History Of Early Ottoman Bulgaria on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of Ottoman Bulgaria spans nearly 500 years, beginning in the late 14th century, with the Ottoman conquest of smaller kingdoms from the disintegrating

The Ottomans reorganised the Bulgarian territories, dividing them into several

The Ottomans reorganised the Bulgarian territories, dividing them into several

The Ottoman Empire's greatest advantage compared to other colonial powers, the

The Ottoman Empire's greatest advantage compared to other colonial powers, the

While the Ottomans were ascendant, there was overt opposition to their rule. The first revolt began at the time

While the Ottomans were ascendant, there was overt opposition to their rule. The first revolt began at the time

The Bulgarian National Revival was a period of socio-economic development and national integration among

The Bulgarian National Revival was a period of socio-economic development and national integration among

The

The

The division of Muslims into "Established" and "Muhacir" in the 1873-1874 Census and the 1875 Ottoman Salname was not based on origin, as the name might suggest, but on "taxability". Thus, colonists whose tax exemption had expired and were liable to taxation (i.e., those of them who had settled prior to 1862—Crimean Tatars, Nogais, etc. and a minority of Circassians) were counted as "Established", while colonists who still benefited from a tax exemption (as a rule, Circassians arriving in 1864 or later) were regarded as "Muhacir". Contemporary European geographers, such as German-English In the words of Nusret Pasha, Head of the Silistra Eylaet Colonisation Commission himself, to

In the words of Nusret Pasha, Head of the Silistra Eylaet Colonisation Commission himself, to

File:Lescostumespopul00osma.pdf, page=79, Bulgarian man and woman of

Second Bulgarian Empire

The Second Bulgarian Empire (; ) was a medieval Bulgarians, Bulgarian state that existed between 1185 and 1422. A successor to the First Bulgarian Empire, it reached the peak of its power under Tsars Kaloyan of Bulgaria, Kaloyan and Ivan Asen II ...

. In the late 19th century, Bulgaria was liberated from the Ottoman Empire, and by the early 20th century it was declared independent.

The brutal suppression of the Bulgarian April Uprising of 1876

The April Uprising () was an insurrection organised by the Bulgarians in the Ottoman Empire from April to May 1876. The rebellion was suppressed by irregular military, irregular Ottoman bashi-bazouk units that engaged in indiscriminate slaught ...

and the public outcry it caused across Europe led to the Constantinople Conference

The 1876–77 Constantinople Conference ( "Shipyard Conference", after the venue ''Tersane Sarayı'' "Shipyard Palace") of the Great Powers (Austria-Hungary, Britain, France, Germany, Italy and Russia) was held in Constantinople (now Istanbul) f ...

, where the Great Powers

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power ...

tabled a joint proposal for the creation of two autonomous Bulgarian vilayets, largely corresponding to the ethnic boundaries drawn a decade earlier with the establishment of the Bulgarian Exarchate

The Bulgarian Exarchate (; ) was the official name of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church before its autocephaly was recognized by the Ecumenical See in 1945 and the Bulgarian Patriarchate was restored in 1953.

The Exarchate (a de facto autocephaly) ...

.

The sabotage of the Conference, by either the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

or the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

(depending on theory), led to the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878)

The Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) was a conflict between the Ottoman Empire and a coalition led by the Russian Empire which included United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, Romania, Principality of Serbia, Serbia, and Principality of ...

, whereby the much smaller Principality of Bulgaria

The Principality of Bulgaria () was a vassal state under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire. It was established by the Treaty of Berlin in 1878.

After the Russo-Turkish War ended with a Russian victory, the Treaty of San Stefano was signed ...

, a self-governing, but functionally independent Ottoman vassal state was created. In 1885 the Ottoman autonomous province of Eastern Rumelia

Eastern Rumelia (; ; ) was an autonomous province (''oblast'' in Bulgarian, ''vilayet'' in Turkish) of the Ottoman Empire with a total area of , which was created in 1878 by virtue of the Treaty of Berlin (1878), Treaty of Berlin and ''de facto'' ...

unified through a bloodless coup with the Principality of Bulgaria

The Principality of Bulgaria () was a vassal state under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire. It was established by the Treaty of Berlin in 1878.

After the Russo-Turkish War ended with a Russian victory, the Treaty of San Stefano was signed ...

.

Administrative organization

The Ottomans reorganised the Bulgarian territories, dividing them into several

The Ottomans reorganised the Bulgarian territories, dividing them into several vilayet

A vilayet (, "province"), also known by #Names, various other names, was a first-order administrative division of the later Ottoman Empire. It was introduced in the Vilayet Law of 21 January 1867, part of the Tanzimat reform movement initiated b ...

s, each ruled by a Sanjakbey or Subasi accountable to the Beylerbey

''Beylerbey'' (, meaning the 'commander of commanders' or 'lord of lords’, sometimes rendered governor-general) was a high rank in the western Islamic world in the late Middle Ages and early modern period, from the Anatolian Seljuks and the I ...

. Significant parts of the conquered land were parcelled out to the Sultan

Sultan (; ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it came to be use ...

's followers, who held it as benefices or fiefs (small ''timar

A timar was a land grant by the sultans of the Ottoman Empire between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries, with an annual tax revenue of less than 20,000 akçes. The revenues produced from the land acted as compensation for military service. A ...

'', medium ''zeamet

Ziamet was a form of land tenure in the Ottoman Empire, consisting in grant of lands or revenues by the Ottoman Sultan to an individual in compensation for their services, especially military services. The ziamet system was introduced by Osman I, ...

'' and large '' hass'') directly from him, or from the Beylerbeys.C. M. Woodhouse, ''Modern Greece: A Short History'', p. 101.

This category of land could not be sold or inherited but reverted to the Sultan when the fiefholder died. The lands were organised as private possessions of the Sultan or Ottoman nobility, called "mülk", and also as an economic base for religious foundations, called vakιf, as well as other people. The system was meant to make the army self-sufficient and to continuously increase the number of Ottoman cavalry soldiers, thus both fuelling new conquests and bringing conquered countries under direct Ottoman control.

From the 14th century until the 19th century Sofia

Sofia is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Bulgaria, largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain, in the western part of the country. The city is built west of the Is ...

was an important administrative centre in the Ottoman Empire. It became the capital of the beylerbey

''Beylerbey'' (, meaning the 'commander of commanders' or 'lord of lords’, sometimes rendered governor-general) was a high rank in the western Islamic world in the late Middle Ages and early modern period, from the Anatolian Seljuks and the I ...

lik of Rumelia

Rumelia (; ; ) was a historical region in Southeastern Europe that was administered by the Ottoman Empire, roughly corresponding to the Balkans. In its wider sense, it was used to refer to all Ottoman possessions and Vassal state, vassals in E ...

(Rumelia Eyalet

The Eyalet of Rumeli, or Eyalet of Rumelia (), known as the Beylerbeylik of Rumeli until 1591, was a first-level province ('' beylerbeylik'' or ''eyalet'') of the Ottoman Empire encompassing most of the Balkans ("Rumelia"). For most of its history ...

