Bogdanov, Aleksandr on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

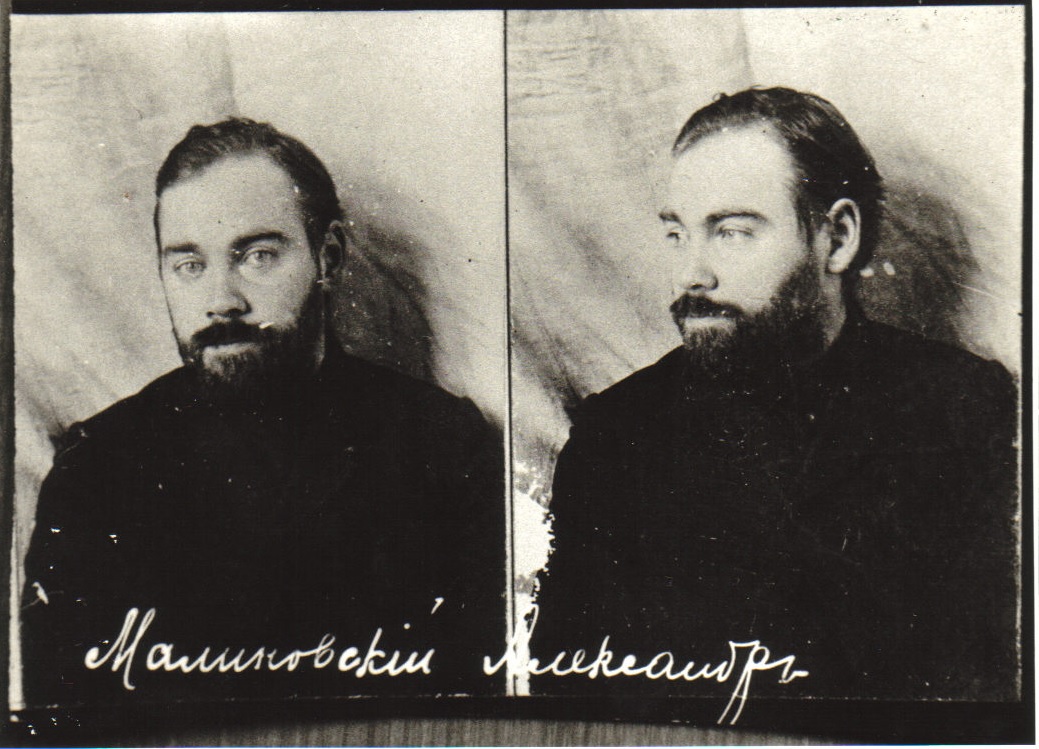

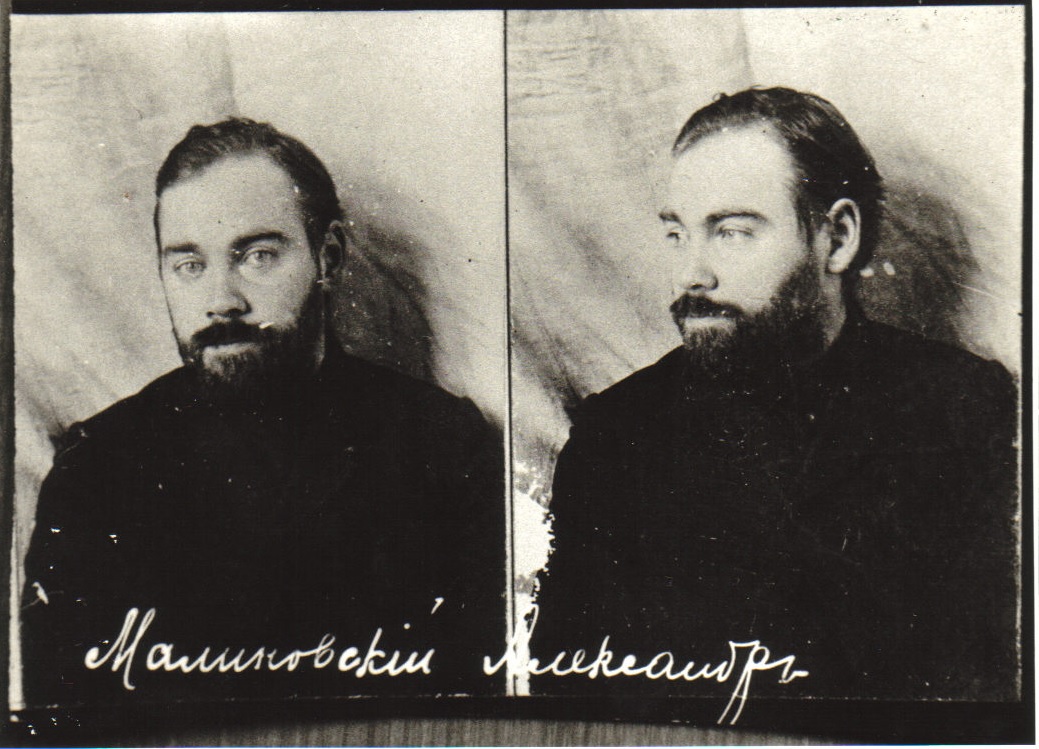

Alexander Aleksandrovich Bogdanov (; – 7 April 1928), born Alexander Malinovsky, was a

Bogdanov dated his support for Bolshevism from autumn of 1903. Early in 1904,

Bogdanov dated his support for Bolshevism from autumn of 1903. Early in 1904,

At the beginning of February 1918, Bogdanov denied that the Bolsheviks' October seizure to power had constituted a conspiracy. Rather, he explained that an explosive situation had arisen through the prolongation of the war. He pointed to a lack of cultural development in that all strata of society, whether the bourgeoisie, the intelligentsia, or the workers, had shown a failure to resolve conflicts through negotiation. He described the revolution as being a combination of a peasant revolution in the countryside and a soldier-worker revolution in the cities. He regarded it as paradoxical that the peasantry expressed itself through the Bolshevik party rather than through the

At the beginning of February 1918, Bogdanov denied that the Bolsheviks' October seizure to power had constituted a conspiracy. Rather, he explained that an explosive situation had arisen through the prolongation of the war. He pointed to a lack of cultural development in that all strata of society, whether the bourgeoisie, the intelligentsia, or the workers, had shown a failure to resolve conflicts through negotiation. He described the revolution as being a combination of a peasant revolution in the countryside and a soldier-worker revolution in the cities. He regarded it as paradoxical that the peasantry expressed itself through the Bolshevik party rather than through the

Очерки организационной науки

(Ocherki organizatsionnoi nauki) ''Proletarskaya kul'tura'', No. 7/8 (April–May) *

(1918), ''

Religion, Art and Marxism

, ''Labour Monthly'', Vol VI, No. 8, August 1924 * ''Essays in Tektology: The General Science of Organization'', translated by George Gorelik (Seaside, CA: Intersystems Publications, 1980) *

