Dmitri Merezhkovsky on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

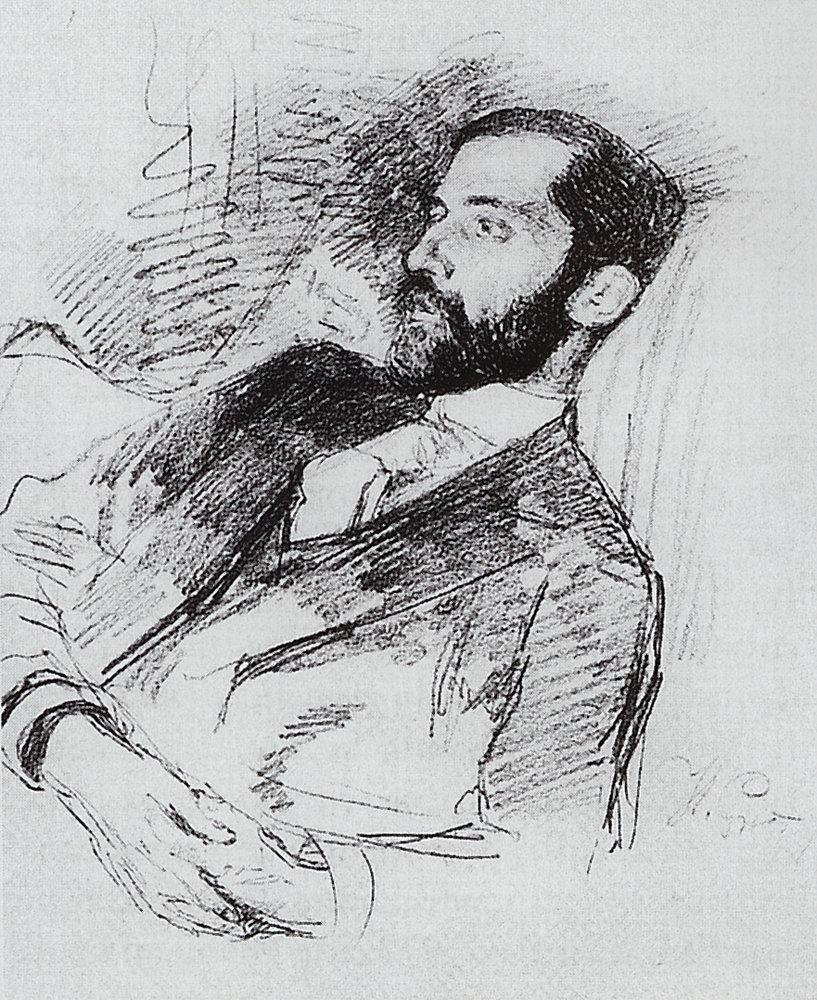

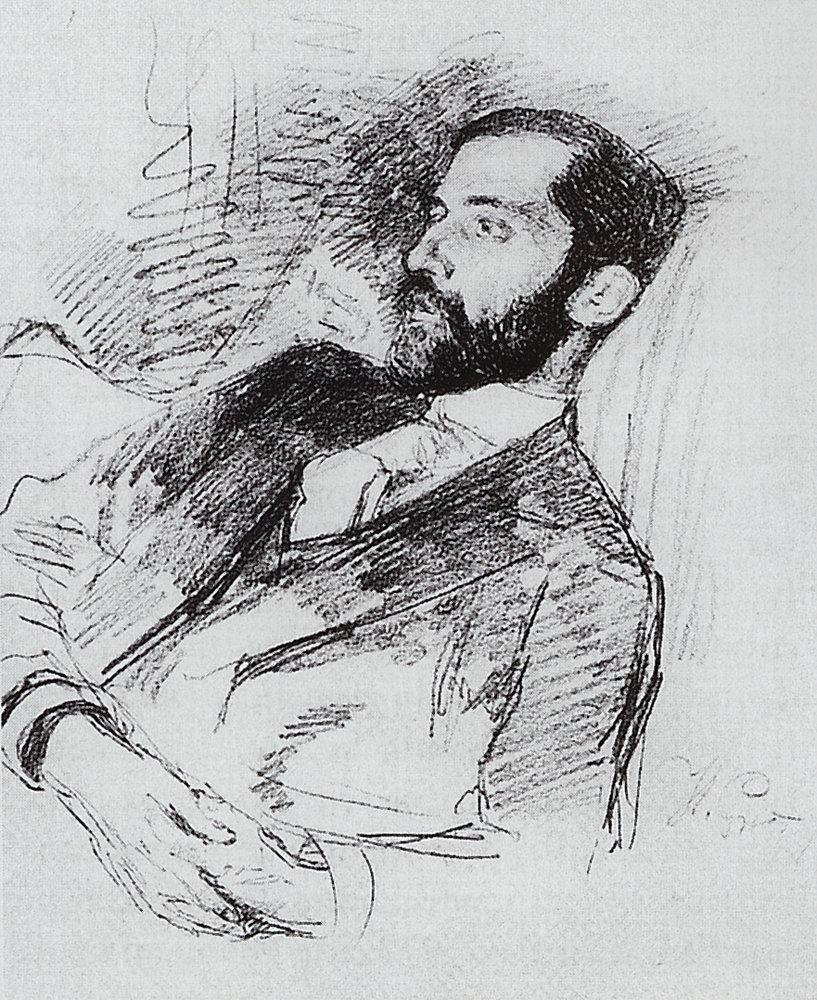

Dmitry Sergeyevich Merezhkovsky ( rus, Дми́трий Серге́евич Мережко́вский, p=ˈdmʲitrʲɪj sʲɪrˈɡʲejɪvʲɪtɕ mʲɪrʲɪˈʂkofskʲɪj; – December 9, 1941) was a

In May 1890

In May 1890

''The Death of the Gods'' which came out in 1895 (''Severny Vestnik'', Nos.1–6) opened the ''Christ & Antichrist'' trilogy and in retrospect is regarded as the first Russian symbolist novel. Sceptics prevailed (most of them denouncing the author's alleged

''The Death of the Gods'' which came out in 1895 (''Severny Vestnik'', Nos.1–6) opened the ''Christ & Antichrist'' trilogy and in retrospect is regarded as the first Russian symbolist novel. Sceptics prevailed (most of them denouncing the author's alleged

After the 22nd session, in April 1903, the Meetings of the group (by this time known as ''Bogoiskateli'', or God-seekers) were cancelled by the procurator of the

After the 22nd session, in April 1903, the Meetings of the group (by this time known as ''Bogoiskateli'', or God-seekers) were cancelled by the procurator of the

In ''The Forthcoming Ham '' (Gryadushchu Ham, 1905) Merezhkovsky explained his political stance, seeing, as usual, all things refracted into Trinities. Using the pun ("

In ''The Forthcoming Ham '' (Gryadushchu Ham, 1905) Merezhkovsky explained his political stance, seeing, as usual, all things refracted into Trinities. Using the pun ("

Revolution and Religion

– russianway.rchgi.spb.ru. – 1907. In one of the articles he contributed to it, ''Revolution and Religion'', Merezhkovsky wrote: "Now it's almost impossible to foresee what a deadly force this revolutionary tornado starting upwards from the society's bottom will turn out to be. The church will be crashed down and the monarchy too, but with them – what if Russia itself is to perish – if not the timeless soul of it, then its body, the state?" Again, what at the time was looked upon as dull political grotesque a decade later turned into grim reality. In 1908 the play about "the routinous side of the revolution," ''Poppy Blossom'' (Makov Tzvet) came out, all three Troyebratstvo members credited as co-authors. It was followed by "The Last Saint" (), a study on

In

In

books.google

* '' Peter and Alexis'' (book 3 of the Christ and Antichrist trilogy, 1904) ;The Kingdom of the Beast * ''Paul I'' (Pavel Pervy, 1908) * ''Alexander the First'' (Аleksandr Pervy, 1913) * ''December 14'' (Chetyrnadtsatoye Dekabrya, 1918)

Biography

*. * Anatoly Rykov, Rykov, A.

"Twilight of the Silver Age. Politics and the Russian Religious Modernism in D.S.Merezhkovsky's novel Napoleon" in Studia Culturae 2016 № 1 (27), pp. 9–17 (in Russian)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Merezhkovsky, Dmitry Sergeyevich 1865 births 1941 deaths Writers from Saint Petersburg People from Sankt-Peterburgsky Uyezd Essayists from the Russian Empire Novelists from the Russian Empire Philosophers from the Russian Empire Male poets from the Russian Empire Russian historical novelists Symbolist novelists Symbolist poets Soviet novelists Soviet male writers Saint Petersburg State University alumni Burials at Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois Russian Cemetery

Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

novelist, poet, religious thinker, and literary critic. A seminal figure of the Silver Age of Russian Poetry

Silver Age (Сере́бряный век) is a term traditionally applied by Russian philologists to the last decade of the 19th century and first two or three decades of the 20th century. It was an exceptionally creative period in the history o ...

