Barbod on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Barbad (; ) was a Persian musician-poet,

In the literary scholar

In the literary scholar

Barbad's lute was the four-stringed '' barbat''. It had been popular in his time, but no traces of the instrument survive and it was eventually substituted for the

Barbad's lute was the four-stringed '' barbat''. It had been popular in his time, but no traces of the instrument survive and it was eventually substituted for the

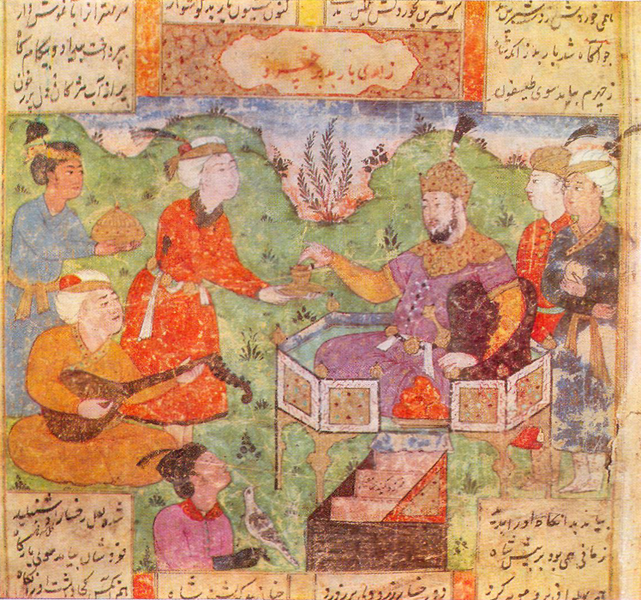

File:King Khusraw Parviz Listening to Barbad the Concealed Musician- Illustration from a manuscript of the Shahnama (Book of kings) LACMA M.73.5.406.jpg, Illustration from the ''

"Barbad and Nakisā"

a song inspired by Barbad performed by the

music theorist

Music theory is the study of theoretical frameworks for understanding the practices and possibilities of music. '' The Oxford Companion to Music'' describes three interrelated uses of the term "music theory": The first is the " rudiments", that ...

and composer of Sasanian music

Sasanian music encompasses the music of the Sasanian Empire, which existed from 224 to 651 CE. Many Sasanian Shahanshahs were enthusiastic supporters of music, including the founder of the empire Ardashir I and Bahram V. In particular, Khosrow II ...

. He served as chief minstrel-poet under the Shahanshah Khosrow II

Khosrow II (spelled Chosroes II in classical sources; and ''Khosrau''), commonly known as Khosrow Parviz (New Persian: , "Khosrow the Victorious"), is considered to be the last great Sasanian King of Kings (Shahanshah) of Iran, ruling from 590 ...

(). A '' barbat'' player, he was the most distinguished Persian musician of his time and is regarded among the major figures in the history of Persian music Persian music may refer to various types of the music of Persia/Name of Iran, Iran or other List of countries and territories where Persian is an official language, Persian-speaking countries:

*Persian traditional music

*Persian ritual music

*Persi ...

.

Despite scarce biographical information, Barbad's historicity

Historicity is the historical actuality of persons and events, meaning the quality of being part of history instead of being a historical myth, legend, or fiction. The historicity of a claim about the past is its factual status. Historicity deno ...

is generally secure. He was highly regarded in the court of Khosrow, and interacted with other musicians, such as Sarkash

Sasanian music encompasses the music of the Sasanian Empire, which existed from 224 to 651 CE. Many Sasanian Shahanshahs were enthusiastic supporters of music, including the founder of the empire Ardashir I and Bahram V. In particular, Khosrow II ...

. Although he is traditionally credited with numerous innovations in Persian music theory and practice, the attributions remain tentative since they are ascribed centuries after his death. Practically all Barbad's music or poetry is lost, except a single poem fragment and the titles of a few compositions.

No Sasanian sources discuss Barbad, suggesting his reputation was preserved through oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication in which knowledge, art, ideas and culture are received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another.Jan Vansina, Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (19 ...

, until at least the earliest written account by the poet Khaled ibn Fayyaz ( ). Barbad appears frequently in later Persian literature

Persian literature comprises oral compositions and written texts in the Persian language and is one of the world's oldest literatures. It spans over two-and-a-half millennia. Its sources have been within Greater Iran including present-day ...

, most famously in Ferdowsi

Abu'l-Qâsem Ferdowsi Tusi (also Firdawsi, ; 940 – 1019/1025) was a Persians, Persian poet and the author of ''Shahnameh'' ("Book of Kings"), which is one of the world's longest epic poetry, epic poems created by a single poet, and the gre ...

's ''Shahnameh

The ''Shahnameh'' (, ), also transliterated ''Shahnama'', is a long epic poem written by the Persian literature, Persian poet Ferdowsi between and 1010 CE and is the national epic of Greater Iran. Consisting of some 50,000 distichs or couple ...

''. The content and abundance of such references demonstrate his unique influence, inspiring musicians such as Ishaq al-Mawsili

Ishaq al-Mawsili (; 767/772 – March 850) was an Arab musician of Persian origin active as a composer, singer and music theorist. The leading musician of his time in the Abbasid Caliphate, he served under six successive Abbasid caliphs: Haru ...

