Enosis Neon Paralimni FC Managers on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Enosis'' (, , "union") is an

''Enosis'' (, , "union") is an

The history of

The history of

At the end of World War I (1914–1918), attention of the Allied Powers (Entente Powers) focused on the partition of the territory of the

At the end of World War I (1914–1918), attention of the Allied Powers (Entente Powers) focused on the partition of the territory of the

Greek troops evacuated Smyrna on 9 September 1922 and a small allied force of British entered the city to prevent looting and violence. The next day, Mustafa Kemal, leading a number of troops, entered the city and was greeted by enthusiastic Turkish crowds. Atrocities by Turkish troops and irregulars against the Greek and

Greek troops evacuated Smyrna on 9 September 1922 and a small allied force of British entered the city to prevent looting and violence. The next day, Mustafa Kemal, leading a number of troops, entered the city and was greeted by enthusiastic Turkish crowds. Atrocities by Turkish troops and irregulars against the Greek and

Since the beginning of the 2010s, an

Since the beginning of the 2010s, an

File:Greek minority of Sicily flag.svg, Greek minority flag of Sicily

Image:Croton AR SNGANS 398ff.jpg, An ancient Greek coin c. 330–300 BC. found in Croton, South Italy with the head of Apollo (left) and ornate tripod (right)

''Enosis'' (, , "union") is an

''Enosis'' (, , "union") is an irredentist

Irredentism () is one state's desire to annex the territory of another state. This desire can be motivated by ethnic reasons because the population of the territory is ethnically similar to or the same as the population of the parent state. Hist ...

ideology held by various Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

communities living outside Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

that calls for them and the regions that they inhabit to be incorporated into the Greek state. The idea is related to the Megali Idea

The Megali Idea () is a nationalist and irredentist concept that expresses the goal of reviving the Byzantine Empire, by establishing a Greek state, which would include the large Greek populations that were still under Ottoman rule after the ...

, a concept of a Greek state that dominated Greek politics following the creation of modern Greece in 1830. The Megali Idea called for the establishment of a larger Greek state including the lands outside Greece that remained under foreign rule following the Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. In 1826, the Greeks were assisted ...

in the 1820s, but which nevertheless still had large Greek populations.

The most widely known example of ''enosis'' is the movement within Greek Cypriots

Greek Cypriots (, ) are the ethnic Greeks, Greek population of Cyprus, forming the island's largest Ethnolinguistic group, ethnolinguistic community. According to the 2023 census, 719,252 respondents recorded their ethnicity as Greek, forming al ...

for a union of Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

with Greece. The idea of ''enosis'' in British-ruled Cyprus became associated with the campaign for Cypriot self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

, especially among the island's Greek Cypriot majority. However, many Turkish Cypriots

Turkish Cypriots or Cypriot Turks ( or ; ) are so called ethnic Turks originating from Cyprus. Turkish Cypriots are mainly Sunni Muslims. Following the Ottoman conquest of the island in 1571, about 30,000 Turkish settlers were given land onc ...

opposed ''enosis'' without '' taksim'', the partitioning of the island between Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots. In 1960, the Republic of Cyprus was born, resulting in neither ''enosis'' nor ''taksim''.

Around then, Cypriot intercommunal violence

Several distinct periods of Cypriot intercommunal violence involving the two main ethnic communities, Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots, marked mid-20th century Cyprus. These included the Cyprus Emergency of 1955–59 during British rule, the ...

occurred in response to the different objectives, and the continuing desire for ''enosis'' resulted in the 1974 Cypriot coup d'état

Major events in 1974 include the aftermath of the 1973 oil crisis and the resignation of President of the United States, United States President Richard Nixon following the Watergate scandal. In the Middle East, the aftermath of the 1973 Yom ...

in an attempt to achieve it. It, however, prompted Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

into launching the Turkish invasion of Cyprus

The Turkish invasion of Cyprus began on 20 July 1974 and progressed in two phases over the following month. Taking place upon a background of Cypriot intercommunal violence, intercommunal violence between Greek Cypriots, Greek and Turkish Cy ...

, which led to partition and the current Cyprus dispute

The Cyprus problem, also known as the Cyprus conflict, Cyprus issue, Cyprus dispute, or Cyprus question, is an ongoing dispute between the Greek Cypriot and the Turkish Cypriot community in the north of the island of Cyprus, where troops of t ...

.

History

The boundaries of theKingdom of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece (, Romanization, romanized: ''Vasíleion tis Elládos'', pronounced ) was the Greece, Greek Nation state, nation-state established in 1832 and was the successor state to the First Hellenic Republic. It was internationally ...

were originally established at the London Conference of 1832

The London Conference of 1832 was an international conference convened to establish a stable government in Greece. Negotiations among the three Great Powers ( Britain, France and Russia) resulted in the establishment of the Kingdom of Greece under ...

following the Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. In 1826, the Greeks were assisted ...

. The Duke of Wellington

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and above sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they ar ...

wanted the new state to be limited to the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese ( ), Peloponnesus ( ; , ) or Morea (; ) is a peninsula and geographic region in Southern Greece, and the southernmost region of the Balkans. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridg ...

because Britain wished to preserve as much of the territorial integrity

Territorial integrity is the principle under international law where sovereign states have a right to defend their borders and all territory in them from another state. It is enshrined in Article 2(4) of the UN Charter and has been recognized as c ...

of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

as possible. The initial Greek state included little more than the Peloponnese, Attica

Attica (, ''Attikḗ'' (Ancient Greek) or , or ), or the Attic Peninsula, is a historical region that encompasses the entire Athens metropolitan area, which consists of the city of Athens, the capital city, capital of Greece and the core cit ...

and the Cyclades

The CYCLADES computer network () was a French research network created in the early 1970s. It was one of the pioneering networks experimenting with the concept of packet switching and, unlike the ARPANET, was explicitly designed to facilitate i ...

. Its population amounted to less than one million, with three times as many ethnic Greeks living outside it, mainly in Ottoman territory. Many of them aspired to be incorporated in the kingdom, and movements among them calling for ''enosis'' (union) with Greece, often achieved popular support. With the decline of the Ottoman Empire, Greece expanded with a number of territorial gains.

