Dynastic Egypt on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of ancient Egypt spans the period from the early

The Nile valley of Egypt was basically uninhabitable until the work of clearing and irrigating the land along the banks was started. However, it appears that this clearance and irrigation was largely under way by the

The Nile valley of Egypt was basically uninhabitable until the work of clearing and irrigating the land along the banks was started. However, it appears that this clearance and irrigation was largely under way by the

The historical records of ancient Egypt begin with Egypt as a unified state, which occurred sometime around

The historical records of ancient Egypt begin with Egypt as a unified state, which occurred sometime around

The Old Kingdom is most commonly regarded as spanning the period of time when Egypt was ruled by the

The Old Kingdom is most commonly regarded as spanning the period of time when Egypt was ruled by the

After the fall of the Old Kingdom came a roughly 200-year stretch of time known as the First Intermediate Period, which is generally thought to include a relatively obscure set of pharaohs running from the end of the Sixth to the Tenth and most of the

After the fall of the Old Kingdom came a roughly 200-year stretch of time known as the First Intermediate Period, which is generally thought to include a relatively obscure set of pharaohs running from the end of the Sixth to the Tenth and most of the

The Middle Kingdom is the period in the history of ancient Egypt stretching from the 39th regnal year of Mentuhotep II of the

The Middle Kingdom is the period in the history of ancient Egypt stretching from the 39th regnal year of Mentuhotep II of the

The Second Intermediate Period marks a period when Egypt once again fell into disarray between the end of the Middle Kingdom and the start of the

The Second Intermediate Period marks a period when Egypt once again fell into disarray between the end of the Middle Kingdom and the start of the

This was a time of great wealth and power for Egypt. Some of the most important and best-known pharaohs ruled at this time, such as

This was a time of great wealth and power for Egypt. Some of the most important and best-known pharaohs ruled at this time, such as

Ramesses I reigned for two years and was succeeded by his son

Ramesses I reigned for two years and was succeeded by his son

After the death of

After the death of  After the withdrawal of Egypt from

After the withdrawal of Egypt from

Achaemenid Egypt can be divided into three eras: the first period of Persian occupation, 525–404 BC (when Egypt became a

Achaemenid Egypt can be divided into three eras: the first period of Persian occupation, 525–404 BC (when Egypt became a

Following Alexander's death in Babylon in 323 BC, a

Following Alexander's death in Babylon in 323 BC, a

The Ancient Egypt Site

* ttps://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN9004130489&id=qeApebusL_0C&dq=PtahHotep&as_brr=1&hl=nl Texts from the Pyramid Age Door Nigel C. Strudwick, Ronald J. Leprohon, 2005, Brill Academic Publishers

Ancient Egyptian Science: A Source Book Door Marshall Clagett, 1989

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Ancient Egypt *

prehistoric

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use o ...

settlements of the northern Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

valley to the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BC. The pharaonic period, the period in which Egypt was ruled by a pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until th ...

, is dated from the 32nd century BC

The 32nd century BC was a century that lasted from the year 3200 BC to 3101 BC.

Events

* c. 3190–3170 BC? reign of King Double Falcon of Lower Egypt. There is a strong possibility that he appears on the Palermo stone, although half his name is ...

, when Upper and Lower Egypt

In Egyptian history, the Upper and Lower Egypt period (also known as The Two Lands) was the final stage of prehistoric Egypt and directly preceded the unification of the realm. The conception of Egypt as the Two Lands was an example of the duali ...

were unified, until the country fell under Macedonian rule in 332 BC.

Chronology

;Note: For alternative 'revisions' to the chronology of Egypt, seeEgyptian chronology

The majority of Egyptologists agree on the outline and many details of the chronology of Ancient Egypt. This scholarly consensus is the so-called Conventional Egyptian chronology, which places the beginning of the Old Kingdom in the 27th centu ...

.

Egypt's history is split into several different periods according to the ruling dynasty

A dynasty is a sequence of rulers from the same family,''Oxford English Dictionary'', "dynasty, ''n''." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 1897. usually in the context of a monarchical system, but sometimes also appearing in republics. A ...

of each pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until th ...

. The dating of events is still a subject of research. The conservative dates are not supported by any reliable absolute date for a span of about three millennia. The following is the list according to conventional Egyptian chronology.

* Prehistoric Egypt

Prehistoric Egypt and Predynastic Egypt span the period from the earliest human settlement to the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period around 3100 BC, starting with the first Pharaoh, Narmer for some Egyptologists, Hor-Aha for others, with t ...

(prior to 3100 BC)

* Naqada III

Naqada III is the last phase of the Naqada culture of ancient Egyptian prehistory, dating from approximately 3200 to 3000 BC. It is the period during which the process of state formation, which began in Naqada II, became highly visible, ...

("the protodynastic period", approximately 3100–3000 BC; sometimes referred to as "Dynasty 0")

* Early Dynastic Period (First

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and reco ...

– Second Dynasties)

* Old Kingdom

In ancient Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom is the period spanning c. 2700–2200 BC. It is also known as the "Age of the Pyramids" or the "Age of the Pyramid Builders", as it encompasses the reigns of the great pyramid-builders of the Fourt ...

(Third

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* 1⁄60 of a ''second'', or 1⁄3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (disambiguation)

* Third Avenue (disambiguation)

* Hi ...

– Sixth Dynasties)

* First Intermediate Period

The First Intermediate Period, described as a 'dark period' in ancient Egyptian history, spanned approximately 125 years, c. 2181–2055 BC, after the end of the Old Kingdom. It comprises the Seventh (although this is mostly considered spuriou ...

( Seventh or Eighth–Eleventh

In music or music theory, an eleventh is the note eleven scale degrees from the root of a chord and also the interval between the root and the eleventh. The interval can be also described as a compound fourth, spanning an octave plus a f ...

Dynasties)

* Middle Kingdom ( Twelfth–Thirteenth

In music or music theory, a thirteenth is the note thirteen scale degrees from the root of a chord and also the interval between the root and the thirteenth. The interval can be also described as a compound sixth, spanning an octave pl ...

Dynasties)

* Second Intermediate Period

The Second Intermediate Period marks a period when ancient Egypt fell into disarray for a second time, between the end of the Middle Kingdom and the start of the New Kingdom. The concept of a "Second Intermediate Period" was coined in 1942 by ...

( Fourteenth– Seventeenth Dynasties)

* New Kingdom

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator ...

( Eighteenth–Twentieth

20 (twenty; Roman numeral XX) is the natural number following 19 and preceding 21. A group of twenty units may also be referred to as a score.

In mathematics

*20 is a pronic number.

*20 is a tetrahedral number as 1, 4, 10, 20.

*20 is the ...

Dynasties)

* Third Intermediate Period

The Third Intermediate Period of ancient Egypt began with the death of Pharaoh Ramesses XI in 1077 BC, which ended the New Kingdom, and was eventually followed by the Late Period. Various points are offered as the beginning for the latt ...

(also known as the Libyan Period; Twenty-first– Twenty-fifth Dynasties)

* Late Period ( Twenty-sixth– Thirty-first Dynasties)

* Ptolemaic Egypt (305–30 BC)

Neolithic Egypt

Neolithic period

TheNile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

has been the lifeline for Egyptian culture since nomadic hunter-gatherers began living along it during the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the '' Ice age'') is the geological epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was finally confirmed ...

. Traces of these early people appear in the form of artefacts and rock carvings along the terraces of the Nile and in the oases.

Along the Nile in the 12th millennium BC, an Upper Paleolithic

The Upper Paleolithic (or Upper Palaeolithic) is the third and last subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. Very broadly, it dates to between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago (the beginning of the Holocene), according to some theories coi ...

grain-grinding culture using the earliest type of sickle blades had replaced the culture of hunting

Hunting is the human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, or killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to harvest food (i.e. meat) and useful animal products ( fur/ hide, bone/ tusks, horn/ a ...

, fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch fish. Fish are often caught as wildlife from the natural environment, but may also be caught from stocked bodies of water such as ponds, canals, park wetlands and reservoirs. Fishing techniques ...

, and hunter-gatherers using stone tool

A stone tool is, in the most general sense, any tool made either partially or entirely out of stone. Although stone tool-dependent societies and cultures still exist today, most stone tools are associated with prehistoric (particularly Stone Ag ...

s. Evidence also indicates human habitation and cattle herding in the southwestern corner of Egypt near the Sudan border before the 8th millennium BC

8 (eight) is the natural number following 7 and preceding 9.

In mathematics

8 is:

* a composite number, its proper divisors being , , and . It is twice 4 or four times 2.

* a power of two, being 2 (two cubed), and is the first number of t ...

.

Despite this, the idea of an independent bovine domestication event in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

must be abandoned because subsequent evidence gathered over a period of thirty years has failed to corroborate this.

Archaeological evidence has attested that population settlements occurred in Nubia as early as the Late Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the '' Ice age'') is the geological epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was finally confirmed ...

era and from the 5th millennium BC onwards, whereas there is "no or scanty evidence" of human presence in the Egyptian Nile Valley during these periods, which may be due to problems in site preservation.

