Evolution Of Tetrapods on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The evolution of tetrapods began about 400 million years ago in the

The evolution of tetrapods began about 400 million years ago in the

It is also one of the best understood, largely thanks to a number of significant

The relatives of ''Kenichthys'' soon established themselves in the waterways and brackish estuaries and became the most numerous of the bony fishes throughout the Devonian and most of the

The relatives of ''Kenichthys'' soon established themselves in the waterways and brackish estuaries and became the most numerous of the bony fishes throughout the Devonian and most of the

The oldest known tetrapodomorph is ''

The oldest known tetrapodomorph is ''

These earliest tetrapods were not terrestrial. The earliest confirmed terrestrial forms are known from the early

These earliest tetrapods were not terrestrial. The earliest confirmed terrestrial forms are known from the early

Devonian Period

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era during the Phanerozoic eon, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the preceding Silurian period at million years ago ( Ma), to the beginning of the succeeding C ...

with the earliest tetrapod

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek :wiktionary:τετρα-#Ancient Greek, τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and :wiktionary:πούς#Ancient Greek, πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four-Limb (anatomy), limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetr ...

s evolved from lobe-finned fishes. Tetrapods (under the apomorphy

In phylogenetics, an apomorphy (or derived trait) is a novel Phenotypic trait, character or character state that has evolution, evolved from its ancestral form (or Plesiomorphy and symplesiomorphy, plesiomorphy). A synapomorphy is an apomorphy sh ...

-based definition used on this page) are categorized as animals in the biological superclass Tetrapoda, which includes all living and extinct amphibian

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

s, reptile

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology), orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocepha ...

s, bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s, and mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s. While most species today are terrestrial, little evidence supports the idea that any of the earliest tetrapods could move about on land, as their limbs could not have held their midsections off the ground and the known trackways do not indicate they dragged their bellies around. Presumably, the tracks were made by animals walking along the bottoms of shallow bodies of water. The specific aquatic ancestors of the tetrapods, and the process by which land colonization occurred, remain unclear. They are areas of active research and debate among palaeontologists at present.

Most amphibians today remain semiaquatic, living the first stage of their lives as fish-like tadpole

A tadpole or polliwog (also spelled pollywog) is the Larva, larval stage in the biological life cycle of an amphibian. Most tadpoles are fully Aquatic animal, aquatic, though some species of amphibians have tadpoles that are terrestrial animal, ...

s. Several groups of tetrapods, such as the snakes

Snakes are elongated Limbless vertebrate, limbless reptiles of the suborder Serpentes (). Cladistically Squamata, squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping Scale (zoology), scales much like other members of ...

and cetaceans

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively c ...

, have lost some or all of their limbs. In addition, many tetrapods have returned to partially aquatic or fully aquatic lives throughout the history of the group (modern examples of fully aquatic tetrapods include cetaceans and sirenian

The Sirenia (), commonly referred to as sea cows or sirenians, are an order of fully aquatic, herbivorous mammals that inhabit swamps, rivers, estuaries, marine wetlands, and coastal marine waters. The extant Sirenia comprise two distinct famili ...

s). The first returns to an aquatic lifestyle may have occurred as early as the Carboniferous Period

The Carboniferous ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Permian Period, Ma. It is the fifth and penultimate perio ...

whereas other returns occurred as recently as the Cenozoic

The Cenozoic Era ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterized by the dominance of mammals, insects, birds and angiosperms (flowering plants). It is the latest of three g ...

, as in cetaceans, pinniped

Pinnipeds (pronounced ), commonly known as seals, are a widely range (biology), distributed and diverse clade of carnivorous, fin-footed, semiaquatic, mostly marine mammals. They comprise the extant taxon, extant families Odobenidae (whose onl ...

s, and several modern amphibians.

The change from a body plan for breathing and navigating in water to a body plan enabling the animal to move on land is one of the most profound evolutionary changes known.as PDFIt is also one of the best understood, largely thanks to a number of significant

transitional fossil

A transitional fossil is any fossilized remains of a life form that exhibits traits common to both an ancestral group and its derived descendant group. This is especially important where the descendant group is sharply differentiated by gross ...

finds in the late 20th century combined with improved phylogenetic analysis.

Origin

Evolution of fish

The Devonian period is traditionally known as the "Age of Fish", marking the diversification of numerous extinct and modern major fish groups. Among them were the early bony fishes, who diversified and spread in freshwater and brackish environments at the beginning of the period. The early types resembled their cartilaginous ancestors in many features of their anatomy, including a shark-like tailfin, spiral gut, largepectoral fin

Fins are moving appendages protruding from the body of fish that interact with water to generate thrust and help the fish aquatic locomotion, swim. Apart from the tail or caudal fin, fish fins have no direct connection with the vertebral column ...

s stiffened in front by skeletal elements and a largely unossified axial skeleton

The axial skeleton is the core part of the endoskeleton made of the bones of the head and trunk of vertebrates. In the human skeleton, it consists of 80 bones and is composed of the skull (28 bones, including the cranium, mandible and the midd ...

.

They did, however, have certain traits separating them from cartilaginous fishes, traits that would become pivotal in the evolution of terrestrial forms. With the exception of a pair of spiracles, the gills

A gill () is a respiratory organ that many aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they are ...

did not open singly to the exterior as they do in sharks; rather, they were encased in a gill chamber stiffened by membrane bones and covered by a bony operculum, with a single opening to the exterior. The cleithrum bone, forming the posterior margin of the gill chamber, also functioned as anchoring for the pectoral fins. The cartilaginous fishes do not have such an anchoring for the pectoral fins. This allowed for a movable joint at the base of the fins in the early bony fishes, and would later function in a weight bearing structure in tetrapods. As part of the overall armour of rhomboid

Traditionally, in two-dimensional geometry, a rhomboid is a parallelogram in which adjacent sides are of unequal lengths and angles are non-right angled.

The terms "rhomboid" and "parallelogram" are often erroneously conflated with each oth ...

cosmin scales, the skull

The skull, or cranium, is typically a bony enclosure around the brain of a vertebrate. In some fish, and amphibians, the skull is of cartilage. The skull is at the head end of the vertebrate.

In the human, the skull comprises two prominent ...

had a full cover of dermal bone

A dermal bone or investing bone or membrane bone is a bony structure derived from intramembranous ossification forming components of the vertebrate skeleton, including much of the skull, jaws, gill covers, shoulder girdle, fin rays ( lepidotrich ...

, constituting a skull roof

The skull roof or the roofing bones of the skull are a set of bones covering the brain, eyes and nostrils in bony fishes, including land-living vertebrates. The bones are derived from dermal bone and are part of the dermatocranium.

In com ...

over the otherwise shark-like cartilaginous inner cranium. Importantly, they also had a pair of ventral paired lungs, a feature lacking in sharks and rays.

