Frederick Browning on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Frederick Arthur Montague Browning (20 December 1896 – 14 March 1965) was a senior officer of the

Browning was granted the substantive (permanent) rank of captain on 24 November 1920. He retained his post as adjutant until November 1921, when he was posted to the Guards' Depot at Caterham Barracks. In 1924 he was posted to Sandhurst as adjutant. He was the first adjutant, during the Sovereign's Parade of 1926, to ride his horse (named "The Vicar") up the steps of Old College and to dismount in the Grand Entrance. There is no satisfactory explanation as to why he did it. After the

Browning was granted the substantive (permanent) rank of captain on 24 November 1920. He retained his post as adjutant until November 1921, when he was posted to the Guards' Depot at Caterham Barracks. In 1924 he was posted to Sandhurst as adjutant. He was the first adjutant, during the Sovereign's Parade of 1926, to ride his horse (named "The Vicar") up the steps of Old College and to dismount in the Grand Entrance. There is no satisfactory explanation as to why he did it. After the

In mid-May 1940, Browning, his rank of brigadier having by now been made temporary rather than acting, was given command of the

In mid-May 1940, Browning, his rank of brigadier having by now been made temporary rather than acting, was given command of the

In mid–September, as the 1st Airborne Division was coming close to reaching full strength, Browning was informed that

In mid–September, as the 1st Airborne Division was coming close to reaching full strength, Browning was informed that

On 1 January 1943, Browning was appointed a

On 1 January 1943, Browning was appointed a

Browning assumed a new command on 4 December 1943. His Directive No. 1 announced that "the title of the force is Headquarters, Airborne Troops (

Browning assumed a new command on 4 December 1943. His Directive No. 1 announced that "the title of the force is Headquarters, Airborne Troops ( Browning landed by gliders with a tactical headquarters near

Browning landed by gliders with a tactical headquarters near

Events took a different course.

Events took a different course.

British Army Officers 1939−1945

, - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Browning, Frederick 1896 births 1965 deaths Academics of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst Airborne warfare Bobsledders at the 1928 Winter Olympics British Army generals of World War II British Army lieutenant generals British Army personnel of World War I British male bobsledders

British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

who has been called the "father of the British airborne forces

Airborne forces are ground combat units carried by aircraft and airdropped into battle zones, typically by parachute drop. Parachute-qualified infantry and support personnel serving in airborne units are also known as paratroopers.

The main ...

". He was also an Olympic bobsleigh

Bobsleigh or bobsled is a winter sport in which teams of 2 to 4 athletes make timed speed runs down narrow, twisting, banked, iced tracks in a gravity-powered sleigh. International bobsleigh competitions are governed by the International Bobslei ...

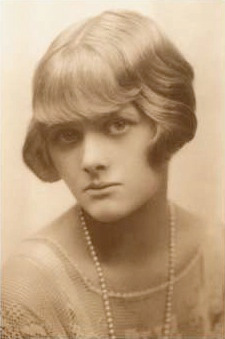

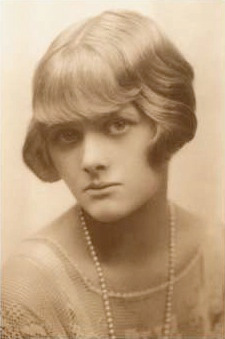

competitor, and the husband of author Daphne du Maurier

Dame Daphne du Maurier, Lady Browning, (; 13 May 1907 – 19 April 1989) was an English novelist, biographer and playwright. Her parents were actor-manager Gerald du Maurier, Sir Gerald du Maurier and his wife, actress Muriel Beaumont. Her gra ...

.

Educated at Eton College

Eton College ( ) is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school providing boarding school, boarding education for boys aged 13–18, in the small town of Eton, Berkshire, Eton, in Berkshire, in the United Kingdom. It has educated Prime Mini ...

and then at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst

The Royal Military College (RMC) was a United Kingdom, British military academy for training infantry and cavalry Officer (armed forces), officers of the British Army, British and British Indian Army, Indian Armies. It was founded in 1801 at Gre ...

, Browning was commissioned as a second lieutenant into the Grenadier Guards

The Grenadier Guards (GREN GDS) is the most senior infantry regiment of the British Army, being at the top of the Infantry Order of Precedence. It can trace its lineage back to 1656 when Lord Wentworth's Regiment was raised in Bruges to protect ...

in 1915. During the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, he fought on the Western Front, and was awarded the Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a Military awards and decorations, military award of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly throughout the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth, awarded for operational gallantry for highly successful ...

for conspicuous gallantry during the Battle of Cambrai in November 1917. In September 1918, he became aide de camp to General Sir Henry Rawlinson.

During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Browning commanded the 1st Airborne Division and I Airborne Corps, and was also the deputy commander of First Allied Airborne Army

The First Allied Airborne Army was an Allies of World War II, Allied Military organization, formation formed on 2 August 1944 by the order of General of the Army (United States), General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Headquarters Allied Exped ...

during Operation Market Garden in September 1944. During the planning for this operation, it has been suggested that he said: "I think we might be going a bridge too far." In December 1944 he became chief of staff of Admiral Lord Mountbatten

Admiral of the Fleet (Royal Navy), Admiral of the Fleet Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (born Prince Louis of Battenberg; 25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979), commonly known as Lord Mountbatten, was ...

's South East Asia Command

South East Asia Command (SEAC) was the body set up to be in overall charge of Allied operations in the South-East Asian Theatre during the Second World War.

History Organisation

The initial supreme commander of the theatre was General Sir ...

. From September 1946 to January 1948, he was Military Secretary of the War Office

The War Office has referred to several British government organisations throughout history, all relating to the army. It was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, at ...

.

In January 1948, Browning became comptroller

A comptroller (pronounced either the same as ''controller'' or as ) is a management-level position responsible for supervising the quality of accountancy, accounting and financial reporting of an organization. A financial comptroller is a senior- ...

and treasurer

A treasurer is a person responsible for the financial operations of a government, business, or other organization.

Government

The treasury of a country is the department responsible for the country's economy, finance and revenue. The treasure ...

to Princess Elizabeth, Duchess of Edinburgh. After she ascended to the throne as Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 19268 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. ...

in 1952, he became treasurer in the Office of the Duke of Edinburgh

The Royal Households of the United Kingdom are the collective departments that support members of the British royal family. Many members of the royal family who undertake public duties have separate households. They vary considerably in size, f ...

. He suffered a severe nervous breakdown

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness, a mental health condition, or a psychiatric disability, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. A mental disorder is ...

in 1957 and retired in 1959. He died at Menabilly, the mansion that inspired his wife's novel ''Rebecca

Rebecca () appears in the Hebrew Bible as the wife of Isaac and the mother of Jacob and Esau. According to biblical tradition, Rebecca's father was Bethuel the Aramean from Paddan Aram, also called Aram-Naharaim. Rebecca's brother was Laban (Bi ...

'', on 14 March 1965.

