Chickasaws on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Chickasaw ( ) are an

The origin of the Chickasaw is uncertain; 20th-century scholars, such as the

The origin of the Chickasaw is uncertain; 20th-century scholars, such as the  The first European contact with the Chickasaw was in 1540 when

The first European contact with the Chickasaw was in 1540 when

Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands

Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands, Southeastern cultures, or Southeast Indians are an ethnographic classification for Native Americans who have traditionally inhabited the area now part of the Southeastern United States and the no ...

, United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

. Their traditional territory was in northern Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

, northwestern and northern Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

, western Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

and southwestern Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

. Their language is classified as a member of the Muskogean

Muskogean ( ; also Muskhogean) is a language family spoken in the Southeastern United States. Members of the family are Indigenous Languages of the Americas. Typologically, Muskogean languages are highly synthetic and agglutinative. One docume ...

language family. In the present day, they are organized as the federally recognized

This is a list of federally recognized tribes in the contiguous United States. There are also federally recognized Alaska Native tribes. , 574 Indian tribes are legally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) of the United States.

Chickasaw Nation

The Chickasaw Nation () is a federally recognized Indigenous nation with headquarters in Ada, Oklahoma, in the United States. The Chickasaw Nation descends from an Indigenous population historically located in the southeastern United States, in ...

.

Chickasaw people have a migration story in which they moved from a land west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

to reach present-day northeast Mississippi, northwest Alabama, and into Lawrence County, Tennessee. They had interaction with French, English, and Spanish colonists during the colonial period. The United States considered the Chickasaw one of the Five Civilized Tribes

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by the United States government in the early federal period of the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast: the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Cr ...

of the Southeast, as they adopted numerous practices of European Americans. Resisting European-American settlers encroaching on their territory, they were forced by the U.S. government to sell their traditional lands in the 1832 Treaty of Pontotoc Creek

The Treaty of Pontotoc Creek was a treaty signed on October 20, 1832 by representatives of the United States and the Chiefs of the Chickasaw Chickasaw Nation, Nation assembled at the National Council House on Pontotoc Creek in Pontotoc, Mississipp ...

and move to Indian Territory

Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United States, ...

(Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Texas to the south and west, Kansas to the north, Missouri to the northea ...

) during the era of Indian removal in the 1830s.

Most of their descendants remain as residents of what is now Oklahoma. The Chickasaw Nation in Oklahoma is the 13th-largest federally recognized tribe

A federally recognized tribe is a Native American tribe recognized by the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs as holding a government-to-government relationship with the US federal government. In the United States, the Native American tribe ...

in the United States. Its members are related to the Choctaw

The Choctaw ( ) people are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States, originally based in what is now Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama. The Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choct ...

and share a common history with them. The Chickasaw were divided into two groups ( moieties): the ''Imosak Cha'a'matrilineal descent

Matrilineality, at times called matriliny, is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which people identify with their matriline, their mother's lineage, and which can involve the inheritanc ...

, in which inheritance and descent are traced through the maternal line. Children are considered born into the mother's family and clan, and gain their social status from her. Women controlled most property and hereditary leadership in the tribe passed through the maternal line.

Etymology

The name Chickasaw, as noted by anthropologist John Swanton, belonged to a Chickasaw minko', or leader. "Chickasaw" is the English spelling of ''Chikashsha'' (), meaning "comes from Chicsa". In an 1890 extra census bulletin on the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muskogee, and Seminole, a history of the Choctaw and Chickasaw was included that was written by R.W. McAdam. McAdam claimed that the word "Chikasha" meant "rebel" in the Choctaw language. Spanish explorerHernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1497 – 21 May 1542) was a Spanish explorer and conquistador who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire in Peru, ...

had recorded the people as ''Chicaza'' when his expedition came into contact with them in 1540; the Spanish were the first known Europeans to explore the North American Southeast.

The suffix ''-mingo'' (Chickasaw: ''minko'') is used to identify a chief. For example, '' Tishomingo'' was the name of a famous Chickasaw chief. The towns of Tishomingo in Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

and Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Texas to the south and west, Kansas to the north, Missouri to the northea ...

were named for him, as was Tishomingo County in Mississippi.

History

The origin of the Chickasaw is uncertain; 20th-century scholars, such as the

The origin of the Chickasaw is uncertain; 20th-century scholars, such as the archaeologist

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

Patricia Galloway, theorize that the Chickasaw and Choctaw split into distinct peoples in the 17th century from the remains of Plaquemine culture

The Plaquemine culture was an archaeological culture (circa 1200 to 1700 CE) centered on the Lower Mississippi River valley. It had a deep history in the area stretching back through the earlier Coles Creek (700-1200 CE) and Troyville cultures ...

and other groups whose ancestors had lived in the lower Mississippi Valley for thousands of years. When Europeans first encountered them, the Chickasaw were living in villages in what is now northeastern Mississippi.

The Chickasaw are believed to have migrated into Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

from the west, as their oral history attests. They and the Choctaw were once one people and migrated from west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

into present-day Mississippi in prehistoric times; the Chickasaw and Choctaw split along the way. The Mississippian Ideological Interaction Sphere spanned the Eastern Woodlands

The Eastern Woodlands is a cultural region of the Indigenous people of North America. The Eastern Woodlands extended roughly from the Atlantic Ocean to the eastern Great Plains, and from the Great Lakes region to the Gulf of Mexico, which is now ...

. The Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a collection of Native American societies that flourished in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from approximately 800 to 1600 CE, varying regionally. It was known for building la ...

s emerged from previous moundbuilding societies by 880 CE. They built complex, dense villages supporting a stratified society, with centers throughout the Mississippi and Ohio River Valleys and their tributaries.

In the 15th century, proto-Chickasaw people left the Tombigbee Valley after the collapse of the Moundville chiefdom. Chickasaw culture believe that the foundation of Chickasaw from proto-Chickasaw peoples was determined by the Mississippi River. The Mississippi River is referred to as ''Sakti Lhafa’ Okhina'' in '' Chikashanompa','' which means “scored bluff waterway", known today as the Chickasaw Bluffs. Settling upon the river provided the people with a symbolic sense of new beginngings, washing away the past of the proto-Chickasaw and entering into a new modern age of the Chickasaw. The migration marked their split from other Native American communities like the Choctaws. They settled into the upper Yazoo and Pearl River

The Pearl River (, or ) is an extensive river system in southern China. "Pearl River" is often also used as a catch-all for the watersheds of the Pearl tributaries within Guangdong, specifically the Xi ('west'), Bei ('north'), and Dong ( ...

valleys in present-day Mississippi. Historian Arrell Gibson

Arrell Morgan Gibson (1921–1987) was a historian and author specializing in the history of the state of Oklahoma.

Gibson was born in Pleasanton, Kansas on December 1, 1921. He earned degrees from Missouri Southern State College and the Univers ...

and anthropologist John R. Swanton believed the Chickasaw Old Fields were in Madison County, Alabama

Madison County is a County (United States), county located in the north central portion of the U.S. state of Alabama. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 Census, the population was 388,153, and according to a 2023 population estimate the ...

.

The Choctaws relayed to Bernard Romans their creation myth, saying that they came "out of a hole in the ground, which they shew between their nation and the Chickasaws." Another version of the Chickasaw creation story is that they arose at ''Nanih Waiya

Nanih Waiya (alternately spelled Nunih Waya; Choctaw for 'slanting mound') is an ancient platform mound in southern Winston County, Mississippi, constructed by indigenous people during the Middle Woodland period, about 300 to 600 CE. Since the ...

