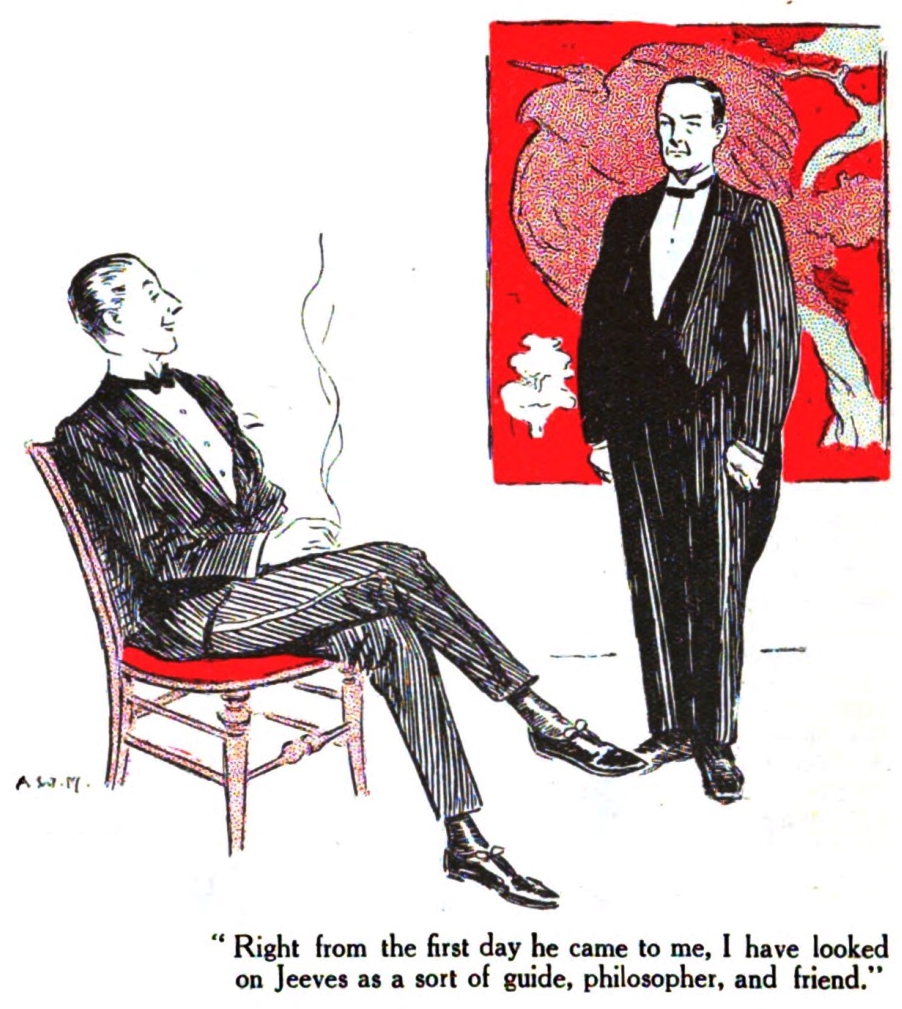

In August 1964 the BBC approached Carmichael to discuss the possibility of his taking the role of Bertie Wooster

Bertram Wilberforce Wooster is a fictional character in the comedic Jeeves stories created by British author P. G. Wodehouse. An amiable English gentleman and one of the "idle rich", Bertie appears alongside his valet, Jeeves, whose intellige ...

—described by Fairclough as "the misadventuring, 1920s upper-class loafer"—for adaptations of the works of P. G. Wodehouse

Sir Pelham Grenville Wodehouse ( ; 15 October 1881 – 14 February 1975) was an English writer and one of the most widely read humorists of the 20th century. His creations include the feather-brained Bertie Wooster and his sagacious valet, Je ...

. He turned it down, as he had agreed to appear on Broadway, taking the lead in a production of the farce

Farce is a comedy that seeks to entertain an audience through situations that are highly exaggerated, extravagant, ridiculous, absurd, and improbable. Farce is also characterized by heavy use of physical comedy, physical humor; the use of delibe ...

'' Boeing-Boeing''. He appeared at the Cort Theatre

The James Earl Jones Theatre, originally the Cort Theatre, is a Broadway theater at 138 48th Street (Manhattan), West 48th Street, between Seventh Avenue (Manhattan), Seventh Avenue and Sixth Avenue, in the Theater District, Manhattan, Theater ...

in February 1965, but the run ended after 23 performances, as the farce was not to the taste of New York audiences. Carmichael was delighted by the early close, as he hated his time in the US and said "I found New York a disturbing, violent city and I disliked it instantly". As soon as he heard the production was to close, he sent a telegram to the BBC to note his availability to play Wooster. Carmichael negotiated a fee of 500 guineas

The guinea (; commonly abbreviated gn., or gns. in plural) was a coin, minted in Great Britain between 1663 and 1814, that contained approximately one-quarter of an ounce of gold. The name came from the Guinea region in West Africa, from where m ...

