Austronesians on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Austronesian people, sometimes referred to as Austronesian-speaking peoples, are a large group of peoples who have settled in

The term "Austronesian", or more accurately "Austronesian-speaking peoples", came to refer to people who speak the languages of the Austronesian language family. Some authors, however, object to the use of the term to refer to people, as they question whether there really is any biological or cultural shared ancestry between all Austronesian-speaking groups.According to the anthropologist Wilhelm Solheim II: "I emphasize again, as I have done in many other articles, that 'Austronesian' is a linguistic term and is the name of a super language family. It should never be used as a name for a people, genetically speaking, or a culture. To refer to people who speak an Austronesian language, the phrase 'Austronesian-speaking people' should be used." ''Origins of the Filipinos and Their Languages'' (January 2006) This is especially true for authors who reject the prevailing "Out of Taiwan" hypothesis and instead offer scenarios where the Austronesian languages spread among preexisting static populations through borrowing or convergence, with little or no population movements.

The term "Austronesian", or more accurately "Austronesian-speaking peoples", came to refer to people who speak the languages of the Austronesian language family. Some authors, however, object to the use of the term to refer to people, as they question whether there really is any biological or cultural shared ancestry between all Austronesian-speaking groups.According to the anthropologist Wilhelm Solheim II: "I emphasize again, as I have done in many other articles, that 'Austronesian' is a linguistic term and is the name of a super language family. It should never be used as a name for a people, genetically speaking, or a culture. To refer to people who speak an Austronesian language, the phrase 'Austronesian-speaking people' should be used." ''Origins of the Filipinos and Their Languages'' (January 2006) This is especially true for authors who reject the prevailing "Out of Taiwan" hypothesis and instead offer scenarios where the Austronesian languages spread among preexisting static populations through borrowing or convergence, with little or no population movements.

Despite these objections, the general consensus is that the archeological, cultural, genetic, and especially linguistic evidence all separately indicate varying degrees of shared ancestry among Austronesian-speaking peoples that justifies their treatment as a "

Despite these objections, the general consensus is that the archeological, cultural, genetic, and especially linguistic evidence all separately indicate varying degrees of shared ancestry among Austronesian-speaking peoples that justifies their treatment as a "

Island Southeast Asia was settled by modern humans in the

Island Southeast Asia was settled by modern humans in the  The lowered sea levels of the

The lowered sea levels of the  In modern literature, descendants of these groups, located in Island Southeast Asia west of

In modern literature, descendants of these groups, located in Island Southeast Asia west of

Several authors have also proposed that Kra-Dai speakers may actually be an ancient daughter subgroup of Austronesians that migrated back to the

Several authors have also proposed that Kra-Dai speakers may actually be an ancient daughter subgroup of Austronesians that migrated back to the  The Sino-Austronesian hypothesis, on the other hand, is a relatively new hypothesis by

The Sino-Austronesian hypothesis, on the other hand, is a relatively new hypothesis by

Suppose we are wrong about the Austronesian settlement of Taiwan?

'' m.s. Blench considers the Austronesians in Taiwan to have been a

Seagoing

Seagoing  Early researchers like Heine-Geldern (1932) and Hornell (1943) once believed that catamarans evolved from outrigger canoes, but modern authors specializing in Austronesian cultures, like Doran (1981) and Mahdi (1988), now believe it to be the opposite.

Two canoes bound together developed directly from minimal raft technologies of two logs tied together. Over time, the double-hulled canoe form developed into the asymmetric double canoe, where one hull is smaller than the other. Eventually the smaller hull became the prototype outrigger, giving way to the single outrigger canoe, then to the reversible single outrigger canoe. Finally, the single outrigger types developed into the double outrigger canoe (or trimarans).

This would also explain why older Austronesian populations in Island Southeast Asia tend to favor double outrigger canoes, as it keeps the boats stable when Tacking (sailing), tacking. However, there are small regions where catamarans and single-outrigger canoes are still used. In contrast, more distant outlying descendant populations in

Early researchers like Heine-Geldern (1932) and Hornell (1943) once believed that catamarans evolved from outrigger canoes, but modern authors specializing in Austronesian cultures, like Doran (1981) and Mahdi (1988), now believe it to be the opposite.

Two canoes bound together developed directly from minimal raft technologies of two logs tied together. Over time, the double-hulled canoe form developed into the asymmetric double canoe, where one hull is smaller than the other. Eventually the smaller hull became the prototype outrigger, giving way to the single outrigger canoe, then to the reversible single outrigger canoe. Finally, the single outrigger types developed into the double outrigger canoe (or trimarans).

This would also explain why older Austronesian populations in Island Southeast Asia tend to favor double outrigger canoes, as it keeps the boats stable when Tacking (sailing), tacking. However, there are small regions where catamarans and single-outrigger canoes are still used. In contrast, more distant outlying descendant populations in  The ancient

The ancient

Beinan Taitung Taiwan Aboriginal-Stilt-House-01.jpg, Aboriginal Taiwanese architecture

Philippinen Basilan seezigeuner ph03p42.jpg,

This type of pottery dispersed south and southwest to the rest of Island Southeast Asia. The eastward and southward branches of the migrations converged in

This type of pottery dispersed south and southwest to the rest of Island Southeast Asia. The eastward and southward branches of the migrations converged in

Jaw harps, flutes, and a slit drum from the Maranao, Molbog, and Sama people (Philippines).jpg, ''Kubing''

Lingling-o-X3.jpg, Igorot people, Igorot gold double-headed pendants (''lingling-o'') from the Philippines

Bicephalous pendant (Jade), Artefacts of Phu Hoa site(Dong Nai province) 01.jpg, Sa Huỳnh culture, Sa Huỳnh white jade double-headed pendant from Vietnam

Ear pendant (peka peka), Maori people, Honolulu Museum of Art, 3351.JPG, Māori Pounamu, greenstone double-headed pendant (''pekapeka'') from New Zealand

Pounamu 3.jpg, Māori ''hei matau'' jade pendant

The ancestral pre-Austronesian Liangzhu culture (3400–2250 BCE) of the

COLLECTIE TROPENMUSEUM Twee Europese dames en een man staan voor een afgodsbeeld te Napu Menado TMnr 10000852.jpg, ''Watu Molindo'' ("the entertainer stone"), one of the megaliths in Bada Valley, Central Sulawesi, Indonesia, usually found near megalithic stone vats known as ''kalamba''.

