Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Canadian syllabic writing, or simply syllabics, is a family of writing systems used in a number of indigenous Canadian languages of the Algonquian,

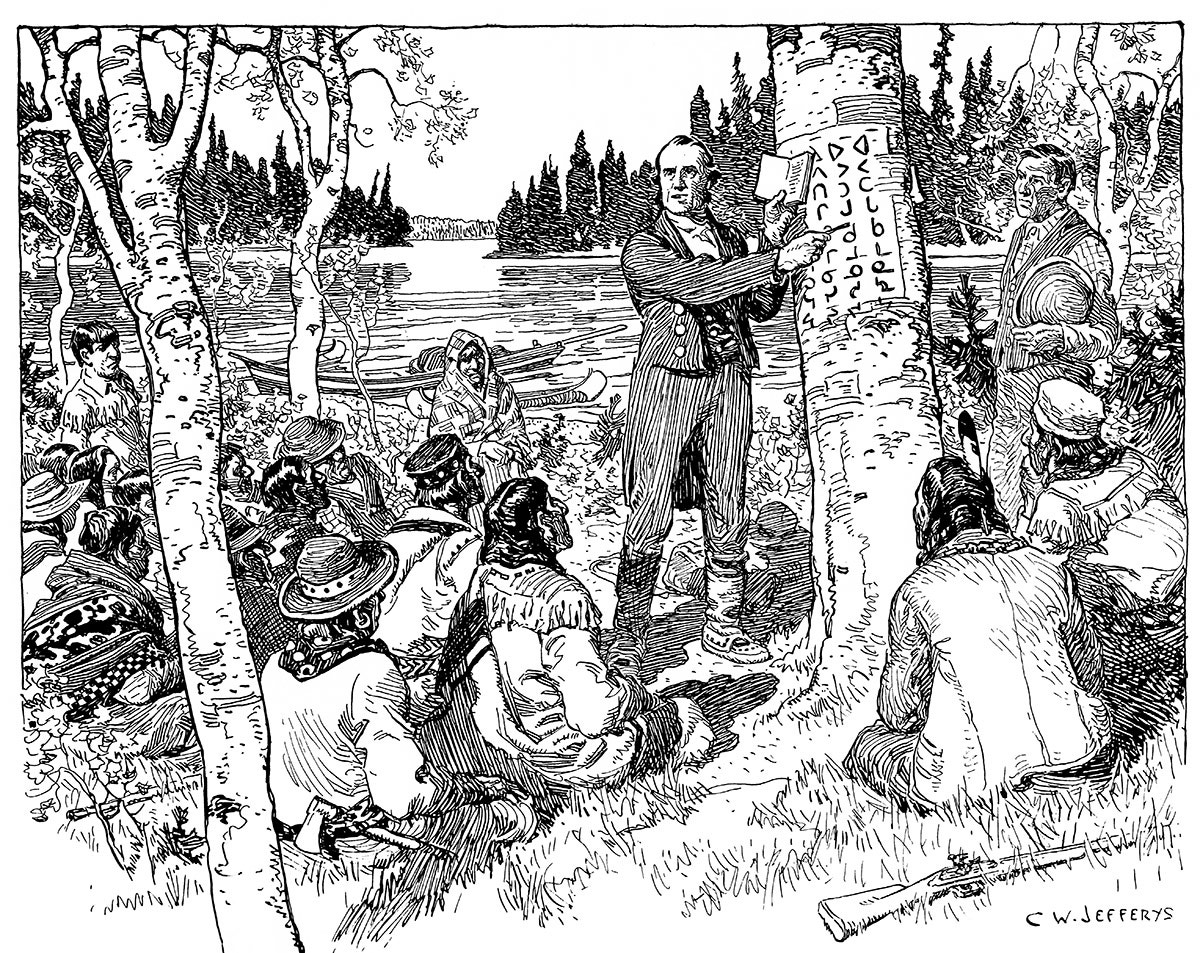

Cree syllabics were created in a process that culminated in 1840 by James Evans, a missionary, probably in collaboration with Indigenous language experts. Evans formalized them for

Cree syllabics were created in a process that culminated in 1840 by James Evans, a missionary, probably in collaboration with Indigenous language experts. Evans formalized them for

In 1828, Evans, a missionary from Kingston upon Hull, England, was placed in charge of the Wesleyan mission at Rice Lake, Ontario. Here, he learned the eastern

In 1828, Evans, a missionary from Kingston upon Hull, England, was placed in charge of the Wesleyan mission at Rice Lake, Ontario. Here, he learned the eastern

The local Cree community quickly took to this new writing system. Cree people began to use it to write messages on tree bark using burnt sticks, leaving messages out on hunting trails far from the mission. Evans believed that it was well adapted to Native Canadian languages, particularly the

The local Cree community quickly took to this new writing system. Cree people began to use it to write messages on tree bark using burnt sticks, leaving messages out on hunting trails far from the mission. Evans believed that it was well adapted to Native Canadian languages, particularly the  Evans left Canada in 1846 and died shortly thereafter. However, the ease and utility of syllabic writing ensured its continued survival, despite European resistance to supporting it. In 1849, David Anderson, the

Evans left Canada in 1846 and died shortly thereafter. However, the ease and utility of syllabic writing ensured its continued survival, despite European resistance to supporting it. In 1849, David Anderson, the

:

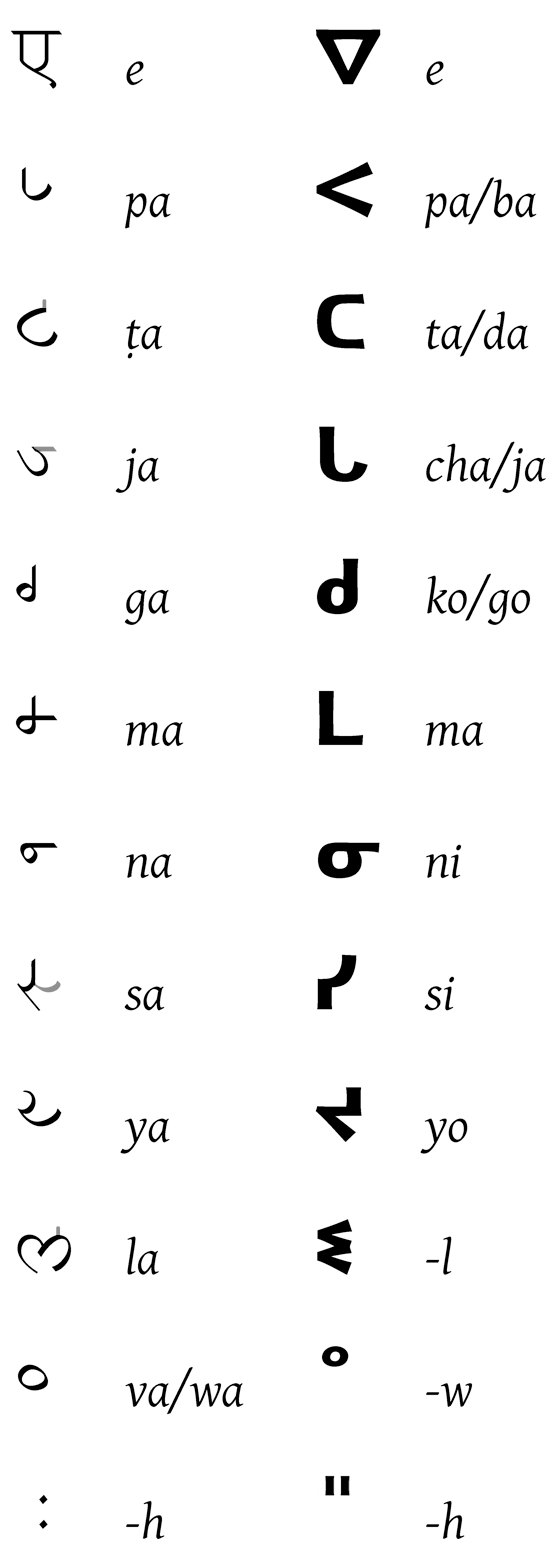

Because the script is presented in syllabic charts and learned as a syllabary, it is often considered to be such. Indeed, computer fonts have separate coding points for each syllable (each orientation of each consonant), and the

:

Because the script is presented in syllabic charts and learned as a syllabary, it is often considered to be such. Indeed, computer fonts have separate coding points for each syllable (each orientation of each consonant), and the