. Often described as the "founder of Persian music", Barbad remains a celebrated figure in modern-day Iran, Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. It is bordered by Pakistan to the Durand Line, east and south, Iran to the Afghanistan–Iran borde ...

and Tajikistan

Tajikistan, officially the Republic of Tajikistan, is a landlocked country in Central Asia. Dushanbe is the capital city, capital and most populous city. Tajikistan borders Afghanistan to the Afghanistan–Tajikistan border, south, Uzbekistan to ...

.

Name

Posthumous sources refer to theSasanian

The Sasanian Empire (), officially Eranshahr ( , "Empire of the Iranians"), was an Iranian empire that was founded and ruled by the House of Sasan from 224 to 651. Enduring for over four centuries, the length of the Sasanian dynasty's reign ...

musician with little consistency. Persian sources record "Barbād" while Arabic scholars use Fahl(a)bad, Bahl(a)bad, Fahl(a)wad, Fahr(a)bad, Bahr(a)bad and Bārbad/ḏ. Modern sources most often use "Barbad", a spelling that Danish orientalist Arthur Christensen

Arthur Emanuel Christensen (9 January 1875 – 31 March 1945) was a Danish orientalist and scholar of Iranian philology and folklore. He is best known for his works on the Iranian history, mythology, religions, medicine and music.

Biography

Ch ...

first asserted to be correct. However, the German orientalist Theodor Nöldeke

Theodor Nöldeke (; born 2 March 1836 – 25 December 1930) was a German orientalist and scholar, originally a student of Heinrich Ewald. He is one of the founders of the field of Quranic studies, especially through his foundational work titled ...

suggested that spellings from Arabic commentators such as "Fahl(a)bad" were really an arabicization

Arabization or Arabicization () is a sociological process of cultural change in which a non-Arab society becomes Arab, meaning it either directly adopts or becomes strongly influenced by the Arabic language, culture, literature, art, music, and ...

of his actual name, probably Pahrbad/Pahlbad. Nöldeke furthered that "Bārbad" was a mistake in the interpretation of ambiguous Pahlavi characters. The Iranologist

Iranian studies ( '), also referred to as Iranology and Iranistics, is an interdisciplinary field dealing with the research and study of the civilization, history, literature, art and culture of Iranian peoples. It is a part of the wider field ...

Ahmad Tafazzoli

Ahmad Tafazzoli (December 16, 1937, Isfahan – January 15, 1997, Tehran) () was an Iranian Iranist and professor of ancient Iranian languages and culture at Tehran University.

One of his most important books is ''Pre-Islamic Persian Literature ...

agreed with Nöldeke, citing a Sasanian seal

Seal may refer to any of the following:

Common uses

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, also called "true seal"

** Fur seal

** Eared seal

* Seal ( ...

which includes the name "Pahrbad/Pahlbad" and the earliest mention of the Sasanian musician, which uses a spelling—"Bahrbad/Bahlbad"—that suggests the name had been arabicized.

Background

The music of Iran/Persia stretches to at least the depictions ofarched harp

Arched harps is a category in the Hornbostel-Sachs classification system for musical instruments, a type of harp. The instrument may also be called bow harp. With arched harps, the neck forms a continuous arc with the body and has an open gap ...

s from 3300–3100 BCE, though not until the period of the Sasanian Empire in 224–651 CE is substantial information available. This influx of Sasanian records suggests a prominent musical culture in the Empire, especially in the areas dominated by Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism ( ), also called Mazdayasnā () or Beh-dīn (), is an Iranian religions, Iranian religion centred on the Avesta and the teachings of Zoroaster, Zarathushtra Spitama, who is more commonly referred to by the Greek translation, ...

. Many Sasanian Shahanshah

Shāh (; ) is a royal title meaning "king" in the Persian language.Yarshater, Ehsa, ''Iranian Studies'', vol. XXII, no. 1 (1989) Though chiefly associated with the List of monarchs of Iran, monarchs of Iran, it was also used to refer to the ...

s were ardent supporters of music, including the founder of the empire Ardashir I

Ardashir I (), also known as Ardashir the Unifier (180–242 AD), was the founder of the Sasanian Empire, the last empire of ancient Iran. He was also Ardashir V of the Kings of Persis, until he founded the new empire. After defeating the last Par ...

and Bahram V

Bahram V (also spelled Wahram V or Warahran V; ), also known as Bahram Gur (New Persian: , "Bahram the onager unter), was the Sasanian Empire, Sasanian King of Kings (''shahanshah'') from 420 to 438.

The son of the incumbent Sasanian shah Ya ...

. Khosrow II

Khosrow II (spelled Chosroes II in classical sources; and ''Khosrau''), commonly known as Khosrow Parviz (New Persian: , "Khosrow the Victorious"), is considered to be the last great Sasanian King of Kings (Shahanshah) of Iran, ruling from 590 ...

() was the most outstanding patron

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, art patronage refers to the support that princes, popes, and other wealthy and influential people ...

, his reign being regarded as a golden age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the ''Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages of Man, Ages, Gold being the first and the one during wh ...

of Persian music. Musicians in Khosrow's service include Āzādvar-e Changi, Bāmshād

Bamshad () or Bāmšād was a musician of Sasanian music during the reign of Khosrow II ().

Life and career

Many Shahanshahs of the Sasanian Empire were ardent supporters of music, including the founder of the empire Ardashir I and Bahram V. Kh ...