,'' a great earthwork mound

A mound is a wikt:heaped, heaped pile of soil, earth, gravel, sand, rock (geology), rocks, or debris. Most commonly, mounds are earthen formations such as hills and mountains, particularly if they appear artificial. A mound may be any rounded ...

built about 300 CE by Woodland

A woodland () is, in the broad sense, land covered with woody plants (trees and shrubs), or in a narrow sense, synonymous with wood (or in the U.S., the '' plurale tantum'' woods), a low-density forest forming open habitats with plenty of sunli ...

peoples. It is also sacred to the Choctaw, who share a similar story. The mound was built about 1400 years before the coalescence of each of these peoples as ethnic

An ethnicity or ethnic group is a group of people with shared attributes, which they collectively believe to have, and long-term endogamy. Ethnicities share attributes like language, culture, common sets of ancestry, traditions, society, re ...

groups.

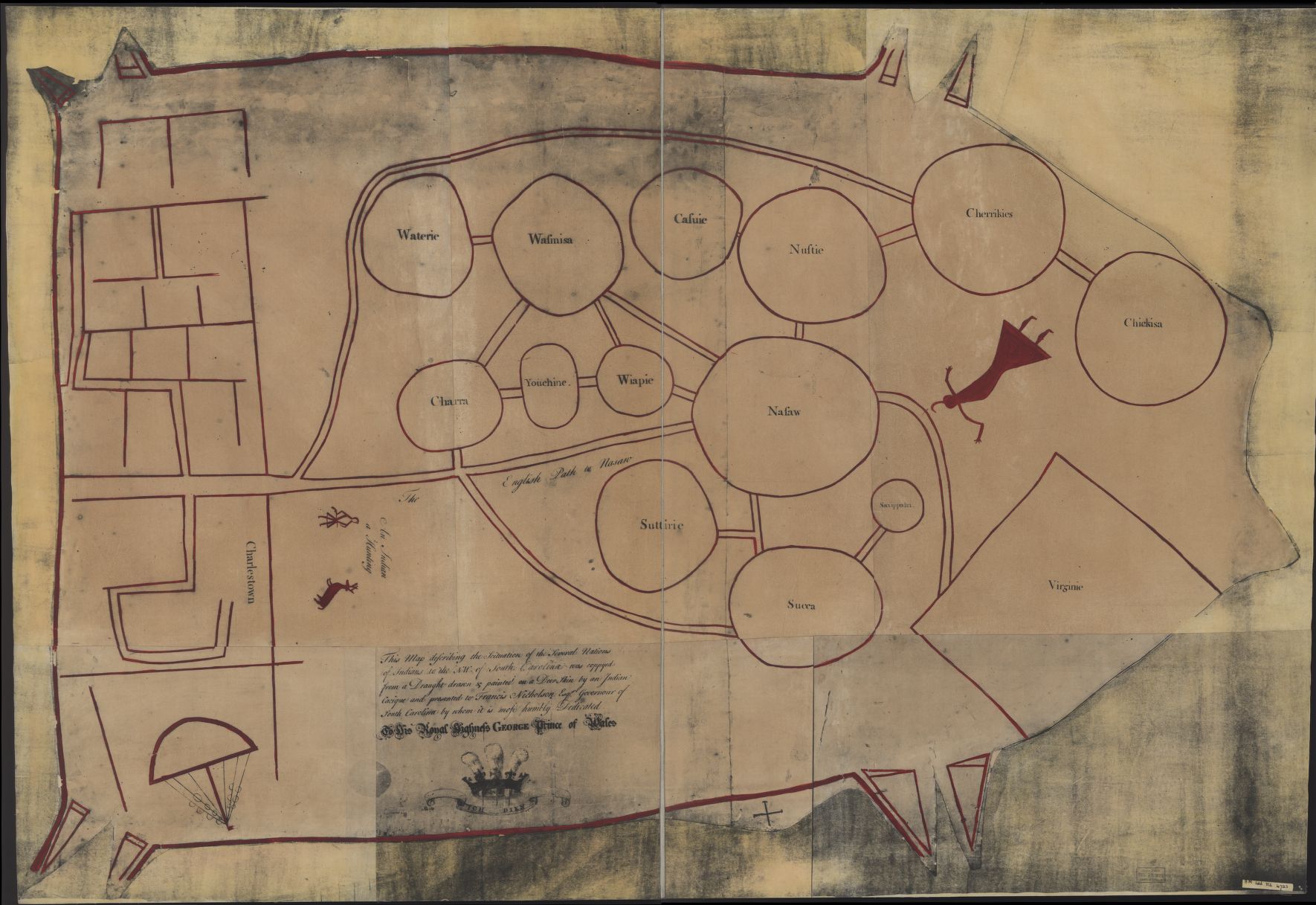

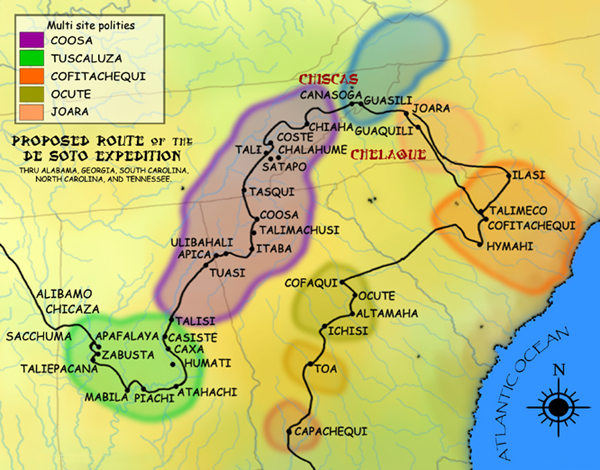

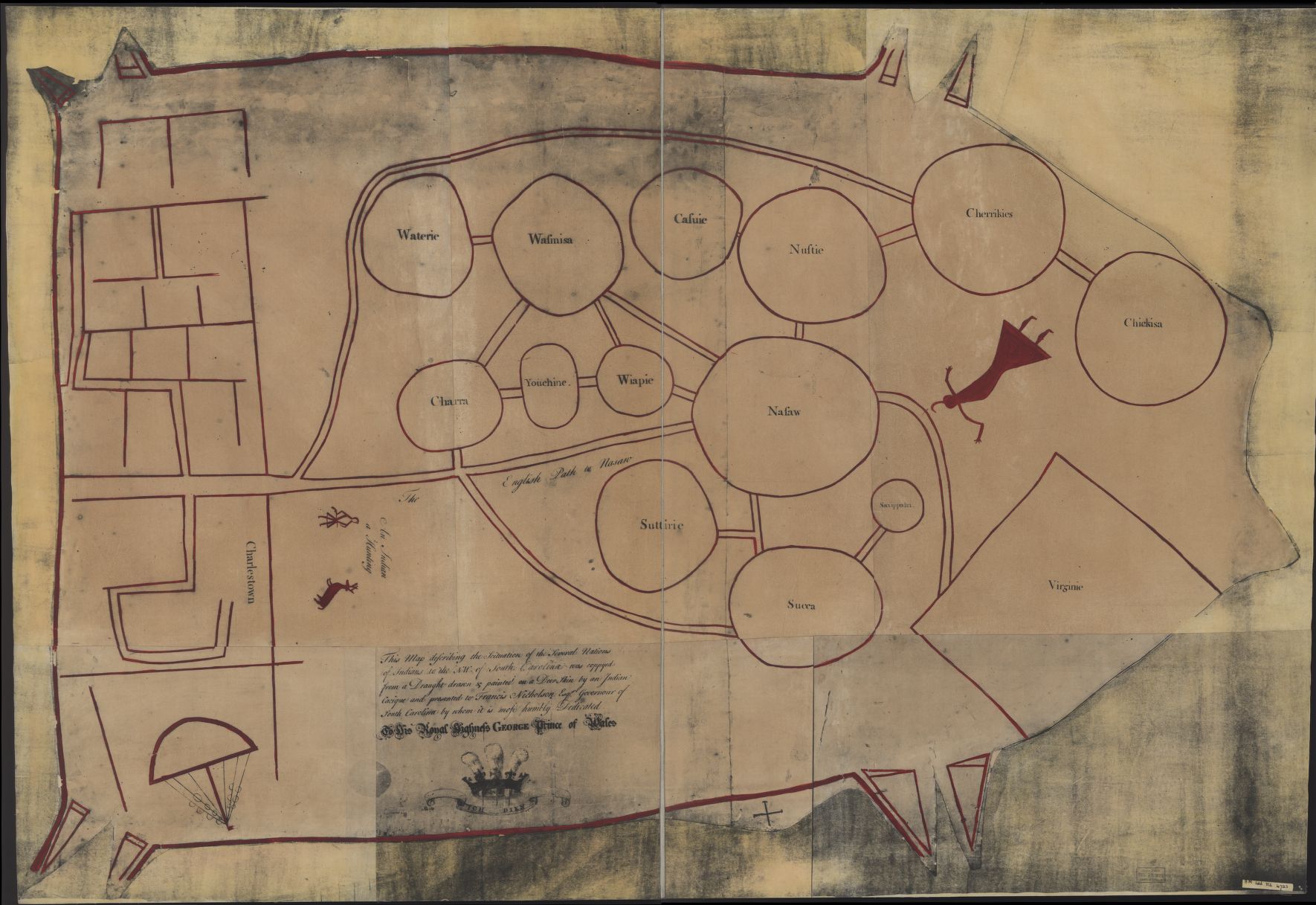

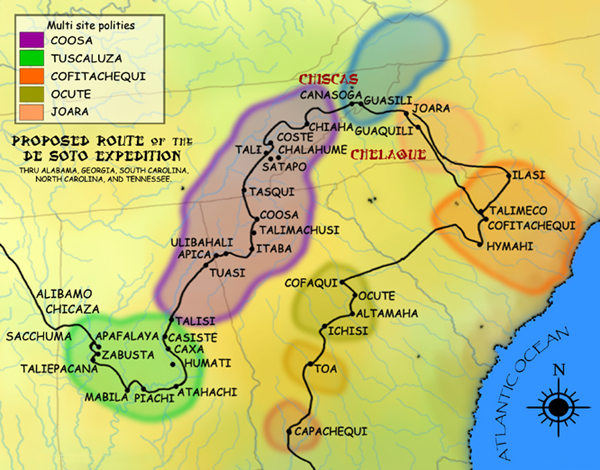

The first European contact with the Chickasaw was in 1540 when

The first European contact with the Chickasaw was in 1540 when Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many countries in the Americas

**Spanish cuisine

**Spanish history

**Spanish culture

...

explorer Hernando de Soto encountered the tribe and stayed in one of their towns, most likely near present-day Starkville, Mississippi

Starkville is a city in and the county seat of Oktibbeha County, Mississippi, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, Starkville's population is 24,360, making it the 16th-most populated city in Mississippi. Starkville is the largest ...

. The Chickasaw were alert around the Spanish, placing war banners implying their intentions for when they would meet the Spanish. The Chickasaw additionally gathered intel that the Spanish recently fought a nearly-lost battle in the town of Mabila, led by leader Tascalusa, only a few months prior to the Spanish entering their territory. In the winter of 1540, conflict finally struck between Chickasaw warriors and the Spanish Explorers. The reasonings for the battle vary from Spanish looting Chickasaw food storages, to general heated animosity between the two groups. After various disagreements, the Chickasaw attacked the De Soto expedition in a nighttime raid, nearly destroying the force. The Spanish moved on quickly.

The Chickasaw began to establish trading relationships with English colonists in the Province of Carolina

The Province of Carolina was a colony of the Kingdom of England (1663–1707) and later the Kingdom of Great Britain (1707–1712) that existed in North America and the Caribbean from 1663 until the Carolinas were partitioned into North and Sou ...

after that colony was established in 1670. After acquiring firearms from colonial merchants in Carolina, Chickasaw raiders began to attack settlements belonging to a rival tribe, the Choctaw