It was assumed that fishes to a large degree evolved around reef

A reef is a ridge or shoal of rock, coral, or similar relatively stable material lying beneath the surface of a natural body of water. Many reefs result from natural, abiotic component, abiotic (non-living) processes such as deposition (geol ...

s, but since their origin about 480 million years ago, they lived in near-shore environments like intertidal areas or permanently shallow lagoons and didn't start to proliferate into other biotopes before 60 million years later. A few adapted to deeper water, while solid and heavily built forms stayed where they were or migrated into freshwater. The increase of primary productivity on land during the late Devonian changed the freshwater ecosystems. When nutrients from plants were released into lakes and rivers, they were absorbed by microorganisms which in turn were eaten by invertebrates, which served as food for vertebrates. Some fish also became detritivore

Detritivores (also known as detrivores, detritophages, detritus feeders or detritus eaters) are heterotrophs that obtain nutrients by consuming detritus (decomposing plant and animal parts as well as feces). There are many kinds of invertebrates, ...

s. Early tetrapods evolved a tolerance to environments which varied in salinity, such as estuaries or deltas.

Lungs before land

The lung/swim bladder

The swim bladder, gas bladder, fish maw, or air bladder is an internal gas-filled organ (anatomy), organ in bony fish that functions to modulate buoyancy, and thus allowing the fish to stay at desired water depth without having to maintain lift ...

originated as an outgrowth of the gut, forming a gas-filled bladder above the digestive system. In its primitive form, the air bladder was open to the alimentary canal

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascular system. ...

, a condition called physostome

Physostomes are fishes that have a pneumatic duct connecting the gas bladder to the alimentary canal. This allows the gas bladder to be filled or emptied via the mouth. This not only allows the fish to fill their bladder by gulping air, but al ...

and still found in many fish. The primary function of swim bladder is not entirely certain. One consideration is buoyancy

Buoyancy (), or upthrust, is the force exerted by a fluid opposing the weight of a partially or fully immersed object (which may be also be a parcel of fluid). In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of t ...

. The heavy scale armour of the early bony fishes would certainly weigh the animals down. In cartilaginous fishes, lacking a swim bladder, the open sea sharks need to swim constantly to avoid sinking into the depths, the pectoral fins providing lift

Lift or LIFT may refer to:

Physical devices

* Elevator, or lift, a device used for raising and lowering people or goods

** Paternoster lift, a type of lift using a continuous chain of cars which do not stop

** Patient lift, or Hoyer lift, mobile ...

. Another factor is oxygen consumption. Ambient oxygen was relatively low in the early Devonian, possibly about half of modern values. Per unit volume, there is much more oxygen in air than in water, and vertebrates (especially nekton

Nekton or necton (from the ) is any aquatic organism that can actively and persistently propel itself through a water column (i.e. swimming) without touching the bottom. Nektons generally have powerful tails and appendages (e.g. fins, pleopods, ...

ic ones) are active animals with a higher energy requirement compared to invertebrates of similar sizes. The Devonian saw increasing oxygen levels which opened up new ecological niches by allowing groups able to exploit the additional oxygen to develop into active, large-bodied animals. Particularly in tropical swampland habitats, atmospheric oxygen is much more stable, and may have prompted a reliance of proto-lungs (performing essentially an evolved type of enteral respiration

Enteral respiration, also referred to as cloacal respiration or intestinal respiration, is a form of respiration in which gas exchange occurs across the epithelia of the enteral system, usually in the caudal cavity (cloaca). This is used in vari ...

) rather than gill

A gill () is a respiration organ, respiratory organ that many aquatic ecosystem, aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow r ...

s for primary oxygen uptake. In the end, both buoyancy and breathing may have been important, and some modern physostome fishes do indeed use their bladders for both.

To function in gas exchange, lungs require a blood supply. In cartilaginous fishes and teleosts, the heart

The heart is a muscular Organ (biology), organ found in humans and other animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels. The heart and blood vessels together make the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrie ...

lies low in the body and pumps blood forward through the ventral aorta, which splits up in a series of paired aortic arches, each corresponding to a gill arch

Branchial arches or gill arches are a series of paired bony/ cartilaginous "loops" behind the throat ( pharyngeal cavity) of fish, which support the fish gills. As chordates, all vertebrate embryos develop pharyngeal arches, though the event ...

. (2nd ed. 1955; 3rd ed. 1962; 4th ed. 1970) The aortic arches then merge above the gills to form a dorsal aorta supplying the body with oxygenated blood. In lungfish

Lungfish are freshwater vertebrates belonging to the class Dipnoi. Lungfish are best known for retaining ancestral characteristics within the Osteichthyes, including the ability to breathe air, and ancestral structures within Sarcopterygii, inc ...

es, bowfin

The ruddy bowfin (''Amia calva'') is a ray-finned fish native to North America. Common names include mudfish, mud pike, dogfish, grindle, grinnel, swamp trout, and choupique. It is regarded as a relict, being one of only two surviving species ...

and bichir

Bichirs and the reedfish comprise Polypteridae , a family (biology), family of archaic Actinopterygii, ray-finned fishes and the only family in the order (biology), order Polypteriformes .Helfman GS, Collette BB, Facey DE, Bowen BW. 2009. The D ...

s, the swim bladder is supplied with blood by paired pulmonary arteries

A pulmonary artery is an artery in the pulmonary circulation that carries deoxygenated blood from the right side of the heart to the lungs. The largest pulmonary artery is the ''main pulmonary artery'' or ''pulmonary trunk'' from the heart, and ...

branching off from the hindmost (6th) aortic arch. The same basic pattern is found in the lungfish '' Protopterus'' and in terrestrial salamanders

Salamanders are a group of amphibians typically characterized by their lizard-like appearance, with slender bodies, blunt snouts, short limbs projecting at right angles to the body, and the presence of a tail in both larvae and adults. All t ...

, and was probably the pattern found in the tetrapods' immediate ancestors as well as the first tetrapods. In most other bony fishes the swim bladder is supplied with blood by the dorsal aorta.

The breath

In order for the lungs to allow gas exchange, the lungs first need to have gas in them. In modern tetrapods, three important breathing mechanisms are conserved from early ancestors, the first being a CO2/H+ detection system. In modern tetrapod breathing, the impulse to take a breath is triggered by a buildup of CO2 in the bloodstream and not a lack of O2. A similar CO2/H+ detection system is found in allOsteichthyes

Osteichthyes ( ; ), also known as osteichthyans or commonly referred to as the bony fish, is a Biodiversity, diverse clade of vertebrate animals that have endoskeletons primarily composed of bone tissue. They can be contrasted with the Chondricht ...

, which implies that the last common ancestor

A most recent common ancestor (MRCA), also known as a last common ancestor (LCA), is the most recent individual from which all organisms of a set are inferred to have descended. The most recent common ancestor of a higher taxon is generally assu ...

of all Osteichthyes had a need of this sort of detection system. The second mechanism for a breath is a surfactant

Surfactants are chemical compounds that decrease the surface tension or interfacial tension between two liquids, a liquid and a gas, or a liquid and a solid. The word ''surfactant'' is a Blend word, blend of "surface-active agent",

coined in ...

system in the lungs to facilitate gas exchange. This is also found in all Osteichthyes, even those that are almost entirely aquatic. The highly conserved nature of this system suggests that even aquatic Osteichthyes have some need for a surfactant system, which may seem strange as there is no gas underwater. The third mechanism for a breath is the actual motion of the breath. This mechanism predates the last common ancestor of Osteichthyes, as it can be observed in '' Lampetra camtshatica,'' the sister clade

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and ...

to Osteichthyes. In Lampreys, this mechanism takes the form of a "cough", where the lamprey shakes its body to allow water flow across its gills. When CO2 levels in the lamprey's blood climb too high, a signal is sent to a central pattern generator that causes the lamprey to "cough" and allow CO2 to leave its body. This linkage between the CO2 detection system and the central pattern generator is extremely similar to the linkage between these two systems in tetrapods, which implies homology.

