Husserl on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

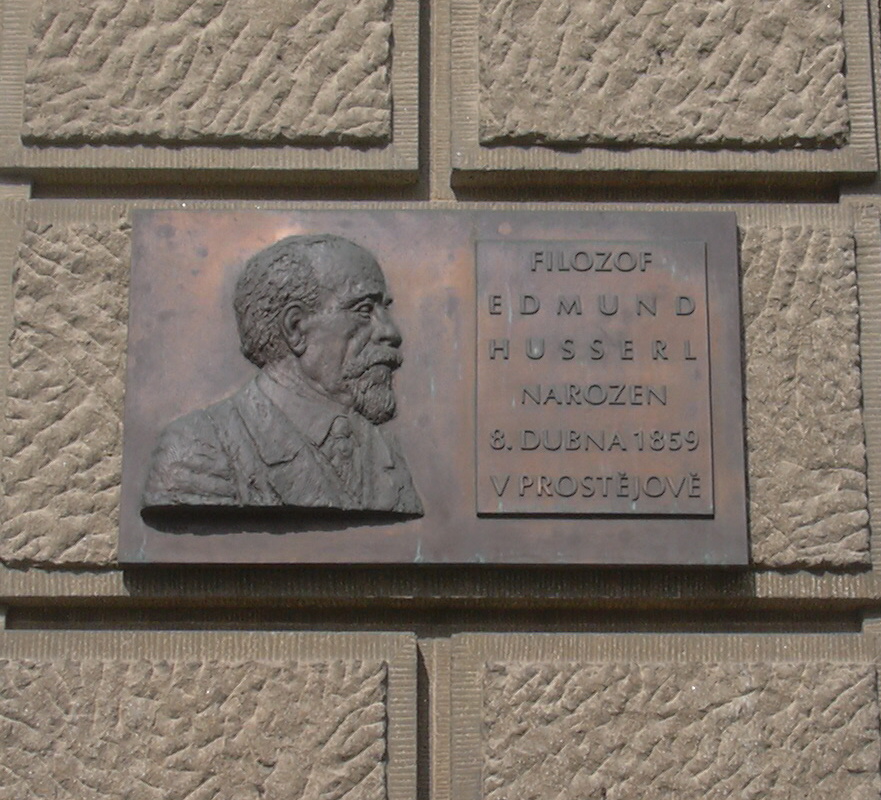

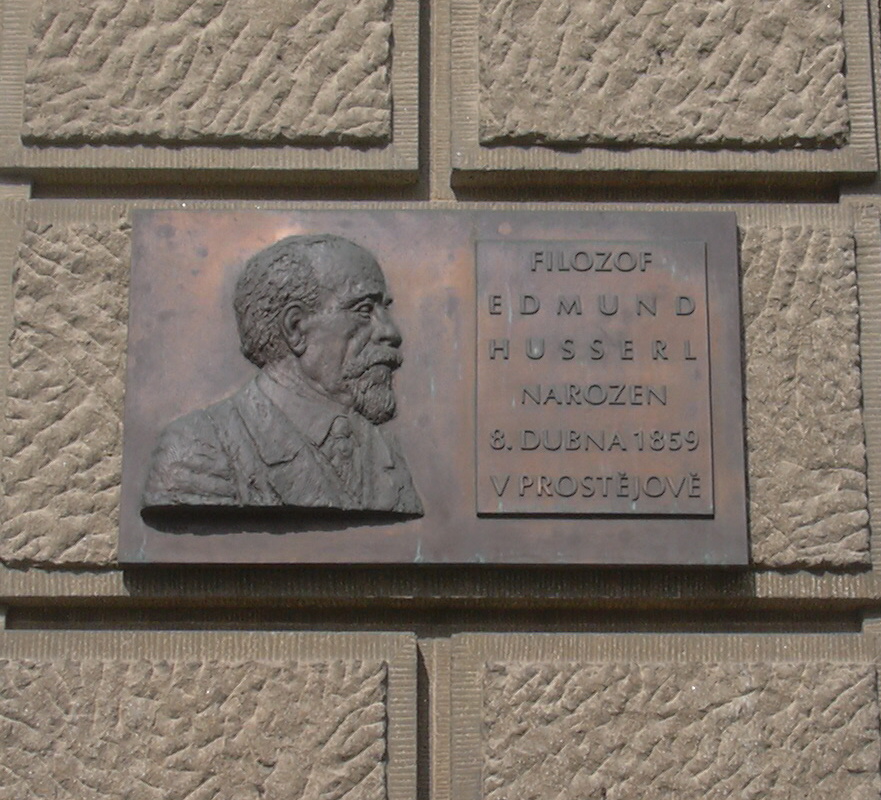

Edmund Gustav Albrecht Husserl (; 8 April 1859 – 27 April 1938) was an Austrian-German philosopher and mathematician who established the school of

Following his marriage, Husserl began his long teaching career in philosophy. He started in 1887 as a ''

Following his marriage, Husserl began his long teaching career in philosophy. He started in 1887 as a '' Later, Husserl lectured at Prague in 1935 and Vienna in 1936, which resulted in a very differently styled work that, while innovative, is no less problematic: ''Die Krisis'' (Belgrade 1936). Husserl describes here the cultural crisis gripping Europe, then approaches a philosophy of history, discussing

Later, Husserl lectured at Prague in 1935 and Vienna in 1936, which resulted in a very differently styled work that, while innovative, is no less problematic: ''Die Krisis'' (Belgrade 1936). Husserl describes here the cultural crisis gripping Europe, then approaches a philosophy of history, discussing

Paul Ricœur has translated many works of Husserl into French and has also written many of his own studies of the philosopher. Among other works, Ricœur employed phenomenology in his '' Freud and Philosophy'' (1965).

Paul Ricœur has translated many works of Husserl into French and has also written many of his own studies of the philosopher. Among other works, Ricœur employed phenomenology in his '' Freud and Philosophy'' (1965).

''Husserl''

London: Routledge. * Zahavi, Dan, 2003. ''Husserl's Phenomenology''. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Husserl-Archives Leuven

the main Husserl-Archive in

Husserliana: Edmund Husserl Gesammelte Werke

the ongoing critical edition of Husserl's works.

Husserliana: Materialien

edition for lectures and shorter works.

Edmund Husserl Collected Works

English translation of Husserl's works.

Husserl-Archives

at the

Husserl-Archives Freiburg

at the ''

Papers on Edmund Husserl

by Barry Smith

English translation of "Vienna Lecture" (1935): "Philosophy and the Crisis of European Humanity"

The Husserl Page by Bob Sandmeyer

Includes a number of online texts in German and English.

Husserl.net

open content project. *

Resource guide on Husserl's logic and formal ontology, with annotated bibliography.

The Husserl Circle.

Cartesian Meditations

in

''Ideas'', Part I

in

Edmund Husserl on the Open Commons of Phenomenology

Complete bibliography and links to all German texts, including ''Husserliana'' vols. I–XXVIII {{DEFAULTSORT:Husserl, Edmund 1859 births 1938 deaths 19th-century Austrian male writers 19th-century Austrian writers 19th-century German philosophers 19th-century German writers 19th-century German male writers 20th-century Austrian male writers 20th-century Austrian philosophers 20th-century German philosophers 20th-century German writers 19th-century Austrian Jews Austrian logicians Austrian Lutherans 19th-century Austrian philosophers Converts to Lutheranism from Judaism Descartes scholars Epistemologists German logicians German Lutherans German male non-fiction writers Humboldt University of Berlin alumni Leipzig University alumni Lutheran philosophers Jewish philosophers Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg alumni Metaphysicians Ontologists Writers from Prostějov People from the Margraviate of Moravia Phenomenologists Philosophers of culture German philosophers of education Philosophers of language Philosophers of logic Philosophers of mathematics Philosophers of mind Philosophers of psychology Platonists Trope theorists Academic staff of the University of Freiburg Academic staff of the University of Göttingen University of Vienna alumni Corresponding fellows of the British Academy Moravian-German people

phenomenology

Phenomenology may refer to:

Art

* Phenomenology (architecture), based on the experience of building materials and their sensory properties

Philosophy

* Phenomenology (Peirce), a branch of philosophy according to Charles Sanders Peirce (1839� ...