The oldest-known domesticated cattle remains in Africa are from the Faiyum

Faiyum ( ar, الفيوم ' , borrowed from cop, ̀Ⲫⲓⲟⲙ or Ⲫⲓⲱⲙ ' from egy, pꜣ ym "the Sea, Lake") is a city in Middle Egypt. Located southwest of Cairo, in the Faiyum Oasis, it is the capital of the modern Faiyu ...

c. 4400 BC. Geological evidence and computer climate modeling studies suggest that natural climate changes around the 8th millennium BC began to desiccate the extensive pastoral lands of North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in t ...

, eventually forming the Sahara

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

by the 25th century BC.

Continued desiccation forced the early ancestors of the Egyptians to settle around the Nile more permanently and forced them to adopt a more sedentary lifestyle. However, the period from 9th

9 (nine) is the natural number following and preceding .

Evolution of the Arabic digit

In the beginning, various Indians wrote a digit 9 similar in shape to the modern closing question mark without the bottom dot. The Kshatrapa, Andhra and ...

to the 6th millennium BC

The 6th millennium BC spanned the years 6000 BC to 5001 BC (c. 8 ka to c. 7 ka). It is impossible to precisely date events that happened around the time of this millennium and all dates mentioned here are estimates mostly based on geological an ...

has left very little in the way of archaeological evidence.

Prehistoric Egypt

The Nile valley of Egypt was basically uninhabitable until the work of clearing and irrigating the land along the banks was started. However, it appears that this clearance and irrigation was largely under way by the

The Nile valley of Egypt was basically uninhabitable until the work of clearing and irrigating the land along the banks was started. However, it appears that this clearance and irrigation was largely under way by the 6th millennium

While the future cannot be predicted with certainty, present understanding in various scientific fields allows for the prediction of some far-future events, if only in the broadest outline. These fields include astrophysics, which studies ho ...

. By that time, Nile society was already engaged in organized agriculture and the construction of large buildings.Redford, Donald B. ''Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times.'' (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 6.

At this time, Egyptians in the southwestern corner of Egypt were herding cattle and also constructing large buildings. Mortar was in use by the 4th millennium. The people of the valley and the Nile Delta

The Nile Delta ( ar, دلتا النيل, or simply , is the delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's largest river deltas—from Alexandria in the west to ...

were self-sufficient and were raising barley

Barley (''Hordeum vulgare''), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains, particularly in Eurasia as early as 10,000 years ago. Globally 70% of barley ...

and emmer

Emmer wheat or hulled wheat is a type of awned wheat. Emmer is a tetraploid (4''n'' = 4''x'' = 28 chromosomes). The domesticated types are ''Triticum turgidum'' subsp. ''dicoccum'' and ''Triticum turgidum ''conv.'' durum''. The wild plant is ...

, an early variety of wheat, and stored it in pits lined with reed mats.Carl Roebuck, ''The World of Ancient Times'', p. 52. They raised cattle, goat

The goat or domestic goat (''Capra hircus'') is a domesticated species of goat-antelope typically kept as livestock. It was domesticated from the wild goat (''C. aegagrus'') of Southwest Asia and Eastern Europe. The goat is a member of ...

s and pig

The pig (''Sus domesticus''), often called swine, hog, or domestic pig when distinguishing from other members of the genus ''Sus'', is an omnivorous, domesticated, even-toed, hoofed mammal. It is variously considered a subspecies of ''Sus ...

s and they wove linen

Linen () is a textile made from the fibers of the flax plant.

Linen is very strong, absorbent, and dries faster than cotton. Because of these properties, linen is comfortable to wear in hot weather and is valued for use in garments. It also ...

and baskets. Prehistory continues through this time, variously held to begin with the Amratian culture

The Amratian culture, also called Naqada I, was an archaeological culture of prehistoric Upper Egypt. It lasted approximately from 4000 to 3500 BC.

Overview

The Amratian culture is named after the archaeological site of el-Amra, located around ...

.

Between 5500 BC and the 31st century BC

The 31st century BC was a century that lasted from the year 3100 BC to 3001 BC.

Events

*c. 3100 BC: Polo ( mni, Sagol Kangjei) was first played in Manipur state.

*c. 3100 BC?: The Anu Ziggurat and White Temple are built in Uruk.

*c. 3100 BC?: ...

, small settlements flourished along the Nile, whose delta empties into the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

.

The Tasian culture

The Tasian culture is possibly one of the oldest-known Predynastic culture in Upper Egypt, which evolved around 4500 BC. It is named for the burials found at Deir Tasa, a site on the east bank of the Nile located between Asyut and Akhmim. The ...

was the next to appear; it existed in Upper Egypt starting about 4500 BC. This group is named for the burials found at Deir Tasa, a site on the east bank of the Nile between Asyut

AsyutAlso spelled ''Assiout'' or ''Assiut'' ( ar, أسيوط ' , from ' ) is the capital of the modern Asyut Governorate in Egypt. It was built close to the ancient city of the same name, which is situated nearby. The modern city is located at ...

and Akhmim

Akhmim ( ar, أخميم, ; Akhmimic , ; Sahidic/Bohairic cop, ) is a city in the Sohag Governorate of Upper Egypt. Referred to by the ancient Greeks as Khemmis or Chemmis ( grc, Χέμμις) and Panopolis ( grc, Πανὸς πόλις and Π ...

. The Tasian culture is notable for producing the earliest blacktop-ware, a type of red and brown pottery painted black on its top and interior.Gardiner (1964), p.388

The Badari culture, named for the Badari site near Deir Tasa, followed the Tasian; however, similarities cause many to avoid differentiating between them at all. The Badari culture continued to produce the kind of pottery called blacktop-ware (although its quality was much improved over previous specimens), and was assigned the sequence dating

Sequence dating, an archaeological relative dating method, allows assemblages to be arranged in a rough serial order, which is then taken to indicate time. Sequence dating is a method of seriation developed by the Egyptologist Sir William Matthew ...

numbers between 21 and 29. The significant difference, however, between the Tasian and Badari, which prevents scholars from completely merging the two, is that Badari sites are Chalcolithic

The Copper Age, also called the Chalcolithic (; from grc-gre, χαλκός ''khalkós'', " copper" and ''líthos'', " stone") or (A)eneolithic (from Latin ''aeneus'' "of copper"), is an archaeological period characterized by regul ...

while the Tasian sites remained Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several part ...

and are thus considered technically part of the Stone Age.Gardiner (1964), p.389

The Amratian culture is named after the site of el-Amreh, about south of Badari. El-Amreh was the first site where this culture was found unmingled with the later Gerzeh culture. However, this period is better attested at Nagada

Naqada (Egyptian Arabic: ; Coptic language: ; Ancient Greek: ) is a town on the west bank of the Nile in Qena Governorate, Egypt, situated ca. 20 km north of Luxor. It includes the villages of Tukh, Khatara, Danfiq, and Zawayda. Accordi ...

, and so is also referred to as the "Naqada I" culture.Grimal (1988) p.24 Black-topped ware continued to be produced, but white cross-line ware, a type of pottery decorated with close parallel white lines crossed by another set of close parallel white lines, began to be produced during this time. The Amratian period falls between S.D. 30 and 39.Gardiner (1964), 390. Newly excavated objects indicate that trade between Upper and Lower Egypt existed at this time. A stone vase from the north was found at el-Amreh, and copper, which is not present in Egypt, was apparently imported from the Sinai Peninsula

The Sinai Peninsula, or simply Sinai (now usually ) (, , cop, Ⲥⲓⲛⲁ), is a peninsula in Egypt, and the only part of the country located in Asia. It is between the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Red Sea to the south, and is a ...

or perhaps Nubia

Nubia () (Nobiin language, Nobiin: Nobīn, ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the Cataracts of the Nile, first cataract of the Nile (just south of Aswan in southern Egypt) and the confluence of the Blue Nile, Blue ...

. ObsidianGrimal (1988) p.28 and an extremely small amount of gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile ...

were both definitively imported from Nubia during this time. Trade with the oases was also likely.

Naqada II

TheGerzeh culture

The Gerzeh culture, also called Naqada II, refers to the archaeological stage at Gerzeh (also Girza or Jirzah), a prehistoric Egyptian cemetery located along the west bank of the Nile. The necropolis is named after el-Girzeh, the nearby contem ...

("Naqada II"), named after the site of el-Gerzeh, was the next stage in cultural development, and it was during this time that the foundation for ancient Egypt was laid. The Gerzeh culture was largely an unbroken development out of the Amratian, starting in the Nile Delta

The Nile Delta ( ar, دلتا النيل, or simply , is the delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's largest river deltas—from Alexandria in the west to ...

and moving south through Upper Egypt

Upper Egypt ( ar, صعيد مصر ', shortened to , , locally: ; ) is the southern portion of Egypt and is composed of the lands on both sides of the Nile that extend wikt:downriver, upriver from Lower Egypt in the north to Nubia in the south. ...

; however, it failed to dislodge the Amratian in Nubia

Nubia () (Nobiin language, Nobiin: Nobīn, ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the Cataracts of the Nile, first cataract of the Nile (just south of Aswan in southern Egypt) and the confluence of the Blue Nile, Blue ...

