Hundred Days on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Hundred Days ( ), also known as the War of the Seventh Coalition (), marked the period between

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

's return from eleven months of exile on the island of Elba

Elba (, ; ) is a Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean island in Tuscany, Italy, from the coastal town of Piombino on the Italian mainland, and the largest island of the Tuscan Archipelago. It is also part of the Arcipelago Toscano National Park, a ...

to Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

on20 March 1815 and the second restoration of King Louis XVIII

Louis XVIII (Louis Stanislas Xavier; 17 November 1755 – 16 September 1824), known as the Desired (), was King of France from 1814 to 1824, except for a brief interruption during the Hundred Days in 1815. Before his reign, he spent 23 y ...

on 8 July 1815 (a period of 110 days). This period saw the War of the Seventh Coalition, and includes the Waterloo campaign

The Waterloo campaign, also known as the Belgian campaign (15 June – 8 July 1815) was fought between the French Army of the North (France), Army of the North and two War of the Seventh Coalition, Seventh Coalition armies, an Anglo-allied arm ...

and the Neapolitan War

The Neapolitan War, also known as the Austro-Neapolitan War, was a conflict between the Napoleonic Kingdom of Naples (Napoleonic), Kingdom of Naples and the Austrian Empire. It started on 15 March 1815, when King Joachim Murat declared war on ...

as well as several other minor campaigns. The phrase ''les Cent Jours'' (the Hundred Days) was first used by the prefect

Prefect (from the Latin ''praefectus'', substantive adjectival form of ''praeficere'': "put in front", meaning in charge) is a magisterial title of varying definition, but essentially refers to the leader of an administrative area.

A prefect' ...

of Paris, Gaspard, comte de Chabrol, in his speech welcoming the king back to Paris on 8 July.

Napoleon returned while the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon, Napol ...

was sitting. On 13 March, seven days before Napoleon reached Paris, the powers at the Congress of Vienna declared him an outlaw, and on 25 March, Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

, Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

, Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, the four Great Powers and key members of the Seventh Coalition, bound themselves to put 150,000 men each into the field to end his rule. This set the stage for the last conflict in the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

, the defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo, Belgium, Waterloo (then in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium), marking the end of the Napoleonic Wars. The French Imperial Army (1804–1815), Frenc ...

, the second restoration of the French kingdom, and the permanent exile of Napoleon to the distant island of Saint Helena

Saint Helena (, ) is one of the three constituent parts of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha, a remote British overseas territory.

Saint Helena is a volcanic and tropical island, located in the South Atlantic Ocean, some 1,874 km ...

, where he died in 1821.

Background

Napoleon's rise and fall

The French Revolutionary andNapoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

pitted France against various coalitions of other European nations nearly continuously from 1792 onward. The overthrow and subsequent public execution of Louis XVI

Louis XVI (Louis-Auguste; ; 23 August 1754 – 21 January 1793) was the last king of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. The son of Louis, Dauphin of France (1729–1765), Louis, Dauphin of France (son and heir- ...

in France had greatly disturbed other European leaders, who vowed to crush the French Republic

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

. Rather than leading to France's defeat, the wars allowed the revolutionary regime to expand beyond its borders and create client republics. The success of the French forces made a hero out of their best commander, Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

. In 1799, Napoleon staged a successful coup d'état and became First Consul of the new French Consulate

The Consulate () was the top-level government of the First French Republic from the fall of the French Directory, Directory in the coup of 18 Brumaire on 9 November 1799 until the start of the First French Empire, French Empire on 18 May 1804.

...

. Five years later, he crowned himself Emperor Napoleon I.

The rise of Napoleon troubled the other European powers as much as the earlier revolutionary regime had. Despite the formation of new coalitions against him, Napoleon's forces continued to conquer much of Europe. The tide of war began to turn after a disastrous French invasion of Russia

The French invasion of Russia, also known as the Russian campaign (), the Second Polish War, and in Russia as the Patriotic War of 1812 (), was initiated by Napoleon with the aim of compelling the Russian Empire to comply with the Continenta ...

in 1812 that resulted in the loss of much of Napoleon's army. The following year, during the War of the Sixth Coalition

In the War of the Sixth Coalition () (December 1812 – May 1814), sometimes known in Germany as the Wars of Liberation (), a coalition of Austrian Empire, Austria, Kingdom of Prussia, Prussia, Russian Empire, Russia, History of Spain (1808– ...

, Coalition forces defeated the French in the Battle of Leipzig.

Following its victory at Leipzig, the Coalition vowed to press on to Paris and depose Napoleon. In the last week of February 1814, Prussian Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army (in countries without the rank of Generalissimo), and as such, few persons a ...

Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher

Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher (; 21 December 1742 – 12 September 1819), ''Graf'' (count), later elevated to ''Fürst'' (prince) von Wahlstatt, was a Kingdom of Prussia, Prussian ''Generalfeldmarschall'' (field marshal). He earned his greatest ...

advanced on Paris. After multiple attacks, manoeuvring, and reinforcements on both sides, Blücher won the Battle of Laon in early March 1814; this victory prevented the coalition army from being pushed north out of France. The Battle of Reims went to Napoleon, but this victory was followed by successive defeats from increasingly overwhelming odds. Coalition forces entered Paris after the Battle of Montmartre on 30 March 1814.

On 6 April 1814, Napoleon abdicated his throne, leading to the accession of Louis XVIII

Louis XVIII (Louis Stanislas Xavier; 17 November 1755 – 16 September 1824), known as the Desired (), was King of France from 1814 to 1824, except for a brief interruption during the Hundred Days in 1815. Before his reign, he spent 23 y ...

and the first Bourbon Restoration a month later. The defeated Napoleon was exiled to the island of Elba

Elba (, ; ) is a Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean island in Tuscany, Italy, from the coastal town of Piombino on the Italian mainland, and the largest island of the Tuscan Archipelago. It is also part of the Arcipelago Toscano National Park, a ...

off the coast of Tuscany

Tuscany ( ; ) is a Regions of Italy, region in central Italy with an area of about and a population of 3,660,834 inhabitants as of 2025. The capital city is Florence.

Tuscany is known for its landscapes, history, artistic legacy, and its in ...

, while the victorious Coalition sought to redraw the map of Europe at the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon, Napol ...

.

Exile in Elba

Napoleon spent only 9 months and 21 days in an uneasy forced retirement on Elba (1814–1815), watching events in France with great interest as the Congress of Vienna gradually gathered. As he foresaw, the shrinkage of the greatEmpire

An empire is a political unit made up of several territories, military outpost (military), outposts, and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a hegemony, dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the ...

into the realm of old France caused intense dissatisfaction among the French, a feeling fed by stories of the tactless way in which the Bourbon princes treated veterans of the ''Grande Armée

The (; ) was the primary field army of the French Imperial Army (1804–1815), French Imperial Army during the Napoleonic Wars. Commanded by Napoleon, from 1804 to 1808 it won a series of military victories that allowed the First French Empi ...

'' and the returning royalist nobility treated the people at large. Equally threatening was the general situation in Europe, which had been stressed and exhausted during the previous decades of near constant warfare.