The Choctaw ( ) people are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States, originally based in what is now Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama. The Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choct ...

, in order to acquire captives which they sold to the colonists. These raids largely subsided after the Choctaw acquired firearms of their own from the French.

Allied with British colonists in the Southern Colonies

The Southern Colonies within British America consisted of the Province of Maryland, the Colony of Virginia, the Province of Carolina (in 1712 split into North and South Carolina), and the Province of Georgia. In 1763, the newly created colonies ...

, the Chickasaw were often at war with the French and the Choctaw in the 18th century, such as in the Battle of Ackia on May 26, 1736. Skirmishes continued until France ceded its claims to the region east of the Mississippi River after being defeated by the British in the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

(called the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

in North America).

Following the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

, in 1793–94, the Chickasaw under Chief Piomingo fought as allies of the new United States under General Anthony Wayne

Anthony Wayne (January 1, 1745 – December 15, 1796) was an American soldier, officer, statesman, and a Founding Father of the United States. He adopted a military career at the outset of the American Revolutionary War, where his military expl ...

against the Indians of the old Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from part of the unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolution. Established ...

. The Shawnee

The Shawnee ( ) are a Native American people of the Northeastern Woodlands. Their language, Shawnee, is an Algonquian language.

Their precontact homeland was likely centered in southern Ohio. In the 17th century, they dispersed through Ohi ...

and other allied Northwest Indians were defeated in the Battle of Fallen Timbers

The Battle of Fallen Timbers (20 August 1794) was the final battle of the Northwest Indian War, a struggle between Indigenous peoples of North America, Native American tribes affiliated with the Northwestern Confederacy and their Kingdom of Gre ...

on August 20, 1794.

A 19th-century historian, Horatio Cushman, wrote, "Neither the Choctaws nor Chicksaws ever engaged in war against the American people, but always stood as their faithful allies." Cushman believed the Chickasaw, along with the Choctaw, may have had origins in present-day Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

and migrated north.

Frenchman Le Clerc Milfort, when writing about the Creek Indians, echoed the same view. That theory, however, does not have consensus; archeological research, as noted above, has revealed the peoples had long histories in the Mississippi area and independently developed complex cultures.

