Human genetic variation is the genetic differences in and among

population

Population is a set of humans or other organisms in a given region or area. Governments conduct a census to quantify the resident population size within a given jurisdiction. The term is also applied to non-human animals, microorganisms, and pl ...

s. There may be multiple variants of any given gene in the human population (

allele

An allele is a variant of the sequence of nucleotides at a particular location, or Locus (genetics), locus, on a DNA molecule.

Alleles can differ at a single position through Single-nucleotide polymorphism, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP), ...

s), a situation called

polymorphism.

No two humans are genetically identical. Even

monozygotic twins

Twins are two offspring produced by the same pregnancy.MedicineNet > Definition of Twin Last Editorial Review: 19 June 2000 Twins can be either ''monozygotic'' ('identical'), meaning that they develop from one zygote, which splits and forms two e ...

(who develop from one zygote) have infrequent genetic differences due to mutations occurring during development and gene

copy-number variation

Copy number variation (CNV) is a phenomenon in which sections of the genome are repeated and the number of repeats in the genome varies between individuals. Copy number variation is a type of structural variation: specifically, it is a type of ...

. Differences between individuals, even closely related individuals, are the key to techniques such as

genetic fingerprinting

DNA profiling (also called DNA fingerprinting and genetic fingerprinting) is the process of determining an individual's deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) characteristics. DNA analysis intended to identify a species, rather than an individual, is cal ...

.

The human genome has a total length of approximately 3.2 billion

base pair

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA ...

s (bp) in 46 chromosomes of DNA as well as slightly under 17,000 bp DNA in cellular

mitochondria

A mitochondrion () is an organelle found in the cells of most eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is us ...

. In 2015, the typical difference between an individual's genome and the reference genome was estimated at 20 million base pairs (or 0.6% of the total).

As of 2017, there were a total of 324 million known variants from sequenced

human genome

The human genome is a complete set of nucleic acid sequences for humans, encoded as the DNA within each of the 23 distinct chromosomes in the cell nucleus. A small DNA molecule is found within individual Mitochondrial DNA, mitochondria. These ar ...

s.

[

Comparatively speaking, humans are a genetically homogeneous species. Although a small number of genetic variants are found more frequently in certain geographic regions or in people with ancestry from those regions, this variation accounts for a small portion (~15%) of human genome variability. The majority of variation exists within the members of each human population. For comparison, ]rhesus macaque

The rhesus macaque (''Macaca mulatta''), colloquially rhesus monkey, is a species of Old World monkey. There are between six and nine recognised subspecies split between two groups, the Chinese-derived and the Indian-derived. Generally brown or g ...

s exhibit 2.5-fold greater DNA sequence diversity compared to humans. These rates differ depending on what macromolecules are being analyzed. Chimpanzees have more genetic variance than humans when examining nuclear DNA, but humans have more genetic variance when examining at the level of proteins.

The lack of discontinuities in genetic distances between human populations, absence of discrete branches in the human species, and striking homogeneity of human beings globally, imply that there is no scientific basis for inferring races or subspecies in humans, and for most traits

Trait may refer to:

* Phenotypic trait in biology, which involve genes and characteristics of organisms

* Genotypic trait, sometimes but not always presenting as a phenotypic trait

* Personality, traits that predict an individual's behavior.

** ...

, there is much more variation ''within'' populations than between them.[

Despite this, modern genetic studies have found substantial average genetic differences across human populations in traits such as skin colour, bodily dimensions, lactose and starch digestion, high altitude adaptions, drug response, taste receptors, and predisposition to developing particular diseases.]Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

,Out of Africa

''Out of Africa'' is a memoir by the Danish people, Danish author Karen Blixen. The book, first published in 1937, recounts events of the eighteen years when Blixen made her home in Kenya, then called East Africa Protectorate, British East Africa ...

theory of human origins.sickle-cell anemia

Sickle cell disease (SCD), also simply called sickle cell, is a group of inherited haemoglobin-related blood disorders. The most common type is known as sickle cell anemia. Sickle cell anemia results in an abnormality in the oxygen-carrying ...

is more often found in people with ancestry from certain sub-Saharan African, south European, Arabian, and Indian populations, due to the evolutionary pressure from mosquitos carrying malaria in these regions.

New findings show that each human has on average 60 new mutations compared to their parents.

Causes of variation

Causes of differences between individuals include independent assortment

Mendelian inheritance (also known as Mendelism) is a type of biological inheritance following the principles originally proposed by Gregor Mendel in 1865 and 1866, re-discovered in 1900 by Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns, and later popularized ...

, the exchange of genes (crossing over and recombination) during reproduction (through meiosis

Meiosis () is a special type of cell division of germ cells in sexually-reproducing organisms that produces the gametes, the sperm or egg cells. It involves two rounds of division that ultimately result in four cells, each with only one c ...

) and various mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, ...

al events.

There are at least three reasons why genetic variation exists between populations. Natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

may confer an adaptive advantage to individuals in a specific environment if an allele provides a competitive advantage. Alleles under selection are likely to occur only in those geographic regions where they confer an advantage. A second important process is genetic drift

Genetic drift, also known as random genetic drift, allelic drift or the Wright effect, is the change in the Allele frequency, frequency of an existing gene variant (allele) in a population due to random chance.

Genetic drift may cause gene va ...

, which is the effect of random changes in the gene pool, under conditions where most mutations are neutral (that is, they do not appear to have any positive or negative selective effect on the organism). Finally, small migrant populations have statistical differences – called the founder effect

In population genetics, the founder effect is the loss of genetic variation that occurs when a new population is established by a very small number of individuals from a larger population. It was first fully outlined by Ernst Mayr in 1942, us ...

– from the overall populations where they originated; when these migrants settle new areas, their descendant population typically differs from their population of origin: different genes predominate and it is less genetically diverse.

In humans, the main cause is genetic drift

Genetic drift, also known as random genetic drift, allelic drift or the Wright effect, is the change in the Allele frequency, frequency of an existing gene variant (allele) in a population due to random chance.

Genetic drift may cause gene va ...

. Serial founder effect

In population genetics, the founder effect is the loss of genetic variation that occurs when a new population is established by a very small number of individuals from a larger population. It was first fully outlined by Ernst Mayr in 1942, us ...

s and past small population size (increasing the likelihood of genetic drift) may have had an important influence in neutral differences between populations. The second main cause of genetic variation is due to the high degree of neutrality of most mutations. A small, but significant number of genes appear to have undergone recent natural selection, and these selective pressures are sometimes specific to one region.

Measures of variation

Genetic variation among humans occurs on many scales, from gross alterations in the human karyotype

A karyotype is the general appearance of the complete set of chromosomes in the cells of a species or in an individual organism, mainly including their sizes, numbers, and shapes. Karyotyping is the process by which a karyotype is discerned by de ...

to single nucleotide

Nucleotides are Organic compound, organic molecules composed of a nitrogenous base, a pentose sugar and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both o ...

changes. Chromosome abnormalities

A chromosomal abnormality, chromosomal anomaly, chromosomal aberration, chromosomal mutation, or chromosomal disorder is a missing, extra, or irregular portion of chromosomal DNA. These can occur in the form of numerical abnormalities, where ther ...

are detected in 1 of 160 live human births. Apart from sex chromosome disorders, most cases of aneuploidy result in death of the developing fetus (miscarriage

Miscarriage, also known in medical terms as a spontaneous abortion, is an end to pregnancy resulting in the loss and expulsion of an embryo or fetus from the womb before it can fetal viability, survive independently. Miscarriage before 6 weeks ...

