biochemical genetics on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Molecular biology is the branch of

In 1928, Fredrick Griffith, encountered a virulence property in pneumococcus bacteria, which was killing lab rats. According to Mendel, prevalent at that time, gene transfer could occur only from parent to daughter cells only. Griffith advanced another theory, stating that gene transfer occurring in member of same generation is known as horizontal gene transfer (HGT). This phenomenon is now referred to as genetic transformation.

Griffith addressed the ''Streptococcus pneumoniae'' bacteria, which had two different strains, one virulent and smooth and one avirulent and rough. The smooth strain had glistering appearance owing to the presence of a type of specific polysaccharide – a polymer of glucose and glucuronic acid capsule. Due to this polysaccharide layer of bacteria, a host's immune system cannot recognize the bacteria and it kills the host. The other, avirulent, rough strain lacks this polysaccharide capsule and has a dull, rough appearance.

Presence or absence of capsule in the strain, is known to be genetically determined. Smooth and rough strains occur in several different type such as S-I, S-II, S-III, etc. and R-I, R-II, R-III, etc. respectively. All this subtypes of S and R bacteria differ with each other in antigen type they produce.

In 1928, Fredrick Griffith, encountered a virulence property in pneumococcus bacteria, which was killing lab rats. According to Mendel, prevalent at that time, gene transfer could occur only from parent to daughter cells only. Griffith advanced another theory, stating that gene transfer occurring in member of same generation is known as horizontal gene transfer (HGT). This phenomenon is now referred to as genetic transformation.

Griffith addressed the ''Streptococcus pneumoniae'' bacteria, which had two different strains, one virulent and smooth and one avirulent and rough. The smooth strain had glistering appearance owing to the presence of a type of specific polysaccharide – a polymer of glucose and glucuronic acid capsule. Due to this polysaccharide layer of bacteria, a host's immune system cannot recognize the bacteria and it kills the host. The other, avirulent, rough strain lacks this polysaccharide capsule and has a dull, rough appearance.

Presence or absence of capsule in the strain, is known to be genetically determined. Smooth and rough strains occur in several different type such as S-I, S-II, S-III, etc. and R-I, R-II, R-III, etc. respectively. All this subtypes of S and R bacteria differ with each other in antigen type they produce.

Confirmation that DNA is the genetic material which is cause of infection came from Hershey and Chase experiment. They used ''E.coli'' and bacteriophage for the experiment. This experiment is also known as blender experiment, as kitchen blender was used as a major piece of apparatus. ''Alfred Hershey'' and ''Martha Chase'' demonstrated that the DNA injected by a phage particle into a bacterium contains all information required to synthesize progeny phage particles. They used radioactivity to tag the bacteriophage's protein coat with radioactive sulphur and DNA with radioactive phosphorus, into two different test tubes respectively. After mixing bacteriophage and ''E.coli'' into the test tube, the incubation period starts in which phage transforms the genetic material in the ''E.coli'' cells. Then the mixture is blended or agitated, which separates the phage from ''E.coli'' cells. The whole mixture is centrifuged and the pellet which contains ''E.coli'' cells was checked and the supernatant was discarded. The ''E.coli'' cells showed radioactive phosphorus, which indicated that the transformed material was DNA not the protein coat.

The transformed DNA gets attached to the DNA of ''E.coli'' and radioactivity is only seen onto the bacteriophage's DNA. This mutated DNA can be passed to the next generation and the theory of Transduction came into existence. Transduction is a process in which the bacterial DNA carry the fragment of bacteriophages and pass it on the next generation. This is also a type of horizontal gene transfer.

Confirmation that DNA is the genetic material which is cause of infection came from Hershey and Chase experiment. They used ''E.coli'' and bacteriophage for the experiment. This experiment is also known as blender experiment, as kitchen blender was used as a major piece of apparatus. ''Alfred Hershey'' and ''Martha Chase'' demonstrated that the DNA injected by a phage particle into a bacterium contains all information required to synthesize progeny phage particles. They used radioactivity to tag the bacteriophage's protein coat with radioactive sulphur and DNA with radioactive phosphorus, into two different test tubes respectively. After mixing bacteriophage and ''E.coli'' into the test tube, the incubation period starts in which phage transforms the genetic material in the ''E.coli'' cells. Then the mixture is blended or agitated, which separates the phage from ''E.coli'' cells. The whole mixture is centrifuged and the pellet which contains ''E.coli'' cells was checked and the supernatant was discarded. The ''E.coli'' cells showed radioactive phosphorus, which indicated that the transformed material was DNA not the protein coat.

The transformed DNA gets attached to the DNA of ''E.coli'' and radioactivity is only seen onto the bacteriophage's DNA. This mutated DNA can be passed to the next generation and the theory of Transduction came into existence. Transduction is a process in which the bacterial DNA carry the fragment of bacteriophages and pass it on the next generation. This is also a type of horizontal gene transfer.

The

The

A

A

biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditar ...

that seeks to understand the molecular

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bioch ...

basis of biological activity in and between cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery w ...

, including biomolecular

A biomolecule or biological molecule is a loosely used term for molecules present in organisms that are essential to one or more typically biological processes, such as cell division, morphogenesis, or development. Biomolecules include large ...

synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactions. The study of chemical and physical structure of biological macromolecules is known as molecular biology.

Molecular biology was first described as an approach focused on the underpinnings of biological phenomena - uncovering the structures of biological molecules as well as their interactions, and how these interactions explain observations of classical biology.

In 1945 the term molecular biology was used by physicist William Astbury. In 1953 Francis Crick, James Watson, Rosalind Franklin, and colleagues, working at Medical Research Council unit, Cavendish laboratory, Cambridge (now the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology

The Medical Research Council (MRC) Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB) is a research institute in Cambridge, England, involved in the revolution in molecular biology which occurred in the 1950–60s. Since then it has remained a major medical r ...

), made a double helix

A double is a look-alike or doppelgänger; one person or being that resembles another.

Double, The Double or Dubble may also refer to:

Film and television

* Double (filmmaking), someone who substitutes for the credited actor of a character

* ...

model of DNA which changed the entire research scenario. They proposed the DNA structure based on previous research done by Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins. This research then lead to finding DNA material in other microorganisms, plants and animals.

Molecular biology is not simply the study of biological molecules and their interactions; rather, it is also a collection of techniques developed since the field's genesis which have enabled scientists to learn about molecular processes. In this way it has both complemented and improved biochemistry

Biochemistry or biological chemistry is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology ...

and genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar worki ...

as methods (of understanding nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans ar ...