A Short Course of Economics Science

', (London: Communist Party of Great Britain, 1923) * ''Bogdanov's Tektology. Book 1'', edited by Peter Dudley (Hull, UK: Centre for Systems Studies Press, 1996). *

The Philosophy of Living Experience

' (1913/2015). Translated, edited and introduced by David G. Rowley, Leiden & Boston: Brill (2015) *

Empiriomonism: Essays in Philosophy, Books 1–3

'. Edited and translated by David G. Rowley, Leiden & Boston: Brill (2019)

Two Events Celebrating the Life and Contribution of Alexander Bogdanov

hosted by the Centre for Systems Studies on 2–3 June 2021 *

Google Books preview as of 20101006

* Rosenthal, Bernice Glatzer. 2002. ''New Myth, New World: From Nietzsche to Stalinism''. The Pennsylvania State University Press

Google Books preview as of 20101006

* Sochor, Zenovia. 1988. ''Revolution and Culture: The Bogdanov-Lenin Controversy''. Cornell University Press. * ''Socialist Standard''. 2007 April

106 (1232): 10. * Souvarine, Boris. 1939. ''Stalin: A Critical Survey of Bolshevism''. New York: Alliance Group Corporation; Longmans, Green, and Co. * Woods, Alan. 1999. ''Bolshevism: The Road to Revolution''. Wellred Publications.

Part Three: The Period of Reaction

Alexander Bogdanov Archive at marxists.org

Biographic essay (English)

International Alexander Bogdanov Institute

(Russian)

Short biography and bibliography

in the

Red Hamlet

*

''Science in Russia and the Soviet Union'': ''A Short History''

Loren R. Graham (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993 – Russian technocratic influence of engineers, subsequent deaths, trials and imprisonments

John A. Mikes, prepared for the nternational Conference on Complex SystemsNew England Complex Systems Institute, September 21–27, 1997, in

Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

and later Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

physician

A physician, medical practitioner (British English), medical doctor, or simply doctor is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through the Medical education, study, Med ...

, philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, science fiction

Science fiction (often shortened to sci-fi or abbreviated SF) is a genre of speculative fiction that deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts. These concepts may include information technology and robotics, biological manipulations, space ...

writer and Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

revolutionary

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates for, a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective to describe something producing a major and sudden impact on society.

Definition

The term—bot ...

. He was a polymath

A polymath or polyhistor is an individual whose knowledge spans many different subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems. Polymaths often prefer a specific context in which to explain their knowledge, ...

who pioneered blood transfusion

Blood transfusion is the process of transferring blood products into a person's Circulatory system, circulation intravenously. Transfusions are used for various medical conditions to replace lost components of the blood. Early transfusions used ...

, as well as general systems theory

Systems theory is the Transdisciplinarity, transdisciplinary study of systems, i.e. cohesive groups of interrelated, interdependent components that can be natural or artificial. Every system has causal boundaries, is influenced by its context, de ...

, and made important contributions to cybernetics

Cybernetics is the transdisciplinary study of circular causal processes such as feedback and recursion, where the effects of a system's actions (its outputs) return as inputs to that system, influencing subsequent action. It is concerned with ...

.

He was a key figure in the early history of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party (RSDWP) or the Russian Social Democratic Party (RSDP), was a socialist political party founded in 1898 in Minsk, Russian Empire. The ...

(later the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),. Abbreviated in Russian as КПСС, ''KPSS''. at some points known as the Russian Communist Party (RCP), All-Union Communist Party and Bolshevik Party, and sometimes referred to as the Soviet ...

), originally established 1898, and of its Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

faction. Bogdanov co-founded the Bolsheviks in 1903, when they split with the Menshevik

The Mensheviks ('the Minority') were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903. Mensheviks held more moderate and reformist ...

faction. He was a rival within the Bolsheviks to Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

(1870–1924), until being expelled in 1909 and founding his own faction Vpered

Vpered ( rus, Вперёд, p=fpʲɪˈrʲɵt, a=Ru-вперёд.ogg, ''Forward'') was a subfaction within the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP). Although Vpered emerged from the Bolshevik wing of the party, it was critical of Lenin ...

. Following the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

s of 1917, when the Bolsheviks came to power in the collapsing Russian Republic

The Russian Republic,. referred to as the Russian Democratic Federative Republic in the 1918 Constitution, was a short-lived state which controlled, ''de jure'', the territory of the former Russian Empire after its proclamation by the Rus ...

, he was an influential opponent of the Bolshevik government and Lenin from a Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

leftist perspective during the first decade of the subsequent Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

in the 1920s.

Bogdanov received training in medicine and psychiatry. His wide scientific and medical interests ranged from the universal systems theory

Systems theory is the Transdisciplinarity, transdisciplinary study of systems, i.e. cohesive groups of interrelated, interdependent components that can be natural or artificial. Every system has causal boundaries, is influenced by its context, de ...

to the possibility of human rejuvenation

Rejuvenation is a medical discipline focused on the practical reversal of the aging process.

Rejuvenation is distinct from life extension. Life extension strategies often study the causes of aging and try to oppose those causes to slow aging. ...

through blood transfusion

Blood transfusion is the process of transferring blood products into a person's Circulatory system, circulation intravenously. Transfusions are used for various medical conditions to replace lost components of the blood. Early transfusions used ...

. He invented an original philosophy called "tectology

Tektology (sometimes transliterated as tectology) is a term used by Alexander Bogdanov to describe a new universal science that consisted of unifying all social, biological and physical sciences by considering them as systems of relationships and ...

", now regarded as a forerunner of systems theory

Systems theory is the Transdisciplinarity, transdisciplinary study of systems, i.e. cohesive groups of interrelated, interdependent components that can be natural or artificial. Every system has causal boundaries, is influenced by its context, de ...

. He was also an economist, culture theorist, science fiction writer, and political activist. Lenin depicted him as one of the " Russian Machists".

Early years

A Russian born inBelarus

Belarus, officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Belarus spans an a ...

, Alexander Malinovsky was born in Sokółka

Sokółka (; , ) is a town in northeastern Poland, seat of the Sokółka County in Podlaskie Voivodeship. It is a busy rail junction located on the international Warsaw–Białystok–Grodno line, with additional connections which go to Suwałki a ...

, Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

(now Poland), into a rural teacher's family, the second of six children. He attended the Gymnasium at Tula, which he compared to a barracks or prison. He was awarded a gold medal when he graduated.

Upon completion of the gymnasium, Bogdanov was admitted to the Natural Science Department of Imperial Moscow University

Imperial Moscow University () was one of the oldest universities of the Russian Empire, established in 1755. It was the first of the twelve imperial universities of the Russian Empire. Its legacy is continued as Lomonosov Moscow State Universit ...

. In his autobiography, Bogdanov reported that, while studying at Moscow University, he joined the Union Council of Regional Societies and was arrested and exiled to Tula because of it.