, regarded as a co-founder of the Symbolist movement, Merezhkovsky – with his wife, the poet Zinaida Gippius

Zinaida Nikolayevna Gippius (; – 9 September 1945), a Russian poet, playwright, novelist, editor and religious thinker, became one of the major figures in Russian symbolism.

She began writing at an early age, and by the time she met Dmitry ...

– was twice forced into political exile

Exile or banishment is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons ...

. During his second exile (1918–1941) he continued publishing successful novels and gained recognition as a critic of the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. Known both as a self-styled religious prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divinity, divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings ...

with his own slant on apocalyptic Christianity, and as the author of philosophical historical novel

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which a fictional plot takes place in the setting of particular real historical events. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literature, it can also be applied to oth ...

s which combined fervent idealism with literary innovation, Merezhkovsky became a nine-time nominee for the Nobel Prize in Literature

The Nobel Prize in Literature, here meaning ''for'' Literature (), is a Swedish literature prize that is awarded annually, since 1901, to an author from any country who has, in the words of the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, "in ...

, which he came closest to winning in 1933.

However, due to contested claims that he expressed regard for Fascism as a lesser evil than Communism during the outbreak of war between Germany and the USSR shortly prior to his death, his work largely fell into neglect after World War II.

Biography

Dmitry Sergeyevich Merezhkovsky was born on , inSaint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

, the sixth son in his family. His father, Sergey Ivanovich Merezhkovsky, served as a senior official in several Russian local governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

s' cabinets (including that of in Orenburg

Orenburg (, ), formerly known as Chkalov (1938–1957), is the administrative center of Orenburg Oblast, Russia. It lies in Eastern Europe, along the banks of the Ural River, being approximately southeast of Moscow.

Orenburg is close to the ...

) before entering Emperor Alexander II's court office as a Privy Councillor.''Mihaylov, Oleg''. "The Prisoner of Culture". The Foreword to The Complete Work of D.S.Merezhkovsky in 4 volumes. 1990. Pravda Publishers. His mother Varvara Vasilyevna Merezhkovskaya (née Chesnokova) was a daughter of a senior Saint Petersburg security official. Fond of arts and literature, she was what Dmitry Merezhkovsky later remembered as the guiding light of his rather lonely childhood (despite the presence of his five brothers and three sisters). There were only three people Merezhkovsky had any affinity with in his whole lifetime, and his mother, a woman "of rare beauty and angelic nature" according to biographer Yuri Zobnin, was the first and the most important of those.''Zobnin, Yuri''. The Life and Deeds of Dmitry Merezhkovsky. 2008 // Moscow. – Molodaya Gvardiya Publishers. Lives of Distinguished People series, issue 1091. pp. 15–16

Early years

Dmitry Merezhkovsky spent his early years on theYelagin Island

Yelagin Island () is a park island at the mouth of the Neva River which is part of St. Petersburg, Russia. Yelagin Island is home to the Yelagin Palace but has a few other buildings as well. A former suburban estate of 18 century Russian no ...

in Saint Petersburg, in a palace-like cottage which served as a summer dacha

A dacha (Belarusian, Ukrainian language, Ukrainian and rus, дача, p=ˈdatɕə, a=ru-dacha.ogg) is a seasonal or year-round second home, often located in the exurbs of former Soviet Union, post-Soviet countries, including Russia. A cottage (, ...

for the family. In the city the family occupied an old house facing the Summer Garden

The Summer Garden () is a historic public garden that occupies an eponymous island between the Neva, Fontanka, Moika, and the Swan Canal in

downtown Saint Petersburg, Russia and shares its name with the adjacent Summer Palace of Peter th ...

s, near . The Merezhkovskys also owned a large estate in Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

, near a road leading to the Uchan-Su waterfall. "Fabulous Oreanda palace, now in ruins, will stay with me forever. White marble pylons against the blue sea... for me it's a timeless symbol of Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically r ...

," Merezhkovsky wrote years later. Sergey Merezhkovsky, although a man of means, led an ascetic

Asceticism is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from worldly pleasures through self-discipline, self-imposed poverty, and simple living, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their pra ...

life, keeping his household 'lean and thrifty'. He saw this also as 'moral prophylactics' for his children, regarding luxury-seeking and reckless spending as the two deadliest sins. The parents traveled a lot, and an old German housekeeper, Amalia Khristianovna, spent much time with the children, amusing them with Russian fairytales and Biblical stories. It was her recounting of saints' lives that helped Dmitry to develop fervent religious feelings in his early teens.

In 1876 Dmitry Merezhkovsky joined an élite grammar school, the . His years spent there he described later in one word, "murderous", remembering just one teacher as a decent person – "Kessler the Latinist; well-meaning he surely never was, but at least had a kindly look." At thirteen Dmitry started writing poetry, rather in the vein of Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin () was a Russian poet, playwright, and novelist of the Romantic era.Basker, Michael. Pushkin and Romanticism. In Ferber, Michael, ed., ''A Companion to European Romanticism''. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005. He is conside ...

's "Bakhchisarai Fountain", as he later remembered. He became fascinated with the works of Molière

Jean-Baptiste Poquelin (; 15 January 1622 (baptised) – 17 February 1673), known by his stage name Molière (, ; ), was a French playwright, actor, and poet, widely regarded as one of the great writers in the French language and world liter ...

to such an extent as to form a Molière Circle in the Gymnasium. The group had nothing political in its agenda, but still aroused the interest of the secret police. Each of its members were summoned one by one to the Third Department's headquarters by the Politzeisky Bridge to be questioned. It is believed that only Sergey Merezhkovsky's efforts prevented his son from being expelled from the school.

Debut

Much as Dmitry disliked his tight upper-lipped, stone-faced father, later he had to give him credit for being the first one to have noticed and, in his emotionless way, appreciate his first poetic exercises. In July 1879, inAlupka

Alupka (Ukrainian language, Ukrainian and Russian language, Russian: ; ; , Alòpex) is a resort city located in the Crimea, Crimean peninsula, a territory of Ukraine currently annexed by Russian Federation (see 2014 Crimean crisis). It is located ...

, Crimea, Sergey Ivanovich introduced Dmitry to the legendary Princess Yekaterina Vorontzova, once Pushkin's sweetheart. The grand dame admired the boy's verses: she (according to a biographer) "spotted in them a must-have poetic quality: the metaphysical sensitivity of a young soul" and encouraged him to soldier on. Somewhat different was young Merezhkovsky's encounter with another luminary, Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist and journalist. He is regarded as one of the greatest novelists in both Russian literature, Russian and world literature, and many of his works are consider ...

, again staged by his well-connected father. As the boy started reciting his work, nervous to the point of stuttering, the famous novelist listened rather impatiently, then said: "Poor, very poor. To write well, one has to suffer. Suffer!" – "Oh no, I'd rather he won't – either suffer, or write well!", the appalled father exclaimed. The boy left Dostoyevsky's house much frustrated by the great man's verdict. Merezhkovsky's debut publication followed the same year: the Saint Petersburg magazine '' Zhivopisnoe obozrenie'' published two of his poems, "Little Cloud" and "The Autumn Melody". A year later another poem, "Narcissus", was included in a charity compilation benefiting destitute students, edited by Pyotr Yakubovich

Pyotr Filippovich Yakubovich (; – ) was a Russian revolutionary, poet and member of Narodnaya Volya (People's Will Party) during the 1880s.

Biography

Pyotr Yakubovich was born on in landed property Isaevo, Valdaysky Uyezd, Novgorod Gover ...

.

In autumn 1882 Merezhkovsky attended one of the first of Semyon Nadson

Semyon Yakovlevich Nadson (; 14 December 1862 – 19 January 1887) was a Russian poet and essayist. He is noted for being the first Jewish poet to achieve national fame in the Russian Empire.

Biography

Nadson's father was a Jew who converted to ...

's public readings and, deeply impressed, wrote him a letter. Soon Nadson became Merezhkovsky's closest friend – in fact, the only one, apart from his mother. Later researchers suggested there was some mystery shared by the two young men, something to do with "fatal illness, fear of death and longing for faith as an antidote to such fear". Nadson died in 1887, Varvara Vasilyevna two years later; feeling that he had lost everything he'd ever had in this world, Merezhkovsky submerged into deep depression.