) that began before its advent. One notable technique which has revolutionized the field is the polymerase chain reaction

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a method widely used to rapidly make millions to billions of copies (complete or partial) of a specific DNA sample, allowing scientists to take a very small sample of DNA and amplify it (or a part of it) ...

(PCR), which was developed in 1983. PCR is a reaction which amplifies small quantities of DNA, and it is used in many applications across scientific disciplines.

The central dogma of molecular biology

The central dogma of molecular biology is an explanation of the flow of genetic information within a biological system. It is often stated as "DNA makes RNA, and RNA makes protein", although this is not its original meaning. It was first stated by ...

describes the process in which DNA is transcribed into RNA, which is then translated into protein.

Molecular biology also plays a critical role in the understanding of structures, functions, and internal controls within individual cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery w ...

, all of which can be used to efficiently target new drug

A drug is any chemical substance that causes a change in an organism's physiology or psychology when consumed. Drugs are typically distinguished from food and substances that provide nutritional support. Consumption of drugs can be via inhal ...

s, diagnose disease, and better understand cell physiology. Some clinical research and medical therapies arising from molecular biology are covered under gene therapy

Gene therapy is a medical field which focuses on the genetic modification of cells to produce a therapeutic effect or the treatment of disease by repairing or reconstructing defective genetic material. The first attempt at modifying human D ...

whereas the use of molecular biology or molecular cell biology in medicine is now referred to as molecular medicine

Molecular medicine is a broad field, where physical, chemical, biological, bioinformatics and medical techniques are used to describe molecular structures and mechanisms, identify fundamental molecular and genetic errors of disease, and to develop ...

.

History of molecular biology

Molecular biology sits at the intersection of biochemistry and genetics; as these scientific disciplines emerged and evolved in the 20th century, it became clear that they both sought to determine the molecular mechanisms which underlie vital cellular functions. Advances in molecular biology have been closely related to the development of new technologies and their optimization. Molecular biology has been elucidated by the work of many scientists, and thus the history of the field depends on an understanding of these scientists and their experiments. The field of genetics arose as an attempt to understand the molecular mechanisms ofgenetic inheritance

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic infor ...

and the structure of a gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "... Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a b ...

. Gregor Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel, OSA (; cs, Řehoř Jan Mendel; 20 July 1822 – 6 January 1884) was a biologist, meteorologist, mathematician, Augustinian friar and abbot of St. Thomas' Abbey in Brünn (''Brno''), Margraviate of Moravia. Mendel wa ...

pioneered this work in 1866, when he first wrote the laws of genetic inheritance based on his studies of mating crosses in pea plants. One such law of genetic inheritance is the law of segregation

Mendelian inheritance (also known as Mendelism) is a type of biological inheritance following the principles originally proposed by Gregor Mendel in 1865 and 1866, re-discovered in 1900 by Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns, and later populariz ...

, which states that diploid individuals with two allele

An allele (, ; ; modern formation from Greek ἄλλος ''állos'', "other") is a variation of the same sequence of nucleotides at the same place on a long DNA molecule, as described in leading textbooks on genetics and evolution.

::"The chro ...

s for a particular gene will pass one of these alleles to their offspring. Because of his critical work, the study of genetic inheritance is commonly referred to as Mendelian genetics

Mendelian inheritance (also known as Mendelism) is a type of biological inheritance following the principles originally proposed by Gregor Mendel in 1865 and 1866, re-discovered in 1900 by Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns, and later popularized ...

.

A major milestone in molecular biology was the discovery of the structure of DNA. This work began in 1869 by Friedrich Miescher

Johannes Friedrich Miescher (13 August 1844 – 26 August 1895) was a Swiss physician and biologist. He was the first scientist to isolate nucleic acid in 1869. He also identified protamine and made a number of other discoveries.

Miescher had i ...

, a Swiss biochemist who first proposed a structure called ''nuclein'', which we now know to be (deoxyribonucleic acid), or DNA. He discovered this unique substance by studying the components of pus-filled bandages, and noting the unique properties of the "phosphorus-containing substances". Another notable contributor to the DNA model was Phoebus Levene

Phoebus Aaron Theodore Levene (25 February 1869 – 6 September 1940) was a Russian born American biochemist who studied the structure and function of nucleic acids. He characterized the different forms of nucleic acid, DNA from RNA, and fou ...

, who proposed the "polynucleotide model" of DNA in 1919 as a result of his biochemical experiments on yeast. In 1950, Erwin Chargaff

Erwin Chargaff (11 August 1905 – 20 June 2002) was an Austro-Hungarian-born American biochemist, writer, Bucovinian Jew who emigrated to the United States during the Nazi era, and professor of biochemistry at Columbia University medical school ...

expanded on the work of Levene and elucidated a few critical properties of nucleic acids: first, the sequence of nucleic acids varies across species. Second, the total concentration of purines (adenine and guanine) is always equal to the total concentration of pyrimidines (cysteine and thymine). This is now known as Chargaff's rule. In 1953, James Watson

James Dewey Watson (born April 6, 1928) is an American molecular biologist, geneticist, and zoologist. In 1953, he co-authored with Francis Crick the academic paper proposing the double helix structure of the DNA molecule. Watson, Crick and ...

and Francis Crick

Francis Harry Compton Crick (8 June 1916 – 28 July 2004) was an English molecular biologist, biophysicist, and neuroscientist. He, James Watson, Rosalind Franklin, and Maurice Wilkins played crucial roles in deciphering the helical stru ...

published the double helical structure of DNA, using the X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract into many specific directions. By measuring the angle ...

work done by Rosalind Franklin

Rosalind Elsie Franklin (25 July 192016 April 1958) was a British chemist and X-ray crystallographer whose work was central to the understanding of the molecular structures of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), RNA (ribonucleic acid), viruses, c ...

and Maurice Wilkins

Maurice Hugh Frederick Wilkins (15 December 1916 – 5 October 2004) was a New Zealand-born British biophysicist and Nobel laureate whose research spanned multiple areas of physics and biophysics, contributing to the scientific understandin ...

. Watson and Crick described the structure of DNA and conjectured about the implications of this unique structure for possible mechanisms of DNA replication.

J. D. Watson and F. H. C. Crick were awarded Nobel prize in 1962, along with Maurice Wilkens, for proposing a model of the structure of DNA.

In 1961, it was demonstrated that when a gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "... Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a b ...

encodes a protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respon ...

