Germ Theory on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The germ theory of disease is the currently accepted

The germ theory of disease is the currently accepted

The miasma theory was the predominant theory of disease transmission before the germ theory took hold towards the end of the 19th century; it is no longer accepted as a correct explanation for disease by the scientific community. It held that diseases such as

The miasma theory was the predominant theory of disease transmission before the germ theory took hold towards the end of the 19th century; it is no longer accepted as a correct explanation for disease by the scientific community. It held that diseases such as

During the mid-19th century, French microbiologist

During the mid-19th century, French microbiologist

online

* Geison, Gerald L. ''The Private Science of Louis Pasteur'' (Princeton University Press, 1995

online

* Hudson, Robert P. ''Disease and Its Control: The Shaping of Modern Thought'' (1983) * Lawrence, Christopher, and Richard Dixey. "Practising on Principle: Joseph Lister and the Germ Theories of Disease," in ''Medical Theory, Surgical Practice: Studies in the History of Surgery'' ed. by Christopher Lawrence (Routledge, 1992), pp. 153-215. * Magner, Lois N. ''A history of infectious diseases and the microbial world'' (2008

online

* Magner, Lois N. ''A History of Medicine'' (1992) pp. 305–334

online

* Nutton, Vivian. "The seeds of disease: an explanation of contagion and infection from the Greeks to the Renaissance." ''Medical history'' 27.1 (1983): 1-34

online

* Porter, Roy. ''Blood and Guts: A Short History of Medicine'' (2004

online

* Tomes, Nancy. 'The gospel of germs: Men, women, and the microbe in American life'' (Harvard University Press, 1999

online

* Tomes, Nancy. "Moralizing the microbe: the germ theory and the moral construction of behavior in the late-nineteenth-century antituberculosis movement." in ''Morality and health'' (Routledge, 2013) pp. 271-294. * Tomes, Nancy J. "American attitudes toward the germ theory of disease: Phyllis Allen Richmond revisited." ''Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences'' 52.1 (1997): 17-50

online

* Winslow, Charles-Edward Amory. ''The Conquest of Epidemic Disease. A Chapter in the History of Ideas'' (1943

online

John Horgan, "Germ Theory" (2023)

* Stephen T. Abedo

Supplemental Lecture (98/03/28 update), ''www.mansfield.ohio-state.edu'' * William C. Campbel

The Germ Theory Timeline

''germtheorytimeline.info''

''www.creatingtechnology.org'' {{Authority control Biology theories History of biology History of medicine > Microbiology

The germ theory of disease is the currently accepted

The germ theory of disease is the currently accepted scientific theory

A scientific theory is an explanation of an aspect of the universe, natural world that can be or that has been reproducibility, repeatedly tested and has corroborating evidence in accordance with the scientific method, using accepted protocol (s ...

for many disease

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that adversely affects the structure or function (biology), function of all or part of an organism and is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical condi ...

s. It states that microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic scale, microscopic size, which may exist in its unicellular organism, single-celled form or as a Colony (biology)#Microbial colonies, colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen ...

s known as pathogen

In biology, a pathogen (, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of"), in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a Germ theory of d ...

s or "germs" can cause disease. These small organisms, which are too small to be seen without magnification, invade animals, plants, and even bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

. Their growth and reproduction within their hosts can cause disease. "Germ" refers not just to bacteria but to any type of microorganism, such as protists

A protist ( ) or protoctist is any Eukaryote, eukaryotic organism that is not an animal, Embryophyte, land plant, or fungus. Protists do not form a Clade, natural group, or clade, but are a Paraphyly, paraphyletic grouping of all descendants o ...

or fungi

A fungus (: fungi , , , or ; or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as one ...

, or other pathogens, including parasites

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives (at least some of the time) on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The en ...

, virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are ...

es, prions, or viroids

Viroids are small single-stranded, circular RNAs that are infectious pathogens. Unlike viruses, they have no protein coating. All known viroids are inhabitants of angiosperms (flowering plants), and most cause diseases, whose respective econo ...

. Diseases caused by pathogens are called infectious disease

An infection is the invasion of tissue (biology), tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host (biology), host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmis ...

s. Even when a pathogen is the principal cause of a disease, environmental and hereditary factors often influence the severity of the disease, and whether a potential host individual becomes infected when exposed to the pathogen. Pathogens are disease-causing agents that can pass from one individual to another, across multiple domains of life.

Basic forms of germ theory were proposed by Girolamo Fracastoro in 1546, and expanded upon by Marcus von Plenciz in 1762. However, such views were held in disdain in Europe, where Galen's miasma theory

The miasma theory (also called the miasmic theory) is an abandoned medical theory that held that diseases—such as cholera, chlamydia, or plague—were caused by a ''miasma'' (, Ancient Greek for 'pollution'), a noxious form of "bad air", a ...

remained dominant among scientists and doctors.

By the early 19th century, the first vaccine

A vaccine is a biological Dosage form, preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease, infectious or cancer, malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verifi ...

, smallpox vaccination, was commonplace in Europe, though doctors were unaware of how it worked or how to extend the principle to other diseases. A transitional period began in the late 1850s with the work of Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist, pharmacist, and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, Fermentation, microbial fermentation, and pasteurization, the la ...

