Coral (AI) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Corals are colonial

differentiation in gene expressions

in their branch tips and bases that arose through developmental signaling pathways such as Hox,

BMP

etc. Scientists typically select ''Acropora'' as research models since they are the most diverse genus of hard coral, having over 120 species. Most species within this genus have polyps which are dimorphic: axial polyps grow rapidly and have lighter coloration, while radial polyps are small and are darker in coloration. In the ''Acropora'' genus, gamete synthesis and

mitotic cell proliferation

and skeleton deposition of the calcium carbonate via

differentially expressed (DE) signaling genes

ref name=":2" /> between both branch tips and bases. These processes lead t

colony differentiation

which is the most accurate distinguisher between coral species. In the Acropora genus, colony differentiation through up-regulation and down-regulation of DEs. Systematic studies of soft coral species have faced challenges due to a lack of

For most of their life corals are sessile animals of

For most of their life corals are sessile animals of

The polyps of stony corals have six-fold symmetry. In stony corals, the tentacles are cylindrical and taper to a point, but in soft corals they are pinnate with side branches known as pinnules. In some tropical species, these are reduced to mere stubs and in some, they are fused to give a paddle-like appearance.

Coral skeletons are biocomposites (mineral + organics) of calcium carbonate, in the form of calcite or aragonite. In scleractinian corals, "centers of calcification" and fibers are clearly distinct structures differing with respect to both morphology and chemical compositions of the crystalline units. The organic matrices extracted from diverse species are acidic, and comprise proteins, sulphated sugars and lipids; they are species specific. The soluble organic matrices of the skeletons allow to differentiate

The polyps of stony corals have six-fold symmetry. In stony corals, the tentacles are cylindrical and taper to a point, but in soft corals they are pinnate with side branches known as pinnules. In some tropical species, these are reduced to mere stubs and in some, they are fused to give a paddle-like appearance.

Coral skeletons are biocomposites (mineral + organics) of calcium carbonate, in the form of calcite or aragonite. In scleractinian corals, "centers of calcification" and fibers are clearly distinct structures differing with respect to both morphology and chemical compositions of the crystalline units. The organic matrices extracted from diverse species are acidic, and comprise proteins, sulphated sugars and lipids; they are species specific. The soluble organic matrices of the skeletons allow to differentiate

Corals predominantly reproduce sexually. About 25% of

Corals predominantly reproduce sexually. About 25% of

Environmental cues that influence the release of gametes into the water vary from species to species. The cues involve temperature change,

Environmental cues that influence the release of gametes into the water vary from species to species. The cues involve temperature change,

Within a coral head, the genetically identical polyps reproduce asexually, either by

Within a coral head, the genetically identical polyps reproduce asexually, either by

Corals are one of the more common examples of an animal host whose symbiosis with microalgae can turn to

Corals are one of the more common examples of an animal host whose symbiosis with microalgae can turn to

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Studies have also suggested that resident bacteria, archaea, and fungi additionally contribute to nutrient and organic matter cycling within the coral, with viruses also possibly playing a role in structuring the composition of these members, thus providing one of the first glimpses at a multi-domain marine animal symbiosis. The

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

It is known that the coral's

It is known that the coral's

At certain times in the geological past, corals were very abundant. Like modern corals, their ancestors built reefs, some of which ended as great structures in

At certain times in the geological past, corals were very abundant. Like modern corals, their ancestors built reefs, some of which ended as great structures in

File:Syringoporid.jpg, Tabulate coral (a syringoporid); Boone limestone (Lower

Coral reefs are under stress around the world. In particular, coral mining,

Coral reefs are under stress around the world. In particular, coral mining,

NINO 3.4 SSTA

NINO 3.4 SSTA

time can be correlated to coral strontium/calcium and δ18O variations. To confirm the accuracy of the annual relationship between Sr/Ca and δ18O variations, a perceptible association to annual coral growth rings confirms the age conversion.

