Harding Administration on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Harding won a decisive victory, receiving 404

Harding won a decisive victory, receiving 404

Harding was inaugurated as the nation's 29th president on March 4, 1921, on the East Portico of the

Harding was inaugurated as the nation's 29th president on March 4, 1921, on the East Portico of the

Harding selected numerous prominent national figures for his ten-person Cabinet. Henry Cabot Lodge, the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, suggested that Harding appoint

Harding selected numerous prominent national figures for his ten-person Cabinet. Henry Cabot Lodge, the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, suggested that Harding appoint

Harding assumed office while the nation was in the midst of a postwar economic decline known as the

Harding assumed office while the nation was in the midst of a postwar economic decline known as the

During the 1920s, use of electricity became increasingly common, and mass production of the

During the 1920s, use of electricity became increasingly common, and mass production of the

Harding spoke of equal rights in his speech when accepting the Republican nomination in 1920:

Harding spoke of equal rights in his speech when accepting the Republican nomination in 1920:

Harding took office less than two years after the end of World War I, and his administration faced several issues in the aftermath of that conflict. Harding made it clear when he appointed Hughes as Secretary of State that the former justice would run foreign policy, a change from Wilson's close management of international affairs. Harding and Hughes frequently communicated, and the president remained well-informed regarding the state of foreign affairs, but he rarely overrode any of Hughes's decisions. Hughes did have to work within some broad outlines; after taking office, Harding hardened his stance on the

Harding took office less than two years after the end of World War I, and his administration faced several issues in the aftermath of that conflict. Harding made it clear when he appointed Hughes as Secretary of State that the former justice would run foreign policy, a change from Wilson's close management of international affairs. Harding and Hughes frequently communicated, and the president remained well-informed regarding the state of foreign affairs, but he rarely overrode any of Hughes's decisions. Hughes did have to work within some broad outlines; after taking office, Harding hardened his stance on the

At the end of World War I, the United States had the largest navy and one of the largest armies in the world. With no serious threat to the United States itself, Harding and his successors presided over the disarmament of the navy and the army. The army shrank to 140,000 men, while naval reduction was based on a policy of parity with Britain. Seeking to prevent an arms race, Senator

At the end of World War I, the United States had the largest navy and one of the largest armies in the world. With no serious threat to the United States itself, Harding and his successors presided over the disarmament of the navy and the army. The army shrank to 140,000 men, while naval reduction was based on a policy of parity with Britain. Seeking to prevent an arms race, Senator

The most notorious scandal was

The most notorious scandal was

Daugherty's personal aide, Jess W. Smith, was a central figure in government file manipulation, paroles and pardons, influence peddling—and even served as

Daugherty's personal aide, Jess W. Smith, was a central figure in government file manipulation, paroles and pardons, influence peddling—and even served as

Harding's lifestyle at the White House was fairly unconventional compared to his predecessor. Upstairs at the White House, in the

Harding's lifestyle at the White House was fairly unconventional compared to his predecessor. Upstairs at the White House, in the

"A President Of the Peephole"

''The Washington Post'', June 7, 1998; retrieved December 24, 2010. Harding played poker twice a week, smoked and chewed tobacco. Harding allegedly won a $4,000 pearl necktie pin at one White House poker game. Although criticized by Prohibitionist advocate Wayne B. Wheeler over Washington, D.C. rumors of these "wild parties", Harding claimed his personal drinking inside the White House was his own business. Though Mrs. Harding did keep a little red book of those who had offended her, the executive mansion was now once again open to the public for events including the annual Easter egg roll.

Though Harding wanted to run for a second term, his health began to decline during his time in office. He gave up drinking, sold his "life-work," the Marion ''Star'', in part to regain $170,000 previous investment losses, and had Daugherty make him a new will. Harding, along with his personal physician Dr. Charles E. Sawyer, believed getting away from

Though Harding wanted to run for a second term, his health began to decline during his time in office. He gave up drinking, sold his "life-work," the Marion ''Star'', in part to regain $170,000 previous investment losses, and had Daugherty make him a new will. Harding, along with his personal physician Dr. Charles E. Sawyer, believed getting away from

February–March 1988 issue

of ''The Beaver'' Harding also visited a golf course, but completed only six holes before being fatigued. He was not successful in hiding his exhaustion; one reporter deemed him so tired a rest of mere days would not be sufficient to refresh him.

Upon his death, Harding was deeply mourned—not only in the United States, but around the world. He was called a man of peace in many European newspapers. American journalists praised him lavishly, with some describing him as having given his life for his country. His associates were stunned by his demise. Daugherty wrote, "I can hardly write about it or allow myself to think about it yet." Hughes stated, "I cannot realize that our beloved Chief is no longer with us."

Upon his death, Harding was deeply mourned—not only in the United States, but around the world. He was called a man of peace in many European newspapers. American journalists praised him lavishly, with some describing him as having given his life for his country. His associates were stunned by his demise. Daugherty wrote, "I can hardly write about it or allow myself to think about it yet." Hughes stated, "I cannot realize that our beloved Chief is no longer with us."

online

* Payne, Phillip. "Instant History and the Legacy of Scandal: the Tangled Memory of Warren G. Harding, Richard Nixon, and William Jefferson Clinton", ''Prospects'', 28: 597–625, 2003. * Rhodes, Benjamin D. ''United States Foreign Policy in the Interwar Period, 1918–1941: The Golden Age of American Diplomatic and Military Complacency'' (Greenwood, 2001)

online

* Sibley, Katherine A.S., ed. ''A Companion to Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover'' (2014); 616pp; essays by scholars stressing historiograph

online

* Sullivan, Mark. ''Our Times: 1900-1925: Volume 6: The Twenties'' (1935) pp. 16–371

online

by a leading journalist. * Walters, Ryan S. ''The Jazz Age President: Defending Warren G. Harding'' (2022

excerpt

als

online review

excerpt

Full audio and text of a number of Harding speeches

Warren Harding: A Resource Guide

Extensive essays on Warren Harding

and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady from the Miller Center of Public Affairs

Warren G. Harding

at

Warren G. Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he was one of the most ...

's tenure as the 29th president of the United States lasted from March 4, 1921, until his death on August 2, 1923. Harding presided over the country in the aftermath of World War I

The aftermath of World War I saw far-reaching and wide-ranging cultural, economic, and social change across Europe, Asia, Africa, and in areas outside those that were directly involved. Four empires collapsed due to the war, old countries were a ...

. A Republican from Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

, Harding held office during a period in American political history from the mid-1890s to 1932 that was generally dominated by his party. He died of an apparent heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when Ischemia, blood flow decreases or stops in one of the coronary arteries of the heart, causing infarction (tissue death) to the heart muscle. The most common symptom ...

and was succeeded by Vice President Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States, serving from 1923 to 1929. A Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer from Massachusetts, he previously ...

.

Harding took office after defeating Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (Cyprus) (DCY)

**Democratic Part ...

James M. Cox

James Middleton Cox (March 31, 1870 July 15, 1957) was an American businessman and politician who served as the 46th and 48th governor of Ohio, and a two-term U.S. Representative from Ohio. As the Democratic nominee for President of the Unite ...

in the 1920 presidential election. Running against the policies of incumbent Democratic President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

, Harding won the popular vote by a margin of 26.2 percentage points, which remains the largest popular-vote percentage margin in presidential elections since the end of the Era of Good Feelings

The Era of Good Feelings marked a period in the political history of the United States that reflected a sense of national purpose and a desire for unity among Americans in the aftermath of the War of 1812. The era saw the collapse of the Fe ...

