Classis Alexandriae on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The naval forces of the ancient Roman state () were instrumental in the Roman conquest of the Mediterranean Basin, but it never enjoyed the prestige of the

Despite the massive buildup, the Roman crews remained inferior in naval experience to the Carthaginians, and could not hope to match them in

Despite the massive buildup, the Roman crews remained inferior in naval experience to the Carthaginians, and could not hope to match them in

In the absence of a strong naval presence however,

In the absence of a strong naval presence however,

The last major campaigns of the Roman navy in the Mediterranean until the late 3rd century AD would be in the

The last major campaigns of the Roman navy in the Mediterranean until the late 3rd century AD would be in the  Octavian's power was further enhanced after his victory against the combined fleets of

Octavian's power was further enhanced after his victory against the combined fleets of

The bulk of a galley's crew was formed by the rowers, the (sing. ) or (sing. ) in Greek. Despite popular perceptions, the Roman fleet, and ancient fleets in general, relied throughout their existence on rowers of free status, and not on

The bulk of a galley's crew was formed by the rowers, the (sing. ) or (sing. ) in Greek. Despite popular perceptions, the Roman fleet, and ancient fleets in general, relied throughout their existence on rowers of free status, and not on

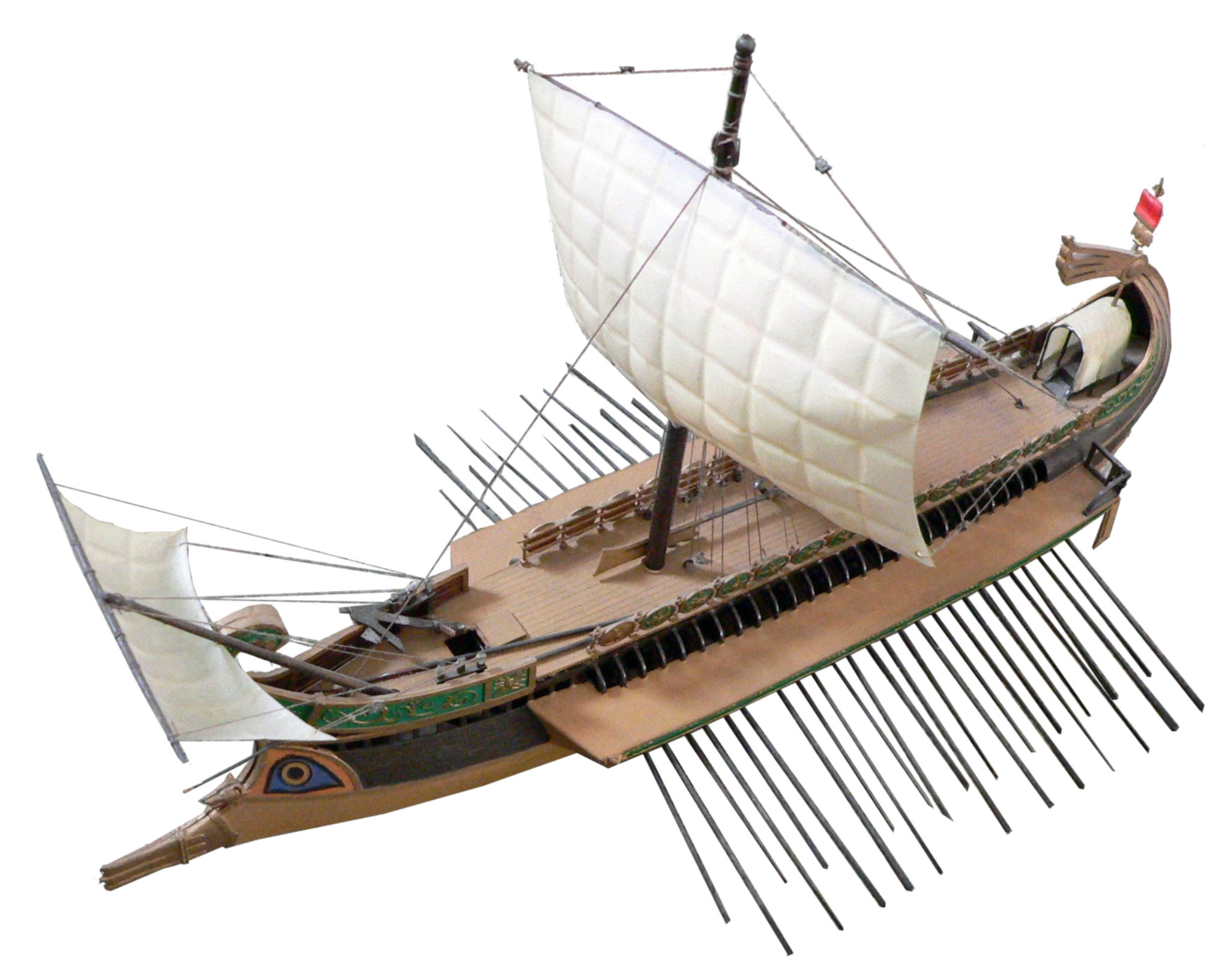

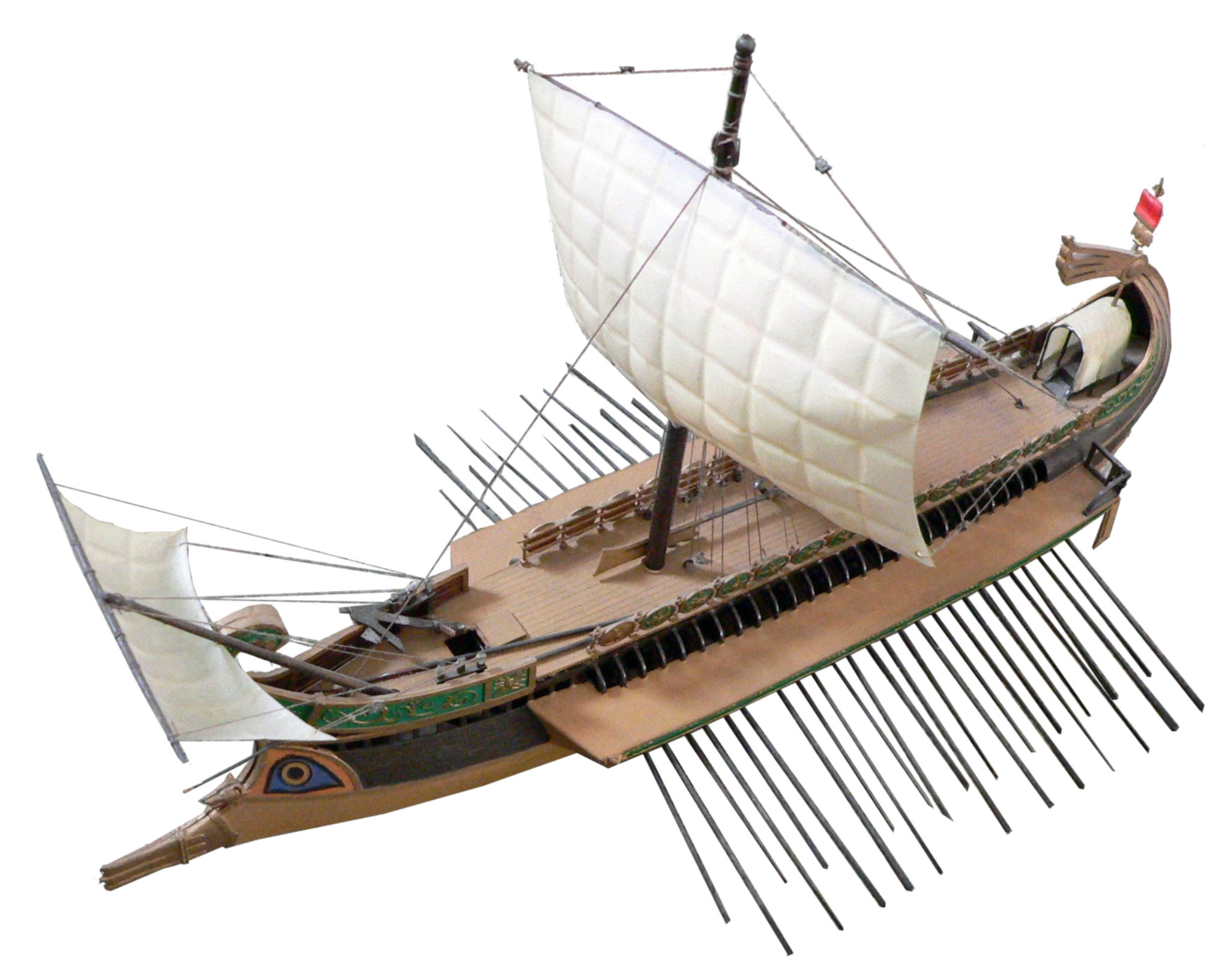

The generic Roman term for an oar-driven galley warship was "long ship" (Latin: ''navis longa'', Greek: ''naus makra''), as opposed to the sail-driven ''navis oneraria'' (from ''onus, oneris: burden''), a merchant vessel, or the minor craft (''navigia minora'') like the ''scapha''.

