The Cossacks are a predominantly

East Slavic Eastern Christian

Eastern Christianity comprises Christianity, Christian traditions and Christian denomination, church families that originally developed during Classical antiquity, classical and late antiquity in the Eastern Mediterranean region or locations fu ...

people originating in the

Pontic–Caspian steppe

The Pontic–Caspian Steppe is a steppe extending across Eastern Europe to Central Asia, formed by the Caspian and Pontic steppes. It stretches from the northern shores of the Black Sea (the ''Pontus Euxinus'' of antiquity) to the northern a ...

of eastern

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

and

southern Russia

Southern Russia or the South of Russia ( rus, Юг России, p=juk rɐˈsʲiɪ) is a Colloquialism, colloquial term for the southernmost geographic portion of European Russia. The term is generally used to refer to the region of Russia's So ...

. Cossacks played an important role in defending the southern borders of

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

and

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

,

countering the

Crimean-Nogai raids, alongside economically developing

steppe regions north of the

Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

and around the

Azov Sea

The Sea of Azov is an inland shelf sea in Eastern Europe connected to the Black Sea by the narrow (about ) Strait of Kerch, and sometimes regarded as a northern extension of the Black Sea. The sea is bounded by Russia on the east, and by Ukr ...

. Historically, they were a semi-

nomad

Nomads are communities without fixed habitation who regularly move to and from areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the population of nomadic pa ...

ic and semi-militarized people, who, while under the nominal

suzerainty

A suzerain (, from Old French "above" + "supreme, chief") is a person, state (polity)">state or polity who has supremacy and dominant influence over the foreign policy">polity.html" ;"title="state (polity)">state or polity">state (polity)">st ...

of various Eastern European states at the time, were allowed a great degree of self-governance in exchange for military service. Although numerous linguistic and religious groups came together to form the Cossacks, most of them coalesced and became

East Slavic–speaking

Orthodox Christians.

The rulers of the

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

and

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

endowed Cossacks with certain special privileges in return for the military duty to serve in the irregular troops:

Zaporozhian Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks (in Latin ''Cossacorum Zaporoviensis''), also known as the Zaporozhian Cossack Army or the Zaporozhian Host (), were Cossacks who lived beyond (that is, downstream from) the Dnieper Rapids. Along with Registered Cossa ...

were mostly infantry soldiers, using

war wagon

A war wagon is any of several historical types of early fighting vehicle involving an armed or armored animal-drawn cart or wagon.

China

One of the earliest example of using conjoined wagons in warfare as fortification is described in the Chine ...

s, while

Don Cossacks

Don Cossacks (, ) or Donians (, ), are Cossacks who settled along the middle and lower Don River (Russia), Don. Historically, they lived within the former Don Cossack Host (, ), which was either an independent or an autonomous democratic rep ...

were mostly cavalry soldiers. The various Cossack groups were organized along military lines, with large autonomous groups called

hosts

A host is a person responsible for guests at an event or for providing hospitality during it.

Host may also refer to:

Places

* Host, Pennsylvania, a village in Berks County

* Host Island, in the Wilhelm Archipelago, Antarctica

People

* ...

. Each host had a territory consisting of affiliated villages called

stanitsa

A stanitsa or stanitza ( ; ), also spelled stanycia ( ) or stanica ( ), was a historical administrative unit of a Cossack host, a type of Cossack polity that existed in the Russian Empire.

Etymology

The Russian word is the diminutive of the word ...

s.

They inhabited sparsely populated areas in the

Dnieper

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

,

Don,

Terek, and

Ural river basins, and played an important role in the historical and cultural development of both Ukraine and parts of Russia.

The Cossack way of life persisted via both direct descendants and acquired ideals in other nations into the twentieth century, though the sweeping societal changes of the

Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

disrupted Cossack society as much as any other part of Russia; many Cossacks migrated to other parts of Europe following the establishment of the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, while others remained and assimilated into the Communist state. Cohesive Cossack-based units were organized and many fought for both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

After World War II, the Soviet Union disbanded the Cossack units within the

Soviet Army

The Soviet Ground Forces () was the land warfare service branch of the Soviet Armed Forces from 1946 to 1992. It was preceded by the Red Army.

After the Soviet Union ceased to exist in December 1991, the Ground Forces remained under th ...

, leading to the suppression of many Cossack traditions during the rule of

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

and his successors. However, during the

Perestroika

''Perestroika'' ( ; rus, перестройка, r=perestrojka, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg, links=no) was a political reform movement within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s, widely associ ...

era in the late 1980s, descendants of Cossacks began to revive their national traditions. In 1988, the Soviet Union enacted a law permitting the re-establishment of former Cossack hosts and the formation of new ones. Throughout the 1990s, numerous regional authorities consented to delegate certain local administrative and policing responsibilities to these reconstituted Cossack hosts.

Between 3.5 and 5 million people associate themselves with the Cossack

cultural identity

Cultural identity is a part of a person's identity (social science), identity, or their self-conception and self-perception, and is related to nationality, ethnicity, religion, social class, generation, Locality (settlement), locality, gender, o ...

across the world even though the majority, have little to no connection to the original Cossack people because cultural ideals and legacy changed greatly with time.

Cossack organizations operate in

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

,

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

,

Belarus

Belarus, officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Belarus spans an a ...

,

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a landlocked country primarily in Central Asia, with a European Kazakhstan, small portion in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the Kazakhstan–Russia border, north and west, China to th ...

,

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

, and the

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

.

Etymology

Max Vasmer

Max Julius Friedrich Vasmer (; ; 28 February 1886 – 30 November 1962) was a Russian and German linguist. He studied problems of etymology in Indo-European, Finno-Ugric and Turkic languages and worked on the history of Slavic, Baltic, ...

's etymological dictionary traces the name to the Tatar

Turkic word , , in which ''cosac'' meant 'free man' but also 'conqueror'. The ethnonym ''

Kazakh'' is from the same

Turkic root.

In written sources, the name is first

attested in the ''

Codex Cumanicus

The Codex Cumanicus is a linguistic manual of the Middle Ages, designed to help Catholic missionaries communicate with the Cumans, a nomadic Turkic people. It is currently housed in the Library of St. Mark, in Venice (BNM ms Lat. Z. 549 (=159 ...

'' from the 13th century. In

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Culture, language and peoples

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

* ''English'', an Amish ter ...

, ''Cossack'' is first attested in 1590.

[

]

History

Early history

The origins of the Cossacks are disputed. Originally, the term referred to semi-independent

The origins of the Cossacks are disputed. Originally, the term referred to semi-independent Tatar

Tatar may refer to:

Peoples

* Tatars, an umbrella term for different Turkic ethnic groups bearing the name "Tatar"

* Volga Tatars, a people from the Volga-Ural region of western Russia

* Crimean Tatars, a people from the Crimea peninsula by the B ...

groups ('' qazaq'' or "free men") who inhabited the Pontic–Caspian steppe

The Pontic–Caspian Steppe is a steppe extending across Eastern Europe to Central Asia, formed by the Caspian and Pontic steppes. It stretches from the northern shores of the Black Sea (the ''Pontus Euxinus'' of antiquity) to the northern a ...

, north of the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

near the Dnieper River

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

. By the end of the 15th century, the term was also applied to Slavic peasants who had fled to the devastated regions along the lower Dnieper and Don River

The Don () is the fifth-longest river in Europe. Flowing from Central Russia to the Sea of Azov in Southern Russia, it is one of Russia's largest rivers and played an important role for traders from the Byzantine Empire.