Early life

Frederick Arthur Montague Browning was born on 20 December 1896 at his family home at 31 Hans Road, Brompton, London. The house was later demolished to make way for an expansion ofHarrods

Harrods is a Listed building, Grade II listed luxury department store on Brompton Road in Knightsbridge, London, England. It was designed by C. W. Stephens for Charles Digby Harrod, and opened in 1905; it replaced the first store on the ground ...

, allowing him to claim in later life that he had been born in its piano department. He was the first son of Frederick Henry Browning, a wine merchant, and his wife Anne "Nancy" née

The birth name is the name of the person given upon their birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name or to the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a births registe ...

Alt. He had one sibling, an older sister, Helen Grace. From an early age, he was known to his family as "Tommy". He was educated at West Downs School and Eton College

Eton College ( ) is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school providing boarding school, boarding education for boys aged 13–18, in the small town of Eton, Berkshire, Eton, in Berkshire, in the United Kingdom. It has educated Prime Mini ...

, which his grandfather had attended. While at Eton, he joined the Officer Training Corps.

First World War

Browning sat the entrance examinations for theRoyal Military College, Sandhurst

The Royal Military College (RMC) was a United Kingdom, British military academy for training infantry and cavalry Officer (armed forces), officers of the British Army, British and British Indian Army, Indian Armies. It was founded in 1801 at Gre ...

, on 24 November 1914. Although he did not achieve the necessary scores in all the required subjects, the headmasters of some schools, including Eton, were in a position to recommend students for nomination by the Army Council. The headmaster of Eton, Edward Lyttelton, put Browning's name forward and in this way he entered Sandhurst on 27 December 1914. He graduated on 16 June 1915, and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Grenadier Guards

The Grenadier Guards (GREN GDS) is the most senior infantry regiment of the British Army, being at the top of the Infantry Order of Precedence. It can trace its lineage back to 1656 when Lord Wentworth's Regiment was raised in Bruges to protect ...

. Joining such an exclusive regiment, even in wartime, required a personal introduction and an interview by the regimental commander, Colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

Sir Henry Streatfeild.

Initially, Browning, promoted to lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

on 15 July, joined the 4th Battalion, Grenadier Guards, which was training at Bovington Camp. When the 4th Battalion departed for the Western Front in August 1915, he was transferred to the 5th (Reserve) Battalion. In October 1915 he left it to join the 2nd Battalion at the front. The battalion formed part of the 1st Guards Brigade of the Guards Division

The Guards Division was an administrative unit of the British Army responsible for the training and administration of the regiments of Foot Guards and the London Guards reserve battalion. The Guards Division was responsible for providing tw ...

. Around this time he acquired the nickname "Boy". For a time he served in the same company of 2nd Battalion as Major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

. Upon Churchill's arrival, Browning was given the job of showing him the company's trenches. When Browning discovered that Churchill had no greatcoat

A greatcoat (also watchcoat) is a large, woollen overcoat designed for warmth and protection against wind and weather, and features a collar that can be turned up and cuffs that can be turned down to protect the face and the hands, while the Cap ...

, Browning gave Churchill his own. When Churchill died in 1965, the 2nd Battalion, Grenadier Guards provided his guard of honour.

Browning was invalided back to England with trench fever in January 1916, and, although only hospitalised for four weeks, was not passed as fit for service at the front until 20 September, and did not rejoin the 2nd Battalion at the front until 6 October 1916. After being discharged from hospital, he went on leave for two months. In April he was posted to the 5th (Reserve) Battalion, and then to the Guards Depot at Caterham Barracks.

Browning fought in the Battle of Pilckem Ridge

The Battle of Pilckem Ridge (31 July – 2 August 1917) was the opening attack of the Third Battle of Ypres in the First World War. The British Fifth Army (United Kingdom), Fifth Army, supported by the Second Army (United Kingdom), Second Army o ...

on 31 July 1917, the Battle of Poelcappelle on 9 October and the Battle of Cambrai in November. He distinguished himself at Cambrai and was later awarded the Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a Military awards and decorations, military award of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly throughout the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth, awarded for operational gallantry for highly successful ...

(DSO), usually given only to officers in command, above the rank of lieutenant-colonel. When a junior officer like Browning, who was still only a lieutenant, was awarded the DSO, this was often regarded as an acknowledgement that the officer had only just missed out on being awarded the Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious decoration of the Orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom, British decorations system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British ...

(VC). His citation read:

He was awarded the French Croix de Guerre

The (, ''Cross of War'') is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was first awarded during World ...

on 14 December 1917, the same month he was made an acting

Acting is an activity in which a story is told by means of its enactment by an actor who adopts a character—in theatre, television, film, radio, or any other medium that makes use of the mimetic mode.

Acting involves a broad range of sk ...

captain, a rank he held until December 1920, and was mentioned in despatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face of t ...

on 23 May 1918. In September 1918, during the Hundred Days Offensive

The Hundred Days Offensive (8 August to 11 November 1918) was a series of massive Allied offensives that ended the First World War. Beginning with the Battle of Amiens (8–12 August) on the Western Front, the Allies pushed the Imperial Germa ...

which saw the tide of the war turn in favour of the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

, Browning temporarily became aide de camp to General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

Sir Henry Rawlinson, commander of the British Fourth Army. The appointment only lasted a few weeks, however, before Browning returned to his regiment in early November. He was promoted to the temporary rank of captain, and appointed adjutant

Adjutant is a military appointment given to an Officer (armed forces), officer who assists the commanding officer with unit administration, mostly the management of “human resources” in an army unit. The term is used in French-speaking armed ...

of the 1st Grenadier Guards, then part of the 3rd Guards Brigade of the Guards Division, in November 1918.

Inter-war period

Browning was granted the substantive (permanent) rank of captain on 24 November 1920. He retained his post as adjutant until November 1921, when he was posted to the Guards' Depot at Caterham Barracks. In 1924 he was posted to Sandhurst as adjutant. He was the first adjutant, during the Sovereign's Parade of 1926, to ride his horse (named "The Vicar") up the steps of Old College and to dismount in the Grand Entrance. There is no satisfactory explanation as to why he did it. After the

Browning was granted the substantive (permanent) rank of captain on 24 November 1920. He retained his post as adjutant until November 1921, when he was posted to the Guards' Depot at Caterham Barracks. In 1924 he was posted to Sandhurst as adjutant. He was the first adjutant, during the Sovereign's Parade of 1926, to ride his horse (named "The Vicar") up the steps of Old College and to dismount in the Grand Entrance. There is no satisfactory explanation as to why he did it. After the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

this became an enduring tradition, but since horses have great difficulty going down steps, a ramp is now provided for the horse to return.

Other members of staff at Sandhurst at the time included Richard O'Connor

General (United Kingdom), General Sir Richard Nugent O'Connor, (21 August 1889 – 17 June 1981) was a senior British Army Officer (armed forces), officer who fought in both the First World War, First and Second World Wars, and commanded the ...

