Gleiwitz on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Gliwice (; , ) is a

After the dissolution of the

After the dissolution of the

After the end of

After the end of  The Gleiwitz incident was a false-flag attack on a radio station in Gleiwitz on 31 August 1939, staged by the German secret police, which served as a pretext, devised by

The Gleiwitz incident was a false-flag attack on a radio station in Gleiwitz on 31 August 1939, staged by the German secret police, which served as a pretext, devised by

Gliwice is a major applied science hub for the

Gliwice is a major applied science hub for the

Other notable clubs:

* Gliwice Cricket Club

* K.S. Kodokan Gliwice – martial arts team and club

* Gliwice LIONS – American Football team

Other notable clubs:

* Gliwice Cricket Club

* K.S. Kodokan Gliwice – martial arts team and club

* Gliwice LIONS – American Football team

The city's President (i.e. Mayor) is Adam Neumann. He succeeded Zygmunt Frankiewicz who was mayor for 26 years (1993–2019) before being elected as a Polish Senator.

Gliwice has 21 city districts, each of them with its own ''Rada Osiedlowa''. They include, in alphabetical order: Bojków, Brzezinka, Czechowice, Kopernik, Ligota Zabrska, Łabędy, Obrońców Pokoju, Ostropa, Politechnika, Sikornik, Sośnica, Stare Gliwice, Szobiszowice, Śródmieście, Żwirki I Wigury, Trynek, Wilcze Gardło, Wojska Polskiego, Wójtowa Wieś, Zatorze, Żerniki.

The city's President (i.e. Mayor) is Adam Neumann. He succeeded Zygmunt Frankiewicz who was mayor for 26 years (1993–2019) before being elected as a Polish Senator.

Gliwice has 21 city districts, each of them with its own ''Rada Osiedlowa''. They include, in alphabetical order: Bojków, Brzezinka, Czechowice, Kopernik, Ligota Zabrska, Łabędy, Obrońców Pokoju, Ostropa, Politechnika, Sikornik, Sośnica, Stare Gliwice, Szobiszowice, Śródmieście, Żwirki I Wigury, Trynek, Wilcze Gardło, Wojska Polskiego, Wójtowa Wieś, Zatorze, Żerniki.

Um.gliwice.pl

Jewish Community in Gliwice

on Virtual Shtetl

Polsl.pl

Gliwice.pl

Gliwice.com

Gliwice.zobacz.slask.pl

Forumgliwice.com

Gliwice.info.pl

Aegee-gliwice.org

, Travel Guide

city

A city is a human settlement of a substantial size. The term "city" has different meanings around the world and in some places the settlement can be very small. Even where the term is limited to larger settlements, there is no universally agree ...

in Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( ; ; ; ; Silesian German: ; ) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, located today mostly in Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic. The area is predominantly known for its heav ...

, in southern Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

. The city is located in the Silesian Highlands

Silesian Upland or Silesian Highland () is a highland located in Silesia and Lesser Poland, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Ca ...

, on the Kłodnica river (a tributary of the Oder

The Oder ( ; Czech and ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and its largest tributary the Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows through wes ...

). It lies approximately 25 km west from Katowice

Katowice (, ) is the capital city of the Silesian Voivodeship in southern Poland and the central city of the Katowice urban area. As of 2021, Katowice has an official population of 286,960, and a resident population estimate of around 315,000. K ...

, the regional capital of the Silesian Voivodeship

Silesian Voivodeship ( ) is an administrative province in southern Poland. With over 4.2 million residents and an area of 12,300 square kilometers, it is the second-most populous, and the most-densely populated and most-urbanized region of Poland ...

.

Gliwice is the westernmost city of the Metropolis GZM

The Metropolis GZM (, formally in Polish (Upper Silesian-Dąbrowa Basin Metropolis)) is a metropolitan association () composed of 41 contiguous gminas, with a total population of over 2 million, covering most of the Katowice metropolitan area i ...

, a conurbation of 2.0 million people, and is the third-largest city of this area, with 175,102 permanent residents as of 2021. It also lies within the larger Katowice-Ostrava metropolitan area

The Katowice-Ostrava metropolitan areaBrookings Institutionbr>Redefining global cities: The seven types of global metro economies(2016), p. 16. European Spatial Planning Observation Network (ESPON"''Metroborder: Cross-border Polycentric Metropol ...

which has a population of about 5.3 million people and spans across most of eastern Upper Silesia, western Lesser Poland

Lesser Poland, often known by its Polish name ''Małopolska'' (; ), is a historical region situated in southern and south-eastern Poland. Its capital and largest city is Kraków. Throughout centuries, Lesser Poland developed a separate cult ...

and the Moravian-Silesian Region

The Moravian-Silesian Region () is one of the 14 administrative regions of the Czech Republic. Before May 2001, it was called the Ostrava Region (). The region is located in the north-eastern part of its historical region of Moravia and in most ...

in the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, also known as Czechia, and historically known as Bohemia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. The country is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the south ...

. Gliwice is bordered by three other cities and towns of the metropolitan area: Zabrze

Zabrze (; German: 1915–1945: , full form: , , ) is an industrial city put under direct government rule in Silesia in southern Poland, near Katowice. It lies in the western part of the Metropolis GZM, a metropolis with a population of around 2 m ...

, Knurów

Knurów (; ) is a city near Katowice in Silesia, southern Poland. Knurów is an outer city of the Metropolis GZM, a metropolis with a population of two million.

Knurów is located in the Silesian Highlands, on the Bierawka River, a tributary of t ...

and Pyskowice

Pyskowice () is a city in Silesia in southern Poland, near Katowice. Outer city of the Metropolis GZM – metropolis with a population of 2 million. Located in the Silesian Highlands.

It is situated in the Silesian Voivodeship since its formati ...

. It is one of the major college town

A college town or university town is a town or city whose character is dominated by a college or university and their associated culture, often characterised by the student population making up 20 percent of the population of the community, bu ...

s in Poland, thanks to the Silesian University of Technology

The Silesian University of Technology (Polish language, Polish name: Politechnika Śląska; ) is a university located in the Polish province of Silesia, with most of its facilities in the city of Gliwice. It was founded in 1945 by Polish profes ...

, which was founded in 1945 by academics of Lwów University of Technology

Lviv Polytechnic National University () is a public university in Lviv, Ukraine, founded in 1816. According to the Times Higher Education, as of 2024, it ranks first as a technical institution of higher education and second among all instit ...

. Over 20,000 people study in Gliwice. Gliwice is an important industrial center of Poland. Following an economic transformation in the 1990s, Gliwice shifted from steelworks

A steel mill or steelworks is an industrial plant for the manufacture of steel. It may be an integrated steel works carrying out all steps of steelmaking from smelting iron ore to rolled product, but may also be a plant where steel semi-fini ...

and coal mining

Coal mining is the process of resource extraction, extracting coal from the ground or from a mine. Coal is valued for its Energy value of coal, energy content and since the 1880s has been widely used to Electricity generation, generate electr ...

to automotive and machine industry

The machine industry or machinery industry is a subsector of the industry, that produces and maintains machines for consumers, the industry, and most other companies in the economy.

This machine industry traditionally belongs to the heavy indust ...

.

Founded in the 13th century, Gliwice is one of the oldest settlements in Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( ; ; ; ; Silesian German: ; ) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, located today mostly in Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic. The area is predominantly known for its heav ...

