Chan (; of ), from

Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; stem form ; nominal singular , ,) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in northwest South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural ...

''

dhyāna'' (meaning "

meditation

Meditation is a practice in which an individual uses a technique to train attention and awareness and detach from reflexive, "discursive thinking", achieving a mentally clear and emotionally calm and stable state, while not judging the meditat ...

" or "meditative state"), is a Chinese school of

Mahāyāna

Mahāyāna ( ; , , ; ) is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, Buddhist texts#Mahāyāna texts, texts, Buddhist philosophy, philosophies, and practices developed in ancient India ( onwards). It is considered one of the three main ex ...

Buddhism

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

. It developed in

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

from the 6th century CE onwards, becoming especially popular during the

Tang and

Song dynasties.

Chan is the originating tradition of

Zen Buddhism

Zen (; from Chinese: '' Chán''; in Korean: ''Sŏn'', and Vietnamese: ''Thiền'') is a Mahayana Buddhist tradition that developed in China during the Tang dynasty by blending Indian Mahayana Buddhism, particularly Yogacara and Madhyamaka ph ...

(the Japanese pronunciation of the same

character, which is the most commonly used English name for the school). Chan Buddhism spread from China south to

Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

as

Thiền and north to

Korea

Korea is a peninsular region in East Asia consisting of the Korean Peninsula, Jeju Island, and smaller islands. Since the end of World War II in 1945, it has been politically Division of Korea, divided at or near the 38th parallel north, 3 ...

as

Seon, and, in the 13th century, east to

Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

as

Japanese Zen

:''See also Zen for an overview of Zen, Chan Buddhism for the Chinese origins, and Sōtō, Rinzai school, Rinzai and Ōbaku for the three main schools of Zen in Japan''

Japanese Zen refers to the Japanese forms of Zen, Zen Buddhism, an orig ...

.

History

The historical records required for a complete, accurate account of early Chan history no longer exist.

Periodisation

The history of Chan in China can be divided into several periods. Zen, as we know it today, is the result of a long history, with many changes and contingent factors. Each period had different types of Zen, some of which remained influential, while others vanished.

Andy Ferguson distinguishes three periods from the 5th century into the 13th century:

# The Legendary period, from

Bodhidharma in the late 5th century to the

An Lushan Rebellion around 765 CE, in the middle of the

Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, c=唐朝), or the Tang Empire, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907, with an Wu Zhou, interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dynasty and followed ...

. Little written information is left from this period. It is the time of the Six Patriarchs, including Bodhidharma and

Huineng, and the legendary "split" between the Northern and the Southern School of Chan.

# The Classical period, from the end of the

An Lushan Rebellion around 765 CE to the beginning of the

Song dynasty

The Song dynasty ( ) was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 960 to 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song, who usurped the throne of the Later Zhou dynasty and went on to conquer the rest of the Fiv ...

around 950 CE. This is the time of the great masters of Chan, such as

Mazu Daoyi and

Linji Yixuan

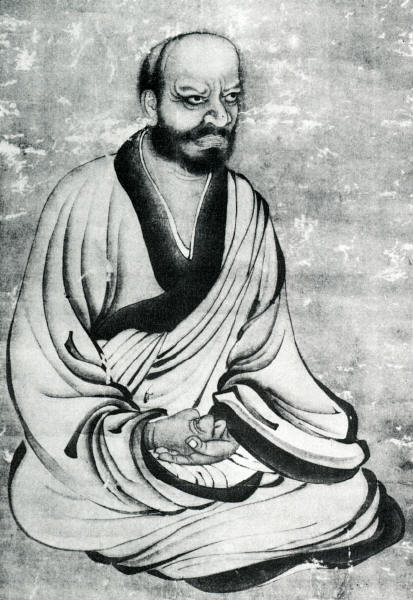

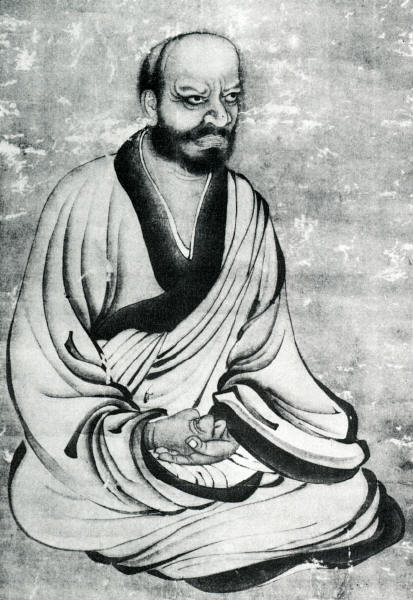

Japanese painting of Linji

Linji Yixuan (; ''Rinzai Gigen''; died 866 CE) was a Tang dynasty (618-907) Chinese monk and teacher of the Hongzhou school of Chinese Chan (Zen). Linji was the leading figure of Chan Buddhism in the Tang, and the '' ...

, and the creation of the ''yü-lü'' genre, the recordings of the sayings and teachings of these great masters.

# The Literary period, from around 950 to 1250, which spans the era of the Song dynasty (960–1279). In this time the

gong'an-collections were compiled, collections of sayings and deeds by the famous masters, appended with poetry and commentary. This genre reflects the influence of ''literati'' on the development of Chan. This period idealized the previous period as the "golden age" of Chan, producing the literature in which the spontaneity of the celebrated masters was portrayed.

Although John R. McRae has reservations about the division of Chan history in phases or periods, he nevertheless distinguishes four phases in the history of Chan:

# Proto-Chan (c. 500–600) (

Southern and Northern Dynasties (420 to 589) and

Sui dynasty

The Sui dynasty ( ) was a short-lived Dynasties of China, Chinese imperial dynasty that ruled from 581 to 618. The re-unification of China proper under the Sui brought the Northern and Southern dynasties era to a close, ending a prolonged peri ...

(589–618 CE)). In this phase, Chan developed in multiple locations in northern China. It was based on the practice of ''dhyana'' and is connected to the figures of Bodhidharma and Huike. Its principal text is the

Two Entrances and Four Practices, attributed to Bodhidharma.

#Early Chan (c. 600–900) (

Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, c=唐朝), or the Tang Empire, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907, with an Wu Zhou, interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dynasty and followed ...

(618–907 CE)). In this phase, Chan took its first clear contours. Prime figures are the fifth patriarch

Daman Hongren (601–674), his dharma-heir

Yuquan Shenxiu (606?–706), the sixth patriarch

Huineng (638–713), protagonist of the quintessential

Platform Sutra, and

Shenhui (670–762), whose propaganda elevated Huineng to the status of sixth patriarch. Prime factions are the

Northern School, Southern School and

Oxhead School.

# Middle Chan (c. 750–1000) (from

An Lushan Rebellion (755–763) until

Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907–960/979)). In this phase developed the well-known Chan of the iconoclastic zen-masters. Prime figures are

Mazu Daoyi (709–788),

Shitou Xiqian (710–790),

Linji Yixuan

Japanese painting of Linji

Linji Yixuan (; ''Rinzai Gigen''; died 866 CE) was a Tang dynasty (618-907) Chinese monk and teacher of the Hongzhou school of Chinese Chan (Zen). Linji was the leading figure of Chan Buddhism in the Tang, and the '' ...

(died 867), and

Xuefeng Yicun (822–908). Prime factions are the

Hongzhou school and the Hubei faction. An important text is the

Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall (952), which contains many "encounter-stories" and the canon genealogy of the Chan-school.

#

Song dynasty

The Song dynasty ( ) was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 960 to 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song, who usurped the throne of the Later Zhou dynasty and went on to conquer the rest of the Fiv ...

Chan (c. 950–1300). In this phase, Chan took its definitive shape including the picture of the "golden age" of the Chan of the Tang-dynasty, and the use of

koans for individual study and meditation. Prime figures are

Dahui Zonggao (1089–1163) who introduced the

Hua Tou practice and

Hongzhi Zhengjue (1091–1157) who emphasized

Silent Illumination. Prime factions are the

Linji school

The Línjì school () is a school of Chan Buddhism named after Linji Yixuan (d. 866). It took prominence in Song dynasty, Song China (960–1279), spread to Japan as the Rinzai school and influenced the nine mountain schools of Korean Seon.

Hi ...

and the

Caodong school. The classic koan-collections, such as the

Blue Cliff Record

The ''Blue Cliff Record'' () is a collection of Chan Buddhist kōans originally compiled in Song China in 1125, during the reign of Emperor Huizong, and then expanded into its present form by Chan master Yuanwu Keqin (1063–1135; ).K. Sekid ...

were assembled in this period, which reflect the influence of the "literati" on the development of Chan. In this phase Chan is transported to Japan, and exerts a great influence on Korean Seon via

Jinul.