, the harpist Nagisa

is a Japanese name, Japanese given name used by either sex and is occasionally used as a surname.

Written forms

Nagisa can be written using different kanji characters and can mean:

*渚, "beach, strand"

*汀, "water's edge/shore"

*凪砂, "lu ...

(Nakisa), Ramtin, Sarkash (also Sargis or Sarkas) and Barbad, who was by-far the most famous. These musicians were usually active as minstrel

A minstrel was an entertainer, initially in medieval Europe. The term originally described any type of entertainer such as a musician, juggler, acrobat, singer or fool; later, from the sixteenth century, it came to mean a specialist enter ...

s, which were performers who worked as both court poets and musicians; in the Sasanian Empire there was little distinction between poetry and music.

Though many Middle Persian

Middle Persian, also known by its endonym Pārsīk or Pārsīg ( Inscriptional Pahlavi script: , Manichaean script: , Avestan script: ) in its later form, is a Western Middle Iranian language which became the literary language of the Sasania ...

(Pahlavi) texts of the Sasanian Empire survive, only one—''Khusraw qubadan va ridak''—includes commentary on music, though neither it or any other Sasanian sources discuss Barbad. Barbad's reputation must have been transmitted through oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication in which knowledge, art, ideas and culture are received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another.Jan Vansina, Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (19 ...

, until at least the earliest source: an Arabic poem by Khaled ibn Fayyaz ( ). In later ancient Arabic and Persian sources Barbad is the most discussed Sasanian musician, though he is rarely included in writings dedicated solely to music. A rare exception to this is a brief mention in Muhammad bin Muhammad bin Muhammad Nishābūrī's music treatise ''Rasaleh-i musiqi-i''. Ancient sources in general give little biographical information and most of what is available is shrouded in mythological anecdotes. Tales from the poet Ferdowsi

Abu'l-Qâsem Ferdowsi Tusi (also Firdawsi, ; 940 – 1019/1025) was a Persians, Persian poet and the author of ''Shahnameh'' ("Book of Kings"), which is one of the world's longest epic poetry, epic poems created by a single poet, and the gre ...

's ''Shahnameh

The ''Shahnameh'' (, ), also transliterated ''Shahnama'', is a long epic poem written by the Persian literature, Persian poet Ferdowsi between and 1010 CE and is the national epic of Greater Iran. Consisting of some 50,000 distichs or couple ...

'', written during the late 10th century, include the most celebrated accounts of Barbad. Other important sources included Ferdowsi's contemporary, the poet al-Tha'alibi

Abū Manṣūr ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Muḥammad ibn Ismāʿīl al-Thaʿālibī () (961–1038), was a writer famous for his anthologies and collections of epigrams. As a writer of prose and verse in his own right, distinction between his and the w ...

in his ''Ghurar al-saya'', as well as ''Khosrow and Shirin

''Khosrow and Shirin'' () is a romantic Epic poetry, epic poem by the Persians, Persian poet Nizami Ganjavi (1141–1209). It is the second work of his set of five poems known collectively as Khamsa of Nizami, ''Khamsa''. It tells a highly el ...

'' and ''Haft Peykar

''Haft Peykar'' (), also known as ''Bahramnameh'' (, ''The Book of Bahram'', referring to the Sasanian emperor Bahram V), is a romantic epic poem by Persian poet Nizami Ganjavi, written in 1197. This poem is one of his five works known collecti ...

'' from the poet Nezami Ganjavi

Nizami Ganjavi (; c. 1141 – 1209), Nizami Ganje'i, Nizami, or Nezāmi, whose formal name was Jamal ad-Dīn Abū Muḥammad Ilyās ibn-Yūsuf ibn-Zakkī,Mo'in, Muhammad(2006), "Tahlil-i Haft Paykar-i Nezami", Tehran.: p. 2: Some commentators h ...

's ''Khamsa of Nizami

The ''Khamsa'' (, 'Quintet' or 'Quinary', from Arabic) or ''Panj Ganj'' (, 'Five Treasures') is the main and best known work of Nizami Ganjavi.

Description

The ''Khamsa'' is in five long narrative poems:

* '' Makhzan-ol-Asrâr'' (, 'The Treas ...

'' from the late 12th century. Despite this plethora of stories depicting him in a legendary context, scholars generally consider Barbad a wholly historical person.

Life and career

Early life

There are contradictory ancient accounts as to the location of Barbad's birthplace. Older sources record the city ofMerv

Merv (, ', ; ), also known as the Merve Oasis, was a major Iranian peoples, Iranian city in Central Asia, on the historical Silk Road, near today's Mary, Turkmenistan. Human settlements on the site of Merv existed from the 3rd millennium& ...

in northeastern Khorasan

KhorasanDabeersiaghi, Commentary on Safarnâma-e Nâsir Khusraw, 6th Ed. Tehran, Zavvâr: 1375 (Solar Hijri Calendar) 235–236 (; , ) is a historical eastern region in the Iranian Plateau in West and Central Asia that encompasses western and no ...

, while later works give Jahrom

Jahrom () is a city in the Central District of Jahrom County, Fars province, Iran, serving as capital of both the county and the district. It is also the administrative center for Jolgah Rural District. The previous capital of the rural di ...

