Charles Darwin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English

Both families were largely Unitarian, though the Wedgwoods were adopting

Both families were largely Unitarian, though the Wedgwoods were adopting

. Darwin spent the summer of 1825 as an apprentice doctor, helping his father treat the poor of Shropshire, before going to the well-regarded

. In Darwin's second year at the university, he joined the

. In his final examination in January 1831, Darwin did well, coming tenth out of 178 candidates for the ''ordinary'' degree. Darwin had to stay at Cambridge until June 1831. He studied Paley's ''

After leaving Sedgwick in Wales, Darwin spent a few days with student friends at

After leaving Sedgwick in Wales, Darwin spent a few days with student friends at  Darwin experienced an earthquake in Chile in 1835 and saw signs that the land had just been raised, including

Darwin experienced an earthquake in Chile in 1835 and saw signs that the land had just been raised, including

He later wrote that such facts "seemed to me to throw some light on the origin of species". Without telling Darwin, extracts from his letters to Henslow had been read to scientific societies, printed as a pamphlet for private distribution among members of the

On 2 October 1836, ''Beagle'' anchored at Falmouth, Cornwall. Darwin promptly made the long coach journey to Shrewsbury to visit his home and see relatives. He then hurried to

On 2 October 1836, ''Beagle'' anchored at Falmouth, Cornwall. Darwin promptly made the long coach journey to Shrewsbury to visit his home and see relatives. He then hurried to  Early in March, Darwin moved to London to be near this work, joining Lyell's social circle of scientists and experts such as

Early in March, Darwin moved to London to be near this work, joining Lyell's social circle of scientists and experts such as

Fully recuperated, he returned to Shrewsbury in July 1838. Used to jotting down daily notes on animal breeding, he scrawled rambling thoughts about marriage, career and prospects on two scraps of paper, one with columns headed ''"Marry"'' and ''"Not Marry"''. Advantages under "Marry" included "constant companion and a friend in old age ... better than a dog anyhow", against points such as "less money for books" and "terrible loss of time". Having decided in favour of marriage, he discussed it with his father, then went to visit his cousin Emma on 29 July. At this time he did not get around to proposing, but against his father's advice, he mentioned his ideas on transmutation.

He married Emma on 29 January 1839 and they were the parents of ten children, seven of whom survived to adulthood.

Fully recuperated, he returned to Shrewsbury in July 1838. Used to jotting down daily notes on animal breeding, he scrawled rambling thoughts about marriage, career and prospects on two scraps of paper, one with columns headed ''"Marry"'' and ''"Not Marry"''. Advantages under "Marry" included "constant companion and a friend in old age ... better than a dog anyhow", against points such as "less money for books" and "terrible loss of time". Having decided in favour of marriage, he discussed it with his father, then went to visit his cousin Emma on 29 July. At this time he did not get around to proposing, but against his father's advice, he mentioned his ideas on transmutation.

He married Emma on 29 January 1839 and they were the parents of ten children, seven of whom survived to adulthood.

By July, Darwin had expanded his "sketch" into a 230-page "Essay", to be expanded with his research results if he died prematurely. In November, the anonymously published sensational best-seller ''

By July, Darwin had expanded his "sketch" into a 230-page "Essay", to be expanded with his research results if he died prematurely. In November, the anonymously published sensational best-seller ''

Though Darwin saw no threat, on 14 May 1856 he began writing a short paper. Finding answers to difficult questions held him up repeatedly, and he expanded his plans to a "big book on species" titled ''

He avoided explicit discussion of human origins, but implied the significance of his work with the sentence; "Light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history."

His theory is simply stated in the introduction: At the end of the book, he concluded that: The last word was the only variant of "evolved" in the first five editions of the book. "

Despite repeated bouts of illness during the last twenty-two years of his life, Darwin's work continued. Having published ''On the Origin of Species'' as an abstract of his theory, he pressed on with experiments, research, and writing of his " big book". He covered human descent from earlier animals, including the evolution of society and of mental abilities, as well as explaining decorative beauty in

Despite repeated bouts of illness during the last twenty-two years of his life, Darwin's work continued. Having published ''On the Origin of Species'' as an abstract of his theory, he pressed on with experiments, research, and writing of his " big book". He covered human descent from earlier animals, including the evolution of society and of mental abilities, as well as explaining decorative beauty in

