Euxine on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Black Sea is a marginal

The Black Sea is a marginal

Robert Beekes

/ref> In the Greater Bundahishn, a

Short-term climatic variation in the Black Sea region is significantly influenced by the operation of the North Atlantic oscillation, the climatic mechanisms resulting from the interaction between the north Atlantic and mid-latitude air masses. While the exact mechanisms causing the North Atlantic Oscillation remain unclear, it is thought the climate conditions established in western Europe mediate the heat and precipitation fluxes reaching Central Europe and Eurasia, regulating the formation of winter

Short-term climatic variation in the Black Sea region is significantly influenced by the operation of the North Atlantic oscillation, the climatic mechanisms resulting from the interaction between the north Atlantic and mid-latitude air masses. While the exact mechanisms causing the North Atlantic Oscillation remain unclear, it is thought the climate conditions established in western Europe mediate the heat and precipitation fluxes reaching Central Europe and Eurasia, regulating the formation of winter

The Black Sea is the world's largest body of water with a meromictic basin. The deep waters do not mix with the upper layers of water that receive oxygen from the atmosphere. As a result, over 90% of the deeper Black Sea volume is

The Black Sea is the world's largest body of water with a meromictic basin. The deep waters do not mix with the upper layers of water that receive oxygen from the atmosphere. As a result, over 90% of the deeper Black Sea volume is  Below the pycnocline is the Deep Water mass, where salinity increases to 22.3 PSU and temperatures rise to around . The hydrochemical environment shifts from oxygenated to anoxic, as bacterial decomposition of sunken biomass utilizes all of the free oxygen. Weak geothermal heating and long residence time create a very thick convective bottom layer.

The Black Sea undersea river is a current of particularly saline water flowing through the Bosporus Strait and along the

Below the pycnocline is the Deep Water mass, where salinity increases to 22.3 PSU and temperatures rise to around . The hydrochemical environment shifts from oxygenated to anoxic, as bacterial decomposition of sunken biomass utilizes all of the free oxygen. Weak geothermal heating and long residence time create a very thick convective bottom layer.

The Black Sea undersea river is a current of particularly saline water flowing through the Bosporus Strait and along the

The Black Sea supports an active and dynamic marine ecosystem, dominated by species suited to the brackish, nutrient-rich, conditions. As with all marine food webs, the Black Sea features a range of trophic groups, with

The Black Sea supports an active and dynamic marine ecosystem, dominated by species suited to the brackish, nutrient-rich, conditions. As with all marine food webs, the Black Sea features a range of trophic groups, with

The main phytoplankton groups present in the Black Sea are

The main phytoplankton groups present in the Black Sea are

Marine mammals and marine

Marine mammals and marine

(pdf). Retrieved on 6 September 2017 However, construction of the Crimean Bridge has caused increases in nutrients and planktons in the waters, attracting large numbers of fish and more than 1,000 bottlenose dolphins. However, others claim that construction may cause devastating damages to the ecosystem, including dolphins. : Mediterranean monk seals, now a vulnerable species, were historically abundant in the Black Sea, and are regarded to have become extinct from the basin in 1997. Monk seals were present at Snake Island, near the

File:black sea fauna jelly 01.jpg,

The Black Sea is connected to the

The Black Sea is connected to the  There is evidence that water levels in the Black Sea were considerably lower at some point during the post-glacial period. Some researchers theorize that the Black Sea had been a landlocked freshwater lake (at least in upper layers) during the last glaciation and for some time after.

In the aftermath of the last glacial period, water levels in the Black Sea and the

There is evidence that water levels in the Black Sea were considerably lower at some point during the post-glacial period. Some researchers theorize that the Black Sea had been a landlocked freshwater lake (at least in upper layers) during the last glaciation and for some time after.

In the aftermath of the last glacial period, water levels in the Black Sea and the

