History Of Timekeeping Devices on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of timekeeping devices dates back to when

The history of timekeeping devices dates back to when

Ancient civilizations observed astronomical bodies, often the

Ancient civilizations observed astronomical bodies, often the

The first devices used for measuring the position of the Sun were shadow clocks, which later developed into the

The first devices used for measuring the position of the Sun were shadow clocks, which later developed into the

The

The

Incense clocks were first used in China around the 6th century, mainly for religious purposes, but also for social gatherings or by scholars. Due to their frequent use of

Incense clocks were first used in China around the 6th century, mainly for religious purposes, but also for social gatherings or by scholars. Due to their frequent use of

The 12th-century Muslim inventor

The 12th-century Muslim inventor

The invention of the verge and foliot escapement in 1275 was one of the most important inventions in both the history of the clock and the

The invention of the verge and foliot escapement in 1275 was one of the most important inventions in both the history of the clock and the

In 1715, at the age of 22,

In 1715, at the age of 22,

In 1815, the prolific English inventor

In 1815, the prolific English inventor

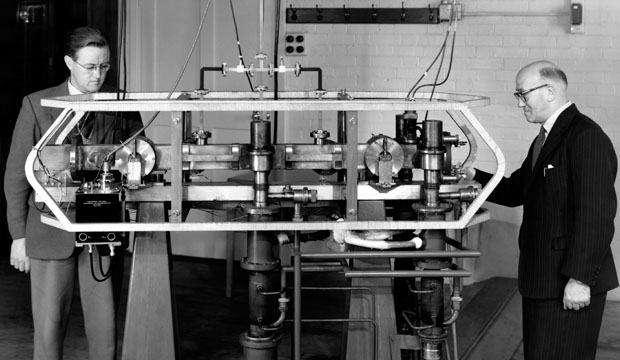

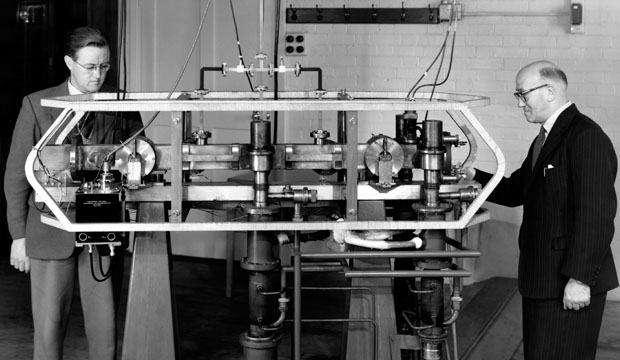

Atomic clocks are the most accurate timekeeping devices in practical use today. Accurate to within a few seconds over many thousands of years, they are used to calibrate other clocks and timekeeping instruments. The U.S. National Bureau of Standards (NBS, now National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)) changed the way it based the time standard of the United States from quartz to

Atomic clocks are the most accurate timekeeping devices in practical use today. Accurate to within a few seconds over many thousands of years, they are used to calibrate other clocks and timekeeping instruments. The U.S. National Bureau of Standards (NBS, now National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)) changed the way it based the time standard of the United States from quartz to

Relativity Science Calculator – Philosophic Question: are clocks and time separable?

Ancient Discoveries Islamic Science Part 4

clip from ''History Repeating'' of Islamic time-keeping inventions (YouTube). {{Time measurement and standards, state=collapsed History of measurement, Timekeeping devices History of technology, Timekeeping devices History of timekeeping, Timekeeping

The history of timekeeping devices dates back to when

The history of timekeeping devices dates back to when ancient civilization

A civilization (also spelled civilisation in British English) is any complex society characterized by the development of the state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond signed or spoken langua ...

s first observed astronomical bodies as they moved across the sky. Devices and methods for keeping time have gradually improved through a series of new inventions, starting with measuring time by continuous processes, such as the flow of liquid in water clocks, to mechanical clocks, and eventually repetitive, oscillatory

Oscillation is the repetitive or periodic variation, typically in time, of some measure about a central value (often a point of equilibrium) or between two or more different states. Familiar examples of oscillation include a swinging pendulum ...

processes, such as the swing of pendulum

A pendulum is a device made of a weight suspended from a pivot so that it can swing freely. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that will accelerate i ...

s. Oscillating timekeepers are used in modern timepieces.

Sundial

A sundial is a horology, horological device that tells the time of day (referred to as civil time in modern usage) when direct sunlight shines by the position of the Sun, apparent position of the Sun in the sky. In the narrowest sense of the ...

s and water clock

A water clock, or clepsydra (; ; ), is a timepiece by which time is measured by the regulated flow of liquid into (inflow type) or out from (outflow type) a vessel, and where the amount of liquid can then be measured.

Water clocks are some of ...

s were first used in ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

BC and later by the Babylonia

Babylonia (; , ) was an Ancient history, ancient Akkadian language, Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Kuwait, Syria and Iran). It emerged as a ...

ns, the Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

and the Chinese. Incense clocks were being used in China by the 6th century. In the medieval period, Islamic water clocks were unrivalled in their sophistication until the mid-14th century. The hourglass

An hourglass (or sandglass, sand timer, or sand clock) is a device used to measure the passage of time. It comprises two glass bulbs connected vertically by a narrow neck that allows a regulated flow of a substance (historically sand) from the ...

, invented in Europe, was one of the few reliable methods of measuring time at sea.

In medieval Europe, purely mechanical clocks were developed after the invention of the bell-striking alarm, used to signal the correct time to ring monastic

Monasticism (; ), also called monachism or monkhood, is a religious way of life in which one renounces worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual activities. Monastic life plays an important role in many Christian churches, especially ...

bells. The weight-driven mechanical clock controlled by the action of a verge and foliot was a synthesis of earlier ideas from European and Islamic science. Mechanical clocks were a major breakthrough, one notably designed and built by Henry de Vick in , which established basic clock design for the next 300 years. Minor developments were added, such as the invention of the mainspring

A mainspring is a spiral torsion spring of metal ribbon—commonly spring steel—used as a power source in mechanical watches, some clocks, and other clockwork mechanisms. ''Winding'' the timepiece, by turning a knob or key, stores energy in ...

in the early 15th century, which allowed small clocks to be built for the first time.

The next major improvement in clock building, from the 17th century, was the discovery that clocks could be controlled by harmonic oscillator

In classical mechanics, a harmonic oscillator is a system that, when displaced from its equilibrium position, experiences a restoring force ''F'' proportional to the displacement ''x'':

\vec F = -k \vec x,

where ''k'' is a positive const ...

s. Leonardo da Vinci had produced the earliest known drawings of a pendulum

A pendulum is a device made of a weight suspended from a pivot so that it can swing freely. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that will accelerate i ...

in 14931494, and in 1582 Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

had investigated the regular swing of the pendulum, discovering that frequency

Frequency is the number of occurrences of a repeating event per unit of time. Frequency is an important parameter used in science and engineering to specify the rate of oscillatory and vibratory phenomena, such as mechanical vibrations, audio ...

was only dependent on length, not weight. The pendulum clock

A pendulum clock is a clock that uses a pendulum, a swinging weight, as its timekeeping element. The advantage of a pendulum for timekeeping is that it is an approximate harmonic oscillator: It swings back and forth in a precise time interval dep ...

, designed and built by Dutch polymath Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Halen, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , ; ; also spelled Huyghens; ; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor who is regarded as a key figure in the Scientific Revolution ...

in 1656, was so much more accurate than other kinds of mechanical timekeepers that few verge and foliot mechanisms have survived. Other innovations in timekeeping during this period include inventions for striking clocks, the repeating clock and the deadbeat escapement.

Error factors in early pendulum clocks included temperature variation, a problem tackled during the 18th century by the English clockmakers John Harrison

John Harrison ( – 24 March 1776) was an English carpenter and clockmaker who invented the marine chronometer, a long-sought-after device for solving the History of longitude, problem of how to calculate longitude while at sea.

Harrison's sol ...

and George Graham. Following the Scilly naval disaster of 1707, after which governments offered a prize

A prize is an award to be given to a person or a group of people (such as sporting teams and organizations) to recognize and reward their actions and achievements.

to anyone who could discover a way to determine longitude, Harrison built a succession of accurate timepieces, introducing the term ''chronometer''. The electric clock, invented in 1840, was used to control the most accurate pendulum clocks until the 1940s, when quartz timers became the basis for the precise measurement of time and frequency.