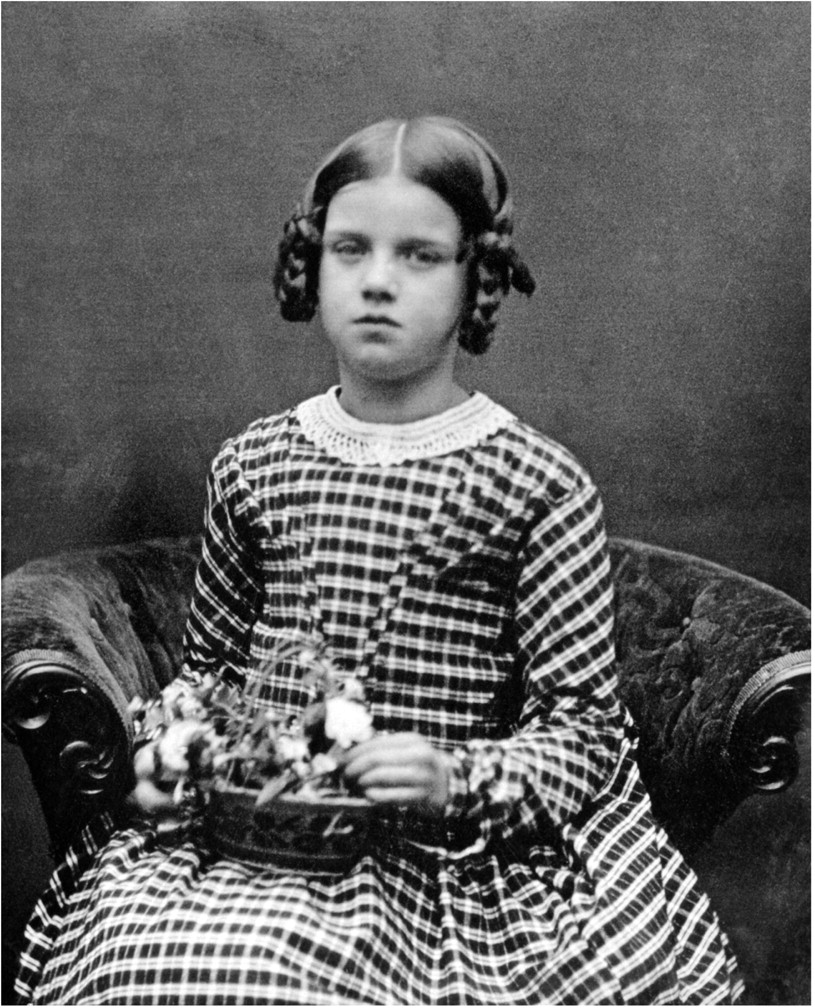

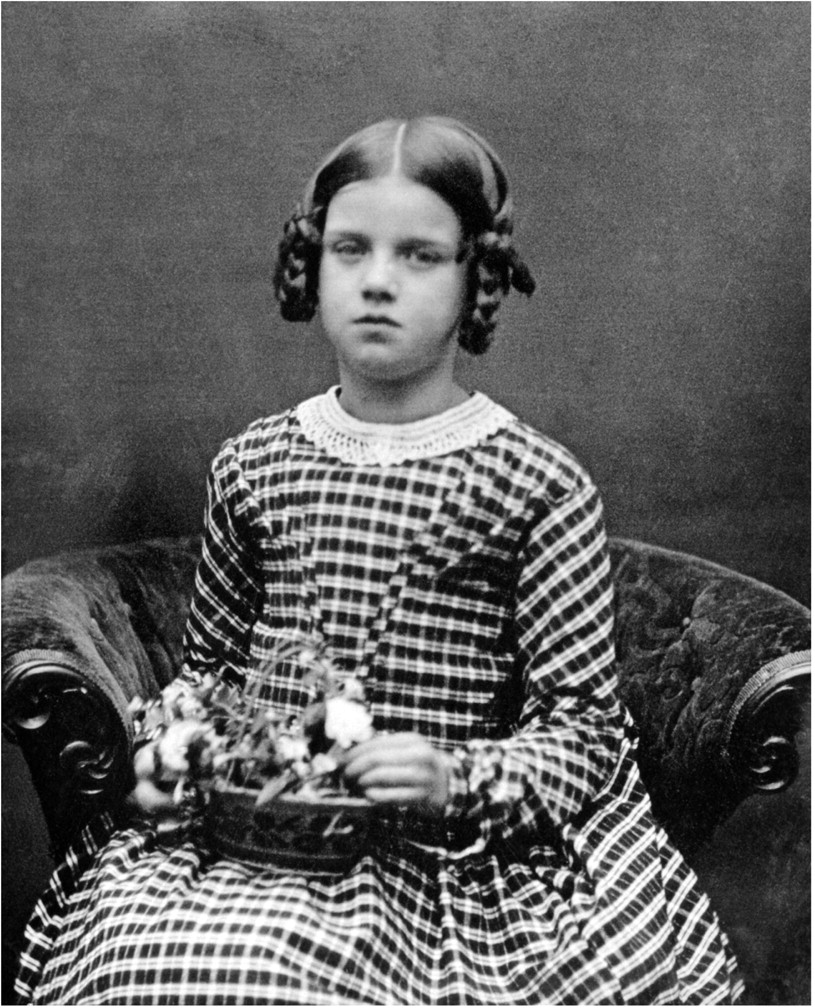

Charles Waring Darwin, born in December 1856, was the tenth and last of the children. Emma Darwin was aged 48 at the time of the birth, and the child was mentally subnormal and never learnt to walk or talk. He probably had Down syndrome, which had not then been medically described. The evidence is a photograph by William Erasmus Darwin of the infant and his mother, showing a characteristic head shape, and the family's observations of the child. Charles Waring died of scarlet fever on 28 June 1858, when Darwin wrote in his journal: "Poor dear Baby died."

Of his surviving children,

Charles Waring Darwin, born in December 1856, was the tenth and last of the children. Emma Darwin was aged 48 at the time of the birth, and the child was mentally subnormal and never learnt to walk or talk. He probably had Down syndrome, which had not then been medically described. The evidence is a photograph by William Erasmus Darwin of the infant and his mother, showing a characteristic head shape, and the family's observations of the child. Charles Waring died of scarlet fever on 28 June 1858, when Darwin wrote in his journal: "Poor dear Baby died."

Of his surviving children,

Upon his return, he expressed a critical view of the Bible's historical accuracy and questioned the basis for considering one religion more valid than another. In the next few years, while intensively speculating on geology and the transmutation of species, he gave much thought to religion and openly discussed this with his wife Emma, whose beliefs similarly came from intensive study and questioning.

The

Upon his return, he expressed a critical view of the Bible's historical accuracy and questioned the basis for considering one religion more valid than another. In the next few years, while intensively speculating on geology and the transmutation of species, he gave much thought to religion and openly discussed this with his wife Emma, whose beliefs similarly came from intensive study and questioning.

The

– Darwin, C. R. to Fordyce, John, 7 May 1879Darwin's Complex loss of Faith

but Darwin remained strongly against slavery, against "ranking the so-called races of man as distinct species", and against ill-treatment of native people. Darwin's interaction with Yaghans (Fuegians) such as Jemmy Button during the second voyage of HMS ''Beagle'' had a profound impact on his view of indigenous peoples. At his arrival in Tierra del Fuego he made a colourful description of "

Darwin's fame and popularity led to his name being associated with ideas and movements that, at times, had only an indirect relation to his writings, and sometimes went directly against his express comments.

Thomas Malthus had argued that population growth beyond resources was ordained by God to get humans to work productively and show restraint in getting families; this was used in the 1830s to justify

Darwin's fame and popularity led to his name being associated with ideas and movements that, at times, had only an indirect relation to his writings, and sometimes went directly against his express comments.

Thomas Malthus had argued that population growth beyond resources was ordained by God to get humans to work productively and show restraint in getting families; this was used in the 1830s to justify

Evolution was by then seen as having social implications, and After the 1880s, the eugenics movement developed on ideas of biological inheritance, and for scientific justification of their ideas appealed to some concepts of Darwinism. In Britain, most shared Darwin's cautious views on voluntary improvement and sought to encourage those with good traits in "positive eugenics". During the "Eclipse of Darwinism", a scientific foundation for eugenics was provided by

After the 1880s, the eugenics movement developed on ideas of biological inheritance, and for scientific justification of their ideas appealed to some concepts of Darwinism. In Britain, most shared Darwin's cautious views on voluntary improvement and sought to encourage those with good traits in "positive eugenics". During the "Eclipse of Darwinism", a scientific foundation for eugenics was provided by

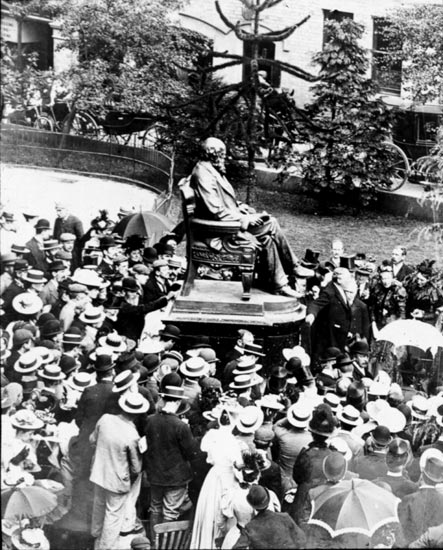

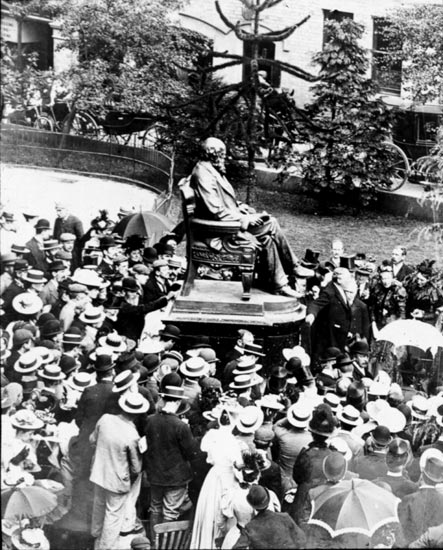

As Alfred Russel Wallace put it, Darwin had "wrought a greater revolution in human thought within a quarter of a century than any man of our timeor perhaps any time", having "given us a new conception of the world of life, and a theory which is itself a powerful instrument of research; has shown us how to combine into one consistent whole the facts accumulated by all the separate classes of workers, and has thereby revolutionised the whole study of nature". The paleoanthropologist

As Alfred Russel Wallace put it, Darwin had "wrought a greater revolution in human thought within a quarter of a century than any man of our timeor perhaps any time", having "given us a new conception of the world of life, and a theory which is itself a powerful instrument of research; has shown us how to combine into one consistent whole the facts accumulated by all the separate classes of workers, and has thereby revolutionised the whole study of nature". The paleoanthropologist

. During "

Charlotte Perkins Gilman and the Feminization of Education

' by Deborah M. De Simone: "Gilman shared many basic educational ideas with the generation of thinkers who matured during the period of "intellectual chaos" caused by Darwin's Origin of the Species. Marked by the belief that individuals can direct human and social evolution, many progressives came to view education as the panacea for advancing social progress and for solving such problems as urbanisation, poverty, or immigration." . See, for example, the song "A lady fair of lineage high" from

( ) .

