Edo shogunate on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Tokugawa shogunate, also known as the was the

A long period of peace occurred between the

The late Tokugawa shogunate ( ''Bakumatsu'') was the period between 1853 and 1867, during which Japan ended its isolationist foreign policy called ''

The late Tokugawa shogunate ( ''Bakumatsu'') was the period between 1853 and 1867, during which Japan ended its isolationist foreign policy called ''

The shogunate had the power to discard, annex, and transform domains, although they were rarely and carefully exercised after the early years of the shogunate, to prevent ''daimyōs'' from banding together. The ''sankin-kōtai'' system of alternative residence required each ''daimyō'' to reside in alternate years between the ''han'' and the court in Edo. During their absences from Edo, it was also required that they leave their family as hostages until their return. The hostages and the huge expenditure ''sankin-kōtai'' imposed on each ''han'' helped to ensure loyalty to the ''shōgun''. By the 1690s, the vast majority of daimyos would be born in Edo, and most would consider it their homes. Some daimyos had little interest in their domains and needed to be begged to return "home".

In return for the centralization, peace among the daimyos was maintained; unlike in the

The shogunate had the power to discard, annex, and transform domains, although they were rarely and carefully exercised after the early years of the shogunate, to prevent ''daimyōs'' from banding together. The ''sankin-kōtai'' system of alternative residence required each ''daimyō'' to reside in alternate years between the ''han'' and the court in Edo. During their absences from Edo, it was also required that they leave their family as hostages until their return. The hostages and the huge expenditure ''sankin-kōtai'' imposed on each ''han'' helped to ensure loyalty to the ''shōgun''. By the 1690s, the vast majority of daimyos would be born in Edo, and most would consider it their homes. Some daimyos had little interest in their domains and needed to be begged to return "home".

In return for the centralization, peace among the daimyos was maintained; unlike in the

Regardless of the political title of the Emperor, the ''shōguns'' of the Tokugawa family controlled Japan. The shogunate secured a nominal grant of by the

Regardless of the political title of the Emperor, the ''shōguns'' of the Tokugawa family controlled Japan. The shogunate secured a nominal grant of by the

Foreign affairs and trade were monopolized by the shogunate, yielding a huge profit. Foreign trade was also permitted for the Satsuma and the Tsushima domains.

Foreign affairs and trade were monopolized by the shogunate, yielding a huge profit. Foreign trade was also permitted for the Satsuma and the Tsushima domains.

In principle, the requirements for appointment to the office of rōjū were to be a '' fudai daimyō'' and to have a fief assessed at ''

In principle, the requirements for appointment to the office of rōjū were to be a '' fudai daimyō'' and to have a fief assessed at ''

Japan

SengokuDaimyo.com

– the website of Samurai Author and Historian Anthony J. Bryant

Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan

by M.C. Perry, at

military government

A military government is any government that is administered by a military, whether or not this government is legal under the laws of the jurisdiction at issue or by an occupying power. It is usually administered by military personnel.

Types of m ...

of Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

during the Edo period

The , also known as the , is the period between 1600 or 1603 and 1868 in the history of Japan, when the country was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and some 300 regional ''daimyo'', or feudal lords. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengok ...

from 1603 to 1868.

The Tokugawa shogun

, officially , was the title of the military aristocracy, rulers of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor of Japan, Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, exc ...