The wristwatch

A watch is a timepiece carried or worn by a person. It is designed to maintain a consistent movement despite the motions caused by the person's activities. A wristwatch is worn around the wrist, attached by a watch strap or another type of ...

, which had been recognised as a valuable military tool during the Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic an ...

, became popular after World War I, in variations including non-magnetic, battery-driven, and solar powered, with quartz, transistors

A transistor is a semiconductor device used to Electronic amplifier, amplify or electronic switch, switch electrical signals and electric power, power. It is one of the basic building blocks of modern electronics. It is composed of semicondu ...

and plastic parts all introduced. Since the early 2010s, smartphone

A smartphone is a mobile phone with advanced computing capabilities. It typically has a touchscreen interface, allowing users to access a wide range of applications and services, such as web browsing, email, and social media, as well as multi ...

s and smartwatch

A smartwatch is a portable wearable computer that resembles a wristwatch. Most modern smartwatches are operated via a touchscreen, and rely on mobile apps that run on a connected device (such as a smartphone) in order to provide core functions. ...

es have become the most common timekeeping devices.

The most accurate timekeeping devices in practical use today are atomic clock

An atomic clock is a clock that measures time by monitoring the resonant frequency of atoms. It is based on atoms having different energy levels. Electron states in an atom are associated with different energy levels, and in transitions betwee ...

s, which can be accurate to a few billionths of a second per year and are used to calibrate other clocks and timekeeping instruments.

Continuous timekeeping devices

Ancient civilizations observed astronomical bodies, often the

Ancient civilizations observed astronomical bodies, often the Sun

The Sun is the star at the centre of the Solar System. It is a massive, nearly perfect sphere of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core, radiating the energy from its surface mainly as visible light a ...

and Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It Orbit of the Moon, orbits around Earth at Lunar distance, an average distance of (; about 30 times Earth diameter, Earth's diameter). The Moon rotation, rotates, with a rotation period (lunar ...

, to determine time. According to the historian Eric Bruton, Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a prehistoric Megalith, megalithic structure on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England, west of Amesbury. It consists of an outer ring of vertical sarsen standing stones, each around high, wide, and weighing around 25 tons, to ...

is likely to have been the Stone Age

The Stone Age was a broad prehistory, prehistoric period during which Rock (geology), stone was widely used to make stone tools with an edge, a point, or a percussion surface. The period lasted for roughly 3.4 million years and ended b ...

equivalent of an astronomical observatory

An observatory is a location used for observing terrestrial, marine, or celestial events. Astronomy, climatology/meteorology, geophysics, oceanography and volcanology are examples of disciplines for which observatories have been constructed.

Th ...

, used for seasonal and annual events such as equinox

A solar equinox is a moment in time when the Sun appears directly above the equator, rather than to its north or south. On the day of the equinox, the Sun appears to rise directly east and set directly west. This occurs twice each year, arou ...

es or solstice

A solstice is the time when the Sun reaches its most northerly or southerly sun path, excursion relative to the celestial equator on the celestial sphere. Two solstices occur annually, around 20–22 June and 20–22 December. In many countries ...

s. As megalith

A megalith is a large stone that has been used to construct a prehistoric structure or monument, either alone or together with other stones. More than 35,000 megalithic structures have been identified across Europe, ranging geographically f ...

ic civilizations left no recorded history, little is known of their timekeeping methods. The Warren Field calendar monument in Scotland is currently considered to be the oldest lunisolar calendar yet found.

Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area that begins in the southern part of North America and extends to the Pacific coast of Central America, thus comprising the lands of central and southern Mexico, all of Belize, Guatemala, El S ...

ns modified their usual vigesimal

A vigesimal ( ) or base-20 (base-score) numeral system is based on 20 (number), twenty (in the same way in which the decimal, decimal numeral system is based on 10 (number), ten). ''wikt:vigesimal#English, Vigesimal'' is derived from the Latin a ...

(base-20) counting system when dealing with calendar

A calendar is a system of organizing days. This is done by giving names to periods of time, typically days, weeks, months and years. A calendar date, date is the designation of a single and specific day within such a system. A calendar is ...

s to produce a 360-day year. Aboriginal Australians

Aboriginal Australians are the various indigenous peoples of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland and many of its islands, excluding the ethnically distinct people of the Torres Strait Islands.

Humans first migrated to Australia (co ...

understood the movement of objects in the sky well, and used their knowledge to construct calendars and aid navigation; most Aboriginal cultures had seasons that were well-defined and determined by natural changes throughout the year, including celestial events. Lunar phases

A lunar phase or Moon phase is the apparent shape of the Moon's directly sunlit portion as viewed from the Earth. Because the Moon is Tidal locking, tidally locked with the Earth, the same Hemisphere (geometry), hemisphere is always facing the ...

were used to mark shorter periods of time; the Yaraldi of South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a States and territories of Australia, state in the southern central part of Australia. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories by area, which in ...

being one of the few people recorded as having a way to measure time during the day, which was divided into seven parts using the position of the Sun.

All timekeepers before the 13th century relied upon methods that used something that moved continuously. No early method of keeping time changed at a steady rate. Devices and methods for keeping time have improved continuously through a long series of new inventions and ideas.

Shadow clocks and sundials

The first devices used for measuring the position of the Sun were shadow clocks, which later developed into the

The first devices used for measuring the position of the Sun were shadow clocks, which later developed into the sundial

A sundial is a horology, horological device that tells the time of day (referred to as civil time in modern usage) when direct sunlight shines by the position of the Sun, apparent position of the Sun in the sky. In the narrowest sense of the ...

. The oldest known sundial dates back to BC (during the 19th Dynasty), and was discovered in the Valley of the Kings

The Valley of the Kings, also known as the Valley of the Gates of the Kings, is an area in Egypt where, for a period of nearly 500 years from the Eighteenth Dynasty to the Twentieth Dynasty, rock-cut tombs were excavated for pharaohs and power ...

in 2013. Obelisks could indicate whether it was morning or afternoon, as well as the summer

Summer or summertime is the hottest and brightest of the four temperate seasons, occurring after spring and before autumn. At or centred on the summer solstice, daylight hours are the longest and darkness hours are the shortest, with day ...

and winter solstice

The winter solstice, or hibernal solstice, occurs when either of Earth's geographical pole, poles reaches its maximum axial tilt, tilt away from the Sun. This happens twice yearly, once in each hemisphere (Northern Hemisphere, Northern and So ...

s. A kind of shadow clock was developed BC that was similar in shape to a bent T-square

A T-square is a technical drawing instrument used by draftsmen primarily as a guide for drawing horizontal lines on a drafting table. The instrument is named after its resemblance to the letter T, with a long shaft called the "blade" and a s ...

. It measured the passage of time by the shadow cast by its crossbar, and was oriented eastward in the mornings, and turned around at noon, so it could cast its shadow in the opposite direction.

A sundial is referred to in the Bible, in 2 Kings 20:911, when Hezekiah

Hezekiah (; ), or Ezekias (born , sole ruler ), was the son of Ahaz and the thirteenth king of Kingdom of Judah, Judah according to the Hebrew Bible.Stephen L Harris, Harris, Stephen L., ''Understanding the Bible''. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985. "G ...

, king of Judea

Judea or Judaea (; ; , ; ) is a mountainous region of the Levant. Traditionally dominated by the city of Jerusalem, it is now part of Palestine and Israel. The name's usage is historic, having been used in antiquity and still into the pres ...

during the 8th century BC, is recorded as being healed by the prophet Isaiah

Isaiah ( or ; , ''Yəšaʿyāhū'', "Yahweh is salvation"; also known as Isaias or Esaias from ) was the 8th-century BC Israelite prophet after whom the Book of Isaiah is named.

The text of the Book of Isaiah refers to Isaiah as "the prophet" ...

and asks for a sign that he would recover:

A clay tablet

In the Ancient Near East, clay tablets (Akkadian language, Akkadian ) were used as a writing medium, especially for writing in cuneiform, throughout the Bronze Age and well into the Iron Age.

