Drosera Ramentacea on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Drosera'', which is commonly known as the sundews, is one of the largest

Sundews are

Sundews are

genera

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family as used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In binomial nomenclature, the genus name forms the first part of the binomial s ...

of carnivorous plant

Carnivorous plants are plants that derive some or most of their nutrients from trapping and consuming animals or protozoans, typically insects and other arthropods, and occasionally small mammals and birds. They have adapted to grow in waterlo ...

s, with at least 194 species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

. 2 volumes. These members of the family Droseraceae

Droseraceae is a family of carnivorous flowering plants, also known as the sundew family. It consists of approximately 180 species in three extant genera, the vast majority being in the sundew genus '' Drosera''. The family also contains the wel ...

lure, capture, and digest insects using stalked mucilaginous

Mucilage is a thick gluey substance produced by nearly all plants and some microorganisms. These microorganisms include protists which use it for their locomotion, with the direction of their movement always opposite to that of the secretion of ...

glands covering their leaf surfaces. The insects are used to supplement the poor mineral nutrition of the soil in which the plants grow. Various species, which vary greatly in size and form, are native to every continent except Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

.

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

performed much of the early research into ''Drosera'', engaging in a long series of experiments with ''Drosera rotundifolia

''Drosera rotundifolia'', the round-leaved sundew, roundleaf sundew, or common sundew, is a carnivorous species of flowering plant that grows in bogs, marshes and fens. One of the most widespread sundew species, it has a circumboreal distribut ...

'' which were the first to confirm carnivory in plants. In an 1860 letter, Darwin wrote, “…at the present moment, I care more about ''Drosera'' than the origin of all the species in the world.”

Taxonomy

The botanical name from theGreek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

''drosos'' "dew, dewdrops" refer to the glistening drops of mucilage

Mucilage is a thick gluey substance produced by nearly all plants and some microorganisms. These microorganisms include protists which use it for their locomotion, with the direction of their movement always opposite to that of the secretion of ...

