Ford administration on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Republican ticket of President

The Republican ticket of President

Along with the experience of the

Along with the experience of the

Prior to Ford's presidency, the

Prior to Ford's presidency, the

' famous headline "Ford to City: Drop Dead", referring to a speech in which "Ford declared flatly ... that he would veto any bill calling for 'a federal bail-out of New York City. The following month, November 1975, Ford changed his stance and asked Congress to approve federal loans to New York City, upon the condition that the city agree to more austere budgets imposed by Washington, D.C. In December 1975, Ford signed a bill providing New York City with access to $2.3 billion in loans.

Despite his reservations about how the program ultimately would be funded in an era of tight public budgeting, Ford signed the

One of Ford's greatest challenges was dealing with the ongoing Vietnam War. American offensive operations against North Vietnam had ended with the

One of Ford's greatest challenges was dealing with the ongoing Vietnam War. American offensive operations against North Vietnam had ended with the

In 1973,

In 1973,

Ford faced two assassination attempts during his presidency. In

Ford faced two assassination attempts during his presidency. In

Ford made the first major decision of his campaign in mid-1975, when he selected Bo Callaway to run his campaign. The pardon of Nixon and the disastrous 1974 mid-term elections weakened Ford's standing within the party, creating an opening for a competitive Republican primary. The intra-party challenge to Ford came from the conservative wing of the party; many conservative leaders had viewed Ford as insufficiently conservative throughout his political career. Conservative Republicans were further disappointed with the selection of Rockefeller as vice president, and faulted Ford for the fall of Saigon, the amnesty for draft dodgers, and the continuation of détente policies. Ronald Reagan, a leader among the conservatives, launched his campaign in autumn of 1975. Hoping to appease his party's right wing and sap Reagan's momentum, Ford requested that Rockefeller not seek election and the vice president agreed to this request. Ford defeated Reagan in the first several

Ford made the first major decision of his campaign in mid-1975, when he selected Bo Callaway to run his campaign. The pardon of Nixon and the disastrous 1974 mid-term elections weakened Ford's standing within the party, creating an opening for a competitive Republican primary. The intra-party challenge to Ford came from the conservative wing of the party; many conservative leaders had viewed Ford as insufficiently conservative throughout his political career. Conservative Republicans were further disappointed with the selection of Rockefeller as vice president, and faulted Ford for the fall of Saigon, the amnesty for draft dodgers, and the continuation of détente policies. Ronald Reagan, a leader among the conservatives, launched his campaign in autumn of 1975. Hoping to appease his party's right wing and sap Reagan's momentum, Ford requested that Rockefeller not seek election and the vice president agreed to this request. Ford defeated Reagan in the first several

online review

* Conley, Richard S. "Presidential Influence and Minority Party Liaison on Veto Overrides: New Evidence from the Ford Presidency". ''American Politics Research'' 2002 30#1: 34–65. * Congressional Quarterly. ''President Ford : the man and his record'' (1974

online

* Firestone, Bernard J. and Alexej Ugrinsky, eds. ''Gerald R. Ford and the Politics of Post-Watergate America'' (Greenwood, 1992). ISBN 0-313-28009-6. * Francis, Sandra. ''Gerald R. Ford : our thirty-eighth president'' (2009

online

for middle schools * * Greene, John Robert. ''Betty Ford: Candor and Courage in the White House'' (2004)

online

* Hahn, Dan F. "Corrupt rhetoric: President Ford and the Mayaguez affair." ''Communication Quarterly'' 28.2 (1980): 38–43. * Hersey, John. ''Aspects of the Presidency: Truman and Ford in Office'' (1980). * Holzer, Harold. ''The Presidents Vs. the Press: The Endless Battle Between the White House and the Media--from the Founding Fathers to Fake News'' (Dutton, 2020) pp. 287–293

online

* Hoxie, R. Gordon. "Staffing the Ford and Carter Presidencies." ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' 10.3 (1980): 378–401

online

*Hult, Karen M. and Walcott, Charles E. ''Empowering the White House: Governance under Nixon, Ford, and Carter''. University Press of Kansas, 2004. *Jespersen, T. Christopher. "Kissinger, Ford, and Congress: the Very Bitter End in Vietnam". ''Pacific Historical Review'' 2002 71(3): 439–473. Fulltext: in University of California; Swetswise; Jstor and Ebsco *Jespersen, T. Christopher. "The Bitter End and the Lost Chance in Vietnam: Congress, the Ford Administration, and the Battle over Vietnam, 1975–76". ''Diplomatic History'' 2000 24(2): 265–293.

online

* Kaufman, Scott, ed. ''A Companion to Gerald R. Ford and Jimmy Carter'' (2015), a major overview with 30 historiographical essays by scholars

excerpt

* latest full-scale biography * Maynard, Christopher A. "Manufacturing Voter Confidence: a Video Analysis of the American 1976 Presidential and Vice-presidential Debates". ''Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television'' 1997 17#4 : 523–562. * Mieczkowski, Yanek. ''Gerald Ford and the Challenges of the 1970s'' (University Press of Kentucky, 2005). * Moran, Andrew D. "More than a caretaker: The economic policy of Gerald R. Ford." ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' 41#1 (2011): 39–63

Online

* Olmsted, Kathryn. "Reclaiming Executive Power: The Ford Administration's Response to the Intelligence Investigations." ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' 26.3 (1996): 725–737

online

* Parmet, Herbert S. "Gerald R. Ford" in Henry F Graff ed., ''The Presidents: A Reference History'' (3rd ed. 2002) * Reeves, Richard. '' A Ford, Not a Lincoln'' (1975), says Ford was out of his depth. * Rozell, Mark J. ''The press and the Ford presidency'' (University of Michigan Press, 1992). * Schoenebaum, Eleanora. ''Political Profiles: The Nixon/Ford years'' (1979

online

short biographies of over 500 political and national leaders. * Sloan, John W. "Economic policymaking in the Johnson and Ford administrations." ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' 20.1 (1990): 111-12

online

* Swanson, Roger Frank. "The Ford interlude and the US-Canadian relationship." ''American Review of Canadian Studies'' 8.1 (1978): 3–17. * Tobin, Leesa E. "Betty Ford as first lady: A woman for women." ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' 20.4 (1990): 761–767

online

* Ward, P. S. "Ford and Carter: Contrasting Approaches to Environment." ''Journal (Water Pollution Control Federation)'' (1976): 2238–2243

online

* Weidenbaum, Murray. "Regulatory process reform: from Ford to Clinton." ''Regulation'' 20 (1997): 20

online

* Witcover, Jules. ''Marathon: The Pursuit of the Presidency, 1972–1976'' (1977)

online

online

* * * * * * * * * , by speechwriter * , by chief of staff * * by Secretary of State *

Miller Center on the Presidency at U of Virginia

brief articles on Ford and his presidency {{Authority control Ford, Gerald 1970s in the United States 1970s in American politics 1974 establishments in the United States 1977 disestablishments in the United States Cold War history of the United States

Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. (born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was the 38th president of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, Ford assumed the p ...

