Critics Of Islam on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Criticism of

by Gabriel Oussani, ''Catholic Encyclopedia''. Retrieved 16 April 2006. Criticism of Islam has been aimed at the life of

by Kaufmann Kohler Duncan B. McDonald, ''Jewish Encyclopedia''. Retrieved 22 April 2006. Criticisms of Islam have also been directed at historical practices, like the recognition of slavery as an institutionBrunschvig. 'Abd; ''

Online text

/ref>

by David Novak. Retrieved 29 April 2006. In his essay ''Islam Through Western Eyes'', the cultural critic

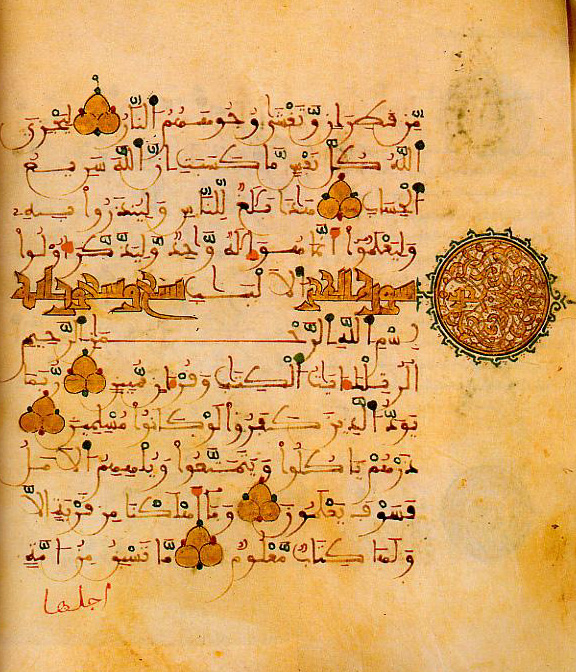

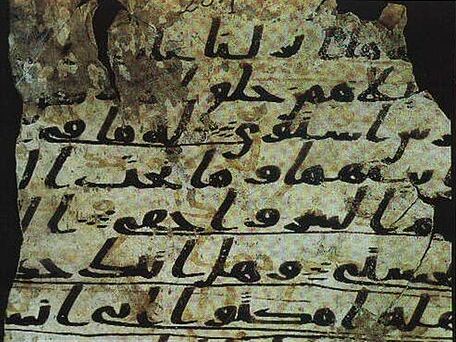

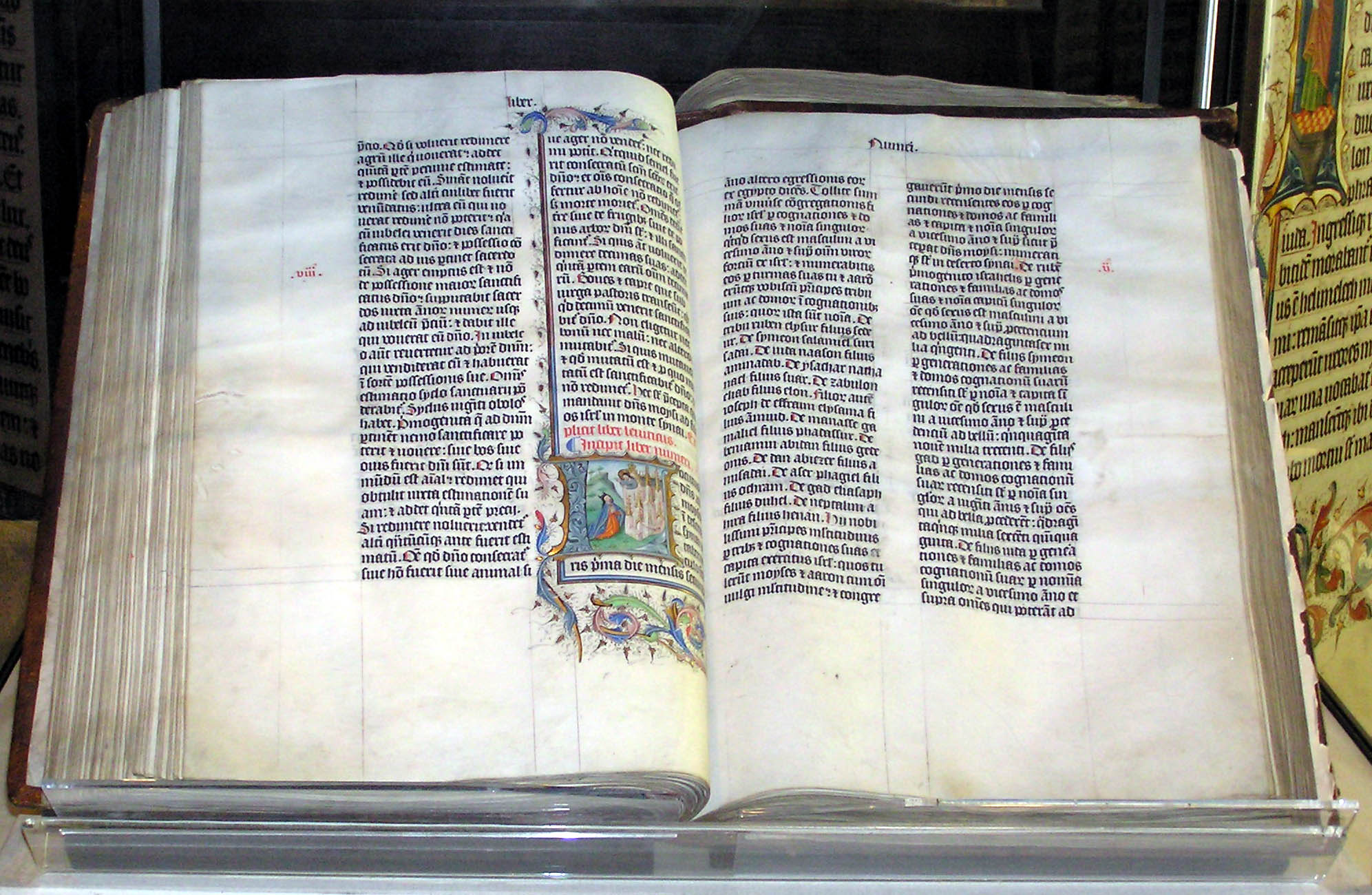

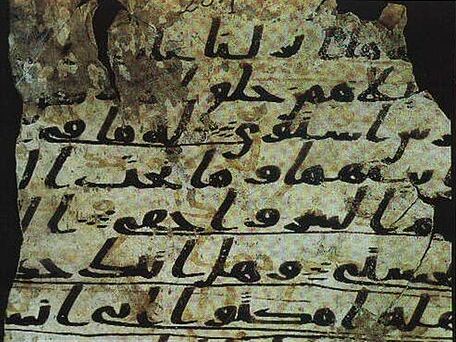

In the lifetime of Muhammad, the Qur'an was primarily preserved orally, with various written fragments recorded by his companions. Some revisionist scholars argue that the complete compilation of the Qur'an in its current form occurred much later—possibly between 150 to 300 years after Muhammad’s death. The standard Islamic view holds that the Qur'an was compiled shortly after the death of Muhammad in 632 and canonized during the caliphate of Uthman ibn Affan (r. 644–656). This position has been increasingly supported by manuscript evidence and recent scholarship. The Birmingham Qur'an, radiocarbon-dated to 568–645 CE, led Nicolai Sinai to conclude that a large portion of the Qurʾānic text was already in circulation by the 650s, and that late canonization theories such as Wansbrough’s are now “safely ruled out.” Marijn van Putten likewise finds that early manuscripts share distinctive spelling patterns, indicating they descend from a single written source—likely the Uthmanic codex.

The Qur’an asserts its own inimitability and perfection, a claim that has been disputed by critics. One such criticism is that sentences about God in the Quran are sometimes followed immediately by those in which God is the speaker."Koran"

In the lifetime of Muhammad, the Qur'an was primarily preserved orally, with various written fragments recorded by his companions. Some revisionist scholars argue that the complete compilation of the Qur'an in its current form occurred much later—possibly between 150 to 300 years after Muhammad’s death. The standard Islamic view holds that the Qur'an was compiled shortly after the death of Muhammad in 632 and canonized during the caliphate of Uthman ibn Affan (r. 644–656). This position has been increasingly supported by manuscript evidence and recent scholarship. The Birmingham Qur'an, radiocarbon-dated to 568–645 CE, led Nicolai Sinai to conclude that a large portion of the Qurʾānic text was already in circulation by the 650s, and that late canonization theories such as Wansbrough’s are now “safely ruled out.” Marijn van Putten likewise finds that early manuscripts share distinctive spelling patterns, indicating they descend from a single written source—likely the Uthmanic codex.

