History Of Washington (state) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of Washington includes thousands of years of Native American history before Europeans arrived and began to establish territorial claims. The region was part of

The history of Washington includes thousands of years of Native American history before Europeans arrived and began to establish territorial claims. The region was part of

Captain Robert Gray (1755-1806) (for whom Grays Harbor County in Washington was named), a civilian

Captain Robert Gray (1755-1806) (for whom Grays Harbor County in Washington was named), a civilian  British / Canadian explorer, surveyor / cartographer and fur trader David Thompson (1770-1857), extensively explored the

British / Canadian explorer, surveyor / cartographer and fur trader David Thompson (1770-1857), extensively explored the

By the

By the

In 1848, the

In 1848, the  This event triggered the Cayuse War against the Natives, wherein the Provisional Legislature of Oregon in 1847 immediately raised companies of volunteers to go to war, if necessary, against the Cayuse, and, to the discontent of some of the militia leaders, also sent a peace commission. The

This event triggered the Cayuse War against the Natives, wherein the Provisional Legislature of Oregon in 1847 immediately raised companies of volunteers to go to war, if necessary, against the Cayuse, and, to the discontent of some of the militia leaders, also sent a peace commission. The

In 1856, Chief Leschi of the Nisqually was finally captured after one of the largest battles of the war. Stevens, who was seeking to punish Leschi for what he considered a troublesome revolt, had Leschi charged with the murder of a member of the Washingtonian militia. Leschi's argument in his defense was that he was not at the scene of the killing, but that even if he was the killing had been an act of war and was thus not murder. The initial trial ended in a hung jury after the judge told jurors that if they believed the killing of the militiaman was an act of war, they could not find Leschi guilty of murder. A second trial, without this note to the jury, ended in Leschi being convicted of murder and sentenced to execution. Interference by those who opposed the execution were able to stall it for months, but in the end they could not prevent it. Chief Leschi was formally exonerated of his crimes in 2014.

Concurrent with the Nisqually negotiations, tensions with other local tribes also continued to escalate. In one instance a group of Washingtonians assaulted and murdered a Yakama mother, her daughter, and her newborn infant. The woman's husband Mosheel, the son of the Yakama tribe's chieftain, gathered up a posse, tracked down the miners and killed them. The Bureau of Indian Affairs sent out an agent named Andrew Bolon to investigate, but before reaching the crime scene the chief of the Yakama intercepted him and warned Bolon that Mosheel was too dangerous to be taken in. Taking heed of this warning, Bolon decided to return to the Bureau to report his findings. He joined a traveling group of Yakama on his return trip, and while they walked he told them why he was in the area, about the unexplained murder that had happened. Unbeknownst to Bolon, the rest of the trip would be taken up by argument between the natives in a language he did not understand, as the leader of the group, Mosheel, argued for the murder of Bolon. Before he was stabbed in the throat, Bolon reportedly yelled in Chinook dialect, "I did not come to fight you!"

Washington Territory immediately mobilized for war, and sent the Territorial Militia to put down what it saw as a rebellion. The tribes - first the Yakama, eventually joined by the Walla Walla and the Cayuse - united together to fight the Americans in what is called the Yakima War. The U.S. Army sent troops and a number of raids and battles took place. In 1858, the Americans, at the

In 1856, Chief Leschi of the Nisqually was finally captured after one of the largest battles of the war. Stevens, who was seeking to punish Leschi for what he considered a troublesome revolt, had Leschi charged with the murder of a member of the Washingtonian militia. Leschi's argument in his defense was that he was not at the scene of the killing, but that even if he was the killing had been an act of war and was thus not murder. The initial trial ended in a hung jury after the judge told jurors that if they believed the killing of the militiaman was an act of war, they could not find Leschi guilty of murder. A second trial, without this note to the jury, ended in Leschi being convicted of murder and sentenced to execution. Interference by those who opposed the execution were able to stall it for months, but in the end they could not prevent it. Chief Leschi was formally exonerated of his crimes in 2014.

Concurrent with the Nisqually negotiations, tensions with other local tribes also continued to escalate. In one instance a group of Washingtonians assaulted and murdered a Yakama mother, her daughter, and her newborn infant. The woman's husband Mosheel, the son of the Yakama tribe's chieftain, gathered up a posse, tracked down the miners and killed them. The Bureau of Indian Affairs sent out an agent named Andrew Bolon to investigate, but before reaching the crime scene the chief of the Yakama intercepted him and warned Bolon that Mosheel was too dangerous to be taken in. Taking heed of this warning, Bolon decided to return to the Bureau to report his findings. He joined a traveling group of Yakama on his return trip, and while they walked he told them why he was in the area, about the unexplained murder that had happened. Unbeknownst to Bolon, the rest of the trip would be taken up by argument between the natives in a language he did not understand, as the leader of the group, Mosheel, argued for the murder of Bolon. Before he was stabbed in the throat, Bolon reportedly yelled in Chinook dialect, "I did not come to fight you!"

Washington Territory immediately mobilized for war, and sent the Territorial Militia to put down what it saw as a rebellion. The tribes - first the Yakama, eventually joined by the Walla Walla and the Cayuse - united together to fight the Americans in what is called the Yakima War. The U.S. Army sent troops and a number of raids and battles took place. In 1858, the Americans, at the

On December 28, 1861, during the ongoing ''Trent'' Affair,

On December 28, 1861, during the ongoing ''Trent'' Affair,

Due to increasing amounts of cheap Chinese labor replacing white labor throughout Washington, many of the growing progressive and

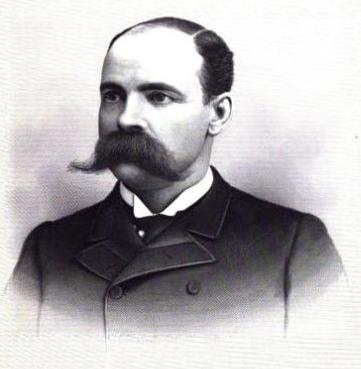

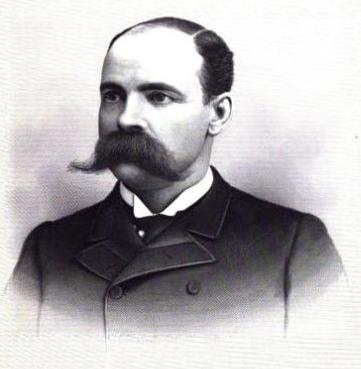

Due to increasing amounts of cheap Chinese labor replacing white labor throughout Washington, many of the growing progressive and  A militia called the Seattle's Rifles was quickly formed to deal with the rioters and protect the Chinese citizens who had been abducted from their homes and dragged out into the streets. This militia was led by future state governor and at that time current Seattle Sheriff

A militia called the Seattle's Rifles was quickly formed to deal with the rioters and protect the Chinese citizens who had been abducted from their homes and dragged out into the streets. This militia was led by future state governor and at that time current Seattle Sheriff

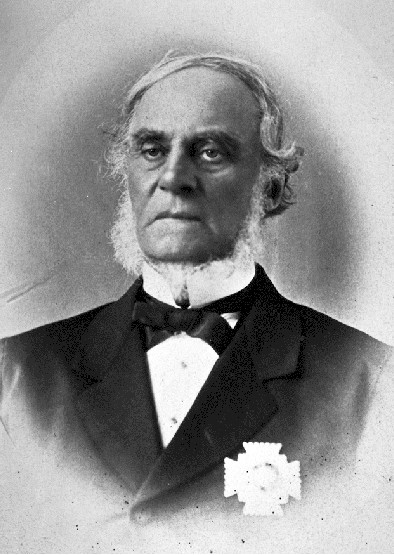

Narrowly winning election, Republican Elisha P Ferry, former Territorial Governor from almost a decade earlier and

Narrowly winning election, Republican Elisha P Ferry, former Territorial Governor from almost a decade earlier and  In 1890, while nationally Democrats won in a landslide, in Washington their gains were only meager, and they remained the minority. During the 1880s Washington had become more and more prosperous, but the Eastern agricultural areas did not share in the prosperity of the cities. In part this was caused by the highly monopolized nature of the new railroads. In addition, rising economic issues led to a crash in 1893 which proved disastrous for the Washingtonian people. This caused a rise in Agrarian Populism throughout the state, and the populists within Washington, who had previously been only a tertiary factor in state/territorial politics began to grow into a defining element.