.

In his early work, he elaborated critiques of historicism

Historicism is an approach to explaining the existence of phenomena, especially social and cultural practices (including ideas and beliefs), by studying the process or history by which they came about. The term is widely used in philosophy, ant ...

and of psychologism

Psychologism is a family of philosophical positions, according to which certain psychological facts, laws, or entities play a central role in grounding or explaining certain non-psychological facts, laws, or entities. The word was coined by Joh ...

in logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

based on analyses of intentionality

Intentionality is the mental ability to refer to or represent something. Sometimes regarded as the ''mark of the mental'', it is found in mental states like perceptions, beliefs or desires. For example, the perception of a tree has intentionality ...

. In his mature work, he sought to develop a systematic foundational science based on the so-called phenomenological reduction. Arguing that transcendental consciousness sets the limits of all possible knowledge, Husserl redefined phenomenology as a transcendental-idealist philosophy. Husserl's thought profoundly influenced 20th-century philosophy

Contemporary philosophy is the present period in the history of Western philosophy beginning at the early 20th century with the increasing professionalization of the discipline and the rise of Analytic philosophy, analytic and continental philosop ...

, and he remains a notable figure in contemporary philosophy and beyond.

Husserl studied mathematics, taught by Karl Weierstrass

Karl Theodor Wilhelm Weierstrass (; ; 31 October 1815 – 19 February 1897) was a German mathematician often cited as the " father of modern analysis". Despite leaving university without a degree, he studied mathematics and trained as a school t ...

and Leo Königsberger, and philosophy taught by Franz Brentano

Franz Clemens Honoratus Hermann Josef Brentano (; ; 16 January 1838 – 17 March 1917) was a German philosopher and psychologist. His 1874 '' Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint'', considered his magnum opus, is credited with having reintrod ...

and Carl Stumpf. He taught philosophy as a ''Privatdozent

''Privatdozent'' (for men) or ''Privatdozentin'' (for women), abbreviated PD, P.D. or Priv.-Doz., is an academic title conferred at some European universities, especially in German-speaking countries, to someone who holds certain formal qualifi ...

'' at Halle from 1887, then as professor, first at Göttingen

Göttingen (, ; ; ) is a college town, university city in Lower Saxony, central Germany, the Capital (political), capital of Göttingen (district), the eponymous district. The River Leine runs through it. According to the 2022 German census, t ...

from 1901, then at Freiburg

Freiburg im Breisgau or simply Freiburg is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, fourth-largest city of the German state of Baden-Württemberg after Stuttgart, Mannheim and Karlsruhe. Its built-up area has a population of abou ...

from 1916 until he retired in 1928, after which he remained highly productive. In 1933, under racial laws of the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

, Husserl was banned from using the library of the University of Freiburg

The University of Freiburg (colloquially ), officially the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg (), is a public university, public research university located in Freiburg im Breisgau, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. The university was founded in 1 ...

due to his Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

family background and months later resigned from the Deutsche Akademie

The Academy for the Scholarly Research and Fostering of Germandom (''die Akademie zur Wissenschaftlichen Erforschung und Pflege des Deutschtums''), or German Academy (''die Deutsche Akademie'', ), was a German cultural institute founded in 1925 at ...

. Following an illness, he died in Freiburg

Freiburg im Breisgau or simply Freiburg is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, fourth-largest city of the German state of Baden-Württemberg after Stuttgart, Mannheim and Karlsruhe. Its built-up area has a population of abou ...

in 1938.

Life and career

Youth and education

Husserl was born in 1859 in Proßnitz in theMargraviate of Moravia

The Margraviate of Moravia (; ) was one of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown within the Holy Roman Empire and then Austria-Hungary, existing from 1182 to 1918. It was officially administered by a margrave in cooperation with a provincial diet. I ...

in the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

(today Prostějov

Prostějov (; ) is a city in the Olomouc Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 43,000 inhabitants. The city is historically known for its fashion industry. The historic city centre is well preserved and is protected as an urban monument zo ...

in the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, also known as Czechia, and historically known as Bohemia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. The country is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the south ...

). He was born into a Jewish family, the second of four children. His father was a milliner. His childhood was spent in Prostějov, where he attended the secular primary school. Then Husserl traveled to Vienna to study at the '' Realgymnasium'' there, followed next by the Staatsgymnasium in Olmütz.Joseph J. Kockelmans, "Biographical Note" per Edmund Husserl, at 17–20, in his edited ''Phenomenology. The Philosophy of Edmund Husserl and Its Interpretation'' (Garden City NY: Doubleday Anchor, 1967).

At the University of Leipzig

Leipzig University (), in Leipzig in Saxony, Germany, is one of the world's oldest universities and the second-oldest university (by consecutive years of existence) in Germany. The university was founded on 2 December 1409 by Frederick I, Electo ...

from 1876 to 1878, Husserl studied mathematics, physics, and astronomy. At Leipzig, he was inspired by philosophy lectures given by Wilhelm Wundt

Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt (; ; 16 August 1832 – 31 August 1920) was a German physiologist, philosopher, and professor, one of the fathers of modern psychology. Wundt, who distinguished psychology as a science from philosophy and biology, was t ...

, one of the founders of modern psychology. Then he moved to the Frederick William University of Berlin (the present-day Humboldt University of Berlin

The Humboldt University of Berlin (, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin, Germany.

The university was established by Frederick William III on the initiative of Wilhelm von Humbol ...

) in 1878, where he continued his study of mathematics under Leopold Kronecker

Leopold Kronecker (; 7 December 1823 – 29 December 1891) was a German mathematician who worked on number theory, abstract algebra and logic, and criticized Georg Cantor's work on set theory. Heinrich Weber quoted Kronecker

as having said, ...

and Karl Weierstrass

Karl Theodor Wilhelm Weierstrass (; ; 31 October 1815 – 19 February 1897) was a German mathematician often cited as the " father of modern analysis". Despite leaving university without a degree, he studied mathematics and trained as a school t ...

. In Berlin, he found a mentor in Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk Tomáš () is a Czech name, Czech and Slovak name, Slovak given name, equivalent to the name Thomas (name), Thomas. Tomáš is also a surname (feminine: Tomášová). Notable people with the name include:

Given name Sport

*Tomáš Berdych (born 198 ...

(then a former philosophy student of Franz Brentano

Franz Clemens Honoratus Hermann Josef Brentano (; ; 16 January 1838 – 17 March 1917) was a German philosopher and psychologist. His 1874 '' Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint'', considered his magnum opus, is credited with having reintrod ...

and later the first president of Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

) and attended Friedrich Paulsen

Friedrich Paulsen (; ; July 16, 1846 – August 14, 1908) was a German Neo-Kantian philosopher and educator.

Biography

He was born at Langenhorn ( Schleswig) and educated at the Gymnasium Christianeum, the University of Erlangen, and the Uni ...

's philosophy lectures. In 1881, he left for the University of Vienna

The University of Vienna (, ) is a public university, public research university in Vienna, Austria. Founded by Rudolf IV, Duke of Austria, Duke Rudolph IV in 1365, it is the oldest university in the German-speaking world and among the largest ...

to complete his mathematics studies under the supervision of Leo Königsberger (a former student of Weierstrass). At Vienna in 1883, he obtained his PhD with the work ''Beiträge zur Variationsrechnung'' (''Contributions to the Calculus of variations

The calculus of variations (or variational calculus) is a field of mathematical analysis that uses variations, which are small changes in Function (mathematics), functions

and functional (mathematics), functionals, to find maxima and minima of f ...

'').