's tenure as the 38th president of the United States began on August 9, 1974, upon the resignation

Resignation is the formal act of relinquishing or vacating one's office or position. A resignation can occur when a person holding a position gained by election or appointment steps down, but leaving a position upon the expiration of a term, or ...

of President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

, and ended on January 20, 1977. Ford, a Republican from Michigan

Michigan ( ) is a peninsular U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, Upper Midwestern United States. It shares water and land boundaries with Minnesota to the northwest, Wisconsin to the west, ...

, had been appointed vice president

A vice president or vice-president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vi ...

on December 6, 1973, following the resignation of Spiro Agnew

Spiro Theodore Agnew (; November 9, 1918 – September 17, 1996) was the 39th vice president of the United States, serving from 1969 until his resignation in 1973. He is the second of two vice presidents to resign, the first being John C. ...

from that office. Ford was the only person to serve as president without being elected to either the presidency or the vice presidency. His presidency ended following his narrow defeat in the 1976 presidential election to Democrat Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

, after a period of days in office. His 895 day presidency remains the shortest of all U.S. presidents who did not die in office.

Ford took office in the aftermath of the Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the Presidency of Richard Nixon, administration of President Richard Nixon. The scandal began in 1972 and ultimately led to Resignation of Richard Nixon, Nix ...

and in the final stages of the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

, both of which engendered a new disillusion in American political institutions. Ford's first major act upon taking office was to grant a presidential pardon to Nixon for his role in the Watergate scandal, prompting a major backlash to Ford's presidency. He also created a conditional clemency program for Vietnam War draft dodgers.

Much of Ford's focus in domestic policy was on the economy, which experienced a recession

In economics, a recession is a business cycle contraction that occurs when there is a period of broad decline in economic activity. Recessions generally occur when there is a widespread drop in spending (an adverse demand shock). This may be tr ...

during his tenure. After initially promoting a tax increase designed to combat inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the average price of goods and services in terms of money. This increase is measured using a price index, typically a consumer price index (CPI). When the general price level rises, each unit of curre ...

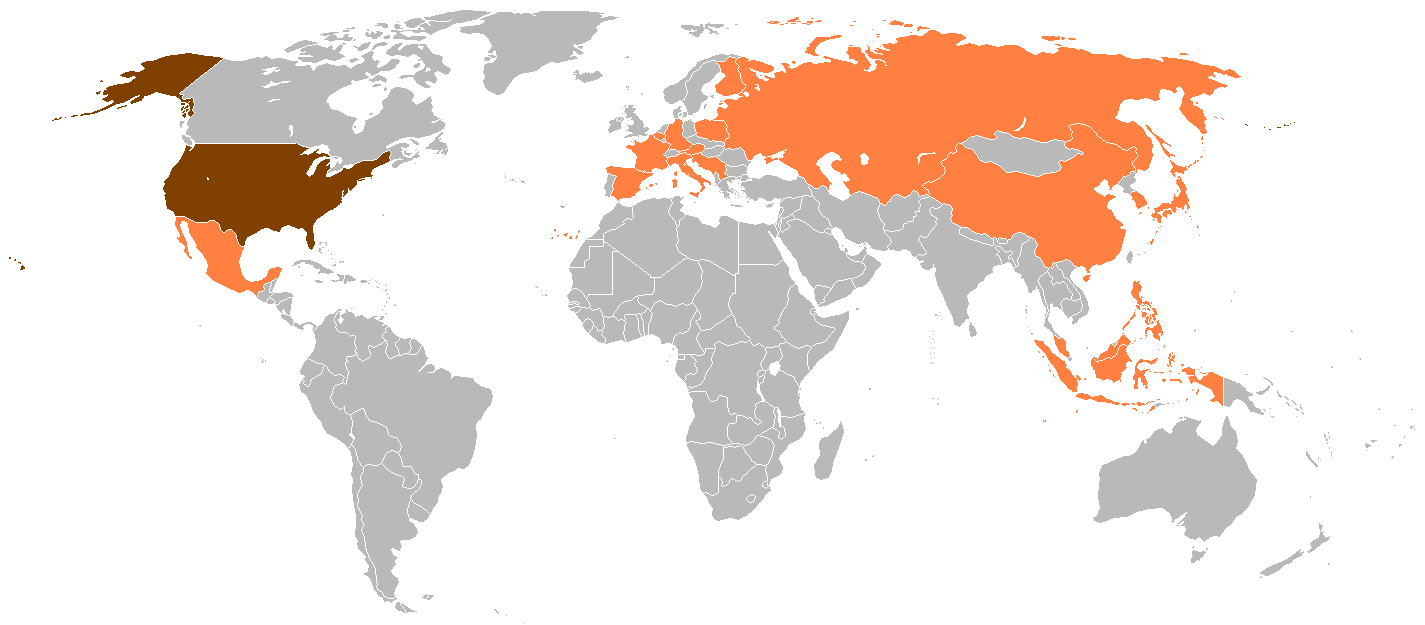

, Ford championed a tax cut designed to rejuvenate the economy, and he signed two tax reduction acts into law. The foreign policy of the Ford administration was characterized in procedural terms by the increased role Congress began to play, and by the corresponding curb on the powers of the president. Overcoming significant congressional opposition, Ford continued Nixon's détente

''Détente'' ( , ; for, fr, , relaxation, paren=left, ) is the relaxation of strained relations, especially political ones, through verbal communication. The diplomacy term originates from around 1912, when France and Germany tried unsucces ...

policies with the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

.

In the 1976 presidential election, Ford was challenged by Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

, a leader of the conservative wing of the Republican Party. After a contentious series of primaries

Primary elections or primaries are elections held to determine which candidates will run in an upcoming general election. In a partisan primary, a political party selects a candidate. Depending on the state and/or party, there may be an "open pri ...

, Ford narrowly won the nomination at the 1976 Republican National Convention

The 1976 Republican National Convention was a United States political convention of the Republican Party that met from August 16 to August 19, 1976, to select the party's nominees for president and vice president. Held in Kemper Arena in Kansa ...

. In the general election, Ford lost to Carter by a narrow margin in the popular and electoral vote. In polls of historians and political scientists, Ford is generally ranked as a below average president, much like both his predecessor and successor.

Accession

The Republican ticket of President

The Republican ticket of President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

and Vice President Spiro Agnew

Spiro Theodore Agnew (; November 9, 1918 – September 17, 1996) was the 39th vice president of the United States, serving from 1969 until his resignation in 1973. He is the second of two vice presidents to resign, the first being John C. ...

won a landslide victory in the 1972 presidential election. Nixon's second term was dominated by the Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the Presidency of Richard Nixon, administration of President Richard Nixon. The scandal began in 1972 and ultimately led to Resignation of Richard Nixon, Nix ...

, which stemmed from a Nixon campaign group's attempted burglary of the Democratic National Committee

The Democratic National Committee (DNC) is the principal executive leadership board of the United States's Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party. According to the party charter, it has "general responsibility for the affairs of the ...

's headquarters and the subsequent cover-up by the Nixon administration. Due to a scandal unrelated to Watergate, Vice President Agnew resigned on October 10, 1973. Under the terms of the Twenty-fifth Amendment, Nixon nominated Ford as Agnew's replacement. Nixon selected Ford, then the House Minority Leader

Party leaders of the United States House of Representatives, also known as floor leaders, are congresspeople who coordinate legislative initiatives and serve as the chief spokespersons for their parties on the House floor. These leaders are el ...

and representative from Michigan's 5th congressional district, largely because he was advised that Ford would be the most easily confirmed of the prominent Republican leaders. Ford was confirmed by overwhelming majorities in both houses of Congress, and he took office as vice president in December 1973.