), the province

A province is an administrative division within a country or sovereign state, state. The term derives from the ancient Roman , which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire, Roman Empire's territorial possessions ou ...

that administered the Ottoman lands in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

(the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

), one of the two together with the beylerbeylik of Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

. It was the capital of the important Sanjak of Sofia as well, including the whole of Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

with Plovdiv

Plovdiv (, ) is the List of cities and towns in Bulgaria, second-largest city in Bulgaria, 144 km (93 miles) southeast of the capital Sofia. It had a population of 490,983 and 675,000 in the greater metropolitan area. Plovdiv is a cultural hub ...

and Edirne

Edirne (; ), historically known as Orestias, Adrianople, is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the Edirne Province, province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian borders, Edirne was the second c ...

, and part of Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

with Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

and Skopje

Skopje ( , ; ; , sq-definite, Shkupi) is the capital and largest city of North Macedonia. It lies in the northern part of the country, in the Skopje Basin, Skopje Valley along the Vardar River, and is the political, economic, and cultura ...

.

The Danube Vilayet was a first-level administrative division (vilayet) of the Ottoman Empire from 1864 to 1878 with a capital in Ruse. In the late 19th century it reportedly had an area of 34,120 square miles (88,400 km2) and incorporated the Vidin Eyalet, Silistra Eyalet

The Eyalet of Silistra or Silistria (; ), later known as Özü Eyalet (; ) meaning Province of Ochakiv was an '' eyalet'' of the Ottoman Empire along the Black Sea littoral and south bank of the Danube River in southeastern Europe. The fortress ...

and Niš Eyalet.

Legal status and taxation

Christians paid disproportionately higher taxes than Muslims, including poll tax, jizye, in lieu of military service. According to İnalcık, jizye was the single most important source of income (48 per cent) to the Ottoman budget, withRumelia

Rumelia (; ; ) was a historical region in Southeastern Europe that was administered by the Ottoman Empire, roughly corresponding to the Balkans. In its wider sense, it was used to refer to all Ottoman possessions and Vassal state, vassals in E ...

accounting for the lion's share, or 81 per cent of the revenues. By the early 1600s, the timar system had virtually been abolished, and almost all land had been divided into estates (arpalik Under the Ottoman Empire, an arpalik or arpaluk () was a large estate (i.e. sanjak) entrusted to some holder of senior position, or to some margrave, as a temporary arrangement before they were appointed to some appropriate position. Arpalik was a k ...

) granted to senior Ottoman dignitaries as a form of tax farming

Farming or tax-farming is a technique of financial management in which the management of a variable revenue stream is assigned by legal contract to a third party and the holder of the revenue stream receives fixed periodic rents from the contr ...

, which created conditions for severe exploitation of taxpayers by unscrupulous land holders.

According to Radishev, overtaxation became a particularly poignant issue after jizye collection in most of the country was taken over by the Six Divisions of Cavalry The Six Divisions of Cavalry (), also known as the Kapıkulu Süvarileri (" Household Slave Cavalry"), was a corps of elite cavalry soldiers in the army of the Ottoman Empire (Sipahi). There were not really six, but four, divisions in the corps. Tw ...

.

Bulgarians also paid a number of other taxes, including a tithe ("yushur"), a land tax ("ispench"), a levy on commerce, and various irregularly collected taxes, products and corvees ("avariz"). Generally, the overall tax burden on the rayah

A raiyah or reaya (from , a plural of "countryman, animal, sheep pasturing, subjects, nationals, flock", also spelled ''raiya'', ''raja'', ''raiah'', ''re'aya''; , ; Modern Turkish ''râiya'' or ''reaya''; related to the Arabic word ''rā'ī ...

(i.e., Non-Muslims), was twice as high as that on Muslims.

Christians faced a number of other restrictions: they were barred from testifying against Muslims in inter-faith legal disputes. Even though they were free to perform their own religious rituals, this had to be done in a manner that was inconspicuous to Muslims, i.e., loud prayers or bell ringing were forbidden. They were barred from certain professions, from riding horses, from wearing certain colours or from carrying weapons.

Nevertheless, there were specific categories of rayah

A raiyah or reaya (from , a plural of "countryman, animal, sheep pasturing, subjects, nationals, flock", also spelled ''raiya'', ''raja'', ''raiah'', ''re'aya''; , ; Modern Turkish ''râiya'' or ''reaya''; related to the Arabic word ''rā'ī ...

who were exempt from nearly all such restrictions, such as the Dervendjis

Derbendcis or Derbentler were the most important and largest Ottoman military auxiliary constabulary units usually responsible for guarding important roads, bridges, fords or mountain passes. Usually, the population of an entire village near som ...

, who guarded important passes, roads, bridges, etc., ore-mining settlements such as Chiprovtsi

Chiprovtsi (, pronounced ) List of cities and towns in Bulgaria, is a small town in northwestern Bulgaria, administratively part of Montana Province. It lies on the shores of the river Ogosta in the western Balkan Mountains, very close to the Bulg ...

, etc. Some of the most important Bulgarian cultural and economic centres in the 19th century owe their development to a former dervendji status, for example, Gabrovo

Gabrovo ( ) is a city in central northern Bulgaria, the Local government, administrative centre of Gabrovo Province.It is situated at the foot of the central Balkan Mountains, in the valley of the Yantra River, and is known as an international ca ...

, Dryanovo, Kalofer

Kalofer ( pronounced:) is a town in central Bulgaria, located on the banks of the Tundzha between the Balkan Mountains to the north and the Sredna Gora to the south. Kalofer is part of Plovdiv Province and the Karlovo municipality. It is best kno ...

, Panagyurishte

Panagyurishte (, also transliterated ''Panagjurište'', ) is a town in Pazardzhik Province, Southern Bulgaria, situated in a small valley in the Sredna Gora mountains. It is 91 km east of Sofia, 43 km north of Pazardzhik. The town is ...

, Kotel, Zheravna. Similarly, Christians living on wakf holdings were subject to lower tax burden and fewer restrictions.

Religion

The Ottoman Empire's greatest advantage compared to other colonial powers, the

The Ottoman Empire's greatest advantage compared to other colonial powers, the millet

Millets () are a highly varied group of small-seeded grasses, widely grown around the world as cereal crops or grains for fodder and human food. Most millets belong to the tribe Paniceae.

Millets are important crops in the Semi-arid climate, ...

system and the autonomy each denomination had within legal, confessional, cultural and family matters, nevertheless, largely did not apply to Bulgarians and most other Orthodox peoples on the Balkans, as the independent Bulgarian Patriarchate was destroyed and all Bulgarian Orthodox dioceses were subjected to the rule of the Ecumenical Patriarch

The ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople () is the archbishop of Constantinople and (first among equals) among the heads of the several autocephalous churches that comprise the Eastern Orthodox Church. The ecumenical patriarch is regarded as ...

in Constantinople and made part of Rum millet (Greek Orthodox millet). Thus, instead of helping Christian Bulgarians maintain their customs and cultural identity, the millet system actually promoted their assimilation.