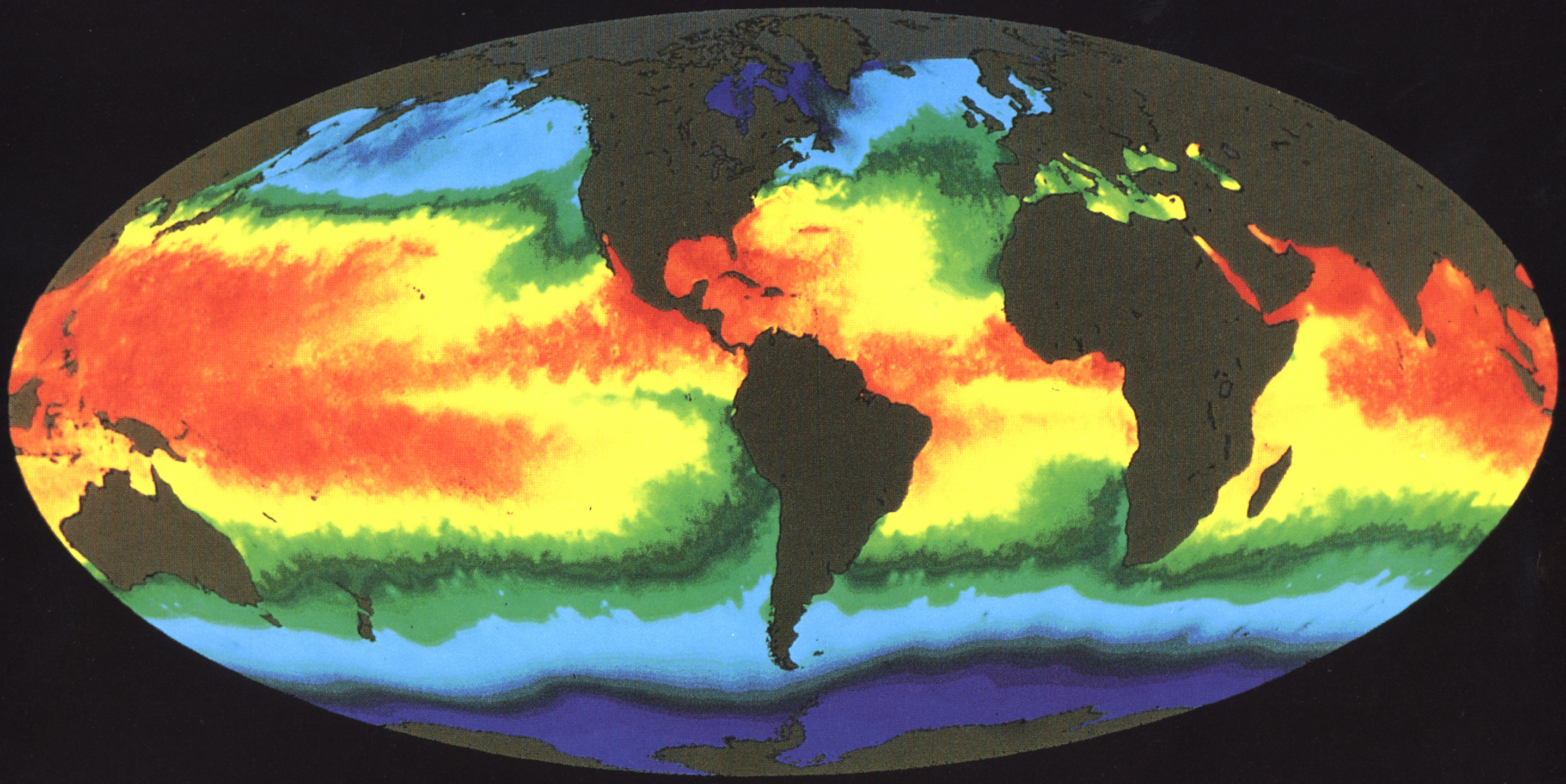

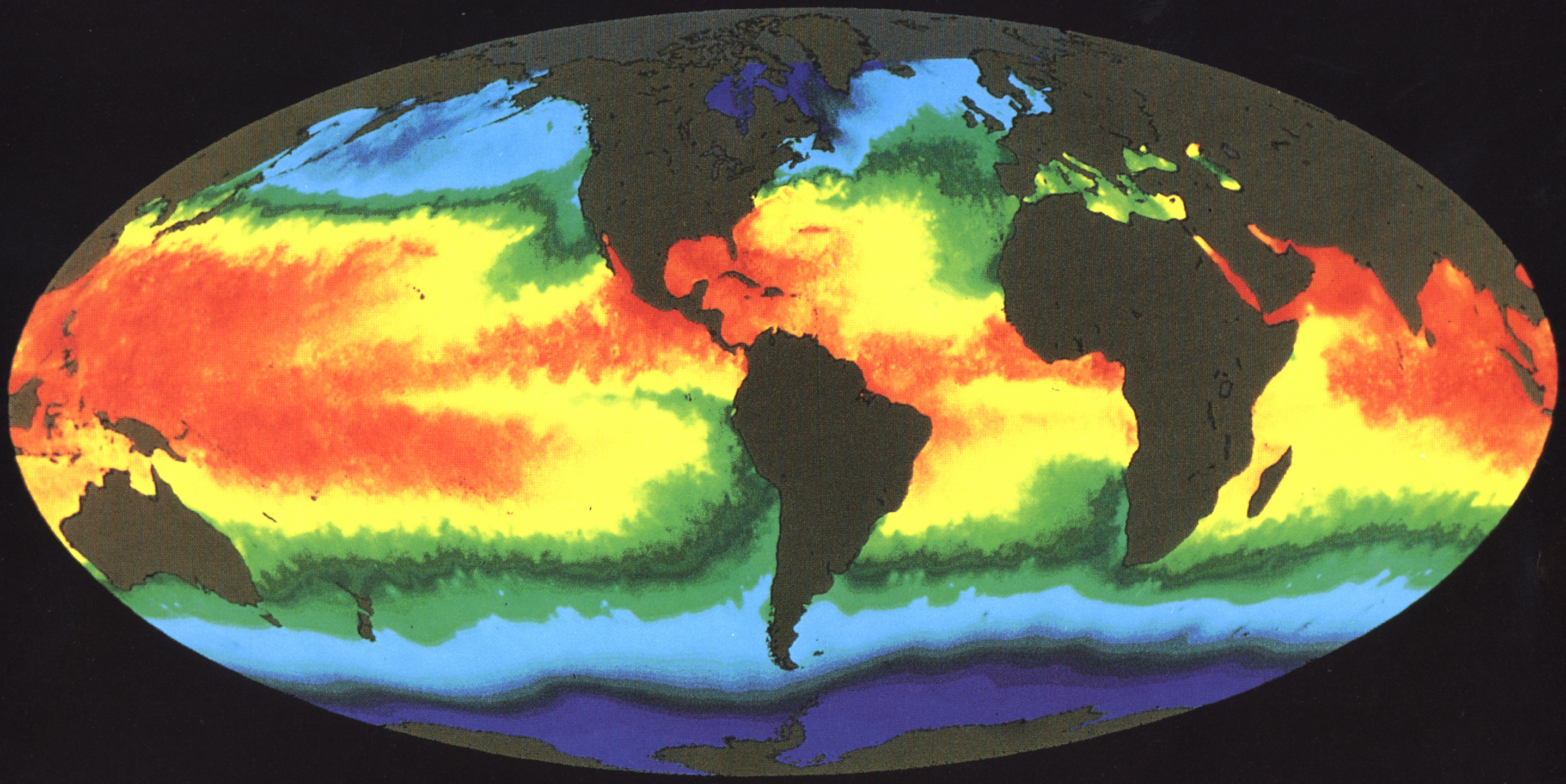

The global moisture budget is primarily being influenced by tropical sea surface temperatures from the position of the

The global moisture budget is primarily being influenced by tropical sea surface temperatures from the position of the

El Nino 3.4 SSTA

data, of tropical oceans to seawater δ18O ratio anomalies from corals. ENSO phenomenon can be related to variations in sea surface salinity (SSS) and sea surface temperature (SST) that can help model tropical climate activities.

Climate research on live coral species is limited to a few studied species. Studying ''

Climate research on live coral species is limited to a few studied species. Studying ''

The saltwater fishkeeping hobby has expanded, over recent years, to include

The saltwater fishkeeping hobby has expanded, over recent years, to include

marine invertebrates

Marine invertebrates are invertebrate animals that live in marine habitats, and make up most of the macroscopic life in the oceans. It is a polyphyletic blanket term that contains all marine animals except the marine vertebrates, including the ...

within the subphylum

In zoological nomenclature, a subphylum is a taxonomic rank below the rank of phylum.

The taxonomic rank of " subdivision" in fungi and plant taxonomy is equivalent to "subphylum" in zoological taxonomy. Some plant taxonomists have also used th ...

Anthozoa

Anthozoa is one of the three subphyla of Cnidaria, along with Medusozoa and Endocnidozoa. It includes Sessility (motility), sessile marine invertebrates and invertebrates of brackish water, such as sea anemones, Scleractinia, stony corals, soft c ...

of the phylum

In biology, a phylum (; : phyla) is a level of classification, or taxonomic rank, that is below Kingdom (biology), kingdom and above Class (biology), class. Traditionally, in botany the term division (taxonomy), division has been used instead ...

Cnidaria

Cnidaria ( ) is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic invertebrates found both in fresh water, freshwater and marine environments (predominantly the latter), including jellyfish, hydroid (zoology), hydroids, ...

. They typically form compact colonies

A colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule, which rules the territory and its indigenous peoples separated from the foreign rulers, the colonizer, and their '' metropole'' (or "mother country"). This separated rule was often or ...

of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef

A reef is a ridge or shoal of rock, coral, or similar relatively stable material lying beneath the surface of a natural body of water. Many reefs result from natural, abiotic component, abiotic (non-living) processes such as deposition (geol ...

builders that inhabit tropical oceans and secrete calcium carbonate

Calcium carbonate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is a common substance found in Rock (geology), rocks as the minerals calcite and aragonite, most notably in chalk and limestone, eggshells, gastropod shells, shellfish skel ...

to form a hard skeleton.

A coral "group" is a colony of very many genetically identical polyps. Each polyp is a sac-like animal typically only a few millimeters in diameter and a few centimeters in height. A set of tentacle

In zoology, a tentacle is a flexible, mobile, and elongated organ present in some species of animals, most of them invertebrates. In animal anatomy, tentacles usually occur in one or more pairs. Anatomically, the tentacles of animals work main ...

s surround a central mouth opening. Each polyp excretes an exoskeleton

An exoskeleton () . is a skeleton that is on the exterior of an animal in the form of hardened integument, which both supports the body's shape and protects the internal organs, in contrast to an internal endoskeleton (e.g. human skeleton, that ...

near the base. Over many generations, the colony thus creates a skeleton characteristic of the species which can measure up to several meters in size. Individual colonies grow by asexual reproduction

Asexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that does not involve the fusion of gametes or change in the number of chromosomes. The offspring that arise by asexual reproduction from either unicellular or multicellular organisms inherit the f ...

of polyps. Corals also breed sexually by spawning

Spawn is the Egg cell, eggs and Spermatozoa, sperm released or deposited into water by aquatic animals. As a verb, ''to spawn'' refers to the process of freely releasing eggs and sperm into a body of water (fresh or marine); the physical act is ...

: polyps of the same species release gamete

A gamete ( ) is a Ploidy#Haploid and monoploid, haploid cell that fuses with another haploid cell during fertilization in organisms that Sexual reproduction, reproduce sexually. Gametes are an organism's reproductive cells, also referred to as s ...

s simultaneously overnight, often around a full moon. Fertilized eggs form planulae, a mobile early form of the coral polyp which, when mature, settles to form a new colony.

Although some corals are able to catch plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms that drift in Hydrosphere, water (or atmosphere, air) but are unable to actively propel themselves against ocean current, currents (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are ca ...

and small fish

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic animal, aquatic, Anamniotes, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fish fin, fins and craniate, a hard skull, but lacking limb (anatomy), limbs with digit (anatomy), digits. Fish can ...

using stinging cells on their tentacles, most corals obtain the majority of their energy and nutrients from photosynthetic

Photosynthesis ( ) is a Biological system, system of biological processes by which Photoautotrophism, photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical ener ...

unicellular

A unicellular organism, also known as a single-celled organism, is an organism that consists of a single cell, unlike a multicellular organism that consists of multiple cells. Organisms fall into two general categories: prokaryotic organisms and ...

dinoflagellate

The Dinoflagellates (), also called Dinophytes, are a monophyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes constituting the phylum Dinoflagellata and are usually considered protists. Dinoflagellates are mostly marine plankton, but they are also commo ...

s of the genus ''Symbiodinium

''Symbiodinium'' is a genus of dinoflagellates that encompasses the largest and most prevalent group of endosymbiotic dinoflagellates known and have photosymbiotic relationships with many species. These unicellular microalgae commonly reside in ...

