Greek-Turkish Population Exchange on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey stemmed from the "

By the end of 1922, the vast majority of native

By the end of 1922, the vast majority of native

At the end of World War I one of the Ottomans' foremost generals,

At the end of World War I one of the Ottomans' foremost generals,

In Greece, the population exchange was considered part of the events called the ''

In Greece, the population exchange was considered part of the events called the ''

The Turks and other Muslims of Western Thrace were exempted from this transfer as were the Greeks of

The Turks and other Muslims of Western Thrace were exempted from this transfer as were the Greeks of

"From 'Denying Human Rights and Ethnic Identity' series of Human Rights Watch"

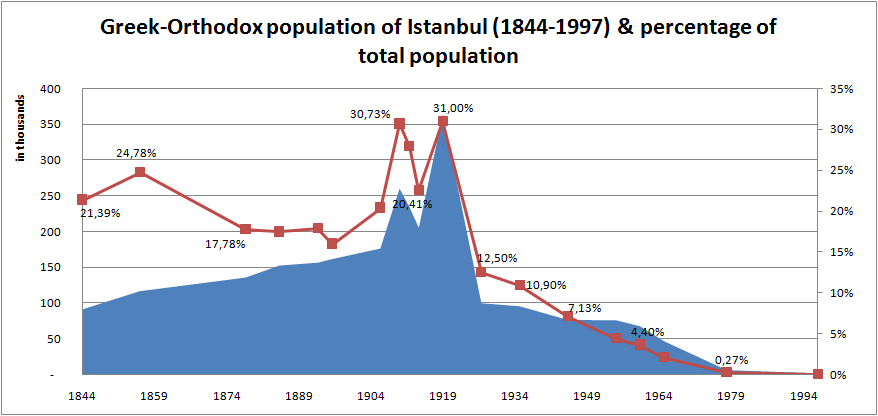

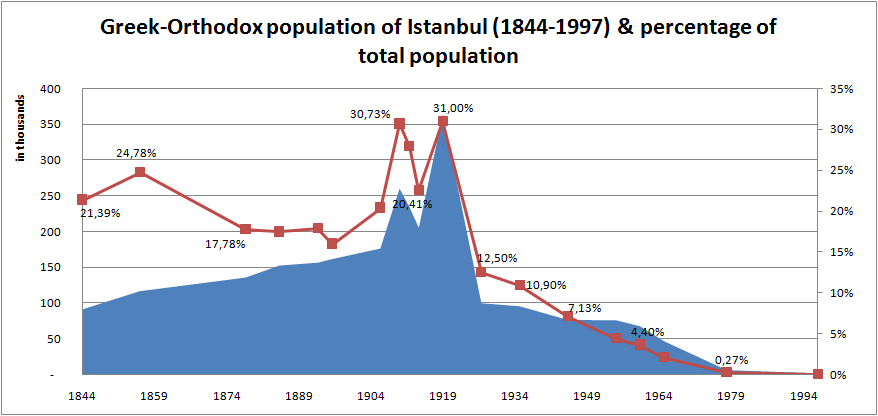

Human Rights Watch, 2 July 2006. The 1955 Istanbul Pogrom and the 1964 expulsion of Istanbul Greeks, caused most of the Greek inhabitants remaining in Istanbul to flee to Greece. The population profile of

The Exchange of Populations: Greece and Turkey

. {{DEFAULTSORT:Population Exchange Between Greece And Turkey Ethnic cleansing in Asia Ethnic cleansing in Europe Deportation History of the Republic of Turkey History of Greece (1909–1924) Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922) 1923 in Greece 1923 in Turkey Greece–Turkey relations Genocide of indigenous peoples in Asia

Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations

The Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations (, ), also known as the Lausanne Convention, was an agreement between the Greece, Greek and Turkey, Turkish governments signed by their representatives in Lausanne on 30 Janua ...

" signed at Lausanne

Lausanne ( , ; ; ) is the capital and largest List of towns in Switzerland, city of the Swiss French-speaking Cantons of Switzerland, canton of Vaud, in Switzerland. It is a hilly city situated on the shores of Lake Geneva, about halfway bet ...

, Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

, on 30 January 1923, by the governments of Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

and Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

. It involved at least 1.6 million people (1,221,489 Greek Orthodox

Greek Orthodox Church (, , ) is a term that can refer to any one of three classes of Christian Churches, each associated in some way with Greek Christianity, Levantine Arabic-speaking Christians or more broadly the rite used in the Eastern Rom ...

from Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, Eastern Thrace

East Thrace or Eastern Thrace, also known as Turkish Thrace or European Turkey, is the part of Turkey that is geographically in Southeast Europe. Turkish Thrace accounts for 3.03% of Turkey's land area and 15% of its population. The largest c ...

, the Pontic Alps

The Pontic Mountains or Pontic Alps (, meaning 'North Anatolian Mountains'), form a mountain range in northern Anatolia, Turkey. They are also known as the "Parhar Mountains" in the local Turkish and Pontic Greek languages. The term ''Parhar'' ...

and the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region spanning Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising parts of Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains, i ...

, and 355,000–400,000 Muslims

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

from Greece), most of whom were forcibly made refugees and ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' (; ; ) describes practices that are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. The phrase is often used in contrast with '' de facto'' ('from fa ...

'' denaturalized

Denaturalization is the loss of citizenship against the will of the person concerned. Denaturalization is often applied to ethnic minorities and political dissidents. Denaturalization can be a penalty for actions considered criminal by the state ...

from their homelands.

On 16 March 1922, Turkish Minister of Foreign Affairs Yusuf Kemal Tengrişenk stated that " e Ankara Government was strongly in favour of a solution that would satisfy world opinion and ensure tranquillity in its own country", and that " was ready to accept the idea of an exchange of populations between the Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

in Asia Minor and the Muslims in Greece". Eventually, the initial request for an exchange of population came from Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos (, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Cretan State, Cretan Greeks, Greek statesman and prominent leader of the Greek national liberation movement. As the leader of the Liberal Party (Greece), Liberal Party, Venizelos ser ...

in a letter he submitted to the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

on 16 October 1922, following Greece's defeat in the Greco-Turkish War and two days after their accession of the Armistice of Mudanya

The Armistice of Mudanya () was an agreement between Turkey (the Grand National Assembly of Turkey) on the one hand, and Italy, France, and Britain on the other hand, signed in the town of Mudanya, in the province of Bursa, on 11 October 1922. Th ...

. The request intended to normalize relations ''de jure'', since the majority of surviving Greek inhabitants of Turkey had fled from recent massacres to Greece by that time. Venizelos proposed a "compulsory exchange of Greek and Turkish populations," and asked Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen (; 10 October 1861 – 13 May 1930) was a Norwegian polymath and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. He gained prominence at various points in his life as an explorer, scientist, diplomat, humanitarian and co-founded the ...

to make the necessary arrangements. The new state of Turkey also envisioned the population exchange as a way to formalize and make permanent the flight of its native Greek Orthodox

Greek Orthodox Church (, , ) is a term that can refer to any one of three classes of Christian Churches, each associated in some way with Greek Christianity, Levantine Arabic-speaking Christians or more broadly the rite used in the Eastern Rom ...

peoples while initiating a new exodus of a smaller number (400,000) of Muslims from Greece as a way to provide settlers for the newly depopulated Orthodox villages of Turkey. Norman M. Naimark

Norman M. Naimark (; born 1944, New York City) is an American historian. He is the Robert and Florence McDonnell Professor of Eastern European Studies at Stanford University, and a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution. He writes on modern Ea ...

claimed that this treaty was the last part of an ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making the society ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it ...

campaign to create an ethnically pure homeland for the Turks. Historian Dinah Shelton similarly wrote that "the Lausanne Treaty completed the forcible transfer of the country's Greeks."