Its basin is betwee ...

s, where they established their self-governing communities. Until at least the 1630s, these Cossack groups remained ethnically and religiously open to virtually anybody, although the Slavic element predominated. There were several major Cossack host

A Cossack host (; , ''kazachye voysko''), sometimes translated as Cossack army, was an administrative subdivision of Cossacks in the Russian Empire. Earlier the term ''voysko'' ( host, in a sense as a doublet of ''guest'') referred to Cossack o ...

s in the 16th century: near the Dnieper, Don, Volga

The Volga (, ) is the longest river in Europe and the longest endorheic basin river in the world. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catchment ...

and Ural River

The Ural, also known as the Yaik , is a river flowing through Russia and Kazakhstan in the continental border between Europe and Asia. It originates in the southern Ural Mountains and discharges into the Caspian Sea. At , it is the third-longes ...

s; the Greben Cossacks in Caucasia; and the Zaporozhian Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks (in Latin ''Cossacorum Zaporoviensis''), also known as the Zaporozhian Cossack Army or the Zaporozhian Host (), were Cossacks who lived beyond (that is, downstream from) the Dnieper Rapids. Along with Registered Cossa ...

, mainly west of the Dnieper.Brodnici

The Brodnici (, ) were a tribe of disputed origin.

Etymology

In some opinions, the name, as used by foreign chronicles, means a person in charge of a ford (water crossing) in Slavic language (cf. Slavic ''brodŭ''). The probable reason for the n ...

and Berladnici (which had a Romanian origin with large Slavic influences) began to settle in the lower reaches of major rivers such as the Don and the Dnieper

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

after the demise of the Khazars

The Khazars ; 突厥可薩 ''Tūjué Kěsà'', () were a nomadic Turkic people who, in the late 6th century CE, established a major commercial empire covering the southeastern section of modern European Russia, southern Ukraine, Crimea, a ...

. Their arrival was probably not before the 13th century, when the Mongols

Mongols are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, China ( Inner Mongolia and other 11 autonomous territories), as well as the republics of Buryatia and Kalmykia in Russia. The Mongols are the principal member of the large family o ...

broke the power of the Cumans

The Cumans or Kumans were a Turkic people, Turkic nomadic people from Central Asia comprising the western branch of the Cumania, Cuman–Kipchak confederation who spoke the Cuman language. They are referred to as Polovtsians (''Polovtsy'') in Ru ...

, who had assimilated the previous population on that territory. It is known that new settlers inherited a lifestyle that long pre-dated their presence, including from that of the Cumans

The Cumans or Kumans were a Turkic people, Turkic nomadic people from Central Asia comprising the western branch of the Cumania, Cuman–Kipchak confederation who spoke the Cuman language. They are referred to as Polovtsians (''Polovtsy'') in Ru ...

and the Circassia

Circassia ( ), also known as Zichia, was a country and a historical region in . It spanned the western coastal portions of the North Caucasus, along the northeastern shore of the Black Sea. Circassia was conquered by the Russian Empire during ...

n Kassaks.Oleshky

Oleshky (, ), previously known as Tsiurupynsk from 1928 to 2016, is a List of cities in Ukraine, city in Kherson Raion, Kherson Oblast, southern Ukraine, located on the left bank of the Dnieper River with the town of Solontsi, Kherson Raion, So ...

, dating back to the 11th century.

Early "Proto-Cossack" groups are generally reported to have come into existence within what is now Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

in the 13th century as the influence of Cumans grew weaker, although some have ascribed their origins to as early as the mid-8th century.[Vasili Glazkov (Wasili Glaskow), ''History of the Cossacks'', p. 3, Robert Speller & Sons, New York, Vasili Glazkov claims that the data of ]Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

ian and Arab

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of years ...

historians support that. According to this view, by 1261, Cossacks lived in the area between the rivers Dniester

The Dniester ( ) is a transboundary river in Eastern Europe. It runs first through Ukraine and then through Moldova (from which it more or less separates the breakaway territory of Transnistria), finally discharging into the Black Sea on Uk ...

and Volga

The Volga (, ) is the longest river in Europe and the longest endorheic basin river in the world. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catchment ...

as described for the first time in Russian chronicles. Some historians suggest that the Cossack people were of mixed ethnic origin, descending from East Slavs

The East Slavs are the most populous subgroup of the Slavs. They speak the East Slavic languages, and formed the majority of the population of the medieval state Kievan Rus', which they claim as their cultural ancestor.John Channon & Robert Huds ...

, Turks

Turk or Turks may refer to:

Communities and ethnic groups

* Turkish people, or the Turks, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

* Turkish citizen, a citizen of the Republic of Turkey

* Turkic peoples, a collection of ethnic groups who speak Turkic lang ...

, Tatar

Tatar may refer to:

Peoples

* Tatars, an umbrella term for different Turkic ethnic groups bearing the name "Tatar"

* Volga Tatars, a people from the Volga-Ural region of western Russia

* Crimean Tatars, a people from the Crimea peninsula by the B ...

s, and others who settled or passed through the vast Steppe.Cumans

The Cumans or Kumans were a Turkic people, Turkic nomadic people from Central Asia comprising the western branch of the Cumania, Cuman–Kipchak confederation who spoke the Cuman language. They are referred to as Polovtsians (''Polovtsy'') in Ru ...

of Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

, who had lived there long before the Mongol invasion.Serhii Plokhy

Serhii Mykolayovych Plokhy (; born 23 May 1957) is a historian and author. He is the Mykhailo Hrushevsky professor of Ukrainian history at Harvard University, where he also serves as the director of the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute.

E ...

the first Cossacks were of Turkic rather than Slavic stock. Christoph Baumer

Christoph Baumer (born June 23, 1952) is a Switzerland, Swiss explorer and historian of Central Asia. Starting in 1984, he has conducted explorations in Central Asia, China, Tibet and the Caucasus, the results of which have been published in num ...

states that predecessor from the thirteenth century onward were mainly of Turkic stock, but from the sixteenth century the Cossack were increasingly joined by Slavs such as Russians and Poles, Balto-slavic

The Balto-Slavic languages form a branch of the Indo-European languages, Indo-European family of languages, traditionally comprising the Baltic languages, Baltic and Slavic languages. Baltic and Slavic languages share several linguistic traits ...

Lithuanians

Lithuanians () are a Balts, Baltic ethnic group. They are native to Lithuania, where they number around 2,378,118 people. Another two million make up the Lithuanian diaspora, largely found in countries such as the Lithuanian Americans, United Sta ...

and people from today's Ukraine, thus becoming a Slav-Tatar ethnic hybrid. Hypothesis of the non-Slavic origin of the Zaporozhian, Don and Kuban Cossacks

Kuban Cossacks (; ), or Kubanians (, ''kubantsy''; , ''kubantsi''), are Cossacks who live in the Kuban region of Russia. Most of the Kuban Cossacks are descendants of different major groups of Cossacks who were re-settled to the western Norther ...

is rejected by the low levels to absence of Caucasian and Asian component in the gene pool of these groups, with exception of the Terek Cossacks

The Terek Cossack Host was a Cossack host created in 1577 from free Cossacks who resettled from the Volga to the Terek River. The local aboriginal Terek Cossacks joined this Cossack host later. In 1792 it was included in the Caucasus Line Co ...

who lean towards some North Caucasian groups, likely as a result of the assimilation of these populations into Terek Host.

As the grand duchies of Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

and Lithuania

Lithuania, officially the Republic of Lithuania, is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, bordered by Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east and south, P ...

grew in power, new political entities appeared in the region. These included Moldavia

Moldavia (, or ; in Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, Romanian Cyrillic: or ) is a historical region and former principality in Eastern Europe, corresponding to the territory between the Eastern Carpathians and the Dniester River. An initially in ...

and the Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Khanate, self-defined as the Throne of Crimea and Desht-i Kipchak, and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary, was a Crimean Tatars, Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to 1783, the longest-lived of th ...

. In 1261, Slavic people living in the area between the Dniester

The Dniester ( ) is a transboundary river in Eastern Europe. It runs first through Ukraine and then through Moldova (from which it more or less separates the breakaway territory of Transnistria), finally discharging into the Black Sea on Uk ...

and the Volga

The Volga (, ) is the longest river in Europe and the longest endorheic basin river in the world. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catchment ...

were mentioned in Ruthenian chronicles. Historical records of the Cossacks before the 16th century are scant, as is the history of the Ukrainian lands in that period.

