The Brontës () were a 19th century literary family, born in the village of

Thornton and later associated with the village of

Haworth

Haworth ( , , ) is a village in West Yorkshire, England, in the Pennines south-west of Keighley, 8 miles (13 km) north of Halifax, west of Bradford and east of Colne in Lancashire. The surrounding areas include Oakworth and Oxenhop ...

in the

West Riding of Yorkshire

The West Riding of Yorkshire was one of three historic subdivisions of Yorkshire, England. From 1889 to 1974 the riding was an administrative county named County of York, West Riding. The Lord Lieutenant of the West Riding of Yorkshire, lieu ...

, England. The sisters,

Charlotte (1816–1855),

Emily (1818–1848) and

Anne

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female name Anna (name), Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah (given name), Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie (given name), Annie a ...

(1820–1849), are well-known poets and novelists. Like many contemporary female writers, they published their poems and novels under male pseudonyms: Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell respectively. Their stories attracted attention for their passion and originality immediately following their publication. Charlotte's ''

Jane Eyre

''Jane Eyre'' ( ; originally published as ''Jane Eyre: An Autobiography'') is a novel by the English writer Charlotte Brontë. It was published under her pen name "Currer Bell" on 19 October 1847 by Smith, Elder & Co. of London. The firs ...

'' was the first to know success, while Emily's ''

Wuthering Heights

''Wuthering Heights'' is the only novel by the English author Emily Brontë, initially published in 1847 under her pen name "Ellis Bell". It concerns two families of the landed gentry living on the West Yorkshire moors, the Earnshaws and the ...

'', Anne's ''

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall'' and other works were accepted as masterpieces of literature after their deaths.

The first Brontë children to be born to rector

Patrick Brontë

Patrick Brontë (, commonly ; born Patrick Brunty; 17 March 1777 – 7 June 1861) was an Irish Anglican minister and author who spent most of his adult life in England. He was the father of the writers Charlotte Brontë, Charlotte, Emily Bront ...

and his wife

Maria were

Maria (1814–1825) and

Elizabeth (1815–1825), who both died at young ages due to disease. Charlotte, Emily and Anne were then born within approximately four years. These three sisters and their brother,

Branwell (1817–1848), who was born after Charlotte and before Emily, were very close to each other. As children, they developed their imaginations first through oral storytelling and play, set in an intricate imaginary world, and then through the collaborative writing of increasingly complex stories set in their fictional world. The deaths of their mother and two older sisters marked them and influenced their writing profoundly, as did their isolated upbringing. They were raised in a religious family. The Brontë birthplace in

Thornton is a place of pilgrimage and their later home, the

parsonage

A clergy house is the residence, or former residence, of one or more priests or ministers of a given religion, serving as both a home and a base for the occupant's ministry. Residences of this type can have a variety of names, such as manse, pa ...

at

Haworth

Haworth ( , , ) is a village in West Yorkshire, England, in the Pennines south-west of Keighley, 8 miles (13 km) north of Halifax, west of Bradford and east of Colne in Lancashire. The surrounding areas include Oakworth and Oxenhop ...

in Yorkshire, now the

Brontë Parsonage Museum, has hundreds of thousands of visitors each year.

Origin of the name

The Brontë family can be traced to the

Irish clan

Irish clans are traditional kinship groups sharing a common surname and heritage and existing in a lineage-based society, originating prior to the 17th century. A clan (or in Irish, plural ) included the chief and his patrilineal relatives; howe ...

''Ó Pronntaigh'', which literally means "descendant of Pronntach". They were a family of hereditary scribes and literary men in

Fermanagh

Historically, Fermanagh (), as opposed to the modern County Fermanagh, was a kingdom of Gaelic Ireland, associated geographically with present-day County Fermanagh. ''Fir Manach'' originally referred to a distinct kin group of alleged Laigin or ...

. The version ''Ó Proinntigh'', which was first given by Patrick Woulfe in his ' ()

[Woulfe, Patrick, ''Sloinnte Gaedheal is Gall: Irish Names and Surnames'' (Baile Atha Cliath: M. H. Gill, 1922), p. 79] and reproduced without question by

Edward MacLysaght

Edgeworth Lysaght, later Edward Anthony Edgeworth Lysaght, and from 1920 Edward MacLysaght (; 6 November 1887 – 4 March 1986) was a genealogist of twentieth-century Ireland. His numerous books on Irish surnames built upon the work of Rev. Pat ...

, cannot be accepted as correct, as there were a number of well-known scribes with this name writing in

Irish in the 17th and 18th centuries and all of them used the spelling ''Ó Pronntaigh''. The name is derived from the word or , which is related to the word , meaning "giving" or "bestowal" ( is given as an

Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

version of in O'Reilly's ''Irish English Dictionary''.) Patrick Woulfe suggested that it was derived from (the

refectory

A refectory (also frater, frater house, fratery) is a dining room, especially in monastery, monasteries, boarding schools and academic institutions. One of the places the term is most often used today is in graduate seminary, seminaries. The name ...

of a

monastery

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of Monasticism, monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in Cenobitic monasticism, communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a ...

).

[ ''Ó Pronntaigh'' was earlier ]anglicised

Anglicisation or anglicization is a form of cultural assimilation whereby something non-English becomes assimilated into or influenced by the culture of England. It can be sociocultural, in which a non-English place adopts the English language ...

as ''Prunty'' and sometimes ''Brunty''.

At some point, Patrick Brontë

Patrick Brontë (, commonly ; born Patrick Brunty; 17 March 1777 – 7 June 1861) was an Irish Anglican minister and author who spent most of his adult life in England. He was the father of the writers Charlotte Brontë, Charlotte, Emily Bront ...

(born Brunty), the sisters' father, decided on the alternative spelling with the diaeresis over the terminal to indicate that the name has two syllables. Multiple theories exist to account for the change, including that he may have wished to hide his humble origins.[ As a ]man of letters

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the nature of reality, especially the nature of society and proposed solutions for its normative problems. Coming from the world of culture, either ...

, he would have been familiar with classical Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archa ...

and may have chosen the name after the Greek (). One view, which biographer C. K. Shorter proposed in 1896, is that he adapted his name to associate himself with Admiral Horatio Nelson, who was also Duke of Bronte

The Dukedom of Bronte ( ("Duchy of Bronte")) is a dukedom with the title Duke of Bronte (), referring to the town of Bronte, Sicily, Bronte in the province of Catania, Sicily. It was granted on 10 October 1799 at Palermo to the British Royal Navy ...

. One might also find evidence for this theory in Patrick Brontë's desire to associate himself with the Duke of Wellington

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and above sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they ar ...

in his form of dress.

Family tree

Members of the Brontë family

Patrick Brontë

Patrick Brontë

Patrick Brontë (, commonly ; born Patrick Brunty; 17 March 1777 – 7 June 1861) was an Irish Anglican minister and author who spent most of his adult life in England. He was the father of the writers Charlotte Brontë, Charlotte, Emily Bront ...

(17 March 1777 – 7 June 1861), the Brontë sisters' father, was born in Loughbrickland

Loughbrickland ( or ; ) is a small village in County Down, Northern Ireland, south of Banbridge on the A1 Belfast–Dublin road. In the 2011 Census it had a population of 693. Loughbrickland is within the Banbridge District.

History

Lough ...

, County Down

County Down () is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the nine counties of Ulster and one of the traditional thirty-two counties of Ireland. It covers an area of and has a population of 552,261. It borders County Antrim to the ...

, Ireland, of a family of farm workers of moderate means.Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

faith, whilst his father Hugh was a Protestant, and Patrick was brought up in his father's faith.

He was a bright young man and, after studying under the Rev. Thomas Tighe, won a scholarship to

He was a bright young man and, after studying under the Rev. Thomas Tighe, won a scholarship to St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College, formally the College of St John the Evangelist in the University of Cambridge, is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge, founded by the House of Tudor, Tudor matriarch L ...

. There, he studied divinity, ancient history and modern history. Attending Cambridge may have made him feel that his name was too Irish and he changed its spelling to Brontë (and its pronunciation accordingly), perhaps in honour of Horatio Nelson

Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte ( – 21 October 1805) was a Royal Navy officer whose leadership, grasp of strategy and unconventional tactics brought about a number of decisive British naval victories during the French ...

, whom Patrick admired. It is more likely, however, that his brother William was 'on the run' from the authorities for his involvement with the radical United Irishmen

The Society of United Irishmen was a sworn association, formed in the wake of the French Revolution, to secure Representative democracy, representative government in Ireland. Despairing of constitutional reform, and in defiance both of British ...

, leading Patrick to distance himself from the name Brunty. Having obtained a Bachelor of Arts degree, he was ordained on 10 August 1806. He is the author of ''Cottage Poems'' (1811), ''The Rural Minstrel'' (1814), numerous pamphlets, several newspaper articles and various rural poems.

In 1811, Patrick was appointed minister at Hartshead-cum-Clifton. In 1812, he met and married 29 year old Maria Branwell at Guiseley. In 1813, they moved to Clough House Hightown, Liversedge, West Riding of Yorkshire and by 1820 they had moved into the parsonage at Haworth, where he took up the post of perpetual curate

Perpetual curate was a class of resident parish priest or incumbent curate within the United Church of England and Ireland (name of the combined Anglican churches of England and Ireland from 1800 to 1871). The term is found in common use mainly ...

