Boston Vigilance Committee on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Boston Vigilance Committee (1841–1861) was an

The Boston Vigilance Committee (1841–1861) was an

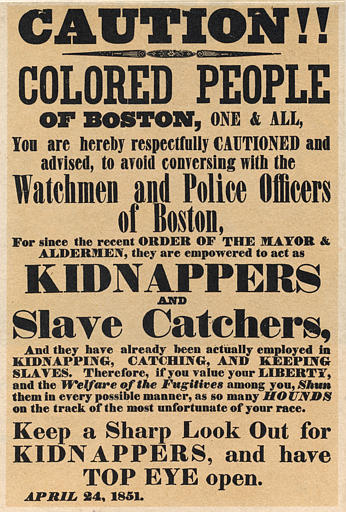

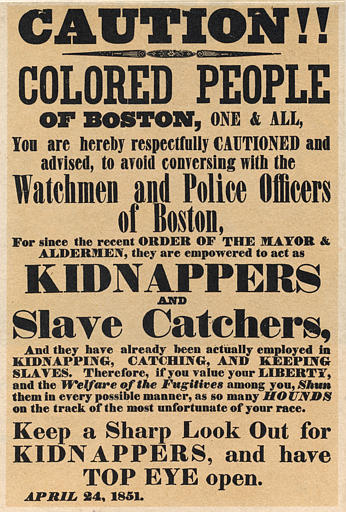

In 1850, Shadrach Minkins escaped from slavery in Virginia and made his way to Boston, where he found work as a waiter. One morning in February 1851 he was serving breakfast when he was arrested by federal marshals and taken away to the federal courthouse in Boston. The Boston Vigilance Committee hired a team of lawyers to defend Minkins, including Richard Henry Dana Jr., Ellis Gray Loring, Robert Morris, and Samuel E. Sewall. Members posted handbills warning abolitionists that slave catchers had been seen in Boston. Protesters thronged in front of the courthouse, calling for Minkins' release.Snodgrass (2015), pp. 366–67

On February 15, 1851, a group of about 20 black activists led by Lewis Hayden stormed the courthouse and released Minkins by force. Among them were John J. Smith, a Boston barber who would later become a Massachusetts state representative, and John P. Coburn, along with several of his men. Coburn was captain of the Massasoit Guards, a black militia company that was a precursor to the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. Minkins was carried off in a wagon to Beacon Hill, where he hid in an attic until nightfall, and was smuggled out of town. With the help of the Underground Railroad, he eventually made it to Canada.Snodgrass (2015), pp. 366–67

At least three committee members were arrested for taking part in the rescue: Lewis Hayden, Robert Morris, and Elizur Wright. The Committee hired lawyers to defend them (and others), and all were acquitted.Siebert (1952), p. 31; Collison (2009), pp. 142, 195. Wright, the only white man arrested, had not voluntarily taken part in the rescue, but had been standing in the courtroom when it happened and was swept along by the crowd.Collison (2009), p. 126.

In 1850, Shadrach Minkins escaped from slavery in Virginia and made his way to Boston, where he found work as a waiter. One morning in February 1851 he was serving breakfast when he was arrested by federal marshals and taken away to the federal courthouse in Boston. The Boston Vigilance Committee hired a team of lawyers to defend Minkins, including Richard Henry Dana Jr., Ellis Gray Loring, Robert Morris, and Samuel E. Sewall. Members posted handbills warning abolitionists that slave catchers had been seen in Boston. Protesters thronged in front of the courthouse, calling for Minkins' release.Snodgrass (2015), pp. 366–67

On February 15, 1851, a group of about 20 black activists led by Lewis Hayden stormed the courthouse and released Minkins by force. Among them were John J. Smith, a Boston barber who would later become a Massachusetts state representative, and John P. Coburn, along with several of his men. Coburn was captain of the Massasoit Guards, a black militia company that was a precursor to the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. Minkins was carried off in a wagon to Beacon Hill, where he hid in an attic until nightfall, and was smuggled out of town. With the help of the Underground Railroad, he eventually made it to Canada.Snodgrass (2015), pp. 366–67

At least three committee members were arrested for taking part in the rescue: Lewis Hayden, Robert Morris, and Elizur Wright. The Committee hired lawyers to defend them (and others), and all were acquitted.Siebert (1952), p. 31; Collison (2009), pp. 142, 195. Wright, the only white man arrested, had not voluntarily taken part in the rescue, but had been standing in the courtroom when it happened and was swept along by the crowd.Collison (2009), p. 126.