This major compulsory population exchange

Population transfer or resettlement is a type of mass migration that is often imposed by a state policy or international authority. Such mass migrations are most frequently spurred on the basis of ethnicity or religion, but they also occur d ...

, or agreed mutual expulsion, was based mainly upon religious identity, and involved nearly all the indigenous Greek Orthodox Christian

Greek Orthodox Church (, , ) is a term that can refer to any one of three classes of Christian Churches, each associated in some way with Greek Christianity, Levantine Arabic-speaking Christians or more broadly the rite used in the Eastern Roma ...

peoples of Turkey (the Rûm

Rūm ( , collective; singulative: ''Rūmī'' ; plural: ''Arwām'' ; ''Rum'' or ''Rumiyān'', singular ''Rumi''; ), ultimately derived from Greek Ῥωμαῖοι ('' Rhomaioi'', literally 'Romans'), is the endonym of the pre-Islamic inhabi ...

" Roman/Byzantine" millet

Millets () are a highly varied group of small-seeded grasses, widely grown around the world as cereal crops or grains for fodder and human food. Most millets belong to the tribe Paniceae.

Millets are important crops in the Semi-arid climate, ...

), including Armenian

Armenian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Armenia, a country in the South Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Armenians, the national people of Armenia, or people of Armenian descent

** Armenian diaspora, Armenian communities around the ...

and 100,000 Karamanlides

The Karamanlides (; ), also known as Karamanli Greeks: "Turkophone Greeks are called Karamanli Greeks or Karamanlides, and their language and literature is called Karamanli Turkish or Karamanlidika, but the scholarly literature has no equivalent ...

, who were a Turkish-speaking Greek Orthodox Christian

Greek Orthodox Church (, , ) is a term that can refer to any one of three classes of Christian Churches, each associated in some way with Greek Christianity, Levantine Arabic-speaking Christians or more broadly the rite used in the Eastern Roma ...

population. On the other side, most of the native Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

populations of Greece, including Greek-speaking Muslims such as Vallahades

The Vallahades () or Valaades () are a Greek-speaking Muslim population who lived along the river Haliacmon in southwest Greek Macedonia, in and around Anaselitsa (modern Neapoli) and Grevena. They numbered about 17,000 in the early 20th centur ...

and Cretan Turks

The Cretan Muslims or Cretan Turks ( or , or ; , , or ; ) were the Muslim inhabitants of the island of Crete. Their descendants settled principally in Turkey, the Dodecanese Islands under Italian administration (part of Greece since 1947), S ...

, as well as Muslim Roma

Muslim Romani people or Muslim Roma are people who are ethnically Romani and profess Islam. They may also be known as Muslim Gypsies, with some Roma preferring to use the term, not perceiving it as derogatory. They primarily live in the Balkan ...

groups like Sepečides, were distinct from the Greek Orthodox Christian populations involved in the exchange. Each group comprised native peoples, citizens, and in cases even veterans of the state which expelled them, and none had representation in the state purporting to speak for them in the exchange treaty.

Some scholars have criticized the exchange, describing it as a legalized form of mutual ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making the society ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it ...

, while others have defended it, stating that despite its negative aspects, the exchange had an overall positive outcome since it successfully prevented another potential genocide of Greek Orthodox Christians

Greek Orthodox Church (, , ) is a term that can refer to any one of three classes of Christian Churches, each associated in some way with Greek Christianity, Levantine Arabic-speaking Christians or more broadly the rite used in the Eastern Roma ...

in Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

.

Estimated numbers

By the end of 1922, the vast majority of native

By the end of 1922, the vast majority of native Pontian Greeks

The Pontic Greeks (; or ; , , ), also Pontian Greeks or simply Pontians, are an ethnically Greek group indigenous to the region of Pontus, in northeastern Anatolia (modern-day Turkey). They share a common Pontic Greek culture that is dis ...

had already fled Turkey due to the genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

against them (1914–1922), and the Ionia

Ionia ( ) was an ancient region encompassing the central part of the western coast of Anatolia. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements. Never a unified state, it was named after the Ionians who ...

n Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

Ottoman citizens had also fled due to the defeat of the Greek army in the later Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922)

The Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922 was fought between Greece and the Turkish National Movement during the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire in the aftermath of World War I, between 15 May 1919 and 14 October 1922. This conflict was a par ...

, which had led to reprisal killings.

The most common estimates for Ottoman Greeks killed from 1914 to 1923 range from 300,000 to 900,000. For the whole of the period between 1914 and 1922 and for the whole of Anatolia, there are academic estimates of death toll ranging from 289,000 to 750,000. The figure of 750,000 is suggested by political scientist Adam Jones. Scholar Rudolph Rummel

Rudolph Joseph Rummel (October 21, 1932 – March 2, 2014) was an American political scientist, a statistician and professor at Indiana University, Yale University, and University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. He spent his career studying data on collect ...

compiled various figures from several studies to estimate lower and higher bounds for the death toll between 1914 and 1923. He estimates that 384,000 Greeks were exterminated from 1914 to 1918, and 264,000 from 1920 to 1922, with the total number reaching 648,000. Historian Constantine G. Hatzidimitriou writes that "loss of life among Anatolian Greeks during the WWI period and its aftermath was approximately 735,370". The pre-war Greek population may have been closer to 2.4 million. The number of Armenians killed varies from a low of 300,000 to 1.5 million. The estimate for Assyrians is 275–300,000.

According to some calculations, during the autumn of 1922, around 900,000 Greeks arrived in Greece. According to Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen (; 10 October 1861 – 13 May 1930) was a Norwegian polymath and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. He gained prominence at various points in his life as an explorer, scientist, diplomat, humanitarian and co-founded the ...

, before the final stage in 1922, of the 900,000 Greek refugees

Greek refugees is a collective term used to refer to the more than one million Greek Orthodox natives of Asia Minor, Thrace and the Black Sea areas who fled during the Greek genocide (1914-1923) and Greece's later defeat in the Greco-Turkish W ...

, a third were from Eastern Thrace

East Thrace or Eastern Thrace, also known as Turkish Thrace or European Turkey, is the part of Turkey that is geographically in Southeast Europe. Turkish Thrace accounts for 3.03% of Turkey's land area and 15% of its population. The largest c ...

, with the other two thirds being from Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

.

The estimate for the Greeks living within the present day borders of Turkey in 1914 could be as high as 2.130 million, a figure higher than the 1.8 million Greeks in the Ottoman census of 1910 which included Western Thrace

Western Thrace or West Thrace (, '' ytikíThráki'' ), also known as Greek Thrace or Aegean Thrace, is a geographical and historical region of Greece, between the Nestos and Evros rivers in the northeast of the country; East Thrace, which lie ...

, Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

and Epirus

Epirus () is a Region#Geographical regions, geographical and historical region, historical region in southeastern Europe, now shared between Greece and Albania. It lies between the Pindus Mountains and the Ionian Sea, stretching from the Bay ...

based on the number of Greeks who left for Greece just before World War I and the 1.3 million who arrived in the population exchanges of 1923, and the 300–900,000 estimated to have been massacred. A revised count suggests 620,000 in Eastern Thrace

East Thrace or Eastern Thrace, also known as Turkish Thrace or European Turkey, is the part of Turkey that is geographically in Southeast Europe. Turkish Thrace accounts for 3.03% of Turkey's land area and 15% of its population. The largest c ...

including Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

(260,000, 30% of the city's population at the time), 550,000 Pontic Greeks

The Pontic Greeks (; or ; , , ), also Pontian Greeks or simply Pontians, are an ethnically Greek group indigenous to the region of Pontus, in northeastern Anatolia (modern-day Turkey). They share a common Pontic Greek culture that is di ...

, 900,000 Anatolian Greeks and 60,000 Cappadocian Greeks

The Cappadocian Greeks (; ), or simply Cappadocians, are an ethnic Greek community native to the geographical region of Cappadocia in central-eastern Anatolia; roughly the Nevşehir and Kayseri provinces and their surroundings in modern-day Turk ...

. Arrivals in Greece from the exchange numbered 1,310,000 according to the map (in this article) with figures below: 260,000 from Eastern Thrace (100,000 had already left between 1912 and 1914 after the Balkan Wars), 20,000 from the southern shore of the Sea of Marmara

The Sea of Marmara, also known as the Sea of Marmora or the Marmara Sea, is a small inland sea entirely within the borders of Turkey. It links the Black Sea and the Aegean Sea via the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits, separating Turkey's E ...

, 650,000 from Anatolia, 60,000 from Cappadocia

Cappadocia (; , from ) is a historical region in Central Anatolia region, Turkey. It is largely in the provinces of Nevşehir, Kayseri, Aksaray, Kırşehir, Sivas and Niğde. Today, the touristic Cappadocia Region is located in Nevşehir ...

, 280,000 Pontic Greeks, 40,000 left Constantinople (the Greeks there were permitted to stay, but those who had fled during the war were not allowed to return).

Additionally, 50,000 Greeks came from the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region spanning Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising parts of Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains, i ...

, 50,000 from Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

and 12,000 from Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

, almost 1.42 million from all regions. About 340,000 Greeks remained in Turkey, 220,000 of them in Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

in 1924.

By 1924, the Christian population of Turkey proper had been reduced from 4.4 million in 1912 to 700,000 (50% of the pre-war Christians had been killed), 350,000 Armenians, 50,000 Assyrians and the rest Greeks, 70% in Constantinople; and by 1927 to 350,000, mostly in Istanbul. In modern times the percentage of Christians in Turkey has declined from 20 to 25 percent in 1914 to 3–5.5 percent in 1927, to 0.3–0.4% today roughly translating to 200,000–320,000 devotees. This was due to events that had a significant impact on the country's demographic structure, such as the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the genocide of Assyrians, Greeks, and Armenians, and the population exchange between Greece and Turkey in 1923.

Historical background

The Greek–Turkish population exchange came out of the Turkish and Greek militaries' treatment of the Christian minorities and Muslim majorities, respectively, in Asia Minor during theGreco-Turkish War (1919–1922)

The Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922 was fought between Greece and the Turkish National Movement during the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire in the aftermath of World War I, between 15 May 1919 and 14 October 1922. This conflict was a par ...

that followed the Allied Powers' authorization of a Greek zone of occupation in the defeated Ottoman Empire. This Greek occupation was designed to protect remaining Christian minorities, who had been massacred repeatedly in the Ottoman Empire before and during World War I: Adana massacre of 1909

The Adana massacres (, ) occurred in the Adana Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire in April 1909. Many Armenians were slain by Ottoman Muslims in the city of Adana as the Ottoman countercoup of 1909 triggered a series of pogroms throughout the prov ...

, Armenian genocide

The Armenian genocide was the systematic destruction of the Armenians, Armenian people and identity in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Spearheaded by the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), it was implemented primarily t ...

of 1914–1923, Greek genocide

The Greek genocide (), which included the Pontic genocide, was the systematic killing of the Christian Ottoman Greek population of Anatolia, which was carried out mainly during World War I and its aftermath (1914–1922) – including the T ...

1914–1922. But, instead, it unleashed further massacres both of these Christians and now also of Muslims

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

as both armies sought to secure their rule by eliminating any inhabitants whose existence could justify unfavorable borders. This continued, now in both directions, a process of ethnic cleansing in Asia Minor that had been conducted initially by the Ottoman state against its minorities during World War I. On January 31, 1917, the Chancellor of Germany, allied with the Ottomans during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, was reporting that:

At the end of World War I one of the Ottomans' foremost generals,

At the end of World War I one of the Ottomans' foremost generals, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk ( 1881 – 10 November 1938) was a Turkish field marshal and revolutionary statesman who was the founding father of the Republic of Turkey, serving as its first President of Turkey, president from 1923 until Death an ...

, continued the fight against the attempted Allied occupation of Turkey in the Turkish War of Independence

, strength1 = May 1919: 35,000November 1920: 86,000Turkish General Staff, ''Türk İstiklal Harbinde Batı Cephesi'', Edition II, Part 2, Ankara 1999, p. 225August 1922: 271,000Celâl Erikan, Rıdvan Akın: ''Kurtuluş Savaşı tarih ...

. The surviving Christian minorities within Turkey, particularly the Armenians and the Greeks, had sought protection from the Allies and thus continued to be seen as an internal problem, and as an enemy, by the Turkish National Movement

The Turkish National Movement (), also known as the Anatolian Movement (), the Nationalist Movement (), and the Kemalists (, ''Kemalciler'' or ''Kemalistler''), included political and military activities of the Turkish revolutionaries that resu ...

. This was exacerbated by the Allies authorizing Greece to occupy Ottoman regions (Occupation of Smyrna

The city of Smyrna (modern-day İzmir) and surrounding areas were under Greek military occupation from 15 May 1919 until 9 September 1922. The Allied Powers authorized the occupation and creation of the Zone of Smyrna () during negotiations re ...

) with a large surviving Greek population in 1919 and by an Allied proposal to protect the remaining Armenians by creating an independent state for them (Wilsonian Armenia

Wilsonian Armenia () was the unimplemented boundary configuration of the First Republic of Armenia in the Treaty of Sèvres, as drawn by President of the United States, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, Woodrow Wilson's United States State Departm ...

) within the former Ottoman realm. The Turkish Nationalists' reaction to these events led directly to the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922)

The Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922 was fought between Greece and the Turkish National Movement during the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire in the aftermath of World War I, between 15 May 1919 and 14 October 1922. This conflict was a par ...

and the continuation of the Armenian genocide

The Armenian genocide was the systematic destruction of the Armenians, Armenian people and identity in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Spearheaded by the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), it was implemented primarily t ...

and Greek genocide

The Greek genocide (), which included the Pontic genocide, was the systematic killing of the Christian Ottoman Greek population of Anatolia, which was carried out mainly during World War I and its aftermath (1914–1922) – including the T ...