In the months after his confirmation as vice president, Ford continued to support Nixon's innocence with regards to Watergate, even as evidence mounted that the Nixon administration had ordered the break-in and subsequently sought to cover it up. In July 1974, after the Supreme Court ordered Nixon to turn over recordings of certain meetings he had held as president, the House Judiciary Committee

The U.S. House Committee on the Judiciary, also called the House Judiciary Committee, is a standing committee of the United States House of Representatives. It is charged with overseeing the administration of justice within the federal courts, f ...

voted to begin impeachment proceedings against Nixon. After the tapes became public and clearly showed that Nixon had taken part in the cover-up, Nixon summoned Ford to the Oval Office on August 8, where Nixon informed Ford that he would resign. Nixon formally resigned on August 9, making Ford the first President of the United States who had not been elected as either president or vice president.

Immediately after taking the oath of office in the East Room

The East Room is an event and reception room in the Executive Residence of the White House complex, the home of the president of the United States. The East Room is the largest room in the Executive Residence; it is used for dances, receptions, p ...

of the White House, Ford spoke to the assembled audience in a speech broadcast live to the nation. Ford noted the peculiarity of his position: "I am acutely aware that you have not elected me as your president by your ballots, and so I ask you to confirm me as your president with your prayers." He went on to state:

Administration

Cabinet

Upon assuming office, Ford inherited Nixon's cabinet, although Ford quickly replaced Chief of StaffAlexander Haig

Alexander Meigs Haig Jr. (; 2 December 192420 February 2010) was United States Secretary of State under President Ronald Reagan and White House chief of staff under Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford. Prior to and in between these cabine ...

with Donald Rumsfeld

Donald Henry Rumsfeld (July 9, 1932 – June 29, 2021) was an American politician, businessman, and naval officer who served as United States Secretary of Defense, secretary of defense from 1975 to 1977 under President Gerald Ford, and again ...

, who had served as a Counselor to the President

Counselor to the President is a title used by high-ranking political advisors to the president of the United States and senior members of the White House Office.

The current officeholders are Alina Habba and Peter Navarro. The position should no ...

under Nixon. Rumsfeld and Deputy Chief of Staff Dick Cheney

Richard Bruce Cheney ( ; born January 30, 1941) is an American former politician and businessman who served as the 46th vice president of the United States from 2001 to 2009 under President George W. Bush. He has been called vice presidency o ...

rapidly became among the most influential people in the Ford administration. Ford also appointed Edward H. Levi as Attorney General, charging Levi with cleaning up a Justice Department that had been politicized to unprecedented levels during the Nixon administration. Ford brought in Philip W. Buchen, Robert T. Hartmann, L. William Seidman, and John O. Marsh as senior advisers with cabinet rank. Ford placed a far greater value in his cabinet officials than Nixon had, though cabinet members did not regain the degree of influence they had held prior to World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Levi, Secretary of State and National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (May 27, 1923 – November 29, 2023) was an American diplomat and political scientist who served as the 56th United States secretary of state from 1973 to 1977 and the 7th National Security Advisor (United States), natio ...

, Secretary of the Treasury William E. Simon

William Edward Simon (November 27, 1927 – June 3, 2000) was an American businessman and philanthropist who served as the 63rd United States Secretary of the Treasury. He became the Secretary of the Treasury on May 9, 1974, during the Nixon adm ...

, and Secretary of Defense James R. Schlesinger

James Rodney Schlesinger (February 15, 1929 – March 27, 2014) was an American economist and statesman who was best known for serving as Secretary of Defense from 1973 to 1975 under Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford. Prior to becom ...

all emerged as influential cabinet officials early in Ford's tenure.

Most of the Nixon holdovers in cabinet stayed in place until Ford's dramatic reorganization in the fall of 1975, an action referred to by political commentators as the " Halloween Massacre". Ford appointed George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushBefore the outcome of the 2000 United States presidential election, he was usually referred to simply as "George Bush" but became more commonly known as "George H. W. Bush", "Bush Senior," "Bush 41," and even "Bush th ...

as Director

Director may refer to:

Literature

* ''Director'' (magazine), a British magazine

* ''The Director'' (novel), a 1971 novel by Henry Denker

* ''The Director'' (play), a 2000 play by Nancy Hasty

Music

* Director (band), an Irish rock band

* ''D ...

of the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

, while Rumsfeld became Secretary of Defense and Cheney replaced Rumsfeld as Chief of Staff, becoming the youngest individual to hold that position. The moves were intended to fortify Ford's right flank against a primary challenge from Ronald Reagan. Though Kissinger remained as Secretary of State, Brent Scowcroft

Brent Scowcroft (; March 19, 1925August 6, 2020) was a United States Air Force officer, and a two-time National Security Advisor (United States), United States National Security Advisor, first under U.S. President Gerald Ford and then under Georg ...

replaced Kissinger as National Security Advisor.

Vice presidency

Ford's accession to the presidency left the office of vice president vacant. On August 20, 1974, Ford nominatedNelson Rockefeller

Nelson Aldrich "Rocky" Rockefeller (July 8, 1908 – January 26, 1979) was the 41st vice president of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977 under President Gerald Ford. He was also the 49th governor of New York, serving from 1959 to 197 ...

, the leader of the party's liberal wing, for the vice presidency. Rockefeller and former Representative George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushBefore the outcome of the 2000 United States presidential election, he was usually referred to simply as "George Bush" but became more commonly known as "George H. W. Bush", "Bush Senior," "Bush 41," and even "Bush th ...

from Texas were the two finalists for vice presidential nomination, and Ford chose Rockefeller in part due to a ''Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly news magazine based in New York City. Founded as a weekly print magazine in 1933, it was widely distributed during the 20th century and has had many notable editors-in-chief. It is currently co-owned by Dev P ...

'' report that revealed that Bush had accepted money from a Nixon slush fund

A slush fund is a fund or account used for miscellaneous income and expenses, particularly when these are corrupt or illegal. Such funds may be kept hidden and maintained separately from money that is used for legitimate purposes. Slush funds m ...

during his 1970 Senate campaign. Rockefeller underwent extended hearings before Congress, which caused embarrassment when it was revealed he made large gifts to senior aides, including Kissinger. Although conservative Republicans were not pleased that Rockefeller was picked, most of them voted for his confirmation, and his nomination passed both the House and Senate. He was sworn in as the nation's 41st vice president on December 19, 1974. Prior to Rockefeller's confirmation, Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hung ...

Carl Albert

Carl Bert Albert (May 10, 1908 – February 4, 2000) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 46th speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1971 to 1977 and represented Oklahoma's 3rd congressional district as a ...

was next in line to the presidency. Ford promised to give Rockefeller a major role in shaping the domestic policy of the administration, but Rockefeller was quickly sidelined by Rumsfeld and other administration officials.