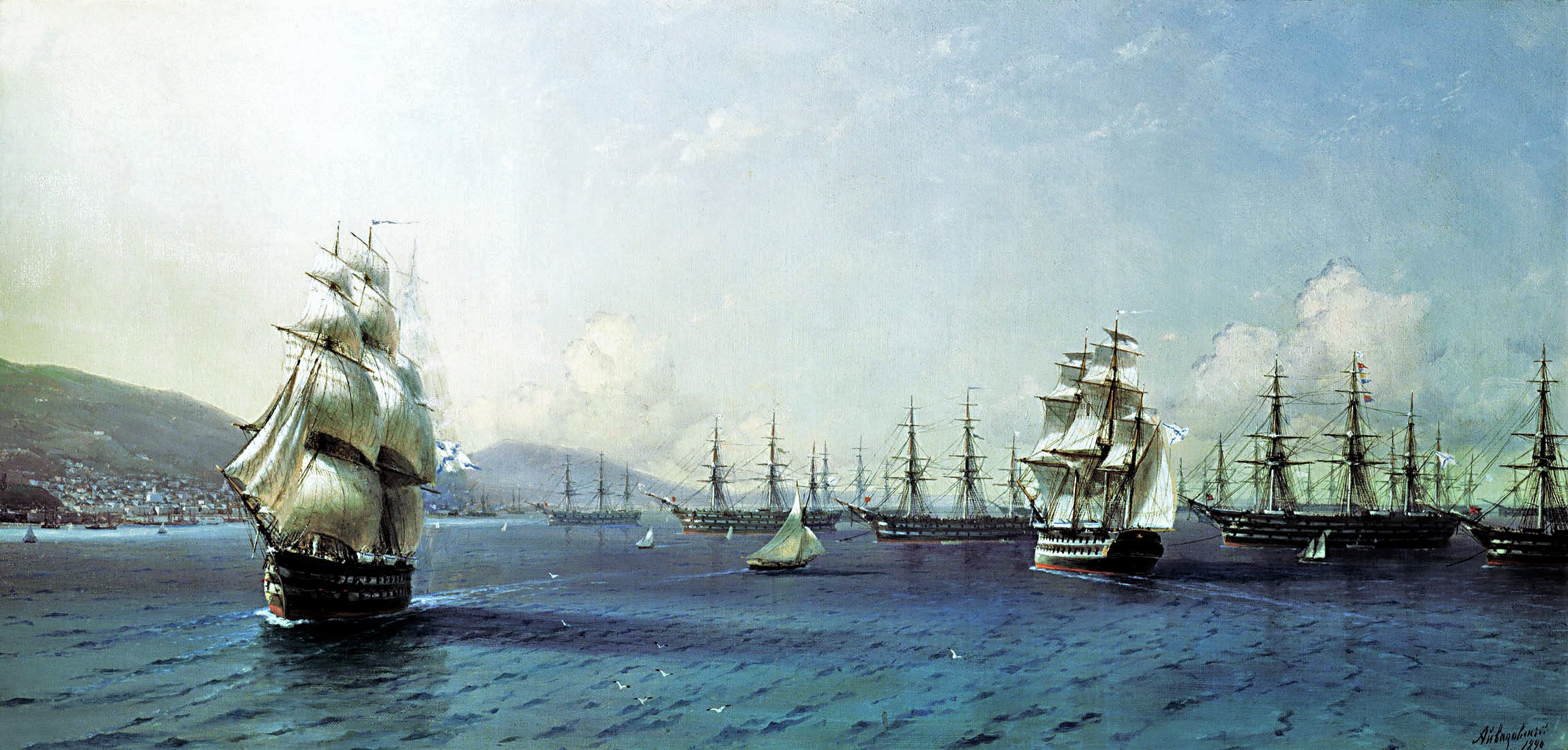

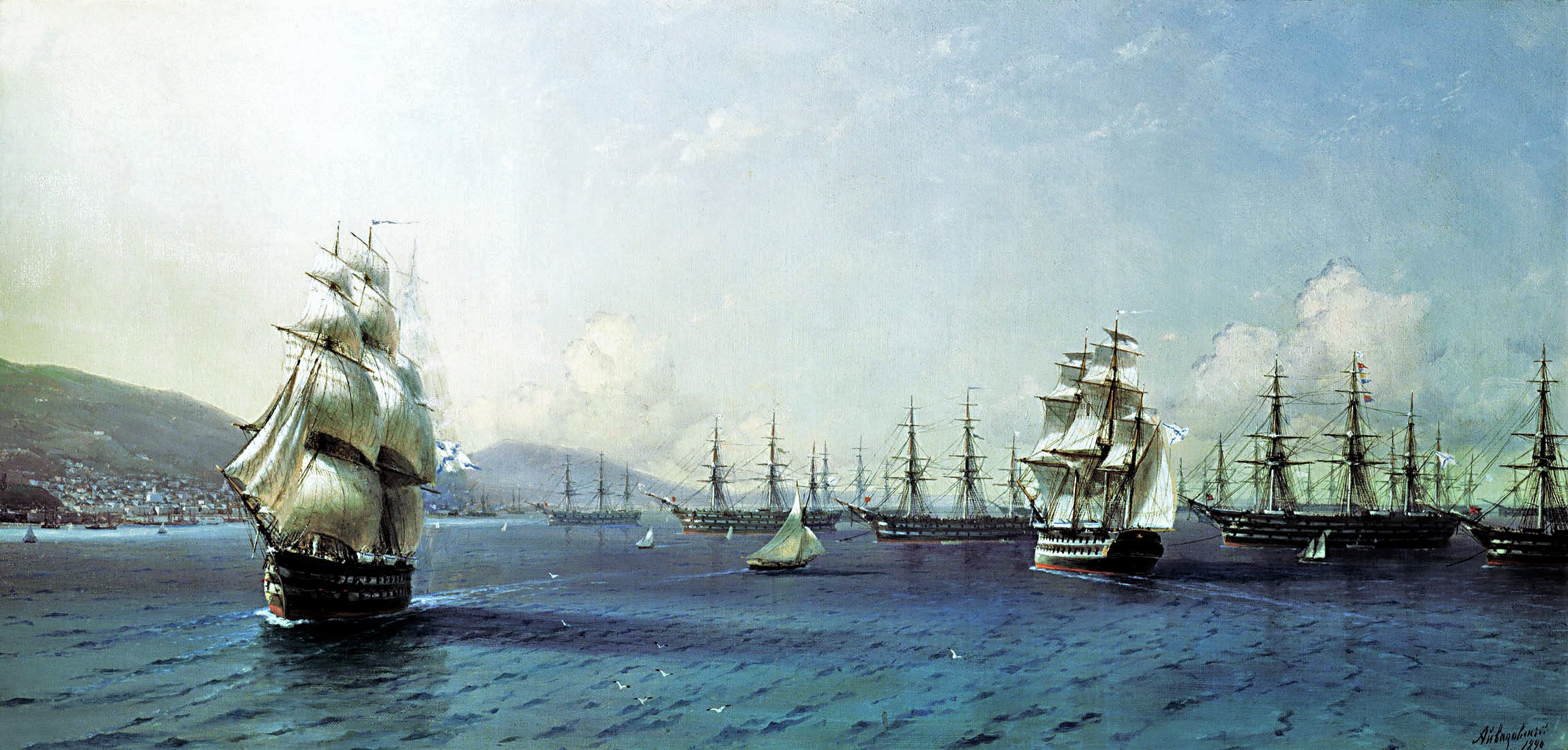

The Black Sea was sailed by

The Black Sea was sailed by

The Black Sea was a busy waterway on the crossroads of the ancient world: the

The Black Sea was a busy waterway on the crossroads of the ancient world: the  The

The

In the years following the end of the

In the years following the end of the

The Black Sea is a marginal

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

lying between Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

and Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

, east of the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region spanning Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising parts of Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains, i ...

, and north of Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

. It is bounded by Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

, Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

, Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

, and Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

. The Black Sea is supplied by major rivers, principally the Danube

The Danube ( ; see also #Names and etymology, other names) is the List of rivers of Europe#Longest rivers, second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest sou ...

, Dnieper

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

and Dniester

The Dniester ( ) is a transboundary river in Eastern Europe. It runs first through Ukraine and then through Moldova (from which it more or less separates the breakaway territory of Transnistria), finally discharging into the Black Sea on Uk ...

. Consequently, while six countries have a coastline on the sea, its drainage basin

A drainage basin is an area of land in which all flowing surface water converges to a single point, such as a river mouth, or flows into another body of water, such as a lake or ocean. A basin is separated from adjacent basins by a perimeter, ...

includes parts of 24 countries in Europe.

The Black Sea, not including the Sea of Azov

The Sea of Azov is an inland Continental shelf#Shelf seas, shelf sea in Eastern Europe connected to the Black Sea by the narrow (about ) Strait of Kerch, and sometimes regarded as a northern extension of the Black Sea. The sea is bounded by Ru ...

, covers , has a maximum depth of , and a volume of .

Most of its coasts ascend rapidly.

These rises are the Pontic Mountains to the south, bar the southwest-facing peninsulas, the Caucasus Mountains to the east, and the Crimean Mountains to the mid-north.

In the west, the coast is generally small floodplain

A floodplain or flood plain or bottomlands is an area of land adjacent to a river. Floodplains stretch from the banks of a river channel to the base of the enclosing valley, and experience flooding during periods of high Discharge (hydrolog ...

s below foothills such as the Strandzha; Cape Emine, a dwindling of the east end of the Balkan Mountains

The Balkan mountain range is located in the eastern part of the Balkan peninsula in Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It is conventionally taken to begin at the peak of Vrashka Chuka on the border between Bulgaria and Serbia. It then runs f ...

; and the Dobruja Plateau considerably farther north. The longest east–west extent is about . Important cities along the coast include (clockwise from the Bosporus

The Bosporus or Bosphorus Strait ( ; , colloquially ) is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul, Turkey. The Bosporus connects the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara and forms one of the continental bo ...

) Burgas

Burgas (, ), sometimes transliterated as Bourgas, is the second largest city on the Bulgarian Black Sea Coast in the region of Northern Thrace and the List of cities and towns in Bulgaria, fourth-largest city in Bulgaria after Sofia, Plovdiv, an ...

, Varna, Constanța

Constanța (, , ) is a city in the Dobruja Historical regions of Romania, historical region of Romania. A port city, it is the capital of Constanța County and the country's Cities in Romania, fourth largest city and principal port on the Black ...

, Odesa

Odesa, also spelled Odessa, is the third most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city and List of hromadas of Ukraine, municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern ...

, Sevastopol, Novorossiysk, Sochi

Sochi ( rus, Сочи, p=ˈsotɕɪ, a=Ru-Сочи.ogg, from – ''seaside'') is the largest Resort town, resort city in Russia. The city is situated on the Sochi (river), Sochi River, along the Black Sea in the North Caucasus of Souther ...

, Poti

Poti ( ka, ფოთი ; Mingrelian language, Mingrelian: ფუთი; Laz language, Laz: ჶაში/Faşi or ფაში/Paşi) is a port city in Georgia (country), Georgia, located on the eastern Black Sea coast in the mkhare, region of ...

, Batumi

Batumi (; ka, ბათუმი ), historically Batum or Batoum, is the List of cities and towns in Georgia (country), second-largest city of Georgia (country), Georgia and the capital of the Autonomous Republic of Adjara, located on the coast ...

, Trabzon

Trabzon, historically known as Trebizond, is a city on the Black Sea coast of northeastern Turkey and the capital of Trabzon Province. The city was founded in 756 BC as "Trapezous" by colonists from Miletus. It was added into the Achaemenid E ...

and Samsun

Samsun is a List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, city on the north coast of Turkey and a major Black Sea port. The urban area recorded a population of 738,692 in 2022. The city is the capital of Samsun Province which has a population of ...

.

The Black Sea has a positive water balance, with an annual net outflow of per year through the Bosporus and the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey th ...

into the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans and Anatolia, and covers an area of some . In the north, the Aegean is connected to the Marmara Sea, which in turn con ...