. By the time of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's capture of Smyrna in September 1922, over a million Greek orthodox Ottoman subjects had fled their homes in Turkey. A formal peace agreement was signed with Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

after months of negotiations in Lausanne

Lausanne ( , ; ; ) is the capital and largest List of towns in Switzerland, city of the Swiss French-speaking Cantons of Switzerland, canton of Vaud, in Switzerland. It is a hilly city situated on the shores of Lake Geneva, about halfway bet ...

on July 24, 1923. Two weeks after the treaty, the Allied Powers turned over Istanbul to the Nationalists, marking the final departure of occupation armies from Anatolia and provoking another flight of Christian minorities to Greece.

On October 29, 1923, the Grand Turkish National Assembly announced the creation of the Republic of Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

, a state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

that would encompass most of the territories claimed by Mustafa Kemal in his National Pact of 1920.

The state of Turkey was headed by Mustafa Kemal's People's Party, which later became the Republican People's Party

The Republican People's Party (RPP; , CHP ) is a Kemalism, Kemalist and Social democracy, social democratic political party in Turkey. It is the oldest List of political parties in Turkey, political party in Turkey, founded by Mustafa Kemal ...

. The end of the War of Independence brought new administration to the region, but also brought new problems considering the demographic reconstruction of cities and towns, many of which had been abandoned by fleeing minority Christians. The Greco-Turkish War left many of the settlements plundered and in ruins.

Meanwhile, after the Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars were two conflicts that took place in the Balkans, Balkan states in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan states of Kingdom of Greece (Glücksburg), Greece, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Montenegro, M ...

, Greece had almost doubled its territory, and the population of the state had risen from approximately 3.7 million to 4.8 million. With this newly annexed population, the proportion of non-Greek minority groups in Greece rose to 13%, and following the end of the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, it had increased to 20%. Most of the ethnic populations in these annexed territories were Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

, but were not necessarily Turkish in ethnicity. This is particularly true in the case of ethnic Albanians

The Albanians are an ethnic group native to the Balkan Peninsula who share a common Albanian ancestry, Albanian culture, culture, Albanian history, history and Albanian language, language. They are the main ethnic group of Albania and Kosovo, ...

who inhabited the Çamëria

Chameria (; , ''Tsamouriá'') is a term used today mostly by Albanians to refer to parts of the coastal region of Epirus in southern Albania and Greece, traditionally associated with the Albanian ethnic subgroup of the Chams.Elsie, Robert and Be ...

(Greek: Τσαμουριά) region of Epirus

Epirus () is a Region#Geographical regions, geographical and historical region, historical region in southeastern Europe, now shared between Greece and Albania. It lies between the Pindus Mountains and the Ionian Sea, stretching from the Bay ...

. During the deliberations held at Lausanne, the question of exactly who was Greek, Turkish or Albanian was routinely brought up. Greek and Albanian representatives determined that the Albanians in Greece, who mostly lived in the northwestern part of the state, were not all mixed, and were distinguishable from the Turks

Turk or Turks may refer to:

Communities and ethnic groups

* Turkish people, or the Turks, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

* Turkish citizen, a citizen of the Republic of Turkey

* Turkic peoples, a collection of ethnic groups who speak Turkic lang ...

. The government in Ankara

Ankara is the capital city of Turkey and List of national capitals by area, the largest capital by area in the world. Located in the Central Anatolia Region, central part of Anatolia, the city has a population of 5,290,822 in its urban center ( ...

still expected a thousand "Turkish-speakers" from the Çamëria to arrive in Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

for settlement in Erdek

Erdek is a municipality and district of Balıkesir Province, Turkey. Its area is 307 km2, and its population is 31,902 (2022). Located on the Kapıdağ Peninsula, on the north coast of the Gulf of Erdek at the south of the Sea of Marmara, ...

, Ayvalık

Ayvalık (), formerly also known as Kydonies (), is a municipality and Districts of Turkey, district of Balıkesir Province, Turkey. Its area is 305 km2, and its population is 75,126 (2024). It is a seaside town on the northwestern Aegean Se ...

, Menteşe, Antalya

Antalya is the fifth-most populous city in Turkey and the capital of Antalya Province. Recognized as the "capital of tourism" in Turkey and a pivotal part of the Turkish Riviera, Antalya sits on Anatolia's southwest coast, flanked by the Tau ...

, Senkile, Mersin

Mersin () is a large city and port on the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean coast of Mediterranean Region, Turkey, southern Turkey. It is the provincial capital of the Mersin Province (formerly İçel). It is made up of four district governorates ...

, and Adana

Adana is a large city in southern Turkey. The city is situated on the Seyhan River, inland from the northeastern shores of the Mediterranean Sea. It is the administrative seat of the Adana Province, Adana province, and has a population of 1 81 ...

. Ultimately, the Greek authorities decided to deport thousands of Muslims from Thesprotia

Thesprotia (; , ) is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the Epirus region. Its capital and largest town is Igoumenitsa. Thesprotia is named after the Thesprotians, an ancient Greek tribe that inhabited the region in antiquity.

His ...

, Larissa

Larissa (; , , ) is the capital and largest city of the Thessaly region in Greece. It is the fifth-most populous city in Greece with a population of 148,562 in the city proper, according to the 2021 census. It is also the capital of the Larissa ...

, Langadas

Lagkadas (, ) is a town and municipality in the northeast part of Thessaloniki regional unit, Greece. There are 37,022 residents in the municipality and 8,447 of them live in the community of Lagkadas (2021).

Lagkadas is located northeast of Thess ...

, Drama

Drama is the specific Mode (literature), mode of fiction Mimesis, represented in performance: a Play (theatre), play, opera, mime, ballet, etc., performed in a theatre, or on Radio drama, radio or television.Elam (1980, 98). Considered as a g ...

, Edessa

Edessa (; ) was an ancient city (''polis'') in Upper Mesopotamia, in what is now Urfa or Şanlıurfa, Turkey. It was founded during the Hellenistic period by Macedonian general and self proclaimed king Seleucus I Nicator (), founder of the Sel ...

, Serres

Serres ( ) is a city in Macedonia, Greece, capital of the Serres regional unit and second largest city in the region of Central Macedonia, after Thessaloniki.

Serres is one of the administrative and economic centers of Northern Greece. The c ...

, Florina

Florina (, ''Flórina''; known also by some alternative names) is a town and municipality in the mountainous northwestern Macedonia, Greece. Its motto is, 'Where Greece begins'.

The town of Florina is the capital of the Florina regional uni ...

, Kilkis

Kilkis () is a city in Central Macedonia, Greece. As of 2021 there were 24,130 people living in the city proper, 27,493 people living in the municipal unit, and 45,308 in the municipality of Kilkis. It is also the capital city of the regional un ...

, Kavala

Kavala (, ''Kavála'' ) is a city in northern Greece, the principal seaport of eastern Macedonia and the capital of Kavala regional unit.

It is situated on the Bay of Kavala, across from the island of Thasos and on the A2 motorway, a one-and ...

, and Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

. Between 1923 and 1930, the infusion of these refugees into Turkey would dramatically alter Anatolian society. By 1927, Turkish officials had settled 32,315 individuals from Greece in the province of Bursa alone.