In 1853, Anthony Burns escaped slavery in Virginia and settled in Boston, where he found work in a clothing shop. In May of the following year, he was arrested and imprisoned in a room on an upper floor of the court house. Attorney John A. Albion led a team of Vigilance Committee lawyers in an unsuccessful defense. Wendell Phillips and Theodore Parker offered $1,300 for Burns's freedom, but were turned down.Snodgrass (2015), p. 89.

That night, a mob led by Reverend Higginson attacked the courthouse with axes and beams. They broke down the southwest door of the courthouse and started up the stairs, but were confronted by armed guards. During the melee, marshal James Batchelder was shot and killed. Higginson came to believe his friend Martin Stowell was responsible, but fellow committee member William Francis Channing determined Batchelder was in fact killed by Lewis Hayden.Siebert (1952), pp. 38–39; Snodgrass (2015), p. 89. When two regiments of troops from Fort Warren and the

In 1853, Anthony Burns escaped slavery in Virginia and settled in Boston, where he found work in a clothing shop. In May of the following year, he was arrested and imprisoned in a room on an upper floor of the court house. Attorney John A. Albion led a team of Vigilance Committee lawyers in an unsuccessful defense. Wendell Phillips and Theodore Parker offered $1,300 for Burns's freedom, but were turned down.Snodgrass (2015), p. 89.

That night, a mob led by Reverend Higginson attacked the courthouse with axes and beams. They broke down the southwest door of the courthouse and started up the stairs, but were confronted by armed guards. During the melee, marshal James Batchelder was shot and killed. Higginson came to believe his friend Martin Stowell was responsible, but fellow committee member William Francis Channing determined Batchelder was in fact killed by Lewis Hayden.Siebert (1952), pp. 38–39; Snodgrass (2015), p. 89. When two regiments of troops from Fort Warren and the

The Boston Vigilance Committee (1841–1861) was an

The Boston Vigilance Committee (1841–1861) was an abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

organization formed in Boston, Massachusetts

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

, to protect escaped slaves from being kidnapped and returned to slavery in the South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

. The Committee aided hundreds of escapees, most of whom arrived as stowaways on coastal trading vessel

Coastal trading vessels, also known as coasters or skoots, are shallow-hulled merchant ships used for transporting cargo along a coastline. Their shallow hulls mean that they can get through reefs where deeper-hulled seagoing ships usually cannot ...

s and stayed a short time before moving on to Canada or England. Notably, members of the Committee provided legal and other aid to George Latimer, Ellen and William Craft

Ellen Craft (1826–1891) and William Craft (September 25, 1824 – January 29, 1900) were American abolitionists who were born into slavery in Macon, Georgia. They escaped to the Northern United States in December 1848 by traveling by train and ...

, Shadrach Minkins, Thomas Sims, and Anthony Burns

Anthony Burns (May 31, 1834 – July 17, 1862) was an African-American man who escaped from slavery in Virginia in 1854. His capture and trial in Boston, and transport back to Virginia, generated wide-scale public outrage in the North and incre ...

.

Members coordinated with donors and Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was an organized network of secret routes and safe houses used by freedom seekers to escape to the abolitionist Northern United States and Eastern Canada. Enslaved Africans and African Americans escaped from slavery ...

conductors to provide escapees with funds, shelter, medical attention, legal counsel, transportation, and sometimes weapons. They kept an eye out for slave catchers, and spread the word when any came to town. Some members took part in violent rescue efforts.