Executive Privilege

In the wake of Nixon's heavy use ofexecutive privilege

Executive privilege is the right of the president of the United States and other members of the executive branch to maintain confidential communications under certain circumstances within the executive branch and to resist some subpoenas and ot ...

to block investigations of his actions, Ford was scrupulous in minimizing its usage. However, that complicated his efforts to keep congressional investigations under control. Political scientist Mark J. Rozell concludes that Ford's:

: failure to enunciate a formal executive privilege policy made it more difficult to explain his position to Congress. He concludes that Ford's actions were prudent; they likely salvaged executive privilege from the graveyard of eroded presidential entitlements because of his recognition that the Congress was likely to challenge any presidential use of that unpopular perquisite.

Judicial appointments

Ford made one appointment to theSupreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

while in office, appointing John Paul Stevens

John Paul Stevens (April 20, 1920 – July 16, 2019) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1975 to 2010. At the time of his retirement, he was the second-oldes ...

to succeed Associate Justice

An associate justice or associate judge (or simply associate) is a judicial panel member who is not the chief justice in some jurisdictions. The title "Associate Justice" is used for members of the Supreme Court of the United States and some ...

William O. Douglas

William Orville Douglas (October 16, 1898January 19, 1980) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 to 1975. Douglas was known for his strong progressive and civil libertari ...

. Upon learning of Douglas's impending retirement, Ford asked Attorney General Levi to submit a short list of potential Supreme Court nominees, and Levi suggested Stevens, Solicitor General Robert Bork

Robert Heron Bork (March 1, 1927 – December 19, 2012) was an American legal scholar who served as solicitor general of the United States from 1973 until 1977. A professor by training, he was acting United States Attorney General and a judge on ...

, and federal judge Arlin Adams. Ford chose Stevens, an uncontroversial federal appellate judge, largely because he was likely to face the least opposition in the Senate. Early in his tenure on the Court, Stevens had a relatively moderate voting record, but in the 1990s he emerged as a leader of the Court's liberal bloc. In 2005 Ford wrote, "I am prepared to allow history's judgment of my term in office to rest (if necessary, exclusively) on my nomination 30 years ago of Justice John Paul Stevens to the U.S. Supreme Court". Ford also appointed 11 judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, and 50 judges to the United States district court

The United States district courts are the trial courts of the United States federal judiciary, U.S. federal judiciary. There is one district court for each United States federal judicial district, federal judicial district. Each district cov ...

s.

Domestic affairs

Nixon pardon

Along with the experience of the

Along with the experience of the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

and other issues, Watergate contributed to a decline in the faith that Americans placed in political institutions. Low public confidence added to Ford's already formidable challenge of establishing his own administration without a presidential transition period or the popular mandate of a presidential election. Though Ford became widely popular during his first month in office, he faced a difficult situation regarding the fate of former President Nixon, whose status threatened to undermine the Ford administration. In the final days of Nixon's presidency, Haig had floated the possibility of Ford pardoning Nixon, but no deal had been struck between Nixon and Ford before Nixon's resignation. Nonetheless, when Ford took office, most of the Nixon holdovers in the executive branch, including Haig and Kissinger, pressed for a pardon. Through his first month in office, Ford publicly kept his options open regarding a pardon, but he came to believe that ongoing legal proceedings against Nixon would prevent his administration from addressing any other issue. Ford attempted to extract a public statement of contrition from Nixon before issuing the pardon, but Nixon refused.

On September 8, 1974, Ford issued Proclamation 4311, which gave Nixon a full and unconditional pardon for any crimes he might have committed against the United States while president. In a televised broadcast to the nation, Ford explained that he felt the pardon was in the best interests of the country, and that the Nixon family's situation "is a tragedy in which we all have played a part. It could go on and on and on, or someone must write the end to it. I have concluded that only I can do that, and if I can, I must."

The Nixon pardon was highly controversial, and Gallup polling showed that Ford's approval rating fell from 71 percent before the pardon to 50 percent immediately after the pardon. Critics derided the move and said a "corrupt bargain

In American political jargon, corrupt bargain is a backdoor deal for or involving the U.S. presidency. Three events in particular in American political history have been called the corrupt bargain: the 1824 United States presidential election, ...

" had been struck between the men. In an editorial at the time, ''The New York Times'' stated that the Nixon pardon was a "profoundly unwise, divisive and unjust act" that in a stroke had destroyed the new president's "credibility as a man of judgment, candor and competence". Ford's close friend and press secretary, Jerald terHorst, resigned his post in protest. The pardon would hang over Ford for the remainder of his presidency, and damaged his relationship with members of Congress from both parties. Against the advice of most of his advisers, Ford agreed to appear before a House Subcommittee that requested further information on the pardon. On October 17, 1974, Ford testified before Congress, becoming the first sitting president since Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

to do so.

After Ford left the White House, the former president privately justified his pardon of Nixon by carrying in his wallet a portion of the text of '' Burdick v. United States'', a 1915 Supreme Court decision which stated that a pardon indicated a presumption of guilt, and that acceptance of a pardon was tantamount to a confession of that guilt.

Clemency for draft dodgers

During the Vietnam War, about one percent of American men of eligible age for the draft failed to register, and approximately one percent of those who were drafted refused to serve. Those who refused conscription were labeled as "draft dodger

Conscription evasion or draft evasion (American English) is any successful attempt to elude a government-imposed obligation to serve in the military forces of one's nation. Sometimes draft evasion involves refusing to comply with the military dr ...

s"; many such individuals had left the country for Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

, but others remained in the United States. Ford had opposed any form of amnesty for the draft dodgers while in Congress, but his presidential advisers convinced him that a clemency program would help resolve a contentious issue and boost Ford's public standing. On September 16, 1974, shortly after he announced the Nixon pardon, Ford introduced a presidential clemency program for Vietnam War draft dodgers. The conditions of the clemency required a reaffirmation of allegiance to the United States and two years of work in a public service position. The program for the Return of Vietnam Era Draft Evaders and Military Deserters established a Clemency Board to review the records and make recommendations for receiving a presidential pardon and a change in military discharge

A military discharge is given when a member of the armed forces is released from their obligation to serve. Each country's military has different types of discharge. They are generally based on whether the persons completed their training and the ...

status. Ford's clemency program was accepted by most conservatives, but attacked by those on the left who wanted a full amnesty program. Full pardon for draft dodgers would later come in the Carter Administration

Jimmy Carter's tenure as the List of presidents of the United States, 39th president of the United States began with Inauguration of Jimmy Carter, his inauguration on January 20, 1977, and ended on January 20, 1981. Carter, a Democratic Party ...

.

1974 midterm elections

The 1974 congressional midterm elections took place less than three months after Ford assumed office. The Democratic Party turned voter dissatisfaction into large gains in the House of Representatives elections, taking 49 seats from the Republican Party, increasing their majority to 291 of the 435 seats. Even Ford's former House seat was won by a Democrat. In the Senate elections, the Democrats increased their majority to 61 seats in the 100-seat body. The subsequent 94th Congress would override the highest percentage of vetoes sinceAndrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. The 16th vice president, he assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a South ...

served as president in the 1860s. Ford's successful vetoes, however, resulted in the lowest yearly spending increases since the Eisenhower administration. Buoyed by the new class of " Watergate Babies," liberal Democrats implemented reforms designed to ease the passage of legislation. The House began to select committee

A committee or commission is a body of one or more persons subordinate to a deliberative assembly or other form of organization. A committee may not itself be considered to be a form of assembly or a decision-making body. Usually, an assembly o ...

chairs by secret ballot rather than through seniority, resulting in the removal of some conservative Southern committee chairs. The Senate, meanwhile, lowered the number of votes necessary to end a filibuster

A filibuster is a political procedure in which one or more members of a legislative body prolong debate on proposed legislation so as to delay or entirely prevent a decision. It is sometimes referred to as "talking a bill to death" or "talking ...

from 67 to 60.