.Redford, Donald B. ''Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times.'' (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 16. The Gerzeh culture coincided with a significant drop in rainfall and farming produced the vast majority of food. With increased food supplies, the populace adopted a much more sedentary lifestyle, and the larger settlements grew to cities of about 5000 residents. It was in this time that the city dwellers started using adobe

Adobe ( ; ) is a building material made from earth and organic materials. is Spanish for '' mudbrick''. In some English-speaking regions of Spanish heritage, such as the Southwestern United States, the term is used to refer to any kind of ...

to build their cities. Copper instead of stone was increasingly used to make tools and weaponry. Silver

Silver is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/h₂erǵ-, ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, whi ...

, gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile ...

, lapis lazuli

Lapis lazuli (; ), or lapis for short, is a deep-blue metamorphic rock used as a semi-precious stone that has been prized since antiquity for its intense color.

As early as the 7th millennium BC, lapis lazuli was mined in the Sar-i Sang mine ...

(imported from Badakhshan

Badakhshan is a historical region comprising parts of modern-day north-eastern Afghanistan, eastern Tajikistan, and Taxkorgan Tajik Autonomous County in China. Badakhshan Province is one of the 34 provinces of Afghanistan. Much of historic ...

in what is now Afghanistan), and Egyptian faience

Egyptian faience is a sintered-quartz ceramic material from Ancient Egypt. The sintering process "covered he materialwith a true vitreous coating" as the quartz underwent vitrification, creating a bright lustre of various colours "usually in ...

were used ornamentally,Redford, Donald B. ''Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times.'' (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 17. and the cosmetic palette

Cosmetic palettes are archaeological artifacts, originally used in predynastic Egypt to grind and apply ingredients for facial or body cosmetics. The decorative palettes of the late 4th millennium BCE appear to have lost this function and became ...

s used for eye paint since the Badari culture began to be adorned with relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term '' relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that th ...

s.Gardiner (1694), p.391

By the 33rd century BC, just before the First Dynasty of Egypt

The First Dynasty of ancient Egypt (Dynasty I) covers the first series of Egyptian kings to rule over a unified Egypt. It immediately follows the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, possibly by Narmer, and marks the beginning of the Early Dy ...

, Egypt was divided into two kingdoms known from later times as Upper Egypt

Upper Egypt ( ar, صعيد مصر ', shortened to , , locally: ; ) is the southern portion of Egypt and is composed of the lands on both sides of the Nile that extend wikt:downriver, upriver from Lower Egypt in the north to Nubia in the south. ...

to the south and Lower Egypt

Lower Egypt ( ar, مصر السفلى '; ) is the northernmost region of Egypt, which consists of the fertile Nile Delta between Upper Egypt and the Mediterranean Sea, from El Aiyat, south of modern-day Cairo, and Dahshur. Historically ...

to the north.Adkins, L. and Adkins, R. (2001) ''The Little Book of Egyptian Hieroglyphics'', p155. London: Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN . The dividing line was drawn roughly in the area of modern Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo met ...

.

Dynastic Egypt

Early dynastic period

The historical records of ancient Egypt begin with Egypt as a unified state, which occurred sometime around

The historical records of ancient Egypt begin with Egypt as a unified state, which occurred sometime around 3150 BC

The 32nd century BC was a century that lasted from the year 3200 BC to 3101 BC.

Events

* c. 3190–3170 BC? reign of King Double Falcon of Lower Egypt. There is a strong possibility that he appears on the Palermo stone, although half his name i ...

. According to Egyptian tradition, Menes

Menes (fl. c. 3200–3000 BC; ; egy, mnj, probably pronounced *; grc, Μήνης) was a pharaoh of the Early Dynastic Period of ancient Egypt credited by classical tradition with having united Upper and Lower Egypt and as the founder of the ...

, thought to have unified Upper and Lower Egypt, was the first king. This Egyptian culture, customs, art expression, architecture, and social structure were closely tied to religion, remarkably stable, and changed little over a period of nearly 3000 years.

Egyptian chronology

The majority of Egyptologists agree on the outline and many details of the chronology of Ancient Egypt. This scholarly consensus is the so-called Conventional Egyptian chronology, which places the beginning of the Old Kingdom in the 27th centu ...

, which involves regnal year

A regnal year is a year of the reign of a sovereign, from the Latin ''regnum'' meaning kingdom, rule. Regnal years considered the date as an ordinal, not a cardinal number. For example, a monarch could have a first year of rule, a second year o ...

s, began around this time. The conventional chronology was accepted during the twentieth century, but it does not include any of the major revision proposals that also have been made in that time. Even within a single work, archaeologists often offer several possible dates, or even several whole chronologies as possibilities. Consequently, there may be discrepancies between dates shown here and in articles on particular rulers or topics related to ancient Egypt. There also are several possible spellings of the names. Typically, Egyptologists divide the history of pharaonic civilization using a schedule laid out first by Manetho

Manetho (; grc-koi, Μανέθων ''Manéthōn'', ''gen''.: Μανέθωνος) is believed to have been an Egyptian priest from Sebennytos ( cop, Ϫⲉⲙⲛⲟⲩϯ, translit=Čemnouti) who lived in the Ptolemaic Kingdom in the early third ...

's ''Aegyptiaca'', which was written during the Ptolemaic Kingdom in the third century BC.

Prior to the unification of Egypt, the land was settled with autonomous villages. With the early dynasties, and for much of Egypt's history thereafter, the country came to be known as the Two Lands. The pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until th ...

s established a national administration and appointed royal governors.

According to Manetho, the first pharaoh was Menes

Menes (fl. c. 3200–3000 BC; ; egy, mnj, probably pronounced *; grc, Μήνης) was a pharaoh of the Early Dynastic Period of ancient Egypt credited by classical tradition with having united Upper and Lower Egypt and as the founder of the ...

, but archeological findings support the view that the first ruler to claim to have united the two lands was Narmer

Narmer ( egy, Wiktionary:nꜥr-mr, nꜥr-mr, meaning "painful catfish," "stinging catfish," "harsh catfish," or "fierce catfish;" ) was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the Early Dynastic Period (Egypt), Early Dynastic Period. He was the successor ...

, the final king of the Naqada III

Naqada III is the last phase of the Naqada culture of ancient Egyptian prehistory, dating from approximately 3200 to 3000 BC. It is the period during which the process of state formation, which began in Naqada II, became highly visible, ...

period. His name is known primarily from the famous Narmer Palette

The Narmer Palette, also known as the Great Hierakonpolis Palette or the Palette of Narmer, is a significant Egyptian archeological find, dating from about the 31st century BC, belonging, at least nominally, to the category of cosmetic palettes. ...

, whose scenes have been interpreted as the act of uniting Upper and Lower Egypt. Menes is now thought to be one of the titles of Hor-Aha

Hor-Aha (or Aha or Horus Aha) is considered the second pharaoh of the First Dynasty of Egypt by some Egyptologists, while others consider him the first one and corresponding to Menes. He lived around the 31st century BC and is thought to hav ...

, the second pharaoh of the First Dynasty.

Funeral practices for the elite resulted in the construction of mastaba

A mastaba (, or ), also mastabah, mastabat or pr- djt (meaning "house of stability", " house of eternity" or "eternal house" in Ancient Egyptian), is a type of ancient Egyptian tomb in the form of a flat-roofed, rectangular structure with inwa ...

s, which later became models for subsequent Old Kingdom

In ancient Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom is the period spanning c. 2700–2200 BC. It is also known as the "Age of the Pyramids" or the "Age of the Pyramid Builders", as it encompasses the reigns of the great pyramid-builders of the Fourt ...

constructions such as the step pyramid

A step pyramid or stepped pyramid is an architectural structure that uses flat platforms, or steps, receding from the ground up, to achieve a completed shape similar to a geometric pyramid. Step pyramids are structures which characterized several ...

, thought to have originated during the Third Dynasty of Egypt

The Third Dynasty of ancient Egypt (Dynasty III) is the first dynasty of the Old Kingdom. Other dynasties of the Old Kingdom include the Fourth, Fifth and Sixth. The capital during the period of the Old Kingdom was at Memphis.

Overview

A ...

.

Old Kingdom

The Old Kingdom is most commonly regarded as spanning the period of time when Egypt was ruled by the

The Old Kingdom is most commonly regarded as spanning the period of time when Egypt was ruled by the Third Dynasty

The Third Dynasty of ancient Egypt (Dynasty III) is the first dynasty of the Old Kingdom. Other dynasties of the Old Kingdom include the Fourth, Fifth and Sixth. The capital during the period of the Old Kingdom was at Memphis.

Overview

Af ...

through to the Sixth Dynasty

The Sixth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (notated Dynasty VI), along with the Third, Fourth and Fifth Dynasty, constitutes the Old Kingdom of Dynastic Egypt.

Pharaohs

Known pharaohs of the Sixth Dynasty are listed in the table below. Manetho acc ...