Evidently, as a result of his becoming familiar with the New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

during his twenties, Husserl asked to be baptized into the Lutheran Church

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched the Reformation in 15 ...

in 1886. Husserl's father, Adolf, had died in 1884. Herbert Spiegelberg writes, "While outward religious practice never entered his life any more than it did that of most academic scholars of the time, his mind remained open for the religious phenomenon as for any other genuine experience." At times Husserl saw his goal as one of moral "renewal". Although a steadfast proponent of a radical and rational ''autonomy'' in all things, Husserl could also speak "about his vocation and even about his mission under God's will to find new ways for philosophy and science," observes Spiegelberg.

Following his PhD in mathematics, Husserl returned to Berlin to work as the assistant to Karl Weierstrass

Karl Theodor Wilhelm Weierstrass (; ; 31 October 1815 – 19 February 1897) was a German mathematician often cited as the " father of modern analysis". Despite leaving university without a degree, he studied mathematics and trained as a school t ...

. Yet already Husserl had felt the desire to pursue philosophy. Then Weierstrass became very ill. Husserl became free to return to Vienna, where, after serving a short military duty, he devoted his attention to philosophy. In 1884, at the University of Vienna

The University of Vienna (, ) is a public university, public research university in Vienna, Austria. Founded by Rudolf IV, Duke of Austria, Duke Rudolph IV in 1365, it is the oldest university in the German-speaking world and among the largest ...

he attended the lectures of Franz Brentano

Franz Clemens Honoratus Hermann Josef Brentano (; ; 16 January 1838 – 17 March 1917) was a German philosopher and psychologist. His 1874 '' Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint'', considered his magnum opus, is credited with having reintrod ...

on philosophy and philosophical psychology. Brentano introduced him to the writings of Bernard Bolzano

Bernard Bolzano (, ; ; ; born Bernardus Placidus Johann Nepomuk Bolzano; 5 October 1781 – 18 December 1848) was a Bohemian mathematician, logician, philosopher, theologian and Catholic priest of Italian extraction, also known for his liberal ...

, Hermann Lotze, J. Stuart Mill, and David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism. Beg ...

. Husserl was so impressed by Brentano that he decided to dedicate his life to philosophy; indeed, Franz Brentano is often credited as being his most important influence, e.g., with regard to intentionality

Intentionality is the mental ability to refer to or represent something. Sometimes regarded as the ''mark of the mental'', it is found in mental states like perceptions, beliefs or desires. For example, the perception of a tree has intentionality ...

. Following academic advice, two years later in 1886 Husserl followed Carl Stumpf, a former student of Brentano, to the University of Halle

Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (), also referred to as MLU, is a public research university in the cities of Halle and Wittenberg. It is the largest and oldest university in the German state of Saxony-Anhalt. MLU offers German and i ...

, seeking to obtain his habilitation

Habilitation is the highest university degree, or the procedure by which it is achieved, in Germany, France, Italy, Poland and some other European and non-English-speaking countries. The candidate fulfills a university's set criteria of excelle ...

which would qualify him to teach at the university level. There, under Stumpf's supervision, he wrote his habilitation thesis, ''Über den Begriff der Zahl'' (''On the Concept of Number''), in 1887, which would serve later as the basis for his first important work, '' Philosophie der Arithmetik'' (1891).

In 1887, Husserl married Malvine Steinschneider, a union that would last over fifty years. In 1892, their daughter Elizabeth was born, in 1893 their son Gerhart Gerhart is a surname and given name. Notable people with the name include:

As a given name

* Gerhart Baum (1932–2025), German lawyer and politician, Federal Minister of the Interior

* Gerhart Eisler (1897–1968), German communist politician

* ...

, and in 1894 their son Wolfgang. Elizabeth would marry in 1922, and Gerhart in 1923; Wolfgang, however, became a casualty of the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. Gerhart would become a philosopher of law, contributing to the subject of comparative law

Comparative law is the study of differences and similarities between the law and legal systems of different countries. More specifically, it involves the study of the different legal systems (or "families") in existence around the world, includ ...

, teaching in the United States and after the war in Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

.

Professor of philosophy

Following his marriage, Husserl began his long teaching career in philosophy. He started in 1887 as a ''

Following his marriage, Husserl began his long teaching career in philosophy. He started in 1887 as a ''Privatdozent

''Privatdozent'' (for men) or ''Privatdozentin'' (for women), abbreviated PD, P.D. or Priv.-Doz., is an academic title conferred at some European universities, especially in German-speaking countries, to someone who holds certain formal qualifi ...

'' at the University of Halle

Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (), also referred to as MLU, is a public research university in the cities of Halle and Wittenberg. It is the largest and oldest university in the German state of Saxony-Anhalt. MLU offers German and i ...

. In 1891, he published his '' Philosophie der Arithmetik. Psychologische und logische Untersuchungen'' which, drawing on his prior studies in mathematics and philosophy, proposed a psychological context as the basis of mathematics. It drew the adverse notice of Gottlob Frege

Friedrich Ludwig Gottlob Frege (; ; 8 November 1848 – 26 July 1925) was a German philosopher, logician, and mathematician. He was a mathematics professor at the University of Jena, and is understood by many to be the father of analytic philos ...

, who criticized its psychologism

Psychologism is a family of philosophical positions, according to which certain psychological facts, laws, or entities play a central role in grounding or explaining certain non-psychological facts, laws, or entities. The word was coined by Joh ...

.

In 1901, Husserl with his family moved to the University of Göttingen

The University of Göttingen, officially the Georg August University of Göttingen (, commonly referred to as Georgia Augusta), is a Public university, public research university in the city of Göttingen, Lower Saxony, Germany. Founded in 1734 ...

, where he taught as ''extraordinarius professor''. Just prior to this, a major work of his, ''Logische Untersuchungen'' (Halle, 1900–1901), was published. Volume One contains seasoned reflections on "pure logic" in which he carefully refutes "psychologism". This work was well received and became the subject of a seminar given by Wilhelm Dilthey

Wilhelm Dilthey (; ; 19 November 1833 – 1 October 1911) was a German historian, psychologist, sociologist, and hermeneutic philosopher, who held Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's Chair in Philosophy at the University of Berlin. As a polymathi ...

; Husserl in 1905 traveled to Berlin to visit Dilthey. Two years later, in Italy, he paid a visit to Franz Brentano, his inspiring old teacher, and to the mathematician Constantin Carathéodory

Constantin Carathéodory (; 13 September 1873 – 2 February 1950) was a Greeks, Greek mathematician who spent most of his professional career in Germany. He made significant contributions to real and complex analysis, the calculus of variations, ...

. Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, et ...

and Descartes were also now influencing his thought. In 1910, he became joint editor of the journal ''Logos''. During this period, Husserl had delivered lectures on ''internal time consciousness'', which several decades later his former students Edith Stein

Edith Stein (; ; in religion Teresa Benedicta of the Cross; 12 October 1891 – 9 August 1942) was a German philosopher who converted to Catholic Church, Catholicism and became a Discalced Carmelites, Discalced Carmelite nun. Edith Stein was mu ...

and Martin Heidegger

Martin Heidegger (; 26 September 1889 – 26 May 1976) was a German philosopher known for contributions to Phenomenology (philosophy), phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism. His work covers a range of topics including metaphysics, art ...

edited for publication.

In 1912, in Freiburg, the journal ''Jahrbuch für Philosophie und Phänomenologische Forschung'' ("Yearbook for Philosophy and Phenomenological Research") was founded by Husserl and his school, which published articles of their phenomenological movement from 1913 to 1930. His important work ''Ideen'' was published in its first issue (Vol. 1, Issue 1, 1913). Before beginning ''Ideen'', Husserl's thought had reached the stage where "each subject is 'presented' to itself, and to each all others are 'presentiated' (''Vergegenwärtigung''), not as parts of nature but as pure consciousness". ''Ideen'' advanced his transition to a "transcendental interpretation" of phenomenology, a view later criticized by, among others, Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was a French philosopher, playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and literary criticism, literary critic, considered a leading figure in 20th ...