The Qur’an asserts its own inimitability and perfection, a claim that has been disputed by critics. One such criticism is that sentences about God in the Quran are sometimes followed immediately by those in which God is the speaker."Koran"

From the ''Jewish Encyclopedia''. Retrieved 21 January 2008. The Iranian journalist

Critics point to various pre-existing sources to argue against the traditional narrative of revelation from God. Some scholars have calculated that one third of the Quran has pre-Islamic Christian origins. Aside from the Bible, the Quran is said to rely on several

Critics point to various pre-existing sources to argue against the traditional narrative of revelation from God. Some scholars have calculated that one third of the Quran has pre-Islamic Christian origins. Aside from the Bible, the Quran is said to rely on several

The Quraniyun of the Twentieth Century

Masters Assertion, September 2006Ahmad, Kassim. "Hadith: A Re-evaluation", 1986. English translation 1997 While this view has attracted attention in some reformist circles, it remains a minority position in Islamic thought. Mainstream Islamic traditions hold that the Qur’an expects Muslims to follow the Prophet’s example, which is primarily preserved through hadith. Verses like Qur’an 59:7 (“...whatever the Messenger gives you, take it...”) are often cited as support. Scholars such as The traditional view of Islam has faced scrutiny due to a lack of consistent supporting evidence, such as limited archaeological finds and some discrepancies with non-Muslim sources.Donner, Fred ''Narratives of Islamic Origins: The Beginnings of Islamic Historical Writing'', Darwin Press, 1998 In the 1970s, a number of scholars began to re-evaluate established Islamic history, proposing that earlier accounts may have been altered over time.Donner, Fred ''Narratives of Islamic Origins: The Beginnings of Islamic Historical Writing'', Darwin Press, 1998 They sought to reconstruct early Islamic history using alternative sources like coins, inscriptions, and non-Islamic texts. Prominent among these scholars was

The traditional view of Islam has faced scrutiny due to a lack of consistent supporting evidence, such as limited archaeological finds and some discrepancies with non-Muslim sources.Donner, Fred ''Narratives of Islamic Origins: The Beginnings of Islamic Historical Writing'', Darwin Press, 1998 In the 1970s, a number of scholars began to re-evaluate established Islamic history, proposing that earlier accounts may have been altered over time.Donner, Fred ''Narratives of Islamic Origins: The Beginnings of Islamic Historical Writing'', Darwin Press, 1998 They sought to reconstruct early Islamic history using alternative sources like coins, inscriptions, and non-Islamic texts. Prominent among these scholars was

According to the

According to the

Who Are the Moderate Muslims?

/ref> However, the Islamic hadiths and scholars such as Dr Zakir Naik refer to fighting and not to trust "non-believers" and Christians in certain situations or events such as during times of war.

online

Harris argues that

According to

According to

In Islam, apostasy along with heresy and blasphemy (verbal insult to religion) is considered a form of disbelief. The Qur'an states that apostasy would bring punishment in the Afterlife, but takes a relatively lenient view of apostasy in this life (Q 9:74; 2:109).

While Shafi'i interprets verse Quran 2:217 as adducing the main evidence for the death penalty in Quran, the historian W. Heffening states that

In Islam, apostasy along with heresy and blasphemy (verbal insult to religion) is considered a form of disbelief. The Qur'an states that apostasy would bring punishment in the Afterlife, but takes a relatively lenient view of apostasy in this life (Q 9:74; 2:109).

While Shafi'i interprets verse Quran 2:217 as adducing the main evidence for the death penalty in Quran, the historian W. Heffening states that

Quran's teachings on matters of war and peace have become topics of heated discussion in recent years. On the one hand, some critics claim that certain verses of the Quran sanction military action against unbelievers as a whole both during the lifetime of Muhammad and after.''Warrant for terror: fatwās of radical Islam and the duty of jihād'', p. 68, Shmuel Bar, 2006

Quran's teachings on matters of war and peace have become topics of heated discussion in recent years. On the one hand, some critics claim that certain verses of the Quran sanction military action against unbelievers as a whole both during the lifetime of Muhammad and after.''Warrant for terror: fatwās of radical Islam and the duty of jihād'', p. 68, Shmuel Bar, 2006

The Religion of Islam

(6th Edition), Ch V "Jihad" p. 414 "When shall war cease". Published by '' The Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement'' and allows fighting only in self-defense.The Qur'anic Commandments Regarding War/Jihad

An English rendering of an Urdu article appearing in Basharat-e-Ahmadiyya Vol. I, pp. 228–32, by Dr. Basharat Ahmad; published by the Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement for the Propagation of Islam Charles Mathewes characterizes the peace verses as saying that "if others want peace, you can accept them as peaceful even if they are not Muslim." As an example, Mathewes cites the second sura, which commands believers not to transgress limits in warfare: "fight in God's cause against those who fight you, but do not transgress limits n aggression God does not love transgressors" (2:190). Orientalist

Bukhari 059.527

Most Sunnis believe that Umar later was merely enforcing a prohibition that was established during Muhammad's time. Shia contest the criticism that nikah mut'ah is a cover for prostitution, and argue that the unique legal nature of temporary marriage distinguishes Mut'ah ideologically from prostitution.Temporary marriage

''

Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

can take many forms, including academic critiques, political criticism, religious criticism, and personal opinions. Subjects of criticism include Islamic beliefs, practices, and doctrines.

Criticism of Islam has been present since its formative stages, and early expressions of disapproval were made by Christians

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the world. The words '' Christ'' and ''C ...

, Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

, and some former Muslims

Former Muslims or ex-Muslims are people who were Muslims, but subsequently left Islam.

Although their numbers have increased in the US, ex-Muslims still face ostracism or retaliation from their families and communities due to beliefs about apos ...

like Ibn al-Rawandi

Abu al-Hasan Ahmad ibn Yahya ibn Ishaq al-Rawandi (), commonly known as Ibn al-Rawandi (; 827–911 CEAl-Zandaqa Wal Zanadiqa, by Mohammad Abd-El Hamid Al-Hamad, First edition 1999, Dar Al-Taliaa Al-Jadida, Syria (Arabic)), was a scholar and ...

.De Haeresibus by John of Damascus

John of Damascus or John Damascene, born Yūḥana ibn Manṣūr ibn Sarjūn, was an Arab Christian monk, priest, hymnographer, and apologist. He was born and raised in Damascus or AD 676; the precise date and place of his death is not know ...

. See Migne

Jacques Paul Migne (; 25 October 1800 – 24 October 1875) was a French priest who published inexpensive and widely distributed editions of theological works, encyclopedias, and the texts of the Church Fathers, with the goal of providing a ...

. ''Patrologia Graeca

The ''Patrologia Graeca'' (''PG'', or ''Patrologiae Cursus Completus, Series Graeca'') is an edited collection of writings by the Church Fathers and various secular writers, in the Greek language. It consists of 161 volumes produced in 1857–18 ...

'', vol. 94, 1864, cols 763–73. An English translation by the Reverend John W Voorhis appeared in ''The Moslem World'' for October 1954, pp. 392–98. Subsequently, the Muslim world

The terms Islamic world and Muslim world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs, politics, and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is ...

itself faced criticism after the September 11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, also known as 9/11, were four coordinated Islamist terrorist suicide attacks by al-Qaeda against the United States in 2001. Nineteen terrorists hijacked four commercial airliners, crashing the first two into ...

.Ibn Kammuna, ''Examination of the Three Faiths'', trans. Moshe Perlmann (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1971), pp. 148–49Mohammed and Mohammedanismby Gabriel Oussani, ''Catholic Encyclopedia''. Retrieved 16 April 2006. Criticism of Islam has been aimed at the life of

Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

, the prophet of Islam, in both his public and personal lives.Ibn Warraq, The Quest for Historical Muhammad (Amherst, Mass.:Prometheus, 2000), 103. Issues relating to the authenticity and morality of the scriptures of Islam, both the Quran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a Waḥy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

and the hadith

Hadith is the Arabic word for a 'report' or an 'account f an event and refers to the Islamic oral tradition of anecdotes containing the purported words, actions, and the silent approvals of the Islamic prophet Muhammad or his immediate circle ...

s, are also discussed by critics.Bible in Mohammedian Literature.by Kaufmann Kohler Duncan B. McDonald, ''Jewish Encyclopedia''. Retrieved 22 April 2006. Criticisms of Islam have also been directed at historical practices, like the recognition of slavery as an institutionBrunschvig. 'Abd; ''

Encyclopedia of Islam

The ''Encyclopaedia of Islam'' (''EI'') is a reference work that facilitates the academic study of Islam. It is published by Brill and provides information on various aspects of Islam and the Islamic world. It is considered to be the standard ...

'' as well as Islamic imperialism impacting native

Native may refer to:

People

* '' Jus sanguinis'', nationality by blood

* '' Jus soli'', nationality by location of birth

* Indigenous peoples, peoples with a set of specific rights based on their historical ties to a particular territory

** Nat ...

cultures. More recently, Islamic beliefs regarding human origins, predestination

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby Go ...

, God's existence

The existence of God is a subject of debate in the philosophy of religion and theology. A wide variety of arguments for and against the existence of God (with the same or similar arguments also generally being used when talking about the exis ...

, and God's nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

have received criticism for perceived philosophical

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

and scientific inconsistencies.

Other criticisms center on the treatment of individuals within modern Muslim-majority countries

The terms Islamic world and Muslim world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs, politics, and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is p ...

, including issues which are related to human rights in the Islamic world, particularly in relation to the application of Islamic law

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on scriptures of Islam, particularly the Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' refers to immutable, intan ...

. As of 2014, 26% of the world's countries had anti-blasphemy laws, and 13% of them also had anti-apostasy laws. By 2017, 13 Muslim countries imposed the death penalty for apostasy

Apostasy (; ) is the formal religious disaffiliation, disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that is contrary to one's previous re ...

or blasphemy

Blasphemy refers to an insult that shows contempt, disrespect or lack of Reverence (emotion), reverence concerning a deity, an object considered sacred, or something considered Sanctity of life, inviolable. Some religions, especially Abrahamic o ...

