Catholic Church In Ireland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Catholic Church in Ireland, or Irish Catholic Church, is part of the worldwide

The influence of the Irish Church spread back across the

The influence of the Irish Church spread back across the  The oldest surviving Irish Christian

The oldest surviving Irish Christian

One of the major figures associated with the Gregorian Reform in Ireland was Máel Máedóc Ó Morgair, also known as Malachy, who was an Archbishop of Armagh and the first Gaelic Irish saint to undergo a formal canonisation process and official proclamation. Máel Máedóc was closely associated with

One of the major figures associated with the Gregorian Reform in Ireland was Máel Máedóc Ó Morgair, also known as Malachy, who was an Archbishop of Armagh and the first Gaelic Irish saint to undergo a formal canonisation process and official proclamation. Máel Máedóc was closely associated with  Crusading military orders, such as the

Crusading military orders, such as the

"Monastic Ireland: The Mendicant Orders"

History Ireland The first of these to arrive were the

Richard II and the Wider Gaelic World: A Reassessment

Cambridge University Press This was not a doctrinal dispute, but a political one. The

A confusing but defining period arose during the

A confusing but defining period arose during the

In 1879, there was a significant

In 1879, there was a significant

Other outlets issued them freely, accepting donations and, as this was not selling, it was legal; see Contraception in the Republic of Ireland. For comparison, some other countries had a total ban: in the United States, for example, laws in some states prohibited contraception to married couples until the '' Griswold v. Connecticut'' decision in 1965; unmarried couples had to wait until the 1972 ruling '' Eisenstadt v. Baird''. were also resisted; media depictions perceived to be detrimental to public morality were also opposed by Catholics. In addition, the church largely controlled many of the state's hospitals, and most schools, and remained the largest provider of many other social services. At the

. also helped to uphold Catholic hegemony. In both parts of Ireland, church policy and practice changed markedly after the

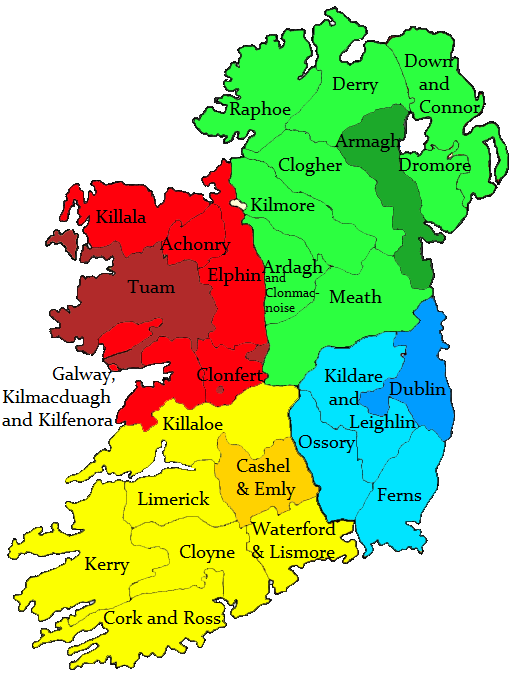

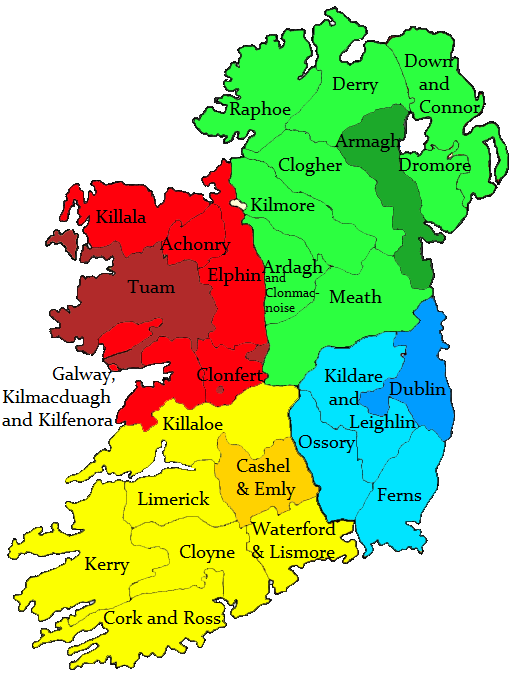

The church is organised into four

The church is organised into four

Catholic Church in Ireland

Irish Bishops' ConferenceCatholicIreland.netCatholic Parish Registers

{{DEFAULTSORT:Catholic Church in Ireland All-Ireland organisations Culture of Ireland

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

in communion with the Holy See

The Holy See (, ; ), also called the See of Rome, the Petrine See or the Apostolic See, is the central governing body of the Catholic Church and Vatican City. It encompasses the office of the pope as the Bishops in the Catholic Church, bishop ...

. With 3.5 million members (in the Republic of Ireland), it is the largest Christian church in Ireland. In the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 Counties of Ireland, counties of the island of Ireland, with a population of about 5.4 million. ...

's 2022 census, 69% of the population identified as Roman Catholic. By contrast, 41% of people in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

identified as Catholic at the 2011 census, increasing to 42.3% in 2021.

The Archbishop of Armagh

The Archbishop of Armagh is an Episcopal polity, archiepiscopal title which takes its name from the Episcopal see, see city of Armagh in Northern Ireland. Since the Reformation in Ireland, Reformation, there have been parallel apostolic success ...

, as the Primate of All Ireland, has ceremonial precedence in the church. The church is administered on an all-Ireland

All-Ireland (sometimes All-Island) is a term used to describe organisations and events whose interests extend over the entire island of Ireland, as opposed to the separate jurisdictions of the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. "All-Irelan ...

basis. The Irish Catholic Bishops' Conference is a consultative body for ordinaries in Ireland.

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

has existed in Ireland since the 5th century and arrived from Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the territory that became the Roman province of ''Britannia'' after the Roman conquest of Britain, consisting of a large part of the island of Great Britain. The occupation lasted from AD 43 to AD 410.

Julius Caes ...

(most famously associated with Saint Patrick

Saint Patrick (; or ; ) was a fifth-century Romano-British culture, Romano-British Christian missionary and Archbishop of Armagh, bishop in Gaelic Ireland, Ireland. Known as the "Apostle of Ireland", he is the primary patron saint of Irelan ...

), forming what is today known as Gaelic Christianity. It gradually gained ground and replaced the old pagan

Paganism (, later 'civilian') is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Christianity, Judaism, and Samaritanism. In the time of the ...

traditions. The Catholic Church in Ireland cites its origin to this period and considers Palladius as the first bishop sent to the Gaels by Pope Celestine I. However, during the 12th century a stricter uniformity in the Western Church was enforced, with the diocesan structure introduced with the Synod of Ráth Breasail

The Synod of Ráth Breasail (or Rathbreasail; ) was a synod of the Catholic Church in Ireland that took place in Ireland in 1111. It marked the transition of the Irish church from a monastic to a diocesan and parish-based church. Many present-day ...

in 1111 and culminating with the Gregorian Reform

The Gregorian Reforms were a series of reforms initiated by Pope Gregory VII and the circle he formed in the papal curia, c. 1050–1080, which dealt with the moral integrity and independence of the clergy. The reforms are considered to be na ...

which coincided with the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland

The Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland took place during the late 12th century, when Anglo-Normans gradually conquered and acquired large swathes of land in Ireland over which the List of English monarchs, monarchs of England then claimed sovere ...

.

After the Tudor conquest of Ireland

Ireland was conquered by the Tudor monarchs of England in the 16th century. The Anglo-Normans had Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland, conquered swathes of Ireland in the late 12th century, bringing it under Lordship of Ireland, English rule. In t ...

