The history of botany examines the human effort to understand life on Earth by tracing the historical development of the discipline of

botany

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

—that part of natural science dealing with organisms traditionally treated as plants.

Rudimentary botanical science began with empirically based plant lore passed from generation to generation in the oral traditions of

Paleolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic ( years ago) ( ), also called the Old Stone Age (), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone tools, and which represents almost the entire period of human prehist ...

hunter-gatherer

A hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living in a community, or according to an ancestrally derived Lifestyle, lifestyle, in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local naturally occurring sources, esp ...

s. The first writings that show human curiosity about plants themselves, rather than the uses that could be made of them, appear in

ancient Greece

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically r ...

and ancient India. In Ancient Greece, the teachings of

Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

's student

Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; ; c. 371 – c. 287 BC) was an ancient Greek Philosophy, philosopher and Natural history, naturalist. A native of Eresos in Lesbos, he was Aristotle's close colleague and successor as head of the Lyceum (classical), Lyceum, the ...

at the

Lyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies among countries; usually it is a type of secondary school. Basic science and some introduction to ...

in

ancient Athens

Athens is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest named cities in the world, having been continuously inhabited for perhaps 5,000 years. Situated in southern Europe, Athens became the leading city of ancient Greece in t ...

in about 350 BC are considered the starting point for Western botany. In ancient India, the Vṛkṣāyurveda, attributed to

Parashara, is also considered one of the earliest texts to describe various branches of botany.

In Europe, botanical science was soon overshadowed by a

medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

preoccupation with the medicinal properties of plants that lasted more than 1000 years. During this time, the medicinal works of classical antiquity were reproduced in manuscripts and books called

herbal

A herbal is a book containing the names and descriptions of plants, usually with information on their medicinal, Herbal tonic, tonic, culinary, toxic, hallucinatory, aromatic, or Magic (paranormal), magical powers, and the legends associated wi ...

s. In China and the Arab world, the

Greco-Roman work on medicinal plants was preserved and extended.

In Europe, the

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

of the 14th–17th centuries heralded a scientific revival during which botany gradually emerged from

natural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

as an independent science, distinct from medicine and agriculture.

Herbal

A herbal is a book containing the names and descriptions of plants, usually with information on their medicinal, Herbal tonic, tonic, culinary, toxic, hallucinatory, aromatic, or Magic (paranormal), magical powers, and the legends associated wi ...

s were replaced by

floras: books that described the native plants of local regions. The invention of the

microscope

A microscope () is a laboratory equipment, laboratory instrument used to examine objects that are too small to be seen by the naked eye. Microscopy is the science of investigating small objects and structures using a microscope. Microscopic ...

stimulated the study of

plant anatomy

Plant anatomy or phytotomy is the general term for the study of the internal Anatomy, structure of plants. Originally, it included plant morphology, the description of the physical form and external structure of plants, but since the mid-20th centu ...

, and the first carefully designed experiments in

plant physiology

Plant physiology is a subdiscipline of botany concerned with the functioning, or physiology, of plants.

Plant physiologists study fundamental processes of plants, such as photosynthesis, respiration, plant nutrition, plant hormone functions, tr ...

were performed. With the expansion of trade and exploration beyond Europe, the many new plants being discovered were subjected to an increasingly rigorous process of

naming

Naming is assigning a name to something.

Naming may refer to:

* Naming (parliamentary procedure), a procedure in certain parliamentary bodies

* Naming ceremony, an event at which an infant is named

* Product naming, the discipline of deciding wha ...

, description, and

classification

Classification is the activity of assigning objects to some pre-existing classes or categories. This is distinct from the task of establishing the classes themselves (for example through cluster analysis). Examples include diagnostic tests, identif ...

.

Progressively more sophisticated scientific technology has aided the development of contemporary botanical offshoots in the plant sciences, ranging from the applied fields of

economic botany

Economic botany is the study of the relationship between people (individuals and cultures) and plants. Economic botany intersects many fields including established disciplines such as agronomy, anthropology, archaeology, chemistry, economics, ethn ...

(notably agriculture, horticulture and forestry), to the detailed examination of the structure and function of plants and their interaction with the environment over many scales from the large-scale global significance of vegetation and plant communities (

biogeography

Biogeography is the study of the species distribution, distribution of species and ecosystems in geography, geographic space and through evolutionary history of life, geological time. Organisms and biological community (ecology), communities o ...

and

ecology

Ecology () is the natural science of the relationships among living organisms and their Natural environment, environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community (ecology), community, ecosystem, and biosphere lev ...

) through to the small scale of subjects like

cell theory

In biology, cell theory is a scientific theory first formulated in the mid-nineteenth century, that living organisms are made up of cells, that they are the basic structural/organizational unit of all organisms, and that all cells come from pr ...

,

molecular biology

Molecular biology is a branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecule, molecular basis of biological activity in and between Cell (biology), cells, including biomolecule, biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactio ...

and plant

biochemistry

Biochemistry, or biological chemistry, is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology, a ...

.

Introduction

Botany

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

(

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

(') meaning "

pasture

Pasture (from the Latin ''pastus'', past participle of ''pascere'', "to feed") is land used for grazing.

Types of pasture

Pasture lands in the narrow sense are enclosed tracts of farmland, grazed by domesticated livestock, such as horses, c ...

", "

herb

Herbs are a widely distributed and widespread group of plants, excluding vegetables, with savory or aromatic properties that are used for flavoring and garnishing food, for medicinal purposes, or for fragrances. Culinary use typically distingu ...

s" "

grass

Poaceae ( ), also called Gramineae ( ), is a large and nearly ubiquitous family (biology), family of monocotyledonous flowering plants commonly known as grasses. It includes the cereal grasses, bamboos, the grasses of natural grassland and spe ...

", or "

fodder

Fodder (), also called provender (), is any agriculture, agricultural foodstuff used specifically to feed domesticated livestock, such as cattle, domestic rabbit, rabbits, sheep, horses, chickens and pigs. "Fodder" refers particularly to food ...

";

Medieval Latin

Medieval Latin was the form of Literary Latin used in Roman Catholic Church, Roman Catholic Western Europe during the Middle Ages. It was also the administrative language in the former Western Roman Empire, Roman Provinces of Mauretania, Numidi ...

' – herb, plant) and

zoology

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

are, historically, the core disciplines of

biology

Biology is the scientific study of life and living organisms. It is a broad natural science that encompasses a wide range of fields and unifying principles that explain the structure, function, growth, History of life, origin, evolution, and ...

whose history is closely associated with the natural sciences

chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

,

physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

and

geology

Geology (). is a branch of natural science concerned with the Earth and other astronomical objects, the rocks of which they are composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Earth ...

. A distinction can be made between botanical science in a pure sense, as the study of plants themselves, and botany as applied science, which studies the human use of plants. Early

natural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

divided pure botany into three main streams

morphology-

classification

Classification is the activity of assigning objects to some pre-existing classes or categories. This is distinct from the task of establishing the classes themselves (for example through cluster analysis). Examples include diagnostic tests, identif ...

,

anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of morphology concerned with the study of the internal structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old scien ...

and

physiology

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

– that is, external form, internal structure, and functional operation. The most obvious topics in applied botany are

horticulture

Horticulture (from ) is the art and science of growing fruits, vegetables, flowers, trees, shrubs and ornamental plants. Horticulture is commonly associated with the more professional and technical aspects of plant cultivation on a smaller and mo ...

,

forestry

Forestry is the science and craft of creating, managing, planting, using, conserving and repairing forests and woodlands for associated resources for human and Natural environment, environmental benefits. Forestry is practiced in plantations and ...

and

agriculture

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created ...

although there are many others like

weed science,

plant pathology

Plant pathology or phytopathology is the scientific study of plant diseases caused by pathogens (infectious organisms) and environmental conditions (physiological factors). Plant pathology involves the study of pathogen identification, disease ...

,

floristry

Floristry is the production, commerce, and trade in flowers. It encompasses flower care and handling, floral design, floral design and arrangement, merchandising, production, display and flower delivery. Wholesale florists sell bulk flowers ...