. (Haworth was an ancient chapelry in the large parish of Bradford

Bradford is a city status in the United Kingdom, city in West Yorkshire, England. It became a municipal borough in 1847, received a city charter in 1897 and, since the Local Government Act 1972, 1974 reform, the city status in the United Kingdo ...

, so he could not be rector or vicar.) They had six children. On the death of his wife in 1821, his sister-in-law, Elizabeth Branwell

Elizabeth Branwell (1776 – 25 October 1842) was the aunt of the literary sisters Charlotte Brontë, Emily Brontë and Anne Brontë.

Called 'Aunt Branwell', she helped raise the Brontë children after her sister, Maria Branwell, died in 1821 ...

, came from Penzance

Penzance ( ; ) is a town, civil parish and port in the Penwith district of Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is the westernmost major town in Cornwall and is about west-southwest of Plymouth and west-southwest of London. Situated in the ...

, Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

, to help him bring up the children. Open, intelligent, generous and dedicated to educating his children personally, he bought all the books and toys the children desired. He also accorded them great freedom and unconditional love, although he may have alienated them from the world due to his eccentric personal habits and peculiar theories of education.

After several failed attempts to remarry, Patrick accepted permanent widowerhood at the age of 47, and spent his time visiting the sick and the poor, giving sermons and administering communion. In so doing, he would often leave his children Maria, Elizabeth, Emily, Charlotte, Branwell and Anne alone with Elizabeth—Aunt Branwell and a maid, Tabitha Aykroyd (Tabby). Tabby helped relieve their possible boredom and loneliness especially by recounting local legends in her Yorkshire dialect as she tirelessly prepared the family's meals. Eventually, Patrick would survive his entire family. Six years after Charlotte's death, he died in 1861 at the age of 84.[ His son-in-law, the Rev. Arthur Bell Nicholls, would aid Mr Brontë at the end of his life as well.

]

Maria, née Branwell

Patrick's wife Maria Brontë

Maria Brontë (, ''commonly'' ; 23 April 1814 – 6 May 1825) was the eldest daughter of Patrick Brontë and Maria Brontë, née Branwell.

She was the elder sister of Elizabeth Brontë, the writers Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë, and t ...

, née Branwell (15 April 1783 – 15 September 1821), was born in Penzance

Penzance ( ; ) is a town, civil parish and port in the Penwith district of Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is the westernmost major town in Cornwall and is about west-southwest of Plymouth and west-southwest of London. Situated in the ...

, Cornwall, and came from a comfortably well-off, middle-class family. Her father had a flourishing tea and grocery store and had accumulated considerable wealth. Maria died at the age of 38 of uterine cancer

Uterine cancer, also known as womb cancer, includes two types of cancer that develop from the tissues of the uterus. Endometrial cancer forms from the lining of the uterus, and uterine sarcoma forms from the muscles or support tissue of the ute ...

. She married the same day as her younger sister Charlotte in the church at Guiseley

Guiseley ( ) is an area in the metropolitan borough of the City of Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. Historic counties of England, Historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, it is situated south of Otley and Menston and is now a north-west ...

after her fiancé had celebrated the union of two other couples. She was a literate and pious woman, known for her lively spirit, joyfulness and tenderness, and it was she who designed the samplers that are on display in the museum and had them embroidered by her children. She left memories with her husband and with Charlotte, the oldest surviving sibling, of a very vivacious woman. The younger ones, particularly Emily and Anne, admitted to retaining only vague images of their mother, especially of her suffering on her sickbed.

Elizabeth Branwell

Elizabeth Branwell (2 December 1776 – 29 October 1842) arrived from Penzance in 1821, aged 45, after her younger sister Maria's death, to help Patrick look after the children, to whom she was known as 'Aunt Branwell.' Elizabeth Branwell was a Methodist, though it seems that her denomination did not exert any influence on the children. It was Aunt Branwell who taught the children arithmetic, the alphabet, and how to sew, embroider and cross-stitch, skills appropriate for ladies. Aunt Branwell also gave them books and subscribed to ''Fraser's Magazine'', less interesting than ''Blackwood's'', but, nevertheless, providing plenty of material for discussion. She was a generous person who dedicated her life to her nieces and nephew, neither marrying nor returning to visit her relations in Cornwall. She probably told the children stories of events that had happened in Cornwall, such as raids by pirates in the eighteenth century, who carried off British residents to be enslaved in North Africa and Turkey; enslavement in Turkey is mentioned by Charlotte Brontë in ''Jane Eyre''. She died of bowel obstruction

Bowel obstruction, also known as intestinal obstruction, is a mechanical or Ileus, functional obstruction of the Gastrointestinal tract#Lower gastrointestinal tract, intestines which prevents the normal movement of the products of digestion. Ei ...

in October 1842, after a brief agony during which she was comforted by her beloved nephew Branwell. In her last will, Aunt Branwell left to her three nieces the considerable sum of £900 (about £95,700 in 2017 currency), which allowed them to resign from their low-paid jobs as governesses and teachers.

Children

* Maria (1814–1825), the eldest, was born in Clough House, Hightown, Liversedge, West Yorkshire, on 23 April 1814. She suffered from hunger, cold, and privation at

* Maria (1814–1825), the eldest, was born in Clough House, Hightown, Liversedge, West Yorkshire, on 23 April 1814. She suffered from hunger, cold, and privation at Cowan Bridge School

The Cowan Bridge School was a Clergy Daughters' School, founded in 1824, at Cowan Bridge in the English county of Lancashire. It was mainly for the daughters of middle class clergy and attended by the Brontë sisters. In the 1830s it moved t ...

. Charlotte described her as very lively, very sensitive, and particularly advanced in her reading. She returned from school with an advanced case of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

and died at Haworth aged 11 on 6 May 1825.

* Elizabeth (1815–1825), the second child, joined her sister Maria at Cowan Bridge where she suffered the same fate. Elizabeth was less vivacious than her brother and sisters and apparently less advanced for her age. She died on 15 June 1825 aged 10, within two weeks of returning home to her father.

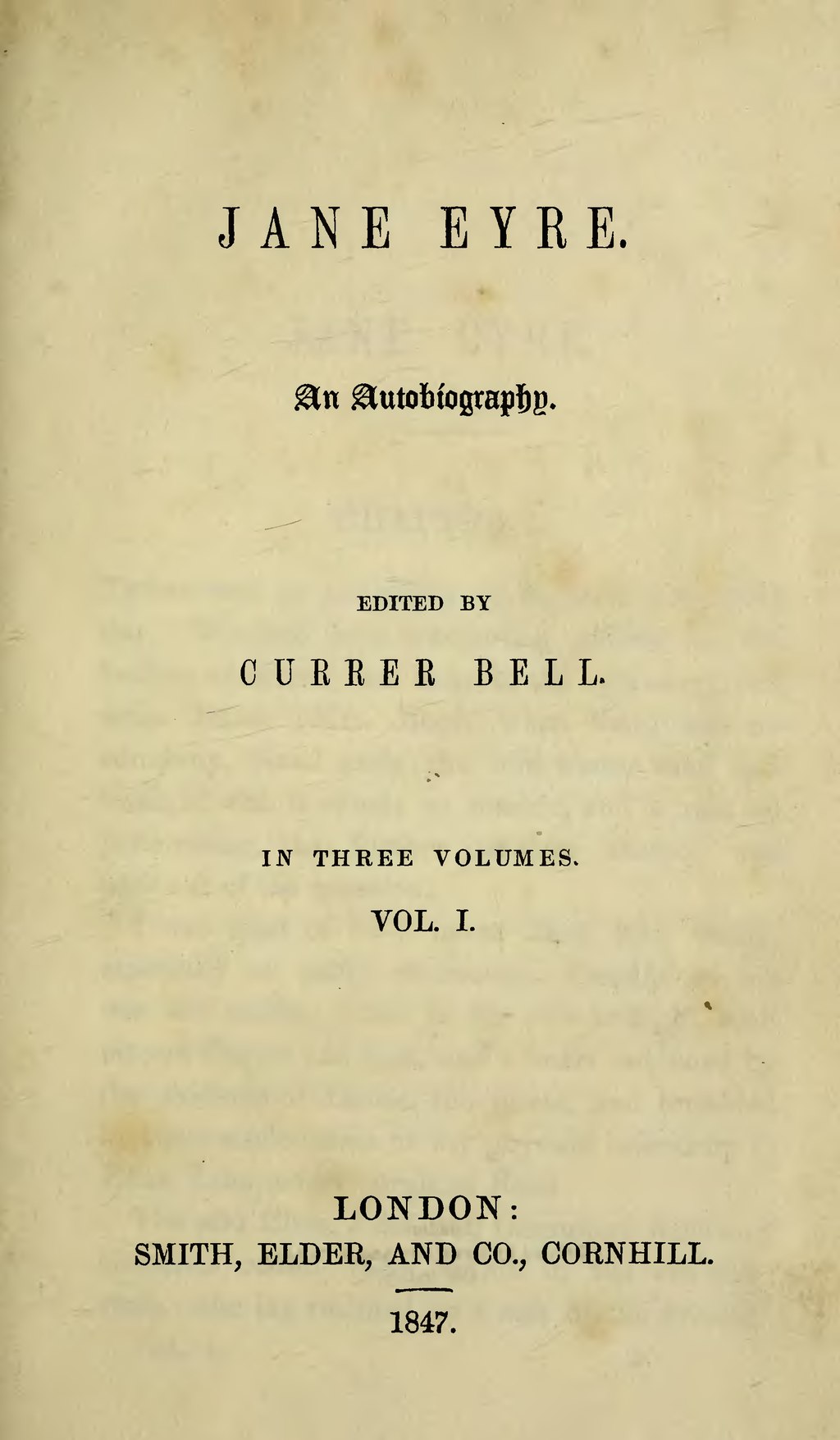

* Charlotte (1816–1855), born in Market Street, Thornton, near Bradford

Bradford is a city status in the United Kingdom, city in West Yorkshire, England. It became a municipal borough in 1847, received a city charter in 1897 and, since the Local Government Act 1972, 1974 reform, the city status in the United Kingdo ...