, three sequential bases of a gene's DNA specify each successive amino acid of the protein. Thus the genetic code

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

is a triplet code, where each triplet (called a codon) specifies a particular amino acid. Furthermore, it was shown that the codons do not overlap with each other in the DNA sequence encoding a protein, and that each sequence is read from a fixed starting point.

During 1962–1964, through the use of conditional lethal mutants of a bacterial virus, fundamental advances were made in our understanding of the functions and interactions of the proteins employed in the machinery of DNA replication

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all living organisms acting as the most essential part for biological inherita ...

, DNA repair

DNA repair is a collection of processes by which a cell identifies and corrects damage to the DNA molecules that encode its genome. In human cells, both normal metabolic activities and environmental factors such as radiation can cause DNA da ...

, DNA recombination, and in the assembly of molecular structures.

The F.Griffith experiment

In 1928, Fredrick Griffith, encountered a virulence property in pneumococcus bacteria, which was killing lab rats. According to Mendel, prevalent at that time, gene transfer could occur only from parent to daughter cells only. Griffith advanced another theory, stating that gene transfer occurring in member of same generation is known as horizontal gene transfer (HGT). This phenomenon is now referred to as genetic transformation.

Griffith addressed the ''Streptococcus pneumoniae'' bacteria, which had two different strains, one virulent and smooth and one avirulent and rough. The smooth strain had glistering appearance owing to the presence of a type of specific polysaccharide – a polymer of glucose and glucuronic acid capsule. Due to this polysaccharide layer of bacteria, a host's immune system cannot recognize the bacteria and it kills the host. The other, avirulent, rough strain lacks this polysaccharide capsule and has a dull, rough appearance.

Presence or absence of capsule in the strain, is known to be genetically determined. Smooth and rough strains occur in several different type such as S-I, S-II, S-III, etc. and R-I, R-II, R-III, etc. respectively. All this subtypes of S and R bacteria differ with each other in antigen type they produce.

In 1928, Fredrick Griffith, encountered a virulence property in pneumococcus bacteria, which was killing lab rats. According to Mendel, prevalent at that time, gene transfer could occur only from parent to daughter cells only. Griffith advanced another theory, stating that gene transfer occurring in member of same generation is known as horizontal gene transfer (HGT). This phenomenon is now referred to as genetic transformation.

Griffith addressed the ''Streptococcus pneumoniae'' bacteria, which had two different strains, one virulent and smooth and one avirulent and rough. The smooth strain had glistering appearance owing to the presence of a type of specific polysaccharide – a polymer of glucose and glucuronic acid capsule. Due to this polysaccharide layer of bacteria, a host's immune system cannot recognize the bacteria and it kills the host. The other, avirulent, rough strain lacks this polysaccharide capsule and has a dull, rough appearance.

Presence or absence of capsule in the strain, is known to be genetically determined. Smooth and rough strains occur in several different type such as S-I, S-II, S-III, etc. and R-I, R-II, R-III, etc. respectively. All this subtypes of S and R bacteria differ with each other in antigen type they produce.

Hershey and Chase experiment

Confirmation that DNA is the genetic material which is cause of infection came from Hershey and Chase experiment. They used ''E.coli'' and bacteriophage for the experiment. This experiment is also known as blender experiment, as kitchen blender was used as a major piece of apparatus. ''Alfred Hershey'' and ''Martha Chase'' demonstrated that the DNA injected by a phage particle into a bacterium contains all information required to synthesize progeny phage particles. They used radioactivity to tag the bacteriophage's protein coat with radioactive sulphur and DNA with radioactive phosphorus, into two different test tubes respectively. After mixing bacteriophage and ''E.coli'' into the test tube, the incubation period starts in which phage transforms the genetic material in the ''E.coli'' cells. Then the mixture is blended or agitated, which separates the phage from ''E.coli'' cells. The whole mixture is centrifuged and the pellet which contains ''E.coli'' cells was checked and the supernatant was discarded. The ''E.coli'' cells showed radioactive phosphorus, which indicated that the transformed material was DNA not the protein coat.

The transformed DNA gets attached to the DNA of ''E.coli'' and radioactivity is only seen onto the bacteriophage's DNA. This mutated DNA can be passed to the next generation and the theory of Transduction came into existence. Transduction is a process in which the bacterial DNA carry the fragment of bacteriophages and pass it on the next generation. This is also a type of horizontal gene transfer.

Confirmation that DNA is the genetic material which is cause of infection came from Hershey and Chase experiment. They used ''E.coli'' and bacteriophage for the experiment. This experiment is also known as blender experiment, as kitchen blender was used as a major piece of apparatus. ''Alfred Hershey'' and ''Martha Chase'' demonstrated that the DNA injected by a phage particle into a bacterium contains all information required to synthesize progeny phage particles. They used radioactivity to tag the bacteriophage's protein coat with radioactive sulphur and DNA with radioactive phosphorus, into two different test tubes respectively. After mixing bacteriophage and ''E.coli'' into the test tube, the incubation period starts in which phage transforms the genetic material in the ''E.coli'' cells. Then the mixture is blended or agitated, which separates the phage from ''E.coli'' cells. The whole mixture is centrifuged and the pellet which contains ''E.coli'' cells was checked and the supernatant was discarded. The ''E.coli'' cells showed radioactive phosphorus, which indicated that the transformed material was DNA not the protein coat.

The transformed DNA gets attached to the DNA of ''E.coli'' and radioactivity is only seen onto the bacteriophage's DNA. This mutated DNA can be passed to the next generation and the theory of Transduction came into existence. Transduction is a process in which the bacterial DNA carry the fragment of bacteriophages and pass it on the next generation. This is also a type of horizontal gene transfer.