,

pharmacognosy,

economic botany

Economic botany is the study of the relationship between people (individuals and cultures) and plants. Economic botany intersects many fields including established disciplines such as agronomy, anthropology, archaeology, chemistry, economics, ethn ...

and

ethnobotany

Ethnobotany is an interdisciplinary field at the interface of natural and social sciences that studies the relationships between humans and plants. It focuses on traditional knowledge of how plants are used, managed, and perceived in human socie ...

which lie outside modern courses in botany. Since the origin of botanical science there has been a progressive increase in the scope of the subject as technology has opened up new techniques and areas of study. Modern

molecular systematics, for example, entails the principles and techniques of

taxonomy

image:Hierarchical clustering diagram.png, 280px, Generalized scheme of taxonomy

Taxonomy is a practice and science concerned with classification or categorization. Typically, there are two parts to it: the development of an underlying scheme o ...

,

molecular biology

Molecular biology is a branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecule, molecular basis of biological activity in and between Cell (biology), cells, including biomolecule, biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactio ...

,

computer science

Computer science is the study of computation, information, and automation. Computer science spans Theoretical computer science, theoretical disciplines (such as algorithms, theory of computation, and information theory) to Applied science, ...

and more.

Within botany, there are a number of sub-disciplines that focus on particular plant groups, each with their own range of related studies (anatomy, morphology etc.). Included here are:

phycology (

algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthesis, photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular ...

),

pteridology (

fern

The ferns (Polypodiopsida or Polypodiophyta) are a group of vascular plants (plants with xylem and phloem) that reproduce via spores and have neither seeds nor flowers. They differ from mosses by being vascular, i.e., having specialized tissue ...

s),

bryology (

moss

Mosses are small, non-vascular plant, non-vascular flowerless plants in the taxonomic phylum, division Bryophyta (, ) ''sensu stricto''. Bryophyta (''sensu lato'', Wilhelm Philippe Schimper, Schimp. 1879) may also refer to the parent group bryo ...

es and

liverworts

Liverworts are a group of non-vascular plant, non-vascular embryophyte, land plants forming the division Marchantiophyta (). They may also be referred to as hepatics. Like mosses and hornworts, they have a gametophyte-dominant life cycle, in wh ...

) and

palaeobotany (fossil plants) and their histories are treated elsewhere (see side bar). To this list can be added

mycology

Mycology is the branch of biology concerned with the study of fungus, fungi, including their Taxonomy (biology), taxonomy, genetics, biochemistry, biochemical properties, and ethnomycology, use by humans. Fungi can be a source of tinder, Edible ...

, the study of

fungi

A fungus (: fungi , , , or ; or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as one ...

, which were once treated as plants, but are now ranked as a unique kingdom.

Ancient knowledge

Nomad

Nomads are communities without fixed habitation who regularly move to and from areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the population of nomadic pa ...

ic

hunter-gatherer

A hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living in a community, or according to an ancestrally derived Lifestyle, lifestyle, in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local naturally occurring sources, esp ...

societies passed on, by

oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication in which knowledge, art, ideas and culture are received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another.Jan Vansina, Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (19 ...

, what they knew (their empirical observations) about the different kinds of plants that they used for food, shelter, poisons, medicines, for ceremonies and rituals etc. The uses of plants by these pre-literate societies influenced the way the plants were named and classified—their uses were embedded in

folk-taxonomies, the way they were grouped according to use in everyday communication. The nomadic life-style was drastically changed when settled communities were established in about twelve centres around the world during the

Neolithic Revolution

The Neolithic Revolution, also known as the First Agricultural Revolution, was the wide-scale transition of many human cultures during the Neolithic period in Afro-Eurasia from a lifestyle of hunter-gatherer, hunting and gathering to one of a ...

which extended from about 10,000 to 2500 years ago depending on the region. With these communities came the development of the technology and skills needed for the

domestication of plants and animals and the emergence of the written word provided evidence for the passing of systematic knowledge and culture from one generation to the next.

Plant lore and plant selection

During the Neolithic Revolution, plant knowledge increased most obviously through the use of plants for food and medicine. All of today's

staple food

A staple food, food staple, or simply staple, is a food that is eaten often and in such quantities that it constitutes a dominant portion of a standard diet for an individual or a population group, supplying a large fraction of energy needs an ...

s were domesticated in

prehistoric

Prehistory, also called pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the first known use of stone tools by hominins million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use o ...

times as a gradual process of selection of higher-yielding varieties took place, possibly unknowingly, over hundreds to thousands of years.

Legume

Legumes are plants in the pea family Fabaceae (or Leguminosae), or the fruit or seeds of such plants. When used as a dry grain for human consumption, the seeds are also called pulses. Legumes are grown agriculturally, primarily for human consum ...

s were cultivated on all continents but cereals made up most of the regular diet:

rice

Rice is a cereal grain and in its Domestication, domesticated form is the staple food of over half of the world's population, particularly in Asia and Africa. Rice is the seed of the grass species ''Oryza sativa'' (Asian rice)—or, much l ...

in East Asia,

wheat

Wheat is a group of wild and crop domestication, domesticated Poaceae, grasses of the genus ''Triticum'' (). They are Agriculture, cultivated for their cereal grains, which are staple foods around the world. Well-known Taxonomy of wheat, whe ...

and

barley

Barley (), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains; it was domesticated in the Fertile Crescent around 9000 BC, giving it nonshattering spikele ...

in the Middle east, and

maize

Maize (; ''Zea mays''), also known as corn in North American English, is a tall stout grass that produces cereal grain. It was domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 9,000 years ago from wild teosinte. Native American ...

in Central and South America. By Greco-Roman times, popular food plants of today, including

grape

A grape is a fruit, botanically a berry, of the deciduous woody vines of the flowering plant genus ''Vitis''. Grapes are a non- climacteric type of fruit, generally occurring in clusters.

The cultivation of grapes began approximately 8,0 ...

s,

apple

An apple is a round, edible fruit produced by an apple tree (''Malus'' spp.). Fruit trees of the orchard or domestic apple (''Malus domestica''), the most widely grown in the genus, are agriculture, cultivated worldwide. The tree originated ...

s,

figs, and

olive

The olive, botanical name ''Olea europaea'' ("European olive"), is a species of Subtropics, subtropical evergreen tree in the Family (biology), family Oleaceae. Originating in Anatolia, Asia Minor, it is abundant throughout the Mediterranean ...

s, were being listed as named varieties in early manuscripts. Botanical authority

William Stearn has observed that "''cultivated plants are mankind's most vital and precious heritage from remote antiquity''".

It is also from the Neolithic, in about 3000 BC, that we glimpse the first known illustrations of plants and read descriptions of impressive gardens in Egypt. However protobotany, the first pre-scientific written record of plants, did not begin with food; it was born out of the medicinal literature of

Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

,

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

,

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

and

India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

. Botanical historian Alan Morton notes that agriculture was the occupation of the poor and uneducated, while medicine was the realm of socially influential

shaman

Shamanism is a spiritual practice that involves a practitioner (shaman) interacting with the spirit world through altered states of consciousness, such as trance. The goal of this is usually to direct spirits or spiritual energies into ...

s,

priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deity, deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in parti ...

s,

apothecaries

''Apothecary'' () is an archaic English term for a medical professional who formulates and dispenses '' materia medica'' (medicine) to physicians, surgeons and patients. The modern terms ''pharmacist'' and, in British English, ''chemist'' have ...

,

magicians and

physician

A physician, medical practitioner (British English), medical doctor, or simply doctor is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through the Medical education, study, Med ...

s, who were more likely to record their knowledge for posterity.

Early botany

Ancient India

Early Indian texts, like the

Vedas

FIle:Atharva-Veda samhita page 471 illustration.png, upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the ''Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas ( or ; ), sometimes collectively called the Veda, are a large body of relig ...

mention plants with magical properties. The

Sushruta Samhita, describes over 700 plants used for medicinal purposes. This text reflects a level of medical knowledge and practice comparable to

ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

. Notably, the Sushruta Samhita categorizes food plants based on their utilized parts, taste, and dietary effects. While lacking detailed botanical descriptions beyond occasional habitat or foliage references, the text demonstrates close observation of plants. This is evident in the classification of sugarcane varieties and the listing of fungi based on their growth medium. The

Charaka Samhitā, foundational Ayurvedic text, presents the earliest known plant classification system in India, using habitat, presence of flowers/fruits, and reproduction as criteria.