'' that live within their tissues. These are commonly known as zooxanthellae

Zooxanthellae (; zooxanthella) is a colloquial term for single-celled photosynthetic organisms that are able to live in symbiosis with diverse marine invertebrates including corals, jellyfish, demosponges, and nudibranchs. Most known zooxanthell ...

and give the coral color. Such corals require sunlight and grow in clear, shallow water, typically at depths less than , but corals in the genus '' Leptoseris'' have been found as deep as . Corals are major contributors to the physical structure of the coral reef

A coral reef is an underwater ecosystem characterized by reef-building corals. Reefs are formed of colonies of coral polyps held together by calcium carbonate. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, whose polyps cluster in group ...

s that develop in tropical and subtropical waters, such as the Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef system, composed of over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over over an area of approximately . The reef is located in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland, ...

off the coast of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

. These corals are increasingly at risk of bleaching

Bleach is the generic name for any chemical product that is used industrially or domestically to remove color from (i.e. to whiten) fabric or fiber (in a process called bleaching) or to disinfect after cleaning. It often refers specifically t ...

events where polyps expel the zooxanthellae in response to stress such as high water temperature or toxins.

Other corals do not rely on zooxanthellae and can live globally in much deeper water, such as the cold-water genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

'' Lophelia'' which can survive as deep as . Some have been found as far north as the Darwin Mounds, northwest of Cape Wrath

Cape Wrath (, known as ' in Lewis) is a cape in the Durness parish of the county of Sutherland in the Highlands of Scotland. It is the most north-westerly point in Great Britain.

The cape is separated from the rest of the mainland by the Ky ...

, Scotland, and others off the coast of Washington state

Washington, officially the State of Washington, is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is often referred to as Washington State to distinguish it from the national capital, both named after George Washington ...

and the Aleutian Islands

The Aleutian Islands ( ; ; , "land of the Aleuts"; possibly from the Chukchi language, Chukchi ''aliat'', or "island")—also called the Aleut Islands, Aleutic Islands, or, before Alaska Purchase, 1867, the Catherine Archipelago—are a chain ...

.

Taxonomy

The classification of corals has been discussed for millennia, owing to having similarities to both plants and animals.Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

's pupil Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; ; c. 371 – c. 287 BC) was an ancient Greek Philosophy, philosopher and Natural history, naturalist. A native of Eresos in Lesbos, he was Aristotle's close colleague and successor as head of the Lyceum (classical), Lyceum, the ...

described the red coral, ''korallion'', in his book on stones, implying it was a mineral, but he described it as a deep-sea plant in his ''Enquiries on Plants'', where he also mentions large stony plants that reveal bright flowers when under water in the Gulf of Heroes. Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

stated boldly that several sea creatures including sea nettles and sponges "are neither animals nor plants, but are possessed of a third nature (''tertia natura'')". Petrus Gyllius copied Pliny, introducing the term ''zoophyta'' for this third group in his 1535 book ''On the French and Latin Names of the Fishes of the Marseilles Region''; it is popularly but wrongly supposed that Aristotle created the term. Gyllius further noted, following Aristotle, how hard it was to define what was a plant and what was an animal. The Babylonian Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the centerpiece of Jewi ...

refers to coral among a list of types of trees, and the 11th-century French commentator Rashi

Shlomo Yitzchaki (; ; ; 13 July 1105) was a French rabbi who authored comprehensive commentaries on the Talmud and Hebrew Bible. He is commonly known by the List of rabbis known by acronyms, Rabbinic acronym Rashi ().

Born in Troyes, Rashi stud ...

describes it as "a type of tree (מין עץ) that grows underwater that goes by the (French) name 'coral'."

The Persian polymath Al-Biruni

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (; ; 973after 1050), known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously "Father of Comparative Religion", "Father of modern ...

(d.1048) classified sponges and corals as animals, arguing that they respond to touch. Nevertheless, people believed corals to be plants until the eighteenth century when William Herschel

Frederick William Herschel ( ; ; 15 November 1738 – 25 August 1822) was a German-British astronomer and composer. He frequently collaborated with his younger sister and fellow astronomer Caroline Herschel. Born in the Electorate of Hanover ...

used a microscope to establish that coral had the characteristic thin cell membranes of an animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Biology, biological Kingdom (biology), kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, ...

.

Presently, corals are classified as species of animals within the sub-classes Hexacorallia

Hexacorallia is a Class (biology), class of Anthozoa comprising approximately 4,300 species of aquatic organisms formed of polyp (zoology), polyps, generally with 6-fold symmetry. It includes all of the stony corals, most of which are Colony (b ...

and Octocorallia

Octocorallia, along with Hexacorallia, is one of the two extant classes of Anthozoa. It comprises over 3,000 species of marine and brackish animals consisting of colonial polyps with 8-fold symmetry, commonly referred informally as "soft cora ...

of the class

Class, Classes, or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used d ...

Anthozoa

Anthozoa is one of the three subphyla of Cnidaria, along with Medusozoa and Endocnidozoa. It includes Sessility (motility), sessile marine invertebrates and invertebrates of brackish water, such as sea anemones, Scleractinia, stony corals, soft c ...

in the phylum

In biology, a phylum (; : phyla) is a level of classification, or taxonomic rank, that is below Kingdom (biology), kingdom and above Class (biology), class. Traditionally, in botany the term division (taxonomy), division has been used instead ...

Cnidaria

Cnidaria ( ) is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic invertebrates found both in fresh water, freshwater and marine environments (predominantly the latter), including jellyfish, hydroid (zoology), hydroids, ...

. Hexacorallia includes the stony corals and these groups have polyps that generally have a 6-fold symmetry. Octocorallia includes blue coral and soft coral

Alcyonacea is the old scientific order name for the informal group known as "soft corals". It is now an unaccepted name for class Octocorallia. It became deprecated .

The following text should be considered a historical, outdated way of treatin ...

s and species of Octocorallia have polyps with an eightfold symmetry, each polyp having eight tentacles and eight mesenteries

In human anatomy, the mesentery is an organ that attaches the intestines to the posterior abdominal wall, consisting of a double fold of the peritoneum. It helps (among other functions) in storing fat and allowing blood vessels, lymphatics, a ...

. The group of corals is paraphyletic

Paraphyly is a taxonomic term describing a grouping that consists of the grouping's last common ancestor and some but not all of its descendant lineages. The grouping is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In co ...

because the sea anemone

Sea anemones ( ) are a group of predation, predatory marine invertebrates constituting the order (biology), order Actiniaria. Because of their colourful appearance, they are named after the ''Anemone'', a terrestrial flowering plant. Sea anemone ...

s are also in the sub-class Hexacorallia.

Systematics

The delineation of coral species is challenging as hypotheses based on morphological traits contradict hypotheses formed via molecular tree-based processes. As of 2020, there are 2175 identified separate coral species, 237 of which are currently endangered, making distinguishing corals to be the utmost of importance in efforts to curb extinction.Adaptation

In biology, adaptation has three related meanings. Firstly, it is the dynamic evolutionary process of natural selection that fits organisms to their environment, enhancing their evolutionary fitness. Secondly, it is a state reached by the p ...

and delineation continues to occur in species of coral in order to combat the dangers posed by the climate crisis. Corals are colonial modular organisms formed by asexually produced and genetically identical modules called polyps. Polyps are connected by living tissue to produce the full organism. The living tissue allows for inter module communication (interaction between each polyp), which appears in colony morphologies produced by corals, and is one of the main identifying characteristics for a species of coral.

There are two main classifications for corals: hard coral (scleractinian and stony coral) which form reefs by a calcium carbonate base, with polyps that bear six stiff tentacles, and soft coral (Alcyonacea and ahermatypic coral) which are pliable and formed by a colony of polyps with eight feather-like tentacles. These two classifications arose frodifferentiation in gene expressions

in their branch tips and bases that arose through developmental signaling pathways such as Hox,

Hedgehog

A hedgehog is a spiny mammal of the subfamily Erinaceinae, in the eulipotyphlan family Erinaceidae. There are 17 species of hedgehog in five genera found throughout parts of Europe, Asia, and Africa, and in New Zealand by introduction. The ...

