De Soto Expedition on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1497 – 21 May 1542) was a Spanish explorer and conquistador who was involved in expeditions in

In May 1539, de Soto landed nine ships with over 620 men and 220 horses in an area generally identified as south

In May 1539, de Soto landed nine ships with over 620 men and 220 horses in an area generally identified as south

De Soto headed north into the

De Soto headed north into the

In the spring of 1541, de Soto demanded 200 men as porters from the

In the spring of 1541, de Soto demanded 200 men as porters from the

''Caddo Indians: Where We Come From''.

Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001: 21. This may have happened in the area of present-day

De Soto died of a fever on 21 May 1542, in the native village of ''

De Soto died of a fever on 21 May 1542, in the native village of ''

pp. 349–352 "Death of de Soto"

Louisiana erected a historical marker at the conjectured site on the western bank of the Mississippi River. Before his death, de Soto chose Luis de Moscoso Alvarado, his former maestro de campo (or field commander), to assume command of the expedition. At the time of death, de Soto owned four Indian slaves, three horses, and 700 hogs. De Soto had deceived the local natives into believing that he was a deity, specifically an "immortal Son of the Sun", to gain their submission without conflict. Some of the natives had already become skeptical of de Soto's deity claims, so his men were anxious to conceal his death. The actual site of his burial is not known. According to one source, de Soto's men hid his corpse in blankets weighted with sand and sank it in the middle of the Mississippi River during the night.

Many parks, towns, counties, and institutions have been named after Hernando de Soto, to include:

Many parks, towns, counties, and institutions have been named after Hernando de Soto, to include:

* DeSoto automobile line developed by the

* DeSoto automobile line developed by the

online

* * Albert, Steve: ''Looking Back......Natural Steps''; Pinnacle Mountain Community Post 1991. * Henker, Fred O., M.D. ''Natural Steps, Arkansas'', Arkansas History Commission 1999. * Jennings, John. (1959) ''The Golden Eagle.'' Dell. * MacQuarie, Kim. (2007) ''The last days of the Incas.'' Simon & Schuster. * Maura, Juan Francisco. ''Españolas de ultramar''. Valencia

Universidad de Valencia

2005. * *

online review

* van de Logt, Mark. "The Old Man with the Iron-Nosed Mask:" Caddo Oral Tradition and the De Soto Expedition, 1541–42"." ''Western Folklore'' (2016): 191–222

online

* Wesson, Cameron B. "de Soto (Probably) Never Slept Here: Archaeology, Memory, Myth, and Social Identity." ''International Journal of Historical Archaeology'' 16.2 (2012): 418–435.

Hernando de Soto Profile and Videos

– Chickasaw.TV

*

The chequered origins of chess in Peru: the Inca emperor turned pawn

{{DEFAULTSORT:Soto, Hernando De Spanish slave owners Spanish explorers of North America Spanish explorers of South America Explorers of the colonial Southwest of the United States Year of birth uncertain 1542 deaths 16th-century Spanish explorers Extremaduran conquistadors People from Sierra Suroeste Governors of Cuba Explorers of Spanish Florida 16th-century Spanish military personnel

Nicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro

Francisco Pizarro, Marquess of the Atabillos (; ; – 26 June 1541) was a Spanish ''conquistador'', best known for his expeditions that led to the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire.

Born in Trujillo, Cáceres, Trujillo, Spain, to a poor fam ...

's conquest of the Inca Empire

The Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire, also known as the Conquest of Peru, was one of the most important campaigns in the Spanish colonization of the Americas. After years of preliminary exploration and military skirmishes, 168 Spanish sol ...

in Peru, but is best known for leading the first European expedition deep into the territory of the modern-day United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

(through Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

, Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

, Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

, North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

, South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

, Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

, and most likely Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the West South Central region of the Southern United States. It borders Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, and Oklahoma ...

). He is the first European documented as having crossed the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

.

De Soto's North American expedition was a vast undertaking. It ranged throughout what is now the southeastern United States

The Southeastern United States, also known as the American Southeast or simply the Southeast, is a geographical List of regions in the United States, region of the United States located in the eastern portion of the Southern United States and t ...

, searching both for gold, which had been reported by various Native American

Native Americans or Native American usually refers to Native Americans in the United States.

Related terms and peoples include:

Ethnic groups

* Indigenous peoples of the Americas, the pre-Columbian peoples of North, South, and Central America ...

tribes and earlier coastal explorers, and for a passage to China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

or the Pacific coast. De Soto died in 1542 on the banks of the Mississippi River; sources disagree on the exact location, whether it was what is now Lake Village, Arkansas

Lake Village is a city in and the county seat of Chicot County, Arkansas, Chicot County, Arkansas, United States. The population was 2,575 at the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census. It is located in the Arkansas Delta. Lake Village is name ...

, or Ferriday, Louisiana

Ferriday is a town in Concordia Parish, Louisiana, Concordia Parish, which borders the Mississippi River and is located on the central eastern border of Louisiana, United States. With a population of 3,511 at the 2010 United States Census, 2010 ...

.

Early life

Hernando de Soto was born around the late 1490s or early 1500s inExtremadura

Extremadura ( ; ; ; ; Fala language, Fala: ''Extremaúra'') is a landlocked autonomous communities in Spain, autonomous community of Spain. Its capital city is Mérida, Spain, Mérida, and its largest city is Badajoz. Located in the central- ...

, Spain, to parents who were both ''hidalgos

Hidalgo may refer to:

People

* Hidalgo (nobility), members of the Spanish nobility

* Hidalgo (surname)

Places

Mexico

:''Most, if not all, named for Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla (1753–1811)''

* Hidalgo (state), in central Mexico

* Hidalgo, Coah ...

'', nobility of modest means. The region was poor and many people struggled to survive; young people looked for ways to seek their fortune elsewhere. He was born in the current province of Badajoz. Three towns—Badajoz

Badajoz is the capital of the Province of Badajoz in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Extremadura, Spain. It is situated close to the Portugal, Portuguese Portugal–Spain border, border, on the left bank of the river ...

, Barcarrota

Barcarrota is a Spanish municipality in the province of Badajoz, Extremadura. It has a population of 3,664 (2007) and an area of 136.1 km².

Barcarrota was the location of the Battle of Villanueva de Barcarrota (1336), in which Castilian tro ...

and Jerez de los Caballeros

Jerez de los Caballeros () is a town of south-western Spain, in the province of Badajoz. It is located on two hills overlooking the River Ardila, a tributary of the Guadiana, 18 km east of the Portuguese border. The old town is surrounded by ...

—each claim to be his birthplace. Historian Ursula Lamb writes that the Barcarrota claim can be traced to Inca Garcilaso de la Vega

Inca Garcilaso de la Vega (12 April 1539 – 23 April 1616), born Gómez Suárez de Figueroa and known as El Inca, was a chronicler and writer born in the Viceroyalty of Peru. Sailing to Spain at 21, he was educated informally there, where he li ...

and is probably incorrect, having been written down 45 years after De Soto's death. According to Lamb, his birthplace is most likely Jerez de los Caballeros. Although he spent time as a child at each place, De Soto stipulated in his will that his body be interred at Jerez de los Caballeros, where other members of his family were buried.

A few years before his birth, the Kingdoms of Castille and Aragon conquered

Conquest involves the annexation or control of another entity's territory through war or coercion. Historically, conquests occurred frequently in the international system, and there were limited normative or legal prohibitions against conquest ...

the last Islamic kingdom of the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

. Spain and Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

were filled with young men seeking a chance for military fame after the defeat of the Moors

The term Moor is an Endonym and exonym, exonym used in European languages to designate the Muslims, Muslim populations of North Africa (the Maghreb) and the Iberian Peninsula (particularly al-Andalus) during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a s ...