. While the net flow of water through the Bosporus and Dardanelles (known collectively as the Turkish Straits) is out of the Black Sea, water generally flows in both directions simultaneously: Denser, more saline water

Saline water (more commonly known as salt water) is water that contains a high concentration of dissolved salts (mainly sodium chloride). On the United States Geological Survey (USGS) salinity scale, saline water is saltier than brackish wat ...

from the Aegean flows into the Black Sea underneath the less dense, fresher water that flows out of the Black Sea. This creates a significant and permanent layer of deep water that does not drain or mix and is therefore anoxic

Anoxia means a total depletion in the level of oxygen, an extreme form of hypoxia or "low oxygen". The terms anoxia and hypoxia are used in various contexts:

* Anoxic waters, sea water, fresh water or groundwater that are depleted of dissolved ox ...

. This anoxic layer is responsible for the preservation of ancient shipwrecks which have been found in the Black Sea, which ultimately drains into the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

, via the Turkish Straits and the Aegean Sea. The Bosporus strait connects it to the small Sea of Marmara

The Sea of Marmara, also known as the Sea of Marmora or the Marmara Sea, is a small inland sea entirely within the borders of Turkey. It links the Black Sea and the Aegean Sea via the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits, separating Turkey's E ...

which in turn is connected to the Aegean Sea via the strait of the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey th ...

. To the north, the Black Sea is connected to the Sea of Azov by the Kerch Strait.

The water level has varied significantly over geological time. Due to these variations in the water level in the basin, the surrounding shelf and associated aprons have sometimes been dry land. At certain critical water levels, connections with surrounding water bodies can become established. It is through the most active of these connective routes, the Turkish Straits, that the Black Sea joins the World Ocean

The ocean is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of Earth. The ocean is conventionally divided into large bodies of water, which are also referred to as ''oceans'' (the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian, Antarctic/Southern, and ...

. During geological periods when this hydrological link was not present, the Black Sea was an endorheic basin

An endorheic basin ( ; also endoreic basin and endorreic basin) is a drainage basin that normally retains water and allows no outflow to other external bodies of water (e.g. rivers and oceans); instead, the water drainage flows into permanent ...

, operating independently of the global ocean system (similar to the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, described as the List of lakes by area, world's largest lake and usually referred to as a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia: east of the Caucasus, ...

today). Currently, the Black Sea water level is relatively high; thus, water is being exchanged with the Mediterranean. The Black Sea undersea river is a current of particularly saline water flowing through the Bosporus Strait and along the seabed

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as seabeds.

The structure of the seabed of the global ocean is governed by plate tectonics. Most of ...

of the Black Sea, the first of its kind discovered.

Name

Modern names

Current names of the sea are usually equivalents of the English name "Black Sea", including these given in the countries bordering the sea: * , * , * , * , * , * , * * , * Laz and , , or simply , , , "Sea" * , * , * , * , Such names have not yet been shown conclusively to predate the 13thcentury. InGreece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

, the historical name "Euxine Sea", which holds a different literal meaning (see below), is still widely used:

* , ; the name , , is used, but is much less common.

The Black Sea is one of four seas named in English after common color terms – the others being the Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

, the White Sea

The White Sea (; Karelian language, Karelian and ; ) is a southern inlet of the Barents Sea located on the northwest coast of Russia. It is surrounded by Karelia to the west, the Kola Peninsula to the north, and the Kanin Peninsula to the nort ...

and the Yellow Sea.

Historical names and etymology

The earliest known name of the Black Sea is the Sea of Zalpa, so called by both theHattians

The Hattians () were an ancient Bronze Age people that inhabited the land of ''Hatti'', in central Anatolia (modern Turkey). They spoke a distinctive Hattian language, which was neither Semitic languages, Semitic nor Indo-European languages, In ...

and their conquerors, the Hittites

The Hittites () were an Anatolian peoples, Anatolian Proto-Indo-Europeans, Indo-European people who formed one of the first major civilizations of the Bronze Age in West Asia. Possibly originating from beyond the Black Sea, they settled in mo ...

. The Hattic city of Zalpa was "situated probably at or near the estuary of the Marrassantiya River, the modern Kızıl Irmak, on the Black Sea coast."

The principal Greek name ''Póntos Áxeinos'' is generally accepted to be a rendering of the Iranian

Iranian () may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Iran

** Iranian diaspora, Iranians living outside Iran

** Iranian architecture, architecture of Iran and parts of the rest of West Asia

** Iranian cuisine, cooking traditions and practic ...

word ("dark colored"). Ancient Greek voyagers adopted the name as , identified with the Greek word (inhospitable). The name (Inhospitable Sea), first attested in Pindar

Pindar (; ; ; ) was an Greek lyric, Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes, Greece, Thebes. Of the Western canon, canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, "Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar i ...

(), was considered an ill omen and was euphemized to its opposite, (Hospitable Sea), also first attested in Pindar. This became the commonly used designation in Greek, although in mythological contexts the "true" name remained favored.

Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-si ...

's ''Geographica

The ''Geographica'' (, ''Geōgraphiká''; or , "Strabo's 17 Books on Geographical Topics") or ''Geography'', is an encyclopedia of geographical knowledge, consisting of 17 'books', written in Greek in the late 1st century BC, or early 1st cen ...

'' (1.2.10) reports that in antiquity, the Black Sea was often simply called "the Sea" ( ). He thought that the sea was called the "Inhospitable Sea" by the inhabitants of the Pontus region of the southern shoreline before Greek colonization due to its difficult navigation and hostile barbarian natives (7.3.6), and that the name was changed to "hospitable" after the Milesians colonized the region, bringing it into the Greek world.

Popular supposition derives "Black Sea" from the dark color of the water or climatic conditions. Some scholars understand the name to be derived from a system of color symbolism representing the cardinal directions, with black or dark for north, red for south, white for west, and green or light blue for east. Hence, "Black Sea" meant "Northern Sea". According to this scheme, the name could only have originated with a people living between the northern (black) and southern (red) seas: this points to the Achaemenids

The Achaemenid dynasty ( ; ; ; ) was a royal house that ruled the Achaemenid Empire, which eventually stretched from Egypt and Thrace in the west to Central Asia and the Indus Valley in the east.

Origins

The history of the Achaemenid dy ...

(550–330 BC). This interpretation has been labeled as folk etymology

Folk etymology – also known as (generative) popular etymology, analogical reformation, (morphological) reanalysis and etymological reinterpretation – is a change in a word or phrase resulting from the replacement of an unfamiliar form by a mo ...

and may reflect a primitive historical understanding of the "P/Bla" phoneme

A phoneme () is any set of similar Phone (phonetics), speech sounds that are perceptually regarded by the speakers of a language as a single basic sound—a smallest possible Phonetics, phonetic unit—that helps distinguish one word fr ...

originally associated with the name.Beekes, R. S. P. (2002). "The Origin of the Etruscans." Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen,AmsterdamRobert Beekes

/ref> In the Greater Bundahishn, a

Middle Persian

Middle Persian, also known by its endonym Pārsīk or Pārsīg ( Inscriptional Pahlavi script: , Manichaean script: , Avestan script: ) in its later form, is a Western Middle Iranian language which became the literary language of the Sasania ...

Zoroastrian scripture, the Black Sea is called . In the tenth-century Persian geography book , the Black Sea is called ''Georgian Sea'' (). '' The Georgian Chronicles'' use the name (Sea of Speri) after the Kartvelian tribe of Speris or Saspers. Other modern names such as and (both meaning Black Sea) originated during the 13th century. A 1570 map from Abraham Ortelius

Abraham Ortelius (; also Ortels, Orthellius, Wortels; 4 or 14 April 152728 June 1598) was a cartographer, geographer, and cosmographer from Antwerp in the Spanish Netherlands. He is recognized as the creator of the list of atlases, first modern ...

's labels the sea (Great Sea), compare Latin .

