French Creoles on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The French Louisianians (), also known as Louisiana French, are

"Creoles"

, "KnowLA Encyclopedia of Louisiana". Retrieved October 19, 2011 Today, the most famous Louisiana French groups are the Alabama Creoles (including Alabama Cajans),

The Term "Creole" in Louisiana : An Introduction

, lameca.org. Retrieved December 5, 2013 The term Louisanese () was used as a demonym for Louisiana French people prior to the establishment of states in the

Adventurers led by

Adventurers led by

Mobile contained approximately 40% of all of Alabama's free black population. Mobile's free people of color were the Creoles. A people of diverse origins, the Creoles formed an elite with their own schools, churches, fire company, and social organizations. Many Creoles were the descendants of free blacks at the time of Mobile's capture by American forces, and who retained their freedoms by treaty and treated by the American government as a unique people. Other Creoles were blood relatives of white Mobilians including those of prominent families.

Mobile gained the nickname the "Athens of the South" as it became rich and prospered. European immigrants from continental Europe as well as those who had already established themselves in Northern cities flocked to Mobile. By 1860, Mobile boasted a population of 30,000.

In 1844, a Northern visitor described the diversity and beauty of Mobile:

All levels of Mobile's classes and society engaged in a frantic pursuit of pleasure. For those of the elite class, life seemed to be a swirl of balls, parties, and parades. Mobile abounded with private social clubs, gentlemen's clubs, militia units, and other organizations that sponsored balls. A January 8 ball to commemorate the

Mobile contained approximately 40% of all of Alabama's free black population. Mobile's free people of color were the Creoles. A people of diverse origins, the Creoles formed an elite with their own schools, churches, fire company, and social organizations. Many Creoles were the descendants of free blacks at the time of Mobile's capture by American forces, and who retained their freedoms by treaty and treated by the American government as a unique people. Other Creoles were blood relatives of white Mobilians including those of prominent families.

Mobile gained the nickname the "Athens of the South" as it became rich and prospered. European immigrants from continental Europe as well as those who had already established themselves in Northern cities flocked to Mobile. By 1860, Mobile boasted a population of 30,000.

In 1844, a Northern visitor described the diversity and beauty of Mobile:

All levels of Mobile's classes and society engaged in a frantic pursuit of pleasure. For those of the elite class, life seemed to be a swirl of balls, parties, and parades. Mobile abounded with private social clubs, gentlemen's clubs, militia units, and other organizations that sponsored balls. A January 8 ball to commemorate the

The Quapaw reached their historical territory, the area of the

The Quapaw reached their historical territory, the area of the

In 1679, French explorer

In 1679, French explorer

Through both the French and Spanish (late 18th century) regimes, parochial and colonial governments used the term Creole for ethnic French and Spanish people born in the

Through both the French and Spanish (late 18th century) regimes, parochial and colonial governments used the term Creole for ethnic French and Spanish people born in the

New France wished to make Native Americans subjects of the king and good Christians, but the distance from Metropolitan France and the sparseness of French settlement prevented this. In official

New France wished to make Native Americans subjects of the king and good Christians, but the distance from Metropolitan France and the sparseness of French settlement prevented this. In official

Inability to find labor was the most pressing issue in Louisiana. In 1717,

Inability to find labor was the most pressing issue in Louisiana. In 1717,

In 1765, during Spanish rule, several thousand

In 1765, during Spanish rule, several thousand

In the early 19th century, floods of Creole refugees fled

In the early 19th century, floods of Creole refugees fled

, ''In Motion: African American Migration Experience,'' New York Public Library. Retrieved May 7, 2008 The Saint-Domingue Creole specialized population raised Louisiana's level of culture and industry, and was one of the reasons why Louisiana was able to gain statehood so quickly. A quote from a Louisiana Creole who remarked on the rapid development of his homeland:

) A few years later, explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, Cavelier de la Salle charted the

A few years later, explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, Cavelier de la Salle charted the

In 2012, a Franco-fête Festival was held in Minneapolis. Similar events take place every year throughout the state of Minnesota. Since Minnesota shares a border with French-speaking areas of Canada, French exchanges remain common. In 2004, an estimated 35% of Minnesota's production was being exported to Francophone countries (Canada, France, Belgium and Switzerland).

Old Biloxi was completed on May 1, 1699

"Pierre Le Moyne, Sieur d'Iberville" (biography),

''Catholic Encyclopedia'', 1907, webpage:

Old Biloxi was completed on May 1, 1699

"Pierre Le Moyne, Sieur d'Iberville" (biography),

''Catholic Encyclopedia'', 1907, webpage:

CathEnc-7614b

gives dates: February 13, 1699, went to the mainland Biloxi, with fort completion May 1, 1699; sailed for France May 4. "Fort Maurepas", Mississippi Genealogy, 2002–2008, webpage:

under direction of French explorer

Louisiana State Museum, 2017; accessed May 30, 2017 The expedition journal reported: The best men were selected to remain at the fort, including detachments of soldiers to place with the Canadians (the French also had a colony in what is now Quebec and along the upper Mississippi River) and workmen, and sailors to serve on the gunboats. Altogether about 100 people were left at Fort Maurepas while Iberville sailed back to France on May 4, 1699. Those remaining included: * M. de Sauvolle de la Villantry, lieutenant of a company and naval ensign of the frigate ''Le Marin'', was left in command as governor. * Bienville, king's lieutenant of the marine guard of the frigate ''La Badine'' was next in command. * Le Vasseur de Boussouelle, a Canadian, was major. * De Bordenac was chaplain, and M. Care was surgeon. * Also: two captains, two cannoniers, four sailors, eighteen filibusters, ten mechanics, 6 masons, 13 Canadians, and 20 sub-officers and soldiers who comprised the garrison. Few of the colonists were experienced with agriculture, and the colony never became self-sustaining. The climate and soil were different than they were familiar with. On the return of d'Iberville to Old Biloxi in January 1700, he brought with him sixty Canadian immigrants and a large supply of provisions and stores. On this second voyage, he was instructed:

-->fort_maurepas.htm Mgenealogy-maurepas

de l'Épinay and de Bienville decided to make use of the harbor at

French colonization of the region began in earnest during the late 17th century by ''

French colonization of the region began in earnest during the late 17th century by '' Since its inception, Kaskaskia possessed a diverse population, a majority of whom were

Since its inception, Kaskaskia possessed a diverse population, a majority of whom were  In 1732, following a short-lived French trading post for buffalo hides,

In 1732, following a short-lived French trading post for buffalo hides,

On January 1, 1718, a trade monopoly was granted to

On January 1, 1718, a trade monopoly was granted to  The fort was to be the seat of government for the Illinois Country and help to control the

The fort was to be the seat of government for the Illinois Country and help to control the

The

The

In the 17th century, the French were the first modern Europeans to explore what became known as

In the 17th century, the French were the first modern Europeans to explore what became known as

The first European to visit what became Wisconsin was probably the French explorer

The first European to visit what became Wisconsin was probably the French explorer  The British gradually took over Wisconsin during the French and Indian War, taking control of Green Bay in 1761 and gaining control of all of Wisconsin in 1763. Like the French, the British were interested in little but the fur trade. One notable event in the fur trading industry in Wisconsin occurred in 1791, when two free African Americans set up a fur trading post among the Menominee at present day Marinette. The first permanent settlers, mostly

The British gradually took over Wisconsin during the French and Indian War, taking control of Green Bay in 1761 and gaining control of all of Wisconsin in 1763. Like the French, the British were interested in little but the fur trade. One notable event in the fur trading industry in Wisconsin occurred in 1791, when two free African Americans set up a fur trading post among the Menominee at present day Marinette. The first permanent settlers, mostly

French people

French people () are a nation primarily located in Western Europe that share a common Culture of France, French culture, History of France, history, and French language, language, identified with the country of France.