In 1890, while nationally Democrats won in a landslide, in Washington their gains were only meager, and they remained the minority. During the 1880s Washington had become more and more prosperous, but the Eastern agricultural areas did not share in the prosperity of the cities. In part this was caused by the highly monopolized nature of the new railroads. In addition, rising economic issues led to a crash in 1893 which proved disastrous for the Washingtonian people. This caused a rise in Agrarian Populism throughout the state, and the populists within Washington, who had previously been only a tertiary factor in state/territorial politics began to grow into a defining element.

In a surprise for the Republicans, who were expecting and did receive a general sweep in the 1900 elections, Rogers who had formally switched parties and joined the Democrats, was re-elected as governor. This upset was not long to last though, as in 1901 Rogers unexpectedly died. The line of succession promoted the Lieutenant Governor, a Republican named Henry McBride into the office, but rather than reverse Rogers' reforms, McBride actually furthered them. As a progressive Republican, McBride also saw corporations and lobbyists as an impediment to the growth of the state, and strongly pushed for busting monopolies. Under McBride the Republican Party shifted into support of a Railroad Commission in order to separate the railroads from politics, and after the "hardest floor battle" in a decade, with his support the commission finally came into being. With these victories McBride was generally very popular, but his own Republican Party which was heavily supported by, and as many claimed controlled by the railroad companies, began to conspire in order to prevent his re-election. To this effect after an extended political struggle, the Republican Party voted not to renominate McBride for the 1904 elections. He would later be applauded by historians as one of the state's best governors.

While in the short term, the Populist program was a failure and the fusion party quickly died, within twenty years almost all of their major points would become law. These points included the

In a surprise for the Republicans, who were expecting and did receive a general sweep in the 1900 elections, Rogers who had formally switched parties and joined the Democrats, was re-elected as governor. This upset was not long to last though, as in 1901 Rogers unexpectedly died. The line of succession promoted the Lieutenant Governor, a Republican named Henry McBride into the office, but rather than reverse Rogers' reforms, McBride actually furthered them. As a progressive Republican, McBride also saw corporations and lobbyists as an impediment to the growth of the state, and strongly pushed for busting monopolies. Under McBride the Republican Party shifted into support of a Railroad Commission in order to separate the railroads from politics, and after the "hardest floor battle" in a decade, with his support the commission finally came into being. With these victories McBride was generally very popular, but his own Republican Party which was heavily supported by, and as many claimed controlled by the railroad companies, began to conspire in order to prevent his re-election. To this effect after an extended political struggle, the Republican Party voted not to renominate McBride for the 1904 elections. He would later be applauded by historians as one of the state's best governors.

While in the short term, the Populist program was a failure and the fusion party quickly died, within twenty years almost all of their major points would become law. These points included the

Volume 2

* Meany, Edmond S.

''History of the State of Washington''

New York: Macmillan, 1909.

University of Washington Libraries: Digital Collections

302 images from the turn of the 20th century documenting the landscape, people, and cities and towns of Western Washington.

A web-based museum showcasing aspects of the rich history and culture of Washington State's Olympic Peninsula communities. Features cultural exhibits, curriculum packets and a searchable archive of over 12,000 items that includes historical photographs, audio recordings, videos, maps, diaries, reports and other documents.

101 images (ca. 1858–1903) collected and annotated by Thomas Prosch, one of Seattle's earliest pioneers. Images document scenes in Eastern Washington especially Chelan and vicinity, and Seattle's early history including the Seattle Fire of 1889.

Images (ca. 1880–1940) of Washington State, including forts and military installations, homesteads and residences, national parks and mountaineering, and industries and occupations, such as logging, mining and fishing.

A collection of writings, diaries, letters, and reminiscences that recount the early settlement of Washington, the establishment of homesteads and towns and the hardships faced by many of the early pioneers.

Secretary of State's Washington History website

Classics in Washington History

This digital collection of full-text books brings together rare, out of print titles for easy access by students, teachers, genealogists and historians. Visit Washington's early years through the lives of the men and women who lived and worked in Washington Territory and State.

Washington Historical Map Collection

The State Archives and the State Library hold extensive map collections dealing with the Washington State and the surrounding region. Maps for this digital collection will be drawn from state and territorial government records, historic books, federal documents and the Northwest collection.

Washington Historical Newspapers

Washington Territorial Timeline

To recognize the 150th anniversary of the birth of Washington, the State Archives has created a historical timeline of the Pacific Northwest and Washington Territory. With the help of pictures and documents from the State Archives, the timeline recounts the major political and social events that evolved Washington Territory into Washington State.

John M. Canse Pamphlet Collection

This collection includes booklets, pamphlets, and maps that detail the development of the regions, towns, and cities of the Pacific Northwest, especially Washington State.

Warren Wood Collection

This collection includes the glass negatives, photographs and appointment notebooks of Warren Wood, pioneer surveyor of the Pacific Northwest.

Spokane Historical

historical Spokane and Eastern Washington. * {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Washington (U.S. State) Washington

Oregon Territory

The Territory of Oregon was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from August 14, 1848, until February 14, 1859, when the southwestern portion of the territory was admitted to the United States, Union as the Oreg ...

from 1848 to 1853, after which it was separated from Oregon and established as Washington Territory

The Washington Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1853, until November 11, 1889, when the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Washington. It was created from the ...

following the efforts at the Monticello Convention. On November 11, 1889, Washington became the 42nd state of the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

.

Prehistory and cultures

Archaeological evidence shows that thePacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (PNW; ) is a geographic region in Western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though no official boundary exists, the most common ...

was one of the first populated areas in North America. Both animal and human bones dating back to 13,000 years old have been found across Washington and evidence of human habitation

Housing refers to a property containing one or more shelter as a living space. Housing spaces are inhabited either by individuals or a collective group of people. Housing is also referred to as a human need and human right, playing a crit ...

in the Olympic Peninsula

The Olympic Peninsula is a large peninsula in Western Washington that lies across Puget Sound from Seattle, and contains Olympic National Park. It is bounded on the west by the Pacific Ocean, the north by the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and the ...

dates back to approximately 9,000 BCE, 3,000 to 5,000 years after massive flooding of the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook language, Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin language, Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river headwater ...

which carved the Columbia Gorge.

Anthropologists estimate there were 125 distinct Northwest tribes and 50 languages and dialects in existence before the arrival of Euro-Americans in this region. Throughout the Puget Sound

Puget Sound ( ; ) is a complex estuary, estuarine system of interconnected Marine habitat, marine waterways and basins located on the northwest coast of the U.S. state of Washington (state), Washington. As a part of the Salish Sea, the sound ...

region, coastal tribes made use of the region's abundant natural resources, subsisting primarily on salmon, halibut, shellfish, and whale. Cedar was an important building material and was used by tribes to build both longhouses and large canoe

A canoe is a lightweight, narrow watercraft, water vessel, typically pointed at both ends and open on top, propelled by one or more seated or kneeling paddlers facing the direction of travel and using paddles.

In British English, the term ' ...

s. Clothing was also made from the bark of cedar trees. The Columbia River tribes became the richest of the Washington tribes through their control of Celilo Falls, historically the richest salmon fishing location in the Northwest. These falls on the Columbia River, east of present-day The Dalles, Oregon

The Dalles ( ;) formally the City of the Dalles and also called Dalles City, is an inland port, the county seat of and the largest city in Wasco County, Oregon, Wasco County, Oregon, United States. The population was 16,010 at the 2020 United ...