Bulgarian ceased to be a literary language, the higher clergy was invariably Greek, and the Phanariotes

Phanariots, Phanariotes, or Fanariots (, , ) were members of prominent Greek families in Phanar (Φανάρι, modern ''Fener''), the chief Greek quarter of Constantinople where the Ecumenical Patriarchate is located, who traditionally occupied ...

started making persistent efforts to hellenise Bulgarians as early as the early 1700s. It was only after the struggle for church autonomy in the mid-1800s and especially after the Bulgarian Exarchate

The Bulgarian Exarchate (; ) was the official name of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church before its autocephaly was recognized by the Ecumenical See in 1945 and the Bulgarian Patriarchate was restored in 1953.

The Exarchate (a de facto autocephaly) ...

was established by a firman

A firman (; ), at the constitutional level, was a royal mandate or decree issued by a sovereign in an Islamic state. During various periods such firmans were collected and applied as traditional bodies of law. The English word ''firman'' co ...

of Sultan Abdülaziz

Abdulaziz (; ; 8 February 18304 June 1876) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 25 June 1861 to 30 May 1876, when he was 1876 Ottoman coup d'état, overthrown in a government coup. He was a son of Sultan Mahmud II and succeeded his brother ...

in 1870 that this policy was reversed.

Non-Muslims did not serve in the Sultan's army. The exception to this were some groups of the population with specific statute, usually used for auxiliary or rear services, and the infamous blood tax (кръвен данък), also known as ''devşirme

Devshirme (, usually translated as "child levy" or "blood tax", , .) was the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman practice of Conscription, forcibly recruiting soldiers and bureaucrats from among the children of their Balkan Christian subjects and raising th ...

'', where young Christian Bulgarian boys were taken from their families, enslaved and converted to Islam and later employed either in the Janissary

A janissary (, , ) was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman sultan's household troops. They were the first modern standing army, and perhaps the first infantry force in the world to be equipped with firearms, adopted dur ...

military corps or the Ottoman administrative system. The boys were picked from one in forty households. They had to be unmarried and, once taken, were ordered to cut all ties with their family.

While a minority of authors have argued that ''"some parents were often eager to have their children enrol in the Janissary service that ensured them a successful career and comfort"'', scholarly consensus leans very much the other way. Christian parents are described to have resented the forced recruitment of their children, and would beg and seek to buy their children out of the levy. Many different ways of avoiding the devshirme are mentioned, including: marrying the boys at the age of 12, mutilating them or having both father and son convert to Islam. In 1565, the practice led to a revolt in Albania and Epirus, where the inhabitants killed the recruiting officials.

It was not rare for the boys to attempt to preserve their faith and some recollection of their homeland and their families. For example, Stephan Gerlach writes:

When Greek scholar Janus Lascaris

Janus Lascaris (, ''Ianos Láskaris''; c. 1445, Constantinople – 7 December 1535, Rome), also called John Rhyndacenus (from Rhyndacus, a country town in Asia Minor), was a noted Greek scholar in the Renaissance.

Biography

After the Fall of Con ...

visited Constantinople in 1491, he met many Janissaries who not only remembered their former religion and their native land but also favoured their former coreligionists. One of them told him that he regretted having left the religion of his fathers and that he prayed at night before the cross which he kept carefully concealed.

Spread of Islam

Islam in Bulgaria spread through both colonisation with Muslims from Asia Minor and conversion of native Bulgarians. The Ottomans' mass population transfers began in the late 1300s and continued well into the 1500s. The first community settled in present-day Bulgaria was made up of Tatars who willingly arrived to begin a settled life as farmers, the second one a tribe of nomads that had run afoul of the Ottoman administration. Both groups settled in theUpper Thracian Plain

The Upper Thracian Plain (, ''Gornotrakiyska nizina'') constitutes the northern part of the historical region of Thrace. It is located in southern Bulgaria, between Sredna Gora mountains to the north and west, a secondary mountain chain parallel ...

, in the vicinity of Plovdiv. Another large group of Tatars was moved by Mehmed I to Thrace in 1418, followed by the relocation of more than 1000 Turkoman families to Northeastern Bulgaria in the 1490s. At the same time, there are records of at least two forced relocations of Bulgarians to Anatolia, one right after the fall of Veliko Tarnovo

Veliko Tarnovo (, ; "Great Tarnovo") is a city in north central Bulgaria and the administrative centre of Veliko Tarnovo Province. It is the historical and spiritual capital of Bulgaria.

Often referred to as the "''City of the Tsars''", Velik ...

and a second one to İzmir

İzmir is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, third most populous city in Turkey, after Istanbul and Ankara. It is on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, and is the capital of İzmir Province. In 2024, the city of İzmir had ...

in the mid-1400s. The goal of this "mixing of peoples" was to quell any unrest in the conquered Balkan states, while simultaneously getting rid of troublemakers in the Ottoman backyard in Anatolia.

However, Ottomans never pursued or practiced forced Islamisation of the Bulgarian population, as had earlier been claimed by Communist Bulgarian historiography. According to scholarly consensus, conversion to Islam was voluntary as it offered Bulgarians religious and economic benefits. According to Thomas Walker Arnold

Sir Thomas Walker Arnold (19 April 1864 – 9 June 1930) was a British orientalist and historian of Islamic art. He taught at Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College (MAO College), later Aligarh Muslim University, and Government College Un ...

, Islam was not spread by force in the areas under the control of the Ottoman Sultan

The sultans of the Ottoman Empire (), who were all members of the Ottoman dynasty (House of Osman), ruled over the Boundaries between the continents, transcontinental empire from its perceived inception in 1299 to Dissolution of the Ottoman Em ...

.The preaching of Islam: a history of the propagation of the Muslim faith By Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, pg. 135-144 A 17th-century author said: ''Meanwhile he (the Turk) wins (converts) by craft more than by force, and snatches away Christ by fraud out of the hearts of men. For the Turk, it is true, at the present time compels no country by violence to apostatise; but he uses other means whereby imperceptibly he roots out Christianity...''Thus, in a number of cases, conversion to Islam can be said to have been the result of tax coercion, due to the much lower tax burden on Muslims. While some authors have argued that other factors, such as desire to retain social status, were of greater importance, Turkish writer

Halil İnalcık

Halil İnalcık (7 September 1916 – 25 July 2016) was a Turkish historian. His highly influential research centered on social and economic approaches to the Ottoman Empire. His academic career started at Ankara University, where he completed h ...

has referred to the desire to stop paying jizya as a primary incentive for conversion to Islam in the Balkans, and Bulgarian researcher Anton Minkov has argued that it was one among several motivating factors.