Classical antiquity

Classical Greece

Ancient Athens, of the 6th century BC, was the busy trade centre at the confluence of

Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

ian,

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

n and

Minoan cultures at the height of Greek colonisation of the Mediterranean. The philosophical thought of this period ranged freely through many subjects.

Empedocles

Empedocles (; ; , 444–443 BC) was a Ancient Greece, Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is known best for originating the Cosmogony, cosmogonic theory of the four cla ...

(490–430 BC) foreshadowed Darwinian evolutionary theory in a crude formulation of the mutability of species and

natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

. The physician

Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; ; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician and philosopher of the Classical Greece, classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history of medicine. He is traditionally referr ...

(460–370 BC) avoided the prevailing superstition of his day and approached healing by close observation and the test of experience. At this time, a genuine non-

anthropocentric

Anthropocentrism ( ) is the belief that human beings are the central or most important entity on the planet. The term can be used interchangeably with humanocentrism, and some refer to the concept as human supremacy or human exceptionalism. From a ...

curiosity about plants emerged. The major works written about plants extended beyond the description of their medicinal uses to the topics of plant geography, morphology, physiology, nutrition, growth and reproduction.

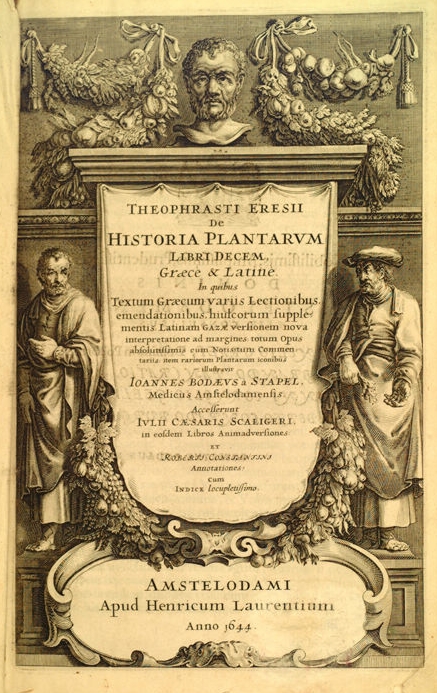

Theophrastus and the origin of botanical science

Foremost among the scholars studying botany was

Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; ; c. 371 – c. 287 BC) was an ancient Greek Philosophy, philosopher and Natural history, naturalist. A native of Eresos in Lesbos, he was Aristotle's close colleague and successor as head of the Lyceum (classical), Lyceum, the ...

of Eressus (

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

: ; –287 BC) who has been frequently referred to as the "Father of Botany". He was a student and close friend of

Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

(384–322 BC) and succeeded him as head of the

Lyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies among countries; usually it is a type of secondary school. Basic science and some introduction to ...

(an educational establishment like a modern university) in Athens with its tradition of

peripatetic philosophy. Aristotle's special treatise on plants — — is now lost, although there are many botanical observations scattered throughout his other writings (these have been assembled by

Christian Wimmer in ', 1836) but they give little insight into his botanical thinking. The Lyceum prided itself in a tradition of systematic observation of causal connections, critical experiment and rational theorizing. Theophrastus challenged the superstitious medicine employed by the physicians of his day, called rhizotomi, and also the control over medicine exerted by priestly authority and tradition. Together with Aristotle, he had tutored

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

whose military conquests were carried out with all the scientific resources of the day, the Lyceum garden probably containing many botanical trophies collected during his campaigns as well as other explorations in distant lands. It was in this garden where he gained much of his plant knowledge.