The conflicting demands of major powers were for a time so exorbitant as to bring the Powers at the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon, Napol ...

to the verge of war with each other. Thus every scrap of news reaching remote Elba looked favourable to Napoleon to retake power as he correctly reasoned the news of his return would cause a popular rising as he approached. He also reasoned that the return of French prisoners from Russia, Germany, Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

and Spain would furnish him instantly with a trained, veteran and patriotic army far larger than that which had won renown in the years before 1814. So threatening were the symptoms, that the royalists at Paris and the plenipotentiaries at Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

talked of deporting him to the Azores

The Azores ( , , ; , ), officially the Autonomous Region of the Azores (), is one of the two autonomous regions of Portugal (along with Madeira). It is an archipelago composed of nine volcanic islands in the Macaronesia region of the North Atl ...

or to Saint Helena

Saint Helena (, ) is one of the three constituent parts of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha, a remote British overseas territory.

Saint Helena is a volcanic and tropical island, located in the South Atlantic Ocean, some 1,874 km ...

, while others hinted at assassination.

Congress of Vienna

At theCongress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon, Napol ...

(November 1814 – June 1815) the various participating nations had very different and conflicting goals. Tsar Alexander I of Russia had expected to absorb much of Poland and to leave a Polish puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government is a State (polity), state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside Power (international relations), power and subject to its ord ...

, the Duchy of Warsaw

The Duchy of Warsaw (; ; ), also known as the Grand Duchy of Warsaw and Napoleonic Poland, was a First French Empire, French client state established by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1807, during the Napoleonic Wars. It initially comprised the ethnical ...

, as a buffer against further invasion from Europe. The renewed Prussian state demanded all of the Kingdom of Saxony

The Kingdom of Saxony () was a German monarchy in Central Europe between 1806 and 1918, the successor of the Electorate of Saxony. It joined the Confederation of the Rhine after the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, later joining the German ...

. Austria wanted to allow neither of these things, while it expected to regain control of northern Italy. Castlereagh, of the United Kingdom, supported France (represented by Talleyrand) and Austria and was at variance with his own Parliament. This almost caused a war to break out, when the Tsar pointed out to Castlereagh that Russia had 450,000 men near Poland and Saxony and he was welcome to try to remove them. Indeed, Alexander stated "I shall be the King of Poland and the King of Prussia will be the King of Saxony". Castlereagh approached King Frederick William III of Prussia to offer him British and Austrian support for Prussia's annexation of Saxony in return for Prussia's support of an independent Poland. The Prussian king repeated this offer in public, offending Alexander so deeply that he challenged Metternich

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein ( ; 15 May 1773 – 11 June 1859), known as Klemens von Metternich () or Prince Metternich, was a Germans, German statesman and diplomat in the service of the Austrian ...

of Austria to a duel. Only the intervention of the Austrian crown stopped it. A breach among the four Great Powers was avoided when members of Britain's Parliament sent word to the Russian ambassador that Castlereagh had exceeded his authority, and Britain would not support an independent Poland. The affair left Prussia deeply suspicious of any British involvement.

Return to France

While the Allies were distracted, Napoleon solved his problem in characteristic fashion. On 26 February 1815, when the British and French guard ships were absent, his tiny fleet, consisting of the brig ''Inconstant'', four small transports, and two feluccas, slipped away from Portoferraio with some 1,000 men and landed at Golfe-Juan, betweenCannes

Cannes (, ; , ; ) is a city located on the French Riviera. It is a communes of France, commune located in the Alpes-Maritimes departments of France, department, and host city of the annual Cannes Film Festival, Midem, and Cannes Lions Internatio ...

and Antibes

Antibes (, , ; ) is a seaside city in the Alpes-Maritimes Departments of France, department in Southeastern France. It is located on the French Riviera between Cannes and Nice; its cape, the Cap d'Antibes, along with Cap Ferrat in Saint-Jean-Ca ...

, on 1 March 1815. Except in royalist Provence

Provence is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which stretches from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the France–Italy border, Italian border to the east; it is bordered by the Mediterrane ...

, he was warmly received. He avoided much of Provence by taking a route through the Alps, marked today as the '' Route Napoléon''.

Firing no shot in his defence, his troop numbers swelled until they became an army. On 5 March, the nominally royalist 5th Infantry Regiment at Grenoble

Grenoble ( ; ; or ; or ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of the Isère Departments of France, department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes Regions of France, region ...

went over to Napoleon ''en masse''. The next day they were joined by the 7th Infantry Regiment under its colonel, Charles de la Bédoyère, who would be executed for treason by the Bourbons after the campaign ended. An anecdote illustrates Napoleon's charisma: when royalist troops were deployed to stop the march of Napoleon's force before Grenoble at Laffrey, Napoleon stepped out in front of them, ripped open his coat and said "If any of you will shoot his Emperor, here I am." The men joined his cause.

Marshal Ney, now one of Louis XVIII's commanders, had said that Napoleon ought to be brought to Paris in an iron cage, but, on 14 March, in Lons-le-Saulnier (Jura) Ney joined Napoleon with a small army of 6,000 men. On 15 March Joachim Murat

Joachim Murat ( , also ; ; ; 25 March 1767 – 13 October 1815) was a French Army officer and statesman who served during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Under the French Empire he received the military titles of Marshal of the ...

, King of Naples

The following is a list of rulers of the Kingdom of Naples, from its first Sicilian Vespers, separation from the Kingdom of Sicily to its merger with the same into the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

Kingdom of Naples (1282–1501)

House of Anjou

...

, declared war on Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

in an attempt to save his throne, starting the Neapolitan War

The Neapolitan War, also known as the Austro-Neapolitan War, was a conflict between the Napoleonic Kingdom of Naples (Napoleonic), Kingdom of Naples and the Austrian Empire. It started on 15 March 1815, when King Joachim Murat declared war on ...

. Four days later, after proceeding through the countryside promising constitutional reform and direct elections to an assembly, to the acclaim of gathered crowds, Napoleon entered the capital, from where Louis XVIII had recently fled. (Ney was arrested on 3 August 1815, tried on 16 November and executed on 7 December 1815.)

The royalists did not pose a major threat: the duc d'Angoulême raised a small force in the south, but at Valence it did not provide resistance against Imperialists under Grouchy's command; and the duke, on 9 April 1815, signed a convention whereby the royalists received a free pardon from the Emperor. The royalists of the Vendée

Vendée () is a department in the Pays de la Loire region in Western France, on the Atlantic coast. In 2019, it had a population of 685,442.Carnot, Pasquier, Lavalette, Thiébault and others thought him prematurely aged and enfeebled. At Elba Sir Neil Campbell had noted that he had become inactive and corpulent.

Also at Elba he had begun to suffer intermittently from retention of urine, but to no serious extent.

For much of his public life, Napoleon had been troubled by hemorrhoids, which made sitting on a horse for long periods of time difficult and painful. This condition had disastrous results at Waterloo; during the battle, his inability to sit on his horse for other than very short periods of time interfered with his ability to survey his troops in combat and thus exercise command.

