Cultural Judaism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jewish culture is the culture of the

Defining secular culture among those who practice traditional Judaism is difficult, because the entire culture is, by definition, entwined with religious traditions: the idea of separate ethnic and religious identity is foreign to the Hebrew tradition of an ''" 'am yisrael"''. (This is particularly true for

Defining secular culture among those who practice traditional Judaism is difficult, because the entire culture is, by definition, entwined with religious traditions: the idea of separate ethnic and religious identity is foreign to the Hebrew tradition of an ''" 'am yisrael"''. (This is particularly true for

Jewish philosophy includes all philosophy carried out by Jews, or in relation to the religion of Judaism. The Jewish philosophy is extended over several main eras in

Jewish philosophy includes all philosophy carried out by Jews, or in relation to the religion of Judaism. The Jewish philosophy is extended over several main eras in  Between the Ancient era and the

Between the Ancient era and the  Jewish philosophers of the

Jewish philosophers of the

A range of moral and political views is evident early in the history of Judaism, that serves to partially explain the diversity that is apparent among secular Jews who are often influenced by moral beliefs that can be found in Jewish scripture, and traditions. In recent centuries, secular Jews in Europe and the Americas have tended towards the

A range of moral and political views is evident early in the history of Judaism, that serves to partially explain the diversity that is apparent among secular Jews who are often influenced by moral beliefs that can be found in Jewish scripture, and traditions. In recent centuries, secular Jews in Europe and the Americas have tended towards the

The

The

More remarkable contributors include

More remarkable contributors include

Literary and theatrical expressions of secular Jewish culture may be in specifically Jewish languages such as

Literary and theatrical expressions of secular Jewish culture may be in specifically Jewish languages such as

Jewish people

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

, from its formation in ancient times until the current age. Judaism itself is not simply a faith-based religion, but an orthopraxy

In the study of religion, orthopraxy is correct conduct, both ethical and liturgical, as opposed to faith or grace. Orthopraxy is in contrast with orthodoxy, which emphasizes correct belief. The word is a neoclassical compound— () meaning ...

and ethnoreligion, pertaining to deed, practice, and identity. Jewish culture covers many aspects, including religion and worldviews, literature, media, and cinema, art

Art is a diverse range of cultural activity centered around ''works'' utilizing creative or imaginative talents, which are expected to evoke a worthwhile experience, generally through an expression of emotional power, conceptual ideas, tec ...

and architecture, cuisine and traditional dress, attitudes to gender, marriage, family, social customs and lifestyles, music and dance. Some elements of Jewish culture come from within Judaism, others from the interaction of Jews with host populations, and others still from the inner social and cultural dynamics of the community. Before the 18th century, religion dominated virtually all aspects of Jewish life, and infused culture. Since the advent of secularization

In sociology, secularization () is a multilayered concept that generally denotes "a transition from a religious to a more worldly level." There are many types of secularization and most do not lead to atheism or irreligion, nor are they automatica ...

, wholly secular Jewish

Jewish secularism (Hebrew: יהדות חילונית) refers to secularism in a Jewish context, denoting the definition of Jewish identity with little or no attention given to its religious aspects. The concept of Jewish secularism first arose ...

culture emerged likewise.

History

There has not been a political unity of Jewish society since theunited monarchy

The Kingdom of Israel (Hebrew: מַמְלֶכֶת יִשְׂרָאֵל, ''Mamleḵeṯ Yīśrāʾēl'') was an Israelite kingdom that may have existed in the Southern Levant. According to the Deuteronomistic history in the Hebrew Bible ...

. Since then Israelite

Israelites were a Hebrew language, Hebrew-speaking ethnoreligious group, consisting of tribes that lived in Canaan during the Iron Age.

Modern scholarship describes the Israelites as emerging from indigenous Canaanites, Canaanite populations ...

populations were always geographically dispersed (see Jewish diaspora

The Jewish diaspora ( ), alternatively the dispersion ( ) or the exile ( ; ), consists of Jews who reside outside of the Land of Israel. Historically, it refers to the expansive scattering of the Israelites out of their homeland in the Southe ...

), so that by the 19th century, the Ashkenazi Jews

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; also known as Ashkenazic Jews or Ashkenazim) form a distinct subgroup of the Jewish diaspora, that emerged in the Holy Roman Empire around the end of the first millennium CE. They traditionally speak Yiddish, a language ...

were mainly located in Eastern and Central Europe; the Sephardi Jews

Sephardic Jews, also known as Sephardi Jews or Sephardim, and rarely as Iberian Peninsular Jews, are a Jewish diaspora population associated with the historic Jewish communities of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) and their descendant ...

were largely spread among various communities which lived in the Mediterranean region; Mizrahi Jews

Mizrahi Jews (), also known as ''Mizrahim'' () in plural and ''Mizrahi'' () in singular, and alternatively referred to as Oriental Jews or ''Edot HaMizrach'' (, ), are terms used in Israeli discourse to refer to a grouping of Jews, Jewish c ...

were primarily spread throughout Western Asia

West Asia (also called Western Asia or Southwest Asia) is the westernmost region of Asia. As defined by most academics, UN bodies and other institutions, the subregion consists of Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula, Iran, Mesopotamia, the Armenian ...

; and other populations of Jews lived in Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

, Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

, the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region spanning Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising parts of Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains, i ...

, and India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

. (See Jewish ethnic divisions

Jewish ethnic divisions refer to many distinctive communities within the world's Jewish population. Although "Jewish" is considered an ethnicity itself, there are distinct ethnic subdivisions among Jews, most of which are primarily the result of ...

.)

While there has been communication and traffic between these Jewish communities, many Sephardic exiles blended into the Ashkenazi communities which existed in Central Europe following the Spanish Inquisition

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition () was established in 1478 by the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile and lasted until 1834. It began toward the end of ...

; many Ashkenazim migrated to the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, giving rise to the characteristic Syrian-Jewish family name "Ashkenazi"; Iraqi-Jewish traders formed a distinct Jewish community in India; to some degree, many of these Jewish populations were cut off from the cultures which surrounded them by ghetto

A ghetto is a part of a city in which members of a minority group are concentrated, especially as a result of political, social, legal, religious, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished than other ...

ization, Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

laws of ''dhimma

' ( ', , collectively ''/'' "the people of the covenant") or () is a historical term for non-Muslims living in an Islamic state with legal protection. The word literally means "protected person", referring to the state's obligation under ''s ...

'', and the traditional discouragement of contact between Jews and members of polytheistic

Polytheism is the belief in or worship of more than one Deity, god. According to Oxford Reference, it is not easy to count gods, and so not always obvious whether an apparently polytheistic religion, such as Chinese folk religions, is really so, ...

populations by their religious leaders.

Medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

Jewish communities in Eastern Europe continued to display distinct cultural traits over the centuries. Despite the universalist leanings of the Enlightenment (and its echo within Judaism in the Haskalah

The ''Haskalah'' (; literally, "wisdom", "erudition" or "education"), often termed the Jewish Enlightenment, was an intellectual movement among the Jews of Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe, with a certain influence on those in Wester ...

movement), many Yiddish

Yiddish, historically Judeo-German, is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated in 9th-century Central Europe, and provided the nascent Ashkenazi community with a vernacular based on High German fused with ...

-speaking Jews in Eastern Europe continued to see themselves as forming a distinct national group — ''" 'am yehudi"'', from the Biblical Hebrew – but, adapting this idea to Enlightenment values, they assimilated the concept as that of an ethnic group whose identity did not depend on religion, which under Enlightenment thinking fell under a separate category.

Constantin Măciucă writes of the existence of "a differentiated but not isolated Jewish spirit" permeating the culture of Yiddish-speaking Jews. This was only intensified as the rise of Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

amplified the sense of national identity

National identity is a person's identity or sense of belonging to one or more states or one or more nations. It is the sense of "a nation as a cohesive whole, as represented by distinctive traditions, culture, and language".

National identity ...

across Europe generally. Thus, for example, members of the General Jewish Labour Bund

The General Jewish Labour Bund in Lithuania, Poland and Russia (), generally called The Bund (, cognate to , ) or the Jewish Labour Bund (), was a Jewish secularism, secular Jewish Socialism, socialist party initially formed in the Russian Empire ...

in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were generally non-religious, and one of the historical leaders of the Bund was the child of converts to Christianity, though not a practicing or believing Christian himself.

The Haskalah

The ''Haskalah'' (; literally, "wisdom", "erudition" or "education"), often termed the Jewish Enlightenment, was an intellectual movement among the Jews of Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe, with a certain influence on those in Wester ...

combined with the Jewish Emancipation

Jewish emancipation was the process in various nations in Europe of eliminating Jewish disabilities, to which European Jews were then subject, and the recognition of Jews as entitled to equality and citizenship rights. It included efforts withi ...

movement under way in Central and Western Europe to create an opportunity for Jews to enter secular society. At the same time, pogrom

A pogrom is a violent riot incited with the aim of Massacre, massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe late 19th- and early 20th-century Anti-Jewis ...

s in Eastern Europe provoked a surge of migration, in large part to the United States, where some 2 million Jewish immigrants resettled between 1880 and 1920.

