Black Death (label) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Black Death was a

Research from 2017 suggests plague first infected humans in Europe and Asia in the

Research from 2017 suggests plague first infected humans in Europe and Asia in the

In 1382, the physician to the Avignon Papacy, Raimundo Chalmel de Vinario (), observed the decreasing mortality rate of successive outbreaks of plague in 1347–1348, 1362, 1371 and 1382 in his treatise ''On Epidemics'' (). In the first outbreak, two thirds of the population contracted the illness and most patients died; in the next, half the population became ill but only some died; by the third, a tenth were affected and many survived; while by the fourth occurrence, only one in twenty people were sickened and most of them survived. By the 1380s in Europe, the plague predominantly affected children. Chalmel de Vinario recognised that bloodletting was ineffective (though he continued to prescribe bleeding for members of the Roman Curia, whom he disliked), and said that all true cases of plague were caused by medical astrology, astrological factors and were incurable; he was never able to effect a cure.

The populations of some Italian cities, notably Florence, did not regain their pre-14th century size until the 19th century. Italian chronicler Agnolo di Tura recorded his experience from Siena, where plague arrived in May 1348:

The most widely accepted estimate for the Middle East, including Iraq, Iran, and Syria, during this time, is for a death toll of about a third of the population. The Black Death killed about 40% of Egypt's population. In Cairo, with a population numbering as many as 600,000, and possibly the largest city west of China, between one third and 40% of the inhabitants died within eight months. By the 18th century, the population of Cairo was halved from its numbers in 1347.

In 1382, the physician to the Avignon Papacy, Raimundo Chalmel de Vinario (), observed the decreasing mortality rate of successive outbreaks of plague in 1347–1348, 1362, 1371 and 1382 in his treatise ''On Epidemics'' (). In the first outbreak, two thirds of the population contracted the illness and most patients died; in the next, half the population became ill but only some died; by the third, a tenth were affected and many survived; while by the fourth occurrence, only one in twenty people were sickened and most of them survived. By the 1380s in Europe, the plague predominantly affected children. Chalmel de Vinario recognised that bloodletting was ineffective (though he continued to prescribe bleeding for members of the Roman Curia, whom he disliked), and said that all true cases of plague were caused by medical astrology, astrological factors and were incurable; he was never able to effect a cure.

The populations of some Italian cities, notably Florence, did not regain their pre-14th century size until the 19th century. Italian chronicler Agnolo di Tura recorded his experience from Siena, where plague arrived in May 1348:

The most widely accepted estimate for the Middle East, including Iraq, Iran, and Syria, during this time, is for a death toll of about a third of the population. The Black Death killed about 40% of Egypt's population. In Cairo, with a population numbering as many as 600,000, and possibly the largest city west of China, between one third and 40% of the inhabitants died within eight months. By the 18th century, the population of Cairo was halved from its numbers in 1347.

Renewed religious fervor and fanaticism increased in the wake of the Black Death. Some Europeans targeted "various groups such as Persecution of Jews during the Black Death, Jews, friars, foreigners, beggars, pilgrims", lepers, and Romani people, Romani, blaming them for the crisis. Leprosy, Lepers, and others with skin diseases such as acne or psoriasis, were killed throughout Europe.

Because 14th-century healers and governments were at a loss to explain or stop the disease, Europeans turned to astrology, astrological forces, earthquakes and the well poisoning#Medieval accusations against Jews, poisoning of wells by Jews as possible reasons for outbreaks. Many believed the epidemic was a divine retribution, punishment by God for their sins, and could be relieved by winning God's forgiveness.

There were many attacks against Jewish communities.Black Death

Renewed religious fervor and fanaticism increased in the wake of the Black Death. Some Europeans targeted "various groups such as Persecution of Jews during the Black Death, Jews, friars, foreigners, beggars, pilgrims", lepers, and Romani people, Romani, blaming them for the crisis. Leprosy, Lepers, and others with skin diseases such as acne or psoriasis, were killed throughout Europe.

Because 14th-century healers and governments were at a loss to explain or stop the disease, Europeans turned to astrology, astrological forces, earthquakes and the well poisoning#Medieval accusations against Jews, poisoning of wells by Jews as possible reasons for outbreaks. Many believed the epidemic was a divine retribution, punishment by God for their sins, and could be relieved by winning God's forgiveness.

There were many attacks against Jewish communities.Black Death

, Jewishencyclopedia.com In the Strasbourg massacre of February 1349, about 2,000 Jews were murdered. In August 1349, the Jewish communities in Mainz and Cologne were annihilated. By 1351, 60 major and 150 smaller Jewish communities had been destroyed. During this period many Jews relocated to Kingdom of Poland (1025–1385), Poland, where they received a welcome from King Casimir III the Great, Casimir the Great.

The plague repeatedly returned to haunt Europe and the Mediterranean throughout the 14th to 17th centuries. According to Jean-Noël Biraben, the plague was present somewhere in Europe in every year between 1346 and 1671 (although some researchers have cautions about the uncritical use of Biraben's data). The second pandemic was particularly widespread in the following years: 1360–1363; 1374; 1400; 1438–1439; 1456–1457; 1464–1466; 1481–1485; 1500–1503; 1518–1531; 1544–1548; 1563–1566; 1573–1588; 1596–1599; 1602–1611; 1623–1640; 1644–1654; and 1664–1667. Subsequent outbreaks, though severe, marked the plague's retreat from most of Europe (18th century) and North Africa (19th century).

Historian George Sussman argued that the plague had not occurred in East Africa until the 20th century. However, other sources suggest that the second pandemic did indeed reach sub-Saharan Africa.

According to historian Geoffrey Parker (historian), Geoffrey Parker, "France alone lost almost a million people to the plague in the epidemic of 1628–31." In the first half of the 17th century, a plague killed some 1.7 million people in Italy. More than 1.25 million deaths resulted from the extreme incidence of plague in 17th-century Habsburg Spain, Spain.

The Black Death ravaged much of the Muslim world, Islamic world. Plague could be found in the Islamic world almost every year between 1500 and 1850. Sometimes the outbreaks affected small areas, while other outbreaks affected multiple regions. Plague repeatedly struck the cities of North Africa. Algiers lost 30,000–50,000 inhabitants to it in 1620–1621, and again in 1654–1657, 1665, 1691, and 1740–1742. Cairo suffered more than fifty plague epidemics within 150 years from the plague's first appearance, with the final outbreak of the second pandemic there in the 1840s. Plague remained a major event in Ottoman Empire, Ottoman society until the second quarter of the 19th century. Between 1701 and 1750, thirty-seven larger and smaller epidemics were recorded in

The plague repeatedly returned to haunt Europe and the Mediterranean throughout the 14th to 17th centuries. According to Jean-Noël Biraben, the plague was present somewhere in Europe in every year between 1346 and 1671 (although some researchers have cautions about the uncritical use of Biraben's data). The second pandemic was particularly widespread in the following years: 1360–1363; 1374; 1400; 1438–1439; 1456–1457; 1464–1466; 1481–1485; 1500–1503; 1518–1531; 1544–1548; 1563–1566; 1573–1588; 1596–1599; 1602–1611; 1623–1640; 1644–1654; and 1664–1667. Subsequent outbreaks, though severe, marked the plague's retreat from most of Europe (18th century) and North Africa (19th century).

Historian George Sussman argued that the plague had not occurred in East Africa until the 20th century. However, other sources suggest that the second pandemic did indeed reach sub-Saharan Africa.

According to historian Geoffrey Parker (historian), Geoffrey Parker, "France alone lost almost a million people to the plague in the epidemic of 1628–31." In the first half of the 17th century, a plague killed some 1.7 million people in Italy. More than 1.25 million deaths resulted from the extreme incidence of plague in 17th-century Habsburg Spain, Spain.