Others reported no marked change in him. Mollien, who knew the emperor well, attributed the lassitude which now and then came over him to a feeling of perplexity caused by his changed circumstances.

During the Hundred Days the Coalition nations as well as Napoleon mobilised for war. Upon re-assumption of the throne, Napoleon found that Louis XVIII had left him with few resources. There were 56,000 soldiers, of which 46,000 were ready to campaign. By the end of May the total armed forces available to Napoleon had reached 198,000 with 66,000 more in depots training up but not yet ready for deployment. By the end of May Napoleon had formed '' L'Armée du Nord'' (the "Army of the North") which, led by himself, would participate in the

During the Hundred Days the Coalition nations as well as Napoleon mobilised for war. Upon re-assumption of the throne, Napoleon found that Louis XVIII had left him with few resources. There were 56,000 soldiers, of which 46,000 were ready to campaign. By the end of May the total armed forces available to Napoleon had reached 198,000 with 66,000 more in depots training up but not yet ready for deployment. By the end of May Napoleon had formed '' L'Armée du Nord'' (the "Army of the North") which, led by himself, would participate in the

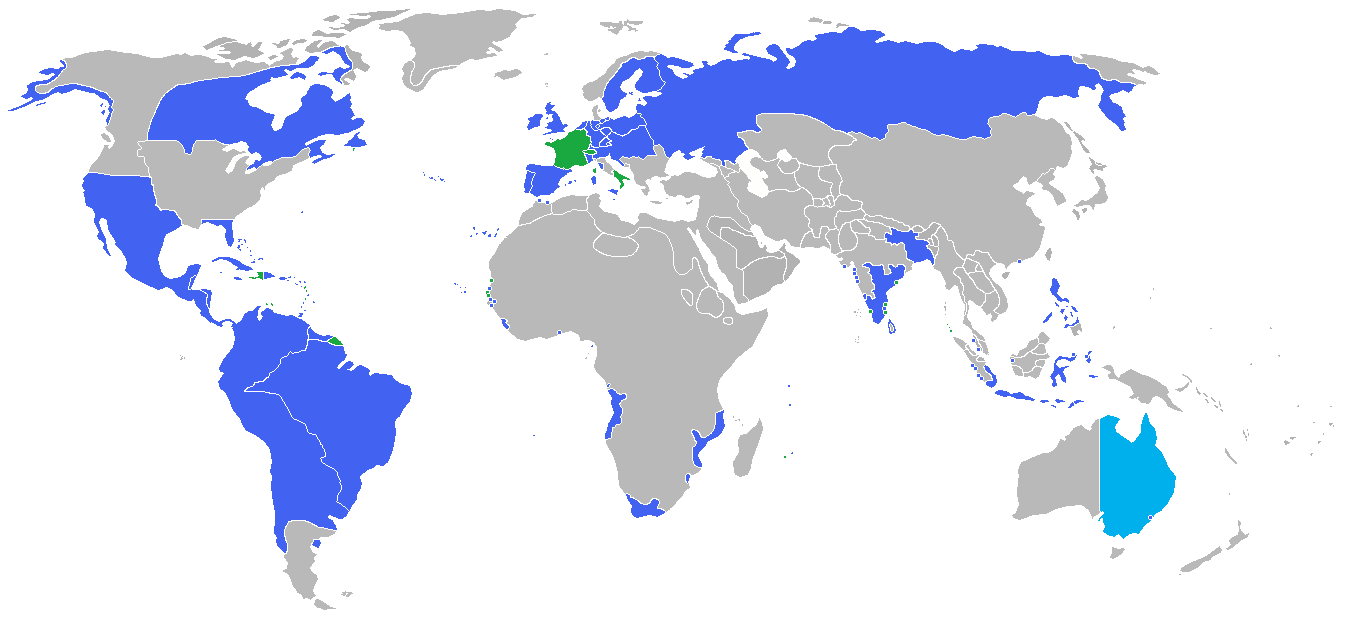

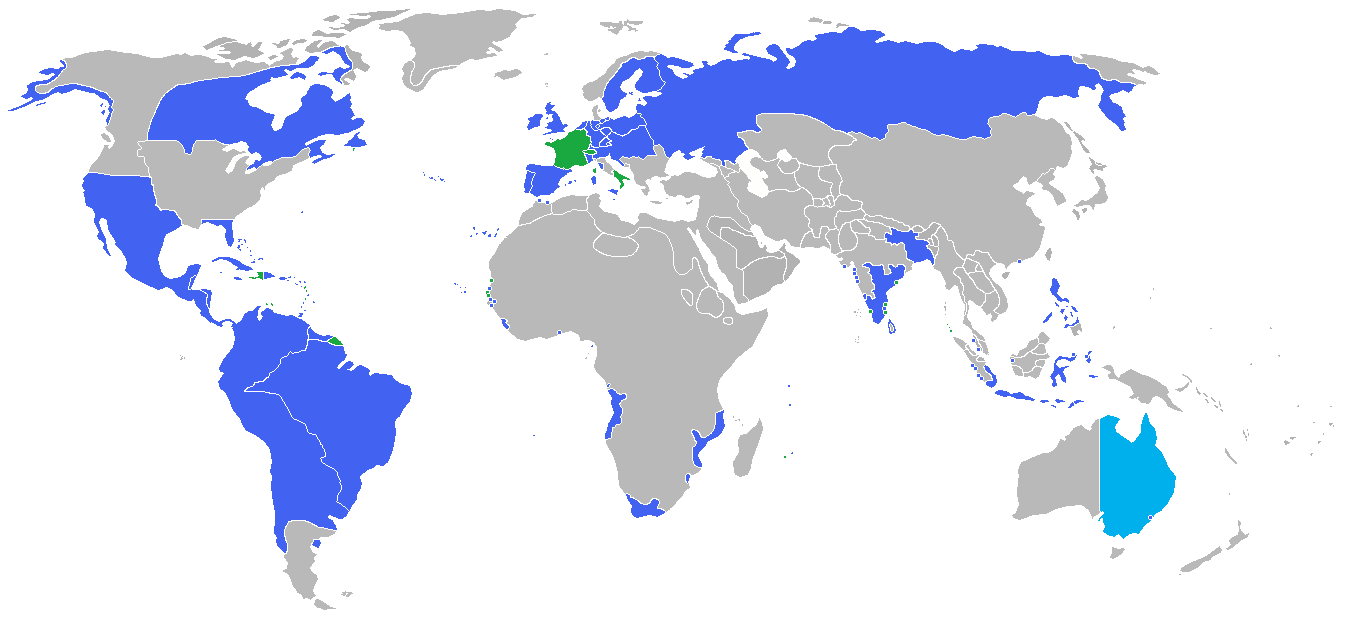

At the Congress of Vienna, the Great Powers of Europe (Austria, Great Britain, Prussia and Russia) and their allies declared Napoleon an outlaw, and with the signing of this declaration on 13 March 1815, so began the War of the Seventh Coalition. The hopes of peace that Napoleon had entertained were gone – war was now inevitable.