GuaTewet tree of life-LHFage.jpg, Hand stencils in the "Tree of Life" cave painting in Gua Tewet,

The Megalithic Culture is mostly limited to western Island Southeast Asia, with the greatest concentration being western Indonesia. While most sites are not dated, the age ranges of dating sites are between the 2nd and 16th centuries CE. They are divided into two phases: The first is an older megalithic tradition associated with the Neolithic Austronesian rectangular axe culture (2,500 to 1,500 BCE), while the second is the 3rd- or 4th-century BCE megalithic tradition associated with the (non-Austronesian) Dong Son culture of Vietnam. Prasetyo (2006) suggests that the megalithic traditions are not originally Austronesian but rather innovations acquired through trade with India and China, but this has little to no evidence in the intervening regions in Thailand, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

The Austronesian Painting Traditions are the most common types of rock art in Island Southeast Asia. They consist of scenes and pictograms typically found in rock shelters and caves near coastal areas. They are characteristically rendered in red ocher pigments for the earlier forms, later sometimes superseded by paintings done in black charcoal pigments. Their sites are mostly clustered in Eastern Indonesia and Island Melanesia, although a few examples can be found in the rest of Island Southeast Asia. Their occurrence has a high correlation to Austronesian-speaking areas, further evidenced by the appearance of bronze artifacts in the paintings. They are mostly found near the coastlines. Their common motifs include hand stencils, "sun-ray" designs, boats, and active human figures with headdresses or weapons and other paraphernalia. They also feature geometric motifs similar to those of the Austronesian Engraving Style. Some paintings are also associated with traces of human burials and funerary rites, including ship burials. The representations of boats themselves are believed to be connected to the widespread "ship of the dead" Austronesian funerary practices.

The earliest APT site dated is from Vanuatu and was found to be around 3,000 BP, corresponding to the initial migration wave of the Austronesians. These early sites are largely characterized by face motifs and hand stencils. Later sites, from 1,500 BP onwards, however, begin to show regional divergence in their art styles. APT can be readily distinguished from older  The easternmost islands of Island Melanesia (Vanuatu, Fiji, and New Caledonia) are considered part of Remote Oceania, as they are beyond the inter-island visibility threshold. These island groups begin to show divergence from the APT and AES traditions of

The easternmost islands of Island Melanesia (Vanuatu, Fiji, and New Caledonia) are considered part of Remote Oceania, as they are beyond the inter-island visibility threshold. These island groups begin to show divergence from the APT and AES traditions of

Among the Indigenous Taiwanese, tattoos were present for both men and women. Among the Atayal, facial tattoos were dominant. They indicated maturity and skill in weaving and farming for women and skill in hunting and battle for men. As in most of Austronesia, tattooing traditions in Taiwan have largely disappeared due to the Sinicization of native peoples after the Taiwan under Qing rule, Chinese colonization of the island in the 17th century, as well as conversion to Christianity. Most of the remaining tattoos are only found among elders.

One of the earliest descriptions of Austronesian tattoos by Europeans was during the 16th-century History of the Philippines (1521–1898), Spanish expeditions to the Philippines, beginning with the Magellan expedition, first voyage of circumnavigation by Ferdinand Magellan. The Spanish encountered the heavily tattooed Visayan people in the Visayas, Visayas Islands, whom they named the ''Pintados'' (Spanish for "the painted ones"). However, Philippine tattooing traditions (''batok'') have mostly been lost as the natives of the islands converted to Christianity and

Among the Indigenous Taiwanese, tattoos were present for both men and women. Among the Atayal, facial tattoos were dominant. They indicated maturity and skill in weaving and farming for women and skill in hunting and battle for men. As in most of Austronesia, tattooing traditions in Taiwan have largely disappeared due to the Sinicization of native peoples after the Taiwan under Qing rule, Chinese colonization of the island in the 17th century, as well as conversion to Christianity. Most of the remaining tattoos are only found among elders.

One of the earliest descriptions of Austronesian tattoos by Europeans was during the 16th-century History of the Philippines (1521–1898), Spanish expeditions to the Philippines, beginning with the Magellan expedition, first voyage of circumnavigation by Ferdinand Magellan. The Spanish encountered the heavily tattooed Visayan people in the Visayas, Visayas Islands, whom they named the ''Pintados'' (Spanish for "the painted ones"). However, Philippine tattooing traditions (''batok'') have mostly been lost as the natives of the islands converted to Christianity and

Teeth blackening was the custom of dyeing one's teeth black with various tannin-rich plant dyes. It was practiced throughout almost the entire range of Austronesia, including Island Southeast Asia, Madagascar, Micronesia, and Island Melanesia, reaching as far east as Malaita. However, it was absent in Polynesia. It also existed in non-Austronesian populations in Mainland Southeast Asia and Japan. The practice was primarily preventative, as it reduced the chances of developing tooth decay, similar to modern dental sealants. It also had cultural significance and was seen as beautiful. A common sentiment was that blackened teeth separated humans from animals.

Teeth blackening was often done in conjunction with other modifications to the teeth associated with beauty standards, including dental evulsion and Teeth filing, filing.

Teeth blackening was the custom of dyeing one's teeth black with various tannin-rich plant dyes. It was practiced throughout almost the entire range of Austronesia, including Island Southeast Asia, Madagascar, Micronesia, and Island Melanesia, reaching as far east as Malaita. However, it was absent in Polynesia. It also existed in non-Austronesian populations in Mainland Southeast Asia and Japan. The practice was primarily preventative, as it reduced the chances of developing tooth decay, similar to modern dental sealants. It also had cultural significance and was seen as beautiful. A common sentiment was that blackened teeth separated humans from animals.

Teeth blackening was often done in conjunction with other modifications to the teeth associated with beauty standards, including dental evulsion and Teeth filing, filing.

Poteau funéraire, aloalo, détail, Musée du quai Branly.jpg, ''Aloalo'' funerary pole of the Sakalava people of Madagascar

Nias Ahnenfiguren Museum Rietberg RIN 403.jpg, ''Adu zatua'' ancestor carvings of the Nias people of western Indonesia

Anitos of Northern tribes (c. 1900, Philippines).jpg, ''Anito, Taotao'' carvings of ''anito'' ancestor spirits from the Ifugao people, Philippines

Tikimarquesas.jpg, Stone ''tiki'' from Hiva Oa, Marquesas

Kii at Puuhonua O Honaunau 01.jpg, ''Ki'i'' carving at Puuhonua o Hōnaunau National Historical Park, Puuhonua o Hōnaunau, Hawaii

Maori wooden carvings in the Rotorua Museum-2.jpg, Māori ''Poupou (architecture), poupou'' from the Ruato tomb of Rotorua

AhuTongariki.JPG, ''Moai'' in Ahu Tongariki, Rapa Nui

KITLV 87643 - Isidore van Kinsbergen - Sculptures at Artja Domas near Buitenzorg - Before 1900.tif, Sundanese, specifically Baduy people, Baduy ''Arca Domas'' (eight hundred sculptures) near Bogor, Indonesia.

Tana Toraja, Tampangallo, coffins and tau taus (6823243058).jpg, Toraja ''tau tau'' (wooden statue of the deceased) in South Sulawesi, Indonesia (also note the boat-shaped coffins)

Balinese Traditional House Shrines 1452.jpg, Balinese small familial house shrines to Veneration of the dead, honor the households' ancestors in Indonesia

Rongorongo B-v Aruku-Kurenga (color) edit1.jpg, Tablet B of rongorongo, an undeciphered system of glyphs from

With the possible exception of rongorongo on  Oral tradition holds that the ruling classes were the only ones who could read the tablets, and the ability to decipher the tablets was lost along with them. Numerous attempts have been made to read the tablets, starting from a few years after their discovery. But to this day, none have proven successful. Some authors have proposed that rongorongo may have been an attempt to imitate European script after the idea of writing was introduced during the "signing" of the History of Easter Island#European contacts, 1770 Spanish Treaty of Annexation or through knowledge of European writing acquired elsewhere. They cite various reasons, including the lack of attestation of rongorongo prior to the 1860s, the clearly more recent provenance of some of the tablets, the lack of antecedents, and the lack of additional archaeological evidence since its discovery. Others argue that it was merely a mnemonic list of symbols meant to guide incantations. Whether rongorongo is merely an example of trans-cultural diffusion or a true indigenous Austronesian writing system (and one of the few independent inventions of writing in human history) remains unknown.