The navy consisted of a wide variety of different classes of warships, from heavy polyremes to light raiding and scouting vessels. Unlike the rich Hellenistic Successor kingdoms in the East however, the Romans did not rely on heavy warships, with

The generic Roman term for an oar-driven galley warship was "long ship" (Latin: ''navis longa'', Greek: ''naus makra''), as opposed to the sail-driven ''navis oneraria'' (from ''onus, oneris: burden''), a merchant vessel, or the minor craft (''navigia minora'') like the ''scapha''.

The navy consisted of a wide variety of different classes of warships, from heavy polyremes to light raiding and scouting vessels. Unlike the rich Hellenistic Successor kingdoms in the East however, the Romans did not rely on heavy warships, with  This prominence of lighter craft in the historical narrative is perhaps best explained in light of subsequent developments. After Actium, the operational landscape had changed: for the remainder of the Principate, no opponent existed to challenge Roman naval hegemony, and no massed naval confrontation was likely. The tasks at hand for the Roman navy were now the policing of the Mediterranean waterways and the border rivers, suppression of piracy, and escort duties for the grain shipments to Rome and for imperial army expeditions. Lighter ships were far better suited to these tasks, and after the reorganization of the fleet following Actium, the largest ship kept in service was a hexareme, the flagship of the ''

This prominence of lighter craft in the historical narrative is perhaps best explained in light of subsequent developments. After Actium, the operational landscape had changed: for the remainder of the Principate, no opponent existed to challenge Roman naval hegemony, and no massed naval confrontation was likely. The tasks at hand for the Roman navy were now the policing of the Mediterranean waterways and the border rivers, suppression of piracy, and escort duties for the grain shipments to Rome and for imperial army expeditions. Lighter ships were far better suited to these tasks, and after the reorganization of the fleet following Actium, the largest ship kept in service was a hexareme, the flagship of the ''

In

In

After the end of the civil wars, Augustus reduced and reorganized the Roman armed forces, including the navy. A large part of the fleet of Mark Antony was burned, and the rest was withdrawn to a new base at Forum Iulii (modern Fréjus), which remained operative until the reign of Claudius. However, the bulk of the fleet was soon subdivided into two praetorian fleets at Misenum and Ravenna, supplemented by a growing number of minor ones in the provinces, which were often created on an ''ad hoc'' basis for specific campaigns. This organizational structure was maintained almost unchanged until the 4th century.

After the end of the civil wars, Augustus reduced and reorganized the Roman armed forces, including the navy. A large part of the fleet of Mark Antony was burned, and the rest was withdrawn to a new base at Forum Iulii (modern Fréjus), which remained operative until the reign of Claudius. However, the bulk of the fleet was soon subdivided into two praetorian fleets at Misenum and Ravenna, supplemented by a growing number of minor ones in the provinces, which were often created on an ''ad hoc'' basis for specific campaigns. This organizational structure was maintained almost unchanged until the 4th century.

The ''Classis Pannonica'' and the ''Classis Moesica'' (at the beginning of the 5th century) were broken up into several smaller squadrons, collectively termed ''Classis Histrica'', authority of the frontier commanders (''dux, duces''). with bases at Mursa in Pannonia II,''Notitia Dignitatum''

The ''Classis Pannonica'' and the ''Classis Moesica'' (at the beginning of the 5th century) were broken up into several smaller squadrons, collectively termed ''Classis Histrica'', authority of the frontier commanders (''dux, duces''). with bases at Mursa in Pannonia II,''Notitia Dignitatum''

''Pars Occ.'', XXXII.

/ref> Florentia in Pannonia Valeria,''Notitia Dignitatum''

''Pars Occ.'', XXXIII.

/ref> Arruntum in Pannonia I,''Notitia Dignitatum''

''Pars Occ.'', XXXIV.

/ref> Viminacium in Moesia I''Notitia Dignitatum''

''Pars Orient.'', XLI.

/ref> and Aegetae in Dacia ripensis.''Notitia Dignitatum''

''Pars Orient.'', XLII.

/ref> Smaller fleets are also attested on the tributaries of the Danube: the ''Classis Arlapensis et Maginensis'' (based at Pöchlarn, Arelape and Comagena) and the ''Classis Lauriacensis'' (based at Enns (city), Lauriacum) in Pannonia I, the ''Classis Stradensis et Germensis'', based at Margo in Moesia I, and the ''Classis Ratianensis'', in Dacia ripensis. The naval units were complemented by port garrisons and marine units, drawn from the army. In the Danube frontier these were: * In Pannonia I and Noricum ripensis, naval detachments (''milites liburnarii'') of the Legio XIV Gemina, ''legio'' XIV ''Gemina'' and the Legio X Gemina, ''legio'' X ''Gemina'' at Carnuntum and Arrabonae, and of the Legio II Italica, ''legio'' II ''Italica'' at Ioviacum. * In Pannonia II, the I ''Flavia Augusta'' (at Sirmium) and the II ''Flavia'' are listed under their prefects. * In Moesia II, two units of sailors (''milites nauclarii'') at Appiaria and Altinum.''Notitia Dignitatum''

''Pars Orient.'', XL.

/ref> * In Scythia Minor (Roman province), Scythia Minor, marines (''muscularii'') of Legio II Herculia, ''legio'' II ''Herculia'' at Inplateypegiis and sailors (''nauclarii'') at Flaviana.''Notitia Dignitatum''

''Pars Orient.'', XXXIX.

/ref>

''Pars Occ.'', XLII.

/ref> * The ''Classis Anderetianorum'', based at Parisii (Paris) and operating in the Seine and Oise River, Oise rivers. * The ''Classis Ararica'', based at Caballodunum (Chalon-sur-Saône) and operating in the Saône River. * A ''Classis barcariorum'', composed of small vessels, at Eburodunum (modern Yverdon-les-Bains) at Lake Neuchâtel. * The ''Classis Comensis'' at Lake Como. * The old praetorian fleets, the ''Classis Misenatis'' and the ''Classis Ravennatis'' are still listed, albeit with no distinction indicating any higher importance than the other fleets. The "praetorian" surname is still attested until the early 4th century, but absent from

''Pars Occ.'', XXXVIII.

/ref> * The ''Classis Venetum'', based at Aquileia and operating in the northern Adriatic Sea. This fleet may have been established to ensure communications with the imperial capitals in the Po Valley (Ravenna and Milan) and with Dalmatia (Roman province), Dalmatia. It is notable that, with the exception of the praetorian fleets (whose retention in the list does not necessarily signify an active status), the old fleets of the Principate are missing. The ''Classis Britannica'' vanishes under that name after the mid-3rd century; its remnants were later subsumed in the Saxon Shore system.

By the time of the ''Notitia Dignitatum'', the ''Classis Germanica'' has ceased to exist (it is last mentioned under Julian the Apostate, Julian in 359), most probably due to the collapse of the Limes Germanicus, Rhine frontier after the Crossing of the Rhine by the barbarians in winter 405–406, and the Mauretanian and African fleets had been disbanded or taken over by the Vandals.

It is notable that, with the exception of the praetorian fleets (whose retention in the list does not necessarily signify an active status), the old fleets of the Principate are missing. The ''Classis Britannica'' vanishes under that name after the mid-3rd century; its remnants were later subsumed in the Saxon Shore system.