History

Founding (1841)

The Boston Vigilance Committee was formed on June 4, 1841, in response to a public call issued by Charles Turner Torrey and several other signers. The founding meeting was held in the Marlboro Chapel on Washington Street, nearBoston Common

The Boston Common is a public park in downtown Boston, Massachusetts. It is the oldest city park in the United States. Boston Common consists of of land bounded by five major Boston streets: Tremont Street, Park Street, Beacon Street, Charl ...

. According to William Cooper Nell

William Cooper Nell (December 16, 1816 – May 25, 1874) was an American abolitionist, journalist, publisher, author, and civil servant of Boston, Massachusetts, who worked for the integration of schools and public facilities in the state. Wri ...

, those present at the first meeting represented "various classes of our citizens, white and colored, (the latter of whom were quite numerous,) persons of different religious persuasions," members of other anti-slavery organizations, and "friends of the oppressed colored man" who were not yet affiliated with any such groups.Nell (2002), p. 99. The original officers were Francis Jackson, Chairman; Charles T. Torrey, Secretary; and Joseph Southwick, Treasurer. The original Executive Committee was composed of Daniel Mann, Benjamin Weeden, Curtis C. Nichols, Thomas Jinnings Jr., William Cooper Nell, J. P. Bishop, John Rogers, and S. R. Alexander.Nell (2002), p. 100.

A constitution was adopted that same evening, the first article of which stated the group's purpose:

The object of this Association shall be to secure to persons of color the enjoyment of their constitutional and legal rights. To secure this object, it will employ every legal, peaceful, and Christian method, and none other.By the end of 1841, Torrey had tired of the slow pace of political abolitionism and moved to Washington, D.C.; within a few years he would be dead in prison, having helped free hundreds of slaves in the Washington area. In 1842, the Supreme Court ruled in '' Prigg v. Pennsylvania'' that the federal

Fugitive Slave Act

A fugitive or runaway is a person who is fleeing from custody, whether it be from jail, a government arrest, government or non-government questioning, vigilante violence, or outraged private individuals. A fugitive from justice, also known ...

nullified any free-state laws protecting fugitive slaves. This would have made it harder for the Boston Vigilance Committee to be effective without breaking the law. Soon afterwards, several black Bostonians formed the New England Freedom Association, which did not commit itself to operating strictly within the law. Both groups held strategy meetings in the African Meeting House on Beacon Hill. The New England Freedom Association eventually merged with the Boston Vigilance Committee.

In the fall of 1842, attorney Samuel E. Sewall

Samuel is a figure who, in the narratives of the Hebrew Bible, plays a key role in the transition from the biblical judges to the United Kingdom of Israel under Saul, and again in the monarchy's transition from Saul to David. He is venerate ...

defended George Latimer, who had escaped slavery in Virginia and was arrested in Boston.Snodgrass (2015), p. 478. When Sewall lost the case, he and others purchased Latimer's freedom.Tiffany (1898), p. 70.

Four years later, abolitionists learned that a fugitive slave was being held on a ship in Boston Harbor, but were unable to rescue him. According to one historian, this event triggered the formation of the Boston Vigilance Committee.Collison (2009), p. 87. It is not clear whether the committee that formed in 1846 was entirely new or a revival of the existing committee. Records show 19 fugitives from the South applying to the committee for financial and legal aid from 1846 to 1847. It may have disbanded in 1847 when no new attempts were made to arrest fugitive slaves in Boston.

Reorganization (1850)

On September 18, 1850, Congress passed theFugitive Slave Act of 1850

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was a law passed by the 31st United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern interests in slavery and Northern Free-Soilers.

The Act was one ...

, requiring free states to assist with the capture and return of fugitive slaves. On October 4, the Boston Vigilance Committee called a public meeting in Faneuil Hall

Faneuil Hall ( or ; previously ) is a marketplace and meeting hall near the waterfront and Government Center, Boston, Massachusetts, Government Center, in Boston, Massachusetts, United States. Opened in 1742, it was the site of several speeches ...

to discuss how to respond. Noted abolitionists Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 14, 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He was the most impor ...

and Theodore Parker addressed the crowd, which was one of the largest ever convened in the hall. This meeting is often referred to as the first or founding meeting. Presumably, many new members were unaware of the original committee's existence.Siebert (1952), p. 25.