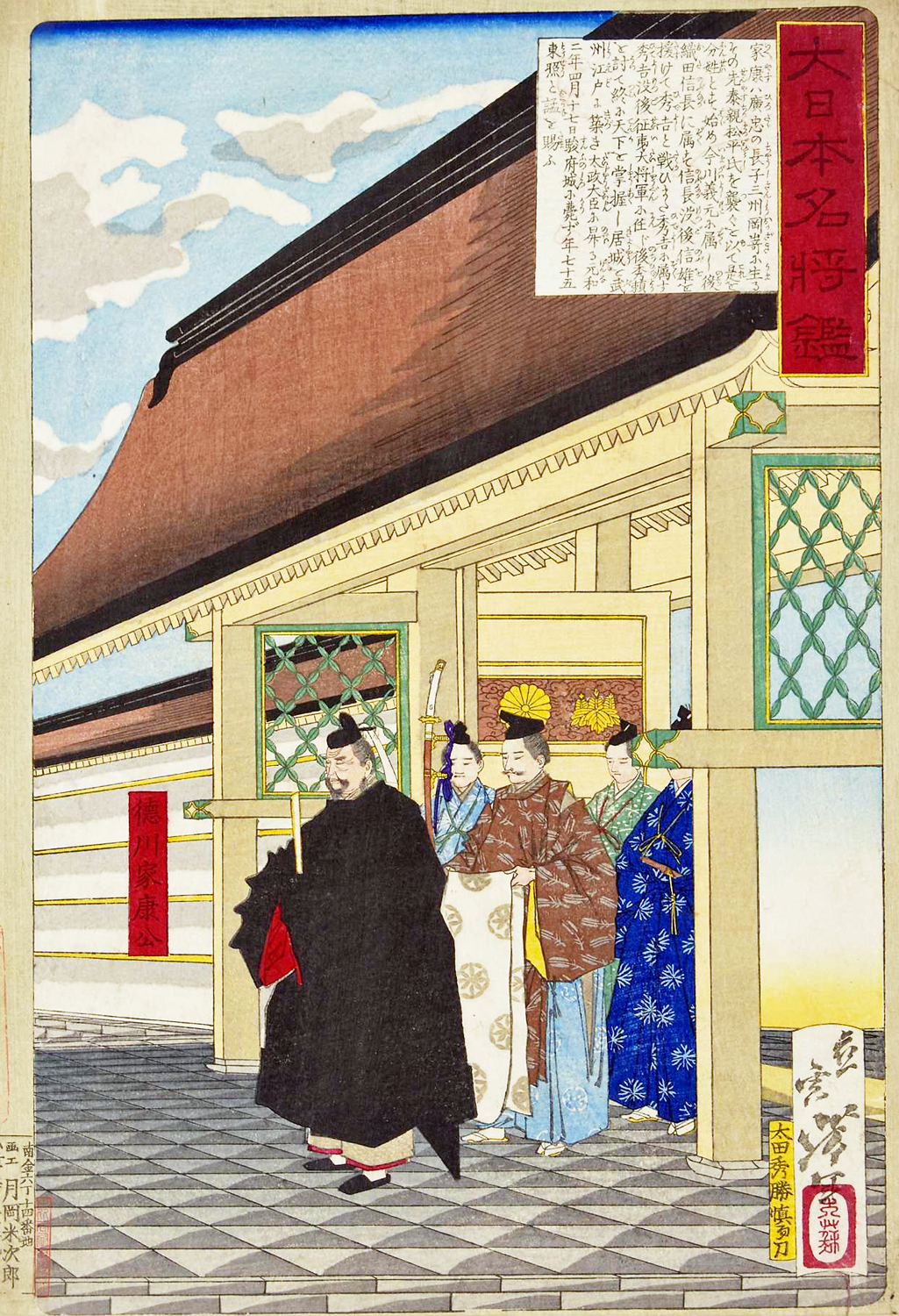

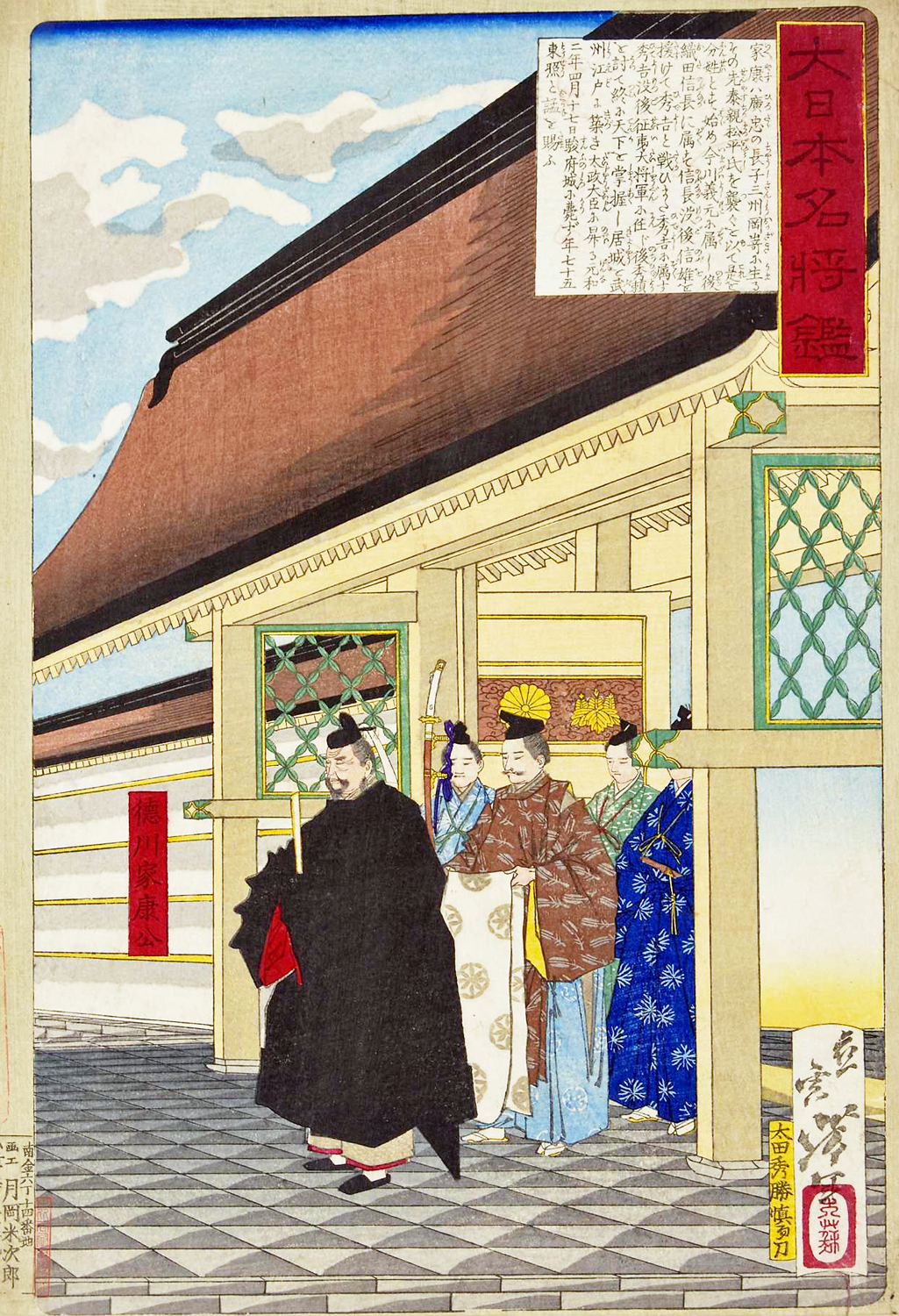

ate was established by Tokugawa Ieyasu

Tokugawa Ieyasu (born Matsudaira Takechiyo; 31 January 1543 – 1 June 1616) was the founder and first ''shōgun'' of the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan, which ruled from 1603 until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. He was the third of the three "Gr ...

after victory at the Battle of Sekigahara

The Battle of Sekigahara (Shinjitai: ; Kyūjitai: , Hepburn romanization: ''Sekigahara no Tatakai'') was an important battle in Japan which occurred on October 21, 1600 (Keichō 5, 15th day of the 9th month) in what is now Gifu Prefecture, ...

, ending the civil wars of the Sengoku period

The was the period in History of Japan, Japanese history in which civil wars and social upheavals took place almost continuously in the 15th and 16th centuries. The Kyōtoku incident (1454), Ōnin War (1467), or (1493) are generally chosen as th ...

following the collapse of the Ashikaga shogunate. Ieyasu became the ''shōgun

, officially , was the title of the military rulers of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, except during parts of the Kamak ...