); the most common extra autosomal

An autosome is any chromosome that is not a sex chromosome. The members of an autosome pair in a diploid cell have the same morphology, unlike those in allosomal (sex chromosome) pairs, which may have different structures. The DNA in autosome ...

chromosomes among live births are 21, 18 and 13.

Nucleotide diversity Nucleotide diversity is a concept in molecular genetics which is used to measure the degree of polymorphism (biology), polymorphism within a population.

One commonly used measure of nucleotide diversity was first introduced by Masatoshi Nei, Nei a ...

is the average proportion of nucleotides that differ between two individuals. As of 2004, the human nucleotide diversity was estimated to be 0.1%base pair

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA ...

s.1000 Genomes Project

The 1000 Genomes Project (1KGP), taken place from January 2008 to 2015, was an international research effort to establish the most detailed catalogue of human genetic variation at the time. Scientists planned to sequence the genomes of at least o ...

, which sequenced one thousand individuals from 26 human populations, found that "a typical ndividualgenome differs from the reference human genome at 4.1 million to 5.0 million sites … affecting 20 million bases of sequence"; the latter figure corresponds to 0.6% of total number of base pairs.indel

Indel (insertion-deletion) is a molecular biology term for an insertion or deletion of bases in the genome of an organism. Indels ≥ 50 bases in length are classified as structural variants.

In coding regions of the genome, unless the lengt ...

s) in the genetic sequence, but structural variations account for a greater number of base-pairs than the SNPs and indels.dbSNP

The Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database (dbSNP) is a free public archive for genetic variation within and across different species developed and hosted by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) in collaboration with the Natio ...

), which lists SNP and other variants, listed 324 million variants found in sequenced human genomes.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

A single nucleotide polymorphism

In genetics and bioinformatics, a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP ; plural SNPs ) is a germline substitution of a single nucleotide at a specific position in the genome. Although certain definitions require the substitution to be present in ...

(SNP) is a difference in a single nucleotide between members of one species that occurs in at least 1% of the population. The 2,504 individuals characterized by the 1000 Genomes Project

The 1000 Genomes Project (1KGP), taken place from January 2008 to 2015, was an international research effort to establish the most detailed catalogue of human genetic variation at the time. Scientists planned to sequence the genomes of at least o ...

had 84.7 million SNPs among them.messenger RNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is created during the ...

, and so causes a phenotypic

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology (physical form and structure), its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological propert ...

difference between members of the species. About 3% to 5% of human SNPs are functional (see International HapMap Project

The International HapMap Project was an organization that aimed to develop a haplotype map (HapMap) of the human genome, to describe the common patterns of human genetic variation. HapMap is used to find genetic variants affecting health, disease ...

). Neutral, or synonymous SNPs are still useful as genetic markers in genome-wide association studies

In genomics, a genome-wide association study (GWA study, or GWAS), is an observational study of a genome-wide set of genetic variants in different individuals to see if any variant is associated with a trait. GWA studies typically focus on assoc ...

, because of their sheer number and the stable inheritance over generations.stop codon

In molecular biology, a stop codon (or termination codon) is a codon (nucleotide triplet within messenger RNA) that signals the termination of the translation process of the current protein. Most codons in messenger RNA correspond to the additio ...

s in 103 genes. This corresponds to 0.5% of coding SNPs. They occur due to segmental duplication in the genome. These SNPs result in loss of protein, yet all these SNP alleles are common and are not purified in negative selection.