The road to the exchange

According to some sources, the population exchange, albeit messy and dangerous for many, was executed fairly quickly by respected supervisors. If the goal of the exchange was to ostensibly achieve religious homogeneity, then this was achieved by both Turkey and Greece. For example, in 1906, nearly 20 percent of the population of present-day Turkey was non-Muslim, but by 1927, only 2.6 percent was. The architect of the exchange wasFridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen (; 10 October 1861 – 13 May 1930) was a Norwegian polymath and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. He gained prominence at various points in his life as an explorer, scientist, diplomat, humanitarian and co-founded the ...

, commissioned by the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

. As the first official high commissioner for refugees, Nansen proposed and supervised the exchange, taking into account the interests of Greece, Turkey, and West European powers. As an experienced diplomat with experience resettling Russian and other refugees after the First World War, Nansen had also created a new travel document for displaced persons of the World War in the process. He was chosen to be in charge of the peaceful resolution of the Greek-Turkish war of 1919–22. Although a compulsory exchange on this scale had never been attempted in modern history, Balkan precedents, such as the Greco-Bulgarian population exchange of 1919, were available. Because of the unanimous decision by the Greek and Turkish governments that minority protection would not suffice to ameliorate ethnic tensions after the First World War, population exchange was promoted as the only viable option.

According to representatives from Ankara

Ankara is the capital city of Turkey and List of national capitals by area, the largest capital by area in the world. Located in the Central Anatolia Region, central part of Anatolia, the city has a population of 5,290,822 in its urban center ( ...

, the "amelioration of the lot of the minorities in Turkey' depended 'above all on the exclusion of every kind of foreign intervention and of the possibility of provocation coming from outside'.

This could be achieved most effectively with an exchange, and 'the best guarantees for the security and development of the minorities remaining' after the exchange 'would be those supplied both by the laws of the country and by the liberal policy of Turkey with regard to all communities whose members have not deviated from their duty as Turkish citizens'. An exchange would also be useful as a response to violence in the Balkans; 'there were', in any event, 'over a million Turks without food or shelter in countries in which neither Europe nor America took nor was willing to take any interest'.

The population exchange was seen as the best form of minority protection as well as "the most radical and humane remedy" of all. Nansen believed that what was on the negotiating table at Lausanne was not ethno-nationalism

Ethnic nationalism, also known as ethnonationalism, is a form of nationalism wherein the nation and nationality are defined in terms of ethnicity, with emphasis on an ethnocentric (and in some cases an ethnostate/ethnocratic) approach to variou ...

, but rather, a "question" that "demanded 'quick and efficient' resolution without a minimum of delay." He believed that economic component of the problem of Greek and Turkish refugees deserved the most attention: "Such an exchange will provide Turkey immediately and in the best conditions with the population necessary to continue the exploitation of the cultivated lands which the departed Greek populations have abandoned. The departure from Greece of its Muslim citizens would create the possibility of rendering self-supporting a great proportion of the refugees now concentrated in the towns and in different parts of Greece". Nansen recognized that the difficulties were truly "immense", acknowledging that the population-exchange would require "the displacement of populations of many more than 1,000,000 people". He advocated: "uprooting these people from their homes, transferring them to a strange new country, ... registering, valuing and liquidating their individual property which they abandon, and ... securing to them the payment of their just claims to the value of this property".

The agreement promised that the possessions of the refugees would be protected and allowed migrants to carry "portable" belongings freely with themselves. It was required that possessions not carried across the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans and Anatolia, and covers an area of some . In the north, the Aegean is connected to the Marmara Sea, which in turn con ...

be recorded in lists; these lists were to be submitted to both governments for reimbursement. After a commission was established to deal with the particular issue of belongings (mobile and immobile) of the populations, this commission would decide the total sum to pay persons for their immovable belongings (houses, cars, land, etc.) It was also promised that in their new settlement, the refugees would be provided with new possessions totaling the ones they had left behind. Greece and Turkey would calculate the total value of a refugee's belongings and the country with a surplus would pay the difference to the other country. All possessions left in Greece belonged to the Greek state and all the possessions left in Turkey belonged to the Turkish state. Because of the difference in nature and numbers of the populations, the possessions left behind by the Greek elite of the economic classes in Anatolia was greater than the possessions of the Muslim farmers in Greece.

Refugee camps

The Refugee Commission had no useful plan to follow to resettle the refugees. Having arrived in Greece for the purpose of settling the refugees on land, the commission had no statistical data either about the number of the refugees or the number of available acres. When the Commission arrived in Greece, the Greek government had already settled provisionally 72,581 farming families, almost entirely inMacedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

, where the houses abandoned by the exchanged Muslims and the fertility of the land made their establishment practicable and auspicious.

In Turkey, the property abandoned by the Greeks was often looted by arriving immigrants before the influx of immigrants of the population exchange. As a result, it was quite difficult to settle refugees in Anatolia, since many of these homes had been occupied by people displaced by war before the government could seize them.

Political and economic effects of the exchange

The more than 1,250,000 refugees who left Turkey for Greece after the war in 1922, through different mechanisms, contributed to the unification of elites underauthoritarian regime

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in democracy, separation of powers, civil liberties, and ...

s in Turkey and Greece. In Turkey, the departure of the independent and strong economic elites, i.e. the Greek Orthodox populations, left the dominant state elites unchallenged. In fact, Caglar Keyder noted that "what this drastic measure reek-Turkish population exchangeindicates is that during the war years Turkey lost ... round 90 percent of the pre-war

Round or rounds may refer to:

Mathematics and science

* Having no sharp corners, as an ellipse, circle, or sphere

* Rounding, reducing the number of significant figures in a number

* Round number, ending with one or more zeroes

* Round (crypto ...

commercial class, such that when the Republic was formed, the bureaucracy found itself unchallenged". The emerging business groups that supported the Free Republican Party in 1930 could not prolong the rule of a single-party without an opposition. Transition to multiparty politics depended on the creation of stronger economic groups in the mid-1940s, which was stifled due to the exodus of the Greek middle and upper economic classes. Hence, if the groups of Orthodox Christians had stayed in Turkey after the formation of the nation-state, then there would have been a faction of society ready to challenge the emergence of single-party rule in Turkey. Although it is very unlikely that an opposition based on an economic elite made up of an ethnic and religious minority would have been accepted as a legitimate political party by the majority population.

In Greece, contrary to Turkey, the arrival of the refugees broke the dominance of the monarchy and old politicians relative to the Republicans. In the elections of the 1920s most of the newcomers supported Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos (, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Cretan State, Cretan Greeks, Greek statesman and prominent leader of the Greek national liberation movement. As the leader of the Liberal Party (Greece), Liberal Party, Venizelos ser ...

. In December 1916, during the ''Noemvriana

The ''Noemvriana'' (, "November Events") of , also called the Greek Vespers, was a political dispute, rooted in Greece's neutrality in World War I, that escalated into an armed confrontation in Athens between the Greek royalist government an ...

'', refugees from an earlier wave of persecution in the Ottoman Empire had been attacked by royalist troops as Venizelists

Venizelism () was one of the major political movements in Greece beginning from the 1910s. The movement first formed under Eleftherios Venizelos in the 1910s and saw a resurgence of support in the 1960s when Georgios Papandreou united a coaliti ...