, Miles Dempsey, Douglas Gracey, Ronald Brittain and Eric Dorman-Smith. Dorman-Smith and Browning became close friends. Browning relinquished the appointment of adjutant at Sandhurst on 28 April 1928, and was promoted to major on 22 May 1928. Following a pattern whereby tours of duty away from the regiment alternated with those in it, he was sent for a refresher course at the Small Arms School before being posted to the 2nd Battalion, Grenadier Guards

The Grenadier Guards (GREN GDS) is the most senior infantry regiment of the British Army, being at the top of the Infantry Order of Precedence. It can trace its lineage back to 1656 when Lord Wentworth's Regiment was raised in Bruges to protect ...

, at Pirbright

Pirbright () is a village in Surrey, England. Pirbright is in the Guildford (borough), borough of Guildford and has a civil parish council covering the traditional boundaries of the area. Pirbright contains one buffered sub-locality, Stanford ...

.

His workload was very light, allowing plenty of time for sport. Browning competed in the Amateur Athletic Association of England championships in hurdling

Hurdling is the act of jumping over an obstacle at a high speed or in a sprint. In the early 19th century, hurdlers ran at and jumped over each hurdle (sometimes known as 'burgles'), landing on both feet and checking their forward motion. Today ...

, finishing third behind L. H. Phillips in the 440 yards hurdles event at the 1923 AAA Championships but failed to make Olympic selection. He did however make the Olympic five-man bobsleigh

Bobsleigh or bobsled is a winter sport in which teams of 2 to 4 athletes make timed speed runs down narrow, twisting, banked, iced tracks in a gravity-powered sleigh. International bobsleigh competitions are governed by the International Bobslei ...

team as brake-man. An injury incurred during a training accident prevented his participation in the bobsleigh at the 1924 Winter Olympics

At the 1924 Winter Olympics, only one bobsleigh event was contested, the four man event. However, rules at the time also allowed a fifth sledder to compete. The event was held on Saturday and Sunday, 2 and 3 February 1924.

Medalists

Results

...

, but he competed in the bobsleigh at the 1928 Winter Olympics in St. Moritz

St. Moritz ( , , ; ; ; ; ) is a high Alpine resort town in the Engadine in Switzerland, at an elevation of about above sea level. It is Upper Engadine's major town and a municipality in the administrative region of Maloja in the Swiss ...

, Switzerland, in which his team finished tenth. Browning was also a keen sailor, competing in the Household Cavalry Sailing Regatta at Chichester Harbour

Chichester Harbour is a large natural harbour in West Sussex and Hampshire. It is situated to the south-west of the city of Chichester and to the north of the Solent. The harbour and surrounding land has been designated as an Area of Outstand ...

in 1930. He purchased his own motor boat, a cabin cruiser

A cabin cruiser is a type of power boat that provides accommodation for its crew and passengers inside the structure of the craft.

A cabin cruiser usually ranges in size from in length, with larger pleasure craft usually considered yachts. Man ...

that he named ''Ygdrasil''.

In 1931, Browning read Daphne du Maurier

Dame Daphne du Maurier, Lady Browning, (; 13 May 1907 – 19 April 1989) was an English novelist, biographer and playwright. Her parents were actor-manager Gerald du Maurier, Sir Gerald du Maurier and his wife, actress Muriel Beaumont. Her gra ...

's novel '' The Loving Spirit'' and, impressed by its graphic depictions of the Cornish coastline, set out to see it for himself on ''Ygdrasil''. Afterwards, he left the boat moored in the River Fowey

The River Fowey ( ; ) is a river in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. Its source (river), source is at Fowey Well (originally , meaning ''spring of the river Fowey'') about north-west of Brown Willy on Bodmin Moor, not far from one of its trib ...

for the winter, and returned in April 1932 to collect it. He heard that the author of the book that had impressed him so much was convalescing from an appendix operation, and invited her out on his boat. After a short romance, he proposed to her but she rejected this, as she did not believe in marriage. Dorman-Smith visited her and explained that it would be disastrous for Browning's career for him to live with Du Maurier without marriage. Du Maurier then proposed to Browning, who accepted. They were married in a simple ceremony at the Church of St Willow, Lanteglos-by-Fowey

Lanteglos (, meaning ''church valley'') is a coastal civil parishes in England, civil parish in south Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is on the east side of the tidal estuary of the River Fowey which separates it from the town and civil pa ...

on 19 July 1932, and honeymooned on ''Ygdrasil''. Their marriage produced three children: two daughters, Tessa (later second wife of David Montgomery, 2nd Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, son and heir of Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army (in countries without the rank of Generalissimo), and as such, few persons a ...

Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence and the ...

) and Flavia (later wife of General Sir Peter Leng), and a son, Christian, known as Kits.

Browning was promoted to lieutenant-colonel on 1 February 1936, and was appointed commanding officer of the 2nd Battalion, Grenadier Guards. The battalion was deployed to Egypt in 1936 and returned in December 1937. His term as commander ended on 1 August 1939; he was removed from the Grenadier Guards' regimental list but remained on full pay. On 1 September, he was promoted to colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

, with his seniority backdated to 1 February 1939, and became assistant commandant of the Small Arms School.

Second World War

Airborne troops

Establishment

Browning remained in this position for a month before becoming the school's commandant, which saw him promoted to the acting rank ofbrigadier

Brigadier ( ) is a military rank, the seniority of which depends on the country. In some countries, it is a senior rank above colonel, equivalent to a brigadier general or commodore (rank), commodore, typically commanding a brigade of several t ...

. Despite this being an important job he was not altogether pleased with the assignment: his wish was to be with one of the three regular Grenadier battalions out in France.

In mid-May 1940, Browning, his rank of brigadier having by now been made temporary rather than acting, was given command of the

In mid-May 1940, Browning, his rank of brigadier having by now been made temporary rather than acting, was given command of the 128th (Hampshire) Infantry Brigade

The Hampshire Brigade, previously the Portsmouth Brigade and later 128th (Hampshire) Brigade, was an infantry formation of the British Army of the Volunteer Force, Territorial Force (TF) and Territorial Army (United Kingdom), Territorial Army (TA) ...

, consisting of the 1/4th, 2/4th and 5th Battalions of the Hampshire Regiment

The Hampshire Regiment was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, created as part of the Childers Reforms in 1881 by the amalgamation of the 37th (North Hampshire) Regiment of Foot and the 67th (South Hampshire) Regiment of Foot. The re ...

. Part of the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division

The 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division was an infantry Division (military), division of Britain's Territorial Army (United Kingdom), Territorial Army (TA). The division was first formed in 1908, as the Wessex Division. During the World War I, First ...

, which was then commanded by Major-General Robert Pollok, the brigade was a Territorial Army unit that was preparing to join the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in France. This was pre-empted by the Dunkirk evacuation

The Dunkirk evacuation, codenamed Operation Dynamo and also known as the Miracle of Dunkirk, or just Dunkirk, was the evacuation of more than 338,000 Allied soldiers during the Second World War from the beaches and harbour of Dunkirk, in the ...

and the subsequent fall of France

The Battle of France (; 10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign (), the French Campaign (, ) and the Fall of France, during the Second World War was the German invasion of the Low Countries (Belgium, Luxembourg and the Net ...

in June, and the division instead assumed a defensive posture.