Modern molecular biology

In the early 2020s, molecular biology entered a golden age defined by both vertical and horizontal technical development. Vertically, novel technologies are allowing for real-time monitoring of biological processes at the atomic level. Molecular biologists today have access to increasingly affordable sequencing data at increasingly higher depths, facilitating the development of novel genetic manipulation methods in new non-model organisms. Likewise, synthetic molecular biologists will drive the industrial production of small and macro molecules through the introduction of exogenous metabolic pathways in various prokaryotic and eukaryotic cell lines. Horizontally, sequencing data is becoming more affordable and used in many different scientific fields. This will drive the development of industries in developing nations and increase accessibility to individual researchers. Likewise, CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing experiments can now be conceived and implemented by individuals for under $10,000 in novel organisms, which will drive the development of industrial and medical applicationsRelationship to other biological sciences

The following list describes a viewpoint on the interdisciplinary relationships between molecular biology and other related fields. * ''Molecular biology'' is the study of the molecular underpinnings of the biological phenomena, focusing on molecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms and interactions. * ''Biochemistry'' is the study of the chemical substances and vital processes occurring in livingorganism

In biology, an organism () is any life, living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells (cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy (biology), taxonomy into groups such as Multicellular o ...

s. Biochemist

Biochemists are scientists who are trained in biochemistry. They study chemical processes and chemical transformations in living organisms. Biochemists study DNA, proteins and cell parts. The word "biochemist" is a portmanteau of "biological che ...

s focus heavily on the role, function, and structure of biomolecule

A biomolecule or biological molecule is a loosely used term for molecules present in organisms that are essential to one or more typically biological processes, such as cell division, morphogenesis, or development. Biomolecules include larg ...

s such as protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respon ...

s, lipid

Lipids are a broad group of naturally-occurring molecules which includes fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids incl ...

s, carbohydrate

In organic chemistry, a carbohydrate () is a biomolecule consisting of carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) atoms, usually with a hydrogen–oxygen atom ratio of 2:1 (as in water) and thus with the empirical formula (where ''m'' may or ...

s and nucleic acid

Nucleic acids are biopolymers, macromolecules, essential to all known forms of life. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomers made of three components: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main ...

s.

* ''Genetics'' is the study of how genetic differences affect organisms. Genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar worki ...

attempts to predict how mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, m ...

s, individual gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "... Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a b ...

s and genetic interactions can affect the expression of a phenotype

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology or physical form and structure, its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological prop ...

While researchers practice techniques specific to molecular biology, it is common to combine these with methods from genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar worki ...

and biochemistry

Biochemistry or biological chemistry is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology ...

. Much of molecular biology is quantitative, and recently a significant amount of work has been done using computer science techniques such as bioinformatics

Bioinformatics () is an interdisciplinary field that develops methods and software tools for understanding biological data, in particular when the data sets are large and complex. As an interdisciplinary field of science, bioinformatics combin ...

and computational biology

Computational biology refers to the use of data analysis, mathematical modeling and computational simulations to understand biological systems and relationships. An intersection of computer science, biology, and big data, the field also has fo ...

. Molecular genetics

Molecular genetics is a sub-field of biology that addresses how differences in the structures or expression of DNA molecules manifests as variation among organisms. Molecular genetics often applies an "investigative approach" to determine the ...

, the study of gene structure and function, has been among the most prominent sub-fields of molecular biology since the early 2000s. Other branches of biology are informed by molecular biology, by either directly studying the interactions of molecules in their own right such as in cell biology

Cell biology (also cellular biology or cytology) is a branch of biology that studies the structure, function, and behavior of cells. All living organisms are made of cells. A cell is the basic unit of life that is responsible for the living a ...

and developmental biology

Developmental biology is the study of the process by which animals and plants grow and develop. Developmental biology also encompasses the biology of regeneration, asexual reproduction, metamorphosis, and the growth and differentiation of ste ...

, or indirectly, where molecular techniques are used to infer historical attributes of population

Population typically refers to the number of people in a single area, whether it be a city or town, region, country, continent, or the world. Governments typically quantify the size of the resident population within their jurisdiction using ...

s or species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of ...

, as in fields in evolutionary biology

Evolutionary biology is the subfield of biology that studies the evolutionary processes (natural selection, common descent, speciation) that produced the diversity of life on Earth. It is also defined as the study of the history of life fo ...

such as population genetics

Population genetics is a subfield of genetics that deals with genetic differences within and between populations, and is a part of evolutionary biology. Studies in this branch of biology examine such phenomena as adaptation, speciation, and pop ...

and phylogenetics

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups ...

. There is also a long tradition of studying biomolecule

A biomolecule or biological molecule is a loosely used term for molecules present in organisms that are essential to one or more typically biological processes, such as cell division, morphogenesis, or development. Biomolecules include larg ...

s "from the ground up", or molecularly, in biophysics

Biophysics is an interdisciplinary science that applies approaches and methods traditionally used in physics to study biological phenomena. Biophysics covers all scales of biological organization, from molecular to organismic and populations. ...

.

Techniques of molecular biology

Molecular cloning

Molecular cloning is used to isolate and then transfer a DNA sequence of interest into a plasmid vector. This recombinant DNA technology was first developed in the 1960s. In this technique, a DNA sequence coding for a protein of interest iscloned

Cloning is the process of producing individual organisms with identical or virtually identical DNA, either by natural or artificial means. In nature, some organisms produce clones through asexual reproduction. In the field of biotechnology, ...

using polymerase chain reaction

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a method widely used to rapidly make millions to billions of copies (complete or partial) of a specific DNA sample, allowing scientists to take a very small sample of DNA and amplify it (or a part of it) ...

(PCR), and/or restriction enzyme

A restriction enzyme, restriction endonuclease, REase, ENase or'' restrictase '' is an enzyme that cleaves DNA into fragments at or near specific recognition sites within molecules known as restriction sites. Restriction enzymes are one class ...

s, into a plasmid

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria; howev ...

(expression vector

An expression vector, otherwise known as an expression construct, is usually a plasmid or virus designed for gene expression in cells. The vector is used to introduce a specific gene into a target cell, and can commandeer the cell's mechanism for ...

). The plasmid vector usually has at least 3 distinctive features: an origin of replication, a multiple cloning site A multiple cloning site (MCS), also called a polylinker, is a short segment of DNA which contains many (up to ~20) restriction sites - a standard feature of engineered plasmids. Restriction sites within an MCS are typically unique, occurring only ...

(MCS), and a selective marker (usually antibiotic resistance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) occurs when microbes evolve mechanisms that protect them from the effects of antimicrobials. All classes of microbes can evolve resistance. Fungi evolve antifungal resistance. Viruses evolve antiviral resistanc ...

). Additionally, upstream of the MCS are the promoter regions and the transcription start site, which regulate the expression of cloned gene.