The new officers were Timothy Gilbert, President; Charles List, Secretary; and Francis Jackson, Treasurer. The Executive Committee was composed of Theodore Parker, Joshua Bowen Smith, Lewis Hayden

Lewis Hayden (December 2, 1811 – April 7, 1889) escaped slavery in Kentucky with his family and reached Canada. He established a school for African Americans before moving to Boston, Massachusetts. There he became an Abolitionism in the United ...

, Samuel G. Howe, Wendell Phillips

Wendell Phillips (November 29, 1811 – February 2, 1884) was an American abolitionist, labor reformer, temperance activist, advocate for Native Americans, orator, and attorney.

According to George Lewis Ruffin, a black attorney, Phillip ...

, Edmund Jackson, Charles M. Ellis, and Charles K. Whipple. On the Finance Committee were Robert E. Apthorp, Henry I. Bowditch, William W. Marjoram, Samuel E. Sewall

Samuel is a figure who, in the narratives of the Hebrew Bible, plays a key role in the transition from the biblical judges to the United Kingdom of Israel under Saul, and again in the monarchy's transition from Saul to David. He is venerate ...

, John A. Andrew, Ellis Gray Loring, Robert Morris, and former chairman Francis Jackson.Bearse (1880), p. 6.

The Committee was racially integrated and had over 200 members.Jacobs (1993), p. 93. Many were wealthy elites whose main contribution was funding. Those who provided more hands-on assistance included, among others, Lewis Hayden

Lewis Hayden (December 2, 1811 – April 7, 1889) escaped slavery in Kentucky with his family and reached Canada. He established a school for African Americans before moving to Boston, Massachusetts. There he became an Abolitionism in the United ...

, who helped rescue Shadrach Minkins from federal custody in 1851;Snodgrass (2015), p. 256. John Swett Rock, the committee's medical officer;Snodgrass (2015), p. 235. and Austin Bearse

Austin Bearse (1808-1881) was a sea captain from Cape Cod who provided transportation for fugitive slaves in the years leading up to the American Civil War.

Early life

Bearse was born in Barnstable, Massachusetts, on April 3, 1808, the son of E ...

, a ship captain who smuggled fugitives in and out of Boston. Several members, such as Richard Henry Dana Jr.

Richard Henry Dana Jr. (August 1, 1815 – January 6, 1882) was an American lawyer and politician from Massachusetts, a descendant of a colonial family, who gained renown as the author of the classic American memoir ''Two Years Before the Mast'' a ...

and Samuel Edmund Sewall, were lawyers who defended fugitive slaves and their allies in court. At least three were also members of the Secret Six, who funded John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia, United States. The population was 269 at the 2020 United States census. Situated at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers in the lower Shenandoah Valley, where ...

: preachers Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Thomas Wentworth Higginson (December 22, 1823May 9, 1911), who went by the name Wentworth, was an American Unitarianism, Unitarian minister, author, Abolitionism, abolitionist, politician, and soldier. He was active in abolitionism in the United ...

and Theodore Parker, and physician Samuel Gridley Howe

Samuel Gridley Howe (November 10, 1801 – January 9, 1876) was an American physician, abolitionist, and advocate of education for the blind. He organized and was the first director of the Perkins Institution. In 1824, he had gone to Greece to ...

. Rev. Joshua Young

Joshua Young (September 23, 1823 – February 7, 1904) was an abolitionist Congregational Unitarian minister who crossed paths with many famous people of the mid-19th century. He received national publicity and lost his pulpit for presiding in 1 ...

, who later would be reviled for presiding at the funeral for John Brown, was a member. Apparently the Committee had no women members; the New England Freedom Association, by contrast, had two women officers.Nell (2002), p. 18.