, which contributed to the perception in the 1920s that the Venizelist side of the National Schism was much friendlier to refugees from Anatolia than the royalist side. For their political stance and their "Anatolian customs" (cuisine, music, etc.), the refugees often faced discrimination by part of the local Greek population. The fact that the refugees spoke dialects of Greek that sounded exotic and strange in Greece marked them out, and they were often seen as rivals by the locals for land and jobs.Kostis, Kostas ''History's Spoiled Children'', Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018 p. 278 The arrival of so many people in so short a period of time imposed significant costs on the Greek economy such as building housing and schools, importing enough food, providing health care, etc.Kostis, Kostas ''History's Spoiled Children'', Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018 p. 279 Greece needed a 12,000,000 franc loan from the Refugee Settlement Commission of the League of Nations as there was not enough money in the Greek treasury to handle these costs. Increasing the problems was the Immigration Act of 1924

The Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson–Reed Act, including the Asian Exclusion Act and National Origins Act (), was a United States federal law that prevented immigration from Asia and set quotas on the number of immigrants from every count ...

passed by the U.S. Congress, which sharply limited the number of immigrants the United States was willing to take annually, which removed one of the traditional "safety valves" that Greece had in periods of high unemployment. In the 1920s, the refugees, most of whom went to Greek Macedonia, were known for their staunch loyalty to Venizelism

Venizelism () was one of the major political movements in Greece beginning from the 1910s. The movement first formed under Eleftherios Venizelos in the 1910s and saw a resurgence of support in the 1960s when Georgios Papandreou united a coaliti ...

. According to the 1928 census 45% of the population in Macedonia were refugees, while the figure was 35% in Greek Thrace, 19% in Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, and 18% in the islands of the Aegean Sea;Kostis, Kostas ''History's Spoiled Children'', Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018 p. 276 overall, the census showed that 1,221,849 people or 20% of the Greek population were refugees.

The majority of the refugees who settled in cities like Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

and Athens were deliberately placed by the authorities in shantytown

A shanty town, squatter area, squatter settlement, or squatter camp is a settlement of improvised buildings known as shanties or shacks, typically made of materials such as mud and wood, or from cheap building materials such as corrugated iron s ...

s on the outskirts of the cities in order to subject them to police control. The refugee communities in the cities were seen by the authorities as centers of poverty and crime that might also become centers of social unrest.Kostis, Kostas ''History's Spoiled Children'', Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018 p. 261 About 50% of the refugees were settled in urban areas. Regardless of whether they settled in urban or rural areas, the vast majority of the refugees arrived in Greece impoverished and often sickly, placing enormous demands on the Greek health care system. Tensions between locals and the refugees for jobs sometimes turned violent, and in 1924, the Interior Minister, General Georgios Kondylis

Georgios Kondylis (, romanized: ''Geórgios Kondýlis''; 14 August 1878 – 1 February 1936) was a Greek general, politician and prime minister of Greece. He was nicknamed ''Keravnos'', Greek for " thunder" or " thunderbolt".

Military ca ...

, used a force of refugees as strike-breakers.Kostis, Kostas ''History's Spoiled Children'', Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018 p. 262 In rural areas, there were demands that the land that once belonged to the Muslims that had been expelled should go to veterans instead of the refugees. Demagogic politicians quite consciously stoked tensions, portraying refugees as a parasitical class who by their very existence were overwhelming public services, as a way to gain votes.

As the largest number of refugees were settled in Macedonia, which was part of the "new Greece" (i.e. the areas gained after the Balkan Wars of 1912–13), they shared in the resentment against the way that men from "Old Greece

The term Old Greece (, ) is a geographical, cultural, and political term used at different times for southern and predominantly mainland Greece.

Classical studies

In Classical studies, "Old Greece" is the area of Greece defined as the core of the ...

" (i.e. the pre-1912 Kingdom of Greece) dominated politics, the civil service, judiciary, etc., and tended to treat "new Greece" like it was a conquered country. In general, people from "Old Greece" tended to be more royalist in their sympathies while people from "new Greece" tended to be more Venizelist. The fact that in 1916 King Constantine I

Constantine I (27 February 27222 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was a Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337 and the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity. He played a Constantine the Great and Christianity, pivotal ro ...

had contemplated giving up "new "Greece" to Bulgaria as a way of weakening the Venizelist movement had greatly increased the hostility felt in "new Greece" towards the House of Glücksburg

The House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, also known by its short name as the House of Glücksburg, is the senior surviving branch of the German House of Oldenburg, one of Europe's oldest royal houses. Oldenburg house members hav ...

. Furthermore, the fact that it was under King Constantine's leadership that Greece had been defeated in 1922 together with the indifference shown by Greek authorities in Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; , or ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, Turkey. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna ...

(modern İzmir, Turkey) towards rescuing the threatened Greek communities of Anatolia in the last stages of the war cemented the hatred of the refugees towards the monarchy. Aristeidis Stergiadis, the Greek High Commissioner in Smyrna remarked in August 1922 as the Turkish Army advanced upon the city: "Better that they stay here and be slain by Kemal taturk because if they go to Athens they will overthrow everything".

However, increasing grievances of the refugees caused some of the immigrants to shift their allegiance to the Communist Party and contributed to its increasing strength. The impoverished slum districts of Thessaloniki where the refugees were concentrated became strongholds of the Greek Communist Party

The Communist Party of Greece (, ΚΚΕ; ''Kommounistikó Kómma Elládas'', KKE) is a Marxist–Leninist political party in Greece. It was founded in 1918 as the Socialist Workers' Party of Greece (SEKE) and adopted its current name in Novem ...

in the Great Depression together with the rural areas of Macedonia where tobacco farming was the main industry.Kostis, Kostas ''History's Spoiled Children'', Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018 p. 277 In May 1936, a strike of the tobacco farmers in Macedonia organized by the Communists led to a rebellion that saw the government lose control of Thessaloniki for a time. Prime Minister Ioannis Metaxas

Ioannis Metaxas (; 12 April 187129 January 1941) was a Greek military officer and politician who was dictator of Greece from 1936 until his death in 1941. He governed constitutionally for the first four months of his tenure, and thereafter as th ...

, with the support of the King, responded to the communists by establishing an authoritarian regime in 1936, the 4th of August Regime. In these ways, the population exchange indirectly facilitated changes in the political regimes of Greece and Turkey during the interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

.

Many immigrants died of epidemic illnesses during the voyage and brutal waiting for boats for transportation. The death rate during the immigration was four times higher than the birth rate. In the first years after their arrival, the Turkish immigrants from Greece were inefficient in economic production, having only brought with them agricultural skills in tobacco production. This created considerable economic loss in Anatolia for the new Turkish Republic. On the other hand, the Greek populations that left were skilled workers who engaged in transnational trade and business, as per previous capitulations policies of the Ottoman Empire.

Effect on other ethnic populations

While current scholarship defines the Greek-Turkish population exchange in terms of religious identity, the population exchange was much more complex than this. Indeed, the population exchange, embodied in the Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations at the Lausanne Conference of January 30, 1923, was based on ethnic identity. The population exchange made it legally possible for bothTurkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

and Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

to cleanse their ethnic minorities in the formation of the nation-state

A nation state, or nation-state, is a political entity in which the state (a centralized political organization ruling over a population within a territory) and the nation (a community based on a common identity) are (broadly or ideally) con ...