. Amid the contemporary embrace of multiculturalism

Multiculturalism is the coexistence of multiple cultures. The word is used in sociology, in political philosophy, and colloquially. In sociology and everyday usage, it is usually a synonym for ''Pluralism (political theory), ethnic'' or cultura ...

, there has been criticism regarding how Islam may affect the willingness or ability of Muslim immigrants to assimilate in host nations.

Muslim scholars have historically responded to criticisms through apologetics and theological defenses of Islamic doctrines.

Historical background

Early Christian reactions to Islam, such as those by St. John of Damascus around fifty years after the Hijrah, were shaped by theological opposition and political conflict. According to Norman Daniel, John’s depiction of Islam confused it with pre-Islamic paganism, associating Muslim practices with idol worship at the Ka'bah. Christian polemical writing at the time took an "unusually severe attitude" toward Islam, condemning whatever Muslims believed, even when it was partially correct according to Christian teaching. Daniel notes that the method used against Islam applied established Christian techniques of theological debate, often favoring aggressive refutation over genuine understanding. This early pattern of prejudice, Daniel argues, continued without dilution into later European Orientalist scholarship, influencing views of Islam well into the modern period. Medieval Muslim society also produced unorthodox voices—such as Ibn al-Rawandī and Abū Bakr al-Rāzī—whose radical critiques of prophecy provoked vigorous rebuttals from both theologians and philosophers, illustrating the period’s lively culture of intellectual debateal-Ma'arri

Abu al-Ala al-Ma'arri, ,(December 973May 1057), also known by his Latin name Abulola Moarrensis; was an Arab philosopher, poet, and writer from Ma'arrat al-Nu'man, Syria. Because of his irreligious worldview, he is known as one of the "forem ...

, an eleventh-century antinatalist and critic of all religions. His poetry was known for its "pervasive pessimism." He believed that Islam does not have a monopoly on truth. Apologetic

Apologetics (from Greek ) is the religious discipline of defending religious doctrines through systematic argumentation and discourse. Early Christian writers (c. 120–220) who defended their beliefs against critics and recommended their fai ...

writings, attributed to the philosopher Abd-Allah ibn al-Muqaffa (), include defenses of Manichaeism against Islam and critiques of the Islamic concept of God, characterizing the Quranic deity in highly critical terms. The Jewish philosopher Ibn Kammuna, criticized Islam,Ibn Warraq. ''Why I Am Not a Muslim'', p. 3. Prometheus Books, 1995. reasoning that Shari'a was incompatible with the principles of justice.

At the same time that dissenting voices like Ibn al-Rāwandī appeared, mainstream Muslim scholars were actively strengthening Islamic doctrine against both internal and external critiques. As Hodgson notes, a range of thinkers—including the traditionalist Aṯharīs, the Ashʿarīs, and the Māturīdīs—developed vigorous defenses of revelation, sometimes by strict adherence to transmitted texts, sometimes through rational systematization. Rather than avoiding controversy, they treated public debate as a responsibility, working to articulate an intellectually coherent and resilient Islamic worldview that Hodgson describes as one of the most creatively active climates of medieval history.

During the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, Christian church officials commonly represented Islam as a Christian heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Heresy in Christian ...

or a form of idolatry.Christian Lange ''Paradise and Hell in Islamic Traditions'' Cambridge University Press, 2015 pp. 18–20 Daniel emphasizes that for much of the medieval period, Christian understanding of Islam was based more on inherited stereotypes and polemical tradition than on direct engagement with Muslim sources. They viewed Islam to be a material, rather than spiritual, religion and often explained it in apocalyptic terms.Christian Lange ''Paradise and Hell in Islamic Traditions'' Cambridge University Press, 2015 pp. 18–20 In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, European academics often portrayed Islam as an exotic Eastern religion distinct from Western religions like Judaism and Christianity, sometimes classifying it as a "Semitic" religion. The term "Mohammedanism" was used by many to criticize Islam by focusing on Muhammad's actions, reducing Islam to merely a derivative of Christianity rather than acknowledging it as a successor of Abrahamic monotheisms. By contrast, many academics nowadays study Islam as an Abrahamic religion in relation to Judaism and Christianity. The Christian apologist G. K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was an English author, philosopher, Christian apologist, journalist and magazine editor, and literary and art critic.

Chesterton created the fictional priest-detective Father Brow ...

criticized Islam as a heresy or parody of Christianity,G. K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was an English author, philosopher, Christian apologist, journalist and magazine editor, and literary and art critic.

Chesterton created the fictional priest-detective Father Brow ...

, ''The Everlasting Man

''The Everlasting Man'' is a Christian apologetics book written by G. K. Chesterton, published in 1925. It is, to some extent, a deliberate rebuttal of H. G. Wells' '' The Outline of History'', disputing Wells' portrayals of human life and civ ...

'', 1925, Chapter V, ''The Escape from Paganism''Online text

/ref>

David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism. Beg ...

(), both a naturalist

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

and a sceptic

Skepticism ( US) or scepticism ( UK) is a questioning attitude or doubt toward knowledge claims that are seen as mere belief or dogma. For example, if a person is skeptical about claims made by their government about an ongoing war then the pe ...

, considered monotheistic

Monotheism is the belief that one God is the only, or at least the dominant deity.F. L. Cross, Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. A ...

religions to be more "comfortable to sound reason" than polytheism

Polytheism is the belief in or worship of more than one god. According to Oxford Reference, it is not easy to count gods, and so not always obvious whether an apparently polytheistic religion, such as Chinese folk religions, is really so, or whet ...

but also found Islam to be more "ruthless" than Christianity.

The Greek Orthodox

Greek Orthodox Church (, , ) is a term that can refer to any one of three classes of Christian Churches, each associated in some way with Greek Christianity, Levantine Arabic-speaking Christians or more broadly the rite used in the Eastern Rom ...

bishop Paul of Antioch

Paul of Antioch () was a Melkite Christian monk, bishop and author who lived between the 11th and 13th centuries. His best known works are defences of Christianity written for Muslims and a treatise urging the conversion of Muslims and Jews.

Life ...

accepted Muhammed as a prophet, but did not consider his mission to be universal and regarded Christian law superior to Islamic law. Maimonides

Moses ben Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (, ) and also referred to by the Hebrew acronym Rambam (), was a Sephardic rabbi and Jewish philosophy, philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah schola ...

, a twelfth-century rabbi

A rabbi (; ) is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi—known as ''semikha''—following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of t ...

, did not question the strict monotheism of Islam, and considered Islam to be a instrument of divine providence for bringing all of humankind to the worship of the one true God, but was critical of the practical politics

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

of Muslim regimes and considered Islamic ethics

Islamic ethics () is the "philosophical reflection upon moral conduct" with a view to defining "good character" and attaining the "pleasure of God" (''raza-e Ilahi''). It is distinguished from " Islamic morality", which pertains to "specific norms ...

and politics to be inferior to their Jewish counterparts.The Mind of Maimonidesby David Novak. Retrieved 29 April 2006. In his essay ''Islam Through Western Eyes'', the cultural critic

Edward Said

Edward Wadie Said (1 November 1935 – 24 September 2003) was a Palestinian-American academic, literary critic, and political activist. As a professor of literature at Columbia University, he was among the founders of Postcolonialism, post-co ...

suggests that the Western view of Islam is particularly hostile for a range of religious, psychological and political reasons, all deriving from a sense "that so far as the West is concerned, Islam represents not only a formidable competitor but also a late-coming challenge to Christianity." In his view, the general basis of Orientalist thought forms a study structure in which Islam is placed in an inferior position as an object of study, thus forming a considerable bias in Orientalist writings as a consequence of the scholars' cultural make-up.

Points of criticism

The expansion of Islam

In an alleged dialogue between the Byzantine emperorManuel II Palaiologos

Manuel II Palaiologos or Palaeologus (; 27 June 1350 – 21 July 1425) was Byzantine emperor from 1391 to 1425. Shortly before his death he was tonsured a monk and received the name Matthaios (). Manuel was a vassal of the Ottoman Empire, which ...

() and a Persian scholar, the emperor criticized Islam as a faith spread by the sword. This reflected a common view in Europe during the Enlightenment period about Islam, then synonymous with the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, as a bloody, ruthless, and intolerant religion. More recently, in 2006, a similar statement of Manuel II, quoted publicly by Pope Benedict XVI

Pope BenedictXVI (born Joseph Alois Ratzinger; 16 April 1927 – 31 December 2022) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 19 April 2005 until his resignation on 28 February 2013. Benedict's election as p ...

, prompted a negative response from Muslim figures who viewed the remarks as an insulting mischaracterization of Islam. In this vein, the India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

n social reformer Pandit Lekh Ram

Pandit Lekh Ram (April 1858 – 6 March 1897) was a 19th-century social reformer, publicist, and writer from Punjab, India. He was the leader of the radical wing within the Arya Samaj, an Indian Hindu reform movement. He was known for his cr ...

() thought that Islam was grown through violence and desire for wealth, while the Nigeria

Nigeria, officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It covers an area of . With Demographics of Nigeria, ...

n author Wole Soyinka

Wole Soyinka , (born 13 July 1934) is a Nigerian author, best known as a playwright and poet. He has written three novels, ten collections of short stories, seven poetry collections, twenty five plays and five memoirs. He also wrote two transla ...

considers Islam as a "superstition" that it is mainly spread with violence and force.