In Southeast Asia, the first true writing systems of pre-modern Austronesian cultures were all derived from the Grantha script, Grantha and Pallava script, Pallava Brahmic scripts, all of which are abugidas from South India. Various forms of abugidas spread throughout Austronesian cultures in Southeast Asia as kingdoms became Greater India#Indianization of South East Asia, Indianized through early maritime trading. The oldest use of abugida scripts in Austronesian cultures are 4th-century stone inscriptions written in Cham script, Cham, from Vietnam. There are numerous other Brahmic-derived writing systems among Southeast Asian Austronesians, usually specific to a certain ethnic group. Notable examples include Balinese script, Balinese, Batak script, Batak, Baybayin, Buhid script, Buhid, Hanunuo script, Hanunó'o, Javanese script, Javanese, Kulitan alphabet, Kulitan, Lontara script, Lontara, Old Kawi, Rejang script, Rejang, Rencong script, Rencong, Sundanese script, Sundanese, and Tagbanwa script, Tagbanwa. They vary from having letters with rounded shapes to characters with sharp cuneiform-like angles, as a result of the difference in writing mediums, with the former being ideal for writing on soft leaves and the latter on bamboo panels. The use of the scripts ranged from mundane records to encoding esoteric knowledge on magico-religious rituals and folk medicine.

In regions that converted to Islam, abjads derived from the Arabic script started replacing the earlier abugidas at around the 13th century in Southeast Asia.

Oral tradition holds that the ruling classes were the only ones who could read the tablets, and the ability to decipher the tablets was lost along with them. Numerous attempts have been made to read the tablets, starting from a few years after their discovery. But to this day, none have proven successful. Some authors have proposed that rongorongo may have been an attempt to imitate European script after the idea of writing was introduced during the "signing" of the History of Easter Island#European contacts, 1770 Spanish Treaty of Annexation or through knowledge of European writing acquired elsewhere. They cite various reasons, including the lack of attestation of rongorongo prior to the 1860s, the clearly more recent provenance of some of the tablets, the lack of antecedents, and the lack of additional archaeological evidence since its discovery. Others argue that it was merely a mnemonic list of symbols meant to guide incantations. Whether rongorongo is merely an example of trans-cultural diffusion or a true indigenous Austronesian writing system (and one of the few independent inventions of writing in human history) remains unknown.

In Southeast Asia, the first true writing systems of pre-modern Austronesian cultures were all derived from the Grantha script, Grantha and Pallava script, Pallava Brahmic scripts, all of which are abugidas from South India. Various forms of abugidas spread throughout Austronesian cultures in Southeast Asia as kingdoms became Greater India#Indianization of South East Asia, Indianized through early maritime trading. The oldest use of abugida scripts in Austronesian cultures are 4th-century stone inscriptions written in Cham script, Cham, from Vietnam. There are numerous other Brahmic-derived writing systems among Southeast Asian Austronesians, usually specific to a certain ethnic group. Notable examples include Balinese script, Balinese, Batak script, Batak, Baybayin, Buhid script, Buhid, Hanunuo script, Hanunó'o, Javanese script, Javanese, Kulitan alphabet, Kulitan, Lontara script, Lontara, Old Kawi, Rejang script, Rejang, Rencong script, Rencong, Sundanese script, Sundanese, and Tagbanwa script, Tagbanwa. They vary from having letters with rounded shapes to characters with sharp cuneiform-like angles, as a result of the difference in writing mediums, with the former being ideal for writing on soft leaves and the latter on bamboo panels. The use of the scripts ranged from mundane records to encoding esoteric knowledge on magico-religious rituals and folk medicine.

In regions that converted to Islam, abjads derived from the Arabic script started replacing the earlier abugidas at around the 13th century in Southeast Asia.

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

, maritime Southeast Asia

Maritime Southeast Asia comprises the Southeast Asian countries of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and East Timor.

The terms Island Southeast Asia and Insular Southeast Asia are sometimes given the same meaning as ...

, parts of mainland Southeast Asia

Mainland Southeast Asia (historically known as Indochina and the Indochinese Peninsula) is the continental portion of Southeast Asia. It lies east of the Indian subcontinent and south of Mainland China and is bordered by the Indian Ocean to th ...

, Micronesia

Micronesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, consisting of approximately 2,000 small islands in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean. It has a close shared cultural history with three other island regions: Maritime Southeast Asia to the west, Poly ...

, coastal New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; , fossilized , also known as Papua or historically ) is the List of islands by area, world's second-largest island, with an area of . Located in Melanesia in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is ...

, Island Melanesia

Island Melanesia is a subregion of Melanesia in Oceania.

It is located east of New Guinea island, from the Bismarck Archipelago to New Caledonia.Steadman, 2006. ''Extinction & biogeography of tropical Pacific birds''

See also Archaeology a ...

, Polynesia

Polynesia ( , ) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of more than 1,000 islands scattered over the central and southern Pacific Ocean. The indigenous people who inhabit the islands of Polynesia are called Polynesians. They have many things in ...

, and Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

that speak Austronesian languages

The Austronesian languages ( ) are a language family widely spoken throughout Maritime Southeast Asia, parts of Mainland Southeast Asia, Madagascar, the islands of the Pacific Ocean and Taiwan (by Taiwanese indigenous peoples). They are spoken ...

. They also include indigenous ethnic minorities in Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

, Cambodia

Cambodia, officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. It is bordered by Thailand to the northwest, Laos to the north, and Vietnam to the east, and has a coastline ...

, Myanmar

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and has ...

, Thailand

Thailand, officially the Kingdom of Thailand and historically known as Siam (the official name until 1939), is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. With a population of almost 66 million, it spa ...

, Hainan

Hainan is an island provinces of China, province and the southernmost province of China. It consists of the eponymous Hainan Island and various smaller islands in the South China Sea under the province's administration. The name literally mean ...

, the Comoros

The Comoros, officially the Union of the Comoros, is an archipelagic country made up of three islands in Southeastern Africa, located at the northern end of the Mozambique Channel in the Indian Ocean. Its capital and largest city is Moroni, ...

, and the Torres Strait Islands

The Torres Strait Islands are an archipelago of at least 274 small islands in the Torres Strait, a waterway separating far northern continental Australia's Cape York Peninsula and the island of New Guinea. They span an area of , but their tot ...

. The nations and territories predominantly populated by Austronesian-speaking peoples are sometimes known collectively as Austronesia.