, with a preserved Old Town core. Gliwice's most historical structures include St Bartholomew's Church (15th century), Gliwice Castle and city walls (14th century), Armenian Church (originally a hospital, 15th century) and All Saints Old Town Church (15th century). Gliwice is also known for its Radio Tower

Radio masts and towers are typically tall structures designed to support antennas for telecommunications and broadcasting, including television. There are two main types: guyed and self-supporting structures. They are among the tallest human-m ...

, where the Gleiwitz incident took place shortly before the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

and which is thought to be the world's tallest wooden construction, as well as Weichmann Textile House, one of the first buildings designed by world-renowned architect Erich Mendelsohn

Erich Mendelsohn (); 21 March 1887 – 15 September 1953) was a German-British architect, known for his expressionist architecture in the 1920s, as well as for developing a dynamic functionalism in his projects for department stores and cinem ...

. Gliwice hosted the Junior Eurovision Song Contest 2019 which took place on 24 November 2019.

Etymology

The name of the city is derived from the Slavic root or , suggesting terrain characterized byloam

Loam (in geology and soil science) is soil composed mostly of sand (particle size > ), silt (particle size > ), and a smaller amount of clay (particle size < ). By weight, its mineral composition is about 40–40–20% concentration of sand–si ...

or wetland

A wetland is a distinct semi-aquatic ecosystem whose groundcovers are flooded or saturated in water, either permanently, for years or decades, or only seasonally. Flooding results in oxygen-poor ( anoxic) processes taking place, especially ...

.

History

Early history

Gliwice was first mentioned as a town in 1276, however, it was grantedtown rights

Town privileges or borough rights were important features of European towns during most of the second millennium. The city law customary in Central Europe probably dates back to Italian models, which in turn were oriented towards the tradition ...

earlier by Duke Władysław Opolski

Vladislaus I of Opole () ( – 27 August/13 September 1281/2) was a Duke of Kalisz during 1234–1244, Duke of Wieluń from 1234 to 1249 and Duke of Opole–Racibórz from 1246 until his death.

He was the second son of Casimir I of Opole b ...

of the Piast dynasty

The House of Piast was the first historical ruling dynasty of Poland. The first documented List of Polish monarchs, Polish monarch was Duke Mieszko I of Poland, Mieszko I (–992). The Poland during the Piast dynasty, Piasts' royal rule in Pol ...

. It was located on a trade route

A trade route is a logistical network identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo. The term can also be used to refer to trade over land or water. Allowing goods to reach distant markets, a singl ...

connecting Kraków

, officially the Royal Capital City of Kraków, is the List of cities and towns in Poland, second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city has a population of 804,237 ...

and Wrocław

Wrocław is a city in southwestern Poland, and the capital of the Lower Silesian Voivodeship. It is the largest city and historical capital of the region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the Oder River in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Eu ...

and was part of various Piast

The House of Piast was the first historical ruling dynasty of Poland. The first documented Polish monarch was Duke Mieszko I (–992). The Piasts' royal rule in Poland ended in 1370 with the death of King Casimir III the Great.

Branches of ...

-ruled duchies of fragmented Poland: Opole

Opole (; ; ; ) is a city located in southern Poland on the Oder River and the historical capital of Upper Silesia. With a population of approximately 127,387 as of the 2021 census, it is the capital of Opole Voivodeship (province) and the seat of ...

until 1281, Bytom

Bytom (Polish pronunciation: ; Silesian language, Silesian: ''Bytōm, Bytōń'', ) is a city in Upper Silesia, in southern Poland. Located in the Silesian Voivodeship, the city is 7 km northwest of Katowice, the regional capital.

It is one ...

until 1322, from 1322 to 1342 Gliwice was a capital of an eponymous duchy, afterwards again part of the Duchy of Bytom until 1354, later it was also ruled by other regional Polish Piast dukes until 1532, although in 1335 it fell under the suzerainty of the Bohemian Crown

The Lands of the Bohemian Crown were the states in Central Europe during the medieval and early modern periods with feudal obligations to the Bohemian kings. The crown lands primarily consisted of the Kingdom of Bohemia, an electorate of the Hol ...

, passing with that crown under suzerainty of the Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

n Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

s in 1526.

According to 14th-century writers, the town seemed defensive in character, when under rule of Siemowit of Bytom. In the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

the city prospered mainly due to trade and crafts, especially brewing

Brewing is the production of beer by steeping a starch source (commonly cereal grains, the most popular of which is barley) in water and #Fermenting, fermenting the resulting sweet liquid with Yeast#Beer, yeast. It may be done in a brewery ...

.

On 17 April 1433, Gliwice was captured by the Duke

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of Royal family, royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and above sovereign princes. As royalty or nobi ...

Bolko V, who joined the Hussites

upright=1.2, Battle between Hussites (left) and Crusades#Campaigns against heretics and schismatics, Catholic crusaders in the 15th century

upright=1.2, The Lands of the Bohemian Crown during the Hussite Wars. The movement began during the Prag ...

after they captured Prudnik

Prudnik (, , , ) is a town in southern Poland, located in the southern part of Opole Voivodeship near the border with the Czech Republic. It is the administrative seat of Prudnik County and Gmina Prudnik. Its population numbers 21,368 inhabitant ...

.

Early Modern Age

Duchy of Opole and Racibórz

The Duchy of Opole and Racibórz (, ) was one of the numerous Duchies of Silesia ruled by the Silesian branch of the royal Polish Piast dynasty. It was formed in 1202 from the union of the Upper Silesian duchies of Opole and the Racibórz, in a ra ...

in 1532, it was incorporated as Gleiwitz into the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy, also known as Habsburg Empire, or Habsburg Realm (), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities (composite monarchy) that were ruled by the House of Habsburg. From the 18th century it is ...

. Because of the vast expenses incurred by the Habsburg monarchy during their 16th century wars against the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, Gleiwitz was lease

A lease is a contractual arrangement calling for the user (referred to as the ''lessee'') to pay the owner (referred to as the ''lessor'') for the use of an asset. Property, buildings and vehicles are common assets that are leased. Industrial ...

d to Friedrich Zettritz for the amount of 14,000 thaler

A thaler or taler ( ; , previously spelled ) is one of the large silver coins minted in the states and territories of the Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburg monarchy during the Early Modern period. A ''thaler'' size silver coin has a diameter o ...

s. Although the original lease was for a duration of 18 years, it was renewed in 1580 for 10 years and in 1589 for an additional 18 years. Around 1612, the Reformed Franciscans came from Kraków

, officially the Royal Capital City of Kraków, is the List of cities and towns in Poland, second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city has a population of 804,237 ...

, and then their monastery and Holy Cross Church were built. The city was besieged or captured by various armies during the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine ...

. In 1645 along with the Duchy of Opole and Racibórz it returned to Poland under the House of Vasa

The House of Vasa or Wasa was a Dynasty, royal house that was founded in 1523 in Sweden. Its members ruled the Kingdom of Sweden from 1523 to 1654 and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth from 1587 to 1668. Its agnatic line became extinct with t ...

, and in 1666 it fell to Austria again. In 1683, Polish King John III Sobieski

John III Sobieski ( (); (); () 17 August 1629 – 17 June 1696) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1674 until his death in 1696.

Born into Polish nobility, Sobieski was educated at the Jagiellonian University and toured Eur ...

stopped in the city before the Battle of Vienna

The Battle of Vienna took place at Kahlenberg Mountain near Vienna on 1683 after the city had been besieged by the Ottoman Empire for two months. The battle was fought by the Holy Roman Empire (led by the Habsburg monarchy) and the Polish–Li ...