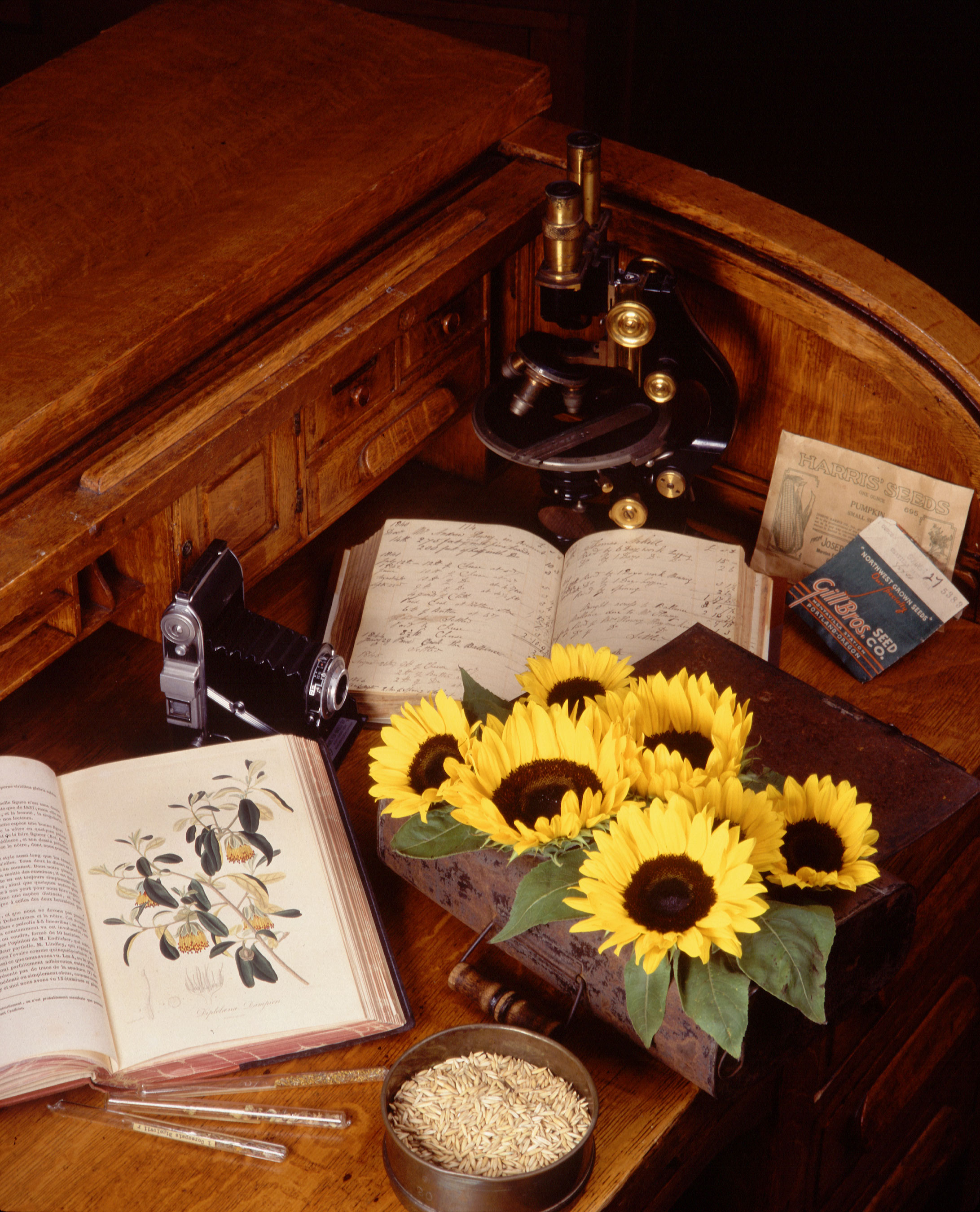

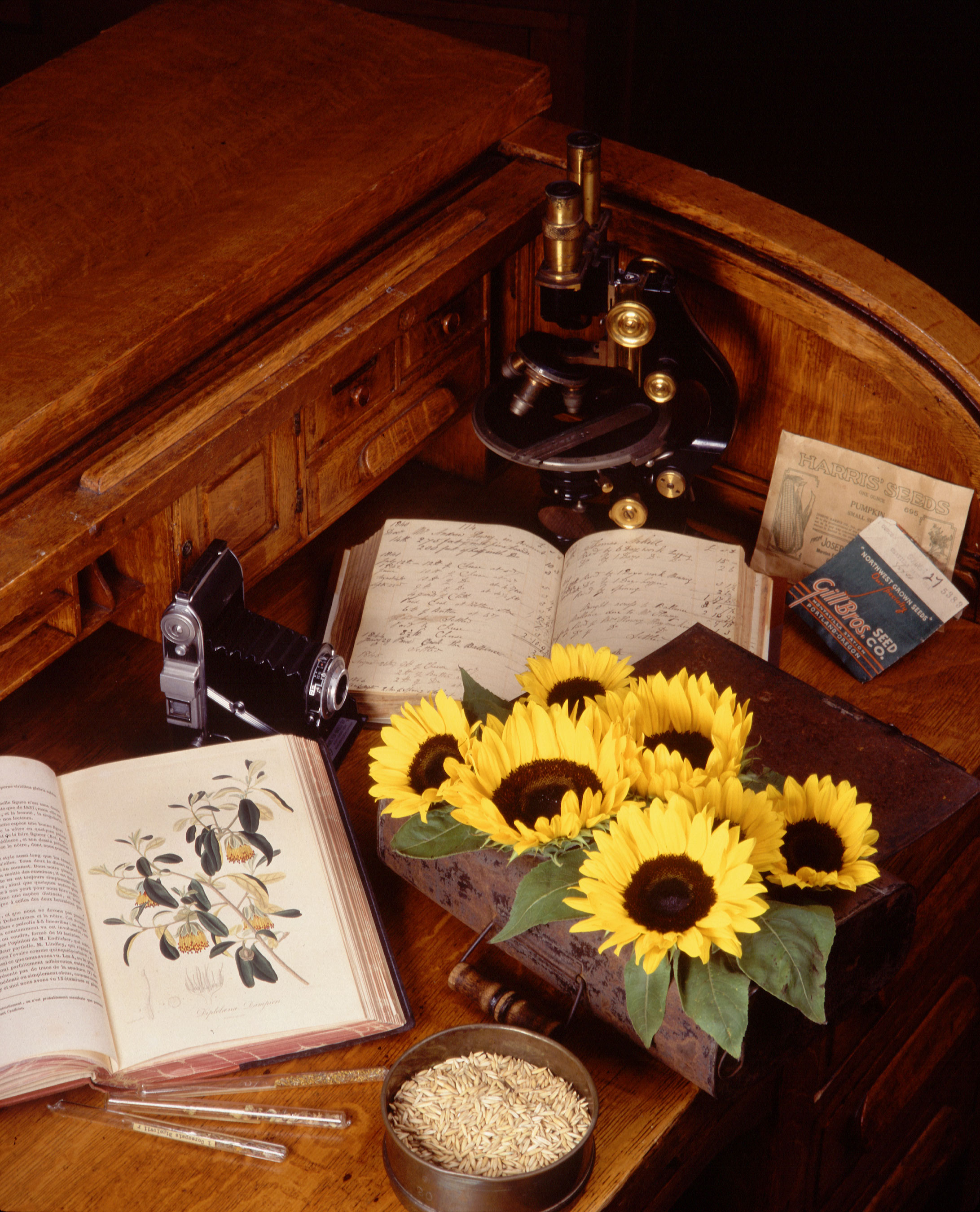

= ''Enquiry into Plants'' and ''Causes of Plants''

=

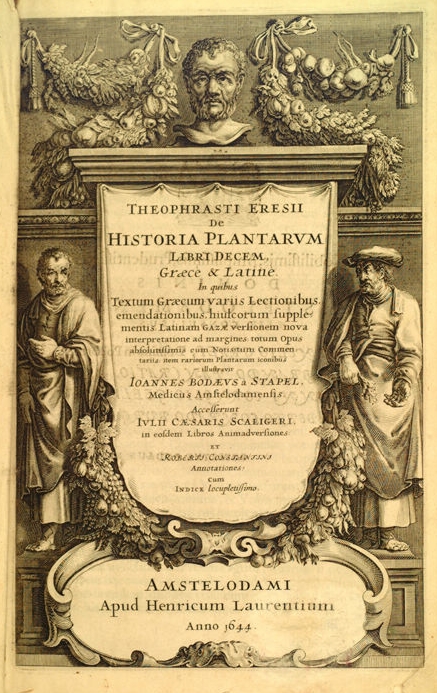

Theophrastus's major botanical works were the ''

Enquiry into Plants'' (''Historia Plantarum'') and ''Causes of Plants'' (''Causae Plantarum'') which were his lecture notes for the Lyceum. The opening sentence of the ''Enquiry'' reads like a botanical

manifesto

A manifesto is a written declaration of the intentions, motives, or views of the issuer, be it an individual, group, political party, or government. A manifesto can accept a previously published opinion or public consensus, but many prominent ...

:

The ''Enquiry'' is 9 books of "applied" botany dealing with the forms and

classification

Classification is the activity of assigning objects to some pre-existing classes or categories. This is distinct from the task of establishing the classes themselves (for example through cluster analysis). Examples include diagnostic tests, identif ...

of plants and

economic botany

Economic botany is the study of the relationship between people (individuals and cultures) and plants. Economic botany intersects many fields including established disciplines such as agronomy, anthropology, archaeology, chemistry, economics, ethn ...

, examining the techniques of

agriculture

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created ...

(relationship of crops to soil, climate, water and habitat) and

horticulture

Horticulture (from ) is the art and science of growing fruits, vegetables, flowers, trees, shrubs and ornamental plants. Horticulture is commonly associated with the more professional and technical aspects of plant cultivation on a smaller and mo ...

. He described some 500 plants in detail, often including descriptions of habitat and geographic distribution, and he recognised some plant groups that can be recognised as modern-day plant families. Some names he used, like ''

Crataegus

''Crataegus'' (), commonly called hawthorn, quickthorn, thornapple, Voss, E. G. 1985. ''Michigan Flora: A guide to the identification and occurrence of the native and naturalized seed-plants of the state. Part II: Dicots (Saururaceae–Cornacea ...

'', ''

Daucus'' and ''

Asparagus

Asparagus (''Asparagus officinalis'') is a perennial flowering plant species in the genus ''Asparagus (genus), Asparagus'' native to Eurasia. Widely cultivated as a vegetable crop, its young shoots are used as a spring vegetable.

Description ...

'' have persisted until today. His second book ''Causes of Plants'' covers plant growth and reproduction (akin to modern physiology). Like Aristotle, he grouped plants into "trees", "undershrubs", "shrubs" and "herbs" but he also made several other important botanical distinctions and observations. He noted that plants could be

annuals,

perennial

In horticulture, the term perennial ('' per-'' + '' -ennial'', "through the year") is used to differentiate a plant from shorter-lived annuals and biennials. It has thus been defined as a plant that lives more than 2 years. The term is also ...

s and

biennials, they were also either

monocotyledon

Monocotyledons (), commonly referred to as monocots, ( Lilianae '' sensu'' Chase & Reveal) are flowering plants whose seeds contain only one embryonic leaf, or cotyledon. A monocot taxon has been in use for several decades, but with various ranks ...

s or

dicotyledon

The dicotyledons, also known as dicots (or, more rarely, dicotyls), are one of the two groups into which all the flowering plants (angiosperms) were formerly divided. The name refers to one of the typical characteristics of the group: namely, ...

s and he also noticed the difference between

determinate and indeterminate growth and details of floral structure including the degree of fusion of the petals, position of the ovary and more. These lecture notes of Theophrastus comprise the first clear exposition of the rudiments of plant anatomy, physiology, morphology and ecology — presented in a way that would not be matched for another eighteen centuries.

Pedanius Dioscorides

A full synthesis of ancient Greek pharmacology was compiled in

''De'' ''Materia Medica'' c. 60 AD by

Pedanius Dioscorides

Pedanius Dioscorides (, ; 40–90 AD), "the father of pharmacognosy", was a Greek physician, pharmacologist, botanist, and author of (in the original , , both meaning "On Medical Material") , a 5-volume Greek encyclopedic pharmacopeia on he ...

(c. 40-90 AD) who was a Greek physician with the Roman army. This work proved to be the definitive text on medicinal herbs, both oriental and occidental, for fifteen hundred years until the dawn of the European

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

being slavishly copied again and again throughout this period. Though rich in medicinal information with descriptions of about 600 medicinal herbs, the botanical content of the work was extremely limited.

