Custer's Last Stand on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other

Col.

Col.

By the time of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, half of the 7th Cavalry's companies had just returned from 18 months of constabulary duty in the

By the time of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, half of the 7th Cavalry's companies had just returned from 18 months of constabulary duty in the

As the Army moved into the field on its expedition, it was operating with incorrect assumptions as to the number of Indians it would encounter. These assumptions were based on inaccurate information provided by the Indian Agents that no more than 800 "hostiles" were in the area. The Indian Agents based this estimate on the number of Lakota that Sitting Bull and other leaders had reportedly led off the reservation in protest of U.S. government policies. It was in fact a correct estimate until several weeks before the battle when the "reservation Indians" joined Sitting Bull's ranks for the summer buffalo hunt. The agents did not consider the many thousands of these "reservation Indians" who had unofficially left the reservation to join their "unco-operative non-reservation cousins led by Sitting Bull". Thus, Custer unknowingly faced thousands of Indians, including the 800 non-reservation "hostiles". All Army plans were based on the incorrect numbers. Although Custer was criticized after the battle for not having accepted reinforcements and for dividing his forces, it appears that he had accepted the same official government estimates of hostiles in the area which Terry and Gibbon had also accepted. Historian James Donovan notes, however, that when Custer later asked interpreter Fred Gerard for his opinion on the size of the opposition, he estimated the force at 1,100 warriors.

Additionally, Custer was more concerned with preventing the escape of the Lakota and Cheyenne than with fighting them. From his observation, as reported by John Martin ( Giovanni Martino),Charles Windolph, Frazier Hunt, Robert Hunt, Neil Mangum, ''I Fought with Custer: The Story of Sergeant Windolph, Last Survivor of the Battle of the Little Big Horn: with Explanatory Material and Contemporary Sidelights on the Custer Fight'', University of Nebraska Press, 1987, p. 86. Custer assumed the warriors had been sleeping in on the morning of the battle, to which virtually every native account attested later, giving Custer a false estimate of what he was up against. When he and his scouts first looked down on the village from the Crow's Nest across the Little Bighorn River, they could see only the herd of ponies. Later, looking from a hill away after parting with Reno's command, Custer could observe only women preparing for the day, and young boys taking thousands of horses out to graze south of the village. Custer's Crow scouts told him it was the largest native village they had ever seen. When the scouts began changing back into their native dress right before the battle, Custer released them from his command. While the village was enormous, Custer still thought there were far fewer warriors to defend the village.

Finally, Custer may have assumed when he encountered the Native Americans that his subordinate Benteen, who was with the pack train, would provide support. Rifle volleys were a standard way of telling supporting units to come to another unit's aid. In a subsequent official 1879 Army investigation requested by Major Reno, the Reno Board of Inquiry (RCOI), Benteen and Reno's men testified that they heard distinct rifle volleys as late as 4:30 pm during the battle.

Custer had initially wanted to take a day to scout the village before attacking; however, when men who went back looking for supplies accidentally dropped by the pack train, they discovered that their track had already been discovered by Indians. Reports from his scouts also revealed fresh pony tracks from ridges overlooking his formation. It became apparent that the warriors in the village were either aware or would soon be aware of his approach. Fearing that the village would break up into small bands that he would have to chase, Custer began to prepare for an immediate attack.Donovan, loc 3699

As the Army moved into the field on its expedition, it was operating with incorrect assumptions as to the number of Indians it would encounter. These assumptions were based on inaccurate information provided by the Indian Agents that no more than 800 "hostiles" were in the area. The Indian Agents based this estimate on the number of Lakota that Sitting Bull and other leaders had reportedly led off the reservation in protest of U.S. government policies. It was in fact a correct estimate until several weeks before the battle when the "reservation Indians" joined Sitting Bull's ranks for the summer buffalo hunt. The agents did not consider the many thousands of these "reservation Indians" who had unofficially left the reservation to join their "unco-operative non-reservation cousins led by Sitting Bull". Thus, Custer unknowingly faced thousands of Indians, including the 800 non-reservation "hostiles". All Army plans were based on the incorrect numbers. Although Custer was criticized after the battle for not having accepted reinforcements and for dividing his forces, it appears that he had accepted the same official government estimates of hostiles in the area which Terry and Gibbon had also accepted. Historian James Donovan notes, however, that when Custer later asked interpreter Fred Gerard for his opinion on the size of the opposition, he estimated the force at 1,100 warriors.

Additionally, Custer was more concerned with preventing the escape of the Lakota and Cheyenne than with fighting them. From his observation, as reported by John Martin ( Giovanni Martino),Charles Windolph, Frazier Hunt, Robert Hunt, Neil Mangum, ''I Fought with Custer: The Story of Sergeant Windolph, Last Survivor of the Battle of the Little Big Horn: with Explanatory Material and Contemporary Sidelights on the Custer Fight'', University of Nebraska Press, 1987, p. 86. Custer assumed the warriors had been sleeping in on the morning of the battle, to which virtually every native account attested later, giving Custer a false estimate of what he was up against. When he and his scouts first looked down on the village from the Crow's Nest across the Little Bighorn River, they could see only the herd of ponies. Later, looking from a hill away after parting with Reno's command, Custer could observe only women preparing for the day, and young boys taking thousands of horses out to graze south of the village. Custer's Crow scouts told him it was the largest native village they had ever seen. When the scouts began changing back into their native dress right before the battle, Custer released them from his command. While the village was enormous, Custer still thought there were far fewer warriors to defend the village.

Finally, Custer may have assumed when he encountered the Native Americans that his subordinate Benteen, who was with the pack train, would provide support. Rifle volleys were a standard way of telling supporting units to come to another unit's aid. In a subsequent official 1879 Army investigation requested by Major Reno, the Reno Board of Inquiry (RCOI), Benteen and Reno's men testified that they heard distinct rifle volleys as late as 4:30 pm during the battle.

Custer had initially wanted to take a day to scout the village before attacking; however, when men who went back looking for supplies accidentally dropped by the pack train, they discovered that their track had already been discovered by Indians. Reports from his scouts also revealed fresh pony tracks from ridges overlooking his formation. It became apparent that the warriors in the village were either aware or would soon be aware of his approach. Fearing that the village would break up into small bands that he would have to chase, Custer began to prepare for an immediate attack.Donovan, loc 3699

The first group to attack was Major Reno's second detachment (Companies A, G and M) after receiving orders from Custer written out by Lt. William W. Cooke, as Custer's Crow scouts reported Sioux tribe members were alerting the village. Ordered to charge, Reno began that phase of the battle. The orders, made without accurate knowledge of the village's size, location, or the warriors' propensity to stand and fight, had been to pursue the Native Americans and "bring them to battle." Reno's force crossed the Little Bighorn at the mouth of what is today Reno Creek around 3:00 pm on June 25. They immediately realized that the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne were present "in force and not running away."

Reno advanced rapidly across the open field towards the northwest, his movements masked by the thick belt of trees that ran along the southern banks of the Little Bighorn River. The same trees on his front right shielded his movements across the wide field over which his men rapidly rode, first with two approximately forty-man companies abreast and eventually with all three charging abreast. The trees also obscured Reno's view of the Native American village until his force had passed that bend on his right front and was suddenly within arrow-shot of the village. The tepees in that area were occupied by the Hunkpapa Sioux. Neither Custer nor Reno had much idea of the length, depth and size of the encampment they were attacking, as the village was hidden by the trees. When Reno came into the open in front of the south end of the village, he sent his Arikara/Ree and Crow Indian scouts forward on his exposed left flank. Realizing the full extent of the village's width, Reno quickly suspected what he would later call "a trap" and stopped a few hundred yards short of the encampment.