, West Riding of Yorkshire, on 21 April 1816, was a poet and novelist and is the author of ''Jane Eyre

''Jane Eyre'' ( ; originally published as ''Jane Eyre: An Autobiography'') is a novel by the English writer Charlotte Brontë. It was published under her pen name "Currer Bell" on 19 October 1847 by Smith, Elder & Co. of London. The firs ...

'', her best-known work and three other novels. She died on 31 March 1855, aged 38.

* Patrick Branwell (1817–1848) was born in Market Street, Thornton on 26 June 1817. Known as ''Branwell'', he was a painter, writer, and casual worker. He became addicted to alcohol and laudanum

Laudanum is a tincture of opium containing approximately 10% powdered opium by weight (the equivalent of 1% morphine). Laudanum is prepared by dissolving extracts from the opium poppy (''Papaver somniferum'') in alcohol (ethanol).

Reddish-br ...

and died in Haworth on 24 September 1848, aged 31.

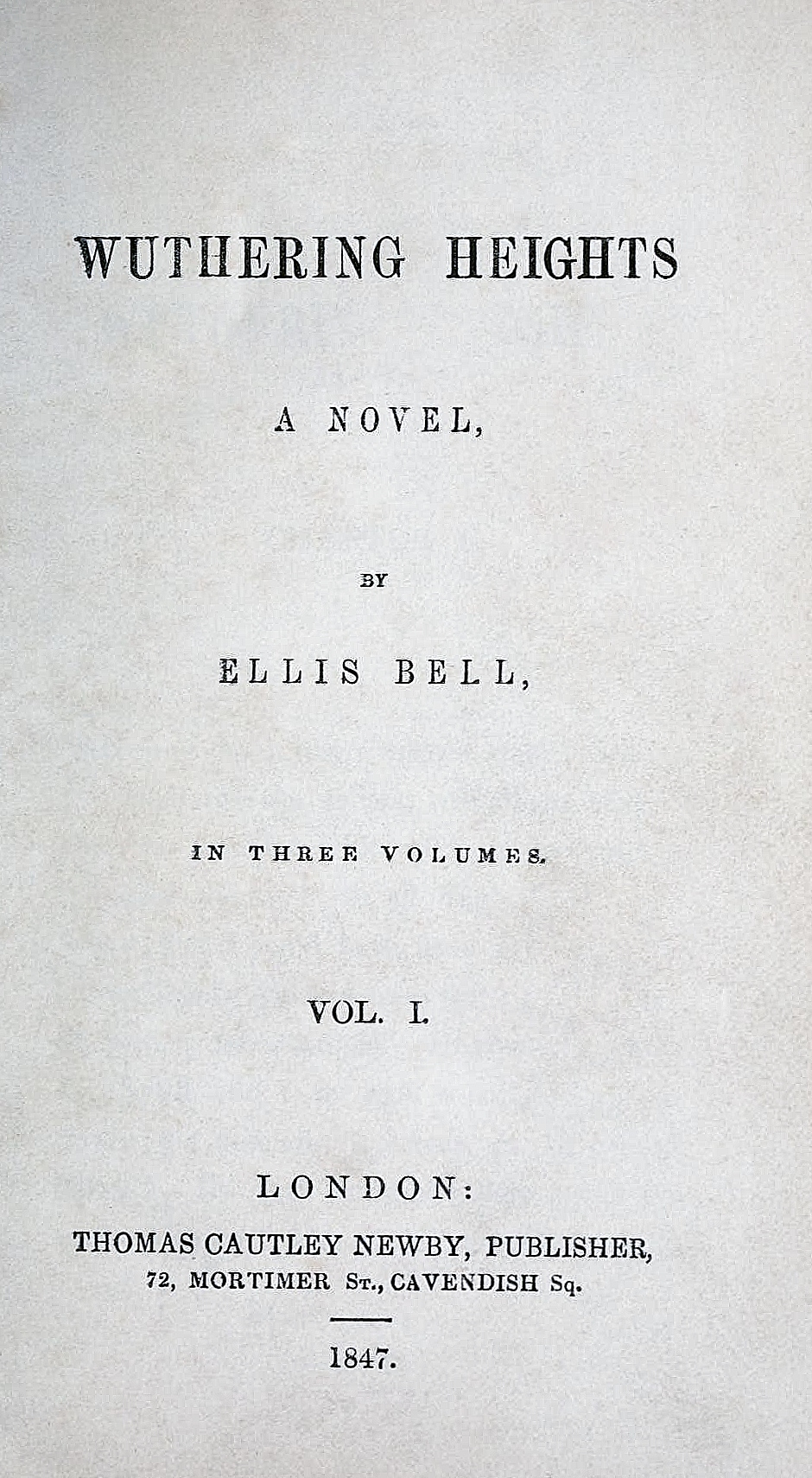

* Emily Jane (1818–1848), born in Market Street, Thornton, 30 July 1818, was a poet and novelist. She died in Haworth on 19 December 1848, aged 30. ''Wuthering Heights

''Wuthering Heights'' is the only novel by the English author Emily Brontë, initially published in 1847 under her pen name "Ellis Bell". It concerns two families of the landed gentry living on the West Yorkshire moors, the Earnshaws and the ...

'' was her only novel.

* Anne

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female name Anna (name), Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah (given name), Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie (given name), Annie a ...

(1820–1849), born in Market Street, Thornton on 17 January 1820, was a poet and novelist. She wrote a largely-autobiographical novel entitled ''Agnes Grey

''Agnes Grey, A Novel'' is the Debut novel, first novel by English author Anne Brontë (writing under the pen name of "Acton Bell"), first published in December 1847, and republished in a second edition in 1850. The novel follows Agnes Grey, a g ...

'', but her second novel, '' The Tenant of Wildfell Hall'' (1848), was far more ambitious. She died on 28 May 1849 in Scarborough Scarborough or Scarboro may refer to:

People

* Scarborough (surname)

* Earl of Scarbrough

Places Australia

* Scarborough, Western Australia, suburb of Perth

* Scarborough, New South Wales, suburb of Wollongong

* Scarborough, Queensland, sub ...

, aged 29.

Education

Cowan Bridge School

In 1824, the four eldest girls (excluding Anne) entered the Clergy Daughters' School at Cowan Bridge, which educated the children of less prosperous members of the clergy, and had been recommended to Mr Brontë. The following year, Maria and Elizabeth fell gravely ill and were removed from the school, later dying on 6 May and 15 June 1825, respectively. Charlotte and Emily were also withdrawn from the school and returned to Haworth. Charlotte expressed the traumatic impact that her sisters' deaths had on her in her future works. In ''Jane Eyre'', Cowan Bridge became Lowood, Maria inspired the young Helen Burns, the cruel mistress Miss Andrews inspired the headmistress Miss Scatcherd, and the tyrannical headmaster Rev. Carus Wilson, Mr Brocklehurst.

Tuberculosis, which afflicted Maria and Elizabeth in 1825, also caused the eventual deaths of three of the surviving Brontës: Branwell in September 1848, Emily in December 1848, and, finally, Anne in May 1849.

Patrick Brontë faced a challenge in arranging for the education of the girls of his family, which was barely middle class. They lacked significant connections and he could not afford the fees for them to attend an established school for young ladies. One solution was the schools where the fees were reduced to a minimum—so called "charity schools"—with a mission to assist families like those of the lower clergy.

(Barker had read in the ''Leeds Intelligencer'' of 6 November 1823 reports of cases in the Court of Commons in Bowes: he later read of other cases, of 24 November 1824 near Richmond, in the county of Yorkshire, where pupils had been discovered gnawed by rats and suffering so badly from malnutrition that some of them had lost their sight.) Yet for Patrick, there was nothing to suggest that the Reverend Carus Wilson's Clergy Daughters' School would not provide a good education and good care for his daughters. The school was not expensive and its patrons (supporters who allowed the school to use their names) were all respected people. Among these was the daughter of Hannah More

Hannah More (2 February 1745 – 7 September 1833) was an English religious writer, philanthropist, poet, and playwright in the circle of Johnson, Reynolds and Garrick, who wrote on moral and religious subjects. Born in Bristol, she taught at ...

, a religious author and philanthropist who took a particular interest in education. More was a close friend of the poet William Cowper

William Cowper ( ; – 25 April 1800) was an English poet and Anglican hymnwriter.

One of the most popular poets of his time, Cowper changed the direction of 18th-century nature poetry by writing of everyday life and scenes of the Engli ...

, who, like her, advocated extensive, proper and well-rounded education for young girls. The pupils included the offspring of different prelates and even certain acquaintances of Patrick Brontë including William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 1759 – 29 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist, and a leader of the movement to abolish the Atlantic slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780 ...

, young women whose fathers had also been educated at St John's College, Cambridge. Thus Brontë believed Wilson's school to have many of the necessary guarantees needed for his daughters to receive proper schooling.