The Black Death ravaged much of the Muslim world, Islamic world. Plague could be found in the Islamic world almost every year between 1500 and 1850. Sometimes the outbreaks affected small areas, while other outbreaks affected multiple regions. Plague repeatedly struck the cities of North Africa. Algiers lost 30,000–50,000 inhabitants to it in 1620–1621, and again in 1654–1657, 1665, 1691, and 1740–1742. Cairo suffered more than fifty plague epidemics within 150 years from the plague's first appearance, with the final outbreak of the second pandemic there in the 1840s. Plague remained a major event in Ottoman Empire, Ottoman society until the second quarter of the 19th century. Between 1701 and 1750, thirty-seven larger and smaller epidemics were recorded in

The third plague pandemic (1855–1960) started in China in the mid-19th century, spreading to all inhabited continents and killing 10 million people in India alone. The investigation of the pathogen that caused the 19th-century plague was begun by teams of scientists who visited Hong Kong in 1894, among whom was the French-Swiss bacteriologist

The third plague pandemic (1855–1960) started in China in the mid-19th century, spreading to all inhabited continents and killing 10 million people in India alone. The investigation of the pathogen that caused the 19th-century plague was begun by teams of scientists who visited Hong Kong in 1894, among whom was the French-Swiss bacteriologist

Project Gutenberg

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * 1st editions 1969. *

Black Death

at BBC {{Ireland topics Black Death, Plague pandemics 1340s 1350s Eurasian history History of medieval medicine Medieval health disasters Second plague pandemic Causes of death

bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of Plague (disease), plague caused by the Bacteria, bacterium ''Yersinia pestis''. One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and ...

pandemic

A pandemic ( ) is an epidemic of an infectious disease that has a sudden increase in cases and spreads across a large region, for instance multiple continents or worldwide, affecting a substantial number of individuals. Widespread endemic (epi ...

that occurred in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. The disease is caused by the bacterium

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among the ...

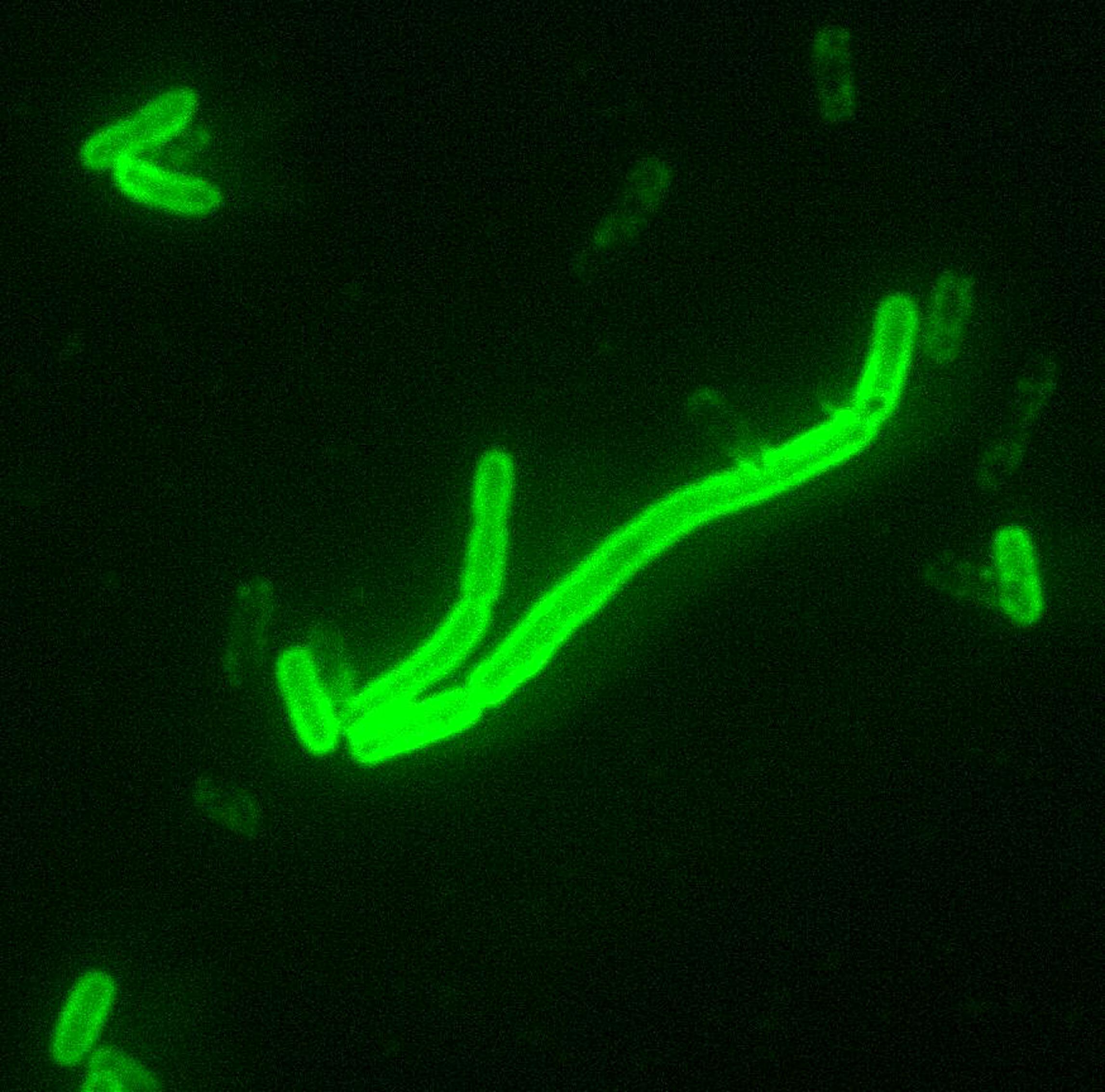

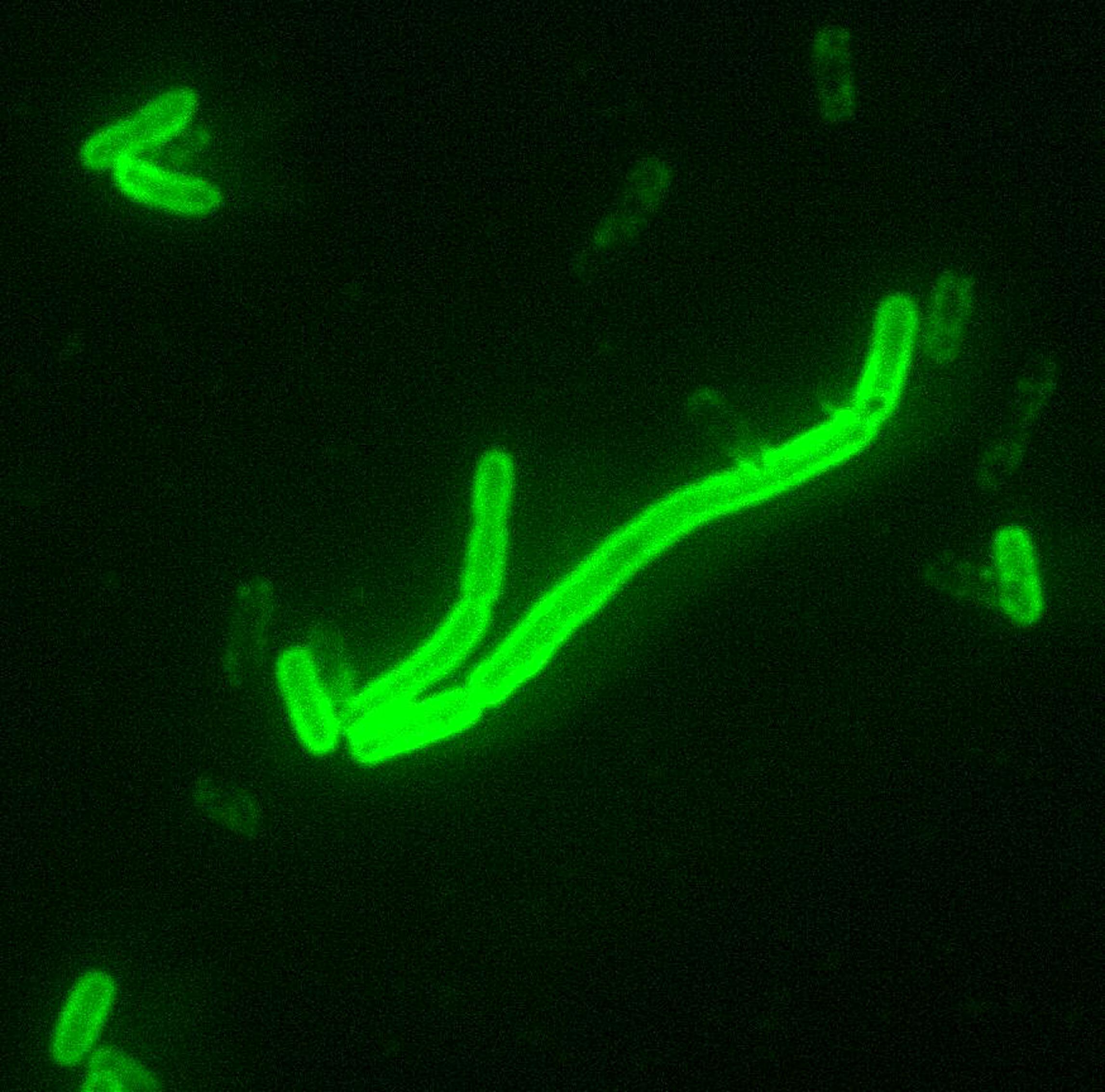

''Yersinia pestis

''Yersinia pestis'' (''Y. pestis''; formerly ''Pasteurella pestis'') is a Gram-negative bacteria, gram-negative, non-motile bacteria, non-motile, coccobacillus Bacteria, bacterium without Endospore, spores. It is related to pathogens ''Yer ...