He ordered his troopers to dismount and deploy in a

The first group to attack was Major Reno's second detachment (Companies A, G and M) after receiving orders from Custer written out by Lt. William W. Cooke, as Custer's Crow scouts reported Sioux tribe members were alerting the village. Ordered to charge, Reno began that phase of the battle. The orders, made without accurate knowledge of the village's size, location, or the warriors' propensity to stand and fight, had been to pursue the Native Americans and "bring them to battle." Reno's force crossed the Little Bighorn at the mouth of what is today Reno Creek around 3:00 pm on June 25. They immediately realized that the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne were present "in force and not running away."

Reno advanced rapidly across the open field towards the northwest, his movements masked by the thick belt of trees that ran along the southern banks of the Little Bighorn River. The same trees on his front right shielded his movements across the wide field over which his men rapidly rode, first with two approximately forty-man companies abreast and eventually with all three charging abreast. The trees also obscured Reno's view of the Native American village until his force had passed that bend on his right front and was suddenly within arrow-shot of the village. The tepees in that area were occupied by the Hunkpapa Sioux. Neither Custer nor Reno had much idea of the length, depth and size of the encampment they were attacking, as the village was hidden by the trees. When Reno came into the open in front of the south end of the village, he sent his Arikara/Ree and Crow Indian scouts forward on his exposed left flank. Realizing the full extent of the village's width, Reno quickly suspected what he would later call "a trap" and stopped a few hundred yards short of the encampment.

He ordered his troopers to dismount and deploy in a

Despite hearing heavy gunfire from the north, including distinct volleys at 4:20 pm, Benteen concentrated on reinforcing Reno's badly wounded and hard-pressed detachment rather than continuing on toward Custer's position. Benteen's apparent reluctance to reach Custer prompted later criticism that he had failed to follow orders. Around 5:00 pm, Capt. Thomas Weir and Company D moved out to contact Custer. They advanced a mile, to what is today Weir Ridge or Weir Point. Weir could see that the Indian camps comprised some 1,800 lodges. Behind them he saw through the dust and smoke hills that were oddly red in color; he later learned that this was a massive assemblage of Indian ponies. By this time, roughly 5:25 pm, Custer's battle may have concluded. From a distance, Weir witnessed many Indians on horseback and on foot shooting at items on the ground-perhaps killing wounded soldiers and firing at dead bodies on the "Last Stand Hill" at the northern end of the Custer battlefield. Some historians have suggested that what Weir witnessed was a fight on what is now called Calhoun Hill, some minutes earlier. The destruction of Keogh's battalion may have begun with the collapse of L, I and C Company (half of it) following the combined assaults led by

Despite hearing heavy gunfire from the north, including distinct volleys at 4:20 pm, Benteen concentrated on reinforcing Reno's badly wounded and hard-pressed detachment rather than continuing on toward Custer's position. Benteen's apparent reluctance to reach Custer prompted later criticism that he had failed to follow orders. Around 5:00 pm, Capt. Thomas Weir and Company D moved out to contact Custer. They advanced a mile, to what is today Weir Ridge or Weir Point. Weir could see that the Indian camps comprised some 1,800 lodges. Behind them he saw through the dust and smoke hills that were oddly red in color; he later learned that this was a massive assemblage of Indian ponies. By this time, roughly 5:25 pm, Custer's battle may have concluded. From a distance, Weir witnessed many Indians on horseback and on foot shooting at items on the ground-perhaps killing wounded soldiers and firing at dead bodies on the "Last Stand Hill" at the northern end of the Custer battlefield. Some historians have suggested that what Weir witnessed was a fight on what is now called Calhoun Hill, some minutes earlier. The destruction of Keogh's battalion may have begun with the collapse of L, I and C Company (half of it) following the combined assaults led by

''Custer's Last Battle''

. The Century Magazine, Vol. XLIII, No. 3, January. New York: The Century Company. Chief Gall's statements were corroborated by other Indians, notably the wife of Spotted Horn Bull. Given that no bodies of men or horses were found anywhere near the ford, Godfrey himself concluded "that Custer did not go to the ford with any body of men". Cheyenne oral tradition credits Buffalo Calf Road Woman with striking the blow that knocked Custer off his horse before he died.Martin J. Kidston, "Northern Cheyenne break vow of silence"

, ''Helena Independent Record'', June 28, 2005. RetrievedOctober 23, 2009.

Having isolated Reno's force and driven them away from their encampment, the bulk of the native warriors were free to pursue Custer. The route taken by Custer to his "Last Stand" remains a subject of debate. One possibility is that after ordering Reno to charge, Custer continued down Reno Creek to within about a half-mile (800 m) of the Little Bighorn, but then turned north and climbed up the bluffs, reaching the same spot to which Reno would soon retreat. From this point on the other side of the river, he could see Reno charging the village. Riding north along the bluffs, Custer could have descended into Medicine Tail Coulee. Some historians believe that part of Custer's force descended the coulee, going west to the river and attempting unsuccessfully to cross into the village. According to some accounts, a small contingent of Indian sharpshooters effectively opposed this crossing.

White Cow Bull claimed to have shot a leader wearing a buckskin jacket off his horse in the river. While no other Indian account supports this claim, if White Bull did shoot a buckskin-clad leader off his horse, some historians have argued that Custer may have been seriously wounded by him. Some Indian accounts claim that besides wounding one of the leaders of this advance, a soldier carrying a company guidon was also hit. Troopers had to dismount to help the wounded men back onto their horses. The fact that either of the non-mutilation wounds to Custer's body (a bullet wound below the heart and a shot to the left temple) would have been instantly fatal casts doubt on his being wounded and remounted.

Reports of an attempted fording of the river at Medicine Tail Coulee might explain Custer's purpose for Reno's attack, that is, a coordinated "hammer-and-anvil" maneuver, with Reno's holding the Indians at bay at the southern end of the camp, while Custer drove them against Reno's line from the north. Other historians have noted that if Custer did attempt to cross the river near Medicine Tail Coulee, he may have believed it was the north end of the Indian camp, only to discover that it was the middle. Some Indian accounts, however, place the Northern Cheyenne encampment and the north end of the overall village to the left (and south) of the opposite side of the crossing. The precise location of the north end of the village remains in dispute, however.

Having isolated Reno's force and driven them away from their encampment, the bulk of the native warriors were free to pursue Custer. The route taken by Custer to his "Last Stand" remains a subject of debate. One possibility is that after ordering Reno to charge, Custer continued down Reno Creek to within about a half-mile (800 m) of the Little Bighorn, but then turned north and climbed up the bluffs, reaching the same spot to which Reno would soon retreat. From this point on the other side of the river, he could see Reno charging the village. Riding north along the bluffs, Custer could have descended into Medicine Tail Coulee. Some historians believe that part of Custer's force descended the coulee, going west to the river and attempting unsuccessfully to cross into the village. According to some accounts, a small contingent of Indian sharpshooters effectively opposed this crossing.

White Cow Bull claimed to have shot a leader wearing a buckskin jacket off his horse in the river. While no other Indian account supports this claim, if White Bull did shoot a buckskin-clad leader off his horse, some historians have argued that Custer may have been seriously wounded by him. Some Indian accounts claim that besides wounding one of the leaders of this advance, a soldier carrying a company guidon was also hit. Troopers had to dismount to help the wounded men back onto their horses. The fact that either of the non-mutilation wounds to Custer's body (a bullet wound below the heart and a shot to the left temple) would have been instantly fatal casts doubt on his being wounded and remounted.

Reports of an attempted fording of the river at Medicine Tail Coulee might explain Custer's purpose for Reno's attack, that is, a coordinated "hammer-and-anvil" maneuver, with Reno's holding the Indians at bay at the southern end of the camp, while Custer drove them against Reno's line from the north. Other historians have noted that if Custer did attempt to cross the river near Medicine Tail Coulee, he may have believed it was the north end of the Indian camp, only to discover that it was the middle. Some Indian accounts, however, place the Northern Cheyenne encampment and the north end of the overall village to the left (and south) of the opposite side of the crossing. The precise location of the north end of the village remains in dispute, however.