Ancient Rome

The Romans contributed little to the foundations of botanical science laid by the ancient Greeks, but made a sound contribution to our knowledge of applied botany as agriculture. In works titled ', four Roman writers contributed to a compendium ''Scriptores Rei Rusticae'', published from the Renaissance on, which set out the principles and practice of agriculture. These authors were

Cato (234–149 BC),

Varro

Marcus Terentius Varro (116–27 BCE) was a Roman polymath and a prolific author. He is regarded as ancient Rome's greatest scholar, and was described by Petrarch as "the third great light of Rome" (after Virgil and Cicero). He is sometimes call ...

(116–27 BC) and, in particular,

Columella

Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella (, Arabic: ) was a prominent Roman writer on agriculture in the Roman Empire.

His in twelve volumes has been completely preserved and forms an important source on Roman agriculture and ancient Roman cuisin ...

(4–70 AD) and

Palladius (4th century AD).

= Pliny the Elder

=

Roman encyclopaedist

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

(23–79 AD) deals with plants in Books 12 to 26 of his 37-volume highly influential work ' in which he frequently quotes Theophrastus but with a lack of botanical insight although he does, nevertheless, draw a distinction between true botany on the one hand, and farming and medicine on the other. It is estimated that at the time of the Roman Empire between 1300 and 1400 plants had been recorded in the West.

Ancient China

In

ancient China

The history of China spans several millennia across a wide geographical area. Each region now considered part of the Chinese world has experienced periods of unity, fracture, prosperity, and strife. Chinese civilization first emerged in the Y ...

, lists of different plants and herb concoctions for

pharmaceutical

Medication (also called medicament, medicine, pharmaceutical drug, medicinal product, medicinal drug or simply drug) is a drug used to diagnose, cure, treat, or prevent disease. Drug therapy ( pharmacotherapy) is an important part of the ...

purposes date back to at least the time of the

Warring States

The Warring States period in Chinese history (221 BC) comprises the final two and a half centuries of the Zhou dynasty (256 BC), which were characterized by frequent warfare, bureaucratic and military reforms, and struggles for gre ...

(481 BC-221 BC). Many Chinese writers over the centuries contributed to the written knowledge of herbal pharmaceutics. The Chinese dictionary-encyclopaedia ''

Erh Ya'' probably dates from about 300 BC and describes about 334 plants classed as trees or shrubs, each with a common name and illustration. The

Han Dynasty

The Han dynasty was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC9 AD, 25–220 AD) established by Liu Bang and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–206 BC ...

(202 BC-220 AD) includes the notable work of the

Huangdi Neijing

' (), literally the ''Inner Canon of the Yellow Emperor'' or ''Esoteric Scripture of the Yellow Emperor'', is an ancient Chinese medical text or group of texts that has been treated as a fundamental doctrinal source for Chinese medicine for mo ...

and the famous pharmacologist

Zhang Zhongjing

Zhang Zhongjing (; 150–219), formal name Zhang Ji (), was a Chinese pharmacologist, physician, inventor, and writer of the Eastern Han dynasty and one of the most eminent Chinese physicians during the later years of the Han dynasty. He estab ...

.

Medieval knowledge

Medicinal plants of the early Middle Ages

In Western Europe, after Theophrastus, botany passed through a bleak period of 1800 years when little progress was made and, indeed, many of the early insights were lost. As Europe entered the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

(5th to 15th centuries), China, India and the Arab world enjoyed a golden age.

Medieval China

Chinese philosophy had followed a similar path to that of the ancient Greeks. Between 100 and 1700 AD, many new works on pharmaceutical botany were produced. The 11th century scientists and statesmen

Su Song and

Shen Kuo

Shen Kuo (; 1031–1095) or Shen Gua, courtesy name Cunzhong (存中) and Art name#China, pseudonym Mengqi (now usually given as Mengxi) Weng (夢溪翁),Yao (2003), 544. was a Chinese polymath, scientist, and statesman of the Song dynasty (960� ...

compiled learned treatises on natural history, emphasising herbal medicine. Among the pharmaceutical botany works were encyclopaedic accounts and treatises compiled for the Chinese imperial court. These were free of superstition and myth with carefully researched descriptions and nomenclature; they included cultivation information and notes on economic and medicinal uses — and even elaborate monographs on ornamental plants. But there was no experimental method and no analysis of the plant sexual system, nutrition, or anatomy.

Medieval India

In India, simple artificial plant classification became more botanical with the work of

Parashara (c. 400 – c. 500 AD), the author of ''Vṛksayurveda'' (the science of life of trees). He made close observations of leaves and divided plants into Dvimatrka (

Dicotyledon

The dicotyledons, also known as dicots (or, more rarely, dicotyls), are one of the two groups into which all the flowering plants (angiosperms) were formerly divided. The name refers to one of the typical characteristics of the group: namely, ...

s) and Ekamatrka (

Monocotyledon

Monocotyledons (), commonly referred to as monocots, ( Lilianae '' sensu'' Chase & Reveal) are flowering plants whose seeds contain only one embryonic leaf, or cotyledon. A monocot taxon has been in use for several decades, but with various ranks ...

s). Important medieval Indian works of plant physiology include the ''Prthviniraparyam'' of

Udayana, ''Nyayavindutika'' of Dharmottara, ''Saddarsana-samuccaya'' of Gunaratna, and ''Upaskara'' of Sankaramisra.

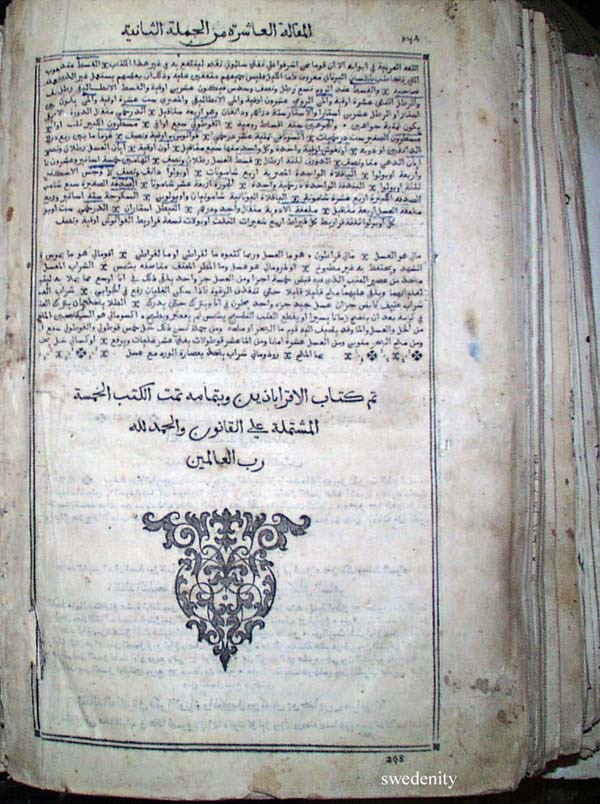

Islamic Golden Age

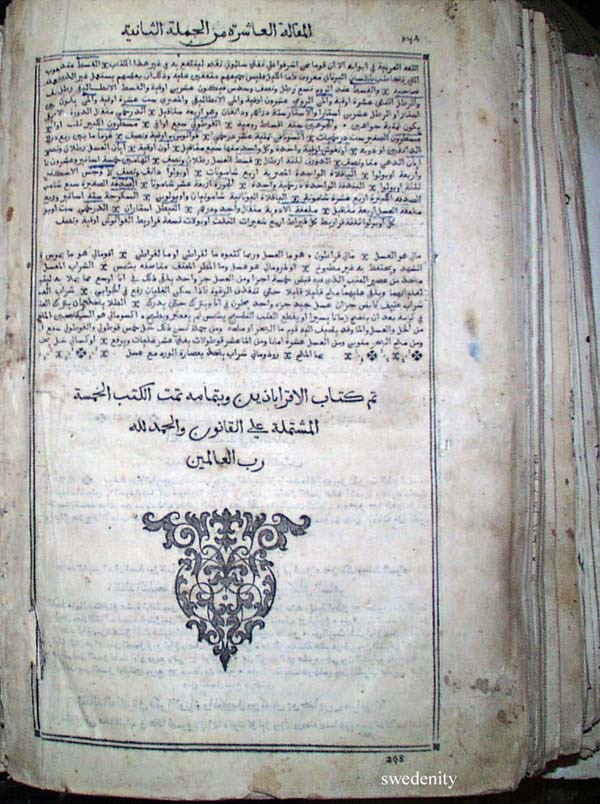

The 400-year period from the 9th to 13th centuries AD was the

Islamic Renaissance, a time when Islamic culture and science thrived. Greco-Roman texts were preserved, copied and extended although new texts always emphasised the medicinal aspects of plants.