The group originated from a prehistoric seaborne migration, known as the Austronesian expansion, from Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

, circa 3000 to 1500 BCE. Austronesians reached the Batanes Islands

Batanes, officially the Province of Batanes (; ilocano language, Ilocano: ''Probinsia ti Batanes''; , ), is an archipelagic province in the Philippines, administratively part of the Cagayan Valley regions of the Philippines, region. It is the n ...

in the northernmost Philippines by around 2200 BCE. They used sails some time before 2000 BCE. In conjunction with their use of other maritime technologies (notably catamaran

A catamaran () (informally, a "cat") is a watercraft with two parallel hull (watercraft), hulls of equal size. The wide distance between a catamaran's hulls imparts stability through resistance to rolling and overturning; no ballast is requi ...

s, outrigger boat

Outrigger boats are various watercraft featuring one or more lateral support floats known as outriggers, which are fastened to one or both sides of the main hull (watercraft), hull. They can range from small dugout (boat), dugout canoes to large ...

s, lashed-lug boats, and the crab claw sail), this enabled phases of rapid dispersal into the islands of the Indo-Pacific

The Indo-Pacific is a vast biogeographic region of Earth. In a narrow sense, sometimes known as the Indo-West Pacific or Indo-Pacific Asia, it comprises the tropical waters of the Indian Ocean, the western and central Pacific Ocean, and the ...

, culminating in the settlement of New Zealand . During the initial part of the migrations, they encountered and assimilated (or were assimilated by) the Paleolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic ( years ago) ( ), also called the Old Stone Age (), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone tools, and which represents almost the entire period of human prehist ...

populations that had migrated earlier into Maritime Southeast Asia and New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; , fossilized , also known as Papua or historically ) is the List of islands by area, world's second-largest island, with an area of . Located in Melanesia in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is ...

. They reached as far as Easter Island

Easter Island (, ; , ) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is renowned for its nearly 1,000 extant monumental statues, ...

to the east, Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

to the west, and New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

to the south. At the furthest extent, they might have also reached the Americas

The Americas, sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America and South America.''Webster's New World College Dictionary'', 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. When viewed as a sing ...

.Van Tilburg, Jo Anne. 1994. ''Easter Island: Archaeology, Ecology and Culture.'' Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution PressLangdon, Robert. The Bamboo Raft as a Key to the Introduction of the Sweet Potato in Prehistoric Polynesia, ''The Journal of Pacific History'', Vol. 36, No. 1, 2001

Aside from language, Austronesian peoples widely share cultural characteristics, including such traditions and traditional technologies as tattooing

A tattoo is a form of body modification made by inserting tattoo ink, dyes, or pigments, either indelible or temporary, into the dermis layer of the Human skin, skin to form a design. Tattoo artists create these designs using several Process of ...

, stilt houses, jade

Jade is an umbrella term for two different types of decorative rocks used for jewelry or Ornament (art), ornaments. Jade is often referred to by either of two different silicate mineral names: nephrite (a silicate of calcium and magnesium in t ...

carving, wetland agriculture, and various rock art

In archaeology, rock arts are human-made markings placed on natural surfaces, typically vertical stone surfaces. A high proportion of surviving historic and prehistoric rock art is found in caves or partly enclosed rock shelters; this type al ...

motifs. They also share domesticated plants and animals that were carried along with the migrations, including rice

Rice is a cereal grain and in its Domestication, domesticated form is the staple food of over half of the world's population, particularly in Asia and Africa. Rice is the seed of the grass species ''Oryza sativa'' (Asian rice)—or, much l ...

, bananas, coconuts, breadfruit

Breadfruit (''Artocarpus altilis'') is a species of flowering tree in the mulberry and jackfruit family ( Moraceae) believed to have been selectively bred in Polynesia from the breadnut ('' Artocarpus camansi''). Breadfruit was spread into ...

, '' Dioscorea'' yams, taro

Taro (; ''Colocasia esculenta'') is a root vegetable. It is the most widely cultivated species of several plants in the family Araceae that are used as vegetables for their corms, leaves, stems and Petiole (botany), petioles. Taro corms are a ...

, paper mulberry

The paper mulberry (''Broussonetia papyrifera'', syn. ''Morus papyrifera'' L.) is a species of flowering plant in the family Moraceae. It is native to Asia,dogs

The dog (''Canis familiaris'' or ''Canis lupus familiaris'') is a domesticated descendant of the gray wolf. Also called the domestic dog, it was selectively bred from a population of wolves during the Late Pleistocene by hunter-gatherers ...

.

History of research

The linguistic connections betweenMadagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

, Polynesia

Polynesia ( , ) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of more than 1,000 islands scattered over the central and southern Pacific Ocean. The indigenous people who inhabit the islands of Polynesia are called Polynesians. They have many things in ...

, and Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, southeastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of China, east of the Indian subcontinent, and northwest of the Mainland Au ...

, particularly the similarities between Malagasy, Malay, and Polynesian numerals

A numeral is a figure (symbol), word, or group of figures (symbols) or words denoting a number. It may refer to:

* Numeral system used in mathematics

* Numeral (linguistics), a part of speech denoting numbers (e.g. ''one'' and ''first'' in English ...

, were recognized early in the colonial era by European authors. The first formal publication on these relationships was in 1708 by Dutch Orientalist Adriaan Reland, who recognized a "common language" from Madagascar to western Polynesia, although Dutch explorer Cornelis de Houtman

Cornelis de Houtman (2 April 1565 – 11 September 1599) was a Dutch merchant seaman who commanded the first Dutch expedition to the East Indies. Although the voyage was difficult and yielded only a modest profit, Houtman showed that the ...

observed linguistic links between Madagascar and the Malay Archipelago

The Malay Archipelago is the archipelago between Mainland Southeast Asia and Australia, and is also called Insulindia or the Indo-Australian Archipelago. The name was taken from the 19th-century European concept of a Malay race, later based ...

a century earlier, in 1603. German naturalist

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

Johann Reinhold Forster

Johann Reinhold Forster (; 22 October 1729 – 9 December 1798) was a German Reformed pastor and naturalist. Born in Tczew, Dirschau, Pomeranian Voivodeship (1466–1772), Pomeranian Voivodeship, Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (now Tczew, Po ...

, who traveled with James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

on his second voyage, also recognized the similarities of Polynesian languages to those of Island Southeast Asia. In his book '' Observations Made during a Voyage round the World'' (1778), he posited that the ultimate origins of the Polynesians might have been the lowland regions of the Philippines and proposed that they arrived to the islands via long-distance voyaging.

The Spanish philologist

Philology () is the study of language in oral and written historical sources. It is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics with strong ties to etymology. Philology is also defined as the study of ...

Lorenzo Hervás

Lorenzo Hervás y Panduro was a Spanish Jesuit and philologist; born at Horcajo, 1 May 1735; died at Rome, 24 August 1809. He is one of the most important authors, together with Juan Andrés, Antonio Eximeno or Celestino Mutis, of the Spani ...

later devoted a large part of his ''Idea dell'universo'' (1778–1787) to the establishment of a language family

A language family is a group of languages related through descent from a common ancestor, called the proto-language of that family. The term ''family'' is a metaphor borrowed from biology, with the tree model used in historical linguistics ...

linking the Malay Peninsula

The Malay Peninsula is located in Mainland Southeast Asia. The landmass runs approximately north–south, and at its terminus, it is the southernmost point of the Asian continental mainland. The area contains Peninsular Malaysia, Southern Tha ...