English writers of the 18th century often used ''Euxine Sea'' ( or ). During the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, it was called either (Perso-Arabic

The Persian alphabet (), also known as the Perso-Arabic script, is the right-to-left script, right-to-left alphabet used for the Persian language. It is a variation of the Arabic script with four additional letters: (the sounds 'g', 'zh', ' ...

) or (Ottoman Turkish

Ottoman Turkish (, ; ) was the standardized register of the Turkish language in the Ottoman Empire (14th to 20th centuries CE). It borrowed extensively, in all aspects, from Arabic and Persian. It was written in the Ottoman Turkish alphabet. ...

), both meaning "Black Sea".

Geography

TheInternational Hydrographic Organization

The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) (French: ''Organisation Hydrographique Internationale'') is an intergovernmental organization representing hydrography. the IHO comprised 102 member states.

A principal aim of the IHO is to ...

defines the limits of the Black Sea as follows:

The area surrounding the Black Sea is commonly referred to as the ''Black Sea Region''. Its northern part lies within the '' Chernozem belt'' (black soil belt) which goes from eastern Croatia (Slavonia

Slavonia (; ) is, with Dalmatia, Croatia proper, and Istria County, Istria, one of the four Regions of Croatia, historical regions of Croatia. Located in the Pannonian Plain and taking up the east of the country, it roughly corresponds with f ...

), along the Danube

The Danube ( ; see also #Names and etymology, other names) is the List of rivers of Europe#Longest rivers, second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest sou ...

(northern Serbia, northern Bulgaria ( Danubian Plain) and southern Romania ( Wallachian Plain) to northeast Ukraine and further across the Central Black Earth Region and southern Russia into Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

.

The littoral zone

The littoral zone, also called litoral or nearshore, is the part of a sea, lake, or river that is close to the shore. In coastal ecology, the littoral zone includes the intertidal zone extending from the high water mark (which is rarely flood ...

of the Black Sea is often referred to as the Pontic littoral or Pontic zone.

The largest bays of the Black Sea are Karkinit Bay in Ukraine; the Gulf of Burgas in Bulgaria; Dnieprovska Gulf and Dniestrovsky Liman, both in Ukraine; and Sinop Bay and Samsun

Samsun is a List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, city on the north coast of Turkey and a major Black Sea port. The urban area recorded a population of 738,692 in 2022. The city is the capital of Samsun Province which has a population of ...

Bay, both in Turkey.

Coastline and exclusive economic zones

Drainage basin

The largestriver

A river is a natural stream of fresh water that flows on land or inside Subterranean river, caves towards another body of water at a lower elevation, such as an ocean, lake, or another river. A river may run dry before reaching the end of ...

s flowing into the Black Sea are:

# Danube

The Danube ( ; see also #Names and etymology, other names) is the List of rivers of Europe#Longest rivers, second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest sou ...

# Dnieper

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

# Don

# Dniester

The Dniester ( ) is a transboundary river in Eastern Europe. It runs first through Ukraine and then through Moldova (from which it more or less separates the breakaway territory of Transnistria), finally discharging into the Black Sea on Uk ...

# Kızılırmak

# Kuban

# Sakarya

# Southern Bug

# Çoruh/Chorokhi

# Yeşilırmak

# Rioni

# Yeya

# Mius

# Kamchiya

# Enguri/Egry

# Kalmius

# Molochna

# Tylihul

# Velykyi Kuialnyk

# Veleka

# Rezovo

# Kodori/Kwydry

# Bzyb/Bzipi

# Supsa

# Mzymta

These rivers and their tributaries comprise a Black Sea drainage basin that covers wholly or partially 24 countries:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Unrecognized states:

*

Islands

Some islands in the Black Sea belong to Bulgaria, Romania, Turkey, and Ukraine: * St. Thomas Island – Bulgaria * St. Anastasia Island – Bulgaria * St. Cyricus Island – Bulgaria * St. Ivan Island – Bulgaria * St. Peter Island – Bulgaria * Sacalinu Mare Island – Romania * Sacalinu Mic Island – Romania * K Island – Romania and Ukraine * Utrish Island * Krupinin Island * Sudiuk Island * Kefken Island * Oreke Island * Giresun Island – Turkey * Dzharylhach Island – Ukraine * Zmiinyi (Snake) Island – UkraineClimate

Short-term climatic variation in the Black Sea region is significantly influenced by the operation of the North Atlantic oscillation, the climatic mechanisms resulting from the interaction between the north Atlantic and mid-latitude air masses. While the exact mechanisms causing the North Atlantic Oscillation remain unclear, it is thought the climate conditions established in western Europe mediate the heat and precipitation fluxes reaching Central Europe and Eurasia, regulating the formation of winter

Short-term climatic variation in the Black Sea region is significantly influenced by the operation of the North Atlantic oscillation, the climatic mechanisms resulting from the interaction between the north Atlantic and mid-latitude air masses. While the exact mechanisms causing the North Atlantic Oscillation remain unclear, it is thought the climate conditions established in western Europe mediate the heat and precipitation fluxes reaching Central Europe and Eurasia, regulating the formation of winter cyclone

In meteorology, a cyclone () is a large air mass that rotates around a strong center of low atmospheric pressure, counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere as viewed from above (opposite to an ant ...

s, which are largely responsible for regional precipitation

In meteorology, precipitation is any product of the condensation of atmospheric water vapor that falls from clouds due to gravitational pull. The main forms of precipitation include drizzle, rain, rain and snow mixed ("sleet" in Commonwe ...

inputs and influence Mediterranean sea surface temperatures (SSTs).

The relative strength of these systems also limits the amount of cold air arriving from northern regions during winter. Other influencing factors include the regional topography

Topography is the study of the forms and features of land surfaces. The topography of an area may refer to the landforms and features themselves, or a description or depiction in maps.

Topography is a field of geoscience and planetary sci ...

, as depressions and storm systems arriving from the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

are funneled through the low land around the Bosporus, with the Pontic and Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region spanning Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising parts of Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains, i ...

mountain ranges acting as waveguides, limiting the speed and paths of cyclones passing through the region.

Geology and bathymetry

The Black Sea is divided into two depositional basins—the Western Black Sea and Eastern Black Sea—separated by the Mid-Black Sea High, which includes the Andrusov Ridge, Tetyaev High, and Archangelsky High, extending south from the Crimean Peninsula. The basin includes two distinct relictback-arc basin

A back-arc basin is a type of geologic Structural basin, basin, found at some convergent boundary, convergent plate boundaries. Presently all back-arc basins are submarine features associated with island arcs and subduction zones, with many found ...

s which were initiated by the splitting of an Albian

The Albian is both an age (geology), age of the geologic timescale and a stage (stratigraphy), stage in the stratigraphic column. It is the youngest or uppermost subdivision of the Early Cretaceous, Early/Lower Cretaceous epoch (geology), Epoch/s ...

volcanic arc

A volcanic arc (also known as a magmatic arc) is a belt of volcanoes formed above a subducting oceanic tectonic plate, with the belt arranged in an arc shape as seen from above. Volcanic arcs typically parallel an oceanic trench, with the arc ...

and the subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere and some continental lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at the convergent boundaries between tectonic plates. Where one tectonic plate converges with a second p ...

of both the Paleo- and Neo- Tethys oceans, but the timings of these events remain uncertain. Arc volcanism and extension occurred as the Neo-Tethys Ocean subducted under the southern margin of Laurasia

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around ( Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pa ...

during the Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era is the Era (geology), era of Earth's Geologic time scale, geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous Period (geology), Periods. It is characterized by the dominance of archosaurian r ...

. Uplift and compressional deformation took place as the Neotethys continued to close. Seismic surveys indicate that rifting began in the Western Black Sea in the Barremian

The Barremian is an age in the geologic timescale (or a chronostratigraphic stage) between 125.77 Ma (million years ago) and 121.4 ± 1.0 Ma (Historically, this stage was placed at 129.4 million to approximately 125 million years ago) It is a ...

and Aptian

The Aptian is an age (geology), age in the geologic timescale or a stage (stratigraphy), stage in the stratigraphic column. It is a subdivision of the Early Cretaceous, Early or Lower Cretaceous epoch (geology), Epoch or series (stratigraphy), S ...

followed by the formation of oceanic crust 20million years later in the Santonian

The Santonian is an age in the geologic timescale or a chronostratigraphic stage. It is a subdivision of the Late Cretaceous Epoch or Upper Cretaceous Series. It spans the time between 86.3 ± 0.7 mya ( million years ago) and 83.6 ± 0.7 m ...