The head of the Moscow Okhrana

The Department for the Protection of Public Safety and Order (), usually called the Guard Department () and commonly abbreviated in modern English sources as the Okhrana ( rus , Охрана, p=ɐˈxranə, a=Ru-охрана.ogg, t= The Guard) w ...

had used an informant to acquire the names of members of the Union Council of Regional Societies, which included Bogdanov's name. On October 30, 1894, students rowdily demonstrated against a lecture by the history Professor Vasily Klyuchevsky

Vasily Osipovich Klyuchevsky (; – ) was a leading Russian Empire, Russian Imperial historian of the late imperial period. He also addressed the contemporary Russian economy in his writings.

Biography

A village priest's son, Klyuchevsky studi ...

who, despite being a well-known liberal, had written a favourable eulogy for the recently deceased Tsar Alexander III of Russia

Alexander III (; 10 March 18451 November 1894) was Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Poland and Grand Duke of Finland from 13 March 1881 until his death in 1894. He was highly reactionary in domestic affairs and reversed some of the libera ...

. Punishment of a few of the students was seen as so arbitrary and unfair that the Union Council requested a fair reexamination of the issue. That very night, the Okhrana arrested all the students on the list mentioned above – including Bogdanov – all of whom were expelled from the university and banished to their hometowns.

Expelled from Moscow State University, he enrolled as an external student at the University of Kharkov, from which he graduated as a physician in 1899. Bogdanov remained in Tula from 1894 to 1899, where – since his own family was living in Sokółka – he lodged with Alexander Rudnev, the father of Vladimir Bazarov

Vladimir Alexandrovich Bazarov (Russian: Влади́мир Алекса́ндрович База́ров; 8 August O. S. 27 July">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 27 July1874 – 16 Septem ...

, who became a close friend and collaborator in future years. Here he met and married Natalya Bogdanovna Korsak, who, as a woman, had been refused entrance to the university. She was eight years older than he was and worked as a nurse for Rudnev. Malinovsky adopted the pen name

A pen name or nom-de-plume is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen name may be used to make the author's na ...

that he used when he wrote his major theoretical works and his novels from her patronym

A patronymic, or patronym, is a component of a personal name based on the given name of one's father, grandfather (more specifically an avonymic), or an earlier male ancestor. It is the male equivalent of a matronymic.

Patronymics are used, ...

.

Alongside Bazarov and Ivan Skvortsov-Stepanov

Ivan Ivanovich Skvortsov-Stepanov (; 8 March O.S. 24 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 24 February1870 – 8 October 1928) was a prominent Russian Bolshevik revolutionary and Sovie ...

he became a tutor in a workers' study circle A study circle is a small group of people who meet multiple times to discuss an issue. Study circles may be formed to discuss anything from politics to religion to hobbies with a minimum of 7 people to a maximum of 15. These study circles are formed ...

. This was organised in the Tula Armament Factory by Ivan Saveliev, whom Bogdanov credited with founding Social Democracy

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

in Tula. During this period, he wrote his ''Brief course of economic science'', which was published – "subject to many modifications made for the benefit of the censor" – only in 1897. He later said that this experience of student-led education gave him his first lesson in proletarian culture

Working-class culture or proletarian culture is a range of cultures created by or popular among working-class people. The cultures can be contrasted with high culture and folk culture, and are often equated with popular culture and low culture (t ...

.

In autumn 1895, he resumed his medical studies at the university of Kharkiv

Kharkiv, also known as Kharkov, is the second-largest List of cities in Ukraine, city in Ukraine.

(Ukraine) but still spent much time in Tula. He came across the works of Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

in 1896, particularly the latter's critique of Peter Berngardovich Struve

Peter (or Pyotr or Petr) Berngardovich Struve (, ; – 22 February 1944) was a Russian political economist, philosopher, historian and editor. He started his career as a Marxist, later became a liberal and after the Bolshevik Revolution, joined ...

. In 1899, he graduated as a medical doctor and published his next work, "Basic elements of the historical perspective on nature". However, because of his political views, he was also arrested by the Tsar's police, spent six months in prison, and was exiled to Vologda

Vologda (, ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Vologda Oblast, Russia, located on the river Vologda (river), Vologda within the watershed of the Northern Dvina. Population:

The city serves as ...

.

Bolshevism

Bogdanov dated his support for Bolshevism from autumn of 1903. Early in 1904,

Bogdanov dated his support for Bolshevism from autumn of 1903. Early in 1904, Martyn Liadov

Martyn Nikolaevich Liadov, (Russian: Мартын Николаевичч Лядов) pseudonym of Martyn Nikolaevich Mandel’shtam (24 August 1872 – 6 January 1947), was a Bolshevik revolutionary activist and historian.

Biography

Liadov was ...

was sent by the Bolsheviks in Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

to seek out supporters in Russia. He found a sympathetic group of revolutionaries, including Bogdanov, in Tver

Tver (, ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative centre of Tver Oblast, Russia. It is situated at the confluence of the Volga and Tvertsa rivers. Tver is located northwest of Moscow. Population:

The city is ...

. Bogdanov was then sent by the Tver Committee to Geneva, where he was greatly impressed by Lenin's ''One Step Forward, Two Steps Back

''One Step Forward, Two Steps Back: The Crisis in Our Party'' () is a work written by Vladimir Lenin and published on May 6/19, 1904. In it Lenin defends his role in the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, held in Brussel ...

''. Back in Russia during the 1905 Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905, also known as the First Russian Revolution, was a revolution in the Russian Empire which began on 22 January 1905 and led to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy under the Russian Constitution of 1906, t ...

, Bogdanov was arrested on 3 December 1905 and held in prison until 27 May 1906. Upon release, he was exiled to Bezhetsk

Bezhetsk () is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, town and the administrative center of Bezhetsky District in Tver Oblast, Russia, located on the Mologa River at its confluence with the Ostrechina. Population: 20,618 (2024). It was pr ...

for three years. However, he obtained permission to spend his exile abroad, and joined Lenin in Kokkola

Kokkola (; , ) is a town in Finland and the regional capital of Central Ostrobothnia. It is located on the west coast of the country, on the Gulf of Bothnia. The population of Kokkola is approximately , while the Kokkola sub-region, sub-region h ...

, Finland.

For the next six years, Bogdanov was a major figure among the early Bolsheviks, second only to Lenin in influence. In 1904–1906, he published three volumes of the philosophic treatise ''Empiriomonizm'' (''Empiriomonism''), in which he tried to merge Marxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

with the philosophy of Ernst Mach

Ernst Waldfried Josef Wenzel Mach ( ; ; 18 February 1838 – 19 February 1916) was an Austrian physicist and philosopher, who contributed to the understanding of the physics of shock waves. The ratio of the speed of a flow or object to that of ...

, Wilhelm Ostwald

Wilhelm Friedrich Ostwald (; – 4 April 1932) was a Latvian chemist and philosopher. Ostwald is credited with being one of the founders of the field of physical chemistry, with Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff, Walther Nernst and Svante Arrhenius. ...