External and internal nares

Thenostril

A nostril (or naris , : nares ) is either of the two orifices of the nose. They enable the entry and exit of air and other gasses through the nasal cavities. In birds and mammals, they contain branched bones or cartilages called turbinates ...

s in most bony fish differ from those of tetrapods. Normally, bony fish have four nares (nasal openings), one naris behind the other on each side. As the fish swims, water flows into the forward pair, across the olfactory tissue, and out through the posterior openings. This is true not only of ray-finned fish but also of the coelacanth

Coelacanths ( ) are an ancient group of lobe-finned fish (Sarcopterygii) in the class Actinistia. As sarcopterygians, they are more closely related to lungfish and tetrapods (the terrestrial vertebrates including living amphibians, reptiles, bi ...

, a fish included in the Sarcopterygii

Sarcopterygii (; )—sometimes considered synonymous with Crossopterygii ()—is a clade (traditionally a class (biology), class or subclass) of vertebrate animals which includes a group of bony fish commonly referred to as lobe-finned fish. The ...

, the group that also includes the tetrapods. In contrast, the tetrapods have only one pair of nares externally but also sport a pair of internal nares, called choanae

The choanae (: choana), posterior nasal apertures or internal nostrils are two openings found at the back of the nasal passage between the nasal cavity and the pharynx, in humans and other mammals (as well as crocodilians and most skinks). They ...

, allowing them to draw air through the nose. Lungfish are also sarcopterygians with internal nostrils, but these are sufficiently different from tetrapod choanae that they have long been recognized as an independent development.

The evolution of the tetrapods' internal nares was hotly debated in the 20th century. The internal nares could be one set of the external ones (usually presumed to be the posterior pair) that have migrated into the mouth, or the internal pair could be a newly evolved structure. To make way for a migration, however, the two tooth-bearing bones of the upper jaw, the maxilla

In vertebrates, the maxilla (: maxillae ) is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxil ...

and the premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammals h ...

, would have to separate to let the nostril through and then rejoin; until recently, there was no evidence for a transitional stage, with the two bones disconnected. Such evidence is now available: a small lobe-finned fish called ''Kenichthys

''Kenichthys'' is a genus of sarcopterygian fish from the Devonian period, and a member of the clade Tetrapodomorpha. The only known species of the genus is ''Kenichthys campbelli'' (named for the Australian palaeontologist Ken Campbell), the f ...

'', found in China and dated at around 395 million years old, represents evolution "caught in mid-act", with the maxilla and premaxilla separated and an aperture—the incipient choana—on the lip in between the two bones.

* ''Kenichthys'' is more closely related to tetrapods than is the coelacanth, which has only external nares; it thus represents an intermediate stage in the evolution of the tetrapod condition. The reason for the evolutionary movement of the posterior nostril from the nose to lip, however, is not well understood.

Into the shallows

The relatives of ''Kenichthys'' soon established themselves in the waterways and brackish estuaries and became the most numerous of the bony fishes throughout the Devonian and most of the

The relatives of ''Kenichthys'' soon established themselves in the waterways and brackish estuaries and became the most numerous of the bony fishes throughout the Devonian and most of the Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

.

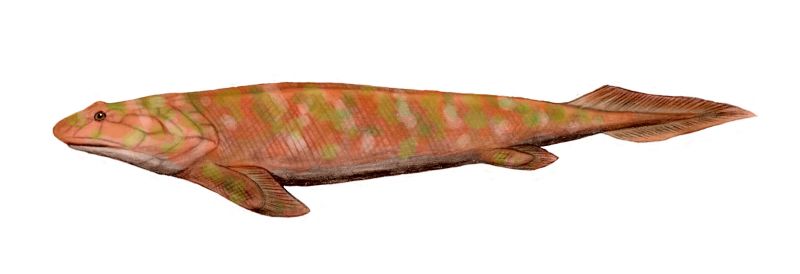

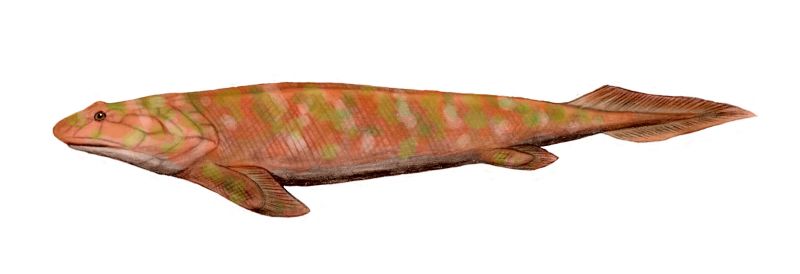

The basic anatomy of the group is well known thanks to the very detailed work on ''Eusthenopteron

''Eusthenopteron'' (from 'stout', and 'wing' or 'fin') is an extinct genus of prehistoric marine lobe-finned fish known from several species that lived during the Late Devonian period, about 385 million years ago. It has attained an iconic ...

'' by Erik Jarvik in the second half of the 20th century.

The bones of the skull roof

The skull roof or the roofing bones of the skull are a set of bones covering the brain, eyes and nostrils in bony fishes, including land-living vertebrates. The bones are derived from dermal bone and are part of the dermatocranium.

In com ...

were broadly similar to those of early tetrapods and the teeth had an infolding of the enamel similar to that of labyrinthodont

"Labyrinthodontia" (Greek, 'maze-toothed') is an informal grouping of extinct predatory amphibians which were major components of ecosystems in the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras (about 390 to 150 million years ago). Traditionally conside ...

s. The paired fins had a build with bones distinctly homologous to the humerus

The humerus (; : humeri) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius (bone), radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extrem ...

, ulna

The ulna or ulnar bone (: ulnae or ulnas) is a long bone in the forearm stretching from the elbow to the wrist. It is on the same side of the forearm as the little finger, running parallel to the Radius (bone), radius, the forearm's other long ...

, and radius

In classical geometry, a radius (: radii or radiuses) of a circle or sphere is any of the line segments from its Centre (geometry), center to its perimeter, and in more modern usage, it is also their length. The radius of a regular polygon is th ...

in the fore-fins and to the femur

The femur (; : femurs or femora ), or thigh bone is the only long bone, bone in the thigh — the region of the lower limb between the hip and the knee. In many quadrupeds, four-legged animals the femur is the upper bone of the hindleg.

The Femo ...

, tibia

The tibia (; : tibiae or tibias), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two Leg bones, bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outsi ...

, and fibula

The fibula (: fibulae or fibulas) or calf bone is a leg bone on the lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long bones. ...

in the pelvic fins.

There were a number of families: Rhizodontida

Rhizodontida is an extinct group of predatory tetrapodomorphs known from many areas of the world from the Givetian through to the Pennsylvanian - the earliest known species is about 377 million years ago (Mya), the latest around 310 Mya. Rhizod ...

, Canowindridae, Elpistostegidae, Megalichthyidae, Osteolepidae and Tristichopteridae

Tristichopterids (Tristichopteridae) were a diverse and successful group of fish-like tetrapodomorphs living throughout the Middle and Late Devonian. They first appeared in the Eifelian stage of the Middle Devonian. Within the group sizes ranged ...