The Ionian Islands

The Ionian Islands (Modern Greek: , ; Ancient Greek, Katharevousa: , ) are a archipelago, group of islands in the Ionian Sea, west of mainland Greece. They are traditionally called the Heptanese ("Seven Islands"; , ''Heptanēsa'' or , ''Heptanē ...

had been placed under British protection as a result of the Treaty of Paris in 1815, but once Greek independence had been established after 1830, the islanders began to resent foreign colonial rule and to press for enosis. Britain transferred the islands to Greece in 1864.

Thessaly

Thessaly ( ; ; ancient Aeolic Greek#Thessalian, Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic regions of Greece, geographic and modern administrative regions of Greece, administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient Thessaly, a ...

remained under Ottoman control after the formation of the Kingdom of Greece. Although parts of the territory had participated in the initial uprisings in the Greek War of Independence in 1821, the revolts had been swiftly crushed. During the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, Greece remained neutral as a result of assurances by the great powers

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power ...

that her territorial claims on the Ottoman Empire would be considered after the war. In 1881, Greece and the Ottoman Empire signed the Convention of Constantinople

The Convention of Constantinople is a treaty concerning the use of the Suez Canal in Egypt. It was signed on 29 October 1888 by the United Kingdom, the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, Spain, France, Italy, the Netherlands, the Russian Empire and ...

, which created a new Greco-Turkish border that Incorporated most of Thessaly into Greece.

Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

rebelled against Ottoman rule during the Cretan Revolt of 1866-69 and used the motto "Crete, Enosis, Freedom or Death". The Cretan State

The Cretan State (; ) was an autonomous state governing the island of Crete from 1898 to 1913, under ''de jure'' suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire but with ''de facto'' independence secured by European Great Powers. In 1897, the Cretan Revolt (18 ...

was established after the intervention of the Great Powers, and Cretan union with Greece occurred '' de facto'' in 1908 and ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' (; ; ) describes practices that are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. The phrase is often used in contrast with '' de facto'' ('from fa ...

'' in 1913 by the Treaty of Bucharest.

An unsuccessful Greek uprising in Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

against Ottoman rule had taken place during the Greek War of Independence. There was a failed rebellion in 1854 that aimed to unite Macedonia with Greece. The Treaty of San Stefano

The 1878 Preliminary Treaty of San Stefano (; Peace of San-Stefano, ; Peace treaty of San-Stefano, or ) was a treaty between the Russian and Ottoman empires at the conclusion of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. It was signed at San Ste ...

in 1878 after the Russo-Turkish War awarded nearly all of Macedonia to Bulgaria. That resulted in the 1878 Greek Macedonian rebellion

The 1878 Macedonian rebellion () was a Greeks, Greek rebellion launched in opposition to the Treaty of San Stefano, according to which the bulk of Macedonia (region), Macedonia would be annexed to Bulgaria, and in favour of the union of Macedonia ...

and the reversal of the award at the Treaty of Berlin (1878)

The Treaty of Berlin (formally the Treaty between Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Great Britain and Ireland, Italy, Russia, and the Ottoman Empire for the Settlement of Affairs in the East) was signed on 13 July 1878. In the aftermath of the R ...

, leaving the territory in Ottoman hands. Then followed the protracted Macedonian Struggle

The Macedonian Struggle was a series of social, political, cultural and military conflicts that were mainly fought between Greek and Bulgarian subjects who lived in Ottoman Macedonia between 1893 and 1912. From 1904 to 1908 the conflict was p ...

between Greeks and Bulgarians in the region, the resultant guerrilla war not coming to an end until the revolution of Young Turks

The Young Turks (, also ''Genç Türkler'') formed as a constitutionalist broad opposition-movement in the late Ottoman Empire against the absolutist régime of Sultan Abdul Hamid II (). The most powerful organization of the movement, ...

in July 1908. Bulgarian and Greek rivalries over Macedonia became part of the Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars were two conflicts that took place in the Balkans, Balkan states in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan states of Kingdom of Greece (Glücksburg), Greece, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Montenegro, M ...

of 1912–13, with the 1913 Treaty of Bucharest awarding Greece large parts of Macedonia, including Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

. The Treaty of London (1913)

The Treaty of London (1913) was signed on 30 May following the London Conference of 1912–1913. It dealt with the territorial adjustments arising out of the conclusion of the First Balkan War. The London Conference had ended on 23 January 1913 ...

awarded southern Epirus

Epirus () is a Region#Geographical regions, geographical and historical region, historical region in southeastern Europe, now shared between Greece and Albania. It lies between the Pindus Mountains and the Ionian Sea, stretching from the Bay ...

to Greece, the Epirus region having rebelled against Ottoman rule during the Epirus Revolt of 1854 and the Epirus Revolt of 1878.

In 1821, several parts of Western Thrace

Western Thrace or West Thrace (, '' ytikíThráki'' ), also known as Greek Thrace or Aegean Thrace, is a geographical and historical region of Greece, between the Nestos and Evros rivers in the northeast of the country; East Thrace, which lie ...

rebelled against Ottoman rule and participated in the Greek War of Independence. During the Balkan Wars, Western Thrace was occupied by Bulgarian troops, and in 1913, Bulgaria gained Western Thrace under the terms of the Treaty of Bucharest. After World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Western Thrace was withdrawn from Bulgaria under the terms of the 1919 Treaty of Neuilly

The Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine (; ) was a treaty between the victorious Allies of World War I on the one hand, and Bulgaria, one of the defeated Central Powers in World War I, on the other. The treaty required Bulgaria to cede various territor ...

and temporarily managed by the Allies before being it was given to Greece at the San Remo Conference

The San Remo conference was an international meeting of the post-World War I Allied Supreme Council as an outgrowth of the Paris Peace Conference, held at Castle Devachan in Sanremo, Italy, from 19 to 26 April 1920. The San Remo Resolution ...

in 1920.