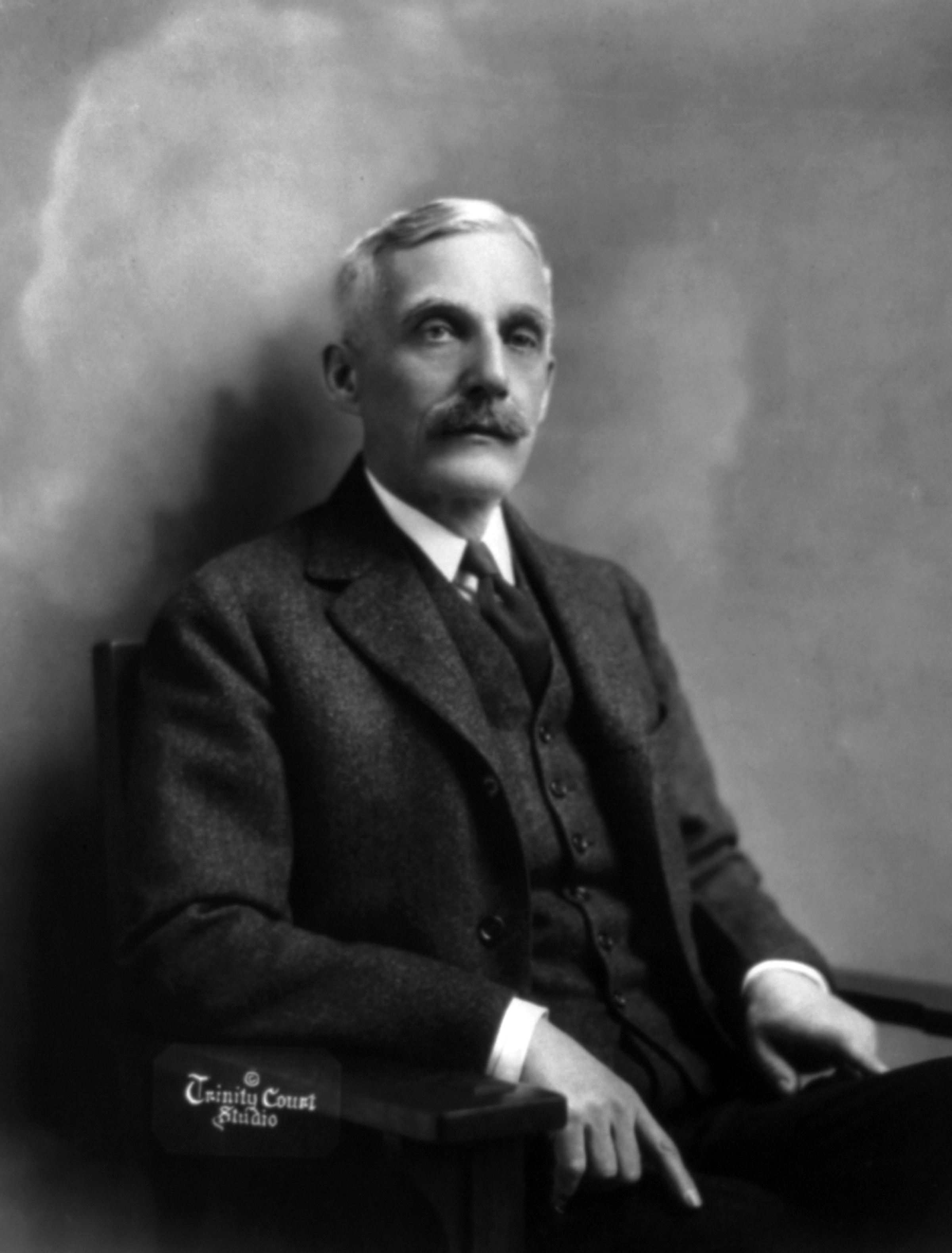

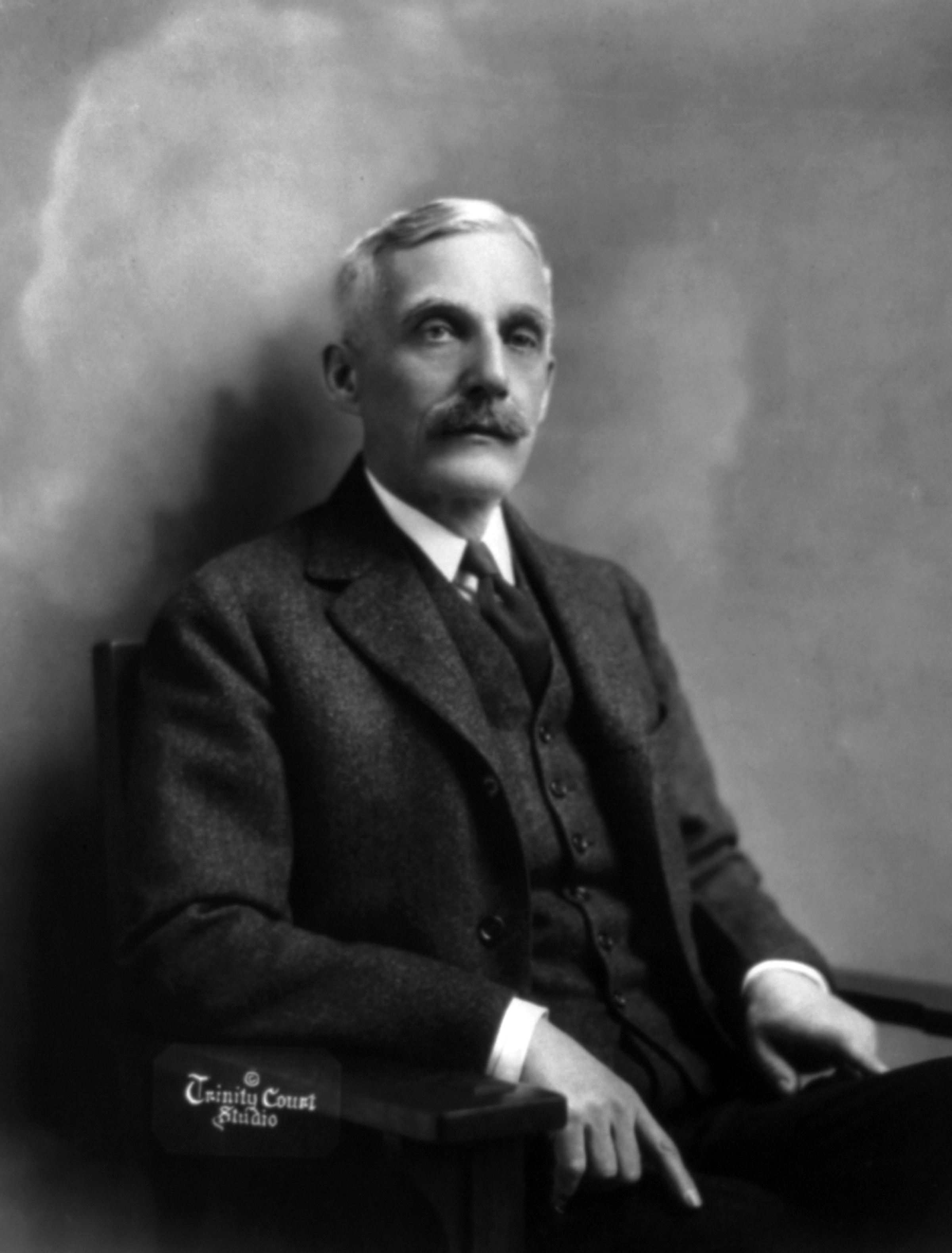

in the 1820s. Upon taking office, Harding instituted conservative policies designed to minimize the government's role in the economy. Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon

Andrew William Mellon (; March 24, 1855 – August 26, 1937), known also as A. W. Mellon, was an American banker, businessman, industrialist, philanthropist, art collector, and politician. The son of Mellon family patriarch Thomas Mellon ...

won passage of the Revenue Act of 1921, a major tax cut that primarily reduced taxes on the wealthy. Harding also signed the Budget and Accounting Act

The Budget and Accounting Act of 1921 () was landmark legislation that established the framework for the modern federal budget. The act was approved by President Warren G. Harding to provide a national budget system and an independent audit of g ...