Neither Ferguson nor McRae gives a periodisation for Chinese Chan following the Song-dynasty, though McRae mentions

:

."at least a postclassical phase or perhaps multiple phases".

Introduction of Buddhism in China (c. 200–500)

Sinification of Buddhism and Taoist influences

When Buddhism came to China, it was adapted to the Chinese culture and understanding. Theories about the influence of other schools in the evolution of Chan vary widely and are heavily reliant upon speculative

correlation

In statistics, correlation or dependence is any statistical relationship, whether causal or not, between two random variables or bivariate data. Although in the broadest sense, "correlation" may indicate any type of association, in statistics ...

rather than on written records or histories. Numerous scholars have argued that Chan developed from the interaction between

Mahāyāna

Mahāyāna ( ; , , ; ) is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, Buddhist texts#Mahāyāna texts, texts, Buddhist philosophy, philosophies, and practices developed in ancient India ( onwards). It is considered one of the three main ex ...

Buddhism and

Taoism

Taoism or Daoism (, ) is a diverse philosophical and religious tradition indigenous to China, emphasizing harmony with the Tao ( zh, p=dào, w=tao4). With a range of meaning in Chinese philosophy, translations of Tao include 'way', 'road', ' ...

.

Buddhist meditation

Buddhist meditation is the practice of meditation in Buddhism. The closest words for meditation in the classical languages of Buddhism are ''bhavana, bhāvanā'' ("mental development") and ''Dhyāna in Buddhism, jhāna/dhyāna'' (a state of me ...

was practiced in China centuries before the rise of Chan, by people such as

An Shigao (c. 148–180 CE) and his school, who translated various

Dhyāna sutras (Chán-jing, 禪經, "meditation treatises"), which were influential early meditation texts mostly based on the meditation teachings of the

Kashmiri Sarvāstivāda school (circa 1st–4th centuries CE).

[Deleanu, Florin (1992)]

Mindfulness of Breathing in the Dhyāna Sūtras

Transactions of the International Conference of Orientalists in Japan (TICOJ) 37, 42-57. The five

main types of meditation in the Dhyana sutras are

anapanasati

(Pali; Sanskrit: '), meaning " mindfulness of breathing" ( means mindfulness; refers to inhalation and exhalation), is the act of paying attention to the breath. It is the quintessential form of Buddhist meditation, attributed to Gautama Bud ...

(mindfulness of breathing);

paṭikūlamanasikāra meditation, mindfulness of the impurities of the body; loving-kindness

maitrī meditation; the contemplation on the twelve links of

pratītyasamutpāda; and the contemplation on the

Buddha's thirty-two Characteristics.

[Ven. Dr. Yuanci]

A Study of the Meditation Methods in the DESM and Other Early Chinese Texts

, The Buddhist Academy of China. Other important translators of meditation texts were

Kumārajīva (334–413 CE), who translated ''The Sutra on the Concentration of Sitting Meditation'', amongst many other texts; and

Buddhabhadra. These Chinese translations of mostly Indian Sarvāstivāda Yogacara meditation manuals were the basis for the meditation techniques of Chinese Chan.

Buddhism was exposed to

Confucian

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China, and is variously described as a tradition, philosophy, religion, theory of government, or way of life. Founded by Confucius ...

,

Taoist

Taoism or Daoism (, ) is a diverse philosophical and religious tradition indigenous to China, emphasizing harmony with the Tao ( zh, p=dào, w=tao4). With a range of meaning in Chinese philosophy, translations of Tao include 'way', 'road', ...

and local

Folk religious influences when it came to China. Goddard quotes

D.T. Suzuki, calling Chan a "natural evolution of Buddhism under Taoist conditions". Buddhism was first identified to be "a barbarian variant of Taoism", and Taoist terminology was used to express Buddhist doctrines in the oldest translations of Buddhist texts, a practice termed ''ko-i'', "matching the concepts".

The first Buddhist

converts

Conversion or convert may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''The Convert'', a 2023 film produced by Jump Film & Television and Brouhaha Entertainment

* "Conversion" (''Doctor Who'' audio), an episode of the audio drama ''Cyberman''

* ...

in China were Taoists. They developed high esteem for the newly introduced Buddhist meditational techniques, and blended them with

Taoist meditation. Representatives of early Chinese Buddhism like

Sengzhao and

Tao Sheng were deeply influenced by the Taoist keystone works of

Laozi

Laozi (), also romanized as Lao Tzu #Name, among other ways, was a semi-legendary Chinese philosophy, Chinese philosopher and author of the ''Tao Te Ching'' (''Laozi''), one of the foundational texts of Taoism alongside the ''Zhuangzi (book) ...

and

Zhuangzi. Against this background, especially the Taoist concept of ''

naturalness'' was inherited by the early Chan disciples: they equated – to some extent – the ineffable

Tao

The Tao or Dao is the natural way of the universe, primarily as conceived in East Asian philosophy and religion. This seeing of life cannot be grasped as a concept. Rather, it is seen through actual living experience of one's everyday being. T ...

and

Buddha-nature

In Buddhist philosophy and soteriology, Buddha-nature ( Chinese: , Japanese: , , Sanskrit: ) is the innate potential for all sentient beings to become a Buddha or the fact that all sentient beings already have a pure Buddha-essence within ...

, and thus, rather than feeling bound to the abstract "wisdom of the sūtras", emphasized Buddha-nature to be found in "everyday" human life, just as the Tao.

Chinese Buddhism absorbed

Neo-Daoist concepts as well. Concepts such as ''T'i-yung'' (體用 Essence and Function) and ''Li-shih'' (理事 Noumenon and Phenomenon, or Principle and Practice) first appeared in

Hua-yen Buddhism, which consequently influenced Chan deeply. On the other hand, Taoists at first misunderstood

sunyata to be akin to the Taoist

non-being.

The emerging Chinese Buddhism nevertheless had to compete with Taoism and Confucianism:

One point of confusion for this new emerging Chinese Buddhism was the

two truths doctrine

The Buddhism, Buddhist doctrine of the two truths (Sanskrit: '','' ) differentiates between two levels of ''satya'' (Sanskrit; Pāli: ''sacca''; meaning "truth" or "reality") in the teaching of Gautama Buddha, Śākyamuni Buddha: the "conventiona ...

. Chinese thinking took this to refer to two ''ontological truths'': reality exists on two levels, a relative level and an absolute level. Taoists at first misunderstood

sunyata to be akin to the Taoist non-being. In Indian

Madhyamaka

Madhyamaka ("middle way" or "centrism"; ; ; Tibetic languages, Tibetan: དབུ་མ་པ་ ; ''dbu ma pa''), otherwise known as Śūnyavāda ("the Śūnyatā, emptiness doctrine") and Niḥsvabhāvavāda ("the no Svabhava, ''svabhāva'' d ...

philosophy the two truths are two ''epistemological truths'': two different ways to look at reality. Based on their understanding of the

''Mahayana Mahaparinirvana Sutra'' the Chinese supposed that the teaching of Buddha-nature was, as stated by that sutra, the final Buddhist teaching, and that there is an essential truth above sunyata and the two truths.

Divisions of training

When Buddhism came to China, there were three divisions of training:

# The training in virtue and discipline in the precepts (Skt. ''

śīla''),

# The training in mind through meditation (Skt. ''

dhyāna'') to attain a

luminous and non-reactive state of mind, and

# The training in the recorded teachings (Skt. ''Dharma'').

It was in this context that Buddhism entered into Chinese culture. Three types of teachers with expertise in each training practice developed:

#

Vinaya

The Vinaya (Pali and Sanskrit: विनय) refers to numerous monastic rules and ethical precepts for fully ordained monks and nuns of Buddhist Sanghas (community of like-minded ''sramanas''). These sets of ethical rules and guidelines devel ...

masters specialized in all the rules of discipline for monks and nuns,

# Dhyāna masters specialized in the practice of meditation, and

#

Dharma

Dharma (; , ) is a key concept in various Indian religions. The term ''dharma'' does not have a single, clear Untranslatability, translation and conveys a multifaceted idea. Etymologically, it comes from the Sanskrit ''dhr-'', meaning ''to hold ...

masters specialized in the mastery of the Buddhist texts.

Monasteries and practice centers were created that tended to focus on either the Vinaya and training of monks or the teachings focused on one scripture or a small group of texts. Dhyāna (''Chan'') masters tended to practice in solitary hermitages, or to be associated with Vinaya training monasteries or the dharma teaching centers. The later naming of the Zen school has its origins in this view of the threefold division of training.