. Since its initiation, compressional tectonic environments led to subsidence

Subsidence is a general term for downward vertical movement of the Earth's surface, which can be caused by both natural processes and human activities. Subsidence involves little or no horizontal movement, which distinguishes it from slope mov ...

in the basin, interspersed with extensional phases resulting in large-scale volcanism and numerous orogenies, causing the uplift of the Greater Caucasus, Pontides, southern Crimean Peninsula and Balkanides mountain ranges.

During the Messinian salinity crisis

In the Messinian salinity crisis (also referred to as the Messinian event, and in its latest stage as the Lago Mare event) the Mediterranean Sea went into a cycle of partial or nearly complete desiccation (drying-up) throughout the latter part of ...

in the neighboring Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

, water levels fell but without drying up the sea. The collision between the Eurasian and African plates and the westward escape of the Anatolian block along the North Anatolian and East Anatolian faults dictates the current tectonic regime, which features enhanced subsidence in the Black Sea basin and significant volcanic activity in the Anatolian region. These geological mechanisms, in the long term, have caused the periodic isolations of the Black Sea from the rest of the global ocean system.

The large shelf to the north of the basin is up to wide and features a shallow apron with gradients between 1:40 and 1:1000. The southern edge around Turkey and the eastern edge around Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

, however, are typified by a narrow shelf that rarely exceeds in width and a steep apron that is typically 1:40 gradient with numerous submarine canyons and channel extensions. The Euxine abyssal plain in the center of the Black Sea reaches a maximum depth of just south of Yalta on the Crimean Peninsula.

Chronostratigraphy

The Paleo- Euxinian is described by the accumulation of eolian silt deposits (related to the Riss glaciation) and the lowering of sea levels ( MIS 6, 8 and 10). The Karangat marine transgression occurred during the EemianInterglacial

An interglacial period (or alternatively interglacial, interglaciation) is a geological interval of warmer global average temperature lasting thousands of years that separates consecutive glacial periods within an ice age. The current Holocene i ...

(MIS 5e). This may have been the highest sea levels reached in the late Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( ; referred to colloquially as the ''ice age, Ice Age'') is the geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fin ...

. Based on this some scholars have suggested that the Crimean Peninsula was isolated from the mainland by a shallow strait during the Eemian Interglacial.

The Neoeuxinian transgression began with an inflow of waters from the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, described as the List of lakes by area, world's largest lake and usually referred to as a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia: east of the Caucasus, ...

. Neoeuxinian deposits are found in the Black Sea below water depth in three layers. The upper layers correspond with the peak of the Khvalinian transgression, on the shelf shallow-water sands and coquina mixed with silty sands and brackish-water fauna, and inside the Black Sea Depression hydrotroilite silts. The middle layers on the shelf are sands with brackish-water mollusc shells. Of continental origin, the lower level on the shelf is mostly alluvial

Alluvium (, ) is loose clay, silt, sand, or gravel that has been deposited by running water in a stream bed, on a floodplain, in an alluvial fan or beach, or in similar settings. Alluvium is also sometimes called alluvial deposit. Alluvium is ...

sands with pebbles, mixed with less common lacustrine silts and freshwater mollusc shell

The mollusc (or mollusk) shell is typically a calcareous exoskeleton which encloses, supports and protects the soft parts of an animal in the phylum Mollusca, which includes snails, clams, tusk shells, and several other classes. Not all shelled ...

s. Inside the Black Sea Depression they are terrigenous non-carbonate silt

Silt is granular material of a size between sand and clay and composed mostly of broken grains of quartz. Silt may occur as a soil (often mixed with sand or clay) or as sediment mixed in suspension (chemistry), suspension with water. Silt usually ...

s, and at the foot of the continental slope turbidite

A turbidite is the geologic Deposition (geology), deposit of a turbidity current, which is a type of amalgamation of fluidal and sediment gravity flow responsible for distributing vast amounts of clastic sediment into the deep ocean.

Sequencing

...

sediments.

Hydrology

The Black Sea is the world's largest body of water with a meromictic basin. The deep waters do not mix with the upper layers of water that receive oxygen from the atmosphere. As a result, over 90% of the deeper Black Sea volume is

The Black Sea is the world's largest body of water with a meromictic basin. The deep waters do not mix with the upper layers of water that receive oxygen from the atmosphere. As a result, over 90% of the deeper Black Sea volume is anoxic

Anoxia means a total depletion in the level of oxygen, an extreme form of hypoxia or "low oxygen". The terms anoxia and hypoxia are used in various contexts:

* Anoxic waters, sea water, fresh water or groundwater that are depleted of dissolved ox ...

water. The Black Sea's circulation patterns are primarily controlled by basin topography and fluvial

A river is a natural stream of fresh water that flows on land or inside caves towards another body of water at a lower elevation, such as an ocean, lake, or another river. A river may run dry before reaching the end of its course if it ru ...

inputs, which result in a strongly stratified vertical structure. Because of the extreme stratification, it is classified as a salt wedge estuary.

Inflow from the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

through the Bosporus

The Bosporus or Bosphorus Strait ( ; , colloquially ) is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul, Turkey. The Bosporus connects the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara and forms one of the continental bo ...

and Dardanelles

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey th ...

has a higher salinity and density than the outflow, creating the classic estuarine circulation. This means that the inflow of dense water from the Mediterranean occurs at the bottom of the basin while the outflow of fresher Black Sea surface-water into the Sea of Marmara

The Sea of Marmara, also known as the Sea of Marmora or the Marmara Sea, is a small inland sea entirely within the borders of Turkey. It links the Black Sea and the Aegean Sea via the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits, separating Turkey's E ...

occurs near the surface. According to Gregg (2002), the outflow is or around , and the inflow is or around .Gregg, M. C., and E. Özsoy (2002), "Flow, water mass changes, and hydraulics in the Bosporus", ''Journal of Geophysical Research'' 107(C3), 3016,

The following water budget can be estimated:

* Water in:

** Total river discharge:

** Precipitation:

** Inflow via Bosporus:

* Water out:

** Evaporation: (reduced greatly since the 1970s)

** Outflow via Bosporus:

The southern sill of the Bosporus is located at below present sea level (deepest spot of the shallowest cross-section in the Bosporus, located in front of Dolmabahçe Palace) and has a wet section of around . Inflow and outflow current speeds are averaged around , but much higher speeds are found locally, inducing significant turbulence and vertical shear. This allows for turbulent mixing of the two layers.''Descriptive Physical Oceanography''. Talley, Pickard, Emery, Swift. Surface water leaves the Black Sea with a salinity of 17 practical salinity units (PSU) and reaches the Mediterranean with a salinity of 34 PSU. Likewise, an inflow of the Mediterranean with salinity 38.5 PSU experiences a decrease to about 34 PSU.

Mean surface circulation is cyclonic; waters around the perimeter of the Black Sea circulate in a basin-wide shelfbreak gyre known as the Rim Current. The Rim Current has a maximum velocity of about . Within this feature, two smaller cyclonic gyres operate, occupying the eastern and western sectors of the basin. The Eastern and Western Gyres are well-organized systems in the winter but dissipate into a series of interconnected eddies in the summer and autumn. Mesoscale activity in the peripheral flow becomes more pronounced during these warmer seasons and is subject to interannual variability.

Outside of the Rim Current, numerous quasi-permanent coastal eddies are formed as a result of upwelling

Upwelling is an physical oceanography, oceanographic phenomenon that involves wind-driven motion of dense, cooler, and usually nutrient-rich water from deep water towards the ocean surface. It replaces the warmer and usually nutrient-depleted sur ...

around the coastal apron and "wind curl" mechanisms. The intra-annual strength of these features is controlled by seasonal atmospheric and fluvial variations. During the spring, the Batumi eddy forms in the southeastern corner of the sea.

