Cherokee People Eternal Flame on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the

indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands

Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands, Southeastern cultures, or Southeast Indians are an ethnographic classification for Native Americans who have traditionally inhabited the area now part of the Southeastern United States and the nor ...

of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, they were concentrated in their homelands, in towns along river valleys of what is now southwestern North Carolina, southeastern Tennessee, edges of western South Carolina, northern Georgia, and northeastern Alabama.

The Cherokee language

200px, Number of speakers

Cherokee or Tsalagi ( chr, ᏣᎳᎩ ᎦᏬᏂᎯᏍᏗ, ) is an endangered-to-moribund Iroquoian language and the native language of the Cherokee people. ''Ethnologue'' states that there were 1,520 Cherokee speaker ...

is part of the Iroquoian language group. In the 19th century, James Mooney

James Mooney (February 10, 1861 – December 22, 1921) was an American ethnographer who lived for several years among the Cherokee. Known as "The Indian Man", he conducted major studies of Southeastern Indians, as well as of tribes on the Gr ...

, an early American ethnographer, recorded one oral tradition that told of the tribe having migrated south in ancient times from the Great Lakes region, where other Iroquoian peoples have been based. However, anthropologist Thomas R. Whyte, writing in 2007, dated the split among the peoples as occurring earlier. He believes that the origin of the proto-Iroquoian language was likely the Appalachian region Appalachian may refer to:

* Appalachian Mountains, a major mountain range in eastern United States and Canada

* Appalachian Trail, a hiking trail in the eastern United States

* The people of Appalachia and their culture

** Appalachian Americans, e ...

, and the split between Northern and Southern Iroquoian languages began 4,000 years ago.

By the 19th century, White American settlers

A settler is a person who has migrated to an area and established a permanent residence there, often to colonize the area.

A settler who migrates to an area previously uninhabited or sparsely inhabited may be described as a pioneer.

Settle ...

had classified the Cherokee of the Southeast as one of the " Five Civilized Tribes" in the region. They were agrarian, lived in permanent villages, and had begun to adopt some cultural and technological practices of the white settlers. They also developed their own writing system.

Today, three Cherokee tribes are federally recognized: the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians (UKB) in Oklahoma, the Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee Nation (Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ ''Tsalagihi Ayeli'' or ᏣᎳᎩᏰᎵ ''Tsalagiyehli''), also known as the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, is the largest of three Cherokee federally recognized tribes in the United States. It ...

(CN) in Oklahoma, and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI) in North Carolina.

The Cherokee Nation has more than 300,000 tribal members, making it the largest of the 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States. In addition, numerous groups claim Cherokee lineage, and some of these are state-recognized. A total of more than 819,000 people are estimated to have identified as having Cherokee ancestry on the U.S. census; most are not enrolled members of any tribe.

Of the three federally recognized Cherokee tribes, the Cherokee Nation and the UKB have headquarters in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, and most of their members live in the state. The UKB are mostly descendants of "Old Settlers", also called Western Cherokee: those who migrated from the Southeast to Arkansas and Oklahoma about 1817 prior to Indian Removal

Indian removal was the United States government policy of forced displacement of self-governing tribes of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi Riverspecifically, to a de ...

. They are related to the Cherokee who were later forcibly relocated there in the 1830s under the Indian Removal Act. The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians is located on land known as the Qualla Boundary

The Qualla Boundary or The Qualla is territory held as a land trust by the United States government for the federally recognized Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, who reside in western North Carolina. The area is part of the large historic Chero ...

in western North Carolina. They are mostly descendants of ancestors who had resisted or avoided relocation, remaining in the area. Because they gave up tribal membership at the time, they became state and US citizens. In the late 19th century, they reorganized as a federally recognized tribe.

Name

A Cherokee language name for Cherokee people is Aniyvwiyaʔi (, also spelled Anigiduwagi), translating as "Principal People". ''Tsalagi'' () is the Cherokee word for theCherokee language

200px, Number of speakers

Cherokee or Tsalagi ( chr, ᏣᎳᎩ ᎦᏬᏂᎯᏍᏗ, ) is an endangered-to-moribund Iroquoian language and the native language of the Cherokee people. ''Ethnologue'' states that there were 1,520 Cherokee speaker ...

.

Many theories, though all unproven, abound about the origin of the name "Cherokee". It may have originally been derived from one of the competitive tribes in the area. For instance, the Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

word ''Cha-la-kee'' means "people who live in the mountains", and Choctaw ''Chi-luk-ik-bi'', means "people who live in the cave country". The Cherokee did live along rivers in mountainous areas.

The earliest Spanish transliteration of the name, from 1755, is recorded as ''Tchalaquei'', but it dates to accounts related to the Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1500 – 21 May, 1542) was a Spanish explorer and '' conquistador'' who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire ...

expedition in the mid-16th century. Another theory is that "Cherokee" derives from a Lower Creek

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern WoodlandsMartin and Mauldin, ''A Dictionary of Creek/Muskogee'', Sturtevant and Fogelson, p. 349.

The Iroquois Five Nations, historically based in New York and Pennsylvania, called the Cherokee ''Oyata'ge'ronoñ'' ("inhabitants of the cave country"). It is possible the word "Cherokee" comes from a Muscogee Creek word meaning “people of different speech”, because the two peoples spoke different languages.

Anthropologists and historians have two main theories of Cherokee origins. One is that the Cherokee, an Iroquoian-speaking people, are relative latecomers to Southern

Anthropologists and historians have two main theories of Cherokee origins. One is that the Cherokee, an Iroquoian-speaking people, are relative latecomers to Southern

. ''New Georgia Encyclopedia''. Retrieved July 22, 2010. In 1566, the Juan Pardo expedition traveled from the present-day South Carolina coast into its interior, and into western North Carolina and southeastern Tennessee. He recorded meeting Cherokee-speaking people who visited him while he stayed at the Joara chiefdom (north of present-day

The Cherokee gave sanctuary to a band of Shawnee in the 1660s. But from 1710 to 1715, the Cherokee and Chickasaw allied with the British, and fought the Shawnee, who were allied with French colonists, forcing the Shawnee to move northward.

The Cherokee fought with the Yamasee, Catawba, and British in late 1712 and early 1713 against the

The Cherokee gave sanctuary to a band of Shawnee in the 1660s. But from 1710 to 1715, the Cherokee and Chickasaw allied with the British, and fought the Shawnee, who were allied with French colonists, forcing the Shawnee to move northward.

The Cherokee fought with the Yamasee, Catawba, and British in late 1712 and early 1713 against the

"Eastern Cherokee Chiefs"

, ''Chronicles of Oklahoma'', Vol. 16, No. 1, March 1938. Retrieved September 21, 2009. Political power among the Cherokee remained decentralized, and towns acted autonomously. In 1735, the Cherokee were said to have sixty-four towns and villages, with an estimated fighting force of 6,000 men. In 1738 and 1739, smallpox epidemics broke out among the Cherokee, who had no natural immunity to the new infectious disease. Nearly half their population died within a year. Hundreds of other Cherokee committed British colonial officer

British colonial officer

In 1819, the Cherokee began holding council meetings at New Town, at the headwaters of the Oostanaula (near present-day Calhoun, Georgia). In November 1825, New Town became the capital of the Cherokee Nation, and was renamed New Echota, after the Overhill Cherokee principal town of Chota. Sequoyah's syllabary was adopted. They had developed a police force, a judicial system, and a National Committee.

In 1827, the Cherokee Nation drafted a Constitution modeled on the United States, with executive, legislative and judicial branches and a system of checks and balances. The two-tiered legislature was led by Major Ridge and his son

In 1819, the Cherokee began holding council meetings at New Town, at the headwaters of the Oostanaula (near present-day Calhoun, Georgia). In November 1825, New Town became the capital of the Cherokee Nation, and was renamed New Echota, after the Overhill Cherokee principal town of Chota. Sequoyah's syllabary was adopted. They had developed a police force, a judicial system, and a National Committee.