John Bradley

In 1829–30, Patrick Brontë engaged John Bradley, an artist from neighbouring Keighley

Keighley ( ) is a market town and a civil parishes in England, civil parish

in the City of Bradford Borough of West Yorkshire, England. It is the second-largest settlement in the borough, after Bradford.

Keighley is north-west of Bradford, n ...

, as drawing-master for the children. Bradley was an artist of some local repute rather than a professional instructor, but he may well have fostered Branwell's enthusiasm for art and architecture.

Miss Wooler's school

In 1831, fourteen-year-old Charlotte was enrolled at the school of Miss Wooler in Roe Head, Mirfield

Mirfield () is a town and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Metropolitan Borough of Kirklees, West Yorkshire, England. Historic counties of England, Historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, it is on the A644 road (Great B ...

. Patrick could have sent his daughter to a less costly school in Keighley

Keighley ( ) is a market town and a civil parishes in England, civil parish

in the City of Bradford Borough of West Yorkshire, England. It is the second-largest settlement in the borough, after Bradford.

Keighley is north-west of Bradford, n ...

nearer home but Miss Wooler and her sisters had a good reputation and he remembered the building, which he passed when strolling around the parishes of Kirklees

Kirklees is a metropolitan borough of West Yorkshire, England. The borough comprises the ten towns of Batley, Birstall, West Yorkshire, Birstall, Cleckheaton, Dewsbury, Heckmondwike, Holmfirth, Huddersfield, Meltham, Mirfield and Slaithwaite. It ...

, Dewsbury

Dewsbury is a market town in the Metropolitan Borough of Kirklees in West Yorkshire, England. It lies on the River Calder, West Yorkshire, River Calder and on an arm of the Calder and Hebble Navigation waterway. It is to the west of Wakefield, ...

and Hartshead-cum-Clifton where he was vicar. Margaret Wooler showed fondness towards the sisters and she accompanied Charlotte to the altar at her marriage. Patrick's choice of school was excellent—Charlotte was happy there and studied well. She made many lifelong friends, in particular Ellen Nussey and Mary Taylor who later went to New Zealand before returning to England. Charlotte returned from Roe Head in June 1832, missing her friends, but happy to rejoin her family.

Three years later, Miss Wooler offered her former pupil a position as her assistant. The family decided that Emily would accompany her to pursue studies that would otherwise have been unaffordable. Emily's fees were partly covered by Charlotte's salary. Emily was 17 and it was the first time she had left Haworth since leaving Cowan Bridge. On 29 July 1835, the sisters left for Roe Head. The same day, Branwell wrote a letter to the Royal Academy of Art in London, to present several of his drawings as part of his candidature as a probationary student.

Charlotte taught, and wrote about her students without much sympathy. Emily did not settle: after three months her health seemed to decline and she had to be taken home to the parsonage. Anne took her place and stayed until Christmas 1837.

Charlotte avoided boredom by following the developments of the imaginary Empire of Angria—invented by Charlotte and Branwell—that she received in letters from her brother. During holidays at Haworth, she wrote long narratives while being reproached by her father who wanted her to become more involved in parish affairs. These were coming to a head over the imposition of the Church of England rates, a local tax levied on parishes where the majority of the population were dissenters. In the meantime, Miss Wooler moved to Heald's House, at Dewsbury Moor, where Charlotte complained about the humidity that made her unwell. Upon leaving the establishment in 1838 Miss Wooler presented her with a parting gift of ''The Vision of Don Roderick and Rokeby'', a collection of poems by Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European literature, European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'' (18 ...

.

Literary evolution

The children became interested in writing from an early age, initially as a game. They all displayed a talent for narrative, but for the younger ones it became a pastime to develop them. At the centre of the children's creativity were twelve wooden soldiers which Patrick Brontë gave to Branwell at the beginning of June 1826.

Literary and artistic influence

These fictional worlds were the product of fertile imagination fed by reading, discussion and a passion for literature. Far from suffering from the negative influences that never left them and which were reflected in the works of their later, more mature years, the Brontë children absorbed them eagerly.

Press

The periodicals that Patrick Brontë read were a mine of information for his children. The '' Leeds Intelligencer'' and ''Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine'', conservative and well written, but better than the ''Quarterly Review

The ''Quarterly Review'' was a literary and political periodical founded in March 1809 by London publishing house John Murray. It ceased publication in 1967. It was referred to as ''The London Quarterly Review'', as reprinted by Leonard Scott, f ...

'' that defended the same political ideas whilst addressing a less-refined readership (the reason Mr. Brontë did not read it), were exploited in every detail. ''Blackwood's Magazine

''Blackwood's Magazine'' was a British magazine and miscellany printed between 1817 and 1980. It was founded by publisher William Blackwood and originally called the ''Edinburgh Monthly Magazine'', but quickly relaunched as ''Blackwood's Edinb ...

'', in particular, was not only the source of their knowledge of world affairs, but also provided material for the Brontës' early writing. For instance, an article in the June 1826 number of ''Blackwood's'', provides commentary on new discoveries from the exploration of central Africa

Central Africa (French language, French: ''Afrique centrale''; Spanish language, Spanish: ''África central''; Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''África Central'') is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries accordin ...

. The map included with the article highlights geographical features the Brontës reference in their tales: the Jibbel Kumera (the Mountains of the Moon), Ashantee, and the rivers Niger

Niger, officially the Republic of the Niger, is a landlocked country in West Africa. It is a unitary state Geography of Niger#Political geography, bordered by Libya to the Libya–Niger border, north-east, Chad to the Chad–Niger border, east ...

and Calabar

Calabar (also referred to as Callabar, Calabari, Calbari, Cali and Kalabar) is the capital city of Cross River State, Nigeria. It was originally named Akwa Akpa, in the Efik language, as the Efik people dominate this area. The city is adjac ...

. The author also advises the British to expand into Africa from Fernando Po, where, Christine Alexander notes, the Brontë children locate the Great Glass Town. Their knowledge of geography was completed by Goldsmith's ''Grammar of General Geography'', which the Brontës owned and annotated heavily.

Lord Byron

From 1833, Charlotte and Branwell's Angrian tales begin to feature Byronic hero

The Byronic hero is a variant of the Romantic hero as a type of character, named after the English Romantic poet Lord Byron. Historian and critic Lord Macaulay described the character as "a man proud, moody, cynical, with defiance on his bro ...

es who have a strong sexual magnetism and passionate spirit, and demonstrate arrogance and even black-heartedness. Again, it is in an article in ''Blackwood's Magazine'' from August 1825 that they discover the poet for the first time; he had died the previous year. From this moment, the name Byron became synonymous with all the prohibitions and audacities as if it had stirred up the very essence of the rise of those forbidden things. Branwell's Charlotte Zamorna, one of the heroes of '' Verdopolis'', tends towards increasingly ambiguous behaviour, and the same influence and evolution recur with the Brontës, especially in the characters of Heathcliff in ''Wuthering Heights

''Wuthering Heights'' is the only novel by the English author Emily Brontë, initially published in 1847 under her pen name "Ellis Bell". It concerns two families of the landed gentry living on the West Yorkshire moors, the Earnshaws and the ...

'', and Mr. Rochester in ''Jane Eyre

''Jane Eyre'' ( ; originally published as ''Jane Eyre: An Autobiography'') is a novel by the English writer Charlotte Brontë. It was published under her pen name "Currer Bell" on 19 October 1847 by Smith, Elder & Co. of London. The firs ...

'', who display the traits of a Byronic hero

The Byronic hero is a variant of the Romantic hero as a type of character, named after the English Romantic poet Lord Byron. Historian and critic Lord Macaulay described the character as "a man proud, moody, cynical, with defiance on his bro ...

. Numerous other works left their mark on the Brontës—the '' Thousand and One Nights'', for example, which inspired jinn

Jinn or djinn (), alternatively genies, are supernatural beings in pre-Islamic Arabian religion and Islam.

Their existence is generally defined as parallel to humans, as they have free will, are accountable for their deeds, and can be either ...

in which they became themselves in the centre of their kingdoms, while adding a touch of exoticism.

John Martin

The children's imagination was also influenced by three prints of engravings in

The children's imagination was also influenced by three prints of engravings in mezzotint

Mezzotint is a monochrome printmaking process of the intaglio (printmaking), intaglio family. It was the first printing process that yielded half-tones without using line- or dot-based techniques like hatching, cross-hatching or stipple. Mezzo ...

by John Martin around 1820. Charlotte and Branwell made copies of the prints ''Belshazzar's Feast

Belshazzar's feast, or the story of the writing on the wall, chapter 5 in the Book of Daniel, tells how Neo-Babylonian royal Belshazzar holds a great feast and drinks from the vessels that had been looted in the destruction of the First Temple. ...

'', ''Déluge'', and '' Joshua Commanding the Sun to Stand Still upon Gibeon'' (1816), which hung on the walls of the parsonage.John Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet, polemicist, and civil servant. His 1667 epic poem ''Paradise Lost'' was written in blank verse and included 12 books, written in a time of immense religious flux and politic ...

's ''Paradise Lost

''Paradise Lost'' is an Epic poetry, epic poem in blank verse by the English poet John Milton (1608–1674). The poem concerns the Bible, biblical story of the fall of man: the temptation of Adam and Eve by the fallen angel Satan and their ex ...

''. Together with Byron, John Martin seems to have been one of the artistic influences essential to the Brontës' universe.