. This work was later extended by Robert Koch

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch ( ; ; 11 December 1843 – 27 May 1910) was a German physician and microbiologist. As the discoverer of the specific causative agents of deadly infectious diseases including tuberculosis, cholera and anthrax, he i ...

in the 1880s. By the end of that decade, the miasma theory was struggling to compete with the germ theory of disease. Viruses were initially discovered in the 1890s. Eventually, a "golden era" of bacteriology

Bacteriology is the branch and specialty of biology that studies the Morphology (biology), morphology, ecology, genetics and biochemistry of bacteria as well as many other aspects related to them. This subdivision of microbiology involves the iden ...

ensued, during which the germ theory quickly led to the identification of the actual organisms that cause many diseases.

Miasma theory

The miasma theory was the predominant theory of disease transmission before the germ theory took hold towards the end of the 19th century; it is no longer accepted as a correct explanation for disease by the scientific community. It held that diseases such as

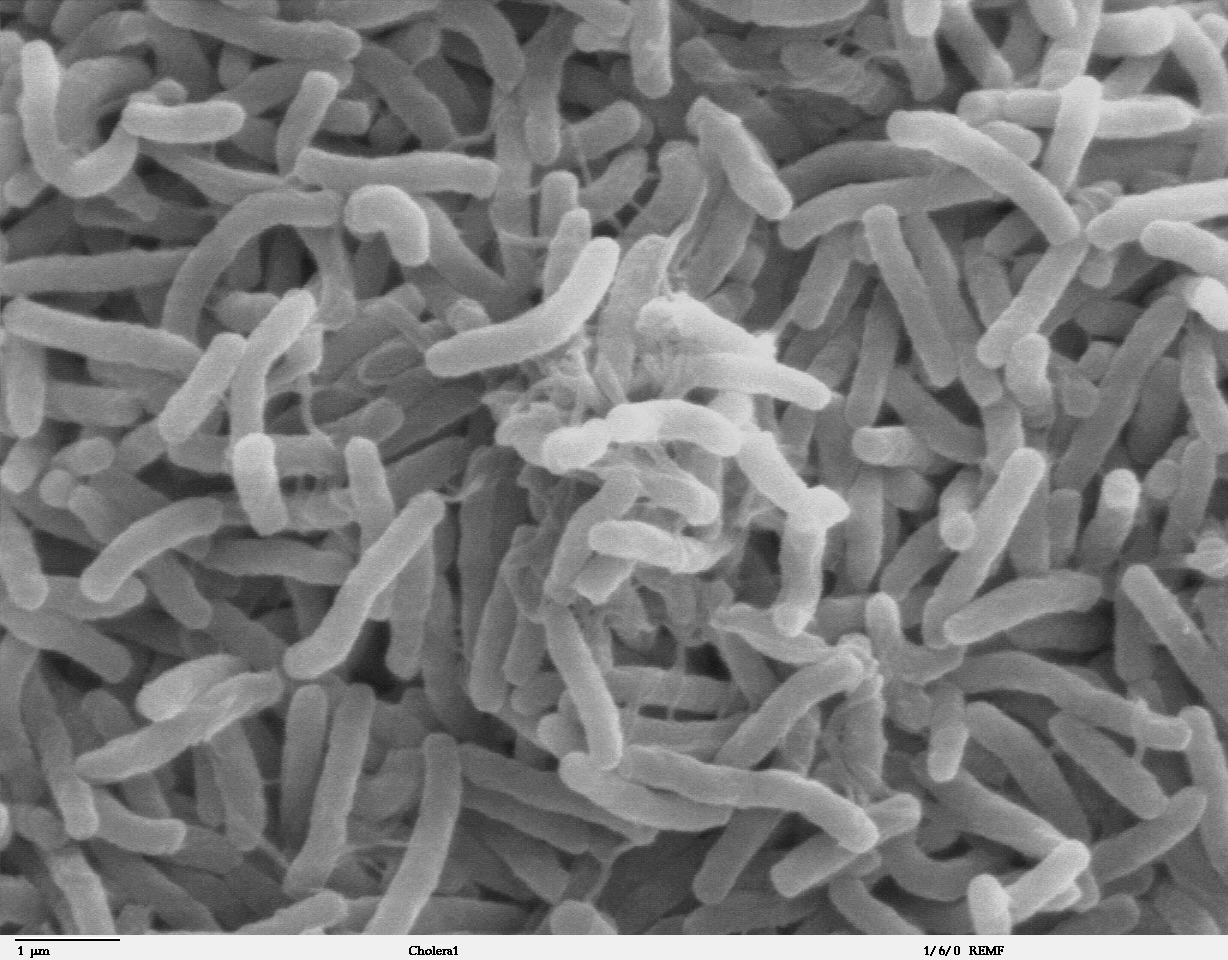

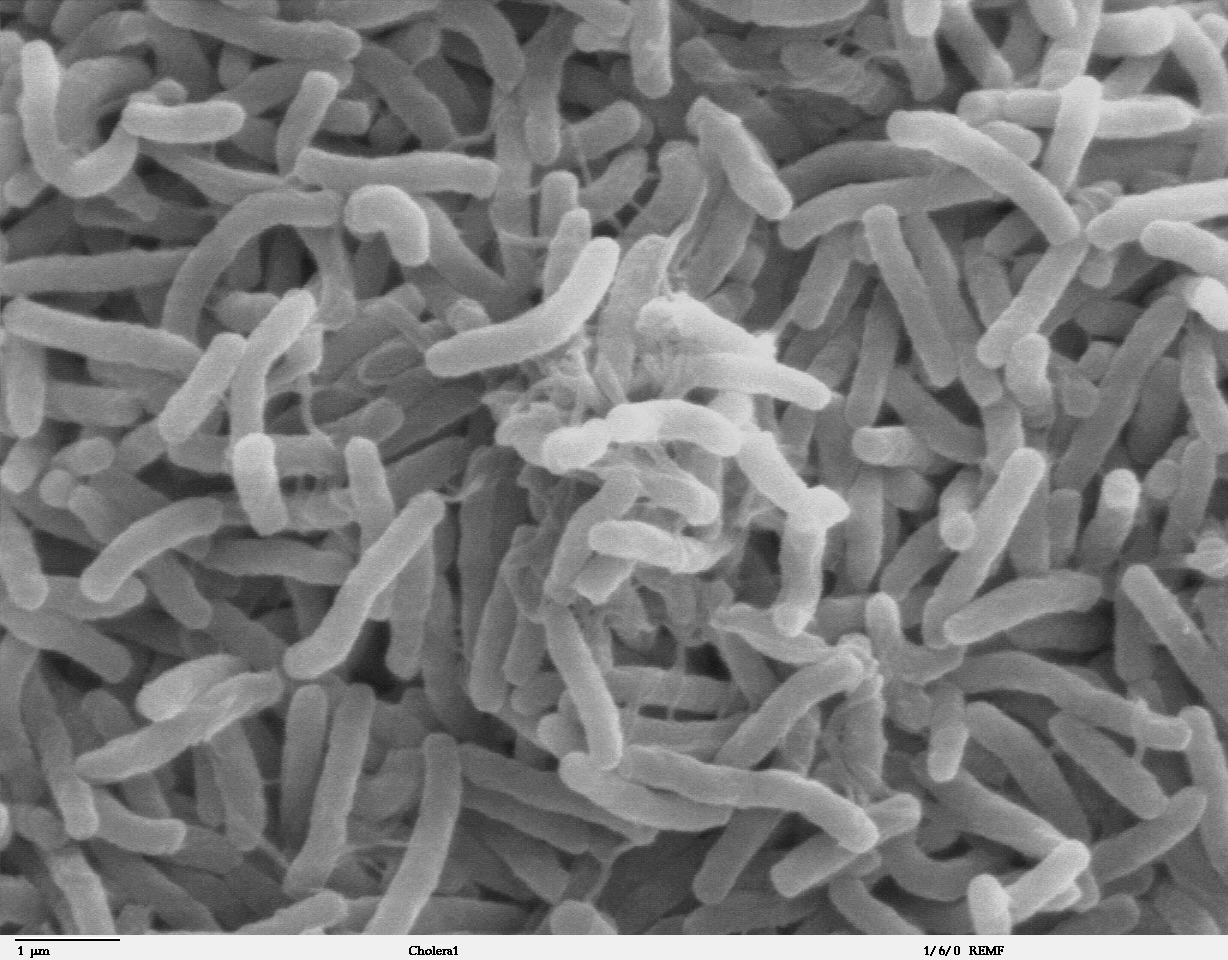

The miasma theory was the predominant theory of disease transmission before the germ theory took hold towards the end of the 19th century; it is no longer accepted as a correct explanation for disease by the scientific community. It held that diseases such as cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

, chlamydia infection

Chlamydia, or more specifically a chlamydia infection, is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Chlamydia trachomatis''. Most people who are infected have no symptoms. When symptoms do appear, they may occur only several w ...