Ford was at odds with the liberal Democratic majority in Congress during his presidency, as he reflected in his autobiography:

Economy

By the time Ford took office, the U.S.economy

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

had entered into a period of stagflation

Stagflation is the combination of high inflation, stagnant economic growth, and elevated unemployment. The term ''stagflation'', a portmanteau of "stagnation" and "inflation," was popularized, and probably coined, by British politician Iain Mac ...

, which economists attributed to various causes, including the 1973 oil crisis

In October 1973, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) announced that it was implementing a total oil embargo against countries that had supported Israel at any point during the 1973 Yom Kippur War, which began after Eg ...

and increasing competition from countries such as Japan. Stagflation confounded the traditional economic theories of the 1970s, as economists generally believed that an economy would not simultaneously experience inflation and low rates of economic growth. Traditional economic remedies for a dismal economic growth rate, such as tax cuts and increased spending, risked exacerbating inflation. The conventional response to inflation, tax increases and a cut in government spending, risked damaging the economy. The economic troubles, which signaled the end of the post-war boom

A post-war or postwar period is the interval immediately following the end of a war. The term usually refers to a varying period of time after World War II, which ended in 1945. A post-war period can become an interwar period or interbellum, w ...

, created an opening for a challenge to the dominant Keynesian economics

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomics, macroeconomic theories and Economic model, models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongl ...

, and laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

advocates such as Alan Greenspan

Alan Greenspan (born March 6, 1926) is an American economist who served as the 13th chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1987 to 2006. He worked as a private adviser and provided consulting for firms through his company, Greenspan Associates L ...

acquired influence within the Ford administration. Ford seized the initiative, abandoned 40 years of orthodoxy, and introduced a new conservative economic agenda as he sought to adapt traditional Republican economics to deal with the novel economic challenges.

At the time that he took office, Ford believed that inflation, rather than a potential recession, represented the greatest threat to the economy. He believed that inflation could be reduced, not by reducing the amount of new currency entering circulation, but by encouraging people to reduce their spending. In October 1974, Ford went before the American public and asked them to "Whip Inflation Now". As part of this program, he urged people to wear " WIN" buttons. To try to mesh service and sacrifice, "WIN" called for Americans to reduce their spending and consumption, especially with regards to gasoline

Gasoline ( North American English) or petrol ( Commonwealth English) is a petrochemical product characterized as a transparent, yellowish, and flammable liquid normally used as a fuel for spark-ignited internal combustion engines. When for ...

. Ford hoped that the public would respond to this call for self-restraint much as it had to President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

's calls for sacrifice during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, but the public received WIN with skepticism. At roughly the same time he rolled out WIN, Ford also proposed a ten-point economic plan. The central plank of the plan was a tax increase on corporations and high earners, which Ford hoped would both quell inflation and cut into government's budget deficit.Brinkley, pp. 77–78

Ford's economic focus changed as the country sank into the worst recession since the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

. In November 1974, Ford withdrew his proposed tax increase. Two months later, Ford proposed a 1-year tax reduction of $16 billion to stimulate economic growth, along with spending cuts to avoid inflation.Crain, Andrew Downer. ''The Ford Presidency''. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009 Having switched from advocating for a tax increase to advocating a tax reduction in just two months, Ford was greatly criticized for his "flip-flop". Congress responded by passing a plan that implemented deeper tax cuts and an increase in government spending. Ford seriously considered vetoing the bill, but ultimately chose to sign the Tax Reduction Act of 1975

The United States Tax Reduction Act of 1975 provided a 10-percent rebate on 1974 tax liability ($200 cap). It created a temporary $30 general tax credit for each taxpayer and dependent.

It started the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which, at ...

into law. In October 1975, Ford introduced a bill designed to combat inflation through a mix of tax and spending cuts. That December, Ford signed the Revenue Adjustment Act of 1975, which implemented tax and spending cuts, albeit not at the levels proposed by Ford. The economy recovered in 1976, as both inflation and unemployment declined. Nonetheless, by late 1976 Ford faced considerable discontent over his handling of the economy, and the government had a $74 billion deficit.

Rockefeller Commission

Prior to Ford's presidency, the

Prior to Ford's presidency, the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

(CIA) had illegally assembled files on domestic anti-war activists. In the aftermath of Watergate, CIA Director William Colby put together a report of all of the CIA's domestic activities, and much of the report became public, beginning with the publication of a December 1974 article by investigative journalist Seymour Hersh

Seymour Myron Hersh (born April 8, 1937) is an American investigative journalist and political writer. He gained recognition in 1969 for exposing the My Lai massacre and its cover-up during the Vietnam War, for which he received the 1970 Pulitzer ...

. The revelations sparked outrage among the public and members of Congress. In response to growing pressure to investigate and reform the CIA, Ford created the Rockefeller Commission

The United States President's Commission on CIA Activities within the United States was ordained by President Gerald Ford in 1975 to investigate the activities of the Central Intelligence Agency and other intelligence agencies within the United St ...

. The Rockefeller Commission marked the first time that a presidential commission was established to investigate the national security apparatus. The Rockefeller Commission's report, submitted in June 1975, generally defended the CIA, although it did note that "the CIA has engaged in some activities that should be criticized and not permitted to happen again." The press strongly criticized the commission for failing to include a section on the CIA's assassination plots. The Senate created its own committee, led by Senator Frank Church, to investigate CIA abuses. Ford feared that the Church Committee

The Church Committee (formally the United States Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities) was a US Senate select committee in 1975 that investigated abuses by the Central Intelligence ...

would be used for partisan purposes and resisted turning over classified materials, but Colby cooperated with the committee. In response to the Church Committee's report, both houses of Congress established select committees to provide oversight to the intelligence community.

Environment

Due to the frustration of environmentalists left over from the Nixon days, includingEnvironmental Protection Agency

Environmental Protection Agency may refer to the following government organizations:

* Environmental Protection Agency (Queensland), Australia

* Environmental Protection Agency (Ghana)

* Environmental Protection Agency (Ireland)

* Environmenta ...

head Russell E. Train, environmentalism was a peripheral issue during the Ford years. Secretary of the Interior Thomas S. Kleppe was a leader of the " Sagebrush Rebellion", a movement of western ranchers and other groups that sought the repeal of environmental protections on federal land. They lost repeatedly in the federal courts, most notably in the 1976 Supreme Court decision of '' Kleppe v. New Mexico''. Ford's successes included the addition of two national monuments, six historical sites, three historic parks and two national preserves. None were controversial. In the international field, treaties and agreements with Canada, Mexico, China, Japan, the Soviet Union and several European countries included provisions to protect endangered species.