, which established the country's first formal budgeting process and created the Bureau of the Budget

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) is the largest office within the Executive Office of the President of the United States (EOP). The office's most prominent function is to produce the president's budget, while it also examines agency pro ...

. Another major aspect of his domestic policy was the Fordney–McCumber Tariff

The Fordney–McCumber Tariff of 1922 was a law that raised American tariffs on many imported goods to protect factories and farms. The US Congress displayed a pro-business attitude in passing the tariff and in promoting foreign trade by providi ...

, which greatly increased tariff rates.

Harding supported the 1921 Emergency Quota Act

__NOTOC__

The Emergency Quota Act, also known as the Emergency Immigration Act of 1921, the Immigration Restriction Act of 1921, the Per Centum Law, and the Johnson Quota Act (ch. 8, of May 19, 1921), was formulated mainly in response to the lar ...

, which marked the start of a period of restrictive immigration policies. He vetoed a bill designed to give a bonus to World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

veterans but presided over the creation of the Veterans Bureau. He also signed into law several bills designed to address the farm crisis

A farm crisis is an American term for a time of agricultural recession, low crop prices and low farm incomes. The Interwar farm crisis was an extended period of depressed agricultural incomes from the end of the First to the start of the Second ...

and, along with Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and ...

, promoted new technologies like the radio and aviation. Harding's foreign policy was directed by Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American politician, academic, and jurist who served as the 11th chief justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

. Hughes's major foreign policy achievement was the Washington Naval Conference

The Washington Naval Conference (or the Washington Conference on the Limitation of Armament) was a disarmament conference called by the United States and held in Washington, D.C., from November 12, 1921, to February 6, 1922.

It was conducted out ...

of 1921–1922, in which the world's major naval powers agreed on a naval disarmament program. Harding appointed four Supreme Court justices, all of whom became conservative members of the Taft Court

The Taft Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1921 to 1930, when William Howard Taft served as Chief Justice of the United States. Taft succeeded Edward Douglass White as Chief Justice after the latter's death, and Taft ser ...

. Shortly after Harding's death, several major scandals emerged, including the Teapot Dome scandal

The Teapot Dome scandal was a political corruption scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Warren G. Harding. It centered on Interior Secretary Albert B. Fall, who had leased Navy petroleum reserves at Teapot Do ...

.

Harding died as one of the most popular presidents in history, but the subsequent exposure of the scandals eroded his popular regard, as did revelations of several extramarital affairs. In historical rankings of the U.S. presidents during the decades after his term in office, Harding was often rated among the worst. However, in recent decades, many historians have begun to fundamentally reassess the conventional views of Harding's historical record in office.

1920 election

Republican nomination

By early 1920, GeneralLeonard Wood

Leonard Wood (October 9, 1860 – August 7, 1927) was a United States Army major general, physician, and public official. He served as the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, List of colonial governors of Cuba, Military Governor of Cuba, ...

, Illinois governor Frank Lowden

Frank Orren Lowden (January 26, 1861 – March 20, 1943) was an American Republican Party politician who served as the 25th Governor of Illinois and as a United States Representative from Illinois. He was also a candidate for the Republican pre ...

, and Senator Hiram Johnson

Hiram Warren Johnson (September 2, 1866August 6, 1945) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 23rd governor of California from 1911 to 1917 and represented California in the U.S. Senate for five terms from 1917 to 1945. Johns ...

of California had emerged as the frontrunners for the Republican nomination in the upcoming presidential election. Some in the party began to scout for such an alternative, and Harding's name arose, despite his reluctance, due to his unique ability to draw vital Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

votes. Harry Daugherty

Harry Micajah Daugherty (; January 26, 1860 – October 12, 1941) was an American politician. A key Republican political insider from Ohio, he is best remembered for his service as Attorney General of the United States under presidents Warren G. ...

, who became Harding's campaign manager, and who was sure none of these candidates could garner a majority, convinced Harding to run after a marathon discussion of six-plus hours. Daugherty's strategy focused on making Harding liked by or at least acceptable to all wings of the party, so that Harding could emerge as a compromise candidate in the likely event of a convention deadlock. He struck a deal with Oklahoma oilman Jake L. Hamon, whereby 18 Oklahoma delegates whose votes Hamon had bought for Lowden were committed to Harding as a second choice if Lowden's effort faltered.

By the time the 1920 Republican National Convention

The 1920 Republican National Convention nominated Ohio Senator Warren G. Harding for president and Massachusetts Governor Calvin Coolidge for vice president. The convention was held in Chicago, Illinois, at the Chicago Coliseum from June 8 ...

began in June, a Senate sub-committee had tallied the monies spent by the various candidates, with totals as follows: Wood$1.8 million; Lowden$414,000; Johnson$194,000; and Harding$114,000; the committed delegate count at the opening gavel was: Wood124; Johnson112; Lowden72; Harding39. Still, at the opening, less than one-half of the delegates were committed, and many expected the convention to nominate a compromise candidate like Pennsylvania Senator Philander C. Knox

Philander Chase Knox (May 6, 1853October 12, 1921) was an American lawyer, bank director, statesman and Republican Party politician. He represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate from 1904 to 1909 and 1917 to 1921. He was the 44th Unit ...

, Massachusetts Senator Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850November 9, 1924) was an American politician, historian, lawyer, and statesman from Massachusetts. A member of the History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served in the United States ...

, or 1916 nominee Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American politician, academic, and jurist who served as the 11th chief justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

. No candidate was able to corral a majority after nine ballots. After the convention adjourned for the day, Republican Senators and other leaders, who were divided and without a singular political boss, met in Room 404 of the Blackstone Hotel

The Blackstone Hotel is a historic 21-story hotel on the corner of Michigan Avenue and Balbo Drive in the Michigan Boulevard Historic District in the Loop community area of Chicago, Illinois. Built between 1908 and 1910, it is on the Natio ...

in Chicago. After a nightlong session, these party leaders tentatively concluded Harding was the best possible compromise candidate; this meeting has often been described as having taken place in a "smoke-filled room

In U.S. political jargon, a smoke-filled room (sometimes called a smoke-filled back room) is an exclusive, sometimes secret political gathering or round-table-style decision-making process. The phrase is generally used to suggest an inner ci ...

." The next day, on the tenth ballot, Harding was nominated for president. Delegates then selected Massachusetts governor Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States, serving from 1923 to 1929. A Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer from Massachusetts, he previously ...

to be his vice-presidential running mate.

General election

Harding's opponent in the 1920 election was Ohio governor and newspapermanJames M. Cox

James Middleton Cox (March 31, 1870 July 15, 1957) was an American businessman and politician who served as the 46th and 48th governor of Ohio, and a two-term U.S. Representative from Ohio. As the Democratic nominee for President of the Unite ...

, who had won the Democratic nomination in a 44-ballot convention battle. Harding rejected the Progressive ideology of the Wilson administration

Woodrow Wilson served as the 28th president of the United States from March 4, 1913, to March 4, 1921. A History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat and former governor of New Jersey, Wilson took office after winning the 1912 Uni ...

in favor of the laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

approach of the McKinley administration. He ran on the promise of a "return to normalcy

"Return to normalcy" was a campaign slogan used by Warren G. Harding during the 1920 United States presidential election. Harding won the election with 60.4% of the popular vote.

1920 election

In a speech delivered on May 14, 1920, Harding pr ...

," calling for the end to an era which he saw as tainted by war, internationalism, and government activism. He stated:

The 1920 election was the first in which women could vote nationwide, as well as the first to be covered on the radio. Led by Albert Lasker

Albert Davis Lasker (May 1, 1880 – May 30, 1952) was an American businessman who played a major role in shaping modern advertising. He was raised in Galveston, Texas, where his father was the president of several banks. Moving to Chicago, he b ...