, WntBMP

etc. Scientists typically select ''Acropora'' as research models since they are the most diverse genus of hard coral, having over 120 species. Most species within this genus have polyps which are dimorphic: axial polyps grow rapidly and have lighter coloration, while radial polyps are small and are darker in coloration. In the ''Acropora'' genus, gamete synthesis and

photosynthesis

Photosynthesis ( ) is a system of biological processes by which photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical energy necessary to fuel their metabo ...

occur at the basal polyps, growth occurs mainly at the radial polyps. Growth at the site of the radial polyps encompasses two processes: asexual reproduction

Asexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that does not involve the fusion of gametes or change in the number of chromosomes. The offspring that arise by asexual reproduction from either unicellular or multicellular organisms inherit the f ...

vimitotic cell proliferation

and skeleton deposition of the calcium carbonate via

extracellular matrix

In biology, the extracellular matrix (ECM), also called intercellular matrix (ICM), is a network consisting of extracellular macromolecules and minerals, such as collagen, enzymes, glycoproteins and hydroxyapatite that provide structural and bio ...

(ECM) proteins acting adifferentially expressed (DE) signaling genes

ref name=":2" /> between both branch tips and bases. These processes lead t

colony differentiation

which is the most accurate distinguisher between coral species. In the Acropora genus, colony differentiation through up-regulation and down-regulation of DEs. Systematic studies of soft coral species have faced challenges due to a lack of

taxonomic

280px, Generalized scheme of taxonomy

Taxonomy is a practice and science concerned with classification or categorization. Typically, there are two parts to it: the development of an underlying scheme of classes (a taxonomy) and the allocation ...

knowledge. Researchers have not found enough variability within the genus to confidently delineate similar species, due to a low rate in mutation of mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA and mDNA) is the DNA located in the mitochondrion, mitochondria organelles in a eukaryotic cell that converts chemical energy from food into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA is a small portion of the D ...

.

Environmental factors, such as the rise of temperatures and acid levels in our oceans account for some speciation

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which populations evolve to become distinct species. The biologist Orator F. Cook coined the term in 1906 for cladogenesis, the splitting of lineages, as opposed to anagenesis, phyletic evolution within ...

of corals in the form of species lost. Various coral species have heat shock protein

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are a family of proteins produced by cells in response to exposure to stressful conditions. They were first described in relation to heat shock, but are now known to also be expressed during other stresses including ex ...

s (HSP) that are also in the category of DE across species. These HSPs help corals combat the increased temperatures they are facing which lead to protein denaturing, growth loss, and eventually coral death. Approximately 33% of coral species are on the International Union for Conservation of Nature's endangered species list and at risk of species loss. Ocean acidification

Ocean acidification is the ongoing decrease in the pH of the Earth's ocean. Between 1950 and 2020, the average pH of the ocean surface fell from approximately 8.15 to 8.05. Carbon dioxide emissions from human activities are the primary cause of ...

(falling pH levels in the oceans) is threatening the continued species growth and differentiation of corals. Mutation rates of ''Vibrio

''Vibrio'' is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria, which have a characteristic curved-rod (comma) shape, several species of which can cause foodborne infection or soft-tissue infection called Vibriosis. Infection is commonly associated with eati ...

shilonii'', the reef pathogen

In biology, a pathogen (, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of"), in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a Germ theory of d ...

responsible for coral bleaching

Coral bleaching is the process when corals become white due to loss of Symbiosis, symbiotic algae and Photosynthesis, photosynthetic pigments. This loss of pigment can be caused by various stressors, such as changes in water temperature, light, ...

, heavily outweigh the typical reproduction rates of coral colonies when pH levels fall. Thus, corals are unable to mutate their HSPs and other climate change preventative genes to combat the increase in temperature and decrease in pH at a competitive rate to these pathogens responsible for coral bleaching, resulting in species loss.

Anatomy

For most of their life corals are sessile animals of

For most of their life corals are sessile animals of colonies

A colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule, which rules the territory and its indigenous peoples separated from the foreign rulers, the colonizer, and their '' metropole'' (or "mother country"). This separated rule was often or ...

of genetically identical polyps. Each polyp varies from millimeters to centimeters in diameter, and colonies can be formed from many millions of individual polyps. Stony coral, also known as hard coral, polyps produce a skeleton composed of calcium carbonate

Calcium carbonate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is a common substance found in Rock (geology), rocks as the minerals calcite and aragonite, most notably in chalk and limestone, eggshells, gastropod shells, shellfish skel ...

to strengthen and protect the organism. This is deposited by the polyps and by the coenosarc

In corals, the coenosarc is the living tissue overlying the stony skeletal material of the coral. It secretes the coenosteum, the layer of skeletal material lying between the corallites (the stony cups in which the polyp (zoology), polyps sit). The ...

, the living tissue that connects them. The polyps sit in cup-shaped depressions in the skeleton known as corallite

A corallite is the skeletal cup, formed by an individual stony coral polyp, in which the polyp sits and into which it can retract. The cup is composed of aragonite, a crystalline form of calcium carbonate, and is secreted by the polyp. Corallit ...

s. Colonies of stony coral are markedly variable in appearance; a single species may adopt an encrusting, plate-like, bushy, columnar or massive solid structure, the various forms often being linked to different types of habitat, with variations in light level and water movement being significant.

The body of the polyp may be roughly compared in a structure to a sac, the wall of which is composed of two layers of cell

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

* Cellphone, a phone connected to a cellular network

* Clandestine cell, a penetration-resistant form of a secret or outlawed organization

* Electrochemical cell, a de ...

s. The outer layer is known technically as the ectoderm

The ectoderm is one of the three primary germ layers formed in early embryonic development. It is the outermost layer, and is superficial to the mesoderm (the middle layer) and endoderm (the innermost layer). It emerges and originates from the o ...

, the inner layer as the endoderm

Endoderm is the innermost of the three primary germ layers in the very early embryo. The other two layers are the ectoderm (outside layer) and mesoderm (middle layer). Cells migrating inward along the archenteron form the inner layer of the gastr ...

. Between ectoderm and endoderm is a supporting layer of gelatinous substance termed mesoglea

Mesoglea refers to the extracellular matrix found in cnidarians like coral or jellyfish as well as ctenophores that functions as a hydrostatic skeleton. It is related to but distinct from mesohyl, which generally refers to extracellular material f ...

, secreted by the cell layers of the body wall. The mesoglea can contain skeletal

A skeleton is the structural frame that supports the body of most animals. There are several types of skeletons, including the exoskeleton, which is a rigid outer shell that holds up an organism's shape; the endoskeleton, a rigid internal fram ...

elements derived from cells migrated from the ectoderm.

The sac-like body built up in this way is attached to a hard surface, which in hard corals are cup-shaped depressions in the skeleton known as corallite

A corallite is the skeletal cup, formed by an individual stony coral polyp, in which the polyp sits and into which it can retract. The cup is composed of aragonite, a crystalline form of calcium carbonate, and is secreted by the polyp. Corallit ...

s. At the center of the upper end of the sac lies the only opening called the mouth, surrounded by a circle of tentacle

In zoology, a tentacle is a flexible, mobile, and elongated organ present in some species of animals, most of them invertebrates. In animal anatomy, tentacles usually occur in one or more pairs. Anatomically, the tentacles of animals work main ...

s which resemble glove fingers. The tentacles are organ

Organ and organs may refer to:

Biology

* Organ (biology), a group of tissues organized to serve a common function

* Organ system, a collection of organs that function together to carry out specific functions within the body.

Musical instruments

...

s which serve both for tactile sense and for the capture of food. Polyps extend their tentacles, particularly at night, often containing coiled stinging cells (cnidocyte

A cnidocyte (also known as a cnidoblast) is a type of cell containing a large secretory organelle called a ''cnidocyst'', that can deliver a sting to other organisms as a way to capture prey and defend against predators. A cnidocyte explosively ...

s) which pierce, poison and firmly hold living prey paralyzing or killing them. Polyp prey includes plankton such as copepods

Copepods (; meaning 'oar-feet') are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat. Some species are planktonic (living in the water column), some are benthic (living on the sediments), several species have ...

and fish larvae. Longitudinal muscular fibers formed from the cells of the ectoderm allow tentacles to contract to convey the food to the mouth. Similarly, circularly disposed muscular fibers formed from the endoderm permit tentacles to be protracted or thrust out once they are contracted. In both stony and soft corals, the polyps can be retracted by contracting muscle fibers, with stony corals relying on their hard skeleton and cnidocytes for defense. Soft corals generally secrete terpenoid

The terpenoids, also known as isoprenoids, are a class of naturally occurring organic compound, organic chemicals derived from the 5-carbon compound isoprene and its derivatives called terpenes, diterpenes, etc. While sometimes used interchangeabl ...

toxins to ward off predators.