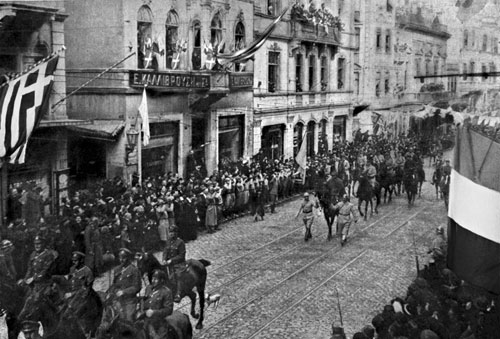

After World War I, Greece began the Occupation of Smyrna

The city of Smyrna (modern-day İzmir) and surrounding areas were under Greek military occupation from 15 May 1919 until 9 September 1922. The Allied Powers authorized the occupation and creation of the Zone of Smyrna () during negotiations re ...

and of surrounding areas of Western Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

in 1919 at the invitation of the victorious Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

, particularly British Prime Minister David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

. The occupation was given official status in the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres () was a 1920 treaty signed between some of the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire, but not ratified. The treaty would have required the cession of large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, ...

, with Greece being awarded most of Eastern Thrace

East Thrace or Eastern Thrace, also known as Turkish Thrace or European Turkey, is the part of Turkey that is geographically in Southeast Europe. Turkish Thrace accounts for 3.03% of Turkey's land area and 15% of its population. The largest c ...

and a mandate to govern Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; , or ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, Turkey. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna ...

and its hinterland. Smyrna was declared a protectorate in 1922, but the attempted ''enosis'' failed since the new Turkish Republic Turkish Republic may refer to:

* Turkey, archaically the "Turkish Republic"

* Northern Cyprus

Northern Cyprus, officially the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), is a ''de facto'' state that comprises the northeastern portion of the ...

prevailed in the resulting Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922, when most Anatolian Christians who had not already fled during the war were forced to relocate to Greece in the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey

The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey stemmed from the "Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations" signed at Lausanne, Switzerland, on 30 January 1923, by the governments of Greece and Turkey. It involv ...

.

Most of the Dodecanese

The Dodecanese (, ; , ''Dodekánisa'' , ) are a group of 15 larger and 150 smaller Greek islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Anatolia, of which 26 are inhabited. This island group generally define ...

Islands were slated to become part of the new Greek state in the London Protocol of 1828, but when Greek independence was recognised in the London Protocol of 1830, the islands were left outside the new Kingdom of Greece. They were occupied by Italy in 1912 and held until World War II, when they became a British military protectorate. The islands were formally united with Greece by the 1947 Treaty of Peace with Italy, despite objections from Turkey, which also desired them.

The Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus

The Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus () was a short-lived, self-governing entity founded in the aftermath of the Balkan Wars on 28 February 1914, by the local Greek population in southern Albania ( Northern Epirotes).

The area, known as ...

was proclaimed in 1914 by ethnic Greeks in Northern Epirus

Northern Epirus (, ; ) is a term used for specific parts of southern Albania which were first claimed by the Kingdom of Greece in the Balkan Wars and later were associated with the Greek minority in Albania and Greece-Albania diplomatic relation ...

, the area having been incorporated into Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

after the Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars were two conflicts that took place in the Balkans, Balkan states in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan states of Kingdom of Greece (Glücksburg), Greece, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Montenegro, M ...

. Greece held the area between 1914 and 1916 and unsuccessfully tried to annex it in March 1916, but in 1917 Greek forces were driven from the area by Italy, who took over most of Albania. The Paris Peace Conference of 1919

Paris () is the capital and largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the fourth-most populous city in the European Union and the 30th most densely popul ...

awarded the area to Greece, but Greece's defeat in the Greco-Turkish War made the area revert to Albanian control. Italy's invasion of Greece from the territory of Albania in 1940 and the successful Greek counterattack let the Greek army briefly hold Northern Epirus for a six-month period until the German invasion of Greece

The German invasion of Greece or Operation Marita (), were the attacks on Kingdom of Greece, Greece by Kingdom of Italy, Italy and Nazi Germany, Germany during World War II. The Italian invasion in October 1940, which is usually known as the Gr ...

in 1941. Tensions between Greece and Albania remained high during the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, but relations began to improve in the 1980s with Greece's abandonment of any territorial claims over Northern Epirus and the lifting of the official state of war between both countries.

In modern times, apart from Cyprus, the call for ''enosis'' is most often heard among part of the Greek community living in southern Albania.

Cyprus

Inception

In 1828, the first President ofGreece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

, Ioannis Kapodistrias

Count Ioannis Antonios Kapodistrias (; February 1776 –27 September 1831), sometimes anglicized as John Capodistrias, was a Greek statesman who was one of the most distinguished politicians and diplomats of 19th-century Europe.

Kapodistrias's ...

, called for the union of Cyprus with Greece, and numerous minor uprisings took place. Cyprus was at that time part of the Ottoman Empire. At the 1878 Congress of Berlin

At the Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878), the major European powers revised the territorial and political terms imposed by the Russian Empire on the Ottoman Empire by the Treaty of San Stefano (March 1878), which had ended the Rus ...

the administration of Cyprus was transferred to Britain, and upon Garnet Wolseley

Field Marshal Garnet Joseph Wolseley, 1st Viscount Wolseley (4 June 183325 March 1913) was an Anglo-Irish officer in the British Army. He became one of the most influential British generals after a series of victories in Canada, West Africa and E ...

's arrival as the first high-commissioner in July the Archbishop of Kition

Kition (Ancient Greek: , ; Latin: ; Egyptian: ; Phoenician: , , or , ;) was an ancient Phoenician and Greek city-kingdom on the southern coast of Cyprus (in present-day Larnaca), one of the Ten city-kingdoms of Cyprus.

Name

The name of the ...

requested that Britain transfer the administration of Cyprus to Greece. Britain annexed Cyprus in 1914.

The death of Limassol–Paphos

Paphos, also spelled as Pafos, is a coastal city in southwest Cyprus and the capital of Paphos District. In classical antiquity, two locations were called Paphos: #Old Paphos, Old Paphos, today known as Kouklia, and #New Paphos, New Paphos. It i ...

