The separation of church and state is a philosophical and

jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between

religious organizations

Religious activities generally need some infrastructure to be conducted. For this reason, there generally exist religion-supporting organizations, which are some form of organization that manages:

* the upkeep of places of worship, such as ...

and the

state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a

secular state (with or without legally explicit church-state separation) and to disestablishment, the changing of an existing, formal relationship between the church and the state. The concept originated among early

Baptists

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

in America. In 1644,

Roger Williams

Roger Williams (March 1683) was an English-born New England minister, theologian, author, and founder of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Providence Plantations, which became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Pl ...

, a Baptist minister and founder of the

state of Rhode Island and the

First Baptist Church in America, was the first public official to call for "a wall or hedge of separation" between "the wilderness of the world" and "the garden of the church." Although the concept is older, the exact phrase "separation of church and state" is derived from "wall of separation between Church & State," a term coined by

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

in his 1802 letter to members of the Danbury Baptist Association in the state of Connecticut. The concept was promoted by

Enlightenment philosophers such as

John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

.

In a society, the degree of political separation between the church and the civil state is determined by the legal structures and prevalent legal views that define the proper relationship between organized religion and the state. The

arm's length principle proposes a relationship wherein the two political entities interact as organizations each independent of the authority of the other. The strict application of the secular principle of ''

laïcité

(; 'secularism') is the constitutional principle of secularism in France. Article 1 of the French Constitution is commonly interpreted as the separation of civil society and religious society. It discourages religious involvement in governmen ...

'' is used in France. In contrast, societies such as Denmark and England maintain the constitutional recognition of an official

state church; similarly, other countries have a policy of

accommodationism

In law and philosophy, accommodationism is the cooperation between government and religious institutions. Underlying accommodationism is the idea that "government and religion are compatible and necessary to a well-ordered society." Accommodationis ...

, with religious symbols being present in the public square.

The philosophy of the separation of the church from the civil state parallels the philosophies of

secularism

Secularism is the principle of seeking to conduct human affairs based on naturalistic considerations, uninvolved with religion. It is most commonly thought of as the separation of religion from civil affairs and the state and may be broadened ...

,

disestablishmentarianism,

religious liberty, and

religious pluralism. By way of these philosophies, the European states assumed some of the social roles of the church in form of the

welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the State (polity), state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal oppor ...

, a social shift that produced a culturally secular population and

public sphere

The public sphere () is an area in social relation, social life where individuals can come together to freely discuss and identify societal problems, and through that discussion, Social influence, influence political action. A "Public" is "of or c ...

. In practice, church–state separation varies from total separation, mandated by the country's political

constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

, as in

India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

and

Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

, to a state religion, as in

the Maldives.

History of the concept and term

The precise origin of the term itself dates to Jefferson and his correspondence with religious denominations, however, the entanglement of religion with government and the state dates back to antiquity when state and religion were often closely associated with one another.

Antiquity and late antiquity

The entanglement of religion with the state has a long history dating back at least to the prosecution and conviction to death of Socrates for impiety in ancient Athens.

An important contributor to the discussion concerning the proper relationship between Church and state was

St. Augustine, who in ''

The City of God'', Book XIX, Chapter 17, examined the ideal relationship between the "earthly city" and the "city of God". In this work, Augustine posited that major points of overlap were to be found between the "earthly city" and the "city of God", especially as people need to live together and get along on earth. Thus, Augustine held, opposite to the separation of church and state, that it was the work of the "temporal city" to make it possible for a "heavenly city" to be established on earth.

Medieval Europe

For centuries, monarchs ruled by the idea of

divine right. Sometimes this began to be used by a monarch to support the notion that the king ruled both his own kingdom and Church within its boundaries, a theory known as

caesaropapism. On the other side was the Catholic doctrine that the

Pope

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

, as the Vicar of Christ on earth, should have the ultimate authority over the Church, and indirectly over the state, with the forged

Donation of Constantine used to justify and assert the

political authority of the papacy.

[Vauchez, Andre (2001). ''Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages''. Routledge. p. 445. .] This divine authority was explicitly contested by Kings, in the like of the, 1164,

Constitutions of Clarendon, which asserted the supremacy of Royal courts over Clerical, and with Clergy subject to prosecution, as any other subject of the English Crown; or the 1215

Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter"), sometimes spelled Magna Charta, is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Cardin ...

that asserted the supremacy of Parliament and juries over the English Crown; both were condemned by the Vatican. Moreover, throughout the Middle Ages, the

Pope

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

claimed the right to depose the Catholic kings of Western Europe and tried to exercise it, sometimes successfully, e.g. 1066,

Harold Godwinson, sometimes not, e.g., in 1305 with

Robert the Bruce

Robert I (11 July 1274 – 7 June 1329), popularly known as Robert the Bruce (), was King of Scots from 1306 until his death in 1329. Robert led Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland during the First War of Scottish Independence against Kingdom of Eng ...

of Scotland, and later

Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

and

Henry III of

Navarre. The

Waldensians

The Waldensians, also known as Waldenses (), Vallenses, Valdesi, or Vaudois, are adherents of a church tradition that began as an ascetic movement within Western Christianity before the Reformation. Originally known as the Poor of Lyon in the l ...

were a medieval

proto-Protestant group that urged separation of the Church from state.

In the West the issue of the separation of church and state during the medieval period centered on monarchs who

ruled in the secular sphere but encroached on the Church's rule of the spiritual sphere. This unresolved contradiction in ultimate control of the Church led to power struggles and crises of leadership, notably in the

Investiture Controversy, which was resolved in the

Concordat of Worms in 1122. By this concordat, the Emperor renounced the right to invest ecclesiastics with ring and crosier, the symbols of their spiritual power, and guaranteed election by the canons of cathedral or abbey and free consecration.

Reformation

At the beginning of the Protestant

Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

,

Martin Luther

Martin Luther ( ; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, Theology, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and former Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Reformation, Pr ...

articulated a

doctrine of the two kingdoms. According to

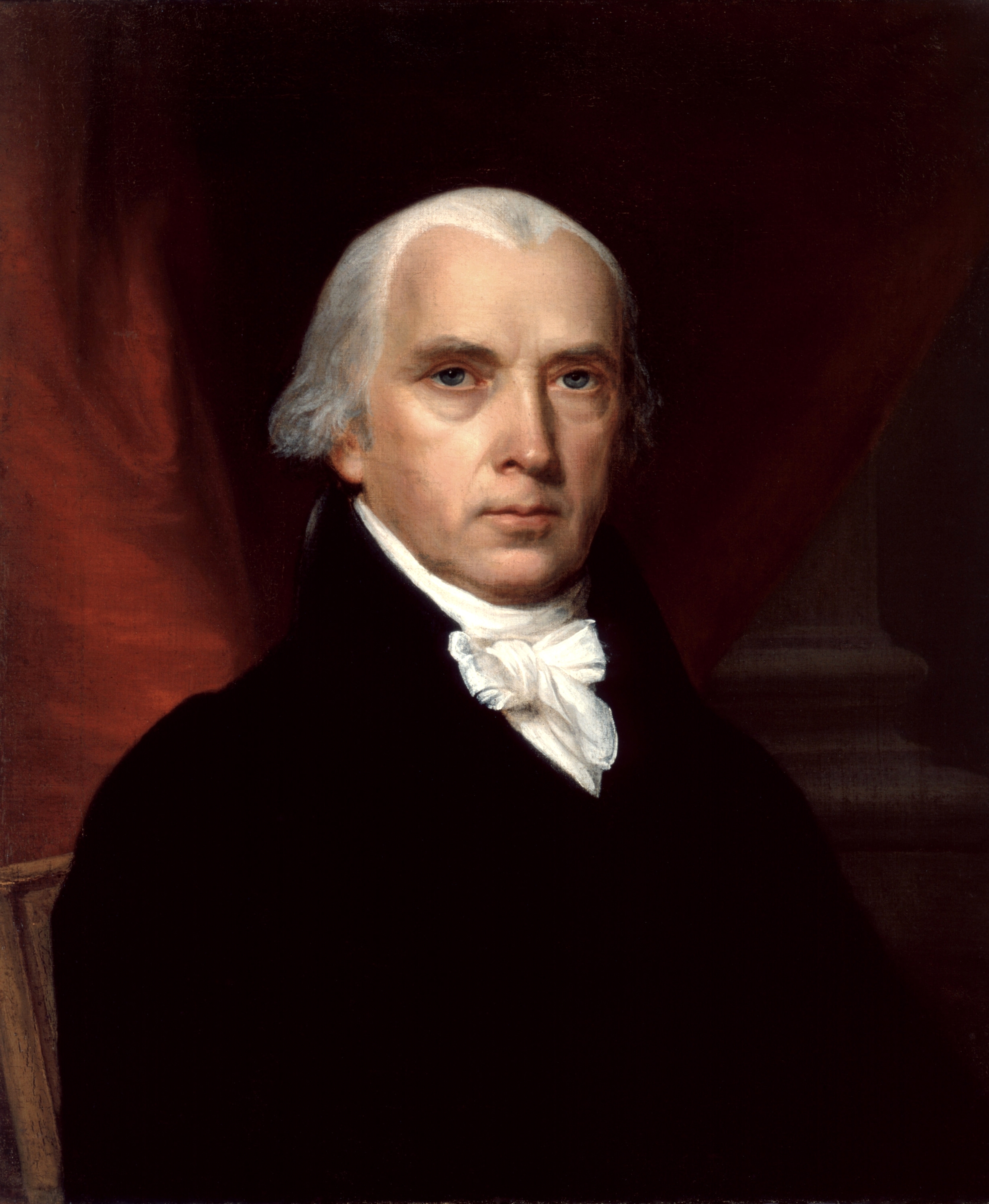

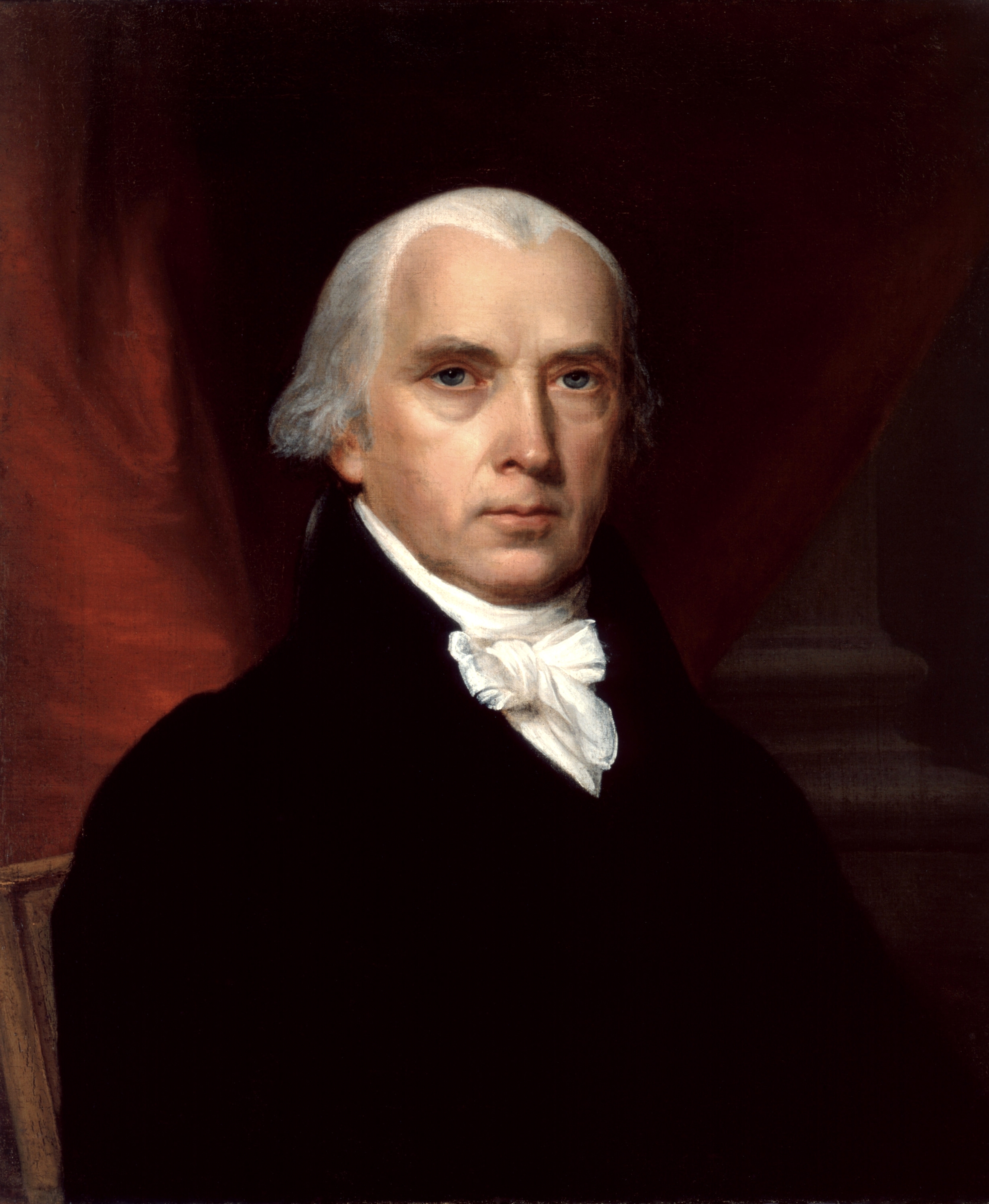

James Madison

James Madison (June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed as the ...

, perhaps one of the most important American proponents of the separation of church and state, Luther's doctrine of the two kingdoms marked the beginning of the modern conception of separation of church and state.

Those of the

Radical Reformation (the

Anabaptist

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek language, Greek : 're-' and 'baptism'; , earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. ...

s) took Luther's ideas in new directions, most notably in the writings of

Michael Sattler (1490–1527), who agreed with Luther that there were two kingdoms, but differed in arguing that these two kingdoms should be separate, and hence baptized believers should not vote, serve in public office or participate in any other way with the "kingdom of the world". While there was a diversity of views in the early days of the Radical Reformation, in time Sattler's perspective became the normative position for most Anabaptists in the coming centuries. Anabaptists came to teach that religion should never be compelled by state power, approaching the issue of church-state relations primarily from the position of protecting the church from the state.

In 1534,

Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

, angered by the

Pope Clement VII

Pope Clement VII (; ; born Giulio di Giuliano de' Medici; 26 May 1478 – 25 September 1534) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 November 1523 to his death on 25 September 1534. Deemed "the most unfortunate o ...

's refusal to annul his marriage to

Catherine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon (also spelt as Katherine,

historical Spanish: , now: ; 16 December 1485 – 7 January 1536) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England as the Wives of Henry VIII, first wife of King Henry VIII from their marr ...

, decided to break with the Church and set himself as ruler of the

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

, unifying the feudal Clerical and Crown hierarchies under a single monarchy. With periodic intermission, under Mary, Oliver Cromwell, and James II, the monarchs of Great Britain have retained ecclesiastical authority in the Church of England, since 1534, having the current title, ''

Supreme Governor of the Church of England''. The 1654 settlement, under

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

's

Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth of England was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when Kingdom of England, England and Wales, later along with Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland and Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, were governed as a republi ...

, temporarily replaced Bishops and Clerical courts, with a

Commission of Triers, and juries of Ejectors, to appoint and punish clergy in the English Commonwealth, later extended to cover Scotland.

Penal Laws requiring ministers, and public officials to swear oaths and follow the Established faith, were disenfranchised, fined, imprisoned, or executed, for not conforming.

One of the results of the persecution in England was that some people fled Great Britain to be able to worship as they wished. After the American Colonies

revolted against

George III of the United Kingdom

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Great Britain and Ireland into the United Kingdom of Great ...

, the

Establishment Clause

In United States law, the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, together with that Amendment's Free Exercise Clause, form the constitutional right of freedom of religion. The ''Establishment Clause'' an ...

regarding the concept of the separation of church and state was developed but was never part of the original US Constitution.

John Locke and the Enlightenment

The concept of separating church and state is often credited to the writings of English philosopher

John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

(1632–1704).

[Feldman, Noah (2005). ''Divided by God''. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, pg. 29 ("It took ]John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

to translate the demand for liberty of conscience into a systematic argument for distinguishing the realm of government from the realm of religion.") Roger Williams

Roger Williams (March 1683) was an English-born New England minister, theologian, author, and founder of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Providence Plantations, which became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Pl ...

was first in his 1636 writing of "Soul Liberty" where he coined the term "liberty of conscience". Locke would expand on this. According to his principle of the

social contract

In moral and political philosophy, the social contract is an idea, theory, or model that usually, although not always, concerns the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual. Conceptualized in the Age of Enlightenment, it ...

, Locke argued that the government lacked authority in the realm of individual conscience, as this was something rational people could not cede to the government for it or others to control. For Locke, this created a natural right in the liberty of conscience, which he argued must therefore remain protected from any government authority. These views on religious tolerance and the importance of individual conscience, along with his social contract, became particularly influential in the American colonies and the drafting of the

United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, on March 4, 1789. Originally includi ...

.

In his ''

A Letter Concerning Toleration'', in which Locke also defended religious toleration among different Christian sects, Locke argued that ecclesiastical authority had to be distinct from the authority of the state, or "the magistrate". Locke reasoned that, because a church was a voluntary community of members, its authority could not extend to matters of state. He writes:

At the same period of the 17th century,

Pierre Bayle and some

fideists were forerunners of the separation of Church and State, maintaining that faith was independent of reason.

During the 18th century, the ideas of Locke and Bayle, in particular the separation of Church and State, became more common, promoted by the philosophers of the

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

.

Montesquieu already wrote in 1721 about religious tolerance and a degree of separation between religion and government.

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

defended some level of separation but ultimately subordinated the Church to the needs of the State while

Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a prominent figure during th ...

, for instance, was a partisan of a strict separation of Church and State, saying "''the distance between the throne and the altar can never be too great''".

Jefferson and the Bill of Rights

In English, the exact term is an offshoot of the phrase, "wall of separation between church and state", as written in

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

's letter to the

Danbury Baptist Association in 1802. In that letter, referencing the

First Amendment to the United States Constitution

The First Amendment (Amendment I) to the United States Constitution prevents Federal government of the United States, Congress from making laws respecting an Establishment Clause, establishment of religion; prohibiting the Free Exercise Cla ...

, Jefferson writes:

Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between Man & his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship, that the legitimate powers of government reach actions only, & not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should 'make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,' thus building a wall of separation between Church and State.

Jefferson was describing to the Baptists that the

United States Bill of Rights

The United States Bill of Rights comprises the first ten list of amendments to the United States Constitution, amendments to the United States Constitution. It was proposed following the often bitter 1787–88 debate over the Timeline of dr ...

prevents the establishment of a national church, and in so doing they did not have to fear government interference in their right to expressions of religious conscience. The Bill of Rights, adopted in 1791 as ten amendments to the

Constitution of the United States

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, on March 4, 1789. Originally includi ...

, was one of the earliest political expressions against the political establishment of religion. Others were the

Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, also authored by Jefferson and adopted by Virginia in 1786; and the French

Declaration of the Rights of the Man and of the Citizen of 1789.

The metaphor "a wall of separation between Church and State" used by Jefferson in the above quoted letter became a part of the First Amendment jurisprudence of the U.S. Supreme Court. It was first used by Chief Justice Morrison Waite in ''

Reynolds v. United States'' (1878). American historian

George Bancroft was consulted by Waite in the ''Reynolds'' case regarding the views on establishment by the framers of the U.S. constitution. Bancroft advised Waite to consult Jefferson. Waite then discovered the above quoted letter in a library after skimming through the index to Jefferson's collected works according to historian Don Drakeman.

In various countries

Countries have varying degrees of separation between government and religious institutions. Since the 1780s a number of countries have set up explicit barriers between church and state. The degree of actual separation between government and religion or religious institutions varies widely. In some countries the two institutions remain heavily interconnected. There are new conflicts in the post-Communist world.

The many variations on separation can be seen in some countries with high degrees of religious freedom and tolerance combined with strongly secular political cultures which have still maintained state churches or financial ties with certain religious organizations into the 21st century. In England, there is a constitutionally established

state religion but

other faiths are tolerated. The

British monarch is the

supreme governor of the Church of England, and 26 bishops (

Lords Spiritual

The Lords Spiritual are the bishops of the Church of England who sit in the House of Lords of the United Kingdom. Up to 26 of the 42 diocesan bishops and archbishops of the Church of England serve as Lords Spiritual (not including retired bish ...

) sit in the upper house of government, the

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

.

In other kingdoms the

head of government

In the Executive (government), executive branch, the head of government is the highest or the second-highest official of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presid ...

or

head of state

A head of state is the public persona of a sovereign state.#Foakes, Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representative of its international persona." The name given to the office of head of sta ...

or other high-ranking official figures may be legally required to be a member of a given faith. Powers to appoint high-ranking members of the state churches are also often still vested in the worldly governments. These powers may be slightly anachronistic or superficial, however, and disguise the true level of religious freedom the nation possesses. In the case of Andorra there are two heads of state, neither of them native Andorrans. One is the Roman Catholic Bishop of Seu de Urgell, a town located in northern Spain. He has the title of Episcopalian Coprince (the other Coprince being the French Head of State). Coprinces enjoy political power in terms of law ratification and constitutional court designation, among others.

Australia

The

Constitution of Australia

The Constitution of Australia (also known as the Commonwealth Constitution) is the fundamental law that governs the political structure of Australia. It is a written constitution, which establishes the country as a Federation of Australia, ...

prevents the Commonwealth from establishing any religion or requiring a religious test for any office:

The language is derived from the United States' constitution, but has been altered. Following the usual practice of the

High Court, it has been interpreted far more narrowly than the equivalent US sections and no law has ever been struck down for contravening the section. Today, the Commonwealth Government provides broad-based funding to religious schools. The Commonwealth used to fund religious chaplains, but the High Court in ''

Williams v Commonwealth'' found the funding agreement invalid under Section 61. However, the High Court found that Section 116 had no relevance, as the chaplains themselves did not hold office under the Commonwealth. All Australian parliaments are opened with a Christian prayer, and the preamble to the Australian Constitution refers to "humbly relying on the blessing of Almighty God".

Although the Australian monarch is

Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms.

Charles was born at Buckingham Palace during the reign of his maternal grandfather, King George VI, and ...

, also British monarch and Supreme Governor of the

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

, his Australian title is unrelated to his religious office and he has no special role in the

Anglican Church of Australia

The Anglican Church of Australia, originally known as the Church of England in Australia and Tasmania, is a Christian church in Australia and an autonomous church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. In 2016, responding to a peer-reviewed study ...

, despite being "by the Grace of God King of Australia". The prohibition against religious tests has allowed former Anglican Archbishop of Brisbane

Peter Hollingworth to be appointed

Governor-General of Australia, the highest domestic constitutional officer; however, this was criticised.

[Hogan, M. (2001, May 16)]

Separation of church and state?

''Australian Review of Public Affairs''. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

Despite inclusion in the "States" chapter, Section 116 does not apply to states because of changes during drafting, and they are free to establish their own religions. Although no state has ever introduced a state church (

New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

restricted religious groups during the early colonial period), the legal body corresponding to many religious organisations is established by state legislation. There have been two referendums to extend Section 116 to states, but both failed. In each case the changes were grouped with other changes and voters did not have the opportunity to expressly accept only one change. Most states permit broad exemptions to religious groups from anti-discrimination legislation; for example, the New South Wales act allowing same-sex couples to adopt children permits religious adoption agencies to refuse them.

The current situation, described as a "principle of state neutrality" rather than "separation of church and state",

has been criticised by both secularists and religious groups. On the one hand, secularists have argued that government neutrality to religions leads to a "flawed democrac

or even a "pluralistic theocracy" as the government cannot be neutral towards the religion of people who do not have one. On the other hand, religious groups and others have been concerned that state governments are restricting them from exercising their religion by

preventing them from criticising other groups and forcing them to do unconscionable acts.

Azerbaijan

Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

is the dominant religion in Azerbaijan, with 96% of Azerbaijanis being

Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

, Shia being in the majority. However, Azerbaijan is officially a secular state. According to the Constitution of Azerbaijan, the state and mosque are separate. Article 7 of the Constitution defines the Azerbaijani state as a democratic, legal, secular, unitary republic. Therefore, the Constitution provides freedom of religions and beliefs.

The Azerbaijani State Committee for Work with Religious Organizations controls the relations between the state and religions.

Ethnic minorities such as

Russians

Russians ( ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Eastern Europe. Their mother tongue is Russian language, Russian, the most spoken Slavic languages, Slavic language. The majority of Russians adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church ...

,

Georgians

Georgians, or Kartvelians (; ka, ქართველები, tr, ), are a nation and Peoples of the Caucasus, Caucasian ethnic group native to present-day Georgia (country), Georgia and surrounding areas historically associated with the Ge ...

,

Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

,

Lezgis,

Avars,

Udis and

Kurds

Kurds (), or the Kurdish people, are an Iranian peoples, Iranic ethnic group from West Asia. They are indigenous to Kurdistan, which is a geographic region spanning southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, and northeastern Syri ...

with different religious beliefs to Islam all live in

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan, officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, is a Boundaries between the continents, transcontinental and landlocked country at the boundary of West Asia and Eastern Europe. It is a part of the South Caucasus region and is bounded by ...

. Several religions are practiced in Azerbaijan. There are many Orthodox and Catholic churches in different regions of Azerbaijan. At the same time, the Azerbaijani government has been frequently accused of desecrating Armenian Christian heritage and appropriating Armenian churches on its territory.

Brazil

Brazil was a

colony

A colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule, which rules the territory and its indigenous peoples separated from the foreign rulers, the colonizer, and their ''metropole'' (or "mother country"). This separated rule was often orga ...

of the

Portuguese Empire

The Portuguese Empire was a colonial empire that existed between 1415 and 1999. In conjunction with the Spanish Empire, it ushered in the European Age of Discovery. It achieved a global scale, controlling vast portions of the Americas, Africa ...

from 1500 until the nation's

independence

Independence is a condition of a nation, country, or state, in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the status of ...

from Portugal, in 1822, during which time

Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

was the official state religion. With the rise of the

Empire of Brazil

The Empire of Brazil was a 19th-century state that broadly comprised the territories which form modern Brazil and Uruguay until the latter achieved independence in 1828. The empire's government was a Representative democracy, representative Par ...

, although Catholicism retained its status as the official creed, subsidized by the state, other religions were allowed to flourish, as the

1824 Constitution secured

religious freedom

Freedom of religion or religious liberty, also known as freedom of religion or belief (FoRB), is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice ...

. The fall of the Empire, in 1889, gave way to a Republican regime, and a Constitution was enacted in 1891, which severed the ties between church and state; Republican ideologues such as

Benjamin Constant and

Ruy Barbosa were influenced by

laïcité

(; 'secularism') is the constitutional principle of secularism in France. Article 1 of the French Constitution is commonly interpreted as the separation of civil society and religious society. It discourages religious involvement in governmen ...

in France and the United States. The 1891 Constitutional separation of Church and State has been maintained ever since. The current

Constitution of Brazil, in force since 1988, ensures the right to religious freedom, bans the establishment of state churches and any relationship of "dependence or alliance" of officials with religious leaders, except for "collaboration in the public interest, defined by law".

In 2007,

Brasil para Todos was formed with the aim of removing religious symbols from government buildings with separation of church and state in mind.

Canada

Quebec

China

China, during the era of the

Han dynasty

The Han dynasty was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC9 AD, 25–220 AD) established by Liu Bang and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–206 BC ...

, had established

Confucianism

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China, and is variously described as a tradition, philosophy, Religious Confucianism, religion, theory of government, or way of li ...

as the official state ideology over that of

Legalism of the preceding

Qin dynasty

The Qin dynasty ( ) was the first Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China. It is named for its progenitor state of Qin, a fief of the confederal Zhou dynasty (256 BC). Beginning in 230 BC, the Qin under King Ying Zheng enga ...

over two millennium ago. In post-1949 modern-day China, owing to such historic experiences as the

Taiping Rebellion, the

Chinese Communist Party

The Communist Party of China (CPC), also translated into English as Chinese Communist Party (CCP), is the founding and One-party state, sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Founded in 1921, the CCP emerged victorious in the ...

had no diplomatic relations with the

Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Geography

* Vatican City, an independent city-state surrounded by Rome, Italy

* Vatican Hill, in Rome, namesake of Vatican City

* Ager Vaticanus, an alluvial plain in Rome

* Vatican, an unincorporated community in the ...

for over half a century, and maintained separation of the

temples (be it a

daoguan

A Daoist temple (), also called a () or (), is a place where the Dao is observed and cultivated. It is a place of worship in Taoism. Taoism is a religion that originated in China, with the belief in immortality, which urges people to become im ...

, a

Buddhist temple

A Buddhist temple or Buddhist monastery is the place of worship for Buddhism, Buddhists, the followers of Buddhism. They include the structures called vihara, chaitya, stupa, wat, khurul and pagoda in different regions and languages. Temples in B ...

, a

church or a

mosque

A mosque ( ), also called a masjid ( ), is a place of worship for Muslims. The term usually refers to a covered building, but can be any place where Salah, Islamic prayers are performed; such as an outdoor courtyard.

Originally, mosques were si ...

) from state affairs, and although the Chinese government's methods are disputed by the Vatican,

Pope Benedict XVI

Pope BenedictXVI (born Joseph Alois Ratzinger; 16 April 1927 – 31 December 2022) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 19 April 2005 until his resignation on 28 February 2013. Benedict's election as p ...

had accepted the ordination of a bishop who was pre-selected by the government for the

Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association in 2007. However, a new ordination of a Catholic bishop in November 2010, according to

BBC News

BBC News is an operational business division of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) responsible for the gathering and broadcasting of news and current affairs in the UK and around the world. The department is the world's largest broad ...

, has threatened to "damage ties" between China and the Vatican.

The

Constitution of the People's Republic of China

The Constitution of the People's Republic of China is the supreme law of the People's Republic of China (PRC). In September 1949, the first plenary session of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference adopted the Common Progr ...

guarantees, in its article 36, that:

Hong Kong

Macau

Croatia

Freedom of religion

Freedom of religion or religious liberty, also known as freedom of religion or belief (FoRB), is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice ...

in

Croatia

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herze ...

is a right defined by the

Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

, which also defines all religious communities as equal in front of the law and separated from the state. Principle of separation of church and state is enshrined in Article 41 which states:

All religious communities shall be equal before the law and clearly separated from the state. Religious communities shall be free, in compliance with law, to publicly conduct religious services, open schools, academies or other institutions, and welfare and charitable organizations and to manage them, and they shall enjoy the protection and assistance of the state in their activities.

Public schools allow religious teaching () in cooperation with religious communities having agreements with the state, but attendance is not mandated. Religion classes are organized widely in public elementary and secondary schools.

The public holidays also include religious festivals of:

Epiphany,

Easter Monday,

Corpus Christi Day,

Assumption Day,

All Saints' Day

All Saints' Day, also known as All Hallows' Day, the Feast of All Saints, the Feast of All Hallows, the Solemnity of All Saints, and Hallowmas, is a Christian solemnity celebrated in honour of all the saints of the Church, whether they are know ...

,

Christmas

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating Nativity of Jesus, the birth of Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a Religion, religious and Culture, cultural celebration among billions of people Observance of Christmas by coun ...

, and

Boxing Day

Boxing Day, also called as Offering Day is a holiday celebrated after Christmas Day, occurring on the second day of Christmastide (26 December). Boxing Day was once a day to donate gifts to those in need, but it has evolved to become a part ...

. The primary holidays are based on the Catholic liturgical year, but other believers are allowed to celebrate other major religious holidays as well.

The

Roman Catholic Church in Croatia receives state financial support and other benefits established in

concordat

A concordat () is a convention between the Holy See and a sovereign state that defines the relationship between the Catholic Church and the state in matters that concern both,René Metz, ''What is Canon Law?'' (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1960 [1 ...

s between the Government and the Vatican. In an effort to further define their rights and privileges within a legal framework, the government has additional agreements with other 14 religious communities: Serbian Orthodox Church (SPC), Islamic Community of Croatia, Evangelicalism, Evangelical Church, Reformed Christian Church in Croatia, Protestant Reformed Christian Church in Croatia, Pentecostal Church,

Union of Pentecostal Churches of Christ,

Christian Adventist Church,

Union of Baptist Churches,

Church of God,

Church of Christ,

Reformed Movement of Seventh-day Adventists,

Bulgarian Orthodox Church,

Macedonian Orthodox Church and Croatian

Old Catholic Church.

Finland

The

Constitution of Finland declares that the organization and administration of the

Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland is regulated in the Church Act, and the organization and administration of the

Finnish Orthodox Church in the Orthodox Church Act. The Lutheran Church and the Orthodox Church thus have a special status in Finnish legislation compared to other religious bodies, and are variously referred to as either "national churches" or "state churches", although officially they do not hold such positions. The Lutheran Church does not consider itself a state church, and prefers to use the term "national church".

The Finnish Freethinkers Association has criticized the official endorsement of the two churches by the Finnish state, and has campaigned for the separation of church and state.

France

The French version of separation of church and state, called ''

laïcité

(; 'secularism') is the constitutional principle of secularism in France. Article 1 of the French Constitution is commonly interpreted as the separation of civil society and religious society. It discourages religious involvement in governmen ...

'', is a product of French history and philosophy. It was formalized in a

1905 law providing for the separation of church and state, that is, the separation of religion from political power.

This model of a secularist state protects the religious institutions from state interference, but with public religious expression to some extent frowned upon. This aims to protect the public power from the influences of religious institutions, especially in public office. Religious views which contain no idea of public responsibility, or which consider religious opinion irrelevant to politics, are not impinged upon by this type of secularization of public discourse.

Former President

Nicolas Sarkozy criticised "negative " and talked about a "positive " that recognizes the contribution of faith to French culture, history and society, allows for faith in the public discourse and for government subsidies for faith-based groups.

[Beita, Peter B]

French President's religious mixing riles critics

Christianity Today, January 23, 2008 He visited the

Pope

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

in December 2007 and publicly emphasized France's

Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

roots, while highlighting the importance of

freedom of thought, advocating that

faith

Faith is confidence or trust in a person, thing, or concept. In the context of religion, faith is " belief in God or in the doctrines or teachings of religion".

According to the Merriam-Webster's Dictionary, faith has multiple definitions, inc ...

should come back into the

public sphere

The public sphere () is an area in social relation, social life where individuals can come together to freely discuss and identify societal problems, and through that discussion, Social influence, influence political action. A "Public" is "of or c ...

.

François Hollande

François Gérard Georges Nicolas Hollande (; born 12 August 1954) is a French politician who served as President of France from 2012 to 2017. Before his presidency, he was First Secretary of the Socialist Party (France), First Secretary of th ...

took a very different position during the

2012 presidential election, promising to insert the concept of into the constitution. In fact, the French constitution only says that the French Republic is "" but no article in the 1905 law or in the constitution defines .

Nevertheless, there are certain entanglements in France which include:

* The most significant example consists in two areas,

Alsace

Alsace (, ; ) is a cultural region and a territorial collectivity in the Grand Est administrative region of northeastern France, on the west bank of the upper Rhine, next to Germany and Switzerland. In January 2021, it had a population of 1,9 ...

and

Moselle (see for further detail), where the 1802

Concordat

A concordat () is a convention between the Holy See and a sovereign state that defines the relationship between the Catholic Church and the state in matters that concern both,René Metz, ''What is Canon Law?'' (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1960 ...

between France and the Holy See still prevails because the area was part of Germany when the

1905 French law on the Separation of the Churches and the State was passed and the attempt of the laicist Cartel des gauches in 1924 failed due to public protests. Catholic priests as well as the clergy of three other religions (the Lutheran EPCAAL, the Calvinist EPRAL, and Jewish Consistory (Judaism), consistories) are paid by the state, and schools have religion courses. Moreover, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Metz, Catholic bishops of Metz and

Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Strasbourg, of Strasbourg are named (or rather, formally appointed) by the French Head of State on proposition of the Pope. In the same way, the presidents of the two official Protestant churches are appointed by the State, after proposition by their respective Churches. This makes the French President the only temporal power in the world to formally have retained the right to appoint Catholic bishops, all other Catholic bishops being appointed by the Pope.

* In French Guiana the Royal Regulation of 1828 makes the French state pay for the Roman Catholic clergy, but not for the clergy of other religions.

* In the French oversea departments and territories since the 1939 décret Mandel the French State supports the Churches.

* The French President is ''ex officio'' a

co-prince of Andorra, where Roman Catholicism has a status of state religion (the other co-prince being the

Roman Catholic Bishop of Seu de Urgell, Spain). Moreover, French heads of states are traditionally offered an honorary title of

Canon of the

Papal Archbasilica of St. John Lateran, Cathedral of Rome. Once this honour has been awarded to a newly elected president, France pays for a ''choir vicar'', a priest who occupies the seat in the canonical chapter of the Cathedral in lieu of the president (all French presidents have been male and at least formally Roman Catholic, but if one were not, this honour could most probably not be awarded to him or her). The French President also holds a seat in a few other canonical chapters in France.

* Another example of the complex ties between France and the Catholic Church consists in the : five churches in Rome (

Trinità dei Monti, St. Louis of the French, St. Ivo of the Bretons, St. Claude of the Free County of Burgundy, and St. Nicholas of the Lorrains) as well as a chapel in

Loreto belong to France, and are administered and paid for by a special foundation linked to the French embassy to the Holy See.

* In

Wallis and Futuna

Wallis and Futuna, officially the Territory of the Wallis and Futuna Islands (), is a French island territorial collectivity, collectivity in the Oceania, South Pacific, situated between Tuvalu to the northwest, Fiji to the southwest, Tonga t ...

, a French overseas territory, national education is conceded to the diocese, which gets paid for it by the State.

* A further entanglement consists in liturgical honours accorded to French consular officials under Capitations with the Ottoman Empire which persist for example in Lebanon and in ownership of the Catholic cathedral in Smyrna (Izmir) and the extraterritoriality of St. Anne's in Jerusalem and more generally the diplomatic status of the Holy Places.

Germany

The

German constitution guarantees

freedom of religion

Freedom of religion or religious liberty, also known as freedom of religion or belief (FoRB), is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice ...

,

[Section 4 of German Basic Law] but there is not a complete separation of church and state in Germany. Officially recognized religious bodies operate as (

corporations of public law, as opposed to private). For recognized religious communities, some taxes () are collected by the state; this is at the request of the religious community and a fee is charged for the service.

Religious instruction is an optional school subject in Germany.

The German State understands itself as neutral in matters of religious beliefs, so no teacher can be forced to teach religion. But on the other hand, all who do teach religious instruction need an official permission by their religious community. The treaties with the

Holy See

The Holy See (, ; ), also called the See of Rome, the Petrine See or the Apostolic See, is the central governing body of the Catholic Church and Vatican City. It encompasses the office of the pope as the Bishops in the Catholic Church, bishop ...

are referred to as

concordats whereas the treaties with Protestant Churches and umbrellas of Jewish congregations are called "state treaties". Both are the legal framework for cooperation between the religious bodies and the German State at the federal as well as at the state level.

Greece

In Greece, there is considerable controversy about the separation between the State and the Church, causing many debates in the public sphere regarding if there shall be a more radical change in the Article 3, which is maintaining the Greek Orthodox Church of Christ as the prevailing religion of the country. The actual debate concerning the separation of the Church from the State often becomes a tool for polarization in the political competition. More specifically, Article 3 of the Greek constitution argues the following:

# “The prevailing religion in Greece is that of the Greek Orthodox Church of Christ. The Orthodox Church of Greece, acknowledging our Lord Jesus Christ as its head, is inseparably united in doctrine with the Great Church of Christ in Constantinople and with every other Church of Christ of the same doctrine, observing unwaveringly, as they do the holy apostolic and synodal canons and sacred traditions. It is autocephalous and is administered by the Holy Synod of serving Bishops and the Permanent Holy Synod originating thereof and assembled as specified by the Statutory Charter of the Church in compliance with the provisions of the Patriarchal Tome of June 29, 1850 and the Synodal Act of September 4, 1928.

# The ecclesiastical regime existing in certain districts of the State shall not be deemed contrary to the provisions of the preceding paragraph.

# The text of the Holy Scripture shall be maintained unaltered. Official translation of the text into any other form of language, without prior sanction by the Autocephalous Church of Greece and the Great Church of Christ in Constantinople, is prohibited.”

Moreover, the controversial situation about the no separation between the State and the Church seems to affect the recognition of religious groups in the country as there seems to be no official mechanism for this process.

India

The

Constitution of India

The Constitution of India is the supreme law of India, legal document of India, and the longest written national constitution in the world. The document lays down the framework that demarcates fundamental political code, structure, procedures ...

uses the word "Secular" in a very unique way, differing from the western concept of "Separation of the Church and the State". The western concept provides for a "vertical" separation in terms of position of the state and the religion in a political setup, where both co-exist. On the other hand, the

Constitution of India

The Constitution of India is the supreme law of India, legal document of India, and the longest written national constitution in the world. The document lays down the framework that demarcates fundamental political code, structure, procedures ...

defines secularism looking at the social implication of the religious practice. The article 25 of the constitution guarantees freedom of conscience and free profession, practice and propagation of religion subject to public order, morality, health and Fundamental Rights. The same article empowers the state to regulate secular activities which may be associated with religious practice, thus allowing state interference in the religion.

Dr B. R. Ambedkar, highlighted the social implication of religion in India in the constituent assembly debates. While defending for the state interference in prohibiting religious instruction in schools, he argued, On the same lines of social implication of the religion the constitution enables the state to open the Hindu temples for all classes and sections of society.

In S. R. Bommai vs Union of India, 1994, the Supreme Court laid down the principle of "Positive Secularism" and a "horizontal" separation of secular - material world from a religious - spiritual world. Matters which are purely religious are left personal to the individual and the secular part is taken charge by the state on grounds of public interest, order and general welfare. Positive secularism, therefore, separates the religious faith personal to man and limited to material, temporal aspects of human life. Positive secularism believes in the basic values of freedom, equality and fellowship

Italy

In

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

the principle of separation of church and state is enshrined in Article 7 of the

Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

, which states: "The State and the Catholic Church are independent and sovereign, each within its own sphere. Their relations are regulated by the Lateran pacts. Amendments to such Pacts which are accepted by both parties shall not require the procedure of constitutional amendments."

Ireland

Japan

Shinto

, also called Shintoism, is a religion originating in Japan. Classified as an East Asian religions, East Asian religion by Religious studies, scholars of religion, it is often regarded by its practitioners as Japan's indigenous religion and as ...

became the

state religion in Japan with the

Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored Imperial House of Japan, imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Althoug ...

in 1868, and suppression of other religions ensued.

Under the

American military occupation (1945–52) "

State Shinto

was Empire of Japan, Imperial Japan's ideological use of the Japanese folk religion and traditions of Shinto. The state exercised control of shrine finances and training regimes for Kannushi, priests to strongly encourage Shinto practices that ...

" was considered to have been used as a propaganda tool to propel the Japanese people to war. The

Shinto Directive issued by the occupation government required that all state support for and involvement in any religious or Shinto institution or doctrine stop, including funding, coverage in textbooks, and official acts and ceremonies.

The new constitution adopted in 1947, Articles 20 and 89 of the

Japanese Constitution protect freedom of religion, and prevent the government from compelling religious observances or using public money to benefit religious institutions.

South Korea

Freedom of religion in South Korea is provided for in the

South Korean Constitution, which mandates the separation of religion and state, and prohibits discrimination on the basis of religious beliefs. Despite this, religious organizations play a major role and make strong influence in politics.

Mexico

The issue of the role of the

Catholic Church in Mexico

The Mexican Catholic Church, or Catholic Church in Mexico, is part of the worldwide Catholic Church, under the spiritual leadership of the Pope, his Roman Curia, Curia in Rome, and the national Mexican Episcopal Conference. According to the Mexi ...

has been highly divisive since the 1820s. Its large land holdings were especially a point of contention. Mexico was guided toward what was proclaimed a separation of church and state by

Benito Juárez who, in 1859, attempted to eliminate the role of the Roman Catholic Church in the nation by appropriating its land and prerogatives.

President

Benito Juárez confiscated church property, disbanded religious orders and he also ordered the separation of church and state

His

Juárez Law, formulated in 1855, restricting the legal rights of the church was later added to the

Constitution of Mexico in 1857.

In 1859 the ''

Ley Lerdo'' was issued – purportedly separating church and state, but actually involving state intervention in Church matters by abolishing monastic orders, and nationalizing church property.

In 1926, after several years of the

Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution () was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from 20 November 1910 to 1 December 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It saw the destruction of the Federal Army, its ...

and insecurity, President

Plutarco Elías Calles, leader of the ruling

National Revolutionary Party, enacted the

Calles Law, which eradicated all the personal property of the churches, closed churches that were not registered with the State, and prohibited clerics from holding a public office. The law was unpopular; and several protesters from rural areas, fought against federal troops in what became known as the

Cristero War. After the war's end in 1929, President

Emilio Portes Gil upheld a previous truce where the law would remain enacted, but not enforced, in exchange for the hostilities to end.

Norway

An act approved in 2016 created the

Church of Norway as an independent legal entity, effective from 1 January 2017. Before 2017 all clergy were civil servants (employees of the central government). On 21 May 2012, the

Norwegian Parliament passed a

constitutional amendment that granted the Church of Norway increased autonomy, and states that "the Church of Norway, an Evangelical-Lutheran church, remains Norway's people's church, and is supported by the State as such" ("people's church" or is also the name of the Danish state church,

Folkekirken), replacing the earlier expression which stated that "the Evangelical-Lutheran religion remains the public religion of the State." The final amendment passed by a vote of 162–3. The three dissenting votes were all from the

Centre Party.

The constitution also says that Norway's values are based on its Christian and humanist heritage, and according to the Constitution, the

King

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an Absolute monarchy, absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted Government, governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a Constitutional monarchy, ...

is required to be Lutheran. The government will still provide funding for the church as it does with other faith-based institutions, but the responsibility for appointing bishops and provosts will now rest with the church instead of the government. Prior to 1997, the appointments of parish priests and residing chaplains was also the responsibility of the government, but the church was granted the right to hire such clergy directly with the new Church Law of 1997. The Church of Norway is regulated by its own law () and all municipalities are required by law to support the activities of the Church of Norway and municipal authorities are represented in its local bodies.

Philippines

In Article II "Declaration of Principles and State Policies", Section 6, the

1987 Constitution of the Philippines declares, "The separation of Church and State shall be inviolable." This reasserts, with minor differences in wording and capitalization, a declaration made in Article XV, Section 15 of the 1973 Constitution.

Similarly, Article III, Section 5 declares, "No law shall be made respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof. The free exercise and enjoyment of religious profession and worship, without discrimination or preference, shall forever be allowed. No religious test shall be required for the exercise of civil or political rights."; echoing Article IV, Section 8 of the 1973 Constitution verbatim.

Romania

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

is a secular state and has no state religion. However, the role of religion in society is regulated by several articles of the Romanian Constitution.

Art 29. Freedom of Conscience. (1) Freedom of thought and opinion, as well as freedom of religion, cannot be limited in any way. No one shall be coerced to adopt an opinion or adhere to a religious faith against their will.

(5) Religious cults are autonomous in relation to the state, which provides support including the facilitation of religious assistance in the army, hospitals, penitentiaries, retirement homes and orphanages.

Art 32. Right to education (7) The state assures freedom of religious education, according to the requirements of each specific cult. In state schools, religious education is organized and guaranteed by law.

Saudi Arabia

The legal system of Saudi Arabia is based on

Sharia

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on Islamic holy books, scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran, Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' ...

,

Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

ic law derived from the

Quran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a Waḥy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

and the

Sunnah

is the body of traditions and practices of the Islamic prophet Muhammad that constitute a model for Muslims to follow. The sunnah is what all the Muslims of Muhammad's time supposedly saw, followed, and passed on to the next generations. Diff ...

(the traditions) of the

Islamic prophet Muhammad, and therefore no separation of mosque and state is present.

Singapore

Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

is home to people of many religions and does not have any state religion. The

government of Singapore

The government of Singapore is defined by the Constitution of Singapore, Constitution of the Republic of Singapore to consist of the President of Singapore, President and the Executive. Executive authority of Singapore is vested in the Presi ...

has attempted to avoid giving any specific religions priority over the rest.

In 1972 the Singapore government de-registered and banned the activities of Jehovah's Witnesses in Singapore. The Singaporean government claimed that this was justified because members of Jehovah's Witnesses refuse to perform military service (which is obligatory for all male citizens), salute the

flag

A flag is a piece of textile, fabric (most often rectangular) with distinctive colours and design. It is used as a symbol, a signalling device, or for decoration. The term ''flag'' is also used to refer to the graphic design employed, and fla ...

, or swear oaths of allegiance to the state.

Singapore has also banned all written materials published by the

International Bible Students Association and the

Watchtower Bible and Tract Society, both publishing arms of the Jehovah's Witnesses. A person who possesses a prohibited publication can be fined up to $2,000 Singapore dollars and jailed up to 12 months for a first conviction.

["2010 International Religious Freedom Report 2010: Singapore", U.S. State Department, November 17, 2010]

As Retrieved 2011-1-15

/ref>

Spain

In Spain, commentators have posited that the form of church-state separation enacted in France in 1905 and found in the Spanish Constitution of 1931 are of a "hostile" variety, noting that the hostility of the state toward the church was a cause of the breakdown of democracy and the onset of the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

.[Stepan, Alfred, ]

Arguing Comparative Politics

'', p. 221, Oxford University Press Following the end of the war, the Catholic Church regained an officially sanctioned, predominant position with General Franco. Religious freedom was guaranteed only in 1966, nine years before the end of the regime.

Since 1978, according to the Spanish Constitution (section 16.3) "No religion shall have a state character. The public authorities shall take into account the religious beliefs of Spanish society and shall consequently maintain appropriate cooperation relations with the Catholic Church and other confessions."

Sweden

The Church of Sweden

The Church of Sweden () is an Evangelical Lutheran national church in Sweden. A former state church, headquartered in Uppsala, with around 5.5 million members at year end 2023, it is the largest Christian denomination in Sweden, the largest List ...

was instigated by King Gustav I (1523–60) and within the half century following his death had become established as a Lutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

state church with significant power in Swedish society, itself under the control of the state apparatus. A degree of freedom of worship (for foreign residents only) was achieved under the rule of Gustav III (1771–92), but it was not until the passage of the Dissenter Acts of 1860 and 1874 that Swedish citizens were allowed to leave the state church – and then only provided that those wishing to do so first registered their adhesion to another, officially approved denomination. Following years of discussions that began in 1995, the Church of Sweden was finally separated from the state as from 1 January 2000. However, the separation was not fully completed. Although the status of state religion came to an end, the Church of Sweden nevertheless remains Sweden's national church, and as such is still regulated by the government through the law of the Church of Sweden. Therefore, it would be more appropriate to refer to a change of relation between state and church rather than a separation. Furthermore, the Swedish constitution still maintains that the Sovereign and the members of the royal family have to confess an evangelical Lutheran faith, which in practice means they need to be members of the Church of Sweden to remain in the line of succession. Thusly according to the ideas of cuius regio, eius religio one could argue that the symbolic connection between state and church still remains.

Switzerland

The articles 8 ("Equality before the law") and 15 ("Freedom of religion and conscience") of the Federal Constitution of the Swiss Confederation guarantees individual freedom of beliefs.[Federal Constitution of the Swiss Confederation]

, status as of 14 June 2015, Federal Chancellery of Switzerland

The Federal Chancellery of Switzerland is a department-level agency of the federal administration of Switzerland. It is the staff organisation of the federal government, the Federal Council (Switzerland), Federal Council. Since 2024, it has bee ...

(page visited on 17 December 2015). It notably states that "No person may be forced to join or belong to a religious community, to participate in a religious act or to follow religious teachings".[

Churches and state are separated at the federal level since 1848. However, the article 72 ("Church and state") of the ]constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

determine that "The regulation of the relationship between the church and the state is the responsibility of the cantons".[ Some ]cantons of Switzerland

The 26 cantons of Switzerland are the Federated state, member states of the Switzerland, Swiss Confederation. The nucleus of the Swiss Confederacy in the form of the first three confederate allies used to be referred to as the . Two important ...

recognise officially some churches (Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, Swiss Reformed Church, Old Catholic Church and Jewish congregations). Other cantons, such as Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

and Neuchâtel are '' laïques'' (that is to say, secular).

Taiwan

Turkey

Turkey, whose population is overwhelmingly Muslim, is also considered to have practiced the laïcité

(; 'secularism') is the constitutional principle of secularism in France. Article 1 of the French Constitution is commonly interpreted as the separation of civil society and religious society. It discourages religious involvement in governmen ...

school of secularism since 1928, which the founding father Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk ( 1881 – 10 November 1938) was a Turkish field marshal and revolutionary statesman who was the founding father of the Republic of Turkey, serving as its first President of Turkey, president from 1923 until Death an ...

's policies and theories became known as Kemalism.

Despite Turkey being an officially secular country, the Preamble of the Constitution states that "there shall be no interference whatsoever of the sacred religious feelings in State affairs and politics." In order to control the way religion is perceived by adherents, the State pays imam

Imam (; , '; : , ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Islam, Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a prayer leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Salah, Islamic prayers, serve as community leaders, ...

s' wages (only for Sunni Muslims) and provides religious education (of the Sunni Muslim variety) in public schools. The State has a Directorate of Religious Affairs, directly under the President bureaucratically, responsible for organizing the Sunni

Sunni Islam is the largest branch of Islam and the largest religious denomination in the world. It holds that Muhammad did not appoint any successor and that his closest companion Abu Bakr () rightfully succeeded him as the caliph of the Mu ...

Muslim religion – including what will and will not be mentioned in sermons given at mosque

A mosque ( ), also called a masjid ( ), is a place of worship for Muslims. The term usually refers to a covered building, but can be any place where Salah, Islamic prayers are performed; such as an outdoor courtyard.

Originally, mosques were si ...

s, especially on Fridays. Such an interpretation of secularism, where religion is under strict control of the State is very different from that of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution

The First Amendment (Amendment I) to the United States Constitution prevents Federal government of the United States, Congress from making laws respecting an Establishment Clause, establishment of religion; prohibiting the Free Exercise Cla ...