. In the 17th and 18th century, the city's economy switched from trading and brewing beer to clothmaking, which collapsed after the 18th-century Silesian Wars

The Silesian Wars () were three wars fought in the mid-18th century between Kingdom of Prussia, Prussia (under King Frederick the Great) and Habsburg monarchy, Habsburg Austria (under Empress Maria Theresa) for control of the Central European ...

.

During the mid 18th century Silesian Wars

The Silesian Wars () were three wars fought in the mid-18th century between Kingdom of Prussia, Prussia (under King Frederick the Great) and Habsburg monarchy, Habsburg Austria (under Empress Maria Theresa) for control of the Central European ...

, Gleiwitz was taken from the Habsburg monarchy by the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (, ) was a German state that existed from 1701 to 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Rev. ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1946. It played a signif ...

along with the majority of Silesia. After the end of the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

, Gleiwitz was administered in the Prussian district of Tost-Gleiwitz within the Province of Silesia

The Province of Silesia (; ; ) was a province of Prussia from 1815 to 1919. The Silesia region was part of the Prussian realm since 1742 and established as an official province in 1815, then became part of the German Empire in 1871. In 1919, as ...

in 1816. The city was incorporated with Prussia into the German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

in 1871 during the unification of Germany

The unification of Germany (, ) was a process of building the first nation-state for Germans with federalism, federal features based on the concept of Lesser Germany (one without Habsburgs' multi-ethnic Austria or its German-speaking part). I ...

. In 1897, Gleiwitz became its own Stadtkreis, or urban district.

Industrialization

The first coke-firedblast furnace

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being supplied above atmospheric pressure.

In a ...

on the European continent was constructed in Gleiwitz in 1796 under the direction of John Baildon. Gleiwitz began to develop into a major city through industrialization

Industrialisation (British English, UK) American and British English spelling differences, or industrialization (American English, US) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an i ...

during the 19th century. The town's ironworks

An ironworks or iron works is an industrial plant where iron is smelted and where heavy iron and steel products are made. The term is both singular and plural, i.e. the singular of ''ironworks'' is ''ironworks''.

Ironworks succeeded bloome ...

fostered the growth of other industrial fields in the area. The city's population in 1875 was 14,156. However, during the late 19th century Gleiwitz had: 14 distilleries

Distillation, also classical distillation, is the process of separating the component substances of a liquid mixture of two or more chemically discrete substances; the separation process is realized by way of the selective boiling of the mixt ...

, 2 breweries

A brewery or brewing company is a business that makes and sells beer. The place at which beer is commercially made is either called a brewery or a beerhouse, where distinct sets of brewing equipment are called plant. The commercial brewing of be ...

, 5 mills, 7 brick

A brick is a type of construction material used to build walls, pavements and other elements in masonry construction. Properly, the term ''brick'' denotes a unit primarily composed of clay. But is now also used informally to denote building un ...

factories

A factory, manufacturing plant or production plant is an industrial facility, often a complex consisting of several buildings filled with machinery, where workers manufacture items or operate machines which process each item into another. Th ...

, 3 sawmill

A sawmill (saw mill, saw-mill) or lumber mill is a facility where logging, logs are cut into lumber. Modern sawmills use a motorized saw to cut logs lengthwise to make long pieces, and crosswise to length depending on standard or custom sizes ...

s, a shingle factory, 8 chalk

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor. Ch ...

factories and 2 glassworks

Glass production involves two main methods – the float glass process that produces sheet glass, and glassblowing that produces bottles and other containers. It has been done in a variety of ways during the history of glass.

Glass container p ...

.

Other features of the 19th-century era industrialized Gleiwitz were a gasworks

A gasworks or gas house is an industrial plant for the production of flammable gas. Many of these have been made redundant in the developed world by the use of natural gas, though they are still used for storage space.

Early gasworks

Coal ...

, a furnace factory, a beer bottling company

A bottling company is a commercial enterprise whose output is the bottling of beverages for distribution.

Many bottling companies are franchisees of corporations such as Coca-Cola and PepsiCo who distribute the beverage in a specific geogra ...

, and a plant for asphalt and paste. Economically, Gleiwitz opened several bank

A bank is a financial institution that accepts Deposit account, deposits from the public and creates a demand deposit while simultaneously making loans. Lending activities can be directly performed by the bank or indirectly through capital m ...

s, savings and loan association

A savings and loan association (S&L), or thrift institution, is a financial institution that specializes in accepting savings deposits and making mortgage and other loans. While the terms "S&L" and "thrift" are mainly used in the United States, ...

s, and bond centers. Its tram

A tram (also known as a streetcar or trolley in Canada and the United States) is an urban rail transit in which Rolling stock, vehicles, whether individual railcars or multiple-unit trains, run on tramway tracks on urban public streets; some ...

system was completed in 1892, while its theater

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors to present experiences of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The performers may communi ...

was opened in 1899; until World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Gleiwitz's theatre featured actors from throughout Europe and was one of the most famous theatres in the whole of Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

. Despite Germanisation

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, people, and culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nationalism went hand in hand. In l ...

policies, the Poles

Pole or poles may refer to:

People

*Poles (people), another term for Polish people, from the country of Poland

* Pole (surname), including a list of people with the name

* Pole (musician) (Stefan Betke, born 1967), German electronic music artist

...

established various Polish organizations, including the "Sokół" Polish Gymnastic Society, and published local Polish newspapers.

20th century

According to the1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

Events January

* January 1 – A decade after federation, the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory are added to the Commonwealth of Australia.

* January 3

** 1911 Kebin earthquake: An earthquake of 7.7 Mom ...

, Gleiwitz's population in 1905 was 61,324. By 1911, it had two Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

and four Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

churches, a synagogue

A synagogue, also called a shul or a temple, is a place of worship for Jews and Samaritans. It is a place for prayer (the main sanctuary and sometimes smaller chapels) where Jews attend religious services or special ceremonies such as wed ...

, a mining school, a convent

A convent is an enclosed community of monks, nuns, friars or religious sisters. Alternatively, ''convent'' means the building used by the community.

The term is particularly used in the Catholic Church, Lutheran churches, and the Anglican ...

, a hospital

A hospital is a healthcare institution providing patient treatment with specialized Medical Science, health science and auxiliary healthcare staff and medical equipment. The best-known type of hospital is the general hospital, which typically ...

, two orphanage

An orphanage is a residential institution, total institution or group home, devoted to the care of orphans and children who, for various reasons, cannot be cared by their biological families. The parents may be deceased, absent, or abusi ...

s, and a barracks

Barracks are buildings used to accommodate military personnel and quasi-military personnel such as police. The English word originates from the 17th century via French and Italian from an old Spanish word 'soldier's tent', but today barracks ar ...

. Gleiwitz was the center of the mining

Mining is the Resource extraction, extraction of valuable geological materials and minerals from the surface of the Earth. Mining is required to obtain most materials that cannot be grown through agriculture, agricultural processes, or feasib ...

industry of Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( ; ; ; ; Silesian German: ; ) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, located today mostly in Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic. The area is predominantly known for its heav ...

. It possessed a royal foundry

A foundry is a factory that produces metal castings. Metals are cast into shapes by melting them into a liquid, pouring the metal into a mold, and removing the mold material after the metal has solidified as it cools. The most common metals pr ...

, with which were connected machine factories and boiler works.