, and Richard Avenarius

Richard Ludwig Heinrich Avenarius (born Richard Habermann; 19 November 1843 – 18 August 1896) was a French-born German-Swiss philosopher. He formulated the radical positivist doctrine of "empirical criticism" or empirio-criticism.

Life

Avenar ...

. His work later affected a number of Russian Marxist theoreticians, including Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (; rus, Николай Иванович Бухарин, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj ɪˈvanəvʲɪdʑ bʊˈxarʲɪn; – 15 March 1938) was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and Marxist theorist. A prominent Bolshevik ...

. In 1907, he helped organize the 1907 Tiflis bank robbery

The 1907 Tiflis bank robbery, also known as the Erivansky Square expropriation, was an armed robbery on 26 June 1907 in the city of Tiflis (present-day Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia (country), Georgia) in the Tiflis Governorate in the Caucasus ...

with both Lenin and Leonid Krasin

Leonid Borisovich Krasin (; – 24 November 1926) was a Russians, Russian Soviet Union, Soviet politician, engineer, social entrepreneur, Bolshevik revolutionary and a Soviet diplomat. In 1924 he became the first List of ambassadors of Russia to ...

.

For four years after the collapse of the Russian Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905, also known as the First Russian Revolution, was a revolution in the Russian Empire which began on 22 January 1905 and led to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy under the Russian Constitution of 1906, t ...

, Bogdanov led a group within the Bolsheviks ("ultimatists In the course of the history of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP between 1898 and 1918), several political factions developed, as well as the major split between the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks.

*Bolsheviks, formed in 1903 from ...

" and " otzovists" or "recallists"), who demanded a recall of Social Democratic deputies from the State Duma

The State Duma is the lower house of the Federal Assembly (Russia), Federal Assembly of Russia, with the upper house being the Federation Council (Russia), Federation Council. It was established by the Constitution of Russia, Constitution of t ...

, and he vied with Lenin for the leadership of the Bolshevik faction. In 1908 he joined Bazarov, Lunacharsky

Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky (, born ''Anatoly Aleksandrovich Antonov''; – 26 December 1933) was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and the first Soviet People's Commissar (minister) of Education, as well as an active playwright, critic, es ...

, Berman Berman is a surname that may be derived from the German and Yiddish phrase ( ‘bear-man’) or from the Dutch , meaning the same. Notable people with the surname include:

* Abba Berman (1919–2005), Polish-Israeli Rosh Yeshiva

* Adolf Berman ( ...

, Helfond, Yushkevich and Suvorov

Count Alexander Vasilyevich Suvorov-Rymniksky, Prince of Italy () was a Russian general and military theorist in the service of the Russian Empire.

Born in Moscow, he studied military history as a young boy and joined the Imperial Russian ...

in a symposium ''Studies in the Philosophy of Marxism'' which espoused the views of the Russian Marxists. By mid-1908, the factionalism within the Bolsheviks had become irreconcilable. A majority of Bolshevik leaders either supported Bogdanov or were undecided between him and Lenin.

Lenin concentrated on undermining Bogdanov's reputation as a philosopher. In 1909 he published a scathing book of criticism entitled ''Materialism and Empiriocriticism

''Materialism and Empirio-criticism'' (Russian: Материализм и эмпириокритицизм, ''Materializm i empiriokrititsizm'') is a philosophical work by Vladimir Lenin, published in 1909. It was an obligatory subject of study ...

'', assaulting Bogdanov's position and accusing him of philosophical idealism

Idealism in philosophy, also known as philosophical realism or metaphysical idealism, is the set of metaphysical perspectives asserting that, most fundamentally, reality is equivalent to mind, spirit, or consciousness; that reality is entir ...

. In June 1909, Bogdanov was defeated by Lenin at a Bolshevik mini-conference in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

organized by the editorial board of the Bolshevik magazine ''Proletary

''Proletary'' (The Proletarian) was an illegal Russian Bolshevik newspaper edited by Lenin; it was published from September 3, 1906, until December 11, 1909. A total of fifty issues having appeared. Active participants in the editorial work were ...

'' and was expelled from the Bolsheviks.

He joined his brother-in-law Anatoly Lunacharsky

Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky (, born ''Anatoly Aleksandrovich Antonov''; – 26 December 1933) was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and the first Soviet People's Commissariat for Education, People's Commissar (minister) of Education, as well ...

, Maxim Gorky

Alexei Maximovich Peshkov (; – 18 June 1936), popularly known as Maxim Gorky (; ), was a Russian and Soviet writer and proponent of socialism. He was nominated five times for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Before his success as an aut ...

, and other Vpered

Vpered ( rus, Вперёд, p=fpʲɪˈrʲɵt, a=Ru-вперёд.ogg, ''Forward'') was a subfaction within the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP). Although Vpered emerged from the Bolshevik wing of the party, it was critical of Lenin ...

ists on the island of Capri

Capri ( , ; ) is an island located in the Tyrrhenian Sea off the Sorrento Peninsula, on the south side of the Gulf of Naples in the Campania region of Italy. A popular resort destination since the time of the Roman Republic, its natural beauty ...

, where they started the Capri Party School The Capri Party School (Russian: Каприйская школа), known by its official name as "The First Higher Social Democratic Propaganda and Agitational School for Workers." was an educational organisation established by the Vperedists, a su ...

for Russian factory workers. In 1910, Bogdanov, Lunacharsky, Mikhail Pokrovsky

Mikhail Nikolayevich Pokrovsky (; – April 10, 1932) was a Russian Marxist historian, revolutionary and a Soviet public and political figure. One of the earliest professionally trained historians to join the Russian revolutionary movement, Pokr ...

, and their supporters moved the school to Bologna

Bologna ( , , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy. It is the List of cities in Italy, seventh most populous city in Italy, with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nationalities. Its M ...

, where they continued teaching classes through 1911, while Lenin and his allies soon started the Longjumeau Party School just outside of Paris.

Bogdanov broke with the ''Vpered

Vpered ( rus, Вперёд, p=fpʲɪˈrʲɵt, a=Ru-вперёд.ogg, ''Forward'') was a subfaction within the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP). Although Vpered emerged from the Bolshevik wing of the party, it was critical of Lenin ...

'' in 1912 and abandoned revolutionary activities. After six years of his political exile in Europe, Bogdanov returned to Russia in 1914, following the political amnesty declared by Tsar Nicholas II

Nicholas II (Nikolai Alexandrovich Romanov; 186817 July 1918) or Nikolai II was the last reigning Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Poland, and Grand Duke of Finland from 1 November 1894 until his abdication on 15 March 1917. He married ...

as part of the festivities connected with the tercentenary of the Romanov Dynasty.

During World War I

Bogdanov was drafted soon after the outbreak ofWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and was assigned as a junior regimental doctor with the 221st Smolensk

Smolensk is a city and the administrative center of Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the Dnieper River, west-southwest of Moscow.