, a small city south of Shiraz

Shiraz (; ) is the List of largest cities of Iran, fifth-most-populous city of Iran and the capital of Fars province, which has been historically known as Pars (Sasanian province), Pars () and Persis. As of the 2016 national census, the popu ...

in Pars

Pars may refer to:

* Fars province of Iran, also known as Pars Province

* Pars (Sasanian province), a province roughly corresponding to the present-day Fars, 224–651

* ''Pars'', for ''Persia'' or ''Iran'', in the Persian language

* Pars News Ag ...

. Tafazzoli postulated that the writers who recorded Jahrom were referencing a line of Ferdowsi's ''Shahnameh'' that says Barbad traveled from Jarom to the capital in Ctesiphon

Ctesiphon ( ; , ''Tyspwn'' or ''Tysfwn''; ; , ; Thomas A. Carlson et al., “Ctesiphon — ܩܛܝܣܦܘܢ ” in The Syriac Gazetteer last modified July 28, 2014, http://syriaca.org/place/58.) was an ancient city in modern Iraq, on the eastern ba ...

when Khosrow was murdered; the modern historian Mehrdad Kia

Mehrdad Kia (Persian: مهرداد کیا) is a Professor of History and Director of the Central and Southwest Asian Studies Center at the University of Montana. He focusses on the history of the Middle East and Central Asia. Kia also holds interes ...

records only Merv.

Ferdowsi and al-Tha'alibi both relay a story that Barbad was a gifted young musician who sought a place as a court minstrel under Khosrow II but the jealous chief court minstrel Sarkash supposedly prevented this. As such, Barbad hid in the royal garden by dressing in all green. When Khosrow walked by Barbad sang three songs with his lute: ''Dād-āfrīd'' ("created by god"), ''Peykār-e gord'' ("battle of the hero" or "splendor of Farkar") and ''Sabz dar sabz'' ("green in the green"). Khosrow was immediately impressed and ordered that Barbad be appointed chief minstrel, a position known as the ''shah-i ramishgaran''. In Nizami's ''Khosrow and Shirin'', Khosrow II is said to have had a dream where his grandfather Khosrow I

Khosrow I (also spelled Khosrau, Khusro or Chosroes; ), traditionally known by his epithet of Anushirvan ("the Immortal Soul"), was the Sasanian King of Kings of Iran from 531 to 579. He was the son and successor of Kavad I ().

Inheriting a rei ...

prophesied that he would have a "have a minstrel called Barbad whose art could make even poison taste delicious".

Stories with Khosrow

Since his appointment at court, Barbad was Khosrow's favorite musician, and many stories exist about this prestige. His relationship with Khosrow was reportedly such that other members of the court would seek his assistance in mediating conflicts between them and the Shahanshah. A story in Nizami's ''Khosrow and Shirin'', tells of Khosrow andShirin

Shirin (; died 628) was wife of the Sasanian emperor Khosrow II (). In the revolution after the death of Khosrow's father Hormizd IV, the General Bahram Chobin took power over the Persian empire. Shirin fled with Khosrow to Syria, where they l ...

as previously together, but forced to separate for political reasons; Khosrow marries someone else, but is soon reminded of Shirin. The two later met and arranged for the Nagisa to sing of Shirin's love for Khosrow, while Barbad sung of Khosrow's love for Shirin. The duet reconciled the couple and was recorded by Nizami in 263 couplet

In poetry, a couplet ( ) or distich ( ) is a pair of successive lines that rhyme and have the same metre. A couplet may be formal (closed) or run-on (open). In a formal (closed) couplet, each of the two lines is end-stopped, implying that there ...

s. The idea of setting music to poetry in order to represent the emotions of characters was unprecedented in Persian music. According to the 10th-century historian Ibn al-Faqih al-Hamadani's ''Kitab al-buldan'', Khosrow's wife Shirin asked Barbad to remind Khosrow of his promise to build her a castle. To do so, he sung a song and was rewarded with an estate near Isfahan

Isfahan or Esfahan ( ) is a city in the Central District (Isfahan County), Central District of Isfahan County, Isfahan province, Iran. It is the capital of the province, the county, and the district. It is located south of Tehran. The city ...

for him and his family. According to the Seljuk Seljuk (, ''Selcuk'') or Saljuq (, ''Saljūq'') may refer to:

* Seljuk Empire (1051–1153), a medieval empire in the Middle East and central Asia

* Seljuk dynasty (c. 950–1307), the ruling dynasty of the Seljuk Empire and subsequent polities

* S ...

scholar Nizam al-Mulk

Abū ʿAlī Ḥasan ibn ʿAlī Ṭūsī () (1018 – 1092), better known by his honorific title of Niẓām al-Mulk (), was a Persian Sunni scholar, jurist, political philosopher and vizier of the Seljuk Empire. Rising from a low position w ...

, Barbad visited a courtier who had been imprisoned by Khosrow and upon being scolded by the Shahanshah, a "witty remark" was enough to resolve the situation.

In the literary scholar

In the literary scholar Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani

Ali ibn al-Husayn al-Iṣfahānī (), also known as Abul-Faraj, (full form: Abū al-Faraj ʿAlī ibn al-Ḥusayn ibn Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn al-Ḥaytham al-Umawī al-Iṣfahānī) (897–967Common Era, CE / 284–356Islamic calendar, AH) w ...