In 1908,

In 1908,

File:Edgar Samuel Paxson - Custer's Last Stand.jpg, Custer's Last Stand by Edgar Samuel Paxson

File:Keogh Memorial - Little Big Horn Battlefield.jpg, Keogh Battlefield Marker 1879

After the Custer force was soundly defeated, the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne regrouped to attack Reno and Benteen. The fight continued until dark (approximately 9:00 pm) and for much of the next day, with the outcome in doubt. Reno credited Benteen's luck with repulsing a severe attack on the portion of the perimeter held by Companies H and M.Reno Court of Inquiry. On June 27, the column under General Terry approached from the north, and the natives drew off in the opposite direction. The Crow scout White Man Runs Him was the first to tell General Terry's officers that Custer's force had "been wiped out." Reno and Benteen's wounded troops were given what treatment was available at that time; five later died of their wounds. One of the regiment's three surgeons had been with Custer's column, while another, Dr. DeWolf, had been killed during Reno's retreat. The only remaining doctor was Assistant Surgeon Henry R. Porter.

After the Custer force was soundly defeated, the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne regrouped to attack Reno and Benteen. The fight continued until dark (approximately 9:00 pm) and for much of the next day, with the outcome in doubt. Reno credited Benteen's luck with repulsing a severe attack on the portion of the perimeter held by Companies H and M.Reno Court of Inquiry. On June 27, the column under General Terry approached from the north, and the natives drew off in the opposite direction. The Crow scout White Man Runs Him was the first to tell General Terry's officers that Custer's force had "been wiped out." Reno and Benteen's wounded troops were given what treatment was available at that time; five later died of their wounds. One of the regiment's three surgeons had been with Custer's column, while another, Dr. DeWolf, had been killed during Reno's retreat. The only remaining doctor was Assistant Surgeon Henry R. Porter.

The first to hear the news of the Custer defeat were those aboard the steamboat ''

The first to hear the news of the Custer defeat were those aboard the steamboat ''

Plains Indians

Plains Indians or Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies are the Native American tribes and First Nation band governments who have historically lived on the Interior Plains (the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies) o ...

as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne

The Northern Cheyenne Tribe of the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation ( chy, Tsėhéstáno; formerly named the Tongue River) is the federally recognized Northern Cheyenne tribe. Located in southeastern Montana, the reservation is approximately ...

, and Arapaho

The Arapaho (; french: Arapahos, ) are a Native American people historically living on the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota and Dakota.

By the 1850s, Arapaho ...

tribes and the 7th Cavalry Regiment

The 7th Cavalry Regiment is a United States Army cavalry regiment formed in 1866. Its official nickname is "Garryowen", after the Ireland, Irish air "Garryowen (air), Garryowen" that was adopted as its march tune.

The regiment participated i ...

of the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

. The battle, which resulted in the defeat of U.S. forces, was the most significant action of the Great Sioux War of 1876

The Great Sioux War of 1876, also known as the Black Hills War, was a series of battles and negotiations that occurred in 1876 and 1877 in an alliance of Lakota Sioux and Northern Cheyenne against the United States. The cause of the war was the ...

. It took place on June 25–26, 1876, along the Little Bighorn River in the Crow Indian Reservation

The Crow Indian Reservation is the homeland of the Crow Tribe. Established 1868, the reservation is located in parts of Big Horn, Yellowstone, and Treasure counties in southern Montana in the United States. The Crow Tribe has an enrolled mem ...

in southeastern Montana Territory

The Territory of Montana was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 26, 1864, until November 8, 1889, when it was admitted as the 41st state in the Union as the state of Montana.

Original boundaries

...

.

Most battles in the Great Sioux War, including the Battle of the Little Bighorn (14 on the map to the right), "were on lands those Indians had taken from other tribes since 1851". The Lakotas were there without consent from the local Crow tribe, which had treaty on the area. Already in 1873, Crow chief Blackfoot had called for U.S. military actions against the Indian intruders. The steady Lakota invasion (a reaction to encroachment in the Black Hills) into treaty areas belonging to the smaller tribes ensured the United States a firm Indian alliance with the Arikaras

Arikara (), also known as Sahnish,

''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011)

and the ''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011)

Crows

The Common Remotely Operated Weapon Station (CROWS) is a series of remote weapon stations used by the US military on its armored vehicles and ships. It allows weapon operators to engage targets without leaving the protection of their vehicle. T ...

during the Lakota Wars.

The fight was an overwhelming victory for the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho, who were led by several major war leaders, including Crazy Horse

Crazy Horse ( lkt, Tȟašúŋke Witkó, italic=no, , ; 1840 – September 5, 1877) was a Lakota war leader of the Oglala band in the 19th century. He took up arms against the United States federal government to fight against encroachment by ...

and Chief Gall, and had been inspired by the visions of Sitting Bull

Sitting Bull ( lkt, Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake ; December 15, 1890) was a Hunkpapa Lakota leader who led his people during years of resistance against United States government policies. He was killed by Indian agency police on the Standing Roc ...

(''Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake''). The U.S. 7th Cavalry, a force of 700 men, suffered a major defeat while commanded by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Custer graduated from West Point in 1861 at the bottom of his clas ...

(formerly a brevetted major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

). Five of the 7th Cavalry's twelve companies were wiped out and Custer was killed, as were two of his brothers, a nephew, and a brother-in-law. The total U.S. casualty count included 268 dead and 55 severely wounded (six died later from their wounds), including four Crow

A crow is a bird of the genus ''Corvus'', or more broadly a synonym for all of ''Corvus''. Crows are generally black in colour. The word "crow" is used as part of the common name of many species. The related term " raven" is not pinned scientifica ...

Indian scouts and at least two Arikara

Arikara (), also known as Sahnish,

''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011)

Indian scouts.

Public response to the ''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011)

Great Sioux War

The Great Sioux War of 1876, also known as the Black Hills War, was a series of battles and negotiations that occurred in 1876 and 1877 in an alliance of Lakota Sioux and Northern Cheyenne against the United States. The cause of the war was the ...

varied in the immediate aftermath of the battle. Libbie Custer

Elizabeth Bacon Custer (née Bacon; April 8, 1842 – April 4, 1933) was an American author and public speaker, and the wife of Brevet Major General George Armstrong Custer, United States Army. She spent most of their marriage in relative prox ...

, Custer's widow, soon worked to burnish her husband's memory, and during the following decades Custer and his troops came to be considered heroic figures in American history. The battle, and Custer's actions in particular, have been studied extensively by historians. Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument honors those who fought on both sides.

Background

Battlefield and surrounding areas

In 1805, fur trader François Antoine Larocque reported joining aCrow

A crow is a bird of the genus ''Corvus'', or more broadly a synonym for all of ''Corvus''. Crows are generally black in colour. The word "crow" is used as part of the common name of many species. The related term " raven" is not pinned scientifica ...

camp in the Yellowstone

Yellowstone National Park is an American national park located in the western United States, largely in the northwest corner of Wyoming and extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U.S. Congress with the Yellow ...

area. On the way he noted that the Crow hunted buffalo on the " Small Horn River". St. Louis-based fur trader Manuel Lisa built Fort Raymond

Fort Raymond or alternatively Manuel's Fort or Fort Manuel, was an outpost established by fur trader Manuel Lisa and was named after his son.Morris, Larry E. ''The Perilous West''. Lanham, MD: Row & Littlefield Publishing. 2013, p. 20. The post was ...

in 1807 for trade with the Crow. It was located near the confluence of the Yellowstone

Yellowstone National Park is an American national park located in the western United States, largely in the northwest corner of Wyoming and extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U.S. Congress with the Yellow ...

and Bighorn rivers, about north of the future battlefield. The area is first noted in the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie.

In the latter half of the 19th century, tensions increased between the Native inhabitants of the Great Plains of the US and encroaching settlers. This resulted in a series of conflicts known as the Sioux Wars

The Sioux Wars were a series of conflicts between the United States and various subgroups of the Sioux people which occurred in the later half of the 19th century. The earliest conflict came in 1854 when a fight broke out at Fort Laramie in Wyom ...