First mentioned in 863, it is one of the oldest cities in Russia. It has been a regional capital for most of ...

infantry division in the Second Army commanded by General Alexander Samsonov

Aleksandr Vasilyevich Samsonov (, tr. ; ) was a career officer in the cavalry of the Imperial Russian Army and a general during the Russo-Japanese War and World War I. He was the commander of the Russian Second Army which was surrounded and d ...

. In the Battle of Tannenberg, August 26–30, the Second Army was surrounded and almost completely destroyed, but Bogdanov survived because he had been sent to accompany a seriously wounded officer to Moscow. However following the Second Battle of the Masurian Lakes

The Second Battle of the Masurian Lakes or Winter Battle of the Masurian Lakes, known in Germany as the Winter Battle in Masuria and in Russia as the Battle of Augustowo,Benninghof, p. 5. was the northern part of the Central Powers' offensive on ...

, he succumbed to a nervous disorder

Anxiety disorders are a group of mental disorders characterized by significant and uncontrollable feelings of anxiety and fear such that a person's social, occupational, and personal functions are significantly impaired. Anxiety may cause phys ...

and subsequently became junior house surgeon at an evacuation hospital.

In 1916 he wrote four articles for ''Vpered

Vpered ( rus, Вперёд, p=fpʲɪˈrʲɵt, a=Ru-вперёд.ogg, ''Forward'') was a subfaction within the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP). Although Vpered emerged from the Bolshevik wing of the party, it was critical of Lenin ...

'' which provided an analysis of the World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and the dynamics of war economies. He attributed a central role to the armed forces in the economic restructuring of the belligerent powers. He saw the army as creating a "consumers' communism" with the state taking over ever-increasing parts of the economy.

At the same time military authoritarianism had also spread to civil society. This created the conditions for two consequences: consumption-led war communism

War communism or military communism (, ''Vojenný kommunizm'') was the economic and political system that existed in Soviet Russia during the Russian Civil War from 1918 to 1921. War communism began in June 1918, enforced by the Supreme Economi ...

and the destruction of the means of production. He thus predicted that even after the war, the new system of state capitalism

State capitalism is an economic system in which the state undertakes business and commercial economic activity and where the means of production are nationalized as state-owned enterprises (including the processes of capital accumulation, ...

would replace that of finance capitalism

Finance capitalism or financial capitalism is the subordination of processes of production to the accumulation of money profits in a financial system.

Financial capitalism is thus a form of capitalism where the intermediation of saving to inves ...

even though the destruction of the forces of production would cease.

During the Russian Revolution

Bogdanov had no party-political involvement in theRussian Revolution of 1917

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

, although he did publish a number of articles and books about the events that unfurled around him. He supported the Zimmerwald

Zimmerwald () was an independent municipality in the Canton of Bern, Switzerland until 31 December 2003. It is located on a hill in the proximity of the city of Bern in the Bernese Mittelland. On 1 January 2004 Zimmerwald united with the municipa ...

ist programme of "peace without annexations or indemnities". He deplored the Provisional Government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, a transitional government or provisional leadership, is a temporary government formed to manage a period of transition, often following state collapse, revoluti ...

's continued prosecution of the war. After the July Days

The July Days () were a period of unrest in Petrograd, Russia, between . It was characterised by spontaneous armed demonstrations by soldiers, sailors, and industrial workers engaged against the Russian Provisional Government. The demonstrat ...

, he advocated "revolutionary democracy" as he now considered the socialists capable of forming a government. However, he viewed this as a broad-based socialist provisional government that would convene a Constituent Assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

.

In May 1917, he published ''Chto my svergli'' in ''Novaya Zhizn''. Here he argued that between 1904 and 1907, the Bolsheviks had been "decidedly democratic" and that there was no pronounced cult of leadership. However, following the decision of Lenin and the émigré group around him to break with ''Vpered'' in order to unify with the Mensheviks, the principle of leadership became more pronounced. After 1912, when Lenin insisted on splitting the Duma group of the RSDLP, the leadership principle became entrenched. However, he saw this problem as not being confined to the Bolsheviks, noting that similar authoritarian ways of thinking were shown in the Menshevik attitude to Plekhanov, or the cult of heroic individuals and leaders amongst the Narodnik

The Narodniks were members of a movement of the Russian Empire intelligentsia in the 1860s and 1870s, some of whom became involved in revolutionary agitation against tsarism. Their ideology, known as Narodism, Narodnism or ,; , similar to the ...

s.

After the October Revolution

At the beginning of February 1918, Bogdanov denied that the Bolsheviks' October seizure to power had constituted a conspiracy. Rather, he explained that an explosive situation had arisen through the prolongation of the war. He pointed to a lack of cultural development in that all strata of society, whether the bourgeoisie, the intelligentsia, or the workers, had shown a failure to resolve conflicts through negotiation. He described the revolution as being a combination of a peasant revolution in the countryside and a soldier-worker revolution in the cities. He regarded it as paradoxical that the peasantry expressed itself through the Bolshevik party rather than through the

At the beginning of February 1918, Bogdanov denied that the Bolsheviks' October seizure to power had constituted a conspiracy. Rather, he explained that an explosive situation had arisen through the prolongation of the war. He pointed to a lack of cultural development in that all strata of society, whether the bourgeoisie, the intelligentsia, or the workers, had shown a failure to resolve conflicts through negotiation. He described the revolution as being a combination of a peasant revolution in the countryside and a soldier-worker revolution in the cities. He regarded it as paradoxical that the peasantry expressed itself through the Bolshevik party rather than through the Socialist Revolutionaries

The Socialist Revolutionary Party (SR; ,, ) was a major socialist political party in the late Russian Empire, during both phases of the Russian Revolution, and in early Soviet Russia. The party members were known as Esers ().

The SRs were agr ...

.

He analysed the effect of the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

as creating 'War Communism

War communism or military communism (, ''Vojenný kommunizm'') was the economic and political system that existed in Soviet Russia during the Russian Civil War from 1918 to 1921. War communism began in June 1918, enforced by the Supreme Economi ...

', which he defined as a form of 'consumer communism', which created the circumstances for the development of state capitalism

State capitalism is an economic system in which the state undertakes business and commercial economic activity and where the means of production are nationalized as state-owned enterprises (including the processes of capital accumulation, ...

. He saw military state capitalism as a temporary phenomenon in the West, lasting only as long as the war. However, thanks to the predominance of the soldiers in the Bolshevik Party, he regarded it as inevitable that their backwardness should predominate in the re-organisation of society. Instead of proceeding in a methodical fashion, the pre-existing state was simply uprooted. The military-consumerist approach of simply requisitioning what was required had predominated and could not cope with the more complex social relations necessitated by the market:

He refused multiple offers to rejoin the party and denounced the new regime as similar to Aleksey Arakcheyev

Count Alexey Andreyevich Arakcheyev or Arakcheev (; b. in Garusovo – d. in Gruzino) was an Imperial Russian general and statesman during the reign of Tsar Alexander I.