's ''Kitab al-Aghani

''Kitāb al-Aghānī'' (), is an encyclopedic collection of poems and songs that runs to over 20 volumes in modern editions, attributed to the 10th-century Arabic writer Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani, Abū al-Farāj al-Isfahānī (also known as al-Is ...

'', a jealous rival musician once untuned the strings of Barbad's lute during a royal banquet. Upon returning to perform, Barbad began to play; royal rules forbade the tuning instruments in the Shahanshah's presence, but Barbad's skill was such that he could adapt to the untuned strings and play the pieces regardless. Al-Isfahani attributed this story to Ishaq al-Mawsili

Ishaq al-Mawsili (; 767/772 – March 850) was an Arab musician of Persian origin active as a composer, singer and music theorist. The leading musician of his time in the Abbasid Caliphate, he served under six successive Abbasid caliphs: Haru ...

(776–856)—a renowned minstrel under Harun al-Rashid

Abū Jaʿfar Hārūn ibn Muḥammad ar-Rāshīd (), or simply Hārūn ibn al-Mahdī (; or 766 – 24 March 809), famously known as Hārūn al-Rāshīd (), was the fifth Abbasid caliph of the Abbasid Caliphate, reigning from September 786 unti ...

—who purportedly relayed the story to friends.

Among the most popular legends about Barbad involves Khosrow's beloved horse Shabdiz. In this story, Khosrow declared that when Shabdiz died, anyone who announced the news would be executed. Upon Shabdiz's death, no members of the court wished to risk conveying the news. To resolve the issue, Barbad sang a sad song, and Khosrow, understanding the purpose of the song, stated "Shabdiz is dead"; Barbad responded "Yes and it is your majesty who announced it", thereby preventing any possibility of death.

This story was relayed earliest by the poet Khaled ibn Fayyaz ( ), with later accounts by al-Tha'alibi and the 13th-century writer Zakariya al-Qazwini

Zakariyya' al-Qazwini ( , ), also known as Qazvini (), (born in Qazvin, Iran, and died 1283), was a Cosmography, cosmographer and Geography in medieval Islam, geographer.

He belonged to a family of jurists originally descended from Anas bin Mal ...

. Many similar ancient stories originated in Iran, Turkey and Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

that pertain to musicians using music to express the death of a ruler's horse, as to avoid the ruler's wrath against the announcer. Various pieces for the Khwarazm

Khwarazm (; ; , ''Xwârazm'' or ''Xârazm'') or Chorasmia () is a large oasis region on the Amu Darya river delta in western Central Asia, bordered on the north by the (former) Aral Sea, on the east by the Kyzylkum Desert, on the south by th ...

''dutar

The ''dutar'' (also ''Dotara, dotar''; ; ; ; ; ; ; ) is a traditional Iranian long-necked two-stringed lute found in Iran and Central Asia.

Its name comes from the Persian language, Persian word for "two strings", دوتار ''do tār'' (< � ...

'', Kyrgyz ''komuz

The komuz or qomuz ( , , ) is an ancient fretless string instrument used in Central Asian music, related to certain other Turkic string instruments, the Mongolian tovshuur, and the lute.

The instrument can be found in Turkic ethnic groups, ...

'' and Kazakh ''dombra

The dombra, also known as dombyra (; ) is a long-necked musical string instrument used by the Kazakhs, Hazaras, Uzbeks, Tajiks, Nogais, Bashkirs, and Tatars in their traditional folk music. The dombra shares certain characteristics with the ko ...

'' relay equivalent stories. Tafazzoli asserts that the story demonstrates Barbad's unique influence on Khosrow, while musicologist Lloyd Miller suggest that this and similar stories suggest that music and musicians in general exerted a significant influence on their political leaders.

Death

Like his birthplace, there are conflicting accounts surrounding the final years of Barbad's life. According to Ferdowsi, upon the murder of Khosrow byKavad II

Kavad II () was the Sasanian King of Kings () of Iran briefly in 628.

Born Sheroe, he was the son of Khosrow II () and Maria. With help from different factions of the nobility, Sheroe overthrew his father in a coup d'état in 628. At this junct ...

, Barbad rushed from Jahrom to the capital of Ctesiphon. After arriving he sang elegies

An elegy is a poem of serious reflection, and in English literature usually a lament for the dead. However, according to ''The Oxford Handbook of the Elegy'', "for all of its pervasiveness ... the 'elegy' remains remarkably ill defined: sometime ...

, cut off his fingers and burned his instruments out of respect. Al-Tha'alibi's account holds that Sarkash, who had remained at the court since being ousted from the chief minstrel position, poisoned Barbad. The 9th-century geographer Ibn Khordadbeh

Abu'l-Qasim Ubaydallah ibn Abdallah ibn Khordadbeh (; 820/825–913), commonly known as Ibn Khordadbeh (also spelled Ibn Khurradadhbih; ), was a high-ranking bureaucrat and geographer of Persian descent in the Abbasid Caliphate. He is the aut ...

's ''Kitāb al-lahw wa-l-malahi'', however, records the opposite, stating that Barbad poisoned Sarkash but was spared from Khosrow's punishment by way of a "witty remark". The 9th-century scholar Ibn Qutaybah

Abū Muḥammad ʿAbd Allāh ibn Muslim ibn Qutayba al-Dīnawarī al-Marwazī better known simply as Ibn Qutaybah (; c. 828 – 13 November 889 CE/213 – 15 Rajab 276 AH) was an Islamic scholar of Persian people, Persian descent. He served as a q ...