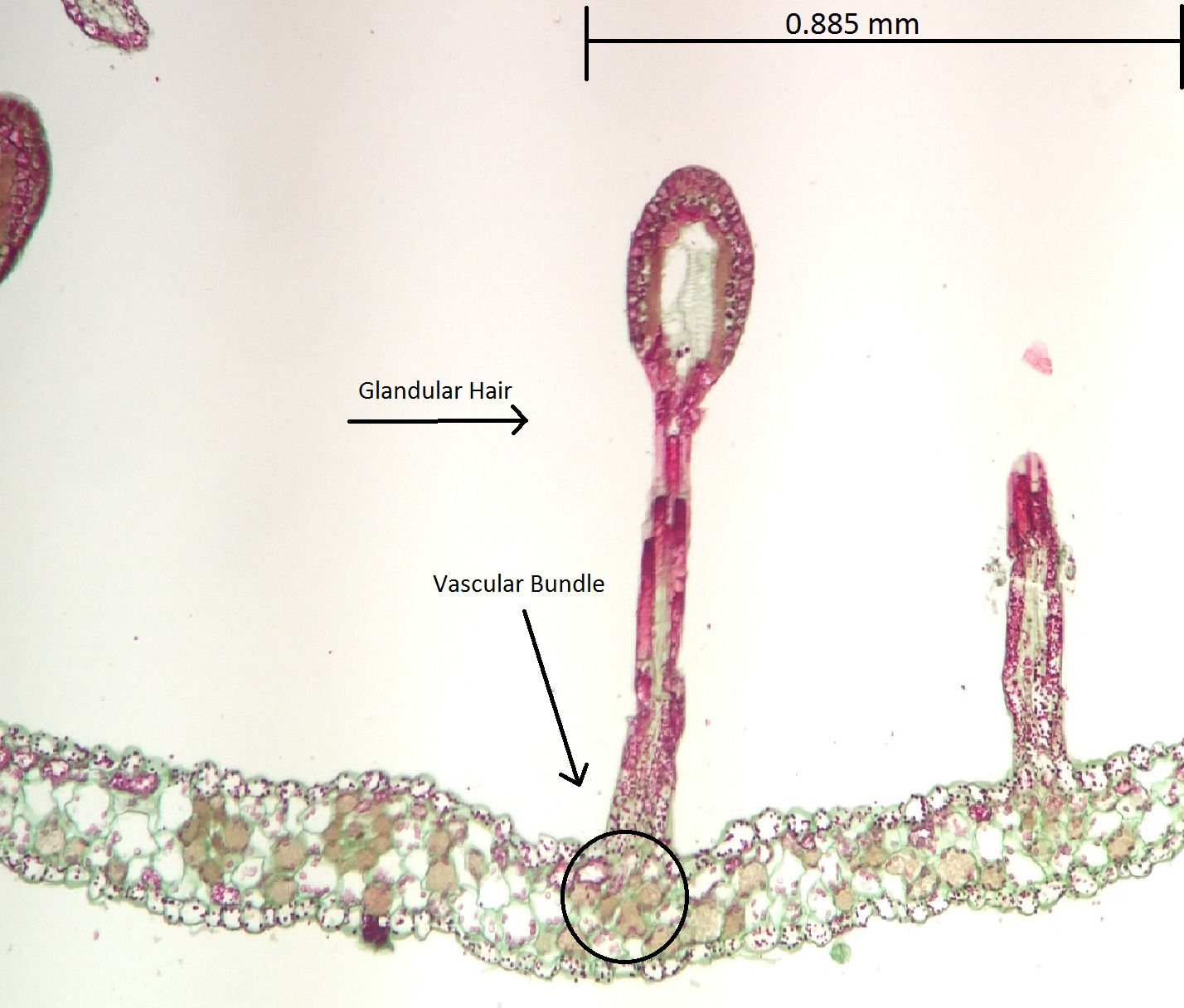

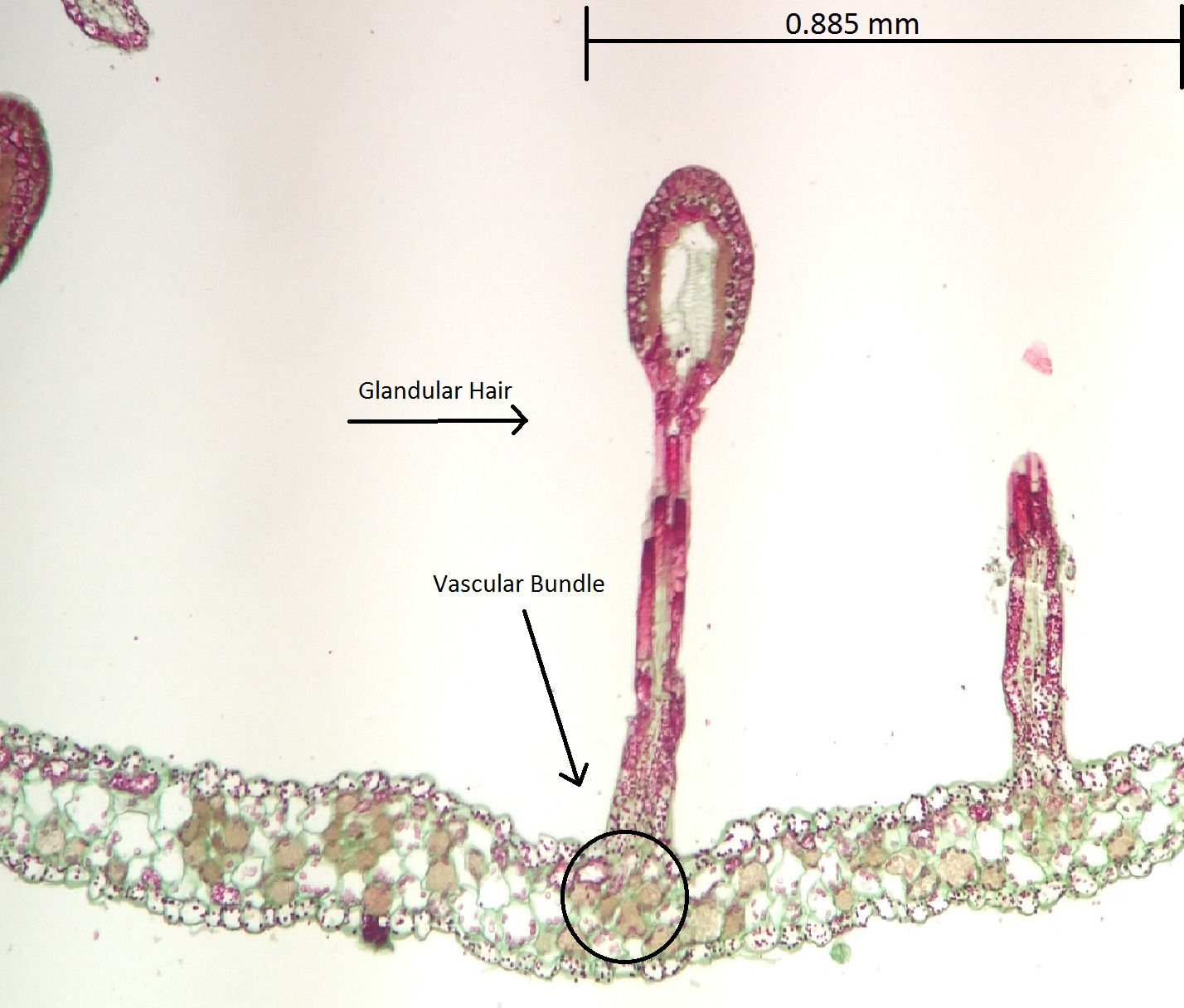

at the tip of the glandular trichome

Trichomes (; ) are fine outgrowths or appendages on plants, algae, lichens, and certain protists. They are of diverse structure and function. Examples are hairs, glandular hairs, scales, and papillae. A covering of any kind of hair on a plant ...

s that resemble drops of morning dew

Dew is water in the form of droplets that appears on thin, exposed objects in the morning or evening due to condensation.

As the exposed surface cools by thermal radiation, radiating its heat, atmospheric moisture condenses at a rate grea ...

. The English common name ''sundew'' also describes this, derived from Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

''ros solis'' meaning "dew of the sun".

The ''Principia Botanica'', published in 1787, states “Sun-dew (''Drosera'') derives its name from small drops of a liquor-like dew, hanging on its fringed leaves, and continuing in the hottest part of the day, exposed to the sun.”

Phylogenetics

The unrootedcladogram

A cladogram (from Greek language, Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an Phylogenetic tree, evolutionary tree because it does not s ...

to the right shows the relationship between various subgenera and classes as defined by the analysis of Rivadavia ''et al.'' The monotypic section '' Meristocaulis'' was not included in the study, so its place in this system is unclear. More recent studies have placed this group near section ''Bryastrum'', so it is placed there below. Also of note, the placement of the section ''Regiae'' in relation to ''Aldrovanda'' and ''Dionaea'' is uncertain. Since the section ''Drosera'' is polyphyletic

A polyphyletic group is an assemblage that includes organisms with mixed evolutionary origin but does not include their most recent common ancestor. The term is often applied to groups that share similar features known as Homoplasy, homoplasies ...

, it shows up multiple times in the cladogram (*).

This phylogenetic study has made the need for a revision of the genus even clearer.

Description

Sundews are

Sundews are perennial

In horticulture, the term perennial ('' per-'' + '' -ennial'', "through the year") is used to differentiate a plant from shorter-lived annuals and biennials. It has thus been defined as a plant that lives more than 2 years. The term is also ...

(or rarely annual

Annual may refer to:

*Annual publication, periodical publications appearing regularly once per year

**Yearbook

**Literary annual

*Annual plant

*Annual report

*Annual giving

*Annual, Morocco, a settlement in northeastern Morocco

*Annuals (band), a ...

) herbaceous plant

Herbaceous plants are vascular plants that have no persistent woody stems above ground. This broad category of plants includes many perennials, and nearly all annuals and biennials.

Definitions of "herb" and "herbaceous"

The fourth edition o ...

s, typically forming prostrate or upright rosettes between in height, depending on the species. Climbing species form scrambling stems which can reach much longer lengths, up to in the case of '' D. erythrogyne''. Sundews have been shown to be able to achieve a lifespan of 50 years. The genus is specialized for nutrient

A nutrient is a substance used by an organism to survive, grow and reproduce. The requirement for dietary nutrient intake applies to animals, plants, fungi and protists. Nutrients can be incorporated into cells for metabolic purposes or excret ...

uptake through its carnivorous behavior, for example the pygmy sundew is missing the enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

s (nitrate reductase

Nitrate reductases are molybdoenzymes that reduce nitrate () to nitrite (). This reaction is critical for the production of protein in most crop plants, as nitrate is the predominant source of nitrogen in fertilized soils.