This plasmid can be inserted into either bacterial or animal cells. Introducing DNA into bacterial cells can be done by transformation

Transformation may refer to:

Science and mathematics

In biology and medicine

* Metamorphosis, the biological process of changing physical form after birth or hatching

* Malignant transformation, the process of cells becoming cancerous

* Tran ...

via uptake of naked DNA, conjugation

Conjugation or conjugate may refer to:

Linguistics

*Grammatical conjugation, the modification of a verb from its basic form

* Emotive conjugation or Russell's conjugation, the use of loaded language

Mathematics

*Complex conjugation, the change ...

via cell-cell contact or by transduction via viral vector. Introducing DNA into eukaryotic

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bact ...

cells, such as animal cells, by physical or chemical means is called transfection

Transfection is the process of deliberately introducing naked or purified nucleic acids into eukaryotic cells. It may also refer to other methods and cell types, although other terms are often preferred: " transformation" is typically used to de ...

. Several different transfection techniques are available, such as calcium phosphate transfection, electroporation

Electroporation, or electropermeabilization, is a microbiology technique in which an electrical field is applied to cells in order to increase the permeability of the cell membrane, allowing chemicals, drugs, electrode arrays or DNA to be introdu ...

, microinjection

Microinjection is the use of a glass micropipette to inject a liquid substance at a microscopic or borderline macroscopic level. The target is often a living cell but may also include intercellular space. Microinjection is a simple mechanical ...

and liposome transfection. The plasmid may be integrated into the genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ...

, resulting in a stable transfection, or may remain independent of the genome and expressed temporarily, called a transient transfection.

DNA coding for a protein of interest is now inside a cell, and the protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respon ...

can now be expressed. A variety of systems, such as inducible promoters and specific cell-signaling factors, are available to help express the protein of interest at high levels. Large quantities of a protein can then be extracted from the bacterial or eukaryotic cell. The protein can be tested for enzymatic activity under a variety of situations, the protein may be crystallized so its tertiary structure

Protein tertiary structure is the three dimensional shape of a protein. The tertiary structure will have a single polypeptide chain "backbone" with one or more protein secondary structures, the protein domains. Amino acid side chains may int ...

can be studied, or, in the pharmaceutical industry, the activity of new drugs against the protein can be studied.

Polymerase chain reaction

Polymerase chain reaction

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a method widely used to rapidly make millions to billions of copies (complete or partial) of a specific DNA sample, allowing scientists to take a very small sample of DNA and amplify it (or a part of it) ...

(PCR) is an extremely versatile technique for copying DNA. In brief, PCR allows a specific DNA sequence

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine. Th ...

to be copied or modified in predetermined ways. The reaction is extremely powerful and under perfect conditions could amplify one DNA molecule to become 1.07 billion molecules in less than two hours. PCR has many applications, including the study of gene expression, the detection of pathogenic microorganisms, the detection of genetic mutations, and the introduction of mutations to DNA. The PCR technique can be used to introduce restriction enzyme sites to ends of DNA molecules, or to mutate particular bases of DNA, the latter is a method referred to as site-directed mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis is a molecular biology method that is used to make specific and intentional mutating changes to the DNA sequence of a gene and any gene products. Also called site-specific mutagenesis or oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesi ...

. PCR can also be used to determine whether a particular DNA fragment is found in a cDNA library. PCR has many variations, like reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is a laboratory technique combining reverse transcription of RNA into DNA (in this context called complementary DNA or cDNA) and amplification of specific DNA targets using polymerase chai ...

) for amplification of RNA, and, more recently, quantitative PCR

A real-time polymerase chain reaction (real-time PCR, or qPCR) is a laboratory technique of molecular biology based on the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). It monitors the amplification of a targeted DNA molecule during the PCR (i.e., in real ...

which allow for quantitative measurement of DNA or RNA molecules.

Gel electrophoresis

Gel electrophoresis

Gel electrophoresis is a method for separation and analysis of biomacromolecules ( DNA, RNA, proteins, etc.) and their fragments, based on their size and charge. It is used in clinical chemistry to separate proteins by charge or size (IEF ...

is a technique which separates molecules by their size using an agarose or polyacrylamide gel. This technique is one of the principal tools of molecular biology. The basic principle is that DNA fragments can be separated by applying an electric current across the gel - because the DNA backbone contains negatively charged phosphate groups, the DNA will migrate through the agarose gel towards the positive end of the current. Proteins can also be separated on the basis of size using an SDS-PAGE

SDS-PAGE (sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) is a discontinuous electrophoretic system developed by Ulrich K. Laemmli which is commonly used as a method to separate proteins with molecular masses between 5 and 250 kDa. ...

gel, or on the basis of size and their electric charge

Electric charge is the physical property of matter that causes charged matter to experience a force when placed in an electromagnetic field. Electric charge can be ''positive'' or ''negative'' (commonly carried by protons and electrons respecti ...

by using what is known as a 2D gel electrophoresis.

The Bradford Assay

The Bradford Assay is a molecular biology technique which enables the fast, accurate quantitation of protein molecules utilizing the unique properties of a dye calledCoomassie Brilliant Blue

Coomassie brilliant blue is the name of two similar triphenylmethane dyes that were developed for use in the textile industry but are now commonly used for staining proteins in analytical biochemistry. Coomassie brilliant blue G-250 differs fr ...

G-250. Coomassie Blue undergoes a visible color shift from reddish-brown to bright blue upon binding to protein. In its unstable, cationic state, Coomassie Blue has a background wavelength of 465 nm and gives off a reddish-brown color. When Coomassie Blue binds to protein in an acidic solution, the background wavelength shifts to 595 nm and the dye gives off a bright blue color. Proteins in the assay bind Coomassie blue in about 2 minutes, and the protein-dye complex is stable for about an hour, although it's recommended that absorbance readings are taken within 5 to 20 minutes of reaction initiation. The concentration of protein in the Bradford assay can then be measured using a visible light spectrophotometer, and therefore does not require extensive equipment.

This method was developed in 1975 by Marion M. Bradford, and has enabled significantly faster, more accurate protein quantitation compared to previous methods: the Lowry procedure and the biuret assay. Unlike the previous methods, the Bradford assay is not susceptible to interference by several non-protein molecules, including ethanol, sodium chloride, and magnesium chloride. However, it is susceptible to influence by strong alkaline buffering agents, such as sodium dodecyl sulfate

Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) or sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS), sometimes written sodium laurilsulfate, is an organic compound with the formula . It is an anionic surfactant used in many cleaning and hygiene products. This compound is the sodium sal ...

(SDS).