A further treaty (the Treaty of Alliance against Napoleon) was ratified on 25 March, in which each of the Great European Powers agreed to pledge 150,000 men for the coming conflict. Such a number was not possible for Great Britain, as her standing army was smaller than those of her three peers. Besides, her forces were scattered around the globe, with many units still in Canada, where the

At the Congress of Vienna, the Great Powers of Europe (Austria, Great Britain, Prussia and Russia) and their allies declared Napoleon an outlaw, and with the signing of this declaration on 13 March 1815, so began the War of the Seventh Coalition. The hopes of peace that Napoleon had entertained were gone – war was now inevitable.

A further treaty (the Treaty of Alliance against Napoleon) was ratified on 25 March, in which each of the Great European Powers agreed to pledge 150,000 men for the coming conflict. Such a number was not possible for Great Britain, as her standing army was smaller than those of her three peers. Besides, her forces were scattered around the globe, with many units still in Canada, where the

The

The

On 16 June, the French prevailed, with Marshal Ney commanding the left wing of the French army holding Wellington at the Battle of Quatre Bras and Napoleon defeating Blücher at the Battle of Ligny.

On 16 June, the French prevailed, with Marshal Ney commanding the left wing of the French army holding Wellington at the Battle of Quatre Bras and Napoleon defeating Blücher at the Battle of Ligny.

After the defeat at Waterloo, Napoleon chose not to remain with the army and attempt to rally it, but return to Paris to try to secure political support for further action. This he failed to do. The two Coalition armies hotly pursued the French army to the gates of Paris, during which time the French, on occasion, turned and fought some delaying actions, in which thousands of men were killed.

After the defeat at Waterloo, Napoleon chose not to remain with the army and attempt to rally it, but return to Paris to try to secure political support for further action. This he failed to do. The two Coalition armies hotly pursued the French army to the gates of Paris, during which time the French, on occasion, turned and fought some delaying actions, in which thousands of men were killed.

With the abdication of Napoleon, a provisional government with Joseph Fouché as President of the Executive Commission was formed, under the nominal authority of Napoleon II.

Initially, the remnants of the French Army of the North (the left wing and the reserves) that was routed at Waterloo were commanded by Marshal Soult, while Grouchy kept command of the right wing that had fought at Wavre. However, on 25 June, Soult was relieved of his command by the Provisional Government and was replaced by Grouchy, who in turn was placed under the command of Marshal Davout.

On the same day, 25 June, Napoleon received from Fouché, the president of the newly appointed provisional government (and Napoleon's former police chief), an intimation that he must leave Paris. He retired to Malmaison, the former home of Joséphine, where she had died shortly after his first abdication.

On 29 June, the near approach of the Prussians, who had orders to seize Napoleon, dead or alive, caused him to retire westwards toward Rochefort, whence he hoped to reach the United States. The presence of blockading

With the abdication of Napoleon, a provisional government with Joseph Fouché as President of the Executive Commission was formed, under the nominal authority of Napoleon II.

Initially, the remnants of the French Army of the North (the left wing and the reserves) that was routed at Waterloo were commanded by Marshal Soult, while Grouchy kept command of the right wing that had fought at Wavre. However, on 25 June, Soult was relieved of his command by the Provisional Government and was replaced by Grouchy, who in turn was placed under the command of Marshal Davout.

On the same day, 25 June, Napoleon received from Fouché, the president of the newly appointed provisional government (and Napoleon's former police chief), an intimation that he must leave Paris. He retired to Malmaison, the former home of Joséphine, where she had died shortly after his first abdication.

On 29 June, the near approach of the Prussians, who had orders to seize Napoleon, dead or alive, caused him to retire westwards toward Rochefort, whence he hoped to reach the United States. The presence of blockading

Unable to remain in France or escape from it, Napoleon surrendered to Captain

Unable to remain in France or escape from it, Napoleon surrendered to Captain

Issy was the last field engagement of the Hundred Days. There was a campaign against fortresses still commanded by Bonapartist governors that ended with the capitulation of Longwy on 13 September 1815. The Treaty of Paris was signed on 20 November 1815, bringing the

Issy was the last field engagement of the Hundred Days. There was a campaign against fortresses still commanded by Bonapartist governors that ended with the capitulation of Longwy on 13 September 1815. The Treaty of Paris was signed on 20 November 1815, bringing the

Constitutional reform

AtLyon

Lyon (Franco-Provençal: ''Liyon'') is a city in France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of the French Alps, southeast of Paris, north of Marseille, southwest of Geneva, Switzerland, north ...

, on 13 March 1815, Napoleon issued an edict dissolving the existing chambers and ordering the convocation of a national mass meeting, or Champ de Mai, for the purpose of modifying the constitution of the Napoleonic empire. He reportedly told Benjamin Constant

Henri-Benjamin Constant de Rebecque (25 October 1767 – 8 December 1830), or simply Benjamin Constant, was a Swiss and French political thinker, activist and writer on political theory and religion.

A committed republican from 1795, Constant ...

, "I am growing old. The repose of a constitutional king may suit me. It will more surely suit my son".

That work was carried out by Benjamin Constant in concert with the Emperor. The resulting (supplementary to the ''constitutions'' of the Empire) bestowed on France a hereditary Chamber of Peers and a Chamber of Representatives elected by the "electoral colleges" of the empire.

According to Chateaubriand, in reference to Louis XVIII's constitutional charter, the new constitution – dubbed ''La Benjamine'' – was merely a "slightly improved" version of the charter associated with Louis XVIII's administration; however, later historians, including Agatha Ramm, have pointed out that this constitution permitted the extension of the franchise and explicitly guaranteed press freedom

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic media, especially published materials, should be considered a right to be exerc ...

. In the Republican manner, the Constitution was put to the people of France in a plebiscite

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a direct vote by the electorate (rather than their representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either binding (resulting in the adoption of a new policy) or adv ...

, but whether due to lack of enthusiasm, or because the nation was suddenly thrown into military preparation, only 1,532,527 votes were cast, less than half of the vote in the plebiscites of the Consulat; however, the benefit of a "large majority" meant that Napoleon felt he had constitutional sanction.

Napoleon was with difficulty dissuaded from quashing the 3 June election of Jean Denis, comte Lanjuinais, the staunch liberal who had so often opposed the Emperor, as president of the Chamber of Representatives. In his last communication to them, Napoleon warned them not to imitate the Greeks of the late Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

, who engaged in subtle discussions while the ram was battering at their gates.

Military mobilisation

During the Hundred Days the Coalition nations as well as Napoleon mobilised for war. Upon re-assumption of the throne, Napoleon found that Louis XVIII had left him with few resources. There were 56,000 soldiers, of which 46,000 were ready to campaign. By the end of May the total armed forces available to Napoleon had reached 198,000 with 66,000 more in depots training up but not yet ready for deployment. By the end of May Napoleon had formed '' L'Armée du Nord'' (the "Army of the North") which, led by himself, would participate in the

During the Hundred Days the Coalition nations as well as Napoleon mobilised for war. Upon re-assumption of the throne, Napoleon found that Louis XVIII had left him with few resources. There were 56,000 soldiers, of which 46,000 were ready to campaign. By the end of May the total armed forces available to Napoleon had reached 198,000 with 66,000 more in depots training up but not yet ready for deployment. By the end of May Napoleon had formed '' L'Armée du Nord'' (the "Army of the North") which, led by himself, would participate in the Waterloo Campaign

The Waterloo campaign, also known as the Belgian campaign (15 June – 8 July 1815) was fought between the French Army of the North (France), Army of the North and two War of the Seventh Coalition, Seventh Coalition armies, an Anglo-allied arm ...