, were part of the path millions of salmon took to spawn. The presence of private wealth among the more aggressive coastal tribes encouraged gender divisions, as women took on prominent roles as traders and men participated in warring and captive-taking with other tribes. The eastern tribes, called the Plateau tribes, survived through seasonal hunting, fishing, and gathering. Tribal work among the Plateau Indians was also gender-divided, with both men and women responsible for equal parts of the food supply.

The principal tribes of the coastal areas include the Chinook, Lummi, Quinault, Makah

The Makah (; Makah: ') are an Indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest Coast living in Washington, in the northwestern part of the continental United States. They are enrolled in the federally recognized Makah Indian Tribe of the Makah I ...

, Quileute, and Snohomish. The Plateau tribes include the Klickitat, Cayuse, Nez Percé, Okanogan, Palouse

The Palouse ( ) is a geographic region of the northwestern United States, encompassing parts of North Central Idaho, north central Idaho, southeastern Washington (part of eastern Washington), and by some definitions, parts of northeast Oregon. ...

, Spokane

Spokane ( ) is the most populous city in eastern Washington and the county seat of Spokane County, Washington, United States. It lies along the Spokane River, adjacent to the Selkirk Mountains, and west of the Rocky Mountain foothills, south ...

, Wenatchee, and Yakama. Today, Washington contains more than 20 Indian reservations, the largest of which is for the Yakama.

At Ozette, in the northwest corner of the state, an ancient village was covered by a mud slide, perhaps triggered by an earthquake about 500 years ago. More than 50,000 well-preserved artifacts have been found and cataloged, many of which are now on display at the Makah Cultural and Research Center in Neah Bay. Other sites have also revealed how long people have been there. Thumbnail-sized quartz knife blades found at the Hoko River site near Clallam Bay are believed to be 2,500 years old.

European Colony

Early European and American exploration

The firstEurope

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

an record of a landing on the future Washington state

Washington, officially the State of Washington, is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is often referred to as Washington State to distinguish it from the national capital, both named after George Washington ...

coast was in 1774 by Spaniard

Spaniards, or Spanish people, are a Romance languages, Romance-speaking Ethnicity, ethnic group native to the Iberian Peninsula, primarily associated with the modern Nation state, nation-state of Spain. Genetics, Genetically and Ethnolinguisti ...

mariner Juan José Pérez Hernández (c.1725-1775), sailing for the Kingdom of Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

/ Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered ...

. One year later, another Spanish-Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

Captain Don Bruna de Heceta (1747-1807), on board the ''Santiago'', part of a two-ship flotilla with the accompanying ''Sonora'', landed near the mouth of the Quinault River and claimed the coastal lands for Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

as far north up to the already present colonists of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

possessions, originally discovered / claimed by Captain Vitus Bering

Vitus Jonassen Bering ( , , ; baptised 5 August 1681 – 19 December 1741),All dates are here given in the Julian calendar, which was in use throughout Russia at the time. also known as Ivan Ivanovich Bering (), was a Danish-born Russia ...

(1681-1741), (a Danish mariner sailing the coasts of the northern Pacific for Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

and its rapidly expanding Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

across the Bering Strait

The Bering Strait ( , ; ) is a strait between the Pacific and Arctic oceans, separating the Chukchi Peninsula of the Russian Far East from the Seward Peninsula of Alaska. The present Russia–United States maritime boundary is at 168° 58' ...

and Bering Sea

The Bering Sea ( , ; rus, Бе́рингово мо́ре, r=Béringovo móre, p=ˈbʲerʲɪnɡəvə ˈmorʲe) is a marginal sea of the Northern Pacific Ocean. It forms, along with the Bering Strait, the divide between the two largest landmasse ...

(named for him) coming from eastern Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

and Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

) further up the Pacific coast in Russian America

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

since the 1740s

File:1740s montage.jpg, 335x335px, From top left, clockwise: The War of Jenkins' Ear, a conflict between the British and Spanish Empires lasting from 1739 to 1748. The War of the Austrian Succession from 1740 to 1748, caused by the death of Empero ...

(modern Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

, purchased by the United States in 1867).

In 1778, the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

explorer Captain James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

(1728-1779), sighted Cape Flattery, at the entrance of the Puget Sound

Puget Sound ( ; ) is a complex estuary, estuarine system of interconnected Marine habitat, marine waterways and basins located on the northwest coast of the U.S. state of Washington (state), Washington. As a part of the Salish Sea, the sound ...

at the Strait of Juan de Fuca

The Strait of Juan de Fuca (officially named Juan de Fuca Strait in Canada) is a body of water about long that is the Salish Sea's main outlet to the Pacific Ocean. The Canada–United States border, international boundary between Canada and the ...

. But the strait itself was not found until almost a decade later when Charles William Barkley (c.1759-1832), captain of the ''Imperial Eagle

The eagle is used in heraldry as a charge, as a supporter, and as a crest. Heraldic eagles can be found throughout world history like in the Achaemenid Empire or in the present Republic of Indonesia. The European post-classical symbolism of ...

'', sighted it in 1787. Captain Barkley named it for the earlier Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many countries in the Americas

**Spanish cuisine

**Spanish history

**Spanish culture

...

-Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

explorer Juan de Fuca (1536-1602). The Spanish-British treaties of the Nootka Convention

The Nootka Sound Conventions were a series of three agreements between the Kingdom of Spain and the Kingdom of Great Britain, signed in the 1790s, which averted a war between the two countries over overlapping claims to portions of the Pacific No ...

s of the 1790s ended Spanish exclusivity and opened the Northwest North America Coast to explorers and traders from other nations, most important being the future British, Russians, and Americans of the United States. Further explorations of the straits were performed again by Spanish-Peru

Peru, officially the Republic of Peru, is a country in western South America. It is bordered in the north by Ecuador and Colombia, in the east by Brazil, in the southeast by Bolivia, in the south by Chile, and in the south and west by the Pac ...

vian explorer Manuel Quimper (1757-1844), in 1790 and a year later by Francisco de Eliza (1759-1825), in 1791 and then the following year of 1792, came the arrival by British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

Captain George Vancouver

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain George Vancouver (; 22 June 1757 – 10 May 1798) was a Royal Navy officer and explorer best known for leading the Vancouver Expedition, which explored and charted North America's northwestern West Coast of the Uni ...

(1757-1798). Captain Vancouver claimed the sound and coast for Britain and named the waters originally to the far south of the Tacoma Narrows as the Puget's Sound, in honor of Peter Puget

Peter Puget (1765 – 31 October 1822) was an officer in the Royal Navy, best known for his exploration of Puget Sound, which is named for him.

Midshipman Puget

Puget's ancestors had fled France for Britain during Louis XIV's persecution of the ...

(1765-1822), (who was the young Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

naval lieutenant accompanying him on the Vancouver Expedition

The Vancouver Expedition (1791–1795) was a four-and-a-half-year voyage of exploration and diplomacy, commanded by Captain George Vancouver of the Royal Navy. The British expedition circumnavigated the globe and made contact with five continen ...

of 1791-1795, (later in his naval career he became a rear admiral

Rear admiral is a flag officer rank used by English-speaking navies. In most European navies, the equivalent rank is called counter admiral.

Rear admiral is usually immediately senior to commodore and immediately below vice admiral. It is ...

). The name later came to be used also for the waters north of the Tacoma Narrows as well. Captain Vancouver and his expedition mapped the Pacific coast of western North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

in 1792 to 1794, including the then large tract of the Oregon Country

Oregon Country was a large region of the Pacific Northwest of North America that was subject to a long Oregon boundary dispute, dispute between the United Kingdom and the United States in the early 19th century. The area, which had been demarcat ...

composed later of future territories

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, belonging or connected to a particular country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually a geographic area which has not been granted the powers of self-government, ...

/ then states

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

of Oregon

Oregon ( , ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is a part of the Western U.S., with the Columbia River delineating much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while t ...

and Washington / Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest and Mountain states, Mountain West subregions of the Western United States. It borders Montana and Wyoming to the east, Nevada and Utah to the south, and Washington (state), ...