's ''‘Uyūn al-Akhbār'' and the 10th-century poet Ibn Abd Rabbih

Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn ʿAbd Rabbih (; 860–940) was an Arab writer and poet widely known as the author of ''al-ʿIqd al-Farīd'' (''The Unique Necklace'').

Biography

He was born in Cordova, now in Spain, and descended from a freed slave of ...

's ''al-ʿIqd al-Farīd

''al-ʿIqd al-Farīd'' (''The Unique Necklace'', ) is an anthology attempting to encompass 'all that a well-informed person had to know in order to pass in society as a cultured and refined individual' (or ''Adab (literature), adab''), composed b ...

'' state that Barbad was killed by a different musician, variously recorded as Yošt, Rabūst, Rošk and Zīwešt.

Music and poetry

Barbad was active as a musician-poet,lute

A lute ( or ) is any plucked string instrument with a neck (music), neck and a deep round back enclosing a hollow cavity, usually with a sound hole or opening in the body. It may be either fretted or unfretted.

More specifically, the term "lu ...

nist, music theorist

Music theory is the study of theoretical frameworks for understanding the practices and possibilities of music. '' The Oxford Companion to Music'' describes three interrelated uses of the term "music theory": The first is the " rudiments", that ...

and composer. His compositions included panegyric

A panegyric ( or ) is a formal public speech or written verse, delivered in high praise of a person or thing. The original panegyrics were speeches delivered at public events in ancient Athens.

Etymology

The word originated as a compound of - ' ...

s, elegies

An elegy is a poem of serious reflection, and in English literature usually a lament for the dead. However, according to ''The Oxford Handbook of the Elegy'', "for all of its pervasiveness ... the 'elegy' remains remarkably ill defined: sometime ...

and verses. These were performed by himself at festivals such as Nowruz

Nowruz (, , ()

, ()

, ()

, ()

, Kurdish language, Kurdish: ()

, ()

, ()

, ()

,

,

,

, ()

,

, ) is the Iranian or Persian New Year. Historically, it has been observed by Iranian peoples, but is now celebrated by many ...

and Mehregan

Mehregan () or Jashn-e Mehr ( ''Mithra Festival'') is a Zoroastrianism, Zoroastrian and Iranian peoples, Iranian festival celebrated to honor the yazata Mithra (), which is responsible for friendship, affection and love.

Name

"Mehregan" is ...

, as well as state banquets and victory celebrations. While none of the compositions are extant, the names have survived for some, and they suggest a wide variety in the topics he musically engaged with. The ethnomusicologist Hormoz Farhat

Hormoz Farhat (; 9 August 1928 – 16 August 2021) was a Persian-American composer and ethnomusicologist who spent much of his career in Dublin, Ireland. An emeritus professor of music, he was a fellow of Trinity College, Dublin. Described by ...

has tentatively sorted them into different groupings: epic forms based on historical events, ''kin-i Iraj

Iraj (; Pahlavi: ērič; from Avestan: , literally "Aryan") is the seventh Shah of the Pishdadian dynasty, depicted in the ''Shahnameh''. Based on Iranian mythology, he is the youngest son of Fereydun. He was killed by his brothers Salm and ...

'' (), ''kin-i siavash'' (), and ''Taxt-i Ardashir

Ardeshir, Ardashir or Ardasher may refer to:

Throne name of several rulers

* Artaxerxes (disambiguation), the Hellenized form of Ardeshir

* Ardashir Orontid, ''r.'' 5th century BC, Armenian king from the Orontid dynasty

* Ardashir I, ''r.'' 224– ...

'' (); songs connected to the Sasanian royal court, ''Bagh-i shirin'' (), ''Bagh-i Shahryar'' (), and ''haft Ganj'' (); and "compositions of a descriptive nature", ''roshan charagh'' (). According to both scholars Ibn al-Faqih and the 13th-century geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi

Yāqūt Shihāb al-Dīn ibn-ʿAbdullāh al-Rūmī al-Ḥamawī (1179–1229) () was a Muslim scholar of Byzantine ancestry active during the late Abbasid period (12th–13th centuries). He is known for his , an influential work on geography con ...

, Barbad wrote ''Bag-e nakjiran'' () for workers who had recently finished the gardens of Qasr-e Shirin

Qasr-e Shirin (, is a city in the Central District of Qasr-e Shirin County, Kermanshah province, Iran, serving as capital of both the county and the district. Its population in 2016 was 18,473. It is a Free-trade zone (FTZ) and is populated ...

.

A single poem by Barbad survives, though in a quoted state from the ''Kitab al-lahw wa al-malahi'' by Ibn Khordadbeh. The work is a 3-hemistich

A hemistich (; via Latin from Greek , from "half" and "verse") is a half-line of verse, followed and preceded by a caesura, that makes up a single overall prosodic or verse unit. In Latin and Greek poetry, the hemistich is generally confined ...

panegyric in Middle Persian, but with an Arabic script

The Arabic script is the writing system used for Arabic (Arabic alphabet) and several other languages of Asia and Africa. It is the second-most widely used alphabetic writing system in the world (after the Latin script), the second-most widel ...