Beneath the surface waters—from about —there exists a halocline

A halocline (or salinity chemocline), from the Greek words ''hals'' (salt) and ''klinein'' (to slope), refers to a layer within a body of water ( water column) where there is a sharp change in salinity (salt concentration) with depth.

Haloclin ...

that stops at the Cold Intermediate Layer (CIL). This layer is composed of cool, salty surface waters, which are the result of localized atmospheric cooling and decreased fluvial input during the winter months. It is the remnant of the winter surface mixed layer. The base of the CIL is marked by a major pycnocline at about , and this density disparity is the major mechanism for isolation of the deep water.

Below the pycnocline is the Deep Water mass, where salinity increases to 22.3 PSU and temperatures rise to around . The hydrochemical environment shifts from oxygenated to anoxic, as bacterial decomposition of sunken biomass utilizes all of the free oxygen. Weak geothermal heating and long residence time create a very thick convective bottom layer.

The Black Sea undersea river is a current of particularly saline water flowing through the Bosporus Strait and along the

Below the pycnocline is the Deep Water mass, where salinity increases to 22.3 PSU and temperatures rise to around . The hydrochemical environment shifts from oxygenated to anoxic, as bacterial decomposition of sunken biomass utilizes all of the free oxygen. Weak geothermal heating and long residence time create a very thick convective bottom layer.

The Black Sea undersea river is a current of particularly saline water flowing through the Bosporus Strait and along the seabed

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as seabeds.

The structure of the seabed of the global ocean is governed by plate tectonics. Most of ...

of the Black Sea. The discovery of the river, announced on 1 August 2010, was made by scientists at the University of Leeds

The University of Leeds is a public research university in Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. It was established in 1874 as the Yorkshire College of Science. In 1884, it merged with the Leeds School of Medicine (established 1831) and was renamed Y ...

and is the first of its kind to be identified. The undersea river stems from salty water spilling through the Bosporus Strait from the Mediterranean Sea into the Black Sea, where the water has a lower salt content.

Hydrochemistry

Because of the anoxic water at depth, organic matter, includinganthropogenic

Anthropogenic ("human" + "generating") is an adjective that may refer to:

* Anthropogeny, the study of the origins of humanity

Anthropogenic may also refer to things that have been generated by humans, as follows:

* Human impact on the enviro ...

artifacts such as boat hulls, are well preserved. During periods of high surface productivity, short-lived algal bloom

An algal bloom or algae bloom is a rapid increase or accumulation in the population of algae in fresh water or marine water systems. It is often recognized by the discoloration in the water from the algae's pigments. The term ''algae'' encompass ...

s form organic rich layers known as sapropels. Scientists have reported an annual phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater Aquatic ecosystem, ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek language, Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), mea ...

bloom that can be seen in many NASA images of the region. As a result of these characteristics the Black Sea has gained interest from the field of marine archaeology, as ancient shipwrecks in excellent states of preservation have been discovered, such as the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

wreck Sinop D, located in the anoxic layer off the coast of Sinop, Turkey.

Modelling shows that, in the event of an asteroid impact

An impact event is a collision between astronomical objects causing measurable effects. Impact events have been found to regularly occur in planetary systems, though the most frequent involve asteroids, comets or meteoroids and have minimal effe ...

on the Black Sea, the release of hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is toxic, corrosive, and flammable. Trace amounts in ambient atmosphere have a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. Swedish chemist ...

clouds would pose a threat to health—and perhaps even life—for people living on the Black Sea coast.

There have been isolated reports of flares on the Black Sea occurring during thunderstorms, possibly caused by lightning igniting combustible gas seeping up from the sea depths.

Ecology

Marine

autotroph

An autotroph is an organism that can convert Abiotic component, abiotic sources of energy into energy stored in organic compounds, which can be used by Heterotroph, other organisms. Autotrophs produce complex organic compounds (such as carbohy ...

ic algae, including diatom

A diatom (Neo-Latin ''diatoma'') is any member of a large group comprising several Genus, genera of algae, specifically microalgae, found in the oceans, waterways and soils of the world. Living diatoms make up a significant portion of Earth's B ...

s and dinoflagellate

The Dinoflagellates (), also called Dinophytes, are a monophyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes constituting the phylum Dinoflagellata and are usually considered protists. Dinoflagellates are mostly marine plankton, but they are also commo ...

s, acting as primary producers. The fluvial systems draining Eurasia and central Europe introduce large volumes of sediment and dissolved nutrients into the Black Sea, but the distribution of these nutrients is controlled by the degree of physiochemical stratification, which is, in turn, dictated by seasonal physiographic development.

During winter, strong winds promote convective overturning and upwelling of nutrients, while high summer temperatures result in marked vertical stratification and a warm, shallow mixed layer. Day length and insolation

Solar irradiance is the power per unit area ( surface power density) received from the Sun in the form of electromagnetic radiation in the wavelength range of the measuring instrument.

Solar irradiance is measured in watts per square metre ...

intensity also control the extent of the photic zone

The photic zone (or euphotic zone, epipelagic zone, or sunlight zone) is the uppermost layer of a body of water that receives sunlight, allowing phytoplankton to perform photosynthesis. It undergoes a series of physical, chemical, and biological ...

. Subsurface productivity is limited by nutrient availability, as the anoxic bottom waters act as a sink for reduced nitrate

Nitrate is a polyatomic ion with the chemical formula . salt (chemistry), Salts containing this ion are called nitrates. Nitrates are common components of fertilizers and explosives. Almost all inorganic nitrates are solubility, soluble in wa ...

, in the form of ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic chemical compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the chemical formula, formula . A Binary compounds of hydrogen, stable binary hydride and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinctive pu ...

. The benthic zone

The benthic zone is the ecological region at the lowest level of a body of water such as an ocean, lake, or stream, including the sediment surface and some sub-surface layers. The name comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning "the depths". ...

also plays an important role in Black Sea nutrient cycling, as chemosynthetic organisms and anoxic geochemical pathways recycle nutrients which can be upwelled to the photic zone, enhancing productivity.

In total, the Black Sea's biodiversity contains around one-third of the Mediterranean's and is experiencing natural and artificial invasions or "Mediterranizations".

Phytoplankton

The main phytoplankton groups present in the Black Sea are

The main phytoplankton groups present in the Black Sea are dinoflagellate

The Dinoflagellates (), also called Dinophytes, are a monophyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes constituting the phylum Dinoflagellata and are usually considered protists. Dinoflagellates are mostly marine plankton, but they are also commo ...

s, diatom

A diatom (Neo-Latin ''diatoma'') is any member of a large group comprising several Genus, genera of algae, specifically microalgae, found in the oceans, waterways and soils of the world. Living diatoms make up a significant portion of Earth's B ...

s, coccolithophore

Coccolithophores, or coccolithophorids, are single-celled organisms which are part of the phytoplankton, the autotrophic (self-feeding) component of the plankton community. They form a group of about 200 species, and belong either to the kingdom ...

s and cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

. Generally, the annual cycle of phytoplankton development comprises significant diatom and dinoflagellate-dominated spring production, followed by a weaker mixed assemblage of community development below the seasonal thermocline during summer months, and surface-intensified autumn production. This pattern of productivity is augmented by an ''Emiliania huxleyi

''Gephyrocapsa huxleyi'', also called ''Emiliania huxleyi'', is the most abundant species of coccolithophore in modern oceans found in almost all ecosystems from the equator to sub-polar regions, and from nutrient rich upwelling zones to nutr ...

'' bloom during the late spring and summer months.