As early as the 15th century, a few individuals ventured into the Wild Fields

The Wild Fields is a historical term used in the Polish–Lithuanian documents of the 16th to 18th centuries to refer to the Pontic steppe in the territory of present-day Eastern and Southern Ukraine and Western Russia, north of the Black Sea ...

, the southern frontier regions of Ukraine separating Poland-Lithuania from the Crimean Khanate. These were short-term expeditions, to acquire the resources of what was a naturally rich and fertile region teeming with cattle, wild animals, and fish. This lifestyle, based on subsistence agriculture

Subsistence agriculture occurs when farmers grow crops on smallholdings to meet the needs of themselves and their families. Subsistence agriculturalists target farm output for survival and for mostly local requirements. Planting decisions occu ...

, hunting, and either returning home in the winter or settling permanently, came to be known as the Cossack way of life. Crimean–Nogai slave raids in Eastern Europe

Between 1441 and 1774, the Crimean Khanate and the Nogai Horde conducted Slave raiding, slave raids throughout lands primarily controlled by History of Russia, Russia and Polish–Lithuanian union, Poland–Lithuania. Concentrated in Eastern E ...

caused considerable devastation and depopulation in this area. The Tatar raids also played an important role in the development of the Cossacks.

In the 15th century, Cossack society was described as a loose

In the 15th century, Cossack society was described as a loose federation

A federation (also called a federal state) is an entity characterized by a political union, union of partially federated state, self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a #Federal governments, federal government (federalism) ...

of independent communities, which often formed local armies and were entirely independent from neighboring states such as Poland, the Grand Duchy of Moscow, and the Crimean Khanate. According to Mykhailo Hrushevsky

Mykhailo Serhiiovych Hrushevsky (; – 24 November 1934) was a Ukrainian academician, politician, historian and statesman who was one of the most important figures of the Ukrainian national revival of the early 20th century. Hrushevsky is ...

, the first mention of Cossacks dates back to the 14th century, although the reference was to people who were either Turkic or of undefined origin. Hrushevsky states that the Cossacks may have descended from the long-forgotten Antes, or from groups from the Berlad territory of the Brodnici

The Brodnici (, ) were a tribe of disputed origin.

Etymology

In some opinions, the name, as used by foreign chronicles, means a person in charge of a ford (water crossing) in Slavic language (cf. Slavic ''brodŭ''). The probable reason for the n ...

in present-day Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

, then a part of the Grand Duchy of Halych. There, the Cossacks may have served as self-defence formations, organized to defend against raids conducted by neighbors.

The first international mention of Cossacks was in 1492, when Crimean

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrai ...

Khan Meñli I Giray

Meñli I GirayCrimean Tatar language, Crimean Tatar, Ottoman Turkish and (1445–1515) was thrice the List of Crimean khans, khan of the Crimean Khanate (1466, 1469–1475, 1478–1515) and the sixth son of Hacı I Giray.

Biography

Stru ...

complained to Grand Duke of Lithuania Alexander Jagiellon

Alexander Jagiellon (; ; 5 August 1461 – 19 August 1506) was Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1492 and King of Poland from 1501 until his death in 1506. He was the fourth son of Casimir IV and a member of the Jagiellonian dynasty. Alexander was el ...

that his Cossack subjects from Kiev and Cherkasy had pillaged a Crimean Tatar ship: the duke ordered his "Ukrainian" (meaning borderland) officials to investigate, execute the guilty, and give their belongings to the khan. Sometime in the 16th century, there appeared the old Ukrainian ''Ballad of Cossack Holota'', about a Cossack near Kiliya

Kiliia or Kilia (, ; ; ) is a city in Izmail Raion, Odesa Oblast, southwestern Ukraine. It hosts the administration of Kiliia urban hromada, one of the hromadas of Ukraine. Kiliia is located in the Danube Delta, in the historic Bessarabian dist ...

.

In the 16th century, these Cossack societies merged into two independent territorial organizations, as well as other smaller, still-detached groups:

* The Cossacks of Zaporizhzhia

Zaporizhzhia, formerly known as Aleksandrovsk or Oleksandrivsk until 1921, is a city in southeast Ukraine, situated on the banks of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. It is the Capital city, administrative centre of Zaporizhzhia Oblast. Zaporizhzhia ...

, centered on the lower bends of the Dnieper, in the territory of modern Ukraine, with the fortified capital of Zaporozhian Sich

The Zaporozhian Sich (, , ; also ) was a semi-autonomous polity and proto-state of Zaporozhian Cossacks that existed between the 16th to 18th centuries, for the latter part of that period as an autonomous stratocratic state within the Cossa ...

. They were given significant autonomous privileges, operating as an autonomous state (the Zaporozhian Host) within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, by a treaty with Poland in 1649.

*The Don Cossack State, on the River Don. Its capital was initially Razdory, then it was moved to Cherkassk

Starocherkasskaya (), formerly Cherkassk (), is a rural locality (a ''stanitsa'') in Aksaysky District of Rostov Oblast, Russia, with origins dating from the late 16th century. It is located on the right bank of the Don River approximately u ...

, and later to Novocherkassk

Novocherkassk () is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city in Rostov Oblast, Russia, located near the confluence of the Tuzlov and Aksay Rivers, the latter a distributary of the Don (river), Don River. Novocherkassk is best known as the ...

.

There are also references to the less well-known Tatar

Tatar may refer to:

Peoples

* Tatars, an umbrella term for different Turkic ethnic groups bearing the name "Tatar"

* Volga Tatars, a people from the Volga-Ural region of western Russia

* Crimean Tatars, a people from the Crimea peninsula by the B ...

Cossacks, including the Nağaybäklär and Meshchera

The Meshchera or Meshchyora () were a Finno-Ugric tribe in the Volga region between the Oka River and the Klyazma river, today called the Meshchera Lowlands, who assimilated with the neighbouring tribes around the 16th century.

History

The f ...

-speaking Volga Finns

The Volga Finns are a historical group of peoples living in the vicinity of the Volga, who speak Uralic languages. Their modern representatives are the Mari people, the Erzya and the Moksha (commonly grouped together as Mordvins) as well as ...

, of whom Sary Azman was the first Don ataman

Ataman (variants: ''otaman'', ''wataman'', ''vataman''; ; ) was a title of Cossack and haidamak leaders of various kinds. In the Russian Empire, the term was the official title of the supreme military commanders of the Cossack armies. The Ukra ...

. These groups were assimilated by the Don Cossacks, but had their own irregular Bashkir and Meshchera Host up to the end of the 19th century. The Kalmyk and Buryat Cossacks also deserve mention.

Later history

The Zaporizhian Sich

A sich (), was an administrative and military centre of the Zaporozhian Cossacks. The word ''sich'' derives from the Ukrainian verb , "to chop" – with the implication of clearing a forest for an encampment or of building a fortification with t ...

became a vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain ...

polity

A polity is a group of people with a collective identity, who are organized by some form of political Institutionalisation, institutionalized social relations, and have a capacity to mobilize resources.

A polity can be any group of people org ...

of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

during feudal times. Under increasing pressure from the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, in the mid-17th century the Sich declared an independent Cossack Hetmanate

The Cossack Hetmanate (; Cossack Hetmanate#Name, see other names), officially the Zaporozhian Host (; ), was a Ukrainian Cossacks, Cossack state. Its territory was located mostly in central Ukraine, as well as in parts of Belarus and southwest ...

. The Hetmanate was initiated by a rebellion under Bohdan Khmelnytsky

Zynoviy Bohdan Mykhailovych Khmelnytsky of the Abdank coat of arms (Ruthenian language, Ruthenian: Ѕѣнові Богданъ Хмелнiцкiи; modern , Polish language, Polish: ; 15956 August 1657) was a Ruthenian nobility, Ruthenian noble ...

against Polish and Catholic domination, known as the Khmelnytsky Uprising

The Khmelnytsky Uprising, also known as the Cossack–Polish War, Khmelnytsky insurrection, or the National Liberation War, was a Cossack uprisings, Cossack rebellion that took place between 1648 and 1657 in the eastern territories of the Poli ...