Trade

Despite being smaller than many surrounding tribes, the Chickasaw established themselves as a trade power within the region. Aided by their strategic location on the Mississippi, the tribe was able to exchange goods with neighboring parties. The tactical importance of the Chickasaw was not lost on the British; in 1755, the Imperial Indian Superintendent Edmund Atkin recognized the tribe’s position: "It is not possible to cast an Eye ever so lightly over a Map, without being struck with the Importance of the hickasaws'situation." The Chickasaw made their first formal contact with the British shortly after the founding of Charles Town in 1670; this occurred when Dr. Woordward of Carolina attempted to establish trade ties while on course to Alabama. Although the British outpost of Charles Town was located over 850 km from Chickasaw territory, the two groups managed to engage initially in an exchange of deerskin. Shortly after making contact with the British, the Chickasaw began to trade with the French as the Europeans established themselves within Louisiana. Within Chickasaw society, trade was categorized under either white (peace) or red (war) routes. To maintain this duality, a War Chief and Peace chief oversaw the respective red and white divisions. Over time, the French union would be dictated by the leaders of the white division, while the English relationship was defined by the red. Ultimately, despite French proximity to Chickasaw land, the tribe elected to prioritize their trade routes with the British. The alliance between the British and the Chickasaw was a strategic defense against the French and their native allies. Supported by the slave trade, the Chickasaw sought weapons in exchange for captured members of rival tribes. As they were smaller than the Choctaw and other abutting indigenous groups, the weapons were critical to the defense of their native land.Tribal lands

In 1797, a general appraisal of the tribe and its territorial bounds was made by Abraham Bishop of New Haven, who wrote:

United States relations

George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

(first U.S. President) and Henry Knox

Henry Knox (July 25, 1750 – October 25, 1806) was an American military officer, politician, bookseller, and a Founding Father of the United States. Knox, born in Boston, became a senior general of the Continental Army during the Revolutionar ...

(first U.S. Secretary of War) proposed the cultural transformation of Native Americans.

Washington believed that Native Americans were equals, but that their society was inferior. He formulated a policy to encourage the "civilizing" process, and Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

continued it.

Historian Robert Remini wrote, "They presumed that once the Indians adopted the practice of private property, built homes, farmed, educated their children, and embraced Christianity, these Native Americans would win acceptance from white Americans."

Washington's six-point plan included impartial justice toward Indians; regulated buying of Indian lands; promotion of commerce; promotion of experiments to civilize or improve Indian society; presidential authority to give presents; and punishing those who violated Indian rights.

The government-appointed Indian agent

In United States history, an Indian agent was an individual authorized to interact with American Indian tribes on behalf of the U.S. government.

Agents established in Nonintercourse Act of 1793

The federal regulation of Indian affairs in the Un ...

s, such as Benjamin Hawkins, who became Superintendent of Indian Affairs for all the territory south of the Ohio River. He and other agents lived among the Indians to teach them, through example and instruction, how to live like whites. Hawkins married a Muscogee Creek

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek or just Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language; English: ), are a group of related Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern WoodlandsFort Hampton in 1810 in present-day

The Chickasaw signed the Treaty of Hopewell in 1786. Article 11 of that treaty states: "The hatchet shall be forever buried, and the peace given by the United States of America, and friendship re-established between the said States on the one part, and the Chickasaw nation on the other part, shall be universal, and the contracting parties shall use their utmost endeavors to maintain the peace given as aforesaid, and friendship re-established." Benjamin Hawkins attended this signing.

The Chickasaw signed the Treaty of Hopewell in 1786. Article 11 of that treaty states: "The hatchet shall be forever buried, and the peace given by the United States of America, and friendship re-established between the said States on the one part, and the Chickasaw nation on the other part, shall be universal, and the contracting parties shall use their utmost endeavors to maintain the peace given as aforesaid, and friendship re-established." Benjamin Hawkins attended this signing.

This was known as the "

, Chickasaw Letters -- 1832, Chickasaw Historical Research Website (Kerry M. Armstrong), accessed 12 December 2011 After Levi's death in 1834, the Chickasaw people were forced upon the

Unlike other tribes who received land grants in exchange for ceding territory, the Chickasaw held out for financial compensation: they were to receive $3 million U.S. dollars from the United States for their lands east of the Mississippi River.

In 1836 after a bitter five-year debate within the tribe, the Chickasaw had reached an agreement to purchase land in

Unlike other tribes who received land grants in exchange for ceding territory, the Chickasaw held out for financial compensation: they were to receive $3 million U.S. dollars from the United States for their lands east of the Mississippi River.

In 1836 after a bitter five-year debate within the tribe, the Chickasaw had reached an agreement to purchase land in  When the Chickasaw reached Indian Territory, the United States began to administer to them through the Choctaw Nation, and later merged them for administrative reasons. The Chickasaw wrote their own constitution in the 1850s, an effort contributed to by Holmes Colbert.

After several decades of mistrust between the two peoples, in the twentieth century, the Chickasaw re-established their independent government. They are federally recognized as the Chickasaw Nation. The government is headquartered in

When the Chickasaw reached Indian Territory, the United States began to administer to them through the Choctaw Nation, and later merged them for administrative reasons. The Chickasaw wrote their own constitution in the 1850s, an effort contributed to by Holmes Colbert.

After several decades of mistrust between the two peoples, in the twentieth century, the Chickasaw re-established their independent government. They are federally recognized as the Chickasaw Nation. The government is headquartered in

Because the Chickasaw allied with the Confederacy, after the Civil War the United States government required the nation to make a new peace treaty in 1866. It included the provision that they emancipate the enslaved African Americans and provide full citizenship to those who wanted to stay in the Chickasaw Nation.

These people and their descendants became known as the Chickasaw Freedmen. Descendants of the Freedmen continue to live in Oklahoma. Today, the Choctaw-Chickasaw Freedmen Association of Oklahoma represents the interests of Freedmen descendants in both of these tribes.

But the Chickasaw Nation never granted citizenship to the Chickasaw Freedmen. The only way that African Americans could become citizens at that time was to have one or more Chickasaw parents or to petition for citizenship and go through the process available to other non-Natives, even if they were of known partial Chickasaw descent in an earlier generation. Because the Chickasaw Nation did not provide citizenship to their Freedmen after the Civil War (it would have been akin to formal adoption of individuals into the tribe), they were penalized by the U.S. Government. It took more than half of their territory, with no compensation. They lost territory that had been negotiated in treaties in exchange for their use after removal from the Southeast.

Because the Chickasaw allied with the Confederacy, after the Civil War the United States government required the nation to make a new peace treaty in 1866. It included the provision that they emancipate the enslaved African Americans and provide full citizenship to those who wanted to stay in the Chickasaw Nation.

These people and their descendants became known as the Chickasaw Freedmen. Descendants of the Freedmen continue to live in Oklahoma. Today, the Choctaw-Chickasaw Freedmen Association of Oklahoma represents the interests of Freedmen descendants in both of these tribes.

But the Chickasaw Nation never granted citizenship to the Chickasaw Freedmen. The only way that African Americans could become citizens at that time was to have one or more Chickasaw parents or to petition for citizenship and go through the process available to other non-Natives, even if they were of known partial Chickasaw descent in an earlier generation. Because the Chickasaw Nation did not provide citizenship to their Freedmen after the Civil War (it would have been akin to formal adoption of individuals into the tribe), they were penalized by the U.S. Government. It took more than half of their territory, with no compensation. They lost territory that had been negotiated in treaties in exchange for their use after removal from the Southeast.

The Chickasaw Nation of Oklahoma

official site

Chickasaw.tv

The online video network of the Chickasaw Nation.

Chickasaw Nation Industries (government contracting arm of the Chickasaw Nation)

"Chickasaws: The Unconquerable People", a brief history by Greg O'Brien, Ph.D.