He served under Tsars Paul I and Alexander I as an army commander an ...

's arbitrary and despotic rule in the early 1820s.

In 1918, Bogdanov became a professor of economics at the University of Moscow

Moscow State University (MSU), officially M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University,. is a public research university in Moscow, Russia. The university includes 15 research institutes, 43 faculties, more than 300 departments, and six branches. Al ...

and director of the newly established Socialist Academy of Social Sciences

The Socialist Academy of Social Sciences (SAON) was an educational establishment created in Russia in October 1918 with "the aim of studying and teaching social studies from the point of view of scientific socialism." The original name of the acade ...

.

Proletkult

Between 1918 and 1920, Bogdanov co-founded the proletarian art movementProletkult

Proletkult ( rus, Пролетку́льт, p=prəlʲɪtˈkulʲt), a portmanteau of the Russian words "proletarskaya kultura" ( proletarian culture), was an experimental Soviet artistic institution that arose in conjunction with the Russian Revol ...

and was its leading theoretician. In his lectures and articles, he called for the total destruction of the "old bourgeois culture" in favour of a "pure proletarian culture" of the future. It was also through Proletkult that Bogdanov's educational theories were given form with the establishment of the Moscow Proletarian University

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

.

At first Proletkult, like other radical cultural movements of the era, received financial support from the Bolshevik government, but by 1920, the Bolshevik leadership grew hostile, and on December 1, 1920, ''Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, 'Truth') is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most in ...

'' published a decree denouncing Proletkult as a "petit bourgeois" organization operating outside of Soviet institutions and a haven for "socially alien elements". Later in that month, the president of Proletkult was removed, and Bogdanov lost his seat on its Central Committee. He withdrew from the organization completely in 1921–1922.

Arrest

Bogdanov gave a lecture to a club atMoscow University

Moscow State University (MSU), officially M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University,. is a public research university in Moscow, Russia. The university includes 15 research institutes, 43 faculties, more than 300 departments, and six branches. Al ...

, which, according to Yakov Yakovlev

Yakov Arkadyevich Yakovlev (real name: Epstein; , 9 June 1896 – 29 July 1938) was a Soviet politician and statesman who played a central role in the forced collectivisation of agriculture in the 1920s.

Early career

Yakov Yakovlev was born in ...

, included an account of the formation of Vpered

Vpered ( rus, Вперёд, p=fpʲɪˈrʲɵt, a=Ru-вперёд.ogg, ''Forward'') was a subfaction within the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP). Although Vpered emerged from the Bolshevik wing of the party, it was critical of Lenin ...

and reiterated some of the criticisms Bogdanov had made at the time of the individualism of certain leaders. Yakovlev further claimed that Bogdanov discussed the development of the concept of proletarian culture up to the present day and discussed to what extent the Communist Party saw Proletkult as a rival. Bogdanov hinted at the prospect of a new International that might emerge if there were a revival of the socialist movement in the West. He said he envisaged such an International as merging political, trade union, and cultural activities into a single organisation. Yakovlev characterised these ideas as Menshevik

The Mensheviks ('the Minority') were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903. Mensheviks held more moderate and reformist ...

, pointing to the refusal of ''Vpered'' to acknowledge the authority of the 1912 Prague Conference

The Prague Conference, officially the 6th All-Russian Conference of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, was held in Prague, Austria-Hungary (Present-Day Czechia), on 5–17 January 1912. Sixteen Bolsheviks and two Mensheviks attended, alt ...

. He cited Bogdanov's characterization of the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

as "soldiers'-peasants' revolt", his criticisms of the New Economic Policy

The New Economic Policy (NEP) () was an economic policy of the Soviet Union proposed by Vladimir Lenin in 1921 as a temporary expedient. Lenin characterized the NEP in 1922 as an economic system that would include "a free market and capitalism, ...

, and his description of the new regime as expressing the interests of a new class of technocratic and bureaucratic intelligentsia, as evidence that Bogdanov was involved in forming a new party.

Meanwhile, ''Workers' Truth

The Workers' Truth () was a Russian socialist opposition group founded in 1921. They published a newspaper with the same name, ''Workers' Truth'', which first appeared in September 1921.

The Workers' Truth considered that the Soviet economy ha ...

'' had received publicity in the Berlin-based Menshevik journal ''Sotsialisticheskii Vestnik'', and they also distributed a manifesto at the 12th Bolshevik Congress and were active in the industrial unrest which swept Moscow and Petrograd

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea. The city had a population of 5,601, ...

in July and August 1923. On 8 September 1923, Bogdanov was among a number of people arrested by the GPU

A graphics processing unit (GPU) is a specialized electronic circuit designed for digital image processing and to accelerate computer graphics, being present either as a discrete video card or embedded on motherboards, mobile phones, personal ...

(the Soviet secret police) on suspicion of being involved in them. He demanded to be interviewed by Felix Dzerzhinsky

Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky (; ; – 20 July 1926), nicknamed Iron Felix (), was a Soviet revolutionary and politician of Polish origin. From 1917 until his death in 1926, he led the first two Soviet secret police organizations, the Cheka a ...

, to whom he explained that while he shared a range of views with ''Workers' Truth'', he had no formal association with them. He was released after five weeks on 13 October; however, his file was not closed until a decree passed by the Supreme Soviet of the USSR

The Supreme Soviet of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (SSUSSR) was the highest body of state authority of the Soviet Union (USSR) from 1936 to 1991. Based on the principle of unified power, it was the only branch of government in the S ...

on 16 January 1989. He wrote about his experiences under arrest in ''Five weeks with the GPU''.

Later years and death

In 1922 whilst visiting London to negotiate theAnglo-Soviet Trade Agreement

The Anglo-Soviet Trade Agreement was an agreement signed on 16 March 1921 to facilitate trade between the United Kingdom and the Russian Socialist Federal Soviet Republic. It was signed by Robert Horne, Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leonid Kra ...

, Bogdanov acquired a copy of the British surgeon Geoffrey Keynes

Sir Geoffrey Langdon Keynes ( ; 25 March 1887, Cambridge – 5 July 1982, Cambridge) was a British surgeon and author. He began his career as a physician in World War I, before becoming a doctor at St Bartholomew's Hospital in London, where he ...

's book ''Blood Transfusion''. Returning to Moscow, he founded the Institute for Haematology and Blood Transfusions in 1924-25 and started blood transfusion

Blood transfusion is the process of transferring blood products into a person's Circulatory system, circulation intravenously. Transfusions are used for various medical conditions to replace lost components of the blood. Early transfusions used ...

experiments, apparently hoping to achieve eternal youth

Eternal youth is the concept of human physical immortality free of ageing. The youth referred to is usually meant to be in contrast to the depredations of aging, rather than a specific age of the human lifespan. Eternal youth is common in mytho ...

or at least partial rejuvenation

Rejuvenation is a medical discipline focused on the practical reversal of the aging process.