Types

Euka ...

, in particular) that plants normally use for the uptake of earth-bound nitrates.

Growth form

The genus can be divided into severalhabits

A habit (or wont, as a humorous and formal term) is a routine of behavior that is repeated regularly and tends to occur subconsciously.

A 1903 paper in the ''American Journal of Psychology'' defined a "habit, from the standpoint of psychology, hibernaculum in a winter dormancy period (= Hemicryptophyte">hibernaculum (botany)">hibernaculum in a winter dormancy period (= Hemicryptophyte). All of the North American and European species belong to this group. ''Drosera arcturi'' from Australia (including Tasmania) and New Zealand is another temperate species that dies back to a horn-shaped hibernaculum.

* Subtropical sundews: These species maintain vegetative growth year-round under uniform or nearly uniform climatic conditions.

* Pygmy sundews: A group of roughly 40 Australian species, they are distinguished by miniature growth, the formation of gemmae for asexual reproduction">Gemma (botany)">gemmae for asexual reproduction, and dense formation of hairs in the crown center. These hairs serve to protect the plants from Australia's intense summer sun. Pygmy sundews form the subgenus '' Bryastrum''.

* Tuberous sundews: These nearly 50 Australian species form an underground Drosera subg. Bryastrum">Bryastrum''.

* Tuberous sundews: These nearly 50 Australian species form an underground tuber to survive the extremely dry summers of their habitat, re-emerging in the autumn. These so-called tuberous sundews can be further divided into two groups, those that form rosettes and those that form climbing or scrambling stems. Tuberous sundews comprise the subgenus '' Ergaleium''.

* ''Petiolaris'' complex: A group of tropical Australian species, they live in constantly warm but sometimes wet conditions. Several of the 14 species that comprise this group have developed special strategies to cope with the alternately drier conditions. Many species, for example, have Petiole (botany)">petioles densely covered in

* ''Petiolaris'' complex: A group of tropical Australian species, they live in constantly warm but sometimes wet conditions. Several of the 14 species that comprise this group have developed special strategies to cope with the alternately drier conditions. Many species, for example, have Petiole (botany)">petioles densely covered in

Sundews are characterised by the glandular tentacles, topped with sticky secretions, that cover their

Sundews are characterised by the glandular tentacles, topped with sticky secretions, that cover their  All species of sundew are able to move their tentacles in response to contact with edible prey. The tentacles are extremely sensitive and will bend toward the center of the leaf to bring the insect into contact with as many stalked glands as possible. According to

All species of sundew are able to move their tentacles in response to contact with edible prey. The tentacles are extremely sensitive and will bend toward the center of the leaf to bring the insect into contact with as many stalked glands as possible. According to  A further type of (mostly strong red and yellow) leaf coloration has recently been discovered in a few Australian species ('' D. hartmeyerorum'', '' D. indica''). Their function is not known yet, although they may help in attracting prey.

The leaf morphology of the species within the genus is extremely varied, ranging from the sessile

A further type of (mostly strong red and yellow) leaf coloration has recently been discovered in a few Australian species ('' D. hartmeyerorum'', '' D. indica''). Their function is not known yet, although they may help in attracting prey.

The leaf morphology of the species within the genus is extremely varied, ranging from the sessile

The flowers of sundews, as with nearly all carnivorous plants, are held far above the leaves by a long stem. This physical isolation of the flower from the traps is commonly thought to be an adaptation meant to avoid trapping potential

The flowers of sundews, as with nearly all carnivorous plants, are held far above the leaves by a long stem. This physical isolation of the flower from the traps is commonly thought to be an adaptation meant to avoid trapping potential  The

The

The root systems of most ''Drosera'' are often only weakly developed or have lost their original functions. They are relatively useless for nutrient uptake, and they serve mainly to absorb water and to anchor the plant to the ground; they have long

The root systems of most ''Drosera'' are often only weakly developed or have lost their original functions. They are relatively useless for nutrient uptake, and they serve mainly to absorb water and to anchor the plant to the ground; they have long

The

The

Sundews generally grow in seasonally moist or more rarely constantly wet habitats with acidic soils and high levels of sunlight. Common habitats include

Sundews generally grow in seasonally moist or more rarely constantly wet habitats with acidic soils and high levels of sunlight. Common habitats include

Protection of the genus varies between countries. None of the ''Drosera'' species in the United States are federally protected. Some are listed as

Protection of the genus varies between countries. None of the ''Drosera'' species in the United States are federally protected. Some are listed as

File:Drosera. Tipulidae.jpg, Tipulidae (crane fly) trapped by ''Drosera filiformis''

File:Drosera. Phalaenophana.jpg, Moth, ''Phalaenophana pyramusalis'' (Dark-banded Owlet) trapped by ''Drosera filiformis''

File:Drosera. Eusarca confusaria.jpg, ''Eusarca confusaria'' moth trapped by ''Drosera filiformis''

File:Drosera. Tabanus ventral.jpg, ''Tabanus'' fly trapped by ''Drosera filiformis''

File:Drosophila melanogaster ♀ Melgen, 1830, Drosera capensis Linnaeus, 1753 1100.1.2171.JPG, ''Drosophila melanogaster'' fly trapped by ''Drosera capensis''

Artzneimittle, Tee, und Likör aus fleischfressenden Pflanzen

while another purple or yellow dye was Traditional dyes of the Scottish Highlands, traditionally prepared in the Scottish Highlands using ''D. rotundifolia''. A sundew liqueur is made using fresh leaves from mainly ''Drosera capensis, D. capensis'', ''Drosera spatulata, D. spatulata'', and ''D. rotundifolia''.