This "conquest by the sword" thesis is opposed by many historians who consider the transregional development of Islam a multi-faceted phenomenon involving a range of political, social, and economic processes. The first wave of expansion, the migration of the early Muslims to Medina

Medina, officially al-Madinah al-Munawwarah (, ), also known as Taybah () and known in pre-Islamic times as Yathrib (), is the capital of Medina Province (Saudi Arabia), Medina Province in the Hejaz region of western Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, ...

to escape persecution in Mecca

Mecca, officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, is the capital of Mecca Province in the Hejaz region of western Saudi Arabia; it is the Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow valley above ...

and the subsequent conversion of Medina, was indeed peaceful. In the years to come, Muslims defended themselves against frequent Meccan incursions until Mecca's peaceful surrender in 630. By the time of Muhammed's death in 632, most Arabian tribes had formed political alliances with him and embraced Islam voluntarily, creating a foundation for future regional expansion. In the centuries that followed, Islam extended beyond Arabia through a combination of military conquests and non-military means. While the early Islamic empires expanded into Syria, Persia, Egypt, and North Africa, Islam often remained a minority religion in those regions for several generations, a pattern that some scholars cite as evidence that political conquest did not inherently produce widespread religious conversion.

In many regions outside the initial imperial sphere, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia, Islam spread primarily through trade, cultural integration, and missionary activities. Historian Marshall Hodgson writes that Islam became “a mass people’s religion on a wave of economic expansiveness,” as Muslim merchants and missionaries introduced the faith in commercial hubs and rural towns far removed from the centers of military power. These conversions were often voluntary and linked to the appeal of Islam's social order, legal institutions, and communal ethics.

Scripture

From the ''Jewish Encyclopedia''. Retrieved 21 January 2008. The Iranian journalist

Ali Dashti

Ali Dashti (, pronounced ; 31 March 1897 – 16 January 1982) was an Iranian writer and politician of the twentieth century. Dashti served as a senator in Iran during the Pahlavi dynasty.

Life

Born into a Persian family in Dashti in Bushehr ...

() criticized the Quran, saying that "the speaker cannot have been God" in certain passages. Similarly, the secular author Ibn Warraq

Ibn Warraq (born 1946) is the pen name of an anonymous author critical of Islam. He is the founder of the Institute for the Secularisation of Islamic Society and used to be a senior research fellow at the Center for Inquiry, focusing on Qurani ...

gives Surah al-Fatiha

Al-Fatiha () is the first chapter () of the Quran. It consists of seven verses (') which consist of a prayer for guidance and mercy.

Al-Fatiha is recited in Muslim obligatory and voluntary prayers, known as ''salah''. The primary literal mea ...

as an example of a passage which is "clearly addressed to God, in the form of a prayer." However, scholars like Mustansir Mir and Michael Sells explain that these sudden shifts in speaker or pronouns—called ''iltifāt'' in Arabic—are a common and deliberate feature of classical Arabic style. They are used to keep the listener engaged, highlight key ideas, or mark a shift in tone. Mir shows how this technique strengthens the Qur’an’s overall structure and rhythm, while Sells argues that it also reflects God’s implied transcendence—by changing how God is referred to, the Qur’an avoids limiting Him to one fixed role or persona.

The Christian theologian Philip Schaff

Philip Schaff (January 1, 1819 – October 20, 1893) was a Swiss-born, German-educated Protestant theologian and ecclesiastical historian, who spent most of his adult life living and teaching in the United States.

Life and career

Schaff was ...

() praises the Quran for its poetic beauty, religious fervor, and wise counsel, but considers this mixed with "absurdities, bombast, unmeaning images, and low sensuality."Schaff, P., & Schaff, D. S. (1910). History of the Christian church. Third edition. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. Volume 4, Chapter III, section 44 "The Koran, And The Bible" The orientalist Gerd Puin believes that the Quran contains many verses which are incomprehensible, a view rejected by Muslims and many other orientalists. '' Apology of al-Kindy'', a medieval polemical work, describes the narratives in the Quran as "all jumbled together and intermingled," and regards this as "evidence that many different hands have been at work therein." These criticisms often come from reading the Qur’an like a modern book, rather than as a message originally spoken aloud, according to some scholars. Scholars like Angelika Neuwirth explain that its sudden shifts in voice and repetition weren’t mistakes, but ways to hold attention and make meaning clearer to a live audience. Michael Sells points out that the Qur’an’s rhythm and sound patterns were key to how it was understood, especially in the early chapters. And as Mustansir Mir and classical scholars like al-Jurjānī have shown, what may seem like abrupt changes in topic often reflect careful design, helping ideas flow and giving extra weight to key points.

Pre-existing sources

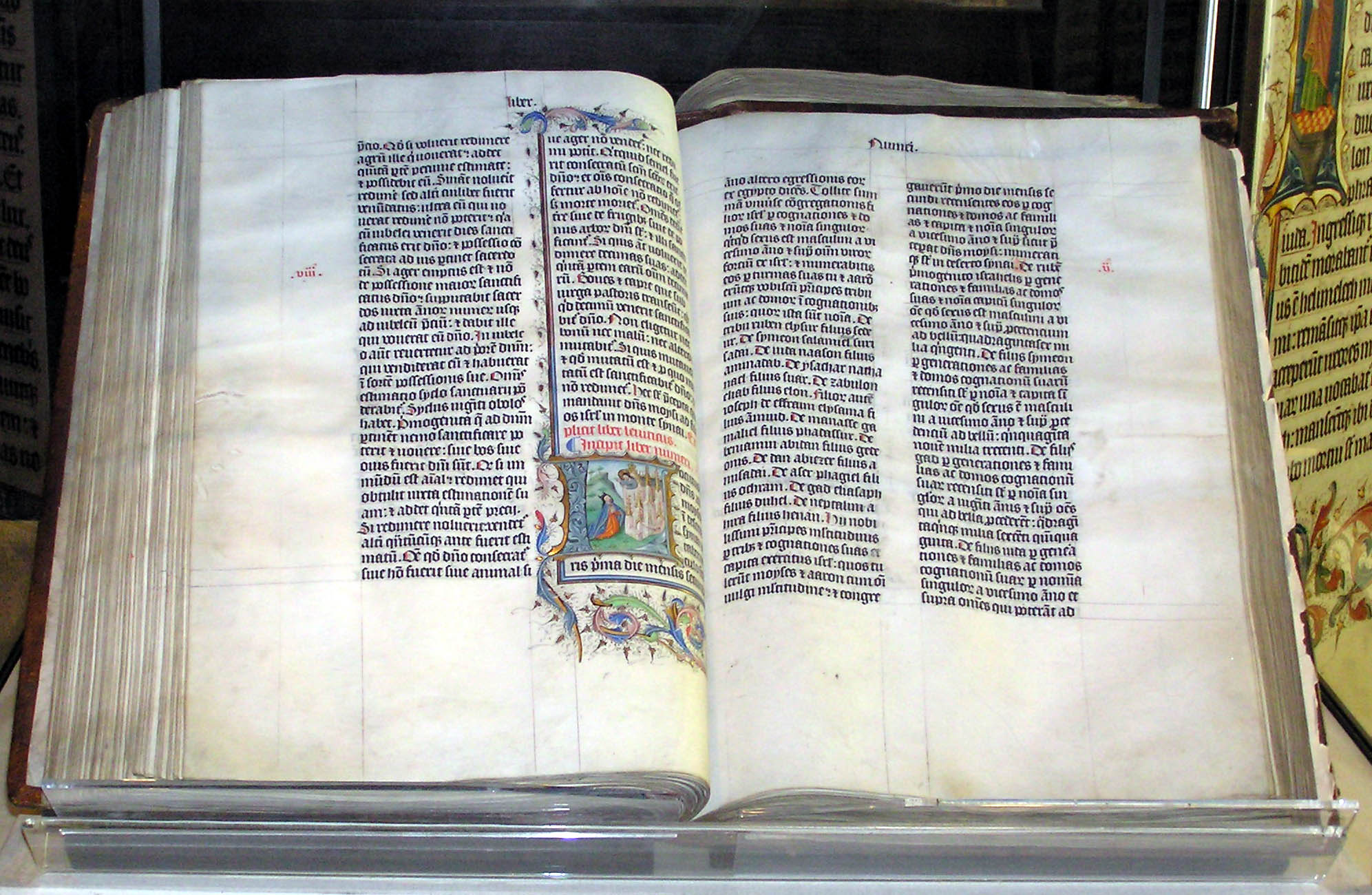

Critics point to various pre-existing sources to argue against the traditional narrative of revelation from God. Some scholars have calculated that one third of the Quran has pre-Islamic Christian origins. Aside from the Bible, the Quran is said to rely on several

Critics point to various pre-existing sources to argue against the traditional narrative of revelation from God. Some scholars have calculated that one third of the Quran has pre-Islamic Christian origins. Aside from the Bible, the Quran is said to rely on several Apocrypha

Apocrypha () are biblical or related writings not forming part of the accepted canon of scripture, some of which might be of doubtful authorship or authenticity. In Christianity, the word ''apocryphal'' (ἀπόκρυφος) was first applied to ...

l and sources, like the Protoevangelium of James

The Gospel of James (or the Protoevangelium of James) is a second-century infancy gospel telling of the miraculous conception of the Virgin Mary, her upbringing and marriage to Joseph, the journey of the couple to Bethlehem, the birth of Jesu ...

,Leirvik 2010, pp. 33–34. Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew

The Latin Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew (or The Infancy Gospel of Matthew) is a part of the New Testament apocrypha. In antiquity, the text was called The Book About the Origin of the Blessed Mary and the Childhood of the Savior. Pseudo-Matthew is one ...