By 1931, shortly before The Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

, 92% of the World's Jewish population was Ashkenazi in origin. Secularism originated in Europe as series of movements that militated for a new, heretofore unheard-of concept called "secular Judaism". For these reasons, much of what is thought of by English-speakers and, to a lesser extent, by non-English-speaking Europeans as "secular Jewish culture" is, in essence, the Jewish cultural movement that evolved in Central and Eastern Europe, and subsequently brought to North America by immigrants.

During the 1940s, the Holocaust uprooted and destroyed most of the Jewish communities living in much of Europe. This, in combination with the creation of the State of Israel and the consequent Jewish exodus from Arab lands, resulted in a further geographic shift.

Defining secular culture among those who practice traditional Judaism is difficult, because the entire culture is, by definition, entwined with religious traditions: the idea of separate ethnic and religious identity is foreign to the Hebrew tradition of an ''" 'am yisrael"''. (This is particularly true for

Defining secular culture among those who practice traditional Judaism is difficult, because the entire culture is, by definition, entwined with religious traditions: the idea of separate ethnic and religious identity is foreign to the Hebrew tradition of an ''" 'am yisrael"''. (This is particularly true for Orthodox Judaism

Orthodox Judaism is a collective term for the traditionalist branches of contemporary Judaism. Theologically, it is chiefly defined by regarding the Torah, both Torah, Written and Oral Torah, Oral, as literally revelation, revealed by God in Ju ...

.) Gary Tobin, head of the Institute for Jewish and Community Research, said of traditional Jewish culture:

''The dichotomy between religion and culture doesn't really exist. Every religious attribute is filled with culture; every cultural act filled with religiosity. Synagogues themselves are great centers of Jewish culture. After all, what is life really about? Food, relationships, enrichment ... So is Jewish life. So many of our traditions inherently contain aspects of culture. Look at thePassover Seder The Passover Seder is a ritual feast at the beginning of the Jewish holidays, Jewish holiday of Passover. It is conducted throughout the world on the eve of the 15th day of Nisan in the Hebrew calendar (i.e., at the start of the 15th; a Hebrew d ...— it's essentially great theater. Jewish education and religiosity bereft of culture is not as interesting.''

Yaakov Malkin

Yaakov Malkin (; 3 August 1926 – 21 July 2019) was an Israeli educator, literary critic, and professor emeritus in the Faculty of Arts at Tel Aviv University. He was active in several institutions that deal with both cultural and Humanistic Juda ...

, Professor of Aesthetics and Rhetoric at Tel Aviv University

Tel Aviv University (TAU) is a Public university, public research university in Tel Aviv, Israel. With over 30,000 students, it is the largest university in the country. Located in northwest Tel Aviv, the university is the center of teaching and ...

and the founder and academic director of Meitar College for Judaism as Culture in Jerusalem, writes:

''Today very many secular Jews take part in Jewish cultural activities, such as celebrating Jewish holidays as historical and nature festivals, imbued with new content and form, or marking life-cycle events such as birth, bar/bat mitzvah, marriage, and mourning in a secular fashion. They come together to study topics pertaining to Jewish culture and its relation to other cultures, in havurot, cultural associations, and secular synagogues, and they participate in public and political action coordinated by secular Jewish movements, such as the former movement to free Soviet Jews, and movements to combat pogroms, discrimination, and religious coercion. Jewish secularIn North America, the secular and cultural Jewish movements are divided into three umbrella organizations: thehumanistic Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry. The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...education inculcates universal moral values through classic Jewish and world literature and through organizations for social change that aspire to ideals of justice and charity.Malkin, Y. "Humanistic and secular Judaisms." ''Modern Judaism An Oxford Guide'', p. 107.''

Society for Humanistic Judaism

The Society for Humanistic Judaism (SHJ), founded by Rabbi Sherwin Wine in 1969, is an American 501(c)(3) organization and the central body of Humanistic Judaism, a philosophy that combines a Nontheism, non-theistic and Humanism, humanistic outloo ...

(SHJ), the Congress of Secular Jewish Organizations (CSJO), and The Workers Circle.

Philosophy and religion

Jewish philosophy includes all philosophy carried out by Jews, or in relation to the religion of Judaism. The Jewish philosophy is extended over several main eras in

Jewish philosophy includes all philosophy carried out by Jews, or in relation to the religion of Judaism. The Jewish philosophy is extended over several main eras in Jewish history

Jewish history is the history of the Jews, their Jewish peoplehood, nation, Judaism, religion, and Jewish culture, culture, as it developed and interacted with other peoples, religions and cultures.

Jews originated from the Israelites and H ...

, including the ancient and biblical era, medieval era and modern era (see Haskalah

The ''Haskalah'' (; literally, "wisdom", "erudition" or "education"), often termed the Jewish Enlightenment, was an intellectual movement among the Jews of Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe, with a certain influence on those in Wester ...

).

The ancient Jewish philosophy is expressed in the bible. According to Prof. Israel Efros, the principles of the Jewish philosophy start in the bible, where the foundations of the Jewish monotheistic beliefs can be found, such as the belief in one god

Monotheism is the belief that one God is the only, or at least the dominant deity.F. L. Cross, Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. A ...

, the separation of god and the world and nature (as opposed to Pantheism

Pantheism can refer to a number of philosophical and religious beliefs, such as the belief that the universe is God, or panentheism, the belief in a non-corporeal divine intelligence or God out of which the universe arisesAnn Thomson; Bodies ...

) and the creation of the world. Other biblical writings that associated with philosophy are Psalms

The Book of Psalms ( , ; ; ; ; , in Islam also called Zabur, ), also known as the Psalter, is the first book of the third section of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) called ('Writings'), and a book of the Old Testament.

The book is an anthology of B ...

that contains invitations to admire the wisdom of God through his works; from this, some scholars suggest, Judaism harbors a Philosophical under-current and Ecclesiastes

Ecclesiastes ( ) is one of the Ketuvim ('Writings') of the Hebrew Bible and part of the Wisdom literature of the Christian Old Testament. The title commonly used in English is a Latin transliteration of the Greek translation of the Hebrew word ...