After the end of

After the end of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, clashes between Poles

Pole or poles may refer to:

People

*Poles (people), another term for Polish people, from the country of Poland

* Pole (surname), including a list of people with the name

* Pole (musician) (Stefan Betke, born 1967), German electronic music artist

...

and Germans

Germans (, ) are the natives or inhabitants of Germany, or sometimes more broadly any people who are of German descent or native speakers of the German language. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, constitution of Germany, imple ...

occurred during the Polish insurrections in Silesia. Some ethnically Polish inhabitants of Upper Silesia wanted to incorporate the city into the Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 7 October 1918 and 6 October 1939. The state was established in the final stage of World War I ...

, which just regained independence. On 1 May 1919, a Polish rally was held in Gliwice. Seeking a peaceful solution to the conflict, the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

held a plebiscite

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a direct vote by the electorate (rather than their representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either binding (resulting in the adoption of a new policy) or adv ...

on 20 March 1921 to determine which country the city should belong to. In Gleiwitz, 32,029 votes (78.7% of given votes) were for remaining in Germany, Poland received 8,558 (21.0%) votes, and 113 (0.3%) votes were declared invalid. The total voter turnout was listed as 97.0%. This prompted another insurrection by Poles. The League of Nations determined that three Silesian cities: Gleiwitz (Gliwice), Hindenburg (Zabrze) and Beuthen (Bytom) would remain in Germany, and the eastern part of Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( ; ; ; ; Silesian German: ; ) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, located today mostly in Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic. The area is predominantly known for its heav ...

with its main city of Katowice (Kattowitz) would join restored Poland. After delimiting the border in Upper Silesia in 1921, Gliwice found itself in Germany, but near the border with Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

– nearby Knurów

Knurów (; ) is a city near Katowice in Silesia, southern Poland. Knurów is an outer city of the Metropolis GZM, a metropolis with a population of two million.

Knurów is located in the Silesian Highlands, on the Bierawka River, a tributary of t ...

was already in Poland.

During the interbellum

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

the city witnessed not only anti-Polish, but also anti-French

Anti-French sentiment (Francophobia or Gallophobia) is the fear of, discrimination against, prejudice of, or hatred towards France, the French people, French culture, the French government or the Francophonie (set of political entities that use Fr ...

incidents and violence by the Germans. In 1920, local Polish doctor and city councillor

A councillor, alternatively councilman, councilwoman, councilperson, or council member, is someone who sits on, votes in, or is a member of, a council. This is typically an elected representative of an electoral district in a municipal or re ...

, protested against the German refusal to treat French soldiers stationed in the city. In January 1922, he himself treated French soldiers shot in the city. On 9 April 1922, 17 Frenchmen died in an explosion during the liquidation of a German militia weapons warehouse in the present-day Sośnica district. Styczyński, who defended the rights of local Poles and protested against German acts of violence against Poles, was himself murdered by a German radical/militant on 18 April 1922. Nevertheless, various Polish organizations and enterprises still operated in the city in the interbellum, including a local branch of the Union of Poles in Germany

Union of Poles in Germany (, ) is an organisation of the Poland, Polish minority in Germany, founded in 1922. In 1924, the union initiated collaboration between other minorities, including Sorbs, Danish minority in Southern Schleswig, Danes, Fris ...

, Polish banks and a scout troop

A Scout troop is a term adopted into use with Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts and the Scout Movement to describe their basic units. The term troop echoes a group of mounted scouts in the military or an expedition and follows the terms cavalry, mounted i ...

.

On 9 June 1933, Gliwice was the site of the first conference of the Nazi anti-Polish organization Bund Deutscher Osten

The Bund Deutscher Osten (BDO; English: "Federation of the German East") was an anti-Polish German Nazi organisation founded on 26 May 1933. The organisation was supported by the Nazi Party. The BDO was a national socialist version of the German ...

in Upper Silesia. In a secret ''Sicherheitsdienst

' (, "Security Service"), full title ' ("Security Service of the ''Reichsführer-SS''"), or SD, was the intelligence agency of the Schutzstaffel, SS and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany. Established in 1931, the SD was the first Nazi intelligence ...

'' report from 1934, Gliwice was named one of the main centers of the Polish movement in western Upper Silesia. Polish activists were increasingly persecuted starting in 1937.

Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich ( , ; 7 March 1904 – 4 June 1942) was a German high-ranking SS and police official during the Nazi era and a principal architect of the Holocaust. He held the rank of SS-. Many historians regard Heydrich ...

under orders from Hitler, for Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

to invade Poland, and which marked the start of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Shortly after the outbreak of the war, on 4 September 1939, the ''Einsatzgruppe I

(, ; also 'task forces') were (SS) paramilitary death squads of Nazi Germany that were responsible for mass murder, primarily by shooting, during World War II (1939–1945) in German-occupied Europe. The had an integral role in the impl ...

'' entered the city to commit atrocities against Poles. After the invasion of Poland, the assets of local Polish banks were confiscated by Germany. The Germans formed a ''Kampfgruppe

In military history, the German term (pl. ; abbrev. KG, or KGr in usage during World War II, literally "fighting group" or " battlegroup") can refer to a combat formation of any kind, but most usually to that employed by the of Nazi Germa ...

'' unit in the city. It was also the cremation

Cremation is a method of Disposal of human corpses, final disposition of a corpse through Combustion, burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India, Nepal, and ...

site of many of around 750 Poles murdered in Katowice in September 1939.

In early 1940, the advanced shaped charge

A shaped charge, commonly also hollow charge if shaped with a cavity, is an explosive charge shaped to focus the effect of the explosive's energy. Different types of shaped charges are used for various purposes such as cutting and forming metal, ...

explosive developed for the attack on Fort Ében-Émael as part of the ''Blitzkrieg

''Blitzkrieg'(Lightning/Flash Warfare)'' is a word used to describe a combined arms surprise attack, using a rapid, overwhelming force concentration that may consist of armored and motorized or mechanized infantry formations, together with ...

'' attack on the Maginot Line

The Maginot Line (; ), named after the Minister of War (France), French Minister of War André Maginot, is a line of concrete fortifications, obstacles and weapon installations built by French Third Republic, France in the 1930s to deter invas ...

on May 10, 1940 were tested at places in Gleiwitz to ensure secrecy.

During the war, the Germans operated a ''Dulag'' transit camp for Polish prisoners of war, and a Nazi prison in the city, and established numerous forced labour

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, or violence, including death or other forms of ...

camps, including a '' Polenlager'' camp solely for Poles, a camp solely for Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

, a penal "education" camp, a subcamp of the prison in Strzelce Opolskie

Strzelce Opolskie () is a town in southern Poland with 17,900 inhabitants (2019), situated in the Opole Voivodeship. It is the capital of Strzelce County.

Etymology

The name of the town is of Polish origin and comes from the old Polish word ''s ...

, and six subcamps of the Stalag VIII-B/344 prisoner of war camp

A prisoner-of-war camp (often abbreviated as POW camp) is a site for the containment of enemy fighters captured as prisoners of war by a belligerent power in time of war.

There are significant differences among POW camps, internment camps, ...

. In October 1943, the Germans brought a large transport of Italian POWs to a forced labour camp in today's Łabędy district. From July 1944 to January 1945, Gliwice was the location of four subcamps of the Auschwitz concentration camp

Auschwitz, or Oświęcim, was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) d ...

. In the largest subcamp, whose prisoners were mainly Poles, Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

and Russians

Russians ( ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Eastern Europe. Their mother tongue is Russian language, Russian, the most spoken Slavic languages, Slavic language. The majority of Russians adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church ...