In 1827, the Cherokee Nation drafted a Constitution modeled on the United States, with executive, legislative and judicial branches and a system of checks and balances. The two-tiered legislature was led by Major Ridge and his son

Before the final removal to present-day Oklahoma, many Cherokees relocated to present-day Arkansas, Missouri and Texas. Between 1775 and 1786 the Cherokee, along with people of other nations such as the

Before the final removal to present-day Oklahoma, many Cherokees relocated to present-day Arkansas, Missouri and Texas. Between 1775 and 1786 the Cherokee, along with people of other nations such as the

Following the War of 1812, and the concurrent

Following the War of 1812, and the concurrent

Tennessee Encyclopedia, online; accessed October 2019 During this time, Georgia focused on removing the Cherokee's neighbors, the

Origins

Anthropologists and historians have two main theories of Cherokee origins. One is that the Cherokee, an Iroquoian-speaking people, are relative latecomers to Southern

Anthropologists and historians have two main theories of Cherokee origins. One is that the Cherokee, an Iroquoian-speaking people, are relative latecomers to Southern Appalachia

Appalachia () is a cultural region in the Eastern United States that stretches from the Southern Tier of New York State to northern Alabama and Georgia. While the Appalachian Mountains stretch from Belle Isle in Newfoundland and Labrador, Ca ...

, who may have migrated in late prehistoric times from northern areas around the Great Lakes. This has been the traditional territory of the '' Haudenosaunee'' nations and other Iroquoian-speaking peoples. Another theory is that the Cherokee had been in the Southeast for thousands of years and that proto-Iroquoian developed here. Other Iroquoian-speaking tribes in the Southeast have been the Tuscarora people of the Carolinas, and the Meherrin and Nottaway of Virginia.

James Mooney in the late 19th century recorded conversations with elders who recounted an oral tradition of the Cherokee people migrating south from the Great Lakes region in ancient times. They occupied territories where earthwork platform mounds were built by peoples during the earlier Woodland and Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a Native Americans in the United States, Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern United States, Midwestern, Eastern United States, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from appr ...

periods.

For example, the people of the Connestee culture period are believed to be ancestors of the historic Cherokee and occupied what is now Western North Carolina in the Middle Woodland period, circa 200 to 600 CE. They are believed to have built what is called the Biltmore Mound, found in 1984 south of the Swannanoa River on the Biltmore Estate, which has numerous Native American sites.

Other ancestors of the Cherokee are considered to be part of the later Pisgah phase of South Appalachian Mississippian culture, a regional variation of the Mississippian culture that arose circa 1000 and lasted to 1500 CE. There is a consensus among most specialists in Southeast archeology and anthropology about these dates. But Finger says that ancestors of the Cherokee people lived in western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee for a far longer period of time. Additional mounds were built by peoples during this cultural phase. Typically in this region, towns had a single platform mound and served as a political center for smaller villages.