The next few months were spent in numerous activities, the most important of which was training to repel a possible German invasion of Britain. The severe shortage of equipment that plagued the army during this time made Browning's already formidable task even more difficult. Despite this, he managed to impress his superiors, including his immediate superior, Pollok, who was inspired by the way in which Browning's brigade responded to his command. He recommended Browning for the command of a division, as did Lieutenant-General Francis Nosworthy, commanding IV Corps (the 43rd Division's parent formation), and Lieutenant-General Guy Williams, General Officer Commanding-in-Chief of Eastern Command, although all three believed that Browning needed more time and experience.

In late February 1941, after handing over the brigade to Brigadier Manley James, Browning succeeded Brigadier The Hon. William Fraser, a fellow Grenadier Guardsman and an old friend, in command of the 24th Guards Brigade Group. Such was his popularity by now within the 128th Brigade, that when Browning left his old command many members of the brigade turned out to cheer him on and wish him well. While the 24th Brigade was not a division, it was perhaps the next best thing to one. The brigade group's objective was to defend London from an attack from the south.

On 3 November 1941, Browning was promoted to the acting rank of major-general, and appointed as the first General Officer Commanding

General officer commanding (GOC) is the usual title given in the armies of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth (and some other nations, such as Ireland) to a general officer who holds a command appointment.

Thus, a general might be the GOC ...

(GOC) of the newly created 1st Airborne Division. The division initially comprised the 1st Parachute Brigade, under Brigadier Richard Gale, and the 1st Airlanding Brigade, under Brigadier George Hopkinson. In this new role he was instrumental in parachutists

Parachuting and skydiving are methods of descending from a high point in an atmosphere to the ground or ocean surface with the aid of gravity, involving the control of speed during the descent using a parachute or multiple parachutes.

For hu ...

adopting the maroon beret

The maroon beret in a military configuration has been an international symbol of airborne forces since the World War II, Second World War. It was first officially introduced by the British Army in 1942, at the direction of Major-general (Uni ...

, and assigned an artist, Major Edward Seago, to design the Parachute Regiment's emblem of the mythical Greek hero Bellerophon

Bellerophon or Bellerophontes (; ; lit. "slayer of Belleros") or Hipponous (; lit. "horse-knower"), was a divine Corinthian hero of Greek mythology, the son of Poseidon and Eurynome, and the foster son of Glaukos. He was "the greatest her ...

riding the winged horse Pegasus

Pegasus (; ) is a winged horse in Greek mythology, usually depicted as a white stallion. He was sired by Poseidon, in his role as horse-god, and foaled by the Gorgon Medusa. Pegasus was the brother of Chrysaor, both born from Medusa's blood w ...

. Because of this he has been called the "father of the British airborne forces

Airborne forces are ground combat units carried by aircraft and airdropped into battle zones, typically by parachute drop. Parachute-qualified infantry and support personnel serving in airborne units are also known as paratroopers.

The main ...

". Browning designed his own uniform. He qualified as a pilot in 1942, and henceforth wore the Army Air Corps wings, which he also designed.

Training

Browning supervised the newly formed division as it underwent a prolonged period of expansion and intensive training, with new brigades raised and assigned to the division, and new equipment tested. Though not considered an airborne warfare visionary, he proved adept at dealing with theWar Office

The War Office has referred to several British government organisations throughout history, all relating to the army. It was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, at ...

and Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force and civil aviation that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the ...

, and demonstrated a knack for overcoming bureaucratic obstacles. As the airborne forces expanded in size, the major difficulty in getting the 1st Airborne Division ready for operations was a shortage of aircraft. The Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

(RAF) had neglected air transport before the war, and the only available aircraft for airborne troops were conversions of obsolete bombers like the Armstrong Whitworth Whitley

The Armstrong Whitworth A.W.38 Whitley was a British medium/heavy bomber aircraft of the 1930s. It was one of three twin-engined, front line medium bomber types that were in service with the Royal Air Force (RAF) at the outbreak of the World W ...

.

When Churchill, who was now the Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

, and General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

George C. Marshall, the Chief of Staff of the United States Army

The chief of staff of the Army (CSA) is a statutory position in the United States Army held by a general officer. As the highest-ranking officer assigned to serve in the Department of the Army, the chief is the principal military advisor and a ...

, visited the 1st Airborne Division on 16 April 1942, they were treated to a demonstration involving every available aircraft of No. 38 Wing RAF—12 Whitleys and nine Hawker Hector target-tug biplanes towing General Aircraft Hotspur

The General Aircraft GAL.48 Hotspur was a military glider designed and built by the British company General Aircraft Limited, General Aircraft Ltd during World War II. When the British airborne forces, airborne establishment was formed in 1940 ...

gliders. At a meeting on 6 May chaired by Churchill, Browning was asked what he required. He stated that he needed 96 aircraft to get the 1st Airborne Division battle-ready. Churchill directed Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles Portal to find the required aircraft, and Portal "grudgingly" agreed to supply 83 Whitleys, along with 10 Halifax bombers to tow the new, larger General Aircraft Hamilcar gliders. Air Marshal Sir Arthur Harris

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Arthur Travers Harris, 1st Baronet, (13 April 1892 – 5 April 1984), commonly known as "Bomber" Harris by the press and often within the RAF as "Butcher" or "Butch" Harris, was Air Officer Commanding, Air O ...

, Commander-in-Chief RAF Bomber Command

RAF Bomber Command controlled the Royal Air Force's bomber forces from 1936 to 1968. Along with the United States Army Air Forces, it played the central role in the Strategic bombing during World War II#Europe, strategic bombing of Germany in W ...

, in particular, felt that the 1st Airborne Division was not worth the drain on Bomber Command's resources.

In July 1942, Browning travelled to the United States, where he toured airborne training facilities with his American counterpart, Major-General William C. Lee, who soon took command of the US 101st Airborne Division

The 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) ("Screaming Eagles") is a light infantry division (military), division of the United States Army that specializes in air assault military operation, operations. The 101st is designed to plan, coordinat ...

. Browning's tendency to lecture the Americans on airborne warfare made him few friends among the Americans, who felt that the British were still novices themselves. Browning was envious of the Americans' equipment, particularly the Douglas C-47

The Douglas C-47 Skytrain or Dakota ( RAF designation) is a military transport aircraft developed from the civilian Douglas DC-3 airliner. It was used extensively by the Allies during World War II. During the war the C-47 was used for troo ...

(known in British service as "Dakota") transport aircraft. On returning to the United Kingdom in early August, he arranged for a joint exercise to be conducted with the 2nd Battalion, 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment (2/503) and the 1st Airlanding Brigade, with the 1st Parachute Brigade and the 2nd (Armoured) Battalion of the Irish Guards

The Irish Guards (IG) is one of the Foot guards#United Kingdom, Foot Guards regiments of the British Army and is part of the Guards Division. Together with the Royal Irish Regiment (1992), Royal Irish Regiment, it is one of the two Irish infant ...