(2686–2181 BCE). The royal capital of Egypt during this period was located at Memphis, where Djoser

Djoser (also read as Djeser and Zoser) was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the 3rd Dynasty during the Old Kingdom, and was the founder of that epoch. He is also known by his Hellenized names Tosorthros (from Manetho) and Sesorthos (from Euseb ...

(2630–2611 BCE) established his court.

The Old Kingdom is perhaps best known, however, for the large number of pyramid

A pyramid (from el, πυραμίς ') is a structure whose outer surfaces are triangular and converge to a single step at the top, making the shape roughly a pyramid in the geometric sense. The base of a pyramid can be trilateral, quadrila ...

s, which were constructed at this time as pharaonic burial places. For this reason, this epoch is frequently referred to as "the Age of the Pyramids." The first notable pharaoh of the Old Kingdom was Djoser of the Third Dynasty, who ordered the construction of the first pyramid, the Pyramid of Djoser

The pyramid of Djoser (or Djeser and Zoser), sometimes called the Step Pyramid of Djoser, is an archaeological site in the Saqqara necropolis, Egypt, northwest of the ruins of Memphis. The 6-tier, 4-sided structure is the earliest colossal stone ...

, in Memphis' necropolis of Saqqara

Saqqara ( ar, سقارة, ), also spelled Sakkara or Saccara in English , is an Egyptian village in Giza Governorate, that contains ancient burial grounds of Egyptian royalty, serving as the necropolis for the ancient Egyptian capital, Memphi ...

.

It was in this era that formerly independent states became nomes (districts) ruled solely by the pharaoh. Former local rulers were forced to assume the role of nomarch

A nomarch ( grc, νομάρχης, egy, ḥrj tp ꜥꜣ Great Chief) was a provincial governor in ancient Egypt; the country was divided into 42 provinces, called nomes (singular , plural ). A nomarch was the government official responsib ...

(governor) or work as tax collector

A tax collector (also called a taxman) is a person who collects unpaid taxes from other people or corporations. The term could also be applied to those who audit tax returns. Tax collectors are often portrayed as being evil, and in the modern ...

s. Egyptians in this era worshiped the pharaoh as a god, believing that he ensured the annual flooding of the Nile that was necessary for their crops.

The Old Kingdom and its royal power reached their zenith under the Fourth Dynasty. Sneferu

Sneferu ( snfr-wj "He has perfected me", from ''Ḥr-nb-mꜣꜥt-snfr-wj'' "Horus, Lord of Maat, has perfected me", also read Snefru or Snofru), well known under his Hellenized name Soris ( grc-koi, Σῶρις by Manetho), was the founding pha ...

, the dynasty's founder, is believed to have commissioned at least three pyramids; while his son and successor Khufu

Khufu or Cheops was an ancient Egyptian monarch who was the second pharaoh of the Fourth Dynasty, in the first half of the Old Kingdom period (26th century BC). Khufu succeeded his father Sneferu as king. He is generally accepted as having c ...

(Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

''Cheops'') erected the Great Pyramid of Giza

The Great Pyramid of Giza is the biggest Egyptian pyramid and the tomb of Fourth Dynasty pharaoh Khufu. Built in the early 26th century BC during a period of around 27 years, the pyramid is the oldest of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient Wor ...

, Sneferu had more stone and brick moved than any other pharaoh. Khufu, his son Khafre

Khafre (also read as Khafra and gr, Χεφρήν Khephren or Chephren) was an ancient Egyptian King (pharaoh) of the 4th Dynasty during the Old Kingdom. He was the son of Khufu and the successor of Djedefre. According to the ancient histori ...

(Greek ''Chephren''), and his grandson Menkaure

Menkaure (also Menkaura, Egyptian transliteration ''mn-k3w-Rˁ''), was an ancient Egyptian king (pharaoh) of the fourth dynasty during the Old Kingdom, who is well known under his Hellenized names Mykerinos ( gr, Μυκερῖνος) (by Her ...

(Greek ''Mycerinus'') all achieved lasting fame in the construction of the Giza pyramid complex

The Giza pyramid complex ( ar, مجمع أهرامات الجيزة), also called the Giza necropolis, is the site on the Giza Plateau in Greater Cairo, Egypt that includes the Great Pyramid of Giza, the Pyramid of Khafre, and the Pyramid of ...

.

To organize and feed the manpower needed to create these pyramids required a centralized government with extensive powers, and Egyptologists believe the Old Kingdom at this time demonstrated this level of sophistication. Recent excavations near the pyramids led by Mark Lehner have uncovered a large city that seems to have housed, fed and supplied the pyramid workers. Although it was once believed that slaves built these monuments, a theory based on The Exodus

The Exodus (Hebrew: יציאת מצרים, ''Yeẓi’at Miẓrayim'': ) is the founding myth of the Israelites whose narrative is spread over four books of the Torah (or Pentateuch, corresponding to the first five books of the Bible), namely E ...

narrative of the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

, study of the tombs of the workmen, who oversaw construction on the pyramids, has shown they were built by a ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

corvée

Corvée () is a form of unpaid, forced labour, that is intermittent in nature lasting for limited periods of time: typically for only a certain number of days' work each year.

Statute labour is a corvée imposed by a state for the purposes of ...

of peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasan ...

s drawn from across Egypt. They apparently worked while the annual flood covered their fields, as well as a very large crew of specialists, including stonecutters, painters, mathematicians and priests.

The Fifth Dynasty

The Fifth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (notated Dynasty V) is often combined with Dynasties Third Dynasty of Egypt, III, Fourth Dynasty of Egypt, IV and Sixth Dynasty of Egypt, VI under the group title the Old Kingdom of Egypt, Old Kingdom. The Fifth ...

began with Userkaf

Userkaf (known in Ancient Greek as , ) was a pharaoh of ancient Egypt and the founder of the Fifth Dynasty. He reigned for seven to eight years in the early 25th century BC, during the Old Kingdom period. He probably belonged to a branch of the ...

c. 2495 BC and was marked by the growing importance of the cult of the sun god Ra. Consequently, less effort was devoted to the construction of pyramid complexes than during the Fourth Dynasty and more to the construction of sun temples in Abusir

Abusir ( ar, ابو صير ; Egyptian ''pr wsjr'' cop, ⲃⲟⲩⲥⲓⲣⲓ ' "the House or Temple of Osiris"; grc, Βούσιρις) is the name given to an Egyptian archaeological locality – specifically, an extensive necropolis of ...

. The decoration of pyramid complexes grew more elaborate during the dynasty and its last king, Unas

Unas or Wenis, also spelled Unis ( egy, wnjs, hellenized form Oenas or Onnos), was a pharaoh, the ninth and last ruler of the Fifth Dynasty of Egypt during the Old Kingdom. Unas reigned for 15 to 30 years in the mid-24th century BC (circa 2 ...

, was the first to have the Pyramid Texts

The Pyramid Texts are the oldest ancient Egyptian funerary texts, dating to the late Old Kingdom. They are the earliest known corpus of ancient Egyptian religious texts. Written in Old Egyptian, the pyramid texts were carved onto the subterranea ...

inscribed in his pyramid.

Egypt's expanding interests in trade goods such as ebony

Ebony is a dense black/brown hardwood, coming from several species in the genus '' Diospyros'', which also contains the persimmons. Unlike most woods, ebony is dense enough to sink in water. It is finely textured and has a mirror finish when ...

, incense such as myrrh

Myrrh (; from Semitic, but see '' § Etymology'') is a gum-resin extracted from a number of small, thorny tree species of the genus '' Commiphora''. Myrrh resin has been used throughout history as a perfume, incense and medicine. Myrrh mix ...

and frankincense, gold, copper and other useful metals compelled the ancient Egyptians to navigate the open seas. Evidence from the pyramid of Sahure

The pyramid of Sahure () is a pyramid complex built in the late 26th to 25th century BC for the Egyptian pharaoh Sahure of the Fifth Dynasty. It introduced a period of pyramid building by Sahure's successors in Abusir, on a location earlier use ...

, second king of the dynasty, shows that a regular trade existed with the Syrian coast to procure cedar wood

Cedar is part of the English common name of many trees and other plants, particularly those of the genus '' Cedrus''.

Some botanical authorities consider the Old-World ''Cedrus'' the only "true cedars". Many other species worldwide with similar ...

. Pharaohs also launched expeditions to the famed Land of Punt

The Land of Punt ( Egyptian: ''pwnt''; alternate Egyptological readings ''Pwene''(''t'') /pu:nt/) was an ancient kingdom known from Ancient Egyptian trade records. It produced and exported gold, aromatic resins, blackwood, ebony, ivory ...

, possibly the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

, for ebony, ivory and aromatic resins.

During the Sixth Dynasty

The Sixth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (notated Dynasty VI), along with the Third, Fourth and Fifth Dynasty, constitutes the Old Kingdom of Dynastic Egypt.

Pharaohs

Known pharaohs of the Sixth Dynasty are listed in the table below. Manetho acc ...