Many locals who were not members provided aid to escapees and were reimbursed by the Committee. For example, the Committee's expense ledger shows several payments to the Reverend Leonard Grimes of the Twelfth Baptist Church

The Twelfth Baptist Church is a historic church in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts. Established in 1840, it is the oldest direct descendant of the First Independent Baptist Church in Beacon Hill. Notable members have included ab ...

for passage fees, and one payment of $9 to George Latimer for "six days watching Jn. Caphart." John Caphart was a notorious slave catcher.Stowe (1853), pp. 6–7.

Although the committee was interracial, it never had more than eight black members. With a few exceptions, the white members tended to be more cautious than the black members, preferring to supply legal and financial aid while black Bostonians did most of the actual relief work behind the scenes. Higginson later complained in his memoir that "half of them were non-resistants," prone to indecision and inertia. Black Bostonians had more at stake, and were more willing to use force to achieve their ends.

Vigilance committee

A vigilance committee is a group of private citizens who take it upon themselves to administer law and order or exercise power in places where they consider the governmental structures or actions inadequate. Prominent historical examples of vigi ...

s such as Boston's were not uncommon in the years leading up to the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. Boston's was unusual in that its treasurer kept detailed records for the years 1850 to 1861. For example, one entry for December 26, 1850, reads, "Isabella S. Holmes, boarding Geo. Newton, Fugitive, $3.43." This was extremely risky given that such activities were illegal at the time, and punishable by jail time and stiff fines.Siebert (1952), p. 24.

Ellen and William Craft

In 1848, William and Ellen Craft escaped slavery in Georgia and made their way to theNorth

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

. Their daring escape was widely publicized by abolitionists, which made them more vulnerable to slave catchers. In 1850 they were living in Boston, where Ellen worked as a seamstress and William as a carpenter. After the Fugitive Slave Act passed in September, federal warrants were issued for them. Soon afterwards, two slave catchers from Georgia were spotted in Boston. William sent his wife to hide at the home of William I. Bowditch in Brookline, while he stayed with Lewis Hayden in Beacon Hill.Siebert (1952), pp. 26–28.

Other members of the committee, meanwhile, set to work harassing the two slave catchers, Willis Hughes and John Knight.Collison (2009), p. 91. They posted hundreds of handbills all over the city, describing the appearance of the two men. The lawyers had Hughes and Knight arrested again and again on various charges: slander (for claiming that William Craft had stolen the clothing in which he escaped), carrying concealed weapons, smoking in the street, swearing in public, and attempted kidnapping. Each time they were bailed out by pro-slavery sympathizers. On one occasion, as they emerged from the courtroom, they were mobbed by a crowd of black abolitionists, and fled in a carriage; they were then arrested for speeding, and for "running the toll when chased over Cambridge bridge."Collison (2009), p. 96.

The Crafts remained in hiding in Boston for several weeks, staying at various locations before fleeing to England in January. On November 7, 1850, they were married by Theodore Parker.Siebert (1952), p. 27.

Shadrach Minkins

In 1850, Shadrach Minkins escaped from slavery in Virginia and made his way to Boston, where he found work as a waiter. One morning in February 1851 he was serving breakfast when he was arrested by federal marshals and taken away to the federal courthouse in Boston. The Boston Vigilance Committee hired a team of lawyers to defend Minkins, including Richard Henry Dana Jr., Ellis Gray Loring, Robert Morris, and Samuel E. Sewall. Members posted handbills warning abolitionists that slave catchers had been seen in Boston. Protesters thronged in front of the courthouse, calling for Minkins' release.Snodgrass (2015), pp. 366–67

On February 15, 1851, a group of about 20 black activists led by Lewis Hayden stormed the courthouse and released Minkins by force. Among them were John J. Smith, a Boston barber who would later become a Massachusetts state representative, and John P. Coburn, along with several of his men. Coburn was captain of the Massasoit Guards, a black militia company that was a precursor to the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. Minkins was carried off in a wagon to Beacon Hill, where he hid in an attic until nightfall, and was smuggled out of town. With the help of the Underground Railroad, he eventually made it to Canada.Snodgrass (2015), pp. 366–67

At least three committee members were arrested for taking part in the rescue: Lewis Hayden, Robert Morris, and Elizur Wright. The Committee hired lawyers to defend them (and others), and all were acquitted.Siebert (1952), p. 31; Collison (2009), pp. 142, 195. Wright, the only white man arrested, had not voluntarily taken part in the rescue, but had been standing in the courtroom when it happened and was swept along by the crowd.Collison (2009), p. 126.