, and several infancy gospel Infancy gospels (Greek: ''protoevangelion'') are a genre of religious texts that arose in the 2nd century. They are part of New Testament apocrypha, and provide accounts of the birth and early life of Jesus. The texts are of various and uncertain or ...

s. Certain narratives also are said to potentially parallel Jewish Midrashic literature, Several narratives rely on Jewish Midrash Tanhuma

Midrash Tanhuma (), also known as Yelammedenu, is the name given to a homiletic midrash on the entire Torah, and it is known in several different versions or collections. Tanhuma bar Abba is not the author of the text but instead is a figure to w ...

sources, such as the account of Cain learning to bury the body of Abel in Quran 5:31, which some link to the Midrash Tanhuma. Christian apologist Norman Geisler

Norman Leo Geisler (July 21, 1932 – July 1, 2019) was an American Christian systematic theologian, philosopher, and apologist. He was the co-founder of two non-denominational evangelical seminaries ( Veritas International University an ...

argues that the dependence of the Quran on preexisting sources is one evidence of a purely human origin. Richard Carrier

Richard Cevantis Carrier (born December 1, 1969) is an American ancient historian. He is a long-time contributor to skeptical websites, including The Secular Web and Freethought Blogs. Carrier has published a number of books and articles on ph ...

regards this reliance on pre-Islamic Christian sources as evidence that Islam derived from a Torah-observant

The Torah ( , "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The Torah is also known as the Pentateuch () or ...

sect of Christianity. He also notes that assessing the Qur’an’s origins involves unresolved questions and methodological challenges that continue to divide scholars.

In Islamic belief, the Qur’an’s references to earlier scriptures are not seen as copied from them, but as confirming and correcting them. The Qur’an describes itself as “confirming what came before it and as a safeguard over it” (Q 5:48), invoking the concept of taḥrīf—the belief that previous revelations were divinely revealed but later distorted. Scholar Sidney H. Griffith explains that the Qur’an affirms earlier scripture while correcting beliefs that, from the Islamic perspective, had gone astray. He adds that many of these stories were transmitted orally in Late Antiquity, and describes the Qur’an’s engagement with them as “a re-presentation, not a mere repetition.” Angelika Neuwirth similarly sees the Qur’an as part of a shared scriptural culture, reworking familiar material to create what she calls a “polyphonic, multilayered and highly referential text.” Gabriel Said Reynolds describes the Qur’an as functioning more like a sermon than a historical record—drawing on known narratives to deliver its own theological message rather than replicating earlier texts.

Criticism of the Hadith

It has been suggested that there exists around theHadith

Hadith is the Arabic word for a 'report' or an 'account f an event and refers to the Islamic oral tradition of anecdotes containing the purported words, actions, and the silent approvals of the Islamic prophet Muhammad or his immediate circle ...

(Muslim traditions relating to the ''Sunnah

is the body of traditions and practices of the Islamic prophet Muhammad that constitute a model for Muslims to follow. The sunnah is what all the Muslims of Muhammad's time supposedly saw, followed, and passed on to the next generations. Diff ...

'' (words and deeds) of Muhammad) three major sources of corruption: political conflicts, sectarian prejudice, and the desire to translate the underlying meaning, rather than the original words verbatim.Brown, Daniel W. "Rethinking Tradition in Modern Islamic Thought", 1999. pp. 113, 134.

Quranists

Quranism () is an Islamic movement that holds the belief that the Quran is the only valid source of religious belief, guidance, and law in Islam. Quranists believe that the Quran is clear, complete, and that it can be fully understood without ...

, a theological movement within Islam, reject its authority on the grounds that the Quran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a Waḥy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

itself is sufficient for guidance, as it claims that nothing essential has been omitted. They believe that reliance on the Hadith has caused people to deviate from the original intent of God's revelation to Muhammad, which they see as adherence to the Quran alone. Ghulam Ahmed Pervez

Ghulam Ahmad Parwez (; 1903–1985) was a well-known teacher of the Quran in India and Pakistan. He posed a challenge to the established Sunni doctrine by interpreting Quranic themes with a logical approach. The work 'Islam: A Challenge to Re ...

was one of these critics and was denounced as a non-believer by thousands of orthodox clerics. In his work ''Maqam-e Hadith'' he considered any hadith that goes against the teachings of Quran to have been falsely attributed to the Prophet. Kassim Ahmad

Kassim Ahmad (9 September 1933 – 10 October 2017) was a Malaysian Muslim philosopher, intellectual, writer, poet and an educator. He was also a socialist politician in the early days of Federation of Malaya, Malaya and later Malaysia and was det ...

argued that some hadith promote ideas that conflict with science and create sectarian issues.Latif, Abu Ruqayyah FarasatThe Quraniyun of the Twentieth Century

Masters Assertion, September 2006Ahmad, Kassim. "Hadith: A Re-evaluation", 1986. English translation 1997 While this view has attracted attention in some reformist circles, it remains a minority position in Islamic thought. Mainstream Islamic traditions hold that the Qur’an expects Muslims to follow the Prophet’s example, which is primarily preserved through hadith. Verses like Qur’an 59:7 (“...whatever the Messenger gives you, take it...”) are often cited as support. Scholars such as

Jonathan A.C. Brown

Jonathan Andrew Cleveland Brown, born August 7, 1977, is a university academic and American scholar of Islamic studies. Since 2012, he has served as an associate professor at Georgetown University's Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service. He h ...

explain that hadith are seen not as additions to the Qur’an, but as practical explanations of its more general commands, such as how to pray or fast. He also notes that early Muslim scholars created detailed methods to check whether reports about the Prophet were reliable, including analysis of the transmitters ('' isnād'') and the consistency of the content (''matn

Matn () is an Islamic term that is used in relation to Hadith terminology. It means the text of the hadith, excluding the isnad.

Use

A hadith is made of both an isnad (chain of transmission) and a matn.

A hadith would typically adopt the f ...

''). Fabricated or weak hadith were systematically identified and rejected in dedicated works.

Modern Western scholarship has raised doubts about the historicity and authenticity of hadith, while Joseph Schacht

Joseph Franz Schacht (, 15 March 1902 – 1 August 1969) was a British-German professor of Arabic and Islam at Columbia University in New York. He was the leading Western scholar in the areas of Islamic law and hadith studies, whose ''Origins of M ...

argued that there is no evidence of legal traditions prior to 722. Schacht concluded that the Sunna attributed to the Prophet consists of material from later periods rather than the actual words and deeds of the Prophet. While Schacht’s theory shaped much of 20th-century scholarship, more recent studies using broader evidence and refined methods have significantly revised his conclusions. Scholars such as Harald Motzki

Harald Motzki (1948–2019) was a German-trained Islamic scholar who wrote on the transmission of hadith. He received his doctorate in Islamic Studies in 1978 from the University of Bonn. He was a professor of Islamic Studies at Nijmegen University ...

have challenged this view by analyzing early legal texts and showing that many hadith can be reliably traced to the late 7th century, suggesting that legal traditions were already forming within the first generations of Muslims, earlier than Schacht proposed. Scholars like Wilferd Madelung

Wilferd Ferdinand Madelung FBA (26 December 1930 – 9 May 2023) was a German author and scholar of Islamic history widely recognised for his contributions to the fields of Islamic and Iranian studies. He was appreciated in Iran for his "know ...

have argued that a complete dismissal of hadith as late fiction is "unjustified".

The traditional view of Islam has faced scrutiny due to a lack of consistent supporting evidence, such as limited archaeological finds and some discrepancies with non-Muslim sources.Donner, Fred ''Narratives of Islamic Origins: The Beginnings of Islamic Historical Writing'', Darwin Press, 1998 In the 1970s, a number of scholars began to re-evaluate established Islamic history, proposing that earlier accounts may have been altered over time.Donner, Fred ''Narratives of Islamic Origins: The Beginnings of Islamic Historical Writing'', Darwin Press, 1998 They sought to reconstruct early Islamic history using alternative sources like coins, inscriptions, and non-Islamic texts. Prominent among these scholars was

The traditional view of Islam has faced scrutiny due to a lack of consistent supporting evidence, such as limited archaeological finds and some discrepancies with non-Muslim sources.Donner, Fred ''Narratives of Islamic Origins: The Beginnings of Islamic Historical Writing'', Darwin Press, 1998 In the 1970s, a number of scholars began to re-evaluate established Islamic history, proposing that earlier accounts may have been altered over time.Donner, Fred ''Narratives of Islamic Origins: The Beginnings of Islamic Historical Writing'', Darwin Press, 1998 They sought to reconstruct early Islamic history using alternative sources like coins, inscriptions, and non-Islamic texts. Prominent among these scholars was John Wansbrough

John Edward Wansbrough (February 19, 1928 – June 10, 2002) was an American historian of Islamic origins and Quranic studies and professor who taught at the University of London's School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), where he was vi ...

. Recent scholarship has taken a more cautious view of these revisionist claims. Fred M. Donner

Fred McGraw Donner (born 1945) is a scholar of Islam and Peter B. Ritzma Professor of Near Eastern History at the University of Chicago.

argues that the early Muslim community was too decentralized to have invented its religious tradition wholesale, and that early texts reflect sincere belief rather than retrospective construction. He also points to documentary evidence—such as inscriptions and papyri from the 7th century—that aligns with the existence of an identifiable Muslim movement. In addition, Ahmed El Shamsy has shown that early Muslim scholars developed rigorous methods for verifying transmission and preserving texts, creating a critical scholarly culture comparable to, and in some respects more advanced than, that of contemporaneous manuscript traditions.