McRae goes so far as to say:

Legendary or Proto-Chan (c. 500–600)

Mahākāśyapa and the Flower Sermon

The Chan tradition ascribes the origins of Chan in India to the

Flower Sermon, the earliest source for which comes from the 14th century. It is said that

Gautama Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha (),*

*

*

was a śramaṇa, wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism. According to Buddhist lege ...

gathered his disciples one day for a

Dharma talk. When they gathered together, the Buddha was completely silent and some speculated that perhaps the Buddha was tired or ill. The Buddha silently held up and twirled a flower and his eyes twinkled; several of his disciples tried to interpret what this meant, though none of them were correct. One of the Buddha's disciples,

Mahākāśyapa

Mahākāśyapa () was one of The ten principal disciples, the principal disciples of Gautama Buddha. He is regarded in Buddhism as an arhat, enlightened disciple, being Śrāvaka#Foremost disciples, foremost in dhutanga, ascetic practice. Mah� ...

, gazed at the flower and smiled. The Buddha then acknowledged Mahākāśyapa's insight by saying the following:

First six patriarchs (c. 500 – early 8th century)

Traditionally the origin of Chan in China is credited to

Bodhidharma, an

Iranian-language speaking Central Asian monk or an Indian monk. The story of his life, and of the Six Patriarchs, was constructed during the

Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, c=唐朝), or the Tang Empire, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907, with an Wu Zhou, interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dynasty and followed ...

to lend credibility to the growing Chan-school. Only scarce historical information is available about him, but his hagiography developed when the Chan tradition grew stronger and gained prominence in the early 8th century. By this time a lineage of the six ancestral founders of Chan in China was developed.

The actual origins of Chan may lie in ascetic practitioners of Buddhism, who found refuge in forests and mountains.

Huike, "a dhuta (extreme ascetic) who schooled others" and used the

Srimala Sutra, one of the

Tathāgatagarbha sūtras, figures in the stories about Bodhidharma. Huike is regarded as the second Chan patriarch, appointed by Bodhidharma to succeed him. One of Huike's students,

Sengcan, to whom is ascribed the

Xinxin Ming, is regarded as the third patriarch.

By the late 8th century, under the influence of

Huineng's student

Shenhui, the traditional list of patriarchs of the Chan lineage had been established:

#

Bodhidharma () c. 440 – c. 528

#

Dazu Huike () 487–593

#

Sengcan () ?–606

#

Dayi Daoxin () 580–651

#

Daman Hongren () 601–674

#

Huineng () 638–713

In later writings, this lineage was extended to include 28 Indian patriarchs. In the ''

Song of Enlightenment'' (證道歌 ''Zhèngdào gē'') of

Yongjia Xuanjue (永嘉玄覺, 665–713), one of the chief disciples of

Huìnéng, it is written that Bodhidharma was the 28th patriarch in a line of descent from Mahākāśyapa, a disciple of

Śākyamuni Buddha, and the first patriarch of Chan Buddhism.

Lankavatara Sutra

In its beginnings in China, Chan primarily referred to the

Mahāyāna sūtras

The Mahayana sutras are Buddhist texts that are accepted as wikt:canon, canonical and authentic Buddhist texts, ''buddhavacana'' in Mahayana, Mahayana Buddhist sanghas. These include three types of sutras: Those spoken by the Buddha; those spoke ...

and especially to the ''

Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra

The ''Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra'' (Sanskrit: लङ्कावतारसूत्रम्, "Discourse of the Descent into Laṅkā", , Chinese: 入楞伽經) is a prominent Mahayana Buddhist sūtra. It is also titled ''Laṅkāvatāraratnasūt ...

''. As a result, early masters of the Chan tradition were referred to as "Laṅkāvatāra masters". As the ''Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra'' teaches the doctrine of the

Ekayāna "One Vehicle", the early Chan school was sometimes referred to as the "One Vehicle School". In other early texts, the school that would later become known as Chan is sometimes even referred to as simply the "Laṅkāvatāra school" (Ch. 楞伽宗, ''Léngqié Zōng''). Accounts recording the history of this early period are to be found in the ''

Records of the Laṅkāvatāra Masters'' ('').

Bodhidharma

Bodhidharma is recorded as having come into China during the time of

Southern and Northern Dynasties to teach a "special transmission outside scriptures" which "did not stand upon words". Throughout

Buddhist art

Buddhist art is visual art produced in the context of Buddhism. It includes Buddha in art, depictions of Gautama Buddha and other Buddhas and bodhisattvas in art, Buddhas and bodhisattvas, notable Buddhist figures both historical and mythical, ...

, Bodhidharma is depicted as a rather ill-tempered, profusely bearded and wide-eyed barbarian. He is referred to as "The Blue-Eyed

Barbarian

A barbarian is a person or tribe of people that is perceived to be primitive, savage and warlike. Many cultures have referred to other cultures as barbarians, sometimes out of misunderstanding and sometimes out of prejudice.

A "barbarian" may ...

" ( zh, c=碧眼胡, p=Bìyǎn hú, labels=no) in Chinese Chan texts.

[Soothill, William Edward; Hodous, Lewis (1995), A Dictionary of Chinese Buddhist Terms](_blank)

London: RoutledgeCurzon Only scarce historical information is available about him but his hagiography developed when the Chan tradition grew stronger and gained prominence in the early 8th century. By this time a lineage of the six ancestral founders of Chan in China was developed.

Little contemporary biographical information on Bodhidharma is extant, and subsequent accounts became layered with legend.

There are three principal sources for Bodhidharma's biography: ''The Record of the Buddhist Monasteries of Luoyang'' by Yáng Xuànzhī's (楊衒之, 547), Tan Lin's preface to the ''

Long Scroll of the Treatise on the Two Entrances and Four Practices'' (6th century CE), and

Dayi Daoxin's ''Further Biographies of Eminent Monks'' (7th century CE).

These sources vary in their account of Bodhidharma being either "from Persia" (547 CE), "a Brahman monk from South India" (645 CE), "the third son of a Brahman king of South India" (c. 715 CE).

Some traditions specifically describe Bodhidharma to be the third son of a

Pallava king from

Kanchipuram

Kanchipuram (International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration, IAST: '; ), also known as Kanjeevaram, is a stand alone city corporation, satellite nodal city of Chennai in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu in the Tondaimandalam region, from ...

.

The ''Long Scroll of the Treatise on the Two Entrances and Four Practices'' written by Tan Lin (曇林; 506–574), contains teachings that are attributed to Bodhidharma. The text is known from the

Dunhuang manuscripts

The Dunhuang manuscripts are a wide variety of religious and secular documents (mostly manuscripts, including Hemp paper, hemp, silk, paper and Woodblock printing, woodblock-printed texts) in Old Tibetan, Tibetan, Chinese, and other languages tha ...

. The two entrances to

enlightenment are the entrance of principle and the entrance of practice:

This text was used and studied by Huike and his students. The True Nature refers to the

Buddha-nature

In Buddhist philosophy and soteriology, Buddha-nature ( Chinese: , Japanese: , , Sanskrit: ) is the innate potential for all sentient beings to become a Buddha or the fact that all sentient beings already have a pure Buddha-essence within ...

.

Huike

Bodhidharma settled in

Northern Wei

Wei (), known in historiography as the Northern Wei ( zh, c=北魏, p=Běi Wèi), Tuoba Wei ( zh, c=拓跋魏, p=Tuòbá Wèi), Yuan Wei ( zh, c=元魏, p=Yuán Wèi) and Later Wei ( zh, t=後魏, p=Hòu Wèi), was an Dynasties of China, impe ...

China. Shortly before his death, Bodhidharma appointed his disciple Dazu Huike to succeed him, making Huike the first Chinese-born ancestral founder and the second ancestral founder of Chan in China. Bodhidharma is said to have passed three items to Huike as a sign of transmission of the Dharma: a robe, a bowl, and a copy of the ''Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra''. The transmission then passed to the second ancestral founder Dazu Huike, the third Sengcan, the fourth ancestral founder Dayi Daoxin, and the fifth ancestral founder

Daman Hongren.

Early Chan in Tang China (c. 600–900)

East Mountain Teachings

With the fourth patriarch,

Daoxin ( 580–651), Chan began to take shape as a distinct school. The link between Huike and Sengcan, and the fourth patriarch Daoxin "is far from clear and remains tenuous". With Daoxin and his successor, the fifth patriarch

Hongren ( 601–674), there emerged a new style of teaching, which was inspired by the Chinese text

Awakening of Faith in the Mahayana. According to McRae, the "first explicit statement of the sudden and direct approach that was to become the hallmark of Ch'an religious practice" is associated with the

East Mountain School. It is a method named "Maintaining the one without wavering" (''shou-i pu i,'' 守一不移), ''the one'' being the

nature of mind, which is equated with Buddha-nature. In this practice, one turns the attention from the objects of experience, to the perceiving subject itself. According to McRae, this type of meditation resembles the methods of "virtually all schools of Mahayana Buddhism," but differs in that "no preparatory requirements, no moral prerequisites or preliminary exercises are given," and is "without steps or gradations. One concentrates, understands, and is enlightened, all in one undifferentiated practice." Sharf notes that the notion of "Mind" came to be criticised by radical subitists, and was replaced by "No Mind," to avoid any reifications.