(£525) per half-hour episode, and assisted in finding the right person for Jeeves

Jeeves (born Reginald Jeeves, nicknamed Reggie) is a fictional character in a series of comedic short stories and novels by English author P. G. Wodehouse. Jeeves is the highly competent valet of a wealthy and idle young Londoner named Bertie W ...

, eventually selecting Dennis Price.

The first series of '' The World of Wooster'' received the Guild of Television Producers and Directors award for best comedy series production of 1965, and the programme ran for three series, broadcast between May 1965 and November 1967, comprising twenty episodes in total. Reviews for Carmichael were positive, with a reviewer in ''The Times'' declaring "''The World of Wooster'' is also a triumph of casting, for Ian Carmichael and Dennis Price are perfect impersonators of two characters who are by no means lay-figures ... They are a priceless pair." A different reviewer pointed out one drawback of the 44-year-old Carmichael's performance: "If we have thought of Bertie Wooster as eternally 22, not far in time from enjoyably wasted university days, Mr. Ian Carmichael opposes our view with a Bertie who is older but hopefully fixed in an inescapable mental youth." The best review, as far as Carmichael and the producer Michael Mills were concerned, was from Wodehouse, who sent a telegram to the BBC:

To the producer and cast of the Jeeves sketches.Wodehouse later reconsidered his opinion and thought Carmichael overacted in the role. Only one of the episodes remains: the others were wiped to reuse the expensive videotape. In September 1970 Carmichael was the lead role in '' Bachelor Father'', a sitcom loosely based on the true story of a single man who fostered twelve children. There were two series—one in 1970, one the following year—and a total of 22 episodes; he negotiated a salary of £1,500 per episode, making him the best-paid actor at the BBC. The media historian

Thank you all for the perfectly wonderful performances. I am simply delighted with it. Bertie and Jeeves are just as I have always imagined them, and every part is played just right.

Bless you!

P. G. Wodehouse

Mark Lewisohn

Mark Lewisohn (born 16 June 1958) is an English historian and biographer. Since the 1980s, he has written many reference books about the Beatles and has worked for EMI, MPL Communications and Apple Corps.

thought that the programme, "although ostensibly a middle-of-the-road family sitcom of no great ambition, came over as a polished and professional piece of work that pleased audiences over two extended series".

Carmichael was one of the driving forces behind the BBC's decision to adapt Dorothy L. Sayers's Lord Peter Wimsey

Lord Peter Death Bredon Wimsey (later 17th Duke of Denver) is the fictional protagonist in a series of detective novels and short stories by Dorothy L. Sayers (and their continuation by Jill Paton Walsh). A amateur, dilettante who solves myst ...

stories for television. He first had the idea of appearing as Wimsey in 1966, but various factors—including financing, Carmichael's association with Bertie Wooster in the public's eye and difficulty obtaining the rights—delayed the project. By January 1971, however, they were able to start filming the first programme, ''Clouds of Witness

''Clouds of Witness'' is a 1926 mystery novel by Dorothy L. Sayers, the second in her series featuring Lord Peter Wimsey. In the United States the novel was first published in 1927 under the title ''Clouds of Witnesses''.

It was adapted for ...

'', which was broadcast in 1972 in five parts. This was followed by '' The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club'', '' Murder Must Advertise'', '' The Nine Tailors'' and '' The Five Red Herrings'' between February 1973 and August 1975. Richard Last, writing in ''The Daily Telegraph'' thought Carmichael was "an inspired piece of casting. ... he has exactly the right outward touch of aristocratic frivolity but more than the ability to suggest the steel underneath". Clive James

Clive James (born Vivian Leopold James; 7 October 1939 – 24 November 2019) was an Australian critic, journalist, broadcaster, writer and lyricist who lived and worked in the United Kingdom from 1962 until his death in 2019.The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. First published in 1791, it is the world's oldest Sunday newspaper.

In 1993 it was acquired by Guardian Media Group Limited, and operated as a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' ...

'', described Carmichael as "an extremely clever actor", and thought he was "turning in one of those thespian efforts which seem easy at the time but which in retrospect are found to have been the ideal embodiment of the written character". Carmichael went on to play Wimsey on BBC Radio 4

BBC Radio 4 is a British national radio station owned and operated by the BBC. The station replaced the BBC Home Service on 30 September 1967 and broadcasts a wide variety of spoken-word programmes from the BBC's headquarters at Broadcasti ...

, recording nine adaptations with Peter Jones as Mervyn Bunter, Wimsey's valet.