By the time of the ''Notitia Dignitatum'', the ''Classis Germanica'' has ceased to exist (it is last mentioned under Julian the Apostate, Julian in 359), most probably due to the collapse of the Limes Germanicus, Rhine frontier after the Crossing of the Rhine by the barbarians in winter 405–406, and the Mauretanian and African fleets had been disbanded or taken over by the Vandals.

The Roman Navy: Ships, Men and Warfare 350 BC–AD 475

Pen and Sword. .''

The Imperial fleet of Misenum

''Roman-Empire.net''

''HistoryNet.com'' *

' o

*

', the museum of Roman merchant ships found in Fiumicino (Rome) *

Diana Nemorensis

', Caligula's ships in the lake of Nemi.

* [http://terraromana.org/navis/Forum/index.php Forum Navis Romana] {{Authority control Navy of ancient Rome, Military history of ancient Rome, Navy

Roman legion

The Roman legion (, ) was the largest military List of military legions, unit of the Roman army, composed of Roman citizenship, Roman citizens serving as legionary, legionaries. During the Roman Republic the manipular legion comprised 4,200 i ...

s. Throughout their history, the Romans remained a primarily land-based people and relied partially on their more nautically inclined subjects, such as the Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

and the Egyptians

Egyptians (, ; , ; ) are an ethnic group native to the Nile, Nile Valley in Egypt. Egyptian identity is closely tied to Geography of Egypt, geography. The population is concentrated in the Nile Valley, a small strip of cultivable land stretchi ...

, to build their ships. Because of that, the navy was never completely embraced by the Roman state, and deemed somewhat "un-Roman".

In antiquity, navies and trading fleets did not have the logistical autonomy that modern ships and fleets possess, and unlike modern naval forces, the Roman navy even at its height never existed as an autonomous service but operated as an adjunct to the Roman army

The Roman army () served ancient Rome and the Roman people, enduring through the Roman Kingdom (753–509 BC), the Roman Republic (509–27 BC), and the Roman Empire (27 BC–AD 1453), including the Western Roman Empire (collapsed Fall of the W ...

.

During the course of the First Punic War

The First Punic War (264–241 BC) was the first of three wars fought between Rome and Carthage, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the early 3rd century BC. For 23 years, in the longest continuous conflict and grea ...

, the Roman navy was massively expanded and played a vital role in the Roman victory and the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

's eventual ascension to hegemony in the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

. In the course of the first half of the 2nd century BC, Rome went on to destroy Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

and subdue the Hellenistic

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

kingdoms of the eastern Mediterranean, achieving complete mastery of the inland sea, which they called ''Mare Nostrum

In the Roman Empire, () was a term that referred to the Mediterranean Sea. Meaning "Our Sea" in Latin, it denoted the body of water in the context of borders and policy; Ancient Rome, Rome remains the only state in history to have controlled th ...

''. The Roman fleets were again prominent in the 1st century BC in the wars against the pirates, and in the civil wars that brought down the Republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

, whose campaigns ranged across the Mediterranean. In 31 BC, the great naval Battle of Actium

The Battle of Actium was a naval battle fought between Octavian's maritime fleet, led by Marcus Agrippa, and the combined fleets of both Mark Antony and Cleopatra. The battle took place on 2 September 31 BC in the Ionian Sea, near the former R ...

ended the civil wars

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.James Fearon"Iraq' ...

culminating in the final victory of Augustus

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in A ...

and the establishment of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

.

During the Imperial period, the Mediterranean became largely a peaceful "Roman lake". In the absence of a maritime enemy, the navy was reduced mostly to patrol, anti-piracy and transport duties. By far, the navy's most vital task was to ensure Roman grain imports were shipped and delivered to the capital unimpeded across the Mediterranean. The navy also manned and maintained craft on major frontier rivers such as the Rhine

The Rhine ( ) is one of the List of rivers of Europe, major rivers in Europe. The river begins in the Swiss canton of Graubünden in the southeastern Swiss Alps. It forms part of the Swiss-Liechtenstein border, then part of the Austria–Swit ...

and the Danube

The Danube ( ; see also #Names and etymology, other names) is the List of rivers of Europe#Longest rivers, second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest sou ...

for supplying the army and preventing crossings by enemies.

On the fringes of the Empire, in new conquests or, increasingly, in defense against barbarian

A barbarian is a person or tribe of people that is perceived to be primitive, savage and warlike. Many cultures have referred to other cultures as barbarians, sometimes out of misunderstanding and sometimes out of prejudice.

A "barbarian" may ...

invasions, the Roman fleets were still engaged in open warfare. The decline of the Empire in the 3rd century took a heavy toll on the navy, which was reduced to a shadow of its former self, both in size and in combat ability. As successive waves of the Migration Period

The Migration Period ( 300 to 600 AD), also known as the Barbarian Invasions, was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories ...

crashed on the land frontiers of the battered Empire, the navy could only play a secondary role. In the early 5th century, the Roman frontiers were breached, and barbarian kingdoms appeared on the shores of the western Mediterranean. One of them, the Vandal Kingdom

The Vandal Kingdom () or Kingdom of the Vandals and Alans () was a confederation of Vandals and Alans, which was a barbarian kingdoms, barbarian kingdom established under Gaiseric, a Vandals, Vandalic warlord. It ruled parts of North Africa and th ...

with its capital at Carthage, raised a navy of its own and raided the shores of the Mediterranean, even sacking Rome, while the diminished Roman fleets were incapable of offering any resistance. The Western Roman Empire

In modern historiography, the Western Roman Empire was the western provinces of the Roman Empire, collectively, during any period in which they were administered separately from the eastern provinces by a separate, independent imperial court. ...

collapsed in the late 5th century. The navy of the surviving Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

is known as the Byzantine navy

The Byzantine navy was the Navy, naval force of the Byzantine Empire. Like the state it served, it was a direct continuation from its Roman navy, Roman predecessor, but played a far greater role in the defence and survival of the state than its ...

.

History

Early Republic

The exact origins of the Roman fleet are obscure. A traditionally agricultural and land-based society, the Romans rarely ventured out to sea, unlike theirEtruscan __NOTOC__

Etruscan may refer to:

Ancient civilization

*Etruscan civilization (1st millennium BC) and related things:

**Etruscan language

** Etruscan architecture

**Etruscan art

**Etruscan cities

**Etruscan coins

**Etruscan history

**Etruscan myt ...

neighbours. There is evidence of Roman warships in the early 4th century BC, such as mention of a warship that carried an embassy to Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), was an ancient sacred precinct and the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient Classical antiquity, classical world. The A ...

in 394 BC, but at any rate, the Roman fleet, if it existed, was negligible. The traditional birth date of the Roman navy is set at ca. 311 BC, when, after the conquest of Campania

Campania is an administrative Regions of Italy, region of Italy located in Southern Italy; most of it is in the south-western portion of the Italian Peninsula (with the Tyrrhenian Sea to its west), but it also includes the small Phlegraean Islan ...

, two new officials, the ''duumviri navales

The Duumviri navales, , were two naval officers elected by the people of Rome to repair and equip the Roman fleet. Both Duumviri navales were assigned to one Roman consul, and each controlled 20 ships. It has been suggested that they may have been ...

classis ornandae reficiendaeque causa'', were tasked with the maintenance of a fleet. As a result, the Republic acquired its first fleet, consisting of 20 ships, most likely trireme

A trireme ( ; ; cf. ) was an ancient navies and vessels, ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizations of the Mediterranean Sea, especially the Phoenicians, ancient Greece, ancient Greeks and ancient R ...

s, with each ''duumvir'' commanding a squadron of 10 ships. However, the Republic continued to rely mostly on her legions for expansion in Italy; the navy was most likely geared towards combating piracy and lacked experience in naval warfare, being easily defeated in 282 BC by the Tarentines.

This situation continued until the First Punic War

The First Punic War (264–241 BC) was the first of three wars fought between Rome and Carthage, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the early 3rd century BC. For 23 years, in the longest continuous conflict and grea ...

: the main task of the Roman fleet was patrolling along the Italian coast and rivers, protecting seaborne trade from piracy. Whenever larger tasks had to be undertaken, such as the naval blockade of a besieged city, the Romans called on the allied Greek cities of southern Italy, the '' socii navales'', to provide ships and crews. It is possible that the supervision of these maritime allies was one of the duties of the four new '' praetores classici'', who were established in 267 BC.