, plus to the north of the Canadian

Canadians () are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their being ''C ...

colonies of British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestown, ...

of the Colony of Vancouver Island

The Colony of Vancouver Island, officially known as the Island of Vancouver and its Dependencies, was a Crown colony of British North America from 1849 to 1866, after which it was united with the mainland to form the Colony of British Columbia. ...

on off-shore Vancouver Island

Vancouver Island is an island in the northeastern Pacific Ocean and part of the Canadian province of British Columbia. The island is in length, in width at its widest point, and in total area, while are of land. The island is the largest ...

and the mainland's Columbia District / then later renamed Department, on the continent. Then subsequently after several decades in 1858 / 1866 into the Colony of British Columbia The Colony of British Columbia refers to one of two colonies of British North America, located on the Pacific coast of modern-day Canada:

* Colony of British Columbia (1858–1866)

* Colony of British Columbia (1866–1871)

See also

* History of ...

, eventually merging the island and mainland becoming by 1866, the modern British Columbia

British Columbia is the westernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Situated in the Pacific Northwest between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains, the province has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that ...

, later joining the 1867 confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

formed further east of the Dominion of Canada

While a variety of theories have been postulated for the name of Canada, its origin is now accepted as coming from the St. Lawrence Iroquoian word , meaning 'village' or 'settlement'. In 1535, indigenous inhabitants of the present-day Quebec C ...

four years later in 1871 as the western-most province

A province is an administrative division within a country or sovereign state, state. The term derives from the ancient Roman , which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire, Roman Empire's territorial possessions ou ...

) in the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (PNW; ) is a geographic region in Western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though no official boundary exists, the most common ...

region.sea captain

A sea captain, ship's captain, captain, master, or shipmaster, is a high-grade licensed mariner who holds ultimate command and responsibility of a merchant vessel. The captain is responsible for the safe and efficient operation of the ship, inc ...

of a merchantman cargo vessel, discovered the mouth of the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook language, Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin language, Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river headwater ...

along the West Coast of the North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

continent in the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (PNW; ) is a geographic region in Western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though no official boundary exists, the most common ...

region in 1792, naming the river after his ship ''"Columbia"'' and later establishing a trade in sea otter

The sea otter (''Enhydra lutris'') is a marine mammal native to the coasts of the northern and eastern Pacific Ocean, North Pacific Ocean. Adult sea otters typically weigh between , making them the heaviest members of ...

, seal

Seal may refer to any of the following:

Common uses

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, also called "true seal"

** Fur seal

** Eared seal

* Seal ( ...

and walrus

The walrus (''Odobenus rosmarus'') is a large pinniped marine mammal with discontinuous distribution about the North Pole in the Arctic Ocean and subarctic seas of the Northern Hemisphere. It is the only extant species in the family Odobeni ...

fur pelts in the surrounding Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (PNW; ) is a geographic region in Western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though no official boundary exists, the most common ...

region. The Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. The Corps of Discovery was a select gro ...

(1804-1806), with their Corps of Discovery sent by the direction of third President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

(1743-1826, served 1801-1809), entered the region from the east on October 10, 1805, having journeyed upstream on the Missouri River

The Missouri River is a river in the Central United States, Central and Mountain states, Mountain West regions of the United States. The nation's longest, it rises in the eastern Centennial Mountains of the Bitterroot Range of the Rocky Moun ...

and through the passes in the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in great-circle distance, straight-line distance from the northernmost part of Western Can ...

chain, then downstream through the Snake River

The Snake River is a major river in the interior Pacific Northwest region of the United States. About long, it is the largest tributary of the Columbia River, which is the largest North American river that empties into the Pacific Ocean. Begin ...

and Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook language, Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin language, Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river headwater ...

valleys to the coast. Explorers and scientific observers Meriwether Lewis

Meriwether Lewis (August 18, 1774 – October 11, 1809) was an American explorer, soldier, politician, and public administrator, best known for his role as the leader of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery, with ...

(1774-1809), and William Clark

William Clark (August 1, 1770 – September 1, 1838) was an American explorer, soldier, Indian agent, and territorial governor. A native of Virginia, he grew up in pre-statehood Kentucky before later settling in what became the state of Misso ...

(1770-1838), were surprised by the differences in the various Native Americans / Indian tribes in the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (PNW; ) is a geographic region in Western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though no official boundary exists, the most common ...

from those they had encountered earlier in the expedition trip on the Great Plains

The Great Plains is a broad expanse of plain, flatland in North America. The region stretches east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, and grassland. They are the western part of the Interior Plains, which include th ...

, noting, in particular, the increased status of women among both coastal and upper plateau / mountain tribes. Lewis hypothesized that the equality of women and the elderly with men, was linked to more evenly distributed economic roles.

British / Canadian explorer, surveyor / cartographer and fur trader David Thompson (1770-1857), extensively explored the

British / Canadian explorer, surveyor / cartographer and fur trader David Thompson (1770-1857), extensively explored the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook language, Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin language, Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river headwater ...

two years later, commencing in 1807. Four years later in 1811, he became the first European to navigate the entire length of the river westward downstream to its mouth on the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

. Along the way he posted a notice where it joins the Snake River

The Snake River is a major river in the interior Pacific Northwest region of the United States. About long, it is the largest tributary of the Columbia River, which is the largest North American river that empties into the Pacific Ocean. Begin ...

claiming the land for Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

(United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

/ British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

), and stating the intention of their North West Company

The North West Company was a Fur trade in Canada, Canadian fur trading business headquartered in Montreal from 1779 to 1821. It competed with increasing success against the Hudson's Bay Company in the regions that later became Western Canada a ...

to build a fort and trading post there. Subsequently, the Fort Nez Perces trading post, was established (near present-day Walla Walla, Washington

Walla Walla ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Walla Walla County, Washington, United States. It had a population of 34,060 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, estimated to have decreased to 33,339 as of 2023. The combined populat ...

). Thompson's posted notice was later found by the party of Astorians of John Jacob Astor

John Jacob Astor (born Johann Jakob Astor; July 17, 1763 – March 29, 1848) was a German-born American businessman, merchant, real estate mogul, and investor. Astor made his fortune mainly in a fur trade monopoly, by exporting History of opiu ...

(1763-1848) looking to establish an inland fur trading post / station. It contributed to American mercantile fur trader leader David Stuart (1765-1853)'s choice, on behalf of the competing Americans' and Astor's short-lived Pacific Fur Company

The Pacific Fur Company (PFC) was an American fur trade venture wholly owned and funded by John Jacob Astor that functioned from 1810 to 1813. It was based in the Pacific Northwest, an area contested over the decades among the United Kingdom of G ...

(1810-1813), of choosing a more northerly site for their operations which were then established at Fort Okanogan

Fort Okanogan (also spelled Fort Okanagan but only by nonresident Canadians) was founded in 1811 on the confluence of the Okanogan and Columbia Rivers as a fur trade outpost. Originally built for John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company, it was ...

(in modern Okanogan County, near Brewster, Washington).

By the time American settlers started arriving from the east in the 1830s

The 1830s (pronounced "eighteen-thirties") was a decade of the Gregorian calendar that began on January 1, 1830, and ended on December 31, 1839.

In this decade, the world saw a rapid rise of imperialism and colonialism, particularly in Asia and ...

, a population of Métis

The Métis ( , , , ) are a mixed-race Indigenous people whose historical homelands include Canada's three Prairie Provinces extending into parts of Ontario, British Columbia, the Northwest Territories and the northwest United States. They ha ...

(mixed race) people had grown from centuries of contact with early-Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

an fur traders partnering with Native American women. Before larger numbers of Caucasian European American

European Americans are Americans of European ancestry. This term includes both people who descend from the first European settlers in the area of the present-day United States and people who descend from more recent European arrivals. Since th ...

women began moving to the territory from the east and the United States in the 1830s

The 1830s (pronounced "eighteen-thirties") was a decade of the Gregorian calendar that began on January 1, 1830, and ended on December 31, 1839.