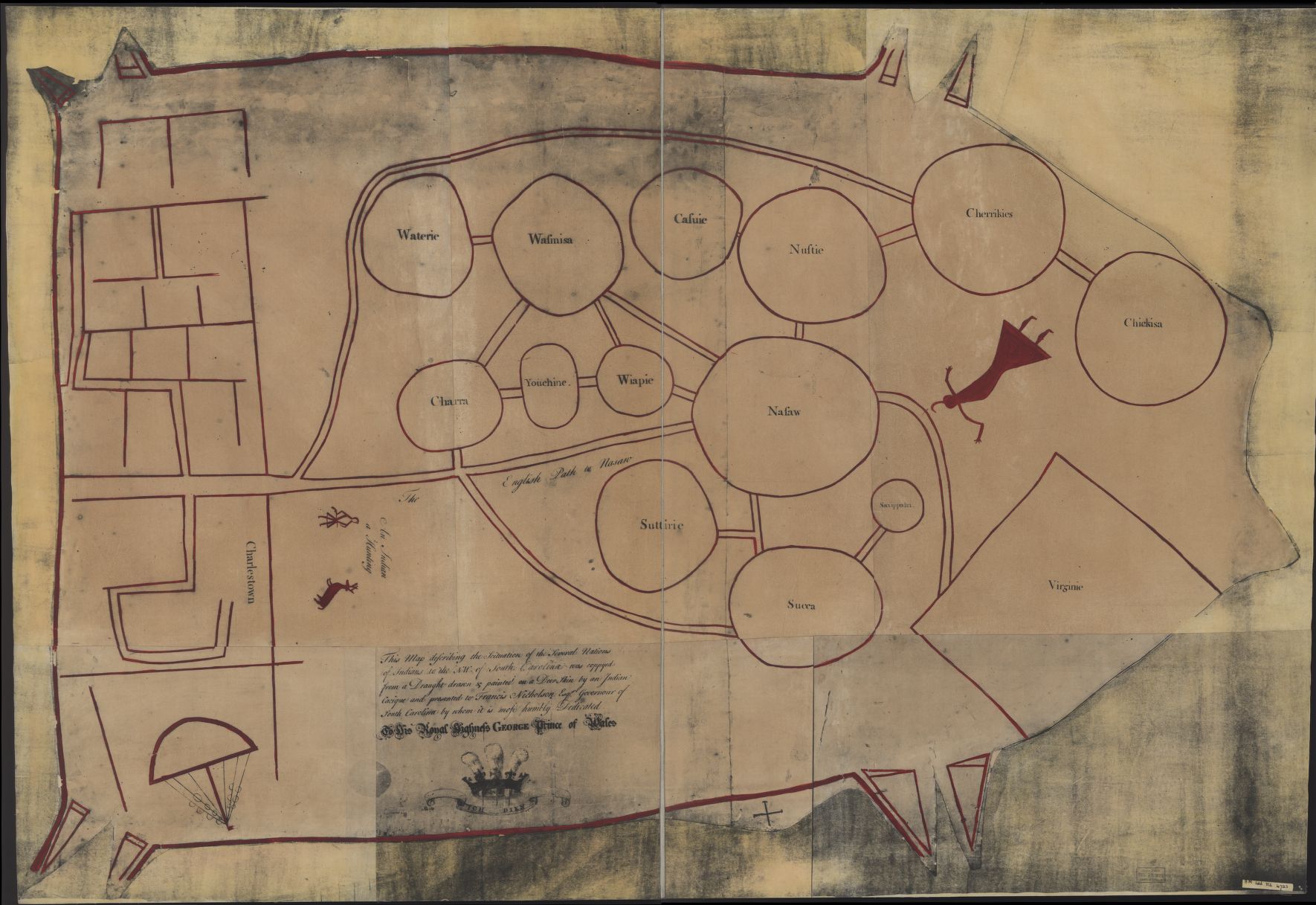

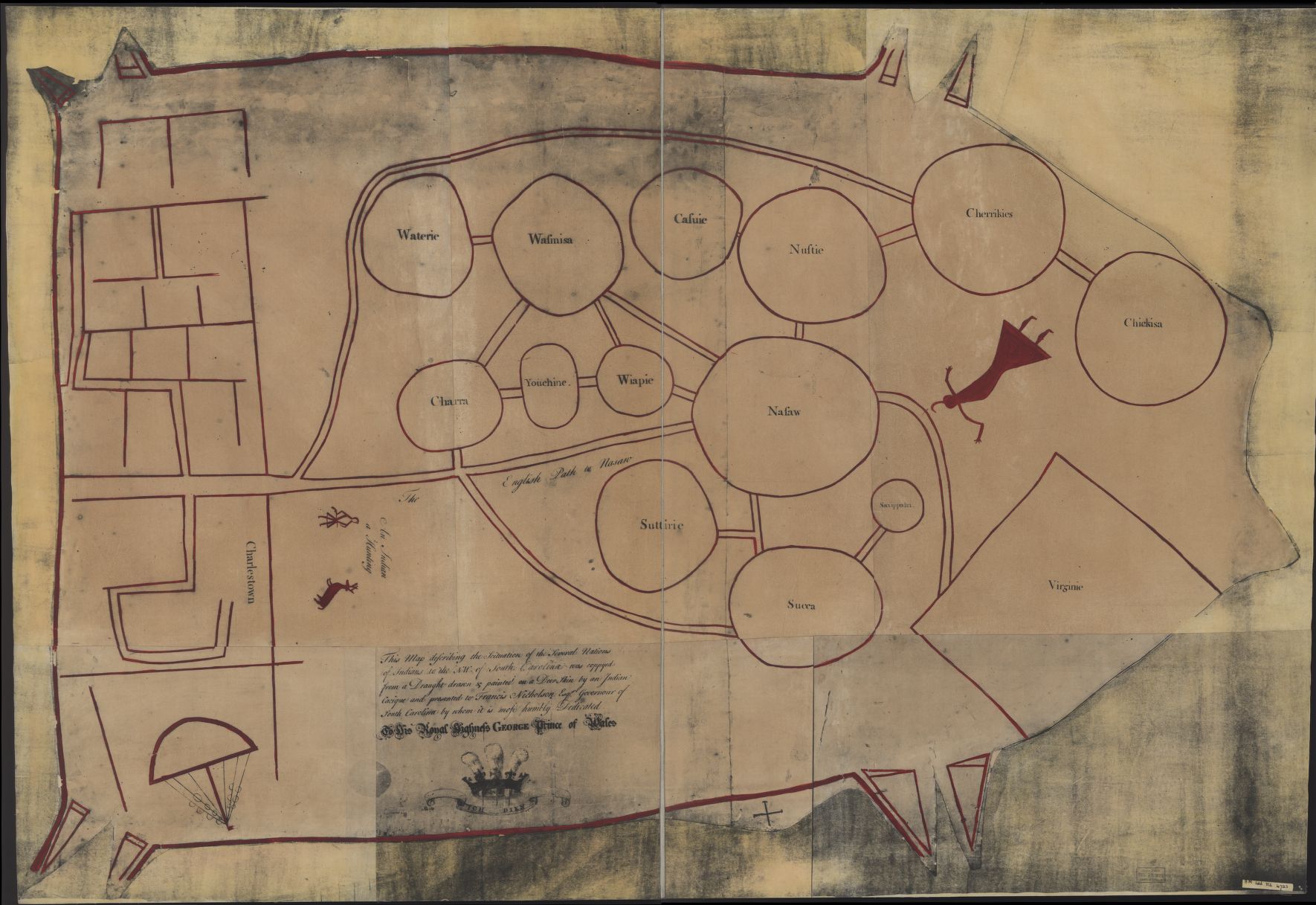

The homelands

The Cherokee occupied numerous towns throughout the river valleys and mountain ridges of their homelands. What were called the Lower towns were found in what is present-day western Oconee County, South Carolina, along the Keowee River (called the Savannah River in its lower portion). The principal town of the Lower Towns was Keowee. Other Cherokee towns on the Keowee River included Etastoe and Sugartown (''Kulsetsiyi''), a name repeated in other areas. In western North Carolina, what were known as the Valley, Middle, and Outer Towns were located along the major rivers of the Tuckasegee, the upper Little Tennessee, Hiwasee,French Broad

The French Broad River is a river in the U.S. states of North Carolina and Tennessee. It flows from near the town of Rosman in Transylvania County, North Carolina, into Tennessee, where its confluence with the Holston River at Knoxville forms ...

and other systems. The Overhill Cherokee occupied towns along the lower Little Tennessee River and upper Tennessee River on the western side of the Appalachian Mountains, in present-day southeastern Tennessee.

Agriculture

During the lateArchaic

Archaic is a period of time preceding a designated classical period, or something from an older period of time that is also not found or used currently:

*List of archaeological periods

**Archaic Sumerian language, spoken between 31st - 26th cent ...

and Woodland Period

In the classification of :category:Archaeological cultures of North America, archaeological cultures of North America, the Woodland period of North American pre-Columbian cultures spanned a period from roughly 1000 Common Era, BCE to European con ...

, Native Americans in the region began to cultivate plants such as marsh elder

''Iva'' is a genus of wind-pollinated plants in the family Asteraceae, described as a genus by Linnaeus in 1753. Plants of this genus are known generally as marsh elders. The genus is native to North America.

; Accepted species

* ''Iva angustifo ...

, lambsquarters, pigweed, sunflowers, and some native squash. People created new art forms such as shell gorget

Shell gorgets are a Native American art form of polished, carved shell pendants worn around the neck. The gorgets are frequently engraved, and are sometimes highlighted with pigments, or fenestrated (pierced with openings).

Shell gorgets were mos ...

s, adopted new technologies, and developed an elaborate cycle of religious ceremonies.

During the Mississippian culture-period (1000 to 1500 CE in the regional variation known as the South Appalachian Mississippian culture), local women developed a new variety of maize (corn) called eastern flint corn

Flint corn (''Zea mays'' var. ''indurata''; also known as Indian corn or sometimes calico corn) is a variant of maize, the same species as common corn. Because each kernel has a hard outer layer to protect the soft endosperm, it is likened to bei ...

. It closely resembled modern corn and produced larger crops. The successful cultivation of corn surpluses allowed the rise of larger, more complex chiefdoms consisting of several villages and concentrated populations during this period. Corn became celebrated among numerous peoples in religious ceremonies, especially the Green Corn Ceremony.

Early culture

Much of what is known about pre-18th century Native American cultures has come from records of Spanish expeditions. The earliest ones of the mid-16th century encountered peoples of theMississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a Native Americans in the United States, Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern United States, Midwestern, Eastern United States, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from appr ...

era, who were ancestral to tribes that emerged in the Southeast, such as the Cherokee, Muscogee, Cheraw

The Cheraw people, also known as the Saraw or Saura, were a Siouan-speaking tribe of indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, in the Piedmont area of North Carolina near the Sauratown Mountains, east of Pilot Mountain and north of the Yad ...

, and Catawba. Specifically in 1540-41, a Spanish expedition led by Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1500 – 21 May, 1542) was a Spanish explorer and '' conquistador'' who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire ...

passed through present-day South Carolina, proceeding into western North Carolina and what is considered Cherokee country. The Spanish recorded a ''Chalaque'' people as living around the Keowee River, where western North Carolina, South Carolina, and northeastern Georgia meet. The Cherokee consider this area to be part of their homelands, which also extended into southeastern Tennessee.

Further west, De Soto's expedition visited villages in present-day northwestern Georgia, recording them as ruled at the time by the Coosa chiefdom. This is believed to be a chiefdom ancestral to the Muscogee Creek people, who developed as a Muskogean-speaking people with a distinct culture."Late Prehistoric/Early Historic Chiefdoms (ca. A.D. 1300-1850)". ''New Georgia Encyclopedia''. Retrieved July 22, 2010. In 1566, the Juan Pardo expedition traveled from the present-day South Carolina coast into its interior, and into western North Carolina and southeastern Tennessee. He recorded meeting Cherokee-speaking people who visited him while he stayed at the Joara chiefdom (north of present-day

Morganton, North Carolina

Morganton is a city in and the county seat of Burke County, North Carolina, United States. The population was 16,918 at the 2010 census. Morganton is approximately northwest of Charlotte.

Morganton is one of the principal cities in the Hick ...

). The historic Catawba later lived in this area of the upper Catawba River. Pardo and his forces wintered over at Joara, building Fort San Juan there in 1567.

His expedition proceeded into the interior, noting villages near modern Asheville and other places that are part of the Cherokee homelands. According to anthropologist Charles M. Hudson, the Pardo expedition also recorded encounters with Muskogean-speaking peoples at Chiaha in southeastern modern Tennessee.