Two large-scale studies of the causes of adoption of Islam in Bulgaria, one of the Chepino Valley by Dutch Ottomanist Machiel Kiel, and another one of the region of Gotse Delchev

Georgi Nikolov Delchev (; ; 4 February 1872 – 4 May 1903), known as Gotse Delchev or Goce Delčev (''Гоце Делчев''),Originally spelled in older Bulgarian orthography as ''Гоце Дѣлчевъ''. - Гоце Дѣлчевъ. ...

in the Western Rhodopes by Evgeni Radushev reveal a complex set of factors behind the process. These include: pre-existing high population density owing to the late inclusion of the two mountainous regions in the Ottoman system of taxation; immigration of Christian Bulgarians from lowland regions to avoid taxation throughout the 1400s; the relative poverty of the regions; early introduction of local Christian Bulgarians to Islam through contacts with nomadic Yörüks

The Yörüks, also Yuruks or Yorouks (; , ''Youroúkoi''; ; , ''Juruci''), are a Turkish ethnic subgroup of Oghuz descent, some of whom are nomadic, primarily inhabiting the mountains of Anatolia, and partly in the Balkan peninsula. On the Bal ...

; the nearly constant Ottoman conflict with the Habsburgs

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

from the mid-1500s to the early 1700s; the resulting massive war expenses that led to a sixfold increase in the jizya rate from 1574 to 1691 and the imposition of a war-time avariz tax; the Little Ice Age

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a period of regional cooling, particularly pronounced in the North Atlantic region. It was not a true ice age of global extent. The term was introduced into scientific literature by François E. Matthes in 1939. Mat ...

in the 1600s that caused crop failures and widespread famine; heavy corruption and overtaxation by local landholders—all of which led to a slow, but steady process of Islamisation until the mid-1600s when the tax burden became so unbearable that most of the remaining Christians either converted en masse or left for lowland areas.

These factors had an impact on the entire country. Due to them, the population of Ottoman Bulgaria is presumed to have dropped twofold from a peak of approx. 1.8 million (1.2 million Christians and 0.6 million Muslims) in the 1580s to approx. 0.9 million in the 1680s (450,000 Christians and 450,000 Muslims), after growing steadily from a base of approx. 600,000 (450,000 Christians and 150,000 Muslims) in the 1450s.

First revolts and the Great Powers

While the Ottomans were ascendant, there was overt opposition to their rule. The first revolt began at the time

While the Ottomans were ascendant, there was overt opposition to their rule. The first revolt began at the time Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans (disambiguation), Emperor of the Romans (; ) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period (; ), was the ruler and h ...

Sigismund Sigismund (variants: Sigmund, Siegmund) is a German proper name, meaning "protection through victory", from Old High German ''sigu'' "victory" + ''munt'' "hand, protection". Tacitus latinises it ''Segimundus''. There appears to be an older form of ...

established the chivalric Order of the Dragon

The Order of the Dragon (, literally "Society of the Dragonists") was a Chivalric order#Monarchical or dynastical orders, monarchical chivalric order only for selected higher aristocracy and monarchs,Florescu and McNally, ''Dracula, Prince of M ...

, 1408, when two Bulgarian nobles, Konstantin

The first name Konstantin () is a derivation from the Latin name '' Constantinus'' ( Constantine) in some European languages, such as Bulgarian, Russian, Estonian and German. As a Christian given name, it refers to the memory of the Roman empe ...

and Fruzhin, revolted and liberated some regions for several years. The earliest evidence of continued local resistance dates from before 1450. Radik (''alternatively'' Radich) was recognised by the Ottomans as a voyvoda

Voivode ( ), also spelled voivod, voievod or voevod and also known as vaivode ( ), voivoda, vojvoda, vaivada or wojewoda, is a title denoting a military leader or warlord in Central, Southeastern and Eastern Europe in use since the Early Mid ...

of the Sofia region in 1413, but later he turned against them and is regarded as the first hayduk in Bulgarian history. More than a century later, two Tarnovo uprisings occurred - in 1598 ( First Tarnovo Uprising) and 1686 ( Second Tarnovo Uprising) around the old capital Tarnovo

Veliko Tarnovo (, ; "Great Tarnovo") is a city in north central Bulgaria and the administrative centre of Veliko Tarnovo Province. It is the historical and spiritual capital of Bulgaria.

Often referred to as the "''City of the Tsars''", Velik ...

.

Those were followed by the Catholic Chiprovtsi Uprising in 1688 and insurrection in Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

led by Karposh in 1689, both provoked by the Austrians

Austrians (, ) are the citizens and Nationality, nationals of Austria. The English term ''Austrians'' was applied to the population of Archduchy of Austria, Habsburg Austria from the 17th or 18th century. Subsequently, during the 19th century, ...

as part of their long war with the Ottomans. All of the uprisings were unsuccessful and were brutally suppressed . Most of them resulted in massive waves of exiles, often numbering hundreds of thousands. In 1739 the Treaty of Belgrade

The Treaty of Belgrade, also known as the Belgrade Peace, was a peace treaty between the Habsburg Monarchy and Ottoman Empire, that was signed on September 18, 1739 in Belgrade (modern Serbia), thus ending the Austro–Turkish War (1737–1739) ...

between Austrian empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

ended Austrian interest in the Balkans for a century. But by the 18th century the rising power of Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

was making itself felt in the area. The Russians, as fellow Orthodox Slavs, could appeal to the Bulgarians in a way that the Austrians could not. The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca

The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (; ), formerly often written Kuchuk-Kainarji, was a peace treaty signed on , in Küçük Kaynarca (today Kaynardzha, Bulgaria and Cuiugiuc, Romania) between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire, ending the R ...

of 1774 gave Russia the right to interfere in Ottoman affairs to protect the Sultan's Christian subjects.

Bulgarian National Awakening and Revival

Bulgarians

Bulgarians (, ) are a nation and South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Bulgaria and its neighbouring region, who share a common Bulgarian ancestry, culture, history and language. They form the majority of the population in Bulgaria, ...

under Ottoman rule. It is commonly accepted to have started with the historical book, ''Istoriya Slavyanobolgarskaya

''Istoriya Slavyanobolgarskaya'' ( Original Cyrillic: Истори́ѧ славѣноболгарскаѧ corrected from Їстори́ѧ славѣноболгарскаѧ; ) is a book by Bulgarian scholar and clergyman Saint Paisius of Hilen ...

'', written in 1762 by Paisius, a Bulgarian monk of the Hilandar

The Hilandar Monastery (, , , ) is one of the twenty Eastern Orthodox monasteries in Mount Athos in Greece and the only Serbian Orthodox monastery there.

It was founded in 1198 by two Serbs from the Grand Principality of Serbia, Stefan Neman ...

monastery at Mount Athos

Mount Athos (; ) is a mountain on the Athos peninsula in northeastern Greece directly on the Aegean Sea. It is an important center of Eastern Orthodoxy, Eastern Orthodox monasticism.

The mountain and most of the Athos peninsula are governed ...