'' and spread by fleas

Flea, the common name for the order Siphonaptera, includes 2,500 species of small flightless insects that live as external parasites of mammals and birds. Fleas live by ingesting the blood of their hosts. Adult fleas grow to about long, ar ...

and through the air. One of the most significant events in European history, the Black Death had far-reaching population, economic, and cultural impacts. It was the beginning of the second plague pandemic

The second plague pandemic was a major series of epidemics of Plague (disease), plague that started with the Black Death, which reached medieval Europe in 1346 and killed up to half of the population of Eurasia in the next four years. It followed ...

. The plague created religious, social and economic upheavals, with profound effects on the course of European history.

The origin of the Black Death is disputed. Genetic analysis suggests ''Yersinia pestis'' bacteria evolved approximately 7,000 years ago, at the beginning of the Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

, with flea-mediated strains emerging around 3,800 years ago during the late Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

. The immediate territorial origins of the Black Death and its outbreak remain unclear, with some evidence pointing towards Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

, China, the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

, and Europe. The pandemic was reportedly first introduced to Europe during the siege of the Genoese trading port of Kaffa in Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

by the Golden Horde

The Golden Horde, self-designated as ''Ulug Ulus'' ( in Turkic) was originally a Mongols, Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the division of ...

army of Jani Beg

Jani Beg ( Persian: جانی بیگ, Turki/ Kypchak: جانی بک; died 1357), also known as Janibek Khan, was Khan of the Golden Horde from 1342 until his death in 1357. He succeeded his father Öz Beg Khan.

Reign

With the support of his mo ...

in 1347. From Crimea, it was most likely carried by fleas

Flea, the common name for the order Siphonaptera, includes 2,500 species of small flightless insects that live as external parasites of mammals and birds. Fleas live by ingesting the blood of their hosts. Adult fleas grow to about long, ar ...

living on the black rat

The black rat (''Rattus rattus''), also known as the roof rat, ship rat, or house rat, is a common long-tailed rodent of the stereotypical rat genus ''Rattus'', in the subfamily Murinae. It likely originated in the Indian subcontinent, but is n ...

s that travelled on Genoese

Genoese, Genovese, or Genoan may refer to:

* a person from modern Genoa

* a person from the Republic of Genoa (–1805), a former state in Liguria

* Genoese dialect, a dialect of the Ligurian language

* Ligurian language, a Romance language of whi ...

ships, spreading through the Mediterranean Basin and reaching North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

, West Asia

West Asia (also called Western Asia or Southwest Asia) is the westernmost region of Asia. As defined by most academics, UN bodies and other institutions, the subregion consists of Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula, Iran, Mesopotamia, the Armenian ...

, and the rest of Europe via Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

, Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

, and the Italian Peninsula. There is evidence that once it came ashore, the Black Death mainly spread from person-to-person as pneumonic plague

Pneumonic plague is a severe lung infection caused by the bacterium '' Yersinia pestis''. Symptoms include fever, headache, shortness of breath, chest pain, and coughing. They typically start about three to seven days after exposure. It is o ...

, thus explaining the quick inland spread of the epidemic, which was faster than would be expected if the primary vector

Vector most often refers to:

* Euclidean vector, a quantity with a magnitude and a direction

* Disease vector, an agent that carries and transmits an infectious pathogen into another living organism

Vector may also refer to:

Mathematics a ...

was rat flea

A rat flea is a parasite of rats.

There are at least four species:

* Oriental rat flea (''Xenopsylla cheopis''), also known as the tropical rat flea, the primary vector for bubonic plague

* Northern rat flea (''Nosopsyllus fasciatus''). According ...

s causing bubonic plague. In 2022, it was discovered that there was a sudden surge of deaths in what is today Kyrgyzstan from the Black Death in the late 1330s; when combined with genetic evidence, this implies that the initial spread may have been unrelated to the 14th century Mongol conquests

The Mongol invasions and conquests took place during the 13th and 14th centuries, creating history's largest contiguous empire, the Mongol Empire (1206–1368), which by 1260 covered large parts of Eurasia. Historians regard the Mongol devastati ...

previously postulated as the cause.

The Black Death was the second great natural disaster to strike Europe during the Late Middle Ages

The late Middle Ages or late medieval period was the Periodization, period of History of Europe, European history lasting from 1300 to 1500 AD. The late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period ( ...

(the first one being the Great Famine of 1315–1317

The Great Famine of 1315–1317 (occasionally dated 1315–1322) was the first of a series of large-scale crises that struck parts of Europe early in the 14th century. Most of Europe (extending east to Poland and south to the Alps) was affected ...

) and is estimated to have killed 30% to 60% of the European population, as well as approximately 33% of the population of the Middle East. There were further outbreaks throughout the Late Middle Ages and, also due to other contributing factors (the crisis of the late Middle Ages), the European population did not regain its 14th century level until the 16th century. Outbreaks of the plague recurred around the world until the early 19th century.

Names

European writers contemporary with the plague described the disease inLatin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

as or ; ; . In English prior to the 18th century, the event was called the "pestilence" or "great pestilence", "the plague" or the "great death". Subsequent to the pandemic "the ''furste moreyn''" (first murrain

The word "murrain" (like an archaic use of the word "distemper") is an antiquated term covering various infectious diseases affecting cattle and sheep. The word originates from Middle English ''moreine'' or ''moryne'', in parallel to Late Latin ...

) or "first pestilence" was applied, to distinguish the mid-14th century phenomenon from other infectious diseases and epidemics of plague.

The 1347 pandemic plague was not referred to specifically as "black," at the time, in any European language. The expression "black death" had occasionally been applied to other fatal or dangerous diseases. In English, "Black death" was not used to describe this plague pandemic, however, until the 1750s; the term is first attested in 1755, where it translated .

This expression — as a proper name for the pandemic — had been popularized by Swedish and Danish chroniclers in the 15th and early 16th centuries, and in the 16th and 17th centuries, it was transferred to other languages as a calque

In linguistics, a calque () or loan translation is a word or phrase borrowed from another language by literal word-for-word or root-for-root translation. When used as a verb, "to calque" means to borrow a word or phrase from another language ...

: , , and . Previously, most European languages had named the pandemic a variant or calque of the .

The phrase 'black death' – describing Death

Death is the end of life; the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain a living organism. Death eventually and inevitably occurs in all organisms. The remains of a former organism normally begin to decompose sh ...

as black – is very old. Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

used it in the Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; ) is one of two major epics of ancient Greek literature attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest surviving works of literature and remains popular with modern audiences. Like the ''Iliad'', the ''Odyssey'' is divi ...

to describe the monstrous Scylla

In Greek mythology, Scylla ( ; , ) is a legendary, man-eating monster that lives on one side of a narrow channel of water, opposite her counterpart, the sea-swallowing monster Charybdis. The two sides of the strait are within an arrow's range o ...

, with her mouths "full of black Death" (). Seneca the Younger

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger ( ; AD 65), usually known mononymously as Seneca, was a Stoicism, Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome, a statesman, a dramatist, and in one work, a satirist, from the post-Augustan age of Latin literature.