Cuneiform characters were imprinted on a wet clay t ...

from the late Babylonian period describes the lengths of shadows at different times of the year. The Babylonia

Babylonia (; , ) was an Ancient history, ancient Akkadian language, Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Kuwait, Syria and Iran). It emerged as a ...

n writer Berossos () is credited by the Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

with the invention of a hemispherical sundial hollowed out of stone; the path of the shadow was divided into 12 parts to mark the time. Greek sundials evolved to become highly sophisticated—Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

's ''Analemma'', written in the 2nd century AD, used an early form of trigonometry

Trigonometry () is a branch of mathematics concerned with relationships between angles and side lengths of triangles. In particular, the trigonometric functions relate the angles of a right triangle with ratios of its side lengths. The fiel ...

to derive the position of the Sun from data such as the hour of day and the geographical latitude

In geography, latitude is a geographic coordinate system, geographic coordinate that specifies the north-south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from −90° at t ...

.

The Romans inherited the sundial from the Greeks. The first sundial in Rome arrived in 264 BC, looted from Catania

Catania (, , , Sicilian and ) is the second-largest municipality on Sicily, after Palermo, both by area and by population. Despite being the second city of the island, Catania is the center of the most densely populated Sicilian conurbation, wh ...

in Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

. This sundial offered the innovation of the hours of the "horologium" throughout the day where before the Romans simply split the day into early morning and forenoon (''mane'' and ''ante merididiem).'' Still, there were unexpected astronomical challenges; this clock gave the incorrect time for a century. This mistake was noticed only in 164 BC, when the Roman censor came to check and adjusted for the appropriate latitude.

According to the German historian of astronomy Ernst Zinner, sundials were developed during the 13th century with scales that showed equal hours. The first based on polar time appeared in Germany ; an alternative theory proposes that a Damascus sundial measuring in polar time can be dated to 1372. European treatises on sundial design appeared .

An Egyptian method of determining the time during the night, used from at least 600 BC, was a type of plumb-line called a merkhet. A north–south meridian was created using two merkhets aligned with Polaris

Polaris is a star in the northern circumpolar constellation of Ursa Minor. It is designated α Ursae Minoris (Latinisation of names, Latinized to ''Alpha Ursae Minoris'') and is commonly called the North Star or Pole Star. With an ...

, the north pole star

A pole star is a visible star that is approximately aligned with the axis of rotation of an astronomical body; that is, a star whose apparent position is close to one of the celestial poles. On Earth, a pole star would lie directly overhead when ...

. The time was determined by observing particular stars as they crossed the meridian.

The Jantar Mantar in Jaipur

Jaipur (; , ) is the List of state and union territory capitals in India, capital and the List of cities and towns in Rajasthan, largest city of the north-western States and union territories of India, Indian state of Rajasthan. , the city had ...

built in 1727 by Jai Singh II includes the Vrihat Samrat Yantra, 88 feet (27 m) tall sundial

A sundial is a horology, horological device that tells the time of day (referred to as civil time in modern usage) when direct sunlight shines by the position of the Sun, apparent position of the Sun in the sky. In the narrowest sense of the ...

. It can tell local time to an accuracy of about two seconds.

Water clocks

The oldest description of a clepsydra, orwater clock

A water clock, or clepsydra (; ; ), is a timepiece by which time is measured by the regulated flow of liquid into (inflow type) or out from (outflow type) a vessel, and where the amount of liquid can then be measured.

Water clocks are some of ...

, is from the tomb inscription of an early 18th Dynasty

The Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt (notated Dynasty XVIII, alternatively 18th Dynasty or Dynasty 18) is classified as the first dynasty of the New Kingdom of Egypt, the era in which ancient Egypt achieved the peak of its power. The Eighteenth Dynasty ...

( BC) Egyptian court official named Amenemhet, who is identified as its inventor. It is assumed that the object described on the inscription is a bowl with markings to indicate the time. The oldest surviving water clock was found in the tomb of pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian language, Egyptian: ''wikt:pr ꜥꜣ, pr ꜥꜣ''; Meroitic language, Meroitic: 𐦲𐦤𐦧, ; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') was the title of the monarch of ancient Egypt from the First Dynasty of Egypt, First Dynasty ( ...

Amenhotep III ( 14171379 BC). There are no recognised examples in existence of outflowing water clocks from ancient Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

, but written references have survived.

The introduction of the water clock to China, perhaps from Mesopotamia, occurred as far back as the 2nd millennium BC, during the Shang dynasty

The Shang dynasty (), also known as the Yin dynasty (), was a Chinese royal dynasty that ruled in the Yellow River valley during the second millennium BC, traditionally succeeding the Xia dynasty and followed by the Western Zhou d ...

, and at the latest by the 1st millennium BC. Around 550 AD, Yin Kui (殷蘷) was the first in China to write of the overflow or constant-level tank in his book "Lou ke fa (漏刻法)". Around 610, two Sui dynasty

The Sui dynasty ( ) was a short-lived Dynasties of China, Chinese imperial dynasty that ruled from 581 to 618. The re-unification of China proper under the Sui brought the Northern and Southern dynasties era to a close, ending a prolonged peri ...

inventors, Geng Xun ( 耿詢) and Yuwen Kai ( 宇文愷), created the first balance clepsydra, with standard positions for the steelyard balance

A steelyard balance, steelyard, or stilyard is a straight-beam Weighing scale, balance with arms of unequal length. It incorporates a counterweight which slides along the longer arm to counterbalance the load and indicate its weight. A steelyard i ...

. In 721 the mathematician Yi Xing

Yixing (, 683–727) was a Buddhist monk of the Tang dynasty, recognized for his accomplishments as an astronomer, a reformer of the calendar system, a specialist in the ''I Ching, Yijing'' (易經), and a distinguished Buddhist figure with exp ...

and government official Liang Lingzan regulated the power of the water driving an astronomical clock

An astronomical clock, horologium, or orloj is a clock with special mechanisms and dials to display astronomical information, such as the relative positions of the Sun, Moon, zodiacal constellations, and sometimes major planets.

Definition ...

, dividing the power into unit impulses so that motion of the planets and stars could be duplicated. In 976, the Song dynasty

The Song dynasty ( ) was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 960 to 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song, who usurped the throne of the Later Zhou dynasty and went on to conquer the rest of the Fiv ...

astronomer Zhang Sixun addressed the problem of the water in clepsydrae freezing in cold weather when he replaced the water with liquid mercury. A water-powered astronomical clock tower was built by the polymath Su Song in 1088, which featured the first known endless power-transmitting chain drive

Chain drive is a way of transmitting mechanical power from one place to another. It is often used to convey power to the wheels of a vehicle, particularly bicycles and motorcycles. It is also used in a wide variety of machines besides vehicles.

...

.

The

The Greek philosophers

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC. Philosophy was used to make sense of the world using reason. It dealt with a wide variety of subjects, including astronomy, epistemology, mathematics, political philosophy, ethics, metaphysics ...

Anaxagoras

Anaxagoras (; , ''Anaxagóras'', 'lord of the assembly'; ) was a Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. Born in Clazomenae at a time when Asia Minor was under the control of the Persian Empire, Anaxagoras came to Athens. In later life he was charged ...

and Empedocles

Empedocles (; ; , 444–443 BC) was a Ancient Greece, Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is known best for originating the Cosmogony, cosmogonic theory of the four cla ...

both referred to water clocks that were used to enforce time limits or measure the passing of time. The Athenian

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

philosopher Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

is supposed to have invented an alarm clock

An alarm clock or alarm is a clock that is designed to alert an individual or group of people at a specified time. The primary function of these clocks is to awaken people from their night's sleep or short naps; they can sometimes be used for o ...

that used lead

Lead () is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol Pb (from Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a Heavy metal (elements), heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale, soft and Ductility, malleabl ...

balls cascading noisily onto a copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

platter to wake his students.

A problem with most clepsydrae was the variation in the flow of water due to the change in fluid pressure, which was addressed from 100 BC when the clock's water container was given a conical shape. They became more sophisticated when innovations such as gongs and moving mechanisms were included. There is strong evidence that the 1st century BC Tower of the Winds

The Tower of the Winds, known as the in Greek, and by #Names, other names, is an octagonal Pentelic marble tower in the Roman Agora in Athens, named after the eight large reliefs of wind gods around its top. Its date is uncertain, but was compl ...

in Athens once had a water clock, and a wind vane, as well as the nine vertical sundials still visible on the outside. In Greek tradition, clepsydrae were used in court

A court is an institution, often a government entity, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between Party (law), parties and Administration of justice, administer justice in Civil law (common law), civil, Criminal law, criminal, an ...