Pashofa recipe

Tanshpashofa recipe

Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture - Chickasaw

{{authority control Muskogean tribes Native American tribes in Alabama Native American tribes in Mississippi Native American tribes in Oklahoma South Appalachian Mississippian culture Native American people in the American Revolution

Limestone County, Alabama

Limestone County is a county of the U.S. state of Alabama. As of the 2020 census, the county's population was 103,570. Its county seat is Athens. The county is named after Limestone Creek. Limestone County is included in the Huntsville, AL ...

. The fort was designed to keep settlers out of Chickasaw territory and was one of the few forts constructed in the United States to protect Native American land claims.

Treaty of Hopewell (1786)

The Chickasaw signed the Treaty of Hopewell in 1786. Article 11 of that treaty states: "The hatchet shall be forever buried, and the peace given by the United States of America, and friendship re-established between the said States on the one part, and the Chickasaw nation on the other part, shall be universal, and the contracting parties shall use their utmost endeavors to maintain the peace given as aforesaid, and friendship re-established." Benjamin Hawkins attended this signing.

The Chickasaw signed the Treaty of Hopewell in 1786. Article 11 of that treaty states: "The hatchet shall be forever buried, and the peace given by the United States of America, and friendship re-established between the said States on the one part, and the Chickasaw nation on the other part, shall be universal, and the contracting parties shall use their utmost endeavors to maintain the peace given as aforesaid, and friendship re-established." Benjamin Hawkins attended this signing.

Treaty of 1818

In 1818, leaders of the Chickasaw signed several treaties, including the Treaty of Tuscaloosa, which ceded all claims to land north of the southern border of Tennessee up to theOhio River

The Ohio River () is a river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing in a southwesterly direction from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to its river mouth, mouth on the Mississippi Riv ...

(the southern border of Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

and the Illinois Territory

The Territory of Illinois was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 1, 1809, until December 3, 1818, when the southern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Illinois. Its ...

).Pate, James C. ''Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture''. "Chickasaw." Retrieved December 27, 201This was known as the "

Jackson Purchase

The Jackson Purchase, also known as the Purchase Region or simply the Purchase, is a region in the U.S. state of Kentucky bounded by the Mississippi River to the west, the Ohio River to the north, and the Tennessee River to the east.

Jackson's P ...

." The Chickasaw were allowed to retain a four-square-mile reservation but were required to lease the land to European immigrants.

Colbert legacy (19th century)

In the mid-18th century, an American-born trader of Scots and Chickasaw ancestry by the name of James Logan Colbert settled in the Muscle Shoals area of Alabama. He lived there for the next 40 years, where he married three high-ranking Chickasaw women in succession. Chickasaw chiefs and high-status women found such marriages of strategic benefit to the tribe, as it gave them advantages with traders over other groups. Colbert and his wives had numerous children, including seven sons: William, Jonathan, George, Levi, Samuel, Joseph, and Pittman (or James). Six survived to adulthood (Jonathan died young.) The Chickasaw had amatrilineal

Matrilineality, at times called matriliny, is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which people identify with their matriline, their mother's lineage, and which can involve the inheritan ...

system, in which children were considered born into the mother's clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, a clan may claim descent from a founding member or apical ancestor who serves as a symbol of the clan's unity. Many societie ...

; and they gained their status in the tribe from her family. Property and hereditary leadership passed through the maternal line, and the mother's eldest brother was the main male mentor of the children, especially of boys. Because of the status of their mothers, for nearly a century, the Colbert-Chickasaw sons and their descendants provided critical leadership during the tribe's greatest challenges. They had the advantage of growing up bilingual.

Of these six sons, William "Chooshemataha" Colbert (named after James Logan's father, Chief/Major William d'Blainville "Piomingo" Colbert) served with General Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

during the Creek Wars of 1813–14. He also had served during the Revolutionary wars and received a commission from President George Washington in 1786 along with his namesake grandfather. His brothers Levi

Levi ( ; ) was, according to the Book of Genesis, the third of the six sons of Jacob and Leah (Jacob's third son), and the founder of the Israelites, Israelite Tribe of Levi (the Levites, including the Kohanim) and the great-grandfather of Aaron ...

("Itawamba Mingo") and George Colbert

George Colbert (November 7, 1839) was an early 19th century, 19th-century Chickasaw leader who commanded 350 Chickasaw auxiliary troops who fought under Major General Andrew Jackson during the Creek War. He also served as an Officer (armed forc ...

("Tootesmastube") also had military service in support of the United States. In addition, the two each served as interpreters and negotiators for chiefs of the tribe during the period of removal. Levi Colbert served as principal chief, which may have been a designation by the Americans, who did not understand the decentralized nature of the chiefs' council, based on the tribe reaching broad consensus for major decisions. An example is that more than 40 chiefs from the Chickasaw Council, representing clans

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, a clan may claim descent from a founding member or apical ancestor who serves as a symbol of the clan's unity. Many societie ...

and villages, signed a letter in November 1832 by Levi Colbert to President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

, complaining about treaty negotiations with his appointee General John Coffee

John R. Coffee (June 2, 1772 – July 7, 1833) was an American planter of English descent, and a state militia brigadier general in Tennessee. He commanded troops under General Andrew Jackson during the Creek Wars (1813–14) and the Battle ...

."Levi Colbert to President Andrew Jackson, 22 NOV 1832", Chickasaw Letters -- 1832, Chickasaw Historical Research Website (Kerry M. Armstrong), accessed 12 December 2011 After Levi's death in 1834, the Chickasaw people were forced upon the

Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was the forced displacement of about 60,000 people of the " Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850, and the additional thousands of Native Americans and their black slaves within that were ethnically cleansed by the U ...

. His brother, George Colbert, reluctantly succeeded him as chief and principal negotiator, because he was bilingual and bicultural. George "Tootesmastube" Colbert never reached the Chickasaw's "Oka Homa" (red waters); he died on Choctaw territory, Fort Towson

Fort Towson was a frontier outpost for Frontier Army Quartermasters along the Permanent Indian Frontier located about two miles (3 km) northeast of the present community of Fort Towson, Oklahoma. Located on Gates Creek near the confluen ...

, en route.

Treaty of Pontotoc Creek and Removal (1832-1837)

In 1832 after the state of Mississippi declared its jurisdiction over the Chickasaw Indians, outlawing tribal self-governance, Chickasaw chiefs assembled at the national council house on October 20, 1832 and signed theTreaty of Pontotoc Creek

The Treaty of Pontotoc Creek was a treaty signed on October 20, 1832 by representatives of the United States and the Chiefs of the Chickasaw Chickasaw Nation, Nation assembled at the National Council House on Pontotoc Creek in Pontotoc, Mississipp ...

, ceding their remaining Mississippi territory to the U.S. and agreeing to find land and relocate west of the Mississippi River. Between 1832 and 1837, the Chickasaw would make further negotiations and arrangements for their removal.  Unlike other tribes who received land grants in exchange for ceding territory, the Chickasaw held out for financial compensation: they were to receive $3 million U.S. dollars from the United States for their lands east of the Mississippi River.

In 1836 after a bitter five-year debate within the tribe, the Chickasaw had reached an agreement to purchase land in

Unlike other tribes who received land grants in exchange for ceding territory, the Chickasaw held out for financial compensation: they were to receive $3 million U.S. dollars from the United States for their lands east of the Mississippi River.