, the Maldives

The Maldives, officially the Republic of Maldives, and historically known as the Maldive Islands, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in South Asia located in the Indian Ocean. The Maldives is southwest of Sri Lanka and India, abou ...

, Madagascar, Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania, between the Indian Ocean, Indian and Pacific Ocean, Pacific oceans. Comprising over List of islands of Indonesia, 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, ...

(Sunda Islands

The Sunda Islands (; Tetun: ''Illa Sunda'') are a group of islands in the Indonesian Archipelago. They consist of the Greater Sunda Islands and the Lesser Sunda Islands.

Etymology

"Sunda" denotes the continental shelves or landmasses: the Sun ...

and Moluccas

The Maluku Islands ( ; , ) or the Moluccas ( ; ) are an archipelago in the eastern part of Indonesia. Tectonically they are located on the Halmahera Plate within the Molucca Sea Collision Zone. Geographically they are located in West Melanesi ...

), the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

, and the Pacific Islands

The Pacific islands are a group of islands in the Pacific Ocean. They are further categorized into three major island groups: Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Depending on the context, the term ''Pacific Islands'' may refer to one of several ...

eastward to Easter Island

Easter Island (, ; , ) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is renowned for its nearly 1,000 extant monumental statues, ...

. Multiple other authors corroborated this classification (except for the erroneous inclusion of Maldivian), and the language family came to be known as "Malayo-Polynesian", first coined by the German linguist Franz Bopp

Franz Bopp (; 14 September 1791 – 23 October 1867) was a German linguistics, linguist known for extensive and pioneering comparative linguistics, comparative work on Indo-European languages.

Early life

Bopp was born in Mainz, but the pol ...

in 1841 ( German: ''malayisch-polynesisch''). The connections between Southeast Asia, Madagascar, and the Pacific Islands were also noted by other European explorers, including the Orientalist William Marsden and the naturalist Johann Reinhold Forster

Johann Reinhold Forster (; 22 October 1729 – 9 December 1798) was a German Reformed pastor and naturalist. Born in Tczew, Dirschau, Pomeranian Voivodeship (1466–1772), Pomeranian Voivodeship, Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (now Tczew, Po ...

.

Johann Friedrich Blumenbach

Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (11 May 1752 – 22 January 1840) was a German physician, naturalist, physiologist and anthropologist. He is considered to be a main founder of zoology and anthropology as comparative, scientific disciplines. He has be ...

added Austronesians as the fifth category to his "varieties" of humans in the second edition of ''De Generis Humani Varietate Nativa'' (1781). He initially grouped them by geography and thus called Austronesians the "people from the southern world". In the third edition, published in 1795, he named Austronesians the "Malay race

The concept of a Malay race was originally proposed by the German physician Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752–1840), and classified as a brown race. ''Malay'' is a loose term used in the late 19th century and early 20th century to describe ...

", or the " brown race", after correspondence with Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English Natural history, naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the European and American voyages of scientific exploration, 1766 natural-history ...

, who was part of the first voyage of James Cook

The first voyage of James Cook was a combined Royal Navy and Royal Society expedition to the south Pacific Ocean aboard HMS Endeavour, HMS ''Endeavour'', from 1768 to 1771. The aims were to observe the 1769 transit of Venus from Tahiti and to ...

. Blumenbach used the term "Malay" due to his belief that most Austronesians spoke the "Malay idiom" (i.e., the Austronesian languages

The Austronesian languages ( ) are a language family widely spoken throughout Maritime Southeast Asia, parts of Mainland Southeast Asia, Madagascar, the islands of the Pacific Ocean and Taiwan (by Taiwanese indigenous peoples). They are spoken ...

), though he inadvertently caused the later confusion of his racial category with the Malay ethnic group. The other varieties Blumenbach identified were the "Caucasians" (white), "Mongolians" (yellow), "Ethiopians" (black), and "Americans" (red). Blumenbach's definition of the "Malay" race is largely identical to the modern distribution of the Austronesian peoples, including not only Islander Southeast Asians but also the people of Madagascar and the Pacific Islands. Although Blumenbach's work was later used in scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that the Human, human species is divided into biologically distinct taxa called "race (human categorization), races", and that empirical evi ...

, Blumenbach was a monogenist and did not believe the human "varieties" were inherently inferior to each other. Rather, he believed that the Malay race was a combination of the "Ethiopian" and "Caucasian" varieties.

By the 19th century, however, a classification of Austronesians as being a subset of the "Mongolian" race was favored, as was polygenism

Polygenism is a theory of human origins which posits the view that humans are of different origins (polygenesis). This view is opposite to the idea of monogenism, which posits a single origin of humanity. Modern scientific views find little merit ...

. The Australo-Melanesian

Australo-Melanesians (also known as Australasians or the Australomelanesoid, Australoid or Australioid race) is an outdated historical grouping of various people indigenous to Melanesia and Australia. Controversially, some groups found in parts ...

populations of Southeast Asia and Melanesia (whom Blumenbach initially classified as a "subrace" of the "Malay" race) were also now being treated as a separate "Ethiopian" race by authors like Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

, Conrad Malte-Brun

Conrad Malte-Brun (; born Malthe Conrad Bruun; 12 August 177514 December 1826), sometimes referred to simply as Malte-Brun, was a Dano- French geographer and journalist. His second son, Victor Adolphe Malte-Brun, was also a geographer. Today he ...

(who first coined the term "Oceania

Oceania ( , ) is a region, geographical region including Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Outside of the English-speaking world, Oceania is generally considered a continent, while Mainland Australia is regarded as its co ...

" as ''Océanique''), Julien-Joseph Virey, and René Lesson

René Primevère Lesson (20 March 1794 – 28 April 1849) was a French surgery, surgeon, natural history, naturalist, ornithologist, and herpetologist.

Biography

Lesson was born at Rochefort, Charente-Maritime, Rochefort, and entered the Naval ...

.

The British naturalist James Cowles Prichard originally followed Blumenbach by treating Papuans and Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians are people with familial heritage from, or recognised membership of, the various ethnic groups living within the territory of contemporary Australia prior to History of Australia (1788–1850), British colonisation. The ...

as being descendants of the same stock as Austronesians. But by his third edition of ''Researches into the Physical History of Man'' (1836–1847), his work had become more racialized due to the influence of polygenism. He classified the peoples of Austronesia into two groups: the "Malayo-Polynesians" (roughly equivalent to the Austronesian peoples) and the "Kelænonesians" (roughly equivalent to the Australo-Melanesians). He further subdivided the latter into the "Alfourous" (also "Haraforas" or "Alfoërs", the Native Australians), and the "Pelagian or Oceanic Negroes" (the Melanesians

Melanesians are the predominant and Indigenous peoples of Oceania, indigenous inhabitants of Melanesia, in an area stretching from New Guinea to the Fiji Islands. Most speak one of the many languages of the Austronesian languages, Austronesian l ...

and western Polynesians). Despite this, he acknowledges that "Malayo-Polynesians" and "Pelagian Negroes" had "remarkable characters in common", particularly in terms of language and craniometry

Craniometry is measurement of the cranium (the main part of the skull), usually the human cranium. It is a subset of cephalometry, measurement of the head, which in humans is a subset of anthropometry, measurement of the human body. It is d ...