. With Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

's discovery of new lands (which he thought to be East Asia

East Asia is a geocultural region of Asia. It includes China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan, plus two special administrative regions of China, Hong Kong and Macau. The economies of Economy of China, China, Economy of Ja ...

) across the ocean to the west, young men were attracted to rumors of adventure, glory and wealth.

In the New World

De Soto sailed to theNew World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

with Pedro Arias Dávila

Pedro Arias de Ávila (c. 1440 – 6 March 1531; often Pedro Arias Dávila or Pedrarias Dávila) was a Spanish soldier and colonial administrator. He led the first great Spanish expedition to the mainland of the Americas. There, he served as go ...

, appointed as the first Governor of Panama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

. In 1520 he participated in Gaspar de Espinosa

Gaspar de Espinosa y Luna ( Medina de Rioseco, Spain, c. 1484 - Cuzco, Peru, 14 February 1537) was a Spanish explorer, conquistador and politician. He participated in the expedition of Pedro Arias Dávila to Darién and was appointed mayor of Sant ...

's expedition to Veragua

The name Veragua or Veraguas was used for five Spanish colonial territorial entities in Central America, beginning in the 16th century during the Spanish colonization of the Americas.

The term comes from the name given to the region by Central Am ...

, and in 1524, he participated in the conquest of Nicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

under Francisco Hernández de Córdoba

Francisco is the Spanish and Portuguese form of the masculine given name ''Franciscus''.

Meaning of the name Francisco

In Spanish, people with the name Francisco are sometimes nicknamed " Paco". San Francisco de Asís was known as ''Pater Comm ...

. There he acquired an ''encomienda

The ''encomienda'' () was a Spanish Labour (human activity), labour system that rewarded Conquistador, conquerors with the labour of conquered non-Christian peoples. In theory, the conquerors provided the labourers with benefits, including mil ...

'' and a public office in León, Nicaragua

León () is the second largest city in Nicaragua, after Managua. Founded by the Spanish as Santiago de los Caballeros de León, it is the capital and largest city of León Department. , the municipality of León has an estimated population of ...

.

Brave leadership, unwavering loyalty, and ruthless schemes for the extortion of native villages for their captured chiefs became de Soto's hallmarks during the conquest of Central America. He gained fame as an excellent horseman, fighter, and tactician. During that time, de Soto was influenced by the achievements of Iberian explorers: Juan Ponce de León

Juan Ponce de León ( – July 1521) was a Spanish explorer and ''conquistador'' known for leading the first official European expedition to Puerto Rico in 1508 and Florida in 1513. He was born in Santervás de Campos, Valladolid, Spain, in ...

, the first European to reach Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

; Vasco Núñez de Balboa

Vasco Núñez de Balboa (; c. 1475around January 12–21, 1519) was a Spanish people, Spanish explorer, governor, and conquistador. He is best known for crossing the Isthmus of Panama to the Pacific Ocean in 1513, becoming the first European to ...

, the first European to reach the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

coast of the Americas (he called it the "South Sea" on the south coast of Panama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

); and Ferdinand Magellan

Ferdinand Magellan ( – 27 April 1521) was a Portuguese explorer best known for having planned and led the 1519–22 Spanish expedition to the East Indies. During this expedition, he also discovered the Strait of Magellan, allowing his fl ...

, who first sailed that ocean to East Asia

East Asia is a geocultural region of Asia. It includes China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan, plus two special administrative regions of China, Hong Kong and Macau. The economies of Economy of China, China, Economy of Ja ...

.

In 1530, de Soto became a ''regidor

A regidor (plural: ''regidores'') is a member of a council of municipalities in Spain and Latin America. Portugal also used to have the same office of ''regedor''.

Mexico

In Mexico, an ayuntamiento (municipal council) is composed of a municipa ...

'' of León, Nicaragua

León () is the second largest city in Nicaragua, after Managua. Founded by the Spanish as Santiago de los Caballeros de León, it is the capital and largest city of León Department. , the municipality of León has an estimated population of ...

. He led an expedition up the coast of the Yucatán Peninsula

The Yucatán Peninsula ( , ; ) is a large peninsula in southeast Mexico and adjacent portions of Belize and Guatemala. The peninsula extends towards the northeast, separating the Gulf of Mexico to the north and west of the peninsula from the C ...

searching for a passage between the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

and the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

to enable trade with the Orient, the richest market in the world. Failing that, and without means to explore further, de Soto, upon Pedro Arias Dávila

Pedro Arias de Ávila (c. 1440 – 6 March 1531; often Pedro Arias Dávila or Pedrarias Dávila) was a Spanish soldier and colonial administrator. He led the first great Spanish expedition to the mainland of the Americas. There, he served as go ...

's death, left his estates in Nicaragua. Bringing his own men on ships which he hired, de Soto joined Francisco Pizarro

Francisco Pizarro, Marquess of the Atabillos (; ; – 26 June 1541) was a Spanish ''conquistador'', best known for his expeditions that led to the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire.

Born in Trujillo, Cáceres, Trujillo, Spain, to a poor fam ...

at his first base of Tumbes shortly before departure for the interior of present-day Peru

Peru, officially the Republic of Peru, is a country in western South America. It is bordered in the north by Ecuador and Colombia, in the east by Brazil, in the southeast by Bolivia, in the south by Chile, and in the south and west by the Pac ...

.Prescott, W.H., (2011) ''The History of the Conquest of Peru,'' Digireads.com Publishing,

Pizarro quickly made de Soto one of his captains.

Conquest of Peru

When Pizarro and his men first encountered the army of IncaAtahualpa

Atahualpa (), also Atawallpa or Ataw Wallpa ( Quechua) ( 150226 July 1533), was the last effective Inca emperor, reigning from April 1532 until his capture and execution in July of the following year, as part of the Spanish conquest of the In ...

at Cajamarca

Cajamarca (), also known by the Quechua name, ''Kashamarka'', is the capital and largest city of the Cajamarca Region as well as an important cultural and commercial center in the northern Andes. It is located in the northern highlands of Per ...

, Pizarro sent de Soto with fifteen men to invite Atahualpa to a meeting. When Pizarro's men attacked Atahualpa and his guard the next day (the Battle of Cajamarca

The Battle of Cajamarca, also spelled Cajamalca (though many contemporary scholars prefer to call it the Cajamarca massacre), was the ambush and seizure of the Incan ruler Atahualpa by a small Spanish force led by Francisco Pizarro, on November ...

), de Soto led one of the three groups of mounted soldiers. The Spanish captured Atahualpa. De Soto was sent to the camp of the Inca

The Inca Empire, officially known as the Realm of the Four Parts (, ), was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The administrative, political, and military center of the empire was in the city of Cusco. The History of the Incas, Inca ...

army, where he and his men plundered Atahualpa's tents.

During 1533, the Spanish held Atahualpa captive in Cajamarca for months while his subjects paid for his ransom by filling a room with gold and silver objects. During this captivity, de Soto became friendly with Atahualpa and taught him to play chess

Chess is a board game for two players. It is an abstract strategy game that involves Perfect information, no hidden information and no elements of game of chance, chance. It is played on a square chessboard, board consisting of 64 squares arran ...

. By the time the ransom had been completed, the Spanish became alarmed by rumors of an Inca army advancing on Cajamarca. Pizarro sent de Soto with 200 soldiers to scout for the rumored army.Von Hagen, Victor W., 1955, "De Soto and the Golden Road", '' American Heritage'', August 1955, ''Vol. VI, No. 5'', American Heritage Publishing

''American Heritage'' is a magazine dedicated to covering the history of the United States for a mainstream readership. Until 2007, the magazine was published by Forbes.