. Afterwards, the (1654) brought most of the Cossack state under Russian rule. The Sich, with its lands, became an autonomous region under the Russian protectorate.

The Don Cossack Army, an autonomous military state formation of the Don Cossacks under the citizenship of the Moscow State in the Don region in 1671–1786, began a systematic conquest and colonization of lands to secure the borders on the Volga

The Volga (, ) is the longest river in Europe and the longest endorheic basin river in the world. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catchment ...

, the whole of Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

(see Yermak Timofeyevich

Yermak Timofeyevich (, ; 1532 (supposedly) – August 5 or 6, 1585) was a Cossack ataman who started the Russian conquest of Siberia during the reign of the Russian tsar Ivan the Terrible. He is today a hero in Russian folklore and myths.

Ru ...

), and the Yaik (Ural) and Terek River

The Terek () is a major river in the Northern Caucasus. It originates in the Mtskheta-Mtianeti region of Georgia and flows through North Caucasus region of Russia into the Caspian Sea. It rises near the juncture of the Greater Caucasus ...

s. Cossack communities had developed along the latter two rivers well before the arrival of the Don Cossacks.

By the 18th century, Cossack hosts in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

occupied effective buffer zones on its borders. The expansionist ambitions of the Empire relied on ensuring Cossack loyalty, which caused tension given their traditional exercise of freedom, democracy, self-rule, and independence. Cossacks such as Stenka Razin

Stepan Timofeyevich Razin (, ; c. 1630 – ), known as Stenka Razin ( ), was a Don Cossack leader who led a major uprising against the nobility and tsarist bureaucracy in southern Russia in 1670–1671.

Early life

Razin's father, Timofey Ra ...

, Kondraty Bulavin

The Bulavin Rebellion or Astrakhan Revolt (; Восстание Булавина, ''Vosstaniye Bulavina'') was a war which took place in the years 1707 and 1708 between the Don Cossacks and the Tsardom of Russia. Kondraty Bulavin, a democratica ...

, Ivan Mazepa

Ivan Stepanovych Mazepa (; ; ) was the Hetman of the Zaporozhian Host and the Left-bank Ukraine in 1687–1708. The historical events of Mazepa's life have inspired Cultural legacy of Mazeppa, many literary, artistic and musical works. He was ...

and Yemelyan Pugachev

Yemelyan Ivanovich Pugachev (also spelled Pugachyov; ; ) was an ataman of the Yaik Cossacks and the leader of the Pugachev's Rebellion, a major popular uprising in the Russian Empire during the reign of Catherine the Great.

The son of a Do ...

led major anti-imperial wars and revolutions in the Empire in order to abolish slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

and harsh bureaucracy, and to maintain independence. The Empire responded with executions and tortures, the destruction of the western part of the Don Cossack Host during the Bulavin Rebellion

The Bulavin Rebellion or Astrakhan Revolt (; Восстание Булавина, ''Vosstaniye Bulavina'') was a war which took place in the years 1707 and 1708 between the Don Cossacks and the Tsardom of Russia. Kondraty Bulavin, a democratica ...

in 1707–1708, the destruction of Baturyn

Baturyn (, ) is a historic city in Chernihiv Oblast (province) of northern Ukraine. It is located in Nizhyn Raion (district) on the banks of the Seym River. It hosts the administration of Baturyn urban hromada, one of the hromadas of Ukraine. P ...

after Mazepa's rebellion in 1708, and the formal dissolution of the Lower Dnieper Zaporozhian Host after Pugachev's Rebellion

Pugachev's Rebellion (; also called the Peasants' War 1773–1775 or Cossack Rebellion) of 1773–1775 was the principal revolt in a series of popular rebellions that took place in the Russian Empire after Catherine II seized power in 1762. It ...

in 1775. After the Pugachev rebellion, the Empire renamed the Yaik Host, its capital, the Yaik Cossacks, and the Cossack town of Zimoveyskaya in the Don region to try to encourage the Cossacks to forget the men and their uprisings. It also formally dissolved the Lower Dnieper Zaporozhian Cossack Host, and destroyed their fortress on the Dnieper (the Sich itself). This may in part have been due to the participation of some Zaporozhian and other Ukrainian exiles in Pugachev's rebellion. During his campaign, Pugachev issued manifestos calling for restoration of all borders and freedoms of both the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Lower Dnieper (Nyzovyi in Ukrainian) Cossack Host under the joint protectorate of Russia and the Commonwealth.

By the end of the 18th century, Cossack nations had been transformed into a special military estate ( ''sosloviye''), "a military class". The Malorussian Cossacks (the former Registered Cossacks

Registered Cossacks (, ) comprised special Cossack units of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth army in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Registered Cossacks became a military formation of the Commonwealth army beginning in 1572 soon after the ...

also known as "Town Zaporozhian Host") were excluded from this transformation, but were promoted to membership of various civil estates or classes (often Russian nobility), including the newly created civil estate of Cossacks.

Under a semi-feudal system retained until the end of the Russian Empire, Cossack families received grants of land which they retained free of taxation, provided that commitments to perform military service were met. Typically a single father or son from each registered family would serve several years full-time with his Host before becoming a reservist liable for recall only in the event of emergency or general mobilisation. When joining his regiment a Cossack was required to bring his own horse, uniform clothing, and basic weaponry (sabres and lances) although the larger and more affluent Hosts might assist in sourcing these essentials. The Russian central government provided only firearms plus food and accommodation. Lacking horses, the poor served in the Cossack infantry and artillery. In the navy alone, Cossacks served with other peoples as the Russian navy had no Cossack ships and units. Cossack service was considered rigorous.