,'' and the Tokugawa clan

The is a Japanese dynasty which produced the Tokugawa shoguns who ruled Japan from 1603 to 1868 during the Edo period. It was formerly a powerful ''daimyō'' family. They nominally descended from Emperor Seiwa (850–880) and were a branch of ...

governed Japan from Edo Castle

is a flatland castle that was built in 1457 by Ōta Dōkan in Edo, Toshima District, Musashi Province. In modern times it is part of the Tokyo Imperial Palace in Chiyoda, Tokyo, and is therefore also known as .

Tokugawa Ieyasu established th ...

in the eastern city of Edo (Tokyo

Tokyo, officially the Tokyo Metropolis, is the capital of Japan, capital and List of cities in Japan, most populous city in Japan. With a population of over 14 million in the city proper in 2023, it is List of largest cities, one of the most ...

) along with the ''daimyō

were powerful Japanese magnates, feudal lords who, from the 10th century to the early Meiji era, Meiji period in the middle 19th century, ruled most of Japan from their vast hereditary land holdings. They were subordinate to the shogun and no ...

'' lords of the ''samurai

The samurai () were members of the warrior class in Japan. They were originally provincial warriors who came from wealthy landowning families who could afford to train their men to be mounted archers. In the 8th century AD, the imperial court d ...

'' class.

The Tokugawa shogunate organized Japanese society under the strict Tokugawa class system and banned most foreigners under the isolationist policies of ''Sakoku

is the most common name for the isolationist foreign policy of the Japanese Tokugawa shogunate under which, during the Edo period (from 1603 to 1868), relations and trade between Japan and other countries were severely limited, and almost all ...

'' to promote political stability. The Tokugawa shoguns governed Japan in a feudal system, with each ''daimyō'' administering a '' han'' (feudal domain), although the country was still nominally organized as imperial provinces. Under the Tokugawa shogunate, Japan experienced rapid economic growth and urbanization, which led to the rise of the merchant class and '' Ukiyo'' culture.

The Tokugawa shogunate declined during the ''Bakumatsu

were the final years of the Edo period when the Tokugawa shogunate Meiji Restoration, ended. Between 1853 and 1867, under foreign diplomatic and military pressure, Japan ended its isolationist foreign policy known as and changed from a Feudali ...

'' period from 1853 and was overthrown by supporters of the Imperial Court in the Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored Imperial House of Japan, imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Althoug ...

in 1868. The Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From Japan–Kor ...

was established under the Meiji government

The was the government that was formed by politicians of the Satsuma Domain and Chōshū Domain in the 1860s. The Meiji government was the early government of the Empire of Japan.

Politicians of the Meiji government were known as the Meiji ...

, and Tokugawa loyalists continued to fight in the Boshin War

The , sometimes known as the Japanese Revolution or Japanese Civil War, was a civil war in Japan fought from 1868 to 1869 between forces of the ruling Tokugawa shogunate and a coalition seeking to seize political power in the name of the Impe ...

until the defeat of the Republic of Ezo at the Battle of Hakodate in June 1869.

History

Following the Sengoku period ("Warring States period"), the central government had been largely re-established byOda Nobunaga

was a Japanese ''daimyō'' and one of the leading figures of the Sengoku period, Sengoku and Azuchi-Momoyama periods. He was the and regarded as the first "Great Unifier" of Japan. He is sometimes referred as the "Demon Daimyō" and "Demo ...

during the Azuchi–Momoyama period

The was the final phase of the in Japanese history from 1568 to 1600.

After the outbreak of the Ōnin War in 1467, the power of the Ashikaga Shogunate effectively collapsed, marking the start of the chaotic Sengoku period. In 1568, Oda Nob ...

. After the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, central authority fell to Tokugawa Ieyasu. While many ''daimyos'' who fought against him were extinguished or had their holdings reduced, Ieyasu was committed to retaining the ''daimyos'' and the ''han'' (domains) as components under his new shogunate. ''Daimyos'' who sided with Ieyasu were rewarded, and some of Ieyasu's former vassals were made ''daimyos'' and were located strategically throughout the country. The ''sankin-kotai'' policy, in an effort to constrain rebellions by the daimyos, mandated the housing of wives and children of the ''daimyos'' in the capital as hostages.

In 1616, there was a failed attempt of the invasion of Taiwan by a Shogunate subject named Murayama Tōan.Taiwan GovernmentA long period of peace occurred between the

Siege of Osaka

A siege () . is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or by well-prepared assault. Siege warfare (also called siegecrafts or poliorcetics) is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict charact ...

in 1615 and the Keian Uprising in 1651. This period saw the bakufu

, officially , was the title of the military rulers of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, except during parts of the Kamak ...

(shogunate's administration) prioritise civil administration, while civil society witnessed a surge in trade and industrial activities. Trade under the reign of Ieyasu saw much new wealth created by mining and goods manufacturing, which resulted in a rural population flow to urban areas. By the Genroku period (1688–1704) Japan saw a period of material prosperity and the blossoming of the arts, such as the early development of ''ukiyo-e

is a genre of Japanese art that flourished from the 17th through 19th centuries. Its artists produced woodblock printing, woodblock prints and Nikuhitsu-ga, paintings of such subjects as female beauties; kabuki actors and sumo wrestlers; scenes ...

'' by Moronobu. The reign of Tokugawa Yoshimune (1716–1745) saw poor harvests and a fall in tax revenue in the early 1720s, as a result he pushed for the Kyoho reforms to repair the finances of the bakufu as he believed the military aristocracy was losing its power against the rich merchants and landowners.

Society in the Tokugawa period, unlike in previous shogunates, was supposedly based on the strict class hierarchy originally established by Toyotomi Hideyoshi

, otherwise known as and , was a Japanese samurai and ''daimyō'' (feudal lord) of the late Sengoku period, Sengoku and Azuchi-Momoyama periods and regarded as the second "Great Unifier" of Japan.Richard Holmes, The World Atlas of Warfare: ...

. The ''daimyō'' (lords) were at the top, followed by the warrior-caste of samurai, with the farmers, artisans, and traders ranking below. In some parts of the country, particularly smaller regions, ''daimyō,'' and samurai were more or less identical, since ''daimyō'' might be trained as samurai, and samurai might act as local rulers.