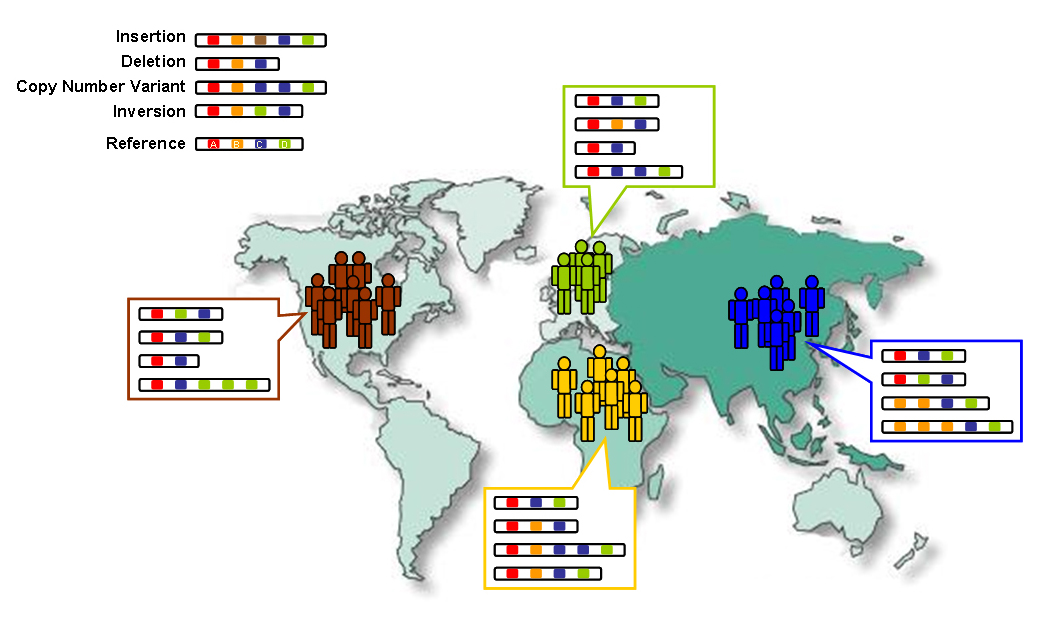

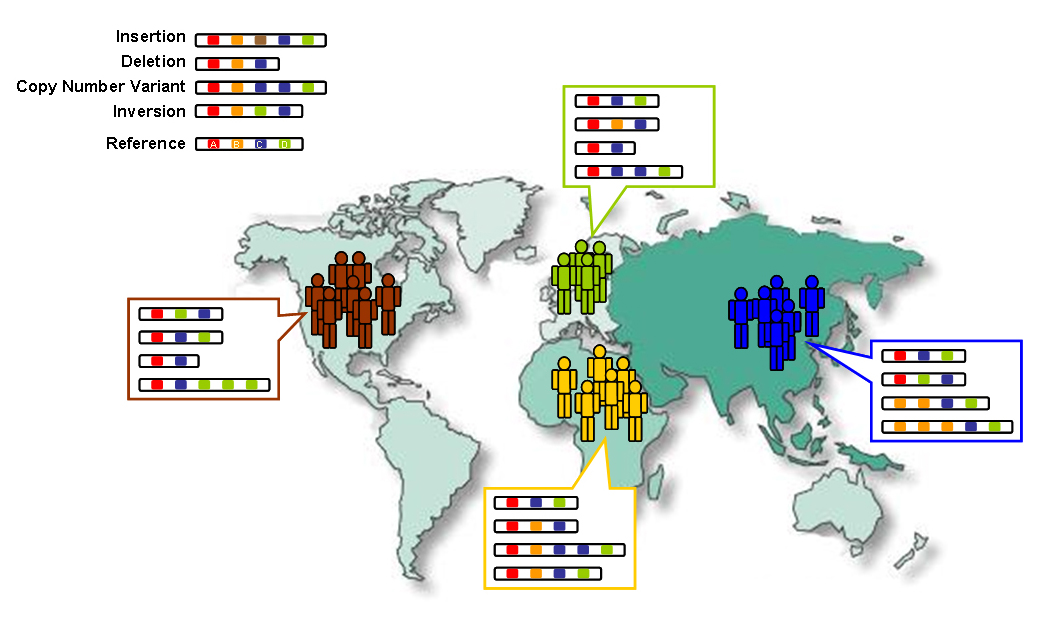

Structural variation

Structural variation Genomic structural variation is the variation in structure of an organism's chromosome, such as deletions, duplications, copy-number variants, insertions, inversions and translocations. Originally, a structure variation affects a sequence length a ...

is the variation in structure of an organism's chromosome

A chromosome is a package of DNA containing part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes, the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with nucleosome-forming packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells, the most import ...

. Structural variations, such as copy-number variation and deletions, inversions, insertions and duplications, account for much more human genetic variation than single nucleotide diversity. This was concluded in 2007 from analysis of the diploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Here ''sets of chromosomes'' refers to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, ...

full sequences of the genomes of two humans: Craig Venter

John Craig Venter (born October 14, 1946) is an American scientist. He is known for leading one of the first draft sequences of the human genome and led the first team to transfect a cell with a synthetic chromosome. Venter founded Celera Geno ...

and James D. Watson

James Dewey Watson (born April 6, 1928) is an American molecular biologist, geneticist, and zoologist. In 1953, he co-authored with Francis Crick the academic paper in ''Nature'' proposing the double helix structure of the DNA molecule. Wats ...

. This added to the two haploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell (biology), cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for Autosome, autosomal and Pseudoautosomal region, pseudoautosomal genes. Here ''sets of chromosomes'' refers to the num ...

sequences which were amalgamations of sequences from many individuals, published by the Human Genome Project

The Human Genome Project (HGP) was an international scientific research project with the goal of determining the base pairs that make up human DNA, and of identifying, mapping and sequencing all of the genes of the human genome from both a ...

and Celera Genomics

Celera Corporation is a subsidiary of Quest Diagnostics which focuses on genetic sequencing and related technologies. It was founded in 1998 as a business unit of Applera, spun off into an independent company in 2008, and finally acquired by Que ...

respectively.

According to the 1000 Genomes Project, a typical human has 2,100 to 2,500 structural variations, which include approximately 1,000 large deletions, 160 copy-number variants, 915 Alu insertions, 128 L1 insertions, 51 SVA insertions, 4 NUMTs, and 10 inversions.

Copy number variation

A copy-number variation (CNV) is a difference in the genome due to deleting or duplicating large regions of DNA on some chromosome. It is estimated that 0.4% of the genomes of unrelated humans differ with respect to copy number. When copy number variation is included, human-to-human genetic variation is estimated to be at least 0.5% (99.5% similarity). Copy number variations are inherited but can also arise during development.

A visual map with the regions with high genomic variation of the modern-human reference assembly relatively to a

Neanderthal of 50k

Epigenetics

Epigenetic

In biology, epigenetics is the study of changes in gene expression that happen without changes to the DNA sequence. The Greek prefix ''epi-'' (ἐπι- "over, outside of, around") in ''epigenetics'' implies features that are "on top of" or "in ...

variation is variation in the chemical tags that attach to DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

and affect how genes get read. The tags, "called epigenetic markings, act as switches that control how genes can be read." At some alleles, the epigenetic state of the DNA, and associated phenotype, can be inherited across generations of individuals.

Genetic variability

Genetic variability is a measure of the tendency of individual genotype

The genotype of an organism is its complete set of genetic material. Genotype can also be used to refer to the alleles or variants an individual carries in a particular gene or genetic location. The number of alleles an individual can have in a ...

s in a population to vary (become different) from one another. Variability is different from genetic diversity

Genetic diversity is the total number of genetic characteristics in the genetic makeup of a species. It ranges widely, from the number of species to differences within species, and can be correlated to the span of survival for a species. It is d ...

, which is the amount of variation seen in a particular population. The variability of a trait is how much that trait tends to vary in response to environmental and genetic influences.

Clines

In biology

Biology is the scientific study of life and living organisms. It is a broad natural science that encompasses a wide range of fields and unifying principles that explain the structure, function, growth, History of life, origin, evolution, and ...

, a cline is a continuum of species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

, populations, varieties, or forms of organisms that exhibit gradual phenotypic and/or genetic differences over a geographical area, typically as a result of environmental heterogeneity. In the scientific study of human genetic variation, a gene cline can be rigorously defined and subjected to quantitative metrics.

Haplogroups

In the study of molecular evolution

Molecular evolution describes how Heredity, inherited DNA and/or RNA change over evolutionary time, and the consequences of this for proteins and other components of Cell (biology), cells and organisms. Molecular evolution is the basis of phylogen ...

, a haplogroup is a group of similar haplotype

A haplotype (haploid genotype) is a group of alleles in an organism that are inherited together from a single parent.

Many organisms contain genetic material (DNA) which is inherited from two parents. Normally these organisms have their DNA orga ...

s that share a common ancestor

Common descent is a concept in evolutionary biology applicable when one species is the ancestor of two or more species later in time. According to modern evolutionary biology, all living beings could be descendants of a unique ancestor commonl ...

with a single nucleotide polymorphism

In genetics and bioinformatics, a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP ; plural SNPs ) is a germline substitution of a single nucleotide at a specific position in the genome. Although certain definitions require the substitution to be present in ...

(SNP) mutation. The study of haplogroups provides information about ancestral origins dating back thousands of years.

The most commonly studied human haplogroups are Y-chromosome (Y-DNA) haplogroups and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroups, both of which can be used to define genetic populations. Y-DNA is passed solely along the patrilineal

Patrilineality, also known as the male line, the spear side or agnatic kinship, is a common kinship system in which an individual's family membership derives from and is recorded through their father's lineage. It generally involves the inheritanc ...

line, from father to son, while mtDNA is passed down the matrilineal

Matrilineality, at times called matriliny, is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which people identify with their matriline, their mother's lineage, and which can involve the inheritan ...

line, from mother to both daughter or son. The Y-DNA and mtDNA may change by chance mutation at each generation.

Variable number tandem repeats

A variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) is the variation of length of a tandem repeat

In genetics, tandem repeats occur in DNA when a pattern of one or more nucleotides is repeated and the repetitions are directly adjacent to each other, e.g. ATTCG ATTCG ATTCG, in which the sequence ATTCG is repeated three times.

Several protein ...

. A tandem repeat is the adjacent repetition of a short nucleotide sequence

A nucleic acid sequence is a succession of bases within the nucleotides forming alleles within a DNA (using GACT) or RNA (GACU) molecule. This succession is denoted by a series of a set of five different letters that indicate the order of the nu ...