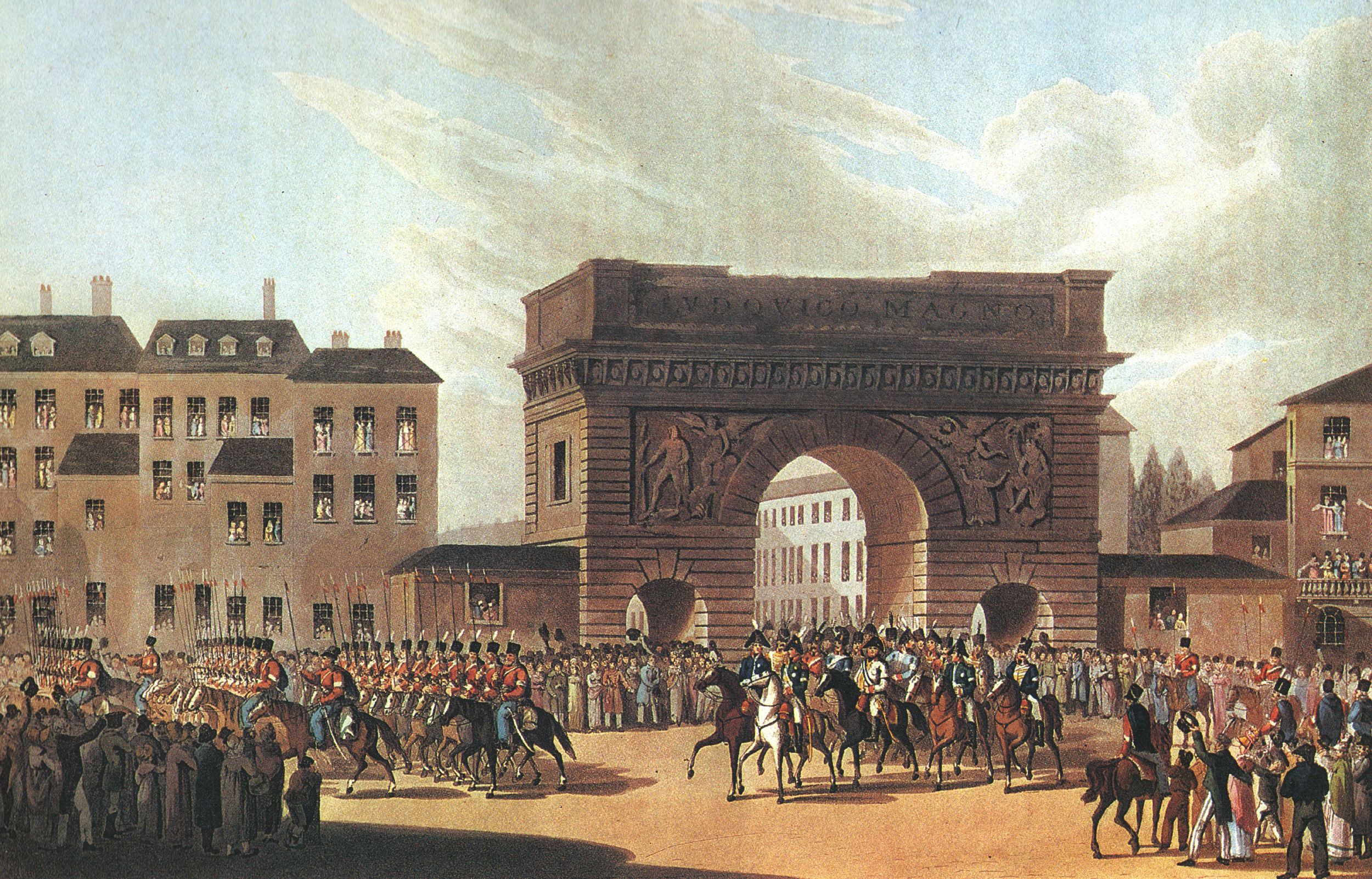

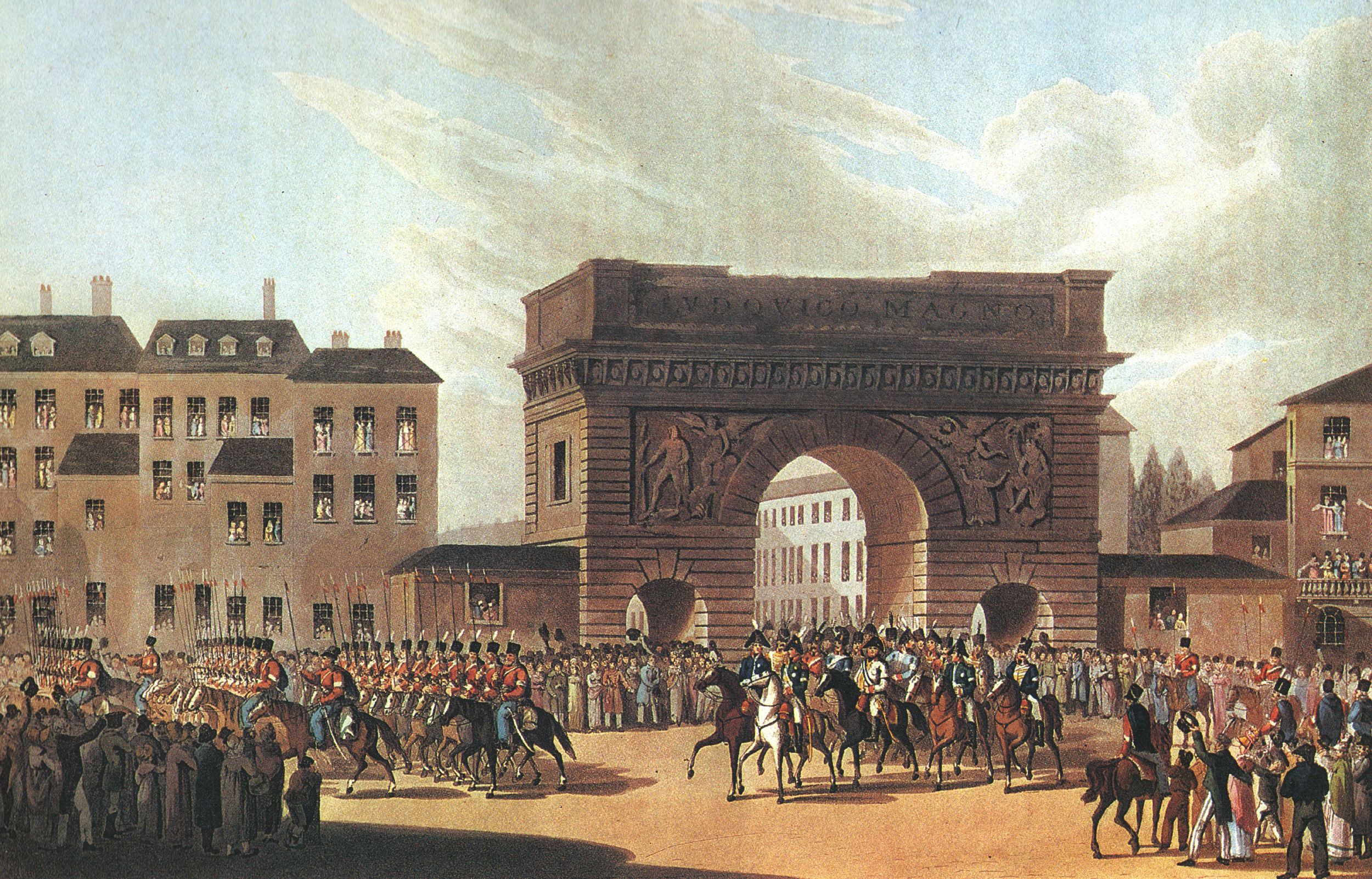

Cossack forces played an important role in Russia's wars of the 18th–20th centuries, including the Great Northern War

In the Great Northern War (1700–1721) a coalition led by the Tsardom of Russia successfully contested the supremacy of the Swedish Empire in Northern Europe, Northern, Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe. The initial leaders of the ant ...

, the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

, the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

, the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

, the Caucasus War

The Caucasian War () or the Caucasus War was a 19th-century military conflict between the Russian Empire and various peoples of the North Caucasus who resisted subjugation during the Russian conquest of the Caucasus. It consisted of a series o ...

, many Russo-Persian Wars

The Russo-Persian Wars ( ), or the Russo-Iranian Wars ( ), began in 1651 and continued intermittently until 1828. They consisted of five conflicts in total, each rooted in both sides' disputed governance of territories and countries in the Cauca ...

, many Russo-Turkish Wars

The Russo-Turkish wars ( ), or the Russo-Ottoman wars (), began in 1568 and continued intermittently until 1918. They consisted of twelve conflicts in total, making them one of the longest series of wars in the history of Europe. All but four of ...

, and the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Tsarist regime used Cossacks extensively to perform police service. Cossacks also served as border guards on national and internal ethnic borders, as had been the case in the Caucasus War.

During the Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

, Don and Kuban Cossacks

Kuban Cossacks (; ), or Kubanians (, ''kubantsy''; , ''kubantsi''), are Cossacks who live in the Kuban region of Russia. Most of the Kuban Cossacks are descendants of different major groups of Cossacks who were re-settled to the western Norther ...

were the first people to declare open war against the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

. In 1918, Russian Cossacks declared their complete independence, creating two independent states, the Don Republic

__NOTOC__

The Don Republic (), later known as the Almighty Don Host (), was an independent self-proclaimed anti-Bolshevik republic formed by the Armed Forces of South Russia on the territory of Don Cossacks against another self-proclaimed Don S ...

and the Kuban People's Republic

The Kuban People's Republic or Kuban National Republic (; , abbreviated as KPR or KNR, Cyrillic: КНР) was an anti-Bolshevik state during the Russian Civil War, comprising the territory of the Kuban region in Russia.

The republic was proclaim ...

, and the revived Hetmanate emerged in Ukraine. Cossack troops formed the effective core of the anti-Bolshevik White Army

The White Army, also known as the White Guard, the White Guardsmen, or simply the Whites, was a common collective name for the armed formations of the White movement and Anti-Sovietism, anti-Bolshevik governments during the Russian Civil War. T ...