In 1850, Shadrach Minkins escaped from slavery in Virginia and made his way to Boston, where he found work as a waiter. One morning in February 1851 he was serving breakfast when he was arrested by federal marshals and taken away to the federal courthouse in Boston. The Boston Vigilance Committee hired a team of lawyers to defend Minkins, including Richard Henry Dana Jr., Ellis Gray Loring, Robert Morris, and Samuel E. Sewall. Members posted handbills warning abolitionists that slave catchers had been seen in Boston. Protesters thronged in front of the courthouse, calling for Minkins' release.Snodgrass (2015), pp. 366–67

On February 15, 1851, a group of about 20 black activists led by Lewis Hayden stormed the courthouse and released Minkins by force. Among them were John J. Smith, a Boston barber who would later become a Massachusetts state representative, and John P. Coburn, along with several of his men. Coburn was captain of the Massasoit Guards, a black militia company that was a precursor to the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. Minkins was carried off in a wagon to Beacon Hill, where he hid in an attic until nightfall, and was smuggled out of town. With the help of the Underground Railroad, he eventually made it to Canada.Snodgrass (2015), pp. 366–67

At least three committee members were arrested for taking part in the rescue: Lewis Hayden, Robert Morris, and Elizur Wright. The Committee hired lawyers to defend them (and others), and all were acquitted.Siebert (1952), p. 31; Collison (2009), pp. 142, 195. Wright, the only white man arrested, had not voluntarily taken part in the rescue, but had been standing in the courtroom when it happened and was swept along by the crowd.Collison (2009), p. 126.

Thomas Sims

Thomas Sims had escaped slavery in Georgia and was living in Boston when he was seized by federal marshals in 1851. The Committee hired attorney John Albion Andrew to advise him.Snodgrass (2015), p. 485. Sims was locked in a room on the third floor of the federal courthouse. Committee members Lewis Hayden, Reverend Thomas Wentworth Higginson, and John Murray Spear, along with the Reverend Leonard A. Grimes, planned to place mattresses under Sims's cell window so he could jump out and make his getaway in a horse and chaise, but the sheriff barred the window before they could act.Siebert (1952), p. 32. The federal government sent U.S. Marines to march Sims down the streets of Boston, to be taken away on a warship and transferred back to Georgia. Sims was sold to a new slaveholder in Mississippi, but escaped in 1863 and returned to Boston.Anthony Burns

In 1853, Anthony Burns escaped slavery in Virginia and settled in Boston, where he found work in a clothing shop. In May of the following year, he was arrested and imprisoned in a room on an upper floor of the court house. Attorney John A. Albion led a team of Vigilance Committee lawyers in an unsuccessful defense. Wendell Phillips and Theodore Parker offered $1,300 for Burns's freedom, but were turned down.Snodgrass (2015), p. 89.

That night, a mob led by Reverend Higginson attacked the courthouse with axes and beams. They broke down the southwest door of the courthouse and started up the stairs, but were confronted by armed guards. During the melee, marshal James Batchelder was shot and killed. Higginson came to believe his friend Martin Stowell was responsible, but fellow committee member William Francis Channing determined Batchelder was in fact killed by Lewis Hayden.Siebert (1952), pp. 38–39; Snodgrass (2015), p. 89. When two regiments of troops from Fort Warren and the

In 1853, Anthony Burns escaped slavery in Virginia and settled in Boston, where he found work in a clothing shop. In May of the following year, he was arrested and imprisoned in a room on an upper floor of the court house. Attorney John A. Albion led a team of Vigilance Committee lawyers in an unsuccessful defense. Wendell Phillips and Theodore Parker offered $1,300 for Burns's freedom, but were turned down.Snodgrass (2015), p. 89.