(2345–2181 BCE), the power of pharaohs gradually weakened in favor of powerful nomarch

A nomarch ( grc, νομάρχης, egy, ḥrj tp ꜥꜣ Great Chief) was a provincial governor in ancient Egypt; the country was divided into 42 provinces, called nomes (singular , plural ). A nomarch was the government official responsib ...

s. These no longer belonged to the royal family and their charge became hereditary, thus creating local dynasties largely independent from the central authority of the pharaoh. Internal disorders set in during the incredibly long reign of Pepi II Neferkare

Pepi II Neferkare (2284 BC – after 2247 BC, probably either 2216 or 2184 BC) was a pharaoh of the Sixth Dynasty in Egypt's Old Kingdom who reigned from 2278 BC. His second name, Neferkare (''Nefer-ka-Re''), means "Beautiful i ...

(2278–2184 BCE) towards the end of the dynasty. His death, certainly well past that of his intended heirs, might have created succession struggles and the country slipped into civil wars mere decades after the close of Pepi II

Pepi II Neferkare (2284 BC – after 2247 BC, probably either 2216 or 2184 BC) was a pharaoh of the Sixth Dynasty in Egypt's Old Kingdom who reigned from 2278 BC. His second name, Neferkare (''Nefer-ka-Re''), means "Beautiful i ...

's reign. The final blow came when the 4.2 kiloyear event

The 4.2-kiloyear (thousand years) BP aridification event (long-term drought) was one of the most severe climatic events of the Holocene epoch. It defines the beginning of the current Meghalayan age in the Holocene epoch.

Starting around 220 ...

struck the region in the 22nd century BC, producing consistently low Nile flood levels. The result was the collapse of the Old Kingdom followed by decades of famine and strife.

First Intermediate Period

After the fall of the Old Kingdom came a roughly 200-year stretch of time known as the First Intermediate Period, which is generally thought to include a relatively obscure set of pharaohs running from the end of the Sixth to the Tenth and most of the

After the fall of the Old Kingdom came a roughly 200-year stretch of time known as the First Intermediate Period, which is generally thought to include a relatively obscure set of pharaohs running from the end of the Sixth to the Tenth and most of the Eleventh

In music or music theory, an eleventh is the note eleven scale degrees from the root of a chord and also the interval between the root and the eleventh. The interval can be also described as a compound fourth, spanning an octave plus a f ...

Dynasties. Most of these were likely local monarchs who did not hold much power outside of their nome. There are a number of texts known as "Lamentations" from the early period of the subsequent Middle Kingdom that may shed some light on what happened during this period. Some of these texts reflect on the breakdown of rule, others allude to invasion by "Asiatic bowmen". In general, the stories focus on a society where the natural order of things in both society and nature was overthrown.

It is also highly likely that it was during this period that all of the pyramid and tomb complexes were looted. Further lamentation texts allude to this fact, and by the beginning of the Middle Kingdom mummies

A mummy is a dead human or an animal whose soft tissues and organs have been preserved by either intentional or accidental exposure to chemicals, extreme cold, very low humidity, or lack of air, so that the recovered body does not decay fur ...

are found decorated with magical spells that were once exclusive to the pyramid of the kings of the Sixth Dynasty.

By 2160 BC, a new line of pharaohs, the Ninth

In music, a ninth is a compound interval consisting of an octave plus a second.

Like the second, the interval of a ninth is classified as a dissonance in common practice tonality. Since a ninth is an octave larger than a second, ...

and Tenth Dynasties, consolidated Lower Egypt

Lower Egypt ( ar, مصر السفلى '; ) is the northernmost region of Egypt, which consists of the fertile Nile Delta between Upper Egypt and the Mediterranean Sea, from El Aiyat, south of modern-day Cairo, and Dahshur. Historically ...

from their capital in Heracleopolis Magna

Heracleopolis Magna ( grc-gre, Μεγάλη Ἡρακλέους πόλις, ''Megálē Herakléous pólis'') and Heracleopolis (, ''Herakleópolis'') and Herakleoupolis (), is the Roman name of the capital of the 20th nome of ancient Upper ...

. A rival line, the Eleventh Dynasty

The Eleventh Dynasty of ancient Egypt (notated Dynasty XI) is a well-attested group of rulers. Its earlier members before Pharaoh Mentuhotep II are grouped with the four preceding dynasties to form the First Intermediate Period, whereas the late ...

based at Thebes, reunited Upper Egypt

Upper Egypt ( ar, صعيد مصر ', shortened to , , locally: ; ) is the southern portion of Egypt and is composed of the lands on both sides of the Nile that extend wikt:downriver, upriver from Lower Egypt in the north to Nubia in the south. ...

, and a clash between the rival dynasties was inevitable. Around 2055 BC

The 21st century BC was a century that lasted from the year 2100 BC to 2001 BC.

Events

Note: all dates from this long ago should be regarded as either approximate or conjectural; there are no absolutely certain dates, and multiple competing re ...

, the Theban forces defeated the Heracleopolitan pharaohs and reunited the Two Lands. The reign of its first pharaoh, Mentuhotep II

Mentuhotep II ( egy, Mn- ṯw- ḥtp, meaning "Mentu is satisfied"), also known under his prenomen Nebhepetre ( egy, Nb- ḥpt- Rˁ, meaning "The Lord of the rudder is Ra"), was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh, the sixth ruler of the Eleventh D ...

, marks the beginning of the Middle Kingdom.

Middle Kingdom

The Middle Kingdom is the period in the history of ancient Egypt stretching from the 39th regnal year of Mentuhotep II of the

The Middle Kingdom is the period in the history of ancient Egypt stretching from the 39th regnal year of Mentuhotep II of the Eleventh Dynasty

The Eleventh Dynasty of ancient Egypt (notated Dynasty XI) is a well-attested group of rulers. Its earlier members before Pharaoh Mentuhotep II are grouped with the four preceding dynasties to form the First Intermediate Period, whereas the late ...

to the end of the Thirteenth Dynasty, roughly between 2030 and 1650 BC. The period comprises two phases, the Eleventh Dynasty, which ruled from Thebes, and then the Twelfth Dynasty

The Twelfth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (Dynasty XII) is considered to be the apex of the Middle Kingdom by Egyptologists. It often is combined with the Eleventh, Thirteenth, and Fourteenth dynasties under the group title, Middle Kingdom. Some s ...

, whose capital was Lisht. These two dynasties were originally considered the full extent of this unified kingdom, but some historians now consider the first part of the Thirteenth Dynasty to belong to the Middle Kingdom.

The earliest pharaohs of the Middle Kingdom traced their origin to two nomarchs of Thebes, Intef the Elder

Intef, whose name is commonly accompanied by epithets such as the Elder, the Great (= ''Intef-aa'') or born of Iku, was a Theban nomarch during the First Intermediate Period c. 2150 BC and later considered a founding figure of the 11th Dynasty, wh ...

, who served a Heracleopolitan pharaoh of the Tenth Dynasty, and his successor, Mentuhotep I Mentuhotep (also Montuhotep) is an ancient Egyptian name meaning "''Montu is satisfied''" and may refer to:

Kings

* Mentuhotep I, nomarch at Thebes during the First Intermediate Period and first king of the 11th Dynasty

* Mentuhotep II, reunifi ...

. The successor of the latter, Intef I

Sehertawy Intef I was a local nomarch at Thebes during the early First Intermediate Period and the first member of the 11th Dynasty to lay claim to a Horus name. Intef reigned from 4 to 16 years c. 2120 BC or c. 2070 BC during which time he prob ...

, was the first Theban nomarch to claim a Horus name

The Horus name is the oldest known and used crest of ancient Egyptian rulers. It belongs to the " great five names" of an Egyptian pharaoh. However, modern Egyptologists and linguists are starting to prefer the more neutral term: the "serekh na ...

and thus the throne of Egypt. He is considered the first pharaoh of the Eleventh Dynasty. His claims brought the Thebans into conflict with the rulers of the Tenth Dynasty. Intef I and his brother Intef II

Wahankh Intef II (also Inyotef II and Antef II) was the third ruler of the Eleventh Dynasty of Egypt during the First Intermediate Period. He reigned for almost fifty years from 2112 BC to 2063 BC. His capital was located at Thebes. In his time, ...

undertook several campaigns northwards and finally captured the important nome of Abydos. Warfare continued intermittently between the Thebean and Heracleapolitan dynasties until the 39th regnal year

A regnal year is a year of the reign of a sovereign, from the Latin ''regnum'' meaning kingdom, rule. Regnal years considered the date as an ordinal, not a cardinal number. For example, a monarch could have a first year of rule, a second year o ...

of Mentuhotep II

Mentuhotep II ( egy, Mn- ṯw- ḥtp, meaning "Mentu is satisfied"), also known under his prenomen Nebhepetre ( egy, Nb- ḥpt- Rˁ, meaning "The Lord of the rudder is Ra"), was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh, the sixth ruler of the Eleventh D ...

, second successor of Intef II. At this point, the Herakleopolitans were defeated and the Theban dynasty consolidated their rule over Egypt. Mentuhotep II is known to have commanded military campaigns south into Nubia, which had gained its independence during the First Intermediate Period. There is also evidence for military actions against the Southern Levant

The Southern Levant is a geographical region encompassing the southern half of the Levant. It corresponds approximately to modern-day Israel, Palestine, and Jordan; some definitions also include southern Lebanon, southern Syria and/or the Sinai ...