Criticism of Muhammad

The Christian missionarySigismund Koelle

Sigismund Wilhelm Koelle or Kölle (July 14, 1820 – February 18, 1902) was a German missionary working on behalf of the London-based Church Mission Society, Church Missionary Society, at first in Sierra Leone, where he became a pioneer scholar o ...

and the former Muslim Ibn Warraq

Ibn Warraq (born 1946) is the pen name of an anonymous author critical of Islam. He is the founder of the Institute for the Secularisation of Islamic Society and used to be a senior research fellow at the Center for Inquiry, focusing on Qurani ...

have criticized Muhammad's actions as immoral. In one instance, the Jewish poet Ka'b ibn al-Ashraf

Ka'b ibn al-Ashraf (; died ) was, according to Islamic texts, a pre-Islamic Arabic poet and contemporary of Muhammad in Medina. Scholars identify him as a Jewish leader.

Biography

Ka'b was born to a father from the Arab Tayy tribe and a mother ...

provoked the Meccan tribe of Quraysh

The Quraysh () are an Tribes of Arabia, Arab tribe who controlled Mecca before the rise of Islam. Their members were divided into ten main clans, most notably including the Banu Hashim, into which Islam's founding prophet Muhammad was born. By ...

to fight Muslims and wrote erotic

Eroticism () is a quality that causes sexual feelings, as well as a philosophical contemplation concerning the aesthetics of sexual desire, sensuality, and romantic love. That quality may be found in any form of artwork, including painting, sculp ...

poetry about their women, and was apparently plotting to assassinate Muhammad.Uri Rubin, The Assassination of Kaʿb b. al-Ashraf, Oriens, Vol. 32. (1990), pp. 65–71. Muhammad called upon his followers to kill Ka'b, and he was consequently assassinated by Muhammad ibn Maslama

Muhammad ibn Maslamah al-Ansari (; 588 or 591 – 663 or 666) was a companion of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. He was known as "The Knight of Allah's Prophet".Muhammad ibn Saad. ''Kitab al-Tabaqat al-Kabir'' vol. 3. Translated by Bewley, A. (2 ...

, an early Muslim. Such criticisms were countered by the historian William M. Watt, who argues on the basis of moral relativism

Moral relativism or ethical relativism (often reformulated as relativist ethics or relativist morality) is used to describe several Philosophy, philosophical positions concerned with the differences in Morality, moral judgments across different p ...

that Muhammad should be judged by the standards and norms of his own time and geography, rather than ours. The fourteenth-century poem ''Divine Comedy

The ''Divine Comedy'' (, ) is an Italian narrative poetry, narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun and completed around 1321, shortly before the author's death. It is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature and one of ...

'' by the Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

poet Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

contains images of Muhammad, picturing him the eighth circle of hell as a Heresiarch

In Christian theology, a heresiarch (also hæresiarch, according to the ''Oxford English Dictionary''; from Greek: , ''hairesiárkhēs'' via the late Latin ''haeresiarcha''Cross and Livingstone, ''Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church'' 1974) ...

, along with his cousin and son-in-law Ali ibn Abi Talib

Ali ibn Abi Talib (; ) was the fourth Rashidun caliph who ruled from until Assassination of Ali, his assassination in 661, as well as the first imamate in Shia doctrine, Shia Imam. He was the cousin and son-in-law of the Islamic prophet Muha ...

.G. Stone ''Dante's Pluralism and the Islamic Philosophy of Religion'' Springer, 12 May 2006 p. 132Minou Reeves, P. J. Stewart ''Muhammad in Europe: A Thousand Years of Western Myth-Making'' NYU Press, 2003 p. 93–96 Dante does not blame Islam as a whole but accuses Muhammad of schism

A schism ( , , or, less commonly, ) is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization, movement, or religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a split in what had previously been a single religious body, suc ...

for establishing another religion after Christianity. Some medieval ecclesiastical writers portrayed Muhammad as possessed by Satan

Satan, also known as the Devil, is a devilish entity in Abrahamic religions who seduces humans into sin (or falsehood). In Judaism, Satan is seen as an agent subservient to God, typically regarded as a metaphor for the '' yetzer hara'', or ' ...

, a "precursor of the Antichrist

In Christian eschatology, Antichrist (or in broader eschatology, Anti-Messiah) refers to a kind of entity prophesied by the Bible to oppose Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ and falsely substitute themselves as a savior in Christ's place before ...

" or the Antichrist himself. ' Tultusceptru de libro domni Metobii'', an Andalusian manuscript of unknown origins, describes how Muhammad (called Ozim, from Hashim

Hashim () is a common male Arabic given name.

Notable people with the name include:

*Hashim ibn Abd Manaf

* Hashim Amir Ali

* Hashim Shah

* Hashim Amla

* Hashim Thaçi

* Hashim Khan

* Hashim Qureshi

* Mir Hashim Ali Khan

*Hashim al-Atassi

* Hashi ...

) was tricked by Satan into adulterating an originally pure divine revelation: God was concerned about the spiritual fate of the Arabs and wanted to correct their deviation from the faith. He then sent an angel to the Christian monk Osius who ordered him to preach to the Arabs. Osius, however, was in ill-health and instead ordered a young monk, Ozim, to carry out the angel's orders. Ozim set out to follow his orders, but was stopped by an evil angel on the way. The ignorant Ozim believed him to be the same angel that had spoken to Osius before. The evil angel modified and corrupted the original message given to Ozim by Osius, and renamed Ozim Muhammad. From this followed the erroneous teachings of Islam, according to ''Tultusceptru''.

Islamic ethics

Catholic Encyclopedia

''The'' ''Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church'', also referred to as the ''Old Catholic Encyclopedia'' and the ''Original Catholic Encyclopedi ...

, while there is much to be admired and affirmed in Islamic ethics, its originality or superiority is rejected.

Critics stated that the Quran 4:34 allows Muslim men to discipline their wives by striking them. There is however evidence from Islamic hadiths and scholars such as Ibn Kathir that demonstrates that only a twig or leaf can be used by a man to "strike" their wife and this is not allowed to cause pain or injure their wife but to show their frustration. Moreover, confusion amongst translations of Quran with the original Arabic term "wadribuhunna" being translated as "to go away from them", "beat", "strike lightly" and "separate". The film ''Submission

Deference (also called submission or passivity) is the condition of submitting to the espoused, legitimate influence of one's superior or superiors. Deference implies a yielding or submitting to the judgment of a recognized superior, out of re ...

'' critiqued this and similar verses of the Quran by displaying them painted on the bodies of abused Muslim women.

Some critics argue that the Quran is incompatible with other religious scriptures as it attacks and advocates hate against people of other religions. Sam Harris

Samuel Benjamin Harris (born April 9, 1967) is an American philosopher, neuroscientist, author, and podcast host. His work touches on a range of topics, including rationality, religion, ethics, free will, determinism, neuroscience, meditation ...

interprets certain verses of the Quran as sanctioning military action against unbelievers as it said "Fight those who do not believe in Allah or in the Last Day and who do not consider unlawful what Allah and His Messenger have made unlawful and who do not adopt the religion of truth from those who were given the Scripture – ightuntil they give the jizyah willingly while they are humbled."( Quran 9:29)Sam HarriWho Are the Moderate Muslims?

/ref> However, the Islamic hadiths and scholars such as Dr Zakir Naik refer to fighting and not to trust "non-believers" and Christians in certain situations or events such as during times of war.

Jizya

Jizya (), or jizyah, is a type of taxation levied on non-Muslim subjects of a state governed by Sharia, Islamic law. The Quran and hadiths mention jizya without specifying its rate or amount,Sabet, Amr (2006), ''The American Journal of Islamic Soc ...

is a tax for "protection" paid by non-Muslims to a Muslim ruler, for the exemption from military service for non-Muslims, and for the permission to practice a non-Muslim faith with some communal autonomy in a Muslim state.Anver M. Emon, Religious Pluralism and Islamic Law: Dhimmis and Others in the Empire of Law, Oxford University Press, , pp. 99–109.online

Harris argues that

Muslim extremism

Islamic extremism refers to extremist beliefs, behaviors and ideologies adhered to by some Muslims within Islam. The term 'Islamic extremism' is contentious, encompassing a spectrum of definitions, ranging from academic interpretations of Is ...

is simply a consequence of taking the Quran literally, and is skeptical that moderate Islam is possible.

Max I. Dimont interprets that the Houri

In Islam, a houri (; ), or houris or hoor al ayn in plural form, is a maiden woman with beautiful eyes who lives alongside the Muslim faithful in Jannah, paradise.

They are described as the same age as the men in paradise. Since hadith states ...

s described in the Quran are specifically dedicated to "male pleasure". According to Pakistani Islamic scholar Maulana Umar Ahmed Usmani "Hur" or "hurun" is the plural of both "ahwaro" which is a masculine form and also "haurao" which is a feminine, meaning both pure males and pure females. Basically, the word 'hurun' means white, he says.