In this decade, the world saw a rapid rise of imperialism and colonialism, particularly in Asia and ...

, traders and fur trade workers generally sought out Métis or Native American women for wives and companionship or for domestic chores. Early European-Indigenous mixed ancestry settlements resulted from these partnerships as an outgrowth of the fur trade then growing into the work of agriculture raising small crops of grain and vegetables harvested for food at: Cowlitz Prairie (Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver was a 19th-century fur trading post built in the winter of 1824–1825. It was the headquarters of the Hudson's Bay Company's Columbia Department, located in the Pacific Northwest. Named for Captain George Vancouver, the fort was ...

) and Frenchtown, Washington

( Fort Nez Percés).

American–British joint occupation disputes

American interests in the region grew as part of their concept ofmanifest destiny

Manifest destiny was the belief in the 19th century in the United States, 19th-century United States that American pioneer, American settlers were destined to expand westward across North America, and that this belief was both obvious ("''m ...

. Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

had ceded their rights north of the 42nd Parallel to the United States by the terms of the earlier 1819 Adams-Onís Treaty, (but not possession, which was disallowed by the terms of the Nootka Conventions).

Britain had long-standing commercial interests through the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), originally the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading Into Hudson’s Bay, is a Canadian holding company of department stores, and the oldest corporation in North America. It was the owner of the ...

and a well-established network of fur trading stations and forts along the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook language, Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin language, Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river headwater ...

in what it called the Columbia District

The Columbia District was a fur-trading district in the Pacific Northwest region of North America, in both the United States and British North America in the 19th century. Much of its territory overlapped with the temporarily jointly occupi ...

. These were headquartered from Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver was a 19th-century fur trading post built in the winter of 1824–1825. It was the headquarters of the Hudson's Bay Company's Columbia Department, located in the Pacific Northwest. Named for Captain George Vancouver, the fort was ...

in present-day Vancouver, Washington.

By the

By the Treaty of 1818

The Convention respecting fisheries, boundary and the restoration of slaves, also known as the London Convention, Anglo-American Convention of 1818, Convention of 1818, or simply the Treaty of 1818, is an international treaty signed in 1818 betw ...

, following from the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

(1812-1815), Great Britain and the United States established the 49th parallel as the international border stretching west to the Continental Divide

A continental divide is a drainage divide on a continent such that the drainage basin on one side of the divide feeds into one ocean or sea, and the basin on the other side either feeds into a different ocean or sea, or else is endorheic, not ...

of the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in great-circle distance, straight-line distance from the northernmost part of Western Can ...

; but agreed to temporary joint control and occupancy of the Oregon Country

Oregon Country was a large region of the Pacific Northwest of North America that was subject to a long Oregon boundary dispute, dispute between the United Kingdom and the United States in the early 19th century. The area, which had been demarcat ...

/ Columbia District

The Columbia District was a fur-trading district in the Pacific Northwest region of North America, in both the United States and British North America in the 19th century. Much of its territory overlapped with the temporarily jointly occupi ...

for the next few years.

In 1824, the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

(Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

) signed an agreement with the U.S. acknowledging it had no claims south of the parallel line 54-40 of latitude north and Russia signed a similar treaty with Britain the following in 1825, thereby establishing the southern limits of its coastal possessions in Russian America

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

(modern Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

) in the northwestern corner of the North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

n continent until its sale to the U.S. 43 years later in 1867.

British-American joint occupancy was renewed, but on a year-to-year basis in 1827. Eventually, increased tension between U.S. settlers arriving by way of the Oregon trail

The Oregon Trail was a east–west, large-wheeled wagon route and Westward Expansion Trails, emigrant trail in North America that connected the Missouri River to valleys in Oregon Territory. The eastern part of the Oregon Trail crossed what ...

and already resident fur traders

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mos ...

led to the intensified Oregon boundary dispute

The Oregon boundary dispute or the Oregon Question was a 19th-century territorial dispute over the political division of the Pacific Northwest of North America between several nations that had competing territorial and commercial aspirations in ...

, a major political issue in the American 1844 presidential election. It resulting in the election victory of 11th President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (; November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. A protégé of Andrew Jackson and a member of the Democratic Party, he was an advocate of Jacksonian democracy and ...

(1795-1849, served 1845-1849), of Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

with his expansionist foreign policies. Two years later, on June 15, 1846, Britain ceded its claims to the lands south of the 49th parallel, and the U.S. ceded its claims to the north of the same line, resulting in the present-day Canada–U.S. international border, resulting in the amicable splitting of the Oregon/Columbia territory along the 49th parallel line, extending it westward from the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes spanning the Canada–United States border. The five lakes are Lake Superior, Superior, Lake Michigan, Michigan, Lake Huron, H ...

through the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in great-circle distance, straight-line distance from the northernmost part of Western Can ...

chain all the way to the west coast at the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

(with the exception of the off-shore Vancouver Island

Vancouver Island is an island in the northeastern Pacific Ocean and part of the Canadian province of British Columbia. The island is in length, in width at its widest point, and in total area, while are of land. The island is the largest ...

, assigned to Britain) between the two nations, in the negotiated Oregon Treaty

The Oregon Treaty was a treaty between the United Kingdom and the United States that was signed on June 15, 1846, in Washington, D.C. The treaty brought an end to the Oregon boundary dispute by settling competing American and British claims to ...

of 1846.

A quarter-century later in 1872, an additional arbitration process settled the minor boundary dispute from the so-called Pig War of 1859 and established the U.S.A.–Canada border line through the off-shore San Juan Islands

The San Juan Islands is an archipelago in the Pacific Northwest of the United States between the U.S. state of Washington and Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada. The San Juan Islands are part of Washington state, and form the core of ...

and Gulf Islands

The Gulf Islands is a group of islands in the Salish Sea between Vancouver Island and the British Columbia Coast, mainland coast of British Columbia.

Etymology

The name "Gulf Islands" comes from "Gulf of Georgia", the original term used by Geor ...

on the Pacific coast.

Part of Oregon Territory (1846–1853)

In 1848, the

In 1848, the Oregon Territory

The Territory of Oregon was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from August 14, 1848, until February 14, 1859, when the southwestern portion of the territory was admitted to the United States, Union as the Oreg ...