, nearly 100 either died of hunger, mistreatment and exhaustion or were murdered. During the evacuation of another subcamp, the Germans burned alive or shot 55 prisoners who were unable to walk. There are two mass graves of the victims of the early 1945 death march

A death march is a forced march of prisoners of war, other captives, or deportees in which individuals are left to die along the way. It is distinct from simple prisoner transport via foot march. Article 19 of the Geneva Convention requires tha ...

from Auschwitz in the city, both commemorated with monuments.

During the final stages of the war, 124 inhabitants committed suicide fearing the advancing Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

. On 24 January 1945, Gliwice was occupied by the Red Army. Soviet troops then murdered over 1,000 civilians, mostly women, children and elders. In February 1945, the Soviets carried out deportations of local men to Soviet mines. Under borders changes dictated by the Soviet Union at the Potsdam Conference, Gliwice fell inside Poland's new borders after Germany's defeat in the war. It was incorporated into Poland's Silesian Voivodeship

Silesian Voivodeship ( ) is an administrative province in southern Poland. With over 4.2 million residents and an area of 12,300 square kilometers, it is the second-most populous, and the most-densely populated and most-urbanized region of Poland ...

on 18 March 1945, after almost 300 years of being outside of Polish rule.

In 1956, Gliwice was the site of a manifestation of solidarity with the Hungarian Revolution of 1956

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 (23 October – 4 November 1956; ), also known as the Hungarian Uprising, was an attempted countrywide revolution against the government of the Hungarian People's Republic (1949–1989) and the policies caused by ...

, and local Poles raised funds and donated blood for the Hungarian insurgents (see also ''Hungary–Poland relations

Poland–Hungary relations are the foreign relations between Poland and Hungary. Relations between the two nations date back to the Middle Ages. The two Eastern European peoples have traditionally enjoyed a very close friendship, brotherhood and ...

'').

Demographics

Population development

The earliest population estimate of Gliwice from 1880, gives 1,159 people in 1750. The same source cites population to have been 2,990 in 1810, 6,415 in 1838, and 10,923 in 1861. A census from 1858 reported the following ethnic makeup: 7,060 -German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

, 3,566 - Polish, 11 - Moravian, 1 - Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus

*Czech (surnam ...

. Since the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

, Gliwice saw rapid economic growth which fuelled fast population increase. In 1890, Gliwice had 19,667 inhabitants, and this number has increased over twofold over the next 10 years to 52,362 in 1900. Gliwice gained its status of a large city (''Großstadt

A town is a type of a human settlement, generally larger than a village but smaller than a city.

The criteria for distinguishing a town vary globally, often depending on factors such as population size, economic character, administrative stat ...

'' in German) in 1927, when population reached 102,452 people.

In 1945, with the approaching Red Army, a significant number of residents were either evacuated or fled the city at their own discretion. Following the Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (), held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the postwar reorganization of Germany and Europe. The three sta ...

, Gliwice, along most of Silesia

Silesia (see names #Etymology, below) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at 8, ...

, was incorporated into communist Poland, and the remaining German population was expelled. Ethnic Poles, some of them themselves expelled from the Polish Kresy (which were incorporated into Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

), started to settle down in Gliwice.

As of December 31, 2016, Gliwice's population stood at 182,156 people, a decrease of 1,236 over the previous year.

Nationality, ethnicity and language

Historically, Gliwice was ethnically diverse, initially inhabited byPoles

Pole or poles may refer to:

People

*Poles (people), another term for Polish people, from the country of Poland

* Pole (surname), including a list of people with the name

* Pole (musician) (Stefan Betke, born 1967), German electronic music artist

...

, later it had a German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

majority as a result of German colonization

475px, Map of the year each country achieved List of sovereign states by date of formation, independence.

Colonization (British English: colonisation) is a process of establishing occupation of or control over foreign territories or peoples f ...

, with a significant autochthonous Polish minority. In the Upper Silesian Plebiscite in 1921, 78.9 percent of voters opted for Germany (however 15.1 percent of the vote in Gliwice was cast by non-residents, who are believed to overwhelmingly vote for Germany across the region). After Germany's defeat in World War II, the Germans either fled or were displaced to Allied-occupied Germany in accordance with the Potsdam Agreement

The Potsdam Agreement () was the agreement among three of the Allies of World War II: the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Soviet Union after the war ended in Europe that was signed on 1 August 1945 and published the following day. A ...

. Polish inhabitants remained in Gliwice, and were joined by Poles displaced from former eastern Poland annexed by the Soviet Union, including the city of Lwów

Lviv ( or ; ; ; see #Names and symbols, below for other names) is the largest city in western Ukraine, as well as the List of cities in Ukraine, fifth-largest city in Ukraine, with a population of It serves as the administrative centre of ...

(Lviv), Volhynia

Volhynia or Volynia ( ; see #Names and etymology, below) is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between southeastern Poland, southwestern Belarus, and northwestern Ukraine. The borders of the region are not clearly defined, but in ...

, Polesie, the Wilno

Vilnius ( , ) is the capital of and List of cities in Lithuania#Cities, largest city in Lithuania and the List of cities in the Baltic states by population, most-populous city in the Baltic states. The city's estimated January 2025 population w ...

region (Vilnius region) and the Grodno

Grodno, or Hrodna, is a city in western Belarus. It is one of the oldest cities in Belarus. The city is located on the Neman, Neman River, from Minsk, about from the Belarus–Poland border, border with Poland, and from the Belarus–Lithua ...

region. In addition, Poles from other regions of Poland, including the vicinity of Kielce

Kielce (; ) is a city in south-central Poland and the capital of the Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship. In 2021, it had 192,468 inhabitants. The city is in the middle of the Świętokrzyskie Mountains (Holy Cross Mountains), on the banks of the Silnic ...

, Rzeszów

Rzeszów ( , ) is the largest city in southeastern Poland. It is located on both sides of the Wisłok River in the heartland of the Sandomierz Basin. Rzeszów is the capital of the Subcarpathian Voivodeship and the county seat, seat of Rzeszów C ...

, Łódź

Łódź is a city in central Poland and a former industrial centre. It is the capital of Łódź Voivodeship, and is located south-west of Warsaw. Łódź has a population of 655,279, making it the country's List of cities and towns in Polan ...

or Poznań

Poznań ( ) is a city on the Warta, River Warta in west Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business center and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint John's ...

, as well as Poles from other countries, settled in Gliwice. Many of these new inhabitants were academics from the Lwów Polytechnic who created the Silesian University of Technology

The Silesian University of Technology (Polish language, Polish name: Politechnika Śląska; ) is a university located in the Polish province of Silesia, with most of its facilities in the city of Gliwice. It was founded in 1945 by Polish profes ...

.

According to the 2011 Polish Census, 93.7 percent of people in Gliwice claimed Polish nationality, with the biggest minorities being Silesians

Silesians (; Silesian German: ''Schläsinger'' ''or'' ''Schläsier''; ; ; ) is both an ethnic as well as a geographical term for the inhabitants of Silesia, a historical region in Central Europe divided by the current national boundaries o ...

(or both Poles and Silesians at the same time) at 9.7 percent (18,169 people) and Germans at 1.3 percent (2,525). 0.3 percent declared another nationality, and the nationality of 2.1 percent of people could not be established. These numbers do not sum up to 100 percent as responders were allowed to choose up to two nationalities. The most common languages used at home were Polish (97.7 percent), Silesian (2.3 percent), German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

(0.7 percent) and English (0.4 percent).

Religion

Except for a short period immediately afterReformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

, Gliwice has always had a Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

majority, with sizeable Protestant and Jewish minorities. According to the population estimate in 1861, 7,476 people (68.4 percent) were Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, 1,555 (14.2 percent) Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

, and 1,892 Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

(17.3 percent, highest share in city history).