, the English Crown

This list of kings and reigning queens of the Kingdom of England begins with Alfred the Great, who initially ruled Wessex, one of the seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms which later made up modern England. Alfred styled himself king of the Anglo-Sax ...

attempted to import the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and ...

into Ireland. The Catholic Church was outlawed and adherents endured oppression

Oppression is malicious or unjust treatment of, or exercise of power over, a group of individuals, often in the form of governmental authority. Oppression may be overt or covert, depending on how it is practiced.

No universally accepted model ...

and severe legal penalties for refusing to conform to the religion established by law — the Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland (, ; , ) is a Christian church in Ireland, and an autonomy, autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the Christianity in Ireland, second-largest Christian church on the ...

. By the 16th century, Irish national identity

National identity is a person's identity or sense of belonging to one or more states or one or more nations. It is the sense of "a nation as a cohesive whole, as represented by distinctive traditions, culture, and language".

National identity ...

coalesced around Irish Catholic

Irish Catholics () are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland, defined by their adherence to Catholic Christianity and their shared Irish ethnic, linguistic, and cultural heritage.The term distinguishes Catholics of Irish descent, particul ...

ism. For several centuries, the Irish Catholic majority were suppressed. In the 19th century, the church and the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

came to a ''rapprochement

In international relations, a rapprochement, which comes from the French word ''rapprocher'' ("to bring together"), is a re-establishment of cordial relations between two countries. This may be done due to a mutual antagonist, as the German Empire ...

''. Funding for Maynooth College

St Patrick's Pontifical University, Maynooth (), is a pontifical Catholic university in the town of Maynooth near Dublin, Ireland. The college and national seminary on its grounds are often referred to as Maynooth College.

The college was of ...

was agreed as was Catholic emancipation to ward off revolutionary republicanism. Following the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising (), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the aim of establishing an ind ...

of 1916 and the creation of the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

, the church gained significant social and political influence. During the late 20th century, a number of sexual abuse scandals involving clerics emerged.

History

Gaels and early Christianity

Duringclassical antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

, the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

conquered most of Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

but never reached Ireland. So when the Edict of Milan

The Edict of Milan (; , ''Diatagma tōn Mediolanōn'') was the February 313 agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Frend, W. H. C. (1965). ''The Early Church''. SPCK, p. 137. Western Roman Emperor Constantine I and ...

in 313 AD allowed tolerance for the Palestinian

Palestinians () are an Arab ethnonational group native to the Levantine region of Palestine.

*: "Palestine was part of the first wave of conquest following Muhammad's death in 632 CE; Jerusalem fell to the Caliph Umar in 638. The indigenous p ...

-originated religion of Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

and then the Edict of Thessalonica

An edict is a decree or announcement of a law, often associated with monarchies, but it can be under any official authority. Synonyms include "dictum" and "pronouncement". ''Edict'' derives from the Latin wikt:edictum#Latin, edictum.

Notable ed ...

in 380 AD enforced it as the state religion of the Empire (which comprised much of Europe - including within the British Isles

The British Isles are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Outer Hebr ...

itself, Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the territory that became the Roman province of ''Britannia'' after the Roman conquest of Britain, consisting of a large part of the island of Great Britain. The occupation lasted from AD 43 to AD 410.

Julius Caes ...

), the indigenous Indo-European pagan traditions of the Gaels

The Gaels ( ; ; ; ) are an Insular Celts, Insular Celtic ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man. They are associated with the Goidelic languages, Gaelic languages: a branch of the Celtic languages comprising ...

in Ireland remained normative. Aside from this independence, Gaelic Ireland was a highly decentralised tribal society, so mass conversion to a new system would prove a drawn-out process when the Christian religion began to gradually move into the island.

There is no tradition of a New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

figure visiting the island. Joseph of Arimathea

Joseph of Arimathea () is a Biblical figure who assumed responsibility for the burial of Jesus after Crucifixion of Jesus, his crucifixion. Three of the four Biblical Canon, canonical Gospels identify him as a member of the Sanhedrin, while the ...

traditionally came to Britain, and Mary Magdalene

Mary Magdalene (sometimes called Mary of Magdala, or simply the Magdalene or the Madeleine) was a woman who, according to the four canonical gospels, traveled with Jesus as one of his followers and was a witness to crucifixion of Jesus, his cr ...

, Martha

Martha (Aramaic language, Aramaic: מָרְתָא) is a Bible, biblical figure described in the Gospels of Gospel of Luke, Luke and Gospel of John, John. Together with her siblings Lazarus of Bethany, Lazarus and Mary of Bethany, she is descr ...

and Lazarus of Bethany

Lazarus of Bethany is a figure of the New Testament whose life is restored by Jesus four days after his death, as told in the Gospel of John. The resurrection is considered one of the miracles of Jesus. In the Eastern Orthodox Church, Lazarus i ...

to France, but none were reputed to have seen Ireland itself. Nevertheless, medieval Gaelic historians - in works such as the ''Lebor Gabála Érenn

''Lebor Gabála Érenn'' (literally "The Book of Ireland's Taking"; Modern Irish spelling: ''Leabhar Gabhála Éireann'', known in English as ''The Book of Invasions'') is a collection of poems and prose narratives in the Irish language inten ...

'' - attempted to link the historical narrative of their people (represented by the proto-Gaelic Scythians

The Scythians ( or ) or Scyths (, but note Scytho- () in composition) and sometimes also referred to as the Pontic Scythians, were an Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Eastern Iranian languages, Eastern Iranian peoples, Iranian Eurasian noma ...

) to Moses

In Abrahamic religions, Moses was the Hebrews, Hebrew prophet who led the Israelites out of slavery in the The Exodus, Exodus from ancient Egypt, Egypt. He is considered the most important Prophets in Judaism, prophet in Judaism and Samaritani ...

in Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

. Specifically, works such as the ''Lebor Gabála Érenn

''Lebor Gabála Érenn'' (literally "The Book of Ireland's Taking"; Modern Irish spelling: ''Leabhar Gabhála Éireann'', known in English as ''The Book of Invasions'') is a collection of poems and prose narratives in the Irish language inten ...

'', ''Book of Ballymote

The ''Book of Ballymote'' (, RIA MS 23 P 12, 275 foll.), was written in 1390 or 1391 in or near the town of Ballymote, now in County Sligo, but then in the tuath of Corann.

According to David Sellar who was the Lord Lyon King of Arms in ...

'' and ''Great Book of Lecan

The ''Great Book of Lecan'' or simply ''Book of Lecan'' () ( RIA, 23 P 2) is a late-medieval Irish manuscript written between 1397 and 1418 in Castle Forbes, Lecan (Lackan, Leckan; Irish ), in the territory of Tír Fhíacrach, near moder ...

'', say that, during the time of Moses, Goídel Glas (the reputed progenitor of the Irish) was bitten in the neck by a snake while in Egypt as a youth. His father, the Scythian prince Níul (husband of Egyptian princess Scota) brought Goídel to the noted wonder-worker, Moses

In Abrahamic religions, Moses was the Hebrews, Hebrew prophet who led the Israelites out of slavery in the The Exodus, Exodus from ancient Egypt, Egypt. He is considered the most important Prophets in Judaism, prophet in Judaism and Samaritani ...

, who healed the boy immediately upon applying his rod to the wound. Moses made a prophecy that no serpent would live in the land of his progeny, and that God promised his descendants a "northern island of the world"; he claimed that “kings and lords, saints and righteous” would come from the seed of Goídel. In some ways, the Gaelic authors of these works sought to present themselves as a kind of "chosen people" while approaching the Biblical narrative, mirroring the Israelites

Israelites were a Hebrew language, Hebrew-speaking ethnoreligious group, consisting of tribes that lived in Canaan during the Iron Age.

Modern scholarship describes the Israelites as emerging from indigenous Canaanites, Canaanite populations ...