Seneca ...

may have been the first to describe an epidemic as 'black death', () but only in reference to the acute lethality and dark prognosis

Prognosis ( Greek: πρόγνωσις "fore-knowing, foreseeing"; : prognoses) is a medical term for predicting the likelihood or expected development of a disease, including whether the signs and symptoms will improve or worsen (and how quickly) ...

of disease. The 12th–13th century French physician Gilles de Corbeil

Gilles de Corbeil (Latin: ''Egidius de Corbolio'' or ''Egidius Corboliensis''; also ''Aegidius'') was a French royal physician, teacher, and poet. He was born in approximately 1140 in Corbeil and died in the first quarter of the 13th century. He ...

had already used to refer to a "pestilential fever" () in his work ''On the Signs and Symptoms of Diseases'' (). The phrase , was used in 1350 by Simon de Covino (or Couvin), a Belgian astronomer, in his poem "On the Judgement of the Sun at a Feast of Saturn" (), which attributes the plague to an astrological conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn. His use of the phrase is not connected unambiguously with the plague pandemic of 1347 and appears to refer to the fatal outcome of disease.

The historian Elizabeth Penrose, writing under the pen-name "Mrs Markham", described the 14th-century outbreak as the "black death" in 1823. The historian Cardinal Francis Aidan Gasquet

Francis Aidan Cardinal Gasquet (born Francis Neil Gasquet; 5 October 1846 – 5 April 1929) was an English Benedictine monk and historical scholar. He controversially challenged what he regarded as the anti-Catholic narrative of the English h ...

wrote about the Great Pestilence in 1893 and suggested that it had been "some form of the ordinary Eastern or bubonic plague". In 1908, Gasquet said use of the name for the 14th-century epidemic first appeared in a 1631 book on Danish history by J. I. Pontanus: "Commonly and from its effects, they called it the black death" ().

Previous plague epidemics

Research from 2017 suggests plague first infected humans in Europe and Asia in the

Research from 2017 suggests plague first infected humans in Europe and Asia in the Late Neolithic

In the Near Eastern archaeology, archaeology of Southwest Asia, the Late Neolithic, also known as the Ceramic Neolithic or Pottery Neolithic, is the final part of the Neolithic period, following on from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic and preceding th ...

-Early Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

. Research in 2018 found evidence of ''Yersinia pestis

''Yersinia pestis'' (''Y. pestis''; formerly ''Pasteurella pestis'') is a Gram-negative bacteria, gram-negative, non-motile bacteria, non-motile, coccobacillus Bacteria, bacterium without Endospore, spores. It is related to pathogens ''Yer ...

'' in an ancient Swedish tomb, which may have been associated with the "Neolithic decline

The Neolithic decline was a rapid collapse in populations between about 3450 and 3000 BCE during the Neolithic period in western Eurasia. The specific causes of that broad population decline are still debated. While heavily populated settlements w ...

" around 3000 BCE, in which European populations fell significantly. This ''Y. pestis'' may have been different from more modern types, with bubonic plague transmissible by fleas first known from Bronze Age remains near Samara

Samara, formerly known as Kuybyshev (1935–1991), is the largest city and administrative centre of Samara Oblast in Russia. The city is located at the confluence of the Volga and the Samara (Volga), Samara rivers, with a population of over 1.14 ...

.

The symptoms of bubonic plague are first attested in a fragment

Fragment(s) may refer to:

Computing and logic

* Fragment (computer graphics), all the data necessary to generate a pixel in the frame buffer

* Fragment (logic), a syntactically restricted subset of a logical language

* URI fragment, the compone ...

of Rufus of Ephesus

Rufus of Ephesus (, fl. late 1st and early 2nd centuries AD) was a Greek physician and author who wrote treatises on dietetics, pathology, anatomy, gynaecology, and patient care. He was an admirer of Hippocrates, although he at times critici ...

preserved by Oribasius

Oribasius or Oreibasius (; c. 320 – 403) was a Greek medical writer and the personal physician of the Roman emperor Julian. He studied at Alexandria under physician Zeno of Cyprus before joining Julian's retinue. He was involved in Julian's ...

; these ancient medical authorities suggest bubonic plague had appeared in the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

before the reign of Trajan

Trajan ( ; born Marcus Ulpius Traianus, 18 September 53) was a Roman emperor from AD 98 to 117, remembered as the second of the Five Good Emperors of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty. He was a philanthropic ruler and a successful soldier ...

, six centuries before arriving at Pelusium

Pelusium (Ancient Egyptian: ; /, romanized: , or , romanized: ; ; ; ; ) was an important city in the eastern extremes of Egypt's Nile Delta, to the southeast of the modern Port Said. It became a Roman provincial capital and Metropolitan arc ...

in the reign of Justinian I

Justinian I (, ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was Roman emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign was marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovatio imperii'', or "restoration of the Empire". This ambition was ...

. In 2013, researchers confirmed earlier speculation that the cause of the Plague of Justinian

The plague of Justinian or Justinianic plague (AD 541–549) was an epidemic of Plague (disease), plague that afflicted the entire Mediterranean basin, Mediterranean Basin, Europe, and the Near East, especially the Sasanian Empire and the Byza ...

(541–549 CE, with recurrences until 750) was ''Y''. ''pestis''. This is known as the first plague pandemic

The first plague pandemic was the first historically recorded Old World pandemic of plague, the contagious disease caused by the bacterium '' Yersinia pestis''. Also called the early medieval pandemic, it began with the Plague of Justinian in 5 ...

. In 610, the Chinese physician Chao Yuanfang described a "malignant bubo" "coming in abruptly with high fever together with the appearance of a bundle of nodes beneath the tissue." The Chinese physician Sun Simo who died in 652 also mentioned a "malignant bubo" and plague that was common in Lingnan

Lingnan (; ) is a geographic area referring to the lands in the south of the Nanling Mountains. The region covers the modern China, Chinese subdivisions of Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan, Hong Kong & Macau and Northern Vietnam.

Background

The ar ...

(Guangzhou

Guangzhou, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Canton or Kwangchow, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Guangdong Provinces of China, province in South China, southern China. Located on the Pearl River about nor ...

). Ole Jørgen Benedictow believes that this indicates it was an offshoot of the first plague pandemic which made its way eastward to Chinese territory by around 600.

14th-century plague

Causes

Early theory

A report by the Medical Faculty of Paris stated that a conjunction of planets had caused "a great pestilence in the air" (miasma theory

The miasma theory (also called the miasmic theory) is an abandoned medical theory that held that diseases—such as cholera, chlamydia, or plague—were caused by a ''miasma'' (, Ancient Greek for 'pollution'), a noxious form of "bad air", a ...

). Muslim religious scholars taught that the pandemic was a "martyrdom and mercy" from God, assuring the believer's place in paradise. For non-believers, it was a punishment. Some Muslim doctors cautioned against trying to prevent or treat a disease sent by God. Others adopted preventive measures and treatments for plague used by Europeans. These Muslim doctors also depended on the writings of the ancient Greeks.

Predominant modern theory

Due toclimate change in Asia

Climate change is particularly important in Asia, as the continent accounts for the majority of the human population. Warming since the 20th century is increasing the threat of heatwaves across the entire continent. Heatwaves lead to increased mor ...

, rodents began to flee the dried-out grasslands to more populated areas, spreading the disease. The plague disease, caused by the bacterium ''Yersinia pestis

''Yersinia pestis'' (''Y. pestis''; formerly ''Pasteurella pestis'') is a Gram-negative bacteria, gram-negative, non-motile bacteria, non-motile, coccobacillus Bacteria, bacterium without Endospore, spores. It is related to pathogens ''Yer ...

'', is enzootic

Enzootic describes the situation where a disease or pathogen is continuously present in at least one species of non-human animal in a particular region. It is the non-human equivalent of endemic.

In epizoology, an infection is said to be "''enzo ...

(commonly present) in populations of fleas carried by ground rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the Order (biology), order Rodentia ( ), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and Mandible, lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal specie ...

s, including marmot

Marmots are large ground squirrels in the genus ''Marmota'', with 15 species living in Asia, Europe, and North America. These herbivores are active during the summer, when they can often be found in groups, but are not seen during the winter, w ...

s, in various areas, including Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

, Kurdistan

Kurdistan (, ; ), or Greater Kurdistan, is a roughly defined geo- cultural region in West Asia wherein the Kurds form a prominent majority population and the Kurdish culture, languages, and national identity have historically been based. G ...

, West Asia

West Asia (also called Western Asia or Southwest Asia) is the westernmost region of Asia. As defined by most academics, UN bodies and other institutions, the subregion consists of Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula, Iran, Mesopotamia, the Armenian ...