Social issues

Ford and his wife were outspoken supporters of theEqual Rights Amendment

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) was a proposed amendment to the Constitution of the United States, United States Constitution that would explicitly prohibit sex discrimination. It is not currently a part of the Constitution, though its Ratifi ...

(ERA), a proposed constitutional amendment that had been submitted to the states for ratification in 1972. The ERA was designed to ensure equal rights for all citizens regardless of gender. Despite Ford's support, the ERA would fail to win ratification by the necessary number of state legislatures.

As president, Ford's position on abortion

Abortion is the early termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. Abortions that occur without intervention are known as miscarriages or "spontaneous abortions", and occur in roughly 30–40% of all pregnan ...

was that he supported "a federal constitutional amendment that would permit each one of the 50 States to make the choice". This had also been his position as House Minority Leader in response to the 1973 Supreme Court case of ''Roe v. Wade

''Roe v. Wade'', 410 U.S. 113 (1973),. was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Constitution of the United States protected the right to have an ...

'', which he opposed. Ford came under criticism for a ''60 Minutes'' interview his wife Betty gave in 1975, in which she stated that ''Roe v. Wade'' was a "great, great decision". During his later life, Ford would identify as pro-choice

Abortion-rights movements, also self-styled as pro-choice movements, are movements that advocate for legal access to induced abortion services, including elective abortion. They seek to represent and support women who wish to terminate their ...

.

Campaign finance

After the 1972 elections,good government

Good governance is the process of measuring how public institutions conduct public affairs and manage public resources and guarantee the realization of human rights in a manner essentially free of abuse and corruption and with due regard for the ...

groups like Common Cause

Common Cause is a watchdog group based in Washington, D.C., with chapters in 35 states. It was founded in 1970 by John W. Gardner, a Republican, who was the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare in the administration of President Lyndon ...

pressured Congress to amend campaign finance law to restrict the role of money in political campaigns. In 1974, Congress approved amendments to the Federal Election Campaign Act

The Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 (FECA, , ''et seq.'') is the primary United States federal law regulating political campaign fundraising and spending. The law originally focused on creating limits for campaign spending on communicati ...

, establishing the Federal Election Commission

The Federal Election Commission (FEC) is an independent agency of the United States government that enforces U.S. campaign finance laws and oversees U.S. federal elections. Created in 1974 through amendments to the Federal Election Campaign ...

to oversee campaign finance laws. The amendments also established a system of public financing for presidential elections, limited the size of campaign contributions, limited the amount of money that candidates could spend on their own campaigns, and required the disclosure of nearly all campaign contributions. Ford reluctantly signed the bill into law in October 1974. In the 1976 case of ''Buckley v. Valeo

''Buckley v. Valeo'', 424 U.S. 1 (1976), was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court on campaign finance in the United States, campaign finance. A majority of justices held that, as pro ...

'', the Supreme Court overturned the cap on self-funding by political candidates, holding that such a restriction violated freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been r ...

rights. The campaign finance reforms of the 1970s were largely unsuccessful in lessening the influence of money in politics, as more contributions shifted to political action committee

In the United States, a political action committee (PAC) is a tax-exempt 527 organization that pools campaign contributions from members and donates those funds to campaigns for or against candidates, ballot initiatives, or legislation. The l ...

s and state and local party committees.

Court ordered busing to desegregate public schools

In 1971, the United States Supreme Court ruled in '' Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education'' that "Busing was a permissible tool for desegregation purposes." However, in the closing days of the Nixon administration, the Supreme Court largely eliminated District Court ability to order busing across city and suburban systems in the case of '' Milliken v. Bradley.'' It meant that disgruntled white families could move to the suburbs and not be reached by court orders regarding segregation of the central city schools. Ford, representing a Michigan district, had always taken the position in favor of the goal of school desegregation but opposition to court-ordered forced busing as a means of achieving it. In the first major bill he signed as president, Ford's compromise solution was to win over the general population with mild anti-busing legislation. He condemned anti-busing violence, promoted the theoretical goal of school desegregation, and promised to uphold the Constitution. The problem did not go away – it only escalated and remained on the front burner for years. Tension exploded in Boston, where working-class Irish neighborhoods inside the city limits violently resisted court-ordered busing of black children into their schools.Other domestic issues

When New York City faced bankruptcy in 1975,Mayor

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a Municipal corporation, municipal government such as that of a city or a town. Worldwide, there is a wide variance in local laws and customs regarding the powers and responsibilitie ...

Abraham Beame was unsuccessful in obtaining Ford's support for a federal bailout. The incident prompted the New York '' Daily News''Education for All Handicapped Children Act

The Education for All Handicapped Children Act (sometimes referred to using the acronyms EAHCA or EHA, or Public Law (PL) 94-142) was enacted by the United States Congress in 1975. This act required all public schools accepting federal funds to ...

of 1975, which established special education

Special education (also known as special-needs education, aided education, alternative provision, exceptional student education, special ed., SDC, and SPED) is the practice of educating students in a way that accommodates their individual di ...

throughout the United States. Ford expressed "strong support for full educational opportunities for our handicapped children" upon signing the bill.

Ford was confronted with a potential swine flu pandemic

A pandemic ( ) is an epidemic of an infectious disease that has a sudden increase in cases and spreads across a large region, for instance multiple continents or worldwide, affecting a substantial number of individuals. Widespread endemic (epi ...

. In the early 1970s, an influenza

Influenza, commonly known as the flu, is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These sympto ...

strain H1N1

Influenza A virus subtype H1N1 (A/H1N1) is a subtype of influenza A virus (IAV). Some human-adapted strains of H1N1 are endemic in humans and are one cause of seasonal influenza (flu). Other strains of H1N1 are endemic in pigs ( swine influen ...

shifted from a form of flu that affected primarily pigs and crossed over to humans. On February 5, 1976, an army

An army, ground force or land force is an armed force that fights primarily on land. In the broadest sense, it is the land-based military branch, service branch or armed service of a nation or country. It may also include aviation assets by ...

recruit at Fort Dix

Fort Dix, the common name for the Army Support Activity (ASA) located at Joint Base McGuire–Dix–Lakehurst, is a United States Army post. It is located south-southeast of Trenton, New Jersey. Fort Dix is under the jurisdiction of the Air Fo ...

mysteriously died and four fellow soldiers were hospitalized; health officials

Health has a variety of definitions, which have been used for different purposes over time. In general, it refers to physical and emotional well-being, especially that associated with normal functioning of the human body, absent of disease, pain ...

announced that "swine flu" was the cause. Soon after, public health officials in the Ford administration urged that every person in the United States be vaccinated

A vaccine is a biological Dosage form, preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease, infectious or cancer, malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verifi ...

. Although the vaccination program was plagued by delays and public relations problems, some 25% of the population was vaccinated by the time the program was canceled in December 1976. The vaccine was alleged to have been a factor in twenty-five deaths.