The vowels fall into two sets, the

The vowels fall into two sets, the

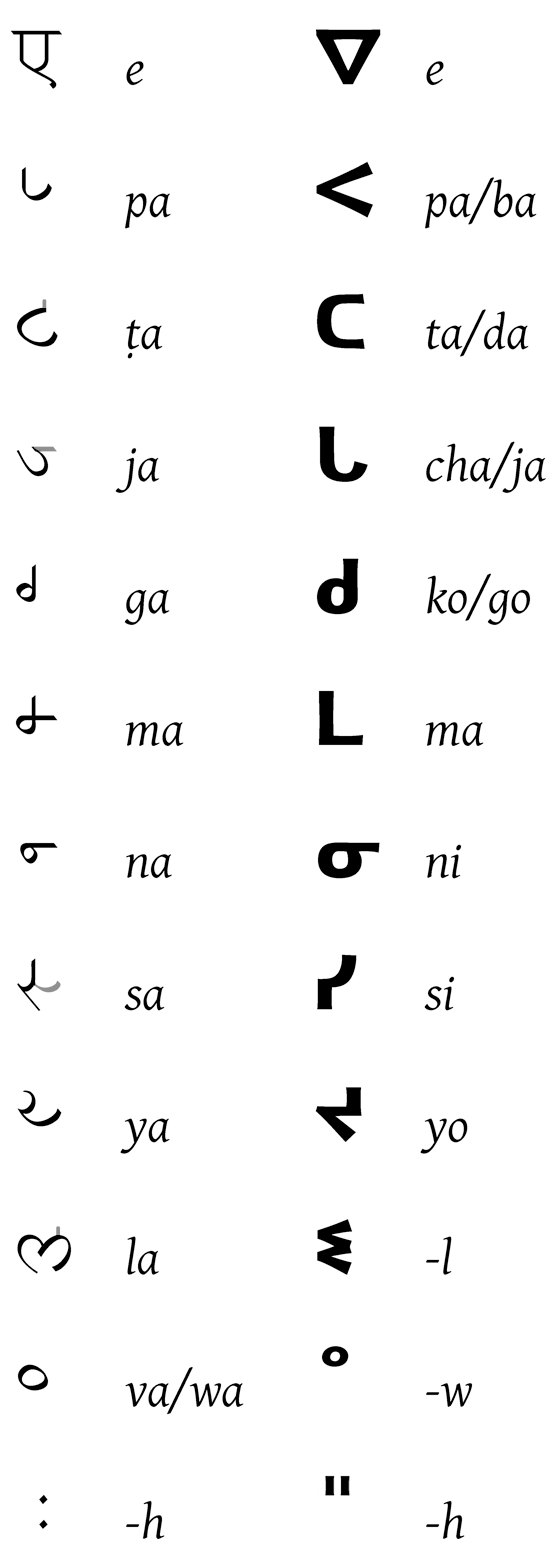

Blackfoot, another Algonquian language, uses a syllabary developed in the 1880s that is quite different from the Cree and Inuktitut versions. Although borrowing from Cree the ideas of rotated and mirrored glyphs with final variants, most of the letter forms derive from the Latin script, with only some resembling Cree letters. Blackfoot has eight initial consonants, only two of which are identical in form to their Cree equivalents, ''se'' and ''ye'' (here only the vowels have changed). The other consonants were created by modifying letters of the Latin script to make the ''e'' series, or in three cases by taking Cree letters but reassigning them with new sound values according to which Latin letters they resembled. These are ''pe'' (from ), ''te'' (from ), ''ke'' (from ), ''me'' (from ), ''ne'' (from ), ''we'' (from ). There are also a number of distinct final forms. The four vowel positions are used for the three vowels and one of the diphthongs of Blackfoot. The script is largely obsolete.

Blackfoot, another Algonquian language, uses a syllabary developed in the 1880s that is quite different from the Cree and Inuktitut versions. Although borrowing from Cree the ideas of rotated and mirrored glyphs with final variants, most of the letter forms derive from the Latin script, with only some resembling Cree letters. Blackfoot has eight initial consonants, only two of which are identical in form to their Cree equivalents, ''se'' and ''ye'' (here only the vowels have changed). The other consonants were created by modifying letters of the Latin script to make the ''e'' series, or in three cases by taking Cree letters but reassigning them with new sound values according to which Latin letters they resembled. These are ''pe'' (from ), ''te'' (from ), ''ke'' (from ), ''me'' (from ), ''ne'' (from ), ''we'' (from ). There are also a number of distinct final forms. The four vowel positions are used for the three vowels and one of the diphthongs of Blackfoot. The script is largely obsolete.

Athabaskan syllabic scripts were developed in the late 19th century by French Roman Catholic missionaries, who adapted this originally Protestant writing system to languages radically different from the Algonquian languages. Most

Athabaskan syllabic scripts were developed in the late 19th century by French Roman Catholic missionaries, who adapted this originally Protestant writing system to languages radically different from the Algonquian languages. Most

At present, Canadian syllabics seems reasonably secure within the Cree, Oji-Cree, and Inuit communities. They appear somewhat more at risk among the Ojibwe, and seriously endangered for Athabaskan languages and Blackfoot.

In

At present, Canadian syllabics seems reasonably secure within the Cree, Oji-Cree, and Inuit communities. They appear somewhat more at risk among the Ojibwe, and seriously endangered for Athabaskan languages and Blackfoot.

In

''Syllabics: A successful educational innovation.''

MEd thesis, University of Manitoba *Nichols, John. 1996. "The Cree syllabary." Peter Daniels and William Bright, eds. ''The world's writing systems,'' 599–611. New York: Oxford University Press.

*

Paper on Carrier Syllabics

Inuktitut syllabary Braille code

* ttp://www.albertasource.ca/methodist/Pictures/Cree_Bible1.htm Methodist Bible in Cree syllabics

Dene syllabic prayer book

Cree Origin of Syllabics

Cree Standard Roman Orthography to syllabics converter

ScriptSource entry for Cans script

Lists a few fonts.

GNU FreeFont

UCAS + UCASE range in sans-serif face. {{DEFAULTSORT:Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics

Inuit

Inuit (singular: Inuk) are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America and Russia, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwe ...

, and (formerly) Athabaskan language families. These languages had no formal writing system previously. They are valued for their distinctiveness from the Latin script

The Latin script, also known as the Roman script, is a writing system based on the letters of the classical Latin alphabet, derived from a form of the Greek alphabet which was in use in the ancient Greek city of Cumae in Magna Graecia. The Gree ...

and for the ease with which literacy can be achieved. For instance, by the late 19th century the Cree

The Cree, or nehinaw (, ), are a Indigenous peoples of the Americas, North American Indigenous people, numbering more than 350,000 in Canada, where they form one of the country's largest First Nations in Canada, First Nations. They live prim ...

had achieved what may have been one of the highest rates of literacy in the world. Syllabics are an abugida

An abugida (; from Geʽez: , )sometimes also called alphasyllabary, neosyllabary, or pseudo-alphabetis a segmental Writing systems#Segmental writing system, writing system in which consonant–vowel sequences are written as units; each unit ...

, where glyphs

A glyph ( ) is any kind of purposeful mark. In typography, a glyph is "the specific shape, design, or representation of a character". It is a particular graphical representation, in a particular typeface, of an element of written language. A ...

represent consonant–vowel pairs, determined by the rotation of the glyphs. They were created by linguist and missionary James Evans working with the Cree and Ojibwe.

Canadian syllabics are currently used to write all of the Cree language

Cree ( ; also known as Cree–Montagnais language, Montagnais–Naskapi language, Naskapi) is a dialect continuum of Algonquian languages spoken by approximately 86,475 people across Canada in 2021, from the Northwest Territories to Alberta to ...

s from including Eastern Cree, Plains Cree, Swampy Cree

The Swampy Cree people, also known by their Exonym and endonym, autonyms ''Néhinaw'', ''Maskiki Wi Iniwak'', ''Mushkekowuk,'' ''Maškékowak, Maskegon'' or ''Maskekon'' (and therefore also ''Muskegon'' and ''Muskegoes'') or by exonyms includin ...

, Woods Cree, and Naskapi

The Naskapi (Nascapi, Naskapee, Nascapee) are an Indigenous people of the Subarctic native to the historical region St'aschinuw (ᒋᑦ ᐊᔅᒋᓄᐤ, meaning 'our Clusivity, nclusiveland'), which was located in present day northern Qu ...

. They are also used to write Inuktitut

Inuktitut ( ; , Inuktitut syllabics, syllabics ), also known as Eastern Canadian Inuktitut, is one of the principal Inuit languages of Canada. It is spoken in all areas north of the North American tree line, including parts of the provinces of ...

in the Canadian Arctic; there they are co-official with the Latin script

The Latin script, also known as the Roman script, is a writing system based on the letters of the classical Latin alphabet, derived from a form of the Greek alphabet which was in use in the ancient Greek city of Cumae in Magna Graecia. The Gree ...

in the territory of Nunavut

Nunavut is the largest and northernmost Provinces and territories of Canada#Territories, territory of Canada. It was separated officially from the Northwest Territories on April 1, 1999, via the ''Nunavut Act'' and the Nunavut Land Claims Agr ...

. They are used regionally for the other large Canadian Algonquian language, Ojibwe

The Ojibwe (; Ojibwe writing systems#Ojibwe syllabics, syll.: ᐅᒋᐺ; plural: ''Ojibweg'' ᐅᒋᐺᒃ) are an Anishinaabe people whose homeland (''Ojibwewaki'' ᐅᒋᐺᐘᑭ) covers much of the Great Lakes region and the Great Plains, n ...

, as well as for Blackfoot. Among the Athabaskan languages

Athabaskan ( ; also spelled ''Athabascan'', ''Athapaskan'' or ''Athapascan'', and also known as Dene) is a large branch of the Na-Dene languages, Na-Dene language family of North America, located in western North America in three areal language ...

further to the west, syllabics have been used at one point or another to write Dakelh

The Dakelh (pronounced ) or Carrier are a First Nations in Canada, First Nations Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous people living a large portion of the British Columbia Interior, Central Interior of British Columbia, Canada. The Dakel ...

(Carrier), Chipewyan

The Chipewyan ( , also called ''Denésoliné'' or ''Dënesųłı̨né'' or ''Dënë Sųłınë́'', meaning "the original/real people") are a Dene group of Indigenous Canadian people belonging to the Athabaskan language family, whose ancest ...

, Slavey, Tłı̨chǫ

The Tłı̨chǫ (, ) people, sometimes spelled Tlicho and also known as the Dogrib, are a Dene First Nations people of the Athabaskan-speaking ethnolinguistic group living in the Northwest Territories of Canada.

Name

The name ''Dogrib' ...

(Dogrib), and Dane-zaa (Beaver). Syllabics have occasionally been used in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

by communities that straddle the border.

History

Cree syllabics were created in a process that culminated in 1840 by James Evans, a missionary, probably in collaboration with Indigenous language experts. Evans formalized them for

Cree syllabics were created in a process that culminated in 1840 by James Evans, a missionary, probably in collaboration with Indigenous language experts. Evans formalized them for Swampy Cree

The Swampy Cree people, also known by their Exonym and endonym, autonyms ''Néhinaw'', ''Maskiki Wi Iniwak'', ''Mushkekowuk,'' ''Maškékowak, Maskegon'' or ''Maskekon'' (and therefore also ''Muskegon'' and ''Muskegoes'') or by exonyms includin ...

and Ojibwe

The Ojibwe (; Ojibwe writing systems#Ojibwe syllabics, syll.: ᐅᒋᐺ; plural: ''Ojibweg'' ᐅᒋᐺᒃ) are an Anishinaabe people whose homeland (''Ojibwewaki'' ᐅᒋᐺᐘᑭ) covers much of the Great Lakes region and the Great Plains, n ...