Darwin Online

Darwin's publications, private papers and bibliography, supplementary works including biographies, obituaries and reviews

Darwin Correspondence Project

Full text and notes for complete correspondence to 1867, with summaries of all the rest, and pages of commentary

Darwin Manuscript Project

* * View books owned and annotated b

Charles Darwin

at the online Biodiversity Heritage Library. *

Digitised Darwin Manuscripts

in

Charles Darwin in the British horticultural press

– Occasional Papers from RHS Lindley Library, volume 3 July 2010 *

Obituary of Charles Darwin

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Darwin, Charles 1809 births 1882 deaths 19th-century British biologists 19th-century English writers 19th-century Anglicans 19th-century English naturalists 19th-century English geologists Alumni of Christ's College, Cambridge Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Botanists with author abbreviations British carcinologists British evolutionary biologists British science communicators Burials at Westminster Abbey Circumnavigators of the globe Coleopterists Darwin–Wedgwood family Deaths from coronary thrombosis English abolitionists English agnostics English Anglicans English entomologists English justices of the peace English sceptics English travel writers Ethologists Fellows of the Linnean Society of London Fellows of the Royal Entomological Society Fellows of the Royal Geographical Society Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of the Zoological Society of London Human evolution theorists Human evolution Independent scientists Malthusians Members of the American Philosophical Society Members of the Lincean Academy Members of the Royal Academy of Belgium Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences People educated at Shrewsbury School Plant collectors Scientists from Shrewsbury Recipients of the Copley Medal Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) Royal Medal winners Theoretical biologists Wollaston Medal winners

naturalist

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

, geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the structure, composition, and History of Earth, history of Earth. Geologists incorporate techniques from physics, chemistry, biology, mathematics, and geography to perform research in the Field research, ...

, and biologist

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual Cell (biology), cell, a multicellular organism, or a Community (ecology), community of Biological inter ...

, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology

Evolutionary biology is the subfield of biology that studies the evolutionary processes such as natural selection, common descent, and speciation that produced the diversity of life on Earth. In the 1930s, the discipline of evolutionary biolo ...

. His proposition that all species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

of life have descended from a common ancestor

Common descent is a concept in evolutionary biology applicable when one species is the ancestor of two or more species later in time. According to modern evolutionary biology, all living beings could be descendants of a unique ancestor commonl ...

is now generally accepted and considered a fundamental scientific concept. In a joint presentation with Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was an English naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He independently conceived the theory of evolution through natural selection; his 1858 pap ...

, he introduced his scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

resulted from a process he called natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

, in which the struggle for existence

The concept of the struggle for existence (or struggle for life) concerns the competition or battle for resources needed to live. It can refer to human society, or to organisms in nature. The concept is ancient, and the term ''struggle for existe ...

has a similar effect to the artificial selection involved in selective breeding

Selective breeding (also called artificial selection) is the process by which humans use animal breeding and plant breeding to selectively develop particular phenotypic traits (characteristics) by choosing which typically animal or plant m ...

.. Darwin has been described as one of the most influential figures in human history

Human history or world history is the record of humankind from prehistory to the present. Early modern human, Modern humans evolved in Africa around 300,000 years ago and initially lived as hunter-gatherers. They Early expansions of hominin ...

and was honoured by burial in Westminster Abbey.

Darwin's early interest in nature led him to neglect his medical education at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

; instead, he helped to investigate marine invertebrates

Marine invertebrates are invertebrate animals that live in marine habitats, and make up most of the macroscopic life in the oceans. It is a polyphyletic blanket term that contains all marine animals except the marine vertebrates, including the ...

. His studies at the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

's Christ's College from 1828 to 1831 encouraged his passion for natural science

Natural science or empirical science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer ...

.. However, it was his five-year voyage on from 1831 to 1836 that truly established Darwin as an eminent geologist. The observations and theories he developed during his voyage supported Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known today for his association with Charles ...

's concept of gradual geological change. Publication of his journal of the voyage made Darwin famous as a popular author.

Puzzled by the geographical distribution of wildlife and fossils he collected on the voyage, Darwin began detailed investigations and, in 1838, devised his theory of natural selection. Although he discussed his ideas with several naturalists, he needed time for extensive research, and his geological work had priority. He was writing up his theory in 1858 when Alfred Russel Wallace sent him an essay that described the same idea, prompting the immediate joint submission of both their theories to the Linnean Society of London

The Linnean Society of London is a learned society dedicated to the study and dissemination of information concerning natural history, evolution, and Taxonomy (biology), taxonomy. It possesses several important biological specimen, manuscript a ...

. Darwin's work established evolutionary descent with modification as the dominant scientific explanation of natural diversification. In 1871, he examined human evolution

''Homo sapiens'' is a distinct species of the hominid family of primates, which also includes all the great apes. Over their evolutionary history, humans gradually developed traits such as Human skeletal changes due to bipedalism, bipedalism, de ...

and sexual selection

Sexual selection is a mechanism of evolution in which members of one sex mate choice, choose mates of the other sex to mating, mate with (intersexual selection), and compete with members of the same sex for access to members of the opposite sex ...

in ''The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex

''The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex'' is a book by English naturalist Charles Darwin, first published in 1871, which applies evolutionary theory to human evolution, and details his theory of sexual selection, a form of biolog ...

'', followed by ''The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals

''The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals'' is Charles Darwin's third major work of evolutionary theory, following ''On the Origin of Species'' (1859) and '' The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex'' (1871). Initially in ...

'' (1872). His research on plants was published in a series of books, and in his final book, ''The Formation of Vegetable Mould, through the Actions of Worms'' (1881), he examined earthworm

An earthworm is a soil-dwelling terrestrial invertebrate that belongs to the phylum Annelida. The term is the common name for the largest members of the class (or subclass, depending on the author) Oligochaeta. In classical systems, they we ...

s and their effect on soil.

Darwin published his theory of evolution with compelling evidence in his 1859 book ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

''. By the 1870s, the scientific community and a majority of the educated public had accepted evolution as a fact. However, many initially favoured competing explanations that gave only a minor role to natural selection, and it was not until the emergence of the modern evolutionary synthesis

Modern synthesis or modern evolutionary synthesis refers to several perspectives on evolutionary biology, namely:

* Modern synthesis (20th century), the term coined by Julian Huxley in 1942 to denote the synthesis between Mendelian genetics and s ...

from the 1930s to the 1950s that a broad consensus developed in which natural selection was the basic mechanism of evolution... Darwin's scientific discovery is the unifying theory of the life sciences

This list of life sciences comprises the branches of science that involve the scientific study of life – such as microorganisms, plants, and animals including human beings. This science is one of the two major branches of natural science, ...

, explaining the diversity of life

Biodiversity is the variability of life on Earth. It can be measured on various levels. There is for example genetic variability, species diversity, ecosystem diversity and phylogenetic diversity. Diversity is not distributed evenly on Earth. ...

.

Biography

Early life and education

Darwin was born inShrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , ) is a market town and civil parish in Shropshire (district), Shropshire, England. It is sited on the River Severn, northwest of Wolverhampton, west of Telford, southeast of Wrexham and north of Hereford. At the 2021 United ...

, Shropshire, on 12 February 1809, at his family's home, The Mount. He was the fifth of six children of wealthy society doctor and financier Robert Darwin

Robert Waring Darwin (30 May 1766 – 13 November 1848) was an English medical doctor who is today best known as the father of naturalist Charles Darwin. He was a member of the influential Darwin–Wedgwood family.

Biography

Darwin was born i ...

and Susannah Darwin

Susannah Darwin (née Wedgwood, 3 January 1765 – 15 July 1817) was the wife of Robert Darwin, a wealthy doctor, and mother of naturalist Charles Darwin, and part of the Wedgwood pottery family.

Biography

Early life

Susannah Wedgwood was t ...

(née Wedgwood). His grandfathers Erasmus Darwin

Erasmus Robert Darwin (12 December 173118 April 1802) was an English physician. One of the key thinkers of the Midlands Enlightenment, he was also a natural philosophy, natural philosopher, physiology, physiologist, Society for Effecting the ...

and Josiah Wedgwood

Josiah Wedgwood (12 July 1730 – 3 January 1795) was an English potter, entrepreneur and abolitionist. Founding the Wedgwood company in 1759, he developed improved pottery bodies by systematic experimentation, and was the leader in the indu ...

were both prominent abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. T ...