The largely inflexible nature of this social stratification system unleashed disruptive forces over time. Taxes on the peasantry were set at fixed amounts that did not account for inflation or other changes in monetary value. As a result, the tax revenues collected by the samurai landowners increasingly declined over time. A 2017 study found that peasant rebellions and desertion lowered tax rates and inhibited state growth in the Tokugawa shogunate. By the mid-18th century, both the ''shogun'' and ''daimyos'' were hampered by financial difficulties, whereas more wealth flowed to the merchant class. Peasant uprisings and samurai discontent became increasingly prevalent. Some reforms were enacted to attend to these issues such as the Kansei reform (1787–1793) by Matsudaira Sadanobu. He bolstered the bakufu's rice stockpiles and mandated ''daimyos'' to follow suit. He cut down urban spending, allocated reserves for potential famines, and urged city-dwelling peasants to return to rural areas.

By 1800, Japan included five cities with over 100,000 residents, and three among the world's twenty cities that had more than 300,000 inhabitants. Edo likely claimed the title of the world's most populous city, housing over one million people.

Christians under the Shogunate

Followers ofCatholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

Christians first began appearing in Japan during the 16th century. Oda Nobunaga

was a Japanese ''daimyō'' and one of the leading figures of the Sengoku period, Sengoku and Azuchi-Momoyama periods. He was the and regarded as the first "Great Unifier" of Japan. He is sometimes referred as the "Demon Daimyō" and "Demo ...

embraced Christianity and the Western technology that was imported with it, such as the musket. He also saw it as a tool he could use to suppress Buddhist forces.

Though Christianity was allowed to grow until the 1610s, Tokugawa Ieyasu

Tokugawa Ieyasu (born Matsudaira Takechiyo; 31 January 1543 – 1 June 1616) was the founder and first ''shōgun'' of the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan, which ruled from 1603 until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. He was the third of the three "Gr ...

soon began to see it as a growing threat to the stability of the shogunate. As ''Ōgosho'' ("Cloistered ''Shōgun''"), he influenced the implementation of laws that banned the practice of Christianity. His successors followed suit, compounding upon Ieyasu's laws. The ban of Christianity is often linked with the creation of the Seclusion laws, or Sakoku

is the most common name for the isolationist foreign policy of the Japanese Tokugawa shogunate under which, during the Edo period (from 1603 to 1868), relations and trade between Japan and other countries were severely limited, and almost all ...

, in the 1630s.

Late Tokugawa shogunate (1853–1867)

The late Tokugawa shogunate ( ''Bakumatsu'') was the period between 1853 and 1867, during which Japan ended its isolationist foreign policy called ''

The late Tokugawa shogunate ( ''Bakumatsu'') was the period between 1853 and 1867, during which Japan ended its isolationist foreign policy called ''sakoku

is the most common name for the isolationist foreign policy of the Japanese Tokugawa shogunate under which, during the Edo period (from 1603 to 1868), relations and trade between Japan and other countries were severely limited, and almost all ...

'' and modernized from a feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of struc ...

shogunate to the Meiji government

The was the government that was formed by politicians of the Satsuma Domain and Chōshū Domain in the 1860s. The Meiji government was the early government of the Empire of Japan.

Politicians of the Meiji government were known as the Meiji ...

. The 1850s saw growing resentment by the '' tozama daimyōs'' and anti-Western sentiment

Anti-Western sentiment, also known as anti-Atlanticism or Westernophobia, refers to broad opposition, bias, or hostility towards the people, culture, or policies of the Western world.

This sentiment is found worldwide. It often stems from ant ...

following the arrival of a U.S. Navy fleet under the command of Matthew C. Perry

Matthew Calbraith Perry (April 10, 1794 – March 4, 1858) was a United States Navy officer who commanded ships in several wars, including the War of 1812 and the Mexican–American War. He led the Perry Expedition that Bakumatsu, ended Japan' ...

(which led to the forced opening of Japan). The major ideological and political factions during this period were divided into the pro-imperialist '' Ishin Shishi'' (nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

patriots) and the shogunate forces; aside from the dominant two groups, other factions attempted to use the chaos of the Bakumatsu era to seize personal power.

An alliance of ''daimyos'' and the emperor succeeded in overthrowing the shogunate, which came to an official end in 1868 with the resignation of the 15th Tokugawa shogun'','' Tokugawa Yoshinobu

Kazoku, Prince was the 15th and last ''shōgun'' of the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan. He was part of a movement which aimed to reform the aging shogunate, but was ultimately unsuccessful. He resigned his position as shogun in late 1867, while ai ...

, leading to the "restoration" ( 王政復古, ''Ōsei fukko'') of imperial rule. Some loyal retainers of the shogun continued to fight during the Boshin War

The , sometimes known as the Japanese Revolution or Japanese Civil War, was a civil war in Japan fought from 1868 to 1869 between forces of the ruling Tokugawa shogunate and a coalition seeking to seize political power in the name of the Impe ...

that followed but were eventually defeated in the notable Battle of Toba–Fushimi.

Government

Shogunate and domains

The ''bakuhan'' system (''bakuhan taisei'' ) was thefeudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of struc ...

political system in the Edo period of Japan. ''Baku'' is an abbreviation of ''bakufu'', meaning "military government

A military government is any government that is administered by a military, whether or not this government is legal under the laws of the jurisdiction at issue or by an occupying power. It is usually administered by military personnel.

Types of m ...

"—that is, the shogunate. The ''han'' were the domains headed by ''daimyō''. Beginning from Ieyasu's appointment as shogun in 1603, but especially after the Tokugawa victory in Osaka in 1615, various policies were implemented to assert the shogunate's control, which severely curtailed the ''daimyos independence. The number of ''daimyos'' varied but stabilized at around 270.

The ''bakuhan'' system split feudal power between the shogunate in Edo and the ''daimyōs'' with domains throughout Japan. The ''shōgun'' and lords were all ''daimyōs'': feudal lords with their own bureaucracies, policies, and territories. Provinces had a degree of sovereignty and were allowed an independent administration of the ''han'' in exchange for loyalty to the ''shōgun'', who was responsible for foreign relations, national security, coinage, weights, measures, and transportation.