. Evans had been inspired by the success of Sequoyah's Cherokee syllabary after encountering problems with Latin-based alphabets, and drew on his knowledge of Devanagari

Devanagari ( ; in script: , , ) is an Indic script used in the Indian subcontinent. It is a left-to-right abugida (a type of segmental Writing systems#Segmental systems: alphabets, writing system), based on the ancient ''Brāhmī script, Brā ...

and Pitman shorthand. Canadian syllabics would in turn influence the Pollard script, which is used to write various Hmong-Mien and Lolo-Burmese languages. Other missionaries were reluctant to use it, but it was rapidly indigenized and spread to new communities before missionaries arrived.

A conflicting account is recorded in Cree oral traditions, asserting that the script originated from Cree culture before 1840. Per these traditions, syllabics were the invention of Calling Badger (, ), a Cree man. Legend states that Badger had died and returned from the spirit world to share the knowledge of writing with his people. Some scholars write that these legends were created after 1840.Verne Dusenberry, 1962. ''The Montana Cree: A Study in Religious Persistence'' (Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis 3). p 267–269 Cree scholar Winona Stevenson explores the possibility that the inspiration for Cree syllabics may have originated from a near-death experience of Calling Badger. Stevenson references Fine Day cited in David G. Mandelbaum's ''The Plains Cree'' who states that he learned the syllabary from Strikes-him-on-the-back who learned it directly from Calling Badger.

James Evans

In 1828, Evans, a missionary from Kingston upon Hull, England, was placed in charge of the Wesleyan mission at Rice Lake, Ontario. Here, he learned the eastern

In 1828, Evans, a missionary from Kingston upon Hull, England, was placed in charge of the Wesleyan mission at Rice Lake, Ontario. Here, he learned the eastern Ojibwe language

Ojibwe ( ), also known as Ojibwa ( ), Ojibway, Otchipwe,R. R. Bishop Baraga, 1878''A Theoretical and Practical Grammar of the Otchipwe Language''/ref> Ojibwemowin, or Anishinaabemowin, is an Indigenous languages of the Americas, indigenous la ...

spoken in the area. By 1833, he had gained further linguistic experience by teaching in various mission schools around the area, and was invited to join a church committee seeking to develop a writing system for Ojibwe, based on the Latin alphabet

The Latin alphabet, also known as the Roman alphabet, is the collection of letters originally used by the Ancient Rome, ancient Romans to write the Latin language. Largely unaltered except several letters splitting—i.e. from , and from � ...

. By 1837, he had prepared the ''Speller and Interpreter in English and Indian,'' but was unable to get its printing sanctioned by the British and Foreign Bible Society. At the time, many missionary societies were opposed to the development of native literacy in their own languages, believing that their situation would be bettered by linguistic assimilation into colonial society.

Evans continued to use his alphabetic Ojibwe orthography despite the rejection, and even travelled to New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

to publish Ojibwe hymnals. As was common at the time, the orthography

An orthography is a set of convention (norm), conventions for writing a language, including norms of spelling, punctuation, Word#Word boundaries, word boundaries, capitalization, hyphenation, and Emphasis (typography), emphasis.

Most national ...

called for hyphens between the syllables of words, giving written Ojibwe a partially syllabic structure. However, his students appear to have had conceptual difficulties using the same alphabet for two different languages with very different sounds, and Evans himself found this approach awkward. Furthermore, the Ojibwe language was polysynthetic

In linguistic typology, polysynthetic languages, formerly holophrastic languages, are highly synthetic languages, i.e., languages in which words are composed of many morphemes (word parts that have independent meaning but may or may not be able t ...

but had few distinct syllables, meaning that most words had a large number of syllables; this made them quite long when written with the Latin script. He began to experiment with creating a more syllabic script that he thought might be less awkward for his students to use.

In 1840, Evans was relocated to Norway House in northern Manitoba

Manitoba is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada at the Centre of Canada, longitudinal centre of the country. It is Canada's Population of Canada by province and territory, fifth-most populous province, with a population ...

. Here he began learning the local Swampy Cree

The Swampy Cree people, also known by their Exonym and endonym, autonyms ''Néhinaw'', ''Maskiki Wi Iniwak'', ''Mushkekowuk,'' ''Maškékowak, Maskegon'' or ''Maskekon'' (and therefore also ''Muskegon'' and ''Muskegoes'') or by exonyms includin ...

dialect. Like the closely related Ojibwe

The Ojibwe (; Ojibwe writing systems#Ojibwe syllabics, syll.: ᐅᒋᐺ; plural: ''Ojibweg'' ᐅᒋᐺᒃ) are an Anishinaabe people whose homeland (''Ojibwewaki'' ᐅᒋᐺᐘᑭ) covers much of the Great Lakes region and the Great Plains, n ...

, it was full of long polysyllabic words.

As an amateur linguist, Evans was acquainted with the Devanagari

Devanagari ( ; in script: , , ) is an Indic script used in the Indian subcontinent. It is a left-to-right abugida (a type of segmental Writing systems#Segmental systems: alphabets, writing system), based on the ancient ''Brāhmī script, Brā ...

script used in British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance in South Asia. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another ...

; in Devanagari, each letter stands for a syllable, and is modified to represent the vowel of that syllable. Such a system, now called an abugida

An abugida (; from Geʽez: , )sometimes also called alphasyllabary, neosyllabary, or pseudo-alphabetis a segmental Writing systems#Segmental writing system, writing system in which consonant–vowel sequences are written as units; each unit ...

, would have readily lent itself to writing a language such as Swampy Cree, which had a simple syllable structure of only eight consonants and four long or short vowels. Evans was also familiar with British shorthand, presumably Samuel Taylor's '' Universal Stenography,'' from his days as a merchant in England; and now he acquired familiarity with the newly published Pitman shorthand of 1837.

Adoption and use

The local Cree community quickly took to this new writing system. Cree people began to use it to write messages on tree bark using burnt sticks, leaving messages out on hunting trails far from the mission. Evans believed that it was well adapted to Native Canadian languages, particularly the

The local Cree community quickly took to this new writing system. Cree people began to use it to write messages on tree bark using burnt sticks, leaving messages out on hunting trails far from the mission. Evans believed that it was well adapted to Native Canadian languages, particularly the Algonquian languages

The Algonquian languages ( ; also Algonkian) are a family of Indigenous languages of the Americas and most of the languages in the Algic language family are included in the group. The name of the Algonquian language family is distinguished from ...

with which he was familiar. He claimed that "with some slight alterations" it could be used to write "every language from the Atlantic to the Rocky Mountains."

Evans attempted to secure a printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a printing, print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in whi ...

and new type

Type may refer to:

Science and technology Computing

* Typing, producing text via a keyboard, typewriter, etc.

* Data type, collection of values used for computations.

* File type

* TYPE (DOS command), a command to display contents of a file.

* ...

to publish materials in this writing system. Here, he began to face resistance from colonial and European authorities. The Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), originally the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading Into Hudson’s Bay, is a Canadian holding company of department stores, and the oldest corporation in North America. It was the owner of the ...

, which had a monopoly on foreign commerce in western Canada, refused to import a press for him, believing that native literacy was something to be discouraged. Evans, with immense difficulty, constructed his own press and type and began publishing in syllabics.

Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

bishop of Rupert's Land

Rupert's Land (), or Prince Rupert's Land (), was a territory in British North America which comprised the Hudson Bay drainage basin. The right to "sole trade and commerce" over Rupert's Land was granted to Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), based a ...

, reported that "a few of the Indians can read by means of these syllabic characters; but if they had only been taught to read their own language in our letters, it would have been one step towards the acquisition of the English tongue." But syllabics had taken root among the Cree (indeed, their rate of literacy was greater than that of English and French Canadians), and in 1861, fifteen years after Evans had died, the British and Foreign Bible Society published a Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

in Cree syllabics

Cree syllabics are the versions of Canadian Aboriginal syllabics used to write Cree language, Cree dialects, including the original syllabics system created for Cree and Ojibwe language, Ojibwe. There are two main varieties of syllabics for Cre ...

. By then, both Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

and Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

missionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group who is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Miss ...

were using and actively propagating syllabic writing.

Missionary work in the 1850s and 1860s spread syllabics to western Canadian Ojibwe

The Ojibwe (; Ojibwe writing systems#Ojibwe syllabics, syll.: ᐅᒋᐺ; plural: ''Ojibweg'' ᐅᒋᐺᒃ) are an Anishinaabe people whose homeland (''Ojibwewaki'' ᐅᒋᐺᐘᑭ) covers much of the Great Lakes region and the Great Plains, n ...

dialects ( Plains Ojibwe and Saulteaux

The Saulteaux (pronounced , or in imitation of the French pronunciation , also written Salteaux, Saulteau and Ojibwa ethnonyms, other variants), otherwise known as the Plains Ojibwe, are a First Nations in Canada, First Nations band governm ...

), but it was not often used over the border by Ojibwe in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

. Missionaries who had learned Evans' system spread it east across Ontario

Ontario is the southernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Located in Central Canada, Ontario is the Population of Canada by province and territory, country's most populous province. As of the 2021 Canadian census, it ...

and into Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

, reaching all Cree language

Cree ( ; also known as Cree–Montagnais language, Montagnais–Naskapi language, Naskapi) is a dialect continuum of Algonquian languages spoken by approximately 86,475 people across Canada in 2021, from the Northwest Territories to Alberta to ...

areas as far east as the Naskapi

The Naskapi (Nascapi, Naskapee, Nascapee) are an Indigenous people of the Subarctic native to the historical region St'aschinuw (ᒋᑦ ᐊᔅᒋᓄᐤ, meaning 'our Clusivity, nclusiveland'), which was located in present day northern Qu ...

. Attikamekw, Montagnais and Innu

The Innu/Ilnu ('man, person'), formerly called Montagnais (French for ' mountain people'; ), are the Indigenous Canadians who inhabit northeastern Labrador in present-day Newfoundland and Labrador and some portions of Quebec. They refer to ...

people in eastern Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

and Labrador

Labrador () is a geographic and cultural region within the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. It is the primarily continental portion of the province and constitutes 71% of the province's area but is home to only 6% of its populatio ...

use Latin alphabets

The lists and tables below summarize and compare the letter inventories of some of the Latin-script alphabets. In this article, the scope of the word "alphabet" is broadened to include letters with tone marks, and other diacritics used to represe ...