That night, a mob led by Reverend Higginson attacked the courthouse with axes and beams. They broke down the southwest door of the courthouse and started up the stairs, but were confronted by armed guards. During the melee, marshal James Batchelder was shot and killed. Higginson came to believe his friend Martin Stowell was responsible, but fellow committee member William Francis Channing determined Batchelder was in fact killed by Lewis Hayden.Siebert (1952), pp. 38–39; Snodgrass (2015), p. 89. When two regiments of troops from Fort Warren and the Charlestown Navy Yard

The Boston Navy Yard, originally called the Charlestown Navy Yard and later Boston Naval Shipyard, was one of the oldest shipbuilding facilities in the United States Navy. It was established in 1801 as part of the recent establishment of t ...

arrived on the scene, the mob scattered, leaving Burns still trapped upstairs.

When the time came for Burns to be transported back to Virginia, Bostonians protested in the streets. The Vigilance Committee paid for "alarm banners" and "alarm bells" to be used in the demonstration, and distributed hundreds of abolitionist pamphlets and placards. They also circulated a petition for the removal of Judge Edward G. Loring (not to be confused with Ellis Gray Loring), who had ordered Burns's return to slavery. Loring was eventually removed from office by Governor Nathaniel Prentice Banks.

Weeks later, Higginson, Phillips, and Parker were charged with inciting a riot by making abolitionist speeches. The Committee hired lawyers to defend them and got the indictment quashed. Reverend Grimes and other abolitionists raised funds to purchase Burns's freedom, and he returned to Massachusetts.

Disbandment

According to Wilbur H. Siebert, the Boston Vigilance Committee ceased to exist ten years and seven months after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, which would mean it disbanded in April 1861.Siebert (1952), p. 23.Notable members

A more complete list can be found in Austin Bearse's 1880 memoir, ''Reminiscences of Fugitive-Slave Law Days in Boston. *Amos Bronson Alcott

Amos Bronson Alcott (; November 29, 1799 – March 4, 1888) was an American teacher, writer, philosopher, and reformer. As an educator, Alcott pioneered new ways of interacting with young students, focusing on a conversational style, and av ...

Bearse (1880), p. 3.

* John A. Andrew

* Edward Atkinson

* John Augustus

John Augustus (c. 1785 – June 21, 1859) was an American boot maker and penal reformer. He is credited with coining the English term "probation" and is called the "Father of Probation" in the United States because of his pioneering efforts to c ...

* Austin Bearse

Austin Bearse (1808-1881) was a sea captain from Cape Cod who provided transportation for fugitive slaves in the years leading up to the American Civil War.

Early life

Bearse was born in Barnstable, Massachusetts, on April 3, 1808, the son of E ...

Snodgrass (2015), p. 44.

* John A. Bolles

* John Botume Jr.

* Henry Ingersoll BowditchSnodgrass (2015), p. 68.

* William Ingersoll Bowditch

* Anson Burlingame

Anson Burlingame (November 14, 1820 – February 23, 1870) was an American lawyer, Republican/American Party legislator, diplomat, and abolitionist. As diplomat, he served as the U.S. minister to China (1862–1867) and then as China's envoy to ...

* Thomas Carew

Thomas Carew (pronounced as "Carey") (1595 – 22 March 1640) was an English poet, among the 'Cavalier' group of Caroline poets.

Biography

He was the son of Sir Matthew Carew, master in chancery, and his wife Alice, daughter of Sir John Rive ...

* William Henry Channing

William Henry Channing (May 25, 1810 – December 23, 1884) was an American Unitarian clergyman, writer and philosopher.

Early life

William Henry Channing was born in Boston, Massachusetts. Channing's father, Francis Dana Channing, died when he w ...

* John P. CoburnSnodgrass (2015), p. 123.

* Nathaniel Colver

* Richard Henry Dana Jr.

Richard Henry Dana Jr. (August 1, 1815 – January 6, 1882) was an American lawyer and politician from Massachusetts, a descendant of a colonial family, who gained renown as the author of the classic American memoir ''Two Years Before the Mast'' a ...