A key to ''Drosera'' species, with distribution maps and growing difficulty scale

* [http://www.carnivorousplants.org/ International Carnivorous Plant Society]

Carnivorous Plant FAQ

The Sundew Grow Guides

Sundew images from smugmug

Botanical Society of America, ''Drosera'' - the Sundews

{{Taxonbar, from=Q266 Drosera, Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus

trichome

Trichomes (; ) are fine outgrowths or appendages on plants, algae, lichens, and certain protists. They are of diverse structure and function. Examples are hairs, glandular hairs, scales, and papillae. A covering of any kind of hair on a plant ...

s, which maintain a sufficiently humid environment and serve as an increased condensation surface for morning dew. The ''Petiolaris'' complex comprises the subgenus ''Drosera subg. Lasiocephala, Lasiocephala''.

Although they do not form a single strictly defined growth form, a number of species are often put together in a further group:

* Queensland sundews: A small group of three species ('' D. adelae'', '' D. schizandra'' and '' D. prolifera''), all are native to highly humid habitats in the dim understories of the Australian rainforest.

Leaves and carnivory

leaves

A leaf (: leaves) is a principal appendage of the stem of a vascular plant, usually borne laterally above ground and specialized for photosynthesis. Leaves are collectively called foliage, as in "autumn foliage", while the leaves, stem, ...

. The trapping and digestion mechanism usually employs two types of glands: stalked glands that secrete sweet mucilage to attract and ensnare insects and enzymes to digest them, and sessile

Sessility, or sessile, may refer to:

* Sessility (motility), organisms which are not able to move about

* Sessility (botany), flowers or leaves that grow directly from the stem or peduncle of a plant

* Sessility (medicine), tumors and polyps that ...

gland

A gland is a Cell (biology), cell or an Organ (biology), organ in an animal's body that produces and secretes different substances that the organism needs, either into the bloodstream or into a body cavity or outer surface. A gland may also funct ...

s that absorb the resulting nutrient soup (the latter glands are missing in some species, such as '' D. erythrorhiza''). Small prey, mainly consisting of insects, are attracted by the sweet secretions of the peduncular glands. Upon touching these, the prey become entrapped by sticky mucilage which prevents their progress or escape. Eventually, the prey either succumb to death through exhaustion or through asphyxiation as the mucilage envelops them and clogs their spiracles. Death usually occurs within 15 minutes. The plant meanwhile secretes esterase

In biochemistry, an esterase is a class of enzyme that splits esters into an acid and an alcohol in a chemical reaction with water called hydrolysis (and as such, it is a type of hydrolase).

A wide range of different esterases exist that differ ...

, peroxidase

Peroxidases or peroxide reductases ( EC numberbr>1.11.1.x are a large group of enzymes which play a role in various biological processes. They are named after the fact that they commonly break up peroxides, and should not be confused with other ...

, phosphatase

In biochemistry, a phosphatase is an enzyme that uses water to cleave a phosphoric acid Ester, monoester into a phosphate ion and an Alcohol (chemistry), alcohol. Because a phosphatase enzyme catalysis, catalyzes the hydrolysis of its Substrate ...

and protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalysis, catalyzes proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the formation of new protein products ...

enzymes

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as pro ...

. These enzymes dissolve the insect and free the nutrients contained within it. This nutrient mixture is then absorbed through the leaf surfaces to be used by the rest of the plant.

All species of sundew are able to move their tentacles in response to contact with edible prey. The tentacles are extremely sensitive and will bend toward the center of the leaf to bring the insect into contact with as many stalked glands as possible. According to

All species of sundew are able to move their tentacles in response to contact with edible prey. The tentacles are extremely sensitive and will bend toward the center of the leaf to bring the insect into contact with as many stalked glands as possible. According to Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

, the contact of the legs of a small gnat with a single tentacle is enough to induce this response. This response to touch is known as thigmonasty

In biology, thigmonasty or seismonasty is the nastic movement, nastic (non-directional) response of a plant or fungus to touch or vibration. Conspicuous examples of thigmonasty include many species in the Fabaceae, leguminous family (biology), su ...

, and is quite rapid in some species. The outer tentacles (recently coined as "snap-tentacles") of '' D. burmanni'' and '' D. sessilifolia'' can bend inwards toward prey in a matter of seconds after contact, while '' D. glanduligera'' is known to bend these tentacles in toward prey in tenths of a second. In addition to tentacle movement, some species are able to bend their leaves to various degrees to maximize contact with the prey. Of these, '' D. capensis'' exhibits what is probably the most dramatic movement, curling its leaf completely around prey in 30 minutes. Some species, such as '' D. filiformis'', are unable to bend their leaves in response to prey.

ovate

Ovate may refer to:

* Ovate (egg-shaped) leaves, tepals, or other botanical parts

*Ovate, a type of prehistoric stone hand axe

* Ovates, one of three ranks of membership in the Welsh Gorsedd

* Vates or ovate, a term for ancient Celtic bards ...

leaves of ''D. erythrorhiza'' to the bipinnately divided acicular leaves of '' D. binata''.

While the exact physiological mechanism of the sundew's carnivorous response is not yet known, some studies have begun to shed light on how the plant is able to move in response to mechanical and chemical stimulation to envelop and digest prey. Individual tentacles, when mechanically stimulated, fire action potentials that terminate near the base of the tentacle, resulting in rapid movement of the tentacle towards the center of the leaf. This response is more prominent when marginal tentacles further away from the leaf center are stimulated. The tentacle movement response is achieved through auxin-mediated acid growth

Acid growth refers to the ability of plant cells and plant cell walls to elongate or expand quickly at low (acidic) pH. The cell wall needs to be modified in order to maintain the turgor pressure. This modification is controlled by plant hormones ...

. When action potentials reach their target cells, the plant hormone auxin

Auxins (plural of auxin ) are a class of plant hormones (or plant-growth regulators) with some morphogen-like characteristics. Auxins play a cardinal role in coordination of many growth and behavioral processes in plant life cycles and are essent ...

causes protons (H+ ions) to be pumped out of the plasma membrane into the cell wall, thereby reducing the pH and making the cell wall more acidic. The resulting reduction in pH causes the relaxation of the cell wall protein, expansin, and allows for an increase in cell volume via osmosis and turgor. As a result of differential cell growth rates, the sundew tentacles are able to achieve movement towards prey and the leaf center through the bending caused by expanding cells. Among some ''Drosera'' species, a second bending response occurs in which non-local, distant tentacles bend towards prey as well as the bending of the entire leaf blade to maximize contact with prey. While mechanical stimulation is sufficient to achieve a localized tentacle bend response, both mechanical and chemical stimuli are required for the secondary bending response to occur.