, New York pp. 32–37

While de Soto was gone, the Spanish in Cajamarca decided to kill Atahualpa to prevent his rescue. De Soto returned to report that he found no signs of an army in the area. After executing Atahualpa, Pizarro and his men headed to Cuzco

Cusco or Cuzco (; or , ) is a city in southeastern Peru, near the Sacred Valley of the Andes mountain range and the Huatanay river. It is the capital of the eponymous province and department.

The city was the capital of the Inca Empire unti ...

, the capital of the Incan Empire. As the Spanish force approached Cuzco, Pizarro sent his brother Hernando and de Soto ahead with 40 men. The advance guard fought a pitched battle with Inca troops in front of the city, but the battle had ended before Pizarro arrived with the rest of the Spanish party. The Inca army withdrew during the night. The Spanish plundered Cuzco, where they found much gold and silver. As a mounted soldier, de Soto received a share of the plunder, which made him very wealthy. It represented riches from Atahualpa's camp, his ransom, and the plunder from Cuzco.

On the road to Cuzco, Manco Inca Yupanqui

Manco Inca Yupanqui (1544) was the founder and first Sapa Inca of the independent Neo-Inca State in Vilcabamba, Peru, Vilcabamba, although he was originally a Puppet government, puppet Inca Emperor installed by the Spaniards. He was also known ...

, a brother of Atahualpa, had joined Pizarro. Manco had been hiding from Atahualpa in fear of his life, and was happy to gain Pizarro's protection. Pizarro arranged for Manco to be installed as the Inca leader. De Soto joined Manco in a campaign to eliminate the Inca armies under Quizquiz

''QuizQuiz'' (), also known as ''Quiz Quiz'', was a massively multiplayer online (MMO) quiz video game created by Nexon which used a super deformed type anime graphical style to portray the players and the few environments or non-player chara ...

, a general who had been loyal to Atahualpa.Yupanqui, T.C., 2005, ''An Inca Account of the Conquest of Peru,'' Boulder

In geology, a boulder (or rarely bowlder) is a rock fragment with size greater than in diameter. Smaller pieces are called cobbles and pebbles. While a boulder may be small enough to move or roll manually, others are extremely massive. In ...

: University Press of Colorado

The University Press of Colorado is a nonprofit publisher that was established in 1965. It is currently a member of the Association of University Presses and has been since 1982.

Initially associated with Colorado public universities, the Univ ...

,

By 1534, de Soto was serving as lieutenant governor of Cuzco while Pizarro was building his new capital on the coast; it later became known as Lima

Lima ( ; ), founded in 1535 as the Ciudad de los Reyes (, Spanish for "City of Biblical Magi, Kings"), is the capital and largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón River, Chillón, Rímac River, Rímac and Lurín Rive ...

. In 1535 King Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''* ...

awarded Diego de Almagro

Diego de Almagro (; – July 8, 1538), also known as El Adelantado and El Viejo, was a Spanish conquistador known for his exploits in western South America. He participated with Francisco Pizarro in the Spanish conquest of Peru. While subduing ...

, Francisco Pizarro's partner, the governorship of the southern portion of the Inca Empire. When de Almagro made plans to explore and conquer the southern part of the Inca empire (now Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

), de Soto applied to be his second-in-command, but de Almagro turned him down. De Soto packed up his treasure and returned to Spain.

Return to Spain

De Soto returned to Spain in 1536, with wealth gathered from plunder in theSpanish conquest of the Inca Empire

The Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire, also known as the Conquest of Peru, was one of the most important campaigns in the Spanish colonization of the Americas. After years of preliminary exploration and military skirmishes, 168 Spaniards, ...

. He was admitted into the prestigious Order of Santiago

The Order of Santiago (; ) is a religious and military order founded in the 12th century. It owes its name to the patron saint of Spain, ''Santiago'' ( St. James the Greater). Its initial objective was to protect the pilgrims on the Way of S ...

and "granted the right to conquer Florida". His share was awarded to him by the King of Spain, and he received 724 marks of gold, and 17,740 pesos.Von Hagen, Victor W., 1955, "De Soto and the Golden Road", ''American Heritage'', August 1955, ''Vol. VI, No. 5'', American Heritage Publishing, New York, pp. 102–103. He married Isabel de Bobadilla

Isabel de Bobadilla, or Inés de Bobadilla (c. 1505–1554) was the first female governor of Cuba from 1539–1543.

Background

Isabel was born to a family closely associated with the exploration and conquest of the Americas. She was the third ...

, daughter of Pedrarias Dávila and a relative of a confidante of Queen Isabella.

De Soto petitioned King Charles

King Charles may refer to:

Kings

A number of kings of Albania, Alençon, Anjou, Austria, Bohemia, Croatia, England, France, Holy Roman Empire, Hungary, Ireland, Jerusalem, Naples, Navarre, Norway, Portugal, Romania, Sardinia, Scotland, Sicily, S ...

to lead the government of Guatemala

Guatemala, officially the Republic of Guatemala, is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the north and west by Mexico, to the northeast by Belize, to the east by Honduras, and to the southeast by El Salvador. It is hydrologically b ...

, with "permission to create discovery in the South Sea." He was granted the governorship of Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

instead. De Soto was expected to colonize the North American continent for Spain within 4 years, for which his family would be given a sizable piece of land.

Fascinated by the stories of Cabeza de Vaca

In Mexican cuisine, ''cabeza'' (''lit.'' 'head'), from barbacoa de cabeza, is the meat from a roasted beef head, served as taco or burrito fillings. It typically refers to barbacoa de cabeza or beef-head barbacoa, an entire beef-head traditionall ...

, who had survived years in North America after becoming a castaway and had just returned to Spain, de Soto selected 620 Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many countries in the Americas

**Spanish cuisine

**Spanish history

**Spanish culture

...

and Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

volunteers, including some of mixed-race African descent known as Atlantic Creoles, to accompany him to govern Cuba and colonize North America. Averaging 24 years of age, the men embarked from Havana

Havana (; ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.ships

A ship is a large vessel that travels the world's oceans and other navigable waterways, carrying cargo or passengers, or in support of specialized missions, such as defense, research and fishing. Ships are generally distinguished from boats, ...

and two caravel

The caravel (Portuguese language, Portuguese: , ) is a small sailing ship developed by the Portuguese that may be rigged with just lateen sails, or with a combination of lateen and Square rig, square sails. It was known for its agility and s ...

s of de Soto's. With tons of heavy armor

Armour (Commonwealth English) or armor (American English; see American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, spelling differences) is a covering used to protect an object, individual, or vehicle from physical injury or damage, e ...

and equipment, they also carried more than 500 head of livestock, including 237 horses and 200 pigs, for their planned four-year continental expedition.

De Soto wrote a new will upon arriving in what is now the Tampa Bay area of Florida. On 10 May 1539, he wrote in his will:

That a chapel be erected within the Church of San Miguel in Jerez de Los Caballeros, Spain, where De Soto grew up, at a cost of 2,000 ducats, with an altarpiece featuring the Virgin Mary,Our Lady of the Conception The Immaculate Conception is the doctrine that the Virgin Mary was free of original sin from the moment of her conception. It is one of the four Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church. Debated by medieval theologians, it was not defined as a ..., that his tomb be covered in a fine black broadcloth topped by a red cross of the Order of the Knights of Santiago, and on special occasions a pall of black velvet with the De Soto coat of arms be placed on the altar; that a chaplain be hired at the salary of 12,000 maravedis to perform five masses every week for the souls of De Soto, his parents, and wife; that thirty masses be said for him the day his body was interred, and twenty for our Lady of the Conception, ten for theHoly Ghost Most Christian denominations believe the Holy Spirit, or Holy Ghost, to be the third divine Person of the Trinity, a triune god manifested as God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit, each being God. Nontrinitarian Christians, who ..., sixty for souls inpurgatory In Christianity, Purgatory (, borrowed into English language, English via Anglo-Norman language, Anglo-Norman and Old French) is a passing Intermediate state (Christianity), intermediate state after physical death for purifying or purging a soul ...and masses for many others as well; that 150000 maravedis be given annually to his wife Isabel for her needs and an equal amount used yearly to marry off three orphan damsels...the poorest that can be found," to assist his wife and also serve to burnish the memory of De Soto as a man of charity and substance.