, and Cossack republics became centers for the anti-Bolshevik White movement

The White movement,. The old spelling was retained by the Whites to differentiate from the Reds. also known as the Whites, was one of the main factions of the Russian Civil War of 1917–1922. It was led mainly by the Right-wing politics, right- ...

. With the victory of the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

, Cossack lands were subjected to decossackization

De-Cossackization () was the Bolshevik policy of systematic repression against the Cossacks in the former Russian Empire between 1919 and 1933, especially the Don and Kuban Cossacks in Russia, aimed at the elimination of the Cossacks as a dist ...

and the Holodomor

The Holodomor, also known as the Ukrainian Famine, was a mass famine in Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Soviet Ukraine from 1932 to 1933 that killed millions of Ukrainians. The Holodomor was part of the wider Soviet famine of 1930–193 ...

famine. As a result, during the Second World War, their loyalties were divided and both sides had Cossacks fighting in their ranks.

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union was formally dissolved as a sovereign state and subject of international law on 26 December 1991 by Declaration No. 142-N of the Soviet of the Republics of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. Declaration No. 142-Н of ...

, the Cossacks made a systematic return to Russia. Many took an active part in post-Soviet conflicts

This is a list of the crisis, crises and wars in the Post-Soviet states, countries of the former Soviet Union following its Dissolution of the Soviet Union, dissolution in 1991.

Those conflicts have different origins but two primary driving f ...

. In the 2002 Russian Census

The 2002 Russian census () was the first census of the Russian Federation since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, carried out on October 9 through October 16, 2002. It was carried out by the Russian Federal Service of State Statistics (Rossta ...

, 140,028 people reported their ethnicity

An ethnicity or ethnic group is a group of people with shared attributes, which they Collective consciousness, collectively believe to have, and long-term endogamy. Ethnicities share attributes like language, culture, common sets of ancestry, ...

as Cossack. There are Cossack organizations in Russia, Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a landlocked country primarily in Central Asia, with a European Kazakhstan, small portion in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the Kazakhstan–Russia border, north and west, China to th ...

, Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

, Belarus

Belarus, officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Belarus spans an a ...

, and the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

.

Ukrainian Cossacks

Zaporozhian Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks lived on the Pontic–Caspian steppe

The Pontic–Caspian Steppe is a steppe extending across Eastern Europe to Central Asia, formed by the Caspian and Pontic steppes. It stretches from the northern shores of the Black Sea (the ''Pontus Euxinus'' of antiquity) to the northern a ...

below the Dnieper Rapids (Ukrainian: ''za porohamy''), also known as the Wild Fields

The Wild Fields is a historical term used in the Polish–Lithuanian documents of the 16th to 18th centuries to refer to the Pontic steppe in the territory of present-day Eastern and Southern Ukraine and Western Russia, north of the Black Sea ...

. The group became well known, and its numbers increased greatly between the 15th and 17th centuries. The Zaporozhian Cossacks played an important role in European geopolitics

Geopolitics () is the study of the effects of Earth's geography on politics and international relations. Geopolitics usually refers to countries and relations between them, it may also focus on two other kinds of State (polity), states: ''de fac ...

, participating in a series of conflicts and alliances with the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

, Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. The Zaporozhians gained a reputation for their raids against the Ottoman Empire and its vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain ...

s, although they also sometimes plundered other neighbors. Their actions increased tension along the southern border of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Low-level warfare took place in those territories for most of the period of the Commonwealth (1569–1795).

Emergence

Prior to the formation of the Zaporozhian Sich

A sich (), was an administrative and military centre of the Zaporozhian Cossacks. The word ''sich'' derives from the Ukrainian verb , "to chop" – with the implication of clearing a forest for an encampment or of building a fortification with t ...

, Cossacks had usually been organized by Ruthenian boyar

A boyar or bolyar was a member of the highest rank of the feudal nobility in many Eastern European states, including Bulgaria, Kievan Rus' (and later Russia), Moldavia and Wallachia (and later Romania), Lithuania and among Baltic Germans. C ...

s, or princes of the nobility, especially various Lithuanian

Lithuanian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Lithuania, a country in the Baltic region in northern Europe

** Lithuanian language

** Lithuanians, a Baltic ethnic group, native to Lithuania and the immediate geographical region

** L ...

starosta

Starosta or starost (Cyrillic: ''старост/а'', Latin: ''capitaneus'', ) is a community elder in some Slavic lands.

The Slavic root of "starost" translates as "senior". Since the Middle Ages, it has designated an official in a leadersh ...

s. Merchants, peasants, and runaways from the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Muscovy Muscovy or Moscovia () is an alternative name for the Principality of Moscow (1263–1547) and the Tsardom of Russia (1547–1721).

It may also refer to:

*Muscovy Company, an English trading company chartered in 1555

*Muscovy duck (''Cairina mosch ...

, and Moldavia also joined the Cossacks.

The first recorded ''sich'' prototype was formed by the starosta of Cherkasy

Cherkasy (, ) is a city in central Ukraine. Cherkasy serves as the administrative centre of Cherkasy Oblast as well as Cherkasy Raion within the oblast. The city has a population of

Cherkasy is the cultural, educational and industrial centre ...

and Kaniv

Kaniv (, ) is a city in Cherkasy Raion, Cherkasy Oblast, central Ukraine. The city rests on the Dnieper River, and is one of the main inland river ports on the Dnieper. It is an urban hromada of Ukraine. Population:

Kaniv is a historical tow ...

, Dmytro Vyshnevetsky

Dmytro Ivanovych Vyshnevetsky (; ; ) was a Ruthenian magnate of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. He established the Zaporozhian Cossack stronghold on the Small Khortytsia Island. He was also known as ''Baida'' () in Ukrainian folk song ...

, who built a fortress on the island of Little Khortytsia

Khortytsia (, ) is the largest island on the Dnieper River, and is long and up to wide. The island forms part of the Khortytsia National Reserve. This historic site is located within the city limits of Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine.

The island has ...

on the banks of the Lower Dnieper

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

in 1552. The Zaporozhian Host adopted a lifestyle that combined the ancient Cossack order and habits with those of the Knights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem, commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), is a Catholic military order. It was founded in the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem in the 12th century and had headquarters there ...

.

The Cossack structure arose, in part, in response to the struggle against Tatar raids. Socio-economic developments in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth were another important factor in the growth of the Ukrainian Cossacks. During the 16th century, serfdom was imposed because of the favorable conditions for grain sales in Western Europe. This subsequently decreased the locals' land allotments and freedom of movement. In addition, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth government attempted to impose Catholicism, and to Polonize the local Ukrainian population. The basic form of resistance and opposition by the locals and burghers was flight and settlement in the sparsely populated steppe.

Relations with surrounding states

The major powers tried to exploit Cossack military power for their own purposes. In the 16th century, with the area of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth extending south, the Zaporozhian Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks (in Latin ''Cossacorum Zaporoviensis''), also known as the Zaporozhian Cossack Army or the Zaporozhian Host (), were Cossacks who lived beyond (that is, downstream from) the Dnieper Rapids. Along with Registered Cossa ...

were mostly, if tentatively, regarded by the Commonwealth as their subjects. Foreign and internal pressure on the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth led to the government making concessions to the Zaporozhian Cossacks. King Stephen Báthory

Stephen Báthory (; ; ; 27 September 1533 – 12 December 1586) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania (1576–1586) as well as Prince of Transylvania, earlier Voivode of Transylvania (1571–1576).

The son of Stephen VIII Báthory ...

granted them certain rights and freedoms in 1578, and they gradually began to create their foreign policy. They did so independently of the government, and often against its interests, as for example with their role in Moldavian affairs, and with the signing of a treaty with Emperor Rudolf II

Rudolf II (18 July 1552 – 20 January 1612) was Holy Roman Emperor (1576–1612), King of Hungary and Kingdom of Croatia (Habsburg), Croatia (as Rudolf I, 1572–1608), King of Bohemia (1575–1608/1611) and Archduke of Austria (1576–16 ...

in the 1590s.Registered Cossacks

Registered Cossacks (, ) comprised special Cossack units of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth army in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Registered Cossacks became a military formation of the Commonwealth army beginning in 1572 soon after the ...

formed a part of the Commonwealth army until 1699.