, which took place from 1854 to 1890. While some of the indigenous people eventually agreed to relocate to ever-shrinking reservations, a number of them resisted, sometimes fiercely.

On May 7, 1868, the valley of the Little Bighorn became a tract in the eastern part of the new Crow Indian Reservation

The Crow Indian Reservation is the homeland of the Crow Tribe. Established 1868, the reservation is located in parts of Big Horn, Yellowstone, and Treasure counties in southern Montana in the United States. The Crow Tribe has an enrolled mem ...

in the center of the old Crow country. There were numerous skirmishes between the Sioux and Crow tribes,White, Richard: The Winning of the West: The Expansion of the Western Sioux in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. The Journal of American History. Vol. 65, No. 2 (Sept. 1978), p. 342. so when the Sioux were in the valley in 1876 without the consent of the Crow tribe, the Crow supported the US Army to expel the Sioux (e.g., Crows enlisted as Army scoutsBradley, James H.: Journal of James H. Bradley. The Sioux Campaign of 1876 under the Command of General John Gibbon. ''Contributions to the Historical Society of Montana''. p. 163. and Crow warriors would fight in the nearby Battle of the Rosebud).

The geography of the battlefield is very complex, consisting of dissected uplands, rugged bluffs, the Little Bighorn River, and adjacent plains, all areas close to one another. Vegetation varies widely from one area to the next.

The battlefield is known as "Greasy Grass" to the Lakota Sioux, Dakota Sioux

The Dakota (pronounced , Dakota language: ''Dakȟóta/Dakhóta'') are a Native American tribe and First Nations band government in North America. They compose two of the three main subcultures of the Sioux people, and are typically divided into ...

, Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian languages, Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized tribe, federally recognize ...

, and most other Plains Indians

Plains Indians or Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies are the Native American tribes and First Nation band governments who have historically lived on the Interior Plains (the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies) o ...

; however, in contemporary accounts by participants, it was referred to as the "Valley of Chieftains".

1876 Sun Dance ceremony

Among thePlains Tribes

Plains Indians or Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies are the Native American tribes and First Nation band governments who have historically lived on the Interior Plains (the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies) of ...

, the long-standing ceremonial tradition known as the Sun Dance

The Sun Dance is a ceremony practiced by some Native Americans in the United States and Indigenous peoples in Canada, primarily those of the Plains cultures. It usually involves the community gathering together to pray for healing. Individu ...

was the most important religious event of the year. It is a time for prayer and personal sacrifice for the community, as well as making personal vows. Towards the end of spring in 1876, the Lakota and the Cheyenne held a Sun Dance that was also attended by some "agency Indians" who had slipped away from their reservations. During a Sun Dance around June 5, 1876, on Rosebud Creek in Montana

Montana () is a U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West List of regions of the United States#Census Bureau-designated regions and divisions, division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North ...

, Sitting Bull

Sitting Bull ( lkt, Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake ; December 15, 1890) was a Hunkpapa Lakota leader who led his people during years of resistance against United States government policies. He was killed by Indian agency police on the Standing Roc ...

, the spiritual leader of the Hunkpapa Lakota

The Hunkpapa ( Lakota: ) are a Native American group, one of the seven council fires of the Lakota tribe. The name ' is a Lakota word, meaning "Head of the Circle" (at one time, the tribe's name was represented in European-American records a ...

, reportedly had a vision of "soldiers falling into his camp like grasshoppers from the sky." At the same time US military officials were conducting a summer campaign to force the Lakota and the Cheyenne back to their reservations, using infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and m ...

and cavalry in a so-called "three-pronged approach".

1876 U.S. military campaign

Col.

Col. John Gibbon

John Gibbon (April 20, 1827 – February 6, 1896) was a career United States Army officer who fought in the American Civil War and the Indian Wars.

Early life

Gibbon was born in the Holmesburg section of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the fou ...

's column of six companies (A, B, E, H, I, and K) of the 7th Infantry and four companies (F, G, H, and L) of the 2nd Cavalry marched east from Fort Ellis

Fort Ellis was a United States Army fort established August 27, 1867, east of present-day Bozeman, Montana. Troops from the fort participated in many major campaigns of the Indian Wars. The fort was closed on August 2, 1886.

History

The fort w ...

in western Montana on March 30 to patrol the Yellowstone River

The Yellowstone River is a tributary of the Missouri River, approximately long, in the Western United States. Considered the principal tributary of upper Missouri, via its own tributaries it drains an area with headwaters across the mountains a ...

. Brig. Gen. George Crook

George R. Crook (September 8, 1828 – March 21, 1890) was a career United States Army officer, most noted for his distinguished service during the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. During the 1880s, the Apache nicknamed Crook ''Nanta ...

's column of ten companies (A, B, C, D, E, F, G, I, L, and M) of the 3rd Cavalry, five companies (A, B, D, E, and I) of the 2nd Cavalry, two companies (D and F) of the 4th Infantry, and three companies (C, G, and H) of the 9th Infantry moved north from Fort Fetterman in the Wyoming Territory

The Territory of Wyoming was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 25, 1868, until July 10, 1890, when it was admitted to the Union as the State of Wyoming. Cheyenne was the territorial capital. The bo ...

on May 29, marching toward the Powder River

Powder River may refer to:

Places

* Powder River (Wyoming and Montana), in Wyoming and Montana in the United States

* Powder River Country, the area around the above river

* Powder River (Oregon), in Oregon in the United States

* Powder River Ba ...

area. Brig. Gen. Alfred Terry

Alfred Howe Terry (November 10, 1827 – December 16, 1890) was a Union general in the American Civil War and the military commander of the Dakota Territory from 1866 to 1869, and again from 1872 to 1886. In 1865, Terry led Union troops to v ...

's column, including twelve companies (A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, K, L, and M) of the 7th Cavalry under Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Custer graduated from West Point in 1861 at the bottom of his clas ...

's immediate command, Companies C and G of the 17th Infantry

The 17th Infantry (The Loyal Regiment) was an infantry regiment of the Bengal Army, later of the united British Indian Army. It was formed at Phillour in 1858 by Major J. C. Innes from men of the 3rd, 36th and 61st Bengal Native Infantry regiment ...

, and the Gatling gun detachment of the 20th Infantry departed westward from Fort Abraham Lincoln in the Dakota Territory

The Territory of Dakota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1861, until November 2, 1889, when the final extent of the reduced territory was split and admitted to the Union as the states of ...

on May 17. They were accompanied by teamsters and packers with 150 wagons and a large contingent of pack mules that reinforced Custer. Companies C, D, and I of the 6th Infantry moved along the Yellowstone River

The Yellowstone River is a tributary of the Missouri River, approximately long, in the Western United States. Considered the principal tributary of upper Missouri, via its own tributaries it drains an area with headwaters across the mountains a ...

from Fort Buford

Fort Buford was a United States Army Post at the confluence of the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers in Dakota Territory, present day North Dakota, and the site of Sitting Bull's surrender in 1881.Ewers, John C. (1988): "When Sitting Bull Surrend ...

on the Missouri River to set up a supply depot and joined Terry on May 29 at the mouth of the Powder River

Powder River may refer to:

Places

* Powder River (Wyoming and Montana), in Wyoming and Montana in the United States

* Powder River Country, the area around the above river

* Powder River (Oregon), in Oregon in the United States

* Powder River Ba ...

. They were later joined there by the steamboat ''Far West Far West may refer to:

Places

* Western Canada, or the West

** British Columbia Coast

* Western United States, or Far West

** West Coast of the United States

* American frontier, or Far West, Old West, or Wild West

* Far West (Taixi), a term used ...

'', which was loaded with 200 tons of supplies from Fort Abraham Lincoln.