De Soto's exploration of North America

Historiography

Historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human species; as well as the ...

s have worked to trace the route of de Soto's expedition in North America, a controversial process over the years. Local politicians vied to have their localities associated with the expedition. The most widely used version of "De Soto's Trail" comes from a study commissioned by the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature, legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, including a Lower house, lower body, the United States House of Representatives, ...

. A committee chaired by the anthropologist

An anthropologist is a scientist engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropologists study aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms, values ...

John R. Swanton

John Reed Swanton (February 19, 1873 – May 2, 1958) was an American anthropologist, folklorist, and linguist who worked with Native American peoples throughout the United States. Swanton achieved recognition in the fields of ethnology and ethn ...

published ''The Final Report of the United States De Soto Expedition Commission'' in 1939. Among other locations, Manatee County, Florida

Manatee County is a county in the U.S. state of Florida. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 U.S. Census, the population was 399,710. Manatee County is part of the Bradenton-Sarasota-Venice, Florida Metropolitan Statistical Area, North Por ...

, claims an approximate landing site for de Soto and has a national memorial recognizing that event. In the early 21st century, the first part of the expedition's course, up to de Soto's battle at Mabila

Mabila (also spelled Mavila, Mavilla, Maubila, or Mauvilla, as influenced by Spanish or French transliterations) was a small fortress town known to the paramount chief Tuskaloosa in 1540, in a region of present-day central Alabama. The exact loca ...

(a small fortress town in present-day central Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

), is disputed only in minor details. His route beyond Mabila is contested. Swanton reported the de Soto trail ran from there through Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

, Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the West South Central region of the Southern United States. It borders Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, and Oklahoma ...

, and Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

.

Historians have more recently considered archeological

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscapes. Archaeology ...

reconstructions and the oral history

Oral history is the collection and study of historical information from

people, families, important events, or everyday life using audiotapes, videotapes, or transcriptions of planned interviews. These interviews are conducted with people who pa ...

of the various Native American

Native Americans or Native American usually refers to Native Americans in the United States.

Related terms and peoples include:

Ethnic groups

* Indigenous peoples of the Americas, the pre-Columbian peoples of North, South, and Central America ...

peoples who recount the expedition. Most historical places have been overbuilt and much evidence has been lost. More than 450 years have passed between the events and current history tellers, but some oral histories have been found to be accurate about historic events that have been otherwise documented.

The Governor Martin Site at the former Apalachee

The Apalachee were an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, specifically an Indigenous people of Florida, who lived in the Florida Panhandle until the early 18th century. They lived between the Aucilla River and Ochlockonee River,Bobby ...

village of Anhaica

Anhaica (also known as Iviahica, Yniahico, and pueblo of Apalache) was the principal town of the Apalachee people, located in what is now Tallahassee, Florida. In the early period of Spanish colonization, it was the capital of the Apalachee Pro ...

, located about a mile east of the present-day Florida state capitol in Tallahassee

Tallahassee ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Florida. It is the county seat of and the only incorporated municipality in Leon County. Tallahassee became the capital of Florida, then the Florida Territory, in 1824. In 2024, the est ...

, has been documented as definitively associated with de Soto's expedition. The Governor Martin Site was discovered by archaeologist B. Calvin Jones in March 1987. It has been preserved as the DeSoto Site Historic State Park

DeSoto Site Historic State Park is a Florida state park located in Tallahassee, Florida. It consists of of land near Apalachee Parkway, including the residence of former Governor John W. Martin. The site is intended to initiate research and ...

.

The Hutto/Martin Site, 8MR3447, in southeastern Marion County, Florida

Marion County is a county located in the North Central region of the U.S. state of Florida. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 375,908. Its county seat is Ocala. Marion County comprises the Ocala, Florida Metropolitan S ...

, on the Ocklawaha River

The U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 21, 2011 Ocklawaha River flows north from central Florida until it joins the St. Johns River near Palatka. Its name is deriv ...

, is the most likely site of the principal town of ''Acuera'' referred to in the accounts of the ''entrada'', as well as the site of the seventeenth-century mission of Santa Lucia de Acuera.

As of 2016, the Richardson/UF Village site (8AL100) in Alachua County

Alachua County ( ) is a county in the north central portion of the U.S. state of Florida. As of the 2020 census, the population was 278,468. The county seat is Gainesville, the home of the University of Florida.

History Prehistory and ear ...

, west of Orange Lake, appears to have been accepted by archaeologists as the site of the town of Potano visited by the de Soto expedition. The 17th-century mission of San Buenaventura de Potano

San Buenaventura de Potano was a Spanish mission near Orange Lake (Florida), Orange Lake in southern Alachua County, Florida, Alachua County or northern Marion County, Florida, located on the site where the town of Potano had been located when it w ...

is believed to have been founded here.

Many archaeologists believe the Parkin Archeological State Park

Parkin Archeological State Park, also known as Parkin Indian Mound, is an archeological site and state park in Parkin, Cross County, Arkansas. Around 1350–1650 CE an aboriginal palisaded village existed at the site, at the confluence ...

in northeast Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the West South Central region of the Southern United States. It borders Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, and Oklahoma ...

was the main town for the indigenous province of Casqui

Casqui was a Native American polity visited in 1541 by the Hernando de Soto expedition. This group inhabited fortified villages in eastern Arkansas.

The tribe takes its name from the chieftain Casqui, who ruled the tribe from its primary villag ...

, which de Soto had recorded. They base this on similarities between descriptions from the journals of the de Soto expedition and artifacts of European origin discovered at the site in the 1960s.

Theories of de Soto's route are based on the accounts of four chroniclers of the expedition.

* The first account of the expedition to be published was by the Gentleman of Elvas, an otherwise unidentified Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

knight who was a member of the expedition. His chronicle was first published in 1557. An English translation by Richard Hakluyt

Richard Hakluyt (; 1553 – 23 November 1616) was an English writer. He is known for promoting the British colonization of the Americas, English colonization of North America through his works, notably ''Divers Voyages Touching the Discov ...

was published in 1609.

* Luys Hernández de Biedma, the King's factor (the agent responsible for the royal property) with the expedition, wrote a report which still exists. The report was filed in the royal archives in Spain in 1544. The manuscript was translated into English by Buckingham Smith and published in 1851.

* De Soto's secretary, Rodrigo Ranjel, kept a diary, which has been lost. It was apparently used by Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés (August 1478 – 1557), commonly known as Oviedo, was a Spanish soldier, historian, writer, botanist and colonist. Oviedo participated in the Spanish colonization of the West Indies, arriving in the first fe ...

in writing his ''La historia general y natural de las Indias''. Oviedo died in 1557. The part of his work containing Ranjel's diary was not published until 1851. An English translation of Ranjel's report was first published in 1904.