.

In 1856, John Horden, an Anglican missionary at Moose Factory, Ontario, who adapted syllabics to the local James Bay Cree dialect, met a group of Inuit

Inuit (singular: Inuk) are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America and Russia, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwe ...

from the region of Grande Rivière de la Baleine in northern Quebec. They were very interested in adapting Cree syllabics

Cree syllabics are the versions of Canadian Aboriginal syllabics used to write Cree language, Cree dialects, including the original syllabics system created for Cree and Ojibwe language, Ojibwe. There are two main varieties of syllabics for Cre ...

to their language. He prepared a few based on their pronunciation of Inuktitut

Inuktitut ( ; , Inuktitut syllabics, syllabics ), also known as Eastern Canadian Inuktitut, is one of the principal Inuit languages of Canada. It is spoken in all areas north of the North American tree line, including parts of the provinces of ...

, but it quickly became obvious that the number of basic sounds and the simple model of the syllable in the Evans system was inadequate to the language. With the assistance of Edwin Arthur Watkins, he dramatically modified syllabics to reflect these needs.

In 1876, the Anglican church

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

hired Edmund Peck to work full-time in their mission at Great Whale River, teaching syllabics to the Inuit

Inuit (singular: Inuk) are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America and Russia, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwe ...

and translating materials into syllabics. His work across the Arctic

The Arctic (; . ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the North Pole, lying within the Arctic Circle. The Arctic region, from the IERS Reference Meridian travelling east, consists of parts of northern Norway ( ...

is usually credited with the establishment of syllabics among the Inuit. With the support of both Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

and Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

missionary societies, by the beginning of the 20th century the Inuit were propagating syllabics themselves.

In the 1880s, John William Tims, an Anglican missionary from Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

, invented a number of new forms to write the Blackfoot language

The Blackfoot language, also called Niitsi'powahsin () or Siksiká ( ; , ), is an Algonquian languages, Algonquian language spoken by the Blackfoot Confederacy, Blackfoot or people, who currently live in the northwestern plains of North Americ ...

.

French Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

missionaries were the primary force for expanding syllabics to Athabaskan languages

Athabaskan ( ; also spelled ''Athabascan'', ''Athapaskan'' or ''Athapascan'', and also known as Dene) is a large branch of the Na-Dene languages, Na-Dene language family of North America, located in western North America in three areal language ...

in the late 19th century. The Oblate missionary order was particularly active in using syllabics in missionary work. Oblate father Adrien-Gabriel Morice adapted syllabics to Dakelh

The Dakelh (pronounced ) or Carrier are a First Nations in Canada, First Nations Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous people living a large portion of the British Columbia Interior, Central Interior of British Columbia, Canada. The Dakel ...

, inventing a large number of new basic characters to support the radically more complicated phonetics of Athabaskan languages. Father Émile Petitot developed syllabic scripts for many of the Athabaskan languages of the Northwest Territories

The Northwest Territories is a federal Provinces and territories of Canada, territory of Canada. At a land area of approximately and a 2021 census population of 41,070, it is the second-largest and the most populous of Provinces and territorie ...

, including Slavey and Chipewyan

The Chipewyan ( , also called ''Denésoliné'' or ''Dënesųłı̨né'' or ''Dënë Sųłınë́'', meaning "the original/real people") are a Dene group of Indigenous Canadian people belonging to the Athabaskan language family, whose ancest ...

.

Cree influenced the design of the Pollard script in China.

Cree oral traditions

Cree oral traditions state that the script was gifted to the Cree through the spirit world, rather than being invented by a missionary. In the 1930s, Chief Fine Day of the Sweetgrass First Nation told Mandelbaum the following account:A Wood Cree named Badger-call died and then became alive again. While he was dead he was given the characters of the syllabary and told that with them he could write Cree. Strike-him-on-the-back learned this writing from Badger-call. He made a feast and announced that he would teach it to anyone who wanted to learn. That is how I learned it. Badger-call also taught the writing to the missionaries. When the writing was given to Badger-call he was told 'They he missionarieswill change the script and will say that the writing belongs to them. But only those who know Cree will be able to read it.' That is how we know that the writing does not belong to the whites, for it can be read only by those who know the Cree language.Fine Day's grandson Wes Fineday gave the following account on CBC radio Morningside in two interviews in 1994 and 1998:

Fineday the younger explained that Calling Badger came from the Stanley Mission area and lived ten to fifteen years before his grandfather's birth in 1846. On his way to a sacred society meeting one evening Calling Badger and two singers came upon a bright light and all three fell to the ground. Out of the light came a voice speaking Calling Badger's name. Soon after, Calling Badger fell ill and the people heard he had passed away. During his wake three days later, while preparing to roll him in buffalo robes for the funeral, the people discovered that his body was not stiff like a dead person's body should be. Against all customs and tradition the people agreed to the widow's request to let the body sit one more night. The next day Calling Badger's body was still not stiff so the old people began rubbing his back and chest. Soon his eyes opened and he told the people he had gone to the Fourth World, the spirit world, and there the spirits taught him many things. Calling Badger told the people of the things he was shown that prophesized events in the future, then he pulled out some pieces of birch bark with symbols on them. These symbols, he told the people, were to be used to write down the spirit languages, and for the Cree people to communicate among themselves. (Stevenson 20)When asked whether the story was meant to be understood literally, Wes Fineday commented: "The sacred stories ... are not designed necessarily to provide answers but merely to begin to point out directions that can be taken. ... Understand that it is not the work of storytellers to bring answers to you. ... What we can do is we can tell you stories and if you listen to those stories in the sacred manner with an open heart, an open mind, open eyes and open ears, those stories will speak to you." In December 1959, anthropologist Verne Dusenberry, while among the Plains Cree on the Rocky Boy reservation in

Montana

Montana ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota to the east, South Dakota to the southeast, Wyoming to the south, an ...

, was told a similar narrative by Raining Bird:

According to Raining Bird "the spirits came to one good man and gave him some songs. When he mastered them, they taught him how to make a type of ink and then showed him how to write on white birch bark." He also received many teachings about the spirits which he recorded in a birch bark book. When the one good man returned to his people he taught them how to read and write. "The Cree were very pleased with their new accomplishment, for by now the white men were in this country. The Cree knew that the white traders could read and write, so now they felt that they too were able to communicate among themselves just as well as did their white neighbors." (Stevenson 21)Stevenson (aka Wheeler) comments that the legend is commonly known among the Cree. However, there is no known surviving physical evidence of Canadian Aboriginal syllabics before Norway House. Linguist Chris Harvey believes that the syllabics were a collaboration between English missionaries, Indigenous Cree and Ojibwe-language experts, such as the Ojibwe Henry Bird Steinhauer (Sowengisik) and Cree translator Sophie Mason, who worked alongside Evans at his time in Norway House.

Basic principles

Canadian "syllabic" scripts are notsyllabaries

In the linguistic study of written languages, a syllabary is a set of written symbols that represent the syllables or (more frequently) morae which make up words.

A symbol in a syllabary, called a syllabogram, typically represents an (option ...

, in which every consonant–vowel sequence has a separate glyph, but abugida

An abugida (; from Geʽez: , )sometimes also called alphasyllabary, neosyllabary, or pseudo-alphabetis a segmental Writing systems#Segmental writing system, writing system in which consonant–vowel sequences are written as units; each unit ...