. Tandem repeats exist on many chromosomes

A chromosome is a package of DNA containing part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes, the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with nucleosome-forming packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells, the most importa ...

, and their length varies between individuals. Each variant acts as an inherited allele

An allele is a variant of the sequence of nucleotides at a particular location, or Locus (genetics), locus, on a DNA molecule.

Alleles can differ at a single position through Single-nucleotide polymorphism, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP), ...

, so they are used for personal or parental identification. Their analysis is useful in genetics and biology research, forensics

Forensic science combines principles of law and science to investigate criminal activity. Through crime scene investigations and laboratory analysis, forensic scientists are able to link suspects to evidence. An example is determining the time and ...

, and DNA fingerprinting

DNA profiling (also called DNA fingerprinting and genetic fingerprinting) is the process of determining an individual's deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) characteristics. DNA analysis intended to identify a species, rather than an individual, is cal ...

.

Short tandem repeats (about 5 base pairs) are called microsatellites

A microsatellite is a tract of repetitive DNA in which certain DNA motifs (ranging in length from one to six or more base pairs) are repeated, typically 5–50 times. Microsatellites occur at thousands of locations within an organism's genome. T ...

, while longer ones are called minisatellite

In genetics, a minisatellite is a tract of repetitive DNA in which certain DNA motifs (ranging in length from 10–60 base pairs) are typically repeated two to several hundred times. Minisatellites occur at more than 1,000 locations in the huma ...

s.

History and geographic distribution

Recent African origin of modern humans

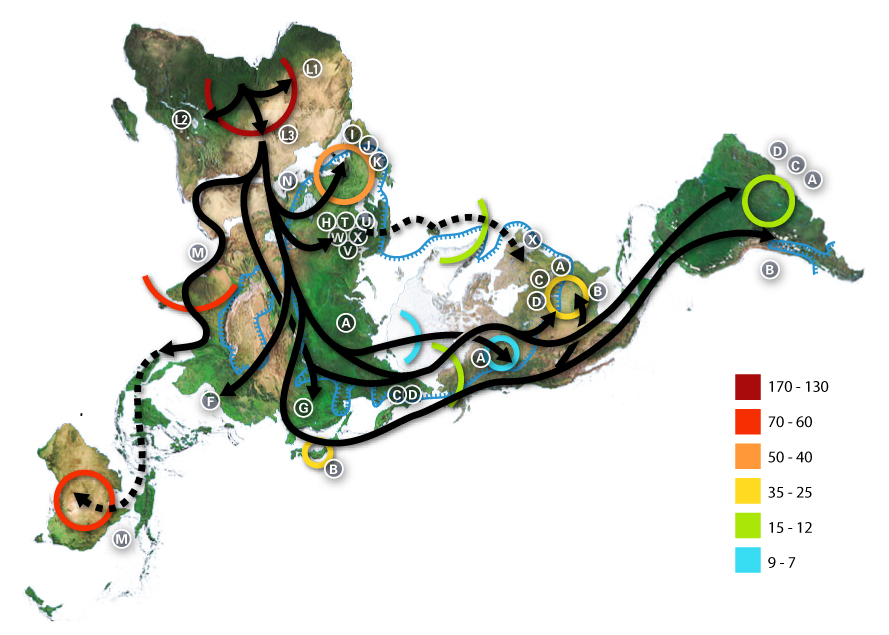

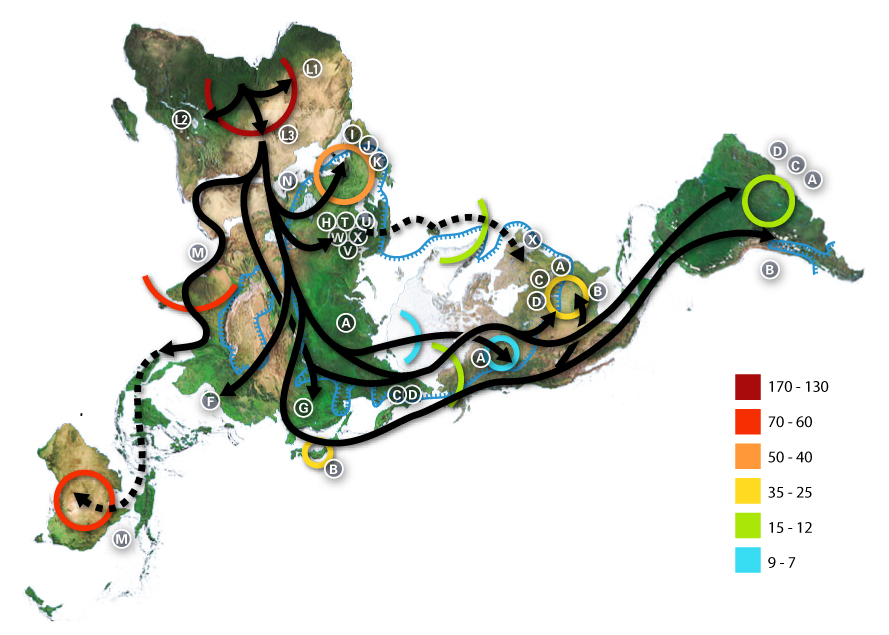

The recent African origin of modern humans

The recent African origin of modern humans or the "Out of Africa" theory (OOA) is the most widely accepted paleoanthropology, paleo-anthropological model of the geographic origin and Early human migrations, early migration of early modern h ...

paradigm assumes the dispersal of non-African populations of anatomically modern humans

Early modern human (EMH), or anatomically modern human (AMH), are terms used to distinguish ''Homo sapiens'' ( sometimes ''Homo sapiens sapiens'') that are anatomically consistent with the range of phenotypes seen in contemporary humans, from ...

after 70,000 years ago. Dispersal within Africa occurred significantly earlier, at least 130,000 years ago. The "out of Africa" theory originates in the 19th century, as a tentative suggestion in Charles Darwin's ''Descent of Man

''The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex'' is a book by English naturalist Charles Darwin, first published in 1871, which applies evolutionary theory to human evolution, and details his theory of sexual selection, a form of biolog ...

'', but remained speculative until the 1980s when it was supported by the study of present-day mitochondrial DNA, combined with evidence from physical anthropology

Biological anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, is a natural science discipline concerned with the biological and behavioral aspects of human beings, their extinct hominin ancestors, and related non-human primates, particularly from ...

of archaic specimens.

According to a 2000 study of Y-chromosome sequence variation,Khoisan

Khoisan ( ) or () is an Hypernymy and hyponymy, umbrella term for the various Indigenous peoples of Africa, indigenous peoples of Southern Africa who traditionally speak non-Bantu languages, combining the Khoekhoen and the San people, Sān peo ...

are the descendants of the most ancestral patrilineages of anatomically modern humans that left Africa 35,000 to 89,000 years ago.whole genome sequencing

Whole genome sequencing (WGS), also known as full genome sequencing or just genome sequencing, is the process of determining the entirety of the DNA sequence of an organism's genome at a single time. This entails sequencing all of an organism's ...

study of the world's populations observed similar clusters among the populations in Africa. At K=9, distinct ancestral components defined the Afroasiatic-speaking populations inhabiting North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

and Northeast Africa

Northeast Africa, or Northeastern Africa, or Northern East Africa as it was known in the past, encompasses the countries of Africa situated in and around the Red Sea. The region is intermediate between North Africa and East Africa, and encompasses ...