The ''shōgun'' also administered the most powerful ''han'', the hereditary fief of the House of Tokugawa, which also included many gold and silver mines. Towards the end of the shogunate, the Tokugawa clan held around 7 million ''koku

The is a Chinese-based Japanese unit of volume. One koku is equivalent to 10 or approximately , or about of rice. It converts, in turn, to 100 shō and 1,000 gō. One ''gō'' is the traditional volume of a single serving of rice (before co ...

'' of land (天領 tenryō), including 2.6–2.7 million ''koku'' held by direct vassals, out of 30 million in the country. The other 23 million ''koku'' were held by other daimyos.

The number of ''han'' (roughly 270) fluctuated throughout the Edo period. They were ranked by size, which was measured as the number of ''koku'' of rice that the domain produced each year. One ''koku'' was the amount of rice necessary to feed one adult male for one year. The minimum number for a ''daimyō'' was ten thousand ''koku''; the largest, apart from the ''shōgun'', was more than a million ''koku''.

Policies to control the daimyos

The main policies of the shogunate on the ''daimyos'' included: * The principle was that each ''daimyo'' (including those who were previously independent of the Tokugawa family) submitted to the shogunate, and each ''han'' required the shogunate's recognition and was subject to its land redistributions. ''Daimyos'' swore allegiance to each shogun and acknowledged the Laws for Warrior Houses or ''buke shohatto''. * The ''sankin-kōtai

''Sankin-kōtai'' (, now commonly written as ) was a policy of the Tokugawa shogunate during most of the Edo period, created to control the daimyo, the feudal lords of Japan, politically, and to keep them from attempting to overthrow the regi ...

'' (参勤交代 "alternate attendance") system, required ''daimyos'' to travel to and reside in Edo every other year, and for their families to remain in Edo during their absence.

* The ''ikkoku ichijyō rei'' (一国一城令), allowed each daimyo's ''han'' to retain only one fortification, at the ''daimyo's'' residence.

* The Laws for the Military Houses (武家諸法度, ''buke shohatto''), the first of which in 1615 forbade the building of new fortifications or repairing existing ones without ''bakufu'' approval, admitting fugitives of the shogunate, and arranging marriages of the daimyos' families without official permission. Additional rules on the samurai were issued over the years.

Although the shogun issued certain laws, such as the ''buke shohatto'' on the ''daimyōs'' and the rest of the samurai class, each ''han'' administered its autonomous system of laws and taxation

A tax is a mandatory financial charge or levy imposed on an individual or legal person, legal entity by a governmental organization to support government spending and public expenditures collectively or to Pigouvian tax, regulate and reduce nega ...

. The ''shōgun'' did not interfere in a ''han'' The shogunate had the power to discard, annex, and transform domains, although they were rarely and carefully exercised after the early years of the shogunate, to prevent ''daimyōs'' from banding together. The ''sankin-kōtai'' system of alternative residence required each ''daimyō'' to reside in alternate years between the ''han'' and the court in Edo. During their absences from Edo, it was also required that they leave their family as hostages until their return. The hostages and the huge expenditure ''sankin-kōtai'' imposed on each ''han'' helped to ensure loyalty to the ''shōgun''. By the 1690s, the vast majority of daimyos would be born in Edo, and most would consider it their homes. Some daimyos had little interest in their domains and needed to be begged to return "home".

In return for the centralization, peace among the daimyos was maintained; unlike in the

The shogunate had the power to discard, annex, and transform domains, although they were rarely and carefully exercised after the early years of the shogunate, to prevent ''daimyōs'' from banding together. The ''sankin-kōtai'' system of alternative residence required each ''daimyō'' to reside in alternate years between the ''han'' and the court in Edo. During their absences from Edo, it was also required that they leave their family as hostages until their return. The hostages and the huge expenditure ''sankin-kōtai'' imposed on each ''han'' helped to ensure loyalty to the ''shōgun''. By the 1690s, the vast majority of daimyos would be born in Edo, and most would consider it their homes. Some daimyos had little interest in their domains and needed to be begged to return "home".

In return for the centralization, peace among the daimyos was maintained; unlike in the Sengoku period

The was the period in History of Japan, Japanese history in which civil wars and social upheavals took place almost continuously in the 15th and 16th centuries. The Kyōtoku incident (1454), Ōnin War (1467), or (1493) are generally chosen as th ...

, daimyos no longer worried about conflicts with one another. In addition, hereditary succession was guaranteed as internal usurpations within domains were not recognized by the shogunate.

Classification of daimyos

The Tokugawa clan further ensured loyalty by maintaining a dogmatic insistence on loyalty to the ''shōgun''. Daimyos were classified into three main categories: * '' Shinpan'' ("relatives" 親藩) were six clans established by sons of Ieyasu, as well as certain sons of the 8th and 9th shoguns, who were made daimyos. They would provide an heir to the shogunate if the shogun did not have an heir. * '' Fudai'' ("hereditary" 譜代) were mostly vassals of Ieyasu and the Tokugawa clan before theBattle of Sekigahara

The Battle of Sekigahara (Shinjitai: ; Kyūjitai: , Hepburn romanization: ''Sekigahara no Tatakai'') was an important battle in Japan which occurred on October 21, 1600 (Keichō 5, 15th day of the 9th month) in what is now Gifu Prefecture, ...

. They ruled their ''han'' (estate) and served as high officials in the shogunate, although their ''han'' tended to be smaller compared to the ''tozama'' domains.

* '' Tozama'' ("outsiders" 外様) were around 100 daimyos, most of whom became vassals of the Tokugawa clan after the Battle of Sekigahara. Some fought against Tokugawa forces, although some were neutral or even fought on the side of the Tokugawa clan, as allies rather than vassals. The ''tozama daimyos'' tend to have the largest ''han'', with 11 of the 16 largest daimyos in this category.

The ''tozama daimyos'' who fought against the Tokugawa clan in the Battle of Sekigahara had their estate reduced substantially. They were often placed in mountainous or far away areas, or placed between most trusted daimyos. Early in the Edo period, the shogunate viewed the ''tozama'' as the least likely to be loyal; over time, strategic marriages and the entrenchment of the system made the ''tozama'' less likely to rebel. In the end, however, it was still the great ''tozama'' of Satsuma, Chōshū and Tosa, and to a lesser extent Saga

Sagas are prose stories and histories, composed in Iceland and to a lesser extent elsewhere in Scandinavia.