In January 1883 ''Otechestvennye Zapiski

''Otechestvennye Zapiski'' ( rus, Отечественные записки, p=ɐˈtʲetɕɪstvʲɪnːɨjɪ zɐˈpʲiskʲɪ, variously translated as "Annals of the Fatherland", "Patriotic Notes", "Notes of the Fatherland", etc.) was a Russian lit ...

'' published two more of Merezhkovsky's poems. "Sakya Muni", the best known of his earlier works, entered popular poetry-recital compilations of the time and made the author almost famous. By 1896 Merezhkovsky was rated as "a well-known poet" by the ''Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary

The ''Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopaedic Dictionary'' (35 volumes, small; 86 volumes, large) is a comprehensive multi-volume encyclopaedia in Russian. It contains 121,240 articles, 7,800 images, and 235 maps.

It was published in the Russian Em ...

''. Years later, having gained fame as a novelist, he felt embarrassed by his poetry and, when compiling his first ''Complete'' series in the late 1900s, cut the poetry section down to several pieces. Nevertheless, Merezhkovsky's poems remained popular, and some major Russian composers, Rachmaninoff

Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff; in Russian pre-revolutionary script. (28 March 1943) was a Russian composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor. Rachmaninoff is widely considered one of the finest pianists of his day and, as a composer, one of ...

and Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer during the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music made a lasting impression internationally. Tchaikovsky wrote some of the most popular ...

among them, have set dozens of them to music.

University years

From 1884 to 1889 Merezhkovsky studied history andphilology

Philology () is the study of language in Oral tradition, oral and writing, written historical sources. It is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics with strong ties to etymology. Philology is also de ...

at the University of Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg State University (SPBGU; ) is a public research university in Saint Petersburg, Russia, and one of the oldest and most prestigious universities in Russia. Founded in 1724 by a decree of Peter the Great, the university from the be ...

where his PhD thesis was on Montaigne

Michel Eyquem, Seigneur de Montaigne ( ; ; ; 28 February 1533 – 13 September 1592), commonly known as Michel de Montaigne, was one of the most significant philosophers of the French Renaissance. He is known for popularising the essay as ...

. He learned several foreign languages and developed strong interests in French literature

French literature () generally speaking, is literature written in the French language, particularly by French people, French citizens; it may also refer to literature written by people living in France who speak traditional languages of Franc ...

, the philosophy of positivism

Positivism is a philosophical school that holds that all genuine knowledge is either true by definition or positivemeaning '' a posteriori'' facts derived by reason and logic from sensory experience.John J. Macionis, Linda M. Gerber, ''Soci ...

, and the theories of John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, politician and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of liberalism and social liberalism, he contributed widely to s ...

and Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

. Still, his student years were joyless. "University gave me no more than a Gymnasium did. I've never had proper – either family, or education," he wrote in his 1913 autobiography. The only lecturer he remembered fondly was the historian of literature Orest Miller

Orest Fyodorovich Miller (; 4 August 1833 – 1 June 1889) was a Russian folklorist, professor in Russian literature, of Baltic German origin from Estonia. He is the author of the book''Илья Муромец и богатырство киевск ...

, who held a domestic literature circle.

In 1884 Merezhkovsky (along with Nadson) joined the Saint Petersburg's Literary Society, on Aleksey Pleshcheyev

Aleksey Nikolayevich Pleshcheyev (; 8 October 1893) was a radical Russian poet of the 19th century, once a member of the Petrashevsky Circle.

Pleshcheyev's first book of poetry, published in 1846, made him famous: "Step forward! Without fear or ...

's recommendation. The latter introduced the young poet to the family of Karl Davydov

Karl Yulievich Davydov (; ) was a Russian cellist, described by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky as the "czar of cellists". He was also a composer, mainly for the cello. His name also appears in various different spellings: Davydov, Davidoff, Davidov, an ...

, head of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory

The N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov Saint Petersburg State Conservatory () (formerly known as the Petrograd Conservatory and Leningrad Conservatory) is a school of music in Saint Petersburg, Russia. In 2004, the conservatory had around 275 faculty member ...

. Davydov's wife became Merezhkovsky's publisher in the 1890s; their daughter Lidia () became his first (strong, even if fleeting) romantic interest. In Davydov's circle Merezhkovsky mixed with well-established literary figures of the time – Ivan Goncharov

Ivan Aleksandrovich Goncharov ( , ; rus, Ива́н Алекса́ндрович Гончаро́в, r=Iván Aleksándrovich Goncharóv, p=ɪˈvan ɐlʲɪkˈsandrəvʲɪdʑ ɡənʲtɕɪˈrof; – ) was a Russian novelist best known for his n ...

, Apollon Maykov

Apollon Nikolayevich Maykov (, , Moscow – , Saint Petersburg) was a Russian poet, best known for his lyric verse showcasing images of Russian villages, nature, and history. His love for ancient Greece and Rome, which he studied for much of his ...

, Yakov Polonsky

Yakov Petrovich Polonsky (; ) was a leading Pushkinist poet who wrote poems faithful to the traditions of Russian Romantic poetry during the heyday of realistic prose.

Of noble birth, Polonsky attended the Moscow University, where he befriended ...

, but also Nikolay Mikhaylovsky

Nikolay Konstantinovich Mikhaylovsky (; – ) was a Russian literary critic, sociologist, writer on public affairs, and one of the theoreticians of the Narodniki movement.

Biography

The school of thinkers he belonged to became famous in the ...

and Gleb Uspensky

Gleb Ivanovich Uspensky (; October 25, 1843 April 6, 1902) was a Russian writer and a prominent figure of the Narodnik movement.

Biography Early life

Gleb Uspensky was born in Tula, Russia, Tula, the son of Ivan Yakovlevich Uspensky, a senior o ...

, two prominent narodnik

The Narodniks were members of a movement of the Russian Empire intelligentsia in the 1860s and 1870s, some of whom became involved in revolutionary agitation against tsarism. Their ideology, known as Narodism, Narodnism or ,; , similar to the ...

s whom he regarded later as his first real teachers.

It was under the guidance of the latter that Merezhkovsky, while still a university student, embarked upon an extensive journey through the Russian provinces where he met many people, notably religious cult leaders. He stayed for some time in the village of Chudovo

Chudovo () is the name of several inhabited localities in Russia.

;Urban localities

*Chudovo, Chudovsky District, Novgorod Oblast, a town of district significance in Chudovsky District of Novgorod Oblast

;Rural localities

* Chudovo, Semyonov, N ...

where Uspensky lived, and both men spent many sleepless nights discussing things like "life's religious meaning," "a common man's cosmic vision" and "the power of the land". At the time Merezhkovsky was seriously considering leaving the capital to settle down in some far-out country place and to become a teacher.

Another big influence was Mikhaylovsky, who introduced the young man to the staff of ''Severny Vestnik

''Severny Vestnik'' (, ) was an influential Russian literary magazine founded in Saint Petersburg in 1885 by Anna Yevreinova, who stayed with it until 1889.

History

In the early years ''Severny Vestnik'' was the Narodnik's stable; after ''Otech ...

'', a literary magazine he founded with Davydova. Here Merezhkovsky met Vladimir Korolenko

Vladimir Galaktionovich Korolenko (, ; 27 July 1853 – 25 December 1921) was a Russian writer, journalist and humanitarian of Ukrainian origin. His best-known work includes the short novel '' The Blind Musician'' (1886), as well as numerous shor ...

and Vsevolod Garshin

Vsevolod Mikhailovich Garshin (; 14 February 1855 – 5 April 1888) was a Russian author of short stories.

Life

Garshin was the son of an officer, from a family tracing its roots back to a 15th-century prince, who entered into the service of I ...

, and later Nikolai Minsky

Nikolai Minsky and Nikolai Maksimovich Minsky () are pseudonyms of Nikolai Maksimovich Vilenkin (Виле́нкин; 1855–1937), a mystical writer and poet of the Silver Age of Russian Poetry.

Early life and education

Born in Glubokoe (now Hly ...

, Konstantin Balmont

Konstantin Dmitriyevich Balmont ( rus, Константи́н Дми́триевич Ба́льмо́нт, p=, a=Konstantin Dmitriyevich Bal'mont.ru.vorb.oga; – 23 December 1942) was a Russian symbolist poet and translator who became one of ...

and Fyodor Sologub

Fyodor Sologub (, born Fyodor Kuzmich Teternikov, , also known as Theodor Sologub; – 5 December 1927) was a Russian Symbolist poet, novelist, translator, playwright and essayist. He was the first writer to introduce the morbid, pessimistic e ...