, North India

North India is a geographical region, loosely defined as a cultural region comprising the northern part of India (or historically, the Indian subcontinent) wherein Indo-Aryans (speaking Indo-Aryan languages) form the prominent majority populati ...

, Uganda

Uganda, officially the Republic of Uganda, is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the ...

, and the western United States.

''Y. pestis'' was discovered by Alexandre Yersin

Alexandre Émile John Yersin (22 September 1863 – 1 March 1943) was a Swiss- French physician and bacteriologist. He is remembered as the co-discoverer (1894) of the bacillus responsible for the bubonic plague or pest, which was later named in ...

, a pupil of Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist, pharmacist, and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, Fermentation, microbial fermentation, and pasteurization, the la ...

, during an epidemic of bubonic plague in Hong Kong in 1894; Yersin also proved this bacterium was present in rodents and suggested the rat was the main vehicle of transmission. The mechanism by which ''Y. pestis'' is usually transmitted was established in 1898 by Paul-Louis Simond

Paul-Louis Simond (30 July 1858 – 3 March 1947) was a French physician, chief medical officer and biologist whose major contribution to science was his demonstration that the intermediates in the transmission of bubonic plague from rats to ...

and was found to involve the bites of fleas whose midgut

The midgut is the portion of the human embryo from which almost all of the small intestine and approximately half of the large intestine develop. After it bends around the superior mesenteric artery, it is called the "midgut loop". It comprises ...

s had become obstructed by replicating ''Y. pestis'' several days after feeding on an infected host. This blockage starves the fleas, drives them to aggressive feeding behaviour, and causes them to try to clear the blockage via regurgitation, resulting in thousands of plague bacteria flushing into the feeding site and infecting the host. The bubonic plague mechanism was also dependent on two populations of rodents: one resistant to the disease, which act as host

A host is a person responsible for guests at an event or for providing hospitality during it.

Host may also refer to:

Places

* Host, Pennsylvania, a village in Berks County

* Host Island, in the Wilhelm Archipelago, Antarctica

People

* ...

s, keeping the disease endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

, and a second that lacks resistance. When the second population dies, the fleas move on to other hosts, including people, thus creating a human epidemic

An epidemic (from Greek ἐπί ''epi'' "upon or above" and δῆμος ''demos'' "people") is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of hosts in a given population within a short period of time. For example, in meningococcal infection ...

.

DNA evidence

Definitive confirmation of the role of ''Y. pestis'' arrived in 2010 with a publication in ''PLOS Pathogens

''PLOS Pathogens'' is a peer-reviewed open-access medical journal. All content in ''PLOS Pathogens'' is published under the Creative Commons "by-attribution" license.

''PLOS Pathogens'' began operation in September 2005. It was the fifth journal o ...

'' by Haensch et al. They assessed the presence of DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

/RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyrib ...

with polymerase chain reaction

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a method widely used to make millions to billions of copies of a specific DNA sample rapidly, allowing scientists to amplify a very small sample of DNA (or a part of it) sufficiently to enable detailed st ...

(PCR) techniques for ''Y. pestis'' from the tooth socket

Dental alveoli (singular ''alveolus'') are sockets in the jaws in which the roots of teeth are held in the alveolar process with the periodontal ligament. The lay term for dental alveoli is tooth sockets. A joint that connects the roots of the t ...

s in human skeletons from mass graves in northern, central and southern Europe that were associated archaeologically with the Black Death and subsequent resurgences. The authors concluded that this new research, together with prior analyses from the south of France and Germany, "ends the debate about the cause of the Black Death, and unambiguously demonstrates that ''Y. pestis'' was the causative agent

In biology, a pathogen (, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of"), in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ.

The term ...

of the epidemic plague that devastated Europe during the Middle Ages". In 2011 these results were further confirmed with genetic evidence derived from Black Death victims in the East Smithfield

East Smithfield is a small locality in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, east London, and also a short street, a part of the A1203 road.

Once broader in scope, the name came to apply to the part of the ancient parish of St Botolph without ...

burial site in England. Schuenemann et al. concluded in 2011 "that the Black Death in medieval Europe was caused by a variant of ''Y. pestis'' that may no longer exist".

Later in 2011, Bos

''Bos'' (from Latin '' bōs'': cow, ox, bull) is a genus of bovines, which includes, among others, wild and domestic cattle.

''Bos'' is often divided into four subgenera: ''Bos'', ''Bibos'', ''Novibos'', and ''Poephagus'', but including t ...

et al. reported in ''Nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

'' the first draft genome of ''Y. pestis'' from plague victims from the same East Smithfield cemetery and indicated that the strain that caused the Black Death is ancestral to most modern strains of ''Y. pestis''.

Later genomic papers have further confirmed the phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics () is the study of the evolutionary history of life using observable characteristics of organisms (or genes), which is known as phylogenetic inference. It infers the relationship among organisms based on empirical dat ...

placement of the ''Y. pestis'' strain responsible for the Black Death as both the ancestor of later plague epidemics—including the third plague pandemic

The third plague pandemic was a major bubonic plague pandemic that began in Yunnan, China, in 1855. This episode of bubonic plague spread to all inhabited continents, and ultimately led to more than 12 million deaths in India and China (and perh ...

—and the descendant of the strain responsible for the Plague of Justinian

The plague of Justinian or Justinianic plague (AD 541–549) was an epidemic of Plague (disease), plague that afflicted the entire Mediterranean basin, Mediterranean Basin, Europe, and the Near East, especially the Sasanian Empire and the Byza ...

. In addition, plague genomes from prehistory have been recovered.

DNA taken from 25 skeletons from 14th-century London showed that plague is a strain of ''Y. pestis'' almost identical to that which hit Madagascar in 2013. Further DNA evidence also proves the role of ''Y. pestis'' and traces the source to the Tian Shan

The Tian Shan, also known as the Tengri Tagh or Tengir-Too, meaning the "Mountains of God/Heaven", is a large system of mountain ranges in Central Asia. The highest peak is Jengish Chokusu at high and located in Kyrgyzstan. Its lowest point is ...

mountains in Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan, officially the Kyrgyz Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Asia lying in the Tian Shan and Pamir Mountains, Pamir mountain ranges. Bishkek is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Kyrgyzstan, largest city. Kyrgyz ...

.

Alternative explanations

Researchers are hampered by a lack of reliable statistics from this period. Most work has been done on the spread of the disease in England, where estimates of overall population at the start of the plague vary by over 100%, as no census was undertaken in England between the time of publication of theDomesday Book

Domesday Book ( ; the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book") is a manuscript record of the Great Survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 at the behest of William the Conqueror. The manuscript was originally known by ...

of 1086 and the poll tax

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources. ''Poll'' is an archaic term for "head" or "top of the head". The sen ...

of the year 1377. Estimates of plague victims are usually extrapolate

In mathematics, extrapolation is a type of estimation, beyond the original observation range, of the value of a variable on the basis of its relationship with another variable. It is similar to interpolation, which produces estimates between know ...

d from figures for the clergy.

Mathematical modelling

A mathematical model is an abstract description of a concrete system using mathematical concepts and language. The process of developing a mathematical model is termed ''mathematical modeling''. Mathematical models are used in applied mathemati ...

is used to match the spreading patterns and the means of transmission

Transmission or transmit may refer to:

Science and technology

* Power transmission

** Electric power transmission

** Transmission (mechanical device), technology that allows controlled application of power

*** Automatic transmission

*** Manual tra ...

. In 2018 researchers suggested an alternative model in which ''"the disease was spread from human fleas and body lice to other people".'' The second model claims to better fit the trends of the plague's death toll, as the rat-flea-human hypothesis would have produced a delayed but very high spike in deaths, contradicting historical death data. The Oriental rat flea has poor survival in cooler climates and reevaluation suggests the humean flea

Humeanism refers to the philosophy of David Hume and to the tradition of thought inspired by him. Hume was an influential eighteenth century Scottish philosopher well known for his empirical approach, which he applied to various fields in philosop ...

was the principal vector of plague epidemics in Northern Europe.