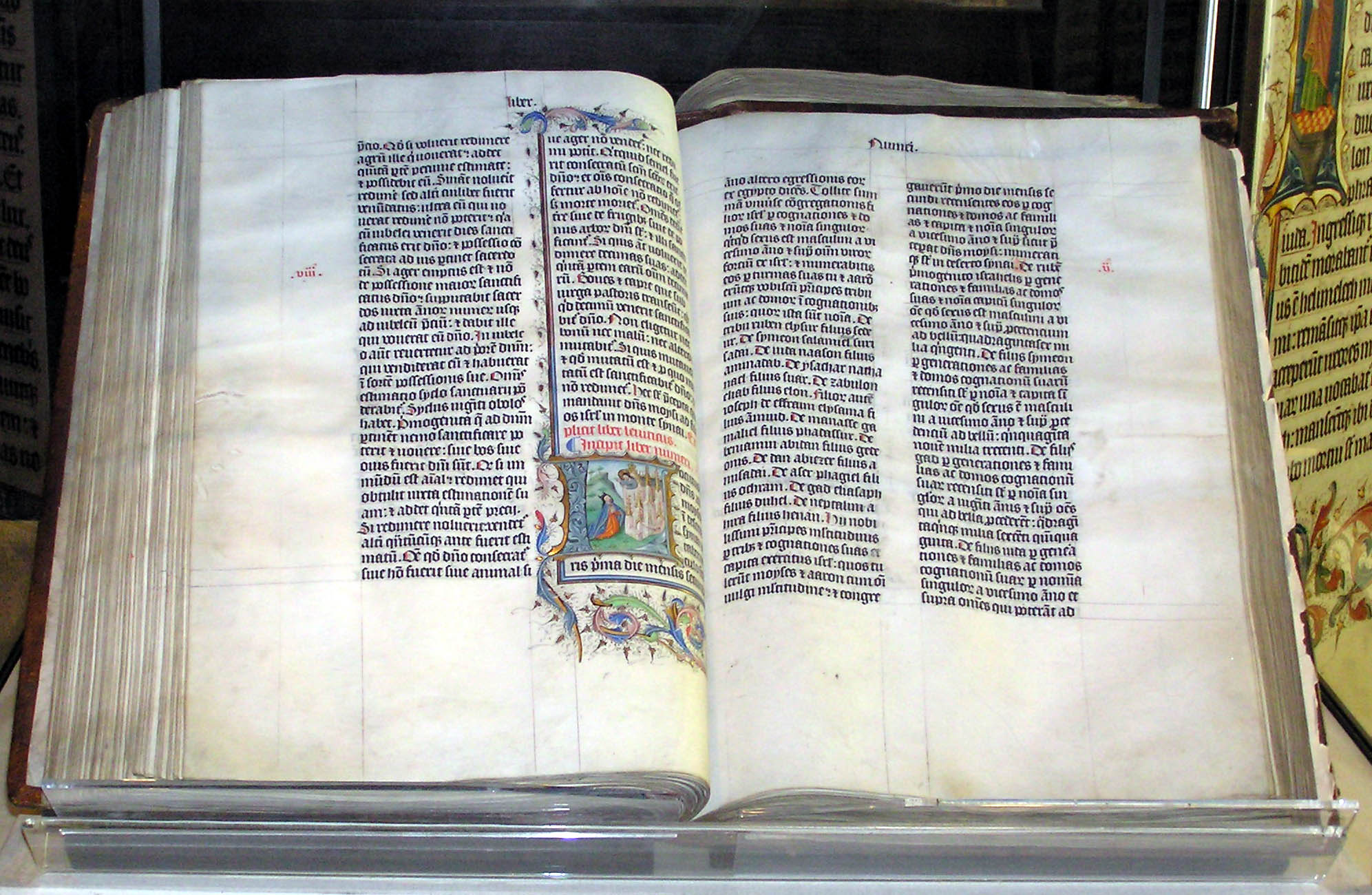

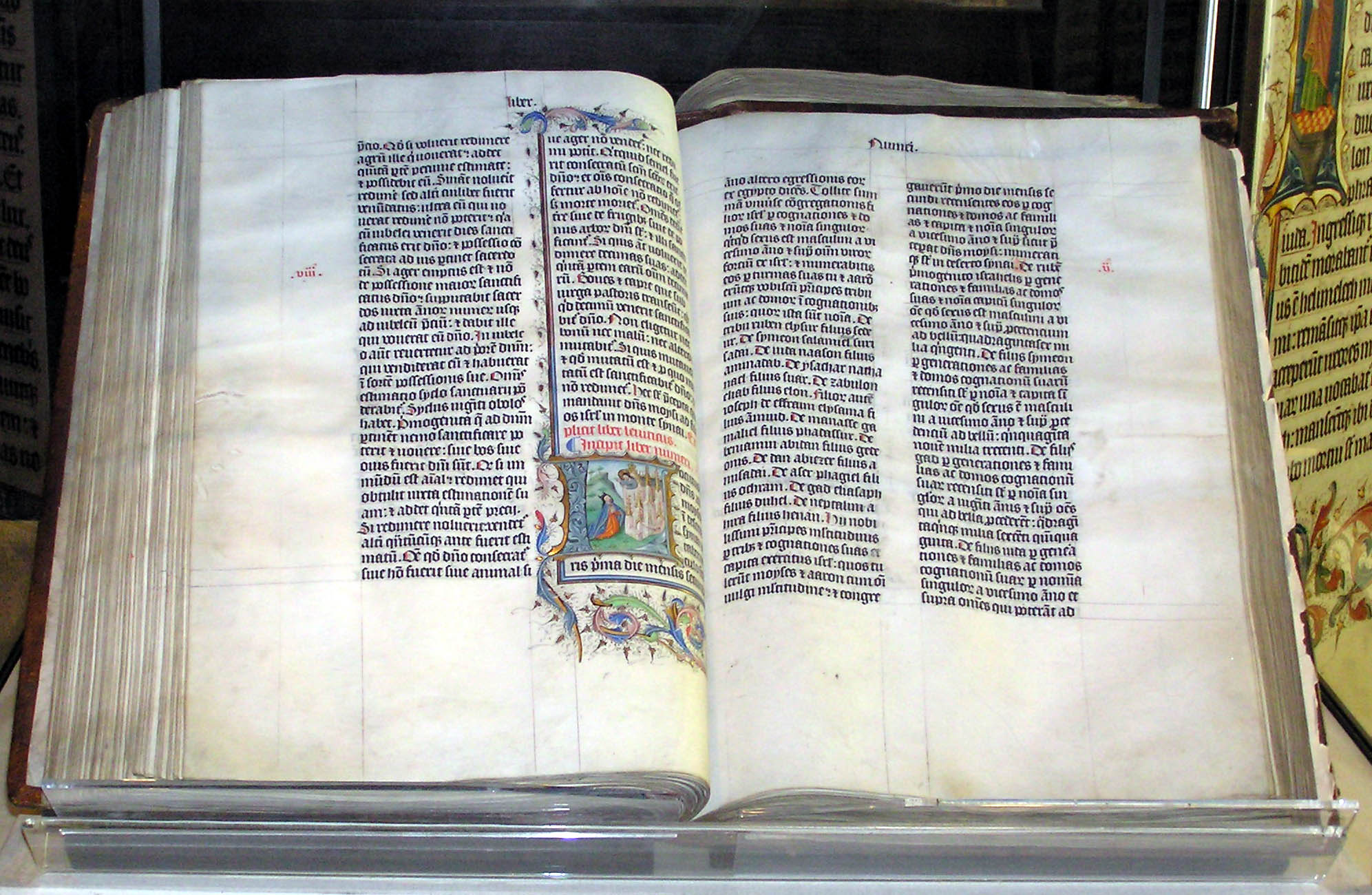

that is often considered to be the only genuine philosophical work in the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

. '' Deuterocanonical books The deuterocanonical books, meaning 'of, pertaining to, or constituting a second canon', collectively known as the Deuterocanon (DC), are certain books and passages considered to be canonical books of the Old Testament by the Catholic Chur ...

such as . '' Deuterocanonical books The deuterocanonical books, meaning 'of, pertaining to, or constituting a second canon', collectively known as the Deuterocanon (DC), are certain books and passages considered to be canonical books of the Old Testament by the Catholic Chur ...

Sirach

The Book of Sirach (), also known as The Wisdom of Jesus the Son of Sirach, The Wisdom of Jesus son of Eleazar, or Ecclesiasticus (), is a Jewish literary work originally written in Biblical Hebrew. The longest extant wisdom book from antiqui ...

and Book of Wisdom

The Book of Wisdom, or the Wisdom of Solomon, is a book written in Greek and most likely composed in Alexandria, Egypt. It is not part of the Hebrew Bible but is included in the Septuagint. Generally dated to the mid-first century BC, or to t ...

.

During the Hellenistic era

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the Roma ...

, Hellenistic Judaism

Hellenistic Judaism was a form of Judaism in classical antiquity that combined Jewish religious tradition with elements of Hellenistic culture and religion. Until the early Muslim conquests of the eastern Mediterranean, the main centers of Hellen ...

aspired to combine Jewish religious tradition with elements of Greek culture and philosophy. The philosopher Philo

Philo of Alexandria (; ; ; ), also called , was a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher who lived in Alexandria, in the Roman province of Egypt.

The only event in Philo's life that can be decisively dated is his representation of the Alexandrian J ...

used philosophical allegory to attempt to fuse and harmonize Greek philosophy

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC. Philosophy was used to make sense of the world using reason. It dealt with a wide variety of subjects, including astronomy, epistemology, mathematics, political philosophy, ethics, metaphysic ...

with Jewish philosophy. His work attempts to combine Plato and Moses into one philosophical system. He developed an allegoric approach of interpreting holy scriptures (the bible), in contrast to (old-fashioned) literally interpretation approaches. His allegorical exegesis

Exegesis ( ; from the Ancient Greek, Greek , from , "to lead out") is a critical explanation or interpretation (philosophy), interpretation of a text. The term is traditionally applied to the interpretation of Bible, Biblical works. In modern us ...

was important for several Christian Church Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical peri ...

and some scholars hold that his concept of the Logos

''Logos'' (, ; ) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric, as well as religion (notably Logos (Christianity), Christianity); among its connotations is that of a rationality, rational form of discourse that relies on inducti ...

as God's creative principle influenced early Christology

In Christianity, Christology is a branch of Christian theology, theology that concerns Jesus. Different denominations have different opinions on questions such as whether Jesus was human, divine, or both, and as a messiah what his role would b ...

. Other scholars, however, deny direct influence but say both Philo and Early Christianity

Early Christianity, otherwise called the Early Church or Paleo-Christianity, describes the History of Christianity, historical era of the Christianity, Christian religion up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325. Spread of Christianity, Christian ...

borrow from a common source.