.

Operation Torch

In mid–September, as the 1st Airborne Division was coming close to reaching full strength, Browning was informed that

In mid–September, as the 1st Airborne Division was coming close to reaching full strength, Browning was informed that Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8–16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of securing victory in North Africa whil ...

, the Allied invasion of French North Africa

French North Africa (, sometimes abbreviated to ANF) is a term often applied to the three territories that were controlled by France in the North African Maghreb during the colonial era, namely Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. In contrast to French ...

, would take place in November. When he found that the 2/503 was to take part, Browning argued that a larger airborne force should be utilised, as the vast distances and comparatively light opposition would provide opportunities for airborne operations. The War Office and the Commander-in-Chief, Home Forces, General Sir Bernard Paget, were won over by Browning's arguments, and agreed to detach the 1st Parachute Brigade, now under Brigadier Edwin Flavell, from 1st Airborne Division and place it under the command of US Lieutenant-General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was normall ...

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

, who would command all Allied troops participating in the invasion. After it had been brought to full operational strength, partly by cross-posting personnel from the newly formed 2nd Parachute Brigade, and had been provided with sufficient equipment and resources, the brigade departed for North Africa at the beginning of November.

The results of British airborne operations in North Africa were mixed, and the subject of a detailed report by Browning. The airborne troops had operated under several handicaps, including shortages of aerial photographs and maps of the target area. All the troop carrier aircrew were American, and lacked familiarity with airborne operations and in dealing with British troops and equipment. Browning felt that the inexperience with handling airborne operations extended to Eisenhower's Allied Force Headquarters

Allied Force Headquarters (AFHQ) was the headquarters that controlled all Allied operational forces in the Mediterranean theatre of World War II from August 1942 until the end of the war in Europe in May 1945.

History

AFHQ was established i ...

(AFHQ) and that of the British First Army, resulting in the paratroops being misused. He felt that had they been employed more aggressively and in greater strength they might have shortened the Tunisian campaign

The Tunisian campaign (also known as the battle of Tunisia) was a series of battles that took place in Tunisia during the North African campaign of the Second World War, between Axis and Allied forces from 17 November 1942 to 13 May 1943. Th ...

by some months. The 1st Parachute Brigade was called the "''Rote Teufel''" ("Red Devils") by the German troops they had fought. Browning pointed out to the brigade that this was an honour, as "distinctions given by the enemy are seldom won in battle except by the finest fighting troops." The title was officially confirmed by General Sir Harold Alexander, commander of the Allied 18th Army Group, formed from British Eighth Army

The Eighth Army was a field army of the British Army during the Second World War. It was formed as the Western Army on 10 September 1941, in Egypt, before being renamed the Army of the Nile and then the Eighth Army on 26 September. It was cr ...

(advancing from the east into Tunisia) and First Army. Henceforth, it applied to all British airborne troops.

Allied Force Headquarters posting

On 1 January 1943, Browning was appointed a

On 1 January 1943, Browning was appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath

Companion may refer to:

Relationships Currently

* Any of several interpersonal relationships such as friend or acquaintance

* A domestic partner, akin to a spouse

* Sober companion, an addiction treatment coach

* Companion (caregiving), a caregi ...

. He relinquished command of the 1st Airborne Division to Hopkinson in March 1943 to take up a new post as Major-General, Airborne Forces at Eisenhower's AFHQ. He soon clashed with the commander of the American 82nd Airborne Division

The 82nd Airborne Division is an Airborne forces, airborne infantry division (military), division of the United States Army specializing in Paratrooper, parachute assault operations into hostile areasSof, Eric"82nd Airborne Division" ''Spec Ops ...

, Major-General Matthew Ridgway

Matthew Bunker Ridgway (3 March 1895 – 26 July 1993) was a senior officer in the United States Army, who served as Supreme Allied Commander Europe (1952–1953) and the 19th Chief of Staff of the United States Army (1953–1955). Although he ...

. When Browning asked to see the plans for Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily

The Allied invasion of Sicily, also known as the Battle of Sicily and Operation Husky, was a major campaign of World War II in which the Allies of World War II, Allied forces invaded the island of Sicily in July 1943 and took it from the Axis p ...

, Ridgway replied that they would not be available for scrutiny until after they had been approved by the US Seventh Army commander, Lieutenant-General George S. Patton. When Browning protested, Patton backed Ridgway, but Eisenhower and his chief of staff, Major-General Walter Bedell Smith

General (United States), General Walter Bedell "Beetle" Smith (5 October 1895 – 9 August 1961) was a senior officer (armed forces), officer of the United States Army who served as General Dwight D. Eisenhower's chief of staff at Allied Forc ...

, supported Browning and forced them to back down.

Browning's dealings with the British Army were no smoother. Hopkinson sold the British Eighth Army commander, General Sir Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence and the ...

, on Operation Ladbroke, a glider landing to seize the Ponte Grande road bridge south of Syracuse

Syracuse most commonly refers to:

* Syracuse, Sicily, Italy; in the province of Syracuse

* Syracuse, New York, USA; in the Syracuse metropolitan area

Syracuse may also refer to:

Places

* Syracuse railway station (disambiguation)

Italy

* Provi ...

. Browning's objections to the operation were ignored, and attempts to discuss airborne operations with the corps commanders elicited a directive from Montgomery that all such discussion had to go through him. The operation was a disaster, as Browning had predicted. Inexperienced aircrew released the gliders too early, and many crashed into the sea; 252 soldiers were drowned. Those that made it to land were scattered over a wide area. The troops captured their objective, but were driven off by an Italian counterattack. Browning concluded that to be effective, the airborne advisor had to have equal rank with the army commanders.

In September 1943, Browning travelled to India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

, where he inspected the 50th Parachute Brigade, and met with Major-General Orde Wingate

Major-general (United Kingdom), Major General Orde Charles Wingate, (26 February 1903 – 24 March 1944) was a senior British Army officer known for his creation of the Chindits, Chindit deep-penetration missions in Japanese-held territory duri ...

, the commander of the Chindits

The Chindits, officially known as Long Range Penetration Groups, were special operations units of the British and Indian armies which saw action in 1943–1944 during the Burma Campaign of World War II. Brigadier Orde Wingate formed the ...

. Browning held a series of meetings with General Sir Claude Auchinleck

Field marshal (United Kingdom), Field Marshal Sir Claude John Eyre Auchinleck ( ) (21 June 1884 – 23 March 1981), was a British Indian Army commander who saw active service during the world wars. A career soldier who spent much of his militar ...

, the Commander-in-Chief, India

During the period of the Company and Crown rule in India, the Commander-in-Chief, India (often "Commander-in-Chief ''in'' or ''of'' India") was the supreme commander of the Indian Army from 1833 to 1947. The Commander-in-Chief and most of his ...