* The fourth chronicle is by Garcilaso de la Vega, known as ''El Inca'' (the Inca). Garcilaso de la Vega did not participate in the expedition. He wrote his account, ''La Florida'', known in English as ''The Florida of the Inca'', decades after the expedition, based on interviews with some survivors of the expedition. The book was first published in 1605. Historians have identified problems with using ''La Florida'' as a historical account. Milanich and Hudson

Hudson may refer to:

People

* Hudson (given name)

* Hudson (surname)

* Hudson (footballer, born 1986), Hudson Fernando Tobias de Carvalho, Brazilian football right-back

* Hudson (footballer, born 1988), Hudson Rodrigues dos Santos, Brazilian f ...

warn against relying on Garcilaso, noting serious problems with the sequence and location of towns and events in his narrative. They say, "some historians regard Garcilaso's ''La Florida'' to be more a work of literature than a work of history." Lankford characterizes Garcilaso's ''La Florida'' as a collection of "legend

A legend is a genre of folklore that consists of a narrative featuring human actions, believed or perceived to have taken place in human history. Narratives in this genre may demonstrate human values, and possess certain qualities that give the ...

narratives", derived from a much-retold oral tradition of the survivors of the expedition.

Milanich and Hudson warn that older translations of the chronicles are often "relatively free translations in which the translators took considerable liberty with the Spanish and Portuguese text."

The chronicles describe de Soto's trail in relation to Havana

Havana (; ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

, which they skirted while traveling inland then turned back to later; the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

, which they approached during their second year; high mountains, which they traversed immediately thereafter; and dozens of other geographic features along their way, such as large rivers and swamps, at recorded intervals. Given that the natural geography has not changed much since de Soto's time, scholars have analyzed those journals with modern topographic intelligence, to develop a more precise account of the De Soto Trail.

1539: Florida

In May 1539, de Soto landed nine ships with over 620 men and 220 horses in an area generally identified as south

In May 1539, de Soto landed nine ships with over 620 men and 220 horses in an area generally identified as south Tampa Bay

Tampa Bay is a large natural harbor and shallow estuary connected to the Gulf of Mexico on the west-central coast of Florida, comprising Hillsborough Bay, McKay Bay, Old Tampa Bay, Middle Tampa Bay, and Lower Tampa Bay. The largest freshwater i ...

. Historian Robert S. Weddle has suggested that he landed at either Charlotte Harbor or San Carlos Bay

San Carlos Bay is a bay located southwest of Fort Myers, Florida, at the mouth of the Caloosahatchee River. It connects to Pine Island Sound to the west and to Matlacha Pass to the north. The bay contains Bunche Beach Preserve, a 718-acre conserva ...

. He named the land as ''Espíritu Santo'', after the Holy Spirit

The Holy Spirit, otherwise known as the Holy Ghost, is a concept within the Abrahamic religions. In Judaism, the Holy Spirit is understood as the divine quality or force of God manifesting in the world, particularly in acts of prophecy, creati ...

. The ships carried priests, craftsmen, engineers, farmers, and merchants; some with their families, some from Cuba, most from Europe and Africa. Few of the men had traveled before outside of Spain, or even away from their home villages.

Near de Soto's port, the party found Juan Ortiz, a Spaniard

Spaniards, or Spanish people, are a Romance languages, Romance-speaking Ethnicity, ethnic group native to the Iberian Peninsula, primarily associated with the modern Nation state, nation-state of Spain. Genetics, Genetically and Ethnolinguisti ...

living with the Mocoso people. Ortiz had been captured by the Uzita while searching for the lost Narváez expedition

The Narváez expedition was a Spanish expedition started in 1527 that was intended to explore Florida and establish colonial settlements. The expedition was initially led by Pánfilo de Narváez, who died in 1528. Many more people died as the e ...

; he later escaped to Mocoso

Mocoso (or Mocoço) was the name of a 16th-century chiefdom located on the east side of Tampa Bay, Florida near the mouth of the Alafia River, of its chief town and of its chief. Mocoso was also the name of a 17th-century village in the province o ...

. Ortiz had learned the Timucua language

Timucua is a language isolate formerly spoken in northern and central Florida and southern Georgia by the Timucua peoples. Timucua was the primary language used in the area at the time of Spanish colonization in Florida. Differences among the n ...

and served as an interpreter to de Soto as he traversed the Timucuan-speaking areas on his way to Apalachee

The Apalachee were an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, specifically an Indigenous people of Florida, who lived in the Florida Panhandle until the early 18th century. They lived between the Aucilla River and Ochlockonee River,Bobby ...

.

Ortiz developed a method for guiding the expedition and communicating with the various tribes, who spoke many dialects and languages. He recruited guides from each tribe along the route. A chain of communication was established whereby a guide who had lived in close proximity to another tribal area was able to pass his information and language on to a guide from a neighboring area. Because Ortiz refused to dress as a ''hidalgo'' Spaniard, other officers questioned his motives. De Soto remained loyal to Ortiz, allowing him the freedom to dress and live among his native friends. Another important guide was the seventeen-year-old boy ''Perico'', or Pedro, from what is now Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

. He spoke several of the local tribes' languages and could communicate with Ortiz. Perico was taken as a guide in 1540. The Spanish had also captured other Indians, whom they used as slave

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

labor. Perico was treated better due to his value to the Spaniards.

The expedition traveled north, exploring Florida's West Coast, and encountering native ambushes and conflicts along the way. Hernando de Soto's army seized the food stored in the villages, captured women to be used as slaves for the soldiers' sexual gratification, and forced men and boys to serve as guides and bearers. The army fought two battles with Timucua groups, resulting in heavy Timucua casualties. After defeating the resisting Timucuan

The Timucua were a Native American people who lived in Northeast and North Central Florida and southeast Georgia. They were the largest indigenous group in that area and consisted of about 35 chiefdoms, many leading thousands of people. The var ...

warriors, Hernando de Soto had 200 executed, in what was to be called the Napituca Massacre, the first large-scale massacre by Europeans in the current United States. One of Soto's most important battles with the natives, along his conquest of Florida, was a 1539 battle with Chief Vitachuco. Unlike other native chiefs who entered into peace with the Spanish, Vitachuco did not trust them and had secretly plotted to kill Soto and his army, but he was betrayed by interpreters who told Soto the plan. So, Soto struck first and, in the process, killed thousands of natives. Those that survived were surrounded and cornered by woods and water. Thousands were killed during the 3 hours battle and 900 survivors took refuge in the pond, specifically Two-mile Pond in Melrose, where they continued to fight, while swimming. Most eventually surrendered, but after 30 hours in the water, 7 men remained and had to be dragged out of the water by the Spanish. De Soto's first winter encampment was at ''Anhaica

Anhaica (also known as Iviahica, Yniahico, and pueblo of Apalache) was the principal town of the Apalachee people, located in what is now Tallahassee, Florida. In the early period of Spanish colonization, it was the capital of the Apalachee Pro ...

'', the capital of the Apalachee

The Apalachee were an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, specifically an Indigenous people of Florida, who lived in the Florida Panhandle until the early 18th century. They lived between the Aucilla River and Ochlockonee River,Bobby ...

people. It is one of the few places on the route where archaeologists have found physical traces of the expedition. The chroniclers described this settlement as being near the "Bay of Horses". The bay was named for events of the 1527 Narváez expedition

The Narváez expedition was a Spanish expedition started in 1527 that was intended to explore Florida and establish colonial settlements. The expedition was initially led by Pánfilo de Narváez, who died in 1528. Many more people died as the e ...

, the members of which, dying of starvation, killed and ate their horses while building boats for escape by the Gulf of Mexico.

1540: The Southeast

From their winter location in the western panhandle of Florida, having heard of gold being mined "toward the sun's rising", the expedition turned northeast through what is now the modern state ofGeorgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

. Based on archaeological finds made in 2009 at a remote, privately owned site near the Ocmulgee River

The Ocmulgee River () is a western tributary of the Altamaha River, approximately 255 mi (410 km) long, in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the westernmost major tributary of the Altamaha.Telfair County

Telfair County is a county located in the southern portion of the U.S. state of Georgia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 12,477. The largest city and county seat is McRae-Helena.