, or the Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

were caused by a (, Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

: "pollution"), a noxious form of "bad air" emanating from rotting organic matter. Miasma was considered to be a poisonous vapor or mist filled with particles from decomposed matter (miasmata) that was identifiable by its foul smell. The theory posited that diseases were the product of environmental factors such as contaminated water, foul air, and poor hygienic conditions. Such infections, according to the theory, were not passed between individuals but would affect those within a locale that gave rise to such vapors.

Development of germ theory

Greece and Rome

In Antiquity, the Greek historianThucydides

Thucydides ( ; ; BC) was an Classical Athens, Athenian historian and general. His ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts Peloponnesian War, the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been d ...

( – ) was the first person to write, in his account of the plague of Athens

The Plague of Athens (, ) was an epidemic that devastated the city-state of Athens in ancient Greece during the second year (430 BC) of the Peloponnesian War when an Athenian victory still seemed within reach. The plague killed an estimated 75, ...

, that diseases could spread from an infected person to others.

One theory of the spread of contagious diseases that were not spread by direct contact was that they were spread by spore

In biology, a spore is a unit of sexual reproduction, sexual (in fungi) or asexual reproduction that may be adapted for biological dispersal, dispersal and for survival, often for extended periods of time, in unfavourable conditions. Spores fo ...