The French people, esp ...

native to the states

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

that were established out of French Louisiana

The term French Louisiana ( ; ) refers to two distinct regions:

* First, to Louisiana (New France), historic French Louisiana, comprising the massive, middle section of North America claimed by Early Modern France, France during the 17th and 18th ...

. They are commonly referred to as French Creoles ().Bernard, Shane K"Creoles"

, "KnowLA Encyclopedia of Louisiana". Retrieved October 19, 2011 Today, the most famous Louisiana French groups are the Alabama Creoles (including Alabama Cajans),

Louisiana Creoles

Louisiana Creoles (, , ) are a Louisiana French ethnic group descended from the inhabitants of colonial Louisiana during the periods of French and Spanish rule, before it became a part of the United States. They share cultural ties such as t ...

(including Louisiana Cajuns

The Cajuns (; French: ''les Cadjins'' or ''les Cadiens'' ), also known as Louisiana ''Acadians'' (French: ''les Acadiens''), are a Louisiana French ethnicity mainly found in the US state of Louisiana and surrounding Gulf Coast states.

While ...

), and the Missouri French

Missouri French () or Illinois Country French () also known as , and nicknamed " Paw-Paw French" often by individuals outside the community but not exclusively, is a variety of the French language spoken in the upper Mississippi River Valley in ...

(Illinois Country Creoles).

Etymology

The term ''Créole'' was originally used by French settlers to distinguish people born inFrench Louisiana

The term French Louisiana ( ; ) refers to two distinct regions:

* First, to Louisiana (New France), historic French Louisiana, comprising the massive, middle section of North America claimed by Early Modern France, France during the 17th and 18th ...

from those born elsewhere, thus drawing a distinction between Old-World Europeans and Africans from their Creole descendants born in the Viceroyalty of New France

New France (, ) was the territory colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Kingdom of Great Br ...

.Kathe ManaganThe Term "Creole" in Louisiana : An Introduction

, lameca.org. Retrieved December 5, 2013 The term Louisanese () was used as a demonym for Louisiana French people prior to the establishment of states in the

Louisiana Territory

The Territory of Louisiana or Louisiana Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1805, until June 4, 1812, when it was renamed the Missouri Territory. The territory was formed out of t ...

, but the term fell into disuse after the Orleans Territory

The Territory of Orleans or Orleans Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from October 1, 1804, until April 30, 1812, when it was admitted to the Union as the State of Louisiana.

History

In 180 ...

gained admission into the American Union as the State of Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25th i ...

:

"The elegant olive-browned Louisianese- the rosy-cheeked maiden from '' La belle riviere'' (La Belle Rivière is the native Louisiana French name for Ohio)..."

Louisiana French Language

The Louisiana French speak similar dialects of French, the major varieties being Lower Louisiana French, Upper Louisiana French, andLouisiana Creole

Louisiana Creole is a French-based creole language spoken by fewer than 10,000 people, mostly in the U.S. state of Louisiana. Also known as Kouri-Vini, it is spoken today by people who may racially identify as white, black, mixed, and Native ...

.

Alabama Creoles

Adventurers led by

Adventurers led by Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville

Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville (16 July 1661 – 9 July 1706) or Sieur d'Iberville was a French soldier, explorer, colonial administrator, and trader. He is noted for founding the colony of Louisiana in New France. He was born in Montreal to French ...

moved from Fort Maurepas

Fort Maurepas, later known as Old Biloxi,

"Pierre Le Moyne, Sieur d'Iberville" (biography),

''Catholic Encyclopedia'', 1907, webpage:

gives dates: 13 Feb. 1699, went to the mainland Biloxi,

with fort completion May 1, 1699; sailed f ...

in Biloxi

Biloxi ( ; ) is a city in Harrison County, Mississippi, United States. It lies on the Gulf Coast of the United States, Gulf Coast in southern Mississippi, bordering the city of Gulfport, Mississippi, Gulfport to its west. The adjacent cities ar ...

, Mississippi to a wooded bluff on the west bank of the Mobile River

The Mobile River is located in southern Alabama in the United States. Formed out of the confluence of the Tombigbee and Alabama rivers, the approximately river drains an area of of Alabama, with a watershed extending into Mississippi, Georg ...

in early 1702, where they founded Mobile, which they named after the Maubilian Nation. The outpost was populated by French soldiers, French-Canadian trappers and fur traders, and a few merchants and artisans accompanied by their families. The French had easy access to the Indigenous fur trade, and furs were the primary economic resource of Mobile. Along with fur, some settlers also raised cattle as well as produced ships' timbers and naval stores.

Indigenous nations gathered annually at Mobile to be wined, dined, and showered with presents by the French. About 2,000 Indigenous descended on Mobile for as long as two weeks. Because of the close and friendly relationship between colonial French and Indigenous peoples, French colonists learned the Indigenous Lingua franca

A lingua franca (; ; for plurals see ), also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, link language or language of wider communication (LWC), is a Natural language, language systematically used to make co ...

of the area, the Mobilian Jargon

Mobilian Jargon (also Mobilian trade language, Mobilian Trade Jargon, Chickasaw–Choctaw trade language, Yamá) was a pidgin used as a lingua franca among Native American groups living along the north coast of the Gulf of Mexico around the time ...

, and intermarried with Indigenous women.

Mobile was a melting pot of different peoples, and included continental Frenchmen, French-Canadians, and various Indigenous people mingled together in Mobile. The differences between continental Frenchmen and French-Canadians were so great that serious disputes occurred between the two groups.

The French also established slavery in 1721. Slaves infused elements of African and West Indian

A West Indian is a native or inhabitant of the West Indies (the Antilles and the Lucayan Archipelago). According to the ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED''), the term ''West Indian'' in 1597 described the indigenous inhabitants of the West In ...

French Creole culture into Mobile, as many of the slaves who came to Mobile worked in the French West Indies

The French West Indies or French Antilles (, ; ) are the parts of France located in the Antilles islands of the Caribbean:

* The two overseas departments of:

** Guadeloupe, including the islands of Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Les Saintes, Ma ...

. In 1724, the ''Code Noir

The (, ''Black code'') was a decree passed by King Louis XIV, Louis XIV of France in 1685 defining the conditions of Slavery in France, slavery in the French colonial empire and served as the code for slavery conduct in the French colonies ...