In 1979 Carmichael appeared in ''The Lady Vanishes

''The Lady Vanishes'' is a 1938 British Mystery film, mystery Thriller (genre), thriller film directed by Alfred Hitchcock, starring Margaret Lockwood and Michael Redgrave. Written by Sidney Gilliat and Frank Launder, based on the 1936 novel '' ...

'', which starred Elliott Gould

Elliott Gould (; né Goldstein; born August 29, 1938) is an American actor.

Gould's breakthrough role was in the film ''Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice'' (1969), for which he received a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor. The ...

and Cybill Shepherd

Cybill Lynne Shepherd (born February 18, 1950) is an American actress, singer and former model. Her film debut and breakthrough role came as Jacy Farrow in Peter Bogdanovich's coming-of-age drama '' The Last Picture Show'' (1971) alongside Jef ...

; the film was a remake of Alfred Hitchcock

Sir Alfred Joseph Hitchcock (13 August 1899 – 29 April 1980) was an English film director. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in the history of cinema. In a career spanning six decades, he directed over 50 featu ...

's 1938 film of the same name. Carmichael appeared as Caldicott alongside Arthur Lowe's character Charters, two cricket-obsessed English gentlemen; the roles were played in the original by Naunton Wayne

Naunton Wayne (born Henry Wayne Davies, 22 June 1901 – 17 November 1970), was a Welsh character actor, born in Pontypridd, Glamorgan, Wales. He was educated at Clifton College. His name was changed by deed poll#Use for changing name, deed po ...

and Basil Radford

Arthur Basil RadfordAdam Greaves, "Radford, (Arthur) Basil (1897–1952)", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, May 201available online Retrieved 3 August 2020. (25 June 189720 October 1952) was an English chara ...

. The journalist Patrick Humphries, while describing the film as "lamentable", thought that only Carmichael and Lowe "emerge with any credibility". Carmichael was interviewed on ''Desert Island Discs'' for a second time in June 1979.

Semi-retirement, 1979–2009

In 1979 Carmichael published his autobiography ''Will the Real Ian Carmichael ...'', which marked what Fairclough calls his "semi-retirement" in Yorkshire. He continued to work periodically, including providing the voice for Rat in the 1983 film ''The Wind in the Willows

''The Wind in the Willows'' is a children's novel by the British novelist Kenneth Grahame, first published in 1908. It details the story of Mole, Ratty, and Badger as they try to help Mr. Toad, after he becomes obsessed with motorcars and get ...

'' and as the narrator for the television series of the same name between 1984 and 1990. He revisited the works of Wodehouse in the late 1980s and early 1990s, providing the voice of Galahad Threepwood for two radio productions, '' Pigs Have Wings'' and '' Galahad at Blandings''.

In 1992 and 1993 he played Sir James Menzies in two series of '' Strathblair'', a BBC family drama set in 1950 broadcast on Sunday evenings. He undertook his last stage role in June 1995, playing Sir Peter Teazle in Richard Brinsley Sheridan

Richard Brinsley Butler Sheridan (30 October 17517 July 1816) was an Anglo-Irish playwright, writer and Whig politician who sat in the British House of Commons from 1780 to 1812, representing the constituencies of Stafford, Westminster and I ...

's '' The School for Scandal'' at the Chichester Festival Theatre

Chichester Festival Theatre is a theatre and Grade II* listed building situated in Oaklands Park in the city of Chichester, West Sussex, England. Designed by Philip Powell and Hidalgo Moya, it was opened by its founder Leslie Evershed-Mart ...

. From 2003 he took his final role: that of T. J. Middleditch in the ITV hospital drama series ''The Royal

''The Royal'' is a British period medical drama, produced by Yorkshire Television (later part of ITV Studios), and broadcast on ITV from 2003 until its cancellation in 2011. The series is set in the 1960s and focuses on the lives of the st ...

''. He continued filming with ''The Royal'' until 2009.

Personal life

In late March 1941, when Carmichael's regiment was posted to Whitby he met "Pym"—Jean Pyman Maclean—who he described as "blonde, just eighteen, five feet six, sensationally pretty and a beautiful dancer"; he thought her personality was "warm ... genuine. There was an innocence about her, an unsophistication that disarmed even the most worldly". The couple became engaged in May 1942 and married on 6 October 1943; they had two daughters, Lee (born in 1946) and Sally (born in 1949). Pym died of cancer in 1983. In 1984 Carmichael recorded a series of short stories for the BBC; the programmes were produced by Kate Fenton. They began a relationship and she left the BBC in 1985 and moved in with him in the Esk Valley, nearWhitby

Whitby is a seaside town, port and civil parish in North Yorkshire, England. It is on the Yorkshire Coast at the mouth of the River Esk, North Yorkshire, River Esk and has a maritime, mineral and tourist economy.