A large group of students gathered at a permanent residence, and extreme asceticism became outdated. The period of Daoxin and Hongren came to be called the

East Mountain Teaching, due to the location of the residence of Hongren at Huangmei. The term was used by

Yuquan Shenxiu (神秀 606?–706), the most important successor to Hongren. By this time the group had grown into a matured congregation that became significant enough to be reckoned with by the ruling forces. The East Mountain community was a specialized meditation training centre. Hongren was a plain meditation teacher, who taught students of "various religious interests", including "practitioners of the Lotus Sutra, students of Madhyamaka philosophy, or specialists in the monastic regulations of Buddhist

Vinaya

The Vinaya (Pali and Sanskrit: विनय) refers to numerous monastic rules and ethical precepts for fully ordained monks and nuns of Buddhist Sanghas (community of like-minded ''sramanas''). These sets of ethical rules and guidelines devel ...

".

The school was typified by a "loose practice," aiming to make meditation accessible to a larger audience. Shenxiu used short formulas extracted from various sutras to package the teachings, a style which is also used in the Platform Sutra. The establishment of a community in one location was a change from the wandering lives of Bodhidharma and Huike and their followers.

It fitted better into the Chinese society, which highly valued community-oriented behaviour, instead of solitary practice.

In 701

Shenxiu was invited to the Imperial Court by Zhou Empress

Wu Zetian

Wu Zetian (624 – 16 December 705), personal name Wu Zhao, was List of rulers of China#Tang dynasty, Empress of China from 660 to 705, ruling first through others and later in her own right. She ruled as queen consort , empress consort th ...

, who paid him due to imperial reverence. The first lineage documents were produced in this period:

The transition from the East Mountain to the two capitals changed the character of Chan:

Members of the "East Mountain Teaching" shifted the alleged scriptural basis, realizing that the ''Awakening of Faith'' is not a sutra but a ''

sastra'', commentary, and fabricated a lineage of

Lankavatara Sutra masters, as being the sutra that preluded the ''Awakening of Faith''.

Southern School – Huineng and Shenhui

According to tradition, the sixth and last ancestral founder,

Huineng (惠能; 638–713), was one of the giants of Chan history, and all surviving schools regard him as their ancestor. The dramatic story of Huineng's life tells that there was a controversy over his claim to the title of patriarch. After being chosen by Hongren, the fifth ancestral founder, Huineng had to flee by night to

Nanhua Temple in the south to avoid the wrath of Hongren's jealous senior disciples.

Modern scholarship, however, has questioned this narrative. Historic research reveals that this story was created around the middle of the 8th century, as part of a campaign to win influence at the Imperial Court in 731 by a successor to Huineng called Shenhui. He claimed Huineng to be the successor of Hongren instead of Shenxiu, the recognized successor.

A dramatic story of Huineng's life was created, as narrated in the

Platform Sutra, which tells that there was a contest for the transmission of the title of patriarch. After being chosen by

Hongren, the fifth patriarch, Huineng had to flee by night to

Nanhua Temple in the south to avoid the wrath of Hongren's jealous senior disciples. Shenhui succeeded in his campaign, and Huineng eventually came to be regarded as the Sixth Patriarch. In 745 Shenhui was invited to take up residence in the Heze Temple in the capital, Dongdu (modern

Luoyang

Luoyang ( zh, s=洛阳, t=洛陽, p=Luòyáng) is a city located in the confluence area of the Luo River and the Yellow River in the west of Henan province, China. Governed as a prefecture-level city, it borders the provincial capital of Zheng ...

) In 753, he fell out of grace and had to leave Dongdu to go into exile.

The most prominent of the successors of Shenhui's lineage was

Guifeng Zongmi. According to Zongmi, Shenhui's approach was officially sanctioned in 796, when "an imperial commission determined that the Southern line of Ch'an represented the orthodox transmission and established Shen-hui as the seventh patriarch, placing an inscription to that effect in the Shen-lung temple".

Doctrinally, Shenhui's "Southern School" is associated with the teaching that

enlightenment is sudden while the "Northern" or East Mountain school is associated with the teaching that enlightenment is gradual. This was a polemical exaggeration since both schools were derived from the same tradition, and the so-called Southern School incorporated many teachings of the more influential Northern School.

Eventually both schools died out, but the influence of Shenhui was so immense that all later Chan schools traced their origin to Huineng, and "sudden enlightenment" became a standard doctrine of Chan.

Shenhui's influence is traceable in the ''

Platform Sutra'', which gives a popular account of the story of Huineng but also reconciles the antagonism created by Shenhui. Salient is that Shenhui himself does not figure in the ''Platform Sutra''; he was effectively written out of Chan history. The ''Platform Sutra'' also reflects the growing popularity of the ''

Diamond Sūtra'' (''Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra'') in 8th-century Chinese Buddhism. Thereafter, the essential texts of the Chan school were often considered to be both the ''Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra'' and the ''Diamond Sūtra''. The ''Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra'', which endorses the Buddha-nature, emphasized purity of mind, which can be attained in gradations. The Diamond-sutra emphasizes sunyata, which "must be realized totally or not at all".

David Kalupahana associates the later

Caodong school (Japanese

Sōtō, gradual) and

Linji school

The Línjì school () is a school of Chan Buddhism named after Linji Yixuan (d. 866). It took prominence in Song dynasty, Song China (960–1279), spread to Japan as the Rinzai school and influenced the nine mountain schools of Korean Seon.

Hi ...

(Japanese

Rinzai school

The Rinzai school (, zh, t=臨濟宗, s=临济宗, p=Línjì zōng), named after Linji Yixuan (Romaji: Rinzai Gigen, died 866 CE) is one of three sects of Zen in Japanese Buddhism, along with Sōtō and Ōbaku. The Chinese Linji school, Linji s ...

, sudden) schools with the

Yogacara

Yogachara (, IAST: ') is an influential tradition of Buddhist philosophy and psychology emphasizing the study of cognition, perception, and consciousness through the interior lens of meditation, as well as philosophical reasoning (hetuvidyā). ...

and

Madhyamaka

Madhyamaka ("middle way" or "centrism"; ; ; Tibetic languages, Tibetan: དབུ་མ་པ་ ; ''dbu ma pa''), otherwise known as Śūnyavāda ("the Śūnyatā, emptiness doctrine") and Niḥsvabhāvavāda ("the no Svabhava, ''svabhāva'' d ...

philosophies respectively. The same comparison has been made by McRae. The Madhyamaka school elaborated on the theme of

śūnyatā

''Śūnyatā'' ( ; ; ), translated most often as "emptiness", " vacuity", and sometimes "voidness", or "nothingness" is an Indian philosophical concept. In Buddhism, Jainism, Hinduism, and other Indian philosophical traditions, the concept ...

, which was set forth in the

prajnaparamita

file:Medicine Buddha painted mandala with goddess Prajnaparamita in center, 19th century, Rubin.jpg, A Tibetan painting with a Prajñāpāramitā sūtra at the center of the mandala

Prajñāpāramitā means "the Perfection of Wisdom" or "Trans ...

sutras, to which the ''Diamond Sutra'' also belongs. The shift from the ''Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra'' to the ''Diamond Sutra'' also signifies a tension between Buddha-nature teachings, which imply a transcendental reality, versus śūnyatā, which denies such a transcendental reality.

Tibetan Chan

Chinese Chan Buddhist teachers such as

Moheyan first went to Tibet in the eighth century during the height of the

Tibetan Empire

The Tibetan Empire (,) was an empire centered on the Tibetan Plateau, formed as a result of expansion under the Yarlung dynasty heralded by its 33rd king, Songtsen Gampo, in the 7th century. It expanded further under the 38th king, Trisong De ...

. There seems to have been disputes between them and Indian Buddhists, as exemplified by the

Samye debate. Many Tibetan Chan texts have been recovered from the caves at

Dunhuang

Dunhuang () is a county-level city in northwestern Gansu Province, Western China. According to the 2010 Chinese census, the city has a population of 186,027, though 2019 estimates put the city's population at about 191,800. Sachu (Dunhuang) was ...

, where Chan and Tantric Buddhists lived side by side and this led to

religious syncretism

Religious syncretism is the blending of religious belief systems into a new system, or the incorporation of other beliefs into an existing religious tradition.

This can occur for many reasons, where religious traditions exist in proximity to each ...

in some cases.