, the Harding campaign executed a broad-based advertising campaign

An advertising campaign or marketing campaign is a series of advertisement messages that share a single idea and theme which make up an integrated marketing communication (IMC). An IMC is a platform in which a group of people can group their ide ...

that used modern advertising techniques for the first time in a presidential campaign. Using newsreels, motion pictures, sound recordings, billboard posters, newspapers, magazines, and other media, Lasker emphasized and enhanced Harding's patriotism and affability. Five thousand speakers were trained by advertiser Harry New and sent across the country to speak for Harding. Telemarketers

Telemarketing (sometimes known as inside sales, or telesales in the UK and Ireland) is a method of direct marketing in which a salesperson solicits prospective customers to buy products, subscriptions or services, either over the phone or throug ...

were used to make phone conferences with perfected dialogues to promote Harding, and Lasker had 8,000 photos of Harding and his wife distributed around the nation every two weeks. Farmers were sent brochures decrying the alleged abuses of Democratic agriculture policies, while African Americans and women were given literature in an attempt to take away votes from the Democrats. Additionally, celebrities like Al Jolson

Al Jolson (born Asa Yoelson, ; May 26, 1886 – October 23, 1950) was a Lithuanian-born American singer, comedian, actor, and vaudevillian.

Self-billed as "The World's Greatest Entertainer," Jolson was one of the United States' most famous and ...

and Lillian Russell

Lillian Russell (born Helen Louise Leonard; December 4, 1860 or 1861 – June 6, 1922) was an American actress and singer. She became one of the most famous actresses and singers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, praised for her beaut ...

toured the nation on Harding's behalf.

electoral votes

An electoral college is a body whose task is to elect a candidate to a particular office. It is mostly used in the political context for a constitutional body that appoints the head of state or government, and sometimes the upper parliamenta ...

to Cox's 127. He took 60 percent of the nationwide popular vote, the highest percentage ever recorded up to that time, while Cox received just 34 percent of the vote. Campaigning from a federal prison, Socialist Party

Socialist Party is the name of many different political parties around the world. All of these parties claim to uphold some form of socialism, though they may have very different interpretations of what "socialism" means. Statistically, most of th ...

candidate Eugene V. Debs

Eugene Victor Debs (November 5, 1855 – October 20, 1926) was an American socialist, political activist, trade unionist, one of the founding members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and five-time candidate of the Socialist Party o ...

received 3% percent of the national vote. Harding won the popular vote by a margin of 26.2%, the largest margin since the election of 1820. He swept every state outside of the "Solid South

The Solid South was the electoral voting bloc for the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party in the Southern United States between the end of the Reconstruction era in 1877 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In the aftermath of the Co ...

", and his victory in Tennessee made him the first Republican to win a former Confederate

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

state since the end of Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

. In the concurrent congressional elections, the Republicans picked up 63 seats in the House of Representatives. The incoming 67th Congress

The 67th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C., from March 4, 19 ...

would be dominated by Republicans, though the party was divided among various factions, including an independent-minded farm bloc from the Midwest.

Inauguration

Harding was inaugurated as the nation's 29th president on March 4, 1921, on the East Portico of the

Harding was inaugurated as the nation's 29th president on March 4, 1921, on the East Portico of the United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called the Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the Seat of government, seat of the United States Congress, the United States Congress, legislative branch of the Federal government of the United States, federal g ...

. Chief Justice Edward D. White administered the oath of office

An oath of office is an oath or affirmation a person takes before assuming the duties of an office, usually a position in government or within a religious body, although such oaths are sometimes required of officers of other organizations. Suc ...

. Harding placed his hand on the Washington Inaugural Bible as he recited the oath. This was the first time that a U.S. president rode to and from his inauguration in an automobile. In his inaugural address Harding reiterated the themes of his campaign, declaring:

Literary critic H.L. Mencken

Henry Louis Mencken (September 12, 1880 – January 29, 1956) was an American journalist, essayist, satirist, cultural critic, and scholar of American English. He commented widely on the social scene, literature, music, prominent politicians, ...

was appalled, announcing that:

Administration

Cabinet

Harding selected numerous prominent national figures for his ten-person Cabinet. Henry Cabot Lodge, the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, suggested that Harding appoint

Harding selected numerous prominent national figures for his ten-person Cabinet. Henry Cabot Lodge, the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, suggested that Harding appoint Elihu Root

Elihu Root (; February 15, 1845February 7, 1937) was an American lawyer, Republican Party (United States), Republican politician, and statesman who served as the 41st United States Secretary of War under presidents William McKinley and Theodor ...

or Philander C. Knox

Philander Chase Knox (May 6, 1853October 12, 1921) was an American lawyer, bank director, statesman and Republican Party politician. He represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate from 1904 to 1909 and 1917 to 1921. He was the 44th Unit ...

as Secretary of State, but Harding instead selected former Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes for the position. Harding appointed Henry C. Wallace

Henry Cantwell Wallace (May 11, 1866 – October 25, 1924) was an American farmer, journalist, and political activist who served as the secretary of agriculture from 1921 to 1924 under Republican presidents Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidg ...

, an Iowan journalist who had advised Harding's 1920 campaign on farm issues, as Secretary of Agriculture. After Charles G. Dawes declined Harding's offer to become Secretary of the Treasury, Harding assented to Senator Boies Penrose

Boies Penrose (November 1, 1860 – December 31, 1921) was an American politician from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, who served as a Republican member of the United States Senate for Pennsylvania from 1897 to 1921. He served as a member of th ...

's suggestion to select Pittsburgh billionaire Andrew Mellon

Andrew William Mellon (; March 24, 1855 – August 26, 1937), known also as A. W. Mellon, was an American banker, businessman, industrialist, philanthropist, art collector, and politician. The son of Mellon family patriarch Thomas Mellon ...

. Harding used Mellon's appointment as leverage to win confirmation for Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and ...

, who had led the U.S. Food Administration under Wilson and who became Harding's Secretary of Commerce.

Rejecting public calls to appoint Leonard Wood as Secretary of War, Harding instead appointed Lodge's preferred candidate, former Senator John W. Weeks of Massachusetts. He selected James J. Davis for the position of Secretary of Labor, as Davis satisfied Harding's criteria of being broadly acceptable to labor but being opposed to labor leader Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers (; January 27, 1850December 11, 1924) was a British-born American cigar maker, labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and served as the organization's ...

. Will H. Hays

William Harrison Hays Sr. (; November 5, 1879 – March 7, 1954) was an American politician, and member of the Republican Party. As chairman of the Republican National Committee from 1918 to 1921, Hays managed the successful 1920 presidential ...

, the chairman of the Republican National Committee

The Republican National Committee (RNC) is the primary committee of the Republican Party of the United States. Its members are chosen by the state delegations at the national convention every four years. It is responsible for developing and pr ...

, was appointed Postmaster General. Grateful for his actions at the 1920 Republican convention, Harding offered Frank Lowden the post of Secretary of the Navy. After Lowden turned down the post, Harding instead appointed former Congressman Edwin Denby of Michigan. New Mexico Senator Albert B. Fall

Albert Bacon Fall (November 26, 1861November 30, 1944) was a United States senator from New Mexico and United States Secretary of the Interior, Secretary of the Interior under President of the United States, President Warren G. Harding who becam ...

, a close ally of Harding's during their time in the Senate together, became Harding's Secretary of the Interior.

Although Harding was committed to putting the "best minds" on his Cabinet, he often awarded other appointments to those who had contributed to his campaign's victory. Wayne Wheeler, leader of the Anti-Saloon League

The Anti-Saloon League, now known as the American Council on Addiction and Alcohol Problems, is an organization of the temperance movement in the United States.

Founded in 1893 in Oberlin, Ohio, it was a key component of the Progressive Era, an ...

, was allowed by Harding to dictate who would serve on the Prohibition Commission. Harding appointed Harry M. Daugherty as Attorney General because he felt he owed Daugherty for running his 1920 campaign. After the election, many people from the Ohio area moved to Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, made their headquarters in a little green house on K Street

The Little Green House on K Street was a residence at 1625 K Street, NW, Washington, D.C., United States, where the notoriously corrupt deals of Harding administration are believed to have been planned between 1921 and 1923.