-like "seeds" (Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

: ''semina'') that were present in and dispersible through the air. In his poem, ''De rerum natura

(; ''On the Nature of Things'') is a first-century BC Didacticism, didactic poem by the Roman Republic, Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius () with the goal of explaining Epicureanism, Epicurean philosophy to a Roman audience. The poem, writte ...

'' (On the Nature of Things, ), the Roman poet Lucretius

Titus Lucretius Carus ( ; ; – October 15, 55 BC) was a Roman poet and philosopher. His only known work is the philosophical poem '' De rerum natura'', a didactic work about the tenets and philosophy of Epicureanism, which usually is t ...

( – ) stated that the world contained various "seeds", some of which could sicken a person if they were inhaled or ingested.

The Roman statesman Marcus Terentius Varro

Marcus Terentius Varro (116–27 BCE) was a Roman polymath and a prolific author. He is regarded as ancient Rome's greatest scholar, and was described by Petrarch as "the third great light of Rome" (after Virgil and Cicero). He is sometimes call ...

(116–27 BC) wrote, in his ''Rerum rusticarum libri III'' (Three Books on Agriculture, 36 BC): "Precautions must also be taken in the neighborhood of swamps... because there are bred certain minute creatures which cannot be seen by the eyes, which float in the air and enter the body through the mouth and nose and there cause serious diseases."

The Greek physician Galen (AD 129 – ) speculated in his ''On Initial Causes'' () that some patients might have "seeds of fever". In his ''On the Different Types of Fever'' (), Galen speculated that plagues were spread by "certain seeds of plague", which were present in the air. And in his ''Epidemics'' (), Galen explained that patients might relapse during recovery from fever because some "seed of the disease" lurked in their bodies, which would cause a recurrence of the disease if the patients did not follow a physician's therapeutic regimen.

The Middle Ages

A hybrid form of miasma and contagion theory was proposed by Persian physicianIbn Sina

Ibn Sina ( – 22 June 1037), commonly known in the West as Avicenna ( ), was a preeminent philosopher and physician of the Muslim world, flourishing during the Islamic Golden Age, serving in the courts of various Iranian peoples, Iranian ...

(known as Avicenna in Europe) in ''The Canon of Medicine

''The Canon of Medicine'' () is an encyclopedia of medicine in five books compiled by Avicenna (, ibn Sina) and completed in 1025. It is among the most influential works of its time. It presents an overview of the contemporary medical knowle ...

'' (1025). He mentioned that people can transmit disease to others by breath, noted contagion with tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

, and discussed the transmission of disease through water and dirt.

During the early Middle Ages, Isidore of Seville

Isidore of Seville (; 4 April 636) was a Spania, Hispano-Roman scholar, theologian and Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Seville, archbishop of Seville. He is widely regarded, in the words of the 19th-century historian Charles Forbes René de Montal ...

(–636) mentioned "plague-bearing seeds" (''pestifera semina'') in his ''On the Nature of Things'' (). Later in 1345, Tommaso del Garbo (–1370) of Bologna, Italy mentioned Galen's "seeds of plague" in his work ''Commentaria non-parum utilia in libros Galeni'' (Helpful commentaries on the books of Galen).

The 16th century Reformer Martin Luther

Martin Luther ( ; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, Theology, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and former Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Reformation, Pr ...

appears to have had some idea of the contagion theory, commenting, "I have survived three plagues and visited several people who had two plague spots which I touched. But it did not hurt me, thank God. Afterwards when I returned home, I took up Margaret," (born 1534), "who was then a baby, and put my unwashed hands on her face, because I had forgotten; otherwise I should not have done it, which would have been tempting God." In 1546, Italian physician Girolamo Fracastoro published ''De Contagione et Contagiosis Morbis'' (''On Contagion and Contagious Diseases''), a set of three books covering the nature of contagious diseases, categorization of major pathogens, and theories on preventing and treating these conditions. Fracastoro blamed "seeds of disease" that propagate through direct contact with an infected host, indirect contact with fomite

A fomite () or fomes () is any inanimate object that, when contaminated with or exposed to infectious agents (such as pathogenic bacteria, viruses or fungi), can transfer disease to a new host.

Transfer of pathogens by fomites

A fomite is any ...

s, or through particles in the air.

The Early Modern Period

In 1668, Italian physicianFrancesco Redi

Francesco Redi (18 February 1626 – 1 March 1697) was an Italians, Italian physician, naturalist, biologist, and poet. He is referred to as the "founder of experimental biology", and as the "father of modern parasitology". He was the first perso ...

published experimental evidence rejecting spontaneous generation

Spontaneous generation is a superseded scientific theory that held that living creatures could arise from non-living matter and that such processes were commonplace and regular. It was hypothesized that certain forms, such as fleas, could ...

, the theory that living creatures arise from nonliving matter. He observed that maggots only arose from rotting meat that was uncovered. When meat was left in jars covered by gauze, the maggots would instead appear on the gauze's surface, later understood as rotting meat's smell passing through the mesh to attract flies that laid eggs.