[Sam van Schaik, Where Chan and Tantra Meet: Buddhist Syncretism in Dunhuang] Chan Buddhism survived in Tibet for several centuries, but had mostly been replaced by the 10th century developments in

Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism is a form of Buddhism practiced in Tibet, Bhutan and Mongolia. It also has a sizable number of adherents in the areas surrounding the Himalayas, including the Indian regions of Ladakh, Gorkhaland Territorial Administration, D ...

. According to Sam Van Schaik:

After the 'dark period', all visible influences of Chan were eliminated from Tibetan Buddhism, and Mahayoga and Chan were carefully distinguished from each other. This trend

can already be observed in the tenth-century Lamp for the Eyes in Contemplation by the great central Tibetan scholar Gnubs chen Sangs rgyas ye shes. This influential work represented a crucial step in the codification of Chan, Mahayoga and the Great Perfection as distinct vehicles to enlightenment. In comparison, our group of unhuangmanuscripts exhibits remarkable freedom, blurring the lines between meditation systems that were elsewhere kept quite distinct. The system of practice set out in these manuscripts did not survive into the later Tibetan tradition. Indeed, this creative integration of meditation practices derived from both Indic and Chinese traditions could only have been possible during the earliest years of Tibetan Buddhism, when doctrinal categories were still forming, and in this sense, it represents an important stage in the Tibetan assimilation of Buddhism.

Classical or Middle Chan – Tang dynasty (c. 750–1000)

Daoxin, Hongren, Shenxiu, Huineng and Shenhui all lived during the early Tang. The later period of the

Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, c=唐朝), or the Tang Empire, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907, with an Wu Zhou, interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dynasty and followed ...

is traditionally regarded as the "golden age" of Chan. This proliferation is described in a famous saying:

An Lu-shan rebellion

The

An Lushan Rebellion (755–763) led to a loss of control by the Tang dynasty, and changed the Chan scene again. Metropolitan Chan began to lose its status, while "other schools were arising in outlying areas controlled by warlords. These are the forerunners of the Chan we know today. Their origins are obscure; the power of Shen-hui's preaching is shown by the fact that they all trace themselves to Hui-neng."

Hung-chou School

The most important of these schools is the

Hongzhou school (洪州宗) of

Mazu

Mazu or Matsu is a sea goddess in Chinese folk religion, Chinese Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism. She is also known by several other names and titles. Mazu is the deified form of Lin Moniang (), a shamaness from Fujian who is said to ...

, to which also belong

Dazhu Huihai,

Baizhang Huaihai,

Huangbo and

Linji (Rinzai). Linji is also regarded as the founder of one of the Five Houses.

This school developed "shock techniques such as shouting, beating, and using irrational retorts to startle their students into realization". Some of these are common today, while others are found mostly in anecdotes. It is common in many Chan traditions today for Chan teachers to have a stick with them during formal ceremonies which is a symbol of authority and which can be also used to strike on the table during a talk.

These shock techniques became part of the traditional and still popular image of Chan masters displaying irrational and strange behaviour to aid their students.

Part of this image was due to later misinterpretations and translation errors, such as the loud belly shout known as ''katsu''. "Katsu" means "to shout", which has traditionally been translated as "yelled 'katsu'" – which should mean "yelled a yell".

[Se]

James D. Sellmann & Hans Julius Schneider (2003), ''Liberating Language in Linji and Wittgenstein''. Asian Philosophy, Vol. 13, Nos. 2/3, 2003. Notes 26 and 41

/ref>

A well-known story depicts Mazu practicing dhyana, but being rebuked by his teacher Nanyue Huairang, comparing seated meditation with polishing a tile. According to Faure, the criticism is not about dhyana as such, but "the idea of "becoming a Buddha" by means of any practice, lowered to the standing of a "means" to achieve an "end"". The criticism of seated dhyana reflects a change in the role and position of monks in Tang society, who "undertook only pious works, reciting sacred texts and remaining seated in ''dhyana''". Nevertheless, seated dhyana remained an important part of the Chan tradition, also due to the influence of Guifeng Zongmi, who tried to balance dhyana and insight.

The Hung-chou school has been criticised for its radical subitism. Guifeng Zongmi (圭峰 宗密) (780–841), an influential teacher-scholar and patriarch of both the Chan and the Huayan school

The Huayan school of Buddhism (, Wade–Giles: ''Hua-Yen,'' "Flower Garland," from the Sanskrit "''Avataṃsaka''") is a Mahayana, Mahayana Buddhist tradition that developed in China during the Tang dynasty, Tang dynasty (618-907).Yü, Chün-fan ...

, claimed that the Hongzhou school teaching led to a radical nondualism that denies the need for spiritual cultivation and moral discipline. While Zongmi acknowledged that the essence of Buddha-nature and its functioning in the day-to-day reality are but different aspects of the same reality, he insisted that there is a difference.

Shitou Xiqian

Traditionally Shítóu Xīqiān (Ch. 石頭希遷, c. 700 – c.790) is seen as the other great figure of this period. In the Chan lineages he is regarded as the predecessor of the Caodong ( Sōtō) school. He is also regarded as the author of the Sandokai, a poem which formed the basis for the Song of the Precious Mirror Samadhi of Dongshan Liangjie (Jp. Tōzan Ryōkan) and the teaching of the Five Ranks.

The Great Persecution

During 845–846 Emperor Wuzong persecuted the Buddhist schools in China:

This persecution was devastating for metropolitan Chan, but the Chan school of Ma-tsu and his likes had survived, and took a leading role in the Chan of the later Tang.

Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period (907–960/979)

After the fall of the Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, c=唐朝), or the Tang Empire, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907, with an Wu Zhou, interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dynasty and followed ...

, China was without effective central control during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period. China was divided into several autonomous regions. Support for Buddhism was limited to a few areas. The Hua-yen and T'ient-tai schools suffered from the changing circumstances, since they had depended on imperial support. The collapse of T'ang society also deprived the aristocratic classes of wealth and influence, which meant a further drawback for Buddhism. Shenxiu's Northern School and Henshui's Southern School didn't survive the changing circumstances. Nevertheless, Chan emerged as the dominant stream within Chinese Buddhism, but with various schools developing various emphasises in their teachings, due to the regional orientation of the period. The Fayan school, named after Fa-yen Wen-i (885–958) became the dominant school in the southern kingdoms of Nan-T'ang (Jiangxi

; Gan: )

, translit_lang1_type2 =

, translit_lang1_info2 =

, translit_lang1_type3 =

, translit_lang1_info3 =

, image_map = Jiangxi in China (+all claims hatched).svg

, mapsize = 275px

, map_caption = Location ...

, Chiang-hsi) and Wuyue (Che-chiang).

Literary Chan – Song dynasty (c. 960–1300)

The Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period was followed by the Song dynasty, which established a strong central government. During the Song dynasty, Chan (禪) was used by the government to strengthen its control over the country, and Chan grew to become the largest sect in Chinese Buddhism

Chinese Buddhism or Han Buddhism ( zh, s=汉传佛教, t=漢傳佛教, first=t, poj=Hàn-thoân Hu̍t-kàu, j=Hon3 Cyun4 Fat6 Gaau3, p=Hànchuán Fójiào) is a Chinese form of Mahayana Buddhism. The Chinese Buddhist canonJiang Wu, "The Chin ...

. An ideal picture of the Chan of the Tang period was produced, which served the legacy of this newly acquired status:

Five Houses of Chan

During the Song the ''Five Houses (Ch. 五家) of Chan'', or five "schools", were recognized. These were not originally regarded as "schools" or "sects", but based on the various Chan-genealogies. Historically they have come to be understood as "schools".

The Five Houses of Chan are:Linji school

The Línjì school () is a school of Chan Buddhism named after Linji Yixuan (d. 866). It took prominence in Song dynasty, Song China (960–1279), spread to Japan as the Rinzai school and influenced the nine mountain schools of Korean Seon.

Hi ...

(臨濟宗), named after master Linji Yixuan

Japanese painting of Linji

Linji Yixuan (; ''Rinzai Gigen''; died 866 CE) was a Tang dynasty (618-907) Chinese monk and teacher of the Hongzhou school of Chinese Chan (Zen). Linji was the leading figure of Chan Buddhism in the Tang, and the '' ...

(died 866), whose lineage came to be traced to Mazu, establishing him as the archetypal iconoclastic Chan-master;

* Caodong school (曹洞宗), named after masters Dongshan Liangjie (807–869) and Caoshan Benji (840–901);

* Yunmen school (雲門宗), named after master Yunmen Wenyan (died 949), a student of Xuefeng Yicun (822–908), whose lineage was traced to Shitou Xiqian:

* Fayan school (法眼宗), named after master Fayan Wenyi (885–958), a "grand-student" of Xuefeng Yicun.