.

In linguistics, the Malayo-Polynesian language family also initially excluded Melanesia

Melanesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It extends from New Guinea in the west to the Fiji Islands in the east, and includes the Arafura Sea.

The region includes the four independent countries of Fiji, Vanu ...

and Micronesia

Micronesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, consisting of approximately 2,000 small islands in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean. It has a close shared cultural history with three other island regions: Maritime Southeast Asia to the west, Poly ...

, due to the perceived physical differences between the inhabitants of these regions from Malayo-Polynesian speakers. However, there was growing evidence of their linguistic relationship to Malayo-Polynesian languages, notably from studies on the Melanesian languages

In linguistics, Melanesian is an obsolete term referring to the Austronesian languages of Melanesia: that is, the Oceanic, Eastern Malayo-Polynesian, or Central–Eastern Malayo-Polynesian languages apart from Polynesian and Micronesian. A ty ...

by Georg von der Gabelentz

Georg von der Gabelentz (16 March 1840 – 11 December 1893) was a German general linguist and sinologist. His (1881), according to a critic, "remains until today recognized as probably the finest overall grammatical survey of the Classical Chine ...

, Robert Henry Codrington, and Sidney Herbert Ray

Sidney Herbert Ray (28 May 1858 – 1 January 1939) was a British comparative and descriptive linguist who specialised in Melanesian languages.Papers and field notes relating to his linguistic work are held bSOAS Special Collections/ref>

Bio ...

. Codrington coined and used the term "Ocean" language family rather than "Malayo-Polynesian" in 1891, in opposition to the exclusion of Melanesian and Micronesian languages. This was adopted by Ray, who defined the "Oceanic" language family as encompassing the languages of Southeast Asia and Madagascar, Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia.

In 1899, the Austrian linguist and ethnologist Wilhelm Schmidt coined the term "Austronesian" (German: ''austronesisch'', from Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

''auster

Auster may refer to:

Places

* Auster Glacier, located in East Antarctica

* Auster Islands, East Antarctica

* Auster Pass, located in East Antarctica

* Auster Point, located in West Antarctica

Other uses

* Auster Aircraft, a former British air ...

'', "south wind"; and Greek '' νῆσος'', "island") to refer to the language family. Schmidt had the same motivations as Codrington: he proposed the term as a replacement to "Malayo-Polynesian", because he also opposed the implied exclusion of the languages of Melanesia and Micronesia in the latter name. It became the accepted name for the language family, with Oceanic and Malayo-Polynesian languages

The Malayo-Polynesian languages are a subgroup of the Austronesian languages, with approximately 385.5 million speakers. The Malayo-Polynesian languages are spoken by the Austronesian peoples outside of Taiwan, in the island nations of Southeas ...

being retained as names for subgroups.

The term "Austronesian", or more accurately "Austronesian-speaking peoples", came to refer to people who speak the languages of the Austronesian language family. Some authors, however, object to the use of the term to refer to people, as they question whether there really is any biological or cultural shared ancestry between all Austronesian-speaking groups.According to the anthropologist Wilhelm Solheim II: "I emphasize again, as I have done in many other articles, that 'Austronesian' is a linguistic term and is the name of a super language family. It should never be used as a name for a people, genetically speaking, or a culture. To refer to people who speak an Austronesian language, the phrase 'Austronesian-speaking people' should be used." ''Origins of the Filipinos and Their Languages'' (January 2006) This is especially true for authors who reject the prevailing "Out of Taiwan" hypothesis and instead offer scenarios where the Austronesian languages spread among preexisting static populations through borrowing or convergence, with little or no population movements.

The term "Austronesian", or more accurately "Austronesian-speaking peoples", came to refer to people who speak the languages of the Austronesian language family. Some authors, however, object to the use of the term to refer to people, as they question whether there really is any biological or cultural shared ancestry between all Austronesian-speaking groups.According to the anthropologist Wilhelm Solheim II: "I emphasize again, as I have done in many other articles, that 'Austronesian' is a linguistic term and is the name of a super language family. It should never be used as a name for a people, genetically speaking, or a culture. To refer to people who speak an Austronesian language, the phrase 'Austronesian-speaking people' should be used." ''Origins of the Filipinos and Their Languages'' (January 2006) This is especially true for authors who reject the prevailing "Out of Taiwan" hypothesis and instead offer scenarios where the Austronesian languages spread among preexisting static populations through borrowing or convergence, with little or no population movements.

Despite these objections, the general consensus is that the archeological, cultural, genetic, and especially linguistic evidence all separately indicate varying degrees of shared ancestry among Austronesian-speaking peoples that justifies their treatment as a "

Despite these objections, the general consensus is that the archeological, cultural, genetic, and especially linguistic evidence all separately indicate varying degrees of shared ancestry among Austronesian-speaking peoples that justifies their treatment as a "phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics () is the study of the evolutionary history of life using observable characteristics of organisms (or genes), which is known as phylogenetic inference. It infers the relationship among organisms based on empirical dat ...

unit". This has led to the use of the term "Austronesian" in academic literature to refer not only to the Austronesian languages but also the Austronesian-speaking peoples, their societies, and the geographic area of Austronesia.

Some Austronesian-speaking groups are not direct descendants of Austronesians and acquired their languages through language shift

Language shift, also known as language transfer, language replacement or language assimilation, is the process whereby a speech community shifts to a different language, usually over an extended period of time. Often, languages that are perceived ...

, but this is believed to have happened only in a few instances, since the Austronesian expansion was too rapid for language shifts to have occurred fast enough. In parts of Island Melanesia

Island Melanesia is a subregion of Melanesia in Oceania.

It is located east of New Guinea island, from the Bismarck Archipelago to New Caledonia.Steadman, 2006. ''Extinction & biogeography of tropical Pacific birds''

See also Archaeology a ...

, migrations and paternal admixture from Papuan groups after the Austronesian expansion (estimated to have started at around 500 BCE) also resulted in gradual population turnover. These secondary migrations were incremental and happened gradually enough that the culture and language of these groups remained Austronesian, even though in modern times, they are genetically more Papuan. In the vast majority of cases, the language and material culture of Austronesian-speaking groups descend directly through generational continuity, especially in islands that were previously uninhabited.

Serious research into the Austronesian languages and its speakers has been ongoing since the 19th century. Modern scholarship on Austronesian dispersion models is generally credited to two influential papers in the late 20th century: ''The Colonization of the Pacific: A Genetic Trail'' (Hill

A hill is a landform that extends above the surrounding terrain. It often has a distinct summit, and is usually applied to peaks which are above elevation compared to the relative landmass, though not as prominent as Mountain, mountains. Hills ...

& Serjeantson, eds., 1989) and ''The Austronesian Dispersal and the Origin of Languages'' ( Bellwood, 1991). The topic is particularly interesting to scientists for the remarkably unique characteristics of the Austronesian speakers: their extent, diversity, and rapid dispersal.

Regardless, certain disagreements still exist among researchers with regards to chronology, origin, dispersal, adaptations to the island environments, interactions with preexisting populations in areas they settled, and cultural developments over time. The mainstream accepted hypothesis is the "Out of Taiwan" model first proposed by Peter Bellwood. But there are multiple rival models that create a sort of "pseudo-competition" among their supporters due to narrow focus on data from limited geographic areas or disciplines. The most notable of which is the "Out of Sundaland" (or "Out of Island Southeast Asia") model.