* Dinoflagellate

The Dinoflagellates (), also called Dinophytes, are a monophyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes constituting the phylum Dinoflagellata and are usually considered protists. Dinoflagellates are mostly marine plankton, but they are also commo ...

s

: Annual dinoflagellate distribution is defined by an extended bloom period in subsurface waters during the late spring and summer. In November, subsurface plankton production is combined with surface production, due to vertical mixing of water masses and nutrients such as nitrite

The nitrite polyatomic ion, ion has the chemical formula . Nitrite (mostly sodium nitrite) is widely used throughout chemical and pharmaceutical industries. The nitrite anion is a pervasive intermediate in the nitrogen cycle in nature. The name ...

. The major bloom-forming dinoflagellate species in the Black Sea is '' Gymnodinium'' sp. Estimates of dinoflagellate diversity in the Black Sea range from 193 to 267 species. This level of species richness is relatively low in comparison to the Mediterranean Sea, which is attributable to the brackish conditions, low water transparency and presence of anoxic

Anoxia means a total depletion in the level of oxygen, an extreme form of hypoxia or "low oxygen". The terms anoxia and hypoxia are used in various contexts:

* Anoxic waters, sea water, fresh water or groundwater that are depleted of dissolved ox ...

bottom waters. It is also possible that the low winter temperatures below of the Black Sea prevent thermophilous species from becoming established. The relatively high organic matter content of Black Sea surface water favors the development of heterotroph

A heterotroph (; ) is an organism that cannot produce its own food, instead taking nutrition from other sources of organic carbon, mainly plant or animal matter. In the food chain, heterotrophs are primary, secondary and tertiary consumers, but ...

ic (an organism that uses organic carbon for growth) and mixotrophic dinoflagellates species (able to exploit different trophic pathways), relative to autotrophs. Despite its unique hydrographic setting, there are no confirmed endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

dinoflagellate species in the Black Sea.

* Diatom

A diatom (Neo-Latin ''diatoma'') is any member of a large group comprising several Genus, genera of algae, specifically microalgae, found in the oceans, waterways and soils of the world. Living diatoms make up a significant portion of Earth's B ...

s

: The Black Sea is populated by many species of the marine diatom, which commonly exist as colonies of unicellular

A unicellular organism, also known as a single-celled organism, is an organism that consists of a single cell, unlike a multicellular organism that consists of multiple cells. Organisms fall into two general categories: prokaryotic organisms and ...

, non-motile auto- and heterotrophic algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthesis, photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular ...

. The life-cycle of most diatoms can be described as 'boom and bust' and the Black Sea is no exception, with diatom blooms occurring in surface waters throughout the year, most reliably during March. In simple terms, the phase of rapid population growth in diatoms is caused by the in-wash of silicon

Silicon is a chemical element; it has symbol Si and atomic number 14. It is a hard, brittle crystalline solid with a blue-grey metallic lustre, and is a tetravalent metalloid (sometimes considered a non-metal) and semiconductor. It is a membe ...

-bearing terrestrial sediments, and when the supply of silicon is exhausted, the diatoms begin to sink out of the photic zone and produce resting cysts. Additional factors such as predation by zooplankton and ammonium

Ammonium is a modified form of ammonia that has an extra hydrogen atom. It is a positively charged (cationic) polyatomic ion, molecular ion with the chemical formula or . It is formed by the protonation, addition of a proton (a hydrogen nucleu ...

-based regenerated production also have a role to play in the annual diatom cycle. Typically, blooms during spring and blooms during the autumn.

* Coccolithophore

Coccolithophores, or coccolithophorids, are single-celled organisms which are part of the phytoplankton, the autotrophic (self-feeding) component of the plankton community. They form a group of about 200 species, and belong either to the kingdom ...

s

: Coccolithophores are a type of motile, autotrophic phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater Aquatic ecosystem, ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek language, Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), mea ...

that produce CaCO3 plates, known as coccoliths, as part of their life cycle. In the Black Sea, the main period of coccolithophore growth occurs after the bulk of the dinoflagellate growth has taken place. In May, the dinoflagellates move below the seasonal thermocline into deeper waters, where more nutrients are available. This permits coccolithophores to utilize the nutrients in the upper waters, and by the end of May, with favorable light and temperature conditions, growth rates reach their highest. The major bloom-forming species is , which is also responsible for the release of dimethyl sulfide

Dimethyl sulfide (DMS) or methylthiomethane is an organosulfur compound with the formula . It is the simplest thioether and has a characteristic disagreeable odor. It is a flammable liquid that boils at . It is a component of the smell produc ...

into the atmosphere. Overall, coccolithophore diversity is low in the Black Sea, and although recent sediments are dominated by and , Holocene

The Holocene () is the current geologic time scale, geological epoch, beginning approximately 11,700 years ago. It follows the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene to ...

sediments have been shown to also contain Helicopondosphaera and Discolithina species.

* Cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

: Cyanobacteria are a phylum of picoplankton

Picoplankton is the fraction of plankton composed by cell (biology), cells between 0.2 and 2 μm that can be either prokaryotic and eukaryotic phototrophs and heterotrophs:

* photosynthetic

* heterotrophic

They are prevalent amongst microbial p ...

ic (plankton ranging in size from 0.2 to 2.0 μm) bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

that obtain their energy via photosynthesis

Photosynthesis ( ) is a system of biological processes by which photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical energy necessary to fuel their metabo ...

, and are present throughout the world's oceans. They exhibit a range of morphologies, including filamentous colonies and biofilm

A biofilm is a Syntrophy, syntrophic Microbial consortium, community of microorganisms in which cell (biology), cells cell adhesion, stick to each other and often also to a surface. These adherent cells become embedded within a slimy ext ...

s. In the Black Sea, several species are present, and as an example, ''Synechococcus'' spp. can be found throughout the photic zone, although concentration decreases with increasing depth. Other factors which exert an influence on distribution include nutrient availability, predation, and salinity.

Animal species

*Zebra mussel

The zebra mussel (''Dreissena polymorpha'') is a small freshwater mussel, an Aquatic animal, aquatic bivalve mollusk in the family Dreissenidae. The species originates from the lakes of southern Russia and Ukraine, but has been accidentally Intro ...

: The Black Sea along with the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, described as the List of lakes by area, world's largest lake and usually referred to as a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia: east of the Caucasus, ...

is part of the zebra mussel's native range. The mussel has been accidentally introduced around the world and become an invasive species

An invasive species is an introduced species that harms its new environment. Invasive species adversely affect habitats and bioregions, causing ecological, environmental, and/or economic damage. The term can also be used for native spec ...

where it has been introduced.

* Common carp

: The common carp's native range extends to the Black Sea along with the Caspian Sea and Aral Sea. Like the zebra mussel, the common carp is an invasive species when introduced to other habitats.

* Round goby

The round goby (''Neogobius melanostomus'') is a euryhaline bottom-dwelling species of fish of the family (biology), family Gobiidae. It is native to Central Eurasia, including the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. Round gobies have established larg ...

: Another native fish that is also found in the Caspian Sea. It preys upon zebra mussels. Like the mussels and common carp, it has become invasive when introduced to other environments, like the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes spanning the Canada–United States border. The five lakes are Lake Superior, Superior, Lake Michigan, Michigan, Lake Huron, H ...

in North America.

*  Marine mammals and marine

Marine mammals and marine megafauna

In zoology, megafauna (from Ancient Greek, Greek μέγας ''megas'' "large" and Neo-Latin ''fauna'' "animal life") are large animals. The precise definition of the term varies widely, though a common threshold is approximately , this lower en ...

: Marine mammals present within the basin include two species of dolphin (common

Common may refer to:

As an Irish surname, it is anglicised from Irish Gaelic surname Ó Comáin.

Places

* Common, a townland in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland

* Boston Common, a central public park in Boston, Massachusetts

* Cambridge Com ...

and bottlenose) and the harbour porpoise

The harbour porpoise (''Phocoena phocoena'') is one of eight extant species of porpoise. It is one of the smallest species of cetacean. As its name implies, it stays close to coastal areas or river estuaries, and as such, is the most familiar ...