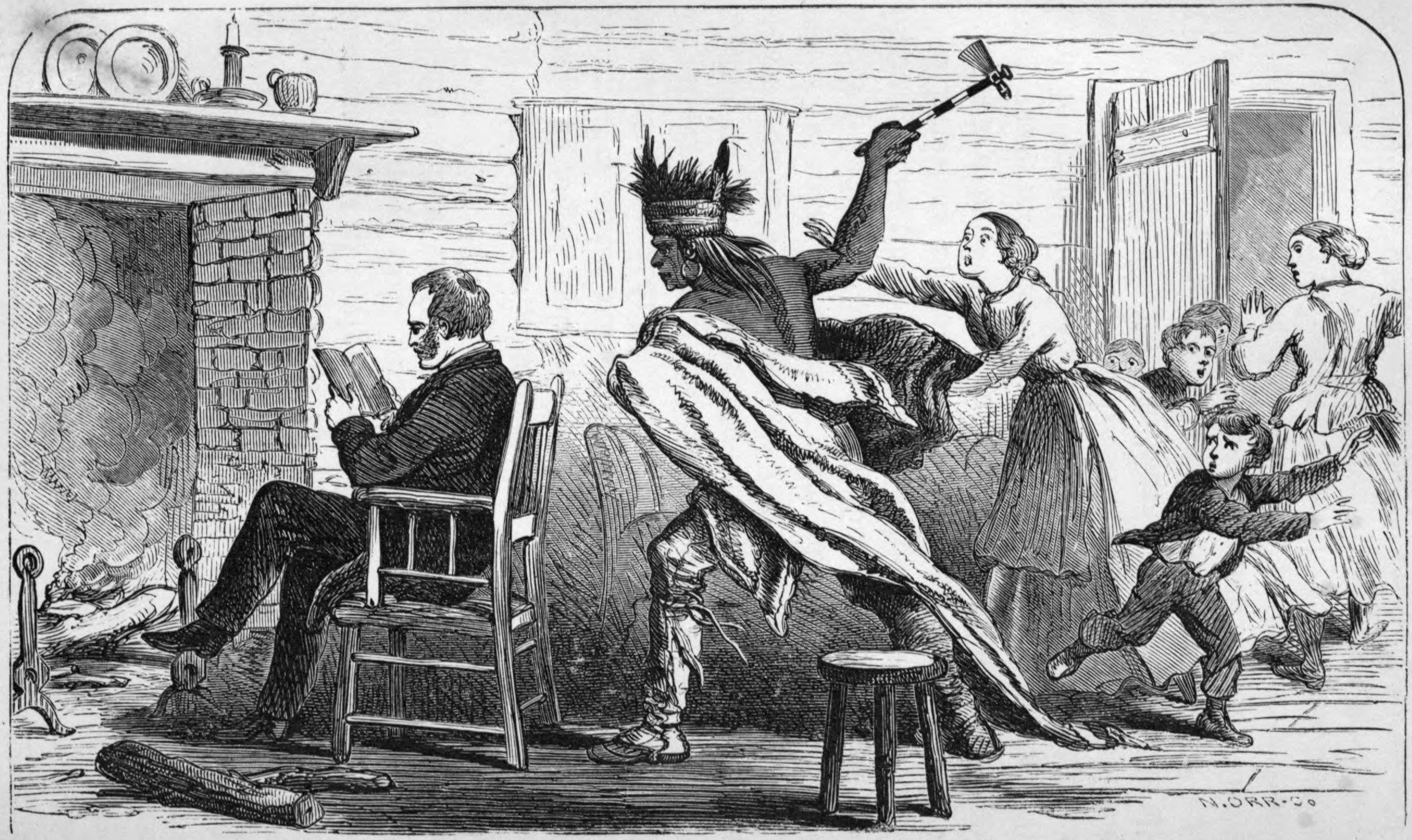

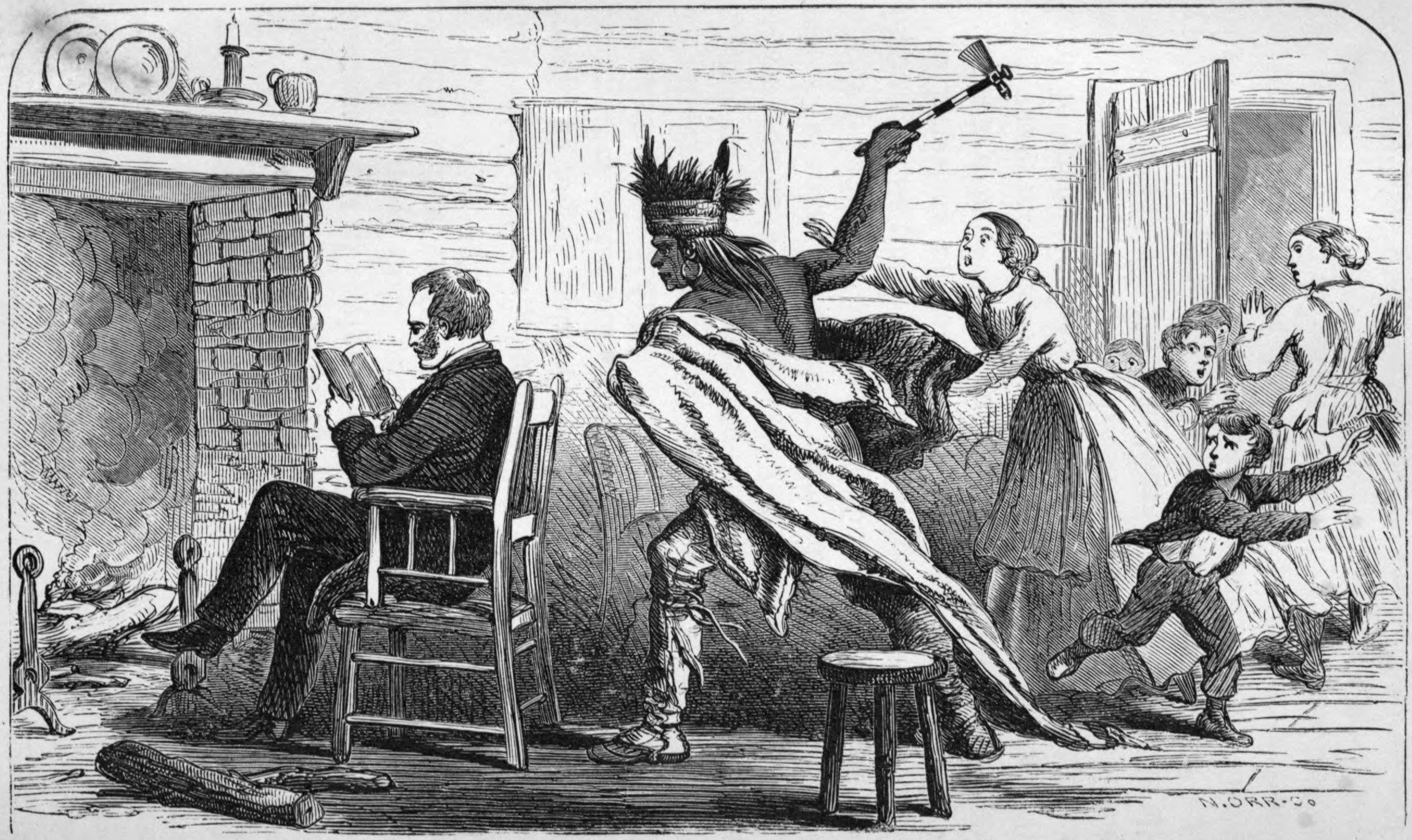

, composed of present-day Washington, Oregon, and Idaho as well as parts of Montana and Wyoming, was established. Settlements in the eastern part of the state were largely agricultural and focused around missionary establishments in the Walla Walla Valley. Missionaries attempted to 'civilize' the Indians, often in ways that disregarded or misunderstood native practices. When missionaries Dr. Marcus Whitman and Narcissa Whitman refused to leave their mission as racial tensions mounted in 1847, 13 American missionaries were killed by Cayuse and Umatilla Indians. Explanations of the 1847 Whitman massacre in Walla Walla include outbreaks of disease, resentment over harsh attempts at conversion of both religion and way of life, and contempt of the native Indians shown by the missionaries, particularly by Narcissa Whitman, the first white American woman in the Oregon Territory.

This event triggered the Cayuse War against the Natives, wherein the Provisional Legislature of Oregon in 1847 immediately raised companies of volunteers to go to war, if necessary, against the Cayuse, and, to the discontent of some of the militia leaders, also sent a peace commission. The

This event triggered the Cayuse War against the Natives, wherein the Provisional Legislature of Oregon in 1847 immediately raised companies of volunteers to go to war, if necessary, against the Cayuse, and, to the discontent of some of the militia leaders, also sent a peace commission. The United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

later came to support the militia forces. These militia forces, eager for action, provoked both friendly and hostile Indians. In 1850, five Cayuse were convicted for murdering the Whitmans in 1847 and hanged. Sporadic bloodshed continued until 1855, when the Cayuse were decimated, defeated, bereft of their tribal lands, and placed on the Umatilla Indian Reservation in northeastern Oregon.

As American settlers moved west along the Oregon Trail, some traveled through the northern part of the Oregon Territory and settled in the Puget Sound area. The first European settlement in the Puget Sound

Puget Sound ( ; ) is a complex estuary, estuarine system of interconnected Marine habitat, marine waterways and basins located on the northwest coast of the U.S. state of Washington (state), Washington. As a part of the Salish Sea, the sound ...

area in the west of present-day Washington State came in 1833 at the British Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), originally the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading Into Hudson’s Bay, is a Canadian holding company of department stores, and the oldest corporation in North America. It was the owner of the ...