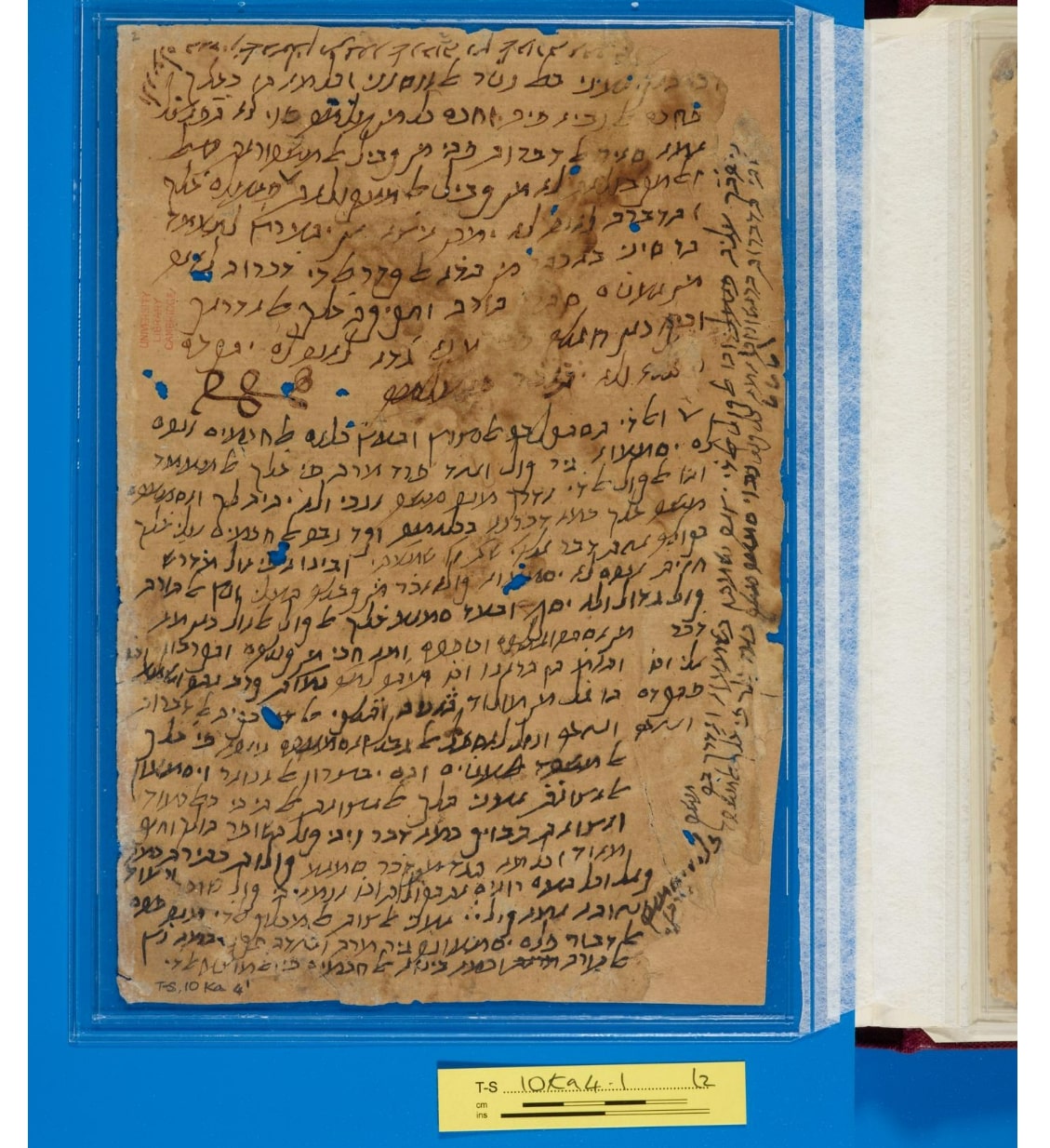

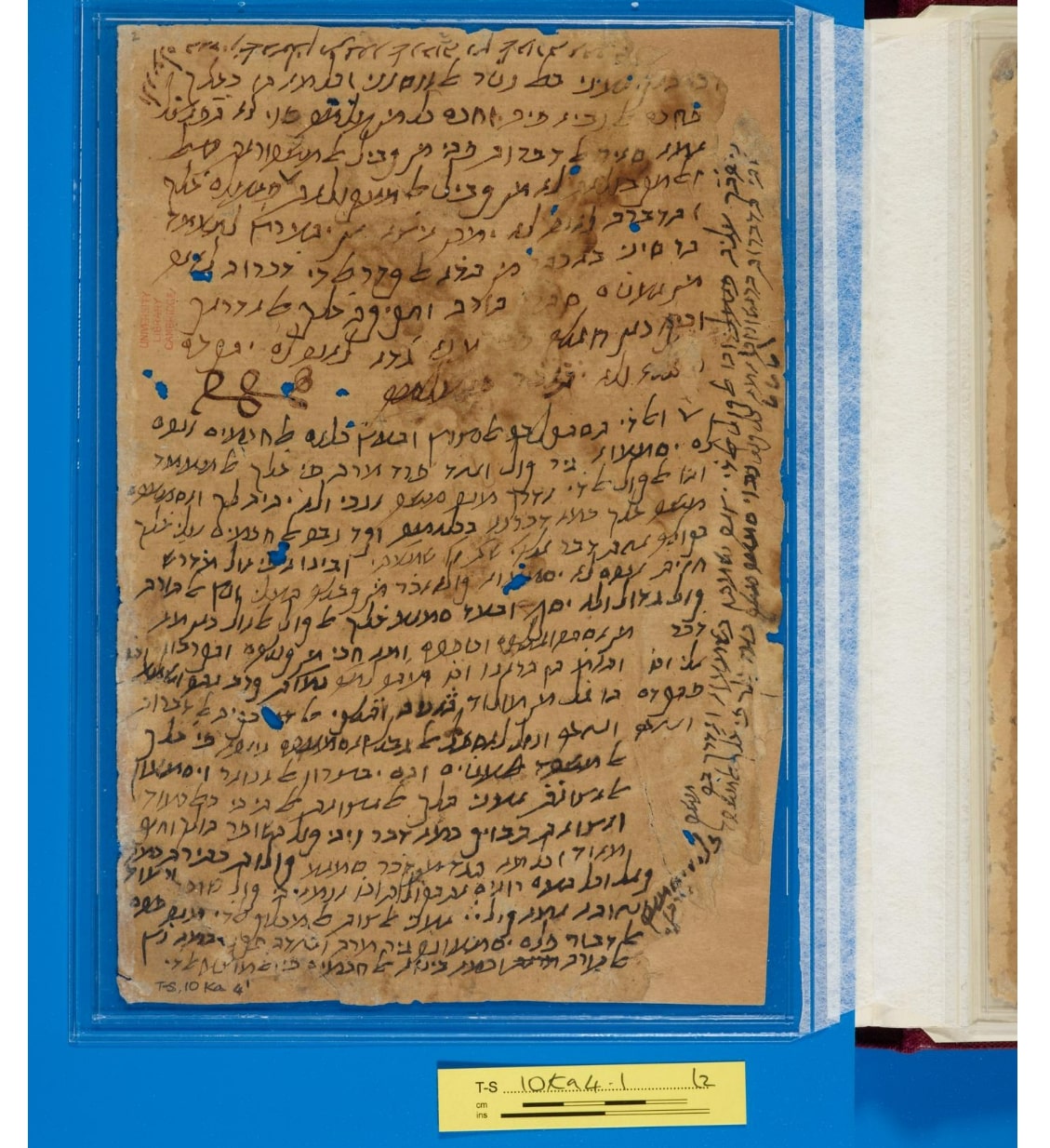

Between the Ancient era and the

Between the Ancient era and the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

most of the Jewish philosophy concentrated around the Rabbinic literature

Rabbinic literature, in its broadest sense, is the entire corpus of works authored by rabbis throughout Jewish history. The term typically refers to literature from the Talmudic era (70–640 CE), as opposed to medieval and modern rabbinic ...

that is expressed in the Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of Haskalah#Effects, modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

and Midrash

''Midrash'' (;"midrash"

. ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; or ''midrashot' ...

. In the 9th century . ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; or ''midrashot' ...

Saadia Gaon

Saʿadia ben Yosef Gaon (892–942) was a prominent rabbi, Geonim, gaon, Jews, Jewish philosopher, and exegesis, exegete who was active in the Abbasid Caliphate.

Saadia is the first important rabbinic figure to write extensively in Judeo-Arabic ...

wrote the text Emunoth ve-Deoth

''The Book of Beliefs and Opinions'' (; ) is a book written by Saadia Gaon (completed 933) which is the first systematic presentation and philosophic foundation of the dogmas of Judaism.

The work was originally in Judeo-Arabic in Hebrew letter ...

which is the first systematic presentation and philosophic foundation of the dogmas of Judaism. The Golden age of Jewish culture in Spain

The golden age of Jewish culture in Spain was a Muslim ruled era of Spain, with the state name of Al-Andalus, lasting 800 years, whose state lasted from 711 to 1492 A.D. This coincides with the Islamic Golden Age within Muslim ruled territorie ...

included many influential Jewish philosophers such as Moses ibn Ezra, Abraham ibn Ezra

Abraham ben Meir Ibn Ezra (, often abbreviated as ; ''Ibrāhim al-Mājid ibn Ezra''; also known as Abenezra or simply ibn Ezra, 1089 / 1092 – 27 January 1164 / 23 January 1167)''Jewish Encyclopedia''online; '' Chambers Biographical Dictionar ...

, Solomon ibn Gabirol

Solomon ibn Gabirol or Solomon ben Judah (, ; , ) was an 11th-century Jews, Jewish poet and Jewish philosopher, philosopher in the Neoplatonism, Neo-Platonic tradition in Al-Andalus. He published over a hundred poems, as well as works of biblical ...