. Erasmus Darwin had praised general concepts of evolution and common descent

Common descent is a concept in evolutionary biology applicable when one species is the ancestor of two or more species later in time. According to modern evolutionary biology, all living beings could be descendants of a unique ancestor commonl ...

in his ''Zoonomia

''Zoonomia; or the Laws of Organic Life'' (1794–96) is a two-volume medical work by Erasmus Darwin dealing with pathology, anatomy, psychology, and the functioning of the body. Its primary framework is one of associationist psychophysiology

...

'' (1794), a poetic fantasy of gradual creation including undeveloped ideas anticipating concepts his grandson expanded.

Both families were largely Unitarian, though the Wedgwoods were adopting

Both families were largely Unitarian, though the Wedgwoods were adopting Anglicanism

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

. Robert Darwin, a freethinker

Freethought (sometimes spelled free thought) is an unorthodox attitude or belief.

A freethinker holds that beliefs should not be formed on the basis of authority, tradition, revelation, or dogma, and should instead be reached by other meth ...

, had baby Charles baptised

Baptism (from ) is a Christians, Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by aspersion, sprinkling or affusion, pouring water on the head, or by immersion baptism, immersing in water eit ...

in November 1809 in the Anglican St Chad's Church, Shrewsbury

St Chad's Church in Shrewsbury is traditionally understood to have been founded in Saxon times. Offa of Mercia, King Offa, who reigned in Mercia from 757 to 796 AD, is believed to have founded the church, though it is possible it has an earlier ...

, but Charles and his siblings attended the local Unitarian Church with their mother. The eight-year-old Charles already had a taste for natural history and collecting when he joined the day school run by its preacher in 1817. That July, his mother died. From September 1818, he joined his older brother Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus ( ; ; 28 October c. 1466 – 12 July 1536), commonly known in English as Erasmus of Rotterdam or simply Erasmus, was a Dutch Christian humanist, Catholic priest and Catholic theology, theologian, educationalist ...

in attending the nearby Anglican Shrewsbury School

Shrewsbury School is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school in Shrewsbury.

Founded in 1552 by Edward VI by royal charter, to replace the town's Saxon collegiate foundations which were disestablished in the sixteenth century, Shrewsb ...

as a boarder

Boarder may refer to:

Persons

A boarder may be a person who:

*snowboards

*skateboards

*bodyboards

* surfs

*stays at a boarding house

*attends a boarding school

*takes part in a boarding attack

Other uses

* ''The Star Boarder'', a 1914 American ...

.;. Darwin spent the summer of 1825 as an apprentice doctor, helping his father treat the poor of Shropshire, before going to the well-regarded

University of Edinburgh Medical School

The University of Edinburgh Medical School (also known as Edinburgh Medical School) is the medical school of the University of Edinburgh in Scotland and the United Kingdom and part of the University of Edinburgh College of Medicine and Veterinar ...

with his brother Erasmus in October 1825. Darwin found lectures dull and surgery distressing, so he neglected his studies. He learned taxidermy

Taxidermy is the art of preserving an animal's body by mounting (over an armature) or stuffing, for the purpose of display or study. Animals are often, but not always, portrayed in a lifelike state. The word ''taxidermy'' describes the proces ...

in around 40 daily hour-long sessions from John Edmonstone

John Edmonstone was a taxidermist and teacher of taxidermy in Edinburgh, Scotland. He was an influential Black Briton.

Early life

Born into slavery on a wood plantation in Demerara, British Guiana (present-day Guyana, South America), he was ...

, a freed black slave who had accompanied Charles Waterton

Charles Waterton (3 June 1782 – 27 May 1865) was an English naturalist, plantation overseer and explorer best known for his pioneering work regarding conservation.

Family and religion

Waterton was of a Roman Catholic landed gentry family de ...

in the South American rainforest

Rainforests are forests characterized by a closed and continuous tree Canopy (biology), canopy, moisture-dependent vegetation, the presence of epiphytes and lianas and the absence of wildfire. Rainforests can be generally classified as tropi ...

.;. In Darwin's second year at the university, he joined the

Plinian Society

The Plinian Society was a club at the University of Edinburgh for students interested in natural history. It was founded in 1823. Several of its members went on to have prominent careers, most notably Charles Darwin who announced his first scient ...

, a student natural-history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

group featuring lively debates in which radical democratic

Radical democracy is a type of democracy that advocates the radical extension of equality and liberty. Radical democracy is concerned with a radical extension of equality and freedom, following the idea that democracy is an unfinished, inclusive, ...

students with materialistic views challenged orthodox religious concepts of science. He assisted Robert Edmond Grant

Robert Edmond Grant MD FRCPEd FRS FRSE FZS FGS (11 November 1793 – 23 August 1874) was a British anatomist and zoologist.

Life

Grant was born at Argyll Square in Edinburgh (demolished to create Chambers Street), the son of Alexander Gra ...

's investigations of the anatomy and life cycle of marine invertebrates

Marine invertebrates are invertebrate animals that live in marine habitats, and make up most of the macroscopic life in the oceans. It is a polyphyletic blanket term that contains all marine animals except the marine vertebrates, including the ...

in the Firth of Forth

The Firth of Forth () is a firth in Scotland, an inlet of the North Sea that separates Fife to its north and Lothian to its south. Further inland, it becomes the estuary of the River Forth and several other rivers.

Name

''Firth'' is a cognate ...

, and on 27 March 1827 presented at the Plinian his own discovery that black spores found in oyster

Oyster is the common name for a number of different families of salt-water bivalve molluscs that live in marine or brackish habitats. In some species, the valves are highly calcified, and many are somewhat irregular in shape. Many, but no ...

shells were the eggs of a skate leech

Leeches are segmented parasitism, parasitic or Predation, predatory worms that comprise the Class (biology), subclass Hirudinea within the phylum Annelida. They are closely related to the Oligochaeta, oligochaetes, which include the earthwor ...

. One day, Grant praised Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 – 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (; ), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biolo ...

's evolutionary ideas. Darwin was astonished by Grant's audacity, but had recently read similar ideas in his grandfather Erasmus' journals. Darwin was rather bored by Robert Jameson

image:Robert Jameson.jpg, Robert Jameson

Robert Jameson Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS FRSE (11 July 1774 – 19 April 1854) was a Scottish natural history, naturalist and mineralogist.

As Regius Professor of Natural History at the Univers ...

's natural-history course, which covered geologyincluding the debate between neptunism

Neptunism is a superseded scientific theory of geology proposed by Abraham Gottlob Werner (1749–1817) in the late 18th century, who proposed that rocks formed from the crystallisation of minerals in the early Earth's oceans.

The theory took ...

and plutonism

Plutonism is the geology, geologic theory that the igneous rocks forming the Earth originated from intrusive Magma, magmatic activity, with a continuing gradual process of weathering and erosion wearing away rocks, which were then deposited on t ...

. He learned the classification

Classification is the activity of assigning objects to some pre-existing classes or categories. This is distinct from the task of establishing the classes themselves (for example through cluster analysis). Examples include diagnostic tests, identif ...

of plants and assisted with work on the collections of the University Museum

A university museum is a repository of collections run by a university, typically founded to aid teaching and research within the institution of higher learning. The Ashmolean Museum at the University of Oxford in England is an early example, or ...

, one of the largest museums in Europe at the time.

Darwin's neglect of medical studies annoyed his father, who sent him to Christ's College, Cambridge

Christ's College is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge, England. The college includes the Master, the Fellows of the College, and about 450 undergraduate and 250 graduate students. The c ...

, in January 1828, to study for a Bachelor of Arts degree as the first step towards becoming an Anglican country parson

A parson is an ordained Christian person responsible for a small area, typically a parish. The term was formerly often used for some Anglican clergy and, more rarely, for ordained ministers in some other churches. It is no longer a formal term d ...

. Darwin was unqualified for Cambridge's ''Tripos

TRIPOS (''TRIvial Portable Operating System'') is a computer operating system. Development started in 1976 at the Computer Laboratory of Cambridge University and it was headed by Dr. Martin Richards. The first version appeared in January 1978 a ...

'' exams and was required instead to join the ordinary degree course. He preferred riding and shooting

Shooting is the act or process of discharging a projectile from a ranged weapon (such as a gun, bow, crossbow, slingshot, or blowpipe). Even the acts of launching flame, artillery, darts, harpoons, grenades, rockets, and guided missile ...

to studying.