History

The Littl ...

, and would be eventually known as the "Ohio Gang

The Ohio Gang was a gang of politicians and industry leaders closely surrounding Warren G. Harding, the 29th president of the United States. Many of these individuals came into Harding's personal orbit during his tenure as a state-level politici ...

". Graft and corruption charges permeated Harding's Department of Justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice, is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

; bootleggers confiscated

Confiscation (from the Latin ''confiscatio'' "to consign to the ''fiscus'', i.e. transfer to the treasury") is a legal form of seizure by a government or other public authority. The word is also used, popularly, of spoliation under legal forms, o ...

tens of thousands cases of whiskey through bribery

Bribery is the corrupt solicitation, payment, or Offer and acceptance, acceptance of a private favor (a bribe) in exchange for official action. The purpose of a bribe is to influence the actions of the recipient, a person in charge of an official ...

and kickbacks

A kickback is a form of negotiated bribery in which a commission is paid to the bribe-taker in exchange for services rendered. Generally speaking, the remuneration (money, goods, or services handed over) is negotiated ahead of time. The kickback ...

. The financial and political scandals caused by the Ohio Gang and other Harding appointees, in addition to Harding's own personal controversies, severely damaged Harding's personal reputation and eclipsed his presidential accomplishments.

Press corps

According to biographers, Harding got along better with the press than any other previous president, being a former newspaperman. Reporters admired his frankness, candor, and his confessed limitations. He took the press behind the scenes and showed them the inner circle of the presidency. In November 1921, Harding also implemented a policy of taking written questions from reporters during a press conference.Judicial appointments

Harding appointed four justices to theSupreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all Federal tribunals in the United States, U.S. federal court cases, and over Stat ...

. After the death of Chief Justice

Edward Douglass White

Edward Douglass White Jr. (November 3, 1845 – May 19, 1921) was an American politician and jurist. A native of Louisiana, White was a Supreme Court of the United States, U.S. Supreme Court justice for 27 years, first as an Associate Justice of ...

, former President William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) served as the 27th president of the United States from 1909 to 1913 and the tenth chief justice of the United States from 1921 to 1930. He is the only person to have held both offices. ...

lobbied Harding for the nomination to succeed White. Harding acceded to Taft's request, and Taft joined the court in June 1921. Harding's next choice for the Court was conservative former Senator George Sutherland

George Alexander Sutherland (March 25, 1862July 18, 1942) was a British-born American jurist and politician. He served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court between 1922 and 1938. As a member of the Republican Party, he also repre ...

of Utah, who had been a major supporter of Taft in 1912 and Harding in 1920. Sutherland succeeded John Hessin Clarke

John Hessin Clarke (September 18, 1857 – March 22, 1945) was an American lawyer and judge who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1916 to 1922.

Early life

Born in New Lisbon, Ohio, Clarke was the thir ...

in September 1922 after Clarke resigned. Two Supreme Court vacancies arose in 1923 due to the death of William R. Day

William Rufus Day (April 17, 1849 – July 9, 1923) was an American diplomat and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1903 to 1922. Prior to his service on the Supreme Court, Day served as Uni ...

and the resignation of Mahlon Pitney

Mahlon R. Pitney IV (February 5, 1858 – December 9, 1924) was an American lawyer, jurist, and politician who served in the U.S. House of Representatives for two terms from 1895 to 1899. He later served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supr ...

. On Taft's recommendation, Harding nominated railroad attorney and conservative Democrat Pierce Butler Pierce or Piers Butler may refer to:

* Piers Butler, 8th Earl of Ormond (c. 1467 – 26 August 1539), Anglo-Irish nobleman in the Peerage of Ireland

* Piers Butler, 3rd Viscount Galmoye (1652–1740), Anglo-Irish nobleman in the Peerage of Ireland

* ...

to succeed Day. Progressive senators like Robert M. La Follette

Robert Marion La Follette Sr. (June 14, 1855June 18, 1925), nicknamed "Fighting Bob," was an American lawyer and politician. He represented Wisconsin in both chambers of Congress and served as the 20th governor of Wisconsin from 1901 to 1906. ...

unsuccessfully sought to defeat Butler's nomination, but Butler was confirmed. On the advice of Attorney General Daugherty, Harding appointed federal appellate judge Edward Terry Sanford

Edward Terry Sanford (July 23, 1865 – March 8, 1930) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1923 until his death in 1930. Prior to his nomination to the high court, Sanford ser ...

of Tennessee to succeed Pitney. Bolstered by these appointments, the Taft Court

The Taft Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1921 to 1930, when William Howard Taft served as Chief Justice of the United States. Taft succeeded Edward Douglass White as Chief Justice after the latter's death, and Taft ser ...

upheld the precedents of the Lochner era

The ''Lochner'' era was a period in American legal history from 1897 to 1937 in which the Supreme Court of the United States is said to have made it a common practice "to strike down economic regulations adopted by a State based on the Court's o ...

and largely reflected the conservatism of the 1920s.

The Justice Department in the Harding Administration selected 6 judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, 42 judges to the United States district courts

The United States district courts are the trial courts of the United States federal judiciary, U.S. federal judiciary. There is one district court for each United States federal judicial district, federal judicial district. Each district cov ...

, and 2 judges to the United States Court of Customs Appeals

The United States Court of Customs and Patent Appeals (CCPA) was a United States federal court which existed from 1909 to 1982 and had jurisdiction over certain types of civil disputes.

History

The CCPA began as the United States Court of Custom ...

.

Domestic affairs

Revenue Act of 1921

Harding assumed office while the nation was in the midst of a postwar economic decline known as the

Harding assumed office while the nation was in the midst of a postwar economic decline known as the Depression of 1920–21

Depression may refer to:

Mental health

* Depression (mood), a state of low mood and aversion to activity

* Mood disorders characterized by depression are commonly referred to as simply ''depression'', including:

** Major depressive disorder, al ...

. He strongly rejected proposals to provide for federal unemployment benefits

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is the proportion of people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work d ...

, believing that the government should leave relief efforts to charities and local governments. He believed that the best way to restore economic prosperity was to raise tariff

A tariff or import tax is a duty (tax), duty imposed by a national Government, government, customs territory, or supranational union on imports of goods and is paid by the importer. Exceptionally, an export tax may be levied on exports of goods ...

rates and reduce the government's role in economic activities. His administration's economic policy was formulated by Secretary of the Treasury Mellon, who proposed cuts to the excess profits tax

An excess profits tax, EPT, is a tax on returns or profits which exceed risk-adjusted ''normal'' returns. The concept of ''excess profit'' is very similar to that of economic rent. Excess profit taxes are usually imposed on monopolist industries ...

and the corporate tax. The central tenet of Mellon's tax plan was a reduction of the surtax, a progressive income tax that only affected high-income earners. Mellon favored the wealthy holding as much capital as possible, since he saw them as the main drivers of economic growth. Congressional Republican leaders shared Harding and Mellon's desire for tax cuts, and Republicans made tax cuts and tariff rates the key legislative priorities of Harding's first year in office. Harding called a special session of the Congress to address these and other issues, and Congress convened in April 1921.

Despite opposition from Democrats and many farm state Republicans, Congress passed the Revenue Act of 1921 in November, and Harding signed the bill into law later that month. The act greatly reduced taxes for the wealthiest Americans, though the cuts were not as deep as Mellon had favored. The act reduced the top marginal income tax rate from 73 percent to 58 percent, lowered the corporate tax from 65 percent to 50 percent, and provided for ultimate elimination of the excess profits tax. Revenues to the treasury decreased substantially.