; none of its music is extant. The poem is as follows:

Christensen suggested in 1936 that the text ''Khvarshēdh ī rōshan'' () is from a poem that was written and performed by Barbad himself or another musician-poet of his time. The text is found in a group of Manichaean

Manichaeism (; in ; ) is an endangered former major world religion currently only practiced in China around Cao'an,R. van den Broek, Wouter J. Hanegraaff ''Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times''. SUNY Press, 1998 p. 37 found ...

manuscripts in Turpan

Turpan () or Turfan ( zh, s=吐鲁番) is a prefecture-level city located in the east of the Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of Xinjiang, China. It has an area of and a population of 693,988 (2020). The historical center of the ...

, Xinjiang

Xinjiang,; , SASM/GNC romanization, SASM/GNC: Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Sinkiang, officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People' ...

, China and is written in Middle Persian, which Barbad would have used. It has four 11-syllable lines and its title recalls the Sasanian melody ''Arāyishn ī khvarshēdh'' ().

Barbad is traditionally regarded as the inventor of numerous aspects of Persian music theory and practice. Al-Tha'alibi first credited him with creating an organized modal system of , known variously as ''xosrovani'' (), ''Haft Ḵosravāni'', or ''khosravani''. This attribution is later repeated by scholars such as al-Masudi

al-Masʿūdī (full name , ), –956, was a historian, geographer and traveler. He is sometimes referred to as the "Herodotus of the Arabs". A polymath and prolific author of over twenty works on theology, history (Islamic and universal), geo ...

and Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi

Qotb al-Din Mahmoud b. Zia al-Din Mas'ud b. Mosleh Shirazi (; 1236–1311) was a 13th-century Persian polymath and poet who made contributions to astronomy, mathematics, medicine, physics, music theory, philosophy and Sufism.Sayyed ʿAbd-Allā ...

. From these royal modes, Barbad created , and 360 melodies

A melody (), also tune, voice, or line, is a linear succession of musical tones that the listener perceives as a single entity. In its most literal sense, a melody is a combination of pitch and rhythm, while more figuratively, the term ca ...

(''dastan''). The structure of seven, 30 and 360 variations corresponds to the number of days, weeks and months of the Zoroastrian calendar

Adherents of Zoroastrianism use three distinct versions of traditional calendars for Zoroastrian festivals, liturgical purposes. Those all derive from Middle Ages, medieval Iranian calendars and ultimately are based on the Babylonian calendar a ...

. Farhat notes that the exact reason for this is not known, though according to the 14th-century poet Hamdallah Mustawfi

Hamdallah Mustawfi Qazvini (; 1281 – after 1339/40) was a Persian official, historian, geographer and poet. He lived during the last era of the Mongol Ilkhanate, and the interregnum that followed.

A native of Qazvin, Mustawfi belonged to fami ...

's ''Tarikh-i guzida

The ''Tarikh-i guzida'' (also spelled ''Tarikh-e Gozideh'' (, "Excerpt history"), is a compendium of Islamic history from the creation of the world until 1329, written by Hamdallah Mustawfi and finished in 1330.''E.J. Brill's first Encyclopedia of ...

'', Barbad sang one of the 360 melodies each day for the Shahanshah. Al-Tha'alibi recorded that the seven royal modes were still in use during his lifetime, from 961 to 1039. Further information on the nature of these subjects, theories or compositions has not survived. In her analysis of the historical and literary sources concerning Barbad, musicologist Firoozeh Khazrai stated that "until a new independent source on the subject comes to light, many of these attributions should be regarded as authorial inventions". She noted that many of the attributions to Barbad date centuries after his death and the 30 modes in particular are first connected to Barbad by Nizami, who lived in the 12th century. In addition, in his divan

A divan or diwan (, ''dīvān''; from Sumerian ''dub'', clay tablet) was a high government ministry in various Islamic states, or its chief official (see ''dewan'').

Etymology

The word, recorded in English since 1586, meaning "Oriental cou ...

(collection of poems), the 11th-century poet Manuchehri

Abu Najm Aḥmad ibn Qauṣ ibn Aḥmad Manūčihrī (), a.k.a. Manuchehri Dāmghānī (fl. 1031–1040), was an eleventh-century court poet in Persia and in the estimation of J. W. Clinton, 'the third and last (after ʿUnṣurī and Farrukhī) o ...

names a few of the modes that Nizami mentioned but does not associate them with Barbad, even though he references the Sasanian musician elsewhere.

Reputation

Barbad's lute was the four-stringed '' barbat''. It had been popular in his time, but no traces of the instrument survive and it was eventually substituted for the

Barbad's lute was the four-stringed '' barbat''. It had been popular in his time, but no traces of the instrument survive and it was eventually substituted for the oud

The oud ( ; , ) is a Middle Eastern short-neck lute-type, pear-shaped, fretless stringed instrument (a chordophone in the Hornbostel–Sachs classification of instruments), usually with 11 strings grouped in six courses, but some models have ...