Lars Walløe

Lars Walløe (born 20 May 1938) is a Norwegian academic, chemist, physiologist, and scientific adviser to the Norwegian government. He was the head of the Norwegian Delegation to the Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission, ...

argued that these authors "take it for granted that Simond's infection model, black rat → rat flea → human, which was developed to explain the spread of plague in India, is the only way an epidemic of ''Yersinia pestis'' infection could spread". Similarly, Monica Green

Monica Green (born 1959) is a Swedish Social Democratic politician who was a member of the Riksdag from 1994 to 2018.

A controversial thought that she has expressed is that incest between adults should be legalised.Green, Monica -politiker: G� ...

has argued that greater attention is needed to the range of (especially non-commensal

Commensalism is a long-term biological interaction (symbiosis) in which members of one species gain benefits while those of the other species neither benefit nor are harmed. This is in contrast with mutualism, in which both organisms benefit f ...

) animals that might be involved in the transmission of plague.

Archaeologist Barney Sloane has argued that there is insufficient evidence of the extinction of numerous rats in the archaeological record of the medieval waterfront in London, and that the disease spread too quickly to support the thesis that ''Y. pestis'' was spread from fleas on rats; he argues that transmission must have been person to person. This theory is supported by research in 2018 which suggested transmission was more likely by body lice and flea

Flea, the common name for the order (biology), order Siphonaptera, includes 2,500 species of small flightless insects that live as external parasites of mammals and birds. Fleas live by hematophagy, ingesting the blood of their hosts. Adult f ...

s during the second plague pandemic

The second plague pandemic was a major series of epidemics of Plague (disease), plague that started with the Black Death, which reached medieval Europe in 1346 and killed up to half of the population of Eurasia in the next four years. It followed ...

.

Summary

Academic debate continues, but no single alternative explanation for the plague's spread has achieved widespread acceptance. Many scholars arguing for ''Y. pestis'' as the major agent of the pandemic suggest that its extent and symptoms can be explained by a combination of bubonic plague with other diseases, includingtyphus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposu ...

, smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

, and respiratory infection

Respiratory tract infections (RTIs) are infectious diseases involving the lower or upper respiratory tract. An infection of this type usually is further classified as an upper respiratory tract infection (URI or URTI) or a lower respiratory tra ...

s. In addition to the bubonic infection, others point to additional septicemic and pneumonic forms of plague, which lengthen the duration of outbreaks throughout the seasons and help account for its high mortality rate and additional recorded symptoms. In 2014, Public Health England

Public Health England (PHE) was an executive agency of the Department of Health and Social Care in England which began operating on 1 April 2013 to protect and improve health and wellbeing and reduce health inequalities. Its formation came as a ...

announced the results of an examination of 25 bodies exhumed in the Clerkenwell

Clerkenwell ( ) is an area of central London, England.

Clerkenwell was an Civil Parish#Ancient parishes, ancient parish from the medieval period onwards, and now forms the south-western part of the London Borough of Islington. The St James's C ...

area of London, as well as of wills registered in London during the period, which supported the pneumonic hypothesis. Currently, while osteoarcheologists have conclusively verified the presence of ''Y. pestis'' bacteria in burial sites across northern Europe through examination of bones and dental pulp

The pulp is the connective tissue, nerves, blood vessels, and odontoblasts that comprise the innermost layer of a tooth. The pulp's activity and signalling processes regulate its behaviour.

Anatomy

The pulp is the neurovascular bundle cen ...

, no other epidemic pathogen has been discovered to bolster the alternative explanations.

Transmission

Lack of hygiene

The importance ofhygiene

Hygiene is a set of practices performed to preserve health.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), "Hygiene refers to conditions and practices that help to maintain health and prevent the spread of diseases." Personal hygiene refer ...

was not recognized until the 19th century and the germ theory of disease

The germ theory of disease is the currently accepted scientific theory for many diseases. It states that microorganisms known as pathogens or "germs" can cause disease. These small organisms, which are too small to be seen without magnification, ...

. Until then streets were usually unhygienic, with live animals and human parasites facilitating the spread of transmissible disease

In medicine, public health, and biology, transmission is the passing of a pathogen causing communicable disease from an infected host individual or group to a particular individual or group, regardless of whether the other individual was previou ...

.

By the early 14th century, so much filth had collected inside urban Europe that French and Italian cities were naming streets after human waste. In medieval Paris, several street names were inspired by merde, the French word for "shit". There were rue Merdeux, rue Merdelet, rue Merdusson, rue des Merdons and rue Merdiere—as well as a rue du Pipi. Pigs, cattle, chickens, geese, goats and horses roamed the streets of medieval London and Paris.

Medieval homeowners were supposed to police their housefronts, including removing animal dung, but most urbanites were careless. William E. Cosner, a resident of the London suburb of Farringdon Without, received a complaint alleging that "men could not pass y his housefor the stink f. . . horse dung and horse piss." One irate Londoner complained that the runoff from the local slaughterhouse had made his garden "stinking and putrid", while another charged that the blood from slain animals flooded nearby streets and lanes, "making a foul corruption and abominable sight to all dwelling near." In much of medieval Europe, sanitation legislation consisted of an ordinance requiring homeowners to shout, "Look out below!" three times before dumping a full chamber pot into the street.

Early Christians considered bathing a temptation. With this danger in mind, St. Benedict

Benedict of Nursia (; ; 2 March 480 – 21 March 547), often known as Saint Benedict, was a Christian monk. He is famed in the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Lutheran Churches, the Anglican Communion, and Old Catholic Ch ...

declared, "To those who are well, and especially to the young, bathing shall seldom be permitted." St. Agnes

Agnes of Rome (21 January 304) is a virgin martyr, venerated as a saint in the Catholic Church, Oriental Orthodox Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church, as well as the Anglican Communion and Lutheran Churches. She is one of several virgin marty ...

took the injunction to heart and died without ever bathing.

Territorial origins

According to a team of medical geneticists led byMark Achtman

Mark Achtman is an emeritus Professor of Bacterial Population Genetics at Warwick Medical School, part of the University of Warwick in the UK.

Education

Achtman was educated at McGill University and graduated in 1963 (B. Sc. Hon. Bacteriology & ...

, ''Yersinia pestis'' "evolved in or near China" over 2,600 years ago. Later research by a team led by Galina Eroshenko placed its origins more specifically in the Tian Shan

The Tian Shan, also known as the Tengri Tagh or Tengir-Too, meaning the "Mountains of God/Heaven", is a large system of mountain ranges in Central Asia. The highest peak is Jengish Chokusu at high and located in Kyrgyzstan. Its lowest point is ...

mountains on the border between Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan, officially the Kyrgyz Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Asia lying in the Tian Shan and Pamir Mountains, Pamir mountain ranges. Bishkek is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Kyrgyzstan, largest city. Kyrgyz ...

and China. However more recent research notes that the previous sampling contained East Asian bias and that sampling since then has discovered strains of ''Y. pestis'' in the Caucasus region previously thought to be restricted to China. There is also no physical or specific textual evidence of the Black Death in 14th century China. As a result, China's place in the sequence of the plague's spread is still debated to this day. According to Charles Creighton, records of epidemics in 14th-century China suggest nothing more than typhus and major Chinese outbreaks of epidemic disease post-date the European epidemic by several years. The earliest Chinese descriptions of the bubonic plague do not appear until the 1640s.

Nestorian

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian ...

gravesites dating from 1338 to 1339 near Issyk-Kul

Issyk-Kul () or Ysyk-Köl (, ; ) is an endorheic saline lake in the western Tianshan Mountains in eastern Kyrgyzstan, just south of a dividing range separating Kyrgyzstan from Kazakhstan. It is the eighth-deepest lake in the world, the eleve ...

have inscriptions referring to plague, which has led some historians and epidemiology, epidemiologists to think they mark the outbreak of the epidemic; this is supported by recent direct findings of ''Y. pestis'' DNA in teeth samples from graves in the area with inscriptions referring to "pestilence" as the cause of death. Epidemics killed an estimated 25 million across Asia during the fifteen years before the Black Death reached Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

in 1347.

According to John Norris, evidence from Issyk-Kul indicates a small sporadic outbreak characteristic of transmission from rodents to humans with no wide-scale impact. According to Achtman, the dating of the plague suggests that it was not carried along the Silk Road, and its widespread appearance in that region probably postdates the European outbreak. Additionally, the Silk Road had already been heavily disrupted before the spread of the Black Death; Western and Middle Eastern traders found it difficult to trade on the Silk Road by 1325 and impossible by 1340, making its role in the spread of plague less likely. There are no records of the symptoms of the Black Death from Mongol sources or writings from travelers east of the Black Sea prior to the Crimean outbreak in 1346.