. Most were open-water fishes, and some grew to very large sizes; adult specimens are several meters in length. The Rhizodontid '' Rhizodus'' is estimated to have grown to , making it the largest freshwater fish known.

While most of these were open-water fishes, one group, the Elpistostegalia

Elpistostegalia is a clade containing ''Panderichthys'' and all more derived Tetrapodomorpha, tetrapodomorph taxa. The earliest elpistostegalians, combining fishlike and tetrapod-like characters, such as ''Tiktaalik'', are sometimes called fisha ...

ns, adapted to life in the shallows. They evolved flat bodies for movement in very shallow water, and the pectoral and pelvic fins took over as the main propulsion organs. Most median fins disappeared, leaving only a protocercal tailfin. Since the shallows were subject to occasional oxygen deficiency, the ability to breathe atmospheric air with the swim bladder became increasingly important. The spiracle became large and prominent, enabling these fishes to draw air.

Skull morphology

The tetrapods have their root in the earlyDevonian

The Devonian ( ) is a period (geology), geologic period and system (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era during the Phanerozoic eon (geology), eon, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the preceding Silurian per ...

tetrapodomorph fish. Primitive tetrapods developed from an osteolepid tetrapodomorph lobe-finned fish (sarcopterygian-crossopterygian), with a two-lobed brain

The brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head (cephalization), usually near organs for ...

in a flattened skull

The skull, or cranium, is typically a bony enclosure around the brain of a vertebrate. In some fish, and amphibians, the skull is of cartilage. The skull is at the head end of the vertebrate.

In the human, the skull comprises two prominent ...

. The coelacanth group represents marine sarcopterygians that never acquired these shallow-water adaptations. The sarcopterygians apparently took two different lines of descent and are accordingly separated into two major groups: the Actinistia

Coelacanths ( ) are an ancient group of lobe-finned fish (Sarcopterygii) in the class Actinistia. As sarcopterygians, they are more closely related to lungfish and tetrapods (the terrestrial vertebrates including living amphibians, reptiles, bi ...

(including the coelacanths) and the Rhipidistia

Rhipidistia, also known as Dipnotetrapodomorpha, is a clade of lobe-finned fishes which includes the tetrapods and lungfishes. Rhipidistia formerly referred to a subgroup of Sarcopterygii consisting of the Porolepiformes and Osteolepiformes, a de ...

(which include extinct lines of lobe-finned fishes that evolved into the lungfish and the tetrapodomorphs).

From fins to feet

The oldest known tetrapodomorph is ''

The oldest known tetrapodomorph is ''Kenichthys

''Kenichthys'' is a genus of sarcopterygian fish from the Devonian period, and a member of the clade Tetrapodomorpha. The only known species of the genus is ''Kenichthys campbelli'' (named for the Australian palaeontologist Ken Campbell), the f ...

'' from China, dated at around 395 million years old. Two of the earliest tetrapodomorphs, dating from 380 Ma, were '' Gogonasus'' and ''Panderichthys

''Panderichthys'' is a genus of extinction, extinct Sarcopterygii, sarcopterygian (lobe-finned fish) from the late Devonian period, about 380 Myr, Mya. ''Panderichthys'', which was recovered from Frasnian (early Late Devonian) deposits in Latvia, ...

''. They had choanae

The choanae (: choana), posterior nasal apertures or internal nostrils are two openings found at the back of the nasal passage between the nasal cavity and the pharynx, in humans and other mammals (as well as crocodilians and most skinks). They ...

and used their fins to move through tidal channels and shallow waters choked with dead branches and rotting plants. Their fins could have been used to attach themselves to plants or similar while they were lying in ambush for prey. The universal tetrapod characteristics of front limbs that bend forward from the elbow

The elbow is the region between the upper arm and the forearm that surrounds the elbow joint. The elbow includes prominent landmarks such as the olecranon, the cubital fossa (also called the chelidon, or the elbow pit), and the lateral and t ...

and hind limbs that bend backward from the knee

In humans and other primates, the knee joins the thigh with the leg and consists of two joints: one between the femur and tibia (tibiofemoral joint), and one between the femur and patella (patellofemoral joint). It is the largest joint in the hu ...

can plausibly be traced to early tetrapods living in shallow water. Pelvic bone fossils from ''Tiktaalik

''Tiktaalik'' (; ) is a monospecific genus of extinct sarcopterygian (lobe-finned fish) from the Late Devonian Period, about 375 Mya (million years ago), having many features akin to those of tetrapods (four-legged animals). ''Tiktaalik'' is est ...

'' shows, if representative for early tetrapods in general, that hind appendages and pelvic-propelled locomotion originated in water before terrestrial adaptations.

Another indication that feet and other tetrapod traits evolved while the animals were still aquatic is how they were feeding. They did not have the modifications of the skull and jaw that allowed them to swallow prey on land. Prey could be caught in the shallows, at the water's edge or on land, but had to be eaten in water where hydrodynamic forces from the expansion of their buccal cavity would force the food into their esophagus.

It has been suggested that the evolution of the tetrapod limb from fins in lobe-finned fishes is related to expression of the HOXD13 gene or the loss of the proteins actinodin 1 and actinodin 2, which are involved in fish fin development. Robot simulations suggest that the necessary nervous circuitry for walking evolved from the nerves governing swimming, utilizing the sideways oscillation

Oscillation is the repetitive or periodic variation, typically in time, of some measure about a central value (often a point of equilibrium) or between two or more different states. Familiar examples of oscillation include a swinging pendulum ...

of the body with the limbs primarily functioning as anchoring points and providing limited thrust. This type of movement, as well as changes to the pectoral girdle are similar to those seen in the fossil record, can be induced in bichir

Bichirs and the reedfish comprise Polypteridae , a family (biology), family of archaic Actinopterygii, ray-finned fishes and the only family in the order (biology), order Polypteriformes .Helfman GS, Collette BB, Facey DE, Bowen BW. 2009. The D ...

s by raising them out of water.

A 2012 study using 3D reconstructions of ''Ichthyostega

''Ichthyostega'', from Ancient Greek ἰχθύς (''ikthús''), meaning "fish", and στέγη (''stégē''), meaning "roof", is an Extinction, extinct genus of limbed tetrapodomorpha, tetrapodomorphs from the Devonian, Late Devonian of what is ...

'' concluded that it was incapable of typical quadrupedal gaits. The limbs could not move alternately as they lacked the necessary rotary motion range. In addition, the hind limbs lacked the necessary pelvic musculature for hindlimb-driven land movement. Their most likely method of terrestrial locomotion is that of synchronous "crutching motions", similar to modern mudskipper

Mudskippers are any of the 23 extant species of amphibious fish from the subfamily Oxudercinae of the goby family (biology), family Oxudercidae. They are known for their unusual body shapes, preferences for semiaquatic habitats, limited terrestria ...

s. ''(Viewing several videos of mudskipper "walking" shows that they move by pulling themselves forward with both pectoral fins at the same time (left & right pectoral fins move simultaneously, not alternatively). The fins are brought forward and planted; the shoulders then rotate rearward, advancing the body & dragging the tail as a third point of contact. There are no rear "limbs"/fins, and there is no significant flexure of the spine involved.)''