. In ''Ideen'' Paul Ricœur sees the development of Husserl's thought as leading "from the psychological cogito to the transcendental cogito". As phenomenology further evolves, it leads (when viewed from another vantage point in Husserl's 'labyrinth') to " transcendental subjectivity". Also in ''Ideen'' Husserl explicitly elaborates the phenomenological and eidetic reductions. Ivan Ilyin and Karl Jaspers

Karl Theodor Jaspers (; ; 23 February 1883 – 26 February 1969) was a German-Swiss psychiatrist and philosopher who had a strong influence on modern theology, psychiatry, and philosophy. His 1913 work ''General Psychopathology'' influenced many ...

visited Husserl at Göttingen.

In October 1914, both his sons were sent to fight on the Western Front of World War I, and the following year, one of them, Wolfgang Husserl, was badly injured. On 8 March 1916, on the battlefield of Verdun

Verdun ( , ; ; ; official name before 1970: Verdun-sur-Meuse) is a city in the Meuse (department), Meuse departments of France, department in Grand Est, northeastern France. It is an arrondissement of the department.

In 843, the Treaty of V ...

, Wolfgang was killed in action. The next year, his other son, Gerhart Husserl was wounded in the war but survived. His own mother, Julia, died. In November 1917, one of his outstanding students and later a noted philosophy professor in his own right, Adolf Reinach, was killed in the war while serving in Flanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

.

Husserl had transferred in 1916 to the University of Freiburg

The University of Freiburg (colloquially ), officially the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg (), is a public university, public research university located in Freiburg im Breisgau, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. The university was founded in 1 ...

(in Freiburg im Breisgau

Freiburg im Breisgau or simply Freiburg is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, fourth-largest city of the German state of Baden-Württemberg after Stuttgart, Mannheim and Karlsruhe. Its built-up area has a population of abou ...

) where he continued bringing his work in philosophy to fruition, now as a full professor. Edith Stein

Edith Stein (; ; in religion Teresa Benedicta of the Cross; 12 October 1891 – 9 August 1942) was a German philosopher who converted to Catholic Church, Catholicism and became a Discalced Carmelites, Discalced Carmelite nun. Edith Stein was mu ...

served as his personal assistant during his first few years in Freiburg, followed later by Martin Heidegger

Martin Heidegger (; 26 September 1889 – 26 May 1976) was a German philosopher known for contributions to Phenomenology (philosophy), phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism. His work covers a range of topics including metaphysics, art ...

from 1920 to 1923. The mathematician Hermann Weyl

Hermann Klaus Hugo Weyl (; ; 9 November 1885 – 8 December 1955) was a German mathematician, theoretical physicist, logician and philosopher. Although much of his working life was spent in Zürich, Switzerland, and then Princeton, New Jersey, ...

began corresponding with him in 1918. Husserl gave four lectures on the phenomenological method at University College London

University College London (Trade name, branded as UCL) is a Public university, public research university in London, England. It is a Member institutions of the University of London, member institution of the Federal university, federal Uni ...

in 1922. The University of Berlin

The Humboldt University of Berlin (, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin, Germany.

The university was established by Frederick William III on the initiative of Wilhelm von Humbol ...

in 1923 called on him to relocate there, but he declined the offer. In 1926, Heidegger dedicated his book ''Sein und Zeit'' (''Being and Time

''Being and Time'' () is the 1927 ''magnum opus'' of German philosopher Martin Heidegger and a key document of existentialism. ''Being and Time'' had a notable impact on subsequent philosophy, literary theory and many other fields. Though controv ...

'') to him "in grateful respect and friendship." Husserl remained in his professorship at Freiburg until he requested retirement, teaching his last class on 25 July 1928. A ''Festschrift

In academia, a ''Festschrift'' (; plural, ''Festschriften'' ) is a book honoring a respected person, especially an academic, and presented during their lifetime. It generally takes the form of an edited volume, containing contributions from the h ...

'' to celebrate his seventieth birthday was presented to him on 8 April 1929.

Despite retirement, Husserl gave several notable lectures. The first, at Paris in 1929, led to '' Méditations cartésiennes'' (Paris 1931). Husserl here reviews the phenomenological epoché (or phenomenological reduction), presented earlier in his pivotal ''Ideen'' (1913), in terms of a further reduction of experience to what he calls a 'sphere of ownness.' From within this sphere, which Husserl enacts to show the impossibility of solipsism, the transcendental ego finds itself always already paired with the lived body of another ego, another monad. This 'a priori

('from the earlier') and ('from the later') are Latin phrases used in philosophy to distinguish types of knowledge, Justification (epistemology), justification, or argument by their reliance on experience. knowledge is independent from any ...

' interconnection of bodies, given in perception, is what founds the interconnection of consciousnesses known as transcendental intersubjectivity

Intersubjectivity describes the shared understanding that emerges from interpersonal interactions.

The term first appeared in social science in the 1970s and later incorporated into psychoanalytic theory by George E. Atwood and Robert Stolorow, ...

, which Husserl would go on to describe at length in volumes of unpublished writings. There has been a debate over whether or not Husserl's description of ownness and its movement into intersubjectivity is sufficient to reject the charge of solipsism, to which Descartes, for example, was subject. One argument against Husserl's description works this way: instead of infinity and the Deity being the ego's gateway to the Other, as in Descartes, Husserl's ego in the ''Cartesian Meditations'' itself becomes transcendent. It remains, however, alone (unconnected). Only the ego's grasp "by analogy" of the Other (e.g., by conjectural reciprocity) allows the possibility for an 'objective' intersubjectivity, and hence for community.

In 1933, the racial laws of the new National Socialist German Workers Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor, the German Worker ...

were enacted. On 6 April Husserl was banned from using the library at the University of Freiburg, or any other academic library; the following week, after a public outcry, he was reinstated. Yet his colleague Heidegger was elected Rector of the university on 21–22 April, and joined the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

. By contrast, in July Husserl resigned from the Deutsche Akademie

The Academy for the Scholarly Research and Fostering of Germandom (''die Akademie zur Wissenschaftlichen Erforschung und Pflege des Deutschtums''), or German Academy (''die Deutsche Akademie'', ), was a German cultural institute founded in 1925 at ...

.

Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

, Descartes, several British philosophers, and Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, et ...

. The apolitical Husserl before had specifically avoided such historical discussions, pointedly preferring to go directly to an investigation of consciousness. Merleau-Ponty

Maurice Jean Jacques Merleau-Ponty. ( ; ; 14 March 1908 – 3 May 1961) was a French phenomenological philosopher, strongly influenced by Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. The constitution of meaning in human experience was his main interest ...

and others question whether Husserl here does not undercut his own position, in that Husserl had attacked in principle historicism

Historicism is an approach to explaining the existence of phenomena, especially social and cultural practices (including ideas and beliefs), by studying the process or history by which they came about. The term is widely used in philosophy, ant ...

, while specifically designing his phenomenology to be rigorous enough to transcend the limits of history. On the contrary, Husserl may be indicating here that historical traditions are merely features given to the pure ego's intuition, like any other. A longer section follows on the "lifeworld

Lifeworld (or life-world; ) may be conceived as a universe of what is self-evident or given, a world that subjects may experience together. The concept was popularized by Edmund Husserl, who emphasized its role as the ground of all knowledge in l ...

" 'Lebenswelt'' one not observed by the objective logic of science, but a world seen through subjective experience. Yet a problem arises similar to that dealing with 'history' above, a chicken-and-egg problem. Does the lifeworld contextualize and thus compromise the gaze of the pure ego, or does the phenomenological method nonetheless raise the ego up transcendent? These last writings presented the fruits of his professional life. Since his university retirement, Husserl had "worked at a tremendous pace, producing several major works."

After suffering a fall in the autumn of 1937, the philosopher became ill with pleurisy

Pleurisy, also known as pleuritis, is inflammation of the membranes that surround the lungs and line the chest cavity (Pulmonary pleurae, pleurae). This can result in a sharp chest pain while breathing. Occasionally the pain may be a constant d ...

. Edmund Husserl died in Freiburg on 27 April 1938, having just turned 79. His wife, Malvine, survived him. Eugen Fink, his research assistant, delivered his eulogy. Gerhard Ritter was the only Freiburg faculty member to attend the funeral, as an anti-Nazi protest.