In most corals, the tentacles are retracted by day and spread out at night to catch plankton and other small organisms. Shallow-water species of both stony and soft corals can be zooxanthellate, the corals supplementing their plankton diet with the products of photosynthesis produced by these symbionts. The polyps interconnect by a complex and well-developed system of gastrovascular canals, allowing significant sharing of nutrients and symbionts.

The external form of the polyp varies greatly. The column may be long and slender, or may be so short in the axial direction that the body becomes disk-like. The tentacles may number many hundreds or may be very few, in rare cases only one or two. They may be simple and unbranched, or feathery in pattern. The mouth may be level with the surface of the peristome, or may be projecting and trumpet-shaped.

Soft corals

Soft corals have no solid exoskeleton as such. However, their tissues are often reinforced by small supportive elements known assclerites

A sclerite (Greek , ', meaning " hard") is a hardened body part. In various branches of biology the term is applied to various structures, but not as a rule to vertebrate anatomical features such as bones and teeth. Instead it refers most commonly ...

made of calcium carbonate. The polyps of soft corals have eight-fold symmetry, which is reflected in the ''Octo'' in Octocorallia.

Soft corals vary considerably in form, and most are colonial. A few soft corals are stolon

In biology, a stolon ( from Latin ''wikt:stolo, stolō'', genitive ''stolōnis'' – "branch"), also known as a runner, is a horizontal connection between parts of an organism. It may be part of the organism, or of its skeleton. Typically, animal ...

ate, but the polyps of most are connected by sheets of tissue called coenosarc, and in some species these sheets are thick and the polyps deeply embedded in them. Some soft corals encrust other sea objects or form lobes. Others are tree-like or whip-like and have a central axial skeleton embedded at their base in the matrix of the supporting branch. These branches are composed of a fibrous protein called gorgonin

Gorgonin is a flexible scleroprotein which provides structural strength to gorgonian corals, a subset of the order Alcyonacea. Gorgonian corals have supporting skeletal axes made of gorgonin and/or calcite. Gorgonin makes up the joints of bambo ...

or of a calcified material.

Stony corals

The polyps of stony corals have six-fold symmetry. In stony corals, the tentacles are cylindrical and taper to a point, but in soft corals they are pinnate with side branches known as pinnules. In some tropical species, these are reduced to mere stubs and in some, they are fused to give a paddle-like appearance.

Coral skeletons are biocomposites (mineral + organics) of calcium carbonate, in the form of calcite or aragonite. In scleractinian corals, "centers of calcification" and fibers are clearly distinct structures differing with respect to both morphology and chemical compositions of the crystalline units. The organic matrices extracted from diverse species are acidic, and comprise proteins, sulphated sugars and lipids; they are species specific. The soluble organic matrices of the skeletons allow to differentiate

The polyps of stony corals have six-fold symmetry. In stony corals, the tentacles are cylindrical and taper to a point, but in soft corals they are pinnate with side branches known as pinnules. In some tropical species, these are reduced to mere stubs and in some, they are fused to give a paddle-like appearance.

Coral skeletons are biocomposites (mineral + organics) of calcium carbonate, in the form of calcite or aragonite. In scleractinian corals, "centers of calcification" and fibers are clearly distinct structures differing with respect to both morphology and chemical compositions of the crystalline units. The organic matrices extracted from diverse species are acidic, and comprise proteins, sulphated sugars and lipids; they are species specific. The soluble organic matrices of the skeletons allow to differentiate zooxanthellae

Zooxanthellae (; zooxanthella) is a colloquial term for single-celled photosynthetic organisms that are able to live in symbiosis with diverse marine invertebrates including corals, jellyfish, demosponges, and nudibranchs. Most known zooxanthell ...

and non-zooxanthellae specimens.

Ecology

Feeding

Polyps feed on a variety of small organisms, from microscopic zooplankton to small fish. The polyp's tentacles immobilize or kill prey using stinging cells called cnidocytes, commonly called nematocysts. These cells carryvenom

Venom or zootoxin is a type of toxin produced by an animal that is actively delivered through a wound by means of a bite, sting, or similar action. The toxin is delivered through a specially evolved ''venom apparatus'', such as fangs or a sti ...

which they rapidly release in response to contact with another organism. A dormant nematocyst discharges in response to nearby prey touching the trigger. A stiff flap called an operculum opens and its stinging apparatus fires the barb into the prey. The venom is injected through the hollow filament to immobilise the prey; the tentacles then manoeuvre the prey into the stomach. Once the prey is digested the stomach reopens allowing the elimination of waste products and the beginning of the next hunting cycle.

Intracellular symbionts

Many corals, as well as othercnidaria

Cnidaria ( ) is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic invertebrates found both in fresh water, freshwater and marine environments (predominantly the latter), including jellyfish, hydroid (zoology), hydroids, ...

n groups such as sea anemone

Sea anemones ( ) are a group of predation, predatory marine invertebrates constituting the order (biology), order Actiniaria. Because of their colourful appearance, they are named after the ''Anemone'', a terrestrial flowering plant. Sea anemone ...

s form a symbiotic

Symbiosis (Ancient Greek : living with, companionship < : together; and ''bíōsis'': living) is any type of a close and long-term biolo ...

relationship with a class of dinoflagellate

The Dinoflagellates (), also called Dinophytes, are a monophyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes constituting the phylum Dinoflagellata and are usually considered protists. Dinoflagellates are mostly marine plankton, but they are also commo ...

algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthesis, photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular ...

, zooxanthellae

Zooxanthellae (; zooxanthella) is a colloquial term for single-celled photosynthetic organisms that are able to live in symbiosis with diverse marine invertebrates including corals, jellyfish, demosponges, and nudibranchs. Most known zooxanthell ...

of the genus ''Symbiodinium

''Symbiodinium'' is a genus of dinoflagellates that encompasses the largest and most prevalent group of endosymbiotic dinoflagellates known and have photosymbiotic relationships with many species. These unicellular microalgae commonly reside in ...

'', which can form as much as 30% of the tissue of a polyp. Typically, each polyp harbors one species of alga, and coral species show a preference for ''Symbiodinium

''Symbiodinium'' is a genus of dinoflagellates that encompasses the largest and most prevalent group of endosymbiotic dinoflagellates known and have photosymbiotic relationships with many species. These unicellular microalgae commonly reside in ...

''. Young corals are not born with zooxanthellae, but acquire the algae from the surrounding environment, including the water column and local sediment. The main benefit of the zooxanthellae is their ability to photosynthesize which supplies corals with the products of photosynthesis, including glucose, glycerol, also amino acids, which the corals can use for energy. Zooxanthellae also benefit corals by aiding in calcification

Calcification is the accumulation of calcium salts in a body tissue. It normally occurs in the formation of bone, but calcium can be deposited abnormally in soft tissue,Miller, J. D. Cardiovascular calcification: Orbicular origins. ''Nature M ...

, for the coral skeleton, and waste removal. In addition to the soft tissue, microbiome

A microbiome () is the community of microorganisms that can usually be found living together in any given habitat. It was defined more precisely in 1988 by Whipps ''et al.'' as "a characteristic microbial community occupying a reasonably wel ...

s are also found in the coral's mucus and (in stony corals) the skeleton, with the latter showing the greatest microbial richness.