Wages, profits, and productivity all made substantial gains during the 1920s, and economists have differed as to whether Revenue Act of 1921 played a major role in the strong period of economic growth after the Depression of 1920–21. Economist Daniel Kuehn has attributed the improvement to the earlier monetary policy of the Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve System (often shortened to the Federal Reserve, or simply the Fed) is the central banking system of the United States. It was created on December 23, 1913, with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, after a series of ...

, and notes that the changes in marginal tax rates were accompanied by an expansion in the tax base that could account for the increase in revenue. Libertarian

Libertarianism (from ; or from ) is a political philosophy that holds freedom, personal sovereignty, and liberty as primary values. Many libertarians believe that the concept of freedom is in accord with the Non-Aggression Principle, according ...

historians Schweikart and Allen argue that Harding's tax and economic policies in part "... produced the most vibrant eight year burst of manufacturing and innovation in the nation's history," Recovery did not last long. Another economic contraction began near the end of Harding's presidency in 1923, while tax cuts were still underway. A third contraction followed in 1927 during the next presidential term. Some economists have argued that the tax cuts resulted in growing economic inequality and speculation

In finance, speculation is the purchase of an asset (a commodity, good (economics), goods, or real estate) with the hope that it will become more valuable in a brief amount of time. It can also refer to short sales in which the speculator hope ...

, which in turn contributed to the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

.

Fordney– McCumber Tariff

Like most Republicans of his era, Harding favoredprotective tariff

Protective tariffs are tariffs that are enacted with the aim of protecting a domestic industry. They aim to make imported goods cost more than equivalent goods produced domestically, thereby causing sales of domestically produced goods to rise, ...

s-- high taxes on selected imports. Before 1920 Harding was a spokesman for the traditional Republican Party stance favoring high tariffs to protect the manufacturing industries and the high wages they paid. In the 1920 campaign and during his presidency, Harding was a strong advocate for protectionism, believing that tariffs were essential to safeguard American jobs and industries. He believed that tariffs would stimulate domestic manufacturing, keep factory wages high, and lead to general prosperity. However, Harding's administration also sought to negotiate reciprocal trade agreements, which involved reducing tariffs on imports from another country in exchange for similar concessions by it. This approach aimed to promote more trade while still protecting domestic industries.

Shortly after taking office, he signed the Emergency Tariff of 1921

The Emergency Tariff of 1921 of the United States was enacted on May 27, 1921. The Underwood Tariff, passed under the Presidency of Woodrow Wilson, had Republican leaders in the United States Congress rush to create a temporary measure to ease th ...

, a stopgap measure primarily designed to aid American farmers suffering from the effects of an expansion in European farm imports. The emergency tariff also protected domestic manufacturing, as it included a clause to prevent dumping by European manufacturers. Harding hoped to sign a permanent tariff into law by the end of 1921, but heated congressional debate over tariff schedules, especially between agricultural and manufacturing interests, delayed passage of such a bill.

In September 1922, Harding enthusiastically signed the Fordney–McCumber Tariff

The Fordney–McCumber Tariff of 1922 was a law that raised American tariffs on many imported goods to protect factories and farms. The US Congress displayed a pro-business attitude in passing the tariff and in promoting foreign trade by providi ...

Act. The protectionist legislation was sponsored by Representative Joseph W. Fordney and Senator Porter J. McCumber, and was supported by nearly every congressional Republican. The act increased the tariff rates contained in the previous Underwood-Simmons Tariff Act of 1913, to the highest level in the nation's history. Harding became concerned when the agriculture business suffered economic hardship from the high tariffs. By 1922, Harding began to believe that the long-term effects of high tariffs could be detrimental to national economy, despite the short-term benefits. The high tariffs established under Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover have historically been viewed as a contributing factor to the Wall Street Crash of 1929.

Bureau of the Budget

Harding believed the federal government should be fiscally managed in a way similar to private sector businesses. He had campaigned on the slogan, "Less government in business and more business in government." As theHouse Ways and Means Committee

A ways and means committee is a government body that is charged with reviewing and making recommendations for government budgets. Because the raising of revenue is vital to carrying out governmental operations, such a committee is tasked with fi ...

found it increasingly difficult to balance revenues and expenditures, Taft had recommended the creation of a federal budget system during his presidency. Businessmen and economists coalesced around Taft's proposal during the Wilson administration, and by 1920, both parties favored it. Reflecting this goal, in June 1921, Harding signed the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921

The Budget and Accounting Act of 1921 () was landmark legislation that established the framework for the modern federal budget. The act was approved by President Warren G. Harding to provide a national budget system and an independent audit of g ...

.

The act established the Bureau of the Budget

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) is the largest office within the Executive Office of the President of the United States (EOP). The office's most prominent function is to produce the president's budget, while it also examines agency pro ...

to coordinate the federal budgeting process. At the head of this office was the presidential budget director, who was directly responsible to the president rather than to the Secretary of Treasury. The law also stipulated that the president must annually submit a budget to Congress, and all presidents since have had to do so. Additionally, the General Accounting Office

The United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) is an independent, nonpartisan government agency within the legislative branch that provides auditing, evaluative, and investigative services for the United States Congress. It is the sup ...

(GAO) was created to assure congressional oversight of federal budget expenditures. The GAO would be led by the Comptroller General

A comptroller (pronounced either the same as ''controller'' or as ) is a management-level position responsible for supervising the quality of accountancy, accounting and financial reporting of an organization. A financial comptroller is a senior- ...

, who was appointed by Congress to a term of fifteen years. Harding appointed Charles Dawes as the Bureau of the Budget's first director. Dawes's first year in office saw government spending reduced by $1.5 billion, a 25 percent reduction, and he presided over another 25 percent reduction the following year.

Immigration restriction

In the first two decades of the 20th century, immigration to the United States had increased, with many of the immigrants coming fromSouthern Europe

Southern Europe is also known as Mediterranean Europe, as its geography is marked by the Mediterranean Sea. Definitions of southern Europe include some or all of these countries and regions: Albania, Andorra, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, C ...

and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

rather than Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

. Many Americans viewed these new immigrants with suspicion, and World War I and the First Red Scare

The first Red Scare was a period during History of the United States (1918–1945), the early 20th-century history of the United States marked by a widespread fear of Far-left politics, far-left movements, including Bolsheviks, Bolshevism a ...

further heightened nativist fears. The Per Centum Act of 1921, signed by Harding on May 19, 1921, reduced the numbers of immigrants

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not usual residents or where they do not possess nationality in order to settle as permanent residents. Commuters, tourists, and other short- ...

to 3 percent of a country's represented population based on the 1910 Census

The 1910 United States census, conducted by the Census Bureau on April 15, 1910, determined the resident population of the United States to be 92,228,496, an increase of 21 percent over the 76,212,168 persons enumerated during the 1900 census. ...

. The act, which had been vetoed by President Wilson in the previous Congress, also allowed unauthorized immigrants to be deported. Harding and Secretary of Labor James Davis believed that enforcement had to be humane, and Harding often allowed exceptions granting reprieves to thousands of immigrants. Immigration to the United States fell from roughly 800,000 in 1920 to approximately 300,000 in 1922. Though the act was later superseded by the Immigration Act of 1924

The Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson–Reed Act, including the Asian Exclusion Act and National Origins Act (), was a United States federal law that prevented immigration from Asia and set quotas on the number of immigrants from every count ...

, it marked the establishment of the National Origins Formula

The National Origins Formula is an umbrella term for a series of quantitative immigration quotas in the United States used from 1921 to 1965, which restricted immigration from the Eastern Hemisphere on the basis of national origin. These restri ...

.

Veterans

Many World War I veterans were unemployed or otherwise economically distressed when Harding took office. To aid these veterans, the Senate considered passing a law that gave veterans a $1 bonus for each day they had served in the war. Harding opposed payment of a bonus to veterans, arguing that much was already being done for them and that the bill would "break down our Treasury, from which so much is later on to be expected." The Senate sent the bonus bill back to committee, but the issue returned when Congress reconvened in December 1921. A bill providing a bonus, without a means of funding it, was passed by both houses in September 1922. Harding vetoed it, and the veto was narrowly sustained. In August 1921, Harding signed the Sweet Bill, which established a new agency known as the Veterans Bureau. After World War I, 300,000 wounded veterans were in need ofhospitalization

A hospital is a healthcare institution providing patient treatment with specialized health science and auxiliary healthcare staff and medical equipment. The best-known type of hospital is the general hospital, which typically has an emergency ...