In 1836 after a bitter five-year debate within the tribe, the Chickasaw had reached an agreement to purchase land in Indian Territory

Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United States, ...

from the previously removed Choctaw. They paid the Choctaw $530,000 for the westernmost part of their land. The first group of Chickasaw moved in 1837.

The Chickasaw gathered at Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in Shelby County, Tennessee, United States, and its county seat. Situated along the Mississippi River, it had a population of 633,104 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of municipalities in Tenne ...

, on July 4, 1837, with all of their portable assets: belongings, livestock, and enslaved African Americans. Three thousand and one Chickasaw crossed the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

, following routes established by the Choctaw and Creek. During the journey, often referred to as the Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was the forced displacement of about 60,000 people of the " Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850, and the additional thousands of Native Americans and their black slaves within that were ethnically cleansed by the U ...

, more than 500 Chickasaw died of dysentery

Dysentery ( , ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications may include dehyd ...

and smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

.

When the Chickasaw reached Indian Territory, the United States began to administer to them through the Choctaw Nation, and later merged them for administrative reasons. The Chickasaw wrote their own constitution in the 1850s, an effort contributed to by Holmes Colbert.

After several decades of mistrust between the two peoples, in the twentieth century, the Chickasaw re-established their independent government. They are federally recognized as the Chickasaw Nation. The government is headquartered in

When the Chickasaw reached Indian Territory, the United States began to administer to them through the Choctaw Nation, and later merged them for administrative reasons. The Chickasaw wrote their own constitution in the 1850s, an effort contributed to by Holmes Colbert.

After several decades of mistrust between the two peoples, in the twentieth century, the Chickasaw re-established their independent government. They are federally recognized as the Chickasaw Nation. The government is headquartered in Ada, Oklahoma

Ada is a city in and the county seat of Pontotoc County, Oklahoma, Pontotoc County, Oklahoma, United States. The population was 16,481 at the 2020 United States census. The city was named for Ada Reed, the daughter of an early settler, and was in ...

.

American Civil War (1861)

The Chickasaw Nation was the first of the Five Civilized Tribes to become allies of theConfederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), also known as the Confederate States (C.S.), the Confederacy, or Dixieland, was an List of historical unrecognized states and dependencies, unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United State ...

.

In addition, they resented the United States government, which had forced them off their lands and failed to protect them against the Plains tribes in the West. In 1861, as tensions rose related to the sectional conflict, the US Army abandoned Fort Washita

Fort Washita is the former United States military post and National Historic Landmark located in Durant, Oklahoma on SH 199. Established in 1842 by General (later President) Zachary Taylor to protect citizens of the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nati ...

, leaving the Chickasaw Nation defenseless against the Plains tribes. Confederate officials recruited the American Indian tribes with suggestions of an Indian state if they were victorious in the Civil War.

The Chickasaw passed a resolution allying with the Confederacy, which was signed by Governor Cyrus Harris on May 25, 1861.

At the beginning of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, Albert Pike

Albert Pike (December 29, 1809April 2, 1891) was an American author, poet, orator, editor, lawyer, jurist and Confederate States Army general who served as an List of justices of the Arkansas Supreme Court, associate justice of the Arkansas Supr ...

was appointed as Confederate envoy to Native Americans. In this capacity, he negotiated several treaties, including the Treaty with Choctaws and Chickasaws

The Treaty with Choctaws and Chickasaws was a treaty signed on July 12, 1861 between the Choctaw and Chickasaw (two American Indians in the United States, American Indian nations) and the Confederate States of America, Confederate States.

At th ...

in July 1861. The treaty covered sixty-four terms, covering many subjects such as Choctaw and Chickasaw nation sovereignty

Sovereignty can generally be defined as supreme authority. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within a state as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the person, body or institution that has the ultimate au ...

, Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), also known as the Confederate States (C.S.), the Confederacy, or Dixieland, was an List of historical unrecognized states and dependencies, unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United State ...

citizenship possibilities and an entitled delegate in the House of Representatives of the Confederate States of America. Because the Chickasaw sided with the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, they had to forfeit some of their land afterward. In addition, the US renegotiated their treaty, insisting on their emancipation of slaves and offering citizenship to those who wanted to stay in the Chickasaw Nation. If they returned to the United States, they would have US citizenship.

Government

The Chickasaws were first combined with theChoctaw Nation

The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma (Choctaw: ''Chahta Okla'') is a Native American reservation occupying portions of southeastern Oklahoma in the United States. At roughly , it is the second-largest reservation in area after the Navajo, exceeding t ...

and their area was called the Chickasaw District. Although originally the western boundary of the Choctaw Nation extended to the 100th meridian, virtually no Chickasaw lived west of the Cross Timbers

The term Cross Timbers, also known as Ecoregion 29, Central Oklahoma/Texas Plains, is used to describe a strip of land in the United States that runs from southeastern Kansas across Central Oklahoma to Central Texas. Made up of a mix of prairi ...

. The area was subject to continual raiding by the Indians on the Southern Plains. The United States eventually leased the area between the 100th and 98th meridians for the use of the Plains tribes. The area was referred to as the "Leased District".

Treaties

Post–Civil War

Because the Chickasaw allied with the Confederacy, after the Civil War the United States government required the nation to make a new peace treaty in 1866. It included the provision that they emancipate the enslaved African Americans and provide full citizenship to those who wanted to stay in the Chickasaw Nation.

These people and their descendants became known as the Chickasaw Freedmen. Descendants of the Freedmen continue to live in Oklahoma. Today, the Choctaw-Chickasaw Freedmen Association of Oklahoma represents the interests of Freedmen descendants in both of these tribes.

But the Chickasaw Nation never granted citizenship to the Chickasaw Freedmen. The only way that African Americans could become citizens at that time was to have one or more Chickasaw parents or to petition for citizenship and go through the process available to other non-Natives, even if they were of known partial Chickasaw descent in an earlier generation. Because the Chickasaw Nation did not provide citizenship to their Freedmen after the Civil War (it would have been akin to formal adoption of individuals into the tribe), they were penalized by the U.S. Government. It took more than half of their territory, with no compensation. They lost territory that had been negotiated in treaties in exchange for their use after removal from the Southeast.

Because the Chickasaw allied with the Confederacy, after the Civil War the United States government required the nation to make a new peace treaty in 1866. It included the provision that they emancipate the enslaved African Americans and provide full citizenship to those who wanted to stay in the Chickasaw Nation.

These people and their descendants became known as the Chickasaw Freedmen. Descendants of the Freedmen continue to live in Oklahoma. Today, the Choctaw-Chickasaw Freedmen Association of Oklahoma represents the interests of Freedmen descendants in both of these tribes.

But the Chickasaw Nation never granted citizenship to the Chickasaw Freedmen. The only way that African Americans could become citizens at that time was to have one or more Chickasaw parents or to petition for citizenship and go through the process available to other non-Natives, even if they were of known partial Chickasaw descent in an earlier generation. Because the Chickasaw Nation did not provide citizenship to their Freedmen after the Civil War (it would have been akin to formal adoption of individuals into the tribe), they were penalized by the U.S. Government. It took more than half of their territory, with no compensation. They lost territory that had been negotiated in treaties in exchange for their use after removal from the Southeast.

State-recognized groups

TheChaloklowa Chickasaw Indian People

The Chaloklowa Chickasaw Indian People or Chaloklowa Chickasaw is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization and "state-recognized group" not to be confused with a state-recognized tribe. The state of South Carolina gave them the state-recognized group a ...