First Punic War

The first Roman expedition outside mainland Italy was against the island ofSicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

in 265 BC. This led to the outbreak of hostilities with Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

, which would last until 241 BC. At the time, the Punic

The Punic people, usually known as the Carthaginians (and sometimes as Western Phoenicians), were a Semitic people who migrated from Phoenicia to the Western Mediterranean during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' ...

city was the unchallenged master of the western Mediterranean, possessing a long maritime and naval experience and a large fleet. Although Rome had relied on her legions for the conquest of Italy, operations in Sicily had to be supported by a fleet, and the ships available by Rome's allies were insufficient. Thus in 261 BC, the Roman Senate

The Roman Senate () was the highest and constituting assembly of ancient Rome and its aristocracy. With different powers throughout its existence it lasted from the first days of the city of Rome (traditionally founded in 753 BC) as the Sena ...

set out to construct a fleet of 100 quinquereme

From the 4th century BC on, new types of oared warships appeared in the Mediterranean Sea, superseding the trireme and transforming naval warfare. Ships became increasingly large and heavy, including some of the largest wooden ships hitherto con ...

s and 20 triremes. According to Polybius

Polybius (; , ; ) was a Greek historian of the middle Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , a universal history documenting the rise of Rome in the Mediterranean in the third and second centuries BC. It covered the period of 264–146 ...

, the Romans seized a shipwrecked Carthaginian quinquereme, and used it as a blueprint for their own ships. The new fleets were commanded by the annually elected Roman magistrates

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a ''magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judici ...

, but naval expertise was provided by the lower officers, who continued to be provided by the ''socii'', mostly Greeks. This practice was continued until well into the Empire, something also attested by the direct adoption of numerous Greek naval terms.

Despite the massive buildup, the Roman crews remained inferior in naval experience to the Carthaginians, and could not hope to match them in

Despite the massive buildup, the Roman crews remained inferior in naval experience to the Carthaginians, and could not hope to match them in naval tactics

Naval tactics and doctrine is the collective name for methods of engaging and defeating an enemy ship or fleet in battle at sea during naval warfare, the naval equivalent of military tactics on land.

Naval tactics are distinct from naval strat ...

, which required great maneuverability and experience. They, therefore, employed a novel weapon that transformed sea warfare to their advantage. They equipped their ships with the ''corvus

''Corvus'' is a widely distributed genus of passerine birds ranging from medium-sized to large-sized in the family Corvidae. It includes species commonly known as crows, ravens, and rooks. The species commonly encountered in Europe are the car ...

'', possibly developed earlier by the Syracusans against the Athenians

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

. This was a long plank with a spike for hooking onto enemy ships. Using it as a boarding bridge, marines were able to board

Board or Boards may refer to:

Flat surface

* Lumber, or other rigid material, milled or sawn flat

** Plank (wood)

** Cutting board

** Sounding board, of a musical instrument

* Cardboard (paper product)

* Paperboard

* Fiberboard

** Hardboard, a ...

an enemy ship, transforming sea combat into a version of land combat, where the Roman legionaries had the upper hand. However, it is believed that the ''Corvus'' weight made the ships unstable, and could capsize a ship in rough seas.

Although the first sea engagement of the war, the Battle of the Lipari Islands

The Battle of the Lipari Islands or Battle of Lipara was a naval encounter fought in 260 BC during the First Punic War. A squadron of 20 Carthaginian ships commanded by Boödes surprised 17 Roman ships under the senior consul for the year ...

in 260 BC, was a defeat for Rome, the forces involved were relatively small. Through the use of the ''Corvus'', the fledgling Roman navy under Gaius Duilius

Gaius Duilius ( 260–231 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. As consul in 260 BC, during the First Punic War, he won Rome's first ever victory at sea by defeating the Carthaginians at the Battle of Mylae. He later served as censor in 258, a ...

won its first major engagement later that year at the Battle of Mylae

The Battle of Mylae took place in 260 BC during the First Punic War and was the first real naval battle between Carthage and the Roman Republic. This battle was key in the Roman victory of Mylae (present-day Milazzo) as well as Sicily itself. ...

. During the course of the war, Rome continued to be victorious at sea: victories at Sulci

Sulci or Sulki (in Greek , Stephanus of Byzantium, Steph. B., Ptolemy, Ptol.; , Strabo; , Pausanias (geographer), Paus.), was one of the most considerable cities of ancient Sardinia, situated in the southwest corner of the island, on a small isla ...

(258 BC) and Tyndaris

Tindari (; ), ancient Tyndaris (, Strab.) or Tyndarion (, Ptol.), is a small town, ''frazione'' (suburb or municipal component) in the ''comune'' of Patti and a Latin Catholic titular see.

The monumental ruins of ancient Tyndaris are a main ...

(257 BC) were followed by the massive Battle of Cape Ecnomus

The Battle of Cape Ecnomus or Eknomos () was a naval battle, fought off southern Sicily, in 256 BC, between the fleets of Carthage (state), Carthage and the Roman Republic, during the First Punic War (264–241 BC). The Carthaginian fleet was c ...

, where the Roman fleet under the consuls Marcus Atilius Regulus

Marcus Atilius Regulus () was a Roman statesman and general who was a consul of the Roman Republic in 267 BC and 256 BC. Much of his career was spent fighting the Carthaginians during the first Punic War. In 256 BC, he and Lucius ...

and Lucius Manlius

Lucius Manlius Torquatus was a consul of the Roman Republic in 65 BC, elected after the condemnation of Publius Cornelius Sulla and Publius Autronius Paetus.

Biography

Torquatus belonged to the patrician gens Manlii, one of the oldest Roman ...

inflicted a severe defeat on the Carthaginians. This string of successes allowed Rome to push the war further across the sea to Africa and Carthage itself. Continued Roman success also meant that their navy gained significant experience, although it also suffered a number of catastrophic losses due to storms, while conversely, the Carthaginian navy suffered from attrition.

The Battle of Drepana

The naval Battle of Drepana (or Drepanum) took place in 249 BC during the First Punic War near Drepana (modern Trapani) in western Sicily, between a Carthaginian fleet under Adherbal and a Roman fleet commanded by Publius Claudius Pulch ...

in 249 BC resulted in the only major Carthaginian sea victory, forcing the Romans to equip a new fleet from donations by private citizens. In the last battle of the war, at Aegates Islands in 241 BC, the Romans under Gaius Lutatius Catulus

Gaius Lutatius Catulus ( 242–241 BC) was a ancient Rome, Roman statesman and Commander, naval commander in the First Punic War. He was born a member of the plebeian gens Lutatius. His Roman naming conventions, cognomen "Catulus" means "puppy" ...

displayed superior seamanship to the Carthaginians, notably using their rams rather than the now-abandoned ''Corvus'' to achieve victory.

Illyria and the Second Punic War

After the Roman victory, the balance of naval power in the Western Mediterranean had shifted from Carthage to Rome. This ensured Carthaginian acquiescence to the conquest ofSardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

and Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...

, and also enabled Rome to deal decisively with the threat posed by the Illyria

In classical and late antiquity, Illyria (; , ''Illyría'' or , ''Illyrís''; , ''Illyricum'') was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by numerous tribes of people collectively known as the Illyrians.

The Ancient Gree ...

n pirates in the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

. The Illyrian Wars

The Illyrian Wars were a series of wars fought between the Roman Republic and the Illyrian kingdom under the Ardiaei and Labeatae. In the ''First Illyrian War'', which lasted from 229 BC to 228 BC, Rome's concern was that the trade across the Adr ...

marked Rome's first involvement with the affairs of the Balkan peninsula. Initially, in 229 BC, a fleet of 200 warships was sent against Queen Teuta

Teuta ( Illyrian: ''*Teutana'', 'mistress of the people, queen'; ; ) was the queen regent of the Ardiaei tribe in Illyria, who reigned approximately from 231 BC to 228/227 BC.

Following the death of her spouse Agron in 231 BC, she assumed ...

, and swiftly expelled the Illyrian garrisons from the Greek coastal cities of modern-day Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

. Ten years later, the Romans sent another expedition in the area against Demetrius of Pharos

Demetrius of Pharos (also Pharus; ) was a ruler of Pharos involved in the First Illyrian War, after which he ruled a portion of the Illyrian Adriatic coast on behalf of the Romans, as a client king.