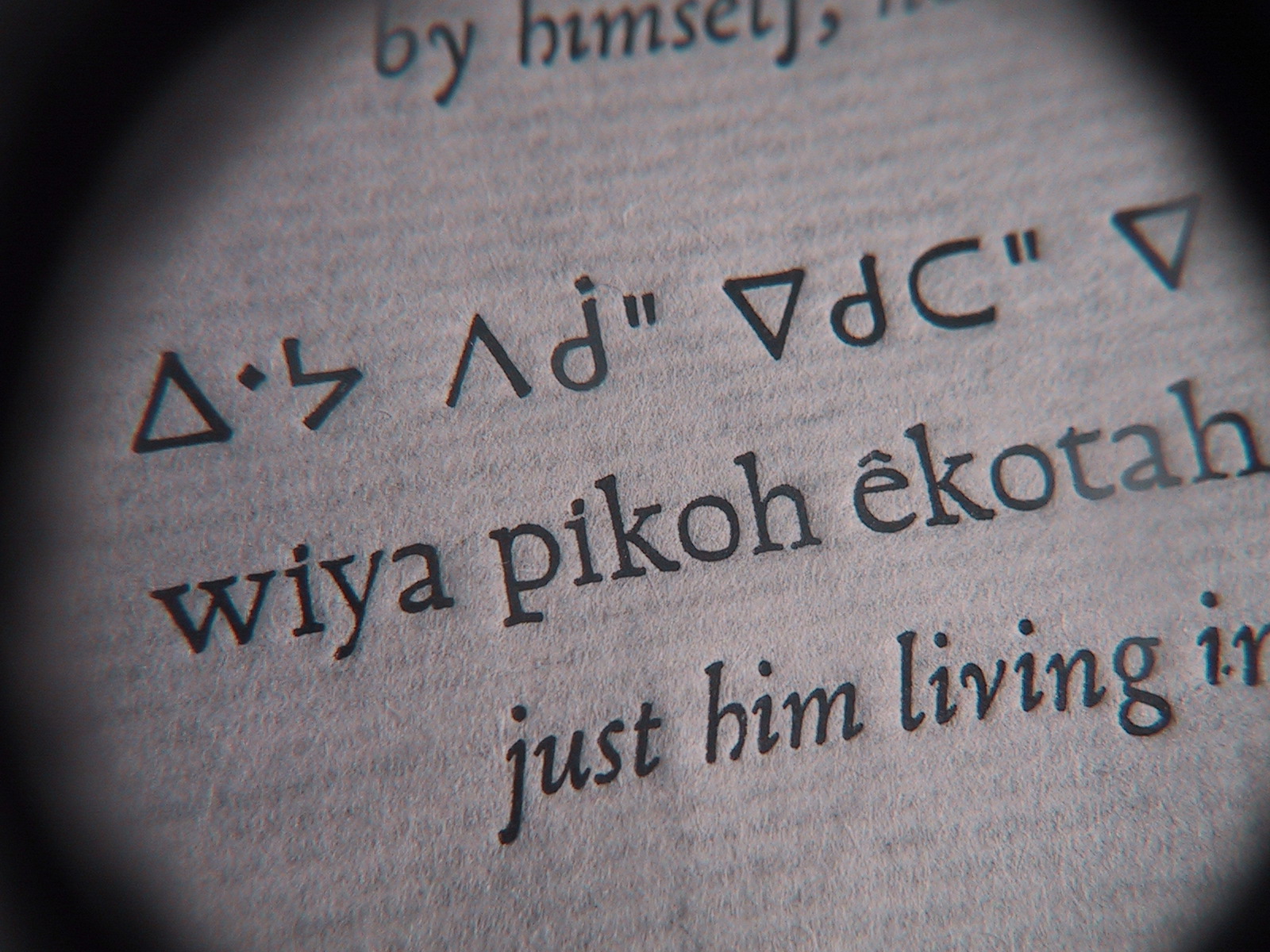

s, in which consonants are modified in order to indicate an associated vowel—in this case through a change in orientation (which is unique to Canadian syllabics). In Cree, for example, the consonant ''p'' has the shape of a chevron; in an upward orientation, ᐱ, it transcribes the syllable ''pi''; inverted, so that it points downwards, ᐯ, it transcribes ''pe''; pointing to the left, ᐸ, it is ''pa,'' and to the right, ᐳ, ''po''. The consonant forms and the vowels so represented vary from language to language, but generally approximate their Cree origins.

:

Because the script is presented in syllabic charts and learned as a syllabary, it is often considered to be such. Indeed, computer fonts have separate coding points for each syllable (each orientation of each consonant), and the

:

Because the script is presented in syllabic charts and learned as a syllabary, it is often considered to be such. Indeed, computer fonts have separate coding points for each syllable (each orientation of each consonant), and the Unicode Consortium

The Unicode Consortium (legally Unicode, Inc.) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization incorporated and based in Mountain View, California, U.S. Its primary purpose is to maintain and publish the Unicode Standard which was developed with the in ...

considers syllabics to be a "featural syllabary" along with such scripts as hangul

The Korean alphabet is the modern writing system for the Korean language. In North Korea, the alphabet is known as (), and in South Korea, it is known as (). The letters for the five basic consonants reflect the shape of the speech organs ...

, where each block represents a syllable, but consonants and vowels are indicated independently (in Cree syllabics, the consonant by the shape of a glyph, and the vowel by its orientation). This is unlike a true syllabary, where each combination of consonant and vowel has an independent form that is unrelated to other syllables with the same consonant or vowel.

Syllabic and final consonant forms

The original script, which was designed for Western Swampy Cree, had ten such letterforms: eight for syllables based on the consonants ''p-'', ''t-'', ''c-'', ''k-'', ''m-'', ''n-'', ''s-'', ''y-'' (pronounced /p, t, ts, k, m, n, s, j/), another for vowel-initial syllables, and finally a blended form, now obsolete, for the consonant cluster ''sp-''. In the 1840 version, all were written with a light line to show the vowel was short and a heavier line to show the vowel was long: ᑲ ''ka'', ᑲ ''kâ''; however, in the 1841 version, a light line indicated minuscules ("lowercase") and a heavier line indicated majuscules ("uppercase"): ᑲ ''ka'', ᑲ ''KA'' or ''Ka''; additionally in the 1841 version, an unbroken letterform indicated a short vowel, but for a long vowel, Evans notched the face of the type sorts, such that in print the letterform was broken. A handwritten variant using anoverdot

When used as a diacritic mark, the term dot refers to the glyphs "combining dot above" (, and "combining dot below" (

which may be combined with some letters of the extended Latin alphabets in use in

a variety of languages. Similar marks are ...

to indicate a long vowel is now used in printing as well: ᑕ ''ta'', ᑖ ''tâ''. One consonant, ''w'', had no letterform of its own but was indicated by a diacritic on another syllable; this is because it could combine with any of the consonants, as in ᑿ ''kwa'', as well as existing on its own, as in ᐘ ''wa''.

There were distinct letters for the nine consonants ''-p'', ''-t'', ''-c'', ''-k'', ''-m'', ''-n'', ''-s'', ''-y'', and ''w'' when they occurred at the end of a syllable. In addition, four "final" consonants had no syllabic forms: ''-h'', ''-l'', ''-r'', and the sequence ''-hk''. These were originally written midline, but are now superscripted. (The glyph for ''-hk'' represents the most common final sequence of the language, being a common grammatical ending in Cree, and was used for common ''-nk'' in Ojibwe.) The consonants ''-l'' and ''-r'' were marginal, only found in borrowings, baby talk, and the like. These, and ''-h'', could occur before vowels, but were written with the final shape regardless. (''-l'' and ''-r'' are now written the size of full letters when they occur before vowels, as the finals were originally, or in some syllabics scripts have been replaced with full rotating syllabic forms; ''-h'' only occurs before a vowel in joined morphemes, in couple grammatical words, or in pedagogical materials to indicate the consonant value following it is fortis

Fortis may refer to:

Business

* Fortis (Swiss watchmaker), a Swiss watch company

* Fortis Films, an American film and television production company founded by actress and producer Sandra Bullock

* Fortis Healthcare, a chain of hospitals in ...

.)

Vowel transformations

back vowel

A back vowel is any in a class of vowel sound used in spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a back vowel is that the highest point of the tongue is positioned relatively back in the mouth without creating a constriction that would be c ...

s ''-a'' and ''-u,'' and the front vowel

A front vowel is a class of vowel sounds used in some spoken languages, its defining characteristic being that the highest point of the tongue is positioned approximately as far forward as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction th ...

s ''-e'' and ''-i.'' Each set consists of a lower vowel, ''-a'' or ''-e,'' and a higher vowel, ''-u'' or ''-i.'' In all cases, back-vowel syllables are related through left-right reflection: that is, they are mirror images of each other. How they relate to front-vowel syllables depends on the graphic form of the consonants. These follow two patterns. Symmetrical, ''vowel, p-, t-, sp-,'' are rotated 90 degrees (a quarter turn) counter-clockwise, while those that are asymmetrical top-to-bottom, ''c-, k-, m-, n-, s-, y-,'' are rotated 180 degrees (a half turn). The lower front-vowel (''-e'') syllables are derived this way from the low back-vowel (''a'') syllables, and the high front-vowel (''-i'') syllables are derived this way from the higher back-vowel (''-u'') syllables.

The symmetrical letter forms can be illustrated by arranging them into a diamond:

::

And the asymmetrical letter forms can be illustrated by arranging them into a square:

::

These forms are present in most syllabics scripts with sounds values that approach their Swampy Cree origins. For example, all scripts except the one for Blackfoot use the triangle for vowel-initial syllables.

By 1841, when Evans cast the first movable type for syllabics, he found that he could not satisfactorily maintain the distinction between light and heavy typeface for short and long vowels. He instead filed across the raised lines of the type, leaving gaps in the printed letter for long vowels. This can be seen in early printings. Later still a dot diacritic, originally used for vowel length only in handwriting, was extended to print: Thus today ᐊ ''a'' contrasts with ᐋ ''â,'' and ᒥ ''mi'' contrasts with ᒦ ''mî''. Although Cree ''ê'' only occurs long, the script made length distinctions for all four vowels. Not all writers then or now indicate length, or do not do so consistently; since there is no contrast, no one today writes ''ê'' as a long vowel.