Linguistic studies

Linguistic studies have been another way for researchers to study the development of people and their cultures. Unlike most other Native American tribes in the American Southeast at the start of the historic era, the Cherokee and Tuscarora people spoke Iroquoian languages. Since the Great Lakes region was the territory of most Iroquoian-language speakers, scholars have theorized that both the Cherokee and Tuscarora migrated south from that region. The Cherokeeoral history

Oral history is the collection and study of historical information about individuals, families, important events, or everyday life using audiotapes, videotapes, or transcriptions of planned interviews. These interviews are conducted with people wh ...

tradition supports their migration from the Great Lakes.

Linguistic analysis shows a relatively large difference between Cherokee and the northern Iroquoian languages, suggesting they had migrated long ago. Scholars posit a split between the groups in the distant past, perhaps 3,500–3,800 years ago. Glottochronology Glottochronology (from Attic Greek γλῶττα ''tongue, language'' and χρόνος ''time'') is the part of lexicostatistics which involves comparative linguistics and deals with the chronological relationship between languages.Sheila Embleton ( ...

studies suggest the split occurred between about 1500 and 1800 BCE. The Cherokee say that the ancient settlement of '' Kituwa'' on the Tuckasegee River is their original settlement in the Southeast. It was formerly adjacent to and is now part of Qualla Boundary

The Qualla Boundary or The Qualla is territory held as a land trust by the United States government for the federally recognized Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, who reside in western North Carolina. The area is part of the large historic Chero ...

(the base of the federally recognized Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians) in North Carolina.

According to Thomas Whyte, who posits that proto-Iroquoian developed in Appalachia, the Cherokee and Tuscarora Tuscarora may refer to the following:

First nations and Native American people and culture

* Tuscarora people

**''Federal Power Commission v. Tuscarora Indian Nation'' (1960)

* Tuscarora language, an Iroquoian language of the Tuscarora people

* ...

broke off in the Southeast from the major group of Iroquoian speakers who migrated north to the Great Lakes area. There a succession of Iroquoian-speaking tribes were encountered by Europeans in historic times.

Other sources of early Cherokee history

In the 1830s, the American writer John Howard Payne visited Cherokee then based in Georgia. He recounted what they shared about pre-19th-century Cherokee culture and society. For instance, the Payne papers describe the account by Cherokee elders of a traditional two-part societal structure. A "white" organization of elders represented the sevenclan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clans may claim descent from founding member or apical ancestor. Clans, in indigenous societies, tend to be endogamous, meaning ...

s. As Payne recounted, this group, which was hereditary

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic inform ...

and priestly, was responsible for religious activities, such as healing, purification, and prayer. A second group of younger men, the "red" organization, was responsible for warfare. The Cherokee considered warfare a polluting activity. After warfare, the warriors required purification by the priestly class before participants could reintegrate into normal village life. This hierarchy had disappeared long before the 18th century.

Researchers have debated the reasons for the change. Some historians believe the decline in priestly power originated with a revolt by the Cherokee against the abuses of the priestly class known as the '' Ani-kutani''.Irwin 1992. Ethnographer James Mooney

James Mooney (February 10, 1861 – December 22, 1921) was an American ethnographer who lived for several years among the Cherokee. Known as "The Indian Man", he conducted major studies of Southeastern Indians, as well as of tribes on the Gr ...

, who studied and talked with the Cherokee in the late 1880s, was the first to trace the decline of the former hierarchy to this revolt. By the time that Mooney was studying the people in the late 1880s, the structure of Cherokee religious practitioners was more informal, based more on individual knowledge and ability than upon heredity.

Another major source of early cultural history comes from materials written in the 19th century by the ''didanvwisgi'' (), Cherokee medicine men, after Sequoyah

Sequoyah (Cherokee language, Cherokee: ᏍᏏᏉᏯ, ''Ssiquoya'', or ᏎᏉᏯ, ''Se-quo-ya''; 1770 – August 1843), also known as George Gist or George Guess, was a Native Americans in the United States, Native American polymath of the Ch ...

's creation of the Cherokee syllabary in the 1820s. Initially only the ''didanvwisgi'' learned to write and read such materials, which were considered extremely powerful in a spiritual sense. Later, the syllabary and writings were widely adopted by the Cherokee people.

History

17th century: English contact

In 1657, there was a disturbance in Virginia Colony as the ''Rechahecrians'' or ''Rickahockans'', as well as the Siouan '' Manahoac'' and ''Nahyssan

The Tutelo (also Totero, Totteroy, Tutera; Yesan in Tutelo) were Native American people living above the Fall Line in present-day Virginia and West Virginia. They spoke a Siouan dialect of the Tutelo language thought to be similar to that of thei ...

'', broke through the frontier and settled near the Falls of the James River, near present-day Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

. The following year, a combined force of English colonists and Pamunkey

The Pamunkey Indian Tribe is one of 11 Virginia Indian tribal governments recognized by the Commonwealth of Virginia, and the state's first federally recognized tribe, receiving its status in January 2016. Six other Virginia tribal governments, t ...

drove the newcomers away. The identity of the ''Rechahecrians'' has been much debated. Historians noted the name closely resembled that recorded for the ''Eriechronon'' or ''Erielhonan'', commonly known as the Erie tribe

The Erie people (also Eriechronon, Riquéronon, Erielhonan, Eriez, Nation du Chat) were Indigenous people historically living on the south shore of Lake Erie. An Iroquoian group, they lived in what is now western New York, northwestern Pennsylvani ...

, another Iroquoian-speaking people based south of the Great Lakes in present-day northern Pennsylvania. This Iroquoian people had been driven away from the southern shore of Lake Erie in 1654 by the powerful Iroquois Five Nations, also known as '' Haudenosaunee'', who were seeking more hunting grounds to support their dominance in the beaver fur trade. The anthropologist

An anthropologist is a person engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropology is the study of aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms and ...

Martin Smith theorized some remnants of the tribe migrated to Virginia after the wars ( 1986:131–32), later becoming known as the Westo to English colonists in the Province of Carolina. A few historians suggest this tribe was Cherokee.

Virginian traders developed a small-scale trading system with the Cherokee in the Piedmont before the end of the 17th century. The earliest recorded Virginia trader to live among the Cherokee was Cornelius Dougherty or Dority, in 1690.

18th century

The Cherokee gave sanctuary to a band of Shawnee in the 1660s. But from 1710 to 1715, the Cherokee and Chickasaw allied with the British, and fought the Shawnee, who were allied with French colonists, forcing the Shawnee to move northward.

The Cherokee fought with the Yamasee, Catawba, and British in late 1712 and early 1713 against the

The Cherokee gave sanctuary to a band of Shawnee in the 1660s. But from 1710 to 1715, the Cherokee and Chickasaw allied with the British, and fought the Shawnee, who were allied with French colonists, forcing the Shawnee to move northward.

The Cherokee fought with the Yamasee, Catawba, and British in late 1712 and early 1713 against the Tuscarora Tuscarora may refer to the following:

First nations and Native American people and culture

* Tuscarora people

**''Federal Power Commission v. Tuscarora Indian Nation'' (1960)

* Tuscarora language, an Iroquoian language of the Tuscarora people

* ...

in the Second Tuscarora War. The Tuscarora War marked the beginning of a British-Cherokee relationship that, despite breaking down on occasion, remained strong for much of the 18th century. With the growth of the deerskin trade

__NOTOC__

The deerskin trade between Colonial America and the Native Americans was one of the most important trading relationships between Europeans and Native Americans, especially in the southeast. It was a form of the fur trade, but less know ...

, the Cherokee were considered valuable trading partners, since deer skins from the cooler country of their mountain hunting-grounds were of better quality than those supplied by the lowland coastal tribes, who were neighbors of the English colonists.

In January 1716, Cherokee murdered a delegation of Muscogee Creek leaders at the town of Tugaloo, marking their entry into the Yamasee War

The Yamasee War (also spelled Yamassee or Yemassee) was a conflict fought in South Carolina from 1715 to 1717 between British settlers from the Province of Carolina and the Yamasee and a number of other allied Native American peoples, incl ...