's Fort Nisqually

Fort Nisqually was an important fur trade, fur trading and farming post of the Hudson's Bay Company in the Puget Sound area, part of the Hudson's Bay Company's Columbia Department. It was located in what is now DuPont, Washington. Today it is a ...

, a farm and fur-trading post later operated by the Puget's Sound Agricultural Company (incorporated in 1840), a subsidiary of the Hudson's Bay Company. Washington's pioneer founder, Michael Simmons, along with the black pioneer George Washington Bush and his Caucasian wife, Isabella James Bush, from Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

and Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

, respectively, led four white families into the territory and settled New Market, now known as Tumwater, in 1846. They settled in Washington to avoid Oregon's racist settlement-laws. After them, many more settlers, migrating overland along the Oregon trail

The Oregon Trail was a east–west, large-wheeled wagon route and Westward Expansion Trails, emigrant trail in North America that connected the Missouri River to valleys in Oregon Territory. The eastern part of the Oregon Trail crossed what ...

, wandered north to settle in the Puget Sound

Puget Sound ( ; ) is a complex estuary, estuarine system of interconnected Marine habitat, marine waterways and basins located on the northwest coast of the U.S. state of Washington (state), Washington. As a part of the Salish Sea, the sound ...

area.

Washington Territory (1853–1889)

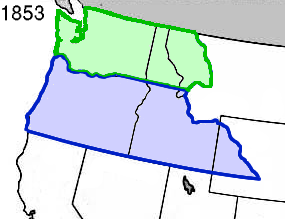

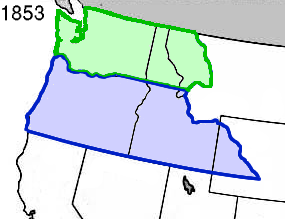

Washington Territory

The Washington Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1853, until November 11, 1889, when the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Washington. It was created from the ...

, which included Washington and pieces of Idaho and Montana, was formed from Oregon Territory in 1853. Isaac Ingalls Stevens, a Mexican-American War

Mexican Americans are Americans of full or partial Mexican descent. In 2022, Mexican Americans comprised 11.2% of the US population and 58.9% of all Hispanic and Latino Americans. In 2019, 71% of Mexican Americans were born in the United State ...

veteran, had heavily supported the candidacy of President Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. A northern Democratic Party (United States), Democrat who believed that the Abolitionism in the United States, abolitio ...

, a fellow veteran. In 1853 Stevens successfully applied to President Pierce for the governorship of the new Washington Territory, a post that also carried the title of Superintendent of Indian Affairs.

Lumber industries drew settlers to the territory. Coastal cities, like Seattle

Seattle ( ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Washington and in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. With a population of 780,995 in 2024, it is the 18th-most populous city in the United States. The city is the cou ...

(founded in 1851 and originally called "Duwamps"), were established. Though wagon trains had previously carried entire families to the Oregon Territory, these early trading settlements were populated primarily with single young men. Liquor, gambling, and prostitution were ubiquitous, supported in Seattle by one of the city's founders, David Swinson "Doc" Maynard, who believed that well-run prostitution could be a functional part of the economy. The Fraser Gold Rush

The Fraser Canyon Gold Rush, (also Fraser Gold Rush and Fraser River Gold Rush) began in 1858 after gold was discovered on the Thompson River in British Columbia at its confluence with the Nicoamen River a few miles upstream from the Thompson's c ...

in what would, as a result, become the Colony of British Columbia The Colony of British Columbia refers to one of two colonies of British North America, located on the Pacific coast of modern-day Canada:

* Colony of British Columbia (1858–1866)

* Colony of British Columbia (1866–1871)

See also

* History of ...

saw a flurry of settlement and merchant activity in northern Puget Sound which gave birth to Port Townsend (in 1851) and Whatcom (founded in 1858, later becoming Bellingham) as commercial centres, at first attempting to rival Victoria on Vancouver Island as a disembarkation point of the goldfields until the governor of the Colony of Vancouver Island

The Colony of Vancouver Island, officially known as the Island of Vancouver and its Dependencies, was a Crown colony of British North America from 1849 to 1866, after which it was united with the mainland to form the Colony of British Columbia. ...

ordered that all traffic to the Fraser River go via Victoria. Despite the limitation on goldfield-related commerce, many men who left the "Fraser River Humbug" (as the rush was for a while misnamed) settled in Whatcom and Island counties. Some of these were settlers on San Juan Island during the Pig War of 1859.

Upon the admission of the State of Oregon

Oregon ( , ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is a part of the Western U.S., with the Columbia River delineating much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while t ...

to the union in 1859, the eastern portions of the Oregon Territory

The Territory of Oregon was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from August 14, 1848, until February 14, 1859, when the southwestern portion of the territory was admitted to the United States, Union as the Oreg ...

, including southern Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest and Mountain states, Mountain West subregions of the Western United States. It borders Montana and Wyoming to the east, Nevada and Utah to the south, and Washington (state), ...

, portions of Wyoming

Wyoming ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States, Western United States. It borders Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho t ...

west of the continental divide (then Nebraska Territory

The Territory of Nebraska was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until March 1, 1867, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of Nebraska. The Nebrask ...

), and a small portion of present-day Ravalli County, Montana

Ravalli County is a county in the southwestern part of the U.S. state of Montana. As of the 2020 census, the population was 44,174. Its county seat is Hamilton.

Ravalli County is part of a north–south mountain valley bordered by the Sapphi ...

were annexed to the Washington Territory. In 1863, the area of Washington Territory east of the Snake River and the 117th meridian west was reorganized as part of the newly formed Idaho Territory

The Territory of Idaho was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 3, 1863, until July 3, 1890, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as Idaho.

History

1860s

The territory ...

, leaving that territory with only the lands within the current boundaries of the State of Washington.

The "Indian Wars" (1855–1858)

The conflicts over the possession of land between the Indians and the American settlers led the Americans in 1855, by the treaties at the Walla Walla Council, to coerce not only the Cayuse, but also the Walla Walla and the Umatilla tribes, to the Umatilla Indian Reservation in northeastern Oregon; fourteen other tribal groups to the Yakama Indian Reservation in southern Washington State; and theNez Perce

The Nez Perce (; autonym in Nez Perce language: , meaning 'we, the people') are an Indigenous people of the Plateau who still live on a fraction of the lands on the southeastern Columbia River Plateau in the Pacific Northwest. This region h ...

to a reservation in the border region of Washington, Oregon and Idaho.

That same year, gold was discovered in the newly established Yakama reservation and white miners encroached upon these lands, with Washington Territory beginning to consider annexing them. While Governor Stevens generally avoided some of the more genocidal

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" b ...

rhetoric that was popular among some settlers, historian David M. Buerge charges that Stevens' "timetable asreckless; hat

A hat is a Headgear, head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorpor ...

the whole enterprise was organized in profound ignorance of native society, culture, and history,” and that “ e twenty-thousand-odd aboriginal inhabitants who were assumed to be in rapid decline, were given a brutal choice: they would adapt to white society or they could disappear.”