Heidegger and the Nazi era

Husserl was rumoured to have been denied the use of the library at Freiburg as a result of the anti-Jewish legislation of April 1933. Relatedly, among other disabilities, Husserl was unable to publish his works in Nazi Germany ee above footnote to ''Die Krisis'' (1936) It was also rumoured that his former pupilMartin Heidegger

Martin Heidegger (; 26 September 1889 – 26 May 1976) was a German philosopher known for contributions to Phenomenology (philosophy), phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism. His work covers a range of topics including metaphysics, art ...

informed Husserl that he was discharged, but it was actually the previous rector.

Apparently, Husserl and Heidegger had moved apart during the 1920s, which became clearer after 1928 when Husserl retired and Heidegger succeeded to his university chair. In the summer of 1929 Husserl had studied carefully selected writings of Heidegger, coming to the conclusion that on several of their key positions they differed: e.g., Heidegger substituted ''Dasein'' Being-there"for the pure ego, thus transforming phenomenology into an anthropology, a type of psychologism strongly disfavored by Husserl. Such observations of Heidegger, along with a critique of Max Scheler

Max Ferdinand Scheler (; 22 August 1874 – 19 May 1928) was a German philosopher known for his work in phenomenology, ethics, and philosophical anthropology. Considered in his lifetime one of the most prominent German philosophers,Davis, Zacha ...

, were put into a lecture Husserl gave to various ''Kant Societies'' in Frankfurt, Berlin, and Halle during 1931 entitled ''Phänomenologie und Anthropologie''.Husserl, Edmund (1997). ''Psychological and Transcendental Phenomenology and the Confrontation with Heidegger (1927–1931)'', translated by T. Sheehan and R. Palmer. Dordrecht: Kluwer. , which contains his "Phänomenologie und Anthropologie" at pp. 485–500.

In the wartime 1941 edition of Heidegger's primary work, ''Being and Time

''Being and Time'' () is the 1927 ''magnum opus'' of German philosopher Martin Heidegger and a key document of existentialism. ''Being and Time'' had a notable impact on subsequent philosophy, literary theory and many other fields. Though controv ...

'' (', first published in 1927), the original dedication to Husserl was removed. This was not due to a negation of the relationship between the two philosophers, however, but rather was the result of a suggested censorship by Heidegger's publisher who feared that the book might otherwise be banned by the Nazi regime."Nur noch ein Gott kann uns retten". ''Der Spiegel'', 31 May 1967. The dedication can still be found in a footnote on page 38, thanking Husserl for his guidance and generosity. Husserl had died three years earlier. In post-war editions of ''Sein und Zeit'' the dedication to Husserl is restored. The complex, troubled, and sundered philosophical relationship between Husserl and Heidegger has been widely discussed.

On 4 May 1933, Professor Edmund Husserl addressed the recent regime change in Germany and its consequences:The future alone will judge which was the true Germany in 1933, and who were the true Germans—those who subscribe to the more or less materialistic-mythical racial prejudices of the day, or those Germans pure in heart and mind, heirs to the great Germans of the past whose tradition they revere and perpetuate.After his death, Husserl's manuscripts, amounting to approximately 40,000 pages of "'' Gabelsberger''" stenography and his complete research library, were in 1939 smuggled to the

Catholic University of Leuven

University of Leuven or University of Louvain (; ) may refer to:

* Old University of Leuven (1425–1797)

* State University of Leuven (1817–1835)

* Catholic University of Leuven (1834–1968)

* Katholieke Universiteit Leuven or KU Leuven (1968 ...

in Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

by the Franciscan priest Herman Van Breda. There they were deposited at Leuven to form the ''Husserl-Archives'' of the Higher Institute of Philosophy

The Institut supérieur de Philosophie (ISP) (French for: Higher Institute of Philosophy) is an independent research institute at the University of Louvain (UCLouvain) in Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium. It is a separate entity to the UCLouvain School ...

. Much of the material in his research manuscripts has since been published in the Husserliana critical edition series.

Development of his thought

Several early themes

In his first works, Husserl combined mathematics, psychology, and philosophy with the goal of providing a sound foundation for mathematics. He analyzed the psychological process needed to obtain the concept of number and then built up a theory on this analysis. He used methods and concepts taken from his teachers. From Weierstrass, he derived the idea of generating the concept of number by counting a certain collection of objects. From Brentano and Stumpf, he took the distinction between ''proper'' and ''improper'' presenting. In an example, Husserl explained this in the following way: if someone is standing in front of a house, they have a proper, direct presentation of that house, but if they are looking for it and ask for directions, then these directions (e.g. the house on the corner of this and that street) are an indirect, improper presentation. In other words, the person can have a proper presentation of an object if it is actually present, and an improper (or symbolic, as Husserl also calls it) one if they only can indicate that object through signs, symbols, etc. Husserl's '' Logical Investigations'' (1900–1901) is considered the starting point for the formal theory of wholes and their parts known asmereology

Mereology (; from Greek μέρος 'part' (root: μερε-, ''mere-'') and the suffix ''-logy'', 'study, discussion, science') is the philosophical study of part-whole relationships, also called ''parthood relationships''. As a branch of metaphys ...

.

Another important element that Husserl took over from Brentano was intentionality

Intentionality is the mental ability to refer to or represent something. Sometimes regarded as the ''mark of the mental'', it is found in mental states like perceptions, beliefs or desires. For example, the perception of a tree has intentionality ...

, the notion that the main characteristic of consciousness

Consciousness, at its simplest, is awareness of a state or object, either internal to oneself or in one's external environment. However, its nature has led to millennia of analyses, explanations, and debate among philosophers, scientists, an ...

is that it is always intentional. While often simplistically summarised as "aboutness" or the relationship between mental acts and the external world, Brentano defined it as the main characteristic of ''mental phenomena'', by which they could be distinguished from ''physical phenomena''. Every mental phenomenon, every psychological act, has a content, is directed at an object (the '' intentional object''). Every belief, desire, etc. has an object that it is about: the believed, the wanted. Brentano used the expression "intentional inexistence" to indicate the status of the objects of thought in the mind. The property of being intentional, of having an intentional object, was the key feature to distinguish mental phenomena and physical phenomena, because physical phenomena lack intentionality altogether.

The elaboration of phenomenology

Some years after the 1900–1901 publication of his main work, the ''Logische Untersuchungen'' (''Logical Investigations''), Husserl made some key conceptual elaborations which led him to assert that to study the structure of consciousness, one would have to distinguish between the act of consciousness and the phenomena at which it is directed (the objects as intended). Knowledge ofessence

Essence () has various meanings and uses for different thinkers and in different contexts. It is used in philosophy and theology as a designation for the property (philosophy), property or set of properties or attributes that make an entity the ...

s would only be possible by " bracketing" all assumptions about the existence of an external world. This procedure he called "epoché

In Hellenistic philosophy, epoché (also

epoche;

pronounced or

;

)

is suspension of judgment but also "withholding of assent".

Pyrrhonism

Epoché plays an important role in Pyrrhonism, the skeptical philosophy named after Pyrrho, who is ...

". These new concepts prompted the publication of the ''Ideen'' (''Ideas'') in 1913, in which they were at first incorporated, and a plan for a second edition of the ''Logische Untersuchungen''.

From the ''Ideen'' onward, Husserl concentrated on the ideal, essential structures of consciousness. The metaphysical problem of establishing the reality of what people perceive, as distinct from the perceiving subject, was of little interest to Husserl in spite of his being a transcendental idealist. Husserl proposed that the world of objects—and of ways in which people direct themselves toward and perceive those objects—is normally conceived of in what he called the "natural attitude", which is characterized by a belief that objects exist distinct from the perceiving subject and exhibit properties that people see as emanating from them (this attitude is also called physicalist objectivism). Husserl proposed a radical new phenomenological way of looking at objects by examining how people, in their many ways of being intentionally directed toward them, actually "constitute" them (to be distinguished from materially creating objects or objects merely being figments of the imagination); in the Phenomenological standpoint, the object ceases to be something simply "external" and ceases to be seen as providing indicators about what it is, and becomes a grouping of perceptual and functional aspects that imply one another under the idea of a particular object or "type". The notion of objects as real is not expelled by phenomenology, but "bracketed" as a way in which people regard objectsinstead of a feature that inheres in an object's essence, founded in the relation between the object and the perceiver. To better understand the world of appearances and objects, phenomenology attempts to identify the invariant features of how objects are perceived and pushes attributions of reality into their role as an attribution about the things people perceive (or an assumption underlying how people perceive objects). The major dividing line in Husserl's thought is the turn to transcendental idealism.