Denizens of the swamp

The first tetrapods probablyevolved

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

in coastal and brackish

Brackish water, sometimes termed brack water, is water occurring in a natural environment that has more salinity than freshwater, but not as much as seawater. It may result from mixing seawater (salt water) and fresh water together, as in estuari ...

marine environments, and in shallow and swamp

A swamp is a forested wetland.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p. Swamps are considered to be transition zones because both land and water play a role in ...

y freshwater

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. The term excludes seawater and brackish water, but it does include non-salty mi ...

habitats

In ecology, habitat refers to the array of resources, biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species' habitat can be seen as the physical manifestation of its ...

. Formerly, researchers thought the timing was towards the end of the Devonian. In 2010, this belief was challenged by the discovery of the oldest known tetrapod tracks named the Zachelmie trackways The Zachelmie trackways are a series of Middle Devonian-age Trace fossil, trace fossils in Poland, purportedly the oldest evidence of terrestrial Vertebrate, vertebrates (Tetrapod, tetrapods) in the fossil record. These trackways were discovered in ...

, preserved in marine sediments of the southern coast of Laurasia

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around ( Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pa ...

, now Świętokrzyskie (Holy Cross) Mountains of Poland. They were made during the Eifelian age, early Middle Devonian. The tracks, some of which show digits, date to about 395 million years ago—18 million years earlier than the oldest known tetrapod body fossils. Additionally, the tracks show that the animal was capable of thrusting its arms and legs forward, a type of motion that would have been impossible in tetrapodomorph fish like ''Tiktaalik

''Tiktaalik'' (; ) is a monospecific genus of extinct sarcopterygian (lobe-finned fish) from the Late Devonian Period, about 375 Mya (million years ago), having many features akin to those of tetrapods (four-legged animals). ''Tiktaalik'' is est ...

''. The animal that produced the tracks is estimated to have been up to long with footpads up to wide, although most tracks are only wide.

The new finds suggest that the first tetrapods may have lived as opportunists on the tidal flats, feeding on marine animals that were washed up or stranded by the tide. Currently, however, fish are stranded in significant numbers only at certain times of year, as in alewife spawning season; such strandings could not provide a significant supply of food for predators. There is no reason to suppose that Devonian fish were less prudent than those of today. According to Melina Hale of University of Chicago, not all ancient trackways are necessarily made by early tetrapods, but could also be created by relatives of the tetrapods who used their fleshy appendages in a similar substrate-based locomotion.

Palaeozoic tetrapods

Devonian tetrapods

Research by Jennifer A. Clack and her colleagues showed that the very earliest tetrapods, animals similar to ''Acanthostega

''Acanthostega'', from Ancient Greek ἄκανθα (''ákantha''), meaning "spine", and στέγη (''stégē''), meaning "roof", is an extinct genus of stem tetrapoda, stem-tetrapod, among the first vertebrates, vertebrate animals to have recogn ...

'', were wholly aquatic and quite unsuited to life on land. This is in contrast to the earlier view that fish had first invaded the land — either in search of prey (like modern mudskipper

Mudskippers are any of the 23 extant species of amphibious fish from the subfamily Oxudercinae of the goby family (biology), family Oxudercidae. They are known for their unusual body shapes, preferences for semiaquatic habitats, limited terrestria ...

s) or to find water when the pond they lived in dried out — and later evolved legs, lungs, etc.

By the late Devonian, land plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with c ...

s had stabilized freshwater habitats, allowing the first wetland

A wetland is a distinct semi-aquatic ecosystem whose groundcovers are flooded or saturated in water, either permanently, for years or decades, or only seasonally. Flooding results in oxygen-poor ( anoxic) processes taking place, especially ...

ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) is a system formed by Organism, organisms in interaction with their Biophysical environment, environment. The Biotic material, biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and en ...

s to develop, with increasingly complex food web

A food web is the natural interconnection of food chains and a graphical representation of what-eats-what in an ecological community. Position in the food web, or trophic level, is used in ecology to broadly classify organisms as autotrophs or he ...

s that afforded new opportunities. Freshwater habitats were not the only places to find water filled with organic matter and dense vegetation near the water's edge. Swampy habitats like shallow wetlands, coastal lagoons and large brackish river deltas also existed at this time, and there is much to suggest that this is the kind of environment in which the tetrapods evolved. Early fossil tetrapods have been found in marine sediments, and because fossils of primitive tetrapods in general are found scattered all around the world, they must have spread by following the coastal lines — they could not have lived in freshwater only.

One analysis from the University of Oregon suggests no evidence for the "shrinking waterhole" theory — transitional fossils are not associated with evidence of shrinking puddles or ponds — and indicates that such animals would probably not have survived short treks between depleted waterholes. The new theory suggests instead that proto-lungs and proto-limbs were useful adaptations to negotiate the environment in humid, wooded floodplains.

The Devonian tetrapods went through two major bottlenecks during what is known as the Late Devonian extinction

The Late Devonian mass extinction, also known as the Kellwasser event, was a mass extinction event which occurred around 372 million years ago, at the boundary between the Frasnian and Famennian ages of the Late Devonian period.Racki, 2005McGh ...

; one at the end of the Frasnian stage, and one twice as large at the end of the following Famennian

The Famennian is the later of two faunal stages in the Late Devonian epoch. The most recent estimate for its duration is that it lasted from around 371.1 to 359.3 million years ago. An earlier 2012 estimate, still used by the International Commis ...

stage. These events of extinctions led to the disappearance of primitive tetrapods with fish-like features like Ichthyostega and their primary more aquatic relatives. When tetrapods reappear in the fossil record after the Devonian extinctions, the adult forms are all fully adapted to a terrestrial existence, with later species secondarily adapted to an aquatic lifestyle.

Lungs

It is now clear that the common ancestor of the bony fishes (Osteichthyes) had a primitive air-breathinglung

The lungs are the primary Organ (biology), organs of the respiratory system in many animals, including humans. In mammals and most other tetrapods, two lungs are located near the Vertebral column, backbone on either side of the heart. Their ...

—later evolved into a swim bladder

The swim bladder, gas bladder, fish maw, or air bladder is an internal gas-filled organ (anatomy), organ in bony fish that functions to modulate buoyancy, and thus allowing the fish to stay at desired water depth without having to maintain lift ...

in most actinopterygians (ray-finned fishes). This suggests that crossopterygians evolved in warm shallow waters, using their simple lung when the oxygen level in the water became too low.

Fleshy lobe-fins supported on bones rather than ray-stiffened fins seem to have been an ancestral trait of all bony fishes (Osteichthyes

Osteichthyes ( ; ), also known as osteichthyans or commonly referred to as the bony fish, is a Biodiversity, diverse clade of vertebrate animals that have endoskeletons primarily composed of bone tissue. They can be contrasted with the Chondricht ...

). The lobe-finned ancestors of the tetrapods evolved them further, while the ancestors of the ray-finned fishes (Actinopterygii

Actinopterygii (; ), members of which are known as ray-finned fish or actinopterygians, is a class (biology), class of Osteichthyes, bony fish that comprise over 50% of living vertebrate species. They are so called because of their lightly built ...

) evolved their fins in a different direction. The most primitive group of actinopterygians, the bichir

Bichirs and the reedfish comprise Polypteridae , a family (biology), family of archaic Actinopterygii, ray-finned fishes and the only family in the order (biology), order Polypteriformes .Helfman GS, Collette BB, Facey DE, Bowen BW. 2009. The D ...

s, still have fleshy frontal fins.