Anne's morals and realism

The influence revealed by ''Agnes Grey

''Agnes Grey, A Novel'' is the Debut novel, first novel by English author Anne Brontë (writing under the pen name of "Acton Bell"), first published in December 1847, and republished in a second edition in 1850. The novel follows Agnes Grey, a g ...

'' and '' The Tenant of Wildfell Hall'' is much less clear. Anne's works are largely founded on her experience as a governess and on that of her brother's decline. Furthermore, they demonstrate her conviction, a legacy from her father, that books should provide moral education. This sense of moral duty and the need to record it, are more evident in ''The Tenant of Wildfell Hall''. The influence of the gothic novels of Ann Radcliffe

Ann Radcliffe (née Ward; 9 July 1764 – 7 February 1823) was an English novelist who pioneered the Gothic fiction, Gothic novel, and a minor poet. Her fourth and most popular novel, ''The Mysteries of Udolpho'', was published in 1794. She i ...

, Horace Walpole

Horatio Walpole, 4th Earl of Orford (; 24 September 1717 – 2 March 1797), better known as Horace Walpole, was an English Whig politician, writer, historian and antiquarian.

He had Strawberry Hill House built in Twickenham, southwest London ...

, Gregory "Monk" Lewis and Charles Maturin

Charles Robert Maturin, also known as C. R. Maturin (25 September 1780 – 30 October 1824), was an Irish Protestant clergyman (ordained in the Church of Ireland) and a writer of Gothic fiction, Gothic plays and novels.Chris Morgan, "Maturin, C ...

is noticeable, and that of Walter Scott too, if only because the heroine, abandoned and left alone, resists importunities not only through her almost supernatural talents, but by her powerful temperament.

''Jane Eyre

''Jane Eyre'' ( ; originally published as ''Jane Eyre: An Autobiography'') is a novel by the English writer Charlotte Brontë. It was published under her pen name "Currer Bell" on 19 October 1847 by Smith, Elder & Co. of London. The firs ...

'', ''Agnes Grey'', ''The Tenant of Wildfell Hall'', '' Shirley'', '' Villette'' and even '' The Professor'' present a linear structure concerning characters who advance through life after several trials and tribulations, to find a kind of happiness in love and virtue, recalling works of religious inspiration of the 17th century such as John Bunyan

John Bunyan (; 1628 – 31 August 1688) was an English writer and preacher. He is best remembered as the author of the Christian allegory ''The Pilgrim's Progress'', which also became an influential literary model. In addition to ''The Pilgrim' ...

's ''The Pilgrim's Progress

''The Pilgrim's Progress from This World, to That Which Is to Come'' is a 1678 Christian allegory written by John Bunyan. It is commonly regarded as one of the most significant works of Protestant devotional literature and of wider early moder ...

'' or his ''Grace abounding to the Chief of Sinners''. In a more profane manner, the hero or heroine follows a picaresque

The picaresque novel (Spanish: ''picaresca'', from ''pícaro'', for ' rogue' or 'rascal') is a genre of prose fiction. It depicts the adventures of a roguish but appealing hero, usually of low social class, who lives by his wits in a corrupt ...

itinerary such as in Miguel de Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra ( ; ; 29 September 1547 (assumed) – 22 April 1616 Old Style and New Style dates, NS) was a Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelist ...

(1547–1616), Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; 1660 – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, merchant and spy. He is most famous for his novel ''Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its number of translati ...

(1660–1731), Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding (22 April 1707 – 8 October 1754) was an English writer and magistrate known for the use of humour and satire in his works. His 1749 comic novel ''The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling'' was a seminal work in the genre. Along wi ...

(1707–1764) and Tobias Smollett

Tobias George Smollett (bapt. 19 March 1721 – 17 September 1771) was a Scottish writer and surgeon. He was best known for writing picaresque novels such as ''The Adventures of Roderick Random'' (1748), ''The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle'' ...

(1721–1771). This lively tradition continued into the 19th century with the ''rags to riches'' genre to which almost all the great Victorian romancers have contributed. The protagonist is thrown by fate into poverty and after many difficulties achieves a golden happiness. Often an artifice is employed to effect the passage from one state to another such as an unexpected inheritance, a miraculous gift, grand reunions, etc,[See '']Oliver Twist

''Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress'', is the second novel by English author Charles Dickens. It was originally published as a serial from 1837 to 1839 and as a three-volume book in 1838. The story follows the titular orphan, who, ...

'', ''David Copperfield

''David Copperfield''Dickens invented over 14 variations of the title for this work; see is a novel by English author Charles Dickens, narrated by the eponymous David Copperfield, detailing his adventures in his journey from infancy to matur ...

'', ''Great Expectations

''Great Expectations'' is the thirteenth novel by English author Charles Dickens and his penultimate completed novel. The novel is a bildungsroman and depicts the education of an orphan nicknamed Pip. It is Dickens' second novel, after ''Dav ...

'', just to mention Charles Dickens and in a sense it is the route followed by Charlotte's and Anne's protagonists, even if the riches they win are more those of the heart than of the wallet. Apart from its Gothic elements, ''Wuthering Heights'' moves like a Greek tragedy and possesses its music, the cosmic dimensions of the epics of John Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet, polemicist, and civil servant. His 1667 epic poem ''Paradise Lost'' was written in blank verse and included 12 books, written in a time of immense religious flux and politic ...

, and the power of the Shakespearian theatre. One can hear the echoes of ''King Lear

''The Tragedy of King Lear'', often shortened to ''King Lear'', is a Shakespearean tragedy, tragedy written by William Shakespeare. It is loosely based on the mythological Leir of Britain. King Lear, in preparation for his old age, divides his ...

'' as well as the completely different characters of ''Romeo and Juliet

''The Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet'', often shortened to ''Romeo and Juliet'', is a Shakespearean tragedy, tragedy written by William Shakespeare about the romance between two young Italians from feuding families. It was among Shakespeare's ...

''. The Brontës were also seduced by the writings of Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European literature, European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'' (18 ...

, and in 1834 Charlotte exclaimed, "For fiction, read Walter Scott and only him—all novels after his are without value."

Governesses and Charlotte's idea

Early teaching opportunities

Through their father's influence and their own intellectual curiosity, they were able to benefit from an education that placed them among knowledgeable people, but Mr Brontë's emoluments were modest. The only options open to the girls were either marriage or a choice between the professions of school mistress or

Through their father's influence and their own intellectual curiosity, they were able to benefit from an education that placed them among knowledgeable people, but Mr Brontë's emoluments were modest. The only options open to the girls were either marriage or a choice between the professions of school mistress or governess

A governess is a woman employed as a private tutor, who teaches and trains a child or children in their home. A governess often lives in the same residence as the children she is teaching; depending on terms of their employment, they may or ma ...

. The Brontë sisters found positions in families wherein they educated often rebellious young children, or found employment as school teachers. The possibility of becoming a paid companion to a rich and solitary woman might have been a fall-back role but one that would have probably bored any of the sisters intolerably. Janet Todd

Janet Margaret Todd (born 10 September 1942) is a British academic and author. She was educated at Cambridge University and the University of Florida, where she undertook a doctorate on the poet John Clare. Much of her work concerns Mary Wol ...

's ''Mary Wollstonecraft, a revolutionary life'' mentions the predicament.

Only Emily never became a governess. Her sole professional experience would be an experiment in teaching during six months of intolerable exile in Miss Patchett's school at Law Hill (between

Only Emily never became a governess. Her sole professional experience would be an experiment in teaching during six months of intolerable exile in Miss Patchett's school at Law Hill (between Haworth

Haworth ( , , ) is a village in West Yorkshire, England, in the Pennines south-west of Keighley, 8 miles (13 km) north of Halifax, west of Bradford and east of Colne in Lancashire. The surrounding areas include Oakworth and Oxenhop ...

and Halifax). In contrast, Charlotte had teaching positions at Miss Margaret Wooler's school and in Brussels with the Hegers. She became governess to the Sidgwicks, the Stonegappes and the Lotherdales where she worked for several months in 1839, then with Mrs White, at Upperhouse House, Rawdon, from March to September 1841. Anne became a governess and worked for Mrs Ingham,

Working as governesses

The family's finances did not flourish, and Aunt Branwell spent the money with caution. Emily had a visceral need of her home and the countryside that surrounded it, and to leave it would cause her to languish and wither.[Which had happened whenever she left Haworth for any length of time such as at Miss Wooler's school, or when teaching in Law Hill, and during her stay in Brussels.] In the meantime, Charlotte had an idea that would place all the advantages on her side. On advice from her father and friends, she thought that she and her sisters had the intellectual capacity to create a school for young girls in the parsonage where their

In the meantime, Charlotte had an idea that would place all the advantages on her side. On advice from her father and friends, she thought that she and her sisters had the intellectual capacity to create a school for young girls in the parsonage where their Sunday School

]

A Sunday school, sometimes known as a Sabbath school, is an educational institution, usually Christianity, Christian in character and intended for children or neophytes.

Sunday school classes usually precede a Sunday church service and are u ...

classes took place. It was agreed to offer the future pupils the opportunity of correctly learning modern languages and that preparation for this should be done abroad, which led to a further decision. Among the possibilities, Paris and Lille were considered, but were rejected due to aversion to the French. Indeed, the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

had not been forgotten by the Tory

A Tory () is an individual who supports a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalist conservatism which upholds the established social order as it has evolved through the history of Great Britain. The To ...