. Furthermore, according to the ''Lebor Gabála Érenn'', the lifetime of Jesus Christ

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

was synchronous with the reigns of Eterscél, Nuadu Necht and Conaire Mór

Conaire Mór (the great), son of Eterscél, was, according to mediaeval Irish legend and historical tradition, a High King of Ireland sometime during the 1st century BC or 1st century AD. His mother was Mess Búachalla, who was either the daugh ...

as High Kings of Ireland

High King of Ireland ( ) was a royal title in Gaelic Ireland held by those who had, or who are claimed to have had, lordship over all of Ireland. The title was held by historical kings and was later sometimes assigned anachronously or to leg ...

. In medieval accounts, Conchobar mac Nessa

Conchobar mac Nessa (son of Ness) is the king of Ulster in the Ulster Cycle of Irish mythology. He rules from Emain Macha (Navan Fort, near Armagh). He is usually said to be the son of the High King Fachtna Fáthach, although in some stories ...

, a King of Ulster

The King of Ulster (Old Irish: ''Rí Ulad'', Modern Irish: ''Rí Uladh'') also known as the King of Ulaid and King of the Ulaid, was any of the kings of the Irish provincial over-kingdom of Ulaid. The title rí in Chóicid, which means "king of ...

, was born in the same hour as Christ. Later in life, upon seeing an unexplained " darkening of the skies", Conchobar mac Nessa found out from a that Christ had been crucified, leading to the conversion of Conchobar. However, after hearing the story of the crucifixion, Conchobar became distraught and died. Some accounts claim Conchobar "was the first pagan who went to Heaven in Ireland", as the blood that dripped from his head upon his death baptized him.Accounts actually attribute Conchobar's death to Mesgegra's brain, which had been lodged into Conchobar's skull by Cet mac Mágach. Conchobar's anger once hearing the story of the crucifixion leads to Mesgegra's brain bursting from his head, killing him.

Regardless, the earliest known stages of Christianity in Ireland, generally dated to the 5th century, remain somewhat obscure. Native Christian "pre-Patrician" figures, however, including Ailbe

Saint Ailbe ( ; ), usually known in English as St Elvis ( British/ Welsh), Eilfyw or Eilfw, was regarded as the chief 'pre-Patrician' saint of Ireland (although his death was recorded in the early 6th-century). He was a bishop and later saint.

...

(died 528), Abbán (died ), Ciarán

Ciarán (Irish language, Irish spelling) or Ciaran (Scottish Gaelic spelling) is a traditionally male given name of Irish origin. It means "little dark one" or "little dark-haired one", produced by appending a diminutive suffix to ''ciar'' (" ...

(died ) and Declán (), later venerated as saints

In Christian belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and denomination. In Anglican, Oriental Orth ...

, are known. These figures typically operated in Leinster

Leinster ( ; or ) is one of the four provinces of Ireland, in the southeast of Ireland.

The modern province comprises the ancient Kingdoms of Meath, Leinster and Osraige, which existed during Gaelic Ireland. Following the 12th-century ...

and Munster

Munster ( or ) is the largest of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the south west of the island. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" (). Following the Nor ...

. The early stories of these people mention journeys to Roman Britain, to Roman Gaul

Roman Gaul refers to GaulThe territory of Gaul roughly corresponds to modern-day France, Belgium and Luxembourg, and adjacent parts of the Netherlands, Switzerland and Germany. under provincial rule in the Roman Empire from the 1st century B ...

and even to Rome itself. Indeed, Pope Celestine I is held to have sent Palladius to evangelise the Gaels in 431, though success was limited. Apart from these, the figure most associated with the Christianisation of Ireland is Patrick (Maewyn Succat), a Romano-British

The Romano-British culture arose in Britain under the Roman Empire following the Roman conquest in AD 43 and the creation of the province of Britannia. It arose as a fusion of the imported Roman culture with that of the indigenous Britons, ...

nobleman, who was captured by the Gaels during a raid at a time when the Roman rule in Britain was in decline. Patrick contested with the , targeted the local royalty for conversion, and re-orientated Irish Christianity to having Armagh

Armagh ( ; , , " Macha's height") is a city and the county town of County Armagh, in Northern Ireland, as well as a civil parish. It is the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland – the seat of the Archbishops of Armagh, the Primates of All ...

, an ancient royal site associated with the goddess Macha (an aspect of An Morríghan), as the preeminent seat of power. Much of what is known about Patrick comes from the two Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

works attributed to him: ''Confessio'' and ''Epistola ad Coroticum''. The two earliest lives of Ireland's patron saint emerged in the 7th century, authored by Tírechán

Tírechán was a 7th-century Ireland, Irish bishop from north Connacht, specifically the Killala Bay area, in what is now County Mayo.

Background

Based on a knowledge of Irish customs of the times, historian Terry O’Hagan has concluded that T ...

and Muirchú. Both of these are contained within the ''Book of Armagh

The ''Book of Armagh'' or Codex Ardmachanus (ar or 61) (), also known as the ''Canon of Patrick'' and the ''Liber Ar(d)machanus'', is a 9th-century Irish art, Irish illuminated manuscript written mainly in Latin. It is held by the Library of Tri ...

''.

From its inception in the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages (historiography), Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th to the 10th century. They marked the start o ...

, the Gaelic Church centred around powerful local monasteries, a system which suggests early links with the Coptic Church

The Coptic Orthodox Church (), also known as the Coptic Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria, is an Oriental Orthodox Churches, Oriental Orthodox Christian church based in Egypt. The head of the church and the Apostolic see, See of Alexandria i ...

in Egypt.

The lands on which monasteries were based were known as lands; they held a special tax-exempt status and were places of sanctuary. The spiritual heirs and successors of the saintly founders of these monasteries were known as ''Coarb

A coarb, from the Old Irish ''comarbae'' (Modern Irish: , ), meaning "heir" or "successor", was a distinctive office of the medieval Celtic Church among the Gaels of Ireland and Scotland. In this period coarb appears interchangeable with " erenac ...

s'', and held the right to provide abbots. For example: the Abbot of Armagh was the , the Abbot of Iona was the , the Abbot of Clonmacnoise was the , the Abbot of Glendalough was the , and so on. The larger monasteries had various subordinate monasteries within a particular "family". The position of ''Coarb'', like others in Gaelic culture, was hereditary, held by a particular ecclesiastical with the same paternal bloodline and elected from within a family through tanistry

Tanistry is a Gaelic system for passing on titles and lands. In this system the Tanist (; ; ) is the office of heir-apparent, or second-in-command, among the (royal) Gaelic patrilineal dynasties of Ireland, Scotland and Mann, to succeed to ...

(usually protected by the local Gaelic king). This was the same system used for the selection of kings, standard-bearers, bardic poets and other hereditary roles. ''Erenagh

The medieval Irish office of erenagh (Old Irish: ''airchinnech'', Modern Irish: ''airchinneach'', Latin: '' princeps'') was responsible for receiving parish revenue from tithes and rents, building and maintaining church property and overseeing t ...

'' were the hereditary stewards of the lands of a monastery. Monks also founded monasteries on smaller islands around Ireland, for instance Finnian at Skellig Michael, Senán at Inis Cathaigh and Columba at Iona. As well as this, Brendan was known for his offshore "voyage" journeys and the mysterious Saint Brendan's Island.