Fossils of early tetrapods

Ninegenera

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family as used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In binomial nomenclature, the genus name forms the first part of the binomial s ...

of Devonian tetrapods have been described, several known mainly or entirely from lower jaw

The jaws are a pair of opposable articulated structures at the entrance of the mouth, typically used for grasping and manipulating food. The term ''jaws'' is also broadly applied to the whole of the structures constituting the vault of the mouth ...

material. All but one were from the Laurasia

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around ( Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pa ...

n supercontinent

In geology, a supercontinent is the assembly of most or all of Earth's continent, continental blocks or cratons to form a single large landmass. However, some geologists use a different definition, "a grouping of formerly dispersed continents", ...

, which comprised Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

, North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

and Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

. The only exception is a single Gondwana

Gondwana ( ; ) was a large landmass, sometimes referred to as a supercontinent. The remnants of Gondwana make up around two-thirds of today's continental area, including South America, Africa, Antarctica, Australia (continent), Australia, Zea ...

n genus, ''Metaxygnathus

''Metaxygnathus'' is an extinct genus of ichthyostegalian found in Late Devonian deposits of New South Wales, Australia.

It is known only from a lower jawbone. Previously thought to be a lobe-finned fish

Sarcopterygii (; )—sometimes conside ...

'', which has been found in Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

.

The first Devonian tetrapod identified from Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

was recognized from a fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

jawbone reported in 2002. The Chinese tetrapod '' Sinostega pani'' was discovered among fossilized tropical plants and lobe-finned fish in the red sandstone

Sandstone is a Clastic rock#Sedimentary clastic rocks, clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of grain size, sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate mineral, silicate grains, Cementation (geology), cemented together by another mineral. Sand ...

sediments of the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region of northwest China. This finding substantially extended the geographical range of these animals and has raised new questions about the worldwide distribution and great taxonomic diversity they achieved within a relatively short time.

These earliest tetrapods were not terrestrial. The earliest confirmed terrestrial forms are known from the early

These earliest tetrapods were not terrestrial. The earliest confirmed terrestrial forms are known from the early Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

deposits, some 20 million years later. Still, they may have spent very brief periods out of water and would have used their legs to paw their way through the mud

Mud (, or Middle Dutch) is loam, silt or clay mixed with water. Mud is usually formed after rainfall or near water sources. Ancient mud deposits hardened over geological time to form sedimentary rock such as shale or mudstone (generally cal ...

.

Why they went to land in the first place is still debated. One reason could be that the small juveniles who had completed their metamorphosis

Metamorphosis is a biological process by which an animal physically develops including birth transformation or hatching, involving a conspicuous and relatively abrupt change in the animal's body structure through cell growth and different ...

had what it took to make use of what land had to offer. Already adapted to breathe air and move around in shallow waters near land as a protection (just as modern fish and amphibians often spend the first part of their life in the comparative safety of shallow waters like mangrove

A mangrove is a shrub or tree that grows mainly in coastal saline water, saline or brackish water. Mangroves grow in an equatorial climate, typically along coastlines and tidal rivers. They have particular adaptations to take in extra oxygen a ...

forests), two very different niches partially overlapped each other, with the young juveniles in the diffuse line between. One of them was overcrowded and dangerous while the other was much safer and much less crowded, offering less competition over resources. The terrestrial niche was also a much more challenging place for primarily aquatic animals, but because of the way evolution and selection pressure work, those juveniles who could take advantage of this would be rewarded. Once they gained a small foothold on land, thanks to their pre-adaptations, favourable variations in their descendants would gradually result in continuing evolution and diversification.

At this time the abundance of invertebrates crawling around on land and near water, in moist soil and wet litter, offered a food supply. Some were even big enough to eat small tetrapods, but the land was free from dangers common in the water.

From water to land

Initially making only tentative forays onto land, tetrapods adapted to terrestrial environments over time and spent longer periods away from the water. It is also possible that the adults started to spend some time on land (as the skeletal modifications in early tetrapods such as ''Ichthyostega

''Ichthyostega'', from Ancient Greek ἰχθύς (''ikthús''), meaning "fish", and στέγη (''stégē''), meaning "roof", is an Extinction, extinct genus of limbed tetrapodomorpha, tetrapodomorphs from the Devonian, Late Devonian of what is ...

'' suggests) to bask in the sun close to the water's edge, while otherwise being mostly aquatic.

However, recent microanatomical and histological analysis of tetrapod fossil specimens found that early tetrapods like ''Acanthostega'' were fully aquatic, suggesting that adaptation to land happened later.

Research by Per Ahlberg and colleagues suggest that tides could have been a driving force for the evolution of tetrapods. The hypothesis proposes that as "the tide retreated, fishes became stranded in shallow water tidal-pool environments, where they would be subjected to raised temperatures and hypoxic conditions" and then fishes that developed "efficient air-breathing organs, as well as for appendages adapted for land navigation" would be selected.

Carboniferous tetrapods

Until the 1990s, there was a 30 million year gap in the fossil record between the late Devonian tetrapods and the reappearance of tetrapod fossils in recognizable mid-Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

amphibian

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

lineages. It was referred to as "Romer's Gap

Romer's gap is an apparent gap in the Paleozoic tetrapod fossil record noted in the studies of paleontology and evolutionary biology, which represent periods in the Early Carboniferous from which excavators have not yet found relevant transition ...

", which now covers the period from about 360 to 345 million years ago (the Devonian-Carboniferous transition and the early Mississippian), after the palaeontologist

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geolo ...

who recognized it.

During the "gap", tetrapod backbones developed, as did limbs with digits and other adaptations for terrestrial life. Ear

In vertebrates, an ear is the organ that enables hearing and (in mammals) body balance using the vestibular system. In humans, the ear is described as having three parts: the outer ear, the middle ear and the inner ear. The outer ear co ...

s, skull

The skull, or cranium, is typically a bony enclosure around the brain of a vertebrate. In some fish, and amphibians, the skull is of cartilage. The skull is at the head end of the vertebrate.

In the human, the skull comprises two prominent ...

s and vertebra

Each vertebra (: vertebrae) is an irregular bone with a complex structure composed of bone and some hyaline cartilage, that make up the vertebral column or spine, of vertebrates. The proportions of the vertebrae differ according to their spina ...

l columns all underwent changes too. The number of digits on hand

A hand is a prehensile, multi-fingered appendage located at the end of the forearm or forelimb of primates such as humans, chimpanzees, monkeys, and lemurs. A few other vertebrates such as the Koala#Characteristics, koala (which has two thumb#O ...

s and feet became standardized at five, as lineages with more digits died out. Thus, those very few tetrapod fossils found in this "gap" are all the more prized by palaeontologists because they document these significant changes and clarify their history.