.

For the defence of France, Napoleon deployed his remaining forces within France with the intention of delaying his foreign enemies while he suppressed his domestic ones. By June he had organised his forces thus:

* V Corps, – ''L'Armée du Rhin'' – commanded by Rapp, cantoned near Strasbourg

Strasbourg ( , ; ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est Regions of France, region of Geography of France, eastern France, in the historic region of Alsace. It is the prefecture of the Bas-Rhin Departmen ...

;

* VII Corps – ''L' Armée des Alpes'' – commanded by Suchet, cantoned at Lyon;

* I Corps of Observation – ''L'Armée du Jura'' – commanded by Lecourbe, cantoned at Belfort;

* II Corps of Observation – ''L' Armée du Var'' – commanded by Brune, based at Toulon;

* III Corps of Observation – Army of the Pyrenees orientales – commanded by Decaen, based at Toulouse;

* IV Corps of Observation – Army of the Pyrenees occidentales – commanded by Clauzel, based at Bordeaux;

* Army of the West, – ''Armée de l'Ouest'' (also known as the Army of the Vendee and the Army of the Loire) – commanded by Lamarque, was formed to suppress the Royalist insurrection in the Vendée

Vendée () is a department in the Pays de la Loire region in Western France, on the Atlantic coast. In 2019, it had a population of 685,442.Louis XVIII

Louis XVIII (Louis Stanislas Xavier; 17 November 1755 – 16 September 1824), known as the Desired (), was King of France from 1814 to 1824, except for a brief interruption during the Hundred Days in 1815. Before his reign, he spent 23 y ...

during the Hundred Days.

The opposing Coalition forces were the following:

Archduke Charles gathered Austrian and allied German states, while the Prince of Schwarzenberg formed another Austrian army. King Ferdinand VII of Spain

Ferdinand VII (; 14 October 1784 – 29 September 1833) was Monarchy of Spain, King of Spain during the early 19th century. He reigned briefly in 1808 and then again from 1813 to his death in 1833. Before 1813 he was known as ''el Deseado'' (t ...

summoned British officers to lead his troops against France. Tsar Alexander I of Russia

Alexander I (, ; – ), nicknamed "the Blessed", was Emperor of Russia from 1801, the first king of Congress Poland from 1815, and the grand duke of Finland from 1809 to his death in 1825. He ruled Russian Empire, Russia during the chaotic perio ...

mustered an army of 250,000 troops and sent these rolling toward the Rhine. Prussia mustered two armies. One under Blücher took post alongside Wellington's British army and its allies. The other was the North German Corps under General Kleist.

* Assessed as an immediate threat by Napoleon:

** Anglo-allied, commanded by Wellington, cantoned south-west of Brussels, headquartered at Brussels.

** Prussian Army commanded by Blücher, cantoned south-east of Brussels, headquartered at Namur.

* Close to the borders of France but assessed to be less of a threat by Napoleon:

** The German Corps (North German Federal Army) which was part of Blücher's army, but was acting independently south of the main Prussian army. Blücher summoned it to join the main army once Napoleon's intentions became known.

** The Austrian Army of the Upper Rhine, commanded by Field Marshal Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwarzenberg.

** The Swiss Army, commanded by Niklaus Franz von Bachmann.

** The Austrian Army of Upper Italy – Austro-Sardinian Army – commanded by Johann Maria Philipp Frimont

Johann Maria Philipp Frimont, ''Count of Palota, Prince of Antrodoco'' (3 February 1759 – 26 December 1831) was an Austrian general.

Frimont was born at Fénétrange, in the Duchy of Lorraine. He entered the Austrian cavalry as a trooper i ...

.

** The Austrian Army of Naples, commanded by Frederick Bianchi, Duke of Casalanza.

* Other coalition forces which were either converging on France, mobilised to defend the homelands, or in the process of mobilisation included:

** A Russian Army, commanded by Michael Andreas Barclay de Tolly

Prince Michael Andreas Barclay de Tolly (baptised – ) was a Russian field marshal who figured prominently in the Napoleonic Wars.

Barclay was born into a Baltic German family from Livland. His father was the first of his family to be accep ...

, marching towards France

** A Reserve Russian Army to support Barclay de Tolly if required.

** A Reserve Prussian Army stationed at home in order to defend its borders.

** An Anglo-Sicilian Army under General Sir Hudson Lowe, which was to be landed by the Royal Navy on the southern French coast.

** Two Spanish Armies were assembling and planning to invade over the Pyrenees.

** A Netherlands Corps, under Prince Frederick of the Netherlands, was not present at Waterloo but as a corps in Wellington's army it did take part in minor military actions during the Coalition's invasion of France.

** A Danish contingent known as the Royal Danish Auxiliary Corps (commanded by General Prince Frederik of Hesse

Prince Frederik of Hesse, Landgrave Friedrich of Hesse-Cassel (24 May 1771 – 24 February 1845) was a Danish- German nobleman, field marshal and governor-general of Norway (1810–1813) and the same in the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein ...

) and a Hanseatic contingent (from the free cities of Bremen, Lübeck and Hamburg) later commanded by the British Colonel Sir Neil Campbell, were on their way to join Wellington; both however, joined the army in July having missed the conflict.

** A Portuguese contingent, which due to the speed of events never assembled.

War begins

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

had recently ended. With this in mind, she made up her numerical deficiencies by paying subsidies to the other Powers and to the other states of Europe who would contribute contingents.

Some time after the allies had begun mobilising, it was agreed that the planned invasion of France was to commence on 1 July 1815, much later than both Blücher and Wellington would have liked, as both their armies were ready in June, ahead of the Austrians and Russians; the latter were still some distance away. The advantage of this later invasion date was that it allowed all the invading Coalition armies a chance to be ready at the same time. They could deploy their combined, numerically superior forces against Napoleon's smaller, thinly spread forces, thus ensuring his defeat and avoiding a possible defeat within the borders of France. Yet this postponed invasion date allowed Napoleon more time to strengthen his forces and defences, which would make defeating him harder and more costly in lives, time and money.

Napoleon now had to decide whether to fight a defensive or offensive campaign. Defence would entail repeating the 1814 campaign in France, but with much larger numbers of troops at his disposal. France's chief cities (Paris and Lyon) would be fortified and two great French armies, the larger before Paris and the smaller before Lyon, would protect them; ''francs-tireurs

(; ) were irregular military formations deployed by France during the early stages of the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71). The term was revived and used by partisans to name two major French Resistance movements set up to fight against Nazi G ...

'' would be encouraged, giving the Coalition armies their own taste of guerrilla warfare.