'', a slave code based on Roman laws

This is a partial list of Roman laws. A Roman law () is usually named for the sponsoring legislator and designated by the adjectival form of his ''gens'' name ('' nomen gentilicum''), in the feminine form because the noun ''lex'' (plural ''leges'' ...

, was instituted in French colonies which allowed slaves certain legal and religious rights not found in either British colonies or the United States. The ''Code Noir

The (, ''Black code'') was a decree passed by King Louis XIV, Louis XIV of France in 1685 defining the conditions of Slavery in France, slavery in the French colonial empire and served as the code for slavery conduct in the French colonies ...

'' based on Roman laws

This is a partial list of Roman laws. A Roman law () is usually named for the sponsoring legislator and designated by the adjectival form of his ''gens'' name ('' nomen gentilicum''), in the feminine form because the noun ''lex'' (plural ''leges'' ...

also conferred '' affranchis'' (ex-slaves) full citizenship and gave complete civil equality with other French subjects.

By the mid-18th century, Mobile was populated by West Indian French Creoles, European Frenchmen, French-Canadians, Africans, and Indigenous people. This diverse group was united by Roman Catholicism, the exclusive religion of the colony. The town's inhabitants included 50 troops, a mixed group of approximately 400 civilians which included merchants, laborers, fur traders, artisans, and slaves. This mixed diverse group and its descendants are called Creoles.

Mobile Alabama, the Athens of the South

Mobile contained approximately 40% of all of Alabama's free black population. Mobile's free people of color were the Creoles. A people of diverse origins, the Creoles formed an elite with their own schools, churches, fire company, and social organizations. Many Creoles were the descendants of free blacks at the time of Mobile's capture by American forces, and who retained their freedoms by treaty and treated by the American government as a unique people. Other Creoles were blood relatives of white Mobilians including those of prominent families.

Mobile gained the nickname the "Athens of the South" as it became rich and prospered. European immigrants from continental Europe as well as those who had already established themselves in Northern cities flocked to Mobile. By 1860, Mobile boasted a population of 30,000.

In 1844, a Northern visitor described the diversity and beauty of Mobile:

All levels of Mobile's classes and society engaged in a frantic pursuit of pleasure. For those of the elite class, life seemed to be a swirl of balls, parties, and parades. Mobile abounded with private social clubs, gentlemen's clubs, militia units, and other organizations that sponsored balls. A January 8 ball to commemorate the

Mobile contained approximately 40% of all of Alabama's free black population. Mobile's free people of color were the Creoles. A people of diverse origins, the Creoles formed an elite with their own schools, churches, fire company, and social organizations. Many Creoles were the descendants of free blacks at the time of Mobile's capture by American forces, and who retained their freedoms by treaty and treated by the American government as a unique people. Other Creoles were blood relatives of white Mobilians including those of prominent families.

Mobile gained the nickname the "Athens of the South" as it became rich and prospered. European immigrants from continental Europe as well as those who had already established themselves in Northern cities flocked to Mobile. By 1860, Mobile boasted a population of 30,000.

In 1844, a Northern visitor described the diversity and beauty of Mobile:

All levels of Mobile's classes and society engaged in a frantic pursuit of pleasure. For those of the elite class, life seemed to be a swirl of balls, parties, and parades. Mobile abounded with private social clubs, gentlemen's clubs, militia units, and other organizations that sponsored balls. A January 8 ball to commemorate the Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8, 1815, between the British Army under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham and the United States Army under Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson, roughly 5 miles (8 km) southeast of the Frenc ...

was a great favorite. Cotillion balls staged by private clubs were also popular.

All Mobilians regardless of their origin enjoyed horse races. The Mobile Jockey Club offered Mobilians the ability to place a bet on their favorite steeds. Cockfighting also became popular during the 1840s and 1850s.

Like New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

, Mobile prided itself on its vibrant theater arts. Blacks attended Mobile's theaters, and Mobilians were treated to various plays and works by Shakespeare, contemporary comedies, and farce shows.

Mardi Gras

Mardi Gras (, ; also known as Shrove Tuesday) is the final day of Carnival (also known as Shrovetide or Fastelavn); it thus falls on the day before the beginning of Lent on Ash Wednesday. is French for "Fat Tuesday", referring to it being ...

became of great importance as mystic societies began putting on masked parades with bands, floats, and horses after members attended grand balls. Elaborate floats depicted images of the ancient world. In 1841 Cowbellion's floats of Greek gods were described as "one of the most gorgeous and unique spectacles that was ever beheld in modern times."

The Catholic community of primarily French Creole descent remained numerous and influential. In 1825, the Catholic community began the 15-year construction of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception. For most of the antebellum era, friction between Protestants and Catholics was practically non-existent.

The Creoles of Mobile built a Catholic school run by and for Creoles. Mobilians supported several literary societies, numerous book stores, and number of book and music publishers.

Arkansas people of mixed French/Indigenous ancestry

The Quapaw reached their historical territory, the area of the

The Quapaw reached their historical territory, the area of the confluence

In geography, a confluence (also ''conflux'') occurs where two or more watercourses join to form a single channel (geography), channel. A confluence can occur in several configurations: at the point where a tributary joins a larger river (main ...

of the Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the West South Central region of the Southern United States. It borders Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, and Oklahoma ...

and Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

rivers, at least by the mid-17th century. The Illinois and other Algonquian-speaking peoples to the northeast referred to these people as the ' or ', referring to geography and meaning "land of the downriver people". As French explorers Jacques Marquette

Jacques Marquette, Society of Jesus, S.J. (; June 1, 1637 – May 18, 1675), sometimes known as Père Marquette or James Marquette, was a French Society of Jesus, Jesuit missionary who founded Michigan's first European settlement, Sault Ste. M ...

and Louis Jolliet

Louis Jolliet (; September 21, 1645after May 1700) was a French-Canadian explorer known for his discoveries in North America. In 1673, Jolliet and Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit Catholic priest and missionary, were the first non-Natives to explore ...

encountered and interacted with the Illinois before they did the Quapaw, they adopted this exonym

An endonym (also known as autonym ) is a common, name for a group of people, individual person, geographical place, language, or dialect, meaning that it is used inside a particular group or linguistic community to identify or designate them ...

for the more westerly people. In their language, they referred to them as ''Arcansas''. English-speaking settlers who arrived later in the region adopted the name used by the French, and adapted it to English spelling conventions.

'' Écore Fabre'' (Fabre's Bluff) was started as a trading post by the Frenchman Fabre and was one of the first European settlements in south-central Arkansas. While the area was nominally ruled by the Spanish from 1763 to 1789, following French defeat in the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

, they did not have many colonists in the area and did not interfere with the French. The United States acquired the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase () was the acquisition of the Louisiana (New France), territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. This consisted of most of the land in the Mississippi River#Watershed, Mississipp ...

in 1803, which stimulated migration of English-speaking settlers to this area. They renamed ''Écore Fabre'' as Camden.

During years of colonial rule of New France

New France (, ) was the territory colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Kingdom of Great Br ...

, many of the ethnic French fur traders and ''voyageurs

Voyageurs (; ) were 18th- and 19th-century French and later French Canadians and others who transported furs by canoe at the peak of the North American fur trade. The emblematic meaning of the term applies to places (New France, including the ...