. Nonetheless, religion was utilized as a legitimizing factor or a "safe criterion" in marking ethnic groups as Turkish or as Greek in the population exchange. As a result, the Greek-Turkish population exchange did exchange the Greek Orthodox

Greek Orthodox Church (, , ) is a term that can refer to any one of three classes of Christian Churches, each associated in some way with Greek Christianity, Levantine Arabic-speaking Christians or more broadly the rite used in the Eastern Rom ...

population of Anatolia, Turkey and the Muslim population of Greece. However, due to the heterogeneous nature of these former Ottoman lands, many other ethnic groups posed social and legal challenges to the terms of the agreement for years after its signing. Among these were the Protestant and Catholic Greeks, the Arabs

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of yea ...

, Albanians

The Albanians are an ethnic group native to the Balkan Peninsula who share a common Albanian ancestry, Albanian culture, culture, Albanian history, history and Albanian language, language. They are the main ethnic group of Albania and Kosovo, ...

, Russians

Russians ( ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Eastern Europe. Their mother tongue is Russian language, Russian, the most spoken Slavic languages, Slavic language. The majority of Russians adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church ...

, Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Southeastern Europe who share a common Serbian Cultural heritage, ancestry, Culture of Serbia, culture, History of Serbia, history, and Serbian lan ...

, Romanians

Romanians (, ; dated Endonym and exonym, exonym ''Vlachs'') are a Romance languages, Romance-speaking ethnic group and nation native to Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. Sharing a Culture of Romania, ...

of the Greek Orthodox religion; the Albanian

Albanian may refer to:

*Pertaining to Albania in Southeast Europe; in particular:

**Albanians, an ethnic group native to the Balkans

**Albanian language

**Albanian culture

**Demographics of Albania, includes other ethnic groups within the country ...

, Bulgarian, Greek Muslims

Greek Muslims, also known as Grecophone Muslims, are Muslims of Greeks, Greek ethnic origin whose adoption of Islam (and often the Turkish language and identity in more recent times) dates either from the contact of early Arabic dynasties of th ...

of Epirus

Epirus () is a Region#Geographical regions, geographical and historical region, historical region in southeastern Europe, now shared between Greece and Albania. It lies between the Pindus Mountains and the Ionian Sea, stretching from the Bay ...

, and the Turkish-speaking Greek Orthodox. In Thessaloniki, which had the largest Jewish population in the Balkans, competition emerged between the Sephardic Jews

Sephardic Jews, also known as Sephardi Jews or Sephardim, and rarely as Iberian Peninsular Jews, are a Jewish diaspora population associated with the historic Jewish communities of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) and their descendant ...

who spoke Ladino

Ladino, derived from Latin, may refer to:

* Judeo-Spanish language (ISO 639–3 lad), spoken by Sephardic Jews

*Ladino people, a socio-ethnic category of Mestizo or Hispanicized people in Central America especially in Guatemala

* Black ladinos, a ...

and the refugees for jobs and businesses.Kostis, Kostas ''History's Spoiled Children'', Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018 p. 274 Owing to an increase in antisemitism, many of the Jews of Thessaloniki became Zionists

Zionism is an ethnocultural nationalist movement that emerged in Europe in the late 19th century that aimed to establish and maintain a national home for the Jewish people, pursued through the colonization of Palestine, a region roughly cor ...

and immigrated to the Palestine Mandate

The Mandate for Palestine was a League of Nations mandate for British administration of the territories of Palestine and Transjordanwhich had been part of the Ottoman Empire for four centuriesfollowing the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in Wo ...

in the interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

. Because the refugees tended to vote for the Venizelist Liberals, the Jews and remaining Muslims in Thrace and Macedonia tended to vote for the anti-Venizelist parties. A group of refugee merchants in Thessaloniki founded the republican and anti-Semitic EEE (''Ethniki Enosis Ellados''-National Union of Greece

The National Union of Greece (, ΕΕΕ; ''Ethniki Enosis Ellados'', EEE) was a far-right political party established in Thessaloniki, Greece, in 1927.

Registered as a mutual aid society, the EEE was founded by Asia Minor refugee businesspeopl ...

) party in 1927 to press for the removal of the Jews from the city, whom they saw as economic competitors. However, the EEE never became a major party, though its members did collaborate with the Germans in World War II, serving in the Security Battalions

The Security Battalions (, derisively known as ''Germanotsoliades'' (Γερμανοτσολιάδες, meaning "German tsoliás") or ''Tagmatasfalites'' (Ταγματασφαλίτες)) were Greek collaborationist paramilitary groups, formed d ...

.

The heterogeneous nature of the groups under the nation-state of Greece and Turkey is not reflected in the establishment of criteria formed in the Lausanne negotiations. This is evident in the first article of the Convention which states: "As from 1st May, 1923, there shall take place a compulsory exchange of Turkish nationals of the Greek Orthodox religion established in Turkish territory, and of Greek nationals of the Moslem religion established in Greek territory." The agreement defined the groups subject to exchange as Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

and Greek Orthodox

Greek Orthodox Church (, , ) is a term that can refer to any one of three classes of Christian Churches, each associated in some way with Greek Christianity, Levantine Arabic-speaking Christians or more broadly the rite used in the Eastern Rom ...

. This classification follows the lines drawn by the millet system

In the Ottoman Empire, a ''millet'' (; ) was an independent court of law pertaining to "personal law" under which a confessional community (a group abiding by the laws of Muslim sharia, Christian canon law, or Jewish halakha) was allowed to rule ...

of the Ottoman Empire. In the absence of rigid national definitions, there was no readily available criteria to yield to an official ordering of identities after centuries long coexistence in a non-national order.

Displacements

TheTreaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres () was a 1920 treaty signed between some of the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire, but not ratified. The treaty would have required the cession of large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, ...

imposed harsh terms upon Turkey and placed most of Anatolia under de facto Allied and Greek control. Sultan Mehmet VI

Mehmed VI Vahideddin ( ''Meḥmed-i sâdis'' or ''Vaḥîdü'd-Dîn''; or /; 14 January 1861 – 16 May 1926), also known as ''Şahbaba'' () among the Osmanoğlu family, was the last sultan of the Ottoman Empire and the penultimate Ottoman cal ...

's acceptance of the treaty angered Turkish nationalists

Turkish nationalism () is nationalism among the people of Turkey and individuals whose national identity is Turkish. Turkish nationalism consists of political and social movements and sentiments prompted by a love for Turkish culture, Turkish ...

, who established a rival government at Ankara and reorganized Turkish forces with the aim of blocking the implementation of the treaty, waging the Turkish War of Independence

, strength1 = May 1919: 35,000November 1920: 86,000Turkish General Staff, ''Türk İstiklal Harbinde Batı Cephesi'', Edition II, Part 2, Ankara 1999, p. 225August 1922: 271,000Celâl Erikan, Rıdvan Akın: ''Kurtuluş Savaşı tarih ...

. By the fall of 1922, the Ankara Government had secured most of Turkey's contemporary borders and replaced the Ottoman Sultanate as the dominant governing entity in Anatolia. Following these events, a peace conference was convened at Lausanne

Lausanne ( , ; ; ) is the capital and largest List of towns in Switzerland, city of the Swiss French-speaking Cantons of Switzerland, canton of Vaud, in Switzerland. It is a hilly city situated on the shores of Lake Geneva, about halfway bet ...