; the Nilo-Saharan

The Nilo-Saharan languages are a proposed family of around 210 African languages spoken by somewhere around 70 million speakers, mainly in the upper parts of the Chari and Nile rivers, including historic Nubia, north of where the two tributari ...

-speaking populations in Northeast Africa and East Africa

East Africa, also known as Eastern Africa or the East of Africa, is a region at the eastern edge of the Africa, African continent, distinguished by its unique geographical, historical, and cultural landscape. Defined in varying scopes, the regi ...

; the Ari populations in Northeast Africa; the Niger-Congo-speaking populations in West-Central Africa, West Africa

West Africa, also known as Western Africa, is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations geoscheme for Africa#Western Africa, United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Gha ...

, East Africa and Southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost region of Africa. No definition is agreed upon, but some groupings include the United Nations geoscheme for Africa, United Nations geoscheme, the intergovernmental Southern African Development Community, and ...

; the Pygmy

In anthropology, pygmy peoples are ethnic groups whose average height is unusually short. The term pygmyism is used to describe the phenotype of endemic short stature (as opposed to disproportionate dwarfism occurring in isolated cases in a po ...

populations in Central Africa

Central Africa (French language, French: ''Afrique centrale''; Spanish language, Spanish: ''África central''; Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''África Central'') is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries accordin ...

; and the Khoisan

Khoisan ( ) or () is an Hypernymy and hyponymy, umbrella term for the various Indigenous peoples of Africa, indigenous peoples of Southern Africa who traditionally speak non-Bantu languages, combining the Khoekhoen and the San people, Sān peo ...

populations in Southern Africa.

In May 2023, scientists reported, based on genetic studies, a more complicated pathway of human evolution than previously understood. According to the studies, humans evolved from different places and times in Africa, instead of from a single location and period of time.

Population genetics

Because of the common ancestry of all humans, only a small number of variants have large differences in frequency between populations. However, some rare variants in the world's human population are much more frequent in at least one population (more than 5%).

It is commonly assumed that early humans left Africa, and thus must have passed through a population bottleneck before their African-Eurasian divergence around 100,000 years ago (ca. 3,000 generations). The rapid expansion of a previously small population has two important effects on the distribution of genetic variation. First, the so-called

It is commonly assumed that early humans left Africa, and thus must have passed through a population bottleneck before their African-Eurasian divergence around 100,000 years ago (ca. 3,000 generations). The rapid expansion of a previously small population has two important effects on the distribution of genetic variation. First, the so-called founder effect

In population genetics, the founder effect is the loss of genetic variation that occurs when a new population is established by a very small number of individuals from a larger population. It was first fully outlined by Ernst Mayr in 1942, us ...

occurs when founder populations bring only a subset of the genetic variation from their ancestral population. Second, as founders become more geographically separated, the probability that two individuals from different founder populations will mate becomes smaller. The effect of this assortative mating is to reduce gene flow between geographical groups and to increase the genetic distance between groups.

The expansion of humans from Africa affected the distribution of genetic variation in two other ways. First, smaller (founder) populations experience greater genetic drift

Genetic drift, also known as random genetic drift, allelic drift or the Wright effect, is the change in the Allele frequency, frequency of an existing gene variant (allele) in a population due to random chance.

Genetic drift may cause gene va ...

because of increased fluctuations in neutral polymorphisms. Second, new polymorphisms that arose in one group were less likely to be transmitted to other groups as gene flow was restricted.

Populations in Africa tend to have lower amounts of linkage disequilibrium Linkage disequilibrium, often abbreviated to LD, is a term in population genetics referring to the association of genes, usually linked genes, in a population. It has become an important tool in medical genetics and other fields

In defining LD, it ...

than do populations outside Africa, partly because of the larger size of human populations in Africa over the course of human history and partly because the number of modern humans who left Africa to colonize the rest of the world appears to have been relatively low.

Distribution of variation

The distribution of genetic variants within and among human populations are impossible to describe succinctly because of the difficulty of defining a "population," the clinal nature of variation, and heterogeneity across the genome (Long and Kittles 2003). In general, however, an average of 85% of genetic variation exists within local populations, ~7% is between local populations within the same continent, and ~8% of variation occurs between large groups living on different continents.

The distribution of genetic variants within and among human populations are impossible to describe succinctly because of the difficulty of defining a "population," the clinal nature of variation, and heterogeneity across the genome (Long and Kittles 2003). In general, however, an average of 85% of genetic variation exists within local populations, ~7% is between local populations within the same continent, and ~8% of variation occurs between large groups living on different continents.recent African origin

The recent African origin of modern humans or the "Out of Africa" theory (OOA) is the most widely accepted paleo-anthropological model of the geographic origin and early migration of anatomically modern humans (''Homo sapiens''). It follo ...

theory for humans would predict that in Africa there exists a great deal more diversity than elsewhere and that diversity should decrease the further from Africa a population is sampled.

Phenotypic variation

Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lie south of the Sahara. These include Central Africa, East Africa, Southern Africa, and West Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the list of sovereign states and ...

has the most human genetic diversity and the same has been shown to hold true for phenotypic variation in skull form.gene expression

Gene expression is the process (including its Regulation of gene expression, regulation) by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, proteins or non-coding RNA, ...

. Genetic diversity decreases smoothly with migratory distance from that region, which many scientists believe to be the origin of modern humans, and that decrease is mirrored by a decrease in phenotypic variation. Skull measurements are an example of a physical attribute whose within-population variation decreases with distance from Africa.

The distribution of many physical traits resembles the distribution of genetic variation within and between human populations (American Association of Physical Anthropologists

The American Association of Biological Anthropologists (AABA) is an international group based in the United States which affirms itself as a professional society of biological anthropologists. The organization sponsors two peer-reviewed science ...

1996; Keita and Kittles 1997). For example, ~90% of the variation in human head shapes occurs within continental groups, and ~10% separates groups, with a greater variability of head shape among individuals with recent African ancestors (Relethford 2002).

A prominent exception to the common distribution of physical characteristics within and among groups is skin color

Human skin color ranges from the darkest brown to the lightest hues. Differences in skin color among individuals is caused by variation in pigmentation, which is largely the result of genetics (inherited from one's biological parents), and in ...

. Approximately 10% of the variance in skin color occurs within groups, and ~90% occurs between groups (Relethford 2002). This distribution of skin color and its geographic patterning – with people whose ancestors lived predominantly near the equator having darker skin than those with ancestors who lived predominantly in higher latitudes – indicate that this attribute has been under strong selective pressure. Darker skin appears to be strongly selected for in equatorial regions to prevent sunburn, skin cancer, the photolysis

Photodissociation, photolysis, photodecomposition, or photofragmentation is a chemical reaction in which molecules of a chemical compound are broken down by absorption of light or photons. It is defined as the interaction of one or more photons wi ...

of folate

Folate, also known as vitamin B9 and folacin, is one of the B vitamins. Manufactured folic acid, which is converted into folate by the body, is used as a dietary supplement and in food fortification as it is more stable during processing and ...