In 2009, researchers from the Fernbank Museum of N ...

. Artifacts found here include nine glass trade beads

Trade beads are beads that were used as a medium of barter within and amongst communities. They are considered to be one of the earliest forms of trade between members of the human race. It has also been surmised that bead trading was one of t ...

, some of which bear a chevron pattern made in Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

for a limited period of time and believed to be indicative of the de Soto expedition. Six metal objects were also found, including a silver pendant and some iron tools. The rarest items were found within what researchers believe was a large council house of the indigenous people whom de Soto was visiting.

The expedition continued to present-day South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

. There the expedition recorded being received by a female chief (''The Lady of Cofitachequi

The Lady of Cofitachequi was a Native American woman who served as chieftainess of the Cofitachequi tribe during the 16th century. She was described by Spanish chroniclers as possessing beautiful physical attributes as well as excellent mental capa ...

''), who gave her tribe's pearls, food and other goods to the Spanish soldiers. The expedition found no gold, however, other than pieces from an earlier coastal expedition (presumably that of Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón

Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón ( – 18 October 1526) was a Spanish magistrate and explorer who in 1526 established the short-lived San Miguel de Gualdape colony, one of the first European attempts at a settlement in what is now the United States. Ayl ...

.)

De Soto headed north into the

De Soto headed north into the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, are a mountain range in eastern to northeastern North America. The term "Appalachian" refers to several different regions associated with the mountain range, and its surrounding terrain ...

of present-day western North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

, where he spent a month resting the horses while his men searched for gold. De Soto next entered eastern Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

. At this point, de Soto either continued along the Tennessee River

The Tennessee River is a long river located in the Southern United States, southeastern United States in the Tennessee Valley. Flowing through the states of Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky, it begins at the confluence of Fren ...

to enter Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

from the north (according to John R. Swanton

John Reed Swanton (February 19, 1873 – May 2, 1958) was an American anthropologist, folklorist, and linguist who worked with Native American peoples throughout the United States. Swanton achieved recognition in the fields of ethnology and ethn ...

), or turned south and entered northern Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

(according to Charles M. Hudson

Charles Melvin Hudson Jr. (1932–2013) was an anthropologist, a professor of anthropology and history at the University of Georgia. He was a leading scholar on the history and culture of Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the pr ...

). Swanton's final report, published by the Smithsonian, remains an important resource but Hudson's reconstruction of the route was conducted 40 years later and benefited from considerable advances in archaeological methods.

De Soto's expedition spent another month in the Coosa chiefdom

The Coosa Chiefdom was a powerful Native American paramount chiefdom in what are now Gordon and Murray counties in Georgia, in the United States.Tuskaloosa

Tuskaloosa (less commonly spelled as ''Tuskalusa'', ''Tastaluca'', ''Tuskaluza'') (birthdate unknown, - 1540) was a paramount chief of a Mississippian chiefdom in what is now the U.S. state of Alabama. His people were ancestors to the several s ...

, who was the paramount chief

A paramount chief is the English-language designation for a king or queen or the highest-level political leader in a regional or local polity or country administered politically with a Chiefdom, chief-based system. This term is used occasionally ...

, believed to have been connected to the large and complex Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a collection of Native American societies that flourished in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from approximately 800 to 1600 CE, varying regionally. It was known for building la ...

, which extended throughout the Mississippi Valley and its tributaries. De Soto turned south toward the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

to meet two ships bearing fresh supplies from Havana

Havana (; ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.Mabila

Mabila (also spelled Mavila, Mavilla, Maubila, or Mauvilla, as influenced by Spanish or French transliterations) was a small fortress town known to the paramount chief Tuskaloosa in 1540, in a region of present-day central Alabama. The exact loca ...

'' (or ''Mauvila''), a fortified city in southern Alabama,"The Old Mobile Project Newsletter" (PDF). ''University of South Alabama Center for Archaeological Studies''. to receive the women. De Soto gave the chief a pair of boots and a red cloak to reward him for his cooperation. The Mobilian tribe, under chief Tuskaloosa, ambushed de Soto's army. Other sources suggest de Soto's men were attacked after attempting to force their way into a cabin occupied by Tuskaloosa. The Spaniards fought their way out, and retaliated by burning the town to the ground. During the nine-hour encounter, about 200 Spaniards died, and 150 more were badly wounded, according to the chronicler Elvas. Twenty more died during the next few weeks. They killed an estimated 2,000–6,000 Native Americans at Mabila, making the battle one of the bloodiest in recorded North American history.

The Spaniards won a Pyrrhic victory

A Pyrrhic victory ( ) is a victory that inflicts such a devastating toll on the victor that it is tantamount to defeat. Such a victory negates any true sense of achievement or damages long-term progress.

The phrase originates from a quote from ...

, as they had lost most of their possessions and nearly one-quarter of their horses. The Spaniards were wounded and sickened, surrounded by enemies and without equipment in an unknown territory. Fearing that word of this would reach Spain if his men reached the ships at Mobile Bay

Mobile Bay ( ) is a shallow inlet of the Gulf of Mexico, lying within the state of Alabama in the United States. Its mouth is formed by the Fort Morgan Peninsula on the eastern side and Dauphin Island, a barrier island on the western side. T ...

, de Soto led them away from the Gulf Coast. He moved into inland Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

, most likely near present-day Tupelo

Tupelo commonly refers to:

* Tupelo (tree), a small genus of deciduous trees with alternate, simple leaves

* Tupelo, Mississippi, the county seat and the largest city of Lee County, Mississippi

Tupelo may also refer to:

Places

* Tupelo, Arka ...

, where they spent the winter.

1541: Westward

In the spring of 1541, de Soto demanded 200 men as porters from the

In the spring of 1541, de Soto demanded 200 men as porters from the Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, United States. Their traditional territory was in northern Mississippi, northwestern and northern Alabama, western Tennessee and southwestern Kentucky. Their language is ...

. They refused his demand and attacked the Spanish camp during the night.

On 8 May 1541, de Soto's troops reached the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

.

De Soto had little interest in the river, which in his view was an obstacle to his mission. There has been considerable research into the exact location where de Soto crossed the Mississippi River. A commission appointed by Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

in 1935 determined that Sunflower Landing, Mississippi, was the "most likely" crossing place. De Soto possibly traveled down Charley's Trace

Charley's Trace is a former Native American trail to the Mississippi River.

Charley's Trace (also spelled Charlie's Trace) is possibly named for a Choctaw trader who operated a steamboat fueling station near Clarksdale in the 1820s. There is s ...

, which had been used as a trail through the swamps of the Mississippi Delta

The Mississippi Delta, also known as the Yazoo–Mississippi Delta, or simply the Delta, is the distinctive northwest section of the U.S. state of Mississippi (and portions of Arkansas and Louisiana) that lies between the Mississippi and Yazo ...

, to reach the Mississippi River. De Soto and his men spent a month building flatboats, and crossed the river at night to avoid the Native Americans who were patrolling the river. De Soto had hostile relations with the native people in this area.

In the late 20th century, research suggests other locations may have been the site of de Soto's crossing, including three locations in Mississippi: Commerce

Commerce is the organized Complex system, system of activities, functions, procedures and institutions that directly or indirectly contribute to the smooth, unhindered large-scale exchange (distribution through Financial transaction, transactiona ...

, Friars Point

Friars Point is a town in Coahoma County, Mississippi, Coahoma County, Mississippi, United States. Per the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 896. Situated on the Mississippi River, Friars Point was once a busy port town, ...