, although all of these are endangered due to pressures and impacts by human activities. All three species have been classified as distinct subspecies from those in the Mediterranean and the Atlantic and are endemic to the Black and Azov seas, and are more active during nights in the Turkish Straits.First stranding record of a Risso's Dolphin (Grampus griseus) in the Marmara Sea, Turkey(pdf). Retrieved on 6 September 2017 However, construction of the Crimean Bridge has caused increases in nutrients and planktons in the waters, attracting large numbers of fish and more than 1,000 bottlenose dolphins. However, others claim that construction may cause devastating damages to the ecosystem, including dolphins. : Mediterranean monk seals, now a vulnerable species, were historically abundant in the Black Sea, and are regarded to have become extinct from the basin in 1997. Monk seals were present at Snake Island, near the

Danube Delta

The Danube Delta (, ; , ) is the second largest river delta in Europe, after the Volga Delta, and is the best preserved on the continent. Occurring where the Danube, Danube River empties into the Black Sea, most of the Danube Delta lies in Romania ...

, until the 1950s, and several locations such as the and Doğankent were the last of the seals' hauling-out

Hauling out is a ethology, behaviour associated with pinnipeds (true seals, sea lions, fur seals and walruses) temporarily leaving the water. Hauling-out typically occurs between periods of foraging activity. Rather than remain in the water, pinn ...

sites post-1990. Very few animals still thrive in the Sea of Marmara

The Sea of Marmara, also known as the Sea of Marmora or the Marmara Sea, is a small inland sea entirely within the borders of Turkey. It links the Black Sea and the Aegean Sea via the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits, separating Turkey's E ...

.

: Ongoing Mediterranizations may or may not boost cetacean diversity in the Turkish Straits and hence in the Black and Azov basins.

: Various species of pinniped

Pinnipeds (pronounced ), commonly known as seals, are a widely range (biology), distributed and diverse clade of carnivorous, fin-footed, semiaquatic, mostly marine mammals. They comprise the extant taxon, extant families Odobenidae (whose onl ...

s, sea otter

The sea otter (''Enhydra lutris'') is a marine mammal native to the coasts of the northern and eastern Pacific Ocean, North Pacific Ocean. Adult sea otters typically weigh between , making them the heaviest members of ...

, and beluga whale were introduced into the Black Sea by mankind and later escaped either by accidental or purported causes. Of these, grey seals and beluga whales have been recorded with successful, long-term occurrences.

: Great white shark

The great white shark (''Carcharodon carcharias''), also known as the white shark, white pointer, or simply great white, is a species of large Lamniformes, mackerel shark which can be found in the coastal surface waters of all the major ocea ...

s are known to reach into the Sea of Marmara and Bosporus Strait and basking sharks into the Dardanelles, although it is unclear whether or not these sharks may reach into the Black and Azov basins.

Ecological effects of pollution

Since the 1960s, rapid industrial expansion along the Black Sea coastline and the construction of a major dam on the Danube have significantly increased annual variability in the N:P:Si ratio in the basin. Coastal areas, accordingly, have seen an increase in the frequency of monospecific phytoplankton blooms, with diatom-bloom frequency increasing by a factor of 2.5 and non-diatom bloom frequency increasing by a factor of 6. The non-diatoms, such as the prymnesiophytes (coccolithophore), sp., and the Euglenophyte , can out-compete diatom species because of the limited availability of silicon, a necessary constituent of diatom frustules. As a consequence of these blooms, benthic macrophyte populations were deprived of light, while anoxia caused mass mortality in marine animals. Overfishing during the 1970s further compounded the decline in macrophytes, while the invasive ctenophore ''Mnemiopsis'' reduced the biomass ofcopepod

Copepods (; meaning 'oar-feet') are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat (ecology), habitat. Some species are planktonic (living in the water column), some are benthos, benthic (living on the sedimen ...

s and other zooplankton in the late 1980s. Additionally, an alien species—the warty comb jelly ()—established itself in the basin, exploding from a few individuals to an estimated biomass of one billion metric tons. The change in species composition in Black Sea waters also has consequences for hydrochemistry, as calcium-producing coccolithophores influence salinity and pH, although these ramifications have yet to be fully quantified. In central Black Sea waters, silicon levels also reduced significantly, due to a decrease in the flux of silicon associated with advection across isopycnal surfaces. This phenomenon demonstrates the potential for localized alterations in Black Sea nutrient-input to have basin-wide effects.

Pollution-reduction and regulation efforts led to a partial recovery of the Black Sea ecosystem during the 1990s, and an EU monitoring exercise, 'EROS21', revealed decreased nitrogen and phosphorus values relative to the 1989 peak. Recently, scientists have noted signs of ecological recovery, in part due to the construction of new sewage-treatment plants in Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria in connection with those countries' membership of the European Union. populations have been checked with the arrival of another alien species that feeds on them.

Jellyfish

Jellyfish, also known as sea jellies or simply jellies, are the #Life cycle, medusa-phase of certain gelatinous members of the subphylum Medusozoa, which is a major part of the phylum Cnidaria. Jellyfish are mainly free-swimming marine animal ...

File:black sea fauna actinia 01.jpg, Actinia

File:black sea fauna actinia 02.JPG, Actinia

File:black sea fauna goby 01.jpg, Goby

File:black sea fauna stingray 01.jpg, Stingray

Stingrays are a group of sea Batoidea, rays, a type of cartilaginous fish. They are classified in the suborder Myliobatoidei of the order Myliobatiformes and consist of eight families: Hexatrygonidae (sixgill stingray), Plesiobatidae (deepwate ...

File:Black sea mullus barbatus ponticus 01.jpg, Goat fish

File:Black sea fauna hermit crab 01.jpg, Hermit crab, '' Diogenes pugilator''

File:Black sea fauna blue sponge.jpg, Blue sponge

Sponges or sea sponges are primarily marine invertebrates of the animal phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), a basal clade and a sister taxon of the diploblasts. They are sessile filter feeders that are bound to the seabed, and a ...

File:Squalus acanthias2.jpg, Spiny dogfish

File:Black Sea fauna Seahorse.JPG, Seahorse

A seahorse (also written ''sea-horse'' and ''sea horse'') is any of 46 species of small marine Osteichthyes, bony fish in the genus ''Hippocampus''. The genus name comes from the Ancient Greek (), itself from () meaning "horse" and () meanin ...

File:Kitesurfer and Dolphins Cropped.jpg, Black Sea common dolphins with a kite-surfer off Sochi

Sochi ( rus, Сочи, p=ˈsotɕɪ, a=Ru-Сочи.ogg, from – ''seaside'') is the largest Resort town, resort city in Russia. The city is situated on the Sochi (river), Sochi River, along the Black Sea in the North Caucasus of Souther ...

History

Mediterranean connection during the Holocene

The Black Sea is connected to the

The Black Sea is connected to the World Ocean

The ocean is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of Earth. The ocean is conventionally divided into large bodies of water, which are also referred to as ''oceans'' (the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian, Antarctic/Southern, and ...

by a chain of two shallow straits, the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey th ...

and the Bosporus

The Bosporus or Bosphorus Strait ( ; , colloquially ) is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul, Turkey. The Bosporus connects the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara and forms one of the continental bo ...

. The Dardanelles is deep, and the Bosporus is as shallow as . By comparison, at the height of the last ice age, sea levels were more than lower than they are now.

There is evidence that water levels in the Black Sea were considerably lower at some point during the post-glacial period. Some researchers theorize that the Black Sea had been a landlocked freshwater lake (at least in upper layers) during the last glaciation and for some time after.

In the aftermath of the last glacial period, water levels in the Black Sea and the

There is evidence that water levels in the Black Sea were considerably lower at some point during the post-glacial period. Some researchers theorize that the Black Sea had been a landlocked freshwater lake (at least in upper layers) during the last glaciation and for some time after.

In the aftermath of the last glacial period, water levels in the Black Sea and the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans and Anatolia, and covers an area of some . In the north, the Aegean is connected to the Marmara Sea, which in turn con ...