, Yehuda Halevi, Isaac Abravanel, Nahmanides

Moses ben Nachman ( ''Mōše ben-Nāḥmān'', "Moses son of Nachman"; 1194–1270), commonly known as Nachmanides (; ''Nakhmanídēs''), and also referred to by the acronym Ramban (; ) and by the contemporary nickname Bonastruc ça Porta (; l ...

, Joseph Albo

Joseph Albo (; ) was a Jewish philosopher and rabbi who lived in Spain during the fifteenth century, known chiefly as the author of ''Sefer ha-Ikkarim'' ("Book of Principles"), the classic work on the fundamentals of Judaism.

Biography

Albo's bi ...

, Abraham ibn Daud

Abraham ibn Daud (; ) was a Spanish-Jewish astronomer, historian and philosopher; born in Córdoba, Spain about 1110; who was said to have been killed for his religious beliefs in Toledo, Spain, about 1180. He is sometimes known by the abbrevia ...

, Nissim of Gerona, Bahya ibn Paquda

Bahyā ibn Pāqudā (Bahya ben Joseph ibn Pakuda, Pekudah, Bakuda; , ), c. 1050–1120, was a Jewish philosopher and rabbi who lived in the Taifa of Zaragoza in al-Andalus (now Spain). He was one of two people now known as Rabbeinu Behaye, the o ...

, Abraham bar Hiyya, Joseph ibn Tzaddik, Hasdai Crescas

Hasdai ben Abraham Crescas (; ; c. 1340 in Barcelona – 1410/11 in Zaragoza) was a Spanish-Jewish philosopher and a renowned halakhist (teacher of Jewish law). Along with Maimonides ("Rambam"), Gersonides ("Ralbag"), and Joseph Albo, he is k ...

and Isaac ben Moses Arama. The most notable is Maimonides

Moses ben Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (, ) and also referred to by the Hebrew acronym Rambam (), was a Sephardic rabbi and Jewish philosophy, philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah schola ...

who is considered in the Jewish world to be a prominent philosopher and polymath in the Islamic and Western worlds. Outside of Spain, other philosophers are Natan'el al-Fayyumi, Elia del Medigo, Jedaiah ben Abraham Bedersi and Gersonides

Levi ben Gershon (1288 – 20 April 1344), better known by his Graecized name as Gersonides, or by his Latinized name Magister Leo Hebraeus, or in Hebrew by the abbreviation of first letters as ''RaLBaG'', was a medieval French Jewish philosoph ...

.

Jewish philosophers of the

Jewish philosophers of the modern era

The modern era or the modern period is considered the current historical period of human history. It was originally applied to the history of Europe and Western history for events that came after the Middle Ages, often from around the year 1500 ...

, mainly in Europe, include Baruch Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (24 November 163221 February 1677), also known under his Latinized pen name Benedictus de Spinoza, was a philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, who was born in the Dutch Republic. A forerunner of the Age of Enlightenmen ...

, founder of Spinozism, whose work included modern Rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the Epistemology, epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "the position that reason has precedence over other ways of acquiring knowledge", often in contrast to ot ...

and Biblical criticism

Modern Biblical criticism (as opposed to pre-Modern criticism) is the use of critical analysis to understand and explain the Bible without appealing to the supernatural. During the eighteenth century, when it began as ''historical-biblical c ...

and laid the groundwork for the 18th-century Enlightenment. His work has earned him recognition as one of Western philosophy

Western philosophy refers to the Philosophy, philosophical thought, traditions and works of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the Pre ...

's most important thinkers; others are Isaac Orobio de Castro, Tzvi Ashkenazi, David Nieto, Isaac Cardoso, Jacob Abendana, Uriel da Costa, Francisco Sanches and Moses Almosnino. A new era began in the 18th century with the thought of Moses Mendelssohn

Moses Mendelssohn (6 September 1729 – 4 January 1786) was a German-Jewish philosopher and theologian. His writings and ideas on Jews and the Jewish religion and identity were a central element in the development of the ''Haskalah'', or 'J ...

. Mendelssohn has been described as the "'third Moses', with whom begins a new era in Judaism", just as new eras began with Moses

In Abrahamic religions, Moses was the Hebrews, Hebrew prophet who led the Israelites out of slavery in the The Exodus, Exodus from ancient Egypt, Egypt. He is considered the most important Prophets in Judaism, prophet in Judaism and Samaritani ...

the prophet and with Moses Maimonides

Moses ben Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (, ) and also referred to by the Hebrew acronym Rambam (), was a Sephardic rabbi and philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah scholars of the Middle A ...

. Mendelssohn was a German Jewish philosopher to whose ideas the renaissance of European Jews, Haskalah

The ''Haskalah'' (; literally, "wisdom", "erudition" or "education"), often termed the Jewish Enlightenment, was an intellectual movement among the Jews of Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe, with a certain influence on those in Wester ...

(the Jewish Enlightenment) is indebted. He has been referred to as the father of Reform Judaism, though Reform spokesmen have been "resistant to claim him as their spiritual father". Mendelssohn came to be regarded as a leading cultural figure of his time by both Germans

Germans (, ) are the natives or inhabitants of Germany, or sometimes more broadly any people who are of German descent or native speakers of the German language. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, constitution of Germany, imple ...

and Jews. The Jewish Enlightenment philosophy included Menachem Mendel Lefin, Salomon Maimon and Isaac Satanow. The next 19th century

The 19th century began on 1 January 1801 (represented by the Roman numerals MDCCCI), and ended on 31 December 1900 (MCM). It was the 9th century of the 2nd millennium. It was characterized by vast social upheaval. Slavery was Abolitionism, ...

comprised both secular and religious philosophy and included philosophers such as Elijah Benamozegh, Hermann Cohen

Hermann Cohen (; ; 4 July 1842 – 4 April 1918) was a German philosopher, one of the founders of the Marburg school of neo-Kantianism, and he is often held to be "probably the most important Jewish philosopher of the nineteenth century".

Bio ...

, Moses Hess

Moses (Moritz) Hess (21 January 1812 – 6 April 1875) was a German-Jewish philosopher, early socialist and Zionist thinker. His theories led to disagreements with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. He is considered a pioneer of Labor Zionism.

Bi ...

, Samson Raphael Hirsch

Samson Raphael Hirsch (; June 20, 1808 – December 31, 1888) was a German Orthodox rabbi best known as the intellectual founder of the '' Torah im Derech Eretz'' school of contemporary Orthodox Judaism. Occasionally termed ''neo-Orthodoxy'', hi ...

, Samuel Hirsch, Nachman Krochmal, Samuel David Luzzatto, and Nachman of Breslov

Nachman of Breslov ( ''Rabbī'' ''Naḥmān mīBreslev''), also known as Rabbi Nachman of Breslev, Rabbi Nachman miBreslev, Reb Nachman of Bratslav, Reb Nachman Breslover ( ''Rebe Nakhmen Breslover''), and Nachman from Uman (April 4, 1772 – O ...

founder of Breslov. The 20th century included the notable philosophers Jacques Derrida

Jacques Derrida (; ; born Jackie Élie Derrida;Peeters (2013), pp. 12–13. See also 15 July 1930 – 9 October 2004) was a French Algerian philosopher. He developed the philosophy of deconstruction, which he utilized in a number of his texts, ...

, Karl Popper

Sir Karl Raimund Popper (28 July 1902 – 17 September 1994) was an Austrian–British philosopher, academic and social commentator. One of the 20th century's most influential philosophers of science, Popper is known for his rejection of the ...

, Emmanuel Levinas

Emmanuel Levinas (born Emanuelis Levinas ; ; 12 January 1906 – 25 December 1995) was a French philosopher of Lithuanian Jewish ancestry who is known for his work within Jewish philosophy, existentialism, and phenomenology, focusing on the rel ...

, Claude Lévi-Strauss

Claude Lévi-Strauss ( ; ; 28 November 1908 – 30 October 2009) was a Belgian-born French anthropologist and ethnologist whose work was key in the development of the theories of structuralism and structural anthropology. He held the chair o ...

, Hilary Putnam

Hilary Whitehall Putnam (; July 31, 1926 – March 13, 2016) was an American philosopher, mathematician, computer scientist, and figure in analytic philosophy in the second half of the 20th century. He contributed to the studies of philosophy of ...

, Alfred Tarski

Alfred Tarski (; ; born Alfred Teitelbaum;School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews ''School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews''. January 14, 1901 – October 26, 1983) was a Polish-American logician ...

, Ludwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein ( ; ; 26 April 1889 – 29 April 1951) was an Austrian philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language.

From 1929 to 1947, Witt ...

, A. J. Ayer, Walter Benjamin

Walter Bendix Schönflies Benjamin ( ; ; 15 July 1892 – 26 September 1940) was a German-Jewish philosopher, cultural critic, media theorist, and essayist. An eclectic thinker who combined elements of German idealism, Jewish mysticism, Western M ...