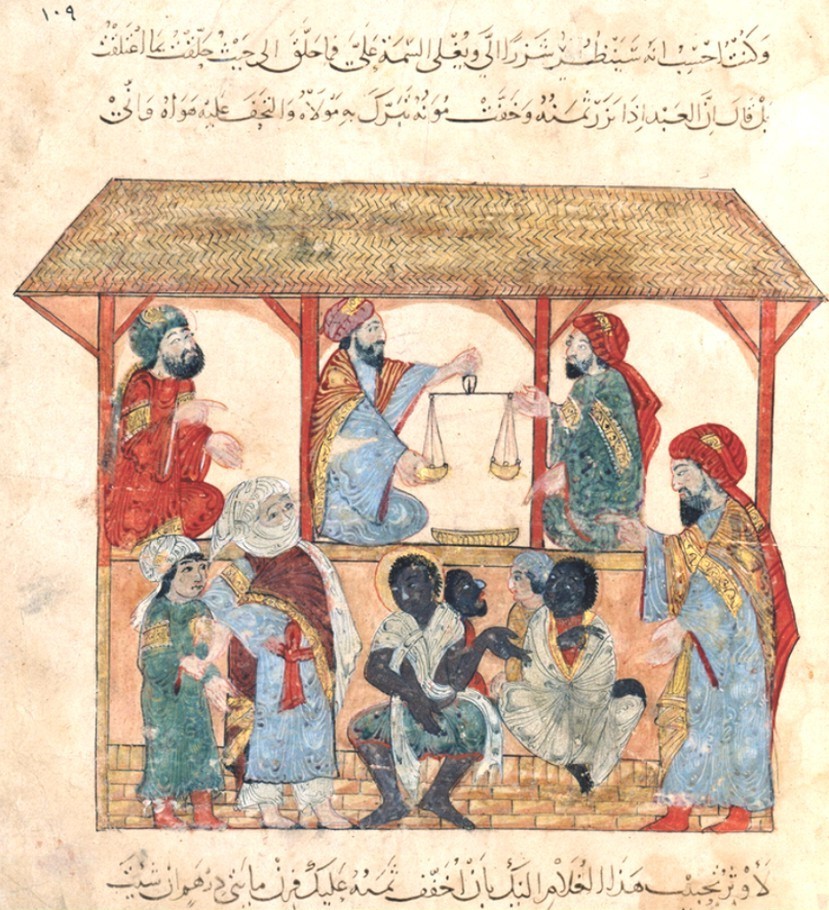

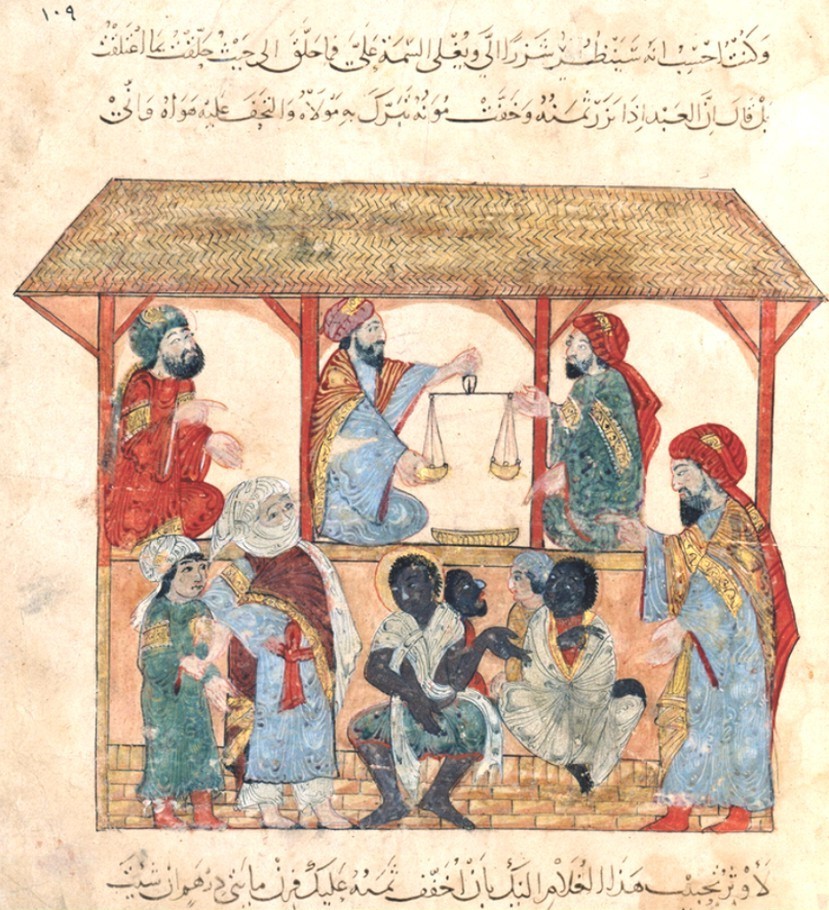

Views on slavery

According to

According to Bernard Lewis

Bernard Lewis, (31 May 1916 – 19 May 2018) was a British-American historian specialized in Oriental studies. He was also known as a public intellectual and political commentator. Lewis was the Cleveland E. Dodge Professor Emeritus of Near ...

, the Islamic injunctions against the enslavement of Muslims led to massive importation of slaves from the outside. Also Patrick Manning

Patrick Augustus Mervyn Manning (17 August 1946 – 2 July 2016) was a Trinidadian politician who served as the fourth prime minister of Trinidad and Tobago twice from 1991 to 1995, and again from 2001 to 2010. A geologist by training, Mannin ...

believes that Islam seems to have done more to protect and expand slavery than the reverse.

Brockopp, on the other hand believe that the idea of using alms for the manumission of slaves appears to be unique to the Quran ( and ). Similarly, the practice of freeing slaves in atonement for certain sins appears to be introduced by the Quran (but compare Exod 21:26-7). Also the forced prostitution of female slaves, a Near Eastern custom of great antiquity, is condemned in the Quran.John L Esposito (1998) p. 79 According to Brockopp "the placement of slaves in the same category as other weak members of society who deserve protection is unknown outside the Qur'an. Encyclopedia of the Qur'an, ''Slaves and Slavery'' Some slaves had high social status in the Muslim world

The terms Islamic world and Muslim world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs, politics, and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is ...

, such as the Mamluk

Mamluk or Mamaluk (; (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural); translated as "one who is owned", meaning "slave") were non-Arab, ethnically diverse (mostly Turkic, Caucasian, Eastern and Southeastern European) enslaved mercenaries, slave-so ...

enslaved mercenaries

A mercenary is a private individual who joins an War, armed conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any other official military. Mercenaries fight for money or other forms of payment rath ...

, who were assigned high-ranking military and administrative duties by the ruling Arab and Ottoman dynasties.

Critics argue unlike Western societies there have been no anti-slavery movements in Muslim societies,

which according to Gordon was due to the fact that it was deeply anchored in Islamic law, thus there was no ideological challenge ever mounted against slavery. According to sociologist Rodney Stark, "the fundamental problem facing Muslim theologians vis-à-vis the morality of slavery" is that Muhammad himself engaged in activities such as purchasing, selling, and owning slaves, and that his followers saw him as the perfect example to emulate. Stark contrasts Islam with Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

, writing that Christian theologians wouldn't have been able to "work their way around the biblical acceptance of slavery" if Jesus

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

had owned slaves, as Muhammad did.

Only in the early 20th century did slavery gradually became outlawed and suppressed in Muslim lands, with Muslim-majority Mauritania

Mauritania, officially the Islamic Republic of Mauritania, is a sovereign country in Maghreb, Northwest Africa. It is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Western Sahara to Mauritania–Western Sahara border, the north and northwest, ...

being the last country in the world to formally abolish slavery in 1981.

Murray Gordon characterizes Muhammad's approach to slavery as reformist rather than revolutionary that abolish slavery, but rather improved the conditions of slaves by urging his followers to treat their slaves humanely and free them as a way of expiating one's sins.

In Islamic jurisprudence

''Fiqh'' (; ) is the term for Islamic jurisprudence.Fiqh

Encyclopædia Britannica ''Fiqh'' is of ...

, slavery was theoretically an exceptional condition under the dictum ''The basic principle is liberty''.

Reports from Sudan and Somalia showing practice of slavery is in border areas as a result of continuing war and not Islamic belief. In recent years, except for some conservative Encyclopædia Britannica ''Fiqh'' is of ...

Salafi

The Salafi movement or Salafism () is a fundamentalist revival movement within Sunni Islam, originating in the late 19th century and influential in the Islamic world to this day. The name "''Salafiyya''" is a self-designation, claiming a retu ...

Islamic scholars,

most Muslim scholars found the practice "inconsistent with Qur'anic morality".

Apostasy

In Islam, apostasy along with heresy and blasphemy (verbal insult to religion) is considered a form of disbelief. The Qur'an states that apostasy would bring punishment in the Afterlife, but takes a relatively lenient view of apostasy in this life (Q 9:74; 2:109).

While Shafi'i interprets verse Quran 2:217 as adducing the main evidence for the death penalty in Quran, the historian W. Heffening states that

In Islam, apostasy along with heresy and blasphemy (verbal insult to religion) is considered a form of disbelief. The Qur'an states that apostasy would bring punishment in the Afterlife, but takes a relatively lenient view of apostasy in this life (Q 9:74; 2:109).

While Shafi'i interprets verse Quran 2:217 as adducing the main evidence for the death penalty in Quran, the historian W. Heffening states that Quran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a Waḥy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

threatens apostates with punishment in the next world only, the historian Wael Hallaq states the later addition of death penalty "reflects a later reality and does not stand in accord with the deeds of the Prophet."

According to Islamic law

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on scriptures of Islam, particularly the Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' refers to immutable, intan ...