'' had an amicable relationship with the Quapaw, as they did with many other trading tribes. Many Quapaw women and French men married and had families together, creating a ''métis'' ( mixed French and Indigenous) population. Pine Bluff, Arkansas

Pine Bluff, officially the City of Pine Bluff, is the List of municipalities in Arkansas, tenth-most populous city in the U.S. state of Arkansas and the county seat of Jefferson County, Arkansas, Jefferson County. The population of the city wa ...

, for example, was founded by Joseph Bonne, a man of Quapaw-French ''métis'' ancestry.

Indiana French

In 1679, French explorer

In 1679, French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle (; November 22, 1643 – March 19, 1687), was a 17th-century French explorer and North American fur trade, fur trader in North America. He explored the Great Lakes region of the United States and Canada ...

was the first European to cross into Indiana after reaching present-day South Bend

South Bend is a city in St. Joseph County, Indiana, United States, and its county seat. It lies along the St. Joseph River (Lake Michigan), St. Joseph River near its southernmost bend, from which it derives its name. It is the List of cities in ...

at the St. Joseph River. He returned the following year to learn about the region. French-Canadian fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal ecosystem, boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals h ...

rs soon arrived, bringing blankets, jewelry, tools, whiskey and weapons to trade for skins with the Native Americans.

By 1702, Sieur Juchereau established the first trading post near Vincennes

Vincennes (; ) is a commune in the Val-de-Marne department in the eastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the centre of Paris. Vincennes is famous for its castle: the Château de Vincennes. It is next to but does not include the ...

. In 1715, Sieur de Vincennes built Fort Miami at Kekionga

Kekionga (, meaning "blackberry bush"), also known as KiskakonCharles R. Poinsatte, ''Fort Wayne During the Canal Era 1828-1855,'' Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau, 1969, p. 1 or Pacan's Village, was the capital of the Miami tribe. It wa ...

, now Fort Wayne

Fort Wayne is a city in Allen County, Indiana, United States, and its county seat. Located in northeastern Indiana, the city is west of the Ohio border and south of the Michigan border. The city's population was 263,886 at the 2020 United S ...

. In 1717, another Canadian, Picote de Beletre Picote may refer to:

* Picote (Miranda do Douro), Portugal, a civil parish

* Picote Dam, Miranda do Douro

* Nebbiolo, an Italian wine grape variety also known as Picote

See also

* François-Marie Picoté de Belestre (1716–1793), colonial sol ...

, built Fort Ouiatenon

Fort Ouiatenon, built in 1717, was the first fortified European settlement in what is now Indiana, United States. It was a palisade stockade with log blockhouse used as a French trading post on the Wabash River located approximately three miles ...

on the Wabash River

The Wabash River () is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed May 13, 2011 river that drains most of the state of Indiana, and a significant part of Illinois, in the United ...

, to try to control Native American trade routes from Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( ) is the fourth-largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and also has the shortest avera ...

to the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

.

In 1732, Sieur de Vincennes built a second fur trading post at Vincennes. French settlers, who had left the earlier post because of hostilities, returned in larger numbers. In a period of a few years, British colonists arrived from the East and contended against the French for control of the lucrative fur trade. Fighting between the French and British colonists occurred throughout the 1750s as a result.

The Native American tribes of Indiana sided with New France

New France (, ) was the territory colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Kingdom of Great Br ...

during the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

(also known as the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

). With Britain's victory in 1763, the French were forced to cede to the British crown all their lands in North America east of the Mississippi River and north and west of the colonies

A colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule, which rules the territory and its indigenous peoples separated from the foreign rulers, the colonizer, and their '' metropole'' (or "mother country"). This separated rule was often or ...

.

Louisiana Creoles

Lower Louisiana

New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

as opposed to Europe. Parisian French was the predominant language among colonists in early New Orleans.

Later the regional French evolved to contain local phrases and slang terms. The French Creoles spoke what became known as Colonial French

Louisiana French (Louisiana French: ''français louisianais''; ) includes the dialects and varieties of the French language spoken traditionally by French Louisianians in colonial Lower Louisiana. As of today Louisiana French is primarily use ...

. Because of isolation, the language in the colony developed differently from that in France. It was spoken by the ethnic French and Spanish and their Creole descendants.

The commonly accepted definition of Louisiana Creole today is a person descended from ancestors in Louisiana before the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase () was the acquisition of the Louisiana (New France), territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. This consisted of most of the land in the Mississippi River#Watershed, Mississipp ...

by the United States in 1803. An estimated 7,000 European immigrants settled in Louisiana during the 18th century, one percent of the number of European colonists in the Thirteen Colonies along the Atlantic coast. Louisiana attracted considerably fewer French colonists than did its West Indian colonies.

After the crossing of the Atlantic Ocean, which lasted more than two months, the colonists had numerous challenges ahead of them in the Louisiana frontier. Their living conditions were difficult: uprooted, they had to face a new, often hostile, environment, with difficult climate and tropical diseases. Many of these immigrants died during the maritime crossing or soon after their arrival.

Hurricane

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system with a low-pressure area, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Depending on its ...

s, unknown in France, periodically struck the coast, destroying whole villages. The Mississippi Delta

The Mississippi Delta, also known as the Yazoo–Mississippi Delta, or simply the Delta, is the distinctive northwest section of the U.S. state of Mississippi (and portions of Arkansas and Louisiana) that lies between the Mississippi and Yazo ...

was plagued with periodic yellow fever epidemics. Europeans also brought the Eurasian diseases of malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

and cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

, which flourished along with mosquitoes and poor sanitation. These conditions slowed colonization. Moreover, French villages and forts were not always sufficient to protect from enemy offensives. Attacks by Native Americans represented a real threat to the groups of isolated colonists.

The Natchez Natchez may refer to:

Places

* Natchez, Alabama, United States

* Natchez, Indiana, United States

* Natchez, Louisiana, United States

* Natchez, Mississippi, a city in southwestern Mississippi, United States

** Natchez slave market, Mississippi

* ...

massacred 250 colonists in Lower Louisiana in retaliation for encroachment by French settlers. The Natchez warriors took Fort Rosalie

Fort Rosalie was built by the French in 1716 within the territory of the Natchez Native Americans as part of the French colonial empire in the present-day city of Natchez, Mississippi.

Early history

As part of the peace terms that ended t ...

(now Natchez, Mississippi

Natchez ( ) is the only city in and the county seat of Adams County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 14,520 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Located on the Mississippi River across from Vidalia, Louisiana, Natchez was ...

) by surprise, killing many settlers. During the next two years, the French attacked the Natchez in return, causing them to flee or, when captured, be deported

Deportation is the expulsion of a person or group of people by a state from its Sovereignty, sovereign territory. The actual definition changes depending on the place and context, and it also changes over time. A person who has been deported or ...

as slaves to their Caribbean colony of Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colonization of the Americas, French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1803. The name derives from the Spanish main city on the isl ...

(later Haiti).

In the colonial period of French and Spanish rule, men tended to marry later after becoming financially established. French settlers frequently took Native American women as their wives (see Marriage 'à la façon du pays'

Marriage, also called matrimony or wedlock, is a culturally and often legally recognised union between people called spouses. It establishes rights and obligations between them, as well as between them and their children (if any), and b ...