. It ended in 1717 with peace treaties between the colony of South Carolina and the Creek. Hostility and sporadic raids between the Cherokee and Creek continued for decades. These raids came to a head at the Battle of Taliwa in 1755, at present-day Ball Ground, Georgia, with the defeat of the Muscogee.

In 1721, the Cherokee ceded lands in South Carolina. In 1730, at Nikwasi

Nikwasi ( chr, ᏁᏆᏏ, translit=Nequasi or Nequasee) comes from the Cherokee word for "star", ''Noquisi'' (No-kwee-shee), and is the site of the Cherokee town which is first found in colonial records in the early 18th century, but is much older ...

, a Cherokee town and Mississippian culture site, a Scots adventurer, Sir Alexander Cuming

Sir Alexander Cuming, 2nd Baronet (1691–1775) was a Scottish adventurer to North America; he returned to Britain with a delegation of Cherokee chiefs. He later spent many years in a debtors' prison.

Early life

Cuming was born (according to his ...

, crowned Moytoy of Tellico as "Emperor" of the Cherokee. Moytoy agreed to recognize King George II of Great Britain as the Cherokee protector. Cuming arranged to take seven prominent Cherokee, including '' Attakullakulla'', to London, England. There the Cherokee delegation signed the Treaty of Whitehall

The Treaty of Whitehall (or the Treaty of American Neutrality) was signed between Louis XIV of France and James II of England on 26 November 1686 (16 November O.S.). John Mack Faragher, ''A Great and Noble Scheme: The Tragic Story of the Expulsion ...

with the British. Moytoy's son, Amo-sgasite (Dreadful Water), attempted to succeed him as "Emperor" in 1741, but the Cherokee elected their own leader, Conocotocko (Old Hop) of Chota.Brown, John P"Eastern Cherokee Chiefs"

, ''Chronicles of Oklahoma'', Vol. 16, No. 1, March 1938. Retrieved September 21, 2009. Political power among the Cherokee remained decentralized, and towns acted autonomously. In 1735, the Cherokee were said to have sixty-four towns and villages, with an estimated fighting force of 6,000 men. In 1738 and 1739, smallpox epidemics broke out among the Cherokee, who had no natural immunity to the new infectious disease. Nearly half their population died within a year. Hundreds of other Cherokee committed

suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and s ...

due to their losses and disfigurement from the disease.

British colonial officer

British colonial officer Henry Timberlake

Henry Timberlake (1730 or 1735 – September 30, 1765) was a colonial Anglo-American officer, journalist, and cartographer. He was born in the Colony of Virginia and died in England. He is best known for his work as an emissary from the British ...

, born in Virginia, described the Cherokee people as he saw them in 1761:

From 1753 to 1755, battles broke out between the Cherokee and Muscogee over disputed hunting grounds in North Georgia. The Cherokee were victorious in the Battle of Taliwa. British soldiers built forts in Cherokee country to defend against the French in the Seven Years' War, which was fought across Europe and was called the French and Indian War on the North American front. These included Fort Loudoun near Chota on the Tennessee River in eastern Tennessee. Serious misunderstandings arose quickly between the two allies, resulting in the 1760 Anglo-Cherokee War.Rozema, pp. 17–23.

King George III's Royal Proclamation of 1763 forbade British settlements west of the Appalachian crest, as his government tried to afford some protection from colonial encroachment to the Cherokee and other tribes they depended on as allies. The Crown found the ruling difficult to enforce with colonists.

From 1771 to 1772, North Carolinian settlers squatted on Cherokee lands in Tennessee, forming the Watauga Association. Daniel Boone and his party tried to settle in Kentucky, but the Shawnee, Delaware, Mingo

The Mingo people are an Iroquoian group of Native Americans, primarily Seneca and Cayuga, who migrated west from New York to the Ohio Country in the mid-18th century, and their descendants. Some Susquehannock survivors also joined them, and ...

, and some Cherokee attacked a scouting and forage party that included Boone's son. The American Indians used this territory as a hunting ground by right of conquest; it had hardly been inhabited for years. The conflict in Kentucky sparked the beginning of what was known as Dunmore's War (1773–1774).

In 1776, allied with the Shawnee led by Cornstalk, Cherokee attacked settlers in South Carolina, Georgia, Virginia, and North Carolina in the Second Cherokee War. Overhill Cherokee Nancy Ward, Dragging Canoe's cousin, warned settlers of impending attacks. Provincial militias retaliated, destroying more than 50 Cherokee towns. North Carolina militia in 1776 and 1780 invaded and destroyed the Overhill towns in what is now Tennessee. In 1777, surviving Cherokee town leaders signed treaties with the new states.

Dragging Canoe and his band settled along Chickamauga Creek near present-day Chattanooga, Tennessee, where they established 11 new towns. Chickamauga Town Chickamauga may refer to:

Entertainment

* "Chickamauga", an 1889 short story by American author Ambrose Bierce

* "Chickamauga", a 1937 short story by Thomas Wolfe

* "Chickamauga", a song by Uncle Tupelo from their 1993 album ''Anodyne''

* ''Chick ...

was his headquarters and the colonists tended to call his entire band the Chickamauga to distinguish them from other Cherokee. From here he fought a guerrilla war against settlers, which lasted from 1776 to 1794. These are known informally as the Cherokee–American wars, but this is not a historian's term.

The first Treaty of Tellico Blockhouse, signed November 7, 1794, finally brought peace between the Cherokee and Americans, who had achieved independence from the British Crown. In 1805, the Cherokee ceded their lands between the Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. From 19 ...

and Duck rivers (i.e. the Cumberland Plateau

The Cumberland Plateau is the southern part of the Appalachian Plateau in the Appalachian Mountains of the United States. It includes much of eastern Kentucky and Tennessee, and portions of northern Alabama and northwest Georgia. The terms "Alle ...

) to Tennessee.

Scots (and other Europeans) among the Cherokee in the 18th century

The traders and British government agents dealing with the southern tribes in general, and the Cherokee in particular, were nearly all of Scottish ancestry, with many documented as being from the Highlands. A few were Scots-Irish, English, French, and German (seeScottish Indian trade

The trans-Atlantic trade in deerskins was a significant commercial activity in Colonial America that was greatly influenced, and at least partially dominated, by Scottish traders and their firms. This trade, primarily in deerskins but also in ...

). Many of these men married women from their host peoples and remained after the fighting had ended. Some of their mixed-race children, who were raised in Native American cultures, later became significant leaders among the Five Civilized Tribes of the Southeast.

Notable traders, agents, and refugee Tories among the Cherokee included John Stuart, Henry Stuart, Alexander Cameron, John McDonald, John Joseph Vann (father of James Vann

James Vann (c. 1762–64 – February 19, 1809) was an influential Cherokee leader, one of the triumvirate with Major Ridge and Charles R. Hicks, who led the Upper Towns of East Tennessee and North Georgia as part of the ᎤᏪᏘ ᏣᎳᎩ Ꭰ ...

), Daniel Ross (father of John Ross), John Walker Sr., John McLemore (father of Bob), William Buchanan, John Watts (father of John Watts Jr.), John D. Chisholm, John Benge (father of Bob Benge), Thomas Brown, John Rogers (Welsh), John Gunter (German, founder of Gunter's Landing), James Adair James Adair may refer to:

* James Makittrick Adair (1728–1802), Scottish doctor practising in Antigua

*James Adair (historian) (1709–1783), Irish historian of the American Indians

* James Adair (serjeant-at-law) (c. 1743–1798), English Whig M ...

(Irish), William Thorpe (English), and Peter Hildebrand (German), among many others. Some attained the honorary status of minor chiefs and/or members of significant delegations.

By contrast, a large portion of the settlers encroaching on the Native American territories were Scots-Irish, Irish from Ulster who were of Scottish descent and had been part of the plantation of Ulster

The Plantation of Ulster ( gle, Plandáil Uladh; Ulster-Scots: ''Plantin o Ulstèr'') was the organised colonisation (''plantation'') of Ulstera province of Irelandby people from Great Britain during the reign of King James I. Most of the sett ...