: the future leaders of the Russian Symbolist movement. Merezhkovsky's first article for the magazine, "A Peasant in the French literature", upset his mentor: Mikhaylovsky spotted in his young protégé the "penchant for mysticism", something he himself was averse to.

In early 1888 Merezhkovsky graduated from the University and embarked upon a tour through southern Russia, starting in Odessa

ODESSA is an American codename (from the German language, German: ''Organisation der ehemaligen SS-Angehörigen'', meaning: Organization of Former SS Members) coined in 1946 to cover Ratlines (World War II aftermath), Nazi underground escape-pl ...

. In Borjomi

Borjomi ( ka, ბორჯომი ) is a resort town in south-central Georgia with a population of 11,173 (as of 2024). Located 165 km from Tbilisi, it is one of the six municipalities of the Samtskhe–Javakheti region and is situated in the ...

he met 19-year-old poet Zinaida Gippius

Zinaida Nikolayevna Gippius (; – 9 September 1945), a Russian poet, playwright, novelist, editor and religious thinker, became one of the major figures in Russian symbolism.

She began writing at an early age, and by the time she met Dmitry ...

. The two fell in love and on January 18, 1889, married in Tiflis

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი, ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), ( ka, ტფილისი, tr ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Georgia (country), largest city of Georgia ( ...

, making arguably the most prolific and influential couple in the history of Russian literature. Soon husband and wife moved into their new Saint Petersburg house, Merezkovsky's mother's wedding-present.

Late 1880s to early 1890s

Merezhkovsky's major literary debut came with the publication of ''Poems (1883–1887)'' in 1888. It brought the author into the focus of the most favourable critical attention, but – even coupled with ''Protopop Avvacum'', a poetry epic released the same year, could not solve the young family's financial problems. Helpfully, Gippius reinvented herself as a prolific fiction-writer, producing novels and novelettes with such ease that she later struggled to remember their names. Sergey Merezhkovsky's occasional hand-outs also helped the husband and wife to keep their meagre budget afloat. Having by this time lost interest in poetry, Dmitry Merezhkovsky developed a strong affinity toGreek drama

A theatrical culture flourished in ancient Greece from 700 BC. At its centre was the city-state of Athens, which became a significant cultural, political, and religious place during this period, and the theatre was institutionalised there as par ...

and published translations of Aeschylus

Aeschylus (, ; ; /524 – /455 BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek Greek tragedy, tragedian often described as the father of tragedy. Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work, and understanding of earlier Greek tragedy is large ...

, Sophocles

Sophocles ( 497/496 – winter 406/405 BC)Sommerstein (2002), p. 41. was an ancient Greek tragedian known as one of three from whom at least two plays have survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or contemporary with, those ...

and Euripides

Euripides () was a Greek tragedy, tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient scholars attributed ninety-five plays to ...

in ''Vestnik Evropy''.

These translations from Ancient Greek, including his later work on ''Daphnis and Chloe'' (prose version, 1896), though largely overlooked by contemporary critics, later came to be regarded as "the pride of the Russian school of classical translation", according to biographer Yuri Zobnin.

In the late 1880s Merezhkovsky debuted as a literary critic with an essay on Anton Chekhov

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (; ; 29 January 1860 – 15 July 1904) was a Russian playwright and short-story writer, widely considered to be one of the greatest writers of all time. His career as a playwright produced four classics, and his b ...

entitled "A Newly-born Talent Facing the Same Old Question" and published by ''Severny Vestnik''. Having spotted in his subject's prose "the seeds of irrational, alternative truth", Merezhkovsky inadvertently put an end to his friendship with Mikhaylovsky and amused Chekhov who, in his letter to Pleshcheev, mentioned the "disturbing lack of simplicity" as the article's major fault.Zobnin, p. 402 Merezhkovsky continued in the same vein and thus invented (in retrospect) the whole new genre of a philosophical essay as a form of critical thesis, something unheard of in Russian literature before. Merezhkovsky's biographical pieces on Pushkin, Dostoyevsky, Goncharov, Maykov, Korolenko, Pliny, and Calderon scandalized the contemporary literary establishment. Later, compiled in a volume called ''The Eternal Companions'', these essays were pronounced modern classics, their author praised as "the subtlest and the deepest of late XIX – early XX Russian literary critics" by literary historian Arkady Dolinin. ''The Eternal Companions'' became so revered a piece of literary art in the early 1910s that the volume was officially chosen as an honorary gift for excelling grammar-school graduates.

In May 1890

In May 1890 Liubov Gurevich

Liubov Yakovlevna Gurevich (; November 1, 1866, Saint Petersburg – October 17, 1940, Moscow) was a Russian editor, translator, author, and critic. She has been described as "Russia's most important woman literary journalist." From 1894 to 1917 s ...

, the new head of the revamped ''Severny Vestnik'', turned a former narodnik's safe haven into the exciting club for members of the rising experimental-literature scene, labeled "decadent" by detractors. Merezhkovsky's new drama ''Sylvio'' was published there, the translation of Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic who is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales involving mystery and the macabre. He is widely re ...

's "The Raven" followed suit. Other journals became interested in the young author too: ''Russkaya Mysl

''Russian Mind'' (; French – ''La Pensée Russe'') is a pan-European sociopolitical and cultural magazine, published on a monthly basis both in Russian and in English. The modern edition follows the traditions of the magazine laid down in 1880 ...

'' published his poem ''Vera'' (later included in his ''The Symbols'' compilation), hailed as one of Russian Symbolism's early masterpieces, its colourful mysticism providing a healthy antidote to narodniks' "reflections" of the social life. Bryusov "absolutely fell in love with it," and Pyotr Pertsov

Pyotr Petrovich Pertsov (Пётр Петрович Перцов, 16 June 1868 — 19 May 1947) was a Russian poet, publisher, editor, literary critic, journalist and memoirist associated with the Russian Symbolist movement.

Biography

Pyotr Pet ...

years later admitted: "For my young mind Merezhkovsky's ''Vera'' sounded so much superior to this dull and old-fashioned Pushkin".

''Russkaya Mysl'' released ''The Family Idyll'' (Semeynaya idillia, 1890); a year later another symbolic poem, ''Death'' (Smert), appeared in ''Severny Vestnik''. In 1891 Merezhkovsky and Gippius first travelled to Western Europe together, staying mostly in Italy and France; the poem ''End of the Century'' () inspired by the European trip, came out two years later. On their return home the couple stayed for a while in Guppius' dacha at Vyshny Volochyok

Vyshny Volochyok ( rus, Вы́шний Волочёк, p=ˈvɨʂnʲɪj vəlɐˈtɕɵk) is a town in Tver Oblast, Russia. Population:

Geography and etymology

The town is located northwest of Tver, in the Valdai Hills, between the Tvertsa and ...

; it was here that Merezhkovsky started working on his first novel, '' The Death of the Gods. Julian the Apostate''. A year later it was finished, but by this time the situation with ''Severny Vestnik'' had changed: outraged by Akim Volynsky

Akim Lvovich Volynsky (Аким Львович Волынский, real name Khaim Leybovich Flekser, Хаим Лейбович Флексер; 3 May 1861 – 6 July 1926) was a Russian literary (later theatre and ballet) critic and historian, o ...

's intrusive editorial methods, Merezhkovsky severed ties with the magazine, at least for a while. In the late 1891 he published his translation of Sophocles' ''Antigone'' in ''Vestnik Evropy'', part of Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

's ''Faustus'' (in ''Russkoye Obozrenye'') and Euripides' ''Hyppolite'' (in ''Vestnik Evropy'' again). The latter came out in 1893, after the couple's second trip to Europe where they first encountered Dmitry Filosofov

Dmitry Vladimirovich Filosofov (; – 4 August 1940) was a Russian author, essayist, literary critic, religious thinker, newspaper editor and political activist, best known for his role in the influential early 1900s ''Mir Iskusstva'' circle and ...

. Merezhkovsky's vivid impressions of Greece and a subsequent spurt of new ideas provided the foundation for his second novel.