, and Walls

Walls may refer to:

*The plural of wall, a structure

* Walls (surname), a list of notable people with the surname

Places

* Walls, Louisiana, United States

* Walls, Mississippi, United States

*Walls, Ontario

Perry is a township (Canada), ...

, as well as Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in Shelby County, Tennessee, United States, and its county seat. Situated along the Mississippi River, it had a population of 633,104 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of municipalities in Tenne ...

. Once across the river, the expedition continued traveling westward through modern-day Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. They wintered in ''Autiamique'', on the Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. It generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's source basin lies in Colorado, specifically ...

.

After a harsh winter, the Spanish expedition decamped and moved on more erratically. Their interpreter Juan Ortiz had died, making it more difficult for them to get directions and food sources, and generally to communicate with the Natives. The expedition went as far inland as the Caddo River

The Caddo River is a tributary of the Ouachita River in the U.S. state of Arkansas. The river is about long.Calculated in Google Maps and Google Earth

Course

The Caddo River flows out of the Ouachita Mountains through Montgomery, Pike, and C ...

, where they clashed with a Native American tribe called the Tula in October 1541. The Spaniards characterized them as the most skilled and dangerous warriors they had encountered.Carter, Cecile Elkins''Caddo Indians: Where We Come From''.

Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001: 21. This may have happened in the area of present-day

Caddo Gap, Arkansas

Caddo Gap is an unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP) in Montgomery County, Arkansas, United States. It lies between Glenwood and Norman, on the Caddo River. It was first listed as a CDP in the 2020 census with a populati ...

(a monument to the de Soto expedition was erected in that community). Eventually, the Spaniards returned to the Mississippi River.

Death

De Soto died of a fever on 21 May 1542, in the native village of ''

De Soto died of a fever on 21 May 1542, in the native village of ''Guachoya

Quigualtam or Quilgualtanqui was a powerful Native Americans in the United States, Native American Plaquemine culture polity encountered in 1542–1543 by the Hernando de Soto (explorer), Hernando de Soto expedition. The capital of the polity and i ...

.'' Historical sources disagree as to whether de Soto died near present-day Lake Village, Arkansas

Lake Village is a city in and the county seat of Chicot County, Arkansas, Chicot County, Arkansas, United States. The population was 2,575 at the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census. It is located in the Arkansas Delta. Lake Village is name ...

McArthur, Arkansas

McArthur is an unincorporated community in Clayton Township, Desha County, Arkansas. It is located on Arkansas Highway 1 northeast of McGehee.

McArthur is one of two possible sites of the death of Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1 ...

, or Ferriday, Louisiana

Ferriday is a town in Concordia Parish, Louisiana, Concordia Parish, which borders the Mississippi River and is located on the central eastern border of Louisiana, United States. With a population of 3,511 at the 2010 United States Census, 2010 ...

.Charles Hudson Charles Hudson may refer to:

* Sir Charles Hudson, 1st Baronet (1730–1813), English baronet

* Charles Hudson (American politician) (1795–1881), American historian and politician, Congressman in U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts

* ...

(1997)pp. 349–352 "Death of de Soto"