. The king reorganized the country and placed a vizier

A vizier (; ar, وزير, wazīr; fa, وزیر, vazīr), or wazir, is a high-ranking political advisor or minister in the near east. The Abbasid caliphs gave the title ''wazir'' to a minister formerly called '' katib'' (secretary), who was ...

at the head of civil administration for the country. Mentuhotep II was succeeded by his son, Mentuhotep III

Sankhkare Mentuhotep III (also Montuhotep III) of the Eleventh Dynasty was Pharaoh of Egypt during the Middle Kingdom. He was assigned a reign of 12 years in the Turin Canon.

Reign

Mentuhotep III succeeded his father Mentuhotep II to ...

, who organized an expedition to Punt. His reign saw the realization of some of the finest Egyptian carvings. Mentuhotep III was succeeded by Mentuhotep IV

Nebtawyre Mentuhotep IV was the last king of the 11th Dynasty in the Middle Kingdom. He seems to fit into a 7-year period in the Turin Canon for which there is no recorded king.

Family King's Mother Imi

In Wadi Hammamat, a rock inscription (Ham ...

, the final pharaoh of this dynasty. Despite being absent from various lists of pharaohs, his reign is attested from a few inscriptions in Wadi Hammamat

Wadi Hammamat ( en, Valley of Many Baths, ''India way; gateway to India'') is a dry river bed in Egypt's Eastern Desert, about halfway between Al-Qusayr and Qena. It was a major mining region and trade route east from the Nile Valley in ancien ...

that record expeditions to the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

coast and to quarry stone for the royal monuments.

The leader of this expedition was his vizier Amenemhat, who is widely assumed to be the future Pharaoh Amenemhat I

:''See Amenemhat, for other individuals with this name.''

Amenemhat I ( Ancient Egyptian: ''Ỉmn-m-hꜣt'' meaning 'Amun is at the forefront'), also known as Amenemhet I, was a pharaoh of ancient Egypt and the first king of the Twelfth Dyna ...

, the first pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty

The Twelfth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (Dynasty XII) is considered to be the apex of the Middle Kingdom by Egyptologists. It often is combined with the Eleventh, Thirteenth, and Fourteenth dynasties under the group title, Middle Kingdom. Some s ...

. Amenemhat is therefore assumed by some Egyptologists to have either usurped the throne or assumed power after Mentuhotep IV died childless. Amenemhat I built a new capital for Egypt, Itjtawy, thought to be located near the present-day Lisht, although Manetho claims the capital remained at Thebes. Amenemhat forcibly pacified internal unrest, curtailed the rights of the nomarchs, and is known to have launched at least one campaign into Nubia. His son Senusret I

Senusret I ( Middle Egyptian: z-n-wsrt; /suʀ nij ˈwas.ɾiʔ/) also anglicized as Sesostris I and Senwosret I, was the second pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt. He ruled from 1971 BC to 1926 BC (1920 BC to 1875 BC), and was one of the mos ...

continued the policy of his father to recapture Nubia and other territories lost during the First Intermediate Period. The Libu

The Libu ( egy, rbw; also transcribed Rebu, Lebu, Lbou, Libou) were an Ancient Libyan tribe of Berber origin, from which the name ''Libya'' derives.

Early history

Their occupation of Ancient Libya is first attested in Egyptian language text ...

were subdued under his forty-five year reign and Egypt's prosperity and security were secured. Senusret III

Khakaure Senusret III (also written as Senwosret III or the hellenised form, Sesostris III) was a pharaoh of Egypt. He ruled from 1878 BC to 1839 BC during a time of great power and prosperity, and was the fifth king of the Twelfth Dynasty of ...

(1878–1839 BC) was a warrior king, leading his troops deep into Nubia, and built a series of massive forts throughout the country to establish Egypt's formal boundaries with the unconquered areas of its territory. Amenemhat III (1860–1815 BC) is considered the last great pharaoh of the Middle Kingdom.

Egypt's population began to exceed food production levels during the reign of Amenemhat III, who then ordered the exploitation of the Faiyum

Faiyum ( ar, الفيوم ' , borrowed from cop, ̀Ⲫⲓⲟⲙ or Ⲫⲓⲱⲙ ' from egy, pꜣ ym "the Sea, Lake") is a city in Middle Egypt. Located southwest of Cairo, in the Faiyum Oasis, it is the capital of the modern Faiyu ...

and increased mining operations in the Sinai Peninsula

The Sinai Peninsula, or simply Sinai (now usually ) (, , cop, Ⲥⲓⲛⲁ), is a peninsula in Egypt, and the only part of the country located in Asia. It is between the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Red Sea to the south, and is a ...

. He also invited settlers from Western Asia

Western Asia, West Asia, or Southwest Asia, is the westernmost subregion of the larger geographical region of Asia, as defined by some academics, UN bodies and other institutions. It is almost entirely a part of the Middle East, and includes A ...

to Egypt to labor on Egypt's monuments. Late in his reign, the annual flooding of the Nile

The flooding of the Nile has been an important natural cycle in Egypt since ancient times. It is celebrated by Egyptians as an annual holiday for two weeks starting August 15, known as ''Wafaa El-Nil''. It is also celebrated in the Coptic Church b ...

began to fail, further straining the resources of the government. The Thirteenth Dynasty and Fourteenth Dynasty

The Fourteenth Dynasty of Egypt was a series of rulers reigning during the Second Intermediate Period over the Nile Delta region of Egypt. It lasted between 75 (ca. 1725–1650 BC) and 155 years (ca. 1805–1650 BC), depending on the sc ...

witnessed the slow decline of Egypt into the Second Intermediate Period

The Second Intermediate Period marks a period when ancient Egypt fell into disarray for a second time, between the end of the Middle Kingdom and the start of the New Kingdom. The concept of a "Second Intermediate Period" was coined in 1942 by ...

, in which some of the settlers invited by Amenemhat III would seize power as the Hyksos

Hyksos (; Egyptian '' ḥqꜣ(w)- ḫꜣswt'', Egyptological pronunciation: ''hekau khasut'', "ruler(s) of foreign lands") is a term which, in modern Egyptology, designates the kings of the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt (fl. c. 1650–1550 BC). ...

.

Second Intermediate Period and the Hyksos

The Second Intermediate Period marks a period when Egypt once again fell into disarray between the end of the Middle Kingdom and the start of the

The Second Intermediate Period marks a period when Egypt once again fell into disarray between the end of the Middle Kingdom and the start of the New Kingdom

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator ...

. This period is best known as the time the Hyksos

Hyksos (; Egyptian '' ḥqꜣ(w)- ḫꜣswt'', Egyptological pronunciation: ''hekau khasut'', "ruler(s) of foreign lands") is a term which, in modern Egyptology, designates the kings of the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt (fl. c. 1650–1550 BC). ...

made their appearance in Egypt, the reigns of its kings comprising the Fifteenth Dynasty.

The Thirteenth Dynasty proved unable to hold onto the long land of Egypt, and a provincial family of Levantine descent located in the marshes of the eastern Delta at Avaris

Avaris (; Egyptian: ḥw.t wꜥr.t, sometimes ''hut-waret''; grc, Αὔαρις, Auaris; el, Άβαρις, Ávaris; ar, حوّارة, Hawwara) was the Hyksos capital of Egypt located at the modern site of Tell el-Dab'a in the northeastern ...

broke away from the central authority to form the Fourteenth Dynasty

The Fourteenth Dynasty of Egypt was a series of rulers reigning during the Second Intermediate Period over the Nile Delta region of Egypt. It lasted between 75 (ca. 1725–1650 BC) and 155 years (ca. 1805–1650 BC), depending on the sc ...

. The splintering of the land most likely happened shortly after the reigns of the powerful Thirteenth Dynasty Pharaohs Neferhotep I

Khasekhemre Neferhotep I was an Egyptian pharaoh of the mid Thirteenth Dynasty ruling in the second half of the 18th century BC K.S.B. Ryholt: ''The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period, c.1800–1550 BC'', Carst ...

and Sobekhotep IV c. 1720 BC.

While the Fourteenth Dynasty was Levantine, the Hyksos first appeared in Egypt c. 1650 BC when they took control of Avaris and rapidly moved south to Memphis, thereby ending the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Dynasties. The outlines of the traditional account of the "invasion" of the land by the Hyksos is preserved in the ''Aegyptiaca'' of Manetho, who records that during this time the Hyksos overran Egypt, led by Salitis

In the Manethonian tradition, Salitis (Greek ''Σάλιτις'', also Salatis or Saites) was the first Hyksos king, the one who subdued and ruled Lower Egypt and founded the 15th Dynasty.

Biography

Salitis is mainly known from a few passages of F ...

, the founder of the Fifteenth Dynasty. More recently, however, the idea of a simple migration, with little or no violence involved, has gained some support. Under this theory, the Egyptian rulers of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth dynasties were unable to stop these new migrants from traveling to Egypt from the Levant because their kingdoms were struggling to cope with various domestic problems, including possibly famine and plague. Be it military or peaceful, the weakened state of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Dynasty kingdoms could explain why they rapidly fell to the emerging Hyksos power.