The most famous saga-genre is the (sagas concerning Icelanders), which feature Viking voyages, migration to Iceland, and feuds between ...

, that brought down the shogunate. These four states are called the Four Western Clans, or Satchotohi for short.

Relations with the Emperor

Regardless of the political title of the Emperor, the ''shōguns'' of the Tokugawa family controlled Japan. The shogunate secured a nominal grant of by the

Regardless of the political title of the Emperor, the ''shōguns'' of the Tokugawa family controlled Japan. The shogunate secured a nominal grant of by the Imperial Court in Kyoto

The Imperial Court in Kyoto was the nominal ruling government of Japan from 794 AD until the Meiji period (1868–1912), after which the court was moved from Kyoto (formerly Heian-kyō) to Tokyo (formerly Edo) and integrated into the Meiji go ...

to the Tokugawa family. While the Emperor officially had the prerogative of appointing the ''shōgun'' and received generous subsidies, he had virtually no say in state affairs. The shogunate issued the Laws for the Imperial and Court Officials (''kinchu narabini kuge shohatto'' 禁中並公家諸法度) to set out its relationship with the Imperial family

A royal family is the immediate family of monarch, monarchs and sometimes their extended family.

The term imperial family appropriately describes the family of an emperor or emperor, empress, and the term papal family describes the family of ...

and the ''kuge

The was a Japanese Aristocracy (class), aristocratic Social class, class that dominated the Japanese Imperial Court in Kyoto. The ''kuge'' were important from the establishment of Kyoto as the capital during the Heian period in the late 8th ce ...

'' (imperial court officials), and specified that the Emperor should dedicate to scholarship and poetry. The shogunate also appointed a liaison, the '' Kyoto Shoshidai'' (''Shogun's Representative in Kyoto''), to deal with the Emperor, court and nobility.

Towards the end of the shogunate, however, after centuries of the Emperor having very little say in state affairs and being secluded in his Kyoto palace, and in the wake of the reigning ''shōgun'', Tokugawa Iemochi

(17 July 1846 – 29 August 1866) was the 14th '' shōgun'' of the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan, who held office from 1858 to 1866.

During his reign there was much internal turmoil as a result of the "re-opening" of Japan to western nations. I ...

, marrying the sister of Emperor Kōmei

Osahito (22 July 1831 – 30 January 1867), posthumously honored as Emperor Kōmei, was the 121st emperor of Japan, according to the List of Emperors of Japan, traditional order of succession.Imperial Household Agency (''Kunaichō'')孝明天皇 ...

(r. 1846–1867), in 1862, the Imperial Court in Kyoto began to enjoy increased political influence. The Emperor would occasionally be consulted on various policies and the shogun even made a visit to Kyoto to visit the Emperor. Government administration would be formally returned from the ''shogun'' to the Emperor during the Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored Imperial House of Japan, imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Althoug ...

in 1868.

Shogun and foreign trade

Foreign affairs and trade were monopolized by the shogunate, yielding a huge profit. Foreign trade was also permitted for the Satsuma and the Tsushima domains.

Foreign affairs and trade were monopolized by the shogunate, yielding a huge profit. Foreign trade was also permitted for the Satsuma and the Tsushima domains. Rice

Rice is a cereal grain and in its Domestication, domesticated form is the staple food of over half of the world's population, particularly in Asia and Africa. Rice is the seed of the grass species ''Oryza sativa'' (Asian rice)—or, much l ...

was the main trading product of Japan during this time. Isolationism

Isolationism is a term used to refer to a political philosophy advocating a foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality an ...

was the foreign policy of Japan and trade was strictly controlled. Merchants were outsiders to the social hierarchy

Social stratification refers to a society's categorization of its people into groups based on socioeconomic factors like wealth, income, race, education, ethnicity, gender, occupation, social status, or derived power (social and political). ...

of Japan and were thought to be greedy.

The visits of the Nanban ships from Portugal were at first the main vector of trade exchanges, followed by the addition of Dutch, English, and sometimes Spanish ships.

From 1603 onward, Japan started to participate actively in foreign trade. In 1615, an embassy and trade mission under Hasekura Tsunenaga

was a kirishitan Japanese samurai and retainer of Date Masamune, the daimyō of Sendai. He was of Japanese imperial descent with ancestral ties to Emperor Kanmu. Other names include Philip Francis Faxicura, Felipe Francisco Faxicura, and Ph ...

was sent across the Pacific to Nueva España (New Spain) on the Japanese-built galleon ''San Juan Bautista''. Until 1635, the Shogun issued numerous permits for the so-called " red seal ships" destined for the Asian trade.

After 1635 and the introduction of seclusion laws (''sakoku''), inbound ships were only allowed from China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, Korea

Korea is a peninsular region in East Asia consisting of the Korean Peninsula, Jeju Island, and smaller islands. Since the end of World War II in 1945, it has been politically Division of Korea, divided at or near the 38th parallel north, 3 ...

, and the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

.

Government income

The primary source of the shogunate's income was the tax (around 40%) levied on harvests in the Tokugawa clan's personal domains (tenryō). No taxes were levied on domains of daimyos, who instead provided military duty, public works and corvee. The shogunate obtained loans from merchants, which were sometimes seen as forced donations, although commerce was often not taxed. Special levies were also imposed for infrastructure-building.Shogunate institution

During the earliest years of the Tokugawa shogunate institution, when Tokugawa Hidetada coronated as the second shogun and Ieyasu retired, they formed a dual governments, where Hidetada controlled the official court with the government central located in Edo city, Ieyasu, who now became the ''Ōgosho'' (retired shogun), also control his own informal shadow government which called "Sunpu government" with its center at Sunpu Castle. The membership of the Sunpu government's cabinet was consisted of trusted vassals of Ieyasu which was not included in Hidetada's cabinet. including William Adams (samurai) and Jan Joosten van Lodensteijn, which Ieyasu entrusted with foreign affairs and diplomacy. The earliest structure of Edo Shogunate organization has ''Buke Shitsuyaku'' as the highest rank. the earliest members of this office were Ii Naomasa, Sakakibara Yasumasa, and Honda Tadakatsu. The personal vassals of the Tokugawa shoguns were classified into two groups: * the bannermen (''hatamoto'' 旗本) had the privilege to directly approach the shogun; * the housemen (''gokenin'' 御家人) did not have the privilege of the shogun's audience. By the early 18th century, out of around 22,000 personal vassals, most would have received stipends rather than domains.Rōjū and wakadoshiyori