The zooxanthellae benefit from a safe place to live and consume the polyp's carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

, phosphate and nitrogenous waste. Stressed corals will eject their zooxanthellae, a process that is becoming increasingly common due to strain placed on coral by rising ocean temperatures. Mass ejections are known as coral bleaching

Coral bleaching is the process when corals become white due to loss of Symbiosis, symbiotic algae and Photosynthesis, photosynthetic pigments. This loss of pigment can be caused by various stressors, such as changes in water temperature, light, ...

because the algae contribute to coral coloration; some colors, however, are due to host coral pigments, such as green fluorescent protein

The green fluorescent protein (GFP) is a protein that exhibits green fluorescence when exposed to light in the blue to ultraviolet range. The label ''GFP'' traditionally refers to the protein first isolated from the jellyfish ''Aequorea victo ...

s (GFPs). Ejection increases the polyp's chance of surviving short-term stress and if the stress subsides they can regain algae, possibly of a different species, at a later time. If the stressful conditions persist, the polyp eventually dies. Zooxanthellae are located within the coral cytoplasm and due to the algae's photosynthetic activity the internal pH of the coral can be raised; this behavior indicates that the zooxanthellae are responsible to some extent for the metabolism of their host corals. Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease has been associated with the breakdown of host-zooxanthellae physiology. Moreover, Vibrio bacterium are known to have virulence traits used for host coral tissue damage and photoinhibition of algal symbionts. Therefore, both coral and their symbiotic microorganisms could have evolved to harbour traits resistant to disease and transmission.

Reproduction

Corals can be both gonochoristic (unisexual) andhermaphroditic

A hermaphrodite () is a sexually reproducing organism that produces both male and female gametes. Animal species in which individuals are either male or female are gonochoric, which is the opposite of hermaphroditic.

The individuals of many ...

, each of which can reproduce sexually and asexually. Reproduction also allows coral to settle in new areas. Reproduction is coordinated by chemical communication.

Sexual

hermatypic coral

Hermatypic corals are those corals in the order Scleractinia which build reefs by depositing hard calcareous material for their skeletons, forming the stony framework of the reef. Corals that do not contribute to coral reef development are referred ...

s (reef-building stony corals) form single-sex ( gonochoristic) colonies, while the rest are hermaphroditic

A hermaphrodite () is a sexually reproducing organism that produces both male and female gametes. Animal species in which individuals are either male or female are gonochoric, which is the opposite of hermaphroditic.

The individuals of many ...

. It is estimated more than 67% of coral are simultaneous hermaphrodites.

Broadcasters

About 75% of all hermatypic corals "broadcast spawn" by releasinggamete

A gamete ( ) is a Ploidy#Haploid and monoploid, haploid cell that fuses with another haploid cell during fertilization in organisms that Sexual reproduction, reproduce sexually. Gametes are an organism's reproductive cells, also referred to as s ...

s— eggs and sperm

Sperm (: sperm or sperms) is the male reproductive Cell (biology), cell, or gamete, in anisogamous forms of sexual reproduction (forms in which there is a larger, female reproductive cell and a smaller, male one). Animals produce motile sperm ...

—into the water where they meet and fertilize to spread offspring. Corals often synchronize their time of spawning. This reproductive synchrony is essential so that male and female gametes can meet. Spawning frequently takes place in the evening or at night, and can occur as infrequently as once a year, and within a window of 10–30 minutes.

Synchronous spawning is very typical on the coral reef, and often, all corals spawn on the same night even when multiple species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

are present. Synchronous spawning may form hybrids and is perhaps involved in coral speciation

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which populations evolve to become distinct species. The biologist Orator F. Cook coined the term in 1906 for cladogenesis, the splitting of lineages, as opposed to anagenesis, phyletic evolution within ...

.

Environmental cues that influence the release of gametes into the water vary from species to species. The cues involve temperature change,

Environmental cues that influence the release of gametes into the water vary from species to species. The cues involve temperature change, lunar cycle

A lunar phase or Moon phase is the apparent shape of the Moon's directly sunlit portion as viewed from the Earth. Because the Moon is tidally locked with the Earth, the same hemisphere is always facing the Earth. In common usage, the four majo ...

, day length

Daytime or day as observed on Earth is the period of the day during which a given location experiences natural illumination from direct sunlight. Daytime occurs when the Sun appears above the local horizon, that is, anywhere on the globe's ...

, and possibly chemical signalling.

Other factors that affect the rhythmicity of organisms in marine habitats include salinity, mechanical forces, and pressure or magnetic field changes.

Mass coral spawning often occurs at night on days following a full moon. A full moon is equivalent to four to six hours of continuous dim light exposure, which can cause light-dependent reactions

Light-dependent reactions are certain photochemical reactions involved in photosynthesis, the main process by which plants acquire energy. There are two light dependent reactions: the first occurs at photosystem II (PSII) and the second occurs ...

in protein. Corals contain light-sensitive cryptochromes, proteins whose light-absorbing flavin structures are sensitive to different types of light. This allows corals such as '' Dipsastraea speciosa'' to detect and respond to changes in sunlight and moonlight.

Moonlight itself may actually suppress coral spawning. The most immediate cue to cause spawning appears to be the dark portion of the night between sunset and moonrise.

Over the lunar cycle, moonrise shifts progressively later, occurring after sunset on the day of the full moon. The resulting dark period between day-light and night-light removes the suppressive effect of moonlight and enables coral to spawn.

The spawning event can be visually dramatic, clouding the usually clear water with gametes. Once released, gametes fertilize at the water's surface and form a microscopic larva

A larva (; : larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into their next life stage. Animals with indirect development such as insects, some arachnids, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase ...

called a planula

A planula is the free-swimming, flattened, ciliated, bilaterally symmetric larval form of various cnidarian species and also in some species of Ctenophores, which are not related to cnidarians at all. Some groups of Nemerteans also produce larva ...

, typically pink and elliptical in shape. A typical coral colony needs to release several thousand larvae per year to overcome the odds against formation of a new colony.

Studies suggest that light pollution desynchronizes spawning in some coral species.

In areas such as the Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

, as many as 10 out of 50 species may be showing spawning asynchrony, compared to 30 years ago. The establishment of new corals in the area has decreased and in some cases ceased. The area was previously considered a refuge for corals because mass bleaching events due to climate change had not been observed there. Coral restoration techniques for coral reef management are being developed to increase fertilization rates, larval development, and settlement of new corals.

Brooders

Brooding species are most often ahermatypic (not reef-building) in areas of high current or wave action. Brooders release only sperm, which is negatively buoyant, sinking onto the waiting egg carriers that harbor unfertilized eggs for weeks. Synchronous spawning events sometimes occur even with these species. After fertilization, the corals release planula that are ready to settle.Planulae

The time from spawning to larval settlement is usually two to three days but can occur immediately or up to two months. Broadcast-spawnedplanula

A planula is the free-swimming, flattened, ciliated, bilaterally symmetric larval form of various cnidarian species and also in some species of Ctenophores, which are not related to cnidarians at all. Some groups of Nemerteans also produce larva ...

larvae develop at the water's surface before descending to seek a hard surface on the benthos to which they can attach and begin a new colony. The larvae often need a biological cue to induce settlement such as specific crustose coralline algae

Coralline algae are red algae in the order Corallinales. They are characterized by a thallus that is hard because of calcareous deposits contained within the cell walls. The colors of these algae are most typically pink, or some other shade of re ...

species or microbial biofilms. High failure rates afflict many stages of this process, and even though thousands of eggs are released by each colony, few new colonies form. During settlement, larvae are inhibited by physical barriers such as sediment, as well as chemical (allelopathic) barriers. The larvae metamorphose into a single polyp and eventually develops into a juvenile and then adult by asexual budding and growth.

Asexual

Within a coral head, the genetically identical polyps reproduce asexually, either by

Within a coral head, the genetically identical polyps reproduce asexually, either by budding

Budding or blastogenesis is a type of asexual reproduction in which a new organism develops from an outgrowth or bud due to cell division at one particular site. For example, the small bulb-like projection coming out from the yeast cell is kno ...

(gemmation) or by dividing, whether longitudinally or transversely.

Budding involves splitting a smaller polyp from an adult. As the new polyp grows, it forms its body parts. The distance between the new and adult polyps grows, and with it, the coenosarc (the common body of the colony). Budding can be intratentacular, from its oral discs, producing same-sized polyps within the ring of tentacles, or extratentacular, from its base, producing a smaller polyp.

Division forms two polyps that each become as large as the original. Longitudinal division begins when a polyp broadens and then divides its coelenteron (body), effectively splitting along its length. The mouth divides and new tentacles form. The two polyps thus created then generate their missing body parts and exoskeleton. Transversal division occurs when polyps and the exoskeleton divide transversally into two parts. This means one has the basal disc (bottom) and the other has the oral disc (top); the new polyps must separately generate the missing pieces.