, a practise later adopted by the Ancient Romans

The Roman people was the ethnicity and the body of Roman citizenship, Roman citizens

(; ) during the Roman Kingdom, the Roman Republic, and the Roman Empire. This concept underwent considerable changes throughout the long history of the Roman ...

.

Ibn Khalaf al-Muradi

Ibn Khalaf al-Murādī, (; 11th century) was an Al-Andalus, Andalusian engineer.

Al-Murādī was the author of the technological manuscript entitled ''Kitāb al-asrār fī natā'ij al-afkār'' ('', The Book of Secrets in the Results of Thoughts ...

in medieval Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

described a water clock that employed both segmental and epicyclic gearing

An epicyclic gear train (also known as a planetary gearset) is a gear reduction assembly consisting of two gears mounted so that the center of one gear (the "planet") revolves around the center of the other (the "sun"). A carrier connects the ...

. Islamic water clocks, which used complex gear train

A gear train or gear set is a machine element of a mechanical system formed by mounting two or more gears on a frame such that the teeth of the gears engage.

Gear teeth are designed to ensure the pitch circles of engaging gears roll on each oth ...

s and included arrays of automata

An automaton (; : automata or automatons) is a relatively self-operating machine, or control mechanism designed to automatically follow a sequence of operations, or respond to predetermined instructions. Some automata, such as bellstrikers i ...

, were unrivalled in their sophistication until the mid-14th century. Liquid-driven mechanisms (using heavy floats and a constant-head system) were developed that enabled water clocks to work at a slower rate. Some have argued that the first known gear

A gear or gearwheel is a rotating machine part typically used to transmit rotational motion and/or torque by means of a series of teeth that engage with compatible teeth of another gear or other part. The teeth can be integral saliences or ...

ed clock was rather invented by the great mathematician, physicist, and engineer Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse ( ; ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Greek mathematics, mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and Invention, inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse, Sicily, Syracuse in History of Greek and Hellenis ...

during the 3rd century BC. Archimedes created his astronomical clock, which was also a cuckoo clock with birds singing and moving every hour. It is the first carillon clock as it plays music simultaneously with a person blinking his eyes, surprised by the singing birds. The Archimedes clock works with a system of four weights, counterweights, and strings regulated by a system of floats in a water container with siphons that regulate the automatic continuation of the clock. The principles of this type of clock are described by the mathematician and physicist Hero, who says that some of them work with a chain that turns a gear in the mechanism.

The 12th-century Jayrun Water Clock at the Umayyad Mosque

The Umayyad Mosque (; ), also known as the Great Mosque of Damascus, located in the old city of Damascus, the capital of Syria, is one of the largest and oldest mosques in the world. Its religious importance stems from the eschatological reports ...

in Damascus was constructed by Muhammad al-Sa'ati, and was later described by his son Ridwan ibn al-Sa'ati in his ''On the Construction of Clocks and their Use'' (1203). A sophisticated water-powered astronomical clock was described by Al-Jazari in his treatise on machines, written in 1206. This castle clock was about high. In 1235, a water-powered clock that "announced the appointed hours of prayer and the time both by day and by night" stood in the entrance hall of the Mustansiriya Madrasah in Baghdad

Baghdad ( or ; , ) is the capital and List of largest cities of Iraq, largest city of Iraq, located along the Tigris in the central part of the country. With a population exceeding 7 million, it ranks among the List of largest cities in the A ...

.

Chinese incense clocks

Incense clocks were first used in China around the 6th century, mainly for religious purposes, but also for social gatherings or by scholars. Due to their frequent use of

Incense clocks were first used in China around the 6th century, mainly for religious purposes, but also for social gatherings or by scholars. Due to their frequent use of Devanagari

Devanagari ( ; in script: , , ) is an Indic script used in the Indian subcontinent. It is a left-to-right abugida (a type of segmental Writing systems#Segmental systems: alphabets, writing system), based on the ancient ''Brāhmī script, Brā ...

characters, American sinologist

Sinology, also referred to as China studies, is a subfield of area studies or East Asian studies involved in social sciences and humanities research on China. It is an academic discipline that focuses on the study of the Chinese civilizatio ...

Edward H. Schafer has speculated that incense clocks were invented in India. As incense burns evenly and without a flame, the clocks were safe for indoor use. To mark different hours, differently scented incenses (made from different recipes) were used.

The incense sticks used could be straight or spiralled; the spiralled ones were intended for long periods of use, and often hung from the roofs of homes and temples. Some clocks were designed to drop weights at even intervals.

Incense seal clocks had a disk etched with one or more grooves, into which incense was placed. The length of the trail of incense, directly related to the size of the seal, was the primary factor in determining how long the clock would last; to burn 12 hours an incense path of around has been estimated. The gradual introduction of metal disks, most likely beginning during the Song dynasty, allowed craftsmen to more easily create seals of different sizes, design and decorate them more aesthetically, and vary the paths of the grooves, to allow for the changing length of the days in the year. As smaller seals became available, incense seal clocks grew in popularity and were often given as gifts.

Astrolabes

Sophisticated timekeepingastrolabe

An astrolabe (; ; ) is an astronomy, astronomical list of astronomical instruments, instrument dating to ancient times. It serves as a star chart and Model#Physical model, physical model of the visible celestial sphere, half-dome of the sky. It ...

s with geared mechanisms were made in Persia. Examples include those built by the polymath Abū Rayhān Bīrūnī in the 11th century and the astronomer Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr al‐Farisi

Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr al-Farisi (d. 1278/1279), an Iranian

in 1221. A brass

Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc, in proportions which can be varied to achieve different colours and mechanical, electrical, acoustic and chemical properties, but copper typically has the larger proportion, generally copper and zinc. I ...

and silver

Silver is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag () and atomic number 47. A soft, whitish-gray, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, and reflectivity of any metal. ...

astrolabe (which also acts as a calendar) made in Isfahan

Isfahan or Esfahan ( ) is a city in the Central District (Isfahan County), Central District of Isfahan County, Isfahan province, Iran. It is the capital of the province, the county, and the district. It is located south of Tehran. The city ...

by al‐Farisi is the earliest surviving machine with its gears still intact. Openings on the back of the astrolabe depict the lunar phase

A lunar phase or Moon phase is the apparent shape of the Moon's directly sunlit portion as viewed from the Earth. Because the Moon is tidally locked with the Earth, the same hemisphere is always facing the Earth. In common usage, the four maj ...

s and gives the Moon's age; within a zodiacal scale are two concentric rings that show the relative positions of the Sun and the Moon.

Muslim astronomers constructed a variety of highly accurate astronomical clocks for use in their mosques and observatories

An observatory is a location used for observing terrestrial, marine, or celestial events. Astronomy, climatology/meteorology, geophysics, oceanography and volcanology are examples of disciplines for which observatories have been constructed.

Th ...

, such as the astrolabic clock by Ibn al-Shatir in the early 14th century.

Candle clocks and hourglasses

One of the earliest references to a candle clock is in a Chinese poem, written in 520 by You Jianfu, who wrote of the graduated candle being a means of determining time at night. Similar candles were used in Japan until the early 10th century. The invention of the candle clock was attributed by theAnglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

to Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great ( ; – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who both died when Alfr ...

, king of Wessex

The Kingdom of the West Saxons, also known as the Kingdom of Wessex, was an Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy, kingdom in the south of Great Britain, from around 519 until Alfred the Great declared himself as King of the Anglo-Saxons in 886.

The Anglo-Sa ...

(r. 871–889), who used six candles marked at intervals of , each made from 12 pennyweight

A pennyweight (dwt) is a unit of mass equal to 24 grains, of a troy ounce, of a troy pound,

avoirdupois ounce and exactly 1.55517384 grams. It is abbreviated dwt, ''d'' standing for ''denarius'' (an ancient Roman coin), and later ...

s of wax, and made to be in height and of a uniform thickness.