. They also tended to support the Revolution. But in the back country, there were also Scots-Irish who were Loyalists, such as Simon Girty.

19th century

Acculturation

The Cherokee lands between the Tennessee andChattahoochee

The Chattahoochee River forms the southern half of the Alabama and Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia border, as well as a portion of the Florida - Georgia border. It is a tributary of the Apalachicola River, a relatively short river formed by the con ...

rivers were remote enough from white settlers to remain independent after the Cherokee–American wars. The deerskin trade

__NOTOC__

The deerskin trade between Colonial America and the Native Americans was one of the most important trading relationships between Europeans and Native Americans, especially in the southeast. It was a form of the fur trade, but less know ...

was no longer feasible on their greatly reduced lands, and over the next several decades, the people of the fledgling Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee Nation (Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ ''Tsalagihi Ayeli'' or ᏣᎳᎩᏰᎵ ''Tsalagiyehli''), also known as the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, is the largest of three Cherokee federally recognized tribes in the United States. It ...

began to build a new society modeled on the white Southern United States.

George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

sought to 'civilize' Southeastern American Indians, through programs overseen by the Indian Agent Benjamin Hawkins

Benjamin Hawkins (August 15, 1754June 6, 1816) was an American planter, statesman and a U.S. Indian agent He was a delegate to the Continental Congress and a United States Senator from North Carolina, having grown up among the planter elite. ...

. He encouraged the Cherokee to abandon their communal land-tenure and settle on individual farmsteads, which was facilitated by the destruction of many American Indian towns during the American Revolutionary War. The deerskin trade

__NOTOC__

The deerskin trade between Colonial America and the Native Americans was one of the most important trading relationships between Europeans and Native Americans, especially in the southeast. It was a form of the fur trade, but less know ...

brought white-tailed deer to the brink of extinction, and as pigs and cattle were introduced, they became the principal sources of meat. The government supplied the tribes with spinning wheels and cotton-seed, and men were taught to fence and plow the land, in contrast to their traditional division in which crop cultivation was woman's labor. Americans instructed the women in weaving. Eventually, Hawkins helped them set up smithies, gristmills and cotton plantations.

The Cherokee organized a national government under Principal Chiefs Little Turkey

Little Turkey (1758–1801) was First Beloved Man of the Cherokee people, becoming, in 1794, the first Principal Chief of the original Cherokee Nation.

Headman

Little Turkey, born in 1758, was elected First Beloved Man by the general council of ...

(1788–1801), Black Fox (1801–1811), and Pathkiller

Pathkiller, (died January 8, 1827) was a Cherokee warrior and Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation.

Warrior life

PathkillerPathkiller is a Cherokee rank or title—not a name. His original name is unknown. fought against the Overmountain Men ...

(1811–1827), all former warriors of Dragging Canoe. The 'Cherokee triumvirate' of James Vann

James Vann (c. 1762–64 – February 19, 1809) was an influential Cherokee leader, one of the triumvirate with Major Ridge and Charles R. Hicks, who led the Upper Towns of East Tennessee and North Georgia as part of the ᎤᏪᏘ ᏣᎳᎩ Ꭰ ...

and his protégés The Ridge and Charles R. Hicks

Charles Renatus Hicks (December 23, 1767 – January 20, 1827) (Cherokee) was one of the three most important leaders of his people in the early 19th century, together with James Vann and Major Ridge. The three men all had some European ancestry, ...

advocated acculturation, formal education, and modern methods of farming. In 1801 they invited Moravian missionaries from North Carolina to teach Christianity and the 'arts of civilized life.' The Moravians and later Congregationalist missionaries ran boarding schools, and a select few students were educated at the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions school in Connecticut.

In 1806 a Federal Road from Savannah, Georgia to Knoxville, Tennessee was built through Cherokee land. Chief James Vann

James Vann (c. 1762–64 – February 19, 1809) was an influential Cherokee leader, one of the triumvirate with Major Ridge and Charles R. Hicks, who led the Upper Towns of East Tennessee and North Georgia as part of the ᎤᏪᏘ ᏣᎳᎩ Ꭰ ...

opened a tavern, inn and ferry across the Chattahoochee

The Chattahoochee River forms the southern half of the Alabama and Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia border, as well as a portion of the Florida - Georgia border. It is a tributary of the Apalachicola River, a relatively short river formed by the con ...

and built a cotton-plantation on a spur of the road from Athens, Georgia to Nashville

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the seat of Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the most populous city in the state, 21st most-populous city in the U.S., and the ...

. His son 'Rich Joe' Vann developed the plantation to , cultivated by 150 slaves. He exported cotton to England, and owned a steamboat

A steamboat is a boat that is marine propulsion, propelled primarily by marine steam engine, steam power, typically driving propellers or Paddle steamer, paddlewheels. Steamboats sometimes use the ship prefix, prefix designation SS, S.S. or S/S ...

on the Tennessee River.

The Cherokee allied with the U.S. against the nativist and pro-British Red Stick faction of the Upper Creek in the Creek War

The Creek War (1813–1814), also known as the Red Stick War and the Creek Civil War, was a regional war between opposing Indigenous American Creek factions, European empires and the United States, taking place largely in modern-day Alabama ...

during the War of 1812. Cherokee warriors led by Major Ridge played a major role in General Andrew Jackson's victory at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend

The Battle of Horseshoe Bend (also known as ''Tohopeka'', ''Cholocco Litabixbee'', or ''The Horseshoe''), was fought during the War of 1812 in the Mississippi Territory, now central Alabama. On March 27, 1814, United States forces and Indian a ...

. Major Ridge moved his family to Rome, Georgia

Rome is the largest city in and the county seat of Floyd County, Georgia, United States. Located in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains, it is the principal city of the Rome, Georgia metropolitan area, Rome, Georgia, metropolitan statisti ...

, where he built a substantial house, developed a large plantation and ran a ferry on the Oostanaula River. Although he never learned English, he sent his son and nephews to New England to be educated in mission schools. His interpreter and protégé Chief John Ross, the descendant of several generations of Cherokee women and Scots fur-traders, built a plantation and operated a trading firm and a ferry at Ross' Landing ( Chattanooga, Tennessee). During this period, divisions arose between the acculturated elite and the great majority of Cherokee, who clung to traditional ways of life.

Around 1809 Sequoyah

Sequoyah (Cherokee language, Cherokee: ᏍᏏᏉᏯ, ''Ssiquoya'', or ᏎᏉᏯ, ''Se-quo-ya''; 1770 – August 1843), also known as George Gist or George Guess, was a Native Americans in the United States, Native American polymath of the Ch ...

began developing a written form of the Cherokee language. He spoke no English, but his experiences as a silversmith dealing regularly with white settlers, and as a warrior at Horseshoe Bend, convinced him the Cherokee needed to develop writing. In 1821, he introduced Cherokee syllabary, the first written syllabic form of an American Indian language outside of Central America. Initially, his innovation was opposed by both Cherokee traditionalists and white missionaries, who sought to encourage the use of English. When Sequoyah taught children to read and write with the syllabary, he reached the adults. By the 1820s, the Cherokee had a higher rate of literacy than the whites around them in Georgia.

In 1819, the Cherokee began holding council meetings at New Town, at the headwaters of the Oostanaula (near present-day Calhoun, Georgia). In November 1825, New Town became the capital of the Cherokee Nation, and was renamed New Echota, after the Overhill Cherokee principal town of Chota. Sequoyah's syllabary was adopted. They had developed a police force, a judicial system, and a National Committee.

In 1827, the Cherokee Nation drafted a Constitution modeled on the United States, with executive, legislative and judicial branches and a system of checks and balances. The two-tiered legislature was led by Major Ridge and his son

In 1819, the Cherokee began holding council meetings at New Town, at the headwaters of the Oostanaula (near present-day Calhoun, Georgia). In November 1825, New Town became the capital of the Cherokee Nation, and was renamed New Echota, after the Overhill Cherokee principal town of Chota. Sequoyah's syllabary was adopted. They had developed a police force, a judicial system, and a National Committee.