MP Christodoulos Sozos

Christodoulos Sozos (Greek language, Greek: Χριστόδουλος Σώζος; 10 March 1872 in Limassol 6 December 1912 in Manoliasa, Epirus) was a Greek Cypriot politician and lawyer. He served as a member of the Cypriot Legislative Council ( ...

during the course of the Battle of Bizani

The Battle of Bizani (, ''Máchi tou Bizaníou''; ) took place in Epirus on . The battle was fought between Greek and Ottoman forces during the last stages of the First Balkan War, and revolved around the forts of Bizani, which covered the app ...

during the First Balkan War

The First Balkan War lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and involved actions of the Balkan League (the Kingdoms of Kingdom of Bulgaria, Bulgaria, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Greece, Greece and Kingdom of Montenegro, Montenegro) agai ...

, left a lasting mark on the Enosis movement and was one of its most important events before the 1931 Cyprus revolt. Greek schools and courts suspended their activities, and a court in Nicosia

Nicosia, also known as Lefkosia and Lefkoşa, is the capital and largest city of Cyprus. It is the southeasternmost of all EU member states' capital cities.

Nicosia has been continuously inhabited for over 5,500 years and has been the capi ...

also raised a flag in honour of Sozos, thus breaking the law since Britain had maintained a neutral stance in the conflict. Mnemosyna were held in dozens of villages across Cyprus, as well as in Cypriot communities in Athens, Egypt and Sudan. Greek Cypriot newspapers were swept with nationalist fervor comparing Sozos with Pavlos Melas

Pavlos Melas (; 29 March 1870 – 13 October 1904) was a Greek revolutionary and artillery officer of the Hellenic Army. He participated in the Greco-Turkish War of 1897 and was amongst the first Greek officers to join the Macedonian Struggle. ...

. A photo of Sozos was placed in the Hellenic Parliament

The Parliament of the Hellenes (), commonly known as the Hellenic Parliament (), is the Unicameralism, unicameral legislature of Greece, located in the Old Royal Palace, overlooking Syntagma Square in Athens. The parliament is the supreme demo ...

.

Britain offered to cede the island to Greece in 1915 in return for Greece joining the allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, but the offer was refused. Turkey relinquished all claims to Cyprus in 1923 with the Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (, ) is a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–1923 and signed in the Palais de Rumine in Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially resolved the conflict that had initially ...

, and the island became a British Crown colony

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony governed by Kingdom of England, England, and then Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain or the United Kingdom within the English overseas possessions, English and later British Empire. There was usua ...

in 1925. In 1929, a Greek Cypriot delegation was sent to London to request ''enosis'' but received a negative response. After anti-British riots in 1931, the desire for self-government within the British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, often referred to as the British Commonwealth or simply the Commonwealth, is an international association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire

The B ...

developed, but the movement for ''enosis'' became dominant.

Greek Cypriots made up around 80% of the island's population between 1882 and 1960, and the enosis movement resulted from the nationalist awareness that was developing among them, coupled with the growth of the anticolonial movement throughout the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

after World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. In the minds of Greek Cypriots, the enosis movement was the only natural outcome of the liberation of Cyprus from Ottoman rule and later British rule. A string of British proposals for local autonomy under continued British suzerainty

A suzerain (, from Old French "above" + "supreme, chief") is a person, state (polity)">state or polity who has supremacy and dominant influence over the foreign policy">polity.html" ;"title="state (polity)">state or polity">state (polity)">st ...

were roundly rejected.

1940s and 1950s

In the 1950s, the influence of the Greek OrthodoxChurch of Cyprus

The Church of Cyprus () is one of the autocephalous Greek Orthodox churches that together with other Eastern Orthodox churches form the communion of the Eastern Orthodox Church. It is one of the oldest Eastern Orthodox autocephalous churches; ...

over the education system resulted in the ideas of Greek nationalism

Greek nationalism, otherwise referred to as Hellenic nationalism, refers to the nationalism of Greeks and Greek culture.. As an ideology, Greek nationalism originated and evolved in classical Greece. In modern times, Greek nationalism became a m ...

and ''enosis'' being promoted in Greek Cypriot schools. School textbooks portrayed Turks as the enemies of Greeks, and students took an oath of allegiance to the Greek flag. The British authorities attempted to counter that by publishing an intercommunal periodical for students and by suspending the Cyprus Scouts Association for its Greek nationalist tendencies.

In December 1949, the Cypriot Orthodox Church asked the British colonial government to put the enosis question to a referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

on the basis of the right of the Cypriots' for self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

. Even though the British had been an ally of Greece during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

and had recently supported the Greek government during the Greek Civil War

The Greek Civil War () took place from 1946 to 1949. The conflict, which erupted shortly after the end of World War II, consisted of a Communism, Communist-led uprising against the established government of the Kingdom of Greece. The rebels decl ...

, the British colonial government refused.

In 1950, Archbishop Spyridon of Athens

Spyridon (secular name: Σπυρίδων Βλάχος ''Spyridon Vlachos'') was Archbishop of Athens and All Greece from 1949 until 1956. He was born in Chili (Χήλη), in present-day northern Turkey. His parents originated from the village of ...

led the call for Cypriot ''enosis'' in Greece. The Church was a strong supporter of ''enosis'' and organised a plebiscite, the Cypriot enosis referendum, which was held on 15 and 22 January 1950; only Greek Cypriots could vote. Open books were placed in churches for those over 18 to sign and to indicate whether they supported or opposed ''enosis''. The majority in support of ''enosis'' was 95.7%. Later, there were accusations that the local Greek Orthodox church had told its congregation that not to vote for ''enosis'' would have meant excommunication from the church.

After the referendum, a Greek Cypriot deputation visited Greece, Britain and the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

to make its case, and Turkish Cypriots and student and youth organisations in Turkey protested the plebiscite. In the event, neither Britain nor the UN was persuaded to support ''enosis''. In 1951, a report was produced by the British government's Smaller Territories Enquiry into the future of the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

's smaller territories, including Cyprus. It concluded that Cyprus should never be independent from Britain. That view was strengthened by Britain's withdrawal of its Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

base in 1954 and the transfer of its Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

Headquarters to Cyprus. In 1954, Greece made its first formal request to the UN for the implementation of "the principle of equal rights and of self-determination of the peoples", in the case of the Cypriot population. Until 1958, four other requests to the United Nations were made unsuccessfully by the Greek government.