Flowers and fruit

The flowers of sundews, as with nearly all carnivorous plants, are held far above the leaves by a long stem. This physical isolation of the flower from the traps is commonly thought to be an adaptation meant to avoid trapping potential

The flowers of sundews, as with nearly all carnivorous plants, are held far above the leaves by a long stem. This physical isolation of the flower from the traps is commonly thought to be an adaptation meant to avoid trapping potential pollinator

A pollinator is an animal that moves pollen from the male anther of a flower to the female carpel, stigma of a flower. This helps to bring about fertilization of the ovules in the flower by the male gametes from the pollen grains.

Insects are ...

s. The mostly unforked inflorescence

In botany, an inflorescence is a group or cluster of flowers arranged on a plant's Plant stem, stem that is composed of a main branch or a system of branches. An inflorescence is categorized on the basis of the arrangement of flowers on a mai ...

s are spikes

The SPIKES protocol is a method used in clinical medicine to break bad news to patients and families. As receiving bad news can cause distress and anxiety, clinicians need to deliver the news carefully. Using the SPIKES method for introducing and ...

, whose flowers open one at a time and usually only remain open for a short period. Flowers open in response to light intensity (often opening only in direct sunlight), and the entire inflorescence is also heliotropic, moving in response to the sun's position in the sky.

The

The radially symmetrical

Symmetry in biology refers to the symmetry observed in organisms, including plants, animals, fungi, and bacteria. External symmetry can be easily seen by just looking at an organism. For example, the face of a human being has a plane of symme ...

(actinomorphic

Floral symmetry describes whether, and how, a flower, in particular its perianth, can be divided into two or more identical or mirror-image parts.

Uncommonly, flowers may have no axis of symmetry at all, typically because their parts are spirall ...

) flowers are always perfect

Perfect commonly refers to:

* Perfection; completeness, and excellence

* Perfect (grammar), a grammatical category in some languages

Perfect may also refer to:

Film and television

* ''Perfect'' (1985 film), a romantic drama

* ''Perfect'' (20 ...

and have five parts (the exceptions to this rule are the four-petaled '' D. pygmaea'' and the eight to 12-petaled '' D. heterophylla''). Most of the species have small flowers (<1.5 cm or 0.6 in). A few species, however, such as '' D. regia'' and '' D. cistiflora'', have flowers or more in diameter. In general, the flowers are white or pink. Australian species display a wider range of colors, including orange ('' D. callistos''), red ('' D. adelae''), yellow ('' D. zigzagia'') or metallic violet ('' D. microphylla'').

The ovary

The ovary () is a gonad in the female reproductive system that produces ova; when released, an ovum travels through the fallopian tube/ oviduct into the uterus. There is an ovary on the left and the right side of the body. The ovaries are end ...

is superior

Superior may refer to:

*Superior (hierarchy), something which is higher in a hierarchical structure of any kind

Places

* Superior (proposed U.S. state), an unsuccessful proposal for the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to form a separate state

*Lak ...

and develops into a dehiscent

Dehiscence is the splitting of a mature plant structure along a built-in line of weakness to release its contents. This is common among fruits, anthers and sporangia. Sometimes this involves the complete detachment of a part. Structures that op ...

seed capsule

In botany, a capsule is a type of simple, dry, though rarely fleshy dehiscent fruit produced by many species of angiosperms (flowering plants).

Origins and structure

The capsule (Latin: ''capsula'', small box) is derived from a compound (mult ...

bearing numerous tiny seeds. The pollen

Pollen is a powdery substance produced by most types of flowers of seed plants for the purpose of sexual reproduction. It consists of pollen grains (highly reduced Gametophyte#Heterospory, microgametophytes), which produce male gametes (sperm ...

grain type is compound, which means four microspore

Microspores are land plant spores that develop into male gametophytes, whereas megaspores develop into female gametophytes. The male gametophyte gives rise to sperm cells, which are used for fertilization of an egg cell to form a zygote. Megaspo ...

s (pollen grains) are stuck together with a protein called callose

Callose is a plant polysaccharide. Its production is due to the glucan synthase-like gene (GLS) in various places within a plant. It is produced to act as a temporary cell wall in response to stimuli such as stress or damage. Callose is composed ...

.

Roots

The root systems of most ''Drosera'' are often only weakly developed or have lost their original functions. They are relatively useless for nutrient uptake, and they serve mainly to absorb water and to anchor the plant to the ground; they have long

The root systems of most ''Drosera'' are often only weakly developed or have lost their original functions. They are relatively useless for nutrient uptake, and they serve mainly to absorb water and to anchor the plant to the ground; they have long hair

Hair is a protein filament that grows from follicles found in the dermis. Hair is one of the defining characteristics of mammals.

The human body, apart from areas of glabrous skin, is covered in follicles which produce thick terminal and ...

s.

A few South African species use their roots for water and food storage. Some species have wiry root systems that remain during frosts if the stem dies. Some species, such as ''D. adelae'' and '' D. hamiltonii'', use their roots for asexual propagation, by sprouting plantlets along their length. Some Australian species form underground corm

Corm, bulbo-tuber, or bulbotuber is a short, vertical, swollen, underground plant stem that serves as a storage organ that some plants use to survive winter or other adverse conditions such as summer drought and heat (perennation).

The word ''c ...

s for this purpose, which also serve to allow the plants to survive dry summers. The roots of pygmy sundews are often extremely long in proportion to their size, with a 1-cm (0.4-in) plant extending roots over beneath the soil surface. Some pygmy sundews, such as '' D. lasiantha'' and '' D. scorpioides'', also form adventitious root

Important structures in plant development are buds, Shoot (botany), shoots, roots, leaf, leaves, and flowers; plants produce these tissues and structures throughout their life from meristems located at the tips of organs, or between mature tissues. ...

s as supports.

'' D. intermedia'' and '' D. rotundifolia'' have been reported to form arbuscular mycorrhiza

An arbuscular mycorrhiza (AM) (plural ''mycorrhizae'') is a type of mycorrhiza in which the symbiont fungus (''Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi'', or AMF) penetrates the cortical cells of the roots of a vascular plant forming arbuscules. Arbuscul ...

e, which penetrate the plant's tissues, they also host fungi like endophyte

An endophyte is an endosymbiont, often a bacterium or fungus, that lives within a plant for at least part of its life cycle without causing apparent disease. Endophytes are ubiquitous and have been found in all species of plants studied to date; ...

s to collect nutrients when they grow in poor soil and form symbiotic relationships.