The Symbolism manifestos

In 1892 Merezhkovsky's second volume of poetry, entitled ''Symbols. Poems and Songs'', came out. The book, bearing the influences ofEdgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic who is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales involving mystery and the macabre. He is widely re ...

and Charles Baudelaire

Charles Pierre Baudelaire (, ; ; 9 April 1821 – 31 August 1867) was a French poet, essayist, translator and art critic. His poems are described as exhibiting mastery of rhythm and rhyme, containing an exoticism inherited from the Romantics ...

as well as the author's newly-found religious ideas, became a younger readership's favourite. Of the elder writers only Yakov Polonsky supported it wholeheartedly. In October 1892 Merezhkovsky's lecture "The Causes of the Decline of the Contemporary Russian Literature and the New Trends in it" was first read in public, then came out in print. Brushing aside the 'decadent' tag, the author argued that all three "streaks of Modern art" – "Mystic essence, Symbolic language and Impressionism" – could be traced back to the works of Lev Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using pre-reform Russian orthography. ; ), usually referr ...

or of Dostoyevsky, making Russian Modernism, therefore, a continuation of Russian literature's classic tradition. Coupled with ''Symbols'', the lecture was widely accepted as Russian symbolism's early manifesto. The general reaction to it was mostly negative. The author found himself between two fires: liberals condemned his ideas as "the new obscurantism", members of posh literary salons treated his revelations with scorn. Only one small group of people greeted "The Causes" unanimously, and that was the staff of ''Severny Vestnik'', which welcomed him back.

In 1893–1894 Merezhkovsky published numerous books (the play ''The Storm is Over'' and the translation of Sophocles

Sophocles ( 497/496 – winter 406/405 BC)Sommerstein (2002), p. 41. was an ancient Greek tragedian known as one of three from whom at least two plays have survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or contemporary with, those ...

' ''Oedipus the King'' among them), but the money all this hard work brought were scant. Now writing his second novel, he had to accept whatever work was offered to him. In the late 1893 Merezhkovskys settled in Saint Petersburg again. Here they frequented the Shakespearean Circle, the Polonsky's Fridays and the Literary Fund gatherings. Then the pair started their own home salon with Filosofov and Akim Volynsky

Akim Lvovich Volynsky (Аким Львович Волынский, real name Khaim Leybovich Flekser, Хаим Лейбович Флексер; 3 May 1861 – 6 July 1926) was a Russian literary (later theatre and ballet) critic and historian, o ...

becoming habitués. All of a sudden Merezhkovsky found that his debut novel was to be published in ''Severny Vestnik'' after all. What he didn't realise was that this came as a result of a Gippius' tumultuous secret love affair with Akim Volynsky

Akim Lvovich Volynsky (Аким Львович Волынский, real name Khaim Leybovich Flekser, Хаим Лейбович Флексер; 3 May 1861 – 6 July 1926) was a Russian literary (later theatre and ballet) critic and historian, o ...

, one of this magazine's chiefs.

1895–1903

''The Death of the Gods'' which came out in 1895 (''Severny Vestnik'', Nos.1–6) opened the ''Christ & Antichrist'' trilogy and in retrospect is regarded as the first Russian symbolist novel. Sceptics prevailed (most of them denouncing the author's alleged

''The Death of the Gods'' which came out in 1895 (''Severny Vestnik'', Nos.1–6) opened the ''Christ & Antichrist'' trilogy and in retrospect is regarded as the first Russian symbolist novel. Sceptics prevailed (most of them denouncing the author's alleged Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche became the youngest pro ...

anity), but the allies were ecstatic. "A novel made for eternity," Bryusov marveled. Five years later ''Julian the Apostate'' was published in France, translated by Zinaida Vasilyeva.

Merezhkovsky's relationship with ''Severny Vestnik'', though, again started to deteriorate, the reason being Akim Volynsky

Akim Lvovich Volynsky (Аким Львович Волынский, real name Khaim Leybovich Flekser, Хаим Лейбович Флексер; 3 May 1861 – 6 July 1926) was a Russian literary (later theatre and ballet) critic and historian, o ...

's jealousy. In 1896 all three of them (husband still unaware of what was going on behind his back) made a trip to Europe to visit Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 1452 - 2 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially rested o ...

's places. Several ugly rows with Volynsky finally prompted Gippius to send her scandalous-minded lover home. Volynsky reacted by expelling his ex-lover's husband from ''Severny Vestnik'' (some sources say it was the Merezhkovskys who withdraw their cooperation with the "Severny Vestnik" a year before the magazine shut down in 1898, along with Minsky and Sologub), made sure the major literary journals would shut the door on him and published (in 1900) under his own name a monograph ''Leonardo da Vinci'', written and compiled by his adversary.

The scandal concerning plagiarism lasted for almost two years. Feeling sick and ignored, Merezhkovsky in 1897 was seriously considering leaving his country for good, being kept at home only by the lack of money. For almost three years the second novel, '' Resurrection of Gods. Leonardo da Vinci'' (''The Romance of Leonardo da Vinci'' – in English and French) remained unpublished. It finally appeared in Autumn 1900 in ''Mir Bozhy

''Mir Bozhiy'' (God's World, Мир божий) was a Russian monthly magazine published in Saint Petersburg in 1892–1906. It was edited first by Viktor Ostrogorsky (1892–1901), then by Fyodor Batyushkov (1902–1906). In July 1906 ''Mir Bozhi ...

'' under the title "The Renaissance". In retrospect these two books' "...persuasive power came from Merezhkovsky's success in catching currents then around him: strong contrasts between social life and spiritual values, fresh interest in the drama of pagan ancient Athens, and identification with general western European culture."

By the time of his second novel's release Merezhkovsky was in a different cultural camp – that of Dyagilev and his close friends – Alexandre Benois

Alexandre (Alexander) Nikolayevich Benois (; Salmina-Haskell, Larissa. ''Russian Paintings and Drawings in the Ashmolean Museum''. pp. 15, 23-24. Published by Ashmolean Museum, 19899 February 1960) was a Russian artist, art critic, historian, ...

, Léon Bakst

Léon (Lev) Samoylovich Bakst (), born Leyb-Khaim Izrailevich Rosenberg (; – 27 December 1924),

, Nikolay Minsky and Valentin Serov

Valentin Alexandrovich Serov (; – 5 December 1911) was a Russian painter and one of the premier portrait artists of his era.

Life and work

Youth and education

Serov was born in Saint Petersburg, son of the Russian composer and music crit ...

. Their own brand new ''Mir Iskusstva

''Mir iskusstva'' ( rus, «Мир искусства», p=ˈmʲir ɪˈskustvə, ''World of Art'') was both a Russian magazine and the artistic movement it fostered, playing a significant role in shaping the Russian avant-garde. The movement was d ...

'' (World of Art) magazine, with Dmitry Filosofov as a literary editor, accepted Merezhkovsky wholeheartedly. It was here that his most famous essay, '' L. Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky'' was published in 1900–1901, coinciding with the escalation of Tolstoy's conflict with the Russian Orthodox church

The Russian Orthodox Church (ROC; ;), also officially known as the Moscow Patriarchate (), is an autocephaly, autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox Christian church. It has 194 dioceses inside Russia. The Primate (bishop), p ...

. Tolstoy invited the couple to his Yasnaya Polyana

Yasnaya Polyana ( rus, Я́сная Поля́на, p=ˈjasnəjə pɐˈlʲanə, ) is a writer's house museum, the former home of the writer Leo Tolstoy.#Bartlett, Bartlett, p. 25 It is southwest of Tula, Russia, Tula, Russia, and from Moscow. ...

estate in 1904 and, to both parties' delight, the visit proved to be friendly. Behind the facade, there was little love lost between them; the old man confessed in his diary that, he just couldn't "force himself to love those two," and Merezhkovsky's critique of what he saw as "Tolstoy's nihilism

Nihilism () encompasses various views that reject certain aspects of existence. There have been different nihilist positions, including the views that Existential nihilism, life is meaningless, that Moral nihilism, moral values are baseless, and ...

" continued.

The ''God-seekers'' and ''Troyebratstvo''

In the early 1900s Merezhkovskys formed the group called the Religious-Philosophical Meetings (1901–1903) based on the concept of the New Church which was suggested by Gippius and supposed to become an alternative to the old Orthodox doctrine, "...imperfect and prone to stagnation." The group, organized by Merezhkovsky and Gippius along withVasily Rozanov

Vasily Vasilievich Rozanov (; – 5 February 1919) was one of the most controversial Russian writers and important philosophers among the symbolists of the pre-revolutionary epoch.

Views

Rozanov tried to reconcile Christian teachings with ...

, Viktor Mirolyubov

Viktor Sergeyevich Mirolyubov (, 22 January 1860, in Moscow, Russian Empire – 26 October 1939, in Leningrad, USSR) was a Russian journalist, editor and publisher. Having started out as an opera singer (who up until 1897 performed, as V.Mirov, ...

and Valentin Ternavtsev

Valentin Alexandrovich Ternavtsev (; 27 February 1866 in Melitopol, Tavria Governorate, Russian Empire (modern Ukraine) – 28 August 1940 in Serpukhov, Moskovskaya Oblast, USSR) was a Russian author, publisher and religious activist, one of the o ...