, Raymond Aron

Raymond Claude Ferdinand Aron (; ; 14 March 1905 – 17 October 1983) was a French philosopher, sociologist, political scientist, historian and journalist, one of France's most prominent thinkers of the 20th century.

Aron is best known for his ...

, Theodor W. Adorno

Theodor W. Adorno ( ; ; born Theodor Ludwig Wiesengrund; 11 September 1903 – 6 August 1969) was a German philosopher, musicologist, and social theorist. He was a leading member of the Frankfurt School of critical theory, whose work has com ...

, Isaiah Berlin

Sir Isaiah Berlin (6 June 1909 – 5 November 1997) was a Russian-British social and political theorist, philosopher, and historian of ideas. Although he became increasingly averse to writing for publication, his improvised lectures and talks ...

and Henri Bergson

Henri-Louis Bergson (; ; 18 October 1859 – 4 January 1941) was a French philosopher who was influential in the traditions of analytic philosophy and continental philosophy, especially during the first half of the 20th century until the S ...

.

Education and politics

A range of moral and political views is evident early in the history of Judaism, that serves to partially explain the diversity that is apparent among secular Jews who are often influenced by moral beliefs that can be found in Jewish scripture, and traditions. In recent centuries, secular Jews in Europe and the Americas have tended towards the

A range of moral and political views is evident early in the history of Judaism, that serves to partially explain the diversity that is apparent among secular Jews who are often influenced by moral beliefs that can be found in Jewish scripture, and traditions. In recent centuries, secular Jews in Europe and the Americas have tended towards the political left

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy either as a whole or of certain social hierarchies. Left-wing politi ...

, and played key roles in the birth of the 19th century's labor movement

The labour movement is the collective organisation of working people to further their shared political and economic interests. It consists of the trade union or labour union movement, as well as political parties of labour. It can be considere ...

and socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

. The biographies of women like Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born Anarchism, anarchist revolutionary, political activist, and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europ ...

and Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt (born Johanna Arendt; 14 October 1906 – 4 December 1975) was a German and American historian and philosopher. She was one of the most influential political theory, political theorists of the twentieth century.

Her work ...

embody complicated relationships between politics, Judaism and feminism. While Diaspora Jews have also been represented on the conservative side of the political spectrum, even politically conservative Jews have tended to support pluralism more consistently than many other elements of the political right

Right-wing politics is the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position based on natural law, economics, authority, property, ...

. Some scholars attribute this to the fact that Jews are not expected to proselytize, derived from Halakha

''Halakha'' ( ; , ), also Romanization of Hebrew, transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Judaism, Jewish religious laws that are derived from the Torah, Written and Oral Torah. ''Halakha'' is ...

. This lack of a universalizing religion is combined with the fact that most Jews live as minorities in diaspora countries, and that no central Jewish religious authority has existed since 363 CE. Jews value education, and the value of education is strongly embedded in Jewish culture.

Economic activity

In theMiddle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, European laws prevented Jews from owning land and gave them important incentives to go into professions that non-Jewish Europeans were unwilling to undertake. During the medieval period, there was a very strong social stigma

Stigma, originally referring to the visible marking of people considered inferior, has evolved to mean a negative perception or sense of disapproval that a society places on a group or individual based on certain characteristics such as their ...

against lending money and charging interest among the Christian majority. In most of Europe until the late 18th century, and in some places to an even later date, Jews were prohibited by Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

governments (and others) from owning land. On the other hand, the Church, because of a number of Bible verses (e.g., Leviticus 25:36) forbidding usury

Usury () is the practice of making loans that are seen as unfairly enriching the lender. The term may be used in a moral sense—condemning taking advantage of others' misfortunes—or in a legal sense, where an interest rate is charged in e ...

, declared that charging any interest was against the divine law, and this prevented any mercantile use of capital

Capital and its variations may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** Capital region, a metropolitan region containing the capital

** List of national capitals

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter

Econom ...

by pious Christians. As the Canon law

Canon law (from , , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical jurisdiction, ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its membe ...

did not apply to Jews, they were not liable to the ecclesiastical punishments which were placed upon usurers by the popes. Christian rulers gradually saw the advantage of having a class of men like the Jews who could supply capital for their use without being liable to excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to deprive, suspend, or limit membership in a religious community or to restrict certain rights within it, in particular those of being in Koinonia, communion with other members o ...

, and so the money trade of western Europe by this means fell into the hands of the Jews.

However, in almost every instance where large amounts were acquired by Jews through banking transactions the property thus acquired fell either during their life or upon their death into the hands of the king. This happened to Aaron of Lincoln in England, Ezmel de Ablitas in Navarre, Heliot de Vesoul in Provence, Benveniste de Porta in Aragon, etc. It was often for this reason that kings supported the Jews, and even objected to them becoming Christians (because in that case their fortunes earned by usury could not be seized by the crown after their deaths). Thus, both in England and in France the kings demanded to be compensated by the church for every Jew converted. This type of royal trickery was one factor in creating the stereotypical Jewish role of banker and/or merchant.

As a modern system of capital

Capital and its variations may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** Capital region, a metropolitan region containing the capital

** List of national capitals

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter

Econom ...

began to develop, loans became necessary for commerce and industry. Jews were able to gain a foothold in the new field of finance by providing these services: as non-Catholics, they were not bound by the ecclesiastical prohibition against "usury"; and in terms of Judaism itself, Hillel had long ago re-interpreted the Torah's ban on charging interest, allowing interest when it is needed to make a living.

Science and technology

The strong Jewish tradition of religious scholarship often left Jews well prepared for secular scholarship. In some times and places, this was countered by banning Jews from studying at universities, or admitting them only in limited numbers (seeJewish quota

A Jewish quota was a discriminatory racial quota designed to limit or deny access for Jews to various institutions. Such quotas were widespread in the 19th and 20th centuries in developed countries and frequently present in higher education, o ...

). Over the centuries, Jews have been poorly represented among land-holding classes, but far better represented in academia, professions, finance, commerce and many scientific fields. The strong representation of Jews in science and academia is evidenced by the fact that 193 persons known to be Jews or of Jewish ancestry have been awarded the Nobel Prize, accounting for 22% of all individual recipients worldwide between 1901 and 2014. Of whom, 26% in physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

, 22% in chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

and 27% in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine () is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute, Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single ...

. In the fields of mathematics and computer science

Computer science is the study of computation, information, and automation. Computer science spans Theoretical computer science, theoretical disciplines (such as algorithms, theory of computation, and information theory) to Applied science, ...

, 31% of Turing Award

The ACM A. M. Turing Award is an annual prize given by the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) for contributions of lasting and major technical importance to computer science. It is generally recognized as the highest distinction in the fi ...

recipients and 27% of Fields Medal

The Fields Medal is a prize awarded to two, three, or four mathematicians under 40 years of age at the International Congress of Mathematicians, International Congress of the International Mathematical Union (IMU), a meeting that takes place e ...

in mathematics were or are Jewish.

The early Jewish activity in science can be found in the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

. '' physical world The universe is all of space and time and their contents. It comprises all of existence, any fundamental interaction, physical process and physical constant, and therefore all forms of matter and energy, and the structures they form, from s ...

. Biblical cosmology provides sporadic glimpses that may be stitched together to form a Biblical impression of the physical universe. There have been comparisons between the Bible, with passages such as from the . '' physical world The universe is all of space and time and their contents. It comprises all of existence, any fundamental interaction, physical process and physical constant, and therefore all forms of matter and energy, and the structures they form, from s ...

Genesis creation narrative

The Genesis creation narrative is the creation myth of both Judaism and Christianity, told in the book of Genesis chapters 1 and 2. While the Jewish and Christian tradition is that the account is one comprehensive story, modern scholars of ...

, and the astronomy of classical antiquity more generally. The Bible also contains various cleansing rituals. One suggested ritual, for example, deals with the proper procedure for cleansing a leper

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease (HD), is a long-term infection by the bacteria '' Mycobacterium leprae'' or '' Mycobacterium lepromatosis''. Infection can lead to damage of the nerves, respiratory tract, skin, and eyes. This nerve da ...

(). It is a fairly elaborate process, which is to be performed after a leper was already healed of leprosy (), involving extensive cleansing and personal hygiene, but also includes sacrificing a bird and lambs with the addition of using their blood to symbolize that the afflicted has been cleansed.

The Torah

The Torah ( , "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The Torah is also known as the Pentateuch () ...

proscribes Intercropping

Intercropping is a multiple cropping practice that involves the cultivation of two or more crops simultaneously on the same field, a form of polyculture. The most common goal of intercropping is to produce a greater yield on a given piece of land ...

(Lev. 19:19, Deut 22:9), a practice often associated with sustainable agriculture and organic farming in modern agricultural science

Agricultural science (or agriscience for short) is a broad multidisciplinary field of biology that encompasses the parts of exact, natural, economic and social sciences that are used in the practice and understanding of agriculture. Professio ...

. The Mosaic code has provisions concerning the conservation of natural resources, such as trees () and birds ().