The '' rōjū'' () were normally the most senior members of the shogunate. Normally, four or five men held the office, and one was on duty for a month at a time on a rotating basis. They supervised the '' ōmetsuke'' (who checked on the daimyos), ''machi''-''bugyō'' (commissioners of administrative and judicial functions in major cities, especially Edo), ' (遠国奉行, the commissioners of other major cities and shogunate domains) and other officials, oversaw relations with theImperial Court in Kyoto

The Imperial Court in Kyoto was the nominal ruling government of Japan from 794 AD until the Meiji period (1868–1912), after which the court was moved from Kyoto (formerly Heian-kyō) to Tokyo (formerly Edo) and integrated into the Meiji go ...

, kuge

The was a Japanese Aristocracy (class), aristocratic Social class, class that dominated the Japanese Imperial Court in Kyoto. The ''kuge'' were important from the establishment of Kyoto as the capital during the Heian period in the late 8th ce ...

(members of the nobility), daimyō, Buddhist temples and Shinto shrine

A Stuart D. B. Picken, 1994. p. xxiii is a structure whose main purpose is to house ("enshrine") one or more kami, , the deities of the Shinto religion.

The Also called the . is where a shrine's patron is or are enshrined.Iwanami Japanese dic ...

s, and attended to matters like divisions of fief

A fief (; ) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form of feudal alle ...

s. Other ''bugyō'' (commissioners) in charge of finances, monasteries and shrines also reported to the rōjū. The roju conferred on especially important matters. In the administrative reforms of 1867 ( Keiō Reforms), the office was eliminated in favor of a bureaucratic system with ministers for the interior, finance, foreign relations, army, and navy.

In principle, the requirements for appointment to the office of rōjū were to be a '' fudai daimyō'' and to have a fief assessed at ''

In principle, the requirements for appointment to the office of rōjū were to be a '' fudai daimyō'' and to have a fief assessed at ''koku

The is a Chinese-based Japanese unit of volume. One koku is equivalent to 10 or approximately , or about of rice. It converts, in turn, to 100 shō and 1,000 gō. One ''gō'' is the traditional volume of a single serving of rice (before co ...

'' or more. However, there were exceptions to both criteria. Many appointees came from the offices close to the ''shōgun'', such as ' (側用人), Kyoto Shoshidai, and Osaka-jō dai.

Irregularly, the ''shōguns'' appointed a ''rōjū'' to the position of '' tairō'' (great elder). The office was limited to members of the Ii, Sakai

is a city located in Osaka Prefecture, Japan. It has been one of the largest and most important seaports of Japan since the medieval era. Sakai is known for its '' kofun'', keyhole-shaped burial mounds dating from the fifth century. The ''kofun ...

, Doi, and Hotta clans, but Yanagisawa Yoshiyasu was given the status of tairō as well. Among the most famous was Ii Naosuke, who was assassinated in 1860 outside the Sakuradamon Gate of Edo Castle

is a flatland castle that was built in 1457 by Ōta Dōkan in Edo, Toshima District, Musashi Province. In modern times it is part of the Tokyo Imperial Palace in Chiyoda, Tokyo, and is therefore also known as .

Tokugawa Ieyasu established th ...

( Sakuradamon incident).

Three to five men titled the '' wakadoshiyori'' (若年寄) were next in status below the rōjū. An outgrowth of the early six-man '' rokuninshū'' (六人衆, 1633–1649), the office took its name and final form in 1662. Their primary responsibility was management of the affairs of the hatamoto

A was a high ranking samurai in the direct service of the Tokugawa shogunate of feudal Japan. While all three of the Shōgun, shogunates in History of Japan, Japanese history had official retainers, in the two preceding ones, they were referred ...

and gokenin

A was initially a vassal of the shogunate of the Kamakura and the Muromachi periods.Iwanami Kōjien, "Gokenin" In exchange for protection and the right to become '' jitō'' (manor's lord), a ''gokenin'' had in times of peace the duty to protect ...

, the direct vassals of the ''shōgun''. Under the ''wakadoshiyori'' were the '' metsuke''.

Some ''shōguns'' appointed a ''soba yōnin''. This person acted as a liaison between the ''shōgun'' and the ''rōjū''. The ''soba yōnin'' increased in importance during the time of the fifth ''shōgun'' Tokugawa Tsunayoshi, when a wakadoshiyori, Inaba Masayasu, assassinated Hotta Masatoshi

was a ''daimyō'' (feudal lord) in Shimōsa Province, and top government advisor and official in the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan. He served as ''rōjū'' (chief advisor) to ''shōgun'' Tokugawa Ietsuna from 1679–80, and as ''Tairō'' (head of t ...

, the ''tairō''. Fearing for his personal safety, Tsunayoshi moved the ''rōjū'' to a more distant part of the castle. Some of the most famous ''soba yōnin'' were Yanagisawa Yoshiyasu and Tanuma Okitsugu.

Ōmetsuke and metsuke

The ''ōmetsuke'' and '' metsuke'' were officials who reported to the ''rōjū'' and ''wakadoshiyori''. The five ''ōmetsuke'' were in charge of monitoring the affairs of the ''daimyōs'', ''kuge'' and imperial court. They were in charge of discovering any threat of rebellion. Early in the Edo period, ''daimyōs'' such as Yagyū Munefuyu held the office. Soon, however, it fell to ''hatamoto

A was a high ranking samurai in the direct service of the Tokugawa shogunate of feudal Japan. While all three of the Shōgun, shogunates in History of Japan, Japanese history had official retainers, in the two preceding ones, they were referred ...