Macromolecule blotting and probing

The terms ''northern'', ''western'' and ''eastern'' blotting are derived from what initially was a molecular biology joke that played on the term ''Southern blot

A Southern blot is a method used in molecular biology for detection of a specific DNA sequence in DNA samples. Southern blotting combines transfer of electrophoresis-separated DNA fragments to a filter membrane and subsequent fragment detec ...

ting'', after the technique described by Edwin Southern

Sir Edwin Mellor Southern (born 7 June 1938) is an English Lasker Award-winning molecular biologist, Emeritus Professor of Biochemistry at the University of Oxford and a fellow of Trinity College, Oxford. He is most widely known for the inve ...

for the hybridisation of blotted DNA. Patricia Thomas, developer of the RNA blot which then became known as the ''northern blot'', actually didn't use the term.

Southern blotting

Named after its inventor, biologistEdwin Southern

Sir Edwin Mellor Southern (born 7 June 1938) is an English Lasker Award-winning molecular biologist, Emeritus Professor of Biochemistry at the University of Oxford and a fellow of Trinity College, Oxford. He is most widely known for the inve ...

, the Southern blot

A Southern blot is a method used in molecular biology for detection of a specific DNA sequence in DNA samples. Southern blotting combines transfer of electrophoresis-separated DNA fragments to a filter membrane and subsequent fragment detec ...

is a method for probing for the presence of a specific DNA sequence within a DNA sample. DNA samples before or after restriction enzyme

A restriction enzyme, restriction endonuclease, REase, ENase or'' restrictase '' is an enzyme that cleaves DNA into fragments at or near specific recognition sites within molecules known as restriction sites. Restriction enzymes are one class ...

(restriction endonuclease) digestion are separated by gel electrophoresis and then transferred to a membrane by blotting via capillary action

Capillary action (sometimes called capillarity, capillary motion, capillary rise, capillary effect, or wicking) is the process of a liquid flowing in a narrow space without the assistance of, or even in opposition to, any external forces li ...

. The membrane is then exposed to a labeled DNA probe that has a complement base sequence to the sequence on the DNA of interest. Southern blotting is less commonly used in laboratory science due to the capacity of other techniques, such as PCR PCR or pcr may refer to:

Science

* Phosphocreatine, a phosphorylated creatine molecule

* Principal component regression, a statistical technique

Medicine

* Polymerase chain reaction

** COVID-19 testing, often performed using the polymerase chain r ...

, to detect specific DNA sequences from DNA samples. These blots are still used for some applications, however, such as measuring transgene

A transgene is a gene that has been transferred naturally, or by any of a number of genetic engineering techniques, from one organism to another. The introduction of a transgene, in a process known as transgenesis, has the potential to change the ...

copy number in transgenic mice

A genetically modified mouse or genetically engineered mouse model (GEMM) is a mouse (''Mus musculus'') that has had its genome altered through the use of genetic engineering techniques. Genetically modified mice are commonly used for research or ...

or in the engineering of gene knockout

A gene knockout (abbreviation: KO) is a genetic technique in which one of an organism's genes is made inoperative ("knocked out" of the organism). However, KO can also refer to the gene that is knocked out or the organism that carries the gene kno ...

embryonic stem cell lines.