7th Cavalry organization

The 7th Cavalry had been created just after the American Civil War. Many men were veterans of the war, including most of the leading officers. A significant portion of the regiment had previously served 4½ years atFort Riley

Fort Riley is a United States Army installation located in North Central Kansas, on the Kansas River, also known as the Kaw, between Junction City and Manhattan. The Fort Riley Military Reservation covers 101,733 acres (41,170 ha) in G ...

, Kansas, during which time it fought one major engagement and numerous skirmishes, experiencing casualties of 36 killed and 27 wounded. Six other troopers had died of drowning and 51 in cholera epidemics. In November 1868, while stationed in Kansas, the 7th Cavalry under Custer had routed Black Kettle

Black Kettle (Cheyenne: Mo'ohtavetoo'o) (c. 1803November 27, 1868) was a prominent leader of the Southern Cheyenne during the American Indian Wars. Born to the ''Northern Só'taeo'o / Só'taétaneo'o'' band of the Northern Cheyenne in the Black ...

's Southern Cheyenne camp on the Washita River

The Washita River () is a river in the states of Texas and Oklahoma in the United States. The river is long and terminates at its confluence with the Red River, which is now part of Lake Texoma () on the TexasOklahoma border.

Geography

The ...

in the Battle of Washita River, an attack which was at the time labeled a "massacre of innocent Indians" by the Indian Bureau

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States federal government of the United States, federal agency within the U.S. Department of the Interior, Department of the Interior. It is responsible for im ...

.

By the time of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, half of the 7th Cavalry's companies had just returned from 18 months of constabulary duty in the

By the time of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, half of the 7th Cavalry's companies had just returned from 18 months of constabulary duty in the Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion in the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states most dependent on plantations and slavery prior to the American Civil War. Following the war ...

, having been recalled to Fort Abraham Lincoln, Dakota Territory

The Territory of Dakota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1861, until November 2, 1889, when the final extent of the reduced territory was split and admitted to the Union as the states of ...

to reassemble the regiment for the campaign. About 20% of the troopers had been enlisted in the prior seven months (139 of an enlisted roll of 718), were only marginally trained and had no combat or frontier experience. About 60% of these recruits were American, the rest were Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located enti ...

an immigrants (Most were Irish and German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

)—just as many of the veteran troopers had been before their enlistments. Archaeological evidence suggests that many of these troopers were malnourished and in poor physical condition, despite being the best-equipped and supplied regiment in the Army.

Of the 45 officers and 718 troopers then assigned to the 7th Cavalry (including a second lieutenant detached from the 20th Infantry and serving in Company L), 14 officers (including the regimental commander) and 152 troopers did not accompany the 7th during the campaign. The regimental commander, Colonel Samuel D. Sturgis

Samuel Davis Sturgis (June 11, 1822 – September 28, 1889) was a senior Officer (armed forces), officer of the United States Army. A veteran of the Mexican–American War, Mexican War, American Civil War, Civil War, and American Indian Wars, I ...

, was on detached duty as the Superintendent of Mounted Recruiting Service and commander of the Cavalry Depot in St. Louis, Missouri, which left Lieutenant Colonel Custer in command of the regiment. The ratio of troops detached for other duty (approximately 22%) was not unusual for an expedition of this size, and part of the officer shortage was chronic, due to the Army's rigid seniority system: three of the regiment's 12 captains were permanently detached, and two had never served a day with the 7th since their appointment in July 1866.Capt. Sheridan (Company L), the brother of Lt. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan, served only seven months in 1866–67 before becoming permanent aide to his brother but remained on the rolls until 1882. Capt. Ilsley (Company E) was aide to Maj. Gen John Pope from 1866 to 1879, when he finally joined his command. Capt. Tourtelotte (Company G) never joined the 7th. A fourth captain, Owen Hale (Company K), was the regiment's recruiting officer in St. Louis and rejoined his company immediately. Three second lieutenant vacancies (in E, H, and L Companies) were also unfilled.

Battle of the Rosebud

The Army's coordination and planning began to go awry on June 17, 1876, when Crook's column retreated after the Battle of the Rosebud, just to the southeast of the eventual Little Bighorn battlefield. Surprised and according to some accounts astonished by the unusually large numbers of Native Americans, Crook held the field at the end of the battle but felt compelled by his losses to pull back, regroup, and wait for reinforcements. Unaware of Crook's battle, Gibbon and Terry proceeded, joining forces in early June near the mouth of Rosebud Creek. They reviewed Terry's plan calling for Custer's regiment to proceed south along the Rosebud while Terry and Gibbon's united forces would move in a westerly direction toward the Bighorn and Little Bighorn rivers. As this was the likely location of Native encampments, all army elements had been instructed to converge there around June 26 or 27 in an attempt to engulf the Native Americans. On June 22, Terry ordered the 7th Cavalry, composed of 31 officers and 566 enlisted men under Custer, to begin a reconnaissance in force and pursuit along the Rosebud, with the prerogative to "depart" from orders if Custer saw "sufficient reason". Custer had been offered the use of Gatling guns but declined, believing they would slow his rate of march.Little Bighorn

While the Terry-Gibbon column was marching toward the mouth of the Little Bighorn, on the evening of June 24, Custer's Indian scouts arrived at an overlook known as the Crow's Nest, east of the Little Bighorn River. At sunrise on June 25, Custer's scouts reported they could see a massive pony herd and signs of the Native American village roughly in the distance. After a night's march, the tired officer who was sent with the scouts could see neither, and when Custer joined them, he was also unable to make the sighting. Custer's scouts also spotted the regimental cooking fires that could be seen from away, disclosing the regiment's position. Custer contemplated a surprise attack against the encampment the following morning of June 26, but he then received a report informing him several hostiles had discovered the trail left by his troops. Assuming his presence had been exposed, Custer decided to attack the village without further delay. On the morning of June 25, Custer divided his 12 companies into three battalions in anticipation of the forthcoming engagement. Three companies were placed under the command of MajorMarcus Reno

Marcus Albert Reno (November 15, 1834 – March 30, 1889) was a United States career military officer who served in the American Civil War where he was a combatant in a number of major battles, and later under George Armstrong Custer in the Gre ...

(A, G, and M) and three were placed under the command of Captain Frederick Benteen

Frederick William Benteen (August 24, 1834 – June 22, 1898) was a military officer who first fought during the American Civil War. He was appointed to commanding ranks during the Indian Campaigns and Great Sioux War against the Lakota an ...

(H, D, and K). Five companies (C, E, F, I, and L) remained under Custer's immediate command. The 12th, Company B under Captain Thomas McDougall, had been assigned to escort the slower pack train carrying provisions and additional ammunition.

Unknown to Custer, the group of Native Americans seen on his trail was actually leaving the encampment and did not alert the rest of the village. Custer's scouts warned him about the size of the village, with Mitch Bouyer

Mitch Boyer (sometimes spelled 'Bowyer', 'Buoyer', 'Bouyer' or 'Buazer', or in Creole, 'Boye') (1837 – June 25, 1876) was an interpreter and guide in the Old West following the American Civil War. General John Gibbon called him "next to Jim B ...

reportedly saying, "General, I have been with these Indians for 30 years, and this is the largest village I have ever heard of." Custer's overriding concern was that the Native American group would break up and scatter. The command began its approach to the village at noon and prepared to attack in full daylight.

With an impending sense of doom, the Crow scout Half Yellow Face

Half Yellow Face (or Ischu Shi Dish in the Crow language) (1830? to 1879?) was the leader of the six Crow Scouts for George Armstrong Custer's 7th Cavalry during the 1876 campaign against the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne. Half Yellow Face l ...

prophetically warned Custer (speaking through the interpreter Mitch Bouyer), "You and I are going home today by a road we do not know."