Kurd

Kurds (), or the Kurdish people, are an Iranian peoples, Iranic ethnic group from West Asia. They are indigenous to Kurdistan, which is a geographic region spanning southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, and northeastern Syri ...

ish biologist

Ābu Ḥanīfah Āḥmad ibn Dawūd Dīnawarī (828–896 AD) is known as the founder of Arabic botany; his ''Kitâb al-nabât'' ('Book of Plants') describes 637 species, discussing plant development from germination to senescence and including details of flowers and fruits. The

Mutazilite philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

and physician

Ibn Sina

Ibn Sina ( – 22 June 1037), commonly known in the West as Avicenna ( ), was a preeminent philosopher and physician of the Muslim world, flourishing during the Islamic Golden Age, serving in the courts of various Iranian peoples, Iranian ...

(

Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( – 22 June 1037), commonly known in the West as Avicenna ( ), was a preeminent philosopher and physician of the Muslim world, flourishing during the Islamic Golden Age, serving in the courts of various Iranian peoples, Iranian ...

) (c. 980–1037 AD) was another influential figure, his ''

The Canon of Medicine

''The Canon of Medicine'' () is an encyclopedia of medicine in five books compiled by Avicenna (, ibn Sina) and completed in 1025. It is among the most influential works of its time. It presents an overview of the contemporary medical knowle ...

'' being a landmark in the history of medicine treasured until the

Enlightenment.

The Silk Road

Following the

fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city was captured on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 55-da ...

(1453), the newly expanded

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

welcomed European embassies in its capital, which in turn became the sources of plants from those regions to the east which traded with the empire. In the following century, twenty times as many plants entered Europe along the

Silk Road

The Silk Road was a network of Asian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over , it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and religious interactions between the ...

as had been transported in the previous two thousand years, mainly as bulbs. Others were acquired primarily for their alleged medicinal value. Initially, Italy benefited from this new knowledge, especially

Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

, which traded extensively with the East. From there, these new plants rapidly spread to the rest of Western Europe.

[ By the middle of the sixteenth century, there was already a flourishing export trade of various bulbs from Turkey to Europe.

]

The Age of Herbals

In the European

In the European Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

of the 15th and 16th centuries, the lives of European citizens were based around agriculture but when printing arrived, with movable type and woodcut

Woodcut is a relief printing technique in printmaking. An artist carves an image into the surface of a block of wood—typically with gouges—leaving the printing parts level with the surface while removing the non-printing parts. Areas that ...

illustrations, it was not treatises on agriculture that were published, but lists of medicinal plants with descriptions of their properties or "virtues". These first plant books, known as herbal

A herbal is a book containing the names and descriptions of plants, usually with information on their medicinal, Herbal tonic, tonic, culinary, toxic, hallucinatory, aromatic, or Magic (paranormal), magical powers, and the legends associated wi ...

s showed that botany was still a part of medicine, as it had been for most of ancient history.De Materia Medica

(Latin name for the Greek work , , both meaning "On Medical Material") is a pharmacopoeia of medicinal plants and the medicines that can be obtained from them. The five-volume work was written between 50 and 70 CE by Pedanius Dioscorides, ...

''.

However, the need for accurate and detailed plant descriptions meant that some herbals were more botanical than medicinal.

However, the need for accurate and detailed plant descriptions meant that some herbals were more botanical than medicinal.

German Otto Brunfels's (1464–1534) ''Herbarum Vivae Icones'' (1530) contained descriptions of about 47 species new to science combined with accurate illustrations. His fellow countryman Hieronymus Bock's (1498–1554) ''Kreutterbuch'' of 1539 described plants he found in nearby woods and fields and these were illustrated in the 1546 edition.

German Otto Brunfels's (1464–1534) ''Herbarum Vivae Icones'' (1530) contained descriptions of about 47 species new to science combined with accurate illustrations. His fellow countryman Hieronymus Bock's (1498–1554) ''Kreutterbuch'' of 1539 described plants he found in nearby woods and fields and these were illustrated in the 1546 edition.ovary

The ovary () is a gonad in the female reproductive system that produces ova; when released, an ovum travels through the fallopian tube/ oviduct into the uterus. There is an ovary on the left and the right side of the body. The ovaries are end ...

, and the type of ovule

In seed plants, the ovule is the structure that gives rise to and contains the female reproductive cells. It consists of three parts: the ''integument'', forming its outer layer, the ''nucellus'' (or remnant of the sporangium, megasporangium), ...

placentation

Placentation is the formation, type and structure, or modes of arrangement of the placenta. The function of placentation is to transfer nutrients, respiratory gases, and water from maternal tissue to a growing embryo, and in some instances to re ...

. He also made observations on pollen and distinguished between inflorescence

In botany, an inflorescence is a group or cluster of flowers arranged on a plant's Plant stem, stem that is composed of a main branch or a system of branches. An inflorescence is categorized on the basis of the arrangement of flowers on a mai ...

types.Flora

Flora (: floras or florae) is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring (indigenous (ecology), indigenous) native plant, native plants. The corresponding term for animals is ''fauna'', and for f ...

s. These were often backed by specimens deposited in a herbarium

A herbarium (plural: herbaria) is a collection of preserved plant biological specimen, specimens and associated data used for scientific study.

The specimens may be whole plants or plant parts; these will usually be in dried form mounted on a sh ...

which was a collection of dried plants that verified the plant descriptions given in the Floras. The transition from herbal to Flora marked the final separation of botany from medicine.

The Renaissance and Age of Enlightenment (1550–1800)

The revival of learning during the European

The revival of learning during the European Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

renewed interest in plants. The church, feudal aristocracy and an increasingly influential merchant class that supported science and the arts, now jostled in a world of increasing trade. Sea voyages of exploration returned botanical treasures to the large public, private, and newly established botanic gardens, and introduced an eager population to novel crops, drugs and spices from Asia, the East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies) is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The ''Indies'' broadly referred to various lands in Eastern world, the East or the Eastern Hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainl ...

and the New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

.

The number of scientific publications increased. In England, for example, scientific communication and causes were facilitated by learned societies like Royal Society (founded in 1660) and the Linnaean Society (founded in 1788): there was also the support and activities of botanical institutions like the Jardin du Roi

The Jardin des Plantes (, ), also known as the Jardin des Plantes de Paris () when distinguished from other ''jardins des plantes'' in other cities, is the main botanical garden in France. Jardin des Plantes is the official name in the present da ...

in Paris, Chelsea Physic Garden

The Chelsea Physic Garden was established as the Apothecaries' Garden in London, England, in 1673 by the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries to grow plants to be used as medicines. This four acre physic garden, the term here referring to the scie ...

, Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, and the Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

and Cambridge Botanic Gardens, as well as the influence of renowned private gardens and wealthy entrepreneurial nurserymen. By the early 17th century the number of plants described in Europe had risen to about 6000. The 18th century Enlightenment values of reason and science coupled with new voyages to distant lands instigating another phase of encyclopaedic plant identification, nomenclature, description and illustration, "flower painting" possibly at its best in this period of history. Plant trophies from distant lands decorated the gardens of Europe's powerful and wealthy in a period of enthusiasm for natural history, especially botany (a preoccupation sometimes referred to as "botanophilia") that is never likely to recur. Often such exotic new plant imports (primarily from Turkey), when they first appeared in print in English, lacked common names in the language.

During the 18th century, botany was one of the few sciences considered appropriate for genteel educated women. Around 1760, with the popularization of the Linnaean system, botany became much more widespread among educated women who painted plants, attended classes on plant classification, and collected herbarium specimens although emphasis was on the healing properties of plants rather than plant reproduction which had overtones of sexuality. Women began publishing on botanical topics and children's books on botany appeared by authors like Charlotte Turner Smith. Cultural authorities argued that education through botany created culturally and scientifically aware citizens, part of the thrust for 'improvement' that characterised the Enlightenment. However, in the early 19th century with the recognition of botany as an official science, women were again excluded from the discipline. Compared to other sciences, however, in botany the number of female researchers, collectors, or illustrators has always been remarkably high.