, lead to the National awakening of Bulgaria

The National awakening of Bulgaria refers to the Bulgarian nationalism that emerged in the early 19th century under the influence of western ideas such as liberalism and nationalism, which trickled into the country after the French Revolution, ...

and the modern Bulgarian nationalism, and lasted until the Liberation of Bulgaria in 1878 as a result of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78.

The Millet system

In the Ottoman Empire, a ''millet'' (; ) was an independent court of law pertaining to "personal law" under which a confessional community (a group abiding by the laws of Muslim sharia, Christian canon law, or Jewish halakha) was allowed to rule ...

was a set of confessional communities in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. It referred to the separate legal courts pertaining to "personal law" under which religious communities were allowed to rule themselves under their own system. The Sultan regarded the Ecumenical Patriarch

The ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople () is the archbishop of Constantinople and (first among equals) among the heads of the several autocephalous churches that comprise the Eastern Orthodox Church. The ecumenical patriarch is regarded as ...

of the Constantinople Patriarchate as the leader of the Orthodox Christian peoples of his empire. After the Ottoman Tanzimat

The (, , lit. 'Reorganization') was a period of liberal reforms in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Edict of Gülhane of 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 1876. Driven by reformist statesmen such as Mustafa Reşid Pash ...

(1839–76) reforms, Nationalism

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Theory, I ...

arose in the Empire and the term was used for legally protected religious minority group

The term "minority group" has different meanings, depending on the context. According to common usage, it can be defined simply as a group in society with the least number of individuals, or less than half of a population. Usually a minority g ...

s, similar to the way other countries use the word ''nation

A nation is a type of social organization where a collective Identity (social science), identity, a national identity, has emerged from a combination of shared features across a given population, such as language, history, ethnicity, culture, t ...

''. New millets were created in 1860 and 1870.

The Bulgarian Exarchate

The Bulgarian Exarchate (; ) was the official name of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church before its autocephaly was recognized by the Ecumenical See in 1945 and the Bulgarian Patriarchate was restored in 1953.

The Exarchate (a de facto autocephaly) ...

(a de facto autocephalous

Autocephaly (; ) is the status of a hierarchical Christian church whose head bishop does not report to any higher-ranking bishop. The term is primarily used in Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches. The status has been compared with t ...

Orthodox church) was created as separate Bulgarian diocese based on voted ethnic identity

An ethnicity or ethnic group is a group of people with shared attributes, which they collectively believe to have, and long-term endogamy. Ethnicities share attributes like language, culture, common sets of ancestry, traditions, society, rel ...

. It was unilaterally (without the blessing of the Ecumenical Patriarch

The ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople () is the archbishop of Constantinople and (first among equals) among the heads of the several autocephalous churches that comprise the Eastern Orthodox Church. The ecumenical patriarch is regarded as ...

) promulgated on , in the Bulgarian church

The Bulgarian Orthodox Church (), legally the Patriarchate of Bulgaria (), is an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox jurisdiction based in Bulgaria. It is the first medieval recognised patriarchate outside the Pentarchy and the oldest Slavic Orthod ...

in Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

in pursuance of the firman

A firman (; ), at the constitutional level, was a royal mandate or decree issued by a sovereign in an Islamic state. During various periods such firmans were collected and applied as traditional bodies of law. The English word ''firman'' co ...

of Sultan Abdülaziz

Abdulaziz (; ; 8 February 18304 June 1876) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 25 June 1861 to 30 May 1876, when he was 1876 Ottoman coup d'état, overthrown in a government coup. He was a son of Sultan Mahmud II and succeeded his brother ...

of the Ottoman Empire.

The foundation of the Exarchate was the direct result of the struggle of the Bulgarian Orthodox population against the domination of the Greek Patriarchate of Constantinople

The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople (, ; ; , "Roman Orthodox Patriarchate, Ecumenical Patriarchate of Istanbul") is one of the fifteen to seventeen autocephalous churches that together compose the Eastern Orthodox Church. It is headed ...

in the 1850s and 1860s. In 1872, the Patriarchate accused the Exarchate that it introduced ''ethno-national'' characteristics in the religious organization of the Orthodox Church, and the secession from the Patriarchate was officially condemned by the Council in Constantinople in September 1872 as schism

A schism ( , , or, less commonly, ) is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization, movement, or religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a split in what had previously been a single religious body, suc ...

atic. Nevertheless, Bulgarian religious leaders continued to extend the borders of the Exarchate in the Ottoman Empire by conducting plebiscites in areas contested by both Churches.

In this way, in the struggle for recognition of a separate Church, the modern Bulgarian nation was created under the name Bulgar Millet.

Also the Bulgarian Uniat Church

The Bulgarian Greek Catholic Church is a ''sui iuris'' ("autonomous") Eastern Catholic church based in Bulgaria. As a particular church of the Catholic Church, it is in full communion with the Holy See. The church's liturgical usage is that ...

was created.

Armed resistance to the Ottoman rule escalated in the third quarter of the 19th century and reached its climax with the April Uprising

The April Uprising () was an insurrection organised by the Bulgarians in the Ottoman Empire from April to May 1876. The rebellion was suppressed by irregular Ottoman bashi-bazouk units that engaged in indiscriminate slaughter of both rebels ...

of 1876 that covered part of the ethnically Bulgarian territories of the empire. The uprising, provoked the Constantinople Conference

The 1876–77 Constantinople Conference ( "Shipyard Conference", after the venue ''Tersane Sarayı'' "Shipyard Palace") of the Great Powers (Austria-Hungary, Britain, France, Germany, Italy and Russia) was held in Constantinople (now Istanbul) f ...

(1876-1877), and along with the strategic interests of Russia on the Balkans, was a reason for the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878 that ended with the reestablishment of independent Bulgarians state in 1878, albeit under the Treaty of Berlin Bulgarians were divided, and the territory of the Principality of Bulgaria

The Principality of Bulgaria () was a vassal state under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire. It was established by the Treaty of Berlin in 1878.

After the Russo-Turkish War ended with a Russian victory, the Treaty of San Stefano was signed ...

was far smaller than what Bulgarians had hoped for and what was originally proposed in the Treaty of San Stefano

The 1878 Preliminary Treaty of San Stefano (; Peace of San-Stefano, ; Peace treaty of San-Stefano, or ) was a treaty between the Russian and Ottoman empires at the conclusion of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. It was signed at San Ste ...

.