The influence of the Irish Church spread back across the

The influence of the Irish Church spread back across the Irish Sea

The Irish Sea is a body of water that separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is linked to the Celtic Sea in the south by St George's Channel and to the Inner Seas off the West Coast of Scotland in the north by the North Ch ...

to Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

. Dál Riata

Dál Riata or Dál Riada (also Dalriada) () was a Gaels, Gaelic Monarchy, kingdom that encompassed the Inner Hebrides, western seaboard of Scotland and north-eastern Ireland, on each side of the North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland), North ...

in what is now Argyll

Argyll (; archaically Argyle; , ), sometimes called Argyllshire, is a Shires of Scotland, historic county and registration county of western Scotland. The county ceased to be used for local government purposes in 1975 and most of the area ...

in Scotland was geopolitically continuous with Ireland, and Iona held an important place in Irish Christianity, with Columban monastic activities either side of the North Channel. From here, Irish missionaries converted the pagan northern Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples in what is now Scotland north of the Firth of Forth, in the Scotland in the early Middle Ages, Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and details of their culture can be gleaned from early medieval texts and Pic ...

of Fortriu

Fortriu (; ; ; ) was a Pictish kingdom recorded between the 4th and 10th centuries. It was traditionally believed to be located in and around Strathearn in central Scotland, but is more likely to have been based in the north, in the Moray and ...

. They were also esteemed at the court of the premier Angle

In Euclidean geometry, an angle can refer to a number of concepts relating to the intersection of two straight Line (geometry), lines at a Point (geometry), point. Formally, an angle is a figure lying in a Euclidean plane, plane formed by two R ...

-kingdom of the time, Northumbria

Northumbria () was an early medieval Heptarchy, kingdom in what is now Northern England and Scottish Lowlands, South Scotland.

The name derives from the Old English meaning "the people or province north of the Humber", as opposed to the Sout ...

, with Aidan from Iona founding a monastery at Lindisfarne

Lindisfarne, also known as Holy Island, is a tidal island off the northeast coast of England, which constitutes the civil parishes in England, civil parish of Holy Island in Northumberland. Holy Island has a recorded history from the 6th centu ...

in 634, converting Northumbrians to Christianity (the Northumbrians in turn converted Mercia

Mercia (, was one of the principal kingdoms founded at the end of Sub-Roman Britain; the area was settled by Anglo-Saxons in an era called the Heptarchy. It was centred on the River Trent and its tributaries, in a region now known as the Midlan ...

). Surviving artifacts such as the ''Lindisfarne Gospels

The Lindisfarne Gospels (London, British Library Cotton MS Nero D.IV) is an illuminated manuscript gospel book probably produced around the years 715–720 in the monastery at Lindisfarne, off the coast of Northumberland, which is now in the Bri ...

'', share the same insular art

Insular art, also known as Hiberno-Saxon art, was produced in the sub-Roman Britain, post-Roman era of Great Britain and Ireland. The term derives from ''insula'', the Latin language, Latin term for "island"; in this period Britain and Ireland ...

-style with the '' Stowe Missal'' and ''Book of Kells

The Book of Kells (; ; Dublin, Trinity College Library, MS A. I. 8 sometimes known as the Book of Columba) is an illustrated manuscript and Celts, Celtic Gospel book in Latin, containing the Gospel, four Gospels of the New Testament togeth ...

''. By the 7th century, rivalries between Hibernocentric-Lindisfarne and Kentish-Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, in the county of Kent, England; it was a county borough until 1974. It lies on the River Stour, Kent, River Stour. The city has a mild oceanic climat ...

emerged within the Heptarchy

The Heptarchy was the division of Anglo-Saxon England between the sixth and eighth centuries into petty kingdoms, conventionally the seven kingdoms of East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Mercia, Northumbria, Sussex, and Wessex. The term originated wi ...

, with the latter established by the mission of Roman-born Augustine of Canterbury

Augustine of Canterbury (early 6th century in England, 6th century – most likely 26 May 604) was a Christian monk who became the first archbishop of Canterbury in the year 597. He is considered the "Apostle to the English".

Augustine ...

in 597. Customs of the Irish Church which differed, such as the calculation of the date of Easter and the Gaelic monks' manner of tonsure

Tonsure () is the practice of cutting or shaving some or all of the hair on the scalp as a sign of religious devotion or humility. The term originates from the Latin word ' (meaning "clipping" or "shearing") and referred to a specific practice in ...

were highlighted. The discrepancies were resolved in southern Ireland with Clonfert

Clonfert () is a small village in east County Galway, Ireland, halfway between Ballinasloe and Portumna. The village gives its name to the Diocese of Clonfert (Roman Catholic), Diocese of Clonfert. Clonfert Cathedral is one of the eight cathedr ...

replying to Pope Honorius I

Pope Honorius I (died 12 October 638) was the bishop of Rome from 27 October 625 to his death on 12 October 638. He was active in spreading Christianity among Anglo-Saxons and attempted to convince the Celts to calculate Easter in the Roman fa ...

with the ''Letter of Cumméne Fota

Cumméne Fota or Fada, anglicised Cummian (''fl''. ''c''. 591 – 12 November 661 or 662), was an Irish bishop and ''fer léignid'' ( lector) of ''Cluain Ferta Brénainn'' (Clonfert). He was an important theological writer in the early to mid ...

'', around 626-628. After a separate dialogue with Rome, Armagh followed in 692. The Columbans of Iona proved the most resistant of the Irish, holding out until the early 700s, though their satellite Lindisfarne was pressured into changing at the Synod of Whitby

The Synod of Whitby was a Christianity, Christian administrative gathering held in Northumbria in 664, wherein King Oswiu ruled that his kingdom would calculate Easter and observe the monastic tonsure according to the customs of Roman Catholic, Ro ...

in 664, partly due to an internal political struggle.Retroactively, Protestants would point to this controversy to suggest the existence of a proto-Protestant "Celtic Church

Celtic Christianity is a form of Christianity that was common, or held to be common, across the Celtic-speaking world during the Early Middle Ages. The term Celtic Church is deprecated by many historians as it implies a unified and identifiab ...

" or "British Church" independent from Rome in the Early Middle Ages as part of their historiography

Historiography is the study of the methods used by historians in developing history as an academic discipline. By extension, the term ":wikt:historiography, historiography" is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiog ...

. However, during the dispute over the dating of Easter, the primacy of the Bishop of Rome, Catholic doctrine, liturgical practice (see Hiberno-Latin) or the sacraments—issues of importance to Protestants—were not under question. The longest holdouts were the Cornish Britons of Dumnonia

Dumnonia is the Latinised name for a Brythonic kingdom that existed in Sub-Roman Britain between the late 4th and late 8th centuries CE in the more westerly parts of present-day South West England. It was centred in the area of modern Devon, ...

, as part of their conflict with Wessex

The Kingdom of the West Saxons, also known as the Kingdom of Wessex, was an Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy, kingdom in the south of Great Britain, from around 519 until Alfred the Great declared himself as King of the Anglo-Saxons in 886.

The Anglo-Sa ...

. Indeed, the Cornish had been converted by Irish missionaries: the Cornish patron saint Piran

Piran (; ) is a town in southwestern Slovenia on the Gulf of Piran on the Adriatic Sea. It is one of the three major towns of Slovenian Istria. A bilingual city, with population speaking both Slovene and Italian, Piran is known for its medieva ...

(also known as Ciarán

Ciarán (Irish language, Irish spelling) or Ciaran (Scottish Gaelic spelling) is a traditionally male given name of Irish origin. It means "little dark one" or "little dark-haired one", produced by appending a diminutive suffix to ''ciar'' (" ...

) and a nun, princess Ia, who gave her name to St. Ives, were foremost. As well as Ia, there were also female saints in Ireland during the early period, such as Brigid

Brigid or Brigit ( , ; meaning 'exalted one'),Campbell, MikBehind the Name.See also Xavier Delamarre, ''brigantion / brigant-'', in ''Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise'' (Éditions Errance, 2003) pp. 87–88: "Le nom de la sainte irlandaise ''B ...

of Kildare

Kildare () is a town in County Kildare, Ireland. , its population was 10,302, making it the 7th largest town in County Kildare. It is home to Kildare Cathedral, historically the site of an important abbey said to have been founded by Saint ...

and Íte of Killeedy

Íte ingen Chinn Fhalad (died 570–577), also known as Íde, Ita, Ida or Ides, was an early Irish nun and patron saint of Killeedy (Cluain Creadhail). She was known as the "foster mother of the saints of Erin". The name "Ita" ("thirst for ho ...