Botanical gardens and herbaria

Public and private gardens have always been strongly associated with the historical unfolding of botanical science.

Public and private gardens have always been strongly associated with the historical unfolding of botanical science.Pisa

Pisa ( ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Tuscany, Central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for the Leaning Tow ...

(1544), founded by Luca Ghini (1490–1556). Although part of a medical faculty, the first chair of ', essentially a chair in botany, was established in Padua in 1533. Then in 1534, Ghini became Reader in ' at Bologna University, where Ulisse Aldrovandi established a similar garden in 1568 (see below). Collections of pressed and dried specimens were called a ' (garden of dry plants) and the first accumulation of plants in this way (including the use of a plant press) is attributed to Ghini. Buildings called herbaria housed these specimens mounted on card with descriptive labels. Stored in cupboards in systematic order, they could be preserved in perpetuity and easily transferred or exchanged with other institutions, a taxonomic procedure that is still used today.

By the 18th century, the physic gardens had been transformed into "order beds" that demonstrated the classification systems that were being devised by botanists of the day — but they also had to accommodate the influx of curious, beautiful and new plants pouring in from voyages of exploration that were associated with European colonial expansion.

From Herbal to Flora

Plant classification systems of the 17th and 18th centuries now related plants to one another and not to man, marking a return to the non-anthropocentric botanical science promoted by Theophrastus over 1500 years before. In England, various herbals in either Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

or English were mainly compilations and translations of continental European works, of limited relevance to the British Isles. This included the rather unreliable work of Gerard

Gerard is a masculine forename of Proto-Germanic language, Proto-Germanic origin, variations of which exist in many Germanic and Romance languages. Like many other Germanic name, early Germanic names, it is dithematic, consisting of two meaningful ...

(1597). The first systematic attempt to collect information on British plants was that of Thomas Johnson (1629), who was later to issue his own revision of Gerard's work (1633–1636).

However, Johnson was not the first apothecary or physician to organise botanical expeditions to systematise their local flora. In Italy, Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522 – 1605) organised an expedition to the Sibylline mountains in Umbria

Umbria ( ; ) is a Regions of Italy, region of central Italy. It includes Lake Trasimeno and Cascata delle Marmore, Marmore Falls, and is crossed by the Tiber. It is the only landlocked region on the Italian Peninsula, Apennine Peninsula. The re ...

in 1557, and compiled a local Flora

Flora (: floras or florae) is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring (indigenous (ecology), indigenous) native plant, native plants. The corresponding term for animals is ''fauna'', and for f ...

. He then began to disseminate his findings amongst other European scholars, forming an early network of knowledge sharing

Knowledge sharing is an activity through which knowledge (namely, information, skills, or expertise) is exchanged among people, friends, peers, families, communities (for example, Wikipedia), or within or between organizations. It bridges the ind ...

"''molti amici in molti luoghi''" (many friends in many places), including Charles de l'Écluse ( Clusius) (1526 – 1609) at Montpellier

Montpellier (; ) is a city in southern France near the Mediterranean Sea. One of the largest urban centres in the region of Occitania (administrative region), Occitania, Montpellier is the prefecture of the Departments of France, department of ...

and Jean de Brancion at Malines. Between them, they started developing Latin names for plants, in addition to their common names. The exchange of information and specimens between scholars was often associated with the founding of botanical gardens (above), and to this end Aldrovandi founded one of the earliest at his university in Bologna

Bologna ( , , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy. It is the List of cities in Italy, seventh most populous city in Italy, with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nationalities. Its M ...

, the Orto Botanico di Bologna in 1568.

In France, Clusius journeyed throughout most of Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

, making discoveries in the vegetable kingdom along the way. He compiled Flora of Spain (1576), and Austria and Hungary (1583). He was the first to propose dividing plants into classes.Conrad Gessner

Conrad Gessner (; ; 26 March 1516 – 13 December 1565) was a Swiss physician, naturalist, bibliographer, and philologist. Born into a poor family in Zürich, Switzerland, his father and teachers quickly realised his talents and supported him t ...

(1516 – 1565) made regular explorations of the Swiss Alps

The Alps, Alpine region of Switzerland, conventionally referred to as the Swiss Alps, represents a major natural feature of the country and is, along with the Swiss Plateau and the Swiss portion of the Jura Mountains, one of its three main Physica ...

from his native Zurich

Zurich (; ) is the list of cities in Switzerland, largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zurich. It is in north-central Switzerland, at the northwestern tip of Lake Zurich. , the municipality had 448,664 inhabitants. The ...

and discovered many new plants. He proposed that there were groups or genera of plants. He said that each genus was composed of many species and that these were defined by similar flowers and fruits. This principle of organization laid the groundwork for future botanists. He wrote his important '' Historia Plantarum'' shortly before his death. At Malines, in Flanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

he established and maintained the botanical gardens of Jean de Brancion from 1568 to 1573, and first encountered tulips.

This approach coupled with the new Linnaean system of binomial nomenclature

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, both of which use Latin grammatical forms, altho ...

resulted in plant encyclopaedias without medicinal information called ''Floras'' that meticulously described and illustrated the plants growing in particular regions. The 17th century also marked the beginning of experimental botany and application of a rigorous scientific method, while improvements in the microscope launched the new discipline of plant anatomy whose foundations, laid by the careful observations of Englishman Nehemiah Grew

Nehemiah Grew (26 September 164125 March 1712) was an English plant anatomist and physiologist, known as the "Father of Plant Anatomy".

Biography

Grew was the only son of Obadiah Grew (1607–1688), Nonconformist divine and vicar of St Mi ...

and Italian Marcello Malpighi

Marcello Malpighi (10 March 1628 – 30 November 1694) was an Italians, Italian biologist and physician, who is referred to as the "founder of microscopical anatomy, histology and father of physiology and embryology". Malpighi's name is borne by ...

, would last for 150 years.

Botanical exploration

More new lands were opening up to European colonial powers, the botanical riches being returned to European botanists for description. This was a romantic era of botanical explorers, intrepid plant hunters and gardener-botanists. Significant botanical collections came from: the West Indies (Hans Sloane

Sir Hans Sloane, 1st Baronet, (16 April 1660 – 11 January 1753), was an Irish physician, naturalist, and collector. He had a collection of 71,000 items which he bequeathed to the British nation, thus providing the foundation of the British ...

(1660–1753)); China ( James Cunningham); the spice islands of the East Indies (Moluccas, George Rumphius (1627–1702)); China and Mozambique (João de Loureiro

João de Loureiro (1717, Lisbon – 18 October 1791) was a Portuguese people, Portuguese Jesuit missionary and botanist.

Biography

After receiving admission to the Jesuit Order, João de Loureiro served as a missionary in Goa, capital of Port ...

(1717–1791)); West Africa ( Michel Adanson (1727–1806)) who devised his own classification scheme and forwarded a crude theory of the mutability of species; Canada, Hebrides, Iceland, New Zealand by Captain James Cook's chief botanist Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English Natural history, naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the European and American voyages of scientific exploration, 1766 natural-history ...

(1743–1820).

Classification and morphology

By the middle of the 18th century, the botanical booty resulting from the era of exploration was accumulating in gardens and herbaria – and it needed to be systematically catalogued. This was the task of the taxonomists, the plant classifiers.

Plant classifications have changed over time from "artificial" systems based on general habit and form, to pre-evolutionary "natural" systems expressing similarity using one to many characters, leading to post-evolutionary "natural" systems that use characters to infer evolutionary relationships.

Italian physician Andrea Caesalpino (1519–1603) studied medicine and taught botany at the University of Pisa for about 40 years eventually becoming Director of the Botanic Garden of Pisa from 1554 to 1558. His sixteen-volume ''De Plantis'' (1583) described 1500 plants and his herbarium

A herbarium (plural: herbaria) is a collection of preserved plant biological specimen, specimens and associated data used for scientific study.

The specimens may be whole plants or plant parts; these will usually be in dried form mounted on a sh ...

of 260 pages and 768 mounted specimens still remains. Caesalpino proposed classes based largely on the detailed structure of the flowers and fruit;Gaspard Bauhin

Gaspard Bauhin or Caspar Bauhin (; 17 January 1560 – 5 December 1624), was a Switzerland, Swiss botanist whose ''Pinax theatri botanici'' (1623) described thousands of plants and classified them in a manner that draws comparisons to the later ...