During Medieval era astronomy was a primary field among Jewish scholars and was widely studied and practiced. Prominent astronomers included Abraham Zacuto

Abraham Zacuto (, ; 12 August 1452 – ) was a Sephardic Jewish astronomer, astrologer, mathematician, rabbi and historian. Born in Castile, he served as Royal Astronomer to King John II of Portugal before fleeing to Tunis.

His astrolabe of cop ...

who published in 1478 his Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

book ''Ha-hibbur ha-gadol''"Zacuto, Abraham" in Glick, T., S.J. Livesy and F. Williams, editors, (2005) ''Medieval science, technology, and medicine: an encyclopedia'', New York Routledge. where he wrote about the Solar System

The Solar SystemCapitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Sola ...

, charting the positions of the Sun, Moon and five planets. His work served Portugal's exploration journeys and was used by Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama ( , ; – 24 December 1524), was a Portuguese explorer and nobleman who was the Portuguese discovery of the sea route to India, first European to reach India by sea.

Da Gama's first voyage (1497–1499) was the first to link ...

and also by Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

. The lunar crater

Lunar craters are impact craters on Earth's Moon. The Moon's surface has many craters, all of which were formed by impacts. The International Astronomical Union currently recognizes 9,137 craters, of which 1,675 have been dated.

History

The wo ...

'' Zagut'' is named after Zacuto's name. The mathematician and astronomer Abraham bar Hiyya Ha-Nasi authored the first European book to include the full solution to the quadratic equation x2 – ax + b = 0, and influenced the work of Leonardo Fibonacci. Bar Hiyya proved by the method of indivisibles

In geometry, Cavalieri's principle, a modern implementation of the method of indivisibles, named after Bonaventura Cavalieri, is as follows:

* 2-dimensional case: Suppose two regions in a plane are included between two parallel lines in that pl ...

the following equation for any circle: S = LxR/2, where S is the surface area, L is the circumference length and R is radius.

Garcia de Orta

Garcia de Orta (or Garcia d'Orta; 1501–1568) was a Portuguese physician, herbalist, and naturalist, who worked primarily in Goa and Bombay in Portuguese India.

A pioneer of tropical medicine, pharmacognosy, and ethnobotany, Garcia used an e ...

, Portuguese Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

Jewish physician, was a pioneer of Tropical medicine

Tropical medicine is an interdisciplinary branch of medicine that deals with health issues that occur uniquely, are more widespread, or are more difficult to control in tropical and subtropical regions.

Physicians in this field diagnose and tr ...

. He published his work Colóquios dos simples e drogas da India

''Colloquies on the Simples and Drugs of India'' () is a work published in Goa on 10 April 1563 by Garcia de Orta, a Portuguese Jewish physician and naturalist, a pioneer of tropical medicine.

Outline of the ''Colóquios''

Garcia de Orta's wo ...

in 1563, which deals with a series of substances, many of them unknown or the subject of confusion and misinformation in Europe at this period. He was the first European to describe Asiatic tropical diseases, notably cholera; he performed an autopsy on a cholera victim, the first recorded autopsy in India. Bonet de Lattes known chiefly as the inventor of an astronomical ring-dial by means of which solar and stellar altitudes can be measured and the time determined with great precision by night as well as by day. Other related personalities are Abraham ibn Ezra

Abraham ben Meir Ibn Ezra (, often abbreviated as ; ''Ibrāhim al-Mājid ibn Ezra''; also known as Abenezra or simply ibn Ezra, 1089 / 1092 – 27 January 1164 / 23 January 1167)''Jewish Encyclopedia''online; '' Chambers Biographical Dictionar ...

, whose the Moon crater '' Abenezra'' named after, David Gans, Judah ibn Verga, Mashallah ibn Athari an astronomer, The crater '' Messala'' on the Moon is named after him.

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

was a German-born theoretical physicist and is considered one of the most prominent scientists in history, often regarded as the "father of modern physics". His revolutionary work on the relativity theory

The theory of relativity usually encompasses two interrelated physics theories by Albert Einstein: special relativity and general relativity, proposed and published in 1905 and 1915, respectively. Special relativity applies to all physical phe ...

transformed theoretical physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

and astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

during the 20th century. When first published, relativity superseded a 200-year-old theory of mechanics created primarily by Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

. In the field of physics, relativity improved the science of elementary particles

In particle physics, an elementary particle or fundamental particle is a subatomic particle that is not composed of other particles. The Standard Model presently recognizes seventeen distinct particles—twelve fermions and five bosons. As a con ...

and their fundamental interactions, along with ushering in the nuclear age. With relativity, cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe, the cosmos. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', with the meaning of "a speaking of the wo ...

and astrophysics

Astrophysics is a science that employs the methods and principles of physics and chemistry in the study of astronomical objects and phenomena. As one of the founders of the discipline, James Keeler, said, astrophysics "seeks to ascertain the ...

predicted extraordinary astronomical phenomena such as neutron stars

A neutron star is the gravitationally collapsed core of a massive supergiant star. It results from the supernova explosion of a massive star—combined with gravitational collapse—that compresses the core past white dwarf star density to th ...

, black holes

A black hole is a massive, compact astronomical object so dense that its gravity prevents anything from escaping, even light. Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity predicts that a sufficiently compact mass will form a black hole. Th ...

, and gravitational waves

Gravitational waves are oscillations of the gravitational field that travel through space at the speed of light; they are generated by the relative motion of gravitating masses. They were proposed by Oliver Heaviside in 1893 and then later by H ...

.

Einstein formulated the well-known Mass–energy equivalence

In physics, mass–energy equivalence is the relationship between mass and energy in a system's rest frame. The two differ only by a multiplicative constant and the units of measurement. The principle is described by the physicist Albert Einstei ...

, ''E = mc2'', and explained the photoelectric effect

The photoelectric effect is the emission of electrons from a material caused by electromagnetic radiation such as ultraviolet light. Electrons emitted in this manner are called photoelectrons. The phenomenon is studied in condensed matter physi ...

. His work also effected and influenced a large variety of fields of physics including the Big Bang

The Big Bang is a physical theory that describes how the universe expanded from an initial state of high density and temperature. Various cosmological models based on the Big Bang concept explain a broad range of phenomena, including th ...

theory (Einstein's General relativity

General relativity, also known as the general theory of relativity, and as Einstein's theory of gravity, is the differential geometry, geometric theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1915 and is the current description of grav ...

influenced Georges Lemaître

Georges Henri Joseph Édouard Lemaître ( ; ; 17 July 1894 – 20 June 1966) was a Belgian Catholic priest, theoretical physicist, and mathematician who made major contributions to cosmology and astrophysics. He was the first to argue that the ...

), Quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Addison-Wesley, 1989, It is ...

and nuclear energy

Nuclear energy may refer to:

*Nuclear power, the use of sustained nuclear fission or nuclear fusion to generate heat and electricity

*Nuclear binding energy, the energy needed to fuse or split a nucleus of an atom

*Nuclear potential energy, the pot ...

.

The

The Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

was a research and development project that produced the first atomic bombs during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

and many Jewish scientists had a significant role in the project. The theoretical physicist

Theoretical physics is a branch of physics that employs mathematical models and abstractions of physical objects and systems to rationalize, explain, and predict natural phenomena. This is in contrast to experimental physics, which uses experi ...

Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (born Julius Robert Oppenheimer ; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist who served as the director of the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory during World War II. He is often ...

, often considered the "father of the atomic bomb", was chosen to direct the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory (often shortened as Los Alamos and LANL) is one of the sixteen research and development Laboratory, laboratories of the United States Department of Energy National Laboratories, United States Department of Energy ...

in 1942. The physicist Leó Szilárd, that conceived the nuclear chain reaction

In nuclear physics, a nuclear chain reaction occurs when one single nuclear reaction causes an average of one or more subsequent nuclear reactions, thus leading to the possibility of a self-propagating series or "positive feedback loop" of thes ...

; Edward Teller

Edward Teller (; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian and American Theoretical physics, theoretical physicist and chemical engineer who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" and one of the creators of ...

, ''"the father of the hydrogen bomb

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H-bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lo ...

''" and Stanislaw Ulam Stanislav and variants may refer to:

People

*Stanislav (given name), a Slavic given name with many spelling variations (Stanislaus, Stanislas, Stanisław, etc.)

Places

* Stanislav, Kherson Oblast, a coastal village in Ukraine

* Stanislaus County, ...

; Eugene Wigner

Eugene Paul Wigner (, ; November 17, 1902 – January 1, 1995) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who also contributed to mathematical physics. He received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1963 "for his contributions to the theory of th ...

contributed to theory of Atomic nucleus

The atomic nucleus is the small, dense region consisting of protons and neutrons at the center of an atom, discovered in 1911 by Ernest Rutherford at the Department_of_Physics_and_Astronomy,_University_of_Manchester , University of Manchester ...

and Elementary particle

In particle physics, an elementary particle or fundamental particle is a subatomic particle that is not composed of other particles. The Standard Model presently recognizes seventeen distinct particles—twelve fermions and five bosons. As a c ...