Rise of the Linji-school

The Linji-school became the dominant school within Chan, due to support from the literati and the court. Before the Song dynasty, the Linji-school is rather obscure, and very little is known about its early history. The first mention of Linji is in the ''Zutang ji'', compiled in 952, 86 years after Linji's death. But the ''Zutang ji'' pictures the Xuefeng Yicun lineage as heir to the legacy of Mazu and the Hongzhou-school.

According to Welter, the real founder of the Linji-school was Shoushan (or Baoying) Shengnian (首山省念) (926–993), a fourth generation dharma-heir of Linji. The ''Tiansheng Guangdeng lu'' (天聖廣燈錄), "Tiansheng Era Expanded Lamp Record", compiled by the official Li Zunxu (李遵勗) (988–1038) confirms the status of Shoushan Shengnian, but also pictures Linji as a major Chan patriarch and heir to the Mazu, displacing the prominence of the Fayan-lineage. It also established the slogan of "a special transmission outside the teaching", supporting the Linji-school claim of "Chan as separate from and superior to all other Buddhist teachings".

Dahui Zonggao

Over the course of Song dynasty (960–1279), the Guiyang, Fayan, and Yunmen schools were gradually absorbed into the Linji. Song Chan was dominated by the Linji school of Dahui Zonggao, which in turn became strongly affiliated to the Imperial Court:

The Wu-shan system was a system of state-controlled temples, which were established by the Song government in all provinces.

Koan-system

The teaching styles and words of the classical masters were recorded in the so-called "encounter dialogues".Blue Cliff Record

The ''Blue Cliff Record'' () is a collection of Chan Buddhist kōans originally compiled in Song China in 1125, during the reign of Emperor Huizong, and then expanded into its present form by Chan master Yuanwu Keqin (1063–1135; ).K. Sekid ...

'' (1125) of Yuanwu, '' The Gateless Gate'' (1228) of Wumen, both of the Linji lineage, and the '' Book of Equanimity'' (1223) by Wansong Xingxiu of the Caodong lineage.

These texts became classic gōng'àn cases, together with verse and prose commentaries, which crystallized into the systematized gōng'àn (koan) practice. According to Miura and Sasaki, " was during the lifetime of Yüan-wu's successor, Dahui Zonggao (大慧宗杲; 1089–1163) that Koan Chan entered its determinative stage."

Silent illumination

The Caodong was the other school to survive into the Song period. Its main protagonist was Hung-chih Cheng-chueh, a contemporary of Dahui Zonggao. It put emphasis on "silent illumination", or "just sitting". This approach was attacked by Dahui as being mere passivity, and lacking emphasis on gaining insight into one's true nature. Cheng-chueh in his turn criticized the emphasis on koan study.

Post-classical Chan (c. 1300–present)

Yuan dynasty (1279–1368)

The Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty ( ; zh, c=元朝, p=Yuáncháo), officially the Great Yuan (; Mongolian language, Mongolian: , , literally 'Great Yuan State'), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after Div ...

was the empire established by Kublai Khan

Kublai Khan (23 September 1215 – 18 February 1294), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder and first emperor of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty of China. He proclaimed the ...

, the leader of the Borjigin

A Borjigin is a member of the Mongol sub-clan that started with Bodonchar Munkhag of the Kiyat clan. Yesugei's descendants were thus said to be Kiyat-Borjigin. The senior Borjigids provided ruling princes for Mongolia and Inner Mongolia u ...

clan, after the Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire was the List of largest empires, largest contiguous empire in human history, history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Euro ...

conquered the Jin dynasty (1115–1234)

The Jin dynasty (, ), officially known as the Great Jin (), was a Jurchen people, Jurchen-led Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China and empire ruled by the Wanyan clan that existed between 1115 and 1234. It is also often called the ...

and the Southern Song dynasty

The Song dynasty ( ) was an imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 960 to 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song, who usurped the throne of the Later Zhou dynasty and went on to conquer the rest of the Ten Kingdoms, endin ...

. Chan began to be mixed with Pure Land Buddhism

Pure Land Buddhism or the Pure Land School ( zh, c=淨土宗, p=Jìngtǔzōng) is a broad branch of Mahayana, Mahayana Buddhism focused on achieving rebirth in a Pure land, Pure Land. It is one of the most widely practiced traditions of East Asi ...

as in the teachings of Zhongfeng Mingben (1263–1323). During this period, other Chan lineages, not necessarily connected with the original lineage, began to emerge with the 108th Chan Patriarch, Dhyānabhadra active in both China and Korea.

Ming dynasty (1368–1644)

Chan Buddhism enjoyed something of a revival in the Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty, officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 1368 to 1644, following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming was the last imperial dynasty of ...

, with teachers such as Hanshan Deqing (憨山德清), who wrote and taught extensively on both Chan and Pure Land Buddhism; Miyun Yuanwu (密雲圓悟), who came to be seen posthumously as the first patriarch of the Ōbaku school of Zen

Zen (; from Chinese: ''Chán''; in Korean: ''Sŏn'', and Vietnamese: ''Thiền'') is a Mahayana Buddhist tradition that developed in China during the Tang dynasty by blending Indian Mahayana Buddhism, particularly Yogacara and Madhyamaka phil ...

; and as Yunqi Zhuhong (雲棲祩宏) and Ouyi Zhixu (蕅益智旭).

Chan was taught alongside other Buddhist traditions such as Pure Land

Pure Land is a Mahayana, Mahayana Buddhist concept referring to a transcendent realm emanated by a buddhahood, buddha or bodhisattva which has been purified by their activity and Other power, sustaining power. Pure lands are said to be places ...

, Huayan, Tiantai and Chinese Esoteric Buddhism in many monasteries. In continuity with Buddhism in the previous dynasties, Buddhist masters taught integrated teachings from the various traditions as opposed to advocating for any sectarian delineation between the various schools of thought.

With the downfall of the Ming, several Chan masters fled to Japan, founding the Ōbaku school.

Qing dynasty (1644–1912)

At the beginning of the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing, was a Manchu-led Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China and an early modern empire in East Asia. The last imperial dynasty in Chinese history, the Qing dynasty was preceded by the ...

, Chan was "reinvented", by the "revival of beating and shouting practices" by Miyun Yuanwu (1566–1642), and the publication of the ''Wudeng yantong'' ("The strict transmission of the five Chan schools") by Feiyin Tongrong's (1593–1662), a dharma heir of Miyun Yuanwu. The book placed self-proclaimed Chan monks without proper Dharma transmission in the category of "lineage unknown" (''sifa weixiang''), thereby excluding several prominent Caodong monks.

Modernisation

19th century (late Qing dynasty)

Around 1900, Buddhists from other Asian countries showed a growing interest in Chinese Buddhism. Anagarika Dharmapala visited Shanghai in 1893,

Republic of China (1912–1949) – First Buddhist Revival

The modernisation of China led to the end of the Chinese Empire, and the installation of the Republic of China, which lasted on the mainland until the Communist Revolution and the installation of the People's Republic of China in 1949.

After further centuries of decline during the Qing, Chan was revived again in the early 20th century by Hsu Yun (虛雲), a well-known figure of 20th-century Chinese Buddhism. Many Chan teachers today trace their lineage to Hsu Yun, including Sheng Yen (聖嚴) and Hsuan Hua (宣化), who have propagated Chan in the West where it has grown steadily through the 20th and 21st century.

The Buddhist reformist Taixu propagated a Chan-influenced humanistic Buddhism, which is endorsed by Jing Hui, former abbot of Bailin Monastery.

Until 1949, monasteries were built in the Southeast Asian countries, for example by monks of Guanghua Monastery, to spread Chinese Buddhism. Presently, Guanghua Monastery has seven branches in the Malay Peninsula and Indonesia.

The modernisation of China led to the end of the Chinese Empire, and the installation of the Republic of China, which lasted on the mainland until the Communist Revolution and the installation of the People's Republic of China in 1949.

After further centuries of decline during the Qing, Chan was revived again in the early 20th century by Hsu Yun (虛雲), a well-known figure of 20th-century Chinese Buddhism. Many Chan teachers today trace their lineage to Hsu Yun, including Sheng Yen (聖嚴) and Hsuan Hua (宣化), who have propagated Chan in the West where it has grown steadily through the 20th and 21st century.

The Buddhist reformist Taixu propagated a Chan-influenced humanistic Buddhism, which is endorsed by Jing Hui, former abbot of Bailin Monastery.

Until 1949, monasteries were built in the Southeast Asian countries, for example by monks of Guanghua Monastery, to spread Chinese Buddhism. Presently, Guanghua Monastery has seven branches in the Malay Peninsula and Indonesia.