Rejuvenation is distinct from life extension. Life extension strategies often study the causes of aging and try to oppose those causes to slow aging. ...

. Lenin's sister Maria Ulyanova was among many who volunteered to take part in Bogdanov's experiments. After undergoing 11 blood transfusions, he remarked with satisfaction the improvement of his eyesight, suspension of balding, and other positive symptoms. His fellow revolutionary Leonid Krasin

Leonid Borisovich Krasin (; – 24 November 1926) was a Russians, Russian Soviet Union, Soviet politician, engineer, social entrepreneur, Bolshevik revolutionary and a Soviet diplomat. In 1924 he became the first List of ambassadors of Russia to ...

wrote to his wife that "Bogdanov seems to have become 7, no, 10 years younger after the operation". In 1925–1926, Bogdanov founded the Institute for Haematology

Hematology ( spelled haematology in British English) is the branch of medicine concerned with the study of the cause, prognosis, treatment, and prevention of diseases related to blood. It involves treating diseases that affect the production ...

and Blood Transfusions, which was later named after him.

A later transfusion in 1928 cost him his life, when he took the blood of a student suffering from malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

and tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

. The student injected with his blood made a complete recovery. Some scholars (e.g. Loren Graham

Loren R. Graham (June 29, 1933 – December 15, 2024) was an American historian of science, particularly science in Russia.

Early life and career

Graham was born on June 29, 1933. He earned his B.A. in chemical engineering at Purdue Universit ...

) have speculated that his death may have been a suicide, because Bogdanov wrote a highly nervous political letter shortly beforehand. However, his death could be attributed to the adverse effects of blood transfusion, which were poorly understood at the time.

Legacy

Both Bogdanov's fiction and his political writings imply that he expected the coming revolution againstcapitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

to lead to a technocratic

Technocracy is a form of government in which decision-makers appoint knowledge experts in specific domains to provide them with advice and guidance in various areas of their policy-making responsibilities. Technocracy follows largely in the tra ...

society. This was because the workers lacked the knowledge and initiative to seize control of social affairs for themselves as a result of the hierarchical and authoritarian nature of the capitalist production process. However, Bogdanov also considered that the hierarchical and authoritarian mode of organization of the Bolshevik party was also partly to blame, although Bogdanov considered at least some such organization necessary and inevitable.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Bogdanov's theorizing, being the product of a non-Leninist Bolshevik, became an important, though "underground", influence on certain dissident factions in the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

who turned against Bolshevik autocracy while accepting the necessity of the Revolution and wishing to preserve its achievements.

In popular culture

Bogdanov served as an inspiration for the character Arkady Bogdanov inKim Stanley Robinson

Kim Stanley Robinson (born March 23, 1952) is an American science fiction writer best known for his ''Mars'' trilogy. Many of his novels and stories have ecological, cultural, and political themes and feature scientists as heroes. Robinson has ...

's science-fiction novels the Mars Trilogy

The ''Mars'' trilogy is a series of science fiction novels by Kim Stanley Robinson that chronicles the settlement and terraforming of the planet Mars through the personal and detailed viewpoints of a wide variety of characters spanning 187 year ...

. It is revealed in 'Blue Mars' that Arkady is a descendant of Alexander Bogdanov.

Bogdanov is also the protagonist of the novel ''Proletkult'' (2018) by Italian collective Wu Ming

Wu Ming, Chinese language, Chinese for "anonymous", is a pseudonym for a group of Italian authors formed in 2000 from a subset of the Luther Blissett (nom de plume), Luther Blissett community in Bologna.

Four of the group earlier wrote the nove ...

.

Published works

Russian

Non-fiction

* ''Poznanie s Istoricheskoi Tochki Zreniya'' (''Knowledge from a Historical Viewpoint'') (St. Petersburg, 1901) * ''Empiriomonizm: Stat'i po Filosofii'' (''Empiriomonism: Articles on Philosophy'') 3 volumes (Moscow, 1904–1906) * ''Kul'turnye zadachi nashego vremeni'' (''The Cultural Tasks of Our Time'') (Moscow: Izdanie S. Dorovatoskogo i A. Carushnikova 1911) * ''Filosofiya Zhivogo Opyta: Populiarnye Ocherki'' (''Philosophy of Living Experience: Popular Essays'') (St. Petersburg, 1913) * ''Tektologiya: Vseobschaya Organizatsionnaya Nauka'' 3 volumes (Berlin and Petrograd-Moscow, 1922) * "Avtobiografia" in ''Entsiklopedicheskii slovar'', XLI, pp. 29–34 (1926) * ''God raboty Instituta perelivanya krovi'' (''Annals of the Institute of Blood Transfusion'') (Moscow 1926–1927)Fiction

* ''Krasnaya zvezda'' (''Red Star

A red star, five-pointed and filled, is a symbol that has often historically been associated with communist ideology, particularly in combination with the hammer and sickle, but is also used as a purely socialist symbol in the 21st century. ...

'') (St. Petersburg, 1908)

* ''Inzhener Menni'' (''Engineer Menni'') (Moscow: Izdanie S. Dorovatoskogo i A. Carushnikova 1912) The title page carries the date 1913

English translation

Non-fiction

* ''Art and the working class'', translated by Taylor R Genovese (Iskra Books, 2022) * Essays in Organisation Science (1919Очерки организационной науки

(Ocherki organizatsionnoi nauki) ''Proletarskaya kul'tura'', No. 7/8 (April–May) *

(1918), ''

Labour Monthly

''Labour Monthly'' was a magazine associated with the Communist Party of Great Britain. It was not technically published by the Party, and, particularly in its later period, it carried articles by left-wing trade unionists from outside the Party. I ...

'', Vol IV, No. 5–6, May–June 1923

* 'The Criticism of Proletarian Art' (from ''Kritika proletarskogo iskusstva'', 1918) ''Labour Monthly'', Vol V, No. 6, December 1923

*Religion, Art and Marxism

, ''Labour Monthly'', Vol VI, No. 8, August 1924 * ''Essays in Tektology: The General Science of Organization'', translated by George Gorelik (Seaside, CA: Intersystems Publications, 1980) *

A Short Course of Economics Science

', (London: Communist Party of Great Britain, 1923) * ''Bogdanov's Tektology. Book 1'', edited by Peter Dudley (Hull, UK: Centre for Systems Studies Press, 1996). *

The Philosophy of Living Experience

' (1913/2015). Translated, edited and introduced by David G. Rowley, Leiden & Boston: Brill (2015) *

Empiriomonism: Essays in Philosophy, Books 1–3

'. Edited and translated by David G. Rowley, Leiden & Boston: Brill (2019)

Fiction

* ''Red Star

A red star, five-pointed and filled, is a symbol that has often historically been associated with communist ideology, particularly in combination with the hammer and sickle, but is also used as a purely socialist symbol in the 21st century. ...