Napoleon chose to attack, which entailed a pre-emptive strike at his enemies before they were all fully assembled and able to co-operate. By destroying some of the major Coalition armies, Napoleon believed he would then be able to bring the governments of the Seventh Coalition to the peace table to discuss terms favourable to himself: namely, peace for France, with himself remaining in power as its head. If peace were rejected by the Coalition powers, despite any pre-emptive military success he might have achieved using the offensive military option available to him, then the war would continue and he could turn his attention to defeating the rest of the Coalition armies.

Napoleon's decision to attack in Belgium was supported by several considerations. First, he had learned that the British and Prussian armies were widely dispersed and might be defeated in detail. Further, the British troops in Belgium were largely second-line troops; most of the veterans of the Peninsular War

The Peninsular War (1808–1814) was fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Kingdom of Portugal, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French ...

had been sent to America to fight the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

. And, politically, a French victory might trigger a friendly revolution in French-speaking Brussels.

Waterloo campaign

The

The Waterloo Campaign

The Waterloo campaign, also known as the Belgian campaign (15 June – 8 July 1815) was fought between the French Army of the North (France), Army of the North and two War of the Seventh Coalition, Seventh Coalition armies, an Anglo-allied arm ...

(15 June – 8 July 1815) was fought between the French Army of the North

The Army of the North (), contemporaneously called Army of Peru (), was one of the armies deployed by the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata in the Spanish American wars of independence. Its objective was freeing the Argentine Northwest a ...

and two Seventh Coalition armies: an Anglo-allied army and a Prussian army. Initially the French army was commanded by Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

, but he left for Paris after the French defeat at the Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo, Belgium, Waterloo (then in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium), marking the end of the Napoleonic Wars. The French Imperial Army (1804–1815), Frenc ...

. Command then rested on Marshals Soult

Marshal General of France, Marshal General Jean-de-Dieu Soult, 1st Duke of Dalmatia (; 29 March 1769 – 26 November 1851) was a French general and statesman. He was a Marshal of the Empire during the Napoleonic Wars, and served three times as P ...

and Grouchy, who were in turn replaced by Marshal Davout, who took command at the request of the French Provisional Government. The Anglo-allied army was commanded by the Duke of Wellington and the Prussian army by Prince Blücher.

Start of hostilities (15 June)

Hostilities started on 15 June when the French drove in the Prussian outposts and crossed theSambre

The Sambre () is a river in northern France and in Wallonia, Belgium. It is a left-bank tributary of the Meuse, which it joins in the Wallonian capital Namur.

The source of the Sambre is near Le Nouvion-en-Thiérache, in the Aisne department. ...

at Charleroi

Charleroi (, , ; ) is a city and a municipality of Wallonia, located in the province of Hainaut, Belgium. It is the largest city in both Hainaut and Wallonia. The city is situated in the valley of the Sambre, in the south-west of Belgium, not ...

and secured Napoleon's favoured "central position"—at the junction between the cantonment areas of Wellington's army (to the west) and Blücher's army to the east.

Battles of Quatre Bras and Ligny (16 June)

Interlude (17 June)

On 17 June, Napoleon left Grouchy with the right wing of the French army to pursue the Prussians, while he took the reserves and command of the left wing of the army to pursue Wellington towards Brussels. On the night of 17 June, the Anglo-allied army turned and prepared for battle on a gentle escarpment, about south of the village of Waterloo.Battle of Waterloo (18 June)

The next day, the Battle of Waterloo proved to be the decisive battle of the campaign. The Anglo-allied army stood fast against repeated French attacks, until with the aid of several Prussian corps that arrived on the east of the battlefield in the early evening, they managed to rout the French Army. Grouchy, with the right wing of the army, engaged a Prussian rearguard at the simultaneous Battle of Wavre, and although he won a tactical victory, his failure to prevent the Prussians marching to Waterloo meant that his actions contributed to the French defeat at Waterloo. The next day (19 June), Grouchy left Wavre and started a long retreat back to Paris.Invasion of France

After the defeat at Waterloo, Napoleon chose not to remain with the army and attempt to rally it, but return to Paris to try to secure political support for further action. This he failed to do. The two Coalition armies hotly pursued the French army to the gates of Paris, during which time the French, on occasion, turned and fought some delaying actions, in which thousands of men were killed.

After the defeat at Waterloo, Napoleon chose not to remain with the army and attempt to rally it, but return to Paris to try to secure political support for further action. This he failed to do. The two Coalition armies hotly pursued the French army to the gates of Paris, during which time the French, on occasion, turned and fought some delaying actions, in which thousands of men were killed.

Abdication of Napoleon (22 June)

On arriving at Paris, three days after Waterloo, Napoleon still clung to the hope of concerted national resistance, but the temper of the chambers and of the public generally forbade any such attempt. Napoleon and his brother Lucien Bonaparte were almost alone in believing that, by dissolving the chambers and declaring Napoleon dictator, they could save France from the armies of the powers now converging on Paris. Even Davout, minister of war, advised Napoleon that the destiny of France rested solely with the chambers. Clearly, it was time to safeguard what remained, and that could best be done under Talleyrand's shield of legitimacy. Jean Jacques Régis de Cambacérès was the minister of justice during this time and was a close confidant of Napoleon. Napoleon himself at last recognised the truth. When Lucien pressed him to "dare", he replied, "Alas, I have dared only too much already". On 22 June 1815 he abdicated in favour of his son,Napoleon II

Napoleon II (Napoléon François Joseph Charles Bonaparte; 20 March 181122 July 1832) was the disputed Emperor of the French for a few weeks in 1815. He was the son of Emperor Napoleon I and Empress Marie Louise, Duchess of Parma, Marie Louise, d ...

, well knowing that it was a formality, as his four-year-old son was in Austria.

French Provisional Government

With the abdication of Napoleon, a provisional government with Joseph Fouché as President of the Executive Commission was formed, under the nominal authority of Napoleon II.

Initially, the remnants of the French Army of the North (the left wing and the reserves) that was routed at Waterloo were commanded by Marshal Soult, while Grouchy kept command of the right wing that had fought at Wavre. However, on 25 June, Soult was relieved of his command by the Provisional Government and was replaced by Grouchy, who in turn was placed under the command of Marshal Davout.

On the same day, 25 June, Napoleon received from Fouché, the president of the newly appointed provisional government (and Napoleon's former police chief), an intimation that he must leave Paris. He retired to Malmaison, the former home of Joséphine, where she had died shortly after his first abdication.

On 29 June, the near approach of the Prussians, who had orders to seize Napoleon, dead or alive, caused him to retire westwards toward Rochefort, whence he hoped to reach the United States. The presence of blockading

With the abdication of Napoleon, a provisional government with Joseph Fouché as President of the Executive Commission was formed, under the nominal authority of Napoleon II.

Initially, the remnants of the French Army of the North (the left wing and the reserves) that was routed at Waterloo were commanded by Marshal Soult, while Grouchy kept command of the right wing that had fought at Wavre. However, on 25 June, Soult was relieved of his command by the Provisional Government and was replaced by Grouchy, who in turn was placed under the command of Marshal Davout.