.

The oldest surviving Irish Christian

The oldest surviving Irish Christian liturgical

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and participation in the sacred through activities reflecting praise, thanksgiving, remembra ...

text is the '' Antiphonary of Bangor'' from the 7th century. Indeed, at Bangor, a saint by the name of Columbanus

Saint Columbanus (; 543 – 23 November 615) was an Irish missionary notable for founding a number of monasteries after 590 in the Frankish and Lombard kingdoms, most notably Luxeuil Abbey in present-day France and Bobbio Abbey in presen ...

developed his ''Rule of St. Columbanus''. Strongly penetential in nature, this Rule played a seminal role in the formalisation of the Sacrament of Confession

The Sacrament of Penance (also commonly called the Sacrament of Reconciliation or Confession) is one of the seven sacraments of the Catholic Church (known in Eastern Christianity as sacred mysteries), in which the faithful are absolved from s ...

in the Catholic Church. The zeal and piety of the Church in Ireland during the 6th and 7th centuries was such that many monks, including Columbanus and his companions, went as missionaries to Continental Europe, especially to the Merovingian

The Merovingian dynasty () was the ruling family of the Franks from around the middle of the 5th century until Pepin the Short in 751. They first appear as "Kings of the Franks" in the Roman army of northern Gaul. By 509 they had united all the ...

and Carolingian

The Carolingian dynasty ( ; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family named after Charles Martel and his grandson Charlemagne, descendants of the Arnulfing and Pippinid c ...

Frankish Empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–887) was a Frankish-dominated empire in Western and Central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the Lomba ...

. Notable establishments founded by the Irish Christians included Luxeuil Abbey (founded ) in Burgundy

Burgundy ( ; ; Burgundian: ''Bregogne'') is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. ...

, Bobbio Abbey (founded in 614) in Lombardy

The Lombardy Region (; ) is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in northern Italy and has a population of about 10 million people, constituting more than one-sixth of Italy's population. Lombardy is ...

, the Abbey of Saint Gall

The Abbey of Saint Gall () is a dissolved abbey (747–1805) in a Catholic religious complex in the city of St. Gallen in Switzerland. The Carolingian-era monastery existed from 719, founded by Saint Othmar on the spot where Saint Gall had er ...

(founded in the 8th century) in present-day Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

and Disibodenberg Abbey (founded ) near Odernheim am Glan. These Columbanian monasteries were great places of learning, with substantial libraries; these became centres of resistance to the heresy of Arianism

Arianism (, ) is a Christology, Christological doctrine which rejects the traditional notion of the Trinity and considers Jesus to be a creation of God, and therefore distinct from God. It is named after its major proponent, Arius (). It is co ...

. Later, the ''Rule of St. Columbanus'' was supplanted by the "softer" ''Rule of St. Benedict

The ''Rule of Saint Benedict'' () is a book of precepts written in Latin by Benedict of Nursia, St. Benedict of Nursia (c. AD 480–550) for monks living communally under the authority of an abbot.

The spirit of Saint Benedict's Rule is summed up ...

''. The ascetic nature of Gaelic monasticism has been linked to the Desert Fathers

The Desert Fathers were early Christian hermits and ascetics, who lived primarily in the Wadi El Natrun, then known as ''Skete'', in Roman Egypt, beginning around the Christianity in the ante-Nicene period, third century. The ''Sayings of the Dese ...

of Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

.

Martin of Tours

Martin of Tours (; 316/3368 November 397) was the third bishop of Tours. He is the patron saint of many communities and organizations across Europe, including France's Third French Republic, Third Republic. A native of Pannonia (present-day Hung ...

(died 397) and John Cassian

John Cassian, also known as John the Ascetic and John Cassian the Roman (, ''Ioannes Cassianus'', or ''Ioannes Massiliensis''; Greek: Ίωάννης Κασσιανός ό Ερημίτης; – ), was a Christian monk and theologian celebrated ...

( – ) were significant influences.

Gregorian Reform and Norman influence

Within the Catholic Church, theGregorian Reform

The Gregorian Reforms were a series of reforms initiated by Pope Gregory VII and the circle he formed in the papal curia, c. 1050–1080, which dealt with the moral integrity and independence of the clergy. The reforms are considered to be na ...

took place during the 11th century, which reformed the administration of the Roman Rite

The Roman Rite () is the most common ritual family for performing the ecclesiastical services of the Latin Church, the largest of the ''sui iuris'' particular churches that comprise the Catholic Church. The Roman Rite governs Rite (Christianity) ...

to a more centralised model and closely enforced disciplines such as the struggle against simony

Simony () is the act of selling church offices and roles or sacred things. It is named after Simon Magus, who is described in the Acts of the Apostles as having offered two disciples of Jesus payment in exchange for their empowering him to imp ...

, marriage irregularities and in favour of clerical celibacy

Clerical celibacy is the requirement in certain religions that some or all members of the clergy be unmarried. Clerical celibacy also requires abstention from deliberately indulging in sexual thoughts and behavior outside of marriage, because thes ...

. This was in the aftermath of the East–West Schism

The East–West Schism, also known as the Great Schism or the Schism of 1054, is the break of communion (Christian), communion between the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church. A series of Eastern Orthodox – Roman Catholic eccle ...

between the Catholic Church in the West and the Orthodox Church in the East. These Roman reforms reached Ireland with three or four significant synods: the First Synod of Cashel (1101) was called by Muirchertach Ó Briain, the High King of Ireland

High King of Ireland ( ) was a royal title in Gaelic Ireland held by those who had, or who are claimed to have had, lordship over all of Ireland. The title was held by historical kings and was later sometimes assigned anachronously or to leg ...

and King of Munster

The kings of Munster () ruled the Kingdom of Munster in Ireland from its establishment during the Irish Iron Age until the High Middle Ages. According to Gaelic traditional history, laid out in works such as the ''Book of Invasions'', the earli ...

, held at the Rock of Cashel

The Rock of Cashel ( ), also known as Cashel of the Kings and St. Patrick's Rock, is a historical site located dramatically above a plain at Cashel, County Tipperary, Cashel, County Tipperary, Republic of Ireland, Ireland.

History

According t ...

with Máel Muire Ó Dúnáin as papal legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the Pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title '' legatus'') is a personal representative of the Pope to foreign nations, to some other part of the Catho ...

, affirming many of these disciplines. This was followed by the Synod of Ráth Breasail

The Synod of Ráth Breasail (or Rathbreasail; ) was a synod of the Catholic Church in Ireland that took place in Ireland in 1111. It marked the transition of the Irish church from a monastic to a diocesan and parish-based church. Many present-day ...

(1111), called by the High King with Giolla Easpaig as the papal legate (he had been an associate of Anselm of Aosta), which moved the administration of the Church in Ireland from a monastic-centered model to a diocesan-centered one, with two provinces at Armagh and Cashel established, with twelve territorial dioceses under the Archbishop of Armagh

The Archbishop of Armagh is an Episcopal polity, archiepiscopal title which takes its name from the Episcopal see, see city of Armagh in Northern Ireland. Since the Reformation in Ireland, Reformation, there have been parallel apostolic success ...

and Archbishop of Cashel

The Archbishop of Cashel () was an archiepiscopal title which took its name after the town of Cashel, County Tipperary in Ireland. Following the Reformation, there had been parallel apostolic successions to the title: one in the Catholic Church ...

respectively. It also brought Waterford under Cashel, as the Norsemen had previously looked to the Province of Canterbury

The Province of Canterbury, or less formally the Southern Province, is one of two ecclesiastical provinces which constitute the Church of England. The other is the Province of York (which consists of 12 dioceses).