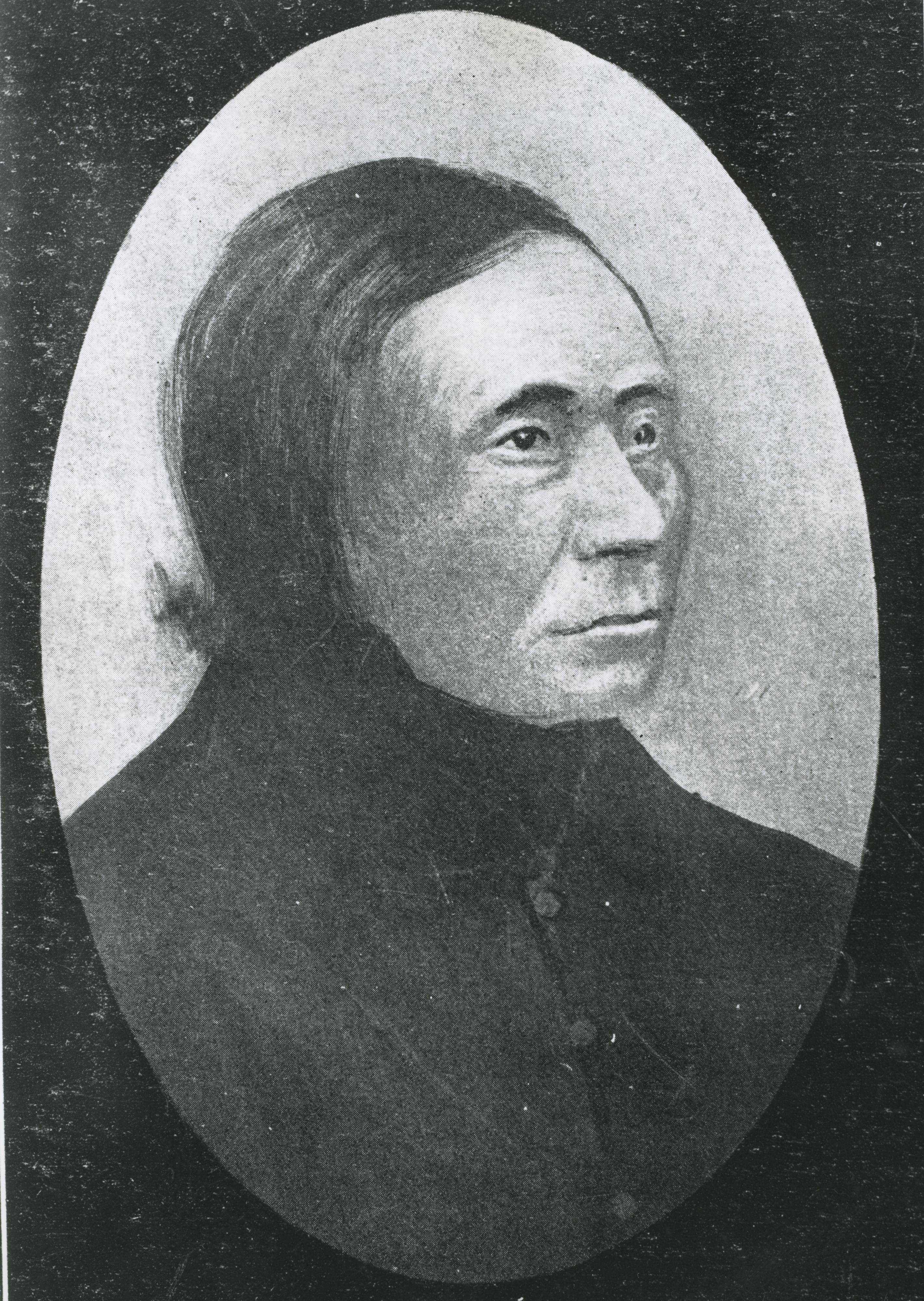

A treaty was presented to Chief Leschi of the Nisqually

Nisqually, Niskwalli, or Nisqualli may refer to:

People

* Nisqually people, a Coast Salish ethnic group

* Nisqually Indian Tribe of the Nisqually Reservation, federally recognized tribe

** Nisqually Indian Reservation, the tribe's reservation in ...

(along with other tribes), and while it provided concessions such as fishing rights, the main crux of the so-called Treaty of Medicine Creek was that it required: "The said tribes and bands of Indians hereby cede, relinquish and convey to the United States, all their right, title, and interest in and to the lands and country occupied by them."

Leschi was outraged and pulled out of the negotiations, preferring war to the loss of his tribe's ancestral lands. While it is not clear who fired the first shots, this standoff quickly escalated into violence as Washington Territorial militias began to exchange fire with Nisqually soldiers. This conflict would come to be known as the Puget Sound War

The Puget Sound War was an armed conflict that took place in the Puget Sound area of the state of Washington in 1855–56, between the United States military, local militias and members of the Native American tribes of the Nisqually, Muck ...

.

In 1856, Chief Leschi of the Nisqually was finally captured after one of the largest battles of the war. Stevens, who was seeking to punish Leschi for what he considered a troublesome revolt, had Leschi charged with the murder of a member of the Washingtonian militia. Leschi's argument in his defense was that he was not at the scene of the killing, but that even if he was the killing had been an act of war and was thus not murder. The initial trial ended in a hung jury after the judge told jurors that if they believed the killing of the militiaman was an act of war, they could not find Leschi guilty of murder. A second trial, without this note to the jury, ended in Leschi being convicted of murder and sentenced to execution. Interference by those who opposed the execution were able to stall it for months, but in the end they could not prevent it. Chief Leschi was formally exonerated of his crimes in 2014.

Concurrent with the Nisqually negotiations, tensions with other local tribes also continued to escalate. In one instance a group of Washingtonians assaulted and murdered a Yakama mother, her daughter, and her newborn infant. The woman's husband Mosheel, the son of the Yakama tribe's chieftain, gathered up a posse, tracked down the miners and killed them. The Bureau of Indian Affairs sent out an agent named Andrew Bolon to investigate, but before reaching the crime scene the chief of the Yakama intercepted him and warned Bolon that Mosheel was too dangerous to be taken in. Taking heed of this warning, Bolon decided to return to the Bureau to report his findings. He joined a traveling group of Yakama on his return trip, and while they walked he told them why he was in the area, about the unexplained murder that had happened. Unbeknownst to Bolon, the rest of the trip would be taken up by argument between the natives in a language he did not understand, as the leader of the group, Mosheel, argued for the murder of Bolon. Before he was stabbed in the throat, Bolon reportedly yelled in Chinook dialect, "I did not come to fight you!"

Washington Territory immediately mobilized for war, and sent the Territorial Militia to put down what it saw as a rebellion. The tribes - first the Yakama, eventually joined by the Walla Walla and the Cayuse - united together to fight the Americans in what is called the Yakima War. The U.S. Army sent troops and a number of raids and battles took place. In 1858, the Americans, at the

In 1856, Chief Leschi of the Nisqually was finally captured after one of the largest battles of the war. Stevens, who was seeking to punish Leschi for what he considered a troublesome revolt, had Leschi charged with the murder of a member of the Washingtonian militia. Leschi's argument in his defense was that he was not at the scene of the killing, but that even if he was the killing had been an act of war and was thus not murder. The initial trial ended in a hung jury after the judge told jurors that if they believed the killing of the militiaman was an act of war, they could not find Leschi guilty of murder. A second trial, without this note to the jury, ended in Leschi being convicted of murder and sentenced to execution. Interference by those who opposed the execution were able to stall it for months, but in the end they could not prevent it. Chief Leschi was formally exonerated of his crimes in 2014.

Concurrent with the Nisqually negotiations, tensions with other local tribes also continued to escalate. In one instance a group of Washingtonians assaulted and murdered a Yakama mother, her daughter, and her newborn infant. The woman's husband Mosheel, the son of the Yakama tribe's chieftain, gathered up a posse, tracked down the miners and killed them. The Bureau of Indian Affairs sent out an agent named Andrew Bolon to investigate, but before reaching the crime scene the chief of the Yakama intercepted him and warned Bolon that Mosheel was too dangerous to be taken in. Taking heed of this warning, Bolon decided to return to the Bureau to report his findings. He joined a traveling group of Yakama on his return trip, and while they walked he told them why he was in the area, about the unexplained murder that had happened. Unbeknownst to Bolon, the rest of the trip would be taken up by argument between the natives in a language he did not understand, as the leader of the group, Mosheel, argued for the murder of Bolon. Before he was stabbed in the throat, Bolon reportedly yelled in Chinook dialect, "I did not come to fight you!"