Microorganisms are said to have been first directly observed in the 1670s by Anton van Leeuwenhoek

Antonie Philips van Leeuwenhoek ( ; ; 24 October 1632 – 26 August 1723) was a Dutch microbiologist and microscopist in the Golden Age of Dutch art, science and technology. A largely self-taught man in science, he is commonly known as " ...

, an early pioneer in microbiology

Microbiology () is the branches of science, scientific study of microorganisms, those being of unicellular organism, unicellular (single-celled), multicellular organism, multicellular (consisting of complex cells), or non-cellular life, acellula ...

, considered "the Father of Microbiology". Leeuwenhoek is said to be the first to see and describe bacteria in 1674, yeast cells, the teeming life in a drop of water (such as algae), and the circulation of blood corpuscles in capillaries. The word "bacteria" didn't exist yet, so he called these microscopic living organisms "animalcules", meaning "little animals". Those "very little animalcules" he was able to isolate from different sources, such as rainwater, pond and well water, and the human mouth and intestine.

Yet German Jesuit priest and scholar Athanasius Kircher

Athanasius Kircher (2 May 1602 – 27 November 1680) was a German Society of Jesus, Jesuit scholar and polymath who published around 40 major works of comparative religion, geology, and medicine. Kircher has been compared to fellow Jes ...

(or "Kirchner", as it is often spelled) may have observed such microorganisms prior to this. One of his books written in 1646 contains a chapter in Latin, which reads in translation: "Concerning the wonderful structure of things in nature, investigated by microscope...who would believe that vinegar and milk abound with an innumerable multitude of worms." Kircher defined the invisible organisms found in decaying bodies, meat, milk, and secretions as "worms." His studies with the microscope led him to the belief, which he was possibly the first to hold, that disease and putrefaction, or decay were caused by the presence of invisible living bodies, writing that "a number of things might be discovered in the blood of fever patients." When Rome was struck by the bubonic plague in 1656, Kircher investigated the blood of plague victims under the microscope. He noted the presence of "little worms" or "animalcules" in the blood and concluded that the disease was caused by microorganisms.

Kircher was the first to attribute infectious disease to a microscopic pathogen, inventing the germ theory of disease, which he outlined in his '' Scrutinium Physico-Medicum'', published in Rome in 1658. Kircher's conclusion that disease was caused by microorganisms was correct, although it is likely that what he saw under the microscope were in fact red or white blood cells and not the plague agent itself. Kircher also proposed hygienic measures to prevent the spread of disease, such as isolation, quarantine, burning clothes worn by the infected, and wearing facemasks to prevent the inhalation of germs. It was Kircher who first proposed that living beings enter and exist in the blood.

In the 18th century, more proposals were made, but struggled to catch on. In 1700, physician Nicolas Andry

Nicolas Andry de Bois-Regard (1658 – 13 May 1742) was a French physician and writer. He played a significant role in the early history of both parasitology and orthopedics, the name for which is taken from Andry's book ''Orthopédie''.

Early li ...

argued that microorganisms he called "worms" were responsible for smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

and other diseases. In 1720, Richard Bradley theorised that the plague and "all pestilential distempers" were caused by "poisonous insects", living creatures viewable only with the help of microscopes.

In 1762, the Austrian physician Marcus Antonius von Plenciz (1705–1786) published a book titled ''Opera medico-physica''. It outlined a theory of contagion stating that specific animalcule

Animalcule (; ) is an archaic term for microscopic organisms that included bacteria, protozoans, and very small animals. The word was invented by 17th-century Dutch scientist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek to refer to the microorganisms he observed i ...

s in the soil and the air were responsible for causing specific diseases. Von Plenciz noted the distinction between diseases which are both epidemic and contagious (like measles and dysentery), and diseases which are contagious but not epidemic (like rabies and leprosy). The book cites Anton van Leeuwenhoek to show how ubiquitous such animalcules are and was unique for describing the presence of germs in ulcerating wounds. Ultimately, the theory espoused by von Plenciz was not accepted by the scientific community.

19th and 20th centuries

Agostino Bassi, Italy

During the early 19th century, driven by economic concerns over collapsing silk production, Italian entomologistAgostino Bassi

Agostino Bassi, sometimes called de Lodi (25 September 1773 – 8 February 1856), was an Italian entomologist. He preceded Louis Pasteur in the discovery that microorganisms can be the cause of disease (the germ theory of disease). He discovere ...

researched a silkworm

''Bombyx mori'', commonly known as the domestic silk moth, is a moth species belonging to the family Bombycidae. It is the closest relative of '' Bombyx mandarina'', the wild silk moth. Silkworms are the larvae of silk moths. The silkworm is of ...

disease known as "muscardine" in French and "calcinaccio" or "mal del segno" in Italian, causing white fungal spots along the caterpillar. From 1835 to 1836, Bassi published his findings that fungal spores transmitted the disease between individuals. In recommending the rapid removal of diseased caterpillars and disinfection of their surfaces, Bassi outlined methods used in modern preventative healthcare. Italian naturalist Giuseppe Gabriel Balsamo-Crivelli named the causative fungal species after Bassi, currently classified as '' Beauveria bassiana''.