The Hyksos princes and chieftains ruled in the eastern Delta with their local Egyptian vassals. The Fifteenth Dynasty rulers established their capital and seat of government at Memphis and their summer residence at Avaris. The Hyksos kingdom was centered in the eastern Nile Delta

The Nile Delta ( ar, دلتا النيل, or simply , is the delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's largest river deltas—from Alexandria in the west to ...

and central Egypt but relentlessly pushed south for the control of central and Upper Egypt. Around the time Memphis fell to the Hyksos, the native Egyptian ruling house in Thebes declared its independence and set itself up as the Sixteenth Dynasty. Another short lived dynasty might have done the same in central Egypt, profiting from the power vacuum created by the fall of the Thirteenth Dynasty and forming the Abydos Dynasty.Kim Ryholt

Kim Steven Bardrum Ryholt (born 19 June 1970) is a professor of Egyptology at the University of Copenhagen and a specialist on Egyptian history and literature. He is director of the research centeCanon and Identity Formation in the Earliest Lite ...

: ''The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period'', Museum Tusculanum Press, (1997) By 1600 BC, the Hyksos had successfully moved south in central Egypt, eliminating the Abydos Dynasty and directly threatening the Sixteenth Dynasty. The latter was to prove unable to resist and Thebes fell to the Hyksos for a very short period c. 1580 BC. The Hyksos rapidly withdrew to the north and Thebes regained some independence under the Seventeenth Dynasty. From then on, Hyksos relations with the south seem to have been mainly of a commercial nature, although Theban princes appear to have recognized the Hyksos rulers and may possibly have provided them with tribute

A tribute (; from Latin ''tributum'', "contribution") is wealth, often in kind, that a party gives to another as a sign of submission, allegiance or respect. Various ancient states exacted tribute from the rulers of land which the state conq ...

for a period.

The Seventeenth Dynasty was to prove the salvation of Egypt and would eventually lead the war of liberation that drove the Hyksos back into Asia. The two last kings of this dynasty were Seqenenre Tao

Seqenenre Tao (also Seqenera Djehuty-aa or Sekenenra Taa, called 'the Brave') ruled over the last of the local kingdoms of the Theban region of Egypt in the Seventeenth Dynasty during the Second Intermediate Period. He probably was the son an ...

and Kamose

Kamose was the last Pharaoh of the Theban Seventeenth Dynasty. He was possibly the son of Seqenenre Tao and Ahhotep I and the uncle of Ahmose I, founder of the Eighteenth Dynasty. His reign fell at the very end of the Second Intermediate Peri ...

. Ahmose I

Ahmose I ( egy, jꜥḥ ms(j .w), reconstructed /ʔaʕaħ'maːsjə/ ( MK), Egyptological pronunciation ''Ahmose'', sometimes written as ''Amosis'' or ''Aahmes'', meaning " Iah (the Moon) is born") was a pharaoh and founder of the Eighteen ...

completed the conquest and expulsion of the Hyksos from the Nile Delta, restored Theban rule over the whole of Egypt and successfully reasserted Egyptian power in its formerly subject territories of Nubia

Nubia () (Nobiin language, Nobiin: Nobīn, ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the Cataracts of the Nile, first cataract of the Nile (just south of Aswan in southern Egypt) and the confluence of the Blue Nile, Blue ...

and the Southern Levant.Grimal, Nicolas. ''A History of Ancient Egypt'' p. 194. Librairie Arthéme Fayard, 1988. His reign marks the beginning of the Eighteenth Dynasty and the New Kingdom

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator ...

.