Prelude

Military assumptions prior to the battle

Number of Indian warriors

As the Army moved into the field on its expedition, it was operating with incorrect assumptions as to the number of Indians it would encounter. These assumptions were based on inaccurate information provided by the Indian Agents that no more than 800 "hostiles" were in the area. The Indian Agents based this estimate on the number of Lakota that Sitting Bull and other leaders had reportedly led off the reservation in protest of U.S. government policies. It was in fact a correct estimate until several weeks before the battle when the "reservation Indians" joined Sitting Bull's ranks for the summer buffalo hunt. The agents did not consider the many thousands of these "reservation Indians" who had unofficially left the reservation to join their "unco-operative non-reservation cousins led by Sitting Bull". Thus, Custer unknowingly faced thousands of Indians, including the 800 non-reservation "hostiles". All Army plans were based on the incorrect numbers. Although Custer was criticized after the battle for not having accepted reinforcements and for dividing his forces, it appears that he had accepted the same official government estimates of hostiles in the area which Terry and Gibbon had also accepted. Historian James Donovan notes, however, that when Custer later asked interpreter Fred Gerard for his opinion on the size of the opposition, he estimated the force at 1,100 warriors.

Additionally, Custer was more concerned with preventing the escape of the Lakota and Cheyenne than with fighting them. From his observation, as reported by John Martin ( Giovanni Martino),Charles Windolph, Frazier Hunt, Robert Hunt, Neil Mangum, ''I Fought with Custer: The Story of Sergeant Windolph, Last Survivor of the Battle of the Little Big Horn: with Explanatory Material and Contemporary Sidelights on the Custer Fight'', University of Nebraska Press, 1987, p. 86. Custer assumed the warriors had been sleeping in on the morning of the battle, to which virtually every native account attested later, giving Custer a false estimate of what he was up against. When he and his scouts first looked down on the village from the Crow's Nest across the Little Bighorn River, they could see only the herd of ponies. Later, looking from a hill away after parting with Reno's command, Custer could observe only women preparing for the day, and young boys taking thousands of horses out to graze south of the village. Custer's Crow scouts told him it was the largest native village they had ever seen. When the scouts began changing back into their native dress right before the battle, Custer released them from his command. While the village was enormous, Custer still thought there were far fewer warriors to defend the village.

Finally, Custer may have assumed when he encountered the Native Americans that his subordinate Benteen, who was with the pack train, would provide support. Rifle volleys were a standard way of telling supporting units to come to another unit's aid. In a subsequent official 1879 Army investigation requested by Major Reno, the Reno Board of Inquiry (RCOI), Benteen and Reno's men testified that they heard distinct rifle volleys as late as 4:30 pm during the battle.

Custer had initially wanted to take a day to scout the village before attacking; however, when men who went back looking for supplies accidentally dropped by the pack train, they discovered that their track had already been discovered by Indians. Reports from his scouts also revealed fresh pony tracks from ridges overlooking his formation. It became apparent that the warriors in the village were either aware or would soon be aware of his approach. Fearing that the village would break up into small bands that he would have to chase, Custer began to prepare for an immediate attack.Donovan, loc 3699

As the Army moved into the field on its expedition, it was operating with incorrect assumptions as to the number of Indians it would encounter. These assumptions were based on inaccurate information provided by the Indian Agents that no more than 800 "hostiles" were in the area. The Indian Agents based this estimate on the number of Lakota that Sitting Bull and other leaders had reportedly led off the reservation in protest of U.S. government policies. It was in fact a correct estimate until several weeks before the battle when the "reservation Indians" joined Sitting Bull's ranks for the summer buffalo hunt. The agents did not consider the many thousands of these "reservation Indians" who had unofficially left the reservation to join their "unco-operative non-reservation cousins led by Sitting Bull". Thus, Custer unknowingly faced thousands of Indians, including the 800 non-reservation "hostiles". All Army plans were based on the incorrect numbers. Although Custer was criticized after the battle for not having accepted reinforcements and for dividing his forces, it appears that he had accepted the same official government estimates of hostiles in the area which Terry and Gibbon had also accepted. Historian James Donovan notes, however, that when Custer later asked interpreter Fred Gerard for his opinion on the size of the opposition, he estimated the force at 1,100 warriors.

Additionally, Custer was more concerned with preventing the escape of the Lakota and Cheyenne than with fighting them. From his observation, as reported by John Martin ( Giovanni Martino),Charles Windolph, Frazier Hunt, Robert Hunt, Neil Mangum, ''I Fought with Custer: The Story of Sergeant Windolph, Last Survivor of the Battle of the Little Big Horn: with Explanatory Material and Contemporary Sidelights on the Custer Fight'', University of Nebraska Press, 1987, p. 86. Custer assumed the warriors had been sleeping in on the morning of the battle, to which virtually every native account attested later, giving Custer a false estimate of what he was up against. When he and his scouts first looked down on the village from the Crow's Nest across the Little Bighorn River, they could see only the herd of ponies. Later, looking from a hill away after parting with Reno's command, Custer could observe only women preparing for the day, and young boys taking thousands of horses out to graze south of the village. Custer's Crow scouts told him it was the largest native village they had ever seen. When the scouts began changing back into their native dress right before the battle, Custer released them from his command. While the village was enormous, Custer still thought there were far fewer warriors to defend the village.

Finally, Custer may have assumed when he encountered the Native Americans that his subordinate Benteen, who was with the pack train, would provide support. Rifle volleys were a standard way of telling supporting units to come to another unit's aid. In a subsequent official 1879 Army investigation requested by Major Reno, the Reno Board of Inquiry (RCOI), Benteen and Reno's men testified that they heard distinct rifle volleys as late as 4:30 pm during the battle.

Custer had initially wanted to take a day to scout the village before attacking; however, when men who went back looking for supplies accidentally dropped by the pack train, they discovered that their track had already been discovered by Indians. Reports from his scouts also revealed fresh pony tracks from ridges overlooking his formation. It became apparent that the warriors in the village were either aware or would soon be aware of his approach. Fearing that the village would break up into small bands that he would have to chase, Custer began to prepare for an immediate attack.Donovan, loc 3699

Role of Indian noncombatants in Custer's strategy

Custer's field strategy was designed to engage non-combatants at the encampments on the Little Bighorn to capture women, children, and the elderly or disabled to serve as hostages to convince the warriors to surrender and comply with federal orders to relocate. Custer's battalions were poised to "ride into the camp and secure non-combatant hostages", and "forc the warriors to surrender". Author Evan S. Connell observed that if Custer could occupy the village before widespread resistance developed, the Sioux and Cheyenne warriors "would be obliged to surrender, because if they started to fight, they would be endangering their families." In Custer's book ''My Life on the Plains'', published two years before the Battle of the Little Bighorn, he asserted: On Custer's decision to advance up the bluffs and descend on the village from the east, Lt. Edward Godfrey of Company K surmised: The Sioux and Cheyenne fighters were acutely aware of the danger posed by the military engagement of non-combatants and that "even a semblance of an attack on the women and children" would draw the warriors back to the village, according to historian John S. Gray. Such was their concern that an apparent reconnaissance by Capt. Yates' E and F Companies at the mouth of Medicine Tail Coulee (Minneconjou Ford) caused hundreds of warriors to disengage from the Reno valley fight and return to deal with the threat to the village. Some authors and historians, based on archaeological evidence and reviews of native testimony, speculate that Custer attempted to cross the river at a point further north they refer to as Ford D. According to Richard A. Fox, James Donovan, and others, Custer proceeded with a wing of his battalion (Yates' E and F companies) north and opposite the Cheyenne circle at that crossing, which provided "access to theomen and children

An omen (also called ''portent'') is a phenomenon that is believed to foretell the future, often signifying the advent of change. It was commonly believed in ancient times, and still believed by some today, that omens bring divine messages fr ...

fugitives." Yates's force "posed an immediate threat to fugitive Indian families..." gathering at the north end of the huge encampment; he then persisted in his efforts to "seize women and children" even as hundreds of warriors were massing around Keogh's wing on the bluffs. Yates' wing, descending to the Little Bighorn River at Ford D, encountered "light resistance", undetected by the Indian forces ascending the bluffs east of the village. Custer was almost within "striking distance of the refugees" before abandoning the ford and returning to Custer Ridge.