, and damage to sweat glands.

Understanding how genetic diversity in the human population impacts various levels of gene expression is an active area of research. While earlier studies focused on the relationship between DNA variation and RNA expression, more recent efforts are characterizing the genetic control of various aspects of gene expression including chromatin states, translation, and protein levels. A study published in 2007 found that 25% of genes showed different levels of gene expression between populations of European and Asian descent. The primary cause of this difference in gene expression was thought to be SNPs in gene regulatory regions of DNA. Another study published in 2007 found that approximately 83% of genes were expressed at different levels among individuals and about 17% between populations of European and African descent.

= Wright's fixation index as measure of variation

=

The population geneticist Sewall Wright

Sewall Green Wright ForMemRS

HonFRSE (December 21, 1889March 3, 1988) was an American geneticist known for his influential work on evolutionary theory and also for his work on path analysis. He was a founder of population genetics alongside ...

developed the fixation index

The fixation index (FST) is a measure of population differentiation due to genetic structure. It is frequently estimated from Polymorphism (biology), genetic polymorphism data, such as single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) or Microsatellite (genet ...

(often abbreviated to ''F''ST) as a way of measuring genetic differences between populations. This statistic is often used in taxonomy to compare differences between any two given populations by measuring the genetic differences among and between populations for individual genes, or for many genes simultaneously.Richard Lewontin

Richard Charles Lewontin (March 29, 1929 – July 4, 2021) was an American evolutionary biologist, mathematician, geneticist, and social commentator. A leader in developing the mathematical basis of population genetics and evolutionary theory, ...

, who affirmed these ratios, thus concluded neither "race" nor "subspecies" were appropriate or useful ways to describe human populations.[*

]

Jeffrey Long and Rick Kittles give a long critique of the application of ''F''ST to human populations in their 2003 paper "Human Genetic Diversity and the Nonexistence of Biological Races". They find that the figure of 85% is misleading because it implies that all human populations contain on average 85% of all genetic diversity. They argue the underlying statistical model incorrectly assumes equal and independent histories of variation for each large human population. A more realistic approach is to understand that some human groups are parental to other groups and that these groups represent paraphyletic

Paraphyly is a taxonomic term describing a grouping that consists of the grouping's last common ancestor and some but not all of its descendant lineages. The grouping is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In co ...

groups to their descent groups. For example, under the recent African origin

The recent African origin of modern humans or the "Out of Africa" theory (OOA) is the most widely accepted paleo-anthropological model of the geographic origin and early migration of anatomically modern humans (''Homo sapiens''). It follo ...

theory the human population in Africa is paraphyletic to all other human groups because it represents the ancestral group from which all non-African populations derive, but more than that, non-African groups only derive from a small non-representative sample of this African population. This means that all non-African groups are more closely related to each other and to some African groups (probably east Africans) than they are to others, and further that the migration out of Africa represented a genetic bottleneck

A population bottleneck or genetic bottleneck is a sharp reduction in the size of a population due to environmental events such as famines, earthquakes, floods, fires, disease, and droughts; or human activities such as genocide, speciocide, wid ...

, with much of the diversity that existed in Africa not being carried out of Africa by the emigrating groups. Under this scenario, human populations do not have equal amounts of local variability, but rather diminished amounts of diversity the further from Africa any population lives. Long and Kittles find that rather than 85% of human genetic diversity existing in all human populations, about 100% of human diversity exists in a single African population, whereas only about 70% of human genetic diversity exists in a population derived from New Guinea. Long and Kittles argued that this still produces a global human population that is genetically homogeneous compared to other mammalian populations.

Archaic admixture

Anatomically modern humans interbred with Neanderthals during the Middle Paleolithic

The Middle Paleolithic (or Middle Palaeolithic) is the second subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age as it is understood in Europe, Africa and Asia. The term Middle Stone Age is used as an equivalent or a synonym for the Middle P ...

. In May 2010, the Neanderthal Genome Project presented genetic evidence that interbreeding

In biology, a hybrid is the offspring resulting from combining the qualities of two organisms of different varieties, subspecies, species or genera through sexual reproduction. Generally, it means that each cell has genetic material from two di ...

took place and that a small but significant portion, around 2–4%, of Neanderthal admixture is present in the DNA of modern Eurasians and Oceanians, and nearly absent in sub-Saharan African populations.

Between 4% and 6% of the genome of Melanesians

Melanesians are the predominant and Indigenous peoples of Oceania, indigenous inhabitants of Melanesia, in an area stretching from New Guinea to the Fiji Islands. Most speak one of the many languages of the Austronesian languages, Austronesian l ...

(represented by the Papua New Guinean and Bougainville Islander) appears to derive from Denisovans – a previously unknown hominin which is more closely related to Neanderthals than to Sapiens. It was possibly introduced during the early migration of the ancestors of Melanesians into Southeast Asia. This history of interaction suggests that Denisovans once ranged widely over eastern Asia.[

]

Thus, Melanesians emerge as one of the most archaic-admixed populations, having Denisovan/Neanderthal-related admixture of ~8%.

Categorization of the world population

New data on human genetic variation has reignited the debate about a possible biological basis for categorization of humans into races. Most of the controversy surrounds the question of how to interpret the genetic data and whether conclusions based on it are sound. Some researchers argue that self-identified race can be used as an indicator of geographic ancestry for certain ancestry and health, health risks and medications.

Although the genetic differences among human groups are relatively small, these differences in certain genes such as Duffy antigen system, duffy, earwax, ABCC11, SLC24A5, called ancestry-informative markers (AIMs) nevertheless can be used to reliably situate many individuals within broad, geographically based groupings. For example, computer analyses of hundreds of polymorphic loci sampled in globally distributed populations have revealed the existence of genetic clustering that roughly is associated with groups that historically have occupied large continental and subcontinental regions (Rosenberg ''et al.'' 2002; Bamshad ''et al.'' 2003).

Some commentators have argued that these patterns of variation provide a biological justification for the use of traditional racial categories. They argue that the continental clusterings correspond roughly with the division of human beings into sub-Saharan Africans; Europeans, Western Asians, Central Asians, Southern Asians and Northern Africans; Eastern Asians, Southeast Asians, Polynesians and Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Native Americans; and other inhabitants of Oceania (Melanesians, Micronesians & Australian Aborigines) (Risch ''et al.'' 2002). Other observers disagree, saying that the same data undercut traditional notions of racial groups (King and Motulsky 2002; Calafell 2003; Tishkoff and Kidd 2004

New data on human genetic variation has reignited the debate about a possible biological basis for categorization of humans into races. Most of the controversy surrounds the question of how to interpret the genetic data and whether conclusions based on it are sound. Some researchers argue that self-identified race can be used as an indicator of geographic ancestry for certain ancestry and health, health risks and medications.