Reproduction

Many species of sundews are self-fertile; their flowers will often self-pollinate upon closing. Often, numerous seeds are produced. The tiny black seeds germinate in response to moisture and light, while seeds of temperate species also require cold, damp, stratification to germinate. Seeds of the tuberous species require a hot, dry summer period followed by a cool, moist winter to germinate.Vegetative reproduction

Vegetative reproduction (also known as vegetative propagation, vegetative multiplication or cloning) is a form of asexual reproduction occurring in plants in which a new plant grows from a fragment or cutting of the parent plant or specializ ...

occurs naturally in some species that produce stolons

In biology, a stolon ( from Latin '' stolō'', genitive ''stolōnis'' – "branch"), also known as a runner, is a horizontal connection between parts of an organism. It may be part of the organism, or of its skeleton. Typically, animal stolons ar ...

or when roots come close to the surface of the soil. Older leaves that touch the ground may sprout plantlets. Pygmy sundews reproduce asexually using specialized scale-like leaves called gemmae. Tuberous sundews can produce offsets from their corms.

In culture, sundews can often be propagated through leaf, crown, or root cuttings, as well as through seeds.

Distribution

range

Range may refer to:

Geography

* Range (geographic), a chain of hills or mountains; a somewhat linear, complex mountainous or hilly area (cordillera, sierra)

** Mountain range, a group of mountains bordered by lowlands

* Range, a term used to i ...

of the sundew genus stretches from Alaska in the north to New Zealand in the south. The centers of diversity

Diversity, diversify, or diverse may refer to:

Business

*Diversity (business), the inclusion of people of different identities (ethnicity, gender, age) in the workforce

*Diversity marketing, marketing communication targeting diverse customers

* ...

are Australia, with roughly 50% of all known species, and South America and southern Africa, each with more than 20 species. A few species are also found in large parts of Eurasia and North America. These areas, however, can be considered to form the outskirts of the generic range, as the ranges of sundews do not typically approach temperate or Arctic areas. Contrary to previous supposition, the evolutionary speciation

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which populations evolve to become distinct species. The biologist Orator F. Cook coined the term in 1906 for cladogenesis, the splitting of lineages, as opposed to anagenesis, phyletic evolution within ...

of this genus is no longer thought to have occurred with the breakup of Gondwana

Gondwana ( ; ) was a large landmass, sometimes referred to as a supercontinent. The remnants of Gondwana make up around two-thirds of today's continental area, including South America, Africa, Antarctica, Australia (continent), Australia, Zea ...

through continental drift

Continental drift is a highly supported scientific theory, originating in the early 20th century, that Earth's continents move or drift relative to each other over geologic time. The theory of continental drift has since been validated and inc ...

. Rather, speciation is now thought to have occurred as a result of a subsequent wide dispersal of its range. The origins of the genus are thought to have been in Africa or Australia.

Europe is home to only three species: '' D. intermedia'', '' D. anglica'', and '' D. rotundifolia''. Where the ranges of the two latter species overlap, they sometimes hybridize to form the sterile '' D. × obovata''. In addition to the three species and the hybrid native to Europe, North America is also home to four additional species; '' D. brevifolia'' is a small annual

Annual may refer to:

*Annual publication, periodical publications appearing regularly once per year

**Yearbook

**Literary annual

*Annual plant

*Annual report

*Annual giving

*Annual, Morocco, a settlement in northeastern Morocco

*Annuals (band), a ...

native to coastal states from Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

to Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

, while '' D. capillaris'', a slightly larger plant with a similar range, is also found in areas of the Caribbean. The third species, '' D. linearis'', is native to the northern United States and southern Canada. '' D. filiformis'' has two subspecies

In Taxonomy (biology), biological classification, subspecies (: subspecies) is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics (Morphology (biology), morpholog ...

native to the East Coast of North America, the Gulf Coast

The Gulf Coast of the United States, also known as the Gulf South or the South Coast, is the coastline along the Southern United States where they meet the Gulf of Mexico. The coastal states that have a shoreline on the Gulf of Mexico are Tex ...

, and the Florida panhandle

The Florida panhandle (also known as West Florida and Northwest Florida) is the northwestern part of the U.S. state of Florida. It is a Salient (geography), salient roughly long, bordered by Alabama on the west and north, Georgia (U.S. state ...

.

This genus is often described as cosmopolitan

Cosmopolitan may refer to:

Internationalism

* World citizen, one who eschews traditional geopolitical divisions derived from national citizenship

* Cosmopolitanism, the idea that all of humanity belongs to a single moral community

* Cosmopolitan ...

, meaning it has worldwide distribution. The botanist Ludwig Diels

Friedrich Ludwig Emil Diels (24 September 1874 – 30 November 1945) was a German botanist.

Diels was born in Hamburg, the son of the classical scholar Hermann Alexander Diels. From 1900 to 1902 he traveled together with Ernst Georg Pritzel thro ...

, author of the only monograph

A monograph is generally a long-form work on one (usually scholarly) subject, or one aspect of a subject, typically created by a single author or artist (or, sometimes, by two or more authors). Traditionally it is in written form and published a ...

of the family to date, called this description an "arrant misjudgment of this genus' highly unusual distributional circumstances (''arge Verkennung ihrer höchst eigentümlichen Verbreitungsverhältnisse'')", while admitting sundew species do "occupy a significant part of the Earth's surface (''einen beträchtlichen Teil der Erdoberfläche besetzt'')".

He particularly pointed to the absence of ''Drosera'' species from almost all arid

Aridity is the condition of geographical regions which make up approximately 43% of total global available land area, characterized by low annual precipitation, increased temperatures, and limited water availability.Perez-Aguilar, L. Y., Plata ...

climate zones, countless rainforest

Rainforests are forests characterized by a closed and continuous tree Canopy (biology), canopy, moisture-dependent vegetation, the presence of epiphytes and lianas and the absence of wildfire. Rainforests can be generally classified as tropi ...

s, the American Pacific Coast, Polynesia

Polynesia ( , ) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of more than 1,000 islands scattered over the central and southern Pacific Ocean. The indigenous people who inhabit the islands of Polynesia are called Polynesians. They have many things in ...