; Air Chief Marshal Sir Richard Peirse

Air Chief Marshal Sir Richard Edmund Charles Peirse, (30 September 1892 – 5 August 1970), served as a senior Royal Air Force commander.

RAF career

The son of Admiral Sir Richard Peirse and his wife Blanche Melville Wemyss-Whittaker, Richard ...

, the Air Officer Commander-in-Chief; and Lieutenant-General Sir George Giffard, the GOC Eastern Army. They discussed plans for improving the airborne establishment in India and expanding the airborne force there to a division. As a result of these discussions, and Browning's subsequent report to the War Office, the 44th Indian Airborne Division was formed in October 1944. Browning sent his most experienced airborne commander, Major-General Ernest Down, to India as GOC of the 44th Division. Formerly the commander of the 2nd Parachute Brigade, Down had succeeded Hopkinson as GOC 1st Airborne Division after Hopkinson had been killed in Italy. Down's replacement as GOC 1st Airborne Division was Montgomery's selection, Major-General Roy Urquhart

Major-general (United Kingdom), Major-General Robert Elliot "Roy" Urquhart, (28 November 1901 – 13 December 1988) was a British Army officer who saw service during the Second World War and Malayan Emergency. He became prominent for his role a ...

, an officer with no airborne experience, rather than Browning's choice, Brigadier Gerald Lathbury of the 1st Parachute Brigade. The decision was to become controversial.

US Brigadier-General James M. Gavin, recalled that when he travelled to England in November 1943 to assume command of the 82nd Airborne Division, Ridgway "cautioned me against the machinations and scheming of General F. M. Browning, who was the senior British airborne officer, and well he should have." Gavin was taken aback by Browning's criticism of Ridgway on the grounds that he had not parachuted into Sicily with his troops. US Major-General Ray Barker

Major general (United States), Major General Ray Wehnes Barker (December 10, 1889 – June 28, 1974) was a United States Army officer of the Allies of World War II, Allied Forces, and served in the European Theater of Operations during World War ...

, who worked in Eisenhower's Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force

Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF; ) was the headquarters of the Commander of Allies of World War II, Allied forces in northwest Europe, from late 1943 until the end of World War II. US General Dwight D. Eisenhower was the ...

(SHAEF), warned him that Browning was "an empire builder", an assessment with which Gavin came to agree.

Operation Market Garden

Browning assumed a new command on 4 December 1943. His Directive No. 1 announced that "the title of the force is Headquarters, Airborne Troops (

Browning assumed a new command on 4 December 1943. His Directive No. 1 announced that "the title of the force is Headquarters, Airborne Troops (21st Army Group

The 21st Army Group was a British headquarters formation formed during the Second World War. It controlled two field armies and other supporting units, consisting primarily of the British Second Army and the First Canadian Army. Established ...

). All correspondence will bear the official title, but verbally it will be known as the Airborne Corps and I will be referred to as the Corps Commander." He was promoted to lieutenant-general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was normall ...

on 7 January 1944, with his seniority backdated to 9 December 1943. He officially became commander of I Airborne Corps on 16 April 1944.

I Airborne Corps became part of the First Allied Airborne Army

The First Allied Airborne Army was an Allies of World War II, Allied Military organization, formation formed on 2 August 1944 by the order of General of the Army (United States), General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Headquarters Allied Exped ...

, commanded by Lieutenant-General Lewis H. Brereton

Lewis Hyde Brereton (June 21, 1890 – July 20, 1967) was a military aviation pioneer and lieutenant general in the United States Air Force. A 1911 graduate of the United States Naval Academy, he began his military career as a United States Army o ...

, in August 1944. While retaining command of the corps, Browning also became Deputy Commander of the First Allied Airborne Army, despite a poor relationship with Brereton and being disliked by many American officers. During preparations for one of many cancelled operations, Linnete II, his disagreement with Brereton over a risky operation caused him to threaten resignation, which, due to differences in military culture, Brereton regarded as tantamount to disobeying an order. Browning was forced to back down.

When I Airborne Corps was committed to action in Operation Market Garden in September 1944, Browning's rift with Brereton had severe repercussions. Browning was concerned about the timetable put forward by Major-General Paul L. Williams of the IX Troop Carrier Command, under which the drop was staggered over several days, with only one drop on the first day. This restricted the number of combat troops that would be available on the first day. He also disagreed with the British drop zones proposed by Air Vice Marshal Leslie Hollinghurst of No. 38 Group, which he felt were too distant from the bridge at Arnhem, but Browning felt unable to challenge the airmen.

Browning downplayed Ultra

Ultra may refer to:

Science and technology

* Ultra (cryptography), the codename for cryptographic intelligence obtained from signal traffic in World War II

* Adobe Ultra, a vector-keying application

* Sun Ultra series, a brand of computer work ...

evidence brought to him by his intelligence officer, Major Brian Urquhart, that the 9th SS Panzer Division ''Hohenstaufen'' and the 10th SS Panzer Division ''Frundsberg'' were in the Arnhem area, but was not as confident as he led his subordinates to believe. When informed that his airborne troops would have to hold the bridge for two days, Browning is said to have responded that they could hold it for four, but later claimed that he had added: "But I think we might be going a bridge too far."

Browning landed by gliders with a tactical headquarters near

Browning landed by gliders with a tactical headquarters near Nijmegen

Nijmegen ( , ; Nijmeegs: ) is the largest city in the Dutch province of Gelderland and the ninth largest of the Netherlands as a whole. Located on the Waal River close to the German border, Nijmegen is one of the oldest cities in the ...

with Gavin's 82nd Airborne Division on 17 September 1944, the first day of the operation. His use of 38 aircraft to move his corps headquarters on the first lift has been criticised. Half of these gliders carried signal equipment but for much of the operation he had no contact with either the British 1st Airborne Division at Arnhem

Arnhem ( ; ; Central Dutch dialects, Ernems: ''Èrnem'') is a Cities of the Netherlands, city and List of municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality situated in the eastern part of the Netherlands, near the German border. It is the capita ...

or Major-General Maxwell D. Taylor

Maxwell Davenport Taylor (26 August 1901 – 19 April 1987) was a senior United States Army Officer (armed forces), officer and diplomat during the Cold War. He served with distinction in World War II, most notably as commander of the 101st Air ...

's US 101st Airborne Division

The 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) ("Screaming Eagles") is a light infantry division (military), division of the United States Army that specializes in air assault military operation, operations. The 101st is designed to plan, coordinat ...

at Eindhoven

Eindhoven ( ; ) is a city and List of municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality of the Netherlands, located in the southern Provinces of the Netherlands, province of North Brabant, of which it is the largest municipality, and is also locat ...

. His headquarters had not been envisaged as a frontline unit, and the signals section that had been hastily assembled just weeks before lacked training and experience. In his pack, Browning carried three teddy bears and a framed print of Albrecht Dürer

Albrecht Dürer ( , ;; 21 May 1471 – 6 April 1528),Müller, Peter O. (1993) ''Substantiv-Derivation in Den Schriften Albrecht Dürers'', Walter de Gruyter. . sometimes spelled in English as Durer or Duerer, was a German painter, Old master prin ...