), and as slaves began to be imported into the colony, settlers also took African wives. Intermarriage between the different groups of Louisiana created a large multiracial Creole population.

Engagés and Casquette Girls

Aside from French government representatives and soldiers, colonists included mostly young men who were recruited in French ports or in Paris. Some labored as ''engagé

The ''engagé'' system of indentured servitude existed in New France, the U.S. state of Louisiana, and the French West Indies from the 18th and 19th centuries.

Engagés in Canada

From the 18th century, an engagé (; also spelled '' engagee' ...

s'' (indentured servants), i.e. "temporary semi-slaves"; they were required to remain in Louisiana for a length of time, fixed by the contract of service, to pay back the cost of passage and board. Engagés in Louisiana generally worked for seven years, and their masters provided them housing, food, and clothing. They were often housed in barns and performed hard labor.

Starting in 1698, French merchants were obliged to transport a number of men to the colonies in proportion to the ships' tonnage. Some of the men brought over were engaged on three-year indenture contracts under which the contract-holder would be responsible for their "vital needs" as well as provide a salary at the end of the contract term. Under John Law's Company

John Law's Company, founded in 1717 by Scottish economist and financier John Law, was a joint-stock company that occupies a unique place in French and European monetary history, as it was for a brief moment granted the entire revenue-raising ca ...

, efforts to increase the use of ''engagés'' in the colony were made, notably including German settlers whose contracts were absolved when the company went bankrupt in 1731.

During this time, to increase the colonial population, the government also recruited young Frenchwomen, known as '' filles à la cassette'' (in English, ''casket girls'', referring to the casket or case of belongings they brought with them) to go to the colony to be wed to colonial soldiers. The king financed dowries for each girl. (This practice was similar to events in 17th-century Quebec: about 800 ''filles du roi

The King's Daughters ( , or in the spelling of the era) were the approximately 800 young French women who immigrated to New France between 1663 and 1673 as part of a program sponsored by King Louis XIV. The program was designed to boost New F ...

'' (daughters of the king) were recruited to immigrate to New France

New France (, ) was the territory colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Kingdom of Great Br ...

under the monetary sponsorship of Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

.)

In addition, French authorities deported some female criminals to the colony. For example, in 1721, the ship ''La Baleine'' brought close to 90 women of childbearing age from the prison of La Salpêtrière

LA most frequently refers to Los Angeles, the second most populous city in the United States of America.

La, LA, or L.A. may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

* La (musical note), or A, the sixth note

*"L.A.", a song by Elliott Smi ...

in Paris to Louisiana. Most of the women quickly found husbands among the male residents of the colony. These women, many of whom were most likely prostitutes or felons, were known as ''The Baleine Brides''. Such events inspired ''Manon Lescaut

''The Story of the Chevalier des Grieux and Manon Lescaut'' ( ) is a novel by Antoine François Prévost. It tells a tragic love story about a nobleman (known only as the Chevalier des Grieux) and a common woman (Manon Lescaut). Their decisio ...

'' (1731), a novel written by the Abbé Prévost

Antoine François Prévost d'Exiles ( , , ; 1 April 169725 November 1763), usually known simply as the Abbé Prévost, was a French priest, author, and novelist.

Life and works

He was born at Hesdin, Artois, and first appears with the full na ...

, which was later adapted as an opera in the 19th century.

Historian Joan Martin maintains that there is little documentation that casket girls (considered among the ancestors of French Creoles) were transported to Louisiana. (The Ursuline order of nuns, who were said to chaperone the girls until they married, have denied the casket girl myth as well.) Martin suggests this account was mythical. The system of plaçage

Plaçage was a recognized extralegal system in French slave colonies of North America (including the Caribbean) by which ethnic European men entered into civil unions with non-Europeans of African, Native American and mixed-race descent. The term ...

that continued into the 19th century resulted in many young white men having women of color as partners and mothers of their children, often before or even after their marriages to white women. French Louisiana also included communities of Swiss and German settlers; however, royal authorities did not refer to "Louisianans" but described the colonial population as "French" citizens.

People of mixed French and Indigenous ancestry in Louisiana

New France wished to make Native Americans subjects of the king and good Christians, but the distance from Metropolitan France and the sparseness of French settlement prevented this. In official

New France wished to make Native Americans subjects of the king and good Christians, but the distance from Metropolitan France and the sparseness of French settlement prevented this. In official rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse ( trivium) along with grammar and logic/ dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or w ...

, the Native Americans were regarded as subjects of the Viceroyalty of New France

New France (, ) was the territory colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Kingdom of Great Br ...

, but in reality, they were largely autonomous due to their numerical superiority. The local authorities of New France (governors, officers) did not have the human resources to establish French law and customs, and instead often compromised with the Indigenous people.

Indigenous nations offered essential support for the French: they ensured the survival of the New France's colonists, participated with them in the fur trade, and acted as guides in expeditions. The French alliance with Indigenous nations also provided mutual protection from hostile non-allied tribes and incursions on French and Indigenous peoples' land from enemy European powers

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power ...

. The French and Indigenous alliance proved invaluable during the later French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

against the New England colonies

The New England Colonies of British America included Connecticut Colony, the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Massachusetts Bay Colony, Plymouth Colony, and the Province of New Hampshire, as well as a few smaller short-lived c ...

in 1753.

The French & Indigenous peoples influenced each other in many fields: the French settlers learned the languages of the natives, such as Mobilian Jargon

Mobilian Jargon (also Mobilian trade language, Mobilian Trade Jargon, Chickasaw–Choctaw trade language, Yamá) was a pidgin used as a lingua franca among Native American groups living along the north coast of the Gulf of Mexico around the time ...

, a Choctaw-based Creole language that served as a trade language in use among the French and various Indigenous nations in the region. Indigenous people bought European goods (fabric, alcohol, firearms, etc.), learned French, and sometimes adopted their religion.

The ''coureurs des bois'' and soldiers borrowed canoes and moccasins. Many of them ate native food such as wild rice and various meats, like bear and dog. The colonists were often dependent on the Native Americans for food. Creole cuisine

Creole cuisine (; ; ) is a cuisine style born in colonial times, from the fusion between African, European and pre-Columbian traditions. ''Creole'' is a term that refers to those of European origin who were born in the New World and have adap ...

is the heir of these mutual influences: thus, ''sagamité'', for example, is a mix of corn pulp, bear fat and bacon. Today jambalaya

Jambalaya ( , ) is a savory rice dish that developed in the U.S. state of Louisiana fusing together African, Spanish, and French influences, consisting mainly of meat and/or seafood, and vegetables mixed with rice and spices. West Africans a ...

, a word of Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, ...

origin, refers to a multitude of recipes calling for meat and rice, all very spicy. Sometimes shamans

Shamanism is a spiritual practice that involves a practitioner (shaman) interacting with the Spirit (supernatural entity), spirit world through Altered state of consciousness, altered states of consciousness, such as trance. The goal of th ...

succeeded in curing the colonists thanks to traditional remedies, such as the application of fir tree gum on wounds and Royal Fern on rattlesnake bites.