, claimed to provide "a tribune for open discussion of questions concerning religious and cultural problems," serving to promote "neo-Christianity, social organization and whatever serves perfecting the human nature." Having lost by this time contacts with both ''Mir Iskusstva'' and ''Mir Bozhy'', Merezhkovskys felt it was time for them to create their own magazine, as a means for "bringing the thinking religious community together." In July 1902, in association with Pyotr Pertsov and assisted by some senior officials including ministers Dmitry Sipyagin

Dmitry Sergeyevich Sipyagin (; – ) was a Russian politician.

Political career

Born in Kiev, Sipyagin graduated from the Judicial Department of St Petersburg University in 1876. Served in the MVD as Vice Governor of Kharkov Governorate ( ...

and Vyacheslav von Plehve

Vyacheslav Konstantinovich von Plehve ( rus, Вячесла́в Константи́нович фон Пле́ве, p=vʲɪtɕɪˈslaf kənstɐnʲˈtʲinəvʲɪtɕ fɐn ˈplʲevʲɪ; – ) was a Russian politician who served as the directo ...

, they opened their own ''Novy Put

''Novy Put'' (Но′вый путь, New Way) was a Russian religious, philosophical and literary magazine, founded in 1902 in Saint Petersburg by Dmitry Merezhkovsky and Zinaida Gippius. Initially a literary vehicle for the Religious and Philos ...

'' (New Path) magazine, designed as an outlet for The Meetings.

After the 22nd session, in April 1903, the Meetings of the group (by this time known as ''Bogoiskateli'', or God-seekers) were cancelled by the procurator of the

After the 22nd session, in April 1903, the Meetings of the group (by this time known as ''Bogoiskateli'', or God-seekers) were cancelled by the procurator of the Holy Synod

In several of the autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Churches and Eastern Catholic Churches, the patriarch or head bishop is elected by a group of bishops called the Holy Synod. For instance, the Holy Synod is a ruling body of the Georgian Orthodox ...

of the Russian Orthodox Church Konstantin Pobedonostsev

Konstantin Petrovich Pobedonostsev ( rus, Константи́н Петро́вич Победоно́сцев, p=kənstɐnʲˈtʲin pʲɪˈtrovʲɪtɕ pəbʲɪdɐˈnostsɨf; 30 November 1827 – 23 March 1907) was a Russian jurist and states ...

's decree, the main reason being Merezhkovsky's frequent visits to places of mass sectarian

Sectarianism is a debated concept. Some scholars and journalists define it as pre-existing fixed communal categories in society, and use it to explain political, cultural, or religious conflicts between groups. Others conceive of sectarianism a ...

settlements where God-seekers' radical ideas of Church 'renovation' were becoming popular. In ''Novy Put'' things changed too: with the arrival of strong personalities like Nikolai Berdyayev

Nikolai Alexandrovich Berdyaev (; ; – 24 March 1948) was a Russian philosopher, theologian, and Christian existentialist who emphasized the existential spiritual significance of human freedom and the human person.

Biography

Nikolai Be ...

, Sergey Bulgakov

Sergei Nikolayevich Bulgakov (, ; – 13 July 1944) was a Russian Orthodox theologian, priest, philosopher, and economist. Orthodox writer and scholar David Bentley Hart has said that Bulgakov was "the greatest systematic theologian of the twen ...

and Semyon Frank

Semyon Lyudvigovich Frank (; 28 January 1877 – 10 December 1950) was a Russian philosopher. Born into a Jewish family, he became an Orthodox Christian in 1912. In 1922 he was expelled from Soviet Russia and lived in Berlin. In 1933 he was r ...

the magazine solidified its position, yet drifted away from its originally declared mission. In the late 1904 Merezhkovsky and Gippius quit ''Novy Put'', remaining on friendly terms with its new leaders and their now highly influential 'philosophy section'. In 1907 the Meetings revived under the new moniker of The Religious-Philosophical Society, Merezhkovsky once again promoting his 'Holy Ghost's Kingdom Come' ideas. This time it looked more like a literary circle than anything it had ever purported to be.

The couple formed their own domestic "church", trying to involve ''miriskusniks''. Of the latter, only Filosofov took the idea seriously and became the third member of the so-called ''Troyebratstvo'' (The Brotherhood of Three) built loosely upon the Holy Trinity

The Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the Christian doctrine concerning the nature of God, which defines one God existing in three, , consubstantial divine persons: God the Father, God the Son (Jesus Christ) and God the Holy Spirit, three ...

format and having to do with the obscure 12th century idea of the Third Testament. Merezhkovsky developed it into the ''Church of the Holy Ghost

Most Christian denominations believe the Holy Spirit, or Holy Ghost, to be the third divine Person of the Trinity, a triune god manifested as God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit, each being God. Nontrinitarian Christians, who ...

'', destined to succeed older churches – first of the Father (Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

), then of the Son (New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

). The services at ''Troyebratstvo'' (with the traditional Russian Orthodox elements organized into a bizarre set of rituals) were seen by many as blasphemy

Blasphemy refers to an insult that shows contempt, disrespect or lack of Reverence (emotion), reverence concerning a deity, an object considered sacred, or something considered Sanctity of life, inviolable. Some religions, especially Abrahamic o ...

and divided the St. Petersburg intellectual elite: Vasily Rozanov

Vasily Vasilievich Rozanov (; – 5 February 1919) was one of the most controversial Russian writers and important philosophers among the symbolists of the pre-revolutionary epoch.

Views

Rozanov tried to reconcile Christian teachings with ...

was fascinated by the thinly veiled eroticism of the happening, Nikolai Berdyaev was among those outraged by the whole thing, as were the (gay, mostly) members of ''Mir Iskusstva''. Sergei Diaghilev

Sergei Pavlovich Diaghilev ( ; rus, Серге́й Па́влович Дя́гилев, , sʲɪrˈɡʲej ˈpavləvʲɪdʑ ˈdʲæɡʲɪlʲɪf; 19 August 1929), also known as Serge Diaghilev, was a Russian art critic, patron, ballet impresario an ...

accused Filosofov of committing 'adultery'. The latter in 1905 settled down in Merezhkovskys' St. Petersburg house, becoming virtually a family member.

In 1904 '' Peter and Alexis'', the third and final novel of ''Christ and Antichrist'' trilogy was published (in ''Novy Put'', Nos. 1–5, 9–12), having at its focus the figure of Peter the Great

Peter I (, ;

– ), better known as Peter the Great, was the Sovereign, Tsar and Grand Prince of all Russia, Tsar of all Russia from 1682 and the first Emperor of Russia, Emperor of all Russia from 1721 until his death in 1725. He reigned j ...

as an "embodied Antichrist" – an idea the author shared with Russian ''raskol

The Schism of the Russian Church, also known as (, , meaning 'split' or 'schism'), was the splitting of the Russian Orthodox Church into an official church and the Old Believers movement in the 1600s. It was triggered by the reforms of Patria ...

niki''. The novel's release was now eagerly anticipated in Europe where Merezhkovsky by this time has become a best-selling author, ''Julian the Apostate'' having undergone ten editions (in four years) in France. But when ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a British daily broadsheet conservative newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed in the United Kingdom and internationally. It was found ...

'' described the novelist as "an heir to Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky's legacy," back in Russia critics denounced this praise so unanimously that Merezhkovsky was forced to publicly deny having had any pretensions of this kind whatsoever.

1905–1908

After theBloody Sunday

Bloody Sunday may refer to:

Historical events Canada

* Bloody Sunday (1923), a day of police violence during a steelworkers' strike for union recognition in Sydney, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia

* Bloody Sunday (1938), police violence agai ...

of January 9, 1905, Merezhkovsky's views changed drastically, the defeat of the Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until being dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution and the declaration of ...

by the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, Potsdam Declaration, when it was dissolved followin ...

helping him see, as he put it, "the anti-Christian nature of the Russian monarchy." The 1905 Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905, also known as the First Russian Revolution, was a revolution in the Russian Empire which began on 22 January 1905 and led to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy under the Russian Constitution of 1906, t ...

was now seen by Merezhkovsky as a prelude for some kind of a religious upheaval he thought himself to be a prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divinity, divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings ...

of. The writer became an ardent supporter of the civil unrest, writing pro-revolutionary verse, organizing protest parties for students, like that in Alexandrinsky theatre

The Alexandrinsky Theatre () or National Drama Theatre of Russia is a theatre in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

The Alexandrinsky Theatre was built for the Imperial troupe of Petersburg (Imperial troupe was founded in 1756).

Since 1832, the theatre ...