, apostasy

Apostasy (; ) is the formal religious disaffiliation, disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that is contrary to one's previous re ...

is identified by a list of actions such as conversion to another religion, denying the existence of God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

, rejecting the prophets

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the ...

, mocking God or the prophets, idol worship, rejecting the sharia

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on Islamic holy books, scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran, Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' ...

, or permitting behavior that is forbidden by the shari'a, such as adultery

Adultery is extramarital sex that is considered objectionable on social, religious, moral, or legal grounds. Although the sexual activities that constitute adultery vary, as well as the social, religious, and legal consequences, the concept ...

or the eating of forbidden foods or drinking of alcoholic beverages. The majority of Muslim scholars hold to the traditional view that apostasy is punishable by death

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in s ...

or imprisonment until repentance, at least for adults of sound mind.

Also Sunni

Sunni Islam is the largest branch of Islam and the largest religious denomination in the world. It holds that Muhammad did not appoint any successor and that his closest companion Abu Bakr () rightfully succeeded him as the caliph of the Mu ...

and Shi'a

Shia Islam is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that Muhammad designated Ali ibn Abi Talib () as both his political successor ( caliph) and as the spiritual leader of the Muslim community ( imam). However, his right is understoo ...

scholars, agree on the difference of punishment between male and female.

Some widely held interpretations of Islam are inconsistent with Human Rights conventions that recognize the right to change religion. In particular article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is an international document adopted by the United Nations General Assembly that enshrines the Human rights, rights and freedoms of all human beings. Drafted by a UN Drafting of the Universal D ...

Some contemporary Islamic jurists, such as Hussein-Ali Montazeri

Grand Ayatollah Hussein-Ali Montazeri ( ; 24 September 1922 – 19 December 2009) was an Iranian Shia Islamic theologian, Islamic democracy advocate, writer, and human rights activist. He was one of the leaders of the Iranian Revolution and on ...

have argued or issued fatwa

A fatwa (; ; ; ) is a legal ruling on a point of Islamic law (sharia) given by a qualified Islamic jurist ('' faqih'') in response to a question posed by a private individual, judge or government. A jurist issuing fatwas is called a ''mufti'', ...

s that state that either the changing of religion is not punishable or is only punishable under restricted circumstances.

According to Yohanan Friedmann

Yohanan Friedmann (; born 1936) is an Israeli scholar of Islamic studies.

Biography

Friedmann was born in Zákamenné, Czechoslovakia and immigrated to Israel with his parents in 1949. He attended high school at the Reali School in Haifa (194 ...

, "The real predicament facing modern Muslims with liberal convictions is not the existence of stern laws against apostasy in medieval Muslim books of law, but rather the fact that accusations of apostasy and demands to punish it are heard time and again from radical elements in the contemporary Islamic world."Yohanan Friedmann, ''Tolerance and Coercion in Islam'', Cambridge University Press, p. 5

Sadakat Kadri

Sadakat Kadri (born 1964 in London) is a lawyer, author, travel writer and journalist. One of his foremost roles as a barrister was to assist in the prosecution of former Malawian president Hastings Banda. As a member of the New York Bar he has ...

noted that "state officials could not punish an unmanifested belief even if they wanted to".

The kind of apostasy which the jurists generally deemed punishable was of the political kind, although there were considerable legal differences of opinion on this matter.Asma Afsaruddin

Asma Afsaruddin (born 1958) is an American scholar of Islamic studies and Professor in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures at Indiana University in Bloomington.

Biography

She was an associate professor in Arabic and Islamic s ...

(2013), ''Striving in the Path of God: Jihad and Martyrdom in Islamic Thought'', p. 242. Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the publishing house of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world. Its first book was printed in Oxford in 1478, with the Press officially granted the legal right to print books ...

. .

Wael Hallaq

Wael B. Hallaq () is a Palestinian-Canadian scholar of Islamic studies and the Avalon Foundation Professor in the Humanities at Columbia University, where he has been teaching ethics, law, and political thought since 2009. He is considered a lea ...

states that " na culture whose lynchpin is religion, religious principles and religious morality, apostasy is in some way equivalent to high treason in the modern nation-state".

Also Bernard Lewis

Bernard Lewis, (31 May 1916 – 19 May 2018) was a British-American historian specialized in Oriental studies. He was also known as a public intellectual and political commentator. Lewis was the Cleveland E. Dodge Professor Emeritus of Near ...

consider the apostasy as a treason and "a withdrawal, a denial of allegiance as well as of religious belief and loyalty".

The English historian C. E. Bosworth

Clifford Edmund Bosworth FBA (29 December 1928 – 28 February 2015) was an English historian and Orientalist, specialising in Arabic and Iranian studies.

Life

Bosworth was born on 29 December 1928 in Sheffield, West Riding of Yorkshire (now ...

suggests the traditional view of apostasy hampered the development of Islamic learning, like philosophy and natural science, "out of fear that these could evolve into potential toe-holds for kufr

''Kāfir'' (; , , or ; ; or ) is an Arabic-language term used by Muslims to refer to a non-Muslim, more specifically referring to someone who disbelieves in the Islamic God, denies his authority, and rejects the message of Islam a ...

, those people who reject God."

While in 13 Muslim-majority countries atheism is punishable by death,

according to legal historian Sadakat Kadri

Sadakat Kadri (born 1964 in London) is a lawyer, author, travel writer and journalist. One of his foremost roles as a barrister was to assist in the prosecution of former Malawian president Hastings Banda. As a member of the New York Bar he has ...

, executions were rare because "it was widely believed" that any accused apostate "who repented by articulating the ''shahada

The ''Shahada'' ( ; , 'the testimony'), also transliterated as ''Shahadah'', is an Islamic oath and creed, and one of the Five Pillars of Islam and part of the Adhan. It reads: "I bear witness that there is no Ilah, god but God in Islam, God ...

''" (''LA ILAHA ILLALLAH'' "There is no God but God") "had to be forgiven" and their punishment delayed until after Judgement Day.

William Montgomery Watt

William Montgomery Watt (14 March 1909 – 24 October 2006) was a Scottish historian and orientalist. An Anglican priest, Watt served as Professor of Arabic and Islamic Studies at the University of Edinburgh from 1964 to 1979 and was also a prom ...

states that "In Islamic teaching, such penalties may have been suitable for the age in which Muhammad lived."

Islam and violence

Quran's teachings on matters of war and peace have become topics of heated discussion in recent years. On the one hand, some critics claim that certain verses of the Quran sanction military action against unbelievers as a whole both during the lifetime of Muhammad and after.''Warrant for terror: fatwās of radical Islam and the duty of jihād'', p. 68, Shmuel Bar, 2006

Quran's teachings on matters of war and peace have become topics of heated discussion in recent years. On the one hand, some critics claim that certain verses of the Quran sanction military action against unbelievers as a whole both during the lifetime of Muhammad and after.''Warrant for terror: fatwās of radical Islam and the duty of jihād'', p. 68, Shmuel Bar, 2006

Jihad

''Jihad'' (; ) is an Arabic word that means "exerting", "striving", or "struggling", particularly with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it encompasses almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with God in Islam, God ...

, an Islamic term

The following list consists of notable concepts that are derived from Islamic and associated cultural (Arab, Persian, Turkish) traditions, which are expressed as words in Arabic or Persian language. The main purpose of this list is to disambig ...

, is a religious duty of Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

s meaning "striving for the sake of God"., ''Jihad'', p. 571, ''Jihad'', p. 419John Esposito

John Louis Esposito (born May 19, 1940) is an American academic, professor of Middle Eastern studies, Middle Eastern and religious studies, and scholar of Islamic studies, who serves as Professor of Religion, International Affairs, and Islamic S ...

(2005), ''Islam: The Straight Path,'' p. 93

It is perceived in a military sense (not spiritual sense) by Bernard Lewis

Bernard Lewis, (31 May 1916 – 19 May 2018) was a British-American historian specialized in Oriental studies. He was also known as a public intellectual and political commentator. Lewis was the Cleveland E. Dodge Professor Emeritus of Near ...

and David Cook.Cook, David. ''Understanding Jihad''. University of California Press

The University of California Press, otherwise known as UC Press, is a publishing house associated with the University of California that engages in academic publishing. It was founded in 1893 to publish scholarly and scientific works by faculty ...

, 2005. Retrieved from Google Books

Google Books (previously known as Google Book Search, Google Print, and by its code-name Project Ocean) is a service from Google that searches the full text of books and magazines that Google has scanned, converted to text using optical charac ...

on 27 November 2011. , . Also Fawzy Abdelmalek and Dennis Prager

Dennis Mark Prager (; born August 2, 1948) is an American conservative radio talk show host and writer. He is the host of the nationally syndicated radio talk show ''The Dennis Prager Show''. In 2009, he co-founded PragerU, which primarily cre ...

argue against Islam being a religion of peace

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ''a ...

and not of violence. John R. Neuman, a scholar on religion, describes Islam as "a perfect anti-religion" and "the antithesis of Buddhism". Lawrence Wright

Lawrence Wright (born August 2, 1947) is an American writer and journalist, who is a staff writer for ''The New Yorker'' magazine, and fellow at the Center for Law and Security at the New York University School of Law. Wright is best known as ...

argued that role of Wahhabi

Wahhabism is an exonym for a Salafi revivalist movement within Sunni Islam named after the 18th-century Hanbali scholar Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. It was initially established in the central Arabian region of Najd and later spread to other ...