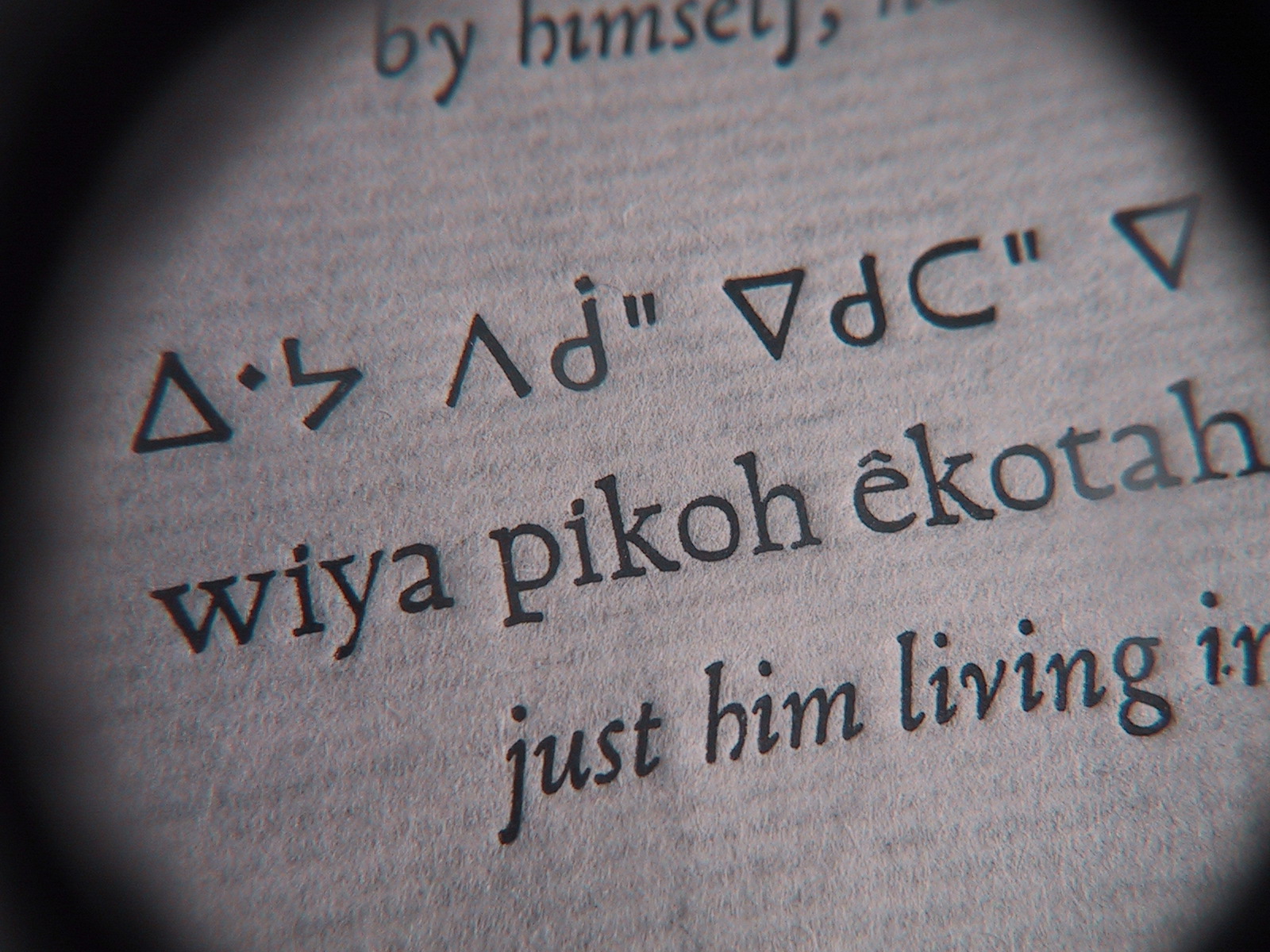

Pointing

Reflecting the shorthand principles on which it was based, syllabics may be written ''plain'', indicating only the basic consonant–vowel outline of speech, or ''pointed'', with diacritics for vowel length and the consonants and . Full phonemic pointing is rare. Syllabics may also be written without word division, as Devanagari once was, or with spaces or dots between words or prefixes.Punctuation

The only punctuation found in many texts is spacing between words and ᙮ for a full stop. Punctuation from the Latin script, including the period (.), may also be used. Due to the final ''c'' resembling a hyphen, a double hyphen is used as the Canadian Aboriginal syllabics hyphen.Glossary

Some common terms as used in the context of syllabics"Syllables", or full-size letters

The full-sized characters, whether standing for consonant-vowel combinations or vowels alone, are usually called "syllables". They may bephonemic

A phoneme () is any set of similar speech sounds that are perceptually regarded by the speakers of a language as a single basic sound—a smallest possible phonetic unit—that helps distinguish one word from another. All languages con ...

rather than morphophonemic syllables. That is, when one morpheme

A morpheme is any of the smallest meaningful constituents within a linguistic expression and particularly within a word. Many words are themselves standalone morphemes, while other words contain multiple morphemes; in linguistic terminology, this ...

(word element) ends in a consonant and the next begins with a vowel, the intermediate consonant is written as a syllable with the following vowel. For example, the Plains Cree word "indoors" has as its first morpheme, and ''āyi'' as its second, but is written ᐲᐦᒑᔨᕽ

In other cases, a "syllable" may in fact represent only a consonant, again due to the underlying structure of the language. In Plains Cree, ᑖᓂᓯ "hello" or "how are you?" is written as if it had three syllables. Because the first syllable has the stress and the syllable that follows has a short , the vowel is dropped. As a result, the word is pronounced "tānsi" with only two syllables.

Syllabication is important to determining stress in Algonquian languages, and vice versa, so this ambiguity in syllabics is relatively important in Algonquian languages.

Series

The word "series" is used for either a set of syllables with the same vowel, or a set with the same initial consonant. Thus the n-series is the set of syllables that begin with ''n,'' and the o-series is the set of syllables that have ''o'' as their vowel regardless of their initial consonant."Finals", or reduced letters

A series of small raised letters are called "finals". They are usually placed after a syllable to indicate a final consonant, as the ᕽ ''-hk'' in ᔨᕽ above. However, the Cree consonant ''h,'' which only has a final form, begins a small number of function words such as ᐦᐋᐤ ''hāw.'' In such cases the "final" ᐦ represents an ''initial'' consonant and therefore precedes the syllable. The use of diacritics to write consonants is unusual in abugidas. However, it also occurs (independently) in the Lepcha script. Finals are commonly employed in the extension of syllabics to languages it was not initially designed for. In some of the Athabaskan alphabets, finals have been extended to appear at mid height after a syllable, lowered after a syllable, and at mid height before a syllable. For example, Chipewyan and Slavey use the final ᐟ in the latter position to indicate the initial consonant ''dl'' (). In Naskapi, a small raised letter based on ''sa'' is used forconsonant cluster

In linguistics, a consonant cluster, consonant sequence or consonant compound is a group of consonants which have no intervening vowel. In English, for example, the groups and are consonant clusters in the word ''splits''. In the education fie ...

s that begin with /s/: ᔌ ᔍ ᔎ and ᔏ The Cree languages the script was initially designed for had no such clusters.

In Inuktitut, something similar is used not to indicate sequences, but to represent additional consonants, rather as the digraphs ''ch, sh, th'' were used to extend the Latin letters ''c, s, t'' to represent additional consonants in English. In Inuktitut, a raised ''na-ga'' is placed before the ''g-'' series, ᖏ ᖑ ᖓ, to form an ''ng-'' () series, and a raised ''ra'' (uvular ) is placed before syllables of the ''k-'' series, ᕿ ᖁ ᖃ, to form a uvular ''q-'' series.

Although the forms of these series have two parts, each is encoded into the Unicode standard as a single character.

Diacritics

Other marks placed above or beside the syllable are called "diacritic

A diacritic (also diacritical mark, diacritical point, diacritical sign, or accent) is a glyph added to a letter or to a basic glyph. The term derives from the Ancient Greek (, "distinguishing"), from (, "to distinguish"). The word ''diacrit ...

s". These include the dot placed above a syllable to mark a long vowel, as in ᒦ ''mî,'' and the dot placed at mid height after the syllable (in western Cree dialects) or before the syllable (in eastern Cree dialects) to indicate a medial ''w,'' as in ᑿ ''kwa.'' These are all encoded as single characters in Unicode.

Diacritics used by other languages include a ring above on Moose Cree ᑬ ''kay'' (encoded as "kaai"), head ring on Ojibwe ᕓ ''fe'', head barb on Inuktitut ᖤ ''lha'', tail barb on West Cree ᖌ ''ro'', centred stroke (a small vertical bar) in Carrier ᗇ ''ghee'', centred dot in Carrier ᗈ ''ghi'', centred bar (a bar perpendicular to the body) in Cree ᖨ ''thi'', and a variety of other marks. Such diacritics may or may not be separately encoded into Unicode. There is no systematic way to distinguish elements that are parts of syllables from diacritics, or diacritics from finals, and academic discussions of syllabics are often inconsistent in their terminology.

Points and pointing

The diacritic mark used to indicate vowel length is often referred to as a "point". Syllabics users do not always consistently mark vowel length, ''w,'' or ''h.'' A text with these marked is called a "pointed" text; one without such marks is said to be "unpointed".Syllabaries and syllabics

The word ''syllabary'' has two meanings: a writing system with a separate character for each syllable, but also a table of syllables, including any script arranged in a syllabic chart. Evans' Latin Ojibwe alphabet, for example, was presented as a syllabary. Canadian Aboriginal ''syllabics'', the script itself, is thus distinct from a syllabary (syllabic chart) that displays them.Round and Square

While Greek, Latin, and Cyrillic haveserif

In typography, a serif () is a small line or stroke regularly attached to the end of a larger stroke in a letter or symbol within a particular font or family of fonts. A typeface or "font family" making use of serifs is called a serif typeface ( ...

and sans-serif

In typography and lettering, a sans-serif, sans serif (), gothic, or simply sans letterform is one that does not have extending features called "serifs" at the end of strokes. Sans-serif typefaces tend to have less stroke width variation than ...

forms, Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics generally do not. Instead, like proportional and monospaced font

A monospaced font, also called a fixed-pitch, fixed-width, or non-proportional font, is a font whose letters and characters each occupy the same amount of horizontal space. This contrasts with Typeface#Proportion, variable-width fonts, where t ...

s, Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics have a round form and a square form. Round form, known in Cree as , is akin to a proportional font, characterised by their smooth bowls, differing letter heights, and occupying a rectangular space. Round form syllabics are more commonly found east of Lake Winnipeg

Lake Winnipeg () is a very large, relatively shallow lake in North America, in the Canadian province of Manitoba. Its southern end is about north of the city of Winnipeg. Lake Winnipeg is Canada's sixth-largest freshwater lake and the third- ...

. Square form, known in Cree as , is akin to a monospace font, characterised by their cornered bowls, same letter heights, and occupying a square space. Square form syllabics are more commonly found west of Lake Winnipeg.

Syllabic alphabets

The inventory, form, and orthography of the script vary among all the Cree communities which use it. However, it was further modified to create specific alphabets for otherAlgonquian languages

The Algonquian languages ( ; also Algonkian) are a family of Indigenous languages of the Americas and most of the languages in the Algic language family are included in the group. The name of the Algonquian language family is distinguished from ...

, as well as for Inuktitut

Inuktitut ( ; , Inuktitut syllabics, syllabics ), also known as Eastern Canadian Inuktitut, is one of the principal Inuit languages of Canada. It is spoken in all areas north of the North American tree line, including parts of the provinces of ...

, which have significant phonological differences from Cree. There are two major variants of the script, Central Algonquian and Inuktitut. In addition, derivative scripts for Blackfoot and Athabaskan inherit at least some principals and letter forms from the Central Algonquian alphabet, though in Blackfoot most of the letters have been replaced with modified Latin. Each reflects a historical expansion of the writing system.