'' with rankings of 5,000 ''koku'' or more. To give them authority in their dealings with ''daimyōs'', they were often ranked at 10,000 ''koku'' and given the title of ''kami

are the Deity, deities, Divinity, divinities, Spirit (supernatural entity), spirits, mythological, spiritual, or natural phenomena that are venerated in the traditional Shinto religion of Japan. ''Kami'' can be elements of the landscape, forc ...

'' (an ancient title, typically signifying the governor of a province

A province is an administrative division within a country or sovereign state, state. The term derives from the ancient Roman , which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire, Roman Empire's territorial possessions ou ...

) such as ''Bizen-no-kami''.

As time progressed, the function of the ''ōmetsuke'' evolved into one of passing orders from the shogunate to the ''daimyōs'', and of administering to ceremonies within Edo Castle. They also took on additional responsibilities such as supervising religious affairs and controlling firearms. The ''metsuke'', reporting to the ''wakadoshiyori'', oversaw the affairs of the vassals of the ''shōgun''. They were the police force for the thousands of hatamoto and gokenin

A was initially a vassal of the shogunate of the Kamakura and the Muromachi periods.Iwanami Kōjien, "Gokenin" In exchange for protection and the right to become '' jitō'' (manor's lord), a ''gokenin'' had in times of peace the duty to protect ...

who were concentrated in Edo. Individual ''han'' had their own ''metsuke'' who similarly policed their samurai.

San-bugyō

The ''san-bugyō

was a title assigned to ''samurai'' officials in feudal Japan. ''Bugyō'' is often translated as commissioner, magistrate, or governor, and other terms would be added to the title to describe more specifically a given official's tasks or jurisdi ...

'' (三奉行 "three administrators") were the ''jisha'', ''kanjō'', and '' machi-bugyō'', which respectively oversaw temples

A temple (from the Latin ) is a place of worship, a building used for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. By convention, the specially built places of worship of some religions are commonly called "temples" in Engli ...

and shrines

A shrine ( "case or chest for books or papers"; Old French: ''escrin'' "box or case") is a sacred space dedicated to a specific deity, ancestor worship, ancestor, hero, martyr, saint, Daemon (mythology), daemon, or similar figure of respect, wh ...

, accounting, and the cities. The '' jisha-bugyō'' had the highest status of the three. They oversaw the administration of Buddhist temples (''ji'') and Shinto shrines (''sha''), many of which held fiefs. Also, they heard lawsuits from several land holdings outside the eight Kantō provinces. The appointments normally went to ''daimyōs''; Ōoka Tadasuke was an exception, though he later became a ''daimyō''.

The '' kanjō-bugyō'' were next in status. The four holders of this office reported to the ''rōjū''. They were responsible for the finances of the shogunate.

The ''machi-bugyō'' were the chief city administrators of Edo and other cities. Their roles included mayor, chief of the police (and, later, also of the fire department), and judge in criminal and civil matters not involving samurai. Two (briefly, three) men, normally hatamoto, held the office, and alternated by month.

Three Edo ''machi bugyō'' have become famous through ''jidaigeki

is a genre of film, television, and theatre in Japan. Literally meaning "historical drama, period dramas", it refers to stories that take place before the Meiji Restoration of 1868.

''Jidaigeki'' show the lives of the samurai, farmers, crafts ...

'' (period films): Ōoka Tadasuke and Tōyama Kagemoto (Kinshirō) as heroes, and Torii Yōzō ( :ja:鳥居耀蔵) as a villain.

Tenryō, gundai and daikan

The ''san-bugyō'' together sat on a council called the '' hyōjōsho'' (評定所). In this capacity, they were responsible for administering the ''tenryō'' (the shogun's estates), supervising the ''gundai'' ( 郡代), the ''daikan

''Daikan'' (代官) was an official in ancient Japan that acted on behalf of a ruling monarch or a lord at the post they had been appointed to. Since the Middle Ages, ''daikan'' were in charge of their territory and territorial tax collection. In ...

'' ( 代官) and the ''kura bugyō'' ( 蔵奉行), as well as hearing cases involving samurai. The ''gundai'' managed Tokugawa domains with incomes greater than 10,000 koku while the ''daikan'' managed areas with incomes between 5,000 and 10,000 koku.

The shogun directly held lands in various parts of Japan. These were known as ''shihaisho'' (支配所); since the Meiji period, the term ''tenryō'' ( 天領, literally "Emperor's land") has become synonymous, because the shogun's lands were returned to the emperor. In addition to the territory that Ieyasu held prior to the Battle of Sekigahara, this included lands he gained in that battle and lands gained as a result of the Summer and Winter Sieges of Osaka. Major cities as Nagasaki and Osaka, and mines, including the Sado gold mine, also fell into this category.

Gaikoku bugyō

The '' gaikoku bugyō'' were administrators appointed between 1858 and 1868. They were charged with overseeing trade and diplomatic relations with foreign countries, and were based in thetreaty ports

Treaty ports (; ) were the port cities in China and Japan that were opened to foreign trade mainly by the unequal treaties forced upon them by Western powers, as well as cities in Korea opened up similarly by the Qing dynasty of China (before th ...

of Nagasaki and Kanagawa (Yokohama).

List of Tokugawa ''shōgun''

Family Tree

Over the course of the Edo period, influential relatives of the shogun included: * Tokugawa Mitsukuni of the Mito Domain * Tokugawa Nariaki of the Mito Domain * Tokugawa Mochiharu of the Hitotsubashi branch * Tokugawa Munetake of the Tayasu branch. * Matsudaira Katamori of the Aizu branch. * Matsudaira Sadanobu, born into the Tayasu branch, adopted into the Hisamatsu-Matsudaira of Shirakawa.Appendix

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * *External links

Japan

SengokuDaimyo.com

– the website of Samurai Author and Historian Anthony J. Bryant

Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan

by M.C. Perry, at

Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American 501(c)(3) organization, non-profit organization founded in 1996 by Brewster Kahle that runs a digital library website, archive.org. It provides free access to collections of digitized media including web ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Tokugawa Shogunate

States and territories established in 1600

States and territories disestablished in 1868

*

*

1600 establishments in Japan

1868 disestablishments in Japan

17th century in Japan

18th century in Japan

19th century in Japan

Military dictatorships