, Switzerland, in order to draft a new treaty to replace the Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres () was a 1920 treaty signed between some of the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire, but not ratified. The treaty would have required the cession of large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, ...

. Invitations to participate in the conference were extended to both the Ankara Government and the Istanbul-based Ottoman Government

The Ottoman Empire developed over the years as a despotism with the Sultan as the supreme ruler of a centralized government that had an effective control of its provinces, officials and inhabitants. Wealth and rank could be inherited but were ...

, but the abolition of the Sultanate by the Ankara Government on 1 November 1922 and the subsequent departure of Mehmet VI from Turkey left the Ankara Government as the sole governing entity in Anatolia.

The Ankara Government, led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, moved swiftly to implement its nationalist programme, which did not allow for the presence of significant non-Turkish minorities in Western Anatolia. In one of his first diplomatic acts as the sole governing representative of Turkey, Atatürk negotiated and signed the "Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations

The Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations (, ), also known as the Lausanne Convention, was an agreement between the Greece, Greek and Turkey, Turkish governments signed by their representatives in Lausanne on 30 Janua ...

" on 30 January 1923 with Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos (, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Cretan State, Cretan Greeks, Greek statesman and prominent leader of the Greek national liberation movement. As the leader of the Liberal Party (Greece), Liberal Party, Venizelos ser ...

and the government of Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

. The convention had a retroactive effect for all the population exchanges that took place since the declaration of the First Balkan War

The First Balkan War lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and involved actions of the Balkan League (the Kingdoms of Kingdom of Bulgaria, Bulgaria, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Greece, Greece and Kingdom of Montenegro, Montenegro) agai ...

on 18 October 1912 (article 3).

However, by the time the agreement was to take effect on 1 May 1923, most of the pre-war Greek population of Aegean Turkey had already fled. The exchange involved the remaining Greeks of central Anatolia (both Greek- and Turkish-speaking), Pontus

Pontus or Pontos may refer to:

* Short Latin name for the Pontus Euxinus, the Greek name for the Black Sea (aka the Euxine sea)

* Pontus (mythology), a sea god in Greek mythology

* Pontus (region), on the southern coast of the Black Sea, in modern ...

and the Caucasus (Kars region). Thus, of the 1,200,000 only about 189,916 still remained in Turkey by that time.

In Greece, the population exchange was considered part of the events called the ''

In Greece, the population exchange was considered part of the events called the ''Asia Minor Catastrophe

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

'' (). Significant refugee displacement and population movements had already occurred following the Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars were two conflicts that took place in the Balkans, Balkan states in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan states of Kingdom of Greece (Glücksburg), Greece, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Montenegro, M ...

, World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, and the Turkish War of Independence

, strength1 = May 1919: 35,000November 1920: 86,000Turkish General Staff, ''Türk İstiklal Harbinde Batı Cephesi'', Edition II, Part 2, Ankara 1999, p. 225August 1922: 271,000Celâl Erikan, Rıdvan Akın: ''Kurtuluş Savaşı tarih ...

. The convention affected the populations as follows: almost all Greek Orthodox Christians (Greek- or Turkish-speaking) of Asia Minor including the Greek Orthodox

Greek Orthodox Church (, , ) is a term that can refer to any one of three classes of Christian Churches, each associated in some way with Greek Christianity, Levantine Arabic-speaking Christians or more broadly the rite used in the Eastern Rom ...

populations from middle Anatolia (Cappadocian Greeks

The Cappadocian Greeks (; ), or simply Cappadocians, are an ethnic Greek community native to the geographical region of Cappadocia in central-eastern Anatolia; roughly the Nevşehir and Kayseri provinces and their surroundings in modern-day Turk ...

), the Ionia region (e.g. Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; , or ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, Turkey. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna ...

, Aivali), the Pontus region (e.g. Trabzon

Trabzon, historically known as Trebizond, is a city on the Black Sea coast of northeastern Turkey and the capital of Trabzon Province. The city was founded in 756 BC as "Trapezous" by colonists from Miletus. It was added into the Achaemenid E ...

, Samsun

Samsun is a List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, city on the north coast of Turkey and a major Black Sea port. The urban area recorded a population of 738,692 in 2022. The city is the capital of Samsun Province which has a population of ...

), the former Russian Caucasus province of Kars ( Kars Oblast), Prusa (Bursa), the Bithynia

Bithynia (; ) was an ancient region, kingdom and Roman province in the northwest of Asia Minor (present-day Turkey), adjoining the Sea of Marmara, the Bosporus, and the Black Sea. It bordered Mysia to the southwest, Paphlagonia to the northeast a ...

region (e.g., Nicomedia

Nicomedia (; , ''Nikomedeia''; modern İzmit) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek city located in what is now Turkey. In 286, Nicomedia became the eastern and most senior capital city of the Roman Empire (chosen by the emperor Diocletian who rul ...

(İzmit

İzmit () is a municipality and the capital Districts of Turkey, district of Kocaeli Province, Turkey. Its area is 480 km2, and its population is 376,056 (2022). The capital of Kocaeli Province, it is located at the Gulf of İzmit in the Sea ...

), Chalcedon

Chalcedon (; ; sometimes transliterated as ) was an ancient maritime town of Bithynia, in Asia Minor, Turkey. It was located almost directly opposite Byzantium, south of Scutari (modern Üsküdar) and it is now a district of the city of Ist ...

(Kadıköy

Kadıköy () is a municipality and Districts of Turkey, district on the Asian side of Istanbul Province, Istanbul Province, Turkey. Its area is 25 km2, and its population is 467,919 (2023). It is a large and populous area in the Asian si ...

), East Thrace

East Thrace or Eastern Thrace, also known as Turkish Thrace or European Turkey, is the part of Turkey that is geographically in Southeast Europe. Turkish Thrace accounts for 3.03% of Turkey's land area and 15% of its population. The largest c ...

, and other regions were either expelled or formally denaturalized from Turkish territory.

On the other hand, the Muslim population in Greece not having been affected by the recent Greek–Turkish conflict was almost intact. Thus c. 354,647 Muslims moved to Turkey after the agreement. Those Muslims were predominantly Turkish, but a large percentage belonged to Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

, Roma

Roma or ROMA may refer to:

People, characters, figures, names

* Roma or Romani people, an ethnic group living mostly in Europe and the Americas.

* Roma called Roy, ancient Egyptian High Priest of Amun

* Roma (footballer, born 1979), born ''Paul ...

, Pomak

Pomaks (; Macedonian: Помаци ; ) are Bulgarian-speaking Muslims inhabiting Bulgaria, northwestern Turkey, and northeastern Greece. The strong ethno-confessional minority in Bulgaria is recognized officially as Bulgarian Muslims by th ...

, Torbeši

The Torbeši () are a Macedonian language, Macedonian-speaking Islam, Muslim ethnoreligious group in North Macedonia and Albania. The Torbeši are also referred to as Macedonian Muslims () or Muslim Macedonians. They have been culturally distin ...

, Cham Albanian

Cham Albanians or Chams (; , ), are a sub-group of Albanians who originally resided in the western part of the region of Epirus in southwestern Albania and northwestern Greece, an area known among Albanians as Chameria. The Chams have their ow ...

, Megleno-Romanian, and Dönmeh