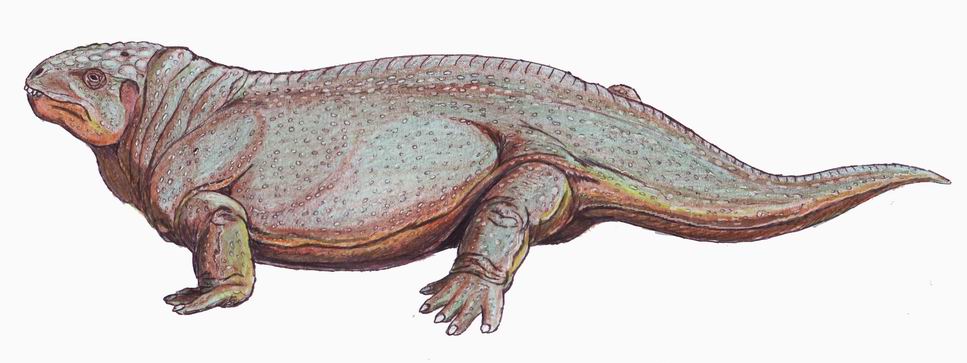

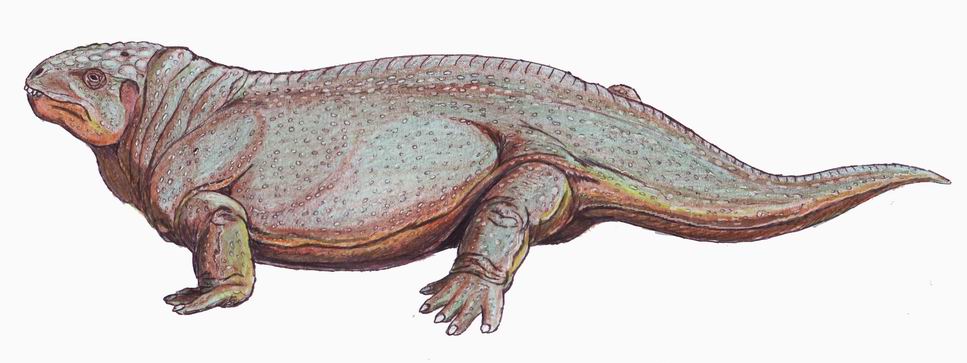

The transition from an aquatic, lobe-finned fish to an air-breathing amphibian was a significant and fundamental one in the evolutionary history of the vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

s. For an organism to live in a gravity

In physics, gravity (), also known as gravitation or a gravitational interaction, is a fundamental interaction, a mutual attraction between all massive particles. On Earth, gravity takes a slightly different meaning: the observed force b ...

-neutral aqueous environment, then colonize one that requires an organism to support its entire weight and possess a mechanism to mitigate dehydration, required significant adaptations or exaptations within the overall body plan

A body plan, (), or ground plan is a set of morphology (biology), morphological phenotypic trait, features common to many members of a phylum of animals. The vertebrates share one body plan, while invertebrates have many.

This term, usually app ...

, both in form and in function. '' Eryops'', an example of an animal that made such adaptations, refined many of the traits found in its fish ancestors. Sturdy limbs supported and transported its body while out of water. A thicker, stronger backbone prevented its body from sagging under its own weight. Also, through the reshaping of vestigial fish jaw bones, a rudimentary middle ear began developing to connect to the piscine inner ear, allowing ''Eryops'' to amplify, and so better sense, airborne sound

In physics, sound is a vibration that propagates as an acoustic wave through a transmission medium such as a gas, liquid or solid.

In human physiology and psychology, sound is the ''reception'' of such waves and their ''perception'' by the br ...

.

By the Visean (mid early-Carboniferous) stage, the early tetrapods had radiated into at least three or four main branches. Some of these different branches represent the ancestors to all living tetrapods. This means that the common ancestor of all living tetrapods likely lived in the early Carboniferous. Under a narrow cladistic

Cladistics ( ; from Ancient Greek 'branch') is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is ...

definition of Tetrapoda (also known as crown-Tetrapoda), which only includes descendants of this common ancestor, tetrapods first appeared in the Carboniferous. Recognizable early tetrapods (in the broad sense) are representative of the temnospondyls

Temnospondyli (from Greek τέμνειν, ''temnein'' 'to cut' and σπόνδυλος, ''spondylos'' 'vertebra') or temnospondyls is a diverse ancient order of small to giant tetrapods—often considered primitive amphibians—that flourished wo ...

(e.g. '' Eryops'') lepospondyls

Lepospondyli is a diverse clade of early tetrapods. With the exception of one late-surviving lepospondyl from the Late Permian of Morocco ('' Diplocaulus minimus''), lepospondyls lived from the Visean stage of the Early Carboniferous to the Earl ...

(e.g. '' Diplocaulus''), anthracosaurs, which were the relatives and ancestors of the Amniota

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolved from amphibious stem tetrapod ancestors during the C ...

, and possibly the baphetids, which are thought to be related to temnospondyls and whose status as a main branch is yet unresolved. Depending on which authorities one follows, modern amphibians (frogs, salamander

Salamanders are a group of amphibians typically characterized by their lizard-like appearance, with slender bodies, blunt snouts, short limbs projecting at right angles to the body, and the presence of a tail in both larvae and adults. All t ...

s and caecilian

Caecilians (; ) are a group of limbless, vermiform (worm-shaped) or serpentine (snake-shaped) amphibians with small or sometimes nonexistent eyes. They mostly live hidden in soil or in streambeds, and this cryptic lifestyle renders caecilians ...

s) are most probably derived from either temnospondyls or lepospondyls (or possibly both, although this is now a minority position).

The first amniotes

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolved from amphibious stem tetrapod ancestors during the ...

(clade of vertebrates that today includes reptiles

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology), orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocepha ...

, mammals

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three middle e ...

, and birds

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

) are known from the early part of the Late Carboniferous

Late or LATE may refer to:

Everyday usage

* Tardy, or late, not being on time

* Late (or the late) may refer to a person who is dead

Music

* Late (The 77s album), ''Late'' (The 77s album), 2000

* Late (Alvin Batiste album), 1993

* Late!, a pseudo ...

. By the Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

, this group had already radiated into the earliest mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s, turtle

Turtles are reptiles of the order (biology), order Testudines, characterized by a special turtle shell, shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Crypt ...

s, and crocodile

Crocodiles (family (biology), family Crocodylidae) or true crocodiles are large, semiaquatic reptiles that live throughout the tropics in Africa, Asia, the Americas and Australia. The term "crocodile" is sometimes used more loosely to include ...

s (lizard

Lizard is the common name used for all Squamata, squamate reptiles other than snakes (and to a lesser extent amphisbaenians), encompassing over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most Island#Oceanic isla ...

s and bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s appeared in the Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 143.1 Mya. ...

, and snake

Snakes are elongated limbless reptiles of the suborder Serpentes (). Cladistically squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales much like other members of the group. Many species of snakes have s ...

s in the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

). This contrasts sharply with the (possibly fourth) Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

group, the baphetids, which have left no extant surviving lineages.

Carboniferous rainforest collapse

Amphibians and reptiles were strongly affected by theCarboniferous rainforest collapse

The Carboniferous rainforest collapse (CRC) was a minor extinction event that occurred around 305 million years ago in the Carboniferous period. The event occurred at the end of the Moscovian and continued into the early Kasimovian stages of th ...

(CRC), an extinction event that occurred ~307 million years ago. The Carboniferous period has long been associated with thick, steamy swamps and humid rainforests. Since plants form the base of almost all of Earth's ecosystems, any changes in plant distribution have always affected animal life to some degree. The sudden collapse of the vital rainforest ecosystem profoundly affected the diversity and abundance of the major tetrapod groups that relied on it. The CRC, which was a part of one of the top two most devastating plant extinctions in Earth's history, was a self-reinforcing and very rapid change of environment wherein the worldwide climate became much drier and cooler overall (although much new work is being done to better understand the fine-grained historical climate change

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in Global surface temperature, global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in ...

s in the Carboniferous-Permian transition and how they arose).