: The First Bolshevik Utopia'', edited by Loren Graham

Loren R. Graham (June 29, 1933 – December 15, 2024) was an American historian of science, particularly science in Russia.

Early life and career

Graham was born on June 29, 1933. He earned his B.A. in chemical engineering at Purdue Universit ...

and Richard Stites

Richard Stites (December 2, 1931 – March 7, 2010) was a historian of Russian culture and professor of history at Georgetown University, famed for "landmark work on the Russian women’s movement and in numerous articles and books on Russian and ...

; trans. Charles Rougle (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1984):

** ''Red Star'' (1908). Novel. In English

** ''Engineer Menni'' (1913). Novel.

** "A Martian Stranded on Earth" (1924). Poem.

See also

Two Events Celebrating the Life and Contribution of Alexander Bogdanov

hosted by the Centre for Systems Studies on 2–3 June 2021 *

List of dystopian literature

This is a list of notable works of dystopian literature. A dystopia is an unpleasant (typically repressive) society, often propagandized as being utopian. ''The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction'' states that dystopian works depict a negative vie ...

* 1908 in literature

This article contains information about the literary events and publications of 1908.

Events

*February 15 – The weekly boys' story paper ''The Magnet'' is first published in London, containing "The Making of Harry Wharton", the first serial ...

* Arkady Bogdanov

The ''Mars'' trilogy is a series of science fiction novels by Kim Stanley Robinson that chronicles the settlement and terraforming of the planet Mars through the personal and detailed viewpoints of a wide variety of characters spanning 187 years ...

, a character in K.S. Robinson's ''Mars Trilogy

The ''Mars'' trilogy is a series of science fiction novels by Kim Stanley Robinson that chronicles the settlement and terraforming of the planet Mars through the personal and detailed viewpoints of a wide variety of characters spanning 187 year ...

'', inspired by Aleksandr Bogdanov

Notes

Sources

* Cohen, Stephen F. 1980973

Year 973 ( CMLXXIII) was a common year starting on Wednesday of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Byzantine Empire

* Spring – The Byzantine army, led by General Melias ( Domestic of the Schools in the East), continues the op ...

''Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution: A Political Biography, 1888–1938''. Oxford University Press. . First published by Alfred A. Knopf in 1973. Published 1980 by Oxford University Press with corrections and a new introductionGoogle Books preview as of 20101006

* Rosenthal, Bernice Glatzer. 2002. ''New Myth, New World: From Nietzsche to Stalinism''. The Pennsylvania State University Press

Google Books preview as of 20101006

* Sochor, Zenovia. 1988. ''Revolution and Culture: The Bogdanov-Lenin Controversy''. Cornell University Press. * ''Socialist Standard''. 2007 April

106 (1232): 10. * Souvarine, Boris. 1939. ''Stalin: A Critical Survey of Bolshevism''. New York: Alliance Group Corporation; Longmans, Green, and Co. * Woods, Alan. 1999. ''Bolshevism: The Road to Revolution''. Wellred Publications.

Part Three: The Period of Reaction

Further reading

* Biggart, John; Georgii Gloveli; Avraham Yassour. 1998. ''Bogdanov and his Work. A guide to the published and unpublished works of Alexander A. Bogdanov (Malinovsky) 1873–1928'', Aldershot: Ashgate. * Biggart, John; Peter Dudley; Francis King (eds.). 1998. ''Alexander Bogdanov and the Origins of Systems Thinking in Russia''. Aldershot: Ashgate. * Brown, Stuart. 2002. ''Biographical Dictionary of Twentieth-Century Philosophers'', London: Routledge. * Dudley, Peter. 1996. ''Bogdanov's Tektology'' (1st Engl transl). Hull, UK: Centre for Systems Studies,University of Hull

The University of Hull is a public research university in Kingston upon Hull, a city in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England. It was founded in 1927 as University College Hull. The main university campus is located in Hull and is home to the Hu ...

.

* Dudley, Peter; Simona Pustylnik. 1995. ''Reading The Tektology: provisional findings, postulates and research directions''. Hull, UK: Centre for Systems Studies, University of Hull.

* Gorelick, George. 1983. Bogdanov's Tektology: Nature, Development and Influences. ''Studies in Soviet Thought'', 26:37–57.

* Jensen, Kenneth Martin. 1978. ''Beyond Marx and Mach: Aleksandr Bogdanov's Philosophy of Living Experience''. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

* Pustylnik, Simona. 1995. ''Biological Ideas of Bogdanov's Tektology''. Presented at the international conference, Origins of Organization Theory in Russia and the Soviet Union, University of East Anglia (Norwich), Jan. 8–11, 1995.

* M. E. Soboleva. 2007. ''A. Bogdanov und der philosophische Diskurs in Russland zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts. Zur Geschichte des russischen Positivismus'' 'The history of Russian positivism''. Hildesheim, Germany: Georg Olms Verlag. 278 pp.

*

External links

Alexander Bogdanov Archive at marxists.org

Biographic essay (English)

International Alexander Bogdanov Institute

(Russian)

Short biography and bibliography

in the

Virtual Laboratory The online project Virtual Laboratory. Essays and Resources on the Experimentalization of Life, 1830-1930, located at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, is dedicated to research in the history of the experimentalization of life. T ...

of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

The Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (German: Max-Planck-Institut für Wissenschaftsgeschichte) is a scientific research institute founded in March 1994. It is dedicated to addressing fundamental questions of the history of knowled ...

Red Hamlet

*

''Science in Russia and the Soviet Union'': ''A Short History''

Loren R. Graham (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993 – Russian technocratic influence of engineers, subsequent deaths, trials and imprisonments

John A. Mikes, prepared for the nternational Conference on Complex SystemsNew England Complex Systems Institute, September 21–27, 1997, in

Nashua, NH

Nashua () is a city in southern New Hampshire, United States. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 91,322, the second-largest in northern New England after nearby Manchester. It is one of two county seats of New Hampshire's most populou ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bogdanov, Alexander

1873 births

1928 deaths

Members of the Central Committee of the 3rd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

Members of the Central Committee of the 4th Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

Candidates of the Central Committee of the 5th Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

People from Sokółka

People from Sokolsky Uyezd

Old Bolsheviks

Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members

Soviet inventors

Soviet economists

Soviet hematologists

Soviet art critics

Narodnaya Volya

Art critics from the Russian Empire

Communists from the Russian Empire

Economists from the Russian Empire

Inventors from the Russian Empire

Philosophers from the Russian Empire

Physicians from the Russian Empire

Writers from the Russian Empire

Soviet people of Polish descent

Soviet philosophers

20th-century Russian philosophers

Russian systems scientists

Marxist theorists

National University of Kharkiv alumni

Academic staff of Moscow State University

Inventors killed by their own invention

20th-century deaths from tuberculosis

Tuberculosis deaths in the Soviet Union

Tuberculosis deaths in Russia