; Hans Bethe

Hans Albrecht Eduard Bethe (; ; July 2, 1906 – March 6, 2005) was a German-American physicist who made major contributions to nuclear physics, astrophysics, quantum electrodynamics and solid-state physics, and received the Nobel Prize in Physi ...

whose work included Stellar nucleosynthesis

In astrophysics, stellar nucleosynthesis is the creation of chemical elements by nuclear fusion reactions within stars. Stellar nucleosynthesis has occurred since the original creation of hydrogen, helium and lithium during the Big Bang. As a ...

and was head of the Theoretical Division at the secret Los Alamos laboratory; Richard Feynman

Richard Phillips Feynman (; May 11, 1918 – February 15, 1988) was an American theoretical physicist. He is best known for his work in the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics, the theory of quantum electrodynamics, the physics of t ...

, Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (, ; ; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish theoretical physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and old quantum theory, quantum theory, for which he received the No ...

, Victor Weisskopf

Victor Frederick "Viki" Weisskopf (also spelled Viktor; September 19, 1908 – April 22, 2002) was an Austrian-born American theoretical physicist. He did postdoctoral work with Werner Heisenberg, Erwin Schrödinger, Wolfgang Pauli, and Niels Boh ...

and Joseph Rotblat.

The mathematician and physicist Alexander Friedmann pioneered the theory that universe was expanding governed by a set of equations he developed now known as the Friedmann equations

The Friedmann equations, also known as the Friedmann–Lemaître (FL) equations, are a set of equations in physical cosmology that govern cosmic expansion in homogeneous and isotropic models of the universe within the context of general relativi ...

. Arno Allan Penzias

Arno Allan Penzias (; April 26, 1933 – January 22, 2024) was an American physicist and radio astronomer. Along with Robert Woodrow Wilson, he discovered the cosmic microwave background radiation, for which he shared the Nobel Prize in Phys ...

, the physicist and radio astronomer co-discoverer of the cosmic microwave background

The cosmic microwave background (CMB, CMBR), or relic radiation, is microwave radiation that fills all space in the observable universe. With a standard optical telescope, the background space between stars and galaxies is almost completely dar ...

radiation, which helped establish the Big Bang

The Big Bang is a physical theory that describes how the universe expanded from an initial state of high density and temperature. Various cosmological models based on the Big Bang concept explain a broad range of phenomena, including th ...

theory, the scientists Robert Herman and Ralph Alpher had also worked on that field. In quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Addison-Wesley, 1989, It is ...

Jewish role was significant as well and many of most influential figures and pioneers of the theory were Jewish: Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (, ; ; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish theoretical physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and old quantum theory, quantum theory, for which he received the No ...

and his work on the atom

Atoms are the basic particles of the chemical elements. An atom consists of a atomic nucleus, nucleus of protons and generally neutrons, surrounded by an electromagnetically bound swarm of electrons. The chemical elements are distinguished fr ...

structure, Max Born

Max Born (; 11 December 1882 – 5 January 1970) was a German-British theoretical physicist who was instrumental in the development of quantum mechanics. He also made contributions to solid-state physics and optics, and supervised the work of a ...

(Schrödinger equation

The Schrödinger equation is a partial differential equation that governs the wave function of a non-relativistic quantum-mechanical system. Its discovery was a significant landmark in the development of quantum mechanics. It is named after E ...

), Wolfgang Pauli

Wolfgang Ernst Pauli ( ; ; 25 April 1900 – 15 December 1958) was an Austrian theoretical physicist and a pioneer of quantum mechanics. In 1945, after having been nominated by Albert Einstein, Pauli received the Nobel Prize in Physics "for the ...

, Richard Feynman

Richard Phillips Feynman (; May 11, 1918 – February 15, 1988) was an American theoretical physicist. He is best known for his work in the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics, the theory of quantum electrodynamics, the physics of t ...

(Quantum chromodynamics

In theoretical physics, quantum chromodynamics (QCD) is the study of the strong interaction between quarks mediated by gluons. Quarks are fundamental particles that make up composite hadrons such as the proton, neutron and pion. QCD is a type of ...

), Fritz London

Fritz Wolfgang London (March 7, 1900 – March 30, 1954) was a German born physicist and professor at Duke University. His fundamental contributions to the theories of chemical bonding and of intermolecular forces (London dispersion forces) are to ...

work on London dispersion force

London dispersion forces (LDF, also known as dispersion forces, London forces, instantaneous dipole–induced dipole forces, fluctuating induced dipole bonds or loosely as van der Waals forces) are a type of intermolecular force acting between at ...

and London equations

The London equations, developed by brothers Fritz and Heinz London in 1935, are constitutive relations for a superconductor relating its superconducting current to electromagnetic fields in and around it. Whereas Ohm's law is the simplest con ...

, Walter Heitler

Walter Heinrich Heitler (; 2 January 1904 – 15 November 1981) was a German physicist who made contributions to quantum electrodynamics and quantum field theory. He brought chemistry under quantum mechanics through his theory of valence bondi ...

and Julian Schwinger

Julian Seymour Schwinger (; February 12, 1918 – July 16, 1994) was a Nobel Prize-winning American theoretical physicist. He is best known for his work on quantum electrodynamics (QED), in particular for developing a relativistically invariant ...

work on Quantum electrodynamics

In particle physics, quantum electrodynamics (QED) is the Theory of relativity, relativistic quantum field theory of electrodynamics. In essence, it describes how light and matter interact and is the first theory where full agreement between quant ...

, Asher Peres

Asher Peres (; January 30, 1934 – January 1, 2005) was an Israeli physicist. Peres is best known for his work relating quantum mechanics and information theory. He helped to develop the Peres–Horodecki criterion for quantum entanglement, as w ...

a pioneer in Quantum information

Quantum information is the information of the state of a quantum system. It is the basic entity of study in quantum information theory, and can be manipulated using quantum information processing techniques. Quantum information refers to both t ...

, David Bohm

David Joseph Bohm (; 20 December 1917 – 27 October 1992) was an American scientist who has been described as one of the most significant Theoretical physics, theoretical physicists of the 20th centuryDavid Peat Who's Afraid of Schrödinger' ...

( Quantum potential).

Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( ; ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating psychopathology, pathologies seen as originating fro ...

, known as the father of psychoanalysis

PsychoanalysisFrom Greek language, Greek: and is a set of theories and techniques of research to discover unconscious mind, unconscious processes and their influence on conscious mind, conscious thought, emotion and behaviour. Based on The Inte ...

, is one of the most influential scientists of the 20th century. In creating psychoanalysis, a clinical method for treating psychopathology

Psychopathology is the study of mental illness. It includes the signs and symptoms of all mental disorders. The field includes Abnormal psychology, abnormal cognition, maladaptive behavior, and experiences which differ according to social norms ...

through dialogue between a patient and a psychoanalyst, Freud developed therapeutic techniques such as the use of free association and discovered transference

Transference () is a phenomenon within psychotherapy in which repetitions of old feelings, attitudes, desires, or fantasies that someone displaces are subconsciously projected onto a here-and-now person. Traditionally, it had solely co ...

, establishing its central role in the analytic process. Freud's redefinition of sexuality to include its infantile forms led him to formulate the Oedipus complex

In classical psychoanalytic theory, the Oedipus complex is a son's sexual attitude towards his mother and concomitant hostility toward his father, first formed during the phallic stage of psychosexual development. A daughter's attitude of desire ...

as the central tenet of psychoanalytical theory. His analysis of dream

A dream is a succession of images, ideas, emotions, and sensation (psychology), sensations that usually occur involuntarily in the mind during certain stages of sleep. Humans spend about two hours dreaming per night, and each dream lasts around ...

s as wish-fulfillments provided him with models for the clinical analysis of symptom formation and the mechanisms of repression as well as for elaboration of his theory of the unconscious as an agency disruptive of conscious states of mind. Freud postulated the existence of libido

In psychology, libido (; ) is psychic drive or energy, usually conceived of as sexual in nature, but sometimes conceived of as including other forms of desire. The term ''libido'' was originally developed by Sigmund Freud, the pioneering origin ...

, an energy with which mental processes and structures are invested and which generates erotic attachments, and a death drive

In classical psychoanalysis of Sigmund Freud, the death drive () is the Drive theory, drive toward destruction in the sense of breaking down complex phenomena into their constituent parts or bringing life back to its inanimate 'dead' state, often ...

, the source of repetition, hate, aggression and neurotic guilt.

John von Neumann

John von Neumann ( ; ; December 28, 1903 – February 8, 1957) was a Hungarian and American mathematician, physicist, computer scientist and engineer. Von Neumann had perhaps the widest coverage of any mathematician of his time, in ...

, a mathematician and physicist, made major contributions to a number of fields, including foundations of mathematics

Foundations of mathematics are the mathematical logic, logical and mathematics, mathematical framework that allows the development of mathematics without generating consistency, self-contradictory theories, and to have reliable concepts of theo ...

, functional analysis