On the same day, 25 June, Napoleon received from Fouché, the president of the newly appointed provisional government (and Napoleon's former police chief), an intimation that he must leave Paris. He retired to Malmaison, the former home of Joséphine, where she had died shortly after his first abdication.

On 29 June, the near approach of the Prussians, who had orders to seize Napoleon, dead or alive, caused him to retire westwards toward Rochefort, whence he hoped to reach the United States. The presence of blockading Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

warships under Vice Admiral Henry Hotham, with orders to prevent his escape, forestalled this plan.

Coalition forces enter Paris (7 July)

French troops concentrated in Paris had as many soldiers as the invaders and more cannons. There were two major skirmishes and a few minor ones near Paris during the first few days of July. In the first major skirmish, the Battle of Rocquencourt, on 1 July, French dragoons, supported by infantry and commanded by General Exelmans, destroyed a Prussian brigade of hussars under the command of Colonel von Sohr (who was severely wounded and taken prisoner during the skirmish), before retreating. In the second skirmish, on 3 July, General Dominique Vandamme (under Davout's command) was decisively defeated by General von Zieten (under Blücher's command) at theBattle of Issy

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

, forcing the French to retreat into Paris.

With this defeat, all hope of holding Paris faded and the French Provisional Government authorised delegates to accept capitulation terms, which led to the Convention of St. Cloud (the surrender of Paris) and the end of hostilities between France and the armies of Blücher and Wellington.

On 4 July, under the terms of the Convention of St. Cloud, the French army, commanded by Marshal Davout, left Paris and proceeded to cross the river Loire

The Loire ( , , ; ; ; ; ) is the longest river in France and the 171st longest in the world. With a length of , it drains , more than a fifth of France's land, while its average discharge is only half that of the Rhône.

It rises in the so ...

. The Anglo-allied troops occupied Saint-Denis, Saint Ouen, Clichy and Neuilly. On 5 July, the Anglo-allied army took possession of Montmartre

Montmartre ( , , ) is a large hill in Paris's northern 18th arrondissement of Paris, 18th arrondissement. It is high and gives its name to the surrounding district, part of the Rive Droite, Right Bank. Montmartre is primarily known for its a ...

. On 6 July, the Anglo-allied troops occupied the Barriers of Paris, on the right of the Seine, while the Prussians occupied those upon the left bank.

On 7 July, the two Coalition armies, with von Zieten's Prussian I Corps as the vanguard, entered Paris. The Chamber of Peers, having received from the Provisional Government a notification of the course of events, terminated its sittings; the Chamber of Representatives protested, but in vain. Their President (Lanjuinais) resigned his chair, and on the following day, the doors were closed and the approaches guarded by Coalition troops.

Restoration of Louis XVIII (8 July)

On 8 July, the French King, Louis XVIII, made his public entry into Paris, amidst the acclamations of the people, and again occupied the throne. During Louis XVIII's entry into Paris, Count Chabrol, prefect of the department of the Seine, accompanied by the municipal body, addressed the King, in the name of his companions, in a speech that began "Sire,—One hundred days have passed away since your majesty, forced to tear yourself from your dearest affections, left your capital amidst tears and public consternation. ...".Surrender of Napoleon (15 July)

Unable to remain in France or escape from it, Napoleon surrendered to Captain

Unable to remain in France or escape from it, Napoleon surrendered to Captain Frederick Maitland

General Frederick Maitland (3 September 1763 – 27 January 1848) was a British Army officer who fought during the American War of Independence, the Peninsular War and later served as Lieutenant Governor of Dominica.

Life

The youngest son ...

of in the early morning of 15 July 1815 and was transported to England. Napoleon was taken to the island of Saint Helena

Saint Helena (, ) is one of the three constituent parts of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha, a remote British overseas territory.

Saint Helena is a volcanic and tropical island, located in the South Atlantic Ocean, some 1,874 km ...

where he died as a prisoner in May 1821.

Other campaigns and wars

While Napoleon had assessed that the Coalition forces in and around Brussels on the borders of north-east France posed the greatest threat, because Tolly's Russian army of 150,000 were still not in the theatre, Spain was slow to mobilise, Prince Schwarzenberg's Austrian army of 210,000 were slow to cross the Rhine, and another Austrian force menacing the south-eastern frontier of France was still not a direct threat, Napoleon still had to place some badly needed forces in positions where they could defend France against other Coalition forces whatever the outcome of the Waterloo campaign.Neapolitan War

TheNeapolitan War

The Neapolitan War, also known as the Austro-Neapolitan War, was a conflict between the Napoleonic Kingdom of Naples (Napoleonic), Kingdom of Naples and the Austrian Empire. It started on 15 March 1815, when King Joachim Murat declared war on ...

between the Napoleonic Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples (; ; ), officially the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was established by the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1302). Until ...

and the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

started on 15 March 1815 when Marshal Joachim Murat

Joachim Murat ( , also ; ; ; 25 March 1767 – 13 October 1815) was a French Army officer and statesman who served during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Under the French Empire he received the military titles of Marshal of the ...

declared war on Austria, and ended on 20 May 1815 with the signing of the Treaty of Casalanza.

Napoleon had made his brother-in-law, Joachim Murat, King of Naples on 1 August 1808. After Napoleon's defeat in 1813, Murat reached an agreement with Austria to save his own throne. However, he realized that the European Powers, meeting as the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon, Napol ...

, planned to remove him and return Naples to its Bourbon rulers. So, after issuing the so-called Rimini Proclamation

The Rimini Proclamation () was a proclamation by Joachim Murat, King of Naples, calling for the establishment of a united, self-governing Italy ruled by constitutional law. Its text is widely attributed to Pellegrino Rossi, later Papal Minister ...

urging Italian patriots to fight for independence, Murat moved north to fight against the Austrians, who were the greatest threat to his rule.

The war was triggered by a pro-Napoleon uprising in Naples, after which Murat declared war on Austria on 15 March 1815, five days before Napoleon's return to Paris. The Austrians were prepared for war. Their suspicions were aroused weeks earlier, when Murat applied for permission to march through Austrian territory to attack the south of France. Austria had reinforced her armies in Lombardy

The Lombardy Region (; ) is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in northern Italy and has a population of about 10 million people, constituting more than one-sixth of Italy's population. Lombardy is ...

under the command of Bellegarde prior to war being declared.

The war ended after a decisive Austrian victory at the Battle of Tolentino. Ferdinand IV was reinstated as King of Naples. Ferdinand then sent Neapolitan troops under General Onasco to help the Austrian army in Italy attack southern France. In the long term, the intervention by Austria caused resentment in Italy, which further spurred on the drive towards Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( ), also known as the Risorgimento (; ), was the 19th century political and social movement that in 1861 ended in the annexation of various states of the Italian peninsula and its outlying isles to the Kingdom of ...

.

Civil war

Provence

Provence is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which stretches from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the France–Italy border, Italian border to the east; it is bordered by the Mediterrane ...

and Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

, which were known to contain many royalist sympathisers, did not rise in open revolt, but La Vendée did. The Vendée Royalists successfully took Bressuire and Cholet, before they were defeated by General Lamarque at the Battle of Rocheserviere on 20 June. They signed the Treaty of Cholet six days later on 26 June.