In a later period, Husserl began to wrestle with the complicated issues of intersubjectivity

Intersubjectivity describes the shared understanding that emerges from interpersonal interactions.

The term first appeared in social science in the 1970s and later incorporated into psychoanalytic theory by George E. Atwood and Robert Stolorow, ...

, specifically, how communication about an object can be assumed to refer to the same ideal entity ('' Cartesian Meditations'', Meditation V). Husserl tries new methods of bringing his readers to understand the importance of phenomenology

Phenomenology may refer to:

Art

* Phenomenology (architecture), based on the experience of building materials and their sensory properties

Philosophy

* Phenomenology (Peirce), a branch of philosophy according to Charles Sanders Peirce (1839� ...

to scientific inquiry (and specifically to psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

) and what it means to "bracket" the natural attitude. '' The Crisis of the European Sciences'' is Husserl's unfinished work that deals most directly with these issues. In it, Husserl for the first time attempts a historical overview of the development of Western philosophy and science, emphasizing the challenges presented by their increasingly one-sided empirical

Empirical evidence is evidence obtained through sense experience or experimental procedure. It is of central importance to the sciences and plays a role in various other fields, like epistemology and law.

There is no general agreement on how t ...

and naturalistic orientation. Husserl declares that mental and spiritual reality possess their own reality independent of any physical basis, and that a science of the mind ('Geisteswissenschaft

''Geisteswissenschaft'' (; plural: ''Geisteswissenschaften'' ; "science of mind"; "spirit science") is a set of human sciences such as philosophy, history, philology, musicology, linguistics, theater studies, literary studies, media studies, ...

') must be established on as scientific a foundation as the natural science

Natural science or empirical science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer ...

s have managed: "It is my conviction that intentional phenomenology has for the first time made spirit as spirit the field of systematic scientific experience, thus effecting a total transformation of the task of knowledge."

Husserl's thought

Husserl's thought is revolutionary in several ways, most notably in the distinction between "natural" and "phenomenological" modes of understanding. In the former, sense-perception in correspondence with the material realm constitutes the known reality, and understanding is premised on the accuracy of the perception and the objective knowability of what is called the "real world". Phenomenological understanding strives to be rigorously "presuppositionless" by means of what Husserl calls " phenomenological reduction". This reduction is not conditioned but rather transcendental: in Husserl's terms, pure consciousness of absolute Being. In Husserl's work, consciousness of any given thing calls for discerning its meaning as an "intentional object". Such an object does not simply strike the senses, to be interpreted or misinterpreted by mental reason; it has already been selected and grasped, grasping being an etymological connotation, of ''percipere'', the root of "perceive".Meaning and object

From ''Logical Investigations'' (1900/1901) to ''Experience and Judgment'' (published in 1939), Husserl expressed clearly the difference between meaning andobject

Object may refer to:

General meanings

* Object (philosophy), a thing, being, or concept

** Object (abstract), an object which does not exist at any particular time or place

** Physical object, an identifiable collection of matter

* Goal, an a ...

. He identified several different kinds of names. For example, there are names that have the role of properties that uniquely identify an object. Each of these names expresses a meaning and designates the same object. Examples of this are "the victor in Jena" and "the loser in Waterloo", or "the equilateral triangle" and "the equiangular triangle"; in both cases, both names express different meanings, but designate the same object. There are names which have no meaning, but have the role of designating an object: "Aristotle", "Socrates", and so on. Finally, there are names which designate a variety of objects. These are called "universal names"; their meaning is a "concept

A concept is an abstract idea that serves as a foundation for more concrete principles, thoughts, and beliefs.

Concepts play an important role in all aspects of cognition. As such, concepts are studied within such disciplines as linguistics, ...

" and refers to a series of objects (the extension of the concept). The way people know sensible objects is called " sensible intuition".

Husserl also identifies a series of "formal words" which are necessary to form sentences

The ''Sentences'' (. ) is a compendium of Christian theology written by Peter Lombard around 1150. It was the most important religious textbook of the Middle Ages.

Background

The sentence genre emerged from works like Prosper of Aquitaine's ...

and have no sensible correlates. Examples of formal words are "a", "the", "more than", "over", "under", "two", "group", and so on. Every sentence must contain formal words to designate what Husserl calls "formal categories". There are two kinds of categories: meaning categories and formal-ontological

Ontology is the philosophical study of being. It is traditionally understood as the subdiscipline of metaphysics focused on the most general features of reality. As one of the most fundamental concepts, being encompasses all of reality and every ...

categories. Meaning categories relate judgments; they include forms of conjunction, disjunction

In logic, disjunction (also known as logical disjunction, logical or, logical addition, or inclusive disjunction) is a logical connective typically notated as \lor and read aloud as "or". For instance, the English language sentence "it is ...

, forms of plural, among others. Formal-ontological categories relate objects and include notions such as set, cardinal number

In mathematics, a cardinal number, or cardinal for short, is what is commonly called the number of elements of a set. In the case of a finite set, its cardinal number, or cardinality is therefore a natural number. For dealing with the cas ...

, ordinal number

In set theory, an ordinal number, or ordinal, is a generalization of ordinal numerals (first, second, th, etc.) aimed to extend enumeration to infinite sets.

A finite set can be enumerated by successively labeling each element with the leas ...

, part and whole, relation, and so on. The way people know these categories is through a faculty of understanding called "categorial intuition".

Through sensible intuition, consciousness

Consciousness, at its simplest, is awareness of a state or object, either internal to oneself or in one's external environment. However, its nature has led to millennia of analyses, explanations, and debate among philosophers, scientists, an ...

constitutes what Husserl calls a "situation of affairs" (). It is a passive constitution where objects themselves are presented. To this situation of affairs, through categorial intuition, people are able to constitute a " state of affairs" (). One situation of affairs, through objective acts of consciousness (acts of constituting categorially) can serve as the basis for constituting multiple states of affairs. For example, suppose ''a'' and ''b'' are two sensible objects in a certain situation of affairs. It can be used as the basis to say, "''a''<''b''" and "''b''>''a''", two judgments which designate the same state of affairs. For Husserl, a sentence has a proposition

A proposition is a statement that can be either true or false. It is a central concept in the philosophy of language, semantics, logic, and related fields. Propositions are the object s denoted by declarative sentences; for example, "The sky ...

or judgment

Judgement (or judgment) is the evaluation of given circumstances to make a decision. Judgement is also the ability to make considered decisions.

In an informal context, a judgement is opinion expressed as fact. In the context of a legal trial ...

as its meaning, and refers to a state of affairs which has a situation of affairs as a reference base.

Formal and regional ontology

Husserl seesontology

Ontology is the philosophical study of existence, being. It is traditionally understood as the subdiscipline of metaphysics focused on the most general features of reality. As one of the most fundamental concepts, being encompasses all of realit ...

as a ''science of essences''. ''Sciences of essences'' are contrasted with ''factual sciences'': the former are knowable a priori

('from the earlier') and ('from the later') are Latin phrases used in philosophy to distinguish types of knowledge, Justification (epistemology), justification, or argument by their reliance on experience. knowledge is independent from any ...

and provide the foundation for the later, which are knowable a posteriori

('from the earlier') and ('from the later') are Latin phrases used in philosophy to distinguish types of knowledge, justification, or argument by their reliance on experience. knowledge is independent from any experience. Examples include ...