, an organization that alleges to be composed of descendants of Chickasaw who did not leave the Southeast, were recognized as a "state-recognized group" in 2005 by South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

. They are headquartered in Hemingway, South Carolina. Historian Edward J. Cashin, a professor of colonial era history and Director of the Center for the Study of Georgia History at Augusta State University

Augusta State University was a public university in Augusta, Georgia. It merged with Georgia Health Sciences University in 2012 to form Georgia Regents University, later known as Augusta University.

History

Augusta State University was founded ...

, was unable to ascertain the organization's connection to the Savannah River Chickasaws or other bands of Chickasaw. After receiving letters of complaint concerning the Chaloklowa Chickasaw Indian People's later petition for recognition as a State Recognized tribe in October 2005, the Commission of Minority Affairs review committee, upon rereview, found that the indigenous ancestry originally being claimed by the group was incorrect. The organization remains recognized as a group as of 2023. In 2003, they unsuccessfully petitioned the US Department of the Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the management and conservation of most federal lands and natural resources. It also administers programs relating t ...

Bureau of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States List of United States federal agencies, federal agency within the U.S. Department of the Interior, Department of the Interior. It is responsible for im ...

to try to gain federal recognition as an Indian tribe.

Culture

For many tribes in the region, corn was one of the most important foods. TheGreen Corn Ceremony

The Green Corn Ceremony (Busk) is an annual ceremony practiced among various Native American peoples associated with the beginning of the yearly corn harvest. Busk is a term given to the ceremony by white traders, the word being a corruption of ...

, which occurs annually and starts when the corn crops begin to develop, usually in late June or early July, ties corn into the culture of the Chickasaw. This ceremony celebrated both the crop and the sense of community in the tribe. It was also a time of starting from scratch in a sense. Villages were cleaned, old pottery was broken, and most old fires were put out. Fasting was done by most tribes to obtain purity, and the Chickasaw specifically would fast from the afternoon of the first day of the ceremony until the second sunrise.

In 2010, the tribe opened the Chickasaw Cultural Center in Sulphur, Oklahoma

Sulphur is a city in and county seat of Murray County, Oklahoma, United States. The population was 5,065 at the 2020 census, a 2.8 percent gain over the figure of 4,929 in 2010. The area around Sulphur has been noted for its mineral springs, s ...

. It includes the ''Chikasha Inchokka’'' Traditional Village, Honor Garden, Sky and Water pavilion, and several in-depth exhibits about the diverse culture of the Chickasaw. The Chikasha Inchokka' Traditional Village features a Council House, two winter and summer houses, a replica mound, a corn crib and a stickball field. There are often stomp dances or stickball demonstrations, and cultural performers often display traditional Chickasaw culture, including art, cooking, language and storytelling.

To the Chickasaw, the Mississippi River helped "define their geographic homeland and history", and was important for trade, transportation, and irrigation. Referred to as "scored bluff waterway", Chickasaw warriors limited the movement of Europeans along the river.

Marriage traditions

Before marriage, a Chickasaw man would send a gift with his mother or sister to be given to the parents of the woman he would like to marry. If the parents consented, they would offer the gift to the woman. If the woman accepted, the family member of the man would return with the news of approval. The man would put on his finest clothing and applyvermilion

Vermilion (sometimes vermillion) is a color family and pigment most often used between antiquity and the 19th century from the powdered mineral cinnabar (a form of mercury sulfide). It is synonymous with red orange, which often takes a moder ...

, a paint associated with love, power, and purity. The man would go to the house of the woman he wanted to marry, and would have supper alone with his future father-in-law, without the company of the wife or mother-in-law. The bed of the wife would be prepared, and the bride would go to sleep before the groom joined. Once they were both in the same bed, they were officially married.

Religion

The Chickasaw people held ancient beliefs about four "Beloved Things": the sun, the clouds, the sky and Aba' Binni'li, also known as "He that lives in the clear sky". He was believed to be the sole creator of light, life, and warmth. He was believed to reside both in the clouds and in the holy fire, and due to this, fire was respected. It became unlawful to extinguish any fire, even a small cooking fire, with water, as this was considered to be the work of evil spirits. Bad weather such as rain, thunder and heavy wind was thought to be holy people at war above the clouds. Warriors would fire their guns at the sky to show that they were willing to die if they could aid the holy spirits above.Repatriation efforts

After they signed the treaty of Pontotoc Creek in 1832 and were forced from their native land in Mississippi, the Chickasaw tribe immigrated to its now-home in Oklahoma. While their current residence is far from their native territory, the ancestral remains of many Chickasaw members are still located in Mississippi, Tennessee, and Alabama. Among these remains, many were excavated and stored within the Mississippi Department of Archives and History (MDAH). In 2021 the MDAH repatriated 403 Chickasaw ancestors to the tribe. The organizations director of archaeology, Meg Cook, addressed the MDAH’s efforts: “We’re doing everything that we can to reconcile the past and move forward, in a very transparent way. It’s our responsibility to tell the Mississippi story. And that means all of the bad parts, too."Notable Chickasaw

*Bill Anoatubby

Billy Joe Anoatubby (born November 8, 1945) is the 32nd Governor of the Chickasaw Nation, a position he has held since 1987. From 1979 to 1987, Anoatubby served two terms as Lieutenant Governor of the Chickasaw Nation in the administration of Go ...

, Governor of the Chickasaw Nation

The Chickasaw Nation () is a federally recognized Indigenous nation with headquarters in Ada, Oklahoma, in the United States. The Chickasaw Nation descends from an Indigenous population historically located in the southeastern United States, in ...

since 1987

* Kaylea Arnett, professional sporting diver

* Jack Brisco

Freddie Joe "Jack" Brisco (September 21, 1941 – February 1, 2010) was an American amateur wrestler and professional wrestler. As an amateur for Oklahoma State, Brisco was two-time All-American and won the NCAA Division I national championship ...

and Jerry Brisco, pro wrestling tag team

* Jodi Byrd

Jodi Ann Byrd is an American Indigenous academic. They are an associate professor of Literatures in English at Cornell University, where they also hold an affiliation with the American Studies Program. Their research applies critical theory to ...

, Literary and political theorist

* Edwin Carewe

Edwin Carewe ( Chickasaw Nation, March 3, 1883 – January 22, 1940) was a Native American motion picture director, actor, producer, and screenwriter.

Early life and education

Jay John Fox was born on March 3, 1883, in Gainesville, Texas. H ...

(1883–1940), movie actor and director

* Charles David Carter, Democratic U. S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a bicameral legislature, including a lower body, the U.S. House of Representatives, and an upper body, the U.S. Senate. They both ...

man from Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Texas to the south and west, Kansas to the north, Missouri to the northea ...

* Levi Colbert

Levi Colbert (June 2, 1834) was an early 19th-century Chickasaw leader and the namesake of Itawamba County, Mississippi.

Early life and education

Levi Colbert was born around 1759 in the Chickasaw Nation (present-day Alabama). He was the ...

, Chickasaw language translator

* Tom Cole

Thomas Jeffery Cole (born April 28, 1949) is the U.S. representative for , serving since 2003. He is a member of the Republican Party and serves as the chairman of the House Appropriations Committee. Before serving in the House of Representati ...