, the Mediterranean region, and North Africa, as well as the scarcity of species diversity in temperate zones, such as Europe and North America.

Habitat

Sundews generally grow in seasonally moist or more rarely constantly wet habitats with acidic soils and high levels of sunlight. Common habitats include

Sundews generally grow in seasonally moist or more rarely constantly wet habitats with acidic soils and high levels of sunlight. Common habitats include bog

A bog or bogland is a wetland that accumulates peat as a deposit of dead plant materials often mosses, typically sphagnum moss. It is one of the four main types of wetlands. Other names for bogs include mire, mosses, quagmire, and musk ...

s, fen

A fen is a type of peat-accumulating wetland fed by mineral-rich ground or surface water. It is one of the main types of wetland along with marshes, swamps, and bogs. Bogs and fens, both peat-forming ecosystems, are also known as mires ...

s, swamp

A swamp is a forested wetland.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p. Swamps are considered to be transition zones because both land and water play a role in ...

s, marsh

In ecology, a marsh is a wetland that is dominated by herbaceous plants rather than by woody plants.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p More in genera ...

es, the tepui

A tepui , or tepuy (), is a member of a family of table-top mountains or mesas found in northern South America, especially in Venezuela, western Guyana, and northern Brazil. The word tepui means "house of the gods" in the native tongue of the ...

s of Venezuela, the wallum

Wallum, also known as the Wallum Sand Heaths or Wallum Country, is an Australian ecosystem of coastal south-eastern Queensland, extending into north-eastern New South Wales. It is characterised by flora-rich shrubland and heathland on deep, ...

s of coastal Australia, the fynbos

Fynbos (; , ) is a small belt of natural shrubland or heathland vegetation located in the Western Cape and Eastern Cape provinces of South Africa. The area is predominantly coastal and mountainous, with a Mediterranean climate. The fynbos ...

of South Africa, and moist streambanks. Many species grow in association with sphagnum moss

''Sphagnum'' is a genus of approximately 380 accepted species of mosses, commonly known as sphagnum moss, also bog moss and quacker moss (although that term is also sometimes used for peat). Accumulations of ''Sphagnum'' can store water, since ...

, which absorbs much of the soil's nutrient supply and also acidifies the soil, making nutrients less available to plant life. This allows sundews, which do not rely on soil-bound nutrients, to flourish where more dominating vegetation would usually outcompete them.

The genus, though, is very variable in terms of habitat. Individual sundew species have adapted to a wide variety of environments, including atypical habitats, such as rainforests, deserts ('' D. burmanni'' and '' D. indica''), and even highly shaded environments (Queensland sundews). The temperate species, which form hibernacula in the winter, are examples of such adaptation to habitats; in general, sundews tend to inhabit warm climates, and are only moderately frost-resistant.

Conservation status

Protection of the genus varies between countries. None of the ''Drosera'' species in the United States are federally protected. Some are listed as

Protection of the genus varies between countries. None of the ''Drosera'' species in the United States are federally protected. Some are listed as threatened

A threatened species is any species (including animals, plants and fungi) which is vulnerable to extinction in the near future. Species that are threatened are sometimes characterised by the population dynamics measure of ''critical depensatio ...

or endangered

An endangered species is a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular political jurisdiction. Endangered species may be at risk due to factors such as habitat loss, poaching, inv ...

at the state level, but this gives little protection to lands under private ownership. Many of the remaining native populations are located on protected land, such as national park

A national park is a nature park designated for conservation (ethic), conservation purposes because of unparalleled national natural, historic, or cultural significance. It is an area of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that is protecte ...

s or wildlife preserves. ''Drosera'' species are protected by law in many European countries, such as Germany, Austria, Switzerland, the Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, France, and Bulgaria. In Australia, they are listed as "threatened". In South America and the Caribbean, ''Drosera'' species in a number of areas are considered critical, endangered or vulnerable, while other areas have not been surveyed. At the same time that species are at risk in South Africa, new species continue to be discovered in the Western Cape and Madagascar.

Worldwide, ''Drosera'' are at risk of extinction due to the destruction of natural habitat through urban and agricultural development. They are also threatened by the illegal collection of wild plants for the horticultural trade. An additional risk is climate change, environmental change, because species are often specifically adapted to a precise location and set of conditions.

Currently, the largest threat in Europe and North America is loss of wetland habitat. Causes include urban development and the draining of bogs for agricultural uses and peat harvesting.

Such threats have led to the extirpation of some species from parts of their former range. Reintroduction of plants into such habitats is usually difficult or impossible, as the ecological needs of certain populations are closely tied to their geographical location. Increased legal protection of bogs and moors, and a concentrated effort to renaturalize such habitats, are possible ways to combat threats to ''Drosera'' plants' survival. As part of the landscape, sundews are often overlooked or not recognized at all.

In South Africa and Australia, two of the three centers of species diversity, the natural habitats of these plants are undergoing a high degree of pressure from human activities. The African sundews ''Drosera insolita, D. insolita'' and ''Drosera katangensis, D. katangensis'' are listed as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), while ''Drosera bequaertii, D. bequaertii'' is listed as vulnerable. Expanding population centers such as Queensland, Perth, and Cape Town, and the draining of moist areas for agriculture and forestry in rural areas threaten many such habitats. The droughts that have been sweeping Australia in the 21st century pose a threat to many species by drying up previously moist areas.

Those species endemic to a very limited area are often most threatened by the collection of plants from the wild. ''Drosera madagascariensis, D. madagascariensis'' is considered endangered in Madagascar because of the large-scale removal of plants from the wild for exportation; 10 - 200 million plants are harvested for commercial medicinal use annually.

Gallery of prey

Uses

Thecorm

Corm, bulbo-tuber, or bulbotuber is a short, vertical, swollen, underground plant stem that serves as a storage organ that some plants use to survive winter or other adverse conditions such as summer drought and heat (perennation).