Many French colonists both admired and feared the military power of the Native Americans, though some governors from France scorned their culture and wanted to keep racial purity between the whites and Indigenous people. In 1735, interracial marriages without the approval of the authorities were prohibited in Louisiana. However, by the 1750s in New France, the idea of the Native Americans became one of the "Noble Savage," that Indigenous people were spiritually pure and played an important role in the natural purity of the New World. Native Americans did marry French settlers, with Indigenous women being consistently considered as good wives to foster trade and help create offspring. Their intermarriage created a large ''métis'' ( mixed French and Indigenous) population in New France.

In spite of some disagreements (some Indigenous people killed farmers' pigs, which devastated corn fields), and sometimes violent confrontations (Fox Wars

The Fox Wars were two conflicts between the French and the Meskwaki (historically Fox) people who lived in the Great Lakes region (particularly near Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit) from 1712 to 1733.In their book ''The Fox Wars'', Edmunds and Pe ...

, Natchez uprisings, and expeditions against the Chicachas), the relationship with the Native Americans was relatively good in Louisiana. French imperialism was expressed through some wars and the slavery of some Native Americans. But most of the time, the relationship was based on dialogue and negotiation.

Africans in Louisiana

Inability to find labor was the most pressing issue in Louisiana. In 1717,

Inability to find labor was the most pressing issue in Louisiana. In 1717, John Law

John Law may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* John Law (artist) (born 1958), American artist

* John Law (comics), comic-book character created by Will Eisner

* John Law (film director), Hong Kong film director

* John Law (musician) (born 1961) ...

, the French Comptroller General of Finances, decided to import African slaves into Louisiana. His objective was to develop the plantation economy of Lower Louisiana. John Law's Company

John Law's Company, founded in 1717 by Scottish economist and financier John Law, was a joint-stock company that occupies a unique place in French and European monetary history, as it was for a brief moment granted the entire revenue-raising ca ...

held a monopoly over the slave trade Slave trade may refer to:

* History of slavery - overview of slavery

It may also refer to slave trades in specific countries, areas:

* Al-Andalus slave trade

* Atlantic slave trade

** Brazilian slave trade

** Bristol slave trade

** Danish sl ...

in the area. The colonists turned to sub-Saharan African slaves to make their investments in Louisiana profitable. In the late 1710s the transatlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of Slavery in Africa, enslaved African people to the Americas. European slave ships regularly used the triangular trade route and its Middle Pass ...

imported slaves into the colony. This led to the biggest shipment in 1716 where several trading ships appeared with slaves as cargo to the local residents in a one-year span.

Between 1723 and 1769, most slaves imported to Louisiana were from modern day Senegal, Mali and Congo. A large number of the imported slaves from the Senegambia region were members of the Wolof

Wolof or Wollof may refer to:

* Wolof people, an ethnic group found in Senegal, Gambia, and Mauritania

* Wolof language, a language spoken in Senegal, Gambia, and Mauritania

* The Wolof or Jolof Empire, a medieval West African successor of the Mal ...

and Bambara ethnic groups. During the Spanish control of Louisiana, between 1770 and 1803, most of the slaves still came from the Congo and the Senegambia region but they also imported more slaves from modern-day Benin. Other ethnic groups imported during this period included members of the Nago people, a Yoruba subgroup.

In Louisiana, the term ''Bambara'' was used as a generic term for African slaves. European traders used ''Bambara'' as a term for defining vaguely a region of ethnic origin. Muslim traders and interpreters often used ''Bambara'' to indicate Non-Muslim captives. Slave traders would sometimes identify their slaves as ''Bambara'' in hopes of securing a higher price, as Bambara slaves were sometimes characterized as being more passive. Further confusing the name's indication of ethnic, linguistic, religious, or other implications, the concurrent Bambara Empire

Bambara or Bambarra may refer to:

* Bambara people, an ethnic group, primarily in Mali

** Bambara language, their language, a Manding language

** Bamana Empire, a state that flourished in present-day Mali (1640s–1861)

* ''Bambara'' (beetle), a g ...

had notoriety for its practice of slave-capturing wherein Bambara soldiers would raid neighbors and capture the young men of other ethnic groups, forcibly assimilate them, and turn them into slave soldiers known as ''Ton''. The Bambara Empire depended on war-captives to replenish and increase its numbers; many of the people who called themselves ''Bambara'' were indeed not ethnic Bambara.

Africans contributed to the creolization of Louisiana society. They brought okra

Okra (, ), ''Abelmoschus esculentus'', known in some English-speaking countries as lady's fingers, is a flowering plant in the Malvaceae, mallow family native to East Africa. Cultivated in tropical, subtropical, and warm temperate regions aro ...

from Africa, a plant common in the preparation of gumbo

Gumbo () is a stew that is popular among the U.S. Gulf Coast community, the New Orleans stew variation being the official state cuisine of the U.S. state of Louisiana. Gumbo consists primarily of a strongly flavored stock, meat or shellfis ...

. While the ''Code Noir

The (, ''Black code'') was a decree passed by King Louis XIV, Louis XIV of France in 1685 defining the conditions of Slavery in France, slavery in the French colonial empire and served as the code for slavery conduct in the French colonies ...

'' required that the slaves receive a Christian education, many practiced animism

Animism (from meaning 'breath, spirit, life') is the belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. Animism perceives all things—animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather systems, human handiwork, and in ...

and often combined elements of the two faiths. The ''Code Noir'' also conferred '' affranchis'' (ex-slaves) full citizenship and gave complete civil equality with other French subjects.

Louisiana slave society generated its own distinct Afro-Creole culture that was present in religious beliefs and the Louisiana Creole

Louisiana Creole is a French-based creole language spoken by fewer than 10,000 people, mostly in the U.S. state of Louisiana. Also known as Kouri-Vini, it is spoken today by people who may racially identify as white, black, mixed, and Native ...

language. The slaves brought with them their cultural practices, languages, and religious beliefs rooted in spirit and ancestor worship

The veneration of the dead, including one's ancestors, is based on love and respect for the deceased. In some cultures, it is related to beliefs that the dead have a continued existence, and may possess the ability to influence the fortune of t ...

, as well as Roman Catholic Christianity—all of which were key elements of Louisiana Voodoo

Louisiana Voodoo, also known as New Orleans Voodoo, was an African diasporic religion that existed in Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to ...

. In addition, in the early nineteenth century, many Saint-Domingue Creoles

Saint-Domingue Creoles (, ) or simply Creoles, were the people who lived in the French colony of Saint-Domingue prior to the Haitian Revolution.

These Creoles formed an ethnic group native to Saint-Domingue and were all born in Saint-Domingue. Th ...

also settled in Louisiana, both free people of color and slaves, following the Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution ( or ; ) was a successful insurrection by slave revolt, self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolution was the only known Slave rebellion, slave up ...

, contributing to the Voodoo

Voodoo may refer to:

Religions

* West African Vodún, a religion practiced by Gbe-speaking ethnic groups

* African diaspora religions, a list of related religions sometimes called Vodou/Voodoo

** Candomblé Jejé, also known as Brazilian Vodu ...

tradition of the state. During the American period (1804–1820), almost half of the slaves came from the Congo.