Demographics

Late 1300s to early 1800s

The effect of the Ottoman conquest on Bulgarian demography is uncertain and subject to much contention. However, the population of present-day Bulgaria in the 1450s is estimated to have hit a low of 600,000 people, divided into approx. 450,000 Christians and 150,000 Muslims (or a Christian-to-Muslim ratio of 3:1 or 75 per cent to 25 per cent) following the wide-scale migration of Muslims from Anatolia and emigration of Christians to Wallachia, etc. Both the Christian and Muslim population then grew steadily until the 1580s, reaching approx. 1.8 million, or 1.2 million Christians and 0.6 million Muslims (or a Christian-to-Muslim ratio of 2:1 or 66 per cent to 33 per cent), where the higher growth among the Muslims is attributed to both conversion of Christians and the last waves of Muslim migrants from Anatolia. As a result of the near-constant war led by the Ottoman Empire from the mid-1500s to the late 1600s, the need for additional tax revenues, the sixfold increase in jizye tax rates, which pauperised the Christian population, theLittle Ice Age

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a period of regional cooling, particularly pronounced in the North Atlantic region. It was not a true ice age of global extent. The term was introduced into scientific literature by François E. Matthes in 1939. Mat ...

in the 1600s that caused crop failures and widespread famine and several important Bulgarian uprisings, e.g., the First Tarnovo Uprising, the Chiprovtsi uprising, the Second Tarnovo uprising and Karposh's rebellion, which led to the massive flight of Christian Bulgarians to Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ; : , : ) is a historical and geographical region of modern-day Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and south of the Southern Carpathians. Wallachia was traditionally divided into two sections, Munteni ...

and the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

, the population of present-day Bulgaria in the 1680s is assumed to have dropped to approx. 0.9 million in the 1680s, divided into 450,000 Christians and 450,000 Muslims (or a ratio of 1:1). From the early 1700s, the Christian population is assumed to have started growing again.

1831 Ottoman census

According to the 1831 Ottoman census, the male population in the Ottoman kazas that fall within the current borders of theRepublic of Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

stood at 496,744 people, including 296,769 Christians, 181,455 Muslims, 17,474 Romani

Romani may refer to:

Ethnic groups

* Romani people, or Roma, an ethnic group of Indo-Aryan origin

** Romani language, an Indo-Aryan macrolanguage of the Romani communities

** Romanichal, Romani subgroup in the United Kingdom

* Romanians (Romanian ...

, 702 Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

and 344 Armenians

Armenians (, ) are an ethnic group indigenous to the Armenian highlands of West Asia.Robert Hewsen, Hewsen, Robert H. "The Geography of Armenia" in ''The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times Volume I: The Dynastic Periods: From Antiq ...

. The census only covered healthy taxable men between 15 and 60 years of age, who were free from disability.

By using primary population records from the Danube Vilayet, Bulgarian statistician Dimitar Arkadiev has found that men aged 15–60 represented, on average, 49.5% of all males and that the coefficient that would make it possible to calculate the entire male population is therefore 2.02. To compute total population, male figures are then usually doubled (Bulgarian authors have suggested a coefficient of 1.956, but this has not gained international acceptance). Using this method of computation, ''(N=2 x (Y x 2.02))'', the population of present-day Bulgaria in 1831 would stand at 2,006,845 people.

Ottoman population records (1860-1875) for the future Principality of Bulgaria

The

The Principality of Bulgaria

The Principality of Bulgaria () was a vassal state under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire. It was established by the Treaty of Berlin in 1878.

After the Russo-Turkish War ended with a Russian victory, the Treaty of San Stefano was signed ...

was established on 13 July 1878 and incorporated five of the sanjaks that used to be part of the Ottoman Danube Vilayet:

The Sanjaks of Vidin

Vidin (, ) is a port city on the southern bank of the Danube in north-western Bulgaria. It is close to the borders with Romania and Serbia, and is also the administrative centre of Vidin Province, as well as of the Metropolitan of Vidin (since ...

, Tirnova, Rusçuk, Sofya and Varna

Varna may refer to:

Places Europe

*Varna, Bulgaria, a city

** Varna Province

** Varna Municipality

** Gulf of Varna

** Lake Varna

**Varna Necropolis

* Vahrn, or Varna, a municipality in Italy

* Varna (Šabac), a village in Serbia

Asia

* Var ...

, with individual border changes, cf. below. The two other sanjaks in the Danube Vilayet, those of Niš

Niš (; sr-Cyrl, Ниш, ; names of European cities in different languages (M–P)#N, names in other languages), less often spelled in English as Nish, is the list of cities in Serbia, third largest city in Serbia and the administrative cente ...

and Tulça, were ceded to Serbia and Romania, respectively.

According to the "Kuyûd-ı Atîk" Ottoman Population Register, the ''male'' population of the five sanjaks to eventually form the future Principality of Bulgaria

The Principality of Bulgaria () was a vassal state under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire. It was established by the Treaty of Berlin in 1878.

After the Russo-Turkish War ended with a Russian victory, the Treaty of San Stefano was signed ...

was divided into the following ethnoconfessional communities in 1865:

Between 1855 and 1865, the population of the Danube Vilayet underwent seismic changes, as the Ottoman authorities settled more than 300,000 Crimean Tatars

Crimean Tatars (), or simply Crimeans (), are an Eastern European Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group and nation indigenous to Crimea. Their ethnogenesis lasted thousands of years in Crimea and the northern regions along the coast of the Blac ...

and Circassians

The Circassians or Circassian people, also called Cherkess or Adyghe (Adyghe language, Adyghe and ), are a Northwest Caucasian languages, Northwest Caucasian ethnic group and nation who originated in Circassia, a region and former country in t ...

on the territory of the province. The settlement took place in two waves: one of 142,852 Tatars and Nogais

The Nogais ( ) are a Kipchaks, Kipchak people who speak a Turkic languages, Turkic language and live in Southeastern Europe, North Caucasus, Volga region, Central Asia and Turkey. Most are found in Northern Dagestan and Stavropol Krai, as well ...

, with a minority of Circassians, who settled in the Danube Vilayet between 1855 and 1862, and a second one of some 35,000 Circassian families (140,000–175,000 settlers), who arrived in 1864.

According to Turkish scholar Kemal Karpat

Kemal Karpat (15 February 1924, Babadag Tulcea, Romania – 20 February 2019, Manchester, New Hampshire, United States) was a Romanian- Turkish naturalised American historian and professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Early life ...

, the Tatar and Circassian colonisation of the vilayet not only offset the heavy Muslim population losses earlier in the century, but also counteracted continued population loss and led to an increase in its Muslim population. In this connection, Karpat also refers to the material differences between Muslim and non-Muslim fertility rates, with non-Muslims growing at the rate of 2% per annum and Muslims usually averaging 0%.

Koyuncu also notes a much higher natural rate of increase among Non-Muslims and attributes the tremendous rate of increase in the Muslim population of the five Bulgarian sanjaks plus the Sanjak of Tulça of 84.23% (220,276 males) vs. 53.29% (229,188 males) for Non-Muslims from 1860 to 1875 to the colonisation of the vilayet with Crimean Tatars and Circassians.

The Congress of Berlin

At the Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878), the major European powers revised the territorial and political terms imposed by the Russian Empire on the Ottoman Empire by the Treaty of San Stefano (March 1878), which had ended the Rus ...

ceded the kaza of Cuma-i Bâlâ from the Sanjak of Sofia (male Muslim population of 2,896 and male non-Muslim population of 8,038) to the Ottoman Empire and the kaza of Mankalya from the Sanjak of Varna (male Muslim population of 6,675 and male non-Muslim population of 499) to Romania and attached the kaza of Iznebol (male Muslim population of 149 and male non-Muslim population of 7,072) from the Sanjak of Niš to the Principality of Bulgaria.