Others still favor an origin in China. The theory of Chinese origin implicates the Silk Road, the disease possibly spreading alongside Mongols, Mongol armies and traders, or possibly arriving via ship—however, this theory is still contested. It is speculated that rats aboard Zheng He's ships in the 15th century may have carried the plague to Southeast Asia, India, and Africa.

Research on the Delhi Sultanate and the Yuan dynasty shows no evidence of any serious epidemic in fourteenth-century India and no specific evidence of plague in 14th-century China, suggesting that the Black Death may not have reached these regions. Ole Benedictow argues that since the first clear reports of the Black Death come from Kaffa (city), Kaffa, the Black Death most likely originated in the nearby plague focus on the northwestern shore of the Caspian Sea.

Monica Green suggests that other parts of Eurasia outside the west do not contain the same evidence of the Black Death, because there were actually four strains of ''Yersinia pestis'' that became predominant in different parts of the world. Mongol records of illness such as food poisoning may have been referring to the Black Death. Another theory is that the plague originated near Europe and cycled through the Mediterranean, Northern Europe and Russia before making its way to China. Other historians, such as John Norris and Ole Benedictaw, believe the plague likely originated in Europe or the Middle East, and never reached China. Norris specifically argues for an origin in Kurdistan rather than Central Asia.

European outbreak

Plague was reportedly first introduced to Europe viaGenoese

Genoese, Genovese, or Genoan may refer to:

* a person from modern Genoa

* a person from the Republic of Genoa (–1805), a former state in Liguria

* Genoese dialect, a dialect of the Ligurian language

* Ligurian language, a Romance language of whi ...

traders from their port city of Feodosia, Kaffa in the Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

in 1347. During a Genoese–Mongol Wars, protracted siege of the city in 1345–1346, the Mongol Golden Horde

The Golden Horde, self-designated as ''Ulug Ulus'' ( in Turkic) was originally a Mongols, Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the division of ...

army of Jani Beg

Jani Beg ( Persian: جانی بیگ, Turki/ Kypchak: جانی بک; died 1357), also known as Janibek Khan, was Khan of the Golden Horde from 1342 until his death in 1357. He succeeded his father Öz Beg Khan.

Reign

With the support of his mo ...

—whose mainly Tatar confederation, Tatar troops were suffering from the disease—biological warfare, catapulted infected corpses over the city walls of Kaffa to infect the inhabitants, though it is also likely that infected rats travelled across the siege lines to spread the epidemic to the inhabitants. As the disease took hold, Genoese traders fled across the Black Sea to Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

, where the disease first arrived in Europe in summer 1347.

The epidemic there killed the 13-year-old son of the Byzantine Empire, Byzantine emperor, John VI Kantakouzenos, who wrote a description of the disease modelled on Thucydides's account of the 5th century BCE Plague of Athens, noting the spread of the Black Death by ship between maritime cities. Nicephorus Gregoras, while writing to Demetrios Kydones, described the rising death toll, the futility of medicine, and the panic of the citizens. The first outbreak in Constantinople lasted a year, but the disease recurred ten times before 1400.

Carried by twelve Genoese galleys, plague arrived by ship in Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

in October 1347; the disease spread rapidly all over the island. Galleys from Kaffa reached Genoa and Venice in January 1348, but it was the outbreak in Pisa a few weeks later that was the entry point into northern Italy. Towards the end of January, one of the galleys expelled from Italy arrived in Marseilles.

Black Death in Italy, From Italy, the disease spread northwest across Europe, Black Death in France, striking France, Black Death in Spain, Spain, Portugal, and Black Death in England, England by June 1348, then spreading east and north Black Death in Germany, through Germany, Scotland and Scandinavia from 1348 to 1350. It was introduced Black Death in Norway, into Norway in 1349 when a ship landed at Askøy, then spread to Bjørgvin (modern Bergen). Finally, it Black Death in Russia, spread to northern Russia in 1352 and reached Moscow in 1353. Plague was less common in parts of Europe with less-established trade relations, including the majority of the Basque Country (greater region), Basque Country, isolated parts of Belgium and Black Death in the Netherlands, the Netherlands, and isolated Alpine villages throughout the continent.

According to some epidemiologists, periods of unfavorable weather decimated plague-infected rodent populations, forcing their fleas onto alternative hosts, inducing plague outbreaks which often peaked in the hot summers of the Mediterranean and during the cool autumn months of the southern Baltic region. Among many other culprits of plague contagiousness, pre-existing malnutrition weakened the immune response, contributing to an immense decline in European population.

West Asian and North African outbreak

The disease struck various regions in the Middle East and North Africa during thepandemic

A pandemic ( ) is an epidemic of an infectious disease that has a sudden increase in cases and spreads across a large region, for instance multiple continents or worldwide, affecting a substantial number of individuals. Widespread endemic (epi ...

, leading to serious depopulation and permanent change in both economic and social structures.

By autumn 1347, plague had reached Alexandria in Egypt, transmitted by sea from Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

via a single merchant ship carrying slaves. By late summer 1348, it reached Cairo, capital of the Mamluk Sultanate, cultural center of the Muslim world, Islamic world, and the largest city in the Mediterranean Basin; the Bahri dynasty, Bahriyya child sultan an-Nasir Hasan fled and more than a third of the 600,000 residents died. The Nile was choked with corpses despite Cairo having a medieval hospital, the late 13th-century bimaristan of the Qalawun complex. The historian al-Maqrizi described the abundant work for grave-diggers and practitioners of Islamic funeral, funeral rites; plague recurred in Cairo more than fifty times over the following one and a half centuries.

During 1347, the disease travelled eastward to Gaza City, Gaza by April; by July it had reached Damascus, and in October plague had broken out in Aleppo. That year, in Syria (region), the territory of modern Lebanon, Syria, Israel, and Palestine (region), Palestine, the cities of Ascalon, Acre, Israel, Acre, Jerusalem, Sidon, and Homs were all infected. In 1348–1349, the disease reached Antioch. The city's residents fled to the north, but most of them ended up dying during the journey. Within two years, the plague had spread throughout the Islamic world, from Arabia across North Africa.

The pandemic spread westwards from Alexandria along the African coast, while in April 1348 Tunis was infected by ship from Sicily. Tunis was then under attack by an army from Morocco; this army dispersed in 1348 and brought the contagion with them to Morocco, whose epidemic may also have been seeded from the Islamic city of Almería in al-Andalus.

Mecca became infected in 1348 by pilgrims performing the Hajj. In 1351 or 1352, the Rasulid dynasty, Rasulid sultan of the Yemen, al-Mujahid Ali, was released from Mamluk captivity in Egypt and carried plague with him on his return home. During 1349, records show the city of Mosul suffered a massive epidemic, and the city of Baghdad experienced a second round of the disease.

Signs and symptoms

Bubonic plague

Symptoms of the plague include fever of , headaches, arthralgia, painful aching joints, nausea and vomiting, and a general feeling of malaise. Left untreated, 80% of victims die within eight days. Contemporary accounts of the pandemic are varied and often imprecise. The most commonly noted symptom was the appearance of buboes (or ''gavocciolos'') in the groin, neck and armpits, which oozed pus and bled when opened. Giovanni Boccaccio, Boccaccio's description: This was followed by acute fever and hematemesis, vomiting of blood. Most people died two to seven days after initial infection. Freckle-like spots and rashes, which may have been caused by pulicosis, flea-bites, were identified as another potential sign of plague.Pneumonic plague

Lodewijk Heyligen, whose master Cardinal Giovanni Colonna (cardinal, 1295–1348), Giovanni Colonna died of plague in 1348, noted a distinct form of the disease,pneumonic plague

Pneumonic plague is a severe lung infection caused by the bacterium '' Yersinia pestis''. Symptoms include fever, headache, shortness of breath, chest pain, and coughing. They typically start about three to seven days after exposure. It is o ...

, that infected the lungs and led to respiratory problems. Symptoms include fever, cough and hemoptysis, blood-tinged sputum. As the disease progresses, sputum becomes free-flowing and bright red. Pneumonic plague has a mortality rate of 90–95%.