In 1955, the resistance organisation EOKA

The Ethniki Organosis Kyprion Agoniston (EOKA ; ) was a Greek Cypriot nationalist guerrilla organization that fought a campaign for the end of Cyprus#Cyprus under the British Empire, British rule in Cyprus, and for enosis, eventual union with K ...

started a campaign against British rule to bring about ''enosis'' with Greece. The campaign lasted until 1959, when many argued that ''enosis'' was politically unfeasible because of the strong minority of Turkish Cypriots and their increasing assertiveness. Instead, the creation of an independent state with elaborate powersharing arrangements among both communities was agreed upon in 1960, and the fragile Republic of Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the third lar ...

was born.

After independence

The idea of union with Greece was not immediately abandoned, however. During the campaign for the 1968 presidential elections, Cypriot PresidentMakarios III

Makarios III (born Michael Christodoulou Mouskos; 13 August 1913 – 3 August 1977) was a Greek Cypriots, Greek Cypriot prelate and politician who served as Archbishop of the Church of Cyprus from 1950 to 1977 and as the first president o ...

said that ''enosis'' was "desirable" but that independence was "possible".

In the early 1970s, the idea of ''enosis'' remained attractive to many Greek Cypriots, and Greek Cypriot students condemned Makarios's support for an independent unitary state. In 1971 the pro-''enosis'' paramilitary group EOKA B

EOKA-B or Ethniki Organosis Kyprion Agoniston B (EOKA B ; ) was a Greek Cypriot paramilitary organisation formed in 1971 by General Georgios Grivas. It followed an ultra right-wing nationalistic ideology and had the ultimate goal of achievin ...

was formed, and Makarios declared his opposition to the use of violence to achieve ''enosis''. EOKA B began a series of attacks against the Makarios government, and in 1974, the Cypriot National Guard

The National Guard of Cyprus (), also known as the Greek Cypriot National Guard or simply the National Guard, is the military force of the Republic of Cyprus. It consists of air, land, sea and special forces elements, and is highly integrated wit ...

organised a military coup against Makarios that was supported by the Greek government under the control of the Greek military junta of 1967–1974

The Greek junta or Regime of the Colonels was a right-wing military junta that ruled Greece from 1967 to 1974. On 21 April 1967, a group of colonels with CIA backing overthrew the caretaker government a month before scheduled elections wh ...

. Rauf Denktaş

Rauf Raif Denktaş (27 January 1924 – 13 January 2012) was a Turkish Cypriot politician, barrister and jurist who served as the founding president of Northern Cyprus. He occupied this position as the president of the Turkish Republic of Nort ...

, the Turkish Cypriot leader, called for military intervention by the United Kingdom and Turkey to prevent ''enosis''. Turkey acted unilaterally, and the Turkish invasion of Cyprus

The Turkish invasion of Cyprus began on 20 July 1974 and progressed in two phases over the following month. Taking place upon a background of Cypriot intercommunal violence, intercommunal violence between Greek Cypriots, Greek and Turkish Cy ...

began. Turkey has since occupied Northern Cyprus

Northern Cyprus, officially the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), is a ''de facto'' state that comprises the northeastern portion of the Geography of Cyprus, island of Cyprus. It is List of states with limited recognition, recognis ...

.

The events of 1974 caused the geographic partition of Cyprus and massive population transfers. The subsequent events seriously undermined the ''enosis'' movement. The departure of Turkish Cypriots from the areas that remained under effective control of Cyprus resulted in a homogeneous Greek Cypriot society in the southern two thirds of the island. The remaining third of the island is majority Turkish Cypriot, and increasing numbers of Turkish nationals have been migrating there from Turkey.

In 2017 the Cypriot Parliament passed a law to allow for the celebration of the 1950 Cypriot enosis referendum in Greek Cypriot government schools.

North Epirus

The history of

The history of Northern Epirus

Northern Epirus (, ; ) is a term used for specific parts of southern Albania which were first claimed by the Kingdom of Greece in the Balkan Wars and later were associated with the Greek minority in Albania and Greece-Albania diplomatic relation ...

in the period 1913–1921 was marked by the desire of the local Greek element for union with the Kingdom of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece (, Romanization, romanized: ''Vasíleion tis Elládos'', pronounced ) was the Greece, Greek Nation state, nation-state established in 1832 and was the successor state to the First Hellenic Republic. It was internationally ...

, as well as the redemptive desire of Greek politics to annex this region, which was eventually awarded to the Albanian Principality.

During the First Balkan War, Northern Epirus, which hosted a significant minority of Orthodox speakers who spoke either Greek or Albanian, was, at the same time as South Epirus, under the control of the Greek army, which had previously repelled Ottoman forces. Greece wanted to annex these territories. However, Italy and Austria-Hungary opposed this, while the Treaty of Florence of 1913 granted Northern Epirus to Albania's newly formed Principality, the majority of whose inhabitants were Muslims. Thus, the Greek army withdrew from the area, but the Christians of Epirus, denying the international situation, decided, with the secret support of the Greek state, to create an autonomous regime, based in Argyrokastro (Albanian: Gjirokastër

Gjirokastër (, sq-definite, Gjirokastra) is a List of cities and towns in Albania, city in Southern Albania, southern Albania and the seat of Gjirokastër County and Gjirokastër Municipality. It is located in a valley between the Gjerë moun ...

).

Given Albania's political instability, the autonomy of Northern Epirus was finally ratified by the Great Powers with the signing of the Protocol of Corfu on May 17, 1914. The agreement did recognize the special status of the Epirotes and their right to self-determination. under the legal authority of Albania. However, the agreement never materialized, as the Albanian government collapsed in August, and Prince William of Wied

Wilhelm, Prince of Albania (Wilhelm Friedrich Heinrich; , 26 March 1876 – 18 April 1945) was sovereign of the Principality of Albania from 7 March to 3 September 1914. His reign officially came to an end on 31 January 1925, when the country w ...

, who was appointed leader of the country in February, returned to Germany in September.

Shortly after the outbreak of World War I, in October 1914, the Kingdom of Greece recaptured the region. However, the ambiguous attitude of the Central Powers on Greek issues during the Great War, led France and Italy to the joint occupation of Epirus in September 1916. At the end of World War I, however, the Agreement of Tittoni with Venizelos foresaw the annexation of the region to Greece. Eventually, Greece's military involvement with Mustafa Kemal's Turkey worked in the interest of Albania, which permanently annexed the region on 9 November 1920.