Demetrius was a regent ruler to Pinnes, ...

, who had rebuilt the Illyrian navy and engaged in piracy up into the Aegean. Demetrius was supported by Philip V of Macedon

Philip V (; 238–179 BC) was king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon from 221 to 179 BC. Philip's reign was principally marked by the Social War (220–217 BC), Social War in Greece (220-217 BC) ...

, who had grown anxious at the expansion of Roman power in Illyria. The Romans were again quickly victorious and expanded their Illyrian protectorate, but the beginning of the Second Punic War

The Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) was the second of Punic Wars, three wars fought between Ancient Carthage, Carthage and Roman Republic, Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean Basin, Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. For ...

(218–201 BC) forced them to divert their resources westwards for the next decades.

Due to Rome's command of the seas, Hannibal

Hannibal (; ; 247 – between 183 and 181 BC) was a Punic people, Carthaginian general and statesman who commanded the forces of Ancient Carthage, Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic during the Second Punic War.

Hannibal's fat ...

, Carthage's great general, was forced to eschew a sea-borne invasion, instead choosing to bring the war over land to the Italian peninsula. Unlike the first war, the navy played little role on either side in this war. The only naval encounters occurred in the first years of the war, at Lilybaeum

Marsala (, ; ) is an Italian comune located in the Province of Trapani in the westernmost part of Sicily. Marsala is the most populated town in its province and the fifth largest in Sicily.The town is famous for the docking of Giuseppe Garibald ...

(218 BC) and the Ebro River

The Ebro (Spanish and Basque ; , , ) is a river of the north and northeast of the Iberian Peninsula, in Spain. It rises in Cantabria and flows , almost entirely in an east-southeast direction. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea, forming a del ...

(217 BC), both resulting Roman victories. Despite an overall numerical parity, for the remainder of the war the Carthaginians did not seriously challenge Roman supremacy. The Roman fleet was hence engaged primarily with raiding the shores of Africa and guarding Italy, a task which included the interception of Carthaginian convoys of supplies and reinforcements for Hannibal's army, as well as keeping an eye on a potential intervention by Carthage's ally, Philip V. The only major action in which the Roman fleet was involved was the siege of Syracuse in 214–212 BC with 130 ships under Marcus Claudius Marcellus

Marcus Claudius Marcellus (; 270 – 208 BC) was a Roman general and politician during the 3rd century BC. Five times elected as Roman consul, consul of the Roman Republic (222, 215, 214, 210, and 208 BC). Marcellus gained the most prestigious a ...

. The siege is remembered for the ingenious inventions of Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse ( ; ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Greek mathematics, mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and Invention, inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse, Sicily, Syracuse in History of Greek and Hellenis ...

, such as mirrors that burned ships or the so-called "Claw of Archimedes

The Claw of Archimedes (; also known as the iron hand) was an ancient weapon devised by Archimedes to defend the seaward portion of Syracuse's city wall against amphibious assault. Although its exact nature is unclear, the accounts of ancient h ...

", which kept the besieging army at bay for two years. A fleet of 160 vessels was assembled to support Scipio Africanus

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus (, , ; 236/235–) was a Roman general and statesman who was one of the main architects of Rome's victory against Ancient Carthage, Carthage in the Second Punic War. Often regarded as one of the greatest milit ...

' army in Africa in 202 BC, and, should his expedition fail, evacuate his men. In the event, Scipio achieved a decisive victory at Zama, and the subsequent peace stripped Carthage of its fleet.

Operations in the East

Rome was now the undisputed master of the Western Mediterranean, and turned her gaze from defeated Carthage to theHellenistic

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

world. Small Roman forces had already been engaged in the First Macedonian War, when, in 214 BC, a fleet under Marcus Valerius Laevinus

Marcus Valerius Laevinus (c. 260 BC200 BC) was a Roman consul and commander who rose to prominence during the Second Punic War and corresponding First Macedonian War. A member of the '' gens Valeria'', an old patrician family believed to have mig ...

had successfully thwarted Philip V from invading Illyria with his newly built fleet. The rest of the war was carried out mostly by Rome's allies, the Aetolian League

The Aetolian (or Aitolian) League () was a confederation of tribal communities and cities in ancient Greece centered in Aetolia in Central Greece. It was probably established during the early Hellenistic era, in opposition to Macedon and the Ac ...

and later the Kingdom of Pergamon

The Kingdom of Pergamon, Pergamene Kingdom, or Attalid kingdom was a Greek state during the Hellenistic period that ruled much of the Western part of Asia Minor from its capital city of Pergamon. It was ruled by the Attalid dynasty (; ).

The k ...

, but a combined Roman–Pergamene fleet of ca. 60 ships patrolled the Aegean until the war's end in 205 BC. In this conflict, Rome, still embroiled in the Punic War, was not interested in expanding her possessions, but rather in thwarting the growth of Philip's power in Greece. The war ended in an effective stalemate, and was renewed in 201 BC, when Philip V invaded Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

. A naval battle

Naval warfare is combat in and on the sea, the ocean, or any other battlespace involving a major body of water such as a large lake or wide river.

The armed forces branch designated for naval warfare is a navy. Naval operations can be broadly d ...

off Chios

Chios (; , traditionally known as Scio in English) is the fifth largest Greece, Greek list of islands of Greece, island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea, and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, tenth largest island in the Medi ...

ended in a costly victory for the Pergamene–Rhodian

Rhodes (; ) is the largest of the Dodecanese islands of Greece and is their historical capital; it is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, ninth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Administratively, the island forms a separ ...

alliance, but the Macedonian fleet lost many warships, including its flagship, a ''deceres''. Soon after, Pergamon and Rhodes appealed to Rome for help, and the Republic was drawn into the Second Macedonian War

The Second Macedonian War (200–197 BC) was fought between Macedon, led by Philip V of Macedon, and Rome, allied with Pergamon and Rhodes. Philip was defeated and was forced to abandon all possessions in southern Greece, Thrace and Asia Minor. ...

. In view of the massive Roman naval superiority, the war was fought on land, with the Macedonian fleet, already weakened at Chios, not daring to venture out of its anchorage at Demetrias

Demetrias () was a Greek city in Magnesia in ancient Thessaly (east central Greece), situated at the head of the Pagasaean Gulf, near the modern city of Volos.

History

It was founded in 294 BCE by Demetrius Poliorcetes, who removed th ...

. After the crushing Roman victory at Cynoscephalae, the terms imposed on Macedon were harsh, and included the complete disbandment of her navy.

Almost immediately following the defeat of Macedon

Macedonia ( ; , ), also called Macedon ( ), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, which later became the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by the royal ...

, Rome became embroiled in a war

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or between such organi ...

with the Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire ( ) was a Greek state in West Asia during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 312 BC by the Macedonian general Seleucus I Nicator, following the division of the Macedonian Empire founded by Alexander the Great ...

. This war too was decided mainly on land, although the combined Roman–Rhodian navy also achieved victories over the Seleucids at Myonessus

Myonessus or Myonessos () was a town of ancient Ionia, located near Teos and Lebedus. It was situated on promontory of the same name. An island also called Myonessus stood offshore. The location is noted for the naval battle offshore in 190 B ...

and Eurymedon. These victories, which were invariably concluded with the imposition of peace treaties that prohibited the maintenance of anything but token naval forces, spelled the disappearance of the Hellenistic royal navies, leaving Rome and her allies unchallenged at sea. Coupled with the final destruction of Carthage

The siege of Carthage was the main engagement of the Third Punic War fought between Ancient Carthage, Carthage and Roman Republic, Rome. It consisted of the nearly three-year siege of the Carthaginian capital, Carthage (a little northeast ...

, and the end of Macedon's independence, by the latter half of the 2nd century BC, Roman control over all of what was later to be dubbed ''mare nostrum

In the Roman Empire, () was a term that referred to the Mediterranean Sea. Meaning "Our Sea" in Latin, it denoted the body of water in the context of borders and policy; Ancient Rome, Rome remains the only state in history to have controlled th ...

'' ("our sea") had been established. Subsequently, the Roman navy was drastically reduced, depending on its Socii navales.