Septicemic plague

Septicemic plague is the least common of the three forms, with an untreated mortality rate near 100%. Symptoms are high fevers and purple skin patches (purpura due to disseminated intravascular coagulation). In cases of pneumonic and particularly septicemic plague, the progress of the disease is so rapid that there would often be no time for the development of the enlarged lymph nodes that were noted as buboes.Consequences

Deaths

There are no exact figures for the death toll; the rate varied widely by locality. Urban centers with higher populations suffered longer periods of abnormal mortality. Some estimate that it may have killed between 75,000,000 and 200,000,000 people in Eurasia. A study published in 2022 of pollen samples across Europe from 1250 to 1450 was used to estimate changes in agricultural output before and after the Black Death. The authors found great variability in different regions, with evidence for high mortality in areas of Scandinavia, France, western Germany, Greece, and central Italy, but uninterrupted agricultural growth in central and eastern Europe, Iberia, and Ireland. The authors concluded that "the pandemic was immensely destructive in some areas, but in others it had a far lighter touch ... [the study methodology] invalidates histories of the Black Death that assume Y. pestis was uniformly prevalent, or nearly so, across Europe and that the pandemic had a devastating demographic impact everywhere." The Black Death killed, by various estimations, from 25 to 60% of Europe's population. Robert Gottfried writes that as early as 1351, "agents for Pope Clement VI calculated the number of dead in Christian Europe at 23,840,000. With a preplague population of about 75 million, Clement's figure accounts for mortality of 31%-a rate about midway between the 50% mortality estimated for East Anglia, Tuscany, and parts of Scandinavia, and the less-than-15% morbidity for Bohemia and Galicia. And it is unerringly close to Froissart's claim that "a third of the world died," a measurement probably drawn from St. John's figure of mortality from plague in the Book of Revelation, a favorite medieval source of information." Ole J. Benedictow proposes 60% mortality rate for Europe as a whole based on available data, with up to 80% based on poor nutritional conditions in the 14th century. According to medieval historian Philip Daileader, it is likely that over four years, 45–50% of the European population died of plague. The overwhelming number of deaths in Europe sometimes made mass burials necessary, and some sites had hundreds or thousands of bodies. The mass burial sites that have been excavated have allowed archaeologists to continue interpreting and defining the biological, sociological, historical, and anthropological implications of the Black Death. The mortality rate of the Black Death in the 14th century was far greater than the worst 20th-century outbreaks of ''Y. pestis'' plague, which occurred in India and killed as much as 3% of the population of certain cities. In 1348, the disease spread so rapidly that nearly a third of the European population perished before any physicians or government authorities had time to reflect upon its origins. In crowded cities, it was not uncommon for as much as 50% of the population to die. Half of Paris' population of 100,000 people died. In Italy, the population of Florence was reduced from between 110,000 and 120,000 inhabitants in 1338 to 50,000 in 1351. At least 60% of the population of Hamburg and Bremen perished, and a similar percentage of Londoners may have died from the disease as well, leaving a death toll of approximately 62,000 between 1346 and 1353. Florence's tax records suggest that 80% of the city's population died within four months in 1348. Before 1350, there were about 170,000 settlements in Germany, and this was reduced by nearly 40,000 by 1450. The disease bypassed some areas, with the most isolated areas being less vulnerable to contagious disease, contagion. Plague did not appear in French Flanders, Flanders until the turn of the 15th century, and the impact was less severe on the populations of County of Hainaut, Hainaut, Medieval Finland, Finland, northern Germany, and areas of Poland. Monks, nuns, and priests were especially hard-hit since they cared for people ill with the plague. The level of mortality in the rest of Eastern Europe was likely similar to that of Western Europe in the first outbreak, with descriptions suggesting a similar effect on Russian towns, and the cycles of plague in Russia being roughly equivalent. In 1382, the physician to the Avignon Papacy, Raimundo Chalmel de Vinario (), observed the decreasing mortality rate of successive outbreaks of plague in 1347–1348, 1362, 1371 and 1382 in his treatise ''On Epidemics'' (). In the first outbreak, two thirds of the population contracted the illness and most patients died; in the next, half the population became ill but only some died; by the third, a tenth were affected and many survived; while by the fourth occurrence, only one in twenty people were sickened and most of them survived. By the 1380s in Europe, the plague predominantly affected children. Chalmel de Vinario recognised that bloodletting was ineffective (though he continued to prescribe bleeding for members of the Roman Curia, whom he disliked), and said that all true cases of plague were caused by medical astrology, astrological factors and were incurable; he was never able to effect a cure.

The populations of some Italian cities, notably Florence, did not regain their pre-14th century size until the 19th century. Italian chronicler Agnolo di Tura recorded his experience from Siena, where plague arrived in May 1348:

The most widely accepted estimate for the Middle East, including Iraq, Iran, and Syria, during this time, is for a death toll of about a third of the population. The Black Death killed about 40% of Egypt's population. In Cairo, with a population numbering as many as 600,000, and possibly the largest city west of China, between one third and 40% of the inhabitants died within eight months. By the 18th century, the population of Cairo was halved from its numbers in 1347.

In 1382, the physician to the Avignon Papacy, Raimundo Chalmel de Vinario (), observed the decreasing mortality rate of successive outbreaks of plague in 1347–1348, 1362, 1371 and 1382 in his treatise ''On Epidemics'' (). In the first outbreak, two thirds of the population contracted the illness and most patients died; in the next, half the population became ill but only some died; by the third, a tenth were affected and many survived; while by the fourth occurrence, only one in twenty people were sickened and most of them survived. By the 1380s in Europe, the plague predominantly affected children. Chalmel de Vinario recognised that bloodletting was ineffective (though he continued to prescribe bleeding for members of the Roman Curia, whom he disliked), and said that all true cases of plague were caused by medical astrology, astrological factors and were incurable; he was never able to effect a cure.

The populations of some Italian cities, notably Florence, did not regain their pre-14th century size until the 19th century. Italian chronicler Agnolo di Tura recorded his experience from Siena, where plague arrived in May 1348:

The most widely accepted estimate for the Middle East, including Iraq, Iran, and Syria, during this time, is for a death toll of about a third of the population. The Black Death killed about 40% of Egypt's population. In Cairo, with a population numbering as many as 600,000, and possibly the largest city west of China, between one third and 40% of the inhabitants died within eight months. By the 18th century, the population of Cairo was halved from its numbers in 1347.

Economic

It has been suggested that the Black Death, like other outbreaks through history, disproportionately affected the poorest people and those already in worse physical condition than the wealthier citizens. But along with population decline from the pandemic, wages soared in response to a subsequent labour shortage. In some places rents collapsed (e.g., lettings "used to bring in £5, and now but £1.") However, many labourers, artisans, and craftsmen—those living from money-wages alone—suffered a reduction in real incomes owing to rampant inflation. Landowners were also pushed to substitute monetary rents for labour services in an effort to keep tenants. Taxes and tithes became difficult to collect, with living poor refusing to cover the share of the rich deceased, because many properties were empty and unfarmed, and because tax-collectors, where they could be employed, refused to go to plague spots. The trade disruptions in the Mongol Empire caused by the Black Death was one of the reasons for its collapse.Environmental

A study performed by Thomas Van Hoof of the Utrecht University suggests that the innumerable deaths brought on by the pandemic cooled the climate by freeing up land and triggering reforestation. This may have led to the Little Ice Age.Persecutions

Renewed religious fervor and fanaticism increased in the wake of the Black Death. Some Europeans targeted "various groups such as Persecution of Jews during the Black Death, Jews, friars, foreigners, beggars, pilgrims", lepers, and Romani people, Romani, blaming them for the crisis. Leprosy, Lepers, and others with skin diseases such as acne or psoriasis, were killed throughout Europe.

Because 14th-century healers and governments were at a loss to explain or stop the disease, Europeans turned to astrology, astrological forces, earthquakes and the well poisoning#Medieval accusations against Jews, poisoning of wells by Jews as possible reasons for outbreaks. Many believed the epidemic was a divine retribution, punishment by God for their sins, and could be relieved by winning God's forgiveness.

There were many attacks against Jewish communities.Black Death

Renewed religious fervor and fanaticism increased in the wake of the Black Death. Some Europeans targeted "various groups such as Persecution of Jews during the Black Death, Jews, friars, foreigners, beggars, pilgrims", lepers, and Romani people, Romani, blaming them for the crisis. Leprosy, Lepers, and others with skin diseases such as acne or psoriasis, were killed throughout Europe.