-spirited and deeply conservative girls. On the recommendation of a pastor based in Brussels, who wanted to be of help, Belgium was chosen, where they could also study German and music. Aunt Branwell provided the funds for the Brussels project.

School project and study trip to Brussels

Charlotte's and Emily's journey to Brussels

Emily and Charlotte arrived in Brussels in February 1842 accompanied by their father. Once there, they enrolled at Monsieur and Madame Heger's boarding school in the Rue d'Isabelle, for six months. Claire Heger was the second wife of Constantin, and it was she who founded and directed the school while Constantin had the responsibility for the higher French classes. According to Miss Wheelwright, a former pupil, he had the intellect of a genius. He was passionate about his auditorium, demanding many lectures, perspectives, and structured analyses. He was also a good-looking man with regular features, bushy hair, very black whiskers, and wore an excited expression while sounding forth on great authors about whom he invited his students to make a pastiche

A pastiche () is a work of visual art, literature, theatre, music, or architecture that imitates the style or character of the work of one or more other artists. Unlike parody, pastiche pays homage to the work it imitates, rather than mocking ...

on general or philosophical themes.[Nicoll, W. Robertson (1908) ''The Complete Poems of Emily Brontë – Introductory Essay'', p. XXI.] The lessons, especially those of Constantin Heger, were very much appreciated by Charlotte, and the two sisters showed exceptional intelligence, although Emily hardly liked her teacher and was somewhat rebellious.

The lessons, especially those of Constantin Heger, were very much appreciated by Charlotte, and the two sisters showed exceptional intelligence, although Emily hardly liked her teacher and was somewhat rebellious.

Return and recall

The death of their aunt in October of the same year forced them to return once more to Haworth. Aunt Branwell had left all her worldly goods in equal shares to her nieces and to Eliza Kingston, a cousin in Penzance, which had the immediate effect of purging all their debts and providing a small reserve of funds. Nevertheless, they were asked to return to the Heger's boarding school in Brussels as they were regarded as being competent and were needed. They were each offered teaching posts in the boarding school, English for Charlotte and music for Emily. However, Charlotte returned alone to Belgium in January 1843. Emily remained critical of Monsieur Heger, in spite of the excellent opinion he held of her. He later stated that she 'had the spirit of a man', and would probably become a great traveller due to her being gifted with a superior faculty of reason that allowed her to deduce ancient knowledge from new spheres of knowledge, and her unbending willpower would have triumphed over all obstacles.

Charlotte returns

Almost a year to the day, enamoured for some time for Monsieur Heger, Charlotte resigned and returned to Haworth. Her life at the school had not been without suffering, and on one occasion she ventured into the cathedral and entered a confessional. She may have had intention of converting to Catholicism, but it would only have been for a short time. During her absence, life at Haworth had become more difficult. Mr. Brontë had lost his sight although his cataract had been operated on with success in Manchester, and it was there in August 1846, when Charlotte arrived at his bedside that she began to write ''Jane Eyre''. Meanwhile, her brother Branwell fell into a rapid decline punctuated by dramas, drunkenness and delirium. Due partly to Branwell's poor reputation, the school project failed and was abandoned.

Charlotte wrote four long, very personal, and sometimes vague letters to Monsieur Heger that never received replies. The extent of Charlotte Brontë's feelings for Heger were not fully realised until 1913, when her letters to him were published for the first time. Heger had first shown them to Mrs. Gaskell when she visited him in 1856 while researching her biography '' The Life of Charlotte Brontë'', but she concealed their true significance. These letters, referred to as the "Heger Letters", had been ripped up at some stage by Heger, but his wife had retrieved the pieces from the wastepaper bin and meticulously glued or sewn them back together. Paul Héger, Constantin's son, and his sisters gave these letters to the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

,The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' newspaper.

Brontë sisters' literary career

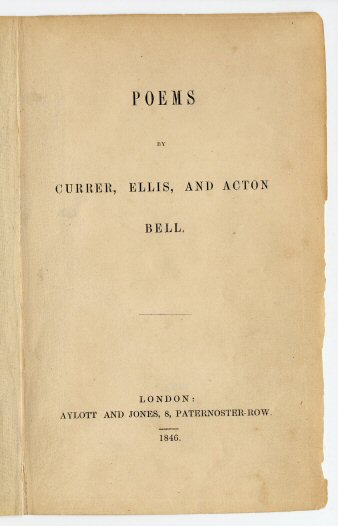

First publication: ''Poems'', by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell

The writing that had begun so early never left the family. Charlotte had ambition like her brother, and wrote to the poet laureate

The writing that had begun so early never left the family. Charlotte had ambition like her brother, and wrote to the poet laureate Robert Southey

Robert Southey (; 12 August 1774 – 21 March 1843) was an English poet of the Romantic poetry, Romantic school, and Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom, Poet Laureate from 1813 until his death. Like the other Lake Poets, William Wordsworth an ...

to submit several poems in his style (though Branwell was kept at a distance from her project). She received a hardly encouraging reply after several months. Southey, still illustrious today although his star has somewhat waned, was one of the great figures of English Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

, along with William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poetry, Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romanticism, Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication ''Lyrical Balla ...

and Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge ( ; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poets with his friend William Wordsworth ...

, and he shared the prejudice of the times; literature, or more particularly poetry (for women had been publishing fiction and enjoying critical, popular and economic success for over a century by this time), was considered a man's business, and not an appropriate occupation for ladies.

However, Charlotte did not allow herself to be discouraged. Furthermore, coincidence came to her aid. One day in autumn 1845 while alone in the dining room she noticed a small notebook lying open in the drawer of Emily's portable writing desk and "of my sister Emily's handwriting". She read it and was dazzled by the beauty of the poems that she did not know. The discovery of this treasure was what she recalled five years later, and according to Juliet Barker, she erased the excitement that she had felt "more than surprise ..., a deep conviction that these were not common effusions, nor at all like the poetry women generally write. I thought them condensed and terse, vigorous and genuine. To my ear, they had a peculiar music—wild, melancholy, and elevating." In the following paragraph Charlotte describes her sister's indignant reaction at her having ventured into such an intimate realm with impunity. It took Emily hours to calm down and days to be convinced to publish the poems.

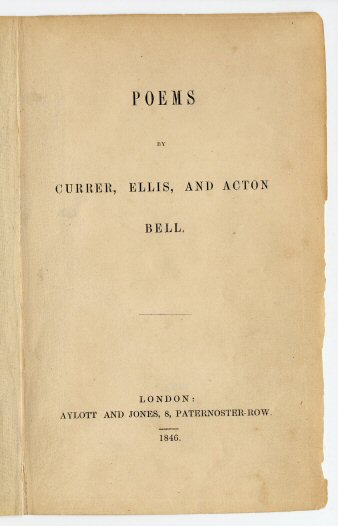

Charlotte envisaged a joint publication by the three sisters. Anne was easily won over to the project, and the work was shared, compared and edited. Once the poems had been chosen, nineteen for Charlotte and twenty-one each for Anne and Emily, Charlotte went about searching for a publisher. She took advice from William and Robert Chambers of Edinburgh, directors of one of their favourite magazines, ''Chambers's Edinburgh Journal''. It is thought, although no documents exist to support the claim, that they advised the sisters to contact Aylott & Jones, a small publishing house at 8, Paternoster Row, London, who accepted, but at the authors' own risk since they felt the commercial risk to the company was too great. The work thus appeared in 1846, published using the male pseudonyms of Currer (Charlotte), Ellis (Emily) and Acton (Anne) Bell. These were very uncommon forenames but the initials of each of the sisters were preserved and the patronym could have been inspired by that of the vicar of the parish, Arthur Bell Nicholls. It was in fact on 18 May 1845 that he took up his duties at Haworth, at the moment when the publication project was well advanced.

The book attracted hardly any attention. Only three copies were sold, of which one was purchased by Fredrick Enoch, a resident of Cornmarket, Warwick, who in admiration, wrote to the publisher to request an autograph—the only extant single document carrying the three authors' signatures in their pseudonyms, and they continued creating their prose, each one producing a book a year later. Each worked in secret, unceasingly discussing their writing for hours at the dinner table, after which their father would open the door at 9 p.m. with "Don't stay up late, girls!", then rewinding the clock and taking the stairs up to his room.

Fame

1847

Charlotte's ''Jane Eyre

''Jane Eyre'' ( ; originally published as ''Jane Eyre: An Autobiography'') is a novel by the English writer Charlotte Brontë. It was published under her pen name "Currer Bell" on 19 October 1847 by Smith, Elder & Co. of London. The firs ...

'', Emily's ''Wuthering Heights

''Wuthering Heights'' is the only novel by the English author Emily Brontë, initially published in 1847 under her pen name "Ellis Bell". It concerns two families of the landed gentry living on the West Yorkshire moors, the Earnshaws and the ...

'' and Anne's ''Agnes Grey

''Agnes Grey, A Novel'' is the Debut novel, first novel by English author Anne Brontë (writing under the pen name of "Acton Bell"), first published in December 1847, and republished in a second edition in 1850. The novel follows Agnes Grey, a g ...