, Republican U.S. Congressman from Oklahoma

* Molly Culver, actress

* Kent DuChaine, American Blues singer and guitarist

* Hiawatha Estes

Hiawatha Thompson Estes (January 26, 1918 – May 8, 2003) was a California-based architect, author, and founder of the Nationwide House Plan Book Company. He was best known for designing a large number of variations of the ubiquitous post-war ...

, architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs, and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

* Bee Ho Gray

Bee Ho Gray (born Emberry Cannon Gray; April 7, 1885, in Leon, Oklahoma, Leon, Chickasaw Nation, Indian Territory – August 3, 1951, in Pueblo, Colorado) was a Western performer who spent 50 years displaying his skills in Wild West shows, vaudevi ...

, actor

* John Herrington, astronaut

An astronaut (from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'star', and (), meaning 'sailor') is a person trained, equipped, and deployed by a List of human spaceflight programs, human spaceflight program to serve as a commander or crew member of a spa ...

; first Native American in space

* Linda Hogan, Writer-in-Residence of the Chickasaw Nation

* Miko Hughes, actor

* Sippia Paul Hull, early settler of Pauls Valley, Oklahoma

* Kyle Keller, Head Men's Basketball Coach, Stephen F. Austin Lumberjacks

* Neal A. McCaleb

Neal A. McCaleb (June 30, 1935 – January 7, 2025) was an American civil engineer and Republican Party (United States), Republican politician from Oklahoma. A member of the Chickasaw Nation, McCaleb served in several positions in the Government ...

, Assistant U.S. Secretary for Indian Affairs (overseeing the BIA) under George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician and businessman who was the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Bush family and the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he i ...

* Wahoo McDaniel, pro wrestler

Professional wrestling, often shortened to either pro wrestling or wrestling,The term "wrestling" is most often widely used to specifically refer to modern scripted professional wrestling, though it is also used to refer to real-life wrest ...

, American Football League

The American Football League (AFL) was a major professional American football league that operated for ten seasons from 1960 until 1970, AFL–NFL merger, when it merged with the older National Football League (NFL), and became the American Foot ...

player

* Leona Mitchell

Leona Pearl Mitchell (born October 13, 1949, Enid, Oklahoma) is an American operatic soprano who sang for 18 seasons as a leading spinto soprano at the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

In her home state of Oklahoma, she received many honors. The ...

, opera

Opera is a form of History of theatre#European theatre, Western theatre in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by Singing, singers. Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera") is typically ...

singer

* Rodd Redwing, actor

* Rebecca Sandefur

Rebecca Leigh Sandefur is an American sociologist. She is Professor in the School of Social and Family Dynamics at Arizona State University and a faculty fellow of the American Bar Foundation (ABF). At the ABF, she founded the access to justice ...

, Sociologist and MacArthur Fellow

The MacArthur Fellows Program, also known as the MacArthur Fellowship and colloquially called the "Genius Grant", is a prize awarded annually by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation to typically between 20 and 30 individuals workin ...

* Jerod Impichchaachaaha' Tate

Jerod Impichchaachaaha' Tate (born July 25, 1968) is a Chickasaw classical composer and pianist.composer

A composer is a person who writes music. The term is especially used to indicate composers of Western classical music, or those who are composers by occupation. Many composers are, or were, also skilled performers of music.

Etymology and def ...

and pianist

* Te Ata, traditional Indian storyteller and actress

* Fred Waite, cowboy and Chickasaw Nation statesman

* Kevin K. Washburn, Assistant U.S. Secretary for Indian Affairs under Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II (born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who was the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the first African American president in American history. O ...

* Montford Johnson, famous cattle rancher. In April 2020, Montford was inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. 5

* Stephanie Byers, Kansas State Legislator. In November of 2020, Stephanie Byers, a retired music educator, became the first transgender Native American elected to a state legislature anywhere in the United States.

Population history

The tribal traditions say that the Chickasaw once had 10,000 men fit for war. In 1687Louis Hennepin

Louis Hennepin, OFM (born Antoine Hennepin; ; 12 May 1626 – 5 December 1704) was a Belgian Catholic priest and missionary best known for his activities in North America. A member of the Recollects, a minor branch of the Franciscans, he travel ...

estimated the Chickasaw population as at least 4,000 warriors (and therefore at least 20,000 people). In 1702 according to Iberville there were ca. 2,000 Chickasaw families. Their number then decreased a lot during the 18th century and early 19th century, including the Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was the forced displacement of about 60,000 people of the " Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850, and the additional thousands of Native Americans and their black slaves within that were ethnically cleansed by the U ...

. Indian Affairs 1836 reported the number of the Chickasaw in year 1836 at around 5,400 people (another source says that the pre-removal population was 4,914 Chickasaws and 1,156 Black slaves). A report by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs dated 25 November 1841 says that around 4,600 Chickasaws already lived in Oklahoma (Indian Territory

Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United States, ...

) while around 400 stayed in the east. In 1875 the Office of Indian Affairs reported that there were around 6,000 Chickasaws. This figure of 6,000 continued to be reported in 1886 and in all subsequent reports until 1897. Indian Affairs 1910 reported that there were 5,688 Chickasaws by blood, 645 by intermarriage and 4,651 freedmen. While the census of 1910 counted only 4,204 Chickasaws.

Chickasaw population has rebounded in the 20th and 21st centuries. In 2020 they numbered 70,096 (including 32,579 in Oklahoma).

See also

*Chickasaw Nation

The Chickasaw Nation () is a federally recognized Indigenous nation with headquarters in Ada, Oklahoma, in the United States. The Chickasaw Nation descends from an Indigenous population historically located in the southeastern United States, in ...

* Chickasaw language

The Chickasaw language (, ) is a Native American language of the Muskogean family. It is agglutinative and follows the word order pattern of subject–object–verb (SOV). The language is closely related to, though perhaps not entirely mutuall ...

* List of sites and peoples visited by the Hernando de Soto Expedition

This is a list of sites and peoples visited by the Hernando de Soto Expedition in the years 1539–1543. In May 1539, de Soto left Havana, Cuba, with nine ships, over 620 men and 220 surviving horses and landed at Charlotte Harbor, Florida. Thi ...

* Chickasaw Wars

The Chickasaw Wars were fought in the first half of the 18th century between the Chickasaw allied with the British against the French and their allies the Choctaws, Quapaw, and Illinois Confederation. The Province of Louisiana extended from I ...

* Pashofa

Pashofa, or pishofa, is a Chickasaw and Choctaw soupy dish made from cracked white corn, also known as pearl hominy. The dish is one of the most important to the Chickasaw people and has been served at ceremonial and social events for centuries ...

* Perry Cohea

Footnotes

Further reading

* James F. Barnett, Jr., ''Mississippi's American Indians.'' Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2012. * Colin G. Calloway, ''The American Revolution in Indian Country.'' Cambridge University Press, 1995. * Daniel F. Littlefield, Jr., ''The Chickasaw Freedmen: A People Without a Country.'' Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1980. * * *External links

The Chickasaw Nation of Oklahoma

official site

Chickasaw.tv

The online video network of the Chickasaw Nation.

Chickasaw Nation Industries (government contracting arm of the Chickasaw Nation)

"Chickasaws: The Unconquerable People", a brief history by Greg O'Brien, Ph.D.

Pashofa recipe

Tanshpashofa recipe

Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture - Chickasaw

{{authority control Muskogean tribes Native American tribes in Alabama Native American tribes in Mississippi Native American tribes in Oklahoma South Appalachian Mississippian culture Native American people in the American Revolution