During the first few months of Darwin's enrolment at Christ's College, his second cousin William Darwin Fox

The Reverend William Darwin Fox (23 April 1805 – 8 April 1880) was an English clergyman, naturalist, and a second cousin of Charles Darwin.

Early life

Fox was born in 1805 and initially raised at Thurleston Grange near Elvaston, Derbysh ...

was still studying there. Fox impressed him with his butterfly collection, introducing Darwin to entomology

Entomology (from Ancient Greek ἔντομον (''éntomon''), meaning "insect", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study") is the branch of zoology that focuses on insects. Those who study entomology are known as entomologists. In ...

and influencing him to pursue beetle

Beetles are insects that form the Taxonomic rank, order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Holometabola. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 40 ...

collecting.. He did this zealously and had some of his finds published in James Francis Stephens

James Francis Stephens (16 September 1792 – 22 December 1852) was an England, English entomologist and naturalist. He is known for his 12 volume ''Illustrations of British Entomology'' (1846) and the ''Manual of British Beetles'' (1839).

...

' ''Illustrations of British entomology'' (1829–1932).

Through Fox, Darwin became a close friend and follower of botany professor John Stevens Henslow

John Stevens Henslow (6 February 1796 – 16 May 1861) was an English Anglican priest, botanist and geologist. He is best remembered as friend and mentor to Charles Darwin.

Early life

Henslow was born at Rochester, Kent, the son of a solicit ...

. He met other leading parson-naturalist

A parson-naturalist was a cleric (a "parson", strictly defined as a country priest who held the living of a parish, but the term is generally extended to other clergy), who often saw the study of natural science as an extension of his religious wor ...

s who saw scientific work as religious natural theology

Natural theology is a type of theology that seeks to provide arguments for theological topics, such as the existence of a deity, based on human reason. It is distinguished from revealed theology, which is based on supernatural sources such as ...

, becoming known to these dons as "the man who walks with Henslow". When his own exams drew near, Darwin applied himself to his studies and was delighted by the language and logic of William Paley

William Paley (July 174325 May 1805) was an English Anglican clergyman, Christian apologetics, Christian apologist, philosopher, and Utilitarianism, utilitarian. He is best known for his natural theology exposition of the teleological argument ...

's ''Evidences of Christianity'' (1795).;. In his final examination in January 1831, Darwin did well, coming tenth out of 178 candidates for the ''ordinary'' degree. Darwin had to stay at Cambridge until June 1831. He studied Paley's ''

Natural Theology or Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the laws, elements and phenomena of the physical world, including life. Although humans are part ...

'' (first published in 1802), which made an argument for divine design in nature, explaining adaptation

In biology, adaptation has three related meanings. Firstly, it is the dynamic evolutionary process of natural selection that fits organisms to their environment, enhancing their evolutionary fitness. Secondly, it is a state reached by the p ...

as God acting through laws of nature.. He read John Herschel

Sir John Frederick William Herschel, 1st Baronet (; 7 March 1792 – 11 May 1871) was an English polymath active as a mathematician, astronomer, chemist, inventor and experimental photographer who invented the blueprint and did botanical work. ...

's new book, ''Preliminary Discourse on the Study of Natural Philosophy'' (1831), which described the highest aim of natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

as understanding such laws through inductive reasoning

Inductive reasoning refers to a variety of method of reasoning, methods of reasoning in which the conclusion of an argument is supported not with deductive certainty, but with some degree of probability. Unlike Deductive reasoning, ''deductive'' ...

based on observation, and Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 1769 – 6 May 1859) was a German polymath, geographer, natural history, naturalist, List of explorers, explorer, and proponent of Romanticism, Romantic philosophy and Romanticism ...

's ''Personal Narrative'' of scientific travels in 1799–1804. Inspired with "a burning zeal" to contribute, Darwin planned to visit Tenerife

Tenerife ( ; ; formerly spelled ''Teneriffe'') is the largest and most populous island of the Canary Islands, an Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Spain. With a land area of and a population of 965,575 inhabitants as of A ...

with some classmates after graduation to study natural history in the tropics. In preparation, he joined Adam Sedgwick

Adam Sedgwick FRS (; 22 March 1785 – 27 January 1873) was a British geologist and Anglican priest, one of the founders of modern geology. He proposed the Cambrian and Devonian period of the geological timescale. Based on work which he did ...

's geology course, then on 4 August travelled with him to spend a fortnight mapping strata

In geology and related fields, a stratum (: strata) is a layer of Rock (geology), rock or sediment characterized by certain Lithology, lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by v ...

in Wales..

Survey voyage on HMS ''Beagle''

Barmouth

Barmouth (formal ; colloquially ) is a seaside town and community in the county of Gwynedd, north-west Wales; it lies on the estuary of the Afon Mawddach and Cardigan Bay. Located in the historic county of Merionethshire, the Welsh form of t ...

. He returned home on 29 August to find a letter from Henslow proposing him as a suitable (if unfinished) naturalist for a self-funded supernumerary

Supernumerary means "exceeding the usual number".

Supernumerary may also refer to:

* Supernumerary actor, a performer in a film, television show, or stage production who has no role or purpose other than to appear in the background, more common ...

place on with captain Robert FitzRoy

Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy (5 July 1805 – 30 April 1865) was an English officer of the Royal Navy, politician and scientist who served as the second governor of New Zealand between 1843 and 1845. He achieved lasting fame as the captain of ...

, a position for a gentleman

''Gentleman'' (Old French: ''gentilz hom'', gentle + man; abbreviated ''gent.'') is a term for a chivalrous, courteous, or honorable man. Originally, ''gentleman'' was the lowest rank of the landed gentry of England, ranking below an esquire ...

rather than "a mere collector". The ship was to leave in four weeks on an expedition to chart the coastline of South America. Robert Darwin objected to his son's planned two-year voyage, regarding it as a waste of time, but was persuaded by his brother-in-law, Josiah Wedgwood II

Josiah Wedgwood II (3 April 1769 – 12 July 1843), the son of the English potter Josiah Wedgwood, continued his father's firm and was a Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP) for Stoke-upon-Trent (UK Parliament con ...

, to agree to (and fund) his son's participation. Darwin took care to remain in a private capacity to retain control over his collection, intending it for a major scientific institution.

After delays, the voyage began on 27 December 1831; it lasted almost five years. As FitzRoy had intended, Darwin spent most of that time on land investigating geology and making natural history collections, while HMS ''Beagle'' surveyed and charted coasts. He kept careful notes of his observations and theoretical speculations. At intervals during the voyage, his specimens were sent to Cambridge together with letters including a copy of his journal for his family. He had some expertise in geology, beetle collecting and dissecting marine invertebrates, but in all other areas, was a novice and ably collected specimens for expert appraisal. Despite suffering badly from seasickness, Darwin wrote copious notes while on board the ship. Most of his zoology notes are about marine invertebrates, starting with plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms that drift in Hydrosphere, water (or atmosphere, air) but are unable to actively propel themselves against ocean current, currents (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are ca ...

collected during a calm spell.

On their first stop ashore at St Jago in Cape Verde, Darwin found that a white band high in the volcanic rock

Volcanic rocks (often shortened to volcanics in scientific contexts) are rocks formed from lava erupted from a volcano. Like all rock types, the concept of volcanic rock is artificial, and in nature volcanic rocks grade into hypabyssal and me ...

cliffs included seashells. FitzRoy had given him the first volume of Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known today for his association with Charles ...

's ''Principles of Geology

''Principles of Geology: Being an Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth's Surface, by Reference to Causes Now in Operation'' is a book by the Scottish geologist Charles Lyell that was first published in 3 volumes from 1830 to 1833. ...

'', which set out uniformitarian

Uniformitarianism, also known as the Doctrine of Uniformity or the Uniformitarian Principle, is the assumption that the same natural laws and processes that operate in our present-day scientific observations have always operated in the universe in ...

concepts of land slowly rising or falling over immense periods, and Darwin saw things Lyell's way, theorising and thinking of writing a book on geology. When they reached Brazil, Darwin was delighted by the tropical forest

Tropical forests are forested ecoregions with tropical climates – that is, land areas approximately bounded by the Tropic of Cancer, tropics of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn, Capricorn, but possibly affected by other factors such as prevailing ...