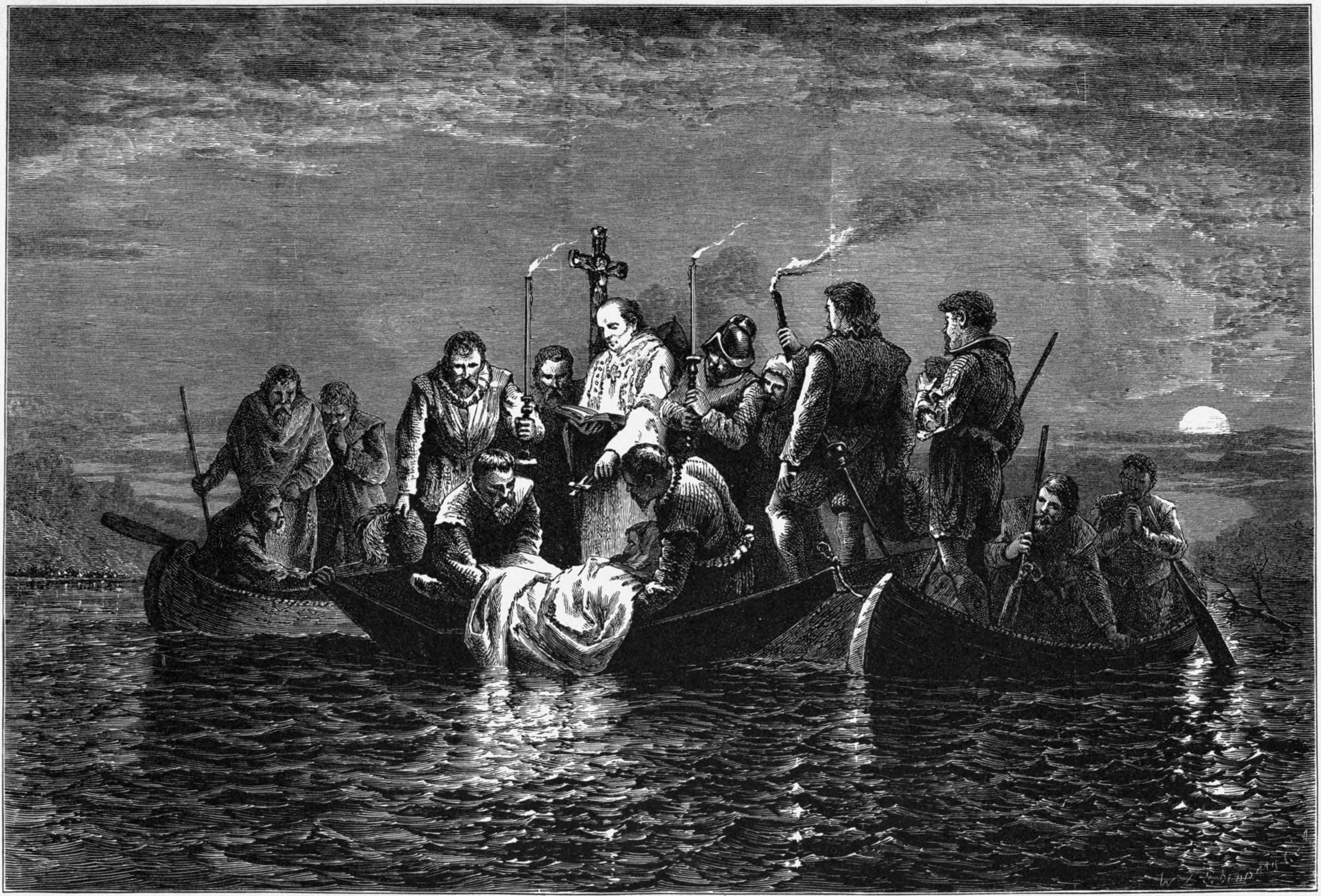

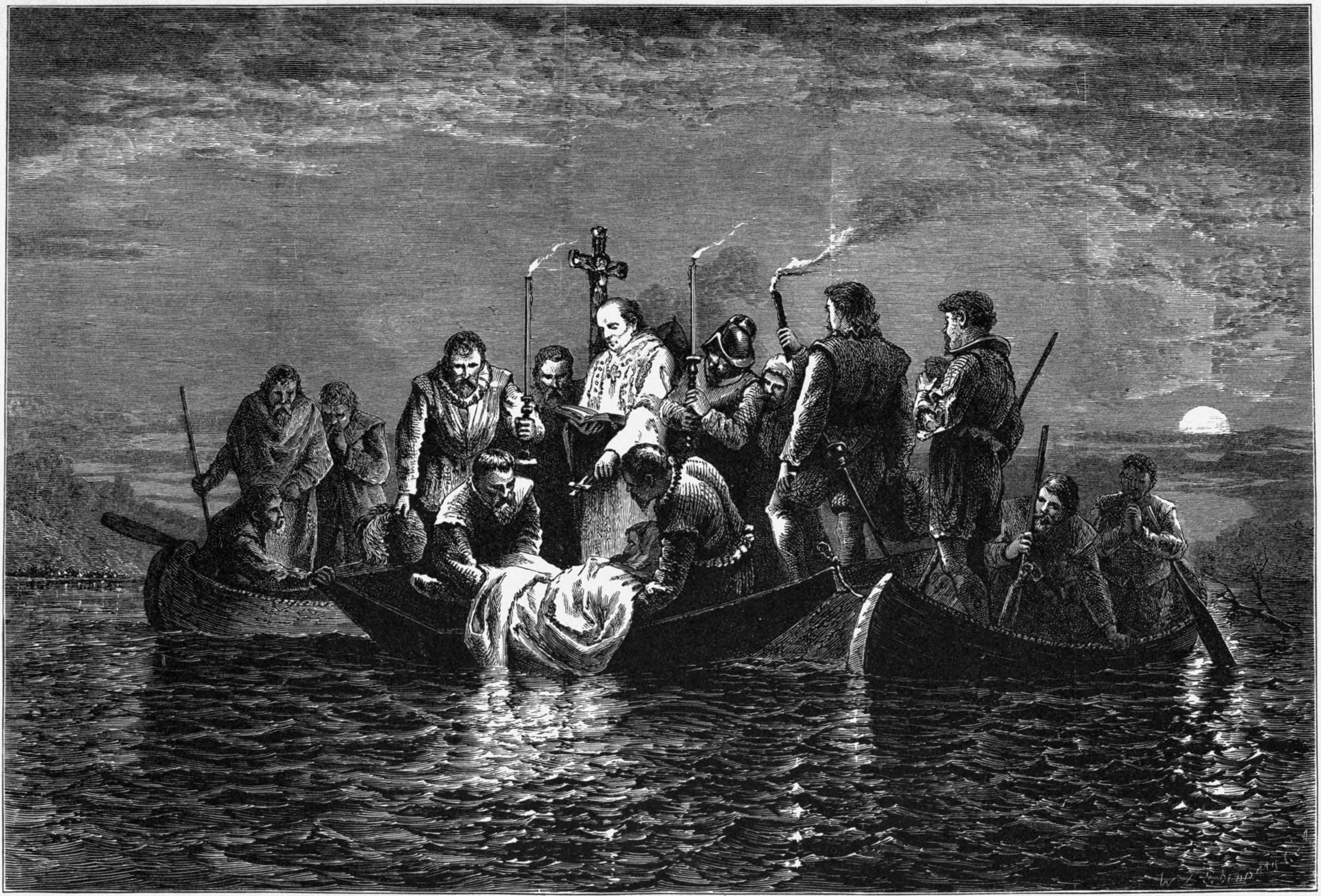

Louisiana erected a historical marker at the conjectured site on the western bank of the Mississippi River. Before his death, de Soto chose Luis de Moscoso Alvarado, his former maestro de campo (or field commander), to assume command of the expedition. At the time of death, de Soto owned four Indian slaves, three horses, and 700 hogs. De Soto had deceived the local natives into believing that he was a deity, specifically an "immortal Son of the Sun", to gain their submission without conflict. Some of the natives had already become skeptical of de Soto's deity claims, so his men were anxious to conceal his death. The actual site of his burial is not known. According to one source, de Soto's men hid his corpse in blankets weighted with sand and sank it in the middle of the Mississippi River during the night.

Return of the expedition to Mexico City

De Soto's expedition had explored ''La Florida'' for three years without finding the expected treasures or a hospitable site for colonization. They had lost nearly half their men, and most of the horses. By this time, the soldiers were wearing animal skins for clothing. Many were injured and in poor health. The leaders came to a consensus (although not total) to end the expedition and try to find a way home, either down the Mississippi River, or overland acrossTexas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

to the Spanish colony of Mexico City

Mexico City is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Mexico, largest city of Mexico, as well as the List of North American cities by population, most populous city in North America. It is one of the most important cultural and finan ...

.

They decided that building boats would be too difficult and time-consuming and that navigating the Gulf of Mexico was too risky, so they headed overland to the southwest. Eventually, they reached a region in present-day Texas that was dry. The native populations were made up mostly of subsistence hunter-gatherers. The soldiers found no villages to raid for food, and the army was still too large to live off the land. They were forced to backtrack to the more developed agricultural regions along the Mississippi, where they began building seven ''bergantines'', or pinnaces

Pinnace may refer to:

* Pinnace (ship's boat), a small vessel used as a tender to larger vessels among other things

* Full-rigged pinnace

The full-rigged pinnace was the larger of two types of vessel called a pinnace in use from the sixteenth ...

. They melted down all the iron, including horse tackle and slave shackles, to make nails for the boats. They survived through the winter, and the spring floods delayed them another two months. By July they set off on their makeshift boats down the Mississippi for the coast.

Taking about two weeks to make the journey, the expedition encountered hostile fleets of war canoes along the whole course. The first was led by the powerful paramount chief ''Quigualtam

Quigualtam or Quilgualtanqui was a powerful Native Americans in the United States, Native American Plaquemine culture polity encountered in 1542–1543 by the Hernando de Soto (explorer), Hernando de Soto expedition. The capital of the polity and i ...

'', whose fleet followed the boats, shooting arrows at the soldiers for days as they drifted through their territory. The Spanish had no effective offensive weapons on the water, as their crossbow

A crossbow is a ranged weapon using an Elasticity (physics), elastic launching device consisting of a Bow and arrow, bow-like assembly called a ''prod'', mounted horizontally on a main frame called a ''tiller'', which is hand-held in a similar f ...

s had long since ceased working. They relied on armor and sleeping mats to block the arrows. About 11 Spaniards were killed along this stretch and many more wounded.

On reaching the mouth of the Mississippi, they stayed close to the Gulf shore heading south and west. After about 50 days, they made it to the Pánuco River

The Pánuco River (, ), also known as the ''Río de Canoas'', is a river in Mexico fed by several tributaries including the Moctezuma River and emptying into the Gulf of Mexico. The river is approximately long and passes through or borders the ...

and the Spanish frontier town of Pánuco. There they rested for about a month. During this time many of the Spaniards, having safely returned and reflecting on their accomplishments, decided they had left ''La Florida'' too soon. There were some fights within the company, leading to some deaths. But, after they reached Mexico City and the Viceroy Don Antonio de Mendoza offered to lead another expedition to ''La Florida'', few of the survivors volunteered. Of the recorded 700 participants at the start, between 300 and 350 survived (311 is a commonly accepted figure). Most of the men stayed in the New World, settling in Mexico, Peru, Cuba, and other Spanish colonies.

Effects of expedition in North America

The Spanish believed that de Soto's excursion to Florida was a failure. They acquired neither gold nor prosperity and founded no colonies. But the expedition had several major consequences. It contributed to the process of theColumbian Exchange

The Columbian exchange, also known as the Columbian interchange, was the widespread transfer of plants, animals, and diseases between the New World (the Americas) in the Western Hemisphere, and the Old World (Afro-Eurasia) in the Eastern Hemis ...

. For instance, some of the swine

Suina (also known as Suiformes) is a suborder of omnivorous, non-ruminant artiodactyl mammals that includes the domestic pig and peccaries. A member of this clade is known as a suine. Suina includes the family Suidae, termed suids, known in ...

brought by de Soto escaped and became the ancestors of feral razorback