Around the end of the 16th century, increasing Cossack aggression strained relations between the Commonwealth and the Ottoman Empire. Cossacks had begun raiding Ottoman territories during the second part of the 16th century. The Polish government could not control them, but was held responsible as the men were nominally its subjects. In retaliation, Tatars

Tatars ( )[Tatar]

in the Collins English Dictionary are a group of Turkic peoples across Eas ...

living under Ottoman rule launched raids into the Commonwealth, mostly in the southeast territories. Cossack pirates responded by raiding wealthy trading port-cities in the heart of the Ottoman Empire, as these were just two days away by boat from the mouth of the Dnieper

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

river. In 1615 and 1625, Cossacks razed suburbs of Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

, forcing the Ottoman Sultan

The sultans of the Ottoman Empire (), who were all members of the Ottoman dynasty (House of Osman), ruled over the Boundaries between the continents, transcontinental empire from its perceived inception in 1299 to Dissolution of the Ottoman Em ...

to flee his palace. In 1637, the Zaporozhian Cossacks, joined by the Don Cossacks

Don Cossacks (, ) or Donians (, ), are Cossacks who settled along the middle and lower Don River (Russia), Don. Historically, they lived within the former Don Cossack Host (, ), which was either an independent or an autonomous democratic rep ...

, captured the strategic Ottoman fortress of Azov

Azov (, ), previously known as Azak ( Turki/ Kypchak: ),

is a town in Rostov Oblast, Russia, situated on the Don River just from the Sea of Azov, which derives its name from the town. The population is

History

Early settlements in the vici ...

, which guarded the Don.

The Zaporizhian Cossacks became particularly strong in the first quarter of the 17th century under the leadership of hetman Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny

Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny (; ; born – 20 April 1622) was a political and civic leader and member of the Ruthenian nobility, who served as Hetman of Zaporizhian Cossacks, Hetman of Zaporozhian Cossacks from 1616 to 1622. During his tenur ...

, who launched successful campaigns against the Tatars and Turks. Tsar Boris Godunov

Boris Feodorovich Godunov (; ; ) was the ''de facto'' regent of Russia from 1585 to 1598 and then tsar from 1598 to 1605 following the death of Feodor I, the last of the Rurik dynasty. After the end of Feodor's reign, Russia descended into t ...

had incurred the hatred of Ukrainian Cossacks by ordering the Don Cossacks to drive away from the Don all the Ukrainian Cossacks fleeing the failed uprisings of the 1590s. This contributed to the Ukrainian Cossacks' willingness to fight against him. In 1604, 2,000 Zaporizhian Cossacks fought on the side of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and their proposal for the Tsar ( Dmitri I), against the Muscovite army. By September 1604, Dmitri I had gathered a force of 2,500 men, of whom 1,400 were Cossacks. Two thirds of these "cossacks", however, were in fact Ukrainian civilians, only 500 being professional Ukrainian Cossacks. On July 4, 1610, 4,000 Ukrainian Cossacks fought in the Battle of Klushino

The Battle of Klushino, or the Battle of Kłuszyn, was fought on 4 July 1610, between forces of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Tsardom of Russia during the Polish–Russian War, part of Russia's Time of Troubles. The battle occu ...

, on the side of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. They helped to defeat a combined Muscovite-Swedish army and facilitate the occupation of Moscow from 1610 to 1611, riding into Moscow with Stanisław Żółkiewski

Stanisław Żółkiewski (; 1547 – 7 October 1620) was a Polish people, Polish szlachta, nobleman of the Lubicz coat of arms, a magnate, military commander, and Chancellor (Poland), Chancellor of the Polish Crown in the Polish–Lithuanian C ...

.

The final attempt by King Sigismund

Sigismund of Luxembourg (15 February 1368 – 9 December 1437) was Holy Roman Emperor from 1433 until his death in 1437. He was elected King of Germany (King of the Romans) in 1410, and was also King of Bohemia from 1419, as well as prince-elect ...

and Wladyslav to seize the throne of Muscovy was launched on April 6, 1617. Although Wladyslav was the nominal leader, it was Jan Karol Chodkiewicz

Jan Karol Chodkiewicz (; 1561 – 24 September 1621) was a Polish–Lithuanian identity, Polish–Lithuanian military commander of the Grand Ducal Lithuanian Army, who was from 1601 Field Hetman of Lithuania, and from 1605 Grand Hetman of Lit ...

who commanded the Commonwealth forces. By October, the towns of Dorogobuzh

Dorogobuzh (; Belarusian: Дарагабуж) is a historic town and the administrative center of Dorogobuzhsky District in Smolensk Oblast, Russia, straddling the Dnieper River and located east of Smolensk, the administrative center of th ...

and Vyazma

Vyazma () is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, town and the administrative center of Vyazemsky District, Smolensk Oblast, Vyazemsky District in Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the Vyazma River, about halfway between Smolensk, the ...

had surrendered. But a defeat, when the counterattack on Moscow by Chodkiewicz failed between Vyasma and Mozhaysk

MozhayskAlternative transliterations include ''Mozhaisk'', ''Mozhajsk'', ''Mozhaĭsk'', and ''Možajsk''. (, ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, town and the administrative center of Mozhaysky District, Moscow Oblast, Mozhaysky Distri ...

, prompted the Polish-Lithuanian army to retreat. In 1618, Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny continued his campaign against the Tsardom of Russia on behalf of the Cossacks and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Numerous Russian towns were sacked, including Livny

Livny (, ) is a town in Oryol Oblast, Russia. As of 2018, it had a population of 47,221. :ru:Ливны#cite note-2018AA-3

History

The town is believed to have originated in 1586 as Ust-Livny, a wooden fort on the bank of the Livenka River, ...

and Yelets

Yelets or Elets () is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city in Lipetsk Oblast, Russia, situated on the Bystraya Sosna River, which is a tributary of the Don River, Russia, Don. Population:

History

Yelets is the oldest center of the ...

. In September 1618, with Chodkiewicz, Konashevych-Sahaidachny laid siege to Moscow, but peace was secured.

Consecutive treaties between the Ottoman Empire and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth called for the governments to keep the Cossacks and Tatars in check, but neither enforced the treaties strongly. The Polish forced the Cossacks to burn their boats and stop raiding by sea, but the activity did not cease entirely. During this time, the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy, also known as Habsburg Empire, or Habsburg Realm (), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities (composite monarchy) that were ruled by the House of Habsburg. From the 18th century it is ...

sometimes covertly hired Cossack raiders against the Ottomans, to ease pressure on their own borders. Many Cossacks and Tatars developed longstanding enmity due to the losses of their raids. The ensuing chaos and cycles of retaliation often turned the entire southeastern Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth border into a low-intensity war zone. It catalyzed escalation of Commonwealth–Ottoman warfare, from the Moldavian Magnate Wars

The Moldavian Magnate Wars, or Moldavian Ventures, refer to the period at the end of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th century when the magnates of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth intervened in the affairs of Moldavia, clashing ...

(1593–1617) to the Battle of Cecora (1620)

The Battle of Cecora (also known as the ''Battle of Țuțora'') took place during the Polish–Ottoman War (1620–21) between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (aided by rebel Moldavian troops) and Ottoman forces (backed by Nogais), fough ...

, and campaigns in the Polish–Ottoman War of 1633–1634.

Conflict with Poland

Cossack numbers increased when the warriors were joined by peasants

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer

A farmer is a person engaged in agriculture, raising living organisms for food or raw materials. The term usually applies to people who do some combination of raising f ...

escaping serf

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed du ...

dom in Russia and dependence in the Commonwealth. Attempts by the ''szlachta

The ''szlachta'' (; ; ) were the nobility, noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Depending on the definition, they were either a warrior "caste" or a social ...