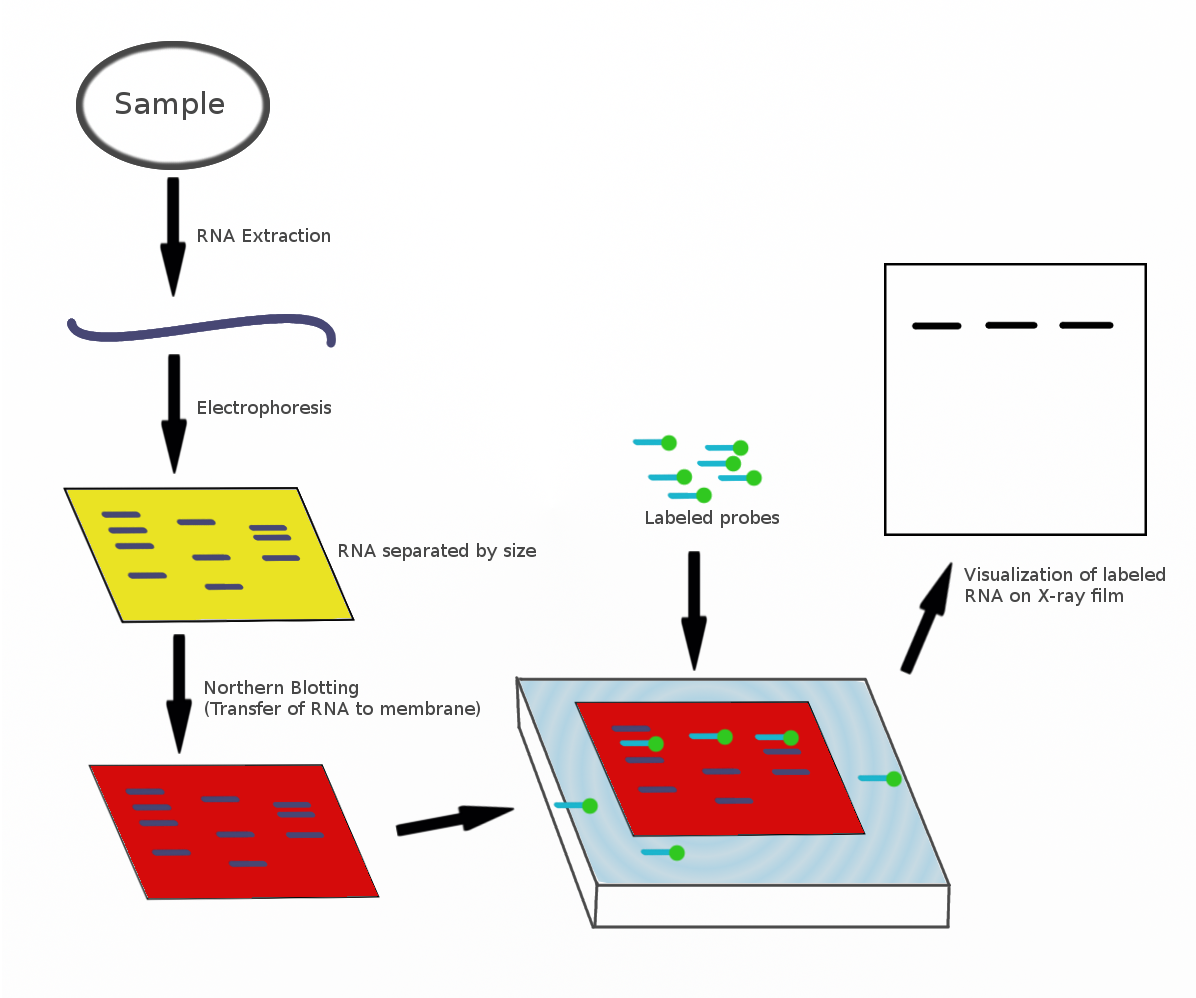

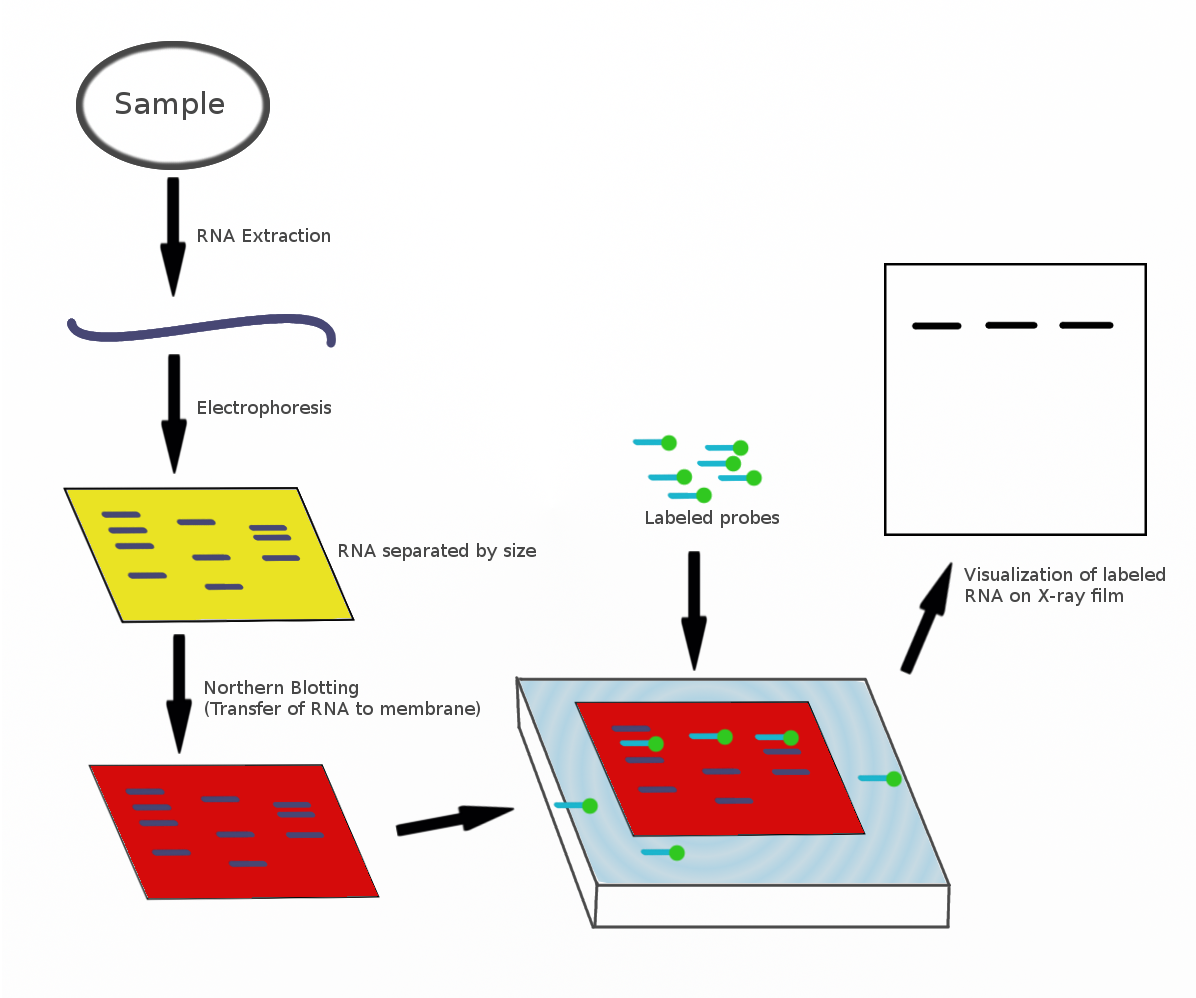

Northern blotting

The

The northern blot

The northern blot, or RNA blot,Gilbert, S. F. (2000) Developmental Biology, 6th Ed. Sunderland MA, Sinauer Associates. is a technique used in molecular biology research to study gene expression by detection of RNA (or isolated mRNA) in a sample.Ke ...

is used to study the presence of specific RNA molecules as relative comparison among a set of different samples of RNA. It is essentially a combination of denaturing RNA gel electrophoresis, and a blot

Blot may refer to:

Surname

*Guillaume Blot (born 1985), French racing cyclist

* Harold W. Blot (born 1938), served as United States Deputy Chief of Staff for Aviation

*Jean-François Joseph Blot (1781–1857), French soldier and politician

*Yvan ...

. In this process RNA is separated based on size and is then transferred to a membrane that is then probed with a labeled complement

A complement is something that completes something else.

Complement may refer specifically to:

The arts

* Complement (music), an interval that, when added to another, spans an octave

** Aggregate complementation, the separation of pitch-clas ...

of a sequence of interest. The results may be visualized through a variety of ways depending on the label used; however, most result in the revelation of bands representing the sizes of the RNA detected in sample. The intensity of these bands is related to the amount of the target RNA in the samples analyzed. The procedure is commonly used to study when and how much gene expression is occurring by measuring how much of that RNA is present in different samples, assuming that no post-transcriptional regulation occurs and that the levels of mRNA reflect proportional levels of the corresponding protein being produced. It is one of the most basic tools for determining at what time, and under what conditions, certain genes are expressed in living tissues.

Western blotting

A western blot is a technique by which specific proteins can be detected from a mixture of proteins. Western blots can be used to determine the size of isolated proteins, as well as to quantify their expression. Inwestern blot

The western blot (sometimes called the protein immunoblot), or western blotting, is a widely used analytical technique in molecular biology and immunogenetics to detect specific proteins in a sample of tissue homogenate or extract. Besides detec ...

ting, proteins are first separated by size, in a thin gel sandwiched between two glass plates in a technique known as SDS-PAGE

SDS-PAGE (sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) is a discontinuous electrophoretic system developed by Ulrich K. Laemmli which is commonly used as a method to separate proteins with molecular masses between 5 and 250 kDa. ...