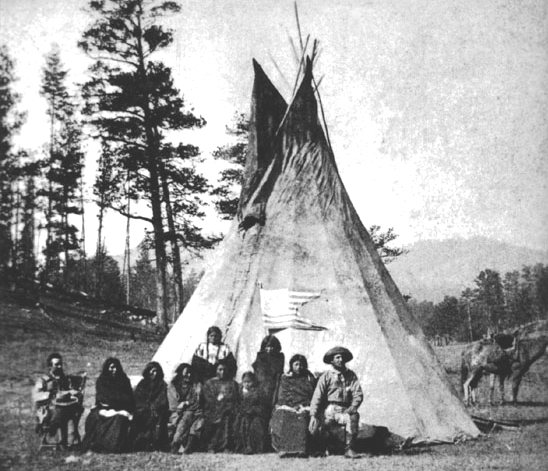

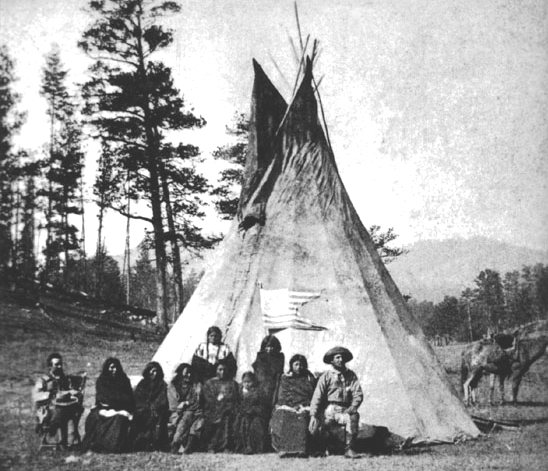

Lone Teepee

The ''Lone Teepee'' (or ''Tipi'') was a landmark along the 7th Cavalry's march. It was where the Indian encampment had been a week earlier, during the Battle of the Rosebud on June 17, 1876. The Indians had left a singleteepee

A tipi , often called a lodge in English, is a conical tent, historically made of animal hides or pelts, and in more recent generations of canvas, stretched on a framework of wooden poles. The word is Siouan, and in use in Dakhótiyapi, Lakȟ� ...

standing (some reports mention a second that had been partially dismantled), and in it was the body of a Sans Arc

The Sans Arc, or Itázipčho (''Itazipcola'', ''Hazipco'' - ‘Those who hunt without bows’) in Lakota, are a subdivision of the Lakota people. Sans Arc is the French translation of the Lakota name which means, "Without bows." The translator ...

warrior, Old She-Bear, who had been wounded in the battle. He had died a couple of days after the Rosebud battle, and it was the custom of the Indians to move camp when a warrior died and leave the body with its possessions. The Lone Teepee was an important location during the Battle of the Little Bighorn for several reasons, including:

* It is where Custer gave Reno his final orders to attack the village ahead. It is also where some Indians who had been following the command were seen and Custer assumed he had been discovered.

* Many of the survivors' accounts use the Lone Teepee as a point of reference for event times or distances.

* Knowing this location helps establish the pattern of the Indians' movements to the encampment on the river where the soldiers found them.

Battle

Reno's attack

skirmish line

Skirmishers are light infantry or light cavalry soldiers deployed as a vanguard, flank guard or rearguard to screen a tactical position or a larger body of friendly troops from enemy advances. They are usually deployed in a skirmish line, an i ...

, according to standard army doctrine. In this formation, every fourth trooper held the horses for the troopers in firing position, with separating each trooper, officers to their rear and troopers with horses behind the officers. This formation reduced Reno's firepower by 25 percent. As Reno's men fired into the village and killed, by some accounts, several wives and children of the Sioux leader, Chief Gall (in Lakota, ''Phizí''), the mounted warriors began streaming out to meet the attack. With Reno's men anchored on their right by the protection of the tree line and bend in the river, the Indians rode against the center and exposed left end of Reno's line. After about 20 minutes of long-distance firing, Reno had taken only one casualty, but the odds against him had risen (Reno estimated five to one), and Custer had not reinforced him. Trooper Billy Jackson reported that by then, the Indians had begun massing in the open area shielded by a small hill to the left of Reno's line and to the right of the Indian village. From this position the Indians mounted an attack of more than 500 warriors against the left and rear of Reno's line, turning Reno's exposed left flank. This forced a hasty withdrawal into the timber along the bend in the river. Here the Native Americans pinned Reno and his men down and tried to set fire to the brush to try to drive the soldiers out of their position.

Reno's Arikara scout, Bloody Knife, was shot in the head, splattering brains and blood onto Reno's face. The shaken Reno ordered his men to dismount and mount again. He then said, "All those who wish to make their escape follow me." Abandoning the wounded (dooming them to their deaths), he led a disorderly rout for a mile next to the river. He made no attempt to engage the Indians to prevent them from picking off men in the rear. The retreat was immediately disrupted by Cheyenne attacks at close quarters. A steep bank, some high, awaited the mounted men as they crossed the river; some horses fell back onto others below them. Indians both fired on the soldiers from a distance, and within close quarters, pulled them off their horses and clubbed their heads. Later, Reno reported that three officers and 29 troopers had been killed during the retreat and subsequent fording of the river. Another officer and 13–18 men were missing. Most of these missing men were left behind in the timber, although many eventually rejoined the detachment.

Reno and Benteen on Reno Hill

Atop the bluffs, known today as Reno Hill, Reno's depleted and shaken troops were joined about a half-hour later by Captain Benteen's column (Companies D, H and K), arriving from the south. This force had been returning from a lateral scouting mission when it had been summoned by Custer's messenger, Italian bugler John Martin (Giovanni Martino) with the handwritten message "Benteen. Come on, Big Village, Be quick, Bring packs. P.S. Bring Packs." This message made no sense to Benteen, as his men would be needed more in a fight than the packs carried by herd animals. Though both men inferred that Custer was engaged in battle, Reno refused to move until the packs arrived so his men could resupply. The detachments were later reinforced by McDougall's Company B and the pack train. The 14 officers and 340 troopers on the bluffs organized an all-around defense and dug rifle pits using whatever implements they had among them, including knives. This practice had become standard during the last year of theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

, with both Union and Confederate troops utilizing knives, eating utensils, mess plates and pans to dig effective battlefield fortifications.

Crazy Horse

Crazy Horse ( lkt, Tȟašúŋke Witkó, italic=no, , ; 1840 – September 5, 1877) was a Lakota war leader of the Oglala band in the 19th century. He took up arms against the United States federal government to fight against encroachment by ...

, White Bull

White Bull ( Lakota: Tȟatȟáŋka Ská) (April 1849 – June 21, 1947) was the nephew of Sitting Bull, and a famous warrior in his own right. White Bull participated in the Battle of the Little Bighorn on June 25, 1876.

Early life

Born in t ...

, Hump, Chief Gall and others.Michno, Gregory F., ''Lakota Noon, the Indian narrative of Custer's defeat'', Mountain Press, 1997, pp. 284–285. . Other native accounts contradict this understanding, however, and the time element remains a subject of debate. The other entrenched companies eventually left Reno Hill and followed Weir by assigned battalions—first Benteen, then Reno, and finally the pack train. The men on Weir Ridge were attacked by natives, increasingly coming from the apparently concluded Custer engagement, forcing all seven companies to return to the bluff before the pack train had moved even a quarter mile (). The companies remained pinned down on the bluff, fending off the Indians for three hours until night fell. The soldiers dug crude trenches as the Indians performed their war dance.

Benteen was hit in the heel of his boot by an Indian bullet. At one point, he led a counterattack to push back Indians who had continued to crawl through the grass closer to the soldier's positions.