Smyrna

At the end of World War I (1914–1918), attention of the Allied Powers (Entente Powers) focused on the partition of the territory of the

At the end of World War I (1914–1918), attention of the Allied Powers (Entente Powers) focused on the partition of the territory of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. As part of the Treaty of London (1915)

The Treaty of London (; ) or the Pact of London (, ) was a secret agreement concluded on 26 April 1915 by the United Kingdom, France, and Russia on the one part, and Italy on the other, in order to entice the last to enter the Great War on ...

, by which Italy left the Triple Alliance Triple Alliance may refer to:

* Aztec Triple Alliance (1428–1521), Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan and in central Mexico

* Triple Alliance (1596), England, France, and the Dutch Republic to counter Spain

* Triple Alliance (1668), England, the ...

(with Germany and Austria-Hungary) and joined France, Great Britain and Russia in the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was built upon th ...

, Italy was promised the Dodecanese

The Dodecanese (, ; , ''Dodekánisa'' , ) are a group of 15 larger and 150 smaller Greek islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Anatolia, of which 26 are inhabited. This island group generally define ...

and, if the partition of the Ottoman Empire were to occur, land in Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

including Antalya

Antalya is the fifth-most populous city in Turkey and the capital of Antalya Province. Recognized as the "capital of tourism" in Turkey and a pivotal part of the Turkish Riviera, Antalya sits on Anatolia's southwest coast, flanked by the Tau ...

and surrounding provinces presumably including Smyrna. But in later 1915, as an inducement to enter the war, British Foreign Secretary Edward Grey in private discussion with Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos (, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Cretan State, Cretan Greeks, Greek statesman and prominent leader of the Greek national liberation movement. As the leader of the Liberal Party (Greece), Liberal Party, Venizelos ser ...

, the Greek Prime Minister at the time, promised large parts of the Anatolian coast to Greece, including Smyrna. Venizelos resigned from his position shortly after this communication, but when he had formally returned to power in June 1917, Greece entered the war on the side of the Entente.

On 30 October 1918, the Armistice of Mudros

The Armistice of Mudros () ended hostilities in the Middle Eastern theatre between Ottoman Turkey and the Allies of World War I. It was signed on 30 October 1918 by the Ottoman Minister of Marine Affairs Rauf Bey and British Admiral Somerset ...

was signed between the Entente powers and the Ottoman Empire ending the Ottoman front of World War I. Great Britain, Greece, Italy, France, and the United States began discussing what the treaty provisions regarding the partition of Ottoman territory would be, negotiations which resulted in the Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres () was a 1920 treaty signed between some of the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire, but not ratified. The treaty would have required the cession of large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, ...

. These negotiations began in February 1919 and each country had distinct negotiating preferences about Smyrna. The French, who had large investments in the region, took a position for territorial integrity of a Turkish state that would include the zone of Smyrna. The British were at loggerheads over the issue with the War Office

The War Office has referred to several British government organisations throughout history, all relating to the army. It was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, at ...

and India Office

The India Office was a British government department in London established in 1858 to oversee the administration of the Provinces of India, through the British viceroy and other officials. The administered territories comprised most of the mo ...

promoting the territorial integrity idea and Prime Minister David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

and the Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* United ...

, headed by Lord Curzon

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), known as Lord Curzon (), was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician, explorer and writer who served as Viceroy of India ...

, opposed to this suggestion and wanting Smyrna to be under separate administration. The Italian position was that Smyrna was rightfully their possession and so the diplomats would refuse to make any comments when Greek control over the area was discussed. The Greek government, pursuing Venizelos' support for the ''Megali Idea

The Megali Idea () is a nationalist and irredentist concept that expresses the goal of reviving the Byzantine Empire, by establishing a Greek state, which would include the large Greek populations that were still under Ottoman rule after the ...

'' (to bring areas with a majority Greek population or with historical or religious ties to Greece under the control of the Greek state) and supported by Lloyd George, began a large propaganda effort to promote their claim to Smyrna including establishing a mission under the foreign minister in the city. Moreover, the Greek claim over the Smyrna area (which appeared to have a clear Greek majority, although exact percentages varied depending on the sources) were supported by Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

's Fourteen Points

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms to the United States Congress ...

which emphasized the right to autonomous development for minorities in Anatolia. In negotiations, despite French and Italian objections, by the middle of February 1919 Lloyd George shifted the discussion to how Greek administration would work and not whether Greek administration would happen. To further this aim, he brought in a set of experts, including Arnold J. Toynbee

Arnold Joseph Toynbee (; 14 April 1889 – 22 October 1975) was an English historian, a philosopher of history, an author of numerous books and a research professor of international history at the London School of Economics and King's Coll ...

, to discuss how the zone of Smyrna would operate and what its impacts would be on the population. Following this discussion, in late February 1919, Venezilos appointed Aristeidis Stergiadis, a close political ally, the High Commissioner of Smyrna (appointed over political riser Themistoklis Sofoulis

Themistoklis Sofoulis or Sophoulis (; 24 November 1860 – 24 June 1949) was a prominent centrist and liberal Greek politician from Samos Island, who served three times as Prime Minister of Greece, with the Liberal Party, which he led for many ...

).

In April 1919, the Italians landed and took over Antalya and began showing signs of moving troops towards Smyrna. During the negotiations at about the same time, the Italian delegation walked out when it became clear that Fiume (Rijeka) would not be given to them in the peace outcome. Lloyd George saw an opportunity to break the impasse over Smyrna with the absence of the Italian delegation and, according to Jensen, he "concocted a report that an armed uprising of Turkish guerrillas in the Smyrna area was seriously endangering the Greek and other Christian minorities." Both to protect local Christians and also to limit increasing Italian action in Anatolia, French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who was Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A physician turned journalist, he played a central role in the poli ...

and U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

supported a Greek military occupation of Smyrna. Although Smyrna would be occupied by Greek troops, authorized by the Allies, the Allies did not agree that Greece would take sovereignty over the territory until further negotiations settled this issue. The Italian delegation acquiesced to this outcome and the Greek occupation was authorized.