Overview

The Province consi ...

. Cellach of Armagh

Cellach of Armagh or Celsus or Celestinus (1080–1129) was Archbishop of Armagh and an important contributor to the reform of the Irish church in the twelfth century. He is venerated in the Roman Catholic Church as Saint Cellach. Though a ...

, the "Coarb

A coarb, from the Old Irish ''comarbae'' (Modern Irish: , ), meaning "heir" or "successor", was a distinctive office of the medieval Celtic Church among the Gaels of Ireland and Scotland. In this period coarb appears interchangeable with " erenac ...

Pádraig", was present and recognised with the new title as Archbishop of Armagh, which was given the Primacy of Ireland.

One of the major figures associated with the Gregorian Reform in Ireland was Máel Máedóc Ó Morgair, also known as Malachy, who was an Archbishop of Armagh and the first Gaelic Irish saint to undergo a formal canonisation process and official proclamation. Máel Máedóc was closely associated with

One of the major figures associated with the Gregorian Reform in Ireland was Máel Máedóc Ó Morgair, also known as Malachy, who was an Archbishop of Armagh and the first Gaelic Irish saint to undergo a formal canonisation process and official proclamation. Máel Máedóc was closely associated with Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard of Clairvaux, Cistercians, O.Cist. (; 109020 August 1153), venerated as Saint Bernard, was an abbot, Mysticism, mystic, co-founder of the Knights Templar, and a major leader in the reform of the Benedictines through the nascent Cistercia ...

and introduced his Cistercian

The Cistercians (), officially the Order of Cistercians (, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint Benedict, as well as the contri ...

order from France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

into Ireland with the foundation of Mellifont Abbey

Mellifont Abbey (, literally 'the Big Monastery'), was a Cistercians, Cistercian abbey located close to Drogheda in County Louth, Ireland. It was the first abbey of the order to be built in Ireland. In 1152, it hosted the Synod of Kells-Mellifo ...

in 1142. He had visited Pope Innocent II

Pope Innocent II (; died 24 September 1143), born Gregorio Papareschi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 14 February 1130 to his death in 1143. His election as Pope was controversial, and the first eight years o ...

in Rome to discuss implementing reforms. It was in association with these foundations that the Synod of Kells-Mellifont

The Synod of Kells (, ) took place in 1152, under the presidency of Giovanni Cardinal Paparoni, and continued the process begun at the Synod of Ráth Breasail (1111) of reforming the Irish church. The sessions were divided between the abbeys o ...

(1152) took place. Malachy had died a few years previously and so Cardinal Giovanni Paparoni Giovanni Cardinal Paparoni (sometimes known in English as John Cardinal Paparo; died ca. 1153/1154) was an Italian Cardinal and prominent papal legate in dealings with Ireland and Scotland.

He was created Cardinal by Pope Celestine II in 1143. Fo ...

was present as papal legate for Pope Eugene III

Pope Eugene III (; c. 1080 – 8 July 1153), born Bernardo Pignatelli, or possibly Paganelli, called Bernardo da Pisa, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 15 February 1145 to his death in 1153. He was the first Cist ...

. It rejected Canterbury's pretentions of primacy over the Irish Church. This created two more Provinces and Archbishops, with an Archbishop of Dublin

The Archbishop of Dublin () is an Episcopal polity, archiepiscopal title which takes its name from Dublin, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Since the Reformation in Ireland, Reformation, there have been parallel apostolic successions to the title: ...

and an Archbishop of Tuam

The Archbishop of Tuam ( ; ) is an Episcopal polity, archbishop which takes its name after the town of Tuam in County Galway, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The title was used by the Church of Ireland until 1839, and is still in use by the Cathol ...

added. Tuam was established in acknowledgement of the political rise of Connacht, with the High King being Toirdhealbhach Ó Conchobhair. Another major figure associated with this Reform was Lorcán Ó Tuathail, Archbishop of Dublin who founded Christ Church at Dublin under the Reformed Augustinians.

Due to the influential hagiography, the ''Life of Saint Malachy'', authored by Bernard of Clairvaux, with a strongly Reformist Cistercian zeal, the view that the Gaelic Irish Christians were "savages", "barbarian" or "semi-pagan"; due to their difference in church discipline and organisation and despite a reform already underway under the native high kings; found a wide footing in Western Europe. In 1155, John of Salisbury, Secretary to the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

(then Theobald of Bec

Theobald of Bec ( c. 1090 – 18 April 1161) was a Norman archbishop of Canterbury from 1139 to 1161. His exact birth date is unknown. Some time in the late 11th or early 12th century Theobald became a monk at the Abbey of Bec, r ...

), visited Benevento

Benevento ( ; , ; ) is a city and (municipality) of Campania, Italy, capital of the province of Benevento, northeast of Naples. It is situated on a hill above sea level at the confluence of the Calore Irpino (or Beneventano) and the Sabato (r ...

where the first English Pontiff, Pope Adrian IV

Pope Adrian (or Hadrian) IV (; born Nicholas Breakspear (or Brekespear); 1 September 1159) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 4 December 1154 until his death in 1159. Born in England, Adrian IV was the first Pope ...

(Nicholas Breakspear) was reigning. Here, he spoke of the need for reform for the Church in Ireland, requesting that this be overseen by the King of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with their powers Constitutional monarchy, regula ...

, then Henry II Plantagenet, who would have the right to invade and rule Ireland. Adrian IV published the Papal bull ''Laudabiliter

was a papal bull, bull issued in 1155 by Pope Adrian IV, the only Englishman to have served in that office. Existence of the bull has been disputed by scholars over the centuries; no copy is extant but scholars cite the many references to it a ...

'' giving permission for this proposal. This was not acted on immediately or made public, partly due to the king's own problems with the church (i.e. the murder of Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket (), also known as Saint Thomas of Canterbury, Thomas of London and later Thomas à Becket (21 December 1119 or 1120 – 29 December 1170), served as Lord Chancellor from 1155 to 1162, and then as Archbishop of Canterbury fr ...

) and his mother Empress Matilda

Empress Matilda (10 September 1167), also known as Empress Maud, was one of the claimants to the English throne during the civil war known as the Anarchy. The daughter and heir of Henry I, king of England and ruler of Normandy, she went to ...

being opposed to him acting on it. The Normans

The Normans (Norman language, Norman: ''Normaunds''; ; ) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norsemen, Norse Viking settlers and locals of West Francia. The Norse settlements in West Franc ...

had conquered England around century earlier and now due to internal political rivalries within Gaelic Ireland, began to invade Ireland in 1169, under Strongbow, ostensibly to restore the King of Leinster. Fearful that the Norman barons would set up their own rival Kingdom and wanting Ireland himself, Henry II landed at Waterford

Waterford ( ) is a City status in Ireland, city in County Waterford in the South-East Region, Ireland, south-east of Ireland. It is located within the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster. The city is situated at the head of Waterford H ...

in 1171, under the authority of ''Laudabiliter'' (ratified by Pope Alexander III

Pope Alexander III (c. 1100/1105 – 30 August 1181), born Roland (), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 7 September 1159 until his death in 1181.

A native of Siena, Alexander became pope after a Papal election, ...

). Once established, he held the Second Synod of Cashel

The Synod of Cashel of 1172 in Ireland, 1172, also known as the Second Synod of Cashel,The first being the Synod held at Cashel in 1101 in Ireland, 1101. was assembled at Cashel, County Tipperary, Cashel at the request of Henry II of England short ...

(1172). The synod, ignored in the Irish annals

A number of Irish annals, of which the earliest was the Chronicle of Ireland, were compiled up to and shortly after the end of the 17th century. Annals were originally a means by which monks determined the yearly chronology of feast days. Over ti ...