. In October 1905 he greeted the government's 'freedoms-granting' decree but since then was only strengthening ties with leftist radicals, notably, esers

The Socialist Revolutionary Party (SR; ,, ) was a major socialist political party in the late Russian Empire, during both phases of the Russian Revolution, and in early Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Soviet Russia. The party memb ...

.

In ''The Forthcoming Ham '' (Gryadushchu Ham, 1905) Merezhkovsky explained his political stance, seeing, as usual, all things refracted into Trinities. Using the pun ("

In ''The Forthcoming Ham '' (Gryadushchu Ham, 1905) Merezhkovsky explained his political stance, seeing, as usual, all things refracted into Trinities. Using the pun ("Ham

Ham is pork from a leg cut that has been preserved by wet or dry curing, with or without smoking."Bacon: Bacon and Ham Curing" in '' Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes, 1961, Vol. 2, p. 39. As a processed meat, the term '' ...

" in Russian, along with a Biblical character's name, meaning 'lout', 'boor') the author described the three "faces of Ham'stvo" (son of Noah's new incarnation as kind of nasty, God-jeering scoundrel Russian): the past (Russian Orthodox Church's hypocrisy), the present (the state bureaucracy and monarchy) and the future – massive "boorish upstart rising up from society's bottom." Several years on the book was regarded as prophetic by many.

In spring 1906, Merezhkovsky and Filosofov went into a self-imposed European exile in order to promote what they termed "the new religious consciousness." In France they founded ''Anarchy and Theocracy'' magazine and released a compilation of essays called ''Le Tsar et la Revolution''.''Merezhkovsky. D.S.'Revolution and Religion

– russianway.rchgi.spb.ru. – 1907. In one of the articles he contributed to it, ''Revolution and Religion'', Merezhkovsky wrote: "Now it's almost impossible to foresee what a deadly force this revolutionary tornado starting upwards from the society's bottom will turn out to be. The church will be crashed down and the monarchy too, but with them – what if Russia itself is to perish – if not the timeless soul of it, then its body, the state?" Again, what at the time was looked upon as dull political grotesque a decade later turned into grim reality. In 1908 the play about "the routinous side of the revolution," ''Poppy Blossom'' (Makov Tzvet) came out, all three Troyebratstvo members credited as co-authors. It was followed by "The Last Saint" (), a study on

Seraphim Sarovsky

Seraphim of Sarov (; – ), born Prókhor Isídorovich Moshnín (Mashnín) �ро́хор Иси́дорович Мошни́н (Машни́н) is one of the most renowned Russian saints and is venerated in the Eastern Orthodox Church and the ...

, this time Merezhkovsky's own work. More significant were two of his socio-political/philosophical essays, "Not Peace But Sword" and "In Sill Waters". In them, working upon his concept of "the evolutionary mysticism," Merezhkovsky argued that revolution in both Russia and the rest of the world (he saw the two as closely linked: the first "steaming forward," the latter "rattling behind") was inevitable, but could succeed only if preceded by "the revolution of the human spirit," involving the Russian intelligentsia's embracing his idea of the Third Testament. Otherwise, Merezhkovsky prophesied, political revolution will bring nothing but tyranny and the "Kingdom of Ham."

Among people whom Merezhkovskys talked with in Paris were Anatole France

(; born ; 16 April 1844 – 12 October 1924) was a French poet, journalist, and novelist with several best-sellers. Ironic and skeptical, he was considered in his day the ideal French man of letters.Rudolf Steiner

Rudolf Joseph Lorenz Steiner (; 27 or 25 February 1861 – 30 March 1925) was an Austrian occultist, social reformer, architect, esotericist, and claimed clairvoyant. Steiner gained initial recognition at the end of the nineteenth century ...

, Bergson

Henri-Louis Bergson (; ; 18 October 1859 – 4 January 1941) was a French philosopher who was influential in the traditions of analytic philosophy and continental philosophy, especially during the first half of the 20th century until the S ...

, leaders of the French Socialists. Disappointed by the general polite indifference to their ideas, husband and wife returned home in the late 1908, but not before Merezhkovsky's historical drama '' Pavel the First'' (Pavel Pervy) was published. Confiscated and then banned by the Russian aut]horities, it became the first part of the trilogy ''The Kingdom of the Beast'' (). Dealing with the nature and history of the Russian monarchy, the trilogy had little in common with the author's earlier symbolism-influenced prose and, cast in the humanist tradition of the 19th-century Russian literature, was seen later as marking the peak of Merezhkovsky's literary career. The second and the third parts of the trilogy, the Decembrists

The Decembrist revolt () was a failed coup d'état led by liberal military and political dissidents against the Russian Empire. It took place in Saint Petersburg on , following the death of Emperor Alexander I.

Alexander's brother and heir ...

novels ''Alexander the First'' and ''December 14'' came out in 1913 and 1918 respectively.

1909–1913

In 1909 Merezhkovsky found himself in the center of another controversy after coming out with harsh criticism of '' Vekhi'', the volume of political and philosophical essays written and compiled by the group of influential writers, mostly his former friends and allies, who promoted their work as a manifesto, aiming to incite the inert Russian intelligentsia into the spiritual revival. Arguing against ''vekhovtsy''s idea of bringing Orthodoxy and the Russian intellectual elite together, Merezhkovsky wrote in an open letter to Nikolay Berdyaev:Orthodoxy is the very soul of the Russian monarchy, and monarchy is the Orthodoxy's carcass. Among things they both hold sacred are political repressions, the ltra-nationalistSome argued Merezhkovsky's stance was inconsistent with his own ideas of some five years ago. After all, the ''Vekhi'' authors were trying to revitalize his own failed project of bringing the intellectual and the religious elites into collaboration. But the times have changed for Merezhkovsky and – following this (some argued, unacceptably scornful) anti-''Vekhi'' tirade, his social status, too. Shunned by both former allies and the conservatives, he was hated by the Church:Union of Russian People The Union of the Russian People (URP) (; СРН/SRN) was a loyalist far-right nationalist political party, the most important among Black-Hundredist monarchist political organizations in the Russian Empire between 1905 and 1917. — p. 71–72. ..., the death penalty and meddling with other countries' international affairs. How can one entrust oneself to prayers of those whose actions one sees as God-less and demonic?

Saratov

Saratov ( , ; , ) is the largest types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and administrative center of Saratov Oblast, Russia, and a major port on the Volga River. Saratov had a population of 901,361, making it the List of cities and tow ...

Bishop Dolganov even demanded his excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to deprive, suspend, or limit membership in a religious community or to restrict certain rights within it, in particular those of being in Koinonia, communion with other members o ...

after the book ''Sick Russia '' was published in 1910. For the Social Democrats, conversely, Merezhkovsky, not a "decadent pariah" any-more, suddenly turned a "well-established Russian novelist" and the "pride of the European literature." Time has come for former friend Rozanov to write words that proved in the long run to be prophetic: "The thing is, Dmitry Sergeyevich, those whom you are with now, will never be with you. Never will you find it in yourself to wholly embrace this dumb, dull and horrible snout of the Russian revolution."

In the early 1910s Merezhkovsky moved to the left side of the Russian cultural spectrum, finding among his closest associates the esers Ilya Fondaminsky and, notably, Boris Savinkov

Boris Viktorovich Savinkov (; 31 January 1879 – 7 May 1925) was a Russian revolutionary, writer, and politician. As a leading figure in the Socialist Revolutionary Party's (SR) Combat Organization in the early 20th century, he was a key organ ...

. The latter was trying to receive from Merezhkovsky some religious and philosophical justification for his own terrorist ideology, but also had another, more down to Earth axe to grind, that of getting his first novel published. This he did, with Merezhkovsky's assistance – to strike the most unusual debut of the 1910 Russian literary season. In 1911 Merezhkovsky was officially accused of having links with terrorists. Pending trial (which included the case of ''Pavel Pervy'' play) the writer stayed in Europe, then crossed the border in 1912 only to have several chapters of ''Alexander the First'' novel confiscated. He avoided being arrested and in September, along with Pirozhkov, the publisher, was acquitted.

1913 saw Merezhkovsky involved in another public scandal, when Vasily Rozanov openly accused him of having ties with the "terrorist underground" and, as he put it, "trying to sell Motherland to Jews." Merezhkovsky suggested that the Religious and Philosophical Society should hold a trial and expel Rozanov from its ranks. The move turned to be miscalculated, the writer failing to take into account the extent of his own unpopularity within the Society. The majority of the latter declined the proposal. Rozanov, high-horsed, quit the Society on his own accord to respond stingingly by publishing Merezhkovsky's private letters so as to demonstrate the latter's hypocrisy on the matter.