, but detested the sight of slavery there, and disputed this issue with FitzRoy.

The survey continued to the south in Patagonia

Patagonia () is a geographical region that includes parts of Argentina and Chile at the southern end of South America. The region includes the southern section of the Andes mountain chain with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and glaciers ...

. They stopped at Bahía Blanca

Bahía Blanca (; English: ''White Bay''), colloquially referred to by its own local inhabitants as simply Bahía, is a city in the Buenos Aires Province, Buenos Aires province of Argentina, centered on the northwestern end of the eponymous Blanc ...

, and in cliffs near Punta Alta

Punta Alta is a city in Argentina, about 25 kilometers southeast of Bahía Blanca. It has a population of 57,293. It is the capital ("cabecera") of the Coronel Rosales Partido. It was founded on 2 July 1898.

The city is located near the Atlant ...

Darwin made a major find of fossil bones of huge extinct mammals

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its last member. A taxon may become functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to reproduce and recover. As a species' potential range may be ...

beside modern seashells, indicating recent extinction

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

with no signs of change in climate or catastrophe. He found bony plates like a giant version of the armour on local armadillo

Armadillos () are New World placental mammals in the order (biology), order Cingulata. They form part of the superorder Xenarthra, along with the anteaters and sloths. 21 extant species of armadillo have been described, some of which are dis ...

s. From a jaw and tooth he identified the gigantic ''Megatherium

''Megatherium'' ( ; from Greek () 'great' + () 'beast') is an extinct genus of ground sloths endemic to South America that lived from the Early Pliocene through the end of the Late Pleistocene. It is best known for the elephant-sized type spe ...

'', then from Cuvier's description thought the armour was from this animal. The finds were shipped to England, and scientists found the fossils of great interest. In Patagonia, Darwin came to wrongly believe the territory was devoid of reptiles.

On rides with gaucho

A gaucho () or gaúcho () is a skilled horseman, reputed to be brave and unruly. The figure of the gaucho is a folk symbol of Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, the southern part of Bolivia, and the south of Chilean Patago ...

s into the interior to explore geology and collect more fossils, Darwin gained social, political and anthropological

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behaviour, wh ...

insights into both native and colonial people at a time of revolution, and learnt that two types of rhea had separate but overlapping territories. Further south, he saw stepped plains of shingle and seashells as raised beach

A raised beach, coastal terrace,Pinter, N (2010): 'Coastal Terraces, Sealevel, and Active Tectonics' (educational exercise), from 2/04/2011/ref> or perched coastline is a relatively flat, horizontal or gently inclined surface of marine origin, ...

es at a series of elevations. He read Lyell's second volume and accepted its view of "centres of creation" of species, but his discoveries and theorising challenged Lyell's ideas of smooth continuity and of extinction of species.

Three Fuegians

Fuegians are the indigenous inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego, at the southern tip of South America. The name has been credited to Captain James Weddell, who supposedly created the term in 1822.

The indigenous Fuegians belonged to several differ ...

on board, who had been seized during the first ''Beagle'' voyage then given Christian education in England, were returning with a missionary. Darwin found them friendly and civilised, yet at Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego (, ; Spanish for "Land of Fire", rarely also Fireland in English) is an archipelago off the southernmost tip of the South America, South American mainland, across the Strait of Magellan.

The archipelago consists of the main is ...

he met "miserable, degraded savages", as different as wild from domesticated animals. He remained convinced that, despite this diversity, all humans were interrelated with a shared origin and potential for improvement towards civilisation. Unlike his scientist friends, he now thought there was no unbridgeable gap between humans and animals. A year on, the mission had been abandoned. The Fuegian they had named Jemmy Button

Orundellico, known as "Jeremy Button" or "Jemmy Button" or "Jimmy Button" (c. 1815–1864), was a member of the Yahgan (or Yámana) people from islands around Tierra del Fuego in modern Chile and Argentina. He was taken to England by Captain ...

lived like the other natives, had a wife, and had no wish to return to England.

Darwin experienced an earthquake in Chile in 1835 and saw signs that the land had just been raised, including

Darwin experienced an earthquake in Chile in 1835 and saw signs that the land had just been raised, including mussel

Mussel () is the common name used for members of several families of bivalve molluscs, from saltwater and Freshwater bivalve, freshwater habitats. These groups have in common a shell whose outline is elongated and asymmetrical compared with other ...

-beds stranded above high tide. High in the Andes

The Andes ( ), Andes Mountains or Andean Mountain Range (; ) are the List of longest mountain chains on Earth, longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range ...

he saw seashells and several fossil trees that had grown on a sand beach. He theorised that as the land rose, oceanic islands

An island or isle is a piece of land, distinct from a continent, completely surrounded by water. There are continental islands, which were formed by being split from a continent by plate tectonics, and oceanic islands, which have never been ...

sank, and coral reef

A coral reef is an underwater ecosystem characterized by reef-building corals. Reefs are formed of colonies of coral polyps held together by calcium carbonate. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, whose polyps cluster in group ...

s round them grew to form atoll

An atoll () is a ring-shaped island, including a coral rim that encircles a lagoon. There may be coral islands or cays on the rim. Atolls are located in warm tropical or subtropical parts of the oceans and seas where corals can develop. Most ...

s.

On the geologically new Galápagos Islands

The Galápagos Islands () are an archipelago of volcanic islands in the Eastern Pacific, located around the equator, west of the mainland of South America. They form the Galápagos Province of the Republic of Ecuador, with a population of sli ...

, Darwin looked for evidence attaching wildlife to an older "centre of creation", and found mockingbird

Mockingbirds are a group of New World passerine birds from the family (biology), family Mimidae. They are best known for the habit of some species Mimicry, mimicking the songs of other birds and the sounds of insects and amphibians, often loudly ...

s allied to those in Chile but differing from island to island. He heard that slight variations in the shape of tortoise

Tortoises ( ) are reptiles of the family Testudinidae of the order Testudines (Latin for "tortoise"). Like other turtles, tortoises have a shell to protect from predation and other threats. The shell in tortoises is generally hard, and like o ...

shells showed which island they came from, but failed to collect them, even after eating tortoises taken on board as food. In Australia, the marsupial

Marsupials are a diverse group of mammals belonging to the infraclass Marsupialia. They are natively found in Australasia, Wallacea, and the Americas. One of marsupials' unique features is their reproductive strategy: the young are born in a r ...

rat-kangaroo

Potoroidae is a family of marsupials, small Australian animals known as bettongs, potoroos, and rat-kangaroos. All are rabbit-sized, brown, jumping marsupials and resemble a large rodent or a very small wallaby.

Taxonomy

The potoroids are s ...

and the platypus

The platypus (''Ornithorhynchus anatinus''), sometimes referred to as the duck-billed platypus, is a semiaquatic, egg-laying mammal endemic to eastern Australia, including Tasmania. The platypus is the sole living representative or monotypi ...

seemed so unusual that Darwin thought it was almost as though two distinct Creators had been at work. He found the Aborigines "good-humoured & pleasant", their numbers depleted by European settlement.

FitzRoy investigated how the atolls of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands

The Cocos (Keeling) Islands (), officially the Territory of Cocos (Keeling) Islands (; ), are an Australian external territory in the Indian Ocean, comprising a small archipelago approximately midway between Australia and Sri Lanka and rel ...

had formed, and the survey supported Darwin's theorising. FitzRoy began writing the official ''Narrative'' of the ''Beagle'' voyages, and after reading Darwin's diary, he proposed incorporating it into the account. Darwin's ''Journal'' was eventually rewritten as a separate third volume, on geology and natural history.

In Cape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

, South Africa, Darwin and FitzRoy met John Herschel, who had recently written to Lyell praising his uniformitarianism

Uniformitarianism, also known as the Doctrine of Uniformity or the Uniformitarian Principle, is the assumption that the same natural laws and processes that operate in our present-day scientific observations have always operated in the universe in ...

as opening bold speculation on "that mystery of mysteries, the replacement of extinct species by others" as "a natural in contradistinction to a miraculous process".