, is known from the writings of Gerald of Wales

Gerald of Wales (; ; ; ) was a Cambro-Norman priest and historian. As a royal clerk to the king and two archbishops, he travelled widely and wrote extensively. He studied and taught in France and visited Rome several times, meeting the Pope. He ...

, the anti-Gaelic Norman who authored ''Expugnatio Hibernica'' (1189). Three of the four Irish Archbishops are said to have attended, with Armagh not present due to infirmity but supportive. It relisted most of the Reforms already approached before and included a tithe

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Modern tithes are normally voluntary and paid in money, cash, cheques or v ...

to be paid to the parish and that "divine matters" in the Irish Church should be conducted along the lines observed by the English Church. In the following years, Norman-descended churchmen would now play a direct role within the Irish Church as the political Lordship of Ireland

The Lordship of Ireland (), sometimes referred to retrospectively as Anglo-Norman Ireland, was the part of Ireland ruled by the King of England (styled as "Lord of Ireland") and controlled by loyal Anglo-Norman Lords between 1177 and 1542. T ...

was established, though many Gaelic kingdoms and their dioceses remained too.

Crusading military orders, such as the

Crusading military orders, such as the Knights Templar

The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, mainly known as the Knights Templar, was a Military order (religious society), military order of the Catholic Church, Catholic faith, and one of the most important military ord ...

and Knights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem, commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), is a Catholic military order. It was founded in the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem in the 12th century and had headquarters there ...

had a presence in Ireland, mostly, though not exclusively, in the Norman areas. The Templars had their Principal at Clontarf Castle until their suppression in 1308 and received land grants from various patrons; from the de Laceys, Butlers, Taffes, FitzGeralds and even O'Mores. Their Master in Ireland was part of the administration of the Lordship of Ireland. The Hospitallers (later known as the Knights of Malta

The Sovereign Military Order of Malta (SMOM), officially the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta, and commonly known as the Order of Malta or the Knights of Malta, is a Catholic Church, Cathol ...

) had their Priory at Kilmainham and various preceptories in Ireland. They took over Templar properties and continued throughout the Medieval period. During the 13th century, the mendicant orders

Mendicant orders are primarily certain Catholic Church, Catholic religious orders that have vowed for their male members a lifestyle of vow of poverty, poverty, traveling, and living in urban areas for purposes of preacher, preaching, Evangelis ...

began to operate within Ireland and 89 friaries were established during this period.Gandharva, Joshi. (2021)"Monastic Ireland: The Mendicant Orders"

History Ireland The first of these to arrive were the

Order of Preachers

The Order of Preachers (, abbreviated OP), commonly known as the Dominican Order, is a Catholic mendicant order of pontifical right that was founded in France by a Castilian priest named Dominic de Guzmán. It was approved by Pope Honorius ...

(also known as the Dominicans), they first established a branch at Dublin in 1224, shortly followed by one at Drogheda the same year, before spreading further. Prominent examples of Dominican establishments from this era are Black Abbey in Kilkenny

Kilkenny ( , meaning 'church of Cainnech of Aghaboe, Cainnech'). is a city in County Kilkenny, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is located in the South-East Region, Ireland, South-East Region and in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinst ...

and Sligo Abbey. Their biggest rivals, the Order of Friars Minor

The Order of Friars Minor (commonly called the Franciscans, the Franciscan Order, or the Seraphic Order; Post-nominal letters, postnominal abbreviation OFM) is a Mendicant orders, mendicant Catholic religious order, founded in 1209 by Francis ...

(also known as the Franciscans) arrived at around the same time, either 1224 or 1226, with their first establishment at Youghal

Youghal ( ; ) is a seaside resort town in County Cork, Ireland. Located on the estuary of the Munster Blackwater, River Blackwater, the town is a former military and economic centre. Located on the edge of a steep riverbank, the town has a long ...

. The Ennis Friary and Roscrea Friary

Roscrea Friary () is a ruined medieval Franciscan friary and National Monument (Ireland), National Monument in Roscrea, County Tipperary, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is on Abbey Street, in the west end of Roscrea, on the north bank of the Ri ...

in Thomond founded by the O'Briens are other prominent Franciscan examples. The Carmelites

The Order of the Brothers of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mount Carmel (; abbreviated OCarm), known as the Carmelites or sometimes by synecdoche known simply as Carmel, is a mendicant order in the Catholic Church for both men and women. Histo ...

arrived next in 1271, followed by the Augustinians

Augustinians are members of several religious orders that follow the Rule of Saint Augustine, written about 400 A.D. by Augustine of Hippo. There are two distinct types of Augustinians in Catholic religious orders dating back to the 12th–13 ...

. Within these orders, as demonstrated by the Franciscans in particular, there was often a strong ethnic conflict between the native Irish Gaels

The Gaels ( ; ; ; ) are an Insular Celts, Insular Celtic ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man. They are associated with the Goidelic languages, Gaelic languages: a branch of the Celtic languages comprising ...

and the Normans

The Normans (Norman language, Norman: ''Normaunds''; ; ) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norsemen, Norse Viking settlers and locals of West Francia. The Norse settlements in West Franc ...

.

During the Western Schism

The Western Schism, also known as the Papal Schism, the Great Occidental Schism, the Schism of 1378, or the Great Schism (), was a split within the Catholic Church lasting from 20 September 1378 to 11 November 1417, in which bishops residing ...

which lasted from 1378 to 1417, within which there were at least two claimants to the Papacy (one in Rome and one in Avignon

Avignon (, , ; or , ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the Communes of France, commune had a ...

), different factions within Gaelic Ireland

Gaelic Ireland () was the Gaelic political and social order, and associated culture, that existed in Ireland from the late Prehistory of Ireland, prehistoric era until the 17th century. It comprised the whole island before Anglo-Norman invasi ...

disagreed on whom to support.Egan, Simon. (2018)Richard II and the Wider Gaelic World: A Reassessment

Cambridge University Press This was not a doctrinal dispute, but a political one. The

Plantagenet

The House of Plantagenet ( /plænˈtædʒənət/ ''plan-TAJ-ə-nət'') was a royal house which originated from the French county of Anjou. The name Plantagenet is used by modern historians to identify four distinct royal houses: the Angev ...

-controlled Lordship of Ireland followed the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from the late 9th century, when it was unified from various Heptarchy, Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland to f ...

in backing the Pope in Rome. Meanwhile, there were two main power blocs among the Gaelic kingdoms and Gaelicised lordships supporting different contenders. The ''Donn'' faction, led by the O'Neill of Tyrone, O'Brien of Thomond, Burke of Clanrickard and O'Connor Donn of Roscommon

The O'Conor dynasty (Middle Irish: ''Ó Conchobhair''; Modern ) are an Irish noble dynasty and formerly one of the most influential and distinguished royal dynasties in Ireland. The O'Conor family held the throne of the Kingdom of Connacht up ...

supported Rome. Through the agency of the Earl of Ormond, they had been loosely allied to Richard II of England

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward the Black Prince, Edward, Prince of Wales (later known as the Black Prince), and Jo ...

when he made an expedition to Ireland in 1394–95. Secondly, there was the ''Ruadh'' faction, led by the O'Donnell of Tyrconnell

The O'Donnell dynasty ( or ''Ó Domhnaill,'' ''Ó Doṁnaill'' ''or Ua Domaill;'' meaning "descendant of Dónal") were the dominant Irish clan of the kingdom of Tyrconnell in Ulster in the north of History of Ireland (1169–1536), medieval an ...

, Burke of Mayo and O'Connor Ruadh of Roscommon; from 1406, they were joined by the O'Neill of Clannaboy. This alternative power faction backed the Avignon antipapacy and were more closely allied to the Stewart-controlled Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland was a sovereign state in northwest Europe, traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a Anglo-Sc ...