Geographic distribution

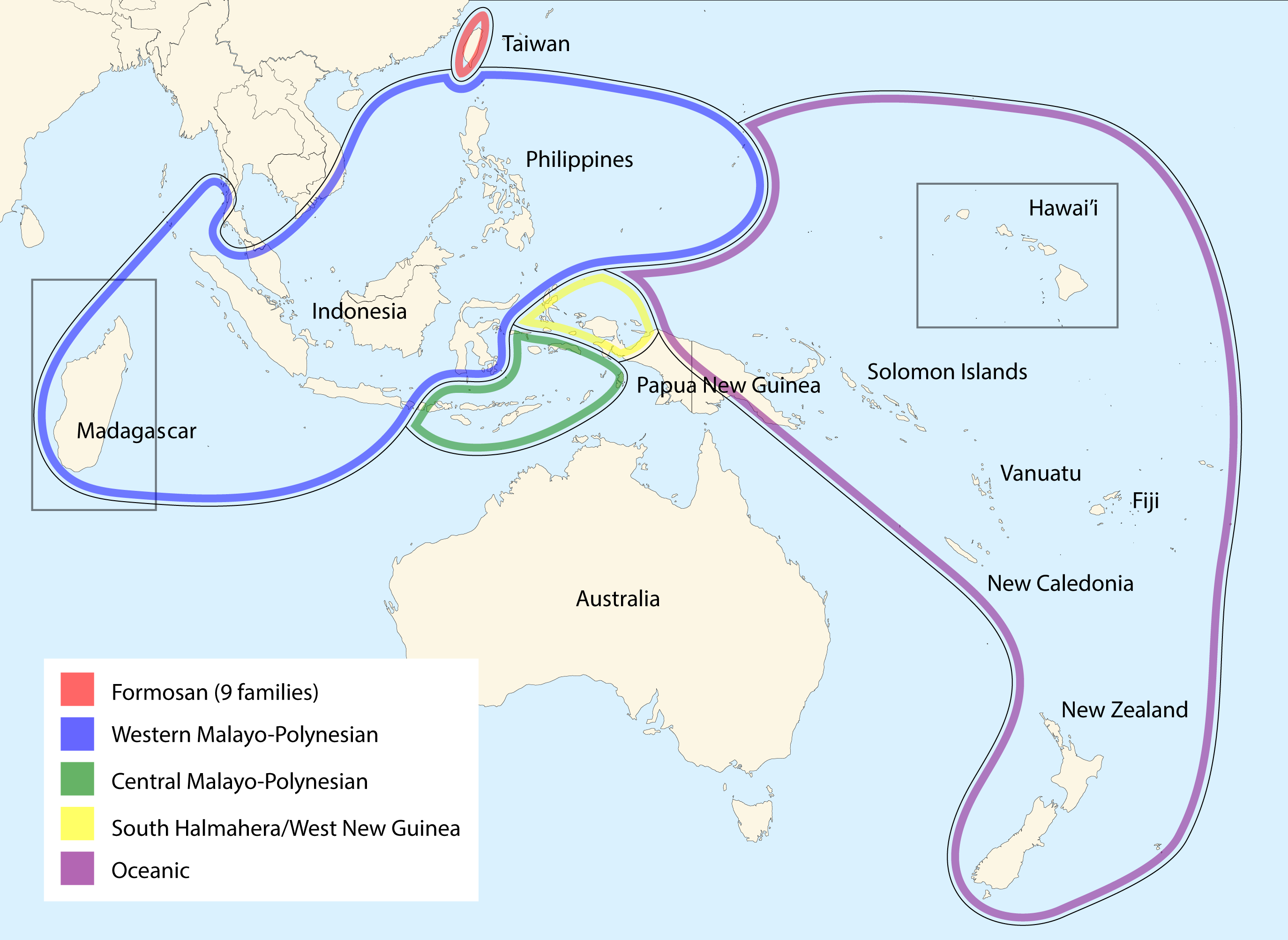

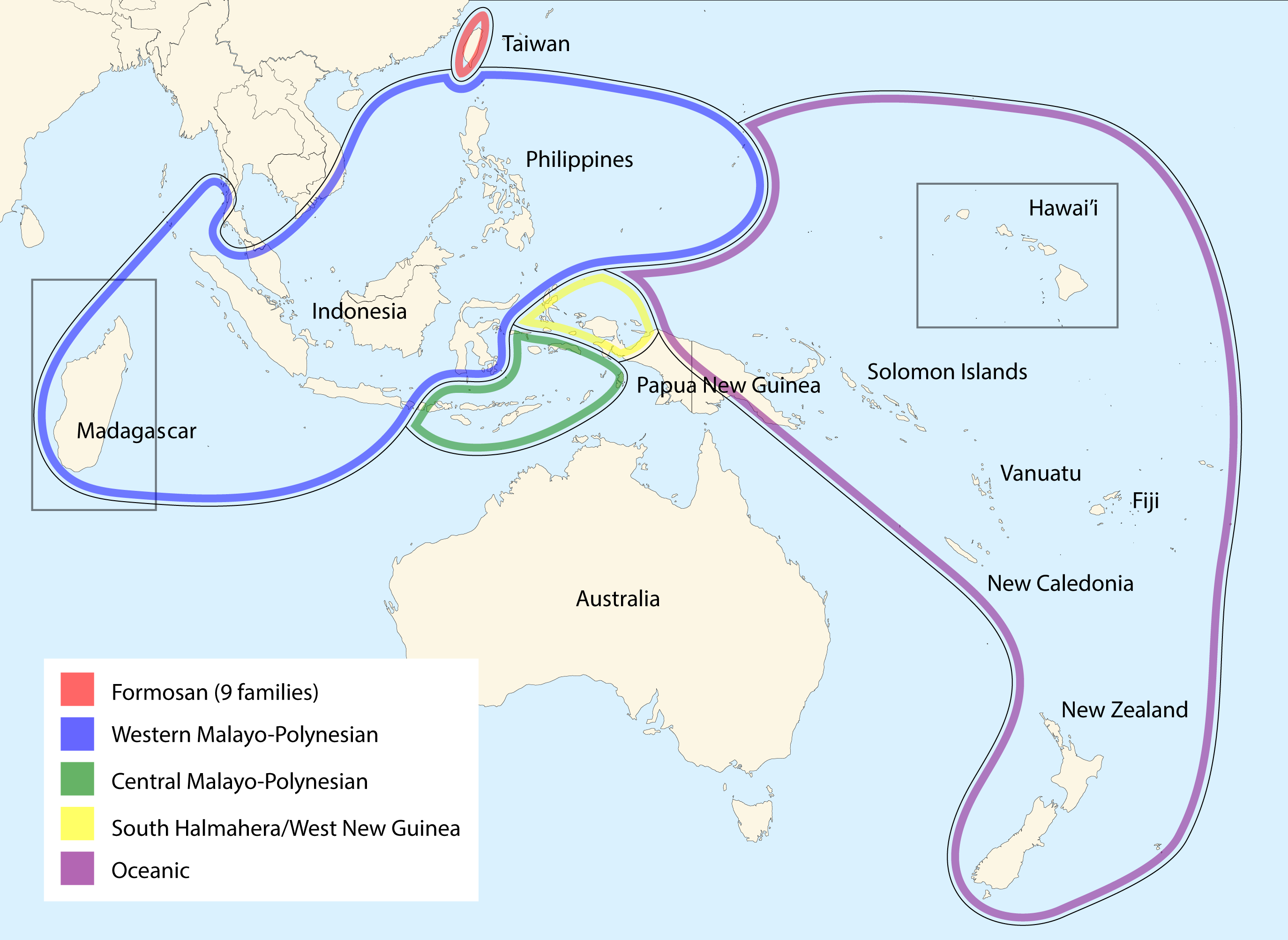

Austronesians were the first humans with seafaring vessels that could cross large distances on the open ocean; this technology allowed them to colonize a large part of theIndo-Pacific