Currently, as of 2011 census, 84.7 percent of inhabitants claim they belong to a religion. The majority – 82.73 percent – belongs to the Catholic Church. This is significantly lower than the Polish average, which is 89.6 and 88.3 percent, respectively. According to the Catholic Church in Poland

Polish members of the Catholic Church, like elsewhere in the world, are under the spiritual leadership of the Pope in Holy See, Rome. The Latin Church includes 41 dioceses. There are three eparchies of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church in th ...

, weekly mass attendance in the Diocese of Gliwice is at 36.7 percent of obliged, on par with Polish average. Other larger denominations include Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses is a Christian denomination that is an outgrowth of the Bible Student movement founded by Charles Taze Russell in the nineteenth century. The denomination is nontrinitarian, millenarian, and restorationist. Russell co-fou ...

(0.56 percent or 1,044 adherents) and Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

(0.37 percent or 701 adherents).

Gliwice is the seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Gliwice

The Diocese of Gliwice () is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic Church in Poland. Its episcopal see is located in the city of Gliwice. The Diocese of Gliwice is a suffragan diocese in the ecclesiastical province of ...

, which has 23 parish churches in the city. Gliwice is also the seat of one of the three Armenian Church parishes in Poland (the other being in Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

and Gdańsk

Gdańsk is a city on the Baltic Sea, Baltic coast of northern Poland, and the capital of the Pomeranian Voivodeship. With a population of 486,492, Data for territorial unit 2261000. it is Poland's sixth-largest city and principal seaport. Gdań ...

), which is subject to the Holy See

The Holy See (, ; ), also called the See of Rome, the Petrine See or the Apostolic See, is the central governing body of the Catholic Church and Vatican City. It encompasses the office of the pope as the Bishops in the Catholic Church, bishop ...

directly. Other denominations present in the city include a Greek Catholic Church Greek Catholic Church or Byzantine-Catholic Church may refer to:

* The Catholic Church in Greece

* The Eastern Catholic Churches that use the Byzantine Rite, also known as the Greek Rite:

** The Albanian Greek Catholic Church

** The Belarusian Gre ...

parish, an Evangelical Church of Augsburg Confession parish, a Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a Protestant Christianity, Christian Christian tradition, tradition whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's brother ...

parish, 9 Jehovah Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses is a Christian denomination that is an outgrowth of the Bible Student movement founded by Charles Taze Russell in the nineteenth century. The denomination is nontrinitarian, millenarian, and restorationist. Russell co-f ...

halls (including one offering English-language services), several evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes evangelism, or the preaching and spreading of th ...

churches, a Buddhist

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

temple and a Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

prayer house.

Jews in Gliwice

Gliwice's Jewish population reached its height in 1929 at approximately 2,200 people, but started to decline in the late 1930s, as theNazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

gained power in Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, of which Gliwice was then a part. In 1933, there were 1,803 Jews living in the city; this number had dropped by half (to 902) by 1939 due to emigration. Between 1933 and 1937, Jews living in Upper Silesia enjoyed somewhat less legal persecution compared to Jews in other parts of Germany, thanks to the Polish-German Treaty of Protection of Minorities' Rights in Upper Silesia. This regional exception was granted thanks to the Bernheim petition that Gliwice citizen Franz Bernheim filed against Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

with the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

. The New Synagogue was destroyed in 1938 during the Nazi November pogroms known as Kristallnacht

( ) or the Night of Broken Glass, also called the November pogrom(s) (, ), was a pogrom against Jews carried out by the Nazi Party's (SA) and (SS) paramilitary forces along with some participation from the Hitler Youth and German civilia ...

. During the Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

, Jews from Gliwice were transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau

Auschwitz, or Oświęcim, was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) d ...

in 1942 and 1943.

Only 25 Jews from Gliwice's pre-war Jewish population survived World War II in the city, all of them being in mixed marriages with gentiles. Immediately after the war, Gliwice became a congregation point for Jews who had survived the Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

, with the Jewish population standing at around a 1,000 people in 1945. Since then, the number of Jews in Gliwice has declined as survivors moved to larger cities or emigrated to Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

, the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, and other western countries. Currently, Gliwice's Jewish community is estimated at around 25 people and is part of the Katowice Jewish Religious Community.

Gliwice has one Jewish prayer house, where religious services are held every Sabbath

In Abrahamic religions, the Sabbath () or Shabbat (from Hebrew ) is a day set aside for rest and worship. According to the Book of Exodus, the Sabbath is a day of rest on the seventh day, Ten Commandments, commanded by God to be kept as a Holid ...

and on holidays. It is located in the house that the Jewish Religious Community elected in 1905.

Notable members of the Jewish community in Gliwice include:

* Wilhelm Freund (1806–1894), philologist and director of the Jewish school.

* Oscar Troplowitz

Oscar Troplowitz (18 January 1863 – 27 April 1918) was a German pharmacist and entrepreneur.

Troplowitz was born to a Jewish family in Gleiwitz. trained at Heidelberg University and in 1890 he purchased Beiersdorf AG, which at the time was a ...

(1863–1918), German pharmacist, owner of Beiersdorf AG and inventor of Nivea skin cream.

* Eugen Goldstein

Eugen Goldstein (; ; 5 September 1850 – 25 December 1930) was a German physicist. He was an early investigator of discharge tubes, and the discoverer of anode rays or canal rays, later identified as positive ions in the gas phase including th ...

(1850–1930), German physicist, discoverer of anode rays, sometimes credited for the discovery of the proton.

* Julian Kornhauser (b. 1946), Polish poet and father of current first lady Agata Kornhauser-Duda

Agata Kornhauser-Duda (born 2 April 1972) is First Lady of Poland since 2015 as the wife of president of Poland, Andrzej Duda.

Background and family

Kornhauser was born in Kraków, the child of Julian Kornhauser, a Polish people, Polish writer, ...

, born in Gliwice to a Jewish father and Polish Silesian mother from Chorzów

Chorzów ( ; ; ) is a city in the Silesia region of southern Poland, near Katowice. Chorzów is one of the central cities of the Metropolis GZM – a metropolis with a population of 2 million. It is located in the Silesian Highlands, on the Rawa ...

.

Sights and architecture

*Market Square (''Rynek'') with the Town Hall (''Ratusz''), Neptune Fountain and colourful historic townhouses, located in the Old Town *TheGliwice Radio Tower

The Gliwice Radio Tower is a transmission tower in the Szobiszowice district of Gliwice, Upper Silesia, Poland. Nazi Germany staged a false flag attack on the tower in 1939, which was used as a pretext for invading Poland, beginning World War I ...

of ''Radiostacja Gliwicka'' ("Radio Station Gliwice") in Szobiszowice is the only remaining radio tower of wood construction in the world, and with a height of 118 meters, is perhaps the tallest remaining construction made out of wood in the world. It is listed as a Historic Monument of Poland and now it is a branch of the local museum.

* Piast Castle dates back to the Middle Ages and hosts a branch of the local museum.

*Museum in Gliwice ('' Muzeum w Gliwicach''), a local museum

*Museum of Upper Silesian Jewry, a part of the local museum; located in the mortuary at the New Jewish Cemetery, which was designed by the Viennese Architect Max Fleischer

Max Fleischer (born Majer Fleischer ; July 19, 1883 – September 11, 1972) was an American animator and studio owner. Born in Kraków, in Austrian Poland, Fleischer immigrated to the United States where he became a pioneer in the development ...