From the Middle Ages, Whitby ...

. They were married in July 1992. Carmichael enjoyed playing and watching cricket, and listed it as one of this interests in ''Who's Who

A Who's Who (or Who Is Who) is a reference work consisting of biographical entries of notable people in a particular field. The oldest and best-known is the annual publication ''Who's Who (UK), Who's Who'', a reference work on contemporary promin ...

''. He was a member of the Lord's Taverners cricket charity from 1956 until October 1976, and would relax on film sets playing a casual game with other members of the cast and crew, a practice he was introduced to by the Boulting brothers. He was also a member of the Marylebone Cricket Club

The Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) is a cricket club founded in 1787 and based since 1814 at Lord's, Lord's Cricket Ground, which it owns, in St John's Wood, London, England. The club was the governing body of cricket from 1788 to 1989 and retain ...

.

In 2003 Carmichael was appointed OBE for services to drama. He died on 5 February 2010 of a pulmonary embolism

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a blockage of an pulmonary artery, artery in the lungs by a substance that has moved from elsewhere in the body through the bloodstream (embolism). Symptoms of a PE may include dyspnea, shortness of breath, chest pain ...

.

Screen persona and technique

Carmichael learned much of his technique from the thirty-week tour of ''The Lilac Domino'' he undertook in the late 1940s, where he appeared opposite the comic actor Leo Franklyn. Carmichael acknowledged the credit for his development as a light comic actor went "in its entirety to the training, coaxing and encouragement of ... Franklyn", who "showed me how to time my laughs and how to play an audience". Carmichael's experience inrevue

A revue is a type of multi-act popular theatre, theatrical entertainment that combines music, dance, and sketch comedy, sketches. The revue has its roots in 19th century popular entertainment and melodrama but grew into a substantial cultural pre ...

helped when he worked in a dramatic play; his experience in getting a character across to an audience quickly in a short sketch showed him that "it is very important to establish a comedy character as soon as possible. Your whole performance may depend on this being done".

Carmichael polished his performances through extensive rehearsals and training. The screenwriter

A screenwriter (also called scriptwriter, scribe, or scenarist) is a person who practices the craft of writing for visual mass media, known as screenwriting. These can include short films, feature-length films, television programs, television ...

Paul Dehn acknowledges the effort and discipline needed by Carmichael to achieve a polished feel to his act, describing how Carmichael would "slave for hours to perfect one stumble on a stairway and, having got it, ... ouldmake it seem effortless thereafter". Jennings considers much of Carmichael's seemingly effortless light touch "was built on a hugely disciplined and virtuosic technique". Carmichael's choice of comedy was character-, rather than situation-based and when the film or play generated its atmosphere from normal, recognisable aspects of life. He selected his work projects carefully and became involved in the development and production side as closely as possible, or initiated the project himself.

The image he portrayed in many of his works was summarised by one obituarist as "the affable, archetypal silly ass Englishman" with a "wide-eyed boyish grin, bemused courtesy and hapless, trusting manner". He became somewhat typecast with the character, but audiences liked him in the role, and "he polished this persona with great care", according to his obituarist in ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a British daily broadsheet conservative newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed in the United Kingdom and internationally. It was found ...

'', even though he tired of playing the role so often. One of the attractions for the public was that he played his parts to get the audience's sympathy for the character, but with a measure of dignity that viewers could relate to. During Carmichael's semi-retirement, the Boulting brothers told him that they had not shown the range of his talents, and that "perhaps they should not virtually have confined him to the playing of twerps

''TWERPS'' (''The World's Easiest Role-Playing System'') is a minimalist role-playing game (RPG) originally created by Reindeer Games in 1987 (whose sole product was the ''TWERPS'' line) and distributed by Lou Zocchi, Gamescience. Presented as ...

". When he took the role of Wimsey—the intelligent, cultured and effective investigator—the critic Nancy Banks-Smith

Nancy Banks-Smith (born 1929) is a British TV critic, television and radio critic, who spent most of her career writing for ''The Guardian''.

Life and career

Born in Manchester and raised in a pub, she was educated at Roedean School.

Banks-Smith ...

wrote that "it was high time that Ian Carmichael was given the opportunity to look intelligent".

Notes and references

Notes

References

Sources

Books

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Journals and magazines

* *News

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Websites

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *London Gazette

* * *External links

* *BBC Humber feature on Ian Carmichael

{{DEFAULTSORT:Carmichael, Ian 1920 births 2010 deaths Military personnel from Kingston upon Hull British Army personnel of World War II English male film actors English male radio actors English male stage actors English male television actors Officers of the Order of the British Empire People educated at Bromsgrove School Male actors from Kingston upon Hull Royal Armoured Corps officers Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst Alumni of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art People educated at Scarborough College 22nd Dragoons officers