At the same time, a flash summary of the results of the Danube Vilayet Census published in the Danube Official Gazette on 18 October 1874 (also covering the Sanjak of Tulça) gave twice as many ''male'' Circassian Muhacir

The Muhacirs are estimated to be millions of Ottoman Muslim citizens and their descendants born after the onset of the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire. Muhacirs are primarily consist of Turks but also Albanian, Bosniaks, Circassians, Cri ...

, 64,398 vs. 30,573, and slightly fewer "established Muslims" than the final results published in 1875. According to Turkish Ottomanist Koyuncu, 13,825 ''male'' Circassians were carried over to the "established Muslims" column and additional 20,000 were left out or simply lost in the carry-over.The division of Muslims into "Established" and "Muhacir" in the 1873-1874 Census and the 1875 Ottoman Salname was not based on origin, as the name might suggest, but on "taxability". Thus, colonists whose tax exemption had expired and were liable to taxation (i.e., those of them who had settled prior to 1862—Crimean Tatars, Nogais, etc. and a minority of Circassians) were counted as "Established", while colonists who still benefited from a tax exemption (as a rule, Circassians arriving in 1864 or later) were regarded as "Muhacir". Contemporary European geographers, such as German-English

Ravenstein Ravenstein may refer to:

Places

* Ravenstein, Germany in the district Neckar-Odenwald, Baden-Württemberg

* Ravenstein, Netherlands in Oss, North Brabant

* Ravenstein railway station

Films

Ravenstein a 2020 British Horror film

People with the ...

, French Bianconi and German Kiepert similarly counted Crimean Tatars with Turks in Islam millet.

Unlike the Circassian colonisation in 1864 and later years, where precise numbers are elusive, the settlement of Crimean Tatars, Nogais, etc. in 1855-1862 has been documented minutely. Out of a total of 34,344 households with 142,852 members (or 4.16 members per household on average) settled along the Danube, a total of 22,360 households with some 93,000 members were given land in kazas that became part of the Principality of Bulgaria.

Adjusting for territorial changes (net loss of 9,422 males, or 18,844 people, for the Est. Muslims and 1,465 males, or 2,930 people, for the Bulgarians), the incorrect entry or carry-over of Muhacir from the '73-74 Census (net loss of 13,825 males, or 27,650 people, for the Est. Muslims and net gain of 33,825 males, or 67,650 people, for the Muhacir), the categorisation of the first wave of refugees as Established (net loss and net gain of 93,000 people for the Established Muslims and Muhacir, respectively), and considering that the Est. Muslims category was also estimated to include some 20,000 Pomaks, mostly living in the region of Lovech

Lovech (, ) is a city in north-central Bulgaria. It is the administrative centre of the Lovech Province and of the subordinate Lovech Municipality. The city is located about northeast from the capital city of Sofia. Near Lovech are the towns of ...

.Мошин, А. (1877) Придунайская Болгария (Дунайский вилает). Статистико-экономический очерк. В: Славянский сборник, т. ІІ. Санкт Петербург, the population living in the future Principality of Bulgaria

The Principality of Bulgaria () was a vassal state under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire. It was established by the Treaty of Berlin in 1878.

After the Russo-Turkish War ended with a Russian victory, the Treaty of San Stefano was signed ...

in 1875 was estimated at 2,085,224 people, of whom 1,187,564 were Bulgarians (56.96%); 546,776 Turks (26.22%); 215,828 Crimean and Circassian Muhacir (10.35%); 49,392 Muslim Romani (2.35%); 30,380 Miscellaneous Christians (1.46%); 20,000 Pomaks (0.96%); 14,606 Christian Romani (0.70%); 9,190 Jews (0.44%); 7,830 Greeks (0.38%); 3,598 Armenians (0.17%).

Of particular note is that fully 10% of the total population, and 25% of all Muslims in the sanjaks, were made up of non-native refugees/colonists, who had arrived only 10 to 20 years before, and whose area of settlement had been carefully picked by the Ottoman authorities in order to: increase Muslim population on the Balkans; cordon off Bulgaria from its neighbours and aid in fighting against a future Russian invasion, act as a counterbalance to Rumelia's Christian population.

In the words of Nusret Pasha, Head of the Silistra Eylaet Colonisation Commission himself, to

In the words of Nusret Pasha, Head of the Silistra Eylaet Colonisation Commission himself, to Hürriyet

''Hürriyet'' (, ''Liberty'') is a major List of newspapers in Turkey, Turkish newspaper, founded in 1948. it had the highest circulation of any newspaper in Turkey at around 319,000. ''Hürriyet'' combines entertainment with news coverage and ...

on 19 October 1868, the Circassians were settled along the Danube in order to serve as live fortification and barrier against Russia.

Ottoman population records (1876) for the future Eastern Rumelia

The other Bulgarian territory to be carved out of the Ottoman Empire was the autonomous province ofEastern Rumelia

Eastern Rumelia (; ; ) was an autonomous province (''oblast'' in Bulgarian, ''vilayet'' in Turkish) of the Ottoman Empire with a total area of , which was created in 1878 by virtue of the Treaty of Berlin (1878), Treaty of Berlin and ''de facto'' ...

. It incorporated the Sanjak of İslimye, most of the Sanjak of Filibe (without the Ahi Çelebi/Smolyan

Smolyan () is a List of cities and towns in Bulgaria, town and ski resort in the south of Bulgaria near the border with Greece. It is the administrative and industrial centre of the Smolyan Province. The town is built along the narrow valley of t ...

and Sultanyeri/Momchilgrad

Momchilgrad ( , , Turkish language, Turkish: Mestanlı) is a town in the very south of Bulgaria, part of Kardzhali Province in the southern part of the Eastern Rhodopes. According to the 2011 census, Momchilgrad is the largest Bulgarian settlemen ...

kazas), a smaller part of the Sanjak of Edirne (the Kızılağaç/Elhovo

Elhovo ( ) is a Bulgarian town in Yambol Province, located on the left bank of the Tundzha river, between Strandzha and Sakar Mountain, Sakar mountains. Second largest city in the region after Jambol, the city is located at 36 km from border ...

kaza and Manastır/ Topolovgrad nahiya), along with parts of the Üsküdar and Çöke nahiyas, again from the Sanjak of Edirne.

The following are district-by-district population records from the 1876 Ottoman salname, based on the Adrianople Vilayet census of 1875. As is common for Ottoman statistics, figures refer to ''males'' only (figures at the bottom are male-female aggregated estimates):

According to British diplomat Drummond-Wolff, apart from Turks, Islam millet also included 25,000 Muslim Bulgarians, 10,000 Tatars and Nogays and 10,000 Circassians. At the same time, British historian R.J. Moore has identified 4,000 male Greeks (or 8,000 in total) in the Sanjak of Filibe,''More, R.J.'', Under the Balkans. Notes of a visit to the district of Philippopolis in 1876. London, 1877. and the British consulary service additional 22,000 in the Sanjak of İslimye and 5,693 in the Manastır nahiya, or a total of 35,693 Greeks, who had been counted together with the Orthodox Bulgarians. In turn, all Catholics were Bulgarian Paulicians.