When organising his notes as the ship sailed home, Darwin wrote that, if his growing suspicions about the mockingbirds, the tortoises and the Falkland Islands fox were correct, "such facts undermine the stability of Species", then cautiously added "would" before "undermine".He later wrote that such facts "seemed to me to throw some light on the origin of species". Without telling Darwin, extracts from his letters to Henslow had been read to scientific societies, printed as a pamphlet for private distribution among members of the

Cambridge Philosophical Society

The Cambridge Philosophical Society (CPS) is a scientific society at the University of Cambridge. It was founded in 1819. The name derives from the medieval use of the word philosophy to denote any research undertaken outside the fields of law ...

, and reported in magazines, including ''The Athenaeum''. Darwin first heard of this at Cape Town, and at Ascension Island

Ascension Island is an isolated volcanic island, 7°56′ south of the Equator in the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic Ocean. It is about from the coast of Africa and from the coast of South America. It is governed as part of the British Overs ...

read of Sedgwick's prediction that Darwin "will have a great name among the Naturalists of Europe".

Inception of Darwin's evolutionary theory

On 2 October 1836, ''Beagle'' anchored at Falmouth, Cornwall. Darwin promptly made the long coach journey to Shrewsbury to visit his home and see relatives. He then hurried to

On 2 October 1836, ''Beagle'' anchored at Falmouth, Cornwall. Darwin promptly made the long coach journey to Shrewsbury to visit his home and see relatives. He then hurried to Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

to see Henslow, who advised him on finding available naturalists to catalogue Darwin's animal collections and to take on the botanical specimens. Darwin's father organised investments, enabling his son to be a self-funded gentleman scientist

An independent scientist (historically also known as gentleman scientist) is a financially independent scientist who pursues scientific study without direct affiliation to a public institution such as a university or government-run research and ...

, and an excited Darwin went around the London institutions being fêted and seeking experts to describe the collections. British zoologists at the time had a huge backlog of work, due to natural history collecting being encouraged throughout the British Empire, and there was a danger of specimens just being left in storage.

Charles Lyell eagerly met Darwin for the first time on 29 October and soon introduced him to the up-and-coming anatomist Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

, who had the facilities of the Royal College of Surgeons

The Royal College of Surgeons is an ancient college (a form of corporation) established in England to regulate the activity of surgeons. Derivative organisations survive in many present and former members of the Commonwealth. These organisations ...

to work on the fossil bones collected by Darwin. Owen's surprising results included other gigantic extinct ground sloth

Ground sloths are a diverse group of extinct sloths in the mammalian superorder Xenarthra. They varied widely in size with the largest, belonging to genera '' Lestodon'', ''Eremotherium'' and ''Megatherium'', being around the size of elephants. ...

s as well as the ''Megatherium'' Darwin had identified, a near complete skeleton of the unknown ''Scelidotherium

''Scelidotherium'' is an extinct genus of ground sloth of the family Scelidotheriidae, endemic to South America during the Late Pleistocene epoch. It lived from 780,000 to 11,000 years ago, existing for approximately .

Description

It is charac ...

'' and a hippopotamus

The hippopotamus (''Hippopotamus amphibius;'' ; : hippopotamuses), often shortened to hippo (: hippos), further qualified as the common hippopotamus, Nile hippopotamus and river hippopotamus, is a large semiaquatic mammal native to sub-Sahar ...

-sized rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the Order (biology), order Rodentia ( ), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and Mandible, lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal specie ...

-like skull named ''Toxodon

''Toxodon'' (meaning "bow tooth" in reference to the curvature of the teeth) is an extinct genus of large ungulate native to South America from the Pliocene to the end of the Late Pleistocene. ''Toxodon'' is a member of Notoungulata, an order of ...

'' resembling a giant capybara

The capybara or greater capybara (''Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris'') is the largest living rodent, native to South America. It is a member of the genus '' Hydrochoerus''. The only other extant member is the lesser capybara (''Hydrochoerus isthmi ...

. The armour fragments were actually from ''Glyptodon

''Glyptodon'' (; ) is a genus of glyptodont, an extinct group of large, herbivorous armadillos, that lived from the Pliocene, around 3.2 million years ago, to the early Holocene, around 11,000 years ago, in South America. It is one of, if not th ...

'', a huge armadillo-like creature, as Darwin had initially thought. These extinct creatures were related to living species in South America.

In mid-December, Darwin took lodgings in Cambridge to arrange expert classification of his collections, and prepare his own research for publication. Questions of how to combine his diary into the ''Narrative'' were resolved at the end of the month when FitzRoy accepted Broderip's advice to make it a separate volume, and Darwin began work on his ''Journal and Remarks''.

Darwin's first paper showed that the South American landmass was slowly rising. With Lyell's enthusiastic backing, he read it to the Geological Society of London

The Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and the largest in Europe, with more than 12,000 Fellows.

Fe ...

on 4 January 1837. On the same day, he presented his mammal and bird specimens to the Zoological Society. The ornithologist John Gould

John Gould (; 14 September 1804 – 3 February 1881) was an English ornithologist who published monographs on birds, illustrated by plates produced by his wife, Elizabeth Gould (illustrator), Elizabeth Gould, and several other artists, includ ...

soon announced that the Galápagos birds that Darwin had thought a mixture of blackbirds, " gros-beaks" and finch

The true finches are small to medium-sized passerine birds in the family Fringillidae. Finches generally have stout conical bills adapted for eating seeds and nuts and often have colourful plumage. They occupy a great range of habitats where the ...

es, were, in fact, twelve separate species of finches. On 17 February, Darwin was elected to the Council of the Geological Society, and Lyell's presidential address presented Owen's findings on Darwin's fossils, stressing geographical continuity of species as supporting his uniformitarian ideas.

Early in March, Darwin moved to London to be near this work, joining Lyell's social circle of scientists and experts such as

Early in March, Darwin moved to London to be near this work, joining Lyell's social circle of scientists and experts such as Charles Babbage

Charles Babbage (; 26 December 1791 – 18 October 1871) was an English polymath. A mathematician, philosopher, inventor and mechanical engineer, Babbage originated the concept of a digital programmable computer.

Babbage is considered ...

, who described God as a programmer of laws. Darwin stayed with his freethinking

Freethought (sometimes spelled free thought) is an unorthodox attitude or belief.

A freethinker holds that beliefs should not be formed on the basis of authority, tradition, revelation, or dogma, and should instead be reached by other meth ...

brother Erasmus, part of this Whig circle and a close friend of the writer Harriet Martineau

Harriet Martineau (12 June 1802 – 27 June 1876) was an English social theorist.Hill, Michael R. (2002''Harriet Martineau: Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives'' Routledge. She wrote from a sociological, holism, holistic, religious and ...

, who promoted the Malthusianism

Malthusianism is a theory that population growth is potentially exponential, according to the Malthusian growth model, while the growth of the food supply or other resources is linear, which eventually reduces living standards to the point of trig ...

that underpinned the controversial Whig Poor Law reforms to stop welfare from causing overpopulation and more poverty. As a Unitarian, she welcomed the radical

Radical (from Latin: ', root) may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Classical radicalism, the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and Latin America in the 19th century

*Radical politics ...

implications of transmutation of species

The Transmutation of species and transformism are 18th and early 19th-century ideas about the change of one species into another that preceded Charles Darwin's theory of evolution through natural selection. The French ''Transformisme'' was a ter ...

, promoted by Grant and younger surgeons influenced by Geoffroy. Transmutation was anathema to Anglicans defending social order, but reputable scientists openly discussed the subject, and there was wide interest in John Herschel's letter praising Lyell's approach as a way to find a natural cause of the origin of new species.

Gould met Darwin and told him that the Galápagos mockingbirds from different islands were separate species, not just varieties, and what Darwin had thought was a "wren

Wrens are a family, Troglodytidae, of small brown passerine birds. The family includes 96 species and is divided into 19 genera. All species are restricted to the New World except for the Eurasian wren that is widely distributed in the Old Worl ...