The 12th-century Muslim inventor

The 12th-century Muslim inventor Al-Jazari

Badīʿ az-Zaman Abu l-ʿIzz ibn Ismāʿīl ibn ar-Razāz al-Jazarī (1136–1206, , ) was a Muslim polymath: a scholar, inventor, mechanical engineer, artisan and artist from the Artuqid Dynasty of Jazira in Mesopotamia. He is best known for ...

described four different designs for a candle clock in his book '' Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices''. His so-called "scribe" candle clock was invented to mark the passing of 14 hours of equal length: a precisely engineered mechanism caused a candle of specific dimensions to be slowly pushed upwards, which caused an indicator to move along a scale.

The hourglass

An hourglass (or sandglass, sand timer, or sand clock) is a device used to measure the passage of time. It comprises two glass bulbs connected vertically by a narrow neck that allows a regulated flow of a substance (historically sand) from the ...

was one of the few reliable methods of measuring time at sea, and it has been speculated that it was used on board ships as far back as the 11th century, when it would have complemented the compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself with No ...

as an aid to navigation. The earliest unambiguous evidence of the use an hourglass appears in the painting '' Allegory of Good Government'', by the Italian artist Ambrogio Lorenzetti

Ambrogio Lorenzetti (; – after 9 August 1348) was an Italian painter of the Sienese school. He was active from approximately 1317 to 1348. He painted ''The Allegory of Good and Bad Government'' in the Sala dei Nove (Salon of Nine or Council Ro ...

, from 1338.

The Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan

Ferdinand Magellan ( – 27 April 1521) was a Portuguese explorer best known for having planned and led the 1519–22 Spanish expedition to the East Indies. During this expedition, he also discovered the Strait of Magellan, allowing his fl ...

used 18 hourglasses on each ship during his circumnavigation of the globe in 1522. Though used in China, the hourglass's history there is unknown, but does not seem to have been used before the mid-16th century, as the hourglass implies the use of glassblowing

Glassblowing is a glassforming technique that involves inflating molten glass into a bubble (or parison) with the aid of a blowpipe (or blow tube). A person who blows glass is called a ''glassblower'', ''glassmith'', or ''gaffer''. A '' lampworke ...

, then an entirely European and Western art.

From the 15th century onwards, hourglasses were used in a wide range of applications at sea, in churches, in industry, and in cooking

Cooking, also known as cookery or professionally as the culinary arts, is the art, science and craft of using heat to make food more palatable, digestible, nutritious, or Food safety, safe. Cooking techniques and ingredients vary widely, from ...

; they were the first dependable, reusable, reasonably accurate, and easily constructed time-measurement devices. The hourglass took on symbolic meanings, such as that of death, temperance, opportunity, and Father Time

Father Time is a personification of time, in particular the progression of history and the approach of death. In recent centuries, he is usually depicted as an elderly bearded man, sometimes with wings, dressed in a robe and carrying a scythe ...

, usually represented as a bearded, old man.

History of early oscillating devices in timekeepers

The English word ''clock'' first appeared inMiddle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman Conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English pe ...

as , , or . The origin of the word is not known for certain; it may be a borrowing from French or Dutch, and can perhaps be traced to the post-classical Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

('bell'). 7th century Irish and 9th century Germanic sources recorded ''clock'' as meaning 'bell'.

Judaism, Christianity and Islam all had times set aside for prayer, although Christians alone were expected to attend prayers at specific hours of the day and night; what the historian Jo Ellen Barnett describes as "a rigid adherence to repetitive prayers said many times a day". The bell-striking alarms warned the monk

A monk (; from , ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a man who is a member of a religious order and lives in a monastery. A monk usually lives his life in prayer and contemplation. The concept is ancient and can be seen in many reli ...

on duty to toll the monastic

Monasticism (; ), also called monachism or monkhood, is a religious way of life in which one renounces worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual activities. Monastic life plays an important role in many Christian churches, especially ...

bell. His alarm was a timer that used a form of escapement

An escapement is a mechanical linkage in mechanical watches and clocks that gives impulses to the timekeeping element and periodically releases the gear train to move forward, advancing the clock's hands. The impulse action transfers energy to t ...

to ring a small bell. This mechanism was the forerunner of the escapement device found in the mechanical clock.

13th century

The first innovations to improve on the accuracy of the hourglass and the water clock occurred in the 10th century, when attempts were made to slow their rate of flow usingfriction

Friction is the force resisting the relative motion of solid surfaces, fluid layers, and material elements sliding against each other. Types of friction include dry, fluid, lubricated, skin, and internal -- an incomplete list. The study of t ...

or the force of gravity. The earliest depiction of a clock powered by a hanging weight is from the Bible of St Louis, an illuminated manuscript

An illuminated manuscript is a formally prepared manuscript, document where the text is decorated with flourishes such as marginalia, borders and Miniature (illuminated manuscript), miniature illustrations. Often used in the Roman Catholic Churc ...

made between 1226 and 1234 that shows a clock being slowed by water acting on a wheel. The illustration seems to show that weight-driven clocks were invented in western Europe. A treatise written by Robertus Anglicus in 1271 shows that medieval craftsmen were attempting to design a purely mechanical clock (i.e. only driven by gravity) during this period. Such clocks were a synthesis of earlier ideas derived from European and Islamic science, such as gearing systems, weight drives, and striking mechanisms.

In 1250, the artist Villard de Honnecourt illustrated a device that was the step towards the development of the escapement

An escapement is a mechanical linkage in mechanical watches and clocks that gives impulses to the timekeeping element and periodically releases the gear train to move forward, advancing the clock's hands. The impulse action transfers energy to t ...

. Another forerunner of the escapement was the , which used an early kind of verge mechanism to operate a knocker that continuously struck a bell. The weight-driven clock was probably a Western European invention, as a picture of a clock shows a weight pulling an axle around, its motion slowed by a system of holes that slowly released water. In 1271, the English astronomer Robertus Anglicus wrote of his contemporaries that they were in the process of developing a form of mechanical clock.