Cajuns in Louisiana

Acadians

The Acadians (; , ) are an ethnic group descended from the French colonial empire, French who settled in the New France colony of Acadia during the 17th and 18th centuries. Today, most descendants of Acadians live in either the Northern Americ ...

from the French colony of Acadia

Acadia (; ) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the The Maritimes, Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. The population of Acadia included the various ...

(now Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island) made their way to Louisiana after having been expelled from Acadia by British authorities after the French and Indian War. They settled chiefly in the southwestern Louisiana region now called Acadiana

Acadiana (; French language, French and Cajun French language, Louisiana French: ''L'Acadiane'' or ''Acadiane''), also known as Cajun Country (Cajun French language, Louisiana French: ''Pays des Cadiens''), is the official name given to the ...

. The governor Luis de Unzaga y Amézaga

Luis de Unzaga y Amézaga (1717–1793), also known as Louis Unzaga y Amezéga le Conciliateur, Luigi de Unzaga Panizza and Lewis de Onzaga, was governor of Spanish Louisiana from late 1769 to mid-1777, as well as a Captain General of Venezuela ...

, eager to gain more settlers, welcomed the Acadians, who became the ancestors of Louisiana's Cajun

The Cajuns (; French: ''les Cadjins'' or ''les Cadiens'' ), also known as Louisiana ''Acadians'' (French: ''les Acadiens''), are a Louisiana French ethnicity mainly found in the US state of Louisiana and surrounding Gulf Coast states.

Whi ...

s.

=Americanization of the Cajun Country

= When the United States of America began assimilating and Americanizing the parishes of the Cajun Country between the 1950s and 1970s, they imposed segregation and reorganized the inhabitants of the Cajun Country to identify racially as either "white" Cajuns or "black" Creoles. As the younger generations were made to abandon speaking French and French customs, the White or mixed Indigenous and Cajun people assimilated into theAnglo-American

Anglo-American can refer to:

* the Anglosphere (the Anglo-American world)

* Anglo-American, something of, from, or related to Anglo-America

** the Anglo-Americans demographic group in Anglo-America

* Anglo American plc

Anglo American plc is a ...

host culture, and the Black Cajuns assimilated into the African American culture.

Cajuns looked to the Civil Rights Movement and other Black liberation and empowerment movements as a guide to fostering Louisiana's French cultural renaissance. A Cajun student protester in 1968 declared "We're slaves to a system. Throw away the shackles... and be free with your brother."

Refugees from Saint-Domingue in Louisiana

In the early 19th century, floods of Creole refugees fled

In the early 19th century, floods of Creole refugees fled Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colonization of the Americas, French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1803. The name derives from the Spanish main city on the isl ...

and poured into New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

, nearly tripling the city's population. Indeed, more than half of the refugee population of Saint-Domingue settled in Louisiana. Thousands of refugees, both white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wa ...

and Creole of color, arrived in New Orleans, sometimes bringing slaves

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

with them. While Governor Claiborne and other Anglo-American officials wanted to keep out additional free black men, Louisiana Creoles wanted to increase the French-speaking Creole population. As more refugees were allowed in Louisiana, those who had first gone to Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

had also arrived. Officials in Cuba deported many of these refugees in retaliation for Bonapartist

Bonapartism () is the political ideology supervening from Napoleon Bonaparte and his followers and successors. The term was used in the narrow sense to refer to people who hoped to restore the House of Bonaparte and its style of government. In ...

schemes in Spain.

Nearly 90 percent of early 19th century immigrants to the territory settled in New Orleans. The 1809 deportation from Cuba brought 2,731 whites, 3,102 Creoles of color and 3,226 slaves, which, in total, doubled the city's population. The city became 63 percent black in population, a greater proportion than Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the List of municipalities in South Carolina, most populous city in the U.S. state of South Carolina. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint of South Carolina's coastline on Charleston Harbor, an inlet of the Atla ...

's 53 percent."Haitian Immigration: 18th & 19th Centuries", ''In Motion: African American Migration Experience,'' New York Public Library. Retrieved May 7, 2008 The Saint-Domingue Creole specialized population raised Louisiana's level of culture and industry, and was one of the reasons why Louisiana was able to gain statehood so quickly. A quote from a Louisiana Creole who remarked on the rapid development of his homeland:

Louisiana Creole Exceptionalism

Louisiana's development and growth was rapid after its admission as a member state of the American Union. By 1850, 1/3 of all Creoles of color owned over $100,000 worth of property. Creoles of color were wealthy businessmen, entrepreneurs, clothiers, real estate developers, doctors, and other respected professions; they owned estates and properties in French Louisiana. Aristocratic Creoles of Color were very wealthy, such as Aristide Mary who owned more than $1,500,000 of property in theState of Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25th i ...

.

Nearly all boys of wealthy Creole families were sent to France where they received an excellent classical education.

Being a French, and later Spanish colony, Louisiana maintained a three-tiered society that was very similar to other Latin American and Caribbean countries, with the three tiers: aristocracy

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense Economy, economic, Politics, political, and soc ...

(''grands habitants''), bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and aristocracy. They are traditionally contrasted wi ...

, and peasantry

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasan ...

(''petits habitants''). The blending of cultures and races created a society unlike any other in America.

Minnesota French

The history of the French language in Minnesota is closely linked with that of Canadian settlers, such as explorerLouis Hennepin

Louis Hennepin, OFM (born Antoine Hennepin; ; 12 May 1626 – 5 December 1704) was a Belgian Catholic priest and missionary best known for his activities in North America. A member of the Recollects, a minor branch of the Franciscans, he travel ...

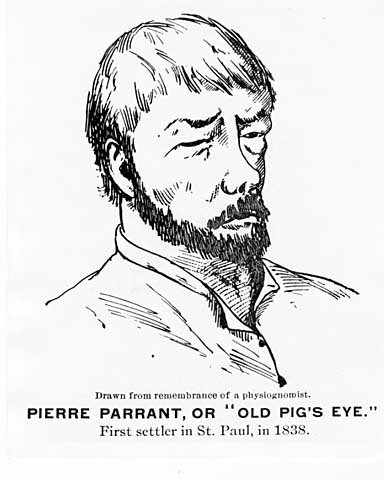

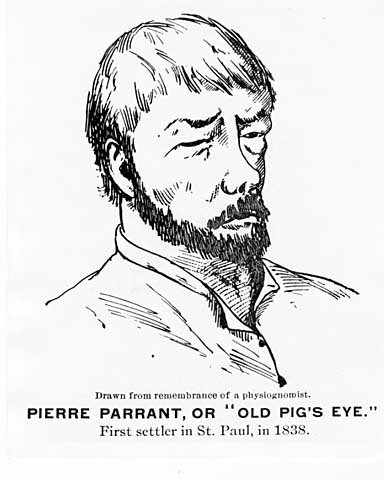

and trapper Pierre Parrant

Pierre "Pig's Eye" Parrant was the first official resident of the city of Saint Paul, Minnesota. His exploits propelled him to local fame and infamy, with his name briefly adorning the village that became Minnesota's capital city.