* Sts. Peter and Paul Cathedral, the cathedral church of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Gliwice

The Diocese of Gliwice () is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic Church in Poland. Its episcopal see is located in the city of Gliwice. The Diocese of Gliwice is a suffragan diocese in the ecclesiastical province of ...

, and other historic churches

*Medieval fortified

A fortification (also called a fort, fortress, fastness, or stronghold) is a military construction designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Lat ...

Old Saint Bartholomew church

*Medieval town walls

*Baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

Holy Cross Church and Redemptorist

The Redemptorists, officially named the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer (), abbreviated CSsR, is a Catholic clerical religious congregation of pontifical right for men (priests and brothers). It was founded by Alphonsus Liguori at Scal ...

monastery from the 17th century (former Reformed Franciscan monastery)

*Piłsudski Square with a monument of pre-war Polish leader Józef Piłsudski

Józef Klemens Piłsudski (; 5 December 1867 – 12 May 1935) was a Polish statesman who served as the Chief of State (Poland), Chief of State (1918–1922) and first Marshal of Poland (from 1920). In the aftermath of World War I, he beca ...

*Chopin Park with a monument to the Polish composer Fryderyk Chopin

The Fryderyk is the annual award in Polish music. Its name refers to the original Polish spelling variant of Polish composer Frédéric Chopin's first name. Its status in the Polish public can be compared to the US Grammy and British BRIT Awar ...