Austrian campaign

Rhine frontier

In early June, General Rapp's Army of the Rhine of about 23,000 men, with a leavening of experienced troops, advanced towardsGermersheim

Germersheim () is a town in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate, of around 20,000 inhabitants. It is also the seat of the Germersheim (district), Germersheim district. The neighboring towns and cities are Speyer, Landau, Philippsburg, Karlsru ...

to block Schwarzenberg's expected advance, but on hearing the news of the French defeat at Waterloo, Rapp withdrew towards Strasbourg turning on 28 June to check the 40,000 men of General Württemberg's Austrian III Corps at the Battle of La Suffel—the last pitched battle of the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

and a French victory. The next day Rapp continued to retreat to Strasbourg and also sent a garrison to defend Colmar

Colmar (; ; or ) is a city and commune in the Haut-Rhin department and Alsace region of north-eastern France. The third-largest commune in Alsace (after Strasbourg and Mulhouse), it is the seat of the prefecture of the Haut-Rhin department ...

. He and his men took no further active part in the campaign and eventually submitted to the Bourbons.

To the north of Württenberg's III Corps, General Wrede's Austrian (Bavarian) IV Corps also crossed the French frontier, and then swung south and captured Nancy, against some local popular resistance on 27 June. Attached to his command was a Russian detachment, under the command of General Count Lambert, that was charged with keeping Wrede's lines of communication open. In early July, Schwarzenberg, having received a request from Wellington and Blücher, ordered Wrede to act as the Austrian vanguard and advance on Paris, and by 5 July, the main body of Wrede's IV Corps had reached Châlons. On 6 July, the advance guard made contact with the Prussians, and on 7 July Wrede received intelligence of the Paris Convention and a request to move to the Loire. By 10 July, Wrede's headquarters were at Ferté-sous-Jouarre and his corps positioned between the Seine and the Marne.

Further south, General Colloredo's Austrian I Corps was hindered by General Lecourbe's ''Armée du Jura'', which was largely made up of National Guardsmen and other reserves. Lecourbe fought four delaying actions between 30 June and 8 July at Foussemagne, Bourogne, Chèvremont and Bavilliers before agreeing to an armistice on 11 July. Archduke Ferdinand's Reserve Corps, together with Hohenzollern-Hechingen's II Corps, laid siege to the fortresses of Hüningen and Mühlhausen

Mühlhausen () is a town in the north-west of Thuringia, Germany, north of Niederdorla, the country's Central Germany (geography)#Geographical centre, geographical centre, north-west of Erfurt, east of Kassel and south-east of Göttingen ...

, with two Swiss brigades from the Swiss Army of General Niklaus Franz von Bachmann, aiding with the siege of Huningen. Like other Austrian forces, these too were pestered by ''francs-tireurs''.

Italian frontier

Like Rapp further north, Marshal Suchet, with the ''Armée des Alpes'', took the initiative and on 14 June invadedSavoy

Savoy (; ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps. Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south and west and to the Aosta Vall ...

. Facing him was General Frimont, with an Austro-Sardinian army of 75,000 men based in Italy. However, on hearing of the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo, Suchet negotiated an armistice and fell back to Lyon

Lyon (Franco-Provençal: ''Liyon'') is a city in France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of the French Alps, southeast of Paris, north of Marseille, southwest of Geneva, Switzerland, north ...

s, where on 12 July he surrendered the city to Frimont's army.

The coast of Provence

Provence is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which stretches from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the France–Italy border, Italian border to the east; it is bordered by the Mediterrane ...

was defended by French forces under Marshal Brune, who fell back slowly into the fortress city of Toulon

Toulon (, , ; , , ) is a city in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the French Riviera and the historical Provence, it is the prefecture of the Var (department), Var department.

The Commune of Toulon h ...

, after retreating from Marseilles before the Austrian Army of Naples under the command of General Bianchi, the Anglo-Sicilian forces of Sir Hudson Lowe, supported by the British Mediterranean fleet of Lord Exmouth, and the Sardinian forces of the Sardinian General d'Osasco, the forces of the latter being drawn from the garrison of Nice. Brune did not surrender the city and its naval arsenal until 31 July.

Russian campaign

The main body of the Russian Army, commanded by Field Marshal Count Tolly and amounting to 167,950 men, crossed the Rhine atMannheim

Mannheim (; Palatine German language, Palatine German: or ), officially the University City of Mannheim (), is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, second-largest city in Baden-Württemberg after Stuttgart, the States of Ger ...

on 25 June—after Napoleon had abdicated for the second time—and although there was light resistance around Mannheim, it was over by the time the vanguard had advanced as far as Landau

Landau (), officially Landau in der Pfalz (, ), is an autonomous (''kreisfrei'') town surrounded by the Südliche Weinstraße ("Southern Wine Route") district of southern Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It is a university town (since 1990), a long ...

. The greater portion of Tolly's army reached Paris and its vicinity by the middle of July.

Treaty of Paris

Issy was the last field engagement of the Hundred Days. There was a campaign against fortresses still commanded by Bonapartist governors that ended with the capitulation of Longwy on 13 September 1815. The Treaty of Paris was signed on 20 November 1815, bringing the

Issy was the last field engagement of the Hundred Days. There was a campaign against fortresses still commanded by Bonapartist governors that ended with the capitulation of Longwy on 13 September 1815. The Treaty of Paris was signed on 20 November 1815, bringing the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

to a formal end.

Under the 1815 Paris treaty, the previous year's Treaty of Paris and the Final Act of the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon, Napol ...

, of 9 June 1815, were confirmed. France was reduced to its 1790 boundaries; it lost the territorial gains of the Revolutionary armies in 1790–1792, which the previous Paris treaty had allowed France to keep. France was now also ordered to pay 700 million francs in indemnities, in five yearly installments, and to maintain at its own expense a Coalition army of occupation of 150,000 soldiers in the eastern border territories of France, from the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

to the border with Switzerland, for a maximum of five years. The two-fold purpose of the military occupation was made clear by the convention annexed to the treaty, outlining the incremental terms by which France would issue negotiable bonds covering the indemnity: in addition to safeguarding the neighbouring states from a revival of revolution in France, it guaranteed fulfilment of the treaty's financial clauses.

On the same day, in a separate document, Great Britain, Russia, Austria and Prussia renewed the Quadruple Alliance. The princes and free towns who were not signatories were invited to accede to its terms,Final Act of the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon, Napol ...

, Article 119. whereby the treaty became a part of the public law according to which Europe, with the exception of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, established "relations from which a system of real and permanent balance of power in Europe is to be derived".

Timeline of French constitutions

See also

* Malplaquet proclamation issued to French by Wellington on 22 June 1815 * Napoleon I's first abdication * Lists of battles of the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars ** List of battles of the Hundred DaysNotes

References

Citations

Works cited

* * * * * * * (also published as: ''Vers la neutralité et l'indépendance. La Suisse en 1814 et 1815'', Berne: Commissariat central des guerres) * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Attribution

* *Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * * * {{Authority control 1815 in France Conflicts in 1815 Napoleonic Wars