, medical care, and job training. To handle the needs of these veterans, the new agency incorporated the War Risk Insurance Bureau, the Federal Hospitalization Bureau, and three other bureaus that dealt with veteran affairs. Harding appointed Colonel Charles R. Forbes

Charles Robert Forbes (February 14, 1877 – April 10, 1952) was a Scottish-American politician and military officer. Appointed the first director of the Veterans' Bureau by President Warren G. Harding on August 9, 1921, Forbes served until F ...

, a decorated war veteran, as the Veteran Bureau's first director. The Veterans Bureau later was incorporated into the Veterans Administration

The United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is a Cabinet-level executive branch department of the federal government charged with providing lifelong healthcare services to eligible military veterans at the 170 VA medical centers an ...

and ultimately the Department of Veterans Affairs

The United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is a Cabinet-level executive branch department of the federal government charged with providing lifelong healthcare services to eligible military veterans at the 170 VA medical centers an ...

.

Farm acts

Farmers were among the hardest hit during the Depression of 1920–21, and prices for farm goods collapsed. The presence of a powerful bipartisan farm bloc led by Senator William S. Kenyon and Congressman Lester J. Dickinson ensured that Congress would address thefarm crisis

A farm crisis is an American term for a time of agricultural recession, low crop prices and low farm incomes. The Interwar farm crisis was an extended period of depressed agricultural incomes from the end of the First to the start of the Second ...

. Harding established the Joint Commission on Agricultural Industry to make recommendations on farm policy, and he signed a series of farm- and food-related laws in 1921 and 1922. Much of the legislation emanated from President Woodrow Wilson's 1919 Federal Trade Commission

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is an independent agency of the United States government whose principal mission is the enforcement of civil (non-criminal) United States antitrust law, antitrust law and the promotion of consumer protection. It ...

report, which investigated and discovered "manipulations, controls, trusts, combinations, or restraints out of harmony with the law or the public interest" in the meat-packing industry

The meat-packing industry (also spelled meatpacking industry or meat packing industry) handles the slaughtering, processing, packaging, and distribution of meat from animals such as cattle, pigs, sheep and other livestock. Poultry is generally n ...

. The first law was the Packers and Stockyards Act

The Packers and Stockyards Act of 1921 (Title 7 of the United States Code, 7 U.S.C. §§ 181-229b; P&S Act) regulates meatpacking, livestock dealers, market agencies, live poultry dealers, and swine contractors to prohibit unfair or deceptive pr ...

, which prohibited packers from engaging in unfair and deceptive practices. Two amendments were made to the Farm Loan Act of 1916 that President Wilson had signed into law, which had expanded the maximum size of rural farm loans. The Emergency Agriculture Credit Act authorized new loans to farmers to help them sell and market livestock. The Capper–Volstead Act, signed by Harding on February 18, 1922, protected farm cooperatives from anti-trust legislation. The Future Trading Act

The Future Trading Act of 1921 (, ) was a United States Act of Congress, approved on August 24, 1921, by the 67th United States Congress intended to institute regulation of grain futures contracts and, particularly, the exchanges on which they w ...

was also enacted, regulating ''puts and calls'', ''bids'', and ''offers'' on futures contract

In finance, a futures contract (sometimes called futures) is a standardized legal contract to buy or sell something at a predetermined price for delivery at a specified time in the future, between parties not yet known to each other. The item tr ...

ing. Later, on May 15, 1922, the Supreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

ruled this legislation unconstitutional, but Congress passed the similar Grain Futures Act

The Grain Futures Act (ch. 369, , ) is a United States federal law enacted September 21, 1922 involving the regulation of trading in certain commodity futures, and causing the establishment of the Grain Futures Administration, a predecessor orga ...

in response. Though sympathetic to farmers and deferential to Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace, Harding was uncomfortable with many of the farm programs since they relied on governmental action, and he sought to weaken the farm bloc by appointing Kenyon to a federal judgeship in 1922.

Highways and radio

During the 1920s, use of electricity became increasingly common, and mass production of the

During the 1920s, use of electricity became increasingly common, and mass production of the automobile

A car, or an automobile, is a motor vehicle with wheels. Most definitions of cars state that they run primarily on roads, Car seat, seat one to eight people, have four wheels, and mainly transport private transport#Personal transport, peopl ...

stimulated industries such as highway construction, rubber, steel, and construction. Congress had passed the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916

The Federal Aid Road Act of 1916 (also known as the Bankhead–Shackleford Act and Good Roads Act), , , was enacted on July 11, 1916, and was the first federal highway funding legislation in the United States. The rise of the automobile at the sta ...

to aid state road-building programs, and Harding favored a further expansion of the federal role in road construction and maintenance. He signed into law the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921

The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921, also called the Phipps Act (, ), sponsored by Sen. Lawrence C. Phipps (R) of Colorado, defined the Federal Aid Road program to develop an immense national highway system. The plan was crafted by the head of t ...

, which allowed states to select interstate and intercounty roads that would receive federal funds. From 1921 to 1923, the federal government spent $162 million on America's highway system, infusing the U.S. economy with a large amount of capital.

Harding and Secretary of Commerce Hoover embraced the emerging medium of the radio

Radio is the technology of communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 3 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmitter connec ...

. In June 1922, Harding became the first president that the American public heard on the radio, delivering a speech in honor of Francis Scott Key

Francis Scott Key (August 1, 1779January 11, 1843) was an American lawyer, author, and poet from Frederick, Maryland, best known as the author of the poem "Defence of Fort M'Henry" which was set to a popular British tune and eventually became t ...

. Secretary of Commerce Hoover took charge of the administration's radio policy. He convened a conference of radio broadcasters in 1922, which led to a voluntary agreement for licensing of radio frequencies

Radio frequency (RF) is the oscillation rate of an alternating electric current or voltage or of a magnetic, electric or electromagnetic field or mechanical system in the frequency range from around to around . This is roughly between the upper ...

through the Commerce Department. Both Harding and Hoover believed that something more than an agreement was needed, but Congress was slow to act, not imposing radio regulation until 1927. Hoover hosted a similar conference on aviation,

but, as with the radio, was unable to win passage of legislation that would have provided for regulation air travel.

Labor issues

Union membership had grown during World War I, and by 1920 union members constituted approximately one-fifth of the labor force. Many employers reduced wages after the war, and some business leaders hoped to destroy the power of organized labor in order to re-establish control over their employees. These policies led to increasing labor tension in the early 1920s. Widespread strikes marked 1922, as labor sought redress for falling wages and increased unemployment. In April, 500,000 coal miners, led byJohn L. Lewis

John Llewellyn Lewis (February 12, 1880 – June 11, 1969) was an American leader of Labor unions in the United States, organized labor who served as president of the United Mine Workers, United Mine Workers of America (UMW) from 1920 to 1960. ...

, struck over wage cuts. Mining executives argued that the industry was seeing hard times; Lewis accused them of trying to break the union. Harding convinced the miners to return to work while a congressional commission looked into their grievances. He also sent out the National Guard and 2,200 deputy U.S. marshals to keep the peace. On July 1, 1922, 400,000 railroad workers went on strike. Harding proposed a settlement that made some concessions, but management objected. Attorney General Daugherty convinced Judge James H. Wilkerson to issue a sweeping injunction to break up the strike. Although there was public support for the Wilkerson injunction, Harding felt it went too far, and had Daugherty and Wilkerson amend it. The injunction succeeded in ending the strike; however, tensions remained high between railroad workers and management for years.

By 1922, the eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses of working time.