Louis-Daniel Beauperthuy, France

In 1838 French specialist in tropical medicine Louis-Daniel Beauperthuy pioneered using microscopy in relation to diseases and independently developed a theory that all infectious diseases were due to parasitic infection with "animalcule

Animalcule (; ) is an archaic term for microscopic organisms that included bacteria, protozoans, and very small animals. The word was invented by 17th-century Dutch scientist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek to refer to the microorganisms he observed i ...

s" (microorganisms). With the help of his friend M. Adele de Rosseville, he presented his theory in a formal presentation before the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

in Paris. By 1853, he was convinced that malaria and yellow fever were spread by mosquitos. He even identified the particular group of mosquitos that transmit yellow fever as the "domestic species" of "striped-legged mosquito", which can be recognised as ''Aedes aegypti'', the actual vector. He published his theory in 1854 in the Gaceta Oficial de Cumana ("Official Gazette of Cumana"). His reports were assessed by an official commission, which discarded his mosquito theory.

Ignaz Semmelweis, Austria

Ignaz Semmelweis

Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis (; ; 1 July 1818 – 13 August 1865) was a Hungarian physician and scientist of German descent who was an early pioneer of antiseptic procedures and was described as the "saviour of mothers". Postpartum infections, ...

, a Hungarian obstetrician

Obstetrics is the field of study concentrated on pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period. As a medical specialty, obstetrics is combined with gynecology under the discipline known as obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN), which is a surgi ...

working at the Vienna General Hospital

The Vienna General Hospital (), usually abbreviated to AKH, is the general hospital in Vienna, Austria. It is also the city's university hospital, and the site of the Medical University of Vienna. It is Europe's fifth largest hospital, b ...

(''Allgemeines Krankenhaus'') in 1847, noticed the dramatically high maternal mortality from puerperal fever

The postpartum (or postnatal) period begins after childbirth and is typically considered to last for six to eight weeks. There are three distinct phases of the postnatal period; the acute phase, lasting for six to twelve hours after birth; the ...

following births assisted by doctors and medical students. However, those attended by midwives

A midwife (: midwives) is a health professional who cares for mothers and newborns around childbirth, a specialisation known as midwifery.

The education and training for a midwife concentrates extensively on the care of women throughout their ...

were relatively safe. Investigating further, Semmelweis made the connection between puerperal fever and examinations of delivering women by doctors, and further realized that these physicians had usually come directly from autopsies

An autopsy (also referred to as post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death; ...

. Asserting that puerperal fever was a contagious disease

A contagious disease is an infectious disease that can be spread rapidly in several ways, including direct contact, indirect contact, and droplet contact.

These diseases are caused by organisms such as parasites, bacteria, fungi, and viruses. ...

and that matter from autopsies was implicated in its spread, Semmelweis made doctors wash their hands with chlorinated lime water before examining pregnant women. He then documented a sudden reduction in the mortality rate from 18% to 2.2% over a period of a year. Despite this evidence, he and his theories were rejected by most of the contemporary medical establishment.

Gideon Mantell, UK

Gideon Mantell

Gideon Algernon Mantell Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons, MRCS Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (3 February 1790 – 10 November 1852) was an English obstetrician, geologist and paleontology, palaeontologist. His attempts to reconstr ...

, the Sussex doctor more famous for discovering dinosaur fossils, spent time with his microscope, and speculated in his ''Thoughts on Animalcules'' (1850) that perhaps "many of the most serious maladies which afflict humanity, are produced by peculiar states of invisible animalcular life".

John Snow, UK

British physicianJohn Snow

John Snow (15 March 1813 – 16 June 1858) was an English physician and a leader in the development of anaesthesia and medical hygiene. He is considered one of the founders of modern epidemiology and early germ theory, in part because of hi ...

is credited as a founder of modern epidemiology

Epidemiology is the study and analysis of the distribution (who, when, and where), patterns and Risk factor (epidemiology), determinants of health and disease conditions in a defined population, and application of this knowledge to prevent dise ...

for studying the 1854 Broad Street cholera outbreak

The Broad Street cholera outbreak (or Golden Square outbreak) was a severe outbreak of cholera that occurred in 1854 near Broad Street (now Broadwick Street) in Soho, London, England, during the worldwide 1846–1860 cholera pandemic. The Broa ...

. Snow criticized the Italian anatomist Giovanni Maria Lancisi for his early 18th century writings that claimed swamp miasma spread malaria, rebutting that bad air from decomposing organisms was not present in all cases. In his 1849 pamphlet ''On the Mode of Communication of Cholera,'' Snow proposed that cholera spread through the fecal–oral route

The fecal–oral route (also called the oral–fecal route or orofecal route) describes a particular route of transmission of a disease wherein pathogens in fecal particles pass from one person to the mouth of another person. Main causes of fec ...

, replicating in human lower intestines.

In the book's second edition, published in 1855, Snow theorized that cholera was caused by cells smaller than human epithelial cells, leading to Robert Koch's 1884 confirmation of the bacterial species ''Vibrio cholerae

''Vibrio cholerae'' is a species of Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-negative, Facultative anaerobic organism, facultative anaerobe and Vibrio, comma-shaped bacteria. The bacteria naturally live in Brackish water, brackish or saltwater where they att ...