People's Republic of China (1949–present) – Second Buddhist Revival

Chan was repressed in China during the recent modern era in the early periods of the People's Republic, but subsequently has been re-asserting itself on the mainland, and has a significant following in Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

and Hong Kong

Hong Kong)., Legally Hong Kong, China in international treaties and organizations. is a special administrative region of China. With 7.5 million residents in a territory, Hong Kong is the fourth most densely populated region in the wor ...

as well as among Overseas Chinese

Overseas Chinese people are Chinese people, people of Chinese origin who reside outside Greater China (mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan). As of 2011, there were over 40.3 million overseas Chinese. As of 2023, there were 10.5 milli ...

.

Since the Chinese economic reform

Reform and opening-up ( zh, s=改革开放, p=Gǎigé kāifàng), also known as the Chinese economic reform or Chinese economic miracle, refers to a variety of economic reforms termed socialism with Chinese characteristics and socialist marke ...

of the 1970s, a new revival of Chinese Buddhism has been ongoing.

Taiwan

Several Chinese Buddhist teachers left China during the Communist Revolution, and settled in Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Sheng Yen (1930–2009) was the founder of the Dharma Drum Mountain, a Buddhist organization based in Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

. During his time in Taiwan, Sheng Yen was well known as one of the progressive Buddhist teachers who sought to teach Buddhism in a modern and Western-influenced world. Sheng yen published over 30 Chan texts in English.

Wei Chueh (1928–2016) was born in Sichuan

Sichuan is a province in Southwestern China, occupying the Sichuan Basin and Tibetan Plateau—between the Jinsha River to the west, the Daba Mountains to the north, and the Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau to the south. Its capital city is Cheng ...

, China, and ordained in Taiwan. In 1982, he founded Lin Quan Temple in Taipei County and became known for his teaching on Ch'an

Chan (; of ), from Sanskrit '' dhyāna'' (meaning "meditation" or "meditative state"), is a Chinese school of Mahāyāna Buddhism. It developed in China from the 6th century CE onwards, becoming especially popular during the Tang and Song d ...

practices by offering many lectures and seven-day Ch'an retreats. His order is called Chung Tai Shan.

Two additional traditions emerged in the 1960s, based their teaching on Ch'an

Chan (; of ), from Sanskrit '' dhyāna'' (meaning "meditation" or "meditative state"), is a Chinese school of Mahāyāna Buddhism. It developed in China from the 6th century CE onwards, becoming especially popular during the Tang and Song d ...

practices.

Cheng Yen (born 1937), a Buddhist nun

A nun is a woman who vows to dedicate her life to religious service and contemplation, typically living under vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience in the enclosure of a monastery or convent.''The Oxford English Dictionary'', vol. X, page 5 ...

, founded the Tzu Chi Foundation as a charity organization with Buddhist

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

ethics on May 14, 1966 in Hualien, Taiwan.new religious movement

A new religious movement (NRM), also known as a new religion, is a religious or Spirituality, spiritual group that has modern origins and is peripheral to its society's dominant religious culture. NRMs can be novel in origin, or they can be part ...

based in Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

in 1967. The order promotes Humanistic Buddhism. Fo Guang Shan also calls itself the International Buddhist Progress Society. The headquarters of Fo Guang Shan, located in Dashu District

Dashu District () is a suburban district located in Kaohsiung City, Taiwan near the Kaoping River. Fo Guang Shan is one of largest tourist attractions in Dashu District. It is also the base of E-Da World, a new lifestyle destination that encom ...

, Kaohsiung

Kaohsiung, officially Kaohsiung City, is a special municipality located in southern Taiwan. It ranges from the coastal urban center to the rural Yushan Range with an area of . Kaohsiung City has a population of approximately 2.73 million p ...

, is the largest Buddhist monastery in Taiwan. Hsing Yun's stated position within Fo Guang Shan is that it is an "amalgam of all Eight Schools of Chinese Buddhism" (), including Chan. Fo Guang Shan is the most comprehensive of the major Buddhist organizations of Taiwan, focusing extensively on both social works and religious engagement.

In Taiwan, these four masters are popularly referred to as the " Four Heavenly Kings" of Taiwanese Buddhism, with their respective organizations Dharma Drum Mountain, Chung Tai Shan, Tzu Chi, and Fo Guang Shan being referred to as the " Four Great Mountains".

Spread of Chan Buddhism in Asia

Thiền in Vietnam

According to traditional accounts of Vietnam, in 580 an Indian monk named Vinītaruci () traveled to Vietnam after completing his studies with Sengcan, the third patriarch of Chinese Chan. This, then, would be the first appearance of Thiền Buddhism. Other early Thiền schools included that of Wu Yantong (), which was associated with the teachings of Mazu Daoyi, and the Thảo Đường (Caodong), which incorporated nianfo

250px, Chinese Nianfo carving

The Nianfo ( zh, t= 念佛, p=niànfó, alternatively in Japanese ; ; or ) is a Buddhist practice central to East Asian Buddhism. The Chinese term ''nianfo'' is a translation of Sanskrit '' '' ("recollection of th ...

chanting techniques; both were founded by Chinese monks.

Seon in Korea

Seon was gradually transmitted into Korea during the late Silla

Silla (; Old Korean: wikt:徐羅伐#Old Korean, 徐羅伐, Yale romanization of Korean, Yale: Syerapel, Revised Romanization of Korean, RR: ''Seorabeol''; International Phonetic Alphabet, IPA: ) was a Korean kingdom that existed between ...

period (7th through 9th centuries) as Korean monks of predominantly Hwaeom () and East Asian Yogācāra

East Asian Yogācāra refers to the Mahayana Buddhist traditions in East Asia which developed out of the History of Buddhism in India, Indian Buddhist Yogachara, Yogācāra (lit. "yogic practice") systems (also known as ''Vijñānavāda'', "the d ...

() background began to travel to China to learn the newly developing tradition. Seon received its most significant impetus and consolidation from the Goryeo

Goryeo (; ) was a Korean state founded in 918, during a time of national division called the Later Three Kingdoms period, that unified and ruled the Korea, Korean Peninsula until the establishment of Joseon in 1392. Goryeo achieved what has b ...

monk Jinul (知訥) (1158–1210), who established a reform movement and introduced kōan practice to Korea. Jinul established the Songgwangsa (松廣寺) as a new center of pure practice.

Zen in Japan

Zen

Zen (; from Chinese: ''Chán''; in Korean: ''Sŏn'', and Vietnamese: ''Thiền'') is a Mahayana Buddhist tradition that developed in China during the Tang dynasty by blending Indian Mahayana Buddhism, particularly Yogacara and Madhyamaka phil ...

was not introduced as a separate school in Japan until the 12th century when Eisai traveled to China and returned to establish a Linji lineage, which is known in Japan as the Rinzai. In 1215, Dōgen

was a Japanese people, Japanese Zen Buddhism, Buddhist Bhikkhu, monk, writer, poet, philosopher, and founder of the Sōtō school of Zen in Japan. He is also known as Dōgen Kigen (), Eihei Dōgen (), Kōso Jōyō Daishi (), and Busshō Dent� ...

, a younger contemporary of Eisai's, journeyed to China himself, where he became a disciple of the Caodong master Rujing. After his return, Dōgen

was a Japanese people, Japanese Zen Buddhism, Buddhist Bhikkhu, monk, writer, poet, philosopher, and founder of the Sōtō school of Zen in Japan. He is also known as Dōgen Kigen (), Eihei Dōgen (), Kōso Jōyō Daishi (), and Busshō Dent� ...

established the Sōtō school, the Japanese branch of Caodong.

The schools of Zen that currently exist in Japan are the Sōtō, Rinzai and Ōbaku. Of these, Sōtō is the largest and Ōbaku the smallest. Rinzai is itself divided into several subschools based on temple affiliation, including Myōshin-ji, Nanzen-ji, Tenryū-ji, Daitoku-ji

is a Rinzai school Zen Buddhist temple in the Murasakino neighborhood of Kita-ku in the city of Kyoto Japan. Its ('' sangō'') is . The Daitoku-ji temple complex is one of the largest Zen temples in Kyoto, covering more than . In addition to ...

, and Tōfuku-ji.

Chan in Indonesia

In the 20th century, during the First Buddhist revival, missionaries were sent to Indonesia and Malaysia. Ashin Jinarakkhita, who played a central role in the revival of Indonesian Buddhism, received ordination as a Chan śrāmaṇera on July 29, 1953

Chan in the Western world

Chan has become especially popular in its Japanese form. Although it is difficult to trace when the West first became aware of Chan as a distinct form of Buddhism, the visit of Soyen Shaku, a Japanese Zen monk, to Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

during the 1893 Parliament of the World's Religions is often pointed to as an event that enhanced its profile in the Western world. It was during the late 1950s and the early 1960s that the number of Westerners pursuing a serious interest in Zen, other than the descendants of Asian immigrants, reached a significant level.