Asexual reproduction offers the benefits of high reproductive rate, delaying senescence, and replacement of dead modules, as well as geographical distribution.

Colony division

Whole colonies can reproduce asexually, forming two colonies with the same genotype. The possible mechanisms include fission, bailout and fragmentation. Fission occurs in some corals, especially among the family Fungiidae, where the colony splits into two or more colonies during early developmental stages. Bailout occurs when a single polyp abandons the colony and settles on a different substrate to create a new colony. Fragmentation involves individuals broken from the colony during storms or other disruptions. The separated individuals can start new colonies.Coral microbiomes

Corals are one of the more common examples of an animal host whose symbiosis with microalgae can turn to

Corals are one of the more common examples of an animal host whose symbiosis with microalgae can turn to dysbiosis

Dysbiosis (also called dysbacteriosis) is characterized by a disruption to the microbiome resulting in an imbalance in the microbiota, changes in their functional composition and metabolic activities, or a shift in their local distribution. For e ...

, and is visibly detected as bleaching. Coral microbiome

A microbiome () is the community of microorganisms that can usually be found living together in any given habitat. It was defined more precisely in 1988 by Whipps ''et al.'' as "a characteristic microbial community occupying a reasonably wel ...

s have been examined in a variety of studies, which demonstrate how oceanic environmental variations, most notably temperature, light, and inorganic nutrients, affect the abundance and performance of the microalgal symbionts, as well as calcification

Calcification is the accumulation of calcium salts in a body tissue. It normally occurs in the formation of bone, but calcium can be deposited abnormally in soft tissue,Miller, J. D. Cardiovascular calcification: Orbicular origins. ''Nature M ...

and physiology of the host.Apprill, A. (2017) "Marine animal microbiomes: toward understanding host–microbiome interactions in a changing ocean". ''Frontiers in Marine Science'', 4: 222. . Material was copied from this source, which is available under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Studies have also suggested that resident bacteria, archaea, and fungi additionally contribute to nutrient and organic matter cycling within the coral, with viruses also possibly playing a role in structuring the composition of these members, thus providing one of the first glimpses at a multi-domain marine animal symbiosis. The

gammaproteobacterium

''Gammaproteobacteria'' is a class of bacteria in the phylum ''Pseudomonadota'' (synonym ''Proteobacteria''). It contains about 250 genera, which makes it the most genus-rich taxon of the Prokaryotes. Several medically, ecologically, and scienti ...

''Endozoicomonas

''Endozoicomonas'' is a genus of Gram-negative, aerobic or facultatively anaerobic, chemoorganotrophic, rod-shaped, marine bacteria from the family of ''Endozoicomonadaceae''. ''Endozoicomonas'' are symbionts of marine animals.

Scientific ...

'' is emerging as a central member of the coral's microbiome, with flexibility in its lifestyle.Neave, M.J., Apprill, A., Ferrier-Pagès, C. and Voolstra, C.R. (2016) "Diversity and function of prevalent symbiotic marine bacteria in the genus ''Endozoicomonas''". ''Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology'', 100(19): 8315–8324. . Given the recent mass bleaching occurring on reefs, corals will likely continue to be a useful and popular system for symbiosis and dysbiosis research.

'' Astrangia poculata'', the northern star coral, is a temperate stony coral

Scleractinia, also called stony corals or hard corals, are marine animals in the phylum Cnidaria that build themselves a hard skeleton. The individual animals are known as polyps and have a cylindrical body crowned by an oral disc in which a mo ...

, widely documented along the eastern coast of the United States. The coral can live with and without zooxanthellae

Zooxanthellae (; zooxanthella) is a colloquial term for single-celled photosynthetic organisms that are able to live in symbiosis with diverse marine invertebrates including corals, jellyfish, demosponges, and nudibranchs. Most known zooxanthell ...

(algal symbionts), making it an ideal model organism

A model organism is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workings of other organisms. Mo ...

to study microbial community interactions associated with symbiotic state. However, the ability to develop primers and probes to more specifically target key microbial groups has been hindered by the lack of full-length 16S rRNA

16S ribosomal RNA (or 16Svedberg, S rRNA) is the RNA component of the 30S subunit of a prokaryotic ribosome (SSU rRNA). It binds to the Shine-Dalgarno sequence and provides most of the SSU structure.

The genes coding for it are referred to as ...

sequences, since sequences produced by the Illumina platform are of insufficient length (approximately 250 base pairs) for the design of primers and probes. In 2019, Goldsmith et al. demonstrated Sanger sequencing

Sanger sequencing is a method of DNA sequencing that involves electrophoresis and is based on the random incorporation of chain-terminating dideoxynucleotides by DNA polymerase during in vitro DNA replication. After first being developed by Fred ...

was capable of reproducing the biologically relevant diversity detected by deeper next-generation sequencing

Massive parallel sequencing or massively parallel sequencing is any of several high-throughput approaches to DNA sequencing using the concept of massively parallel processing; it is also called next-generation sequencing (NGS) or second-generation ...

, while also producing longer sequences useful to the research community for probe and primer design (see diagram on right). Material was copied from this source, which is available under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Holobionts

Reef-building corals are well-studiedholobiont

A holobiont is an assemblage of a Host (biology), host and the many other species living in or around it, which together form a discrete ecological unit through symbiosis, though there is controversy over this discreteness. The components of a h ...

s that include the coral itself together with its symbiont zooxanthellae

Zooxanthellae (; zooxanthella) is a colloquial term for single-celled photosynthetic organisms that are able to live in symbiosis with diverse marine invertebrates including corals, jellyfish, demosponges, and nudibranchs. Most known zooxanthell ...

(photosynthetic dinoflagellates), as well as its associated bacteria and viruses.Knowlton, N. and Rohwer, F. (2003) "Multispecies microbial mutualisms on coral reefs: the host as a habitat". ''The American Naturalist'', 162(S4): S51-S62. . Co-evolutionary patterns exist for coral microbial communities and coral phylogeny. It is known that the coral's

It is known that the coral's microbiome

A microbiome () is the community of microorganisms that can usually be found living together in any given habitat. It was defined more precisely in 1988 by Whipps ''et al.'' as "a characteristic microbial community occupying a reasonably wel ...

and symbiont influence host health, however, the historic influence of each member on others is not well understood. Scleractinian corals have been diversifying for longer than many other symbiotic systems, and their microbiomes are known to be partially species-specific. It has been suggested that ''Endozoicomonas

''Endozoicomonas'' is a genus of Gram-negative, aerobic or facultatively anaerobic, chemoorganotrophic, rod-shaped, marine bacteria from the family of ''Endozoicomonadaceae''. ''Endozoicomonas'' are symbionts of marine animals.

Scientific ...

'', a commonly highly abundant bacterium in corals, has exhibited codiversification with its host. This hints at an intricate set of relationships between the members of the coral holobiont that have been developing as evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

of these members occurs.

A study published in 2018 revealed evidence of phylosymbiosis between corals and their tissue and skeleton microbiomes. The coral skeleton, which represents the most diverse of the three coral microbiomes, showed the strongest evidence of phylosymbiosis. Coral microbiome composition and richness were found to reflect coral phylogeny

A phylogenetic tree or phylogeny is a graphical representation which shows the evolutionary history between a set of species or Taxon, taxa during a specific time.Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, M ...

. For example, interactions between bacterial and eukaryotic coral phylogeny influence the abundance of ''Endozoicomonas'', a highly abundant bacterium in the coral holobiont. However, host-microbial cophylogeny appears to influence only a subset of coral-associated bacteria.

Reefs

Many corals in the orderScleractinia

Scleractinia, also called stony corals or hard corals, are marine animals in the phylum Cnidaria that build themselves a hard skeleton. The individual animals are known as polyps and have a cylindrical body crowned by an oral disc in which a mo ...

are hermatypic, meaning that they are involved in building reefs. Most such corals obtain some of their energy from zooxanthellae

Zooxanthellae (; zooxanthella) is a colloquial term for single-celled photosynthetic organisms that are able to live in symbiosis with diverse marine invertebrates including corals, jellyfish, demosponges, and nudibranchs. Most known zooxanthell ...

in the genus ''Symbiodinium''. These are symbiotic

Symbiosis (Ancient Greek : living with, companionship < : together; and ''bíōsis'': living) is any type of a close and long-term biolo ...

photosynthetic dinoflagellate

The Dinoflagellates (), also called Dinophytes, are a monophyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes constituting the phylum Dinoflagellata and are usually considered protists. Dinoflagellates are mostly marine plankton, but they are also commo ...

s which require sunlight; reef-forming corals are therefore found mainly in shallow water. They secrete calcium carbonate to form hard skeletons that become the framework of the reef. However, not all reef-building corals in shallow water contain zooxanthellae, and some deep water species, living at depths to which light cannot penetrate, form reefs but do not harbour the symbionts.