Late Republic

Mithridates and the pirate threat

In the absence of a strong naval presence however,

In the absence of a strong naval presence however, piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and valuable goods, or taking hostages. Those who conduct acts of piracy are call ...

flourished throughout the Mediterranean, especially in Cilicia

Cilicia () is a geographical region in southern Anatolia, extending inland from the northeastern coasts of the Mediterranean Sea. Cilicia has a population ranging over six million, concentrated mostly at the Cilician plain (). The region inclu ...

, but also in Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

and other places, further reinforced by money and warships supplied by King Mithridates VI of Pontus

Mithridates or Mithradates VI Eupator (; 135–63 BC) was the ruler of the Kingdom of Pontus in northern Anatolia from 120 to 63 BC, and one of the Roman Republic's most formidable and determined opponents. He was an effective, ambitious, and r ...

, who hoped to enlist their aid in his wars

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of State (polity), states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or betwe ...

against Rome. In the First Mithridatic War

The First Mithridatic War /ˌmɪθrəˈdædɪk/ (89–85 BC) was a war challenging the Roman Republic's expanding empire and rule over the Greek world. In this conflict, the Kingdom of Pontus and many Greek cities rebelling against Roman rule ...

(89–85 BC), Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (, ; 138–78 BC), commonly known as Sulla, was a Roman people, Roman general and statesman of the late Roman Republic. A great commander and ruthless politician, Sulla used violence to advance his career and his co ...

had to requisition ships wherever he could find them to counter Mithridates' fleet. Despite the makeshift nature of the Roman fleet however, in 86 BC Lucullus

Lucius Licinius Lucullus (; 118–57/56 BC) was a Ancient Romans, Roman List of Roman generals, general and Politician, statesman, closely connected with Lucius Cornelius Sulla. In culmination of over 20 years of almost continuous military and ...

defeated the Pontic

Pontic, from the Greek ''pontos'' (, ), or "sea", may refer to:

The Black Sea Places

* The Pontic colonies, on its northern shores

* Pontus (region), a region on its southern shores

* The Pontic–Caspian steppe, steppelands stretching from nor ...

navy at Tenedos

Tenedos (, ''Tenedhos''; ), or Bozcaada in Turkish language, Turkish, is an island of Turkey in the northeastern part of the Aegean Sea. Administratively, the island constitutes the Bozcaada, Çanakkale, Bozcaada district of Çanakkale Provinc ...

.

Immediately after the end of the war, a permanent force of ca. 100 vessels was established in the Aegean from the contributions of Rome's allied maritime states. Although sufficient to guard against Mithridates, this force was totally inadequate against the pirates, whose power grew rapidly. Over the next decade, the pirates defeated several Roman commanders, and raided unhindered even to the shores of Italy, reaching Rome's harbor, Ostia. According to the account of Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

, "the ships of the pirates numbered more than a thousand, and the cities captured by them four hundred." Their activity posed a growing threat for the Roman economy, and a challenge to Roman power: several prominent Romans, including two praetor

''Praetor'' ( , ), also ''pretor'', was the title granted by the government of ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected ''magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to disch ...

s with their retinue and the young Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

, were captured and held for ransom

Ransom refers to the practice of holding a prisoner or item to extort money or property to secure their release. It also refers to the sum of money paid by the other party to secure a captive's freedom.

When ransom means "payment", the word ...

. Perhaps most important of all, the pirates disrupted Rome's vital lifeline, namely the massive shipments of grain and other produce from Africa and Egypt that were needed to sustain the city's population.

The resulting grain shortages were a major political issue, and popular discontent threatened to become explosive. In 74 BC, with the outbreak of the Third Mithridatic War

The Third Mithridatic War (73–63 BC), the last and longest of the three Mithridatic Wars, was fought between Mithridates VI of Pontus and the Roman Republic. Both sides were joined by a great number of allies, dragging the entire east of th ...

, Marcus Antonius

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the ...

(the father of Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman people, Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the Crisis of the Roman Republic, transformation of the Roman Republic ...

) was appointed ''praetor'' with extraordinary ''imperium

In ancient Rome, ''imperium'' was a form of authority held by a citizen to control a military or governmental entity. It is distinct from '' auctoritas'' and '' potestas'', different and generally inferior types of power in the Roman Republic a ...

'' against the pirate threat, but signally failed in his task: he was defeated off Crete in 72 BC, and died shortly after. Finally, in 67 BC the ''Lex Gabinia

The ''lex Gabinia'' (Gabinian Law), ''lex de uno imperatore contra praedones instituendo'' (Law establishing a single commander against raiders) or ''lex de piratis persequendis'' (Law on pursuing the pirates) was an ancient Roman special law pas ...

'' was passed in the Plebeian Council, vesting Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey ( ) or Pompey the Great, was a Roman general and statesman who was prominent in the last decades of the Roman Republic. ...

with unprecedented powers and authorizing him to move against them. In a massive and concerted campaign, Pompey cleared the seas of the pirates in only three months. Afterwards, the fleet was reduced again to policing duties against intermittent piracy.

Caesar and the Civil Wars

In 56 BC, for the first time a Roman fleet engaged in battle outside the Mediterranean. This occurred duringJulius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

's Gallic Wars

The Gallic Wars were waged between 58 and 50 BC by the Roman general Julius Caesar against the peoples of Gaul (present-day France, Belgium, and Switzerland). Gauls, Gallic, Germanic peoples, Germanic, and Celtic Britons, Brittonic trib ...

, when the maritime tribe of the Veneti rebelled against Rome. Against the Veneti, the Romans were at a disadvantage, since they did not know the coast, and were inexperienced in fighting in the open sea with its tides and currents. Furthermore, the Veneti ships were superior to the light Roman galleys. They were built of oak

An oak is a hardwood tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' of the beech family. They have spirally arranged leaves, often with lobed edges, and a nut called an acorn, borne within a cup. The genus is widely distributed in the Northern Hemisp ...

and had no oars, being thus more resistant to ramming

In warfare, ramming is a technique used in air, sea, and land combat. The term originated from battering ram, a siege engine used to bring down fortifications by hitting it with the force of the ram's momentum, and ultimately from male sheep. Thus ...

. In addition, their greater height gave them an advantage in both missile exchanges and boarding actions. In the event, when the two fleets encountered each other in Quiberon Bay

Quiberon Bay (, ; ) is an area of sheltered water on the south coast of Brittany. The bay is in the Morbihan département.

Geography

The bay is roughly triangular in shape, open to the south with the Gulf of Morbihan to the north-east and the ...

, Caesar's navy, under the command of D. Brutus, resorted to the use of hooks on long poles, which cut the halyard

In sailing, a halyard or halliard is a line (rope) that is used to hoist a ladder, sail, flag or yard. The term "halyard" derives from the Middle English ''halier'' ("rope to haul with"), with the last syllable altered by association with the E ...

s supporting the Veneti sails. Immobile, the Veneti ships were easy prey for the legionaries who boarded them, and fleeing Veneti ships were taken when they became becalmed by a sudden lack of winds. Having thus established his control of the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

, in the next years Caesar used this newly built fleet to carry out two invasions of Britain.

The last major campaigns of the Roman navy in the Mediterranean until the late 3rd century AD would be in the

The last major campaigns of the Roman navy in the Mediterranean until the late 3rd century AD would be in the civil wars

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.James Fearon"Iraq' ...

that ended the Republic. In the East, the Republican faction quickly established its control, and Rhodes, the last independent maritime power in the Aegean, was subdued by Gaius Cassius Longinus

Gaius Cassius Longinus (; – 3 October 42 BC) was a Roman senator and general best known as a leading instigator of the plot to assassinate Julius Caesar on 15 March 44 BC. He was the brother-in-law of Brutus, another leader of the conspir ...

in 43 BC, after its fleet was defeated off Kos

Kos or Cos (; ) is a Greek island, which is part of the Dodecanese island chain in the southeastern Aegean Sea. Kos is the third largest island of the Dodecanese, after Rhodes and Karpathos; it has a population of 37,089 (2021 census), making ...

. In the West, against the triumvirs stood Sextus Pompeius

Sextus Pompeius Magnus Pius ( 67 – 35 BC), also known in English as Sextus Pompey, was a Roman military leader who, throughout his life, upheld the cause of his father, Pompey the Great, against Julius Caesar and his supporters during the la ...