's '' The Praying Hands''.

After the war, Gavin was criticised for the decision to secure the high ground around Groesbeek before attempting the capture of the road

A road is a thoroughfare used primarily for movement of traffic. Roads differ from streets, whose primary use is local access. They also differ from stroads, which combine the features of streets and roads. Most modern roads are paved.

Th ...

and the Nijmegen railway bridge. Browning took responsibility for this, noting that he "personally gave an order to Jim Gavin that, although every effort should be made to effect the capture of the Grave

A grave is a location where a cadaver, dead body (typically that of a human, although sometimes that of an animal) is burial, buried or interred after a funeral. Graves are usually located in special areas set aside for the purpose of buria ...

and Nijmegen bridges as soon as possible, it was essential that he should capture the Groesbeek Ridge and hold it". Gavin's opinion of Browning was uncomplimentary: "There is no doubt that in our system he would have been summarily relieved and sent home in disgrace."

Browning was awarded the Order of ''Polonia Restituta'' (II class) by the Polish government-in-exile

The Polish government-in-exile, officially known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile (), was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Poland of September 1939, and the subsequent Occupation ...

, Order of ''Polonia Restituta'' (II class) but his critical evaluation of the contribution of Polish forces led to the removal of Major-General Stanisław Sosabowski

Stanisław Franciszek Sosabowski (; 8 May 1892 – 25 September 1967) was a Polish general in World War II. He fought in the Polish Campaign of 1939 and at the Battle of Arnhem (Netherlands), as a part of Operation Market Garden, in 1944 as c ...

as commanding officer of the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade

The 1st (Polish) Independent Parachute Brigade was a parachute infantry brigade of the Polish Armed Forces in the West under the command of Major General Stanisław Sosabowski, created in September 1941 during the Second World War and based in ...

. Some writers later claimed that Sosabowski had been made a scapegoat for the failure of Market Garden. Montgomery attached no blame to Browning or any of his subordinates, or indeed acknowledged failure at all. He told Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army (in countries without the rank of Generalissimo), and as such, few persons a ...

Sir Alan Brooke

Field Marshal Alan Francis Brooke, 1st Viscount Alanbrooke (23 July 1883 – 17 June 1963), was a senior officer of the British Army. He was Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), the professional head of the British Army, during the Secon ...

, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff

Chief of the General Staff (CGS) has been the title of the professional head of the British Army since 1964. The CGS is a member of both the Chiefs of Staff Committee and the Army Board; he is also the Chair of the Executive Committee of the A ...

(CIGS), the professional head of the British Army, that he would like Browning to take over VIII Corps in the event that Sir Richard O'Connor, the GOC, was transferred to another theatre

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors to present experiences of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a Stage (theatre), stage. The performe ...

.

South East Asia Command

Events took a different course.

Events took a different course. Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in many navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force. Admiral is ranked above vice admiral and below admiral of ...

Lord Louis Mountbatten, the Supreme Allied Commander, South East Asia Command

South East Asia Command (SEAC) was the body set up to be in overall charge of Allied operations in the South-East Asian Theatre during the Second World War.

History Organisation

The initial supreme commander of the theatre was General Sir ...

(SEAC), had need of a new chief of staff owing to the poor health of Lieutenant-General Henry Pownall. Brooke turned down Mountbatten's initial request for either Lieutenant-General Sir Archibald Nye

Lieutenant-general (United Kingdom), Lieutenant-General Sir Archibald Edward Nye (23 April 1895 – 13 November 1967), was a senior British Army officer who served in both world wars. In the latter he served as Vice Chief of the General Staff (U ...

or Lieutenant-General Sir John Swayne. He then offered Browning for the post, and Mountbatten accepted. Pownall considered that Browning was "excellently qualified" for the post, although Browning had no staff college training and had never held a staff job before. Pownall noted that his "only reservation is that I believe rowningis rather nervy and highly strung". For his services as a corps commander, Browning was mentioned in despatches a second time, and was awarded the Legion of Merit

The Legion of Merit (LOM) is a Awards and decorations of the United States military, military award of the United States Armed Forces that is given for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievemen ...

in the degree of Commander by the United States government

The Federal Government of the United States of America (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the Federation#Federal governments, national government of the United States.

The U.S. federal government is composed of three distinct ...

.

Browning served in South East Asia from December 1944 until July 1946; Mountbatten soon came to regard him as indispensable. Browning had an American deputy, Major-General Horace H. Fuller, and brought staff with him from Europe to SEAC headquarters in Kandy

Kandy (, ; , ) is a major city located in the Central Province, Sri Lanka, Central Province of Sri Lanka. It was the last capital of the Sinhalese monarchy from 1469 to 1818, under the Kingdom of Kandy. The city is situated in the midst of ...

, Ceylon. For his services at SEAC, Browning was created a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding valuable service in a wide range of useful activities. It comprises five classes of awards across both civil and military divisions, the most senior two o ...

on 1 January 1946. His last major military post was as Military Secretary of the War Office from 16 September 1946 to January 1948, although he did not formally retire from the Army until 5 April 1948.

Later life

In January 1948, Browning becameComptroller

A comptroller (pronounced either the same as ''controller'' or as ) is a management-level position responsible for supervising the quality of accountancy, accounting and financial reporting of an organization. A financial comptroller is a senior- ...

and Treasurer

A treasurer is a person responsible for the financial operations of a government, business, or other organization.

Government

The treasury of a country is the department responsible for the country's economy, finance and revenue. The treasure ...

to Her Royal Highness

Royal Highness is a style used to address or refer to some members of royal families, usually princes or princesses. Kings and their female consorts, as well as queens regnant, are usually styled ''Majesty''.

When used as a direct form of add ...

the Princess Elizabeth. This appointment was made on the recommendation of Lord Mountbatten, whose nephew Philip Mountbatten was the Duke of Edinburgh

Duke of Edinburgh, named after the capital city of Scotland, Edinburgh, is a substantive title that has been created four times since 1726 for members of the British royal family. It does not include any territorial landholdings and does not pr ...

. As such, Browning became the head of the Princess' personal staff. Browning also juggled other duties. In 1948 he was involved with the 1948 Summer Olympics

The 1948 Summer Olympics, officially the Games of the XIV Olympiad and officially branded as London 1948, were an international multi-sport event held from 29 July to 14 August 1948 in London, United Kingdom. Following a twelve-year hiatus cau ...

as Deputy Chairman of the British Olympic Association

The British Olympic Association (BOA; ) is the National Olympic Committee for the United Kingdom. It represents the four constituent countries of the United Kingdom (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland), but also incorporate represen ...

, and commandant of the British team. From 1944 to 1962 he was Commodore of the Royal Fowey Yacht Club; on stepping down in 1962, he was elected its first admiral.