The ensuing worldwide plant reduction resulting from the difficulties plants encountered in adjusting to the new climate caused a progressive fragmentation and collapse of rainforest ecosystems. This reinforced and so further accelerated the collapse by sharply reducing the amount of animal life which could be supported by the shrinking ecosystems at that time. The outcome of this animal reduction was a crash in global carbon dioxide levels, which impacted the plants even more. The aridity and temperature drop which resulted from this runaway plant reduction and decrease in a primary greenhouse gas caused the Earth to rapidly enter a series of intense Ice Ages.

This impacted amphibians in particular in a number of ways. The enormous drop in sea level due to greater quantities of the world's water being locked into glaciers profoundly affected the distribution and size of the semiaquatic ecosystems which amphibians favored, and the significant cooling of the climate further narrowed the amount of new territory favorable to amphibians. Given that among the hallmarks of amphibians are an obligatory return to a body of water to lay eggs, a delicate skin prone to desiccation

Desiccation is the state of extreme dryness, or the process of extreme drying. A desiccant is a hygroscopic (attracts and holds water) substance that induces or sustains such a state in its local vicinity in a moderately sealed container. The ...

(thereby often requiring the amphibian to be relatively close to water throughout its life), and a reputation of being a bellwether species for disrupted ecosystems due to the resulting low resilience to ecological change, amphibians were particularly devastated, with the Labyrinthodont

"Labyrinthodontia" (Greek, 'maze-toothed') is an informal grouping of extinct predatory amphibians which were major components of ecosystems in the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras (about 390 to 150 million years ago). Traditionally conside ...

s among the groups faring worst. In contrast, reptiles - whose amniotic eggs have a membrane that enables gas exchange out of water, and which thereby can be laid on land - were better adapted to the new conditions. Reptiles invaded new niches at a faster rate and began diversifying their diets, becoming herbivorous and carnivorous, rather than feeding exclusively on insects and fish. Meanwhile, the severely impacted amphibians simply could not out-compete reptiles in mastering the new ecological niches, and so were obligated to pass the tetrapod evolutionary torch to the increasingly successful and swiftly radiating reptiles.

Permian tetrapods

In thePermian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years, from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.902 Mya. It is the s ...

period: early "amphibia" (labyrinthodonts) clades included temnospondyl

Temnospondyli (from Greek language, Greek τέμνειν, ''temnein'' 'to cut' and σπόνδυλος, ''spondylos'' 'vertebra') or temnospondyls is a diverse ancient order (biology), order of small to giant tetrapods—often considered Labyrinth ...

and anthracosaur; while amniote

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial animal, terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolution, evolved from amphibious Stem tet ...

clades included the Sauropsida

Sauropsida (Greek language, Greek for "lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the Class (biology), class Reptile, Reptilia, though typically used in a broader sense to also include extinct stem-group relatives of modern repti ...

and the Synapsida

Synapsida is a diverse group of tetrapod vertebrates that includes all mammals and their extinct relatives. It is one of the two major clades of the group Amniota, the other being the more diverse group Sauropsida (which includes all extant rep ...

. Sauropsida would eventually evolve into today's reptiles

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology), orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocepha ...

and birds

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

; whereas Synapsida would evolve into today's mammals

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three middle e ...

. During the Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years, from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.902 Mya. It is the s ...

, however, the distinction was less clear—amniote fauna being typically described as either ''reptile'' or as ''mammal-like reptile''. The latter (synapsida) were the most important and successful Permian animals.

The end of the Permian saw a major turnover in fauna during the Permian–Triassic extinction event

The Permian–Triassic extinction event (also known as the P–T extinction event, the Late Permian extinction event, the Latest Permian extinction event, the End-Permian extinction event, and colloquially as the Great Dying,) was an extinction ...

: probably the most severe mass extinction event of the phanerozoic

The Phanerozoic is the current and the latest of the four eon (geology), geologic eons in the Earth's geologic time scale, covering the time period from 538.8 million years ago to the present. It is the eon during which abundant animal and ...

. There was a protracted loss of species, due to multiple extinction pulses. Many of the once large and diverse groups died out or were greatly reduced.

Mesozoic tetrapods

Life on Earth seemed to recover quickly after the Permian extinctions, though this was mostly in the form of disaster taxa such as the hardy ''Lystrosaurus

''Lystrosaurus'' (; 'shovel lizard'; proper Ancient Greek is ''lístron'' ‘tool for leveling or smoothing, shovel, spade, hoe’) is an extinct genus of herbivorous dicynodont therapsids from the late Permian and Early Triassic epochs (arou ...

''. Specialized animals that formed complex ecosystems with high biodiversity, complex food webs, and a variety of niches, took much longer to recover. Current research indicates that this long recovery was due to successive waves of extinction, which inhibited recovery, and to prolonged environmental stress to organisms that continued into the Early Triassic. Recent research indicates that recovery did not begin until the start of the mid-Triassic, 4M to 6M years after the extinction; and some writers estimate that the recovery was not complete until 30M years after the P-Tr extinction, i.e. in the late Triassic.

A small group of reptiles, the diapsid

Diapsids ("two arches") are a clade of sauropsids, distinguished from more primitive eureptiles by the presence of two holes, known as temporal fenestrae, in each side of their skulls. The earliest traditionally identified diapsids, the araeosc ...

s, began to diversify during the Triassic, notably the dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

s. By the late Mesozoic, the large labyrinthodont

"Labyrinthodontia" (Greek, 'maze-toothed') is an informal grouping of extinct predatory amphibians which were major components of ecosystems in the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras (about 390 to 150 million years ago). Traditionally conside ...

groups that first appeared during the Paleozoic such as temnospondyls

Temnospondyli (from Greek τέμνειν, ''temnein'' 'to cut' and σπόνδυλος, ''spondylos'' 'vertebra') or temnospondyls is a diverse ancient order of small to giant tetrapods—often considered primitive amphibians—that flourished wo ...

and reptile-like amphibians had gone extinct. All current major groups of sauropsids evolved during the Mesozoic, with birds

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

first appearing in the Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 143.1 Mya. ...

as a derived clade of theropod

Theropoda (; from ancient Greek , (''therion'') "wild beast"; , (''pous, podos'') "foot"">wiktionary:ποδός"> (''pous, podos'') "foot" is one of the three major groups (clades) of dinosaurs, alongside Ornithischia and Sauropodom ...

dinosaurs. Many groups of synapsid

Synapsida is a diverse group of tetrapod vertebrates that includes all mammals and their extinct relatives. It is one of the two major clades of the group Amniota, the other being the more diverse group Sauropsida (which includes all extant rept ...

s such as anomodont

Anomodontia is an extinct group of non-mammalian therapsids from the Permian and Triassic periods. By far the most speciose group are the dicynodonts, a clade of beaked, tusked herbivores. Anomodonts were very diverse during the Middle Pe ...

s and therocephalia

Therocephalia is an extinct clade of therapsids (mammals and their close extinct relatives) from the Permian and Triassic periods. The therocephalians ("beast-heads") are named after their large skulls, which, along with the structure of their te ...

ns that once comprised the dominant terrestrial fauna of the Permian also became extinct during the Mesozoic; during the Triassic, however, one group (Cynodontia