'' appeared in 1847 after many tribulations, again for reasons of finding a publisher. The packets containing the manuscripts were often returned to the parsonage and Charlotte simply added a new address; she did this at least a dozen times during the year. The first one was finally published by Smith, Elder & Co in London. The 23-year-old owner, George Smith, had specialised in publishing scientific revues, aided by his perspicacious reader William Smith Williams. Emily and Anne's manuscripts were confided to Thomas Cautley Newby, who intended to compile a ''three-decker''; more economical for sale and for loan in the "circulating libraries". The two first volumes included ''Wuthering Heights'' and the third one ''Agnes Grey''. Both novels attracted critical acclaim, occasionally harsh about ''Wuthering Heights'', praised for the originality of the subject and its narrative style, but viewed with suspicion because of its outrageous violence and immorality—surely, the critics wrote, a work of a man with a depraved mind. Critics were fairly neutral about ''Agnes Grey'', but more flattering for ''Jane Eyre'', which soon became a best-seller

A bestseller is a book or other media noted for its top selling status, with bestseller lists published by newspapers, magazines, and book store chains. Some lists are broken down into classifications and specialties (novel, nonfiction book, cookb ...

, despite some commentators denouncing it as an affront to good morals.

''Jane Eyre'' and rising fame

The pseudonymous (Currer Bell) publication in 1847 of ''Jane Eyre, An Autobiography'' established a dazzling reputation for Charlotte. In July 1848, Charlotte and Anne (Emily had refused to go along with them) travelled by train to London to prove to Smith, Elder & Co. that each sister was indeed an independent author, for Thomas Cautley Newby, the publisher of ''Wuthering Heights'' and ''Agnes Grey'', had launched a rumour that the three novels were the work of one author, understood to be Ellis Bell (Emily). George Smith was extremely surprised to find two gawky, ill-dressed country girls paralysed with fear, who, to identify themselves, held out the letters addressed to ''Messrs. Acton, Currer and Ellis Bell''. Taken by such surprise, he introduced them to his mother with all the dignity their talent merited, and invited them to the opera for a performance of Rossini

Gioachino Antonio Rossini (29 February 1792 – 13 November 1868) was an Italian composer of the late Classical and early Romantic eras. He gained fame for his 39 operas, although he also wrote many songs, some chamber music and piano p ...

's '' Barber of Seville''.

''Wuthering Heights''

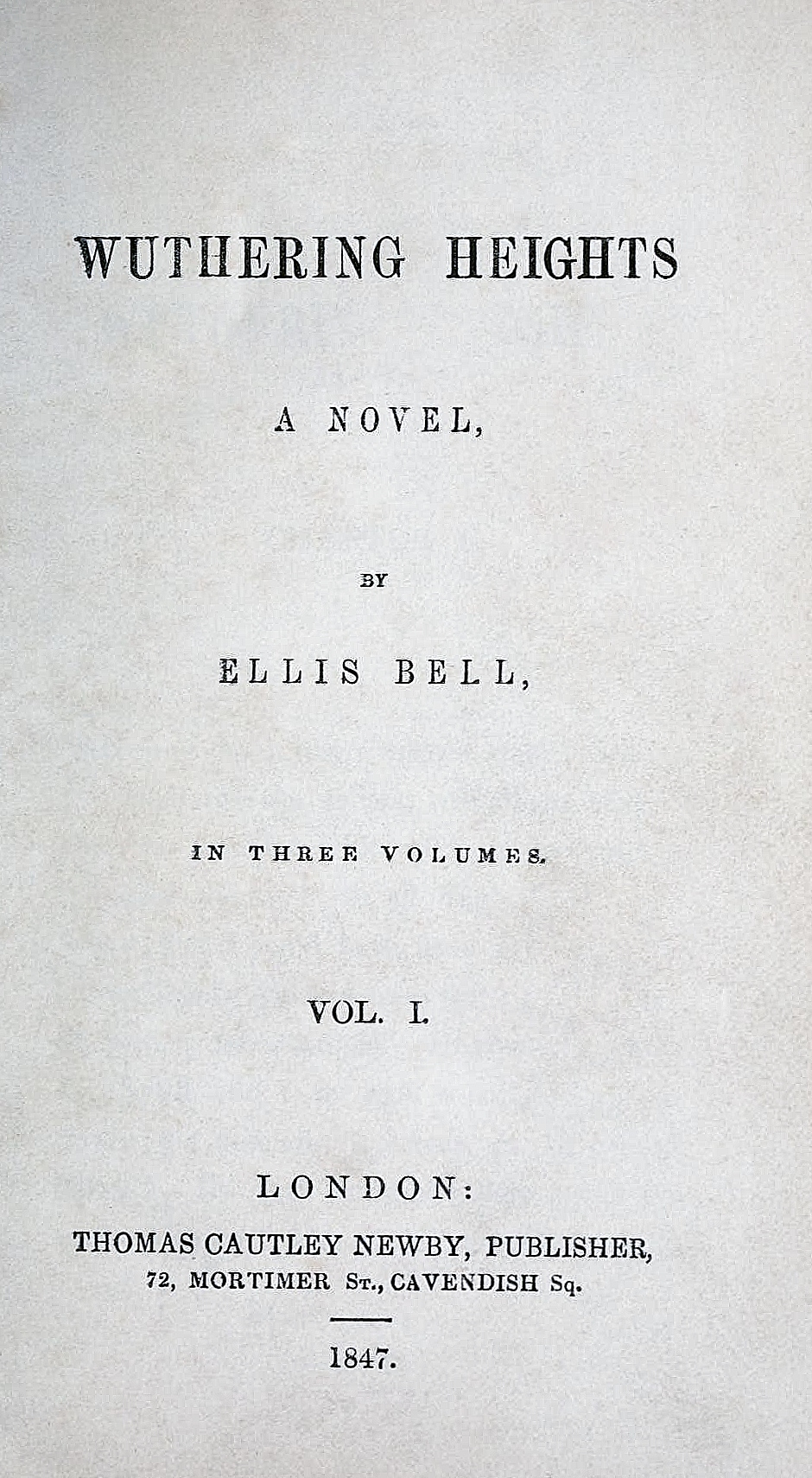

Emily Brontë's ''Wuthering Heights'' was published in 1847 under the masculine pseudonym Ellis Bell, by Thomas Cautley Newby, in two companion volumes to that of Anne's (Acton Bell), ''

Emily Brontë's ''Wuthering Heights'' was published in 1847 under the masculine pseudonym Ellis Bell, by Thomas Cautley Newby, in two companion volumes to that of Anne's (Acton Bell), ''Agnes Grey

''Agnes Grey, A Novel'' is the Debut novel, first novel by English author Anne Brontë (writing under the pen name of "Acton Bell"), first published in December 1847, and republished in a second edition in 1850. The novel follows Agnes Grey, a g ...

.'' Controversial from the start of its release, its originality, its subject, narrative style and troubled action raised intrigue. Certain critics condemned it, but sales were nevertheless considerable for an unknown author of a novel that defied all conventions.

It is a work of black Romanticism, covering three generations isolated in the cold spring of the countryside with two opposing elements: the dignified manor of Thrushcross Grange and the rambling dilapidated pile of Wuthering Heights. The main characters, swept by tumults of the earth, the skies and the hearts, are strange and often possessed of unheard-of violence and deprivations. The story is told in a scholarly fashion, with two narrators, the traveller and tenant Lockwood, and the housekeeper/governess, Nelly Dean, with two sections in the first person, one direct, one cloaked, which overlap each other with digressions and sub-plots that form, from apparently scattered fragments, a coherently locked unit.

1848, Anne's ''The Tenant of Wildfell Hall''

One year before her death in May 1849, Anne published a second novel. Far more ambitious than her previous novel, ''The Tenant of Wildfell Hall'' was a great success and rapidly outsold Emily's ''

One year before her death in May 1849, Anne published a second novel. Far more ambitious than her previous novel, ''The Tenant of Wildfell Hall'' was a great success and rapidly outsold Emily's ''Wuthering Heights

''Wuthering Heights'' is the only novel by the English author Emily Brontë, initially published in 1847 under her pen name "Ellis Bell". It concerns two families of the landed gentry living on the West Yorkshire moors, the Earnshaws and the ...

''. However, the critical reception was mixed—praise for the novel's "power" and "effect" and sharp criticism for being "coarse". Charlotte Brontë

Charlotte Nicholls (; 21 April 1816 – 31 March 1855), commonly known as Charlotte Brontë (, commonly ), was an English novelist and poet, the eldest of the three Brontë family, Brontë sisters who survived into adulthood and whose novel ...

herself, Anne's sister, wrote to her publisher that it "hardly seems to me desirable to choice of subject in that work is a mistake."feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideology, ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social gender equality, equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that modern soci ...

novels.

Identities revealed

In 1850, a little over a year after the deaths of Emily and Anne, Charlotte wrote a preface for the re-print of the combined edition of ''Wuthering Heights'' and ''Agnes Grey'', in which she publicly revealed the real identities of all three sisters.

Charlotte Brontë

Denunciation of boarding schools (''Jane Eyre'')

Conditions at the school at Cowan Bridge, where Maria and Elizabeth may have contracted the tuberculosis from which they died, were probably no worse than those at many other schools of the time. (For example, several decades before the Brontë sisters' experience at Cowan Bridge, Jane Austen

Jane Austen ( ; 16 December 1775 – 18 July 1817) was an English novelist known primarily for #List of works, her six novels, which implicitly interpret, critique, and comment on the English landed gentry at the end of the 18th century ...

and her sister Cassandra contracted typhus at a similar boarding school, and Jane nearly died. The Austen sisters' education, like that of the Brontë sisters, was continued at home.) Nevertheless, Charlotte blamed Cowan Bridge for her sisters' deaths, especially its poor medical care—chiefly, repeated emetics and blood-lettings—and the negligence of the school's doctor, who was the director's brother-in-law. Charlotte's vivid memories of the privations at Cowan Bridge were poured into her depiction of Lowood School in ''Jane Eyre'': the scanty and often spoiled food, the lack of heating and adequate clothing, the periodic epidemics of illness such as "low fever" (probably typhus), the severity and arbitrariness of the punishments, and even the harshness of particular teachers (a Miss Andrews who taught at Cowan Bridge is thought to have been Charlotte's model for Miss Scatcherd in ''Jane Eyre''). Elizabeth Gaskell

Elizabeth Cleghorn Gaskell (''née'' Stevenson; 29 September 1810 – 12 November 1865), often referred to as Mrs Gaskell, was an English novelist, biographer, and short story writer. Her novels offer detailed studies of Victorian era, Victoria ...