The modern movement originated i ...

had become common in American industry. One exception was in steel mill

A steel mill or steelworks is an industrial plant for the manufacture of steel. It may be an integrated steel works carrying out all steps of steelmaking from smelting iron ore to rolled product, but may also be a plant where steel semi-fini ...

s, where workers labored through a twelve-hour workday, seven days a week. Hoover considered this practice barbaric, and convinced Harding to convene a conference of steel manufacturers with a view to ending it. The conference established a committee under the leadership of U.S. Steel

The United States Steel Corporation is an American steel company based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It maintains production facilities at several additional locations in the U.S. and Central Europe.

The company produces and sells steel products, ...

chairman Elbert Gary

Elbert Henry Gary (October 8, 1846August 15, 1927) was an American lawyer, county judge and business executive. He was a founder of U.S. Steel in 1901 alongside J. P. Morgan, William H. Moore, Henry Clay Frick and Charles M. Schwab. The city ...

, which in early 1923 recommended against ending the practice. Harding sent a letter to Gary deploring the result, which was printed in the press, and public outcry caused the manufacturers to reverse themselves and standardize the eight-hour day.

African Americans

Harding spoke of equal rights in his speech when accepting the Republican nomination in 1920:

Harding spoke of equal rights in his speech when accepting the Republican nomination in 1920:

"No majority shall abridge the rights of a minority ..I believe the Black citizens of America should be guaranteed the enjoyment of all their rights, that they have earned their full measure of citizenship bestowed, that their sacrifices in blood on the battlefields of the republic have entitled them to all of freedom and opportunity, all of sympathy and aid that the American spirit of fairness and justice demands.”In June 1921, three days after the massive

Tulsa race massacre

The Tulsa race massacre was a two-day-long white supremacist terrorist massacre that took place in the Greenwood District in Tulsa, Oklahoma, between May 31 and June 1, 1921, when mobs of white residents, some of whom had been appointed as ...

President Harding spoke at the all-black Lincoln University in Pennsylvania. “Despite the demagogues, the idea of our oneness as Americans has risen superior to every appeal to mere class and group,” Harding declared. “And so, I wish it might be in this matter of our national problem of races.” He honored Lincoln alumni who had been among the more than 367,000 black soldiers to fight in the Great War. One Lincoln graduate led the 370th U.S. Infantry, the “Black Devils.” Col. F.A. Denison was the sole black commander of a regiment in France. The President called education critical to solving the issues of racial inequality, but he challenged the students to shoulder their shared responsibility to advance freedom. The government alone, he said, could not magically “take a race from bondage to citizenship in half a century.” He spoke about Tulsa and offered up a simple prayer: “God grant that, in the soberness, the fairness, and the justice of this country, we never see another spectacle like it.”

Notably in an age of severe racial intolerance during the 1920s, Harding did not hold any racial animosity, according to historian Carl S. Anthony.Anthony (July–August, 1998), ''The Most Scandalous President'' In a speech on October 26, 1921, given in segregated Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands, within the wider West Midlands (region), West Midlands region, in England. It is the Lis ...

, Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

Harding advocated civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

for African Americans, becoming the first president to openly advocate black political, educational, and economic equality during the 20th century. In the Birmingham speech, Harding called for African Americans to have equal educational opportunities and greater voting rights in the South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

. The white section of the audience listened in silence while the black section of the segregated audience cheered. Harding, however, openly stated that he was not for black social equality in terms of racial mixing or intermarriage.Christian Science Monitor (October 27, 1921), ''The President's Views On Race'' Harding also spoke on the Great Migration, stating that blacks migrating to the North and West to find employment had actually harmed race relations between blacks and whites.

The three previous presidents had dropped African Americans from several government positions they had previously held, and Harding reversed this policy. African Americans were appointed to high-level positions in the Departments of Labor and Interior, and numerous blacks were hired in other agencies and departments. Eugene P. Trani and Daniel L. Wilson write that Harding did not emphasize appointing African Americans to positions they had traditionally held prior to Wilson's tenure, partly out of a desire to court white Southerners. Harding also disappointed black supporters by not abolishing segregation in federal offices, and through his failure to comment publicly on the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

.

Harding supported Congressman Leonidas Dyer

Leonidas Carstarphen Dyer (June 11, 1871 – December 15, 1957) was an American politician, reformer, civil rights activist, and military officer. A Republican, he served eleven terms in the U.S. Congress as a U.S. Representative from Missouri ...

's federal anti-lynching bill, known as the Dyer Bill

The Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill (1918) was first introduced in the 65th United States Congress by Representative Leonidas C. Dyer, a Republican from St. Louis, Missouri, in the United States House of Representatives as H.R. 11279 in order "to prot ...

, which passed the House of Representatives in January, 1922. When it reached the Senate floor in November 1922, it was filibustered by Southern Democrats, and Senator Lodge withdrew it so as to allow a ship subsidy bill Harding favored to be debated. Many blacks blamed Harding for the Dyer bill's defeat; Harding biographer Robert K. Murray noted that it was hastened to its end by Harding's desire to have the ship subsidy bill considered.

Sheppard–Towner Maternity Act

On November 21, 1921, Harding signed the Sheppard–Towner Maternity Act, the first major federal government social welfare program in the U.S. The law was sponsored byJulia Lathrop

Julia Clifford Lathrop (June 29, 1858 – April 15, 1932) was an Americans, American social reformer in the area of education, social policy, and children's welfare. As director of the United States Children's Bureau from 1912 to 1922, she was th ...

, America's first director of the U.S. Children's Bureau

The United States Children's Bureau is a federal agency founded in 1912, organized under the United States Department of Health and Human Services' Administration for Children and Families. Today, the bureau's operations involve improving child a ...

. The Sheppard–Towner Maternity Act funded almost 3,000 child and health centers, where doctors treated healthy pregnant women and provided preventive care to healthy children. Child welfare workers were sent out to make sure that parents were taking care of their children. Many women were given career opportunities as welfare and social workers. Although the law remained in effect only eight years, it set the trend for New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

social programs during the 1930s.

Deregulation

As part of Harding's belief in limiting the government's role in the economy, he sought to undercut the power of theregulatory agencies

A regulatory agency (regulatory body, regulator) or independent agency (independent regulatory agency) is a government authority that is responsible for exercising autonomous jurisdiction over some area of human activity in a licensing and regu ...

that had been created or strengthened during the Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (1890s–1920s) was a period in the United States characterized by multiple social and political reform efforts. Reformers during this era, known as progressivism in the United States, Progressives, sought to address iss ...

. Among the agencies in existence when Harding came to office were the Federal Reserve (charged with regulating banks), the Interstate Commerce Commission

The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) was a regulatory agency in the United States created by the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. The agency's original purpose was to regulate railroads (and later Trucking industry in the United States, truc ...

(charged with regulating railroads) and the Federal Trade Commission

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is an independent agency of the United States government whose principal mission is the enforcement of civil (non-criminal) United States antitrust law, antitrust law and the promotion of consumer protection. It ...

(charged with regulating other business activities, especially trusts

A trust is a legal relationship in which the owner of property, or any transferable right, gives it to another to manage and use solely for the benefit of a designated person. In the English common law, the party who entrusts the property is k ...

). Harding staffed the agencies with individuals sympathetic to business concerns and hostile to regulation. By the end of his tenure, only the Federal Trade Commission resisted conservative domination. Other federal organizations, like the Railroad Labor Board

The Railroad Labor Board (RLB) was an institution established in the United States of America by the Transportation Act of 1920. This nine-member panel was designed as means of settling wage disputes between railway companies and their employees. ...

, also came under the sway of business interests. In 1921, Harding signed the Willis Graham Act

The Willis Graham Act of 1921 effectively established telephone companies as natural monopolies, citing that "there is nothing to be gained by local competition in the telephone industry." The law effectively released AT&T from terms of its King ...

, which effectively rescinded the Kingsbury Commitment