* William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was an Abolitionism in the United States, American abolitionist, journalist, and reformism (historical), social reformer. He is best known for his widely read anti-slavery newspaper ''The ...

* Timothy Gilbert

* Daniel W. Gooch

* Lewis Hayden

Lewis Hayden (December 2, 1811 – April 7, 1889) escaped slavery in Kentucky with his family and reached Canada. He established a school for African Americans before moving to Boston, Massachusetts. There he became an Abolitionism in the United ...

* Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Thomas Wentworth Higginson (December 22, 1823May 9, 1911), who went by the name Wentworth, was an American Unitarianism, Unitarian minister, author, Abolitionism, abolitionist, politician, and soldier. He was active in abolitionism in the United ...

Siebert (1952), p. 39.

* Richard Hildreth

Richard Hildreth (June 28, 1807 – July 11, 1865), was an American journalist, author and historian. He is best known for writing his six-volume ''History of the United States of America'' covering 1497–1821 and published 1840-1853. Historian ...

* John T. Hilton

* Charles F. Hovey

* Samuel Gridley Howe

Samuel Gridley Howe (November 10, 1801 – January 9, 1876) was an American physician, abolitionist, and advocate of education for the blind. He organized and was the first director of the Perkins Institution. In 1824, he had gone to Greece to ...

Snodgrass (2015), p. 928.

* Timothy W. HoxieBearse (1880), p. 4.

* Francis JacksonSnodgrass (2015), p. 959.

* William JacksonCalarco (2011), p. 38.

* John P. Jewett

* Joel W. Lewis

* Ellis Gray LoringSnodgrass (2015), p. 485.

* James Russell Lowell

James Russell Lowell (; February 22, 1819 – August 12, 1891) was an American Romantic poet, critic, editor, and diplomat. He is associated with the fireside poets, a group of New England writers who were among the first American poets to r ...

* Bela Marsh

* Samuel May, Jr.

* Robert Morris

* William Cooper Nell

William Cooper Nell (December 16, 1816 – May 25, 1874) was an American abolitionist, journalist, publisher, author, and civil servant of Boston, Massachusetts, who worked for the integration of schools and public facilities in the state. Wri ...

* Theodore ParkerSnodgrass (2015), p. 1305.

* Wendell Phillips

Wendell Phillips (November 29, 1811 – February 2, 1884) was an American abolitionist, labor reformer, temperance activist, advocate for Native Americans, orator, and attorney.

According to George Lewis Ruffin, a black attorney, Phillip ...

* Henry Prentiss

* Edmund Quincy

* John Swett RockSnodgrass (2015), p. 863.

* Samuel E. Sewall

Samuel is a figure who, in the narratives of the Hebrew Bible, plays a key role in the transition from the biblical judges to the United Kingdom of Israel under Saul, and again in the monarchy's transition from Saul to David. He is venerate ...

* Joshua Bowen SmithSnodgrass (2015), p. 499.

* Isaac H. Snowden

* John Murray Spear

* Lysander Spooner

Lysander Spooner (January 19, 1808 – May 14, 1887) was an American abolitionist, entrepreneur, lawyer, essayist, natural rights legal theorist, pamphleteer, political philosopher, and writer often associated with the Boston anarchist tr ...

Bearse (1880), p. 5.

* Charles Turner Torrey

* Mark Trafton

* Elizur Wright

See also

*Slavery in Massachusetts

"Slavery in Massachusetts" is an 1854 essay by Henry David Thoreau based on a speech he gave at an anti-slavery rally at Framingham, Massachusetts, on July 4, 1854, after the re-enslavement in Boston, Massachusetts of fugitive slave Anthony Burns ...

* Origins of the American Civil War

The origins of the American Civil War were rooted in the desire of the Southern United States, Southern states to preserve and expand the Slavery in the United States, institution of slavery. Historians in the 21st century overwhelmingly agree ...

* History of African Americans in Boston

* Abolition Riot of 1836

Notes

References

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * {{Underground Railroad Organizations based in Boston History of Boston 19th century in Boston American abolitionist organizations African-American history in Boston Pro-fugitive slave riots and civil disorder in the United States