. The musicologists Jean During

Jean During (born 1947) is a French musician and ethnomusicologist specialising in music from the nations of the East especially Iran, Central Asia, Afghanistan and Azerbaijan. A commentator on the Middle Eastern and South Asian cultures, he is t ...

and Zia Mirabdolbaghi note that despite the instrument's gradual disuse, "the term ''barbat'' survived for centuries, through classical poetry, as a symbol of the golden age of the Persian musical tradition, served by artists such as Bārbad." Later sources regularly praise Barbad and some offer him the epitaph

An epitaph (; ) is a short text honoring a deceased person. Strictly speaking, it refers to text that is inscribed on a tombstone or plaque, but it may also be used in a figurative sense. Some epitaphs are specified by the person themselves be ...

as the "founder of Persian music". He is regarded as the most significant musician of his time, being among the major figures in the history of Iranian/Persian music. In ''Sharh bar Kitāb al-adwar'', the 14th-century writer al-Sharif al-Jurjani

Ali ibn Mohammed al-Jurjani (1339–1414) (Persian ) was a Persian encyclopedic writer, scientist, and traditionalist theologian. He is referred to as "al-Sayyid al-Sharif" in sources due to his alleged descent from Ali ibn Abi Taleb. He was bor ...

—whom the work is attributed to—says:

The preponderance and frequent transmission of stories involving Barbad attest to his popularity long after his death. In modern-day Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan

Tajikistan, officially the Republic of Tajikistan, is a landlocked country in Central Asia. Dushanbe is the capital city, capital and most populous city. Tajikistan borders Afghanistan to the Afghanistan–Tajikistan border, south, Uzbekistan to ...

, Barbad continues to be a celebrated figure. In 1989 and 1990 the cultural establishment of the Tajik

Tajik, Tajikistan or Tajikistani may refer to. Someone or something related to Tajikistan:

Tajik

* Tajiks, an ethnic group in Tajikistan, Afghanistan and Uzbekistan

* Tajik language, the official language of Tajikistan

* Tajik alphabet, Alphabet u ...

government encouraged their people to find pride in Barbad's achievements; the panegyrics given for Barbad are part of a larger effort by the Tajik government to pass off the "achievements of pre-Islamic Iranian civilization" as Tajik ones. The largest musical hall of Dushanbe

Dushanbe is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Tajikistan. , Dushanbe had a population of 1,564,700, with this population being largely Tajiks, Tajik. Until 1929, the city was known in Russian as Dyushambe, and from 1929 to 1961 as St ...

, Tajikistan, is named "Kokhi Borbad" after Barbad.

Musicologist Firoozeh Khazrai sums up Barbad's legacy as such:

Shahnameh

The ''Shahnameh'' (, ), also transliterated ''Shahnama'', is a long epic poem written by the Persian literature, Persian poet Ferdowsi between and 1010 CE and is the national epic of Greater Iran. Consisting of some 50,000 distichs or couple ...

'' with Barbad in a tree in the top right. The work is kept at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) is an art museum located on Wilshire Boulevard in the Miracle Mile vicinity of Los Angeles. LACMA is on Museum Row, adjacent to the La Brea Tar Pits (George C. Page Museum).

LACMA was founded in 1961 ...

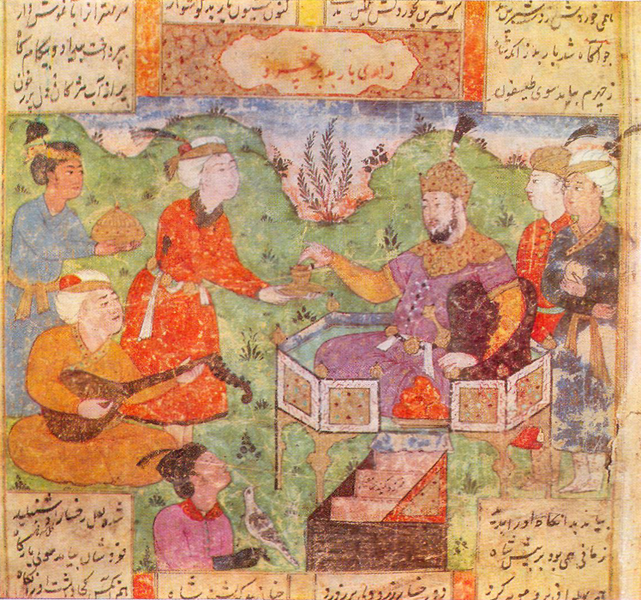

File:Khalili Collection Islamic Art MSS 1030-731a.jpg, 1535 painting of Barbad (pictured in the tree), attributed to

References

Notes

Citations

Sources

:Books * * ** ** ** * * * * * * * :Articles * * * * * ** ** * * * * * :Web * *Further reading

* * * * *External links

"Barbad and Nakisā"

a song inspired by Barbad performed by the

Tanbur

The term ''Tanbur'' can refer to various long-necked string instruments originating in Mesopotamia, Southern or Central Asia. According to the ''New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'', "terminology presents a complicated situation. Nowa ...

player Nur ʿAli Elāhi on ''Encyclopædia Iranica

''Encyclopædia Iranica'' is a project whose goal is to create a comprehensive and authoritative English-language encyclopedia about the history, culture, and civilization of Iranian peoples from prehistory to modern times.

Scope

The ''Encyc ...

''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Barbad

Musicians from the Sasanian Empire

Year of birth unknown

Year of death unknown

Shahnameh characters

People from Jahrom

People from Merv

Iranian musicians

Eastern lutes players

7th-century Iranian people

7th-century musicians