'' as the causative agent. In recognizing a biological origin, Snow recommended boiling and filtering water, setting the precedent for modern boil-water advisory

A boil-water advisory (BWA), boil-water notice, boil-water warning, boil-water order, or boil order is a Public health, public-health advisory or directive issued by governmental or other health authorities to consumers when a community's drinkin ...

directives.

Through a statistical analysis tying cholera cases to specific water pumps associated with the Southwark and Vauxhall Waterworks Company, which supplied sewage-polluted water from the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, s ...

, Snow showed that areas supplied by this company experienced fourteen times as many deaths as residents using Lambeth Waterworks Company pumps that obtained water from the upriver, cleaner Seething Wells. While Snow received praise for convincing the Board of Guardians of St James's Parish to remove the handles of contaminated pumps, he noted that the outbreak's cases were already declining as scared residents fled the region.

Louis Pasteur, France

During the mid-19th century, French microbiologist

During the mid-19th century, French microbiologist Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist, pharmacist, and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, Fermentation, microbial fermentation, and pasteurization, the la ...

showed that treating the female genital tract with boric acid

Boric acid, more specifically orthoboric acid, is a compound of boron, oxygen, and hydrogen with formula . It may also be called hydrogen orthoborate, trihydroxidoboron or boracic acid. It is usually encountered as colorless crystals or a white ...

killed the microorganisms causing postpartum infections

Postpartum infections, also known as childbed fever and puerperal fever, are any bacterial infections of the female reproductive tract following childbirth or miscarriage. Signs and symptoms usually include a fever greater than , chills, lower ...

while avoiding damage to mucous membrane

A mucous membrane or mucosa is a membrane that lines various cavities in the body of an organism and covers the surface of internal organs. It consists of one or more layers of epithelial cells overlying a layer of loose connective tissue. It ...

s.

Building on Redi's work, Pasteur disproved spontaneous generation by constructing swan neck flasks containing nutrient broth. Since the flask contents were only fermented when in direct contact with the external environment's air by removing the curved tubing, Pasteur demonstrated that bacteria must travel between sites of infection to colonize environments.

Similar to Bassi, Pasteur extended his research on germ theory by studying pébrine

Pébrine, or "pepper disease," is a disease of silkworms, which is caused by protozoan microsporidian parasites, mainly ''Nosema bombycis'' and, to a lesser extent, ''Vairimorpha'', ''Pleistophora'' and ''Thelohania'' species. The parasites infect ...

, a disease that causes brown spots on silkworms. While Swiss botanist Carl Nägeli

Carl Wilhelm von Nägeli (26 or 27 March 1817 – 10 May 1891) was a Swiss botanist. He studied cell division and pollination but became known as the man who discouraged Gregor Mendel from further work on genetics. He rejected natural selecti ...

discovered the fungal species ''Nosema bombycis

''Nosema bombycis'' is a species of Microsporidia of the genus ''Nosema (microsporidian), Nosema'' infecting Bombyx mori, silkworms, responsible for pébrine.

This species was the first microsporidium described, when pebrine decimated silkworms i ...

'' in 1857, Pasteur applied the findings to recommend improved ventilation and screening of silkworm eggs, an early form of disease surveillance

Disease surveillance is an epidemiological practice by which the spread of disease is monitored in order to establish patterns of progression. The main role of disease surveillance is to predict, observe, and minimize the harm caused by outbrea ...

.

Robert Koch, Germany

In 1884, German bacteriologistRobert Koch

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch ( ; ; 11 December 1843 – 27 May 1910) was a German physician and microbiologist. As the discoverer of the specific causative agents of deadly infectious diseases including tuberculosis, cholera and anthrax, he i ...

published four criteria for establishing causality between specific microorganisms and diseases, now known as Koch's postulates

Koch's postulates ( ) are four criteria designed to establish a causality, causal relationship between a microbe and a disease. The postulates were formulated by Robert Koch and Friedrich Loeffler in 1884, based on earlier concepts described by ...

:

# The microorganism must be found in abundance in all organisms with the disease, but should not be found in healthy organisms.

# The microorganism must be isolated from a diseased organism and grown in pure culture

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

.

# The cultured microorganism should cause disease when introduced into a healthy organism.

# The microorganism must be re-isolated from the inoculated, diseased experimental host and identified as being identical to the original specific causative agent.

During his lifetime, Koch recognized that the postulates were not universally applicable, such as asymptomatic carrier

An asymptomatic carrier is a person or other organism that has become infected with a pathogen, but shows no signs or symptoms.

Although unaffected by the pathogen, carriers can transmit it to others or develop symptoms in later stages of the d ...

s of cholera violating the first postulate. For this same reason, the third postulate specifies "should", rather than "must", because not all host organisms exposed to an infectious agent will acquire the infection, potentially due to differences in prior exposure to the pathogen. Limiting the second postulate, it was later discovered that viruses cannot be grown in pure cultures because they are obligate intracellular parasites, making it impossible to fulfill the second postulate. Similarly, pathogenic misfolded proteins, known as prion

A prion () is a Proteinopathy, misfolded protein that induces misfolding in normal variants of the same protein, leading to cellular death. Prions are responsible for prion diseases, known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSEs), w ...

s, only spread by transmitting their structure to other proteins, rather than self-replicating.