Western Chan lineages

The first Chinese master to teach Westerners in North America was Hsuan Hua, who taught Chan and other traditions of Chinese Buddhism

Chinese Buddhism or Han Buddhism ( zh, s=汉传佛教, t=漢傳佛教, first=t, poj=Hàn-thoân Hu̍t-kàu, j=Hon3 Cyun4 Fat6 Gaau3, p=Hànchuán Fójiào) is a Chinese form of Mahayana Buddhism. The Chinese Buddhist canonJiang Wu, "The Chin ...

in San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

during the early 1960s. He went on to found the City Of Ten Thousand Buddhas, a monastery and retreat center located on a 237-acre (959,000 m2) property near Ukiah, California

Ukiah ( ; Pomo: ''Yokáya'', meaning "deep valley" or "south valley") is the county seat and largest city of Mendocino County, California, Mendocino County, in the North Coast (California), North Coast region of California. Ukiah had a populati ...

, and thus founding the Dharma Realm Buddhist Association and the Dharma Realm Buddhist University. Another Chinese Chan teacher with a Western following was Sheng Yen, a master trained in both the Caodong and Linji schools. He first visited the United States in 1978 under the sponsorship of the Buddhist Association of the United States, and subsequently founded the CMC Chan Meditation Center in Queens, New York

Queens is the largest by area of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Queens County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. Located near the western end of Long Island, it is bordered by the ...

and the Dharma Drum Retreat Center in Pine Bush, New York.[Dharma Drum Mountain]

Who Is Master Sheng-yen

Doctrinal background

Though Zen-narrative states that it is a "special transmission outside scriptures" which "did not stand upon words", Zen does have a rich doctrinal background.

Polarities

Classical Chinese Chan is characterised by a set of polarities: absolute-relative,

Absolute-relative

The Prajnaparamita

file:Medicine Buddha painted mandala with goddess Prajnaparamita in center, 19th century, Rubin.jpg, A Tibetan painting with a Prajñāpāramitā sūtra at the center of the mandala

Prajñāpāramitā means "the Perfection of Wisdom" or "Trans ...

sutras and Madhyamaka

Madhyamaka ("middle way" or "centrism"; ; ; Tibetic languages, Tibetan: དབུ་མ་པ་ ; ''dbu ma pa''), otherwise known as Śūnyavāda ("the Śūnyatā, emptiness doctrine") and Niḥsvabhāvavāda ("the no Svabhava, ''svabhāva'' d ...

emphasize the non-duality of form and emptiness: "form is emptiness, emptiness is form", as the ''Heart sutra

The ''Heart Sūtra'', ) is a popular sutra in Mahayana, Mahāyāna Buddhism. In Sanskrit, the title ' translates as "The Heart of the Prajnaparamita, Perfection of Wisdom".

The Sutra famously states, "Form is emptiness (''śūnyatā''), em ...

'' says.two truths doctrine

The Buddhism, Buddhist doctrine of the two truths (Sanskrit: '','' ) differentiates between two levels of ''satya'' (Sanskrit; Pāli: ''sacca''; meaning "truth" or "reality") in the teaching of Gautama Buddha, Śākyamuni Buddha: the "conventiona ...

and the Yogacara three natures and Trikaya

The Trikāya (, lit. "three bodies"; , ) is a fundamental Buddhist doctrine that explains the multidimensional nature of Buddhahood. As such, the Trikāya is the basic theory of Mahayana Buddhist theology of Buddhahood.

This concept posits that a ...

doctrines also give depictions of the interplay between the absolute and the relative.

Buddha-nature and śūnyatā

When Buddhism was introduced in China it was understood in native terms. Various sects struggled to attain an understanding of the Indian texts. The '' Tathāgatagarbha sūtras'' and the idea of the Buddha-nature

In Buddhist philosophy and soteriology, Buddha-nature ( Chinese: , Japanese: , , Sanskrit: ) is the innate potential for all sentient beings to become a Buddha or the fact that all sentient beings already have a pure Buddha-essence within ...

were endorsed because of the perceived similarities with the Tao

The Tao or Dao is the natural way of the universe, primarily as conceived in East Asian philosophy and religion. This seeing of life cannot be grasped as a concept. Rather, it is seen through actual living experience of one's everyday being. T ...

, which was understood as a transcendental reality underlying the world of appearances. Śūnyatā

''Śūnyatā'' ( ; ; ), translated most often as "emptiness", "Emptiness, vacuity", and sometimes "voidness", or "nothingness" is an Indian philosophical concept. In Buddhism, Jainism, Hinduism, and Indian philosophy, other Indian philosophi ...

at first was understood as pointing to the Taoist '' wu''.

The doctrine of the Buddha-nature asserts that all sentient beings have Buddha-nature

In Buddhist philosophy and soteriology, Buddha-nature ( Chinese: , Japanese: , , Sanskrit: ) is the innate potential for all sentient beings to become a Buddha or the fact that all sentient beings already have a pure Buddha-essence within ...

(Skt. ''Buddhadhātu'', "Buddha Element", "Buddha-Principle"), the element from which awakening springs. The ''Tathāgatagarbha sutras'' state that every living being has the potential to realize awakening. Hence Buddhism offers salvation to everyone, not only to monks or those who have freed themselves almost completely from karma in previous lives. The Yogacara theory of the Eight Consciousnesses

The Eight Consciousnesses (Skt. ''aṣṭa vijñānakāyāḥ'') are a classification developed in the tradition of the Yogacara, Yogācāra school of Mahayana Buddhism. They enumerate the five sense consciousnesses, supplemented by the mental ...

explains how sensory input and the mind create the world we experience, and obscure the alaya-jnana, which is equated to the Buddha-nature.

When this potential is realized, and the defilements have been eliminated, the Buddha-nature manifests as the Dharmakaya, the absolute reality which pervades everything in the world. In this way, it is also the primordial reality from which phenomenal reality springs. When this understanding is idealized, it becomes a transcendental reality beneath the world of appearances.

Sunyata points to the "emptiness" or no-"thing"-ness of all "things". Though we perceive a world of concrete and discrete objects, designated by names, on close analysis the "thingness" dissolves, leaving them "empty" of inherent existence. The ''Heart sutra'', a text from the prajñaparamita sutras, articulates this in the following saying in which the five skandhas are said to be "empty":

Yogacara explains this "emptiness" in an analysis of the way we perceive "things". Everything we conceive of is the result of the working of the five skandhas—results of perception, feeling, volition, and discrimination. The five skandhas together compose consciousness. The "things" we are conscious of are "mere concepts", not noumenon

In philosophy, a noumenon (, ; from ; : noumena) is knowledge posited as an Object (philosophy), object that exists independently of human sense. The term ''noumenon'' is generally used in contrast with, or in relation to, the term ''Phenomena ...

.

It took Chinese Buddhism several centuries to recognize that śūnyatā is not identical to "wu", nor does Buddhism postulate a permanent soul. The influence of those various doctrinal and textual backgrounds is still discernible in Zen. Zen teachers still refer to Buddha-nature, but the Zen tradition also emphasizes that Buddha-nature ''is'' śūnyatā, the absence of an independent and substantial self.

Sudden and gradual enlightenment

In Zen Buddhism two main views on the way to enlightenment are discernible, namely sudden and gradual enlightenment.

Early Chan recognized the "transcendence of the body and mind", followed by "non-defilement fknowledge and perception", or sudden insight into the true nature ( ''jiànxìng'') followed by gradual purification of intentions.

In the 8th century, Chan history was effectively refashioned by Shenhui, who created a dichotomy between the so-called East Mountain Teaching or "Northern School", led by Yuquan Shenxiu, and his own line of teaching, which he called the "Southern school". Shenhui placed Huineng into prominence as the sixth Chan-patriarch, and emphasized ''sudden enlightenment'', as opposed to the concurrent Northern School's alleged ''gradual enlightenment''. According to the ''sudden enlightenment'' propagated by Shenhui, insight into true nature is sudden; thereafter there can be no misunderstanding anymore about this true nature.

In the '' Platform Sutra'', the dichotomy between sudden and gradual is reconciled. Guifeng Zongmi, fifth-generation successor to Shenhui, also softened the edge between sudden and gradual. In his analysis, sudden awakening points to seeing into one's true nature, but is to be followed by a gradual cultivation to attain Buddhahood

In Buddhism, Buddha (, which in classic Indo-Aryan languages, Indic languages means "awakened one") is a title for those who are Enlightenment in Buddhism, spiritually awake or enlightened, and have thus attained the Buddhist paths to liberat ...

.

This gradual cultivation is also recognized by Dongshan Liangjie (Japanese ''Tōzan''), who described the five ranks of enlightenment.

Esoteric and exoteric transmission