14th century

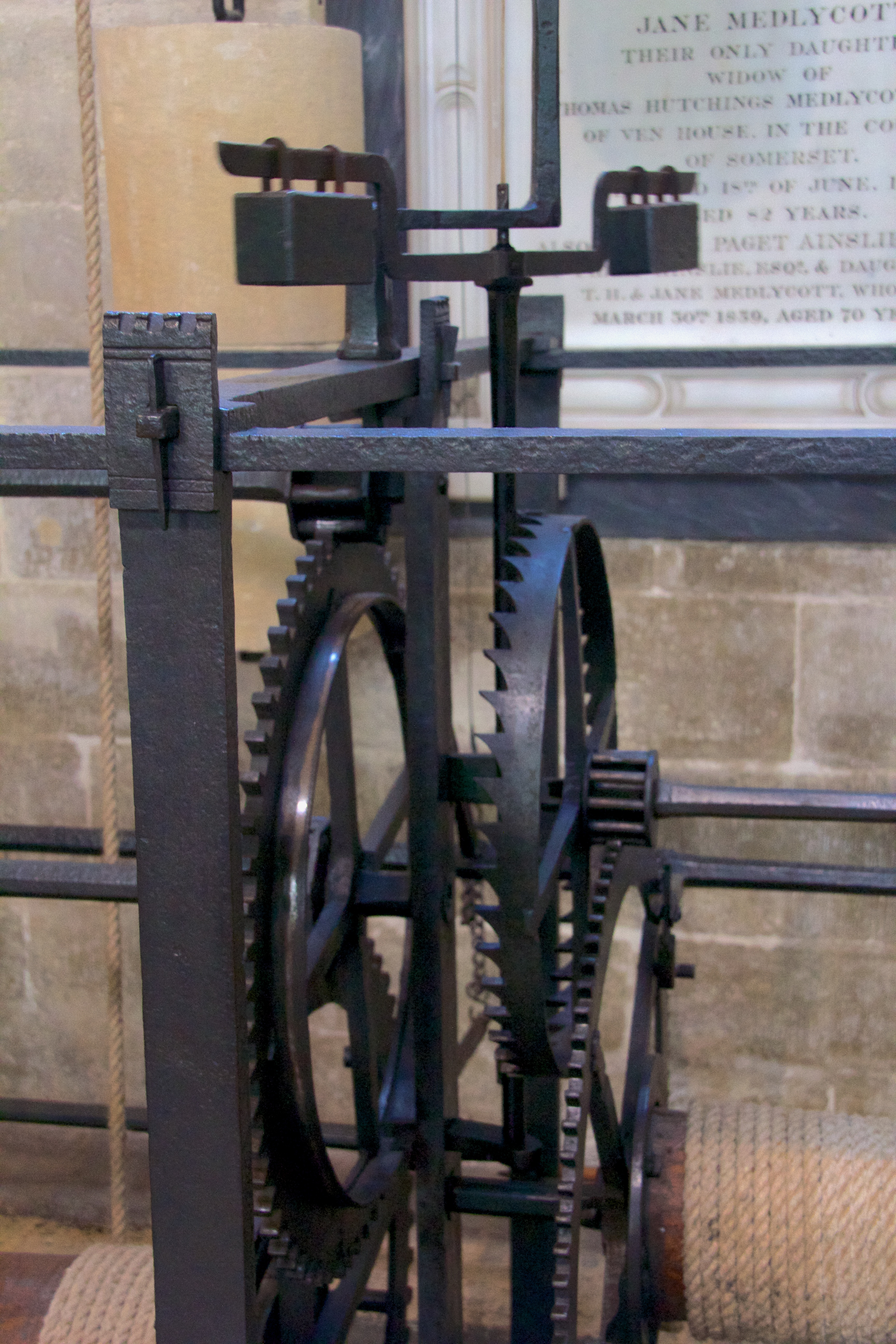

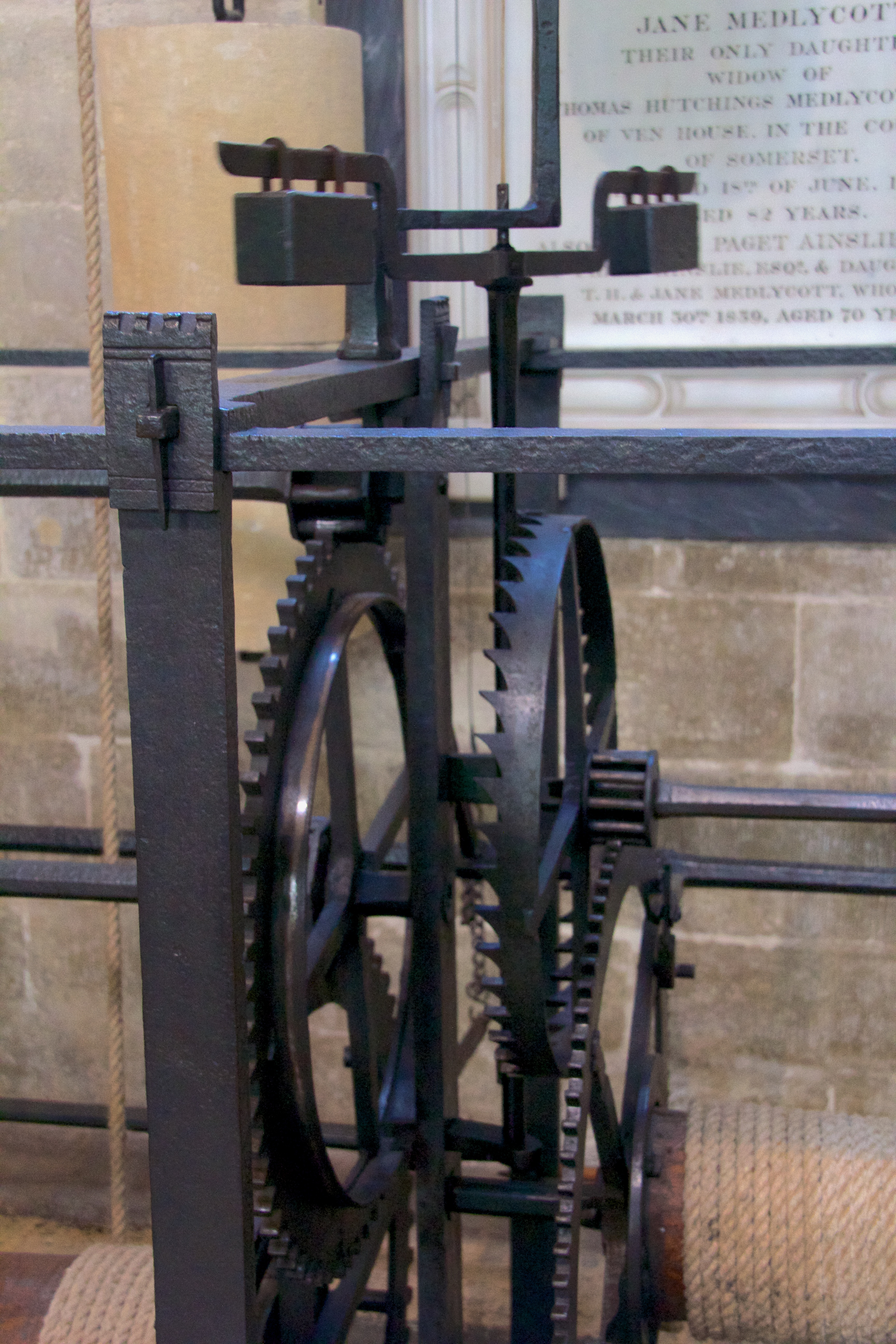

The invention of the verge and foliot escapement in 1275 was one of the most important inventions in both the history of the clock and the

The invention of the verge and foliot escapement in 1275 was one of the most important inventions in both the history of the clock and the history of technology

The history of technology is the history of the invention of tools and techniques by humans. Technology includes methods ranging from simple stone tools to the complex genetic engineering and information technology that has emerged since the 19 ...

. It was the first type of regulator in horology

Chronometry or horology () is the science studying the measurement of time and timekeeping. Chronometry enables the establishment of standard measurements of time, which have applications in a broad range of social and scientific areas. ''Hor ...

. A verge, or vertical shaft, is forced to rotate by a weight-driven crown wheel, but is stopped from rotating freely by a foliot. The foliot, which cannot vibrate freely, swings back and forth, which allows a wheel to rotate one tooth at a time. Although the verge and foliot was an advancement on previous timekeepers, it was impossible to avoid fluctuations in the beat caused by changes in the applied forces—the earliest mechanical clocks were regularly reset using a sundial.

At around the same time as the invention of the escapement, the Florentine poet Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

used clock imagery to depict the souls of the blessed in '' Paradiso'', the third part of the ''Divine Comedy

The ''Divine Comedy'' (, ) is an Italian narrative poetry, narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun and completed around 1321, shortly before the author's death. It is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature and one of ...

'', written in the early part of the 14th century. It may be the first known literary description of a mechanical clock. There are references to house clocks from 1314 onwards; by 1325 the development of the mechanical clock can be assumed to have occurred.

Large mechanical clocks were built that were mounted in towers so as to ring the bell directly. The tower clock of Norwich Cathedral constructed 1273 (reference to a payment for a mechanical clock dated to this year) is the earliest such large clock known. The clock has not survived. The first clock known to strike regularly on the hour, a clock with a verge and foliot mechanism, is recorded in Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

in 1336. By 1341, clocks driven by weights were familiar enough to be able to be adapted for grain mills, and by 1344 the clock in London's Old St Paul's Cathedral

Old St Paul's Cathedral was the cathedral of the City of London that, until the Great Fire of London, Great Fire of 1666, stood on the site of the present St Paul's Cathedral. Built from 1087 to 1314 and dedicated to Paul of Tarsus, Saint Paul ...

had been replaced by one with an escapement. The foliot was first illustrated by Dondi in 1364, and mentioned by the court historian Jean Froissart

Jean Froissart ( Old and Middle French: ''Jehan''; sometimes known as John Froissart in English; – ) was a French-speaking medieval author and court historian from the Low Countries who wrote several works, including ''Chronicles'' and ''Meli ...

in 1369.

The most famous example of a timekeeping device during the medieval period was a clock designed and built by the clockmaker Henry de Vick 1360, which was said to have varied by up to two hours a day. For the next 300 years, all the improvements in timekeeping were essentially developments based on the principles of de Vick's clock. Between 1348 and 1364, Giovanni Dondi dell'Orologio, the son of Jacopo Dondi, built a complex astrarium

An astrarium, also called a planetarium, is a medieval astronomical clock made in the 14th century by Italian engineer and astronomer Giovanni Dondi dell'Orologio. The Astrarium was modeled after the Solar System and, in addition to counting tim ...

in Florence.