. The proteins in the gel are then transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride

Polyvinylidene fluoride or polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) is a highly non-reactive thermoplastic fluoropolymer produced by the polymerization of vinylidene difluoride.

PVDF is a specialty plastic used in applications requiring the highest pur ...

(PVDF), nitrocellulose, nylon, or other support membrane. This membrane can then be probed with solutions of antibodies. Antibodies that specifically bind to the protein of interest can then be visualized by a variety of techniques, including colored products, chemiluminescence

Chemiluminescence (also chemoluminescence) is the emission of light ( luminescence) as the result of a chemical reaction. There may also be limited emission of heat. Given reactants A and B, with an excited intermediate ◊,

: + -> lozenge - ...

, or autoradiography

An autoradiograph is an image on an X-ray film or nuclear emulsion produced by the pattern of decay emissions (e.g., beta particles or gamma rays) from a distribution of a radioactive substance. Alternatively, the autoradiograph is also availab ...

. Often, the antibodies are labeled with enzymes. When a chemiluminescent substrate

Substrate may refer to:

Physical layers

*Substrate (biology), the natural environment in which an organism lives, or the surface or medium on which an organism grows or is attached

** Substrate (locomotion), the surface over which an organism lo ...

is exposed to the enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecule ...

it allows detection. Using western blotting techniques allows not only detection but also quantitative analysis. Analogous methods to western blotting can be used to directly stain specific proteins in live cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery w ...

or tissue sections.

Eastern blotting

The eastern blotting technique is used to detectpost-translational modification

Post-translational modification (PTM) is the covalent and generally enzymatic modification of proteins following protein biosynthesis. This process occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum and the golgi apparatus. Proteins are synthesized by ribos ...

of proteins. Proteins blotted on to the PVDF or nitrocellulose membrane are probed for modifications using specific substrates.

Microarrays

DNA microarray

A DNA microarray (also commonly known as DNA chip or biochip) is a collection of microscopic DNA spots attached to a solid surface. Scientists use DNA microarrays to measure the expression levels of large numbers of genes simultaneously or to ...

is a collection of spots attached to a solid support such as a microscope slide

A microscope slide is a thin flat piece of glass, typically 75 by 26 mm (3 by 1 inches) and about 1 mm thick, used to hold objects for examination under a microscope. Typically the object is mounted (secured) on the slide, and then b ...

where each spot contains one or more single-stranded DNA oligonucleotide

Oligonucleotides are short DNA or RNA molecules, oligomers, that have a wide range of applications in genetic testing, research, and forensics. Commonly made in the laboratory by solid-phase chemical synthesis, these small bits of nucleic acids ...

fragments. Arrays make it possible to put down large quantities of very small (100 micrometre diameter) spots on a single slide. Each spot has a DNA fragment molecule that is complementary to a single DNA sequence

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine. Th ...

. A variation of this technique allows the gene expression

Gene expression is the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, protein or non-coding RNA, and ultimately affect a phenotype, as the final effect. ...

of an organism at a particular stage in development to be qualified (expression profiling

In the field of molecular biology, gene expression profiling is the measurement of the activity (the expression) of thousands of genes at once, to create a global picture of cellular function. These profiles can, for example, distinguish between ...

). In this technique the RNA in a tissue is isolated and converted to labeled complementary DNA

In genetics, complementary DNA (cDNA) is DNA synthesized from a single-stranded RNA (e.g., messenger RNA ( mRNA) or microRNA (miRNA)) template in a reaction catalyzed by the enzyme reverse transcriptase. cDNA is often used to express a sp ...

(cDNA). This cDNA is then hybridized to the fragments on the array and visualization of the hybridization can be done. Since multiple arrays can be made with exactly the same position of fragments, they are particularly useful for comparing the gene expression of two different tissues, such as a healthy and cancerous tissue. Also, one can measure what genes are expressed and how that expression changes with time or with other factors.

There are many different ways to fabricate microarrays; the most common are silicon chips, microscope slides with spots of ~100 micrometre diameter, custom arrays, and arrays with larger spots on porous membranes (macroarrays). There can be anywhere from 100 spots to more than 10,000 on a given array. Arrays can also be made with molecules other than DNA.

Allele-specific oligonucleotide

Allele-specific oligonucleotide (ASO) is a technique that allows detection of single base mutations without the need for PCR or gel electrophoresis. Short (20–25 nucleotides in length), labeled probes are exposed to the non-fragmented target DNA, hybridization occurs with high specificity due to the short length of the probes and even a single base change will hinder hybridization. The target DNA is then washed and the labeled probes that didn't hybridize are removed. The target DNA is then analyzed for the presence of the probe via radioactivity or fluorescence. In this experiment, as in most molecular biology techniques, a control must be used to ensure successful experimentation. In molecular biology, procedures and technologies are continually being developed and older technologies abandoned. For example, before the advent of DNAgel electrophoresis

Gel electrophoresis is a method for separation and analysis of biomacromolecules ( DNA, RNA, proteins, etc.) and their fragments, based on their size and charge. It is used in clinical chemistry to separate proteins by charge or size (IEF ...

(agarose

Agarose is a heteropolysaccharide, generally extracted from certain red seaweed. It is a linear polymer made up of the repeating unit of agarobiose, which is a disaccharide made up of D-galactose and 3,6-anhydro-L-galactopyranose. Agarose is ...

or polyacrylamide

Polyacrylamide (abbreviated as PAM) is a polymer with the formula (-CH2CHCONH2-). It has a linear-chain structure. PAM is highly water-absorbent, forming a soft gel when hydrated. In 2008, an estimated 750,000,000 kg were produced, mainly f ...

), the size of DNA molecules was typically determined by rate sedimentation

Sedimentation is the deposition of sediments. It takes place when particles in suspension settle out of the fluid in which they are entrained and come to rest against a barrier. This is due to their motion through the fluid in response to t ...

in sucrose gradients, a slow and labor-intensive technique requiring expensive instrumentation; prior to sucrose gradients, viscometry

A viscometer (also called viscosimeter) is an instrument used to measure the viscosity of a fluid. For liquids with viscosities which vary with flow conditions, an instrument called a rheometer is used. Thus, a rheometer can be considered as a s ...

was used. Aside from their historical interest, it is often worth knowing about older technology, as it is occasionally useful to solve another new problem for which the newer technique is inappropriate.

See also

References

Further reading

* * *External links

* * {{Portal bar, Biology