Turkish capture of Smyrna

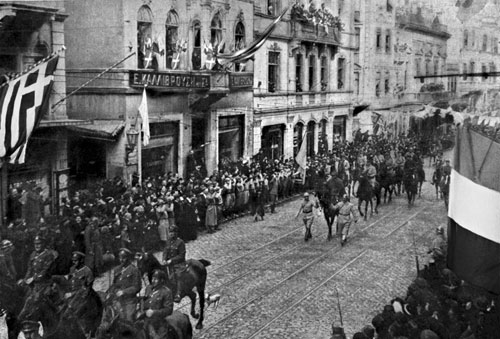

Greek troops evacuated Smyrna on 9 September 1922 and a small allied force of British entered the city to prevent looting and violence. The next day, Mustafa Kemal, leading a number of troops, entered the city and was greeted by enthusiastic Turkish crowds. Atrocities by Turkish troops and irregulars against the Greek and

Greek troops evacuated Smyrna on 9 September 1922 and a small allied force of British entered the city to prevent looting and violence. The next day, Mustafa Kemal, leading a number of troops, entered the city and was greeted by enthusiastic Turkish crowds. Atrocities by Turkish troops and irregulars against the Greek and Armenian

Armenian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Armenia, a country in the South Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Armenians, the national people of Armenia, or people of Armenian descent

** Armenian diaspora, Armenian communities around the ...

population occurred immediately after the takeover. Most notably, Chrysostomos, the Orthodox bishop, was lynched by a mob of Turkish citizens. A few days afterward, a fire destroyed the Greek and Armenian quarters of the city, while the Turkish and Jewish quarters remained undamaged. Culpability for the fire is blamed on all ethnic groups and clear blame remains elusive. On the Turkish side—but not among Greeks—the events are known as the " Liberation of İzmir".

The evacuation of Smyrna by Greek troops ended most of the large scale fighting in the Greco-Turkish war which was formally ended with an Armistice and a final treaty on 24 July 1923 with the Treaty of Lausanne. Much of the Greek population was included in the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey

The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey stemmed from the "Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations" signed at Lausanne, Switzerland, on 30 January 1923, by the governments of Greece and Turkey. It involv ...

resulting in migration to Greece and elsewhere.

Ionian Islands

Under the Treaty between Great Britain and ustria, Prussia andRussia, respecting the Ionian Islands ( signed in Paris on 5 November 1815), as one of the treaties signed during the Peace of Paris (1815), Britain obtained a protectorate over the Ionian Islands, and under Article VIII of the treaty theAustrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

was granted the same trading privileges with the Islands as Britain. As agreed in Article IV of the treaty a "New Constitutional Charter for the State" was drawn up and was formalised with the ratification of the " Maitland constitution" on 26 August 1817, which created a federation of the seven islands, with Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas Maitland

Lieutenant-general (United Kingdom), Lieutenant General Sir Thomas Maitland (10 March 1760 – 17 January 1824) was a British Army officer, politician and colonial administrator. He also served as a Member of Parliament for Haddington (UK Parli ...

its first "Lord High Commissioner of the Ionian Islands

The Lord High Commissioner of the Ionian Islands was the local representative of the British Crown in the United States of the Ionian Islands between 1816 and 1864, succeeding the earlier office of the Civil Commissioner of the Ionian Islands. At ...

".

A few years later Greek nationalist groups started to form. Although their energy in the early years was directed to supporting their fellow Greek revolutionaries in the revolution against the Ottoman Empire, they switched their focus to ''enosis'' with Greece following their independence. The Party of Radicals (Greek: Κόμμα των Ριζοσπαστών) founded in 1848 as a pro-enosis political party. In September 1848 there were skirmishes with the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

garrison in Argostoli

Argostoli (, Katharevousa: ) is a town and a municipality on the island of Kefalonia, Ionian Islands (region), Ionian Islands, Greece. Since the 2019 local government reform it is one of the three municipalities on the island. It has been the capi ...

and Lixouri

Lixouri () is a town and a municipality in the island of Kefalonia, the largest of the Ionian Islands of western Greece. It is the main town on the peninsula of Paliki, and the second largest town in Kefalonia after Argostoli and before Sami. It is ...

on Kefalonia

Kefalonia or Cephalonia (), formerly also known as Kefallinia or Kephallonia (), is the largest of the Ionian Islands in western Greece and the 6th-largest island in Greece after Crete, Euboea, Lesbos, Rhodes and Chios. It is also a separate regio ...

, which led to a certain level relaxation in the enforcement of the protectorate's laws, and freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic Media (communication), media, especially publication, published materials, shoul ...

as well. The island's populace did not hide their growing demands for enosis, and newspapers on the islands frequently published articles criticising British policies in the protectorate. On 15 August in 1849, another rebellion broke out, which was quashed by Henry George Ward

Sir Henry George Ward Order of St Michael and St George, GCMG (27 February 17972 August 1860) was an English diplomat, politician, and colonial administrator.

Early life

He was the son of Robert Plumer Ward, Robert Ward (who in 1828 changed hi ...

, who proceeded to temporarily impose martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

.

On 26 November 1850, the Radical MP John Detoratos Typaldos proposed in the Ionian parliament the resolution for the enosis of the Ionian Islands with Greece which was signed by Gerasimos Livadas, Nadalis Domeneginis, George Typaldos, Frangiskos Domeneginis, Ilias Zervos Iakovatos, Iosif Momferatos, Telemachus Paizis, Ioannis Typaldos, Aggelos Sigouros-Dessyllas, Christodoulos Tofanis. In 1862, the party split into two factions, the "United Radical Party" and the "Real Radical Party". During the period of British rule, William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he ...

visited the islands and recommended their reunion with Greece, to the chagrin of the British government.

On 29 March 1864, representatives of Great Britain, Greece, France, and Russia signed the Treaty of London, pledging the transfer of sovereignty to Greece upon ratification; this was meant to bolster the reign of the newly installed King George I of Greece

George I ( Greek: Γεώργιος Α΄, romanized: ''Geórgios I''; 24 December 1845 – 18 March 1913) was King of Greece from 30 March 1863 until his assassination on 18 March 1913.

Originally a Danish prince, George was born in Copenhage ...

. Thus, on 28 May, by proclamation of the Lord High Commissioner, the Ionian Islands were united with Greece.