Although the genetic differences among human groups are relatively small, these differences in certain genes such as Duffy antigen system, duffy, earwax, ABCC11, SLC24A5, called ancestry-informative markers (AIMs) nevertheless can be used to reliably situate many individuals within broad, geographically based groupings. For example, computer analyses of hundreds of polymorphic loci sampled in globally distributed populations have revealed the existence of genetic clustering that roughly is associated with groups that historically have occupied large continental and subcontinental regions (Rosenberg ''et al.'' 2002; Bamshad ''et al.'' 2003).

Some commentators have argued that these patterns of variation provide a biological justification for the use of traditional racial categories. They argue that the continental clusterings correspond roughly with the division of human beings into sub-Saharan Africans; Europeans, Western Asians, Central Asians, Southern Asians and Northern Africans; Eastern Asians, Southeast Asians, Polynesians and Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Native Americans; and other inhabitants of Oceania (Melanesians, Micronesians & Australian Aborigines) (Risch ''et al.'' 2002). Other observers disagree, saying that the same data undercut traditional notions of racial groups (King and Motulsky 2002; Calafell 2003; Tishkoff and Kidd 2004[). They point out, for example, that major populations considered races or subgroups within races do not necessarily form their own clusters.

Racial categories are also undermined by findings that genetic variants which are limited to one region tend to be rare within that region, variants that are common within a region tend to be shared across the globe, and most differences between individuals, whether they come from the same region or different regions, are due to global variants.]

Genetic clustering

Genetic data can be used to infer population structure and assign individuals to groups that often correspond with their self-identified geographical ancestry. Jorde and Wooding (2004) argued that "Analysis of many loci now yields reasonably accurate estimates of genetic similarity among individuals, rather than populations. Clustering of individuals is correlated with geographic origin or ancestry."[ However, identification by geographic origin may quickly break down when considering historical ancestry shared between individuals back in time.

An analysis of ]autosomal

An autosome is any chromosome that is not a sex chromosome. The members of an autosome pair in a diploid cell have the same morphology, unlike those in allosomal (sex chromosome) pairs, which may have different structures. The DNA in autosome ...

Single-nucleotide polymorphism, SNP data from the International HapMap Project

The International HapMap Project was an organization that aimed to develop a haplotype map (HapMap) of the human genome, to describe the common patterns of human genetic variation. HapMap is used to find genetic variants affecting health, disease ...

(Phase II) and Center for the Study of Human Polymorphisms, CEPH Human Genome Diversity Panel samples was published in 2009.

The study of 53 populations taken from the HapMap and CEPH data (1138 unrelated individuals) suggested that natural selection may shape the human genome much more slowly than previously thought, with factors such as migration within and among continents more heavily influencing the distribution of genetic variations.[

See also: .

.]

A similar study published in 2010 found strong genome-wide evidence for selection due to changes in ecoregion, diet, and subsistence

particularly in connection with polar ecoregions, with foraging, and with a diet rich in roots and tubers.

Forensic anthropology

Forensic anthropologists can assess the ancestry of skeletal remains by analyzing skeletal morphology as well as using genetic and chemical markers, when possible. While these assessments are never certain, the accuracy of skeletal morphology analyses in determining true ancestry has been estimated at 90%.

Gene flow and admixture

Gene flow between two populations reduces the average genetic distance between the populations, only totally isolated human populations experience no gene flow and most populations have continuous gene flow with other neighboring populations which create the clinal distribution observed for most genetic variation. When gene flow takes place between well-differentiated genetic populations the result is referred to as "genetic admixture".

Admixture mapping is a technique used to study how genetic variants cause differences in disease rates between population.

Impact on gene function and health

Given that each individual has millions of genetic variants (compared to the reference genome), it is an important question what impact these variants have on human health or gene function. Most genetic variants have only small to moderate effects, if any. Frequently cited examples include hypertension (Douglas ''et al.'' 1996), diabetes, obesity (Fernandez ''et al.'' 2003), and prostate cancer (Platz ''et al.'' 2000). However, the role of genetic factors in generating these differences remains uncertain.

Effect on protein function

The human genome

The human genome is a complete set of nucleic acid sequences for humans, encoded as the DNA within each of the 23 distinct chromosomes in the cell nucleus. A small DNA molecule is found within individual Mitochondrial DNA, mitochondria. These ar ...

encodes about 20,000 protein-coding genes with about 550 amino acids each. Hence, human proteins span about 11 million amino acids (22 million per diploid genome). The median number of missense mutations in individual human genomes is about 8600, that is, two individuals differ by 1 in about 2600 amino acids or in about 20% of their proteins. The average individual has about 137 (predicted) loss of function mutations, including 71 Frameshift mutation, frameshift and 148 in-frame deletions or Insertion (genetics), insertions.

Monogenetic diseases

Differences in allele frequencies contribute to group differences in the incidence of some monogenic disorder, monogenic diseases, and they may contribute to differences in the incidence of some common diseases.

Beneficial variants

Some other variations on the other hand are beneficial to human, as they prevent certain diseases and increase the chance to adapt to the environment. For example, mutation in CCR5 gene that protects against AIDS. CCR5 gene is absent on the surface of cell due to mutation. Without CCR5 gene on the surface, there is nothing for HIV viruses to grab on and bind into. Therefore, the mutation on CCR5 gene decreases the chance of an individual's risk with AIDS. The mutation in CCR5 is also quite common in certain areas, with more than 14% of the population carry the mutation in Europe and about 6–10% in Asia and North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

.

Many genetic variants may have aided humans in ancient times but plague us today. For example, genes that allow humans to more efficiently process food also make people susceptible to obesity and diabetes today.

Many genetic variants may have aided humans in ancient times but plague us today. For example, genes that allow humans to more efficiently process food also make people susceptible to obesity and diabetes today.

Genome projects and organizations

Human genome projects are scientific endeavors that determine or study the structure of the human genome

The human genome is a complete set of nucleic acid sequences for humans, encoded as the DNA within each of the 23 distinct chromosomes in the cell nucleus. A small DNA molecule is found within individual Mitochondrial DNA, mitochondria. These ar ...

. The Human Genome Project

The Human Genome Project (HGP) was an international scientific research project with the goal of determining the base pairs that make up human DNA, and of identifying, mapping and sequencing all of the genes of the human genome from both a ...

was a landmark genome project.

There are numerous related projects that deal with genetic variation (or variation in the encoded proteins), e.g. organized by the following organizations:

* Human Genome Organisation, HUman Genome Organisation (HUGO) -- organizes activities around human genome sequencing, including variants

* Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS) -- develops nomenclatural standards for human genetic variants

* HGVS Variant Nomenclature Committee (HVNC) -- maps and organizes variant nomenclature

See also

* Archaeogenetics

* Chimera (genetics)

* Genealogical DNA test

* Human evolutionary genetics

* Isolation by distance

* Multiregional hypothesis

* Neurodiversity

* Race and genetics

* Recent single origin hypothesis

* Y-chromosome haplogroups in populations of the world

Regional

* 1000 Genomes Project

The 1000 Genomes Project (1KGP), taken place from January 2008 to 2015, was an international research effort to establish the most detailed catalogue of human genetic variation at the time. Scientists planned to sequence the genomes of at least o ...