. Ontology as a science of essences is not interested in ''actual facts'', but in the essences themselves, whether they ''have instances or not''. Husserl distinguishes between ''formal ontology

In philosophy, the term formal ontology is used to refer to an ontology defined by axioms in a formal language with the goal to provide an unbiased (Problem domain, domain- and application-independent) view on Reality#Western philosophy, realit ...

'', which investigates the essence of ''objectivity in general'', and ''regional ontologies'', which study ''regional essences'' that are shared by all entities belonging to the region. Regions correspond to the highest genera

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family as used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In binomial nomenclature, the genus name forms the first part of the binomial s ...

of concrete entities: material nature, personal consciousness, and interpersonal spirit. Husserl's method for studying ontology and sciences of essence in general is called eidetic variation

Bend Studio (formerly Blank, Berlyn & Co., Inc. and Eidetic, Inc.) is an American video game developer based in Bend, Oregon. Founded in 1992, the studio is best known for developing ''Bubsy 3D'', the ''Syphon Filter'' series, and ''Days Gone'' ...

. It involves imagining an object of the kind under investigation and varying its features. The changed feature is ''inessential'' to this kind if the object can survive its change, otherwise it belongs to the ''kind's essence''. For example, a triangle remains a triangle if one of its sides is extended, but it ceases to be a triangle if a fourth side is added. Regional ontology involves applying this method to the essences corresponding to the highest genera.

Philosophy of logic and mathematics

Husserl believed that ''truth-in-itself'' has asontological

Ontology is the philosophical study of being. It is traditionally understood as the subdiscipline of metaphysics focused on the most general features of reality. As one of the most fundamental concepts, being encompasses all of reality and every ...

correlate ''being-in-itself'', just as meaning categories have formal-ontological categories as correlates. Logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

is a formal theory of judgment

Judgement (or judgment) is the evaluation of given circumstances to make a decision. Judgement is also the ability to make considered decisions.

In an informal context, a judgement is opinion expressed as fact. In the context of a legal trial ...

, that studies the formal ''a priori'' relations among judgments using meaning categories. Mathematics, on the other hand, is formal ontology

In philosophy, the term formal ontology is used to refer to an ontology defined by axioms in a formal language with the goal to provide an unbiased (Problem domain, domain- and application-independent) view on Reality#Western philosophy, realit ...

; it studies all the possible forms of being (of objects). Hence, for both logic and mathematics, the different formal categories are the objects of study, not the sensible objects themselves. The problem with the psychological approach to mathematics and logic is that it fails to account for the fact that this approach is about formal categories, and not simply about abstractions from sensibility alone. The reason why sensible objects are not dealt with in mathematics is because of another faculty of understanding called "categorial abstraction." Through this faculty, people are able to get rid of sensible components of judgments, and just focus on formal categories themselves.

Thanks to " eidetic reduction" (or "essential intuition"), people are able to grasp the possibility, impossibility, necessity, and contingency among concepts and among formal categories. Categorial intuition, along with categorial abstraction and eidetic reduction, are the basis for logical and mathematical knowledge.

Husserl criticized the logicians of his day for not focusing on the relation between subjective processes that offer objective knowledge of pure logic. All subjective activities of consciousness need an ideal correlate, and objective logic (constituted noematically), as it is constituted by consciousness, needs a noetic correlate (the subjective activities of consciousness).

Husserl stated that logic has three strata, each further away from consciousness and psychology than those that precede it.

* The first stratum is what Husserl called a "morphology of meanings" concerning ''a priori'' ways to relate judgments to make them meaningful. In this stratum, people elaborate a "pure grammar" or a logical syntax, and he would call its rules "laws to prevent non-sense", which would be similar to what logic calls today "formation rules

In mathematical logic, formation rules are rules for describing well-formed words over the alphabet of a formal language. These rules only address the location and manipulation of the strings of the language. It does not describe anything else a ...

". Mathematics, as logic's ontological correlate, also has a similar stratum, a "morphology of formal-ontological categories".

* The second stratum would be called by Husserl "logic of consequence" or the "logic of non-contradiction" which explores all possible forms of true judgments. He includes here syllogistic classic logic, propositional logic, and that of predicates. This is a semantic stratum, and the rules of this stratum would be the "laws to avoid counter-sense" or "laws to prevent contradiction". They are very similar to today's logic " transformation rules". Mathematics also has a similar stratum which is based, among others, on the pure theory of pluralities and a pure theory of numbers. They provide a science of the conditions of possibility of any theory whatsoever. Husserl also talked about what he called "logic of truth," which consists of the formal laws of possible truth and its modalities, and precedes the third logical stratum.

* The third stratum is metalogic

Metalogic is the metatheory of logic. Whereas ''logic'' studies how logical systems can be used to construct valid and sound arguments, metalogic studies the properties of logical systems. Logic concerns the truths that may be derived using a lo ...

al, what he called a "theory of all possible forms of theories." It explores all possible theories in an ''a priori'' fashion, rather than the possibility of theory in general. Theories of possible relations between pure forms of theories could be established; these logical relations could, in turn, be investigated using deduction. The logician is free to see the extension of this deductive, theoretical sphere of pure logic.

The ontological correlate to the third stratum is the " theory of manifolds". In formal ontology, it is a free investigation where a mathematician can assign several meanings to several symbols, and all their possible valid deductions in a general and indeterminate manner. It is, properly speaking, the most universal mathematics of all. Through the positing of certain indeterminate objects (formal-ontological categories) as well as any combination of mathematical axioms, mathematicians can explore the apodeictic connections between them, as long as consistency is preserved.

According to Husserl, this view of logic and mathematics accounted for the objectivity of a series of mathematical developments of his time, such as ''n''-dimensional manifold

In mathematics, a manifold is a topological space that locally resembles Euclidean space near each point. More precisely, an n-dimensional manifold, or ''n-manifold'' for short, is a topological space with the property that each point has a N ...

s (both Euclidean and non-Euclidean), Hermann Grassmann

Hermann Günther Grassmann (, ; 15 April 1809 – 26 September 1877) was a German polymath known in his day as a linguist and now also as a mathematician. He was also a physicist, general scholar, and publisher. His mathematical work was littl ...

's theory of extensions, William Rowan Hamilton

Sir William Rowan Hamilton (4 August 1805 – 2 September 1865) was an Irish astronomer, mathematician, and physicist who made numerous major contributions to abstract algebra, classical mechanics, and optics. His theoretical works and mathema ...

's Hamiltonians, Sophus Lie

Marius Sophus Lie ( ; ; 17 December 1842 – 18 February 1899) was a Norwegian mathematician. He largely created the theory of continuous symmetry and applied it to the study of geometry and differential equations. He also made substantial cont ...

's theory of transformation groups, and Cantor's set theory

Set theory is the branch of mathematical logic that studies Set (mathematics), sets, which can be informally described as collections of objects. Although objects of any kind can be collected into a set, set theory – as a branch of mathema ...

.

Jacob Klein was one student of Husserl who pursued this line of inquiry, seeking to "desedimentize" mathematics and the mathematical sciences.

Husserl and psychologism

Philosophy of arithmetic and Frege

After obtaining his PhD in mathematics, Husserl began analyzing thefoundations of mathematics

Foundations of mathematics are the mathematical logic, logical and mathematics, mathematical framework that allows the development of mathematics without generating consistency, self-contradictory theories, and to have reliable concepts of theo ...

from a psychological point of view. In his ''On the Concept of Number'' (1887) and in his '' Philosophy of Arithmetic'' (1891), Husserl sought, by employing Brentano's descriptive psychology, to define the natural number

In mathematics, the natural numbers are the numbers 0, 1, 2, 3, and so on, possibly excluding 0. Some start counting with 0, defining the natural numbers as the non-negative integers , while others start with 1, defining them as the positive in ...

s in a way that advanced the methods and techniques of Karl Weierstrass

Karl Theodor Wilhelm Weierstrass (; ; 31 October 1815 – 19 February 1897) was a German mathematician often cited as the " father of modern analysis". Despite leaving university without a degree, he studied mathematics and trained as a school t ...