, a personal friend and the first biographer of Charlotte, confirmed that Cowan Bridge was Charlotte's model for Lowood and insisted that conditions there in Charlotte's day were egregious. More recent biographers have argued that the food, clothing, heating, medical care and discipline at Cowan Bridge were not considered sub-standard for religious schools of the time, testaments of the era's complacency about these intolerable conditions. One scholar has commended Patrick Brontë for his perspicacity in removing all his daughters from the school, a few weeks before the deaths of Maria and Elizabeth.

Literary encounters

Following the overwhelming success of ''Jane Eyre

''Jane Eyre'' ( ; originally published as ''Jane Eyre: An Autobiography'') is a novel by the English writer Charlotte Brontë. It was published under her pen name "Currer Bell" on 19 October 1847 by Smith, Elder & Co. of London. The firs ...

'', Charlotte was pressured by George Smith, her publisher, to travel to London to meet her public. Despite the extreme timidity that paralysed her among strangers and made her almost incapable of expressing herself, Charlotte consented to be lionised, and in London was introduced to other great writers of the era, including Harriet Martineau

Harriet Martineau (12 June 1802 – 27 June 1876) was an English social theorist.Hill, Michael R. (2002''Harriet Martineau: Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives'' Routledge. She wrote from a sociological, holism, holistic, religious and ...

and William Makepeace Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray ( ; 18 July 1811 – 24 December 1863) was an English novelist and illustrator. He is known for his Satire, satirical works, particularly his 1847–1848 novel ''Vanity Fair (novel), Vanity Fair'', a panoramic portra ...

, both of whom befriended her. Charlotte especially admired Thackeray, whose portrait, given to her by Smith, still hangs in the dining room at Haworth parsonage. On one occasion during a public gathering, Thackeray introduced Charlotte to his mother as ''Jane Eyre'' and when Charlotte called on him the next day, he received an extended dressing-down, in which Smith had to intervene.

During her trip to London in 1851 she visited the

On one occasion during a public gathering, Thackeray introduced Charlotte to his mother as ''Jane Eyre'' and when Charlotte called on him the next day, he received an extended dressing-down, in which Smith had to intervene.

During her trip to London in 1851 she visited the Great Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held), was an international exhibition that took ...

and The Crystal Palace

The Crystal Palace was a cast iron and plate glass structure, originally built in Hyde Park, London, to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. The exhibition took place from 1 May to 15 October 1851, and more than 14,000 exhibitors from around ...

. In 1849 she published '' Shirley'' and in 1853 '' Villette''.

Marriage and death

The Brontë sisters were highly amused by the behaviour of the curates they met. Arthur Bell Nicholls (1818–1906) had been curate of Haworth for seven and a half years, when contrary to all expectations, and to the fury of Patrick Brontë (their father), he proposed to Charlotte. Although impressed by his dignity and deep voice, as well as by his near complete emotional collapse when she rejected him, she found him rigid, conventional and rather narrow-minded "like all the curates"—as she wrote to Ellen Nussey. After she declined his proposal, Nicholls, pursued by the anger of Patrick Brontë, left his functions for several months. However, little by little her feelings evolved and after slowly convincing her father, she finally married Nicholls on 29 June 1854.

On return from their honeymoon in Ireland where she had been introduced to Mr. Nicholls' aunt and cousins, her life completely changed. She adopted her new duties as a wife, which took up most of her time. She wrote to her friends telling them that Nicholls was a good and attentive husband, but that she nevertheless felt a kind of holy terror at her new situation. In a letter to Ellen Nussey (Nell), in 1854 she wrote "Indeed-indeed-Nell-it is a solemn and strange and perilous thing for a woman to become a wife."

The following year she died aged 38. The cause of death given at the time was tuberculosis, but it may have been complicated with typhoid fever (the water at Haworth being likely contaminated due to poor sanitation and the vast cemetery that surrounded the church and the parsonage) and

The Brontë sisters were highly amused by the behaviour of the curates they met. Arthur Bell Nicholls (1818–1906) had been curate of Haworth for seven and a half years, when contrary to all expectations, and to the fury of Patrick Brontë (their father), he proposed to Charlotte. Although impressed by his dignity and deep voice, as well as by his near complete emotional collapse when she rejected him, she found him rigid, conventional and rather narrow-minded "like all the curates"—as she wrote to Ellen Nussey. After she declined his proposal, Nicholls, pursued by the anger of Patrick Brontë, left his functions for several months. However, little by little her feelings evolved and after slowly convincing her father, she finally married Nicholls on 29 June 1854.

On return from their honeymoon in Ireland where she had been introduced to Mr. Nicholls' aunt and cousins, her life completely changed. She adopted her new duties as a wife, which took up most of her time. She wrote to her friends telling them that Nicholls was a good and attentive husband, but that she nevertheless felt a kind of holy terror at her new situation. In a letter to Ellen Nussey (Nell), in 1854 she wrote "Indeed-indeed-Nell-it is a solemn and strange and perilous thing for a woman to become a wife."

The following year she died aged 38. The cause of death given at the time was tuberculosis, but it may have been complicated with typhoid fever (the water at Haworth being likely contaminated due to poor sanitation and the vast cemetery that surrounded the church and the parsonage) and hyperemesis gravidarum

Hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) is a pregnancy complication that is characterized by severe nausea, vomiting, weight loss, and possibly dehydration. Feeling faint may also occur. It is considered a more severe form of morning sickness. Symptoms ...

from her pregnancy that was in its early stage.

The first biography of Charlotte was written by Elizabeth Cleghorn Gaskell at the request of Patrick Brontë, and published in 1857, helping to create the myth of a family of condemned genius, living in a painful and romantic solitude. After having stayed at Haworth several times and having accommodated Charlotte in Plymouth Grove, Manchester, and having become her friend and confidant, Mrs Gaskell certainly had the advantage of knowing the family.

Novels

* ''Jane Eyre

''Jane Eyre'' ( ; originally published as ''Jane Eyre: An Autobiography'') is a novel by the English writer Charlotte Brontë. It was published under her pen name "Currer Bell" on 19 October 1847 by Smith, Elder & Co. of London. The firs ...

'' (1847)

* '' Shirley'' (1849)

* '' Villette'' (1853)

* '' The Professor'' (1857)

Unfinished fragments

These are outlines or unedited roughcasts which with the exception of ''Emma'' have been recently published.

* ''Ashford'', written between 1840 and 1841, where certain characters from Angria are transported to Yorkshire and are included in a realistic plot.

* ''Willie Ellin'', started after '' Shirley'' and '' Villette'', and on which Charlotte worked relatively little in May and July 1853, is a story in three poorly linked parts in which the plot at this stage remains rather vague.

* ''The Moores'' is an outline for two short chapters with two characters, the brothers Robert Moore, a dominator, and John Henry Moore, an intellectual fanatic.

* ''Emma'', already published in 1860 with an introduction from Thackeray. This brilliant fragment would doubtlessly have become a novel of similar scope to her previous ones. It later inspired the novel '' A Little Princess'' by Frances Hodgson Burnett

Frances Eliza Hodgson Burnett (24 November 1849 – 29 October 1924) was a British-American novelist and playwright. She is best known for the three children's novels ''Little Lord Fauntleroy'' (1886), ''A Little Princess'' (1905), a ...

.

* ''The Green Dwarf'' published in 2003. This story was probably inspired by '' The Black Dwarf'' by Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European literature, European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'' (18 ...

of whose novels Charlotte was a fan. The novel is a fictional history about a war that breaks out between Verdopolis (the capital of the confederation of '' Glass Town'') and Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to Mauritania–Senegal border, the north, Mali to Mali–Senegal border, the east, Guinea t ...

.

Branwell Brontë

Patrick Branwell Brontë (1817–1848) was considered by his father and sisters to be a genius, while the book by

Patrick Branwell Brontë (1817–1848) was considered by his father and sisters to be a genius, while the book by Daphne du Maurier

Dame Daphne du Maurier, Lady Browning, (; 13 May 1907 – 19 April 1989) was an English novelist, biographer and playwright. Her parents were actor-manager Gerald du Maurier, Sir Gerald du Maurier and his wife, actress Muriel Beaumont. Her gra ...

(1986), ''The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë'', contains numerous references to his addiction to alcohol and laudanum

Laudanum is a tincture of opium containing approximately 10% powdered opium by weight (the equivalent of 1% morphine). Laudanum is prepared by dissolving extracts from the opium poppy (''Papaver somniferum'') in alcohol (ethanol).

Reddish-br ...

. He was an intelligent boy with many talents and interested in many subjects, especially literature. He was often the driving force in the Brontë siblings' construction of the imaginary worlds. He was artistic and was encouraged by his father to pursue this.