Thus, Eastern Rumelia's total population of 912,114 people prior to the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878) was divided into 528,673 Christian Bulgarians (57.96%), 257,322 Turks (28.21%), 35,693 Greeks (3.91%), 31,634 Muslim Romani (3.47%), 25,000 Pomaks or Muslim Bulgarians (2.74%), 20,000 Muhacir (2.19%), 6,616 Christian Romani (0.73%), 5,806 Jews (0.64%) and 1,370 Armenians (0.15%).

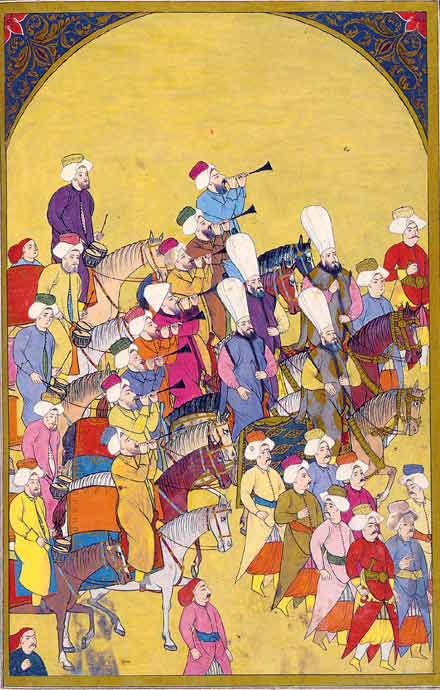

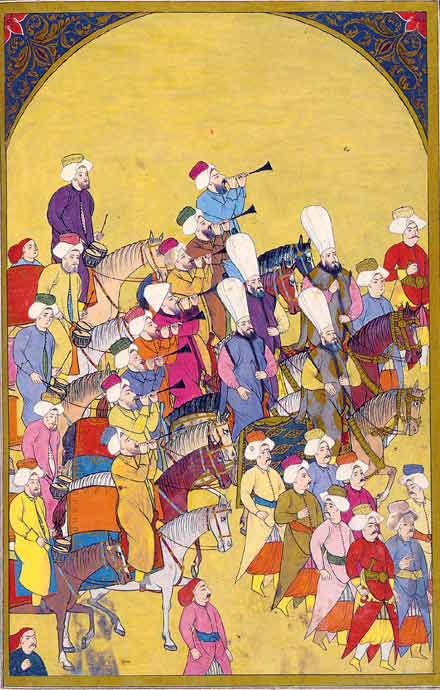

Gallery

Sofia

Sofia is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Bulgaria, largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain, in the western part of the country. The city is built west of the Is ...

, from ''Les costumes populaires de la Turquie en 1873'', published under the patronage of the Ottoman Imperial Commission for the 1873 Vienna World's Fair

The 1873 Vienna World's Fair () was the large world exposition that was held from 1 May to 31 October 1873 in the Austria-Hungarian capital Vienna. Its motto was "Culture and Education" ().

History

As well as being a chance to showcase Austro- ...

File:Lescostumespopul00osma.pdf, page=83, Bulgarian woman of Roustchouk and Bulgarian men of Vidin

Vidin (, ) is a port city on the southern bank of the Danube in north-western Bulgaria. It is close to the borders with Romania and Serbia, and is also the administrative centre of Vidin Province, as well as of the Metropolitan of Vidin (since ...

, from ''Les costumes populaires de la Turquie en 1873'', published under the patronage of the Ottoman Imperial Commission for the 1873 Vienna World's Fair

File:Lescostumespopul00osma.pdf, page=67, Bulgarian men of Koyuntepe and Ahı Çelebi and Muslim man of Filibe, from ''Les costumes populaires de la Turquie en 1873'', published under the patronage of the Ottoman Imperial Commission for the 1873 Vienna World's Fair

File:Lescostumespopul00osma.pdf, page=71, Bulgarian woman of Ahı Çelebi and Greek woman of Haskovo

Haskovo ( ) is a city in the region of Northern Thrace in southern Bulgaria and the administrative centre of the Haskovo Province, not far from the borders with Greece and Turkey. According to Operative Program Regional Development of Bulgaria ...

, from ''Les costumes populaires de la Turquie en 1873'', published under the patronage of the Ottoman Imperial Commission for the 1873 Vienna World's Fair

See also

*Ottoman Vardar Macedonia

North Macedonia was part of the Ottoman Empire for over 500 years, from the late 14th century until the Treaty of Bucharest in 1913. Before its conquest, this area was divided between various Serbian feudal principalities. Later, it became part ...

*Bulgarian Exarchate

The Bulgarian Exarchate (; ) was the official name of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church before its autocephaly was recognized by the Ecumenical See in 1945 and the Bulgarian Patriarchate was restored in 1953.

The Exarchate (a de facto autocephaly) ...

*April Uprising of 1876

The April Uprising () was an insurrection organised by the Bulgarians in the Ottoman Empire from April to May 1876. The rebellion was suppressed by irregular military, irregular Ottoman bashi-bazouk units that engaged in indiscriminate slaught ...

*Constantinople Conference

The 1876–77 Constantinople Conference ( "Shipyard Conference", after the venue ''Tersane Sarayı'' "Shipyard Palace") of the Great Powers (Austria-Hungary, Britain, France, Germany, Italy and Russia) was held in Constantinople (now Istanbul) f ...

* Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878

*Treaty of San Stefano

The 1878 Preliminary Treaty of San Stefano (; Peace of San-Stefano, ; Peace treaty of San-Stefano, or ) was a treaty between the Russian and Ottoman empires at the conclusion of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. It was signed at San Ste ...

*Treaty of Berlin (1878)

The Treaty of Berlin (formally the Treaty between Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Great Britain and Ireland, Italy, Russia, and the Ottoman Empire for the Settlement of Affairs in the East) was signed on 13 July 1878. In the aftermath of the R ...

*Kresna–Razlog uprising

The Kresna–Razlog uprising (), also known as the Kresna uprising or Macedonian Uprising (), was an anti-Ottoman Bulgarian uprising that took place in Ottoman Macedonia, predominantly in the areas of modern Blagoevgrad Province in Bulgaria in l ...

*Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising

The Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising (), consisting of the Ilinden Uprising (; ) and Preobrazhenie Uprising,Keith Brown (2013). Loyal Unto Death Trust and Terror in Revolutionary Macedonia. Indiana University Press. pp. 15-18. . was an organi ...

Footnotes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

{{Authority control Islam in Bulgaria 2nd millennium in Bulgaria Ottoman Empire States and territories disestablished in 1878