Southern Italy

Since the beginning of the 2010s, an

Since the beginning of the 2010s, an online social movement

In computer technology and telecommunications, online indicates a state of connectivity, and offline indicates a disconnected state. In modern terminology, this usually refers to an Internet connection, but (especially when expressed as "on lin ...

has been launched to awaken the Greek consciousness of the inhabitants of Southern Italy

Southern Italy (, , or , ; ; ), also known as () or (; ; ; ), is a macroregion of Italy consisting of its southern Regions of Italy, regions.

The term "" today mostly refers to the regions that are associated with the people, lands or cultu ...

and also to express an opinion that highlights the desire of a part of the inhabitants of the south for secession from the state of Italy, its union with the Hellenism of the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

(and re-establishment of Magna Graecia

Magna Graecia refers to the Greek-speaking areas of southern Italy, encompassing the modern Regions of Italy, Italian regions of Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania, and Sicily. These regions were Greek colonisation, extensively settled by G ...

and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies () was a kingdom in Southern Italy from 1816 to 1861 under the control of the House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies, a cadet branch of the House of Bourbon, Bourbons. The kingdom was the largest sovereign state by popula ...

).

Through pages mainly on Facebook, historical issues are highlighted that have more to do with the Greek presence in Italy that begins with the migration of the Greek diaspora in the 8th century BC., the linguistic minority, known as Griko in Calabria

Calabria is a Regions of Italy, region in Southern Italy. It is a peninsula bordered by the region Basilicata to the north, the Ionian Sea to the east, the Strait of Messina to the southwest, which separates it from Sicily, and the Tyrrhenian S ...

, Apulia

Apulia ( ), also known by its Italian language, Italian name Puglia (), is a Regions of Italy, region of Italy, located in the Southern Italy, southern peninsular section of the country, bordering the Adriatic Sea to the east, the Strait of Ot ...

and Messina

Messina ( , ; ; ; ) is a harbour city and the capital city, capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of 216,918 inhabitants ...

, the modern day Greeks of Italy and in general the inhabitants of the south who call themselves Great-Greeks (MagnoGreci).

The largest Facebook page highlighting the specific issues called "Stato Magna Grecia - Due Sicilie", has over 270,000 followers, mainly Italians but also several Greeks and Griko, expressing the need for the secession of Sicily and the whole of Southern Italy, the so-called Mezzogiorno and its ''enosis'' with Greece and Cyprus. This page and other pages based in Italy highlight the achievements of ancient Magna Graecia and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies as well as the close relations that the people of Southern Italy have with Greece.

According to the administrators of these Facebook pages, the unification of Italy, in which Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as (). In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as () or (). 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, revolutionary and republican. H ...

's campaign in Sicily in 1860 played a decisive role, for many inhabitants of southern Italy more represents the beginning of a form of colonialism while for them the union was made on the terms of the Italian north, which essentially imposed its own powers, its language, its culture, the Italian South was more economically developed than the North, but this trend was reversed after unification. Thus emerge views interwoven with neo-bourbonism (Italian: Neoborbonismo) which is a form of nostalgia for the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, a term coined in 1960 and born with the creation of the separatist movements in Italy while experiencing a significant increase in popularity around 2011 during the celebrations of the 150th anniversary of the Unification of Italy, the same decade of prominence of the movement of the re-Hellenization and independence of Greater Greece. The Neo-Bourbonist movement is supported by small political movements, amateur websites, leading the Italian newspaper ''Corriere del Mezzogiorno'' to report that "Neo-Bourbon revanchism is in vogue in recent years..."

On a political level, the administrators of the said Magna Graecia - Two Sicilies pages urged followers during the 2023 national elections in Greece to vote for political parties supporting the demand for independence of South

Italy and union with Greece.

According to Italian media, the Italian political party Insorgenza Magnogreca led by Luigi Lista and based in Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

presents itself as a movement that represents, among others, the Greek identity of Southern Italy. The association "Comitato provincia della Magna Graecia" chaired by Domenico Mazza was created with the aim of promoting the union of all the regions of South Italy into a new separate great region of Italy and developing a stronger connection with Greece.

In Greece, the far-right party "Hellenic world empire" (Ελληνική Κοσμοκρατορία), which officially seeks the secession of the Italian south, participated in the 2019 European elections in a joint descent with the Popular Orthodox Rally

The Popular Orthodox Rally or People's Orthodox Alarm (Greek: Λαϊκός Ορθόδοξος Συναγερμός, ''Laikós Orthódoxos Synagermós''), often abbreviated to LAOS (ΛΑ.Ο.Σ.) as a reference to the Greek word for ''people'', is ...

party and the Patriotic Radical Union party of the independent MEP, elected with the Golden Dawn of Eleftherios Synadinos gathered the 1.23%.

According to Greek media, the inhabitants of South Italy already have their own flag with the emblem of the ancient Greek triskelion

A triskelion or triskeles is an ancient motif consisting either of a triple spiral exhibiting rotational symmetry or of other patterns in triplicate that emanate from a common center. The spiral design can be based on interlocking Archimedean s ...

symbolizing the oracle of Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), was an ancient sacred precinct and the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient Classical antiquity, classical world. The A ...

by Pythia

Pythia (; ) was the title of the high priestess of the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo at Delphi. She specifically served as its oracle and was known as the Oracle of Delphi. Her title was also historically glossed in English as th ...

that determined where the Greek colonies should be established in Italy, as well as an informal national anthem, created by the Greek soprano Sonia Theodoridou.

See also

*Anti-Turkism

Anti-Turkish sentiment, also known as Anti-Turkism (), or Turkophobia () is hostility, intolerance, or xenophobia against Turkish people, Culture of Turkey, Turkish culture, and the Turkish language.

The term refers to not only against Turkish ...

* Greek nationalism

Greek nationalism, otherwise referred to as Hellenic nationalism, refers to the nationalism of Greeks and Greek culture.. As an ideology, Greek nationalism originated and evolved in classical Greece. In modern times, Greek nationalism became a m ...

* Miatsum

* Taksim

Notes

References

Sources

* * * {{Authority control Cyprus dispute EOKA Greek Cypriot nationalism Greek nationalism Megali Idea