* African admixture in Europe

* Genetic history of Europe

* Genetic history of indigenous peoples of the Americas

* Genetic history of South Asia

*Genetic history of the British Isles

Projects

* Human Variome Project

References

Further reading

*

*

*

*

reprint-zip

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

External links

Human Genome Variation Society

{{DEFAULTSORT:Human Genetic Variation

Human population genetics

Biological anthropology

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms, *

Human evolution, *

It is commonly assumed that early humans left Africa, and thus must have passed through a population bottleneck before their African-Eurasian divergence around 100,000 years ago (ca. 3,000 generations). The rapid expansion of a previously small population has two important effects on the distribution of genetic variation. First, the so-called

It is commonly assumed that early humans left Africa, and thus must have passed through a population bottleneck before their African-Eurasian divergence around 100,000 years ago (ca. 3,000 generations). The rapid expansion of a previously small population has two important effects on the distribution of genetic variation. First, the so-called  The distribution of genetic variants within and among human populations are impossible to describe succinctly because of the difficulty of defining a "population," the clinal nature of variation, and heterogeneity across the genome (Long and Kittles 2003). In general, however, an average of 85% of genetic variation exists within local populations, ~7% is between local populations within the same continent, and ~8% of variation occurs between large groups living on different continents. The

The distribution of genetic variants within and among human populations are impossible to describe succinctly because of the difficulty of defining a "population," the clinal nature of variation, and heterogeneity across the genome (Long and Kittles 2003). In general, however, an average of 85% of genetic variation exists within local populations, ~7% is between local populations within the same continent, and ~8% of variation occurs between large groups living on different continents. The  New data on human genetic variation has reignited the debate about a possible biological basis for categorization of humans into races. Most of the controversy surrounds the question of how to interpret the genetic data and whether conclusions based on it are sound. Some researchers argue that self-identified race can be used as an indicator of geographic ancestry for certain ancestry and health, health risks and medications.

Although the genetic differences among human groups are relatively small, these differences in certain genes such as Duffy antigen system, duffy, earwax, ABCC11, SLC24A5, called ancestry-informative markers (AIMs) nevertheless can be used to reliably situate many individuals within broad, geographically based groupings. For example, computer analyses of hundreds of polymorphic loci sampled in globally distributed populations have revealed the existence of genetic clustering that roughly is associated with groups that historically have occupied large continental and subcontinental regions (Rosenberg ''et al.'' 2002; Bamshad ''et al.'' 2003).

Some commentators have argued that these patterns of variation provide a biological justification for the use of traditional racial categories. They argue that the continental clusterings correspond roughly with the division of human beings into sub-Saharan Africans; Europeans, Western Asians, Central Asians, Southern Asians and Northern Africans; Eastern Asians, Southeast Asians, Polynesians and Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Native Americans; and other inhabitants of Oceania (Melanesians, Micronesians & Australian Aborigines) (Risch ''et al.'' 2002). Other observers disagree, saying that the same data undercut traditional notions of racial groups (King and Motulsky 2002; Calafell 2003; Tishkoff and Kidd 2004). They point out, for example, that major populations considered races or subgroups within races do not necessarily form their own clusters.

Racial categories are also undermined by findings that genetic variants which are limited to one region tend to be rare within that region, variants that are common within a region tend to be shared across the globe, and most differences between individuals, whether they come from the same region or different regions, are due to global variants. No genetic variants have been found which are Fixation (population genetics), fixed within a continent or major region and found nowhere else.

Furthermore, because human genetic variation is clinal, many individuals affiliate with two or more continental groups. Thus, the genetically based "biogeographical ancestry" assigned to any given person generally will be broadly distributed and will be accompanied by sizable uncertainties (Pfaff ''et al.'' 2004).

In many parts of the world, groups have mixed in such a way that many individuals have relatively recent ancestors from widely separated regions. Although genetic analyses of large numbers of loci can produce estimates of the percentage of a person's ancestors coming from various continental populations (Shriver ''et al.'' 2003; Bamshad ''et al.'' 2004), these estimates may assume a false distinctiveness of the parental populations, since human groups have exchanged mates from local to continental scales throughout history (Cavalli-Sforza ''et al.'' 1994; Hoerder 2002). Even with large numbers of markers, information for estimating admixture proportions of individuals or groups is limited, and estimates typically will have wide confidence intervals (Pfaff ''et al.'' 2004).

New data on human genetic variation has reignited the debate about a possible biological basis for categorization of humans into races. Most of the controversy surrounds the question of how to interpret the genetic data and whether conclusions based on it are sound. Some researchers argue that self-identified race can be used as an indicator of geographic ancestry for certain ancestry and health, health risks and medications.

Although the genetic differences among human groups are relatively small, these differences in certain genes such as Duffy antigen system, duffy, earwax, ABCC11, SLC24A5, called ancestry-informative markers (AIMs) nevertheless can be used to reliably situate many individuals within broad, geographically based groupings. For example, computer analyses of hundreds of polymorphic loci sampled in globally distributed populations have revealed the existence of genetic clustering that roughly is associated with groups that historically have occupied large continental and subcontinental regions (Rosenberg ''et al.'' 2002; Bamshad ''et al.'' 2003).

Some commentators have argued that these patterns of variation provide a biological justification for the use of traditional racial categories. They argue that the continental clusterings correspond roughly with the division of human beings into sub-Saharan Africans; Europeans, Western Asians, Central Asians, Southern Asians and Northern Africans; Eastern Asians, Southeast Asians, Polynesians and Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Native Americans; and other inhabitants of Oceania (Melanesians, Micronesians & Australian Aborigines) (Risch ''et al.'' 2002). Other observers disagree, saying that the same data undercut traditional notions of racial groups (King and Motulsky 2002; Calafell 2003; Tishkoff and Kidd 2004). They point out, for example, that major populations considered races or subgroups within races do not necessarily form their own clusters.

Racial categories are also undermined by findings that genetic variants which are limited to one region tend to be rare within that region, variants that are common within a region tend to be shared across the globe, and most differences between individuals, whether they come from the same region or different regions, are due to global variants. No genetic variants have been found which are Fixation (population genetics), fixed within a continent or major region and found nowhere else.

Furthermore, because human genetic variation is clinal, many individuals affiliate with two or more continental groups. Thus, the genetically based "biogeographical ancestry" assigned to any given person generally will be broadly distributed and will be accompanied by sizable uncertainties (Pfaff ''et al.'' 2004).

In many parts of the world, groups have mixed in such a way that many individuals have relatively recent ancestors from widely separated regions. Although genetic analyses of large numbers of loci can produce estimates of the percentage of a person's ancestors coming from various continental populations (Shriver ''et al.'' 2003; Bamshad ''et al.'' 2004), these estimates may assume a false distinctiveness of the parental populations, since human groups have exchanged mates from local to continental scales throughout history (Cavalli-Sforza ''et al.'' 1994; Hoerder 2002). Even with large numbers of markers, information for estimating admixture proportions of individuals or groups is limited, and estimates typically will have wide confidence intervals (Pfaff ''et al.'' 2004).

Many genetic variants may have aided humans in ancient times but plague us today. For example, genes that allow humans to more efficiently process food also make people susceptible to obesity and diabetes today.

Many genetic variants may have aided humans in ancient times but plague us today. For example, genes that allow humans to more efficiently process food also make people susceptible to obesity and diabetes today.