History

Sour ...

, who contributed very early on to its use in the area.

As early as the mid-17th century, evidence shows the presence of French expeditions, settlements and villages in the region, in particular thanks to Frenchmen Pierre-Esprit Radisson

Pierre-Esprit Radisson (1636/1640–1710) was a French coureur des bois and explorer in New France. He is often linked to his brother-in-law Médard des Groseilliers. The decision of Radisson and Groseilliers to enter the English service led to ...

and Médard des Groseilliers

Médard Chouart des Groseilliers (born 1618) was a French explorer and fur trader in Canada. He is often paired with his brother-in-law Pierre-Esprit Radisson, who was about 20 years younger. The pair worked together in fur trading and explorat ...

, who likely reached Minnesota in 1654 after exploring Wisconsin.2004 : ''Minnesota French Facts'' )

A few years later, explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, Cavelier de la Salle charted the

A few years later, explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, Cavelier de la Salle charted the Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

, ending his voyage in the neighboring state of North Dakota. He gave this region the nickname of "''L'étoile du Nord''" (Star of the North), which eventually became the motto of the State of Minnesota.

The exploration of the northern territories and areas surrounding the Great Lake, including Minnesota, was encouraged by Frontenac, the Governor of New France

New France (, ) was the territory colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Kingdom of Great Br ...

.

In the early days of Minnesota's settlement, many of its early European inhabitants were of Canadian origin, including Pierre Parrant

Pierre "Pig's Eye" Parrant was the first official resident of the city of Saint Paul, Minnesota. His exploits propelled him to local fame and infamy, with his name briefly adorning the village that became Minnesota's capital city.

History

Sour ...

, a trapper and fur trader born in Sault Ste. Marie (Michigan) in 1777.

The Red River Métis

The Métis ( , , , ) are a mixed-race Indigenous people whose historical homelands include Canada's three Prairie Provinces extending into parts of Ontario, British Columbia, the Northwest Territories and the northwest United States. They ha ...

community also played an important part in the use of French in Minnesota.

Since 1858, when the State of Minnesota was established, the Great Seal of the State of Minnesota bears René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, Cavelier de la Salle's French motto "L'étoile du Nord".

In present-day Minnesota, French is maintained alive through bilingual education options and French-language classes in universities and schools. It is also promoted by local associations and groups such as AFRAN (Association des Français du Nord), who support events such as the Chautauqua Festival in Huot, an event celebrating the French heritage of local communities.Pierre Verrière, 2017 : ''Franco-Américains et francophones aux Etats-Unis'' In 2012, a Franco-fête Festival was held in Minneapolis. Similar events take place every year throughout the state of Minnesota. Since Minnesota shares a border with French-speaking areas of Canada, French exchanges remain common. In 2004, an estimated 35% of Minnesota's production was being exported to Francophone countries (Canada, France, Belgium and Switzerland).

Mississippi Creoles

In April 1699, French colonists established the first European settlement at ''Fort Maurepas

Fort Maurepas, later known as Old Biloxi,

"Pierre Le Moyne, Sieur d'Iberville" (biography),

''Catholic Encyclopedia'', 1907, webpage:

gives dates: 13 Feb. 1699, went to the mainland Biloxi,

with fort completion May 1, 1699; sailed f ...

'' (also known as Old Biloxi), built in the vicinity of present-day Ocean Springs, Mississippi, Ocean Springs on the Gulf Coast. It was settled by Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville

Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville (16 July 1661 – 9 July 1706) or Sieur d'Iberville was a French soldier, explorer, colonial administrator, and trader. He is noted for founding the colony of Louisiana in New France. He was born in Montreal to French ...

. In 1716, the French founded Natchez Natchez may refer to:

Places

* Natchez, Alabama, United States

* Natchez, Indiana, United States

* Natchez, Louisiana, United States

* Natchez, Mississippi, a city in southwestern Mississippi, United States

** Natchez slave market, Mississippi

* ...

on the Mississippi River (as ''Fort Rosalie

Fort Rosalie was built by the French in 1716 within the territory of the Natchez Native Americans as part of the French colonial empire in the present-day city of Natchez, Mississippi.

Early history

As part of the peace terms that ended t ...

''); it became the dominant town and trading post of the area. The French called the greater territory "New France

New France (, ) was the territory colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Kingdom of Great Br ...

"; the Spanish continued to claim part of the Gulf coast

The Gulf Coast of the United States, also known as the Gulf South or the South Coast, is the coastline along the Southern United States where they meet the Gulf of Mexico. The coastal states that have a shoreline on the Gulf of Mexico are Tex ...

area (east of Mobile Bay

Mobile Bay ( ) is a shallow inlet of the Gulf of Mexico, lying within the state of Alabama in the United States. Its mouth is formed by the Fort Morgan Peninsula on the eastern side and Dauphin Island, a barrier island on the western side. T ...

) of present-day southern Alabama, in addition to the entire area of present-day Florida. The British assumed control of the French territory after the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

.

Biloxi, First Capital of French Louisiana

Old Biloxi was completed on May 1, 1699

"Pierre Le Moyne, Sieur d'Iberville" (biography),

''Catholic Encyclopedia'', 1907, webpage:

Old Biloxi was completed on May 1, 1699

"Pierre Le Moyne, Sieur d'Iberville" (biography),

''Catholic Encyclopedia'', 1907, webpage:

CathEnc-7614b

gives dates: February 13, 1699, went to the mainland Biloxi, with fort completion May 1, 1699; sailed for France May 4. "Fort Maurepas", Mississippi Genealogy, 2002–2008, webpage:

under direction of French explorer

Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville

Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville (16 July 1661 – 9 July 1706) or Sieur d'Iberville was a French soldier, explorer, colonial administrator, and trader. He is noted for founding the colony of Louisiana in New France. He was born in Montreal to French ...

, who sailed for France on May 4. He appointed his teenage brother Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville (; ; February 23, 1680 – March 7, 1767), also known as Sieur de Bienville, was a French-Canadian colonial administrator in New France. Born in Montreal, he was an early governor of French Louisiana, appo ...

as second in command after the French commandant Sauvolle de la Villantry (c.1671–1701).

M. d'Iberville originally intended to establish a French colony along the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

. However, because of its flooding, he had been unable to find a suitable location during his first voyage of discovery up the Mississippi in March 1699. He returned from his river journey on April 1, and spent another week in searching the shores adjacent to Ship Island

Ship Island is a barrier island off the Gulf Coast of Mississippi, one of the Mississippi–Alabama barrier islands. Hurricane Camille split the island into two separate islands (West Ship Island and East Ship Island) in 1969. In early 2019, ...

, where the fleet had been anchored.

On Tuesday, April 7, 1699, d'Iberville and Surgeres observed "an elevated place that appeared very suitable". This spot was on the northeast shore of Biloxi Bay

Biloxi ( ; ) is a city in Harrison County, Mississippi, United States. It lies on the Gulf Coast in southern Mississippi, bordering the city of Gulfport to its west. The adjacent cities are both designated as seats of Harrison County. The popu ...