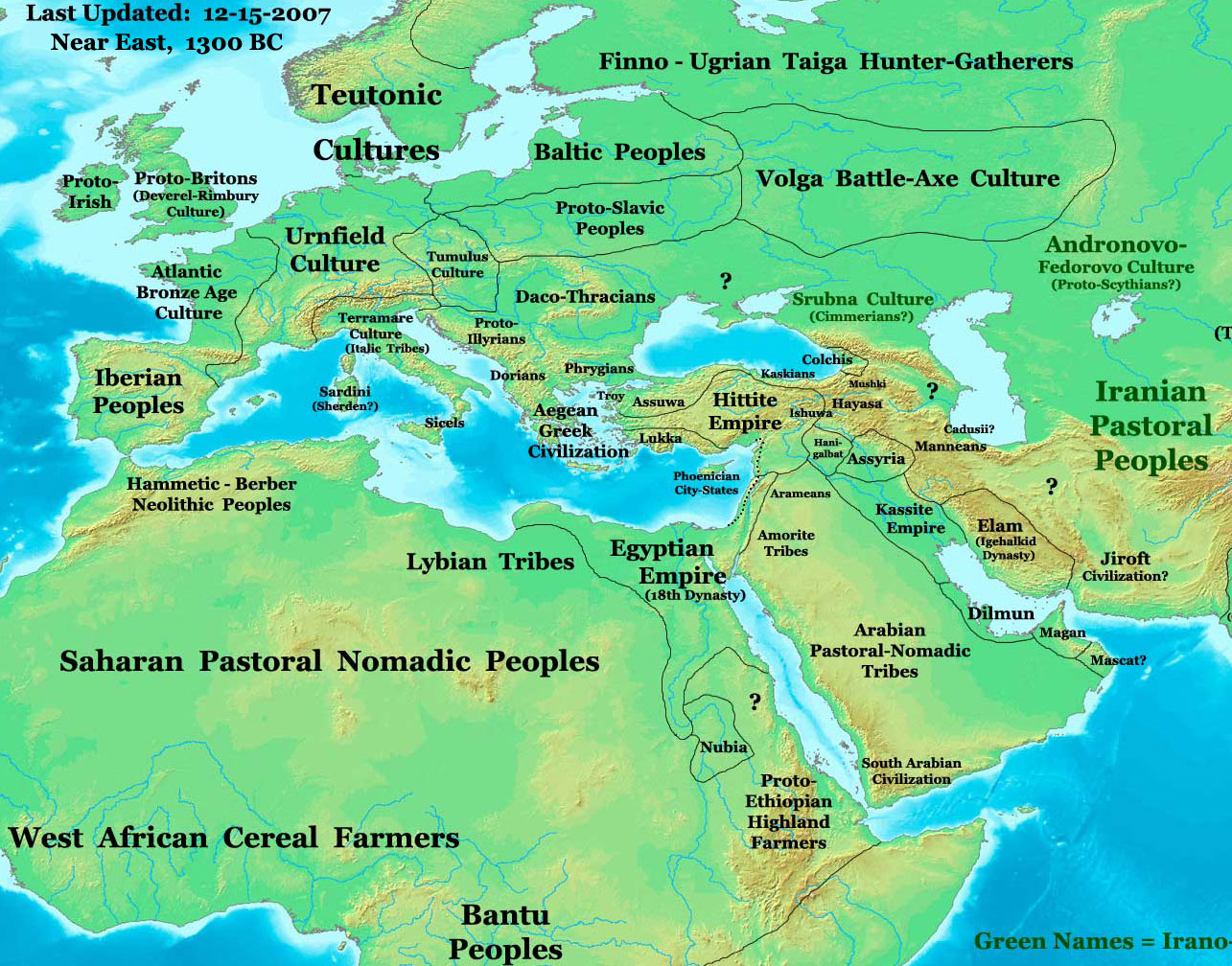

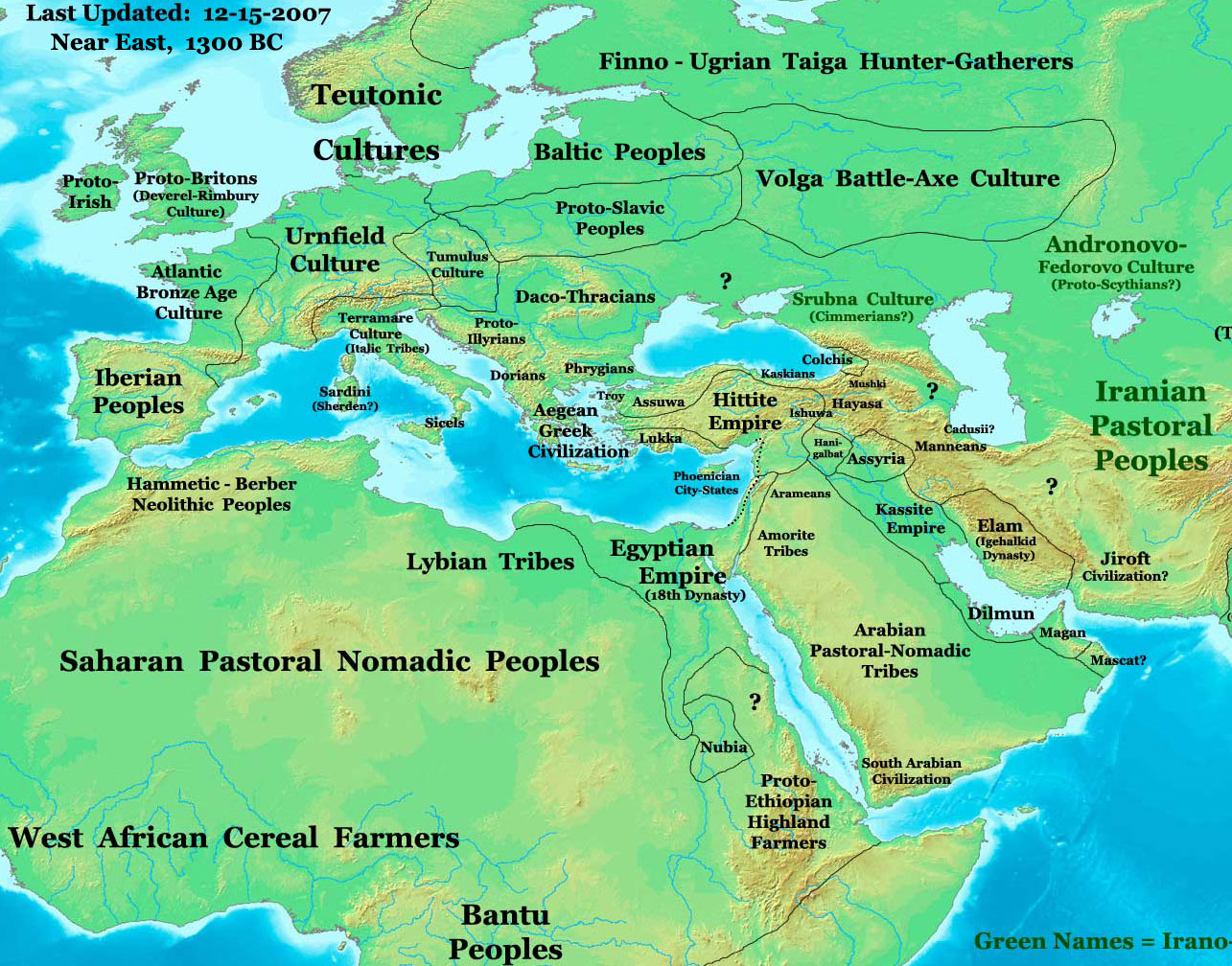

New Kingdom

Possibly as a result of the foreign rule of theHyksos

Hyksos (; Egyptian '' ḥqꜣ(w)- ḫꜣswt'', Egyptological pronunciation: ''hekau khasut'', "ruler(s) of foreign lands") is a term which, in modern Egyptology, designates the kings of the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt (fl. c. 1650–1550 BC). ...

during the Second Intermediate Period, the New Kingdom saw Egypt attempt to create a buffer between the Levant and Egypt, and attain its greatest territorial extent. It expanded far south into Nubia

Nubia () (Nobiin language, Nobiin: Nobīn, ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the Cataracts of the Nile, first cataract of the Nile (just south of Aswan in southern Egypt) and the confluence of the Blue Nile, Blue ...

and held wide territories in the Near East. Egyptian armies fought Hittite armies for control of modern-day Syria.

Eighteenth Dynasty

This was a time of great wealth and power for Egypt. Some of the most important and best-known pharaohs ruled at this time, such as

This was a time of great wealth and power for Egypt. Some of the most important and best-known pharaohs ruled at this time, such as Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut (; also Hatchepsut; Egyptian: '' ḥꜣt- špswt'' "Foremost of Noble Ladies"; or Hatasu c. 1507–1458 BC) was the fifth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. She was the second historically confirmed female pharaoh, af ...

. Hatshepsut is unusual as she was a female pharaoh, a rare occurrence in Egyptian history. She was an ambitious and competent leader, extending Egyptian trade south into present-day Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constitut ...

and north into the Mediterranean. She ruled for twenty years through a combination of widespread propaganda and deft political skill. Her co-regent and successor Thutmose III

Thutmose III (variously also spelt Tuthmosis or Thothmes), sometimes called Thutmose the Great, was the sixth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Officially, Thutmose III ruled Egypt for almost 54 years and his reign is usually dated from 28 ...

("the Napoleon of Egypt") expanded Egypt's army and wielded it with great success. However, late in his reign, he ordered her name hacked out from her monuments. He fought against Asiatic people and was the most successful of Egyptian pharaohs. Amenhotep III built extensively at the temple of Karnak

The Karnak Temple Complex, commonly known as Karnak (, which was originally derived from ar, خورنق ''Khurnaq'' "fortified village"), comprises a vast mix of decayed temples, pylons, chapels, and other buildings near Luxor, Egypt. Constru ...

including the Luxor Temple

The Luxor Temple ( ar, معبد الأقصر) is a large Ancient Egyptian temple complex located on the east bank of the Nile River in the city today known as Luxor (ancient Thebes) and was constructed approximately 1400 BCE. In the Egyptian lang ...

, which consisted of two pylons

Pylon may refer to:

Structures and boundaries

* Pylon (architecture), the gateway to the inner part of an Ancient Egyptian temple or Christian cathedral

* Pylon, a support tower structure for suspension bridges or highways

* Pylon, an orange mar ...

, a colonnade behind the new temple entrance, and a new temple to the goddess Maat

Maat or Maʽat ( Egyptian:

mꜣꜥt /ˈmuʀʕat/, Coptic: ⲙⲉⲓ) refers to the ancient Egyptian concepts of truth, balance, order, harmony, law, morality, and justice. Ma'at was also the goddess who personified these concepts, and re ...

.

During the reign of Thutmose III (c. 1479–1425 BC), pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until th ...

, originally referring to the king's palace, became a form of address for the person who was king.

One of the best-known 18th Dynasty pharaohs is Amenhotep IV, who changed his name to Akhenaten

Akhenaten (pronounced ), also spelled Echnaton, Akhenaton, ( egy, ꜣḫ-n-jtn ''ʾŪḫə-nə-yātəy'', , meaning "Effective for the Aten"), was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh reigning or 1351–1334 BC, the tenth ruler of the Eighteenth ...

in honor of the god Aten

Aten also Aton, Atonu, or Itn ( egy, jtn, ''reconstructed'' ) was the focus of Atenism, the religious system established in ancient Egypt by the Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh Akhenaten. The Aten was the disc of the sun and originally an aspect o ...

. His exclusive worship of the Aten, sometimes called Atenism

Atenism, the Aten religion, the Amarna religion, or the "Amarna heresy" was a religion and the religious changes associated with the ancient Egyptian Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh Akhenaten. The religion centered on the cult of the god Aten, ...

, is often seen as history's first instance of monotheism

Monotheism is the belief that there is only one deity, an all-supreme being that is universally referred to as God. Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxf ...

. Atenism and several changes that accompanied it seriously disrupted Egyptian society. Akhenaten built a new capital at the site of Amarna

Amarna (; ar, العمارنة, al-ʿamārnah) is an extensive Egyptian archaeological site containing the remains of what was the capital city of the late Eighteenth Dynasty. The city was established in 1346 BC, built at the direction of the Ph ...

, which gives his reign and the few that followed their modern name, the Amarna Period

The Amarna Period was an era of Egyptian history during the later half of the Eighteenth Dynasty when the royal residence of the pharaoh and his queen was shifted to Akhetaten ('Horizon of the Aten') in what is now Amarna. It was marked by the ...

. Amarna art

Amarna art, or the Amarna style, is a style adopted in the Amarna Period during and just after the reign of Akhenaten (r. 1351–1334 BC) in the late Eighteenth Dynasty, during the New Kingdom. Whereas Ancient Egyptian art was famously slow to ...

diverged significantly from the previous conventions of Egyptian art

Ancient Egyptian art refers to art produced in ancient Egypt between the 6th millennium BC and the 4th century AD, spanning from Prehistoric Egypt until the Christianization of Roman Egypt. It includes paintings, sculpture ...

. Under a series of successors, of whom the longest reigning were Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun (, egy, twt-ꜥnḫ-jmn), Egyptological pronunciation Tutankhamen () (), sometimes referred to as King Tut, was an Egyptian pharaoh who was the last of his royal family to rule during the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty (ruled ...

and Horemheb

Horemheb, also spelled Horemhab or Haremhab ( egy, ḥr-m-ḥb, meaning "Horus is in Jubilation") was the last pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt (1550–1295 BC). He ruled for at least 14 years between 1319 BC and 1292 BC. ...

. Under them, worship of the old gods was revived and much of the art and monuments that were created during Akhenaten's reign was defaced or destroyed. When Horemheb died without an heir, he named as his successor Ramesses I

Menpehtyre Ramesses I (or Ramses) was the founding pharaoh of ancient Egypt's 19th Dynasty. The dates for his short reign are not completely known but the time-line of late 1292–1290 BC is frequently cited as well as 1295–1294 BC. While R ...

, founder of the Nineteenth Dynasty

The Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt (notated Dynasty XIX), also known as the Ramessid dynasty, is classified as the second Dynasty of the Ancient Egyptian New Kingdom period, lasting from 1292 BC to 1189 BC. The 19th Dynasty and the 20th Dynasty furt ...