and the Municipal Palm House

* Culture and Recreation Park in Gliwice

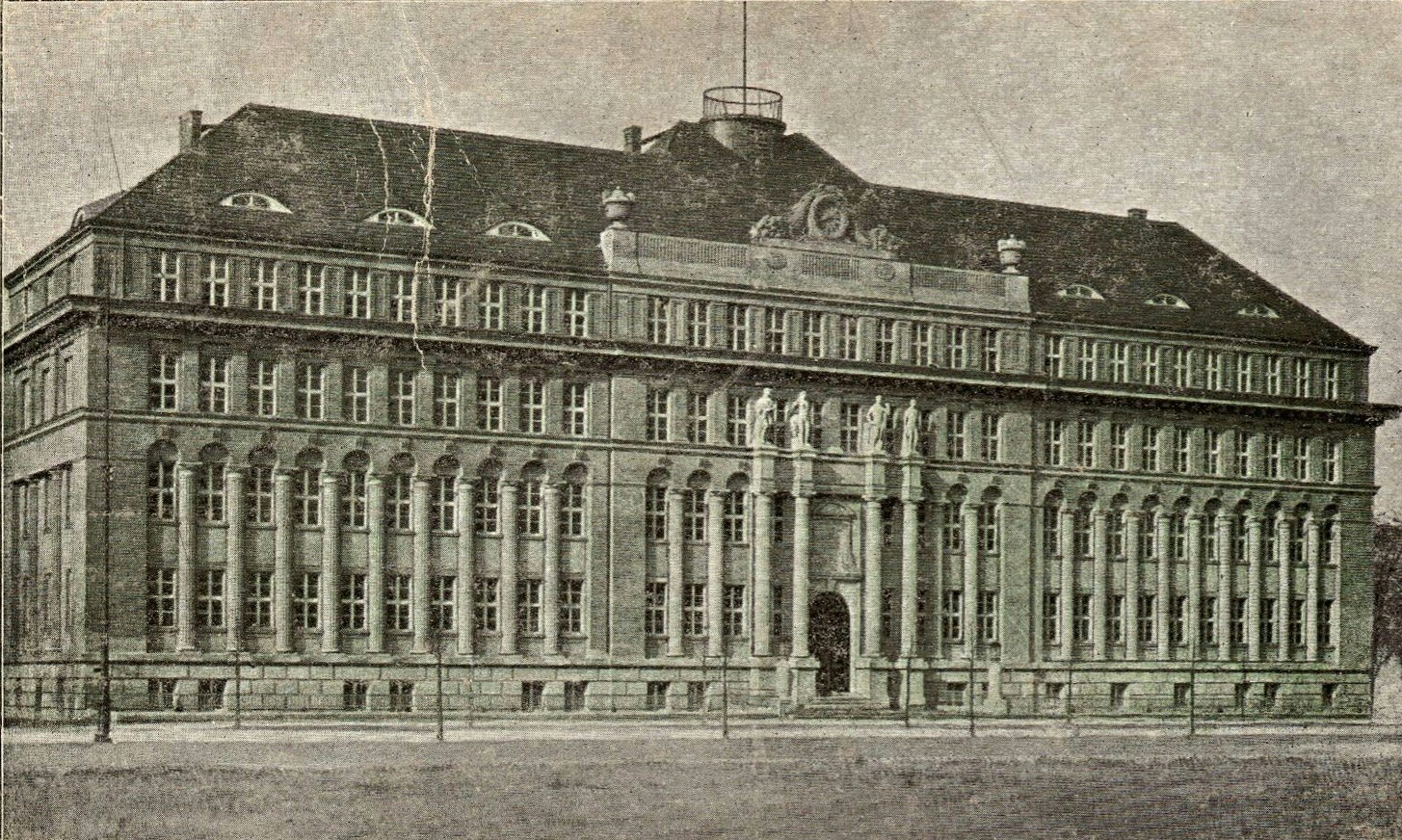

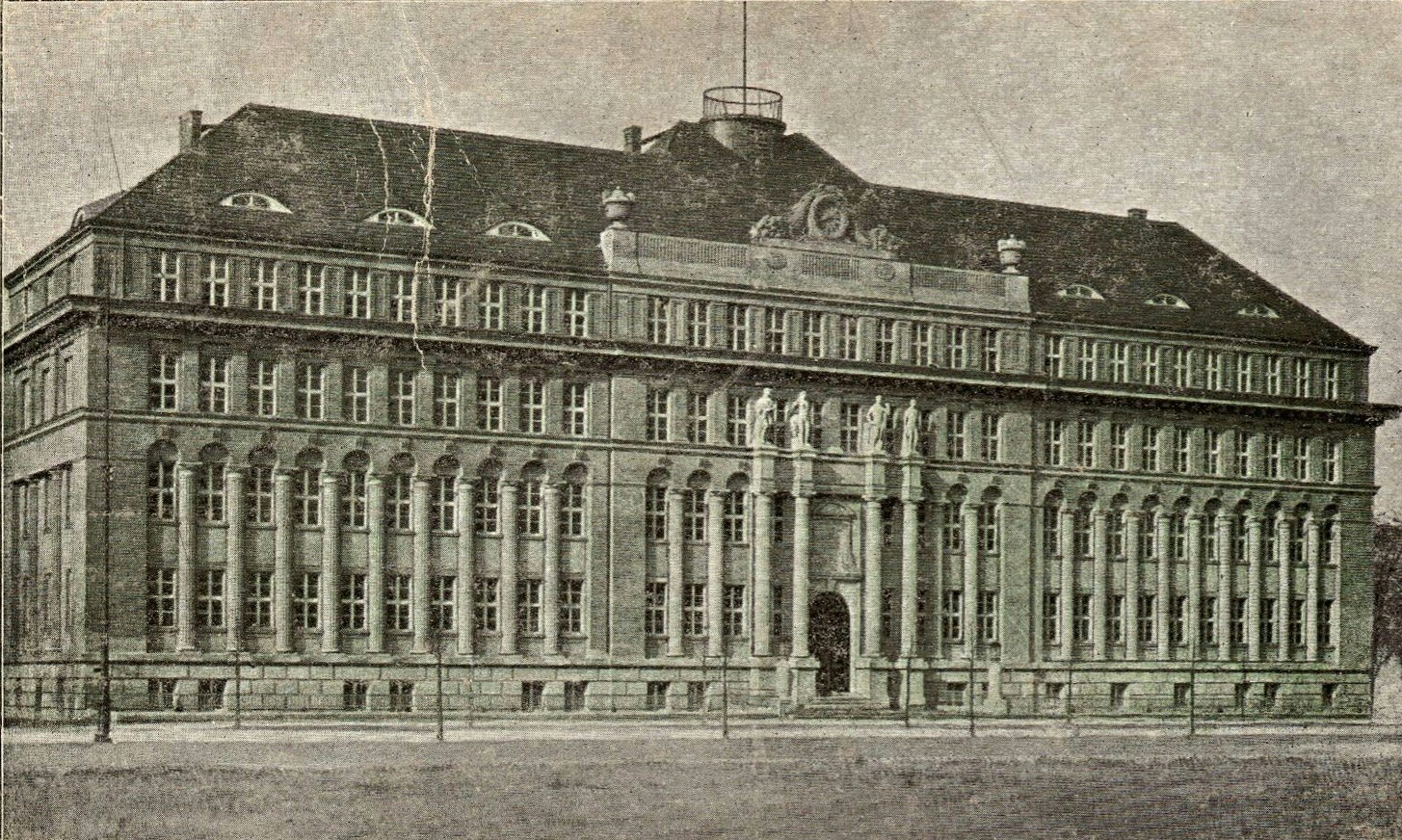

*Various historic public buildings, including the Main Post Office, Voivodeship Administrative Court, the district court

*Teatr Miejski (''Municipal Theatre'')

* Chrobry Park

*Monuments to Adam Mickiewicz

Adam Bernard Mickiewicz (24 December 179826 November 1855) was a Polish poet, dramatist, essayist, publicist, translator and political activist. He is regarded as national poet in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. He also largely influenced Ukra ...

and Tadeusz Kościuszko

Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko (; 4 or 12 February 174615 October 1817) was a Polish Military engineering, military engineer, statesman, and military leader who then became a national hero in Poland, the United States, Lithuania, and ...

*Gliwice Trynek narrow-gauge station is a protected monument. The narrow-gauge line to Racibórz via Rudy closed in 1991 although a short section still remains as a museum line.

*The Weichmann Textile House was built during the Summers of 1921 and 1922 . It was never referred to as Weichmann Textile House from its completion in Summer 1922 until its closing in 1943. Rather it was founded under the name Seidenhaus Weichmann (“Silk

Silk is a natural fiber, natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be weaving, woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is most commonly produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoon (silk), c ...

House Weichmann) by a Jewish WWI

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting took place mainly in Europe and th ...

veteran, Erwin Weichmann(1891–1976), who had been awarded the Iron Cross 2nd Class by Germany. Erwin Weichmann a long time friend of Erich Mendelsohn

Erich Mendelsohn (); 21 March 1887 – 15 September 1953) was a German-British architect, known for his expressionist architecture in the 1920s, as well as for developing a dynamic functionalism in his projects for department stores and cinem ...

, commissioned the architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs, and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

to design Seidenhaus Weichmann. Today a monument can be seen near the entrance to the bank, that now occupies the building. Seidenhaus Weichmann is a two-floor structure. The second floor was initially a bachelor's pad for Erwin Weichmann, as he did not marry until 1930. In 1936 the newly created Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws (, ) were antisemitic and racist laws that were enacted in Nazi Germany on 15 September 1935, at a special meeting of the Reichstag convened during the annual Nuremberg Rally of the Nazi Party. The two laws were the Law ...

forced Erwin Weichmann to sell Seidenhaus Weichmann and move temporarily to Hindenberg (Zabrze

Zabrze (; German: 1915–1945: , full form: , , ) is an industrial city put under direct government rule in Silesia in southern Poland, near Katowice. It lies in the western part of the Metropolis GZM, a metropolis with a population of around 2 m ...

) before emigrating to the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

in July 1938. The individual, who had purchased Seidenhaus Weichmann in 1936, never saw a profit, as the economic strain of WWII

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

severely reduced the market demand for nonessentials, which included the fine imported silks of sold by Seidenhaus Weichmann. Then in 1943, the purchaser of Seidenhaus was killed in an Allied bombing raid, which marked the end of Seidenhaus Weichmann.

Higher education and science

Gliwice is a major applied science hub for the

Gliwice is a major applied science hub for the Metropolis GZM

The Metropolis GZM (, formally in Polish (Upper Silesian-Dąbrowa Basin Metropolis)) is a metropolitan association () composed of 41 contiguous gminas, with a total population of over 2 million, covering most of the Katowice metropolitan area i ...

. Gliwice is a seat of:

* Silesian University of Technology

The Silesian University of Technology (Polish language, Polish name: Politechnika Śląska; ) is a university located in the Polish province of Silesia, with most of its facilities in the city of Gliwice. It was founded in 1945 by Polish profes ...

with about 32,000 students (''Politechnika Śląska'')

* Akademia Polonijna of Częstochowa

Częstochowa ( , ) is a city in southern Poland on the Warta with 214,342 inhabitants, making it the thirteenth-largest city in Poland. It is situated in the Silesian Voivodeship. However, Częstochowa is historically part of Lesser Poland, not Si ...

, branch in Gliwice

* Gliwice College of Entrepreneurship (''Gliwicka Wyższa Szkoła Przedsiębiorczości'')

* Polish Academy of Sciences

The Polish Academy of Sciences (, PAN) is a Polish state-sponsored institution of higher learning. Headquartered in Warsaw, it is responsible for spearheading the development of science across the country by a society of distinguished scholars a ...

(''Polska Akademia Nauk'')

** Institute of Theoretical And Applied Informatics

Informatics is the study of computational systems. According to the Association for Computing Machinery, ACM Europe Council and Informatics Europe, informatics is synonymous with computer science and computing as a profession, in which the centra ...

** Institute of Chemical Engineering

Chemical engineering is an engineering field which deals with the study of the operation and design of chemical plants as well as methods of improving production. Chemical engineers develop economical commercial processes to convert raw materials ...

** Carbochemistry branch

* WSB University, branch in Gliwice

* Other (commercial or government funded) applied research centers:

** Oncological Research Center (Centrum Onkologii)

** Inorganic Chemistry

Inorganic chemistry deals with chemical synthesis, synthesis and behavior of inorganic compound, inorganic and organometallic chemistry, organometallic compounds. This field covers chemical compounds that are not carbon-based, which are the subj ...

Research Institute (Instytut Chemii Nieorganicznej)

** Research Institute of Refractory

In materials science, a refractory (or refractory material) is a material that is resistant to decomposition by heat or chemical attack and that retains its strength and rigidity at high temperatures. They are inorganic, non-metallic compound ...

Materials (Instytut Materiałów Ogniotrwałych)

** Research Institute for Non-Ferrous Metals

In metallurgy, non-ferrous metals are metals or alloy

An alloy is a mixture of chemical elements of which in most cases at least one is a metal, metallic element, although it is also sometimes used for mixtures of elements; herein only meta ...

(Instytut Metali Nieżelaznych)

** Research Institute for Ferrous

In chemistry, iron(II) refers to the chemical element, element iron in its +2 oxidation number, oxidation state. The adjective ''ferrous'' or the prefix ''ferro-'' is often used to specify such compounds, as in ''ferrous chloride'' for iron(II ...

Metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the ...

()

** Welding