The word ''c ...

s of the tuberous sundews native to Australia are considered a delicacy by the Indigenous Australians. Some of these corms were also used to dye textiles,Plantarara (2001)Artzneimittle, Tee, und Likör aus fleischfressenden Pflanzen

while another purple or yellow dye was Traditional dyes of the Scottish Highlands, traditionally prepared in the Scottish Highlands using ''D. rotundifolia''. A sundew liqueur is made using fresh leaves from mainly ''Drosera capensis, D. capensis'', ''Drosera spatulata, D. spatulata'', and ''D. rotundifolia''.

Traditional medicine

The Zafimaniry people in central Madagascar have been using ''Drosera madagascariensis'' as a remedy for dysentery and fever. In Western medicine, sundews were used as herbal medicine, medicinal herbs as early as the 12th century, when an Italian doctor from the School of Salerno, Matthaeus Platearius, described the plant as an herbal remedy for coughs under the name ''herba sole''. Culbreth's 1927 ''Materia Medica'' listed ''D. rotundifolia'', ''D. anglica'' and '' D. linearis'' as being used as stimulants and expectorants, and "of doubtful efficacy" for treating bronchitis, whooping cough, and tuberculosis. Sundew tea was recommended by herbalists for dry coughs, bronchitis, whooping cough, asthma and "bronchial cramps". The ''French Pharmacopoeia'' of 1965 listed sundew for the treatment of inflammatory diseases such as asthma, chronic bronchitis and whooping cough. ''Drosera'' has been used commonly in cough preparations in Germany and elsewhere in Europe. In traditional medicine practices, ''Drosera'' is used to treat ailments such as asthma, coughs, lung infections, and stomach ulcers. Herbal preparations are primarily made using the roots, flowers, and fruit-like capsules. Since all native sundews species are protected in many parts of Europe and North America, extracts are usually prepared using cultivated fast-growing sundews (specifically ''D. rotundifolia'', '' D. intermedia'', ''D. anglica'', ''Drosera ramentacea, D. ramentacea'' and ''D. madagascariensis'') or from plants collected and imported from Madagascar, Spain, France, Finland and the Baltics. Sundews are historically mentioned as an aphrodisiac (hence the common name ''lustwort''). They are mentioned as a folk remedy for treatment of warts, corns, and freckles.As ornamental plants

Because of their carnivorous nature and the beauty of their glistening traps, sundews have become favorite ornamental plants; however, the environmental requirements of most species are relatively stringent and can be difficult to meet in cultivation. As a result, most species are unavailable commercially. A few of the hardiest varieties, however, have made their way into the mainstream nursery business and can often be found for sale next to Venus flytraps. These most often include ''Drosera capensis, D. capensis'', ''Drosera aliciae, D. aliciae'', and ''Drosera spatulata, D. spatulata''.Rice, Barry. 2006. ''Growing Carnivorous Plants''. Timber Press: Portland, Oregon. Cultivation requirements vary greatly by species. In general, though, sundews require high environmental moisture content, usually in the form of a constantly moist or wet soil substrate. Most species also require this water to be pure, as nutrients, salts, or minerals in their soil can stunt their growth or even kill them. Commonly, plants are grown in a soil substrate containing some combination of dead or livesphagnum moss

''Sphagnum'' is a genus of approximately 380 accepted species of mosses, commonly known as sphagnum moss, also bog moss and quacker moss (although that term is also sometimes used for peat). Accumulations of ''Sphagnum'' can store water, since ...

, sphagnum peat moss, sand, and/or perlite, and are watered with Distilled water, distilled, reverse osmosis, or rain water.

Nano-biotechnology

The mucilage produced by ''Drosera'' has remarkable elastic properties and has made this genus a very attractive subject in biomaterials research. In one recent study, the adhesive mucilages of three species (''D. binata'', ''D. capensis'', and ''D. spatulata'') were analyzed for nanofiber and nanoparticle content. Using atomic force microscopy, transmission electron microscopy, and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, researchers were able to observe networks of nanofibers and nanoparticles of various sizes within the mucilage residues. In addition, calcium, magnesium, and chlorine – key components of biological salts - were identified. These nanoparticles are theorized to increase the viscosity and stickiness of the mucilage, in turn increasing the effectiveness of the trap. More importantly for biomaterials research, however, is the fact that, when dried, the mucilage provides a suitable substrate for the attachment of living cells. This has important implications for tissue engineering, especially because of the elastic qualities of the adhesive. Essentially, a coating of ''Drosera'' mucilage on a surgical implant, such as a replacement hip or an organ transplant, could drastically improve the rate of recovery and decrease the potential for rejection, because living tissue can effectively attach and grow on it. The authors also suggest a wide variety of applications for ''Drosera'' mucilage, including wound treatment, regenerative medicine, or enhancing synthetic adhesives. Because this mucilage can stretch to nearly a million times its original size and is readily available for use, it can be an extremely cost-efficient source of biomaterial.Chemical constituents

Several chemical compounds with potential biological activities are found in sundews, including flavonoids (kaempferol, myricetin, quercetin and hyperoside), quinones (plumbagin, hydroplumbagin glucoside and rossoliside (7–methyl–hydrojuglone–4–glucoside)), and other constituents such as carotenoids, plant acids (e.g. butyric acid, citric acid, formic acid, gallic acid, malic acid, propionic acid), resin, tannins and ascorbic acid (vitamin C).References

Further reading

* * Correa A., Mireya D.; Silva, Tania Regina Dos Santos: ''Drosera (Droseraceae)'', in: Flora Neotropica, Monograph 96, New York, 2005 * Lowrie, Allen: ''Carnivorous Plants of Australia'', Vol. 1–3, English, Nedlands, Western Australia, 1987–1998 * * Olberg, Günter: ''Sonnentau'', Natur und Volk, Bd. 78, Heft 1/3, pp. 32–37, Frankfurt, 1948 * Seine, Rüdiger; Barthlott, Wilhelm: ''Some proposals on the infrageneric classification of Drosera L.'', Taxon 43, 583 - 589, 1994 * Schlauer, Jan: ''A dichotomous key to the genus Drosera L. (Droseraceae)'', Carnivorous Plant Newsletter, Vol. 25 (1996)External links

A key to ''Drosera'' species, with distribution maps and growing difficulty scale

* [http://www.carnivorousplants.org/ International Carnivorous Plant Society]

Carnivorous Plant FAQ

The Sundew Grow Guides

Sundew images from smugmug

Botanical Society of America, ''Drosera'' - the Sundews

{{Taxonbar, from=Q266 Drosera, Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus