Dinitrogenase on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Nitrogenases are

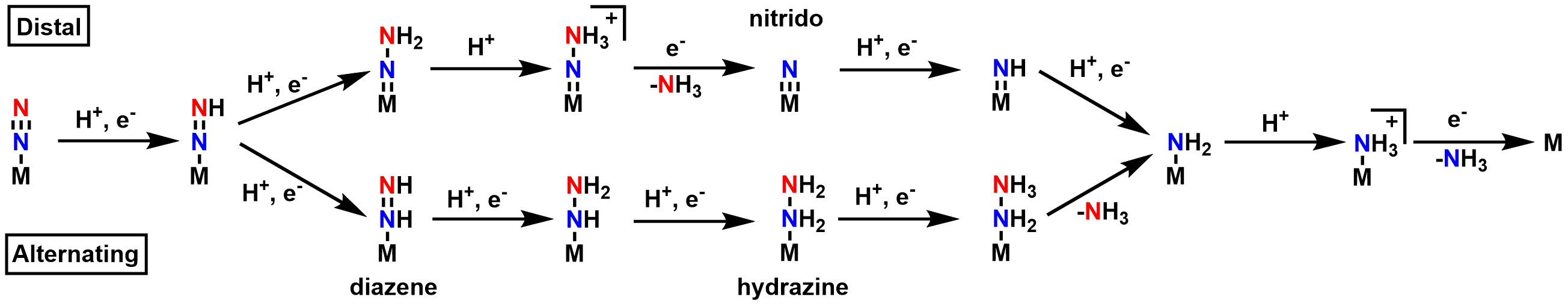

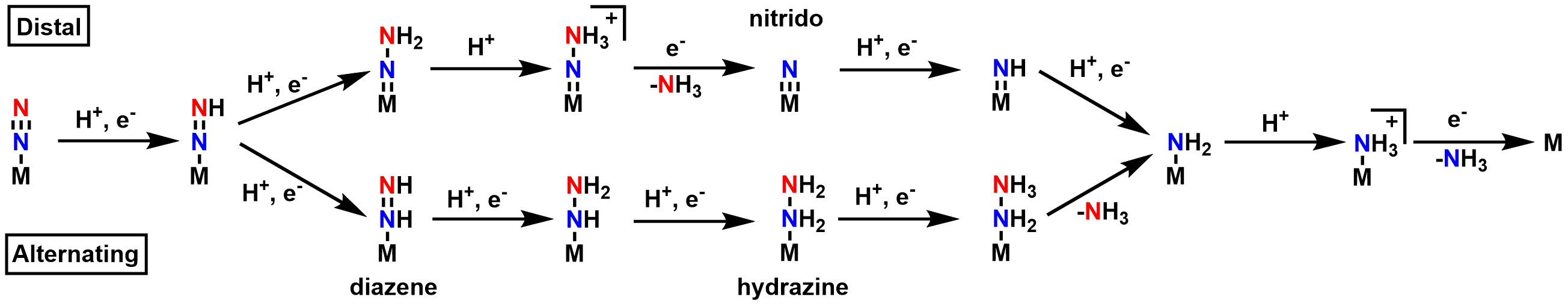

While the mechanism for nitrogen fixation prior to the Janus E4 complex is generally agreed upon, there are currently two hypotheses for the exact pathway in the second half of the mechanism: the "distal" and the "alternating" pathway. In the distal pathway, the terminal nitrogen is hydrogenated first, releases ammonia, then the nitrogen directly bound to the metal is hydrogenated. In the alternating pathway, one hydrogen is added to the terminal nitrogen, then one hydrogen is added to the nitrogen directly bound to the metal. This alternating pattern continues until ammonia is released. Because each pathway favors a unique set of intermediates, attempts to determine which path is correct have generally focused on the isolation of said intermediates, such as the nitrido in the distal pathway, and the diazene and

While the mechanism for nitrogen fixation prior to the Janus E4 complex is generally agreed upon, there are currently two hypotheses for the exact pathway in the second half of the mechanism: the "distal" and the "alternating" pathway. In the distal pathway, the terminal nitrogen is hydrogenated first, releases ammonia, then the nitrogen directly bound to the metal is hydrogenated. In the alternating pathway, one hydrogen is added to the terminal nitrogen, then one hydrogen is added to the nitrogen directly bound to the metal. This alternating pattern continues until ammonia is released. Because each pathway favors a unique set of intermediates, attempts to determine which path is correct have generally focused on the isolation of said intermediates, such as the nitrido in the distal pathway, and the diazene and

Binding of MgATP is one of the central events to occur in the mechanism employed by nitrogenase.

Binding of MgATP is one of the central events to occur in the mechanism employed by nitrogenase.

enzymes

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as pro ...

() that are produced by certain bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

, such as cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

(blue-green bacteria) and rhizobacteria. These enzymes are responsible for the reduction of nitrogen

Nitrogen is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a Nonmetal (chemistry), nonmetal and the lightest member of pnictogen, group 15 of the periodic table, often called the Pnictogen, pnictogens. ...

(N2) to ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic chemical compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the chemical formula, formula . A Binary compounds of hydrogen, stable binary hydride and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinctive pu ...

(NH3). Nitrogenases are the only family of enzymes known to catalyze this reaction, which is a step in the process of nitrogen fixation

Nitrogen fixation is a chemical process by which molecular dinitrogen () is converted into ammonia (). It occurs both biologically and abiological nitrogen fixation, abiologically in chemical industry, chemical industries. Biological nitrogen ...

. Nitrogen fixation is required for all forms of life, with nitrogen being essential for the biosynthesis

Biosynthesis, i.e., chemical synthesis occurring in biological contexts, is a term most often referring to multi-step, enzyme-Catalysis, catalyzed processes where chemical substances absorbed as nutrients (or previously converted through biosynthe ...

of molecules

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms that are held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions that satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry ...

(nucleotides

Nucleotides are Organic compound, organic molecules composed of a nitrogenous base, a pentose sugar and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both o ...

, amino acids

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the Proteinogenic amino acid, 22 α-amino acids incorporated into p ...

) that create plants, animals and other organisms. They are encoded by the Nif gene

The ''nif'' genes are genes encoding enzymes involved in the fixation of atmospheric nitrogen into a form of nitrogen available to living organisms. The primary enzyme encoded by the ''nif'' genes is the nitrogenase complex which is in charge of ...

s or homologs

Homologous chromosomes or homologs are a set of one maternal and one paternal chromosome that pair up with each other inside a cell during meiosis. Homologs have the same genes in the same loci, where they provide points along each chromosome th ...

. They are related to protochlorophyllide reductase.

Classification and structure

Although the equilibrium formation of ammonia from molecular hydrogen and nitrogen has an overall negativeenthalpy of reaction

The standard enthalpy of reaction (denoted \Delta H_^\ominus) for a chemical reaction is the difference between total product and total reactant molar enthalpies, calculated for substances in their standard states. The value can be approximately i ...

(), the activation energy

In the Arrhenius model of reaction rates, activation energy is the minimum amount of energy that must be available to reactants for a chemical reaction to occur. The activation energy (''E''a) of a reaction is measured in kilojoules per mole (k ...

is very high (). Nitrogenase acts as a catalyst

Catalysis () is the increase in rate of a chemical reaction due to an added substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed by the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recycles quick ...

, reducing this energy barrier such that the reaction can take place at ambient temperatures.

A usual assembly consists of two components:

# The homodimeric Fe-only protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

, the reductase

In biochemistry, an oxidoreductase is an enzyme that catalyzes the transfer of electrons from one molecule, the reductant, also called the electron donor, to another, the oxidant, also called the electron acceptor. This group of enzymes usually uti ...

which has a high reducing power and is responsible for a supply of electrons.

# The heterotetrameric MoFe protein, a nitrogenase which uses the electrons provided to reduce N2 to NH3. In some assemblies it is replaced by a homologous alternative.

Reductase

The Fe protein, the dinitrogenase reductase or NifH, is a dimer of identical subunits which contains one e4S4cluster and has a mass of approximately 60-64kDa. The function of the Fe protein is to transfer electrons from areducing agent

In chemistry, a reducing agent (also known as a reductant, reducer, or electron donor) is a chemical species that "donates" an electron to an (called the , , , or ).

Examples of substances that are common reducing agents include hydrogen, carbon ...

, such as ferredoxin

Ferredoxins (from Latin ''ferrum'': iron + redox, often abbreviated "fd") are iron–sulfur proteins that mediate electron transfer in a range of metabolic reactions. The term "ferredoxin" was coined by D.C. Wharton of the DuPont Co. and applied t ...

or flavodoxin to the nitrogenase protein. Ferredoxin or flavodoxin can be reduced by one of six mechanisms: 1. by a pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase, 2. by a bi-directional hydrogenase

A hydrogenase is an enzyme that Catalysis, catalyses the reversible Redox, oxidation of molecular hydrogen (H2), as shown below:

Hydrogen oxidation () is coupled to the reduction of electron acceptors such as oxygen, nitrate, Ferric, ferric i ...

, 3. in a photosynthetic reaction center, 4. by coupling electron flow to dissipation of the proton motive force

Chemiosmosis is the movement of ions across a semipermeable membrane bound structure, down their electrochemical gradient. An important example is the formation of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) by the movement of hydrogen ions (H+) across a membra ...

, 5. by electron bifurcation

In biochemistry, electron bifurcation (EB) refers to a system that enables an unfavorable ( endergonic) transformation by coupling to a favorable ( exergonic) transformation. Two electrons are involved: one flows to an acceptor with a "higher redu ...

, or 6. by a ferredoxin:NADPH oxidoreductase. The transfer of electrons requires an input of chemical energy which comes from the binding and hydrolysis of ATP. The hydrolysis of ATP also causes a conformational change within the nitrogenase complex, bringing the Fe protein and MoFe protein closer together for easier electron transfer.

Nitrogenase

The MoFe protein is a heterotetramer consisting of two α subunits and two β subunits, with a mass of approximately 240-250kDa. The MoFe protein also contains two iron–sulfur clusters, known as P-clusters, located at the interface between the α and β subunits and two FeMo cofactors, within the α subunits. The oxidation state of Mo in these nitrogenases was formerly thought Mo(V), but more recent evidence is for Mo(III). (Molybdenum in other enzymes is generally bound tomolybdopterin

Molybdopterins are a class of cofactors found in most molybdenum-containing and all tungsten-containing enzymes. Synonyms for molybdopterin are: MPT and pyranopterin-dithiolate. The nomenclature for this biomolecule can be confusing: Molybdopte ...

as fully oxidized Mo(VI)).

* The core (Fe8S7) of the P-cluster takes the form of two e4S3cubes linked by a central sulfur atom. Each P-cluster is linked to the MoFe protein by six cysteine residues.

* Each FeMo cofactor (Fe7MoS9C) consists of two non-identical clusters: e4S3and oFe3S3 which are linked by three sulfide ions. Each FeMo cofactor is covalently linked to the α subunit of the protein by one cysteine

Cysteine (; symbol Cys or C) is a semiessential proteinogenic amino acid with the chemical formula, formula . The thiol side chain in cysteine enables the formation of Disulfide, disulfide bonds, and often participates in enzymatic reactions as ...

residue and one histidine

Histidine (symbol His or H) is an essential amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an Amine, α-amino group (which is in the protonated –NH3+ form under Physiological condition, biological conditions), a carboxylic ...

residue.

Electrons from the Fe protein enter the MoFe protein at the P-clusters, which then transfer the electrons to the FeMo cofactors. Each FeMo cofactor then acts as a site for nitrogen fixation, with N2 binding in the central cavity of the cofactor.

Variations

The MoFe protein can be replaced by alternative nitrogenases in environments low in the Mo cofactor. Two types of such nitrogenases are known: the vanadium–iron (VFe; ''Vnf'') type and the iron–iron (FeFe; ''Anf'') type. Both form an assembly of two α subunits, two β subunits, and two δ (sometimes γ: VnfG/AnfG) subunits. The delta subunits are homologous to each other, and the alpha and beta subunits themselves are homologous to the ones found in MoFe nitrogenase. The gene clusters are also homologous, and these subunits are interchangeable to some degree. All nitrogenases use a similar Fe-S core cluster, and the variations come in the cofactor metal. The δ/γ subunit helps bind the cofactor in the FeFe nitrogenase. Based on the timing of its evolution, the subunit in VFe and FeFe nitrogenases is believed to have helped with the prototypical alternative nitrogenase adapt to new metals. Most, if not all, natural organisms carrying genes for an alternative nitrogenase also carry genes for the regular MoFe nitrogenase. The MoFe nitrogenase is the most efficient in that it wastes less ATP on reducing H+ into H2 than the alternative nitrogenases (see #General mechanism below). When Mo is present, the expression of the alternative nitrogenases is repressed, so that only the more efficient enzyme is used. The FeFe nitrogenase in ''Azotobacter vinelandii

''Azotobacter vinelandii'' is Gram-negative diazotroph that can fix nitrogen while grown aerobically. These bacteria are easily cultured and grown.

''A. vinelandii'' is a free-living N2 fixer known to produce many phytohormones and vitamins in ...

'' (a model organism for nitrogenase engineering) is organized in an ''anfHDGKOR'' operon. This operon still requires some of the Nif gene

The ''nif'' genes are genes encoding enzymes involved in the fixation of atmospheric nitrogen into a form of nitrogen available to living organisms. The primary enzyme encoded by the ''nif'' genes is the nitrogenase complex which is in charge of ...

s to function. A minimal 10-gene operon that incorporates these additional essential genes has been constructed in the lab.

Mechanism

General mechanism

Nitrogenase is an enzyme responsible for catalyzingnitrogen fixation

Nitrogen fixation is a chemical process by which molecular dinitrogen () is converted into ammonia (). It occurs both biologically and abiological nitrogen fixation, abiologically in chemical industry, chemical industries. Biological nitrogen ...

, which is the reduction of nitrogen (N2) to ammonia (NH3) and a process vital to sustaining life on Earth. There are three types of nitrogenase found in various nitrogen-fixing bacteria: molybdenum (Mo) nitrogenase, vanadium (V) nitrogenase, and iron-only (Fe) nitrogenase. Molybdenum nitrogenase, which can be found in diazotroph

Diazotrophs are organisms capable of nitrogen fixation, i.e. converting the relatively inert diatomic nitrogen (N2) in Earth's atmosphere into bioavailable compound forms such as ammonia. Diazotrophs are typically microorganisms such as bacteria ...

s such as legume

Legumes are plants in the pea family Fabaceae (or Leguminosae), or the fruit or seeds of such plants. When used as a dry grain for human consumption, the seeds are also called pulses. Legumes are grown agriculturally, primarily for human consum ...

-associated rhizobia

Rhizobia are diazotrophic bacteria that fix nitrogen after becoming established inside the root nodules of legumes (Fabaceae). To express genes for nitrogen fixation, rhizobia require a plant host; they cannot independently fix nitrogen. I ...

, is the nitrogenase that has been studied the most extensively and thus is the most well characterized. Vanadium nitrogenase and iron-only nitrogenase can both be found in select species of Azotobacter as an alternative nitrogenase. Equations 1 and 2 show the balanced reactions of nitrogen fixation in molybdenum nitrogenase and vanadium nitrogenase respectively.

All nitrogenases are two-component systems made up of Component I (also known as dinitrogenase) and Component II (also known as dinitrogenase reductase). Component I is a MoFe protein in molybdenum nitrogenase, a VFe protein in vanadium nitrogenase, and an Fe protein in iron-only nitrogenase. Component II is a Fe protein that contains the Fe-S cluster., which transfers electrons to Component I. Component I contains 2 metal clusters: the P-cluster, and the FeMo-cofactor (FeMo-co, M-cluster). Mo is replaced by V or Fe in vanadium nitrogenase and iron-only nitrogenase respectively. During catalysis, 2 equivalents of MgATP are hydrolysed which helps to decrease the potential of the to the Fe-S cluster and drive reduction of the P-cluster, and finally to the FeMo-co, where reduction of N2 to NH3 takes place.

Lowe-Thorneley kinetic model

The reduction of nitrogen to two molecules of ammonia is carried out at the FeMo-co of Component I after the sequential addition of proton and electron equivalents from Component II.Steady state

In systems theory, a system or a process is in a steady state if the variables (called state variables) which define the behavior of the system or the process are unchanging in time. In continuous time, this means that for those properties ''p' ...

, freeze quench, and stopped-flow kinetics measurements carried out in the 70's and 80's by Lowe, Thorneley, and others provided a kinetic basis for this process. The Lowe-Thorneley (LT) kinetic model was developed from these experiments and documents the eight correlated proton and electron transfers required throughout the reaction. Each intermediate stage is depicted as En where n = 0–8, corresponding to the number of equivalents transferred. The transfer of four equivalents are required before the productive addition of N2, although reaction of E3 with N2 is also possible. Notably, nitrogen reduction has been shown to require 8 equivalents of protons and electrons as opposed to the 6 equivalents predicted by the balanced chemical reaction.

Intermediates E0 through E4

Spectroscopic characterization of these intermediates has allowed for greater understanding of nitrogen reduction by nitrogenase, however, the mechanism remains an active area of research and debate. Briefly listed below are spectroscopic experiments for the intermediates before the addition of nitrogen: E0 – This is the resting state of the enzyme before catalysis begins. EPR characterization shows that this species has a spin of 3/2. E1 – The one electron reduced intermediate has been trapped during turnover under N2. Mӧssbauer spectroscopy of the trapped intermediate indicates that the FeMo-co is integer spin greater than 1. E2 – This intermediate is proposed to contain the metal cluster in its resting oxidation state with the two added electrons stored in a bridginghydride

In chemistry, a hydride is formally the anion of hydrogen (H−), a hydrogen ion with two electrons. In modern usage, this is typically only used for ionic bonds, but it is sometimes (and has been more frequently in the past) applied to all che ...

and the additional proton bonded to a sulfur atom. Isolation of this intermediate in mutated enzymes shows that the FeMo-co is high spin and has a spin of 3/2.

E3 – This intermediate is proposed to be the singly reduced FeMo-co with one bridging hydride and one hydride.

E4 – Termed the Janus intermediate after the Roman god of transitions, this intermediate is positioned after exactly half of the electron proton transfers and can either decay back to E0 or proceed with nitrogen binding and finish the catalytic cycle. This intermediate is proposed to contain the FeMo-co in its resting oxidation state with two bridging hydrides and two sulfur bonded protons. This intermediate was first observed using freeze quench techniques with a mutated protein in which residue 70, a valine amino acid, is replaced with isoleucine. This modification prevents substrate access to the FeMo-co. EPR characterization of this isolated intermediate shows a new species with a spin of ½. ENDOR Endor or Ein Dor may refer to:

Places

* Endor (village), from the Hebrew Bible, a Canaanite village where the Witch of Endor lived

* Indur, a Palestinian village depopulated during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war

* Ein Dor, a Kibbutz in modern Israel ...

experiments have provided insight into the structure of this intermediate, revealing the presence of two bridging hydrides. 95Mo and 57Fe ENDOR Endor or Ein Dor may refer to:

Places

* Endor (village), from the Hebrew Bible, a Canaanite village where the Witch of Endor lived

* Indur, a Palestinian village depopulated during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war

* Ein Dor, a Kibbutz in modern Israel ...

show that the hydrides bridge between two iron centers. Cryoannealing of the trapped intermediate at -20 °C results in the successive loss of two hydrogen equivalents upon relaxation, proving that the isolated intermediate is consistent with the E4 state. The decay of E4 to E2 + H2 and finally to E0 and 2H2 has confirmed the EPR signal associated with the E2 intermediate.

The above intermediates suggest that the metal cluster is cycled between its original oxidation state and a singly reduced state with additional electrons being stored in hydrides. It has alternatively been proposed that each step involves the formation of a hydride and that the metal cluster actually cycles between the original oxidation state and a singly oxidized state.

Distal and alternating pathways for N2 fixation

While the mechanism for nitrogen fixation prior to the Janus E4 complex is generally agreed upon, there are currently two hypotheses for the exact pathway in the second half of the mechanism: the "distal" and the "alternating" pathway. In the distal pathway, the terminal nitrogen is hydrogenated first, releases ammonia, then the nitrogen directly bound to the metal is hydrogenated. In the alternating pathway, one hydrogen is added to the terminal nitrogen, then one hydrogen is added to the nitrogen directly bound to the metal. This alternating pattern continues until ammonia is released. Because each pathway favors a unique set of intermediates, attempts to determine which path is correct have generally focused on the isolation of said intermediates, such as the nitrido in the distal pathway, and the diazene and

While the mechanism for nitrogen fixation prior to the Janus E4 complex is generally agreed upon, there are currently two hypotheses for the exact pathway in the second half of the mechanism: the "distal" and the "alternating" pathway. In the distal pathway, the terminal nitrogen is hydrogenated first, releases ammonia, then the nitrogen directly bound to the metal is hydrogenated. In the alternating pathway, one hydrogen is added to the terminal nitrogen, then one hydrogen is added to the nitrogen directly bound to the metal. This alternating pattern continues until ammonia is released. Because each pathway favors a unique set of intermediates, attempts to determine which path is correct have generally focused on the isolation of said intermediates, such as the nitrido in the distal pathway, and the diazene and hydrazine

Hydrazine is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a simple pnictogen hydride, and is a colourless flammable liquid with an ammonia-like odour. Hydrazine is highly hazardous unless handled in solution as, for example, hydraz ...

in the alternating pathway. Attempts to isolate the intermediates in nitrogenase itself have so far been unsuccessful, but the use of model complexes has allowed for the isolation of intermediates that support both sides depending on the metal center used. Studies with Mo generally point towards a distal pathway, while studies with Fe generally point towards an alternating pathway.

Specific support for the distal pathway has mainly stemmed from the work of Schrock and Chatt, who successfully isolated the nitrido complex using Mo as the metal center in a model complex. Specific support for the alternating pathway stems from a few studies. Iron only model clusters have been shown to catalytically reduce N2. Small tungsten

Tungsten (also called wolfram) is a chemical element; it has symbol W and atomic number 74. It is a metal found naturally on Earth almost exclusively in compounds with other elements. It was identified as a distinct element in 1781 and first ...

clusters have also been shown to follow an alternating pathway for nitrogen fixation. The vanadium nitrogenase releases hydrazine, an intermediate specific to the alternating mechanism. However, the lack of characterized intermediates in the native enzyme itself means that neither pathway has been definitively proven. Furthermore, computational studies have been found to support both sides, depending on whether the reaction site is assumed to be at Mo (distal) or at Fe (alternating) in the MoFe cofactor.

Mechanism of MgATP binding

Binding of MgATP is one of the central events to occur in the mechanism employed by nitrogenase.

Binding of MgATP is one of the central events to occur in the mechanism employed by nitrogenase. Hydrolysis

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for substitution reaction, substitution, elimination reaction, elimination, and solvation reactions in which water ...

of the terminal phosphate

Phosphates are the naturally occurring form of the element phosphorus.

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthop ...

group of MgATP provides the energy needed to transfer electrons from the Fe protein to the MoFe protein. The binding interactions between the MgATP phosphate groups and the amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

residues of the Fe protein are well understood by comparing to similar enzymes, while the interactions with the rest of the molecule are more elusive due to the lack of a Fe protein crystal structure with MgATP bound (as of 1996). Three protein residues have been shown to have significant interactions with the phosphates. In the absence of MgATP, a salt bridge

In electrochemistry, a salt bridge or ion bridge is an essential laboratory device discovered over 100 years ago. It contains an electrolyte solution, typically an inert solution, used to connect the Redox, oxidation and reduction Half cell, ...

exists between residue 15, lysine

Lysine (symbol Lys or K) is an α-amino acid that is a precursor to many proteins. Lysine contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated form when the lysine is dissolved in water at physiological pH), an α-carboxylic acid group ( ...

, and residue 125, aspartic acid

Aspartic acid (symbol Asp or D; the ionic form is known as aspartate), is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. The L-isomer of aspartic acid is one of the 22 proteinogenic amino acids, i.e., the building blocks of protei ...

. Upon binding, this salt bridge is interrupted. Site-specific mutagenesis has demonstrated that when the lysine is substituted for a glutamine

Glutamine (symbol Gln or Q) is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. Its side chain is similar to that of glutamic acid, except the carboxylic acid group is replaced by an amide. It is classified as a charge-neutral ...

, the protein's affinity for MgATP is greatly reduced and when the lysine is substituted for an arginine

Arginine is the amino acid with the formula (H2N)(HN)CN(H)(CH2)3CH(NH2)CO2H. The molecule features a guanidinium, guanidino group appended to a standard amino acid framework. At physiological pH, the carboxylic acid is deprotonated (−CO2−) a ...

, MgATP cannot bind due to the salt bridge being too strong. The necessity of specifically aspartic acid at site 125 has been shown through noting altered reactivity upon mutation of this residue to glutamic acid

Glutamic acid (symbol Glu or E; known as glutamate in its anionic form) is an α- amino acid that is used by almost all living beings in the biosynthesis of proteins. It is a non-essential nutrient for humans, meaning that the human body can ...

. Residue 16, serine, has been shown to bind MgATP. Site-specific mutagenesis was used to demonstrate this fact. This has led to a model in which the serine remains coordinated to the Mg2+ ion after phosphate hydrolysis in order to facilitate its association with a different phosphate of the now ADP molecule. MgATP binding also induces significant conformational changes within the Fe protein. Site-directed mutagenesis was employed to create mutants in which MgATP binds but does not induce a conformational change. Comparing X-ray scattering data in the mutants versus in the wild-type protein led to the conclusion that the entire protein contracts upon MgATP binding, with a decrease in radius of approximately 2.0 Å.

Other mechanistic details

Many mechanistic aspects ofcatalysis

Catalysis () is the increase in rate of a chemical reaction due to an added substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed by the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recycles quick ...

remain unknown. No crystallographic analysis has been reported on substrate bound to nitrogenase.

Nitrogenase is able to reduce acetylene, but is inhibited by carbon monoxide, which binds to the enzyme and thereby prevents binding of dinitrogen. Dinitrogen prevent acetylene binding, but acetylene does not inhibit binding of dinitrogen and requires only one electron for reduction to ethylene

Ethylene (IUPAC name: ethene) is a hydrocarbon which has the formula or . It is a colourless, flammable gas with a faint "sweet and musky" odour when pure. It is the simplest alkene (a hydrocarbon with carbon–carbon bond, carbon–carbon doub ...

. Due to the oxidative properties of oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

, most nitrogenases are irreversibly inhibited by dioxygen

There are several known allotropes of oxygen. The most familiar is molecular oxygen (), present at significant levels in Earth's atmosphere and also known as dioxygen or triplet oxygen. Another is the highly reactive ozone (). Others are:

* Ato ...

, which degradatively oxidizes the Fe-S cofactors. This requires mechanisms for nitrogen fixers to protect nitrogenase from oxygen ''in vivo

Studies that are ''in vivo'' (Latin for "within the living"; often not italicized in English) are those in which the effects of various biological entities are tested on whole, living organisms or cells, usually animals, including humans, an ...

''. Despite this problem, many use oxygen as a terminal electron acceptor for respiration. Although the ability of some nitrogen fixers such as Azotobacteraceae to employ an oxygen-labile nitrogenase under aerobic conditions has been attributed to a high metabolic rate

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cellular processes; the co ...

, allowing oxygen reduction at the cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment (the extr ...

, the effectiveness of such a mechanism has been questioned at oxygen concentrations above 70 μM (ambient concentration is 230 μM O2), as well as during additional nutrient limitations. A molecule found in the nitrogen-fixing nodules of leguminous plants, leghemoglobin

Leghemoglobin (also leghaemoglobin or legoglobin) is an oxygen-carrying phytoglobin found in the nitrogen-fixing root nodules of leguminous plants. It is produced by these plants in response to the roots being colonized by nitrogen-fixing bac ...

, which can bind to dioxygen via a heme

Heme (American English), or haem (Commonwealth English, both pronounced /Help:IPA/English, hi:m/ ), is a ring-shaped iron-containing molecule that commonly serves as a Ligand (biochemistry), ligand of various proteins, more notably as a Prostheti ...

prosthetic group, plays a crucial role in buffering O2 at the active site of the nitrogenase, while concomitantly allowing for efficient respiration.

Nonspecific reactions

In addition to dinitrogen reduction, nitrogenases also reduceprotons

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol , H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 ''e'' ( elementary charge). Its mass is slightly less than the mass of a neutron and approximately times the mass of an electron (the pro ...

to dihydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all normal matter. Under standard conditions, hydrogen is a gas of diatom ...

, meaning nitrogenase is also a dehydrogenase

A dehydrogenase is an enzyme belonging to the group of oxidoreductases that oxidizes a substrate by reducing an electron acceptor, usually NAD+/NADP+ or a flavin coenzyme such as FAD or FMN. Like all catalysts, they catalyze reverse as well as ...

. A list of other reactions carried out by nitrogenases is shown below:

: HC≡CH → H2C=CH2

: N–=N+=O → N2 + H2O

: N=N=N– → N2 + NH3

: → CH4, NH3, H3C–CH3, H2C=CH2 (CH3NH2)

:N≡C–R → RCH3 + NH3

:C≡N–R → CH4, H3C–CH3, H2C=CH2, C3H8, C3H6, RNH2

: O=C=S → CO + H2S

: O=C=O → CO + H2O

: S=C=N– → H2S + HCN

: O=C=N– → H2O + HCN, CO + NH3

Furthermore, dihydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all normal matter. Under standard conditions, hydrogen is a gas of diatom ...

functions as a competitive inhibitor

Competitive inhibition is interruption of a chemical pathway owing to one chemical substance inhibiting the effect of another by competing with it for binding or bonding. Any metabolic or chemical messenger system can potentially be affected b ...

, carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a poisonous, flammable gas that is colorless, odorless, tasteless, and slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the si ...

functions as a non-competitive inhibitor, and carbon disulfide

Carbon disulfide (also spelled as carbon disulphide) is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula and structure . It is also considered as the anhydride of thiocarbonic acid. It is a colorless, flammable, neurotoxic liquid that is used as ...

functions as a rapid-equilibrium inhibitor of nitrogenase.

Vanadium nitrogenases have also been shown to catalyze the conversion of CO into alkanes

In organic chemistry, an alkane, or paraffin (a historical trivial name that also has other meanings), is an acyclic saturated hydrocarbon. In other words, an alkane consists of hydrogen and carbon atoms arranged in a tree structure in whi ...

through a reaction comparable to Fischer-Tropsch synthesis.

Organisms that synthesize nitrogenase

There are two types of bacteria that synthesize nitrogenase and are required for nitrogen fixation. These are: * Free-living bacteria (non-symbiotic

Symbiosis (Ancient Greek : living with, companionship < : together; and ''bíōsis'': living) is any type of a close and long-term biolo ...

), examples include:

** Cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

(blue-green algae)

** Green sulfur bacteria

The green sulfur bacteria are a phylum, Chlorobiota, of obligately anaerobic photoautotrophic bacteria that metabolize sulfur.

Green sulfur bacteria are nonmotile (except ''Chloroherpeton thalassium'', which may glide) and capable of anoxyg ...

** ''Azotobacter

''Azotobacter'' is a genus of usually motile, oval or spherical bacteria that form thick-walled cysts (and also has hard crust) and may produce large quantities of capsular slime. They are aerobic, free-living soil microbes that play an impo ...

''

* Mutualistic bacteria (symbiotic), examples include:

** ''Rhizobium

''Rhizobium'' is a genus of Gram-negative soil bacteria that fix nitrogen. ''Rhizobium'' species form an endosymbiotic nitrogen-fixing association with roots of (primarily) legumes and other flowering plants.

The bacteria colonize plant ce ...

'', associated with legumes

Legumes are plants in the pea family Fabaceae (or Leguminosae), or the fruit or seeds of such plants. When used as a dry grain for human consumption, the seeds are also called pulses. Legumes are grown agriculturally, primarily for human consu ...

** ''Azospirillum

''Azospirillum'' is a Gram-negative, microaerophilic, non-fermentative and nitrogen-fixing bacterial genus from the family of Rhodospirillaceae. ''Azospirillum'' bacteria can promote plant growth.

Characteristics

The genus ''Azospirillum'' bel ...

'', associated with grass

Poaceae ( ), also called Gramineae ( ), is a large and nearly ubiquitous family (biology), family of monocotyledonous flowering plants commonly known as grasses. It includes the cereal grasses, bamboos, the grasses of natural grassland and spe ...

es

** ''Frankia

''Frankia'' is a genus of nitrogen-fixing bacteria that live in symbiosis with actinorhizal plants, similar to the '' Rhizobium'' bacteria found in the root nodules of legumes in the family Fabaceae. ''Frankia'' also initiate the forming of ro ...

'', associated with actinorhizal plant

Actinorhizal plants are a group of angiosperms characterized by their ability to form a symbiosis with the nitrogen fixing actinomycetota ''Frankia''. This association leads to the formation of nitrogen-fixing root nodules.

Actinorhizal plants ar ...

s

Evolution

Internal evolution

Nitrogenases are divided into three groups, clades, or classes, named using roman numerals I through III. The alternative nitrogenases are nested in class III. The same grouping is recovered from sequence comparison,as well as comparison ofAlphaFold

AlphaFold is an artificial intelligence (AI) program developed by DeepMind, a subsidiary of Alphabet, which performs predictions of protein structure. It is designed using deep learning techniques.

AlphaFold 1 (2018) placed first in the overall ...

2-predicted structures. Nif-I is primarily found in aerobic or at least facultatively anaerobic diazotrophs with large Nif gene families, while the two other types are almost exclusively found in anaerobic diazotrophs with smaller gene networks. (The alternative nitrogenases break this pattern as they are found to co-occur with Group I and II.) Group I cannot have diverged more than 2.5 gigayear

A year is a unit of time based on how long it takes the Earth to orbit the Sun. In scientific use, the tropical year (approximately 365 solar days, 5 hours, 48 minutes, 45 seconds) and the sidereal year (about 20 minutes longer) are more ...

s ago based on the timing of the Great Oxidation Event

The Great Oxidation Event (GOE) or Great Oxygenation Event, also called the Oxygen Catastrophe, Oxygen Revolution, Oxygen Crisis or Oxygen Holocaust, was a time interval during the Earth's Paleoproterozoic era when the Earth's atmosphere an ...

.

Ancestral sequence reconstruction has been used to reconstruct two group I nitrogenases, Anc2 representing the ancestor to all sampled nitrogenases in Gammaproteobacteria

''Gammaproteobacteria'' is a class of bacteria in the phylum ''Pseudomonadota'' (synonym ''Proteobacteria''). It contains about 250 genera, which makes it the most genus-rich taxon of the Prokaryotes. Several medically, ecologically, and scienti ...

and Anc1 representing a smaller group built around ''Azotobacter vinelandii'', ''Agaribacterium haliotis'', and environmental samples. They work more slowly than the modern ''A. vinelandii'' version but keeps a similar efficiency in ATP use (the ratio between formed H2 and reduced N2 is largely unchanged at around 2.1, with the exception of Anc1B which is more efficient.)

Similarity to other proteins

TheNif gene

The ''nif'' genes are genes encoding enzymes involved in the fixation of atmospheric nitrogen into a form of nitrogen available to living organisms. The primary enzyme encoded by the ''nif'' genes is the nitrogenase complex which is in charge of ...

s include a maturase ''NifEN'' responsible for assembling the precursor to the P-cluster called an O-cluster and transferring it onto ''NifDK''. It is also where the M-cluster is assembled with the help of nitrogenase component II ''NifH'', before it is transferred to ''NifDK''. Its structure is rather similar to the nitrogenase component I ''NifDK'', except that it usually carries a P-cluster and a L-cluster (the precursor to the M-cluster). When ''NifEN'' from ''A. vinelandii'' is expressed in ''E. coli'' with the component II ''NifH'', the resulting combination of proteins prove to work as a nitrogenase ''in vivo'', boosting the growth of transformed ''E. coli'' in a nitrogen-deficient medium. The ''YfhL'' ferredoxin naturally present in ''E. coli'' is able to work with ''NifH''. Among organisms carrying a Group III ''Nif'', ''NifN'' is only found in archaea. The reason is unclear.

One interpretation of the nitrogen-fixing ability of ''NifEN'' and its similarity to ''NifDK'' is that there used to be a single nitrogenase with P- and L- clusters, before gene duplication

Gene duplication (or chromosomal duplication or gene amplification) is a major mechanism through which new genetic material is generated during molecular evolution. It can be defined as any duplication of a region of DNA that contains a gene ...

and increased amounts of available Mo after the Great Oxidation Event

The Great Oxidation Event (GOE) or Great Oxygenation Event, also called the Oxygen Catastrophe, Oxygen Revolution, Oxygen Crisis or Oxygen Holocaust, was a time interval during the Earth's Paleoproterozoic era when the Earth's atmosphere an ...

allowed for the current situation to evolve (one copy became ''NifEN'' with the gain of M-cluster, the other became ''NifDK'' with the loss of P-cluster). Isotopic data suggests that Mo-based nitrogen fixation is no younger than 3.2 gigayear

A year is a unit of time based on how long it takes the Earth to orbit the Sun. In scientific use, the tropical year (approximately 365 solar days, 5 hours, 48 minutes, 45 seconds) and the sidereal year (about 20 minutes longer) are more ...

s old. There is also a similarity between the α and β subunits in nitrogenase, its maturase, and related proteins; the two halves might have been a single gene of unknown function to begin with and became duplicated before nitrogenase diverged from BChNB. A large 2022 study mostly supports the view about ''NifEN'' and ''NifDK'' being formed by a duplication.

The three subunits of nitrogenase exhibit significant sequence similarity to three subunits of the light-independent version of protochlorophyllide reductase (DPOR, (ChlNB)2 + ChlL2) that performs the conversion of protochlorophyllide to chlorophyll

Chlorophyll is any of several related green pigments found in cyanobacteria and in the chloroplasts of algae and plants. Its name is derived from the Greek words (, "pale green") and (, "leaf"). Chlorophyll allows plants to absorb energy ...

. This protein is present in gymnosperm

The gymnosperms ( ; ) are a group of woody, perennial Seed plant, seed-producing plants, typically lacking the protective outer covering which surrounds the seeds in flowering plants, that include Pinophyta, conifers, cycads, Ginkgo, and gnetoph ...

s, algae, and photosynthetic bacteria but has been lost by angiosperms during evolution. The structual similarity puts it in the same superfamily as nitrogenase. The enzyme for bacteriochlorophyll

Bacteriochlorophylls (BChl) are photosynthetic pigments that occur in various phototrophic bacteria. They were discovered by C. B. van Niel in 1932. They are related to chlorophylls, which are the primary pigments in plants, algae, and cyanobacte ...

is similar and is called chlorophyllide oxidoreductase (COR, (BchNB)2 + BchL2 or (BchYZ)2 + BchX2).

Separately, two of the nitrogenase subunits (NifD and NifH) have homologues in methanogen

Methanogens are anaerobic archaea that produce methane as a byproduct of their energy metabolism, i.e., catabolism. Methane production, or methanogenesis, is the only biochemical pathway for Adenosine triphosphate, ATP generation in methanogens. A ...

s that do not fix nitrogen e.g. ''Methanocaldococcus jannaschii

''Methanocaldococcus jannaschii'' (formerly ''Methanococcus jannaschii'') is a thermophile, thermophilic methanogenic archaean in the class Methanococci. It was the first archaeon, and third organism, to have its complete genome genome sequencing ...

''. Little is understood about the function of these "class IV" ''nif'' genes as of 2004, though they occur in many methanogens. In ''M. jannaschii'' they are known to interact with each other and are constitutively expressed. The "group IV" ''Nif'' are closer to ''Nif''-I/II/III (the real nitrogenases) than DPOR and COR are. They do not have the DK vs EN duplication. The group has previously been considered paraphyletic, but a more recent analysis finds it monophyletic

In biological cladistics for the classification of organisms, monophyly is the condition of a taxonomic grouping being a clade – that is, a grouping of organisms which meets these criteria:

# the grouping contains its own most recent co ...

. There are two known kinds of functions: the ''CfbC'' type makes coenzyme F430 and the ''Mar'' type can make methionine, ethylene, and methane.

Measurement of nitrogenase activity

As with many assays for enzyme activity, it is possible to estimate nitrogenase activity by measuring the rate of conversion of the substrate (N2) to the product (NH3). Since NH3 is involved in other reactions in the cell, it is often desirable to label the substrate with 15N to provide accounting or "mass balance" of the added substrate. A more common assay, the acetylene reduction assay or ARA, estimates the activity of nitrogenase by taking advantage of the ability of the enzyme to reduce acetylene gas to ethylene gas. These gases are easily quantified using gas chromatography. Though first used in a laboratory setting to measure nitrogenase activity in extracts of '' Clostridium pasteurianum'' cells, ARA has been applied to a wide range of test systems, including field studies where other techniques are difficult to deploy. For example, ARA was used successfully to demonstrate that bacteria associated with rice roots undergo seasonal and diurnal rhythms in nitrogenase activity, which were apparently controlled by the plant. Unfortunately, the conversion of data from nitrogenase assays to actual moles of N2 reduced (particularly in the case of ARA), is not always straightforward and may either underestimate or overestimate the true rate for a variety of reasons. For example, H2 competes with N2 but not acetylene for nitrogenase (leading to overestimates of nitrogenase by ARA). Bottle or chamber-based assays may produce negative impacts on microbial systems as a result of containment or disruption of the microenvironment through handling, leading to underestimation of nitrogenase. Despite these weaknesses, such assays are very useful in assessing relative rates or temporal patterns in nitrogenase activity.See also

*Nitrogen fixation

Nitrogen fixation is a chemical process by which molecular dinitrogen () is converted into ammonia (). It occurs both biologically and abiological nitrogen fixation, abiologically in chemical industry, chemical industries. Biological nitrogen ...

* Abiological nitrogen fixation

References

Further reading

*External links

* {{Portal bar, Biology, border=no EC 1.18.6 Iron–sulfur proteins Nitrogen cycle Molybdenum enzymes