Central Algonquian

Cree and Ojibwe were the languages for which syllabics were designed, and they are the closest to the original pattern described by James Evans. The dialects differ slightly in their consonants, but where they share a sound, they generally use the same letter for it. Where they do not, a new letter was created, often by modifying another. In several Cree dialects ''ê'' has merged with the ''î'', and these use only three of the four vowel orientations.Eastern and western syllabics

When syllabics spread to Ojibwe and to those Cree dialects east of the Manitoba–Ontario border, a few changes occurred. For one, the diacritic used to mark non-final ''w'' moved from its position after the syllable to before it; thus western Cree is equivalent to the eastern Cree – both are pronounced ''mwa.'' Secondly, the special final forms of the consonants were replaced with superscript variants of the corresponding ''a'' series in Moose Cree and Moose Cree influenced areas, so that is ''ak'' and ''sap'' (graphically "aka" and "sapa"), rather than and ; among some of the Ojibwe communities superscript variants of the corresponding ''i'' series are found, especially in handwritten documents. Cree dialects of the western provinces preserve the Pitman-derived finals of the original script, though final ''y'' has become the more salient , to avoid confusion with the various dot diacritics. Additional consonant series are more pervasive in the east. :Additional consonant series

A few western charts show full ''l-'' and ''r-'' series, used principally for loan words. In a Roman Catholic variant, ''r-'' is a normal asymmetric form, derived by adding a stroke to ''c-,'' but ''l-'' shows an irregular pattern: Despite being asymmetrical, the forms are rotated only 90°, and ''li'' is a mirror image of what would be expected; it is neither an inversion nor a reflection of ''le,'' as in the other series, but rather a 180° rotation. :''Some western additions'' :: :: Series were added for ''l-, r-, sh- (š-)'' and ''f-'' in most eastern Cree dialects. ''R-'' is an inversion of the form of western ''l-,'' but now it is ''re'' that has the unexpected orientation. ''L-'' and ''f-'' are regular asymmetric and symmetric forms; although ''f-'' is actually asymmetric in form, it is derived from ''p-'' and therefore rotates 90° as ''p-'' does. Here is where the two algorithms to derive vowel orientations, which are equivalent for the symmetrical forms of the original script, come to differ: For the ᕙ ''f-'' series, as well as a rare ᕦ ''th-'' series derived from ᑕ ''t-,'' vowels of like height are derived via counter-clockwise rotation; however, an eastern ''sh-'' series, which perhaps not coincidentally resembles a Latin ''s,'' is rotated ''clockwise'' with the opposite vowel derivations: high ''-i'' from low ''-a'' and lower ( mid) ''-e'' from higher (mid) ''-o.'' The obsolete ''sp-'' series shows this to be the original design of the script, but Inuktitut, perhaps generalizing from the ᕙ series, which originated as ᐸ plus a circle at the start of the stroke used to write the letters, but as an independent form must be rotated in the opposite (counter-clockwise) direction, is consistently counter-clockwise. (The eastern Cree ''r-'' series can be seen as both of these algorithms applied to ''ro'' (bold), whereas western Cree ''l-'' can be seen as both applied to ''la'' (bold).) :''Some eastern additions'' :: :: There are minor variants within both eastern and western Cree. Woods Cree, for example, uses western Cree conventions, but has lost the ''e'' series, and has an additional consonant series, ''th- (ð-),'' which is a barred form of the ''y-'' series. :: Moose Cree, which uses eastern Cree conventions, has an ''-sk'' final that is composed of ''-s'' and ''-k,'' as in ᐊᒥᔉ "beaver", and final ''-y'' is written with a superscript ring, , rather than a superscript ''ya,'' which preserves, in a more salient form, the distinct final form otherwise found only in the west: ᐋᣁ''āshay'' "now". The Eastern Cree dialect has distinct labialized finals, ''-kw'' and ''-mw''; these are written with raised versions of the o-series rather than the usual a-series, as in ᒥᔅᑎᒄ "tree". This is motivated by the fact that the vowel ''o'' labializes the preceding consonant. Although in most respectsNaskapi

The Naskapi (Nascapi, Naskapee, Nascapee) are an Indigenous people of the Subarctic native to the historical region St'aschinuw (ᒋᑦ ᐊᔅᒋᓄᐤ, meaning 'our Clusivity, nclusiveland'), which was located in present day northern Qu ...

follows eastern Cree conventions, it does not mark vowel length at all and uses two dots, either placed above or before a syllable, to indicate a ''w'': ''wa,'' ''wo,'' ''twa,'' ''kwa,'' ''cwa'' (), ''mwa,'' ''nwa,'' ''swa,'' ''ywa.'' Since Naskapi ''s-'' consonant clusters are all labialized, ''sCw-,'' these also have the two dots: ''spwa, etc.'' There is also a labialized final sequence, ''-skw,'' which is a raised ''so-ko.''

See also:

* Ojibwe syllabics

* Oji-Cree language

Inuktitut

The eastern form of Cree syllabics was adapted to write theInuktitut

Inuktitut ( ; , Inuktitut syllabics, syllabics ), also known as Eastern Canadian Inuktitut, is one of the principal Inuit languages of Canada. It is spoken in all areas north of the North American tree line, including parts of the provinces of ...

dialects of Nunavut

Nunavut is the largest and northernmost Provinces and territories of Canada#Territories, territory of Canada. It was separated officially from the Northwest Territories on April 1, 1999, via the ''Nunavut Act'' and the Nunavut Land Claims Agr ...

(except for the extreme west, including Kugluktuk and Cambridge Bay) and Nunavik

Nunavik (; ; ) is an area in Canada which comprises the northern third of the province of Quebec, part of the Nord-du-Québec region and nearly coterminous with Kativik. Covering a land area of north of the 55th parallel, it is the homelan ...

in northern Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

. Unicode 14.0 added support for the Natsilingmiutut language of Western Nunavut. In other Inuit areas, various Latin alphabets are used.

Inuktitut has only three vowels, and thus only needs the ''a-, i-,'' and ''o''-series of Cree, the latter used for . The ''e''-series was originally used for the common diphthong

A diphthong ( ), also known as a gliding vowel or a vowel glide, is a combination of two adjacent vowel sounds within the same syllable. Technically, a diphthong is a vowel with two different targets: that is, the tongue (and/or other parts of ...

, but this was officially dropped in the 1960s so that Inuktitut would not have more characters than could be moulded onto an IBM Selectric typewriter

The IBM Selectric (a portmanteau of "selective" and "electric") was a highly successful line of electric typewriters introduced by IBM on 31 July 1961.

Instead of the "basket" of individual typebars that swung up to strike the ribbon and page ...

ball, with ''-ai'' written as an ''a''-series syllable followed by ''i.'' Recently the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami decided to restore the ai-series, and the Makivik Corporation has adopted this use in Nunavik

Nunavik (; ; ) is an area in Canada which comprises the northern third of the province of Quebec, part of the Nord-du-Québec region and nearly coterminous with Kativik. Covering a land area of north of the 55th parallel, it is the homelan ...

; it has not been restored in Nunavut

Nunavut is the largest and northernmost Provinces and territories of Canada#Territories, territory of Canada. It was separated officially from the Northwest Territories on April 1, 1999, via the ''Nunavut Act'' and the Nunavut Land Claims Agr ...

.

Inuktitut has more consonants than Cree, fifteen in its standardised form. As Inuktitut has no , the ''c'' series has been reassigned to the value ''g'' (). The ''y'' series is used for either ''y-'' or ''j-,'' since the difference is one of dialect; similarly with the ''s'' series, which stands for either ''s-'' or ''h-'', depending on the dialect. The eastern Cree ''l'' series is used: ''la,'' ''lu,'' ''li,'' ''lai;'' a stroke is added to these to derive the voiceless ''lh'' () series: ''lha, etc.'' The eastern Cree ''f'' series is used for Inuktitut ''v-'': ''va, etc.'' The eastern Cree ''r'' series is used for the very different Inuktitut sound, , which is also spelled ''r''. However, this has been regularized in form, with vowels of like height consistently derived through counter-clockwise rotation, and therefore ''rai'' the inversion of ''ri'':

::

The remaining sounds are written with digraphs. A raised ''ra'' is prefixed to the k-series to create a digraph for ''q'': ''qa, etc.''; the final is ''-q.'' A raised ''na-ga'' is prefixed to the g-series to create an ''ng'' () series: ''nga, etc.,'' and the ''na'' is doubled for geminate ''nng'' (): ''nnga.'' The finals are and .

In Nunavut, the ''h'' final has been replaced with Roman , which does not rotate, but in Nunavik a new series is derived by adding a stroke to the k-series: ''ha, etc.''

In the early years, Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

and Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

missionaries used slightly different forms of syllabics for Inuktitut. In modern times, however, these differences have disappeared. Dialectal variation across the syllabics-using part of the Inuit world has promoted an implicit diversity in spelling, but for the most part this has not had any impact on syllabics itself.

Derived scripts

At least two scripts derive from Cree syllabics, and share its principles, but have fundamentally different letter shapes or sound values.Blackfoot

Blackfoot, another Algonquian language, uses a syllabary developed in the 1880s that is quite different from the Cree and Inuktitut versions. Although borrowing from Cree the ideas of rotated and mirrored glyphs with final variants, most of the letter forms derive from the Latin script, with only some resembling Cree letters. Blackfoot has eight initial consonants, only two of which are identical in form to their Cree equivalents, ''se'' and ''ye'' (here only the vowels have changed). The other consonants were created by modifying letters of the Latin script to make the ''e'' series, or in three cases by taking Cree letters but reassigning them with new sound values according to which Latin letters they resembled. These are ''pe'' (from ), ''te'' (from ), ''ke'' (from ), ''me'' (from ), ''ne'' (from ), ''we'' (from ). There are also a number of distinct final forms. The four vowel positions are used for the three vowels and one of the diphthongs of Blackfoot. The script is largely obsolete.

Blackfoot, another Algonquian language, uses a syllabary developed in the 1880s that is quite different from the Cree and Inuktitut versions. Although borrowing from Cree the ideas of rotated and mirrored glyphs with final variants, most of the letter forms derive from the Latin script, with only some resembling Cree letters. Blackfoot has eight initial consonants, only two of which are identical in form to their Cree equivalents, ''se'' and ''ye'' (here only the vowels have changed). The other consonants were created by modifying letters of the Latin script to make the ''e'' series, or in three cases by taking Cree letters but reassigning them with new sound values according to which Latin letters they resembled. These are ''pe'' (from ), ''te'' (from ), ''ke'' (from ), ''me'' (from ), ''ne'' (from ), ''we'' (from ). There are also a number of distinct final forms. The four vowel positions are used for the three vowels and one of the diphthongs of Blackfoot. The script is largely obsolete.