, who had been given command of the Italian fleet by the Senate in 43 BC. He took control of Sicily and made it his base, blockading Italy and stopping the politically crucial supply of grain from Africa to Rome. After suffering a defeat from Sextus in 42 BC, Octavian

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in ...

initiated massive naval armaments, aided by his closest associate, Marcus Agrippa

Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa (; BC – 12 BC) was a Roman general, statesman and architect who was a close friend, son-in-law and lieutenant to the Roman emperor Augustus. Agrippa is well known for his important military victories, notably the Ba ...

: ships were built at Ravenna and Ostia, the new artificial harbor of Portus Julius

(alternatively spelled in the Latin ) was the first harbour specifically constructed to be a base for the Imperial Rome, Roman western Roman navy, naval fleet, the . The port was located near Baiae and protected by the Misenum peninsula at the n ...

built at Cumae

Cumae ( or or ; ) was the first ancient Greek colony of Magna Graecia on the mainland of Italy and was founded by settlers from Euboea in the 8th century BCE. It became a rich Roman city, the remains of which lie near the modern village of ...

, and soldiers and rowers levied, including over 20,000 manumitted slaves. Finally, Octavian and Agrippa defeated Sextus in the Battle of Naulochus

The naval Battle of Naulochus was fought on 3 September 36 BC between the fleets of Sextus Pompeius and Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, off Naulochus, Sicily. The victory of Agrippa, admiral of Octavian, marked the end of the Pompeian resistance to t ...

in 36 BC, putting an end to all Pompeian resistance.

Octavian's power was further enhanced after his victory against the combined fleets of

Octavian's power was further enhanced after his victory against the combined fleets of Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman people, Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the Crisis of the Roman Republic, transformation of the Roman Republic ...

and Cleopatra

Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator (; The name Cleopatra is pronounced , or sometimes in both British and American English, see and respectively. Her name was pronounced in the Greek dialect of Egypt (see Koine Greek phonology). She was ...

, Queen of Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, in the Battle of Actium

The Battle of Actium was a naval battle fought between Octavian's maritime fleet, led by Marcus Agrippa, and the combined fleets of both Mark Antony and Cleopatra. The battle took place on 2 September 31 BC in the Ionian Sea, near the former R ...

in 31 BC, where Antony had assembled 500 ships against Octavian's 400 ships. This last naval battle of the Roman Republic definitively established Octavian as the sole ruler over Rome and the Mediterranean world. In the aftermath of his victory, he formalized the Fleet's structure, establishing several key harbors in the Mediterranean (see below). The now fully professional navy had its main duties consist of protecting against piracy, escorting troops and patrolling the river frontiers of Europe. It remained however engaged in active warfare in the periphery of the Empire.

Principate

Operations under Augustus

UnderAugustus

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in A ...

and after the conquest of Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

there were increasing demands from the Roman economy to extend the trade lanes to India. The Arabian control of all sea routes to India was an obstacle. One of the first naval operations under ''princeps'' Augustus was therefore the preparation for a campaign on the Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

. Aelius Gallus

Gaius Aelius Gallus was a Roman prefect of Egypt from 26 to 24 BC. He is primarily known for a disastrous expedition he undertook to Arabia Felix (modern day Yemen) under orders of Augustus.

Life

Aelius Gallus was the 2nd '' praefect'' of Rom ...

, the prefect of Egypt ordered the construction of 130 transports and subsequently carried 10,000 soldiers to Arabia. But the following march through the desert towards Yemen

Yemen, officially the Republic of Yemen, is a country in West Asia. Located in South Arabia, southern Arabia, it borders Saudi Arabia to Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, the north, Oman to Oman–Yemen border, the northeast, the south-eastern part ...

failed and the plans for control of the Arabian Peninsula had to be abandoned.

At the other end of the Empire, in Germania

Germania ( ; ), also more specifically called Magna Germania (English: ''Great Germania''), Germania Libera (English: ''Free Germania''), or Germanic Barbaricum to distinguish it from the Roman provinces of Germania Inferior and Germania Superio ...

, the navy played an important role in the supply and transport of the legions. In 15 BC an independent fleet was installed at Lake Constance

Lake Constance (, ) refers to three bodies of water on the Rhine at the northern foot of the Alps: Upper Lake Constance (''Obersee''), Lower Lake Constance (''Untersee''), and a connecting stretch of the Rhine, called the Seerhein (). These ...

. Later, the generals Drusus

Drusus may refer to:

* Gaius Livius Drusus (jurist), son of the Roman consul of 147 BC

* Marcus Livius Drusus (consul) (155–108 BC), opponent of populist reformer Gaius Gracchus

* Marcus Livius Drusus (reformer) (died 91 BC), whose assassinatio ...

and Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus ( ; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was Roman emperor from AD 14 until 37. He succeeded his stepfather Augustus, the first Roman emperor. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC to Roman politician Tiberius Cl ...

used the Navy extensively, when they tried to extend the Roman frontier to the Elbe

The Elbe ( ; ; or ''Elv''; Upper Sorbian, Upper and , ) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Republic), then Ge ...

. In 12 BC Drusus ordered the construction of a fleet of 1,000 ships and sailed them along the Rhine

The Rhine ( ) is one of the List of rivers of Europe, major rivers in Europe. The river begins in the Swiss canton of Graubünden in the southeastern Swiss Alps. It forms part of the Swiss-Liechtenstein border, then part of the Austria–Swit ...

into the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

. The Frisii

The Frisii were an ancient tribe, who were neighbours of the Roman empire in the low-lying coastal region between the Rhine and the Ems (river), Ems rivers, in what what is now the northern Netherlands. They are not mentioned in Roman records af ...

and Chauci

The Chauci were an ancient Germanic tribe living in the low-lying region between the Rivers Ems and Elbe, on both sides of the Weser and ranging as far inland as the upper Weser. Along the coast they lived on artificial mounds called '' terpen'' ...

had nothing to oppose the superior numbers, tactics and technology of the Romans. When these entered the river mouths of Weser

The Weser () is a river of Lower Saxony in north-west Germany. It begins at Hannoversch Münden through the confluence of the Werra and Fulda. It passes through the Hanseatic city of Bremen. Its mouth is further north against the ports o ...

and Ems Ems or EMS may refer to:

Places and rivers

* Domat/Ems, a Swiss municipality in the canton of Grisons

* Ems (river) (Eems), a river in northwestern Germany and northeastern Netherlands that discharges in the Dollart Bay

* Ems (Eder), a river o ...

, the local tribes had to surrender.

In 5 BC the Roman knowledge concerning the North and Baltic Sea was fairly extended during a campaign by Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus ( ; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was Roman emperor from AD 14 until 37. He succeeded his stepfather Augustus, the first Roman emperor. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC to Roman politician Tiberius Cl ...

, reaching as far as the Elbe

The Elbe ( ; ; or ''Elv''; Upper Sorbian, Upper and , ) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Republic), then Ge ...

: Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

describes how Roman naval formations came past Heligoland

Heligoland (; , ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , ) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. The islands were historically possessions of Denmark, then became possessions of the United Kingdom from 1807 to 1890. Since 1890, the ...

and set sail to the north-eastern coast of Denmark, and Augustus himself boasts in his ''Res Gestae

''Res gestae'' (Latin: "things done") is a term found in substantive and procedural American jurisprudence and English law. In American substantive law, it refers to the period of a felony from start-to-end. In American procedural law, it refe ...

'': "My fleet sailed from the mouth of the Rhine eastward as far as the lands of the Cimbri

The Cimbri (, ; ) were an ancient tribe in Europe. Ancient authors described them variously as a Celtic, Gaulish, Germanic, or even Cimmerian people. Several ancient sources indicate that they lived in Jutland, which in some classical texts was ...

to which, up to that time, no Roman had ever penetrated either by land or by sea...". The multiple naval operations north of Germania had to be abandoned after the battle of the Teutoburg Forest

The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, also called the Varus Disaster or Varian Disaster () by Ancient Rome, Roman historians, was a major battle fought between an alliance of Germanic peoples and the Roman Empire between September 8 and 11, 9&nbs ...

in the year 9 AD.