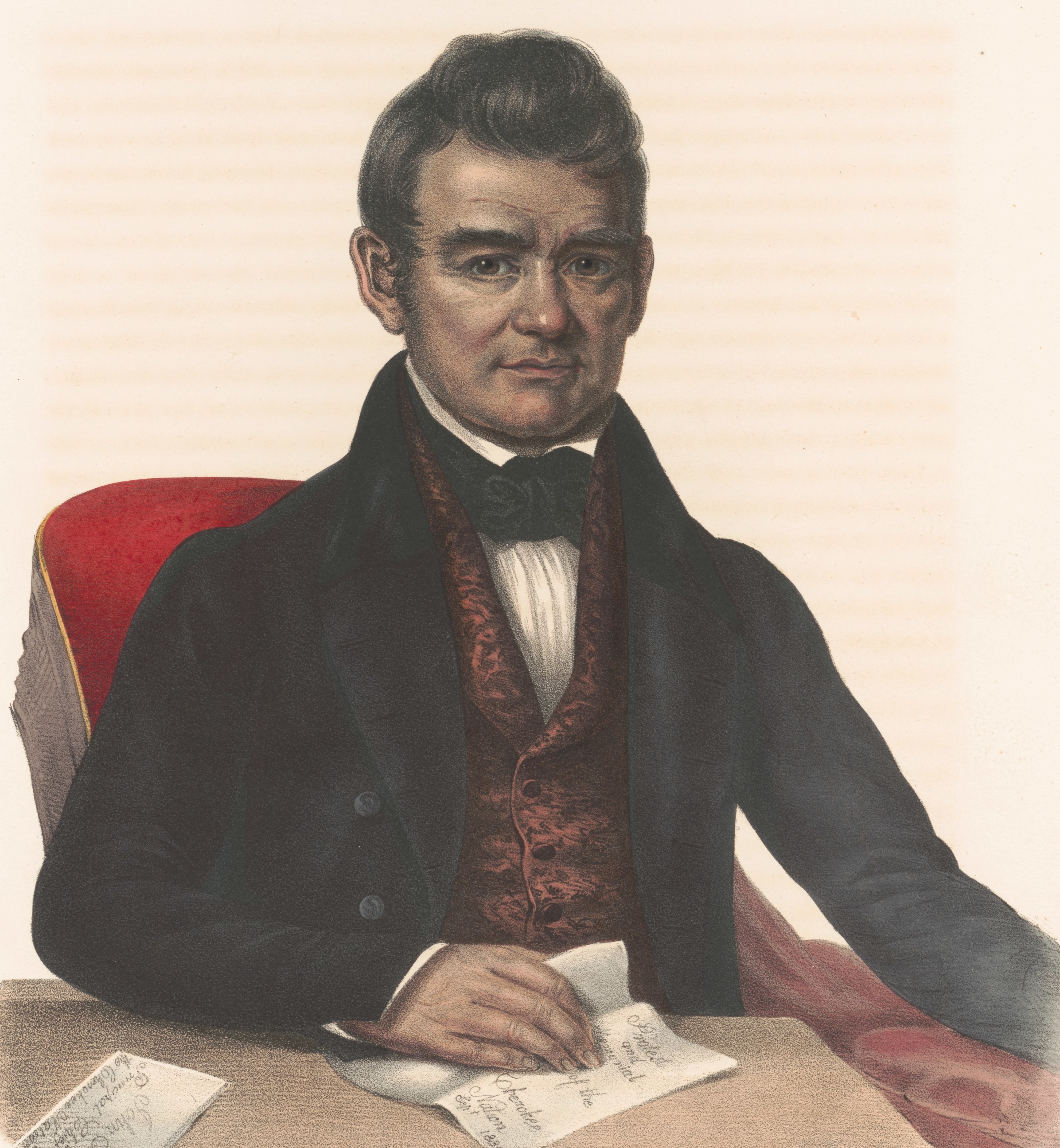

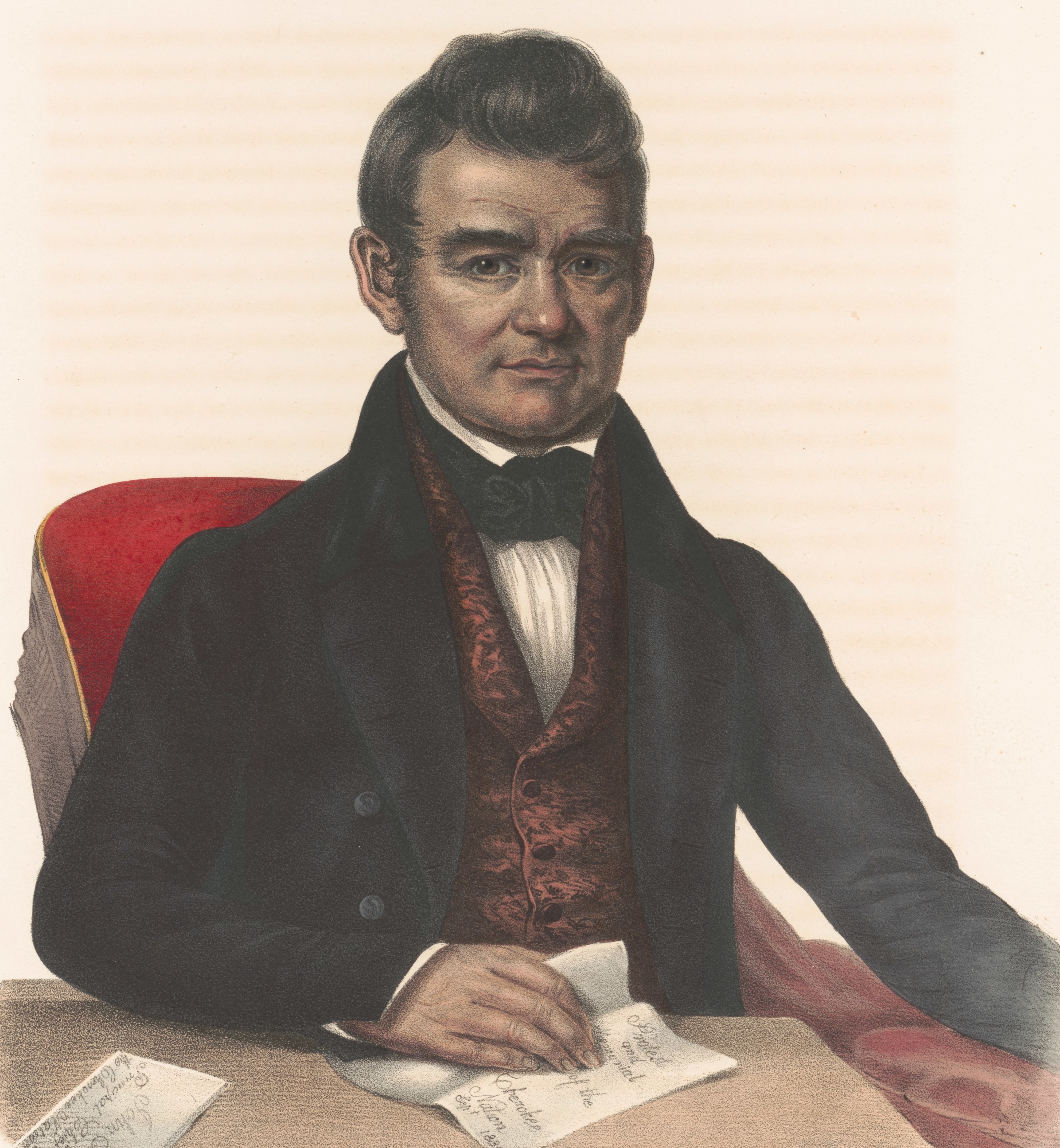

In 1827, the Cherokee Nation drafted a Constitution modeled on the United States, with executive, legislative and judicial branches and a system of checks and balances. The two-tiered legislature was led by Major Ridge and his son John Ridge

John Ridge, born ''Skah-tle-loh-skee'' (ᏍᎦᏞᎶᏍᎩ, Yellow Bird) ( – 22 June 1839), was from a prominent family of the Cherokee Nation, then located in present-day Georgia. He went to Cornwall, Connecticut, to study at the Foreign Mis ...