Upon the death of King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until Death and state funeral of George VI, his death in 1952 ...

in 1952, the Princess Elizabeth came to the throne as Queen Elizabeth II, and Browning and his staff became redundant, as the Queen was served by the large staff of the monarch. The domestic staff remained at Clarence House

Clarence House is a royal residence on The Mall in the City of Westminster, London. It was built in 1825–1827, adjacent to St James's Palace, for the royal Duke of Clarence, the future King William IV.

The four-storey house is faced in ...

, where they continued to serve the Queen Mother

Elizabeth Angela Marguerite Bowes-Lyon (4 August 1900 – 30 March 2002) was Queen of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 to 6 February 1952 as the wife of King George VI. She was also ...

; the remainder were reorganised as the Office of the Duke of Edinburgh

The Royal Households of the United Kingdom are the collective departments that support members of the British royal family. Many members of the royal family who undertake public duties have separate households. They vary considerably in size, f ...

, with Browning as treasurer, the head of the office, and moved into a new and larger office at Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a royal official residence, residence in London, and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and r ...

. Like the Duke they served, the office had no constitutional role, but supported his sporting, cultural and scientific interests. Browning became involved with the ''Cutty Sark

''Cutty Sark'' is a British clipper ship. Built on the River Leven, Dumbarton, Scotland in 1869 for the Jock Willis Shipping Line, she was one of the last tea clippers to be built and one of the fastest, at the end of a long period of desig ...

'' Trust, set up to preserve the famous ship, and the administration of the Duke of Edinburgh's Award

The Duke of Edinburgh's Award (commonly abbreviated DofE) is a youth awards programme founded in the United Kingdom in 1956 by the Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, which has since expanded to 144 nations. The awards recognise adolescents and ...

. In June 1953, Browning and du Maurier attended the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II

The Coronation of the British monarch, coronation of Elizabeth II as queen of the United Kingdom and the other Commonwealth realms took place on 2 June 1953 at Westminster Abbey in London. Elizabeth acceded to the throne at the age of 25 upon th ...

.

Browning had been drinking

Drinking is the act of ingesting water or other liquids into the body through the mouth, proboscis, or elsewhere. Humans drink by swallowing, completed by peristalsis in the esophagus. The physiological processes of drinking vary widely among ...

since the war, but it now became chronic. This led to a severe nervous breakdown

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness, a mental health condition, or a psychiatric disability, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. A mental disorder is ...

in July 1957, forcing his resignation from his position at the Palace in 1959. Du Maurier had known he had a mistress in Fowey

Fowey ( ; , meaning ''beech trees'') is a port town and civil parishes in England, civil parish at the mouth of the River Fowey in south Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The town has been in existence since well before the Norman invasion, ...

, but his breakdown brought to light two other girlfriends in London. For her part, du Maurier confessed to her own wartime affair. For his services to the Royal Household, Browning was made a Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order

The Royal Victorian Order () is a dynastic order of knighthood established in 1896 by Queen Victoria. It recognises distinguished personal service to the monarch, members of the royal family, or to any viceroy or senior representative of the m ...

in 1953, and was advanced to Knight Grand Cross of the order in 1959. He retreated to Menabilly, the mansion that had inspired du Maurier's novel ''Rebecca

Rebecca () appears in the Hebrew Bible as the wife of Isaac and the mother of Jacob and Esau. According to biblical tradition, Rebecca's father was Bethuel the Aramean from Paddan Aram, also called Aram-Naharaim. Rebecca's brother was Laban (Bi ...

'', which she had leased and restored in 1943. He was appointed a Deputy Lieutenant of Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

in March 1960. Browning caused a scandal in 1963 when, under the influence of prescription drugs and alcohol, he was involved in a car crash in which two people were injured. He was fined £50 () and had to pay court and medical costs. He died from a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when Ischemia, blood flow decreases or stops in one of the coronary arteries of the heart, causing infarction (tissue death) to the heart muscle. The most common symptom ...

at Menabilly on 14 March 1965.

Legacy

Browning was portrayed byDirk Bogarde

Sir Dirk Bogarde (born Derek Jules Gaspard Ulric Niven van den Bogaerde; 28 March 1921 – 8 May 1999) was an English actor, novelist and screenwriter. Initially a matinée idol in films such as ''Doctor in the House (film), Doctor in the Hous ...

in the film '' A Bridge Too Far'', which was based on the events of Operation Market Garden. A copy of Browning's uniform was made to Bogarde's measurements from the original in the Parachute Regiment and Airborne Forces Museum

Airborne Assault – The Museum of the Parachute Regiment and Airborne Forces is based at Duxford in Cambridgeshire and tells the story of the Parachute Regiment (United Kingdom), Parachute Regiment and other airborne forces.

History

The museum ...

. Du Maurier responded angrily to early reports of how Browning was portrayed, and wrote to Mountbatten, urging him to boycott the premiere

A premiere, also spelled première, (from , ) is the debut (first public presentation) of a work, i.e. play, film, dance, musical composition, or even a performer in that work.

History

Raymond F. Betts attributes the introduction of the ...

. He did not do so, explaining that proceeds were going to a charity that he supported. After seeing the film he wrote back that he could find nothing detrimental to Browning in it, and did not think that Browning's reputation had been tarnished. He pointed out that Operation Market Garden was a disaster, and blame had to be shared by those in charge, which included Browning. The Parachute Regiment and Airborne Forces Museum, which opened in 1969, was for many years located in Browning Barracks at Aldershot, which had been built in 1964 and named after him. It remained the depot of the Parachute Regiment and Airborne Forces until 1993. The museum moved to the Imperial War Museum Duxford

Imperial War Museum Duxford, also known as IWM Duxford or simply Duxford, is a branch of the Imperial War Museum near Duxford in Cambridgeshire, England. Duxford, Britain's largest aviation museum, houses exhibits, including nearly 200 aircraf ...

in 2008, and Browning Barracks was sold for housing development.

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

*External links

British Army Officers 1939−1945

, - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Browning, Frederick 1896 births 1965 deaths Academics of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst Airborne warfare Bobsledders at the 1928 Winter Olympics British Army generals of World War II British Army lieutenant generals British Army personnel of World War I British male bobsledders

Frederick Frederick may refer to:

People

* Frederick (given name), the name

Given name

Nobility

= Anhalt-Harzgerode =

* Frederick, Prince of Anhalt-Harzgerode (1613–1670)

= Austria =

* Frederick I, Duke of Austria (Babenberg), Duke of Austria fro ...

Commanders of the Legion of Merit

Companions of the Distinguished Service Order

Companions of the Order of the Bath

Deputy lieutenants of Cornwall

Du Maurier family

Foreign recipients of the Legion of Merit

Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst

Grand Crosses with Star and Sash of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

Grenadier Guards officers

Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire

Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order

Military personnel from the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea

Olympic bobsledders for Great Britain

People educated at Eton College

People educated at West Downs School

People from Kensington

British recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France)

Recipients of the Order of Polonia Restituta