While Koch's postulates retain historical importance for emphasizing that correlation does not imply causation

The phrase "correlation does not imply causation" refers to the inability to legitimately deduce a cause-and-effect relationship between two events or variables solely on the basis of an observed association or correlation between them. The id ...

, many pathogens are accepted as causative agents of specific diseases without fulfilling all of the criteria. In 1988, American microbiologist Stanley Falkow published a molecular version of Koch's postulates to establish correlation between microbial genes and virulence factor

Virulence factors (preferably known as pathogenicity factors or effectors in botany) are cellular structures, molecules and regulatory systems that enable microbial pathogens (bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa) to achieve the following:

* c ...

s.

Joseph Lister, UK

After reading Pasteur's papers on bacterial fermentation, British surgeon Joseph Lister recognized that compound fractures, involving bones breaking through the skin, were more likely to become infected due to exposure to environmental microorganisms. He recognized thatcarbolic acid

Phenol (also known as carbolic acid, phenolic acid, or benzenol) is an aromatic organic compound with the molecular formula . It is a white crystalline solid that is volatile and can catch fire.

The molecule consists of a phenyl group () bon ...

could be applied to the site of injury as an effective antiseptic.

See also

*Alexander Fleming

Sir Alexander Fleming (6 August 1881 – 11 March 1955) was a Scottish physician and microbiologist, best known for discovering the world's first broadly effective antibiotic substance, which he named penicillin. His discovery in 1928 of wha ...

* Cell theory

In biology, cell theory is a scientific theory first formulated in the mid-nineteenth century, that living organisms are made up of cells, that they are the basic structural/organizational unit of all organisms, and that all cells come from pr ...

* Cooties

* Epidemiology

Epidemiology is the study and analysis of the distribution (who, when, and where), patterns and Risk factor (epidemiology), determinants of health and disease conditions in a defined population, and application of this knowledge to prevent dise ...

* Germ theory denialism

* History of emerging infectious diseases

* History of public health in the United Kingdom

* Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath who was active as a physicist ("natural philosopher"), astronomer, geologist, meteorologist, and architect. He is credited as one of the first scientists to investigate living ...

* Rudolf Virchow

Rudolf Ludwig Carl Virchow ( ; ; 13 October 18215 September 1902) was a German physician, anthropologist, pathologist, prehistorian, biologist, writer, editor, and politician. He is known as "the father of modern pathology" and as the founder o ...

* Zymotic disease

References

Further reading

* Baldwin, Peter. ''Contagion and the State in Europe, 1830-1930'' (Cambridge UP, 1999), focus on cholera, smallpox and syphilis in Britain, France, Germany and Sweden. * Brock, Thomas D. ''Robert Koch. A Life in Medicine and Bacteriology'' (1988). * Dubos, René. ''Louis Pasteur: Free Lance of Science'' (1986) * Gaynes, Robert P. ''Germ Theory'' (ASM Press, 2023), pp.143-20online

* Geison, Gerald L. ''The Private Science of Louis Pasteur'' (Princeton University Press, 1995

online

* Hudson, Robert P. ''Disease and Its Control: The Shaping of Modern Thought'' (1983) * Lawrence, Christopher, and Richard Dixey. "Practising on Principle: Joseph Lister and the Germ Theories of Disease," in ''Medical Theory, Surgical Practice: Studies in the History of Surgery'' ed. by Christopher Lawrence (Routledge, 1992), pp. 153-215. * Magner, Lois N. ''A history of infectious diseases and the microbial world'' (2008

online

* Magner, Lois N. ''A History of Medicine'' (1992) pp. 305–334

online

* Nutton, Vivian. "The seeds of disease: an explanation of contagion and infection from the Greeks to the Renaissance." ''Medical history'' 27.1 (1983): 1-34

online

* Porter, Roy. ''Blood and Guts: A Short History of Medicine'' (2004

online

* Tomes, Nancy. 'The gospel of germs: Men, women, and the microbe in American life'' (Harvard University Press, 1999

online

* Tomes, Nancy. "Moralizing the microbe: the germ theory and the moral construction of behavior in the late-nineteenth-century antituberculosis movement." in ''Morality and health'' (Routledge, 2013) pp. 271-294. * Tomes, Nancy J. "American attitudes toward the germ theory of disease: Phyllis Allen Richmond revisited." ''Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences'' 52.1 (1997): 17-50

online

* Winslow, Charles-Edward Amory. ''The Conquest of Epidemic Disease. A Chapter in the History of Ideas'' (1943

online

External links

John Horgan, "Germ Theory" (2023)

* Stephen T. Abedo

Supplemental Lecture (98/03/28 update), ''www.mansfield.ohio-state.edu'' * William C. Campbel

The Germ Theory Timeline

''germtheorytimeline.info''

''www.creatingtechnology.org'' {{Authority control Biology theories History of biology History of medicine > Microbiology