Carrier and other Athabaskan

Athabaskan syllabic scripts were developed in the late 19th century by French Roman Catholic missionaries, who adapted this originally Protestant writing system to languages radically different from the Algonquian languages. Most

Athabaskan syllabic scripts were developed in the late 19th century by French Roman Catholic missionaries, who adapted this originally Protestant writing system to languages radically different from the Algonquian languages. Most Athabaskan languages

Athabaskan ( ; also spelled ''Athabascan'', ''Athapaskan'' or ''Athapascan'', and also known as Dene) is a large branch of the Na-Dene languages, Na-Dene language family of North America, located in western North America in three areal language ...

have more than four distinct vowels, and all have many more distinct consonants than Cree. This has meant the invention of a number of new consonant forms. Whereas most Athabaskan scripts, such as those for Slavey and Chipewyan

The Chipewyan ( , also called ''Denésoliné'' or ''Dënesųłı̨né'' or ''Dënë Sųłınë́'', meaning "the original/real people") are a Dene group of Indigenous Canadian people belonging to the Athabaskan language family, whose ancest ...

, bear a reasonably close resemblance to Cree syllabics, the Carrier (Dakelh

The Dakelh (pronounced ) or Carrier are a First Nations in Canada, First Nations Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous people living a large portion of the British Columbia Interior, Central Interior of British Columbia, Canada. The Dakel ...

) variant is highly divergent, and only one series – the series for vowels alone – resembles the original Cree form.

To accommodate six distinctive vowels, Dakelh supplements the four vowel orientations with a dot and a horizontal line in the rightward pointing forms: ᐊ ''a'', ᐅ ''ʌ'', ᐈ ''e'', ᐉ ''i'', ᐃ ''o'', and ᐁ ''u''.

One of the Chipewyan scripts is more faithful to western Cree. ( Sayisi Chipewyan is substantially more divergent.) It has the nine forms plus the western ''l'' and ''r'' series, though the rotation of the ''l-'' series has been made consistently counter-clockwise. The ''k-'' and ''n-'' series are more angular than in Cree: ''ki'' resembles Latin "P". The ''c'' series has been reassigned to ''dh''. There are additional series: a regular ''ch'' series (ᗴ ''cha'', ᗯ ''che'', ᗰ ''chi'', ᗱ ''cho''), graphically a doubled ''t''; and an irregular ''z'' series, where ''ze'' is derived by counter-clockwise rotation of ''za'', but ''zi'' by clockwise rotation of ''zo'':

::

Other series are formed from ''dh'' or ''t''. A mid-line final Cree ''t'' preceding ''dh'' forms ''th,'' a raised Cree final ''p'' following ''t'' forms ''tt,'' a stroke inside ''t'' forms ''tth'' (ᕮ ''ttha''), and a small ''t'' inside ''t'' forms ''ty'' (ᕳ ''tya''). Nasal vowels are indicated by a following Cree final ''k.''

Pollard script

The Pollard script, also known as Pollard Miao is anabugida

An abugida (; from Geʽez: , )sometimes also called alphasyllabary, neosyllabary, or pseudo-alphabetis a segmental Writing systems#Segmental writing system, writing system in which consonant–vowel sequences are written as units; each unit ...

invented by Methodist missionary Samuel Pollard. Pollard credited the basic idea of the script to the Cree syllabics, saying, "While working out the problem, we remembered the case of the syllabics used by a Methodist missionary among the Indians of North America, and resolved to do as he had done".

Current usage

At present, Canadian syllabics seems reasonably secure within the Cree, Oji-Cree, and Inuit communities. They appear somewhat more at risk among the Ojibwe, and seriously endangered for Athabaskan languages and Blackfoot.

In

At present, Canadian syllabics seems reasonably secure within the Cree, Oji-Cree, and Inuit communities. They appear somewhat more at risk among the Ojibwe, and seriously endangered for Athabaskan languages and Blackfoot.

In Nunavut

Nunavut is the largest and northernmost Provinces and territories of Canada#Territories, territory of Canada. It was separated officially from the Northwest Territories on April 1, 1999, via the ''Nunavut Act'' and the Nunavut Land Claims Agr ...

and Nunavik

Nunavik (; ; ) is an area in Canada which comprises the northern third of the province of Quebec, part of the Nord-du-Québec region and nearly coterminous with Kativik. Covering a land area of north of the 55th parallel, it is the homelan ...

, Inuktitut syllabics have official status. In Nunavut, laws, legislative debates and many other government documents must be published in Inuktitut in both syllabics and the Latin script. The rapid growth in the scope and quantity of material published in syllabics has, by all appearances, ended any immediate prospect of marginalisation for this writing system.

Within the Cree and Ojibwe language communities, the situation is less confident.

Cree syllabics use is vigorous in most communities where it has taken root. In many dialect areas, there are now standardised syllabics spellings. Nonetheless, there are now linguistically adequate standardised Roman writing systems for most if not all dialects.

Ojibwe speakers in the U.S. have never been heavy users of either Canadian Aboriginal syllabics or the Great Lakes Aboriginal syllabics and have now essentially ceased to use either of them at all. The "double vowel" Roman orthography developed by Charles Fiero and further developed by John Nichols is increasingly the standard in the U.S. and is beginning to penetrate into Canada, in part to prevent further atomisation of what is already a minority language. Nonetheless, Ojibwe syllabics are still in vigorous use in some parts of Canada.

Use in other communities is moribund.

Blackfoot syllabics have, for all intents and purposes, disappeared. Present day Blackfoot speakers use a Latin alphabet, and very few Blackfoot can still read—much less write—the syllabic system.

Among the Athabaskan languages, syllabics are still in use among the Yellowknives Dene in Yellowknife, Dettah, and Ndılǫ, Northwest Territories. Recently, two major reference works on the Tetsǫ́t'ıné language were published by the Alaska Native Language Center, using syllabics: a verb grammar and a dictionary. Syllabics are also still in use at Saint Kateri Tekakwitha Church in Dettah, where they use a revised version of the 1904 hymnbook. Young people learn syllabics both in school as well as through culture camps organized by the Language, Culture, and History Department.

No other Athabaskan version of the syllabics is known to be in vigorous use. In some cases, the languages themselves are on the brink of extinction. In other cases, syllabics has been replaced by a Latin alphabet. Many people—linguists and speakers of Athabaskan languages alike—feel that syllabics is ill-suited to these languages. The government of the Northwest Territories does not use syllabic writing for any of the Athabaskan languages on its territory, and native churches have generally stopped using them as well. Among Dakelh users, a well-developed Latin alphabet has effectively replaced syllabics. Very few people can read syllabics and none use them for routine writing. Syllabics are however popular in symbolic and artistic uses.

In the past, government policy towards syllabics has varied from indifference to open hostility. Until the late 20th century, government policy in Canada openly undermined native languages, and church organisations were often the only organised bodies using syllabics. Later, as governments became more accommodating of native languages, and in some cases even encouraged their use, it was widely believed that moving to a Latin alphabet was better, both for linguistic reasons and to reduce the cost of supporting multiple scripts.

At present, at least for Inuktitut and Algonquian languages, Canadian government tolerates, and in some cases encourages, the use of syllabics. The growth of Aboriginal nationalism in Canada and the devolution of many government activities to native communities has changed attitudes towards syllabics. In many places there are now standardisation bodies for syllabic spelling, and the Unicode standard supports a fairly complete set of Canadian syllabic characters for digital exchange. Syllabics are now taught in schools in Inuktitut-speaking areas, and are often taught in traditionally syllabics-using Cree and Ojibwe communities as well.

Although syllabic writing is not always practical (for example, with computer hardware or software limitations), and in many cases a Latin alphabet would be less costly to use, many native communities are strongly attached to syllabics. Even though it was originally the invention of European missionaries, many people consider syllabics a writing system that belongs to them, and associate Latin letters with linguistic assimilation.

Unified Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics in Unicode

The bulk of the characters, including all that are found in official documents, are encoded into three blocks in theUnicode

Unicode or ''The Unicode Standard'' or TUS is a character encoding standard maintained by the Unicode Consortium designed to support the use of text in all of the world's writing systems that can be digitized. Version 16.0 defines 154,998 Char ...

standard:

* Unified Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics (U+1400–U+167F)

* Unified Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics Extended (U+18B0–U+18FF)

* Unified Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics Extended-A (U+11AB0–U+11ABF)

These characters can be rendered with any appropriate font, including the freely available fonts listed below. In Microsoft Windows

Windows is a Product lining, product line of Proprietary software, proprietary graphical user interface, graphical operating systems developed and marketed by Microsoft. It is grouped into families and subfamilies that cater to particular sec ...

, built-in support was added through the Euphemia font introduced in Windows Vista

Windows Vista is a major release of the Windows NT operating system developed by Microsoft. It was the direct successor to Windows XP, released five years earlier, which was then the longest time span between successive releases of Microsoft W ...

, though this has incorrect forms for ''sha'' and ''shu''.

See also

*Inuktitut syllabics

Inuktitut syllabics (, or , ) is an abugida-type writing system used in Canada by the Inuktitut-speaking Inuit of the Provinces and territories of Canada, territory of Nunavut and the Nunavik region of Quebec. In 1976, the Language Commission of ...

* Kaktovik numerals

*Cree syllabics

Cree syllabics are the versions of Canadian Aboriginal syllabics used to write Cree language, Cree dialects, including the original syllabics system created for Cree and Ojibwe language, Ojibwe. There are two main varieties of syllabics for Cre ...

* Ojibwe syllabics

* Carrier syllabics

* Kamloops Wawa

* Mi'kmaq hieroglyphic writing

* Cherokee syllabary

Notes

References

*Comrie, Bernard. 2005. "Writing systems." Martin Haspelmath, Matthew Dryer, David Gile, Bernard Comrie, eds. ''The world atlas of language structures,'' 568–570. Oxford: Oxford University Press. *Murdoch, John. 1981''Syllabics: A successful educational innovation.''