1914–1919

1914–16

For a while in 1914 it looked as though Merezhkovsky would have his first ever relatively calm year. With the two ''Complete Works Of'' editions released by the Wolfe's and Sytin's publishing houses, academicNestor Kotlyarevsky

Nestor Alexandrovich Kotlyarevsky (Не′стор Алекса′ндрович Котляре′вский February 2, 1863, Moscow, Russian Empire, - May 12, 1925, Leningrad, USSR) was a Russian author, publicist, literary critic and historian. ...

nominated the author for the Nobel Prize for literature

The Nobel Prize in Literature, here meaning ''for'' Literature (), is a Swedish literature prize that is awarded annually, since 1901, to an author from any country who has, in the words of the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, "in t ...

. Then World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

broke out (July). The Merezhkovskys expressed their skepticism of Russian involvement in the war and of the patriotic hullabaloo stirred up by some intellectuals. The writer made a conscious effort to distance himself from politics and almost succeeded, but in 1915 was in it again, becoming friends with Alexander Kerensky

Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky ( – 11 June 1970) was a Russian lawyer and revolutionary who led the Russian Provisional Government and the short-lived Russian Republic for three months from late July to early November 1917 ( N.S.).

After th ...

and joining the Maxim Gorky

Alexei Maximovich Peshkov (; – 18 June 1936), popularly known as Maxim Gorky (; ), was a Russian and Soviet writer and proponent of socialism. He was nominated five times for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Before his success as an aut ...

-led Movement of the patriotic left calling for Russia's withdrawal from the war in the most painless possible way.

Two new plays by Merezhkovsky, ''Joy Will Come'' (Radost Budet) and ''The Romantics'' were staged in war-time Petrograd

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea. The city had a population of 5,601, ...

theaters. The latter proved a successful hit, but for the mainstream critics its playwright remained a "controversial author". "All in all, Russian literature is as hostile to me as it has always been. I could as well be celebrating the 25th anniversary of this hostility", the author wrote in his short autobiography for Semyon Vengerov

Semyon Afanasievich Vengerov (Russian: Семён Афана́сьевич Венге́ров; 17 April O. S. 5 April">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 5 April1855, Lubny, Poltava Governora ...

's biographical dictionary.

1917: February and October

1917 for the Merezhkovskys started with a bout of political activity: the couple's flat on Sergiyevskaya Street looked like a secret branch of RussianDuma

A duma () is a Russian assembly with advisory or legislative functions.

The term ''boyar duma'' is used to refer to advisory councils in Russia from the 10th to 17th centuries. Starting in the 18th century, city dumas were formed across Russia ...

(that was when the seeds of a rumour concerning the couple's alleged membership in the Russian freemason

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

community were sown). Merezhkovsky greeted the February anti-monarchy revolution and described the Kerensky-led Provisional government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, a transitional government or provisional leadership, is a temporary government formed to manage a period of transition, often following state collapse, revoluti ...

as "quite friendly". By the end of the spring he had become disillusioned with the government and its ineffective leader; in summer he began to speak of the government's inevitable fall and of a coming Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

tyranny. Late October saw Merezhkovsky's worst expectations coming to life.

Merezhkovsky viewed the October Socialist Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

of 1917 as a catastrophe. He saw it as the Coming of Ham

Ham is pork from a leg cut that has been preserved by wet or dry curing, with or without smoking."Bacon: Bacon and Ham Curing" in '' Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes, 1961, Vol. 2, p. 39. As a processed meat, the term '' ...

he wrote about a decade later, the tragic victory for, as he choose to put it, Narod-Zver (The Beast-nation), the political and social incarnation of universal Evil, putting the whole of human civilization in danger. Merezhkovsky and Gippius tried to use whatever influence they retained upon the Bolshevist cultural leaders to ensure the release of their friends, the arrested Provisional-government ministers. Ironically, one of the first things the Soviet government did was lift the ban from Merezhkovsky's anti-monarchist ''Pavel Pervy'' play, and it was staged in several of Red Russia's theaters.

1918–19

For a while the Merezhkovskys' flat served as anEser Eser may refer to:

* ESER, a German abbreviation for a Comecon computer standard

* Eser (name)

* Eser, a member of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party (from the Russian-language initialism SR)

* A member of A Just Russia party (from the Russian-lang ...

headquarters, but this came to an end in January 1918 when Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

dissolved the so-called ''Uchredilovka'' –the Russian Constituent Assembly

The All Russian Constituent Assembly () was a constituent assembly convened in Russia after the February Revolution of 1917. It met for 13 hours, from 4 p.m. to 5 a.m., , whereupon it was dissolved by the Bolshevik-led All-Russian Central Ex ...

. In his 1918 diary Merezhkovsky wrote:

In 1919, having sold everything including dishes and extra clothes, the Merezhkovskys started collaborating with Maxim Gorky's new , receiving a salary and food rations. "Russian Communists are not all of them villains. There are well-meaning, honest, crystal clear people among them. Saints, almost. These are the most horrible ones. These saints stink of the 'Chinese meat' most", Merezhkovsky wrote in his diary.

Many people found it inexplicable that amidst mass hunger with no agricultural farms functioning suddenly lots of fresh veal would appear from time to time at market places, sold invariably by the Chinese. This "veal" was widely believed to be human flesh: that of the "enemies of the revolution", executed in the Cheka

The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission ( rus, Всероссийская чрезвычайная комиссия, r=Vserossiyskaya chrezvychaynaya komissiya, p=fsʲɪrɐˈsʲijskəjə tɕrʲɪzvɨˈtɕæjnəjə kɐˈmʲisʲɪjə, links=yes), ...

basements.

After news started to filter through of the defeats suffered by the White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wa ...

forces of Yudenich

Nikolai Nikolayevich Yudenich (Russian: Николай Николаевич Юденич; – 5 October 1933) was a commander of the Russian Imperial Army during World War I. He was a leader of the anti-communist White movement in northwester ...

, Kolchak Kolchak, Kolçak or Kolčák is a surname from Turkish ''wikt:kolçak, kolçak''. Notable people with the surname include:

* Alexander Kolchak (1874–1920), Russian naval commander, head of anti-Bolshevik White forces

*Erkan Kolçak Köstendil, Tu ...

and Denikin

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (, ; – 7 August 1947) was a Russian military leader who served as the acting supreme ruler of the Russian State and the commander-in-chief of the White movement–aligned armed forces of South Russia during the Ru ...

in the course of the Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

of 1917–1922, the Merezhkovskys saw their only chance of survival in fleeing Russia. They left Petrograd on December 14, 1919, along with Filosofov and Zlobin (Gippius' young secretary), having obtained from Anatoly Lunacharsky

Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky (, born ''Anatoly Aleksandrovich Antonov''; – 26 December 1933) was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and the first Soviet People's Commissariat for Education, People's Commissar (minister) of Education, as well ...

signed permission "to leave Petrograd for the purpose of reading some lectures on Ancient Egypt to Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

fighters".

Merezhkovsky in exile

Merezkovsky, Gippius, Filosofov and Zlobin headed first forMinsk

Minsk (, ; , ) is the capital and largest city of Belarus, located on the Svislach (Berezina), Svislach and the now subterranean Nyamiha, Niamiha rivers. As the capital, Minsk has a special administrative status in Belarus and is the administra ...

, then Vilno

Vilnius ( , ) is the capital of and List of cities in Lithuania#Cities, largest city in Lithuania and the List of cities in the Baltic states by population, most-populous city in the Baltic states. The city's estimated January 2025 population w ...

, staying in both cities to give newspaper interviews and public lectures. Speaking to a Vilno correspondent, Merezhkovsky commented:The whole question of Russia's existence as such – and it's non-existent at the moment, as far as I am concerned, – depends on Europe's recognizing at last the true nature of Bolshevism. Europe has to open its eyes to the fact that Bolshevism uses the Socialist banner only as a camouflage; that what it does in effect is defile high Socialist ideals; that it is a global threat, not just local Russian disease. ...There is not a trace in Russia at the moment of either Socialism or even the roclaimed dictatorship of proletariat; the only dictatorship that's there is that of the two people:Lenin Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...andTrotsky Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ....

In

In Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

Merezhkovsky did practical work for some Russian immigrant organizations, Gippius edited the literary section in ''Svoboda'' newspaper. Both were regarding Poland as a "messianic", potentially unifying place and a crucial barrier in the face of the spreading Bolshevist plague. In the summer of 1920 Boris Savinkov arrived into the country to have talks with Józef Piłsudski

Józef Klemens Piłsudski (; 5 December 1867 – 12 May 1935) was a Polish statesman who served as the Chief of State (Poland), Chief of State (1918–1922) and first Marshal of Poland (from 1920). In the aftermath of World War I, he beca ...