Foreign affairs

Cold War

Ford continued Nixon'sdétente

''Détente'' ( , ; for, fr, , relaxation, paren=left, ) is the relaxation of strained relations, especially political ones, through verbal communication. The diplomacy term originates from around 1912, when France and Germany tried unsucces ...

policy with both the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and China, easing the tensions of the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

. In doing so, he overcame opposition from members of Congress, an institution which became increasingly assertive in foreign affairs in the early 1970s. This opposition was led by Senator Henry M. Jackson

Henry Martin "Scoop" Jackson (May 31, 1912 – September 1, 1983) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a U.S. representative (1941–1953) and U.S. senator (1953–1983) from the state of Washington (state), Washington. A Cold W ...

, who scuttled a U.S.–Soviet trade agreement by winning passage of the Jackson–Vanik amendment

The Jackson–Vanik amendment to the Trade Act of 1974 is a 1974 provision in United States federal law intended to affect U.S. trade relations with countries with non-market economies (originally, countries of the Soviet Bloc) that restrict freed ...

. The thawing relationship with China brought about by Nixon's 1972 visit to China was reinforced with another presidential visit in December 1975.

Despite the collapse of the trade agreement with the Soviet Union, Ford and Soviet Leader Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev (19 December 190610 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964 until Death and state funeral of Leonid Brezhnev, his death in 1982 as w ...

continued the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks

The Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) were two rounds of bilateral conferences and corresponding international treaties involving the United States and the Soviet Union. The Cold War superpowers dealt with arms control in two rounds of ...

, which had begun under Nixon. In 1972, the U.S. and the Soviet Union had reached the SALT I treaty, which placed upper limits on each power's nuclear arsenal. Ford met Brezhnev at the November 1974 Vladivostok Summit, at which point the two leaders agreed to a framework for another SALT treaty. Opponents of détente, led by Jackson, delayed Senate consideration of the treaty until after Ford left office.

Helsinki Accords

When Ford took office in August 1974, the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) negotiations had been underway inHelsinki, Finland

Helsinki () is the capital and most populous city in Finland. It is on the shore of the Gulf of Finland and is the seat of southern Finland's Uusimaa region. About people live in the municipality, with million in the capital region and ...

, for nearly two years. Throughout much of the negotiations, U.S. leaders were disengaged and uninterested with the process; Kissinger told Ford in 1974 that "we never wanted it but we went along with the Europeans ... is meaningless—it is just a grandstand play to the left. We are going along with it." In the months leading up to the conclusion of negotiations and signing of the Helsinki Final Act in August 1975, Americans of Eastern European descent voiced their concerns that the agreement would mean the acceptance of Soviet domination over Eastern Europe and the permanent incorporation of the Baltic states

The Baltic states or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term encompassing Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone, and the OECD. The three sovereign states on the eastern co ...

into the USSR. Shortly before President Ford departed for Helsinki, he held a meeting with a delegation of Americans of Eastern European background, and stated definitively that U.S. policy on the Baltic States would not change, but would be strengthened since the agreement denies the annexation of territory in violation of international law and allows for the peaceful change of borders.

The American public remained unconvinced that American policy on the incorporation of the Baltic States would not be changed by the Helsinki Final Act. Despite protests from all around, Ford decided to move forward and sign the Helsinki Agreement. As domestic criticism mounted, Ford hedged on his support for the Helsinki Accords, which had the impact of overall weakening his foreign-policy stature. Though Ford was criticized for his apparent recognition of the Soviet domination of Eastern Europe, the new emphasis on human rights would eventually contribute to the weakening of the Eastern bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc (Combloc), the Socialist Bloc, the Workers Bloc, and the Soviet Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America that were a ...

in the 1980s and speed up its collapse in 1989.

Vietnam

One of Ford's greatest challenges was dealing with the ongoing Vietnam War. American offensive operations against North Vietnam had ended with the

One of Ford's greatest challenges was dealing with the ongoing Vietnam War. American offensive operations against North Vietnam had ended with the Paris Peace Accords

The Paris Peace Accords (), officially the Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Viet Nam (), was a peace agreement signed on January 27, 1973, to establish peace in Vietnam and end the Vietnam War. It took effect at 8:00 the follo ...

, signed on January 27, 1973. The accords declared a cease fire across both North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

and South Vietnam

South Vietnam, officially the Republic of Vietnam (RVN; , VNCH), was a country in Southeast Asia that existed from 1955 to 1975. It first garnered Diplomatic recognition, international recognition in 1949 as the State of Vietnam within the ...

, and required the release of American prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

. The agreement guaranteed the territorial integrity of Vietnam and, like the Geneva Conference of 1954, called for national elections in the North and South. South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu was not involved in the final negotiations, and publicly criticized the proposed agreement, but was pressured by Nixon and Kissinger into signing the agreement. In multiple letters to the South Vietnamese president, Nixon had promised that the United States would defend Thieu's government, should the North Vietnamese violate the accords.Brinkley, 89–98

Fighting in Vietnam continued after the withdrawal of most U.S. forces in early 1973. As North Vietnamese forces advanced in early 1975, Ford requested Congress approve a $722 million aid package for South Vietnam, funds that had been promised by the Nixon administration. Congress voted against the proposal by a wide margin. Senator Jacob K. Javits offered "...large sums for evacuation, but not one nickel for military aid". Thieu resigned on April 21, 1975, publicly blaming the lack of support from the United States for the fall of his country. Two days later, on April 23, Ford gave a speech at Tulane University

The Tulane University of Louisiana (commonly referred to as Tulane University) is a private research university in New Orleans, Louisiana, United States. Founded as the Medical College of Louisiana in 1834 by a cohort of medical doctors, it b ...

, announcing that the Vietnam War was over "...as far as America is concerned".

With the North Vietnamese forces advancing on the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon

Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) ('','' TP.HCM; ), commonly known as Saigon (; ), is the most populous city in Vietnam with a population of around 14 million in 2025.

The city's geography is defined by rivers and canals, of which the largest is Saigo ...

, Ford ordered the evacuation of U.S. personnel, while also allowing U.S. forces to aid others who wished to escape from the Communist advance. Forty thousand U.S. citizens and South Vietnamese were evacuated by plane until enemy attacks made further such evacuations impossible. In Operation Frequent Wind

Operation Frequent Wind was the final phase in the evacuation of American civilians and "at-risk" Vietnamese from Saigon, South Vietnam, before the takeover of the city by the North Vietnamese People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) in the Fall of Sai ...

, the final phase of the evacuation preceding the fall of Saigon

The fall of Saigon, known in Vietnam as Reunification Day (), was the capture of Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam, by North Vietnam on 30 April 1975. As part of the 1975 spring offensive, this decisive event led to the collapse of the So ...

on April 30, military and Air America helicopters took evacuees to off-shore U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest displacement, at 4.5 million tons in 2021. It has the world's largest aircraft ...

vessels. During the operation, so many South Vietnamese helicopters landed on the vessels taking the evacuees that some were pushed overboard to make room for more people.

The Vietnam War, which had raged since the 1950s, finally came to an end with the Fall of Saigon, and Vietnam was reunified into one country. Many of the Vietnamese evacuees were allowed to enter the United States under the Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act. The 1975 act appropriated $455 million toward the costs of assisting the settlement of Indochinese refugees. In all, 130,000 Vietnamese refugees came to the United States in 1975. Thousands more escaped in the years that followed. Following the end of the war, Ford expanded the embargo of North Vietnam to cover all of Vietnam, blocked Vietnam's accession to the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

, and refused to establish full diplomatic relations.

Mayaguez and Panmunjom

North Vietnam's victory over the South led to a considerable shift in the political winds in Asia, and Ford administration officials worried about a consequent loss of U.S. influence in the region. The administration proved it was willing to respond forcefully to challenges to its interests in the region whenKhmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge is the name that was popularly given to members of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK), and by extension to Democratic Kampuchea, which ruled Cambodia between 1975 and 1979. The name was coined in the 1960s by Norodom Sihano ...

forces seized an American ship in international waters

The terms international waters or transboundary waters apply where any of the following types of bodies of water (or their drainage basins) transcend international boundaries: oceans, large marine ecosystems, enclosed or semi-enclosed region ...

.

In May 1975, shortly after the fall of Saigon and the Khmer Rouge conquest of Cambodia

Cambodia, officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. It is bordered by Thailand to the northwest, Laos to the north, and Vietnam to the east, and has a coastline ...

, Cambodians seized the American merchant ship ''Mayaguez'' in international waters, sparking the Mayaguez incident

The ''Mayaguez'' incident took place between Democratic Kampuchea, Kampuchea (now Cambodia) and the United States from 12 to 15 May 1975, less than a month after the Khmer Rouge took Fall of Phnom Penh, control of the capital Phnom Penh ousting ...

. Ford dispatched Marines

Marines (or naval infantry) are military personnel generally trained to operate on both land and sea, with a particular focus on amphibious warfare. Historically, the main tasks undertaken by marines have included Raid (military), raiding ashor ...

to rescue the crew from an island where the crew was believed to be held, but the Marines met unexpectedly stiff resistance just as, unknown to the U.S., the crew were being released. In the operation, three military transport helicopters were shot down and 41 U.S. servicemen were killed and 50 wounded while approximately 60 Khmer Rouge soldiers were killed. Despite American losses, the rescue operation proved to be a boon to Ford's poll numbers; Senator Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and major general in the United States Air Force, Air Force Reserve who served as a United States senator from 1953 to 1965 and 1969 to 1987, and was the Re ...

declared that the operation "shows we've still got balls in this country." Some historians have argued that the Ford administration felt the need to respond forcefully to the incident because it was construed as a Soviet plot. But work by Andrew Gawthorpe, published in 2009, based on an analysis of the administration's internal discussions, shows that Ford's national security team understood that the seizure of the vessel was a local, and perhaps even accidental, provocation by an immature Khmer government. Nevertheless, they felt the need to respond forcefully to discourage further provocations by other Communist countries in Asia.

Middle East

In the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean, two ongoing international disputes developed into crises during Ford's presidency. TheCyprus dispute

The Cyprus problem, also known as the Cyprus conflict, Cyprus issue, Cyprus dispute, or Cyprus question, is an ongoing dispute between the Greek Cypriot and the Turkish Cypriot community in the north of the island of Cyprus, where troops of t ...

turned into a crisis with the 1974 Turkish invasion of Cyprus

The Turkish invasion of Cyprus began on 20 July 1974 and progressed in two phases over the following month. Taking place upon a background of Cypriot intercommunal violence, intercommunal violence between Greek Cypriots, Greek and Turkish Cy ...

, which took place following the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

-backed 1974 Cypriot coup d'état

Major events in 1974 include the aftermath of the 1973 oil crisis and the resignation of President of the United States, United States President Richard Nixon following the Watergate scandal. In the Middle East, the aftermath of the 1973 Yom ...

. The dispute put the United States in a difficult position as both Greece and Turkey were members of NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

. In mid-August, the Greek government

The Government of Greece (Greek language, Greek: Κυβέρνηση της Ελλάδας), officially the Government of the Hellenic Republic (Κυβέρνηση της Ελληνικής Δημοκρατίας) is the collective body of the Gre ...

withdrew Greece from the NATO military structure; in mid-September 1974, the Senate and House of Representatives overwhelmingly voted to halt military aid to Turkey. Ford vetoed the bill due to concerns regarding its effect on Turkish-American relations and the deterioration of security on NATO's eastern front. A second bill was then passed by Congress, which Ford also vetoed, although a compromise was accepted to continue aid until the end of the year. As Ford expected, Turkish relations were considerably disrupted until 1978.

In 1973,

In 1973, Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

and Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

had launched a joint surprise attack against Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

, seeking to re-take land lost in the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War, also known as the June War, 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states, primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, Syria, and Jordan from 5 to 10June ...

of 1967. However, early Arab success gave way to an Israel military victory in what became known as the Yom Kippur War

The Yom Kippur War, also known as the Ramadan War, the October War, the 1973 Arab–Israeli War, or the Fourth Arab–Israeli War, was fought from 6 to 25 October 1973 between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states led by Egypt and S ...

. Although an initial cease fire

A ceasefire (also known as a truce), also spelled cease-fire (the antonym of 'open fire'), is a stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions often due to mediation by a third party. Ceasefires may be ...

had been implemented to end active conflict in the Yom Kippur War, Kissinger's continuing shuttle diplomacy

In diplomacy and international relations, shuttle diplomacy is the action of an outside party in serving as an intermediary between (or among) principals in a dispute, without direct principal-to-principal contact. Originally and usually, the proce ...

was showing little progress. Ford disliked what he saw as Israeli "stalling" on a peace agreement, and wrote, " sraelitactics frustrated the Egyptians and made me mad as hell." During Kissinger's shuttle to Israel in early March 1975, a last minute reversal to consider further withdrawal, prompted a cable from Ford to Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin

Yitzhak Rabin (; , ; 1 March 1922 – 4 November 1995) was an Israeli politician, statesman and general. He was the prime minister of Israel, serving two terms in office, 1974–1977, and from 1992 until Assassination of Yitzhak Rabin, his ass ...

, which included:

On March 24, Ford informed congressional leaders of both parties of the reassessment of the administration policies in the Middle East. "Reassessment", in practical terms, meant canceling or suspending further aid to Israel. For six months between March and September 1975, the United States refused to conclude any new arms agreements with Israel. Rabin notes it was "an innocent-sounding term that heralded one of the worst periods in American-Israeli relations". The announced reassessments upset many American supporters of Israel. On May 21, Ford "experienced a real shock" when seventy-six U.S. senators wrote him a letter urging him to be "responsive" to Israel's request for $2.59 billion in military and economic aid. Ford felt truly annoyed and thought the chance for peace was jeopardized. It was, since the September 1974 ban on arms to Turkey, the second major congressional intrusion upon the President's foreign policy prerogatives. The following summer months were described by Ford as an American-Israeli "war of nerves" or "test of wills". After much bargaining, the Sinai Interim Agreement

The Sinai Interim Agreement, also known as the Sinai II Agreement, was a diplomatic agreement signed by Egypt and Israel on September 4, 1975, with the intention of peacefully resolving territorial disputes. The signing ceremony took place in Gene ...

(Sinai II) between Egypt and Israel was formally signed, and aid resumed.

Angola

A civil war broke out inAngola

Angola, officially the Republic of Angola, is a country on the west-Central Africa, central coast of Southern Africa. It is the second-largest Portuguese-speaking world, Portuguese-speaking (Lusophone) country in both total area and List of c ...

after the fledgling African nation gained independence from Portugal