There are various types of shallow-water coral reef, including fringing reefs, barrier reefs and atolls; most occur in tropical and subtropical seas. They are very slow-growing, adding perhaps one centimetre (0.4 in) in height each year. The Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef system, composed of over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over over an area of approximately . The reef is located in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland, ...

is thought to have been laid down about two million years ago. Over time, corals fragment and die, sand and rubble accumulates between the corals, and the shells of clams and other molluscs decay to form a gradually evolving calcium carbonate structure. Coral reefs are extremely diverse marine ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) is a system formed by Organism, organisms in interaction with their Biophysical environment, environment. The Biotic material, biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and en ...

s hosting over 4,000 species of fish, massive numbers of cnidarians, molluscs

Mollusca is a phylum of protostome, protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant taxon, extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum ...

, crustacean

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

s, and many other animals.

Evolution

At certain times in the geological past, corals were very abundant. Like modern corals, their ancestors built reefs, some of which ended as great structures in

At certain times in the geological past, corals were very abundant. Like modern corals, their ancestors built reefs, some of which ended as great structures in sedimentary rocks

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock formed by the cementation of sediments—i.e. particles made of minerals (geological detritus) or organic matter (biological detritus)—that have been accumulated or deposited at Earth's surface. Sedim ...

. Fossils of fellow reef-dwellers algae, sponges, and the remains of many echinoids

Sea urchins or urchins () are echinoderms in the class (biology), class Echinoidea. About 950 species live on the seabed, inhabiting all oceans and depth zones from the intertidal zone to deep seas of . They typically have a globular body cove ...

, brachiopod

Brachiopods (), phylum (biology), phylum Brachiopoda, are a phylum of animals that have hard "valves" (shells) on the upper and lower surfaces, unlike the left and right arrangement in bivalve molluscs. Brachiopod valves are hinged at the rear e ...

s, bivalve

Bivalvia () or bivalves, in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class (biology), class of aquatic animal, aquatic molluscs (marine and freshwater) that have laterally compressed soft bodies enclosed b ...

s, gastropod

Gastropods (), commonly known as slugs and snails, belong to a large Taxonomy (biology), taxonomic class of invertebrates within the phylum Mollusca called Gastropoda ().

This class comprises snails and slugs from saltwater, freshwater, and fro ...

s, and trilobite

Trilobites (; meaning "three-lobed entities") are extinction, extinct marine arthropods that form the class (biology), class Trilobita. One of the earliest groups of arthropods to appear in the fossil record, trilobites were among the most succ ...

s appear along with coral fossils. This makes some corals useful index fossil

Biostratigraphy is the branch of stratigraphy which focuses on correlating and assigning relative ages of rock strata by using the fossil assemblages contained within them.Hine, Robert. "Biostratigraphy." ''Oxford Reference: Dictionary of Biology ...

s. Coral fossils are not restricted to reef remnants, and many solitary fossils are found elsewhere, such as ''Cyclocyathus'', which occurs in England's Gault clay

The Gault Formation is a geological formation of stiff blue clay deposited in a calm, fairly deep-water marine environment during the Lower Cretaceous Period (Upper and Middle Albian). It is well exposed in the coastal cliffs at Copt Point in Fo ...

formation.

Early corals

Corals first appeared in theCambrian

The Cambrian ( ) is the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 51.95 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran period 538.8 Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Ordov ...

about . Fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

s are extremely rare until the Ordovician

The Ordovician ( ) is a geologic period and System (geology), system, the second of six periods of the Paleozoic Era (geology), Era, and the second of twelve periods of the Phanerozoic Eon (geology), Eon. The Ordovician spans 41.6 million years f ...

period, 100 million years later, when Heliolitida, rugose

Rugose means "wrinkled". It may refer to:

* Rugosa, an extinct order of coral, whose rugose shape earned it the name

* Rugose, adjectival form of rugae

Species with "rugose" in their names

* ''Idiosoma nigrum'', more commonly, a black rugose tra ...

, and tabulate corals became widespread. Paleozoic

The Paleozoic ( , , ; or Palaeozoic) Era is the first of three Era (geology), geological eras of the Phanerozoic Eon. Beginning 538.8 million years ago (Ma), it succeeds the Neoproterozoic (the last era of the Proterozoic Eon) and ends 251.9 Ma a ...

corals often contained numerous endobiotic symbionts.

Tabulate corals occur in limestone

Limestone is a type of carbonate rock, carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material Lime (material), lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different Polymorphism (materials science) ...

s and calcareous shale

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of Clay mineral, clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g., Kaolinite, kaolin, aluminium, Al2Silicon, Si2Oxygen, O5(hydroxide, OH)4) and tiny f ...

s of the Ordovician period, with a gap in the fossil record due to extinction events

An extinction event (also known as a mass extinction or biotic crisis) is a widespread and rapid decrease in the biodiversity on Earth. Such an event is identified by a sharp fall in the diversity and abundance of multicellular organisms. It occ ...

at the end of the Ordovician. Corals reappeared some millions of years later during the Silurian

The Silurian ( ) is a geologic period and system spanning 23.5 million years from the end of the Ordovician Period, at million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Devonian Period, Mya. The Silurian is the third and shortest period of t ...

period, and tabulate corals often form low cushions or branching masses of calcite

Calcite is a Carbonate minerals, carbonate mineral and the most stable Polymorphism (materials science), polymorph of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of limestone. Calcite defines hardness 3 on ...

alongside rugose corals. Tabulate coral numbers began to decline during the middle of the Silurian period.

Rugose or horn corals became dominant by the middle of the Silurian period, and during the Devonian, corals flourished with more than 200 genera. The rugose corals existed in solitary and colonial forms, and were also composed of calcite. Both rugose and tabulate corals became extinct in the Permian–Triassic extinction event

The Permian–Triassic extinction event (also known as the P–T extinction event, the Late Permian extinction event, the Latest Permian extinction event, the End-Permian extinction event, and colloquially as the Great Dying,) was an extinction ...

(along with 85% of marine species), and there is a gap of tens of millions of years until new forms of coral evolved in the Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

.

Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

) near Hiwasse, Arkansas, scale bar is 2.0 cm

File:AuloporaDevonianSilicaShale.jpg, Tabulate coral ''Aulopora

''Aulopora'' is an extinct genus of tabulate coral characterized by a bifurcated budding pattern and conical corallite

A corallite is the skeletal cup, formed by an individual stony coral polyp, in which the polyp sits and into which it can ...

'' from the Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a period (geology), geologic period and system (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era during the Phanerozoic eon (geology), eon, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the preceding Silurian per ...

period

File:RugosaOrdovician.jpg, Solitary rugose coral (''Grewingkia

''Grewingkia'' is a genus of extinct Paleozoic coral

Corals are colonial marine invertebrates within the subphylum Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact Colony (biology), colonies of many identical individual polyp (zoo ...

'') in three views; Ordovician, southeastern Indiana

Modern corals

The currently ubiquitous stony corals,Scleractinia

Scleractinia, also called stony corals or hard corals, are marine animals in the phylum Cnidaria that build themselves a hard skeleton. The individual animals are known as polyps and have a cylindrical body crowned by an oral disc in which a mo ...

, appeared in the Middle Triassic

In the geologic timescale, the Middle Triassic is the second of three epoch (geology), epochs of the Triassic period (geology), period or the middle of three series (stratigraphy), series in which the Triassic system (stratigraphy), system is di ...

to fill the niche vacated by the extinct rugose and tabulate orders and is not closely related to the earlier forms. Unlike the corals prevalent before the Permian extinction, which formed skeletons of a form of calcium carbonate known as calcite

Calcite is a Carbonate minerals, carbonate mineral and the most stable Polymorphism (materials science), polymorph of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of limestone. Calcite defines hardness 3 on ...

, modern stony corals form skeletons composed of the aragonite