The Indo-Pacific is a vast biogeographic region of Earth. In a narrow sense, sometimes known as the Indo-West Pacific or Indo-Pacific Asia, it comprises the tropical waters of the Indian Ocean, the western and central Pacific Ocean, and the ...

region. Prior to the 16th-century colonial era, the Austronesian language family was the most widespread in the world, spanning half the planet from Easter Island

Easter Island (, ; , ) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is renowned for its nearly 1,000 extant monumental statues, ...

in the eastern Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

to Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

in the western Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

.

Languages of the Austronesian family are today spoken by about 386 million people (4.9% of the global population), making it the fifth-largest language family by number of speakers. Major Austronesian languages include Malay (around 250–270 million in Indonesia alone in its own literary standard, named Indonesian), Javanese, and Filipino ( Tagalog). The family contains 1,257 languages, the second-largest number of any language family.

The geographic region that encompasses native Austronesian-speaking populations is sometimes referred to as "Austronesia". Other geographic names for various subregions include Malay Peninsula

The Malay Peninsula is located in Mainland Southeast Asia. The landmass runs approximately north–south, and at its terminus, it is the southernmost point of the Asian continental mainland. The area contains Peninsular Malaysia, Southern Tha ...

, Greater Sunda Islands

The Greater Sunda Islands (Indonesian language, Indonesian and Malay language, Malay: ''Kepulauan Sunda Besar'') are four tropical islands situated within the Indonesian Archipelago, in the Pacific Ocean. The islands, Borneo, Java, Sulawesi and S ...

, Lesser Sunda Islands

The Lesser Sunda Islands (, , ), now known as Nusa Tenggara Islands (, or "Southeast Islands"), are an archipelago in the Indonesian archipelago. Most of the Lesser Sunda Islands are located within the Wallacea region, except for the Bali pro ...

, Island Melanesia

Island Melanesia is a subregion of Melanesia in Oceania.

It is located east of New Guinea island, from the Bismarck Archipelago to New Caledonia.Steadman, 2006. ''Extinction & biogeography of tropical Pacific birds''

See also Archaeology a ...

, Island Southeast Asia, Malay Archipelago

The Malay Archipelago is the archipelago between Mainland Southeast Asia and Australia, and is also called Insulindia or the Indo-Australian Archipelago. The name was taken from the 19th-century European concept of a Malay race, later based ...

, Maritime Southeast Asia

Maritime Southeast Asia comprises the Southeast Asian countries of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and East Timor.

The terms Island Southeast Asia and Insular Southeast Asia are sometimes given the same meaning as ...

, Melanesia

Melanesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It extends from New Guinea in the west to the Fiji Islands in the east, and includes the Arafura Sea.

The region includes the four independent countries of Fiji, Vanu ...

, Micronesia

Micronesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, consisting of approximately 2,000 small islands in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean. It has a close shared cultural history with three other island regions: Maritime Southeast Asia to the west, Poly ...

, Near Oceania

Near Oceania is the part of Oceania that features greater biodiversity, due to the islands and atolls being closer to each other. The distinction of Near Oceania and Remote Oceania was first suggested by Pawley & Green (1973) and was further el ...

, Oceania

Oceania ( , ) is a region, geographical region including Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Outside of the English-speaking world, Oceania is generally considered a continent, while Mainland Australia is regarded as its co ...

, Pacific Islands

The Pacific islands are a group of islands in the Pacific Ocean. They are further categorized into three major island groups: Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Depending on the context, the term ''Pacific Islands'' may refer to one of several ...

, Remote Oceania, Polynesia

Polynesia ( , ) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of more than 1,000 islands scattered over the central and southern Pacific Ocean. The indigenous people who inhabit the islands of Polynesia are called Polynesians. They have many things in ...

, and Wallacea

Wallacea is a biogeography, biogeographical designation for a group of mainly list of islands of Indonesia, Indonesian islands separated by deep-water straits from the Asian and Australia (continent), Australian continental shelf, continental ...

. In Indonesia, the nationalistic term Nusantara, from Old Javanese

Old Javanese or Kawi is an Austronesian languages, Austronesian language and the oldest attested phase of the Javanese language. It was natively spoken in the central and eastern part of Java Island, what is now Central Java, Special Region o ...

, is also popularly used for the Indonesian islands.

Austronesian regions are almost exclusively islands in the Pacific and Indian oceans, with predominantly tropical

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the equator, where the sun may shine directly overhead. This contrasts with the temperate or polar regions of Earth, where the Sun can never be directly overhead. This is because of Earth's ax ...

or subtropical

The subtropical zones or subtropics are geographical zone, geographical and Köppen climate classification, climate zones immediately to the Northern Hemisphere, north and Southern Hemisphere, south of the tropics. Geographically part of the Ge ...

climates with considerable seasonal rainfall.

Inhabitants of these regions include Taiwanese indigenous peoples

Taiwanese indigenous peoples, formerly called Taiwanese aborigines, are the indigenous peoples of Taiwan, with the nationally recognized subgroups numbering about 600,303 or 3% of the Geography of Taiwan, island's population. This total is incr ...

, most ethnic groups in Brunei

Brunei, officially Brunei Darussalam, is a country in Southeast Asia, situated on the northern coast of the island of Borneo. Apart from its coastline on the South China Sea, it is completely surrounded by the Malaysian state of Sarawak, with ...

, East Timor

Timor-Leste, also known as East Timor, officially the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste, is a country in Southeast Asia. It comprises the eastern half of the island of Timor, the coastal exclave of Oecusse in the island's northwest, and ...

, Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania, between the Indian Ocean, Indian and Pacific Ocean, Pacific oceans. Comprising over List of islands of Indonesia, 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, ...

, Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

, Malaysia

Malaysia is a country in Southeast Asia. Featuring the Tanjung Piai, southernmost point of continental Eurasia, it is a federation, federal constitutional monarchy consisting of States and federal territories of Malaysia, 13 states and thre ...

, Micronesia

Micronesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, consisting of approximately 2,000 small islands in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean. It has a close shared cultural history with three other island regions: Maritime Southeast Asia to the west, Poly ...

, the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

, and Polynesia

Polynesia ( , ) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of more than 1,000 islands scattered over the central and southern Pacific Ocean. The indigenous people who