. The situation was finally resolved by the Council of Constance

The Council of Constance (; ) was an ecumenical council of the Catholic Church that was held from 1414 to 1418 in the Bishopric of Constance (Konstanz) in present-day Germany. This was the first time that an ecumenical council was convened in ...

of 1414–1418 with full reunification of the church.

Counter-Reformation and suppression

A confusing but defining period arose during the

A confusing but defining period arose during the English Reformation

The English Reformation began in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away first from the authority of the pope and bishops Oath_of_Supremacy, over the King and then from some doctrines and practices of the Catholic Church ...

in the 16th century, with monarchs alternately for or against papal supremacy

Papal supremacy is the doctrine of the Catholic Church that the Pope, by reason of his office as Vicar of Christ, the visible source and foundation of the unity both of the bishops and of the whole company of the faithful, and as priest of the ...

. When on the death of Queen Mary in 1558, the church in England and Ireland broke away completely from the papacy, all but two of the bishops of the church in Ireland followed the decision. Very few of the local clergy led their congregations to follow. The new body became the established state church, which was grandfathered in the possession of most church property. This allowed the Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland (, ; , ) is a Christian church in Ireland, and an autonomy, autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the Christianity in Ireland, second-largest Christian church on the ...

to retain a great repository of religious architecture and other religious items, some of which were later destroyed in subsequent wars. A substantial majority of the population remained Catholic, despite the political and economic advantages of membership in the state church. Despite its numerical minority, however, the Church of Ireland remained the official state church for almost 300 years until it was disestablished on 1 January 1871 by the Irish Church Act 1869 that was passed by Gladstone's Liberal government.

The effect of the Act of Supremacy 1558

The Act of Supremacy 1558 ( 1 Eliz. 1. c. 1), sometimes referred to as the Act of Supremacy 1559, is an act of the Parliament of England, which replaced the original Act of Supremacy 1534 ( 26 Hen. 8. c. 1), and passed under the auspices of E ...

and the papal bull

A papal bull is a type of public decree, letters patent, or charter issued by the pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the leaden Seal (emblem), seal (''bulla (seal), bulla'') traditionally appended to authenticate it.

History

Papal ...

of 1570 ( Regnans in Excelsis) legislated that the majority population of both kingdoms to be governed by an Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

ascendancy. After the defeat of King James II of the Three Kingdoms in 1690, the Test Acts were introduced which began a long era of discrimination against the recusant Catholics of the kingdoms.

Between emancipation and the revolution

The slow process of reform from 1778 on led to Catholic emancipation in 1829. By 1800 Ireland was a part of the newly createdUnited Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the union of the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland into one sovereign state, established by the Acts of Union 1800, Acts of Union in 1801. It continued in this form until ...

. As part of the Kingdom of Ireland

The Kingdom of Ireland (; , ) was a dependent territory of Kingdom of England, England and then of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain from 1542 to the end of 1800. It was ruled by the monarchs of England and then List of British monarchs ...

(''de facto'' Independent after the Constitution of 1782), St Patrick's College, Maynooth

St Patrick's Pontifical University, Maynooth (), is a pontifical Catholic university in the town of Maynooth near Dublin, Ireland

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mou ...

was founded as a national seminary for Ireland with the Maynooth College Act 1795 (prior to this, from the time of Protestant persecutions beginning until around the time of the French Revolution, Irish priests underwent formation in Continental Europe). The Maynooth Grant of 1845, whereby the British government attempted to engender good will to Catholic Ireland became a political controversy with the Anti-Maynooth Conference group founded by anti-Catholics.

In 1835, Fr. John Spratt, an Irish Carmelite

The Order of the Brothers of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mount Carmel (; abbreviated OCarm), known as the Carmelites or sometimes by synecdoche known simply as Carmel, is a mendicant order in the Catholic Church for both men and women. Histo ...

visited Rome and was given by Pope Gregory XVI

Pope Gregory XVI (; ; born Bartolomeo Alberto Cappellari; 18 September 1765 – 1 June 1846) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 2 February 1831 to his death in June 1846. He had adopted the name Mauro upon enteri ...

, the relics and the remains of St. Valentine (whose feast is St. Valentine's Day

Valentine's Day, also called Saint Valentine's Day or the Feast of Saint Valentine, is celebrated annually on February 14. It originated as a Christian feast day honoring a Christian martyrs, martyr named Saint Valentine, Valentine, and ...

), a Roman 3rd century Christian martyr, which Spratt brought back to Whitefriar Street Carmelite Church

Whitefriar Street Carmelite Church is a Roman Catholic church in Dublin, Ireland maintained by the Carmelite order. The church is noted for having the relics of Saint Valentine, which were donated to the church in the 19th century by Pope Grego ...

, Dublin. The faith was beginning to be legalised in Ireland again but the relics of most of the old Irish saints had been destroyed, so Pope Gregory XVI gifted these to the Irish nation. In the aftermath of the Great Hunger, Cardinal Paul Cullen became the first Irish cardinal of the Catholic Church. He played a significant role in shaping 19th century Irish Catholicism and also played a leading role at the First Vatican Council

The First Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the First Vatican Council or Vatican I, was the 20th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church, held three centuries after the preceding Council of Trent which was adjourned in 156 ...

as an ultramontanist involved in crafting the formula for papal infallibility

Papal infallibility is a Dogma in the Catholic Church, dogma of the Catholic Church which states that, in virtue of the promise of Jesus to Saint Peter, Peter, the Pope when he speaks is preserved from the possibility of error on doctrine "in ...

. Cullen called the Synod of Thurles in 1850, the first formal synod of the Irish Catholic episcopacy and clergy since 1642 and then the Synod of Maynooth.

In 1879, there was a significant

In 1879, there was a significant Marian apparition

A Marian apparition is a reported supernatural appearance of Mary, the mother of Jesus. While sometimes described as a type of vision, apparitions are generally regarded as external manifestations, whereas visions are more often understood as ...

in Ireland, that of Our Lady of Knock

Knock may refer to:

Places

Northern Ireland

* Knock, Belfast, County Down

* Knock, County Armagh, a townland in County Armagh

Republic of Ireland

* Knock, County Clare, village in County Clare

* Knock, County Mayo, village in County Mayo

...

in County Mayo

County Mayo (; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. In the West Region, Ireland, West of Ireland, in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht, it is named after the village of Mayo, County Mayo, Mayo, now ge ...

. Here the Blessed Virgin Mary

Mary was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Saint Joseph, Joseph and the mother of Jesus. She is an important figure of Christianity, venerated under titles of Mary, mother of Jesus, various titles such as Perpetual virginity ...

is said to have appeared, with St. Joseph

Joseph is a common male name, derived from the Hebrew (). "Joseph" is used, along with " Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the modern-day Nordic count ...

and St. John the Evangelist

John the Evangelist ( – ) is the name traditionally given to the author of the Gospel of John. Christians have traditionally identified him with John the Apostle, John of Patmos, and John the Presbyter, although there is no consensus on how ...

either side (along with the '' Agnus Dei'') and she remained silent throughout. Statements were taken from 15 lay people who claimed to have witnessed the apparition. The Knock Shrine became a major place of pilgrimage and Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI (; born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti, ; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939) was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 until his death in February 1939. He was also the first sovereign of the Vatican City State u ...

declared Our Lady of Knock to be "Queen of Heaven and of Ireland" at the closing of the 1932 Eucharistic Congress.

Following the partition of Ireland

From the time that Ireland achieved independence, the church came to play an increasingly significant social and political role in theIrish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

and following that, the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 Counties of Ireland, counties of the island of Ireland, with a population of about 5.4 million. ...

. For many decades, Catholic influence (coupled with the rural nature of Irish society) meant that Ireland was able to uphold family-orientated social policies for longer than most of the West, contrary to the ''laissez-faire