(1560–1624) produced two influential publications ' (1620) and ' (1623). These brought order to the 6000 species now described and in the latter he used binomials and synonyms that may well have influenced Linnaeus's thinking. He also insisted that taxonomy should be based on natural affinities.

To sharpen the precision of description and classification, Joachim Jung (1587–1657) compiled a much-needed botanical terminology which has stood the test of time. English botanist John Ray (1623–1705) built on Jung's work to establish the most elaborate and insightful classification system of the day. His observations started with the local plants of Cambridge where he lived, with the ' (1860) which later expanded to his ', essentially the first British Flora. Although his ' (1682, 1688, 1704) provided a step towards a world Flora as he included more and more plants from his travels, first on the continent and then beyond. He extended Caesalpino's natural system with a more precise definition of the higher classification levels, deriving many modern families in the process, and asserted that all parts of plants were important in classification. He recognised that variation arises from both internal (genotypic) and external environmental (phenotypic) causes and that only the former was of taxonomic significance. He was also among the first experimental physiologists. The ' can be regarded as the first botanical synthesis and textbook for modern botany. According to botanical historian Alan Morton, Ray "influenced both the theory and the practice of botany more decisively than any other single person in the latter half of the seventeenth century". Ray's family system was later extended by

To sharpen the precision of description and classification, Joachim Jung (1587–1657) compiled a much-needed botanical terminology which has stood the test of time. English botanist John Ray (1623–1705) built on Jung's work to establish the most elaborate and insightful classification system of the day. His observations started with the local plants of Cambridge where he lived, with the ' (1860) which later expanded to his ', essentially the first British Flora. Although his ' (1682, 1688, 1704) provided a step towards a world Flora as he included more and more plants from his travels, first on the continent and then beyond. He extended Caesalpino's natural system with a more precise definition of the higher classification levels, deriving many modern families in the process, and asserted that all parts of plants were important in classification. He recognised that variation arises from both internal (genotypic) and external environmental (phenotypic) causes and that only the former was of taxonomic significance. He was also among the first experimental physiologists. The ' can be regarded as the first botanical synthesis and textbook for modern botany. According to botanical historian Alan Morton, Ray "influenced both the theory and the practice of botany more decisively than any other single person in the latter half of the seventeenth century". Ray's family system was later extended by Pierre Magnol

Pierre Magnol (8 June 1638 – 21 May 1715) was a French botanist. He was born in the city of Montpellier, where he lived and worked for most of his life. He became Professor of Botany and Director of the Royal Botanic Garden of Montpellier and h ...

(1638–1715) and Joseph de Tournefort

Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (5 June 165628 December 1708) was a French botanist, notable as the first to make a clear definition of the concept of genus for plants. Botanist Charles Plumier was his pupil and accompanied him on his voyages.

Lif ...

(1656–1708), a student of Magnol, achieved notoriety for his botanical expeditions, his emphasis on floral characters in classification, and for reviving the idea of the genus as the basic unit of classification.Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

(1707–1778), who eased the task of plant cataloguing. He adopted a sexual system of classification using stamens and pistils as important characters. Among his most important publications were Systema Naturae

' (originally in Latin written ' with the Orthographic ligature, ligature æ) is one of the major works of the Sweden, Swedish botanist, zoologist and physician Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) and introduced the Linnaean taxonomy. Although the syste ...

(1735), Genera Plantarum (1737), and Philosophia Botanica

''Philosophia Botanica'' ("Botanical Philosophy", ed. 1, Stockholm & Amsterdam, 1751.) was published by the Swedish naturalist and physician Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) who greatly influenced the development of botanical Taxonomy (biology), taxono ...

(1751) but it was in his Species Plantarum

' (Latin for "The Species of Plants") is a book by Carl Linnaeus, originally published in 1753, which lists every species of plant known at the time, classified into genus, genera. It is the first work to consistently apply binomial nomenclature ...

(1753) that he gave every species a binomial thus setting the path for the future accepted method of designating the names of all organisms. Linnaean thought and books dominated the world of taxonomy for nearly a century. His sexual system was later elaborated by Bernard de Jussieu (1699–1777) whose nephew Antoine-Laurent de Jussieu

Antoine Laurent de Jussieu (; 12 April 1748 – 17 September 1836) was a French botanist, notable as the first to publish a natural classification of flowering plants; much of his system remains in use today. His classification was based on an e ...

(1748–1836) extended it yet again to include about 100 orders (present-day families). Frenchman Michel Adanson (1727–1806) in his ' (1763, 1764), apart from extending the current system of family names, emphasized that a natural classification must be based on a consideration of all characters, even though these may later be given different emphasis according to their diagnostic value for the particular plant group. Adanson's method has, in essence, been followed to this day.

18th century plant taxonomy bequeathed to the 19th century a precise binomial nomenclature and botanical terminology, a system of classification based on natural affinities, and a clear idea of the ranks of family, genus and species — although the taxa to be placed within these ranks remains, as always, the subject of taxonomic research.

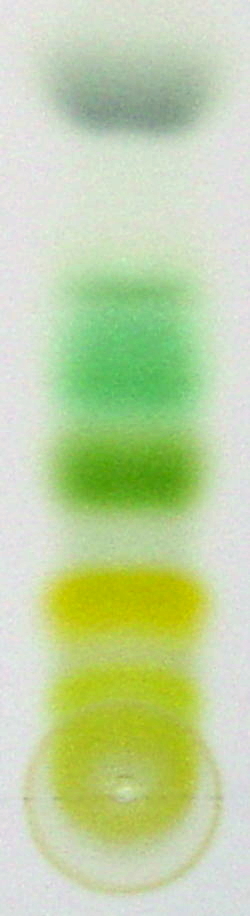

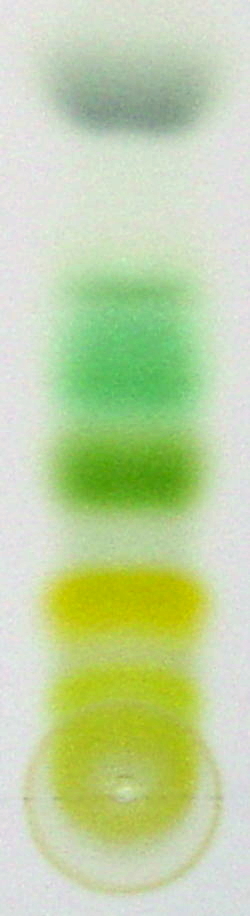

Anatomy

In the first half of the 18th century, botany was beginning to move beyond descriptive science into experimental science. Although the

In the first half of the 18th century, botany was beginning to move beyond descriptive science into experimental science. Although the microscope

A microscope () is a laboratory equipment, laboratory instrument used to examine objects that are too small to be seen by the naked eye. Microscopy is the science of investigating small objects and structures using a microscope. Microscopic ...

was invented in 1590, it was only in the late 17th century that lens grinding provided the resolution needed to make major discoveries. Antony van Leeuwenhoek is a notable example of an early lens grinder who achieved remarkable resolution with his single-lens microscopes. Important general biological observations were made by Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath who was active as a physicist ("natural philosopher"), astronomer, geologist, meteorologist, and architect. He is credited as one of the first scientists to investigate living ...

(1635–1703) but the foundations of plant anatomy were laid by Italian Marcello Malpighi

Marcello Malpighi (10 March 1628 – 30 November 1694) was an Italians, Italian biologist and physician, who is referred to as the "founder of microscopical anatomy, histology and father of physiology and embryology". Malpighi's name is borne by ...

(1628–1694) of the University of Bologna in his ' (1675) and Royal Society Englishman Nehemiah Grew

Nehemiah Grew (26 September 164125 March 1712) was an English plant anatomist and physiologist, known as the "Father of Plant Anatomy".

Biography

Grew was the only son of Obadiah Grew (1607–1688), Nonconformist divine and vicar of St Mi ...

(1628–1711) in his ''The Anatomy of Plants Begun'' (1671) and ''Anatomy of Plants'' (1682). These botanists explored what is now called developmental anatomy and morphology by carefully observing, describing and drawing the developmental transition from seed to mature plant, recording stem and wood formation. This work included the discovery and naming of parenchyma

upright=1.6, Lung parenchyma showing damage due to large subpleural bullae.