'' to turn the Zaporozhian Cossacks into peasants eroded the formerly strong Cossack loyalty towards the Commonwealth. The government constantly rebuffed Cossack ambitions for recognition as equal to the ''szlachta''. Plans for transforming the Polish–Lithuanian two-nation Commonwealth into a Polish–Lithuanian–Ruthenian Commonwealth made little progress, due to the unpopularity among the Ruthenian ''szlachta'' of the idea of Ruthenian Cossacks being equal to them and their elite becoming members of the ''szlachta''. The Cossacks' strong historic allegiance to the Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, officially the Orthodox Catholic Church, and also called the Greek Orthodox Church or simply the Orthodox Church, is List of Christian denominations by number of members, one of the three major doctrinal and ...

also put them at odds with officials of the Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

-dominated Commonwealth. Tensions increased when Commonwealth policies turned from relative tolerance to suppression of the Eastern Orthodox Church after the Union of Brest

The Union of Brest took place in 1595–1596 and represented an agreement by Eastern Orthodox Churches in the Ruthenian portions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth to accept the Pope's authority while maintaining Eastern Orthodox liturgical ...

. The Cossacks became strongly anti-Roman Catholic, an attitude that became synonymous with anti-Polish.Severyn Nalyvaiko

Severyn (Semerii) Nalyvaiko (, , in older historiography also ''Semen Nalewajko'', died 21 April 1597) was a leader of the Ukrainian Cossacks who became a hero of Ukrainian folklore. He led the failed Nalyvaiko Uprising against the Polish– ...

(1594–1596), Hryhorii Loboda (1596), Marko Zhmailo (1625), Taras Fedorovych

Taras Fedorovych (pseudonym, Taras Triasylo, Hassan Tarasa, Assan Trasso) (, ) (died after 1636) was a prominent leader of the Dnieper Cossacks, a popular Hetman (Cossack leader) elected by unregistered Cossacks.

Between 1629 and 1636, Fedorov ...

(1630), Ivan Sulyma (1635), Pavlo Pavliuk

Pavlo Pavliuk, or Pavlo Mikhnovych (; ; died 1638 in Warsaw) was a Colonel of Registered Cossacks (), who was elected as a hetman and led a Cossack-peasant uprising (the Pavliuk Uprising) in Left-bank Ukraine and Zaporizhia.

The uprising agains ...

and Dmytro Hunia (1637), and Yakiv Ostrianyn and Karpo Skydan (1638). All were brutally suppressed and ended by the Polish government. Cossack rebellions eventually culminated in the Khmelnytsky Uprising

The Khmelnytsky Uprising, also known as the Cossack–Polish War, Khmelnytsky insurrection, or the National Liberation War, was a Cossack uprisings, Cossack rebellion that took place between 1648 and 1657 in the eastern territories of the Poli ...

, led by the hetman of the Zaporizhian Sich, Bohdan Khmelnytsky

Zynoviy Bohdan Mykhailovych Khmelnytsky of the Abdank coat of arms (Ruthenian language, Ruthenian: Ѕѣнові Богданъ Хмелнiцкiи; modern , Polish language, Polish: ; 15956 August 1657) was a Ruthenian nobility, Ruthenian noble ...

.

Under Russian rule

The Zaporozhian Sich had its own authorities, its own "Lower" Zaporozhian Host, and its own land.

In 1775, the Lower Dnieper Zaporozhian Host was destroyed. Later, its high-ranking Cossack leaders were exiled to Siberia, its last chief, Petro Kalnyshevsky, becoming a prisoner of the

The Zaporozhian Sich had its own authorities, its own "Lower" Zaporozhian Host, and its own land.

In 1775, the Lower Dnieper Zaporozhian Host was destroyed. Later, its high-ranking Cossack leaders were exiled to Siberia, its last chief, Petro Kalnyshevsky, becoming a prisoner of the Solovetsky Islands

The Solovetsky Islands ( rus, Соловецкие острова, p=səlɐˈvʲetskʲɪj ɐstrɐˈva), or Solovki ( rus, Соловки, p=səlɐfˈkʲi), are an archipelago located in the Onega Bay of the White Sea, Russia. As an administrati ...

. Some Cossacks moved to the Danube Delta

The Danube Delta (, ; , ) is the second largest river delta in Europe, after the Volga Delta, and is the best preserved on the continent. Occurring where the Danube, Danube River empties into the Black Sea, most of the Danube Delta lies in Romania ...

region, where they established a new sich under Ottoman rule. To prevent further defection of Cossacks, the Russian government restored the special Cossack status of the majority of Zaporozhian Cossacks. This allowed them to unite in the Host of Loyal Zaporozhians, and later to reorganize into other hosts, of which the Black Sea Host

Black Sea Cossack Host (), also known as Chernomoriya (), was a Cossack host of the Russian Empire created in 1787 in southern Ukraine from former Zaporozhian Cossacks.Azarenkova et al., pp. 9ff. In the 1790s, the host was re-settled to the ...

was most important. Because of land scarcity resulting from the distribution of Zaporozhian Sich lands among landlords, they eventually moved on to the Kuban region.

The majority of Danubian Sich Cossacks moved first to the Azov region in 1828, and later joined other former Zaporozhian Cossacks in the Kuban region. Groups were generally identified by faith rather than language in that period, and most descendants of Zaporozhian Cossacks in the Kuban region are bilingual, speaking both Russian and Balachka

Balachka (, , ) is a Ukrainian dialect spoken in the Kuban and Don regions, where Ukrainian settlers used to live. It was strongly influenced by Cossack culture.

The term is derived from the Ukrainian term (), which colloquially means "to ...

, the local Kuban dialect of central Ukrainian. Their folklore is largely Ukrainian. The predominant view of ethnologists and historians is that its origins lie in the common culture dating back to the Black Sea Cossacks.

Cossack Hetmanate

Formation of the Cossack class in the Hetmanate

The waning loyalty of the Cossacks, and the ''

The waning loyalty of the Cossacks, and the ''szlachta

The ''szlachta'' (; ; ) were the nobility, noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Depending on the definition, they were either a warrior "caste" or a social ...

's'' arrogance towards them, resulted in several Cossack uprisings against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the early 17th century. Finally, the King's adamant refusal to accede to the demand to expand the Cossack Registry prompted the largest and most successful of these: the Khmelnytsky Uprising

The Khmelnytsky Uprising, also known as the Cossack–Polish War, Khmelnytsky insurrection, or the National Liberation War, was a Cossack uprisings, Cossack rebellion that took place between 1648 and 1657 in the eastern territories of the Poli ...

, that began in 1648. Some Cossacks, including the Polish ''szlachta'' in Ukraine, converted to Eastern Orthodoxy, divided the lands of the Ruthenian ''szlachta'', and became the Cossack ''szlachta''. The uprising was one of a series of catastrophic events for the Commonwealth, known as The Deluge, which greatly weakened the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and set the stage for its disintegration 100 years later.

Influential relatives of the Ruthenian and Lithuanian ''szlachta'' in Moscow helped to create the Russian–Polish alliance against Khmelnitsky's Cossacks, portrayed as rebels against order and against the private property of the Ruthenian Orthodox ''szlachta''. Don Cossacks' raids on Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

left Khmelnitsky without the aid of his usual Tatar allies. From the Russian perspective, the rebellion ended with the 1654 , in which, in order to overcome the Russian–Polish alliance against them, the Khmelnitsky Cossacks pledged their loyalty to the Russian Tsar

Tsar (; also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar''; ; ; sr-Cyrl-Latn, цар, car) is a title historically used by Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word '' caesar'', which was intended to mean ''emperor'' in the Euro ...

. In return, the Tsar guaranteed them his protection; recognized the Cossack ''starshyna

( rus, Старшина, p=stərʂɨˈna, a=Ru-старшина.ogg or ) is a senior military rank or designation in the military forces of some Slavic states, and a historical military designation. Depending on a country, it had different mean ...