Julio-Claudian dynasty

In the years 15 and 16,Germanicus

Germanicus Julius Caesar (24 May 15 BC – 10 October AD 19) was a Roman people, Roman general and politician most famously known for his campaigns against Arminius in Germania. The son of Nero Claudius Drusus and Antonia the Younger, Germanicu ...

carried out several fleet operations along the rivers Rhine and Ems, without permanent results due to grim Germanic resistance and a disastrous storm. By 28, the Romans lost further control of the Rhine mouth in a succession of Frisian insurgencies. From 43 to 85, the Roman navy played an important role in the Roman conquest of Britain

The Roman conquest of Britain was the Roman Empire's conquest of most of the island of Great Britain, Britain, which was inhabited by the Celtic Britons. It began in earnest in AD 43 under Emperor Claudius, and was largely completed in the ...

. The '' classis Germanica'' rendered outstanding services in multitudinous landing operations. In 46, a naval expedition made a push deep into the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

region and even travelled on the Tanais

Tanais ( ''Tánaïs''; ) was an ancient Greek city in the Don river delta, called the Maeotian marshes in classical antiquity. It was a bishopric as Tana and remains a Latin Catholic titular see as Tanais.

Location

The delta reaches into the ...

. In 47 a revolt by the Chauci

The Chauci were an ancient Germanic tribe living in the low-lying region between the Rivers Ems and Elbe, on both sides of the Weser and ranging as far inland as the upper Weser. Along the coast they lived on artificial mounds called '' terpen'' ...

, who took to piratical activities along the Gallic coast, was subdued by Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo

Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo ( Peltuinum c. AD 7 – 67) was a popular Roman general, brother-in-law of the emperor Caligula and father-in-law of Domitian. The emperor Nero, highly fearful of Corbulo's reputation, ordered him to commit suicide, which t ...

. By 57 an expeditionary corps reached Chersonesos

Chersonesus, contracted in medieval Greek to Cherson (), was an ancient Greek colony founded approximately 2,500 years ago in the southwestern part of the Crimean Peninsula. Settlers from Heraclea Pontica in Bithynia established the colon ...

(see Charax, Crimea

Charax (, gen.: Χάρακος) is the largest Roman military settlement excavated in the Crimea. It was sited on a four-hectare area at the western ridge of Ai-Todor, close to the modern tourist attraction of Swallow's Nest.

The military camp ...

).

It seems that under Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68) was a Roman emperor and the final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 until his ...

, the navy obtained strategically important positions for trading with India; but there was no known fleet in the Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

. Possibly, parts of the Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

n fleet were operating as escorts for the Indian trade. In the Jewish revolt, from 66 to 70, the Romans were forced to fight Jewish ships, operating from a harbour in the area of modern Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( or , ; ), sometimes rendered as Tel Aviv-Jaffa, and usually referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the Gush Dan metropolitan area of Israel. Located on the Israeli Mediterranean coastline and with a popula ...

, on Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

's Mediterranean coast. In the meantime several flotilla engagements on the Sea of Galilee

The Sea of Galilee (, Judeo-Aramaic languages, Judeo-Aramaic: יַמּא דטבריא, גִּנֵּיסַר, ), also called Lake Tiberias, Genezareth Lake or Kinneret, is a freshwater lake in Israel. It is the lowest freshwater lake on Earth ...

took place.

In 68, as his reign became increasingly insecure, Nero raised ''legio'' I ''Adiutrix'' from sailors of the praetorian fleets. After Nero's overthrow, in 69, the "Year of the four emperors

The Year of the Four Emperors, AD 69, was the first civil war of the Roman Empire, during which four emperors ruled in succession, Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian. It is considered an important interval, marking the change from the ...

", the praetorian fleets supported Emperor Otho

Otho ( ; born Marcus Salvius Otho; 28 April 32 – 16 April 69) was Roman emperor, ruling for three months from 15 January to 16 April 69. He was the second emperor of the Year of the Four Emperors.

A member of a noble Etruscan civilization, ...

against the usurper Vitellius

Aulus Vitellius ( ; ; 24 September 1520 December 69) was Roman emperor for eight months, from 19 April to 20 December AD 69. Vitellius became emperor following the quick succession of the previous emperors Galba and Otho, in a year of civil wa ...

, and after his eventual victory, Vespasian

Vespasian (; ; 17 November AD 9 – 23 June 79) was Roman emperor from 69 to 79. The last emperor to reign in the Year of the Four Emperors, he founded the Flavian dynasty, which ruled the Empire for 27 years. His fiscal reforms and consolida ...

formed another legion, ''legio'' II ''Adiutrix'', from their ranks. Only in Pontus

Pontus or Pontos may refer to:

* Short Latin name for the Pontus Euxinus, the Greek name for the Black Sea (aka the Euxine sea)

* Pontus (mythology), a sea god in Greek mythology

* Pontus (region), on the southern coast of the Black Sea, in modern ...

did Anicetus, the commander of the ''Classis Pontica

The Classis Pontica was a '' provincialis'' fleet, established initially by Augustus and then by Nero on a permanent basis (around 57). It was tasked with guarding the southern ''Pontus Euxinus'', coordinating with the neighboring fleet of Mesia ...

'', support Vitellius. He burned the fleet, and sought refuge with the Iberian

Iberian refers to Iberia. Most commonly Iberian refers to:

*Someone or something originating in the Iberian Peninsula, namely from Spain, Portugal, Gibraltar and Andorra.

The term ''Iberian'' is also used to refer to anything pertaining to the fo ...

tribes, engaging in piracy. After a new fleet was built, this revolt was subdued.

Flavian, Antonine and Severan dynasties

During theBatavian rebellion

The Revolt of the Batavi took place in the Roman province of Germania Inferior ("Lower Germania") between AD 69 and 70. It was an uprising against the Roman Empire started by the Batavi (Germanic tribe), Batavi, a small but militarily powerful G ...

of Gaius Julius Civilis

Gaius Julius Civilis (AD 25 – ) was the leader of the Batavian rebellion against the Romans in 69 AD. His Roman naming conventions, nomen shows that he (or one of his male ancestors) was made a Roman citizen (and thus, the tribe a Roman vassal) ...

(69–70), the rebels got hold of a squadron of the Rhine fleet by treachery, and the conflict featured frequent use of the Roman Rhine flotilla. In the last phase of the war, the British fleet and ''legio'' XIV were brought in from Britain to attack the Batavian coast, but the Cananefates

The Cananefates, or Canninefates, Caninefates, or Canenefatae, meaning 'boat masters' – or less likely, 'leek masters' – were a Germanic tribe, who lived in the Rhine delta, in western Batavia (later Betuwe), in the Roman province of ''Germ ...

, allies of the Batavians, were able to destroy or capture a large part of the fleet. In the meantime, the new Roman commander, Quintus Petillius Cerialis

Quintus Petillius Cerialis Caesius Rufus ( AD 30 — after AD 83), otherwise known as Quintus Petillius Cerialis, was a Roman general and administrator who served in Britain during Boudica's rebellion and went on to participate in the civil wars ...

, advanced north and constructed a new fleet. Civilis attempted only a short encounter with his own fleet, but could not hinder the superior Roman force from landing and ravaging the island of the Batavians, leading to the negotiation of a peace soon after.

In the years 82 to 85, the Romans under Gnaeus Julius Agricola

Gnaeus Julius Agricola (; 13 June 40 – 23 August 93) was a Roman general and politician responsible for much of the Roman conquest of Britain. Born to a political family of senatorial rank, Agricola began his military career as a military tribu ...

launched a campaign against the Caledonians

The Caledonians (; or '; , ''Kalēdōnes'') or the Caledonian Confederacy were a Brittonic-speaking (Celtic) tribal confederacy in what is now Scotland during the Iron Age and Roman eras.

The Greek form of the tribal name gave rise to the ...

in modern Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

. In this context the Roman navy significantly escalated activities on the eastern Scottish coast. Simultaneously multiple expeditions and reconnaissance trips were launched. During these the Romans would capture the Orkney Islands

Orkney (), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The plural name the Orkneys is also sometimes used, but locals now consider it outdated. Part of the Northern Isles along with Shetland ...

(''Orcades'') for a short period of time and obtained information about the Shetland Islands

Shetland (until 1975 spelled Zetland), also called the Shetland Islands, is an archipelago in Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the Uni ...

. There is some speculation about a Roman landing in Ireland, based on Tacitus reports about Agricola contemplating the island's conquest, but no conclusive evidence to support this theory has been found.

Under the Five Good Emperors