. Convinced the tribe's survival required English-speaking leaders who could negotiate with the U.S., the legislature appointed John Ross as Principal Chief. A printing press was established at New Echota by the Vermont missionary Samuel Worcester and Major Ridge's nephew Elias Boudinot, who had taken the name of his white benefactor, a leader of the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for thirteen of Britain's colonies in North America, and the newly declared United States just before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. ...

and New Jersey Congressman. They translated the Bible into Cherokee syllabary. Boudinot published the first edition of the bilingual ' Cherokee Phoenix,' the first American Indian newspaper, in February 1828.

Removal era

Before the final removal to present-day Oklahoma, many Cherokees relocated to present-day Arkansas, Missouri and Texas. Between 1775 and 1786 the Cherokee, along with people of other nations such as the

Before the final removal to present-day Oklahoma, many Cherokees relocated to present-day Arkansas, Missouri and Texas. Between 1775 and 1786 the Cherokee, along with people of other nations such as the Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

and Chickasaw, began voluntarily settling along the Arkansas and Red Rivers.

In 1802, the federal government promised to extinguish Indian titles to lands claimed by Georgia in return for Georgia's cession of the western lands that became Alabama and Mississippi. To convince the Cherokee to move voluntarily in 1815, the US government established a Cherokee Reservation in Arkansas. The reservation boundaries extended from north of the Arkansas River to the southern bank of the White River. Di'wali (The Bowl), Sequoyah

Sequoyah (Cherokee language, Cherokee: ᏍᏏᏉᏯ, ''Ssiquoya'', or ᏎᏉᏯ, ''Se-quo-ya''; 1770 – August 1843), also known as George Gist or George Guess, was a Native Americans in the United States, Native American polymath of the Ch ...

, Spring Frog and Tatsi (Dutch) and their bands settled there. These Cherokees became known as "Old Settlers."

The Cherokee, eventually, migrated as far north as the Missouri Bootheel by 1816. They lived interspersed among the Delawares

The Lenape (, , or Lenape , del, Lënapeyok) also called the Leni Lenape, Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada. Their historical territory includ ...

and Shawnees of that area. The Cherokee in Missouri Territory increased rapidly in population, from 1,000 to 6,000 over the next year (1816–1817), according to reports by Governor William Clark. Increased conflicts with the Osage Nation

The Osage Nation ( ) ( Osage: 𐓁𐒻 𐓂𐒼𐒰𐓇𐒼𐒰͘ ('), "People of the Middle Waters") is a Midwestern Native American tribe of the Great Plains. The tribe developed in the Ohio and Mississippi river valleys around 700 BC along ...

led to the Battle of Claremore Mound The Battle of Claremore Mound, also known as the Battle of the Strawberry Moon, or the Claremore Mound Massacre, was one of the chief battles of the war between the Osage and Cherokee Indians. It occurred in June 1817, when a band of Western Cherok ...

and the eventual establishment of Fort Smith between Cherokee and Osage communities. In the Treaty of St. Louis (1825)

The Treaty of St. Louis is the name of a series of treaties signed between the United States and various Native American tribes from 1804 through 1824. The fourteen treaties were all signed in the St. Louis, Missouri area.

The Treaty of St. Loui ...

, the Osage were made to "cede and relinquish to the United States, all their right, title, interest, and claim, to lands lying within the State of Missouri and Territory of Arkansas..." to make room for the Cherokee and the ''Mashcoux'', Muscogee Creeks. As late as the winter of 1838, Cherokee and Creek living in the Missouri and Arkansas areas petitioned the War Department to remove the Osage from the area.

A group of Cherokee traditionalists led by ''Di'wali'' moved to Spanish Texas in 1819. Settling near Nacogdoches, they were welcomed by Mexican authorities as potential allies against Anglo-American colonists. The Texas Cherokees

Texas Cherokees were the small settlements of Cherokee people who lived temporarily in what is now Texas, after being Trail of Tears, forcibly relocated from their homelands, primarily during the time that Spain, and then Mexico, controlled the ter ...

were mostly neutral during the Texas War of Independence. In 1836, they signed a treaty with Texas President Sam Houston

Samuel Houston (, ; March 2, 1793 – July 26, 1863) was an American general and statesman who played an important role in the Texas Revolution. He served as the first and third president of the Republic of Texas and was one of the first two i ...

, an adopted member of the Cherokee tribe. His successor Mirabeau Lamar sent militia to evict them in 1839.

=Trail of Tears

= Following the War of 1812, and the concurrent

Following the War of 1812, and the concurrent Red Stick War

The Creek War (1813–1814), also known as the Red Stick War and the Creek Civil War, was a regional war between opposing Indigenous American Creek factions, European empires and the United States, taking place largely in modern-day Alabama ...

, the U.S. government persuaded several groups of Cherokee to a voluntary removal to the Arkansaw Territory. These were the

" Old Settlers", the first of the Cherokee to make their way to what would eventually become Indian Territory (modern day Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw language, Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the nor ...

). This effort was headed by Indian Agent Return J. Meigs, and was finalized with the signing of the Jackson and McMinn Treaty

The Jackson and McMinn Treaty settled land disputes between The United States, the Cherokee Nation (1794–1907), Cherokee Nation, and other tribes following the early re-settlement of the Old Settlers of the Cherokee people to the Arkansas Terr ...

, giving the Old Settlers undisputed title to the lands designated for their use.''Treaties''Tennessee Encyclopedia, online; accessed October 2019 During this time, Georgia focused on removing the Cherokee's neighbors, the

Lower Creek

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern WoodlandsGeorge Troup and his cousin William McIntosh, chief of the Lower Creek, signed the Treaty of Indian Springs in 1825, ceding the last Muscogee (Creek) lands claimed by Georgia. The state's northwestern border reached the

Chattahoochee

The Chattahoochee River forms the southern half of the Alabama and Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia border, as well as a portion of the Florida - Georgia border. It is a tributary of the Apalachicola River, a relatively short river formed by the con ...

, the border of the Cherokee Nation. In 1829, gold was discovered at Dahlonega, on Cherokee land claimed by Georgia. The Georgia Gold Rush

The Georgia Gold Rush was the second significant gold rush in the United States and the first in Georgia, and overshadowed the previous rush in North Carolina. It started in 1829 in present-day Lumpkin County near the county seat, Dahlonega, and ...

was the first in U.S. history, and state officials demanded that the federal government expel the Cherokee. When Andrew Jackson was inaugurated as President in 1829, Georgia gained a strong ally in Washington. In 1830 Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, authorizing the forcible relocation of American Indians east of the Mississippi to a new Indian Territory.

Jackson claimed the removal policy was an effort to prevent the Cherokee from facing extinction as a people, which he considered the fate that "...the Mohegan, the Narragansett, and the Delaware" had suffered. There is, however, ample evidence that the Cherokee were adapting to modern farming techniques. A modern analysis shows that the area was in general in a state of economic surplus and could have accommodated both the Cherokee and new settlers.

The Cherokee brought their grievances to a US judicial review that set a precedent in Indian country. John Ross traveled to Washington, D.C., and won support from National Republican Party

The National Republican Party, also known as the Anti-Jacksonian Party or simply Republicans, was a political party in the United States that evolved from a conservative-leaning faction of the Democratic-Republican Party that supported John Qu ...

leaders Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. He was the seventh House speaker as well as the ninth secretary of state, al ...

and Daniel Webster. Samuel Worcester campaigned on behalf of the Cherokee in New England, where their cause was taken up by Ralph Waldo Emerson (see