" was in the finch group. Darwin had not labelled the finches by island, but from the notes of others on the ship, including FitzRoy, he allocated species to islands. The two rheas were distinct species, and on 14 March Darwin announced how their distribution changed going southwards.

By mid-March 1837, barely six months after his return to England, Darwin was speculating in his ''Red Notebook'' on the possibility that "one species does change into another" to explain the geographical distribution of living species such as the rheas, and extinct ones such as the strange extinct mammal ''Macrauchenia

''Macrauchenia'' ("long llama", based on the now-invalid llama genus, ''Auchenia'', from Greek "big neck") is an extinct genus of large ungulate native to South America from the Pliocene or Middle Pleistocene to the end of the Late Pleistocene. I ...

'', which resembled a giant guanaco

The guanaco ( ; ''Lama guanicoe'') is a camelid native to South America, closely related to the llama. Guanacos are one of two wild South American camelids; the other species is the vicuña, which lives at higher elevations.

Etymology

The gua ...

, a llama relative. Around mid-July, he recorded in his "B" notebook his thoughts on lifespan and variation across generationsexplaining the variations he had observed in Galápagos tortoise

The Galápagos tortoise or Galápagos giant tortoise (''Chelonoidis niger'') is a very large species of tortoise in the genus ''Chelonoidis'' (which also contains three smaller species from mainland South America). The species comprises 15 subsp ...

s, mockingbirds, and rheas. He sketched branching descent, and then a genealogical

Genealogy () is the study of families, family history, and the tracing of their lineages. Genealogists use oral interviews, historical records, genetic analysis, and other records to obtain information about a family and to demonstrate kin ...

branching of a single evolutionary tree

A phylogenetic tree or phylogeny is a graphical representation which shows the evolutionary history between a set of species or taxa during a specific time.Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA. In o ...

, in which "It is absurd to talk of one animal being higher than another", thereby discarding Lamarck's idea of independent lineages progressing to higher forms.

Overwork, illness, and marriage

While developing this intensive study of transmutation, Darwin became mired in more work. Still rewriting his ''Journal'', he took on editing and publishing the expert reports on his collections, and with Henslow's help obtained a Treasury grant of £1,000 to sponsor this multi-volume ''Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle

''The Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle Under the Command of Captain Fitzroy, R.N., during the Years 1832 to 1836'' is a 5-part book published unbound in nineteen numbers as they were ready, between February 1838 and October 1843. It was writ ...

'', a sum equivalent to about £115,000 in 2021. He stretched the funding to include his planned books on geology, and agreed to unrealistic dates with the publisher. As the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the reign of Queen Victoria, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. Slightly different definitions are sometimes used. The era followed the ...

began, Darwin pressed on with writing his ''Journal'', and in August 1837 began correcting printer's proofs.

As Darwin worked under pressure, his health suffered. On 20 September, he had "an uncomfortable palpitation

Palpitations occur when a person becomes aware of their heartbeat. The heartbeat may feel hard, fast, or uneven in their chest.

Symptoms include a very fast or irregular heartbeat. Palpitations are a sensory symptom. They are often described as ...

of the heart", so his doctors urged him to "knock off all work" and live in the country for a few weeks. After visiting Shrewsbury, he joined his Wedgwood relatives at Maer Hall

upright=1.35, Maer Hall

Maer Hall is a large Grade II listed 17th-century country house in Maer, Staffordshire, set in a park which is listed Grade II in Historic England's Register of Parks and Gardens

The large stone-built country house and ...

, Staffordshire, but found them too eager for tales of his travels to give him much rest. His charming, intelligent, and cultured cousin Emma Wedgwood

Emma Darwin (; 2 May 1808 – 2 October 1896) was an English woman who was the cousin marriage, wife and first cousin of Charles Darwin. They were married on 29 January 1839 and were the parents of ten children, seven of whom survived to adulth ...

, nine months older than Darwin, was nursing his invalid aunt. His uncle Josiah pointed out an area of ground where cinders had disappeared under loam

Loam (in geology and soil science) is soil composed mostly of sand (particle size > ), silt (particle size > ), and a smaller amount of clay (particle size < ). By weight, its mineral composition is about 40–40–20% concentration of sand–si ...

and suggested that this might have been the work of earthworm

An earthworm is a soil-dwelling terrestrial invertebrate that belongs to the phylum Annelida. The term is the common name for the largest members of the class (or subclass, depending on the author) Oligochaeta. In classical systems, they we ...

s, inspiring "a new & important theory" on their role in soil formation

Soil formation, also known as pedogenesis, is the process of soil genesis as regulated by the effects of place, environment, and history. Biogeochemical processes act to both create and destroy order ( anisotropy) within soils. These alteration ...

, which Darwin presented at the Geological Society on 1 November 1837. His ''Journal'' was printed and ready for publication by the end of February 1838, as was the first volume of the ''Narrative'', but FitzRoy was still working hard to finish his own volume.

William Whewell

William Whewell ( ; 24 May 17946 March 1866) was an English polymath. He was Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. In his time as a student there, he achieved distinction in both poetry and mathematics.

The breadth of Whewell's endeavours is ...

pushed Darwin to take on the duties of Secretary of the Geological Society. After initially declining the work, he accepted the post in March 1838. Despite the grind of writing and editing the ''Beagle'' reports, Darwin made remarkable progress on transmutation, taking every opportunity to question expert naturalists and, unconventionally, people with practical experience in selective breeding

Selective breeding (also called artificial selection) is the process by which humans use animal breeding and plant breeding to selectively develop particular phenotypic traits (characteristics) by choosing which typically animal or plant m ...

such as farmers and pigeon fanciers

Pigeon keeping or pigeon fancying is the art and science of breeding domestic pigeons. People have practiced pigeon keeping for at least 5,000 years and in almost every part of the world. In that time, humans have substantially altered the morpho ...

. Over time, his research drew on information from his relatives and children, the family butler, neighbours, colonists and former shipmates. He included mankind in his speculations from the outset, and on seeing an orangutan

Orangutans are great apes native to the rainforests of Indonesia and Malaysia. They are now found only in parts of Borneo and Sumatra, but during the Pleistocene they ranged throughout Southeast Asia and South China. Classified in the genus ...

in the zoo on 28 March 1838 noted its childlike behaviour.

The strain took a toll, and by June he was being laid up for days on end with stomach problems, headaches and heart symptoms. For the rest of his life, he was repeatedly incapacitated with episodes of stomach pains, vomiting, severe boil

A boil, also called a furuncle, is a deep folliculitis, which is an infection of the hair follicle. It is most commonly caused by infection by the bacterium ''Staphylococcus aureus'', resulting in a painful swollen area on the skin caused by ...

s, palpitations, trembling and other symptoms, particularly during times of stress, such as attending meetings or making social visits. The cause of Darwin's illness remained unknown, and attempts at treatment had only ephemeral success.

On 23 June, he took a break and went "geologising" in Scotland. He visited Glen Roy

Glen Roy (, meaning "red glen") in the Lochaber area of the Scottish Highlands, Highlands of Scotland is a glen noted for the geological phenomenon of three loch terrace (geology), terraces known as the Parallel Roads of Glen Roy. The terrace ...

in glorious weather to see the parallel "roads" cut into the hillsides at three heights. He later published his view that these were marine-raised beaches, but then had to accept that they were shorelines of a proglacial lake

In geology, a proglacial lake is a lake formed either by the damming action of a moraine during the retreat of a melting glacier, a glacial ice dam, or by meltwater trapped against an ice sheet due to isostatic depression of the crust around t ...

.

Fully recuperated, he returned to Shrewsbury in July 1838. Used to jotting down daily notes on animal breeding, he scrawled rambling thoughts about marriage, career and prospects on two scraps of paper, one with columns headed ''"Marry"'' and ''"Not Marry"''. Advantages under "Marry" included "constant companion and a friend in old age ... better than a dog anyhow", against points such as "less money for books" and "terrible loss of time". Having decided in favour of marriage, he discussed it with his father, then went to visit his cousin Emma on 29 July. At this time he did not get around to proposing, but against his father's advice, he mentioned his ideas on transmutation.

He married Emma on 29 January 1839 and they were the parents of ten children, seven of whom survived to adulthood.