Custer's fight

The precise details of Custer's fight and his movements before and during the battle are largely conjectural since none of the men who went forward with Custer's battalion (the five companies under his immediate command) survived the battle. Later accounts from surviving Indians are useful but are sometimes conflicting and unclear. While the gunfire heard on the bluffs by Reno and Benteen's men during the afternoon of June 25 was probably from Custer's fight, the soldiers on Reno Hill were unaware of what had happened to Custer until General Terry's arrival two days later on June 27. They were reportedly stunned by the news. When the army examined the Custer battle site, soldiers could not determine fully what had transpired. Custer's force of roughly 210 men had been engaged by the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne about to the north of Reno and Benteen's defensive position. Evidence of organized resistance included an apparent skirmish line on Calhoun Hill and apparent breastworks made of dead horses on Custer Hill. By the time troops came to recover the bodies, the Lakota and Cheyenne had already removed most of their own dead from the field. The troops found most of Custer's dead men stripped of their clothing, ritually mutilated, and in a state of decomposition, making identification of many impossible.Brininstool, 60–62. The soldiers identified the 7th Cavalry's dead as well as they could and hastily buried them where they fell. Custer's body was found with two gunshot wounds, one to his left chest and the other to his left temple. Either wound would have been fatal, though he appeared to have bled from only the chest wound; some scholars believe his head wound may have been delivered postmortem. Some Lakota oral histories assert that Custer, having sustained a wound, committed suicide to avoid capture and subsequent torture. This would be inconsistent with his known right-handedness, but that does not rule out assisted suicide (other native accounts note several soldiers committing suicide near the end of the battle). Custer's body was found near the top of Custer Hill, which also came to be known as "Last Stand Hill". There the United States erected a tall memorial obelisk inscribed with the names of the 7th Cavalry's casualties. Several days after the battle, Curley, Custer's Crow scout who had left Custer near Medicine Tail Coulee (a drainage which led to the river), recounted the battle, reporting that Custer had attacked the village after attempting to cross the river. He was driven back, retreating toward the hill where his body was found. As the scenario seemed compatible with Custer's aggressive style of warfare and with evidence found on the ground, it became the basis of many popular accounts of the battle. According to Pretty Shield, the wife of Goes-Ahead (another Crow scout for the 7th Cavalry), Custer was killed while crossing the river: "...and he died there, died in the water of the Little Bighorn, with Two-bodies, and the blue soldier carrying his flag".Linderman, F. (1932) ''Pretty-shield: Medicine Woman of the Crows''. University of Nebraska Press. . (Preface © 2003 by Alma Snell and Becky Matthews). In this account, Custer was allegedly killed by a Lakota called Big-nose. However, in Chief Gall's version of events, as recounted to Lt. Edward Settle Godfrey, Custer did not attempt to ford the river and the nearest that he came to the river or village was his final position on the ridge.Godfrey, E. S. (1892''Custer's Last Battle''

. The Century Magazine, Vol. XLIII, No. 3, January. New York: The Century Company. Chief Gall's statements were corroborated by other Indians, notably the wife of Spotted Horn Bull. Given that no bodies of men or horses were found anywhere near the ford, Godfrey himself concluded "that Custer did not go to the ford with any body of men". Cheyenne oral tradition credits Buffalo Calf Road Woman with striking the blow that knocked Custer off his horse before he died.Martin J. Kidston, "Northern Cheyenne break vow of silence"

, ''Helena Independent Record'', June 28, 2005. RetrievedOctober 23, 2009.

Custer at Minneconjou Ford

Having isolated Reno's force and driven them away from their encampment, the bulk of the native warriors were free to pursue Custer. The route taken by Custer to his "Last Stand" remains a subject of debate. One possibility is that after ordering Reno to charge, Custer continued down Reno Creek to within about a half-mile (800 m) of the Little Bighorn, but then turned north and climbed up the bluffs, reaching the same spot to which Reno would soon retreat. From this point on the other side of the river, he could see Reno charging the village. Riding north along the bluffs, Custer could have descended into Medicine Tail Coulee. Some historians believe that part of Custer's force descended the coulee, going west to the river and attempting unsuccessfully to cross into the village. According to some accounts, a small contingent of Indian sharpshooters effectively opposed this crossing.

White Cow Bull claimed to have shot a leader wearing a buckskin jacket off his horse in the river. While no other Indian account supports this claim, if White Bull did shoot a buckskin-clad leader off his horse, some historians have argued that Custer may have been seriously wounded by him. Some Indian accounts claim that besides wounding one of the leaders of this advance, a soldier carrying a company guidon was also hit. Troopers had to dismount to help the wounded men back onto their horses. The fact that either of the non-mutilation wounds to Custer's body (a bullet wound below the heart and a shot to the left temple) would have been instantly fatal casts doubt on his being wounded and remounted.

Reports of an attempted fording of the river at Medicine Tail Coulee might explain Custer's purpose for Reno's attack, that is, a coordinated "hammer-and-anvil" maneuver, with Reno's holding the Indians at bay at the southern end of the camp, while Custer drove them against Reno's line from the north. Other historians have noted that if Custer did attempt to cross the river near Medicine Tail Coulee, he may have believed it was the north end of the Indian camp, only to discover that it was the middle. Some Indian accounts, however, place the Northern Cheyenne encampment and the north end of the overall village to the left (and south) of the opposite side of the crossing. The precise location of the north end of the village remains in dispute, however.

Having isolated Reno's force and driven them away from their encampment, the bulk of the native warriors were free to pursue Custer. The route taken by Custer to his "Last Stand" remains a subject of debate. One possibility is that after ordering Reno to charge, Custer continued down Reno Creek to within about a half-mile (800 m) of the Little Bighorn, but then turned north and climbed up the bluffs, reaching the same spot to which Reno would soon retreat. From this point on the other side of the river, he could see Reno charging the village. Riding north along the bluffs, Custer could have descended into Medicine Tail Coulee. Some historians believe that part of Custer's force descended the coulee, going west to the river and attempting unsuccessfully to cross into the village. According to some accounts, a small contingent of Indian sharpshooters effectively opposed this crossing.

White Cow Bull claimed to have shot a leader wearing a buckskin jacket off his horse in the river. While no other Indian account supports this claim, if White Bull did shoot a buckskin-clad leader off his horse, some historians have argued that Custer may have been seriously wounded by him. Some Indian accounts claim that besides wounding one of the leaders of this advance, a soldier carrying a company guidon was also hit. Troopers had to dismount to help the wounded men back onto their horses. The fact that either of the non-mutilation wounds to Custer's body (a bullet wound below the heart and a shot to the left temple) would have been instantly fatal casts doubt on his being wounded and remounted.

Reports of an attempted fording of the river at Medicine Tail Coulee might explain Custer's purpose for Reno's attack, that is, a coordinated "hammer-and-anvil" maneuver, with Reno's holding the Indians at bay at the southern end of the camp, while Custer drove them against Reno's line from the north. Other historians have noted that if Custer did attempt to cross the river near Medicine Tail Coulee, he may have believed it was the north end of the Indian camp, only to discover that it was the middle. Some Indian accounts, however, place the Northern Cheyenne encampment and the north end of the overall village to the left (and south) of the opposite side of the crossing. The precise location of the north end of the village remains in dispute, however.

In 1908,

In 1908, Edward Curtis

Edward Sherriff Curtis (February 19, 1868 – October 19, 1952) was an American photographer and ethnologist whose work focused on the American West and on Native American people. Sometimes referred to as the "Shadow Catcher", Curtis traveled ...

, the famed ethnologist and photographer of the Native American Indians, made a detailed personal study of the battle, interviewing many of those who had fought or taken part in it. First, he went over the ground covered by the troops with the three Crow scouts White Man Runs Him, Goes Ahead, and Hairy Moccasin, and then again with Two Moons and a party of Cheyenne warriors. He also visited the Lakota country and interviewed Red Hawk, "whose recollection of the fight seemed to be particularly clear". Then, he went over the battlefield once more with the three Crow scouts, but also accompanied by General Charles Woodruff "as I particularly desired that the testimony of these men might be considered by an experienced army officer". Finally, Curtis visited the country of the Arikara

Arikara (), also known as Sahnish,

''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011)