, Richard Dedekind

Julius Wilhelm Richard Dedekind (; ; 6 October 1831 – 12 February 1916) was a German mathematician who made important contributions to number theory, abstract algebra (particularly ring theory), and the axiomatic foundations of arithmetic. H ...

, Georg Cantor

Georg Ferdinand Ludwig Philipp Cantor ( ; ; – 6 January 1918) was a mathematician who played a pivotal role in the creation of set theory, which has become a foundations of mathematics, fundamental theory in mathematics. Cantor establi ...

, Gottlob Frege

Friedrich Ludwig Gottlob Frege (; ; 8 November 1848 – 26 July 1925) was a German philosopher, logician, and mathematician. He was a mathematics professor at the University of Jena, and is understood by many to be the father of analytic philos ...

, and other contemporary mathematicians. Later, in the first volume of his ''Logical Investigations'', the ''Prolegomena of Pure Logic'', Husserl, while attacking the psychologistic point of view in logic and mathematics, also appears to reject much of his early work, although the forms of psychologism analysed and refuted in the ''Prolegomena'' did not apply directly to his '' Philosophy of Arithmetic''. Some scholars question whether Frege's negative review of the ''Philosophy of Arithmetic'' helped turn Husserl towards modern Platonism, but he had already discovered the work of Bernard Bolzano

Bernard Bolzano (, ; ; ; born Bernardus Placidus Johann Nepomuk Bolzano; 5 October 1781 – 18 December 1848) was a Bohemian mathematician, logician, philosopher, theologian and Catholic priest of Italian extraction, also known for his liberal ...

independently around 1890/91. In his ''Logical Investigations'', Husserl explicitly mentioned Bolzano, G. W. Leibniz and Hermann Lotze as inspirations for his newer position.

Husserl's review of Ernst Schröder, published before Frege's landmark 1892 article, clearly distinguishes sense

A sense is a biological system used by an organism for sensation, the process of gathering information about the surroundings through the detection of Stimulus (physiology), stimuli. Although, in some cultures, five human senses were traditio ...

from reference

A reference is a relationship between objects in which one object designates, or acts as a means by which to connect to or link to, another object. The first object in this relation is said to ''refer to'' the second object. It is called a ''nam ...

; thus, Husserl's notions of noema and object also arose independently. Likewise, in his criticism of Frege in the ''Philosophy of Arithmetic'', Husserl remarks on the distinction between the content and the extension of a concept. Moreover, the distinction between the subjective mental act, namely the content of a concept, and the (external) object, was developed independently by Brentano and his school, and may have surfaced as early as Brentano's 1870s lectures on logic.

Scholars such as J. N. Mohanty, Claire Ortiz Hill, and Guillermo E. Rosado Haddock, among others, have argued that Husserl's so-called change from psychologism

Psychologism is a family of philosophical positions, according to which certain psychological facts, laws, or entities play a central role in grounding or explaining certain non-psychological facts, laws, or entities. The word was coined by Joh ...

to Platonism

Platonism is the philosophy of Plato and philosophical systems closely derived from it, though contemporary Platonists do not necessarily accept all doctrines of Plato. Platonism has had a profound effect on Western thought. At the most fundam ...

came about independently of Frege's review. For example, the review falsely accuses Husserl of subjectivizing everything, so that no objectivity is possible, and falsely attributes to him a notion of abstraction

Abstraction is a process where general rules and concepts are derived from the use and classifying of specific examples, literal (reality, real or Abstract and concrete, concrete) signifiers, first principles, or other methods.

"An abstraction" ...

whereby objects disappear until all that remains are numbers as mere ghosts. Contrary to what Frege states, in Husserl's ''Philosophy of Arithmetic'', there are already two different kinds of representations: subjective and objective. Moreover, objectivity is clearly defined in that work. Frege's attack seems to be directed at certain foundational doctrines then current in Weierstrass's Berlin School, of which Husserl and Cantor cannot be said to be orthodox representatives.

Furthermore, various sources indicate that Husserl changed his mind about psychologism as early as 1890, a year before he published the ''Philosophy of Arithmetic''. Husserl stated that by the time he published that book, he had already changed his mind—that he had doubts about psychologism from the very outset. He attributed this change of mind to his reading of Leibniz, Bolzano, Lotze, and David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism. Beg ...

. Husserl makes no mention of Frege as a decisive factor in this change. In his ''Logical Investigations'', Husserl mentions Frege only twice, once in a footnote to point out that he had retracted three pages of his criticism of Frege's ''The Foundations of Arithmetic'', and again to question Frege's use of the word ' to designate "reference" rather than "meaning" (sense).

In a letter dated 24 May 1891, Frege thanked Husserl for sending him a copy of the ''Philosophy of Arithmetic'' and Husserl's review of Ernst Schröder's '. In the same letter, Frege used the review of Schröder's book to analyze Husserl's notion of the sense of reference of concept words. Hence Frege recognized, as early as 1891, that Husserl distinguished between sense and reference. Consequently, Frege and Husserl independently elaborated a theory of sense and reference before 1891.

Commentators argue that Husserl's notion of noema has nothing to do with Frege's notion of sense, because ''noemata'' are necessarily fused with noeses, which are the conscious activities of consciousness. ''Noemata'' have three different levels:

* The substratum, which is never presented to consciousness, and is the support of all the properties of the object;

* The ''noematic'' senses, which are the different ways the objects are presented to us;

* The modalities of being (possible, doubtful, existent, non-existent, absurd, and so on).

Consequently, in intentional activities, even non-existent objects can be constituted, and form part of the whole noema. Frege, however, did not conceive of objects as forming parts of senses: If a proper name denotes a non-existent object, it does not have a reference, hence, concepts with no objects have no truth value

In logic and mathematics, a truth value, sometimes called a logical value, is a value indicating the relation of a proposition to truth, which in classical logic has only two possible values ('' true'' or '' false''). Truth values are used in ...

in arguments. Moreover, Husserl did not maintain that predicates of sentences designate concepts. According to Frege, the reference of a sentence is a truth value; for Husserl, it is a "state of affairs." Frege's notion of "sense" is unrelated to Husserl's noema, while the latter's notions of "meaning" and "object" differ from those of Frege.

In detail, Husserl's conception of logic and mathematics differs from that of Frege, who held that arithmetic could be derived from logic. For Husserl, this is not the case: mathematics (with the exception of geometry

Geometry (; ) is a branch of mathematics concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. Geometry is, along with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. A mathematician w ...

) is the ontological correlate of logic, and while both fields are related, neither one is strictly reducible to the other.

Husserl's criticism of psychologism

Reacting against authors such asJohn Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, politician and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of liberalism and social liberalism, he contributed widely to s ...

, Christoph von Sigwart and his own former teacher Brentano, Husserl criticised their psychologism in mathematics and logic, i.e. their conception of these abstract and ''a priori'' sciences as having an essentially empirical foundation and a prescriptive or descriptive nature. According to psychologism

Psychologism is a family of philosophical positions, according to which certain psychological facts, laws, or entities play a central role in grounding or explaining certain non-psychological facts, laws, or entities. The word was coined by Joh ...

, logic would not be an autonomous discipline, but a branch of psychology, either proposing a prescriptive and practical "art" of correct judgement (as Brentano and some of his more orthodox students did) or a description of the factual processes of human thought. Husserl pointed out that the failure of anti-psychologists to defeat psychologism was a result of being unable to distinguish between the foundational, theoretical side of logic, and the applied, practical side. Pure logic does not deal at all with "thoughts" or "judgings" as mental episodes but with ''a priori'' laws and conditions for any theory and any judgments whatsoever, conceived as propositions in themselves.

:"Here 'Judgement' has the same meaning as 'proposition', understood, not as a grammatical, but as an ideal unity of meaning. This is the case with all the distinctions of acts or forms of judgement, which provide the foundations for the laws of pure logic. Categorial, hypothetical, disjunctive, existential judgements, and however else we may call them, in pure logic are not names for classes of judgements, but for ideal forms of propositions."