During the 14th century, striking clocks appeared with increasing frequency in public spaces, first in Italy, slightly later in France and England—between 1371 and 1380, public clocks were introduced in over 70 European cites. Salisbury Cathedral clock, dating from about 1386, is one of the oldest working clocks in the world, and may be the oldest; it still has most of its original parts. The Wells Cathedral clock

The Wells Cathedral clock is an astronomical clock in the north transept of Wells Cathedral, England. The clock is one of the group of famous 14th– to 16th–century astronomical clocks to be found in the West of England. The surviving mechani ...

, built in 1392, is unique in that it still has its original medieval face. Above the clock are figures which hit the bells, and a set of jousting knights who revolve around a track every 15 minutes.

Later developments

The invention of themainspring

A mainspring is a spiral torsion spring of metal ribbon—commonly spring steel—used as a power source in mechanical watches, some clocks, and other clockwork mechanisms. ''Winding'' the timepiece, by turning a knob or key, stores energy in ...

in the early 15th century—a device first used in locks and for flintlocks in guns— allowed small clocks to be built for the first time. The need for an escapement mechanism that steadily controlled the release of the stored energy, led to the development of two devices, the stackfreed (which although invented in the 15th century can be documented no earlier than 1535) and the fusee, which first originated from medieval weapons such as the crossbow

A crossbow is a ranged weapon using an Elasticity (physics), elastic launching device consisting of a Bow and arrow, bow-like assembly called a ''prod'', mounted horizontally on a main frame called a ''tiller'', which is hand-held in a similar f ...

. There is a fusee in the earliest surviving spring-driven clock, a chamber clock made for Philip the Good

Philip III the Good (; ; 31 July 1396 – 15 June 1467) ruled as Duke of Burgundy from 1419 until his death in 1467. He was a member of a cadet line of the Valois dynasty, to which all 15th-century kings of France belonged. During his reign, ...

in 1430. Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 1452 - 2 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially rested o ...

, who produced the earliest known drawings of a pendulum in 14931494, illustrated a fusee in 1500, a quarter of a century after the coiled spring first appeared.

Clock towers in Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

in the Middle Ages struck the time. Early clock dials showed hours; a clock with a minutes dial is mentioned in a 1475 manuscript. During the 16th century, timekeepers became more refined and sophisticated, so that by 1577 the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe ( ; ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe, ; 14 December 154624 October 1601), generally called Tycho for short, was a Danish astronomer of the Renaissance, known for his comprehensive and unprecedentedly accurate astronomical observations. He ...

was able to obtain the first of four clocks that measured in seconds, and in Nuremberg, the German clockmaker Peter Henlein

Peter Henlein (also spelled Henle or Hele) (1485 - August 1542), a locksmith, clockmaker, and watchmaker of Nuremberg, Germany. Due to the Fire-gilded pomander-shaped Watch 1505, watch from 1505, he is often considered the inventor of the pocket ...

was paid for making what is thought to have been the earliest example of a watch

A watch is a timepiece carried or worn by a person. It is designed to maintain a consistent movement despite the motions caused by the person's activities. A wristwatch is worn around the wrist, attached by a watch strap or another type of ...

, made in 1524. By 1500, the use of the foliot in clocks had begun to decline. The oldest surviving spring-driven clock is a device made by Bohemian in 1525. The first person to suggest travelling with a clock to determine longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east- west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek lett ...

, in 1530, was the Dutch instrument maker Gemma Frisius

Gemma Frisius (; born Jemme Reinerszoon; December 9, 1508 – May 25, 1555) was a Dutch physician, mathematician, cartographer, philosopher, and instrument maker. He created important globes, improved the mathematical instruments of his day ...

. The clock would be set to the local time of a starting point whose longitude was known, and the longitude of any other place could be determined by comparing its local time with the clock time.

The Ottoman engineer Taqi ad-Din described a weight-driven clock with a verge-and-foliot escapement, a striking train of gears, an alarm, and a representation of the Moon's phases in his book ''The Brightest Stars for the Construction of Mechanical Clocks'' (), written around 1565. Jesuit missionaries brought the first European clocks to China as gifts.

The Italian polymath

A polymath or polyhistor is an individual whose knowledge spans many different subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems. Polymaths often prefer a specific context in which to explain their knowledge, ...

Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

is thought to have first realized that the pendulum could be used as an accurate timekeeper after watching the motion of suspended lamps at Pisa Cathedral

Pisa Cathedral (), officially the Primatial Metropolitan Cathedral of the Assumption of Mary (), is a medieval Catholic cathedral dedicated to the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, in the Piazza dei Miracoli in Pisa, Italy, the oldest of the three s ...

. In 1582, he investigated the regular swing of the pendulum

A pendulum is a device made of a weight suspended from a pivot so that it can swing freely. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that will accelerate i ...

, and discovered that this was only dependent on its length. Galileo never constructed a clock based on his discovery, but prior to his death he dictated instructions for building a pendulum clock to his son, Vincenzo.

Era of precision timekeeping

Pendulum clocks

The first accurate timekeepers depended on the phenomenon known as harmonic motion, in which the restoring force acting on an object moved away from itsequilibrium

Equilibrium may refer to:

Film and television

* ''Equilibrium'' (film), a 2002 science fiction film

* '' The Story of Three Loves'', also known as ''Equilibrium'', a 1953 romantic anthology film

* "Equilibrium" (''seaQuest 2032'')

* ''Equilibr ...

position—such as a pendulum or an extended spring—acts to return the object to that position, and causes it to oscillate

Oscillation is the repetitive or periodic variation, typically in time, of some measure about a central value (often a point of equilibrium) or between two or more different states. Familiar examples of oscillation include a swinging pendulu ...

. Harmonic oscillators can be used as accurate timekeepers as the period of oscillation does not depend on the amplitude of the motion—and so it always takes the same time to complete one oscillation. The period of a harmonic oscillator is completely dependent on the physical characteristics of the oscillating system and not the starting conditions or the amplitude

The amplitude of a periodic variable is a measure of its change in a single period (such as time or spatial period). The amplitude of a non-periodic signal is its magnitude compared with a reference value. There are various definitions of am ...

.

The period when clocks were controlled by harmonic oscillator

In classical mechanics, a harmonic oscillator is a system that, when displaced from its equilibrium position, experiences a restoring force ''F'' proportional to the displacement ''x'':

\vec F = -k \vec x,

where ''k'' is a positive const ...

s was the most productive era in timekeeping. The first invention of this type was the pendulum clock

A pendulum clock is a clock that uses a pendulum, a swinging weight, as its timekeeping element. The advantage of a pendulum for timekeeping is that it is an approximate harmonic oscillator: It swings back and forth in a precise time interval dep ...

, which was designed and built by Dutch polymath Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Halen, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , ; ; also spelled Huyghens; ; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor who is regarded as a key figure in the Scientific Revolution ...

in 1656. Early versions erred by less than one minute per day, and later ones only by 10 seconds, very accurate for their time. Dials that showed minutes and seconds became common after the increase in accuracy made possible by the pendulum clock. Brahe used clocks with minutes and seconds to observe stellar positions. The pendulum clock outperformed all other kinds of mechanical timekeepers to such an extent that these were usually refitted with a pendulum—a task that could be done without difficulty—so that few verge escapement devices have survived in their original form.

The first pendulum clocks used a verge escapement, which required wide swings of about 100° and so had short, light pendulums. The swing was reduced to around 6° after the invention of the anchor mechanism enabled the use of longer, heavier pendulums with slower beats that had less variation, as they more closely resembled simple harmonic motion, required less power, and caused less friction and wear. The first known anchor escapement clock was built by the English clockmaker William Clement in 1671 for King's College, Cambridge, now in the Science Museum, London

The Science Museum is a major museum on Exhibition Road in South Kensington, London. It was founded in 1857 and is one of the city's major tourist attractions, attracting 3.3 million visitors annually in 2019.

Like other publicly funded ...

. The anchor escapement originated with Hooke, although it has been argued that it was invented by Clement, or the English clockmaker Joseph Knibb.

The Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

s made major contributions to the development of pendulum clocks in the 17th and 18th centuries, having had an "unusually keen appreciation of the importance of precision". In measuring an accurate one-second pendulum, for example, the Italian astronomer Father Giovanni Battista Riccioli

Giovanni Battista Riccioli (17 April 1598 – 25 June 1671) was an Italian astronomer and a Catholic priest in the Jesuit order. He is known, among other things, for his experiments with pendulums and with falling bodies, for his discussion of ...

persuaded nine fellow Jesuits "to count nearly 87,000 oscillations in a single day". They served a crucial role in spreading and testing the scientific ideas of the period, and collaborated with Huygens and his contemporaries.

Huygens first used a clock to calculate the equation of time

The equation of time describes the discrepancy between two kinds of solar time. The two times that differ are the apparent solar time, which directly tracks the diurnal motion of the Sun, and mean solar time, which tracks a theoretical mean Sun ...

(the difference between the apparent solar time and the time given by a clock), publishing his results in 1665. The relationship enabled astronomers to use the stars to measure sidereal time

Sidereal time ("sidereal" pronounced ) is a system of timekeeping used especially by astronomers. Using sidereal time and the celestial coordinate system, it is easy to locate the positions of celestial objects in the night sky. Sidereal t ...

, which provided an accurate method for setting clocks. The equation of time was engraved on sundials so that clocks could be set using the Sun. In 1720, Joseph Williamson claimed to have invented a clock that showed solar time, fitted with a cam

Cam or CAM may refer to:

Science and technology

* Cam (mechanism), a mechanical linkage which translates motion

* Camshaft, a shaft with a cam

* Camera or webcam, a device that records images or video

In computing

* Computer-aided manufacturin ...

and differential gearing, so that the clock indicated true solar time.

Other innovations in timekeeping during this period include the invention of the rack and snail striking mechanism for striking clocks by the English mechanician

A mechanician is an engineer or a scientist working in the field of mechanics, or in a related or sub-field: engineering or computational mechanics, applied mechanics, geomechanics, biomechanics, and mechanics of materials. Names other than m ...

Edward Barlow, the invention by either Barlow or Daniel Quare

Daniel Quare (1648 or 1649 – 21 March 1724) was an English clockmaker and instrument maker who invented a repeating watch movement in 1680 and a portable barometer in 1695.

Early life

Daniel Quare's origins are obscure. He was possibly a nat ...

, a London clock-maker, in 1676 of the repeating clock that chimes the number of hours or minutes, and the deadbeat escapement, invented around 1675 by the astronomer Richard Towneley.

Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

and Blois

Blois ( ; ) is a commune and the capital city of Loir-et-Cher Departments of France, department, in Centre-Val de Loire, France, on the banks of the lower Loire river between Orléans and Tours.

With 45,898 inhabitants by 2019, Blois is the mos ...

were the early centres of clockmaking in France, and French clockmakers such as Julien Le Roy, clockmaker of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; ) is a former royal residence commissioned by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, about west of Paris, in the Yvelines, Yvelines Department of Île-de-France, Île-de-France region in Franc ...

, were leaders in case design and ornamental clocks. Le Roy belonged to the fifth generation of a family of clockmakers, and was described by his contemporaries as "the most skillful clockmaker in France, possibly in Europe". He invented a special repeating mechanism which improved the precision of clocks and watches, a face that could be opened to view the inside clockwork, and made or supervised over 3,500 watches during his career of almost five decades, which ended with his death in 1759. The competition and scientific rivalry resulting from his discoveries further encouraged researchers to seek new methods of measuring time more accurately.

Any inherent errors in early pendulum clocks were smaller than other errors caused by factors such as temperature variation. In 1729 the Yorkshire carpenter and self-taught clockmaker John Harrison

John Harrison ( – 24 March 1776) was an English carpenter and clockmaker who invented the marine chronometer, a long-sought-after device for solving the History of longitude, problem of how to calculate longitude while at sea.

Harrison's sol ...

invented the gridiron pendulum, which used at least three metals of different lengths and expansion properties, connected so as to maintain the overall length of the pendulum when it is heated or cooled by its surroundings. In 1721 the clockmaker George Graham had compensated for temperature variation in an iron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's o ...

pendulum by using a bob made from a glass jar of mercury—a liquid metal at room temperature

Room temperature, colloquially, denotes the range of air temperatures most people find comfortable indoors while dressed in typical clothing. Comfortable temperatures can be extended beyond this range depending on humidity, air circulation, and ...

that expands faster than glass. More accurate versions of this innovation contained the mercury in thinner iron jars to make them more responsive. This type of temperature compensating pendulum was improved still further when the mercury was contained within the rod itself, which allowed the two metals to be thermally coupled more tightly. In 1895, the invention of invar

Invar, also known generically as FeNi36 (64FeNi in the US), is a nickel–iron alloy notable for its uniquely low coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE or α). The name ''Invar'' comes from the word ''invariable'', referring to its relative lac ...

, an alloy

An alloy is a mixture of chemical elements of which in most cases at least one is a metal, metallic element, although it is also sometimes used for mixtures of elements; herein only metallic alloys are described. Metallic alloys often have prop ...

made from iron and nickel

Nickel is a chemical element; it has symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive, but large pieces are slo ...

that expands very little, largely eliminated the need for earlier inventions designed to compensate for the variation in temperature.

Between 1794 and 1795, in the aftermath of the French Revolution, the French government mandated the use of decimal time

Decimal time is the representation of the time of day using units which are decimally related. This term is often used specifically to refer to the French Republican calendar time system used in #France, France from 1794 to 1800, during the Fre ...

, with a day divided into 10 hours of 100 minutes each. A clock in the Palais des Tuileries

The Tuileries Palace (, ) was a palace in Paris which stood on the right bank of the Seine, directly in the west-front of the Louvre Palace. It was the Parisian residence of most French monarchs, from Henri IV to Napoleon III, until it was ...

kept decimal time as late as 1801.

Marine chronometer

After the Scilly naval disaster of 1707, in which four ships were wrecked as a result of navigational mistakes, the British government offered aprize

A prize is an award to be given to a person or a group of people (such as sporting teams and organizations) to recognize and reward their actions and achievements.

of £20,000, equivalent to millions of pounds today, for anyone who could determine the longitude to within at a latitude just north of the equator. The position of a ship at sea could be determined to within if a navigator could refer to a clock that lost or gained less than about six seconds per day. Proposals were examined by a newly created Board of Longitude

Board or Boards may refer to:

Flat surface

* Lumber, or other rigid material, milled or sawn flat

** Plank (wood)

** Cutting board

** Sounding board, of a musical instrument

* Cardboard (paper product)

* Paperboard

* Fiberboard

** Hardboard ...

. Among the many people who attempted to claim the prize was the Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ) is an area of Northern England which was History of Yorkshire, historically a county. Despite no longer being used for administration, Yorkshire retains a strong regional identity. The county was named after its county town, the ...

clockmaker Jeremy Thacker, who first used the term '' chronometer'' in a pamphlet

A pamphlet is an unbound book (that is, without a Hardcover, hard cover or Bookbinding, binding). Pamphlets may consist of a single sheet of paper that is printed on both sides and folded in half, in thirds, or in fourths, called a ''leaflet'' ...

published in 1714. Huygens built the first sea clock, designed to remain horizontal aboard a moving ship, but that stopped working if the ship moved suddenly.

In 1715, at the age of 22,

In 1715, at the age of 22, John Harrison

John Harrison ( – 24 March 1776) was an English carpenter and clockmaker who invented the marine chronometer, a long-sought-after device for solving the History of longitude, problem of how to calculate longitude while at sea.

Harrison's sol ...

had used his carpentry skills to construct a wooden eight-day clock. His clocks had innovations that included the use of wooden parts to remove the need for additional lubrication (and cleaning), rollers to reduce friction, a new kind of escapement, and the use of two different metals to reduce the problem of expansion caused by temperature variation.

He travelled to London to seek assistance from the Board of Longitude in making a sea clock. He was sent to visit Graham, who assisted Harrison by arranging to finance his work to build a clock. After 30 years, his device, now named "H1" was built and in 1736 it was tested at sea. Harrison then went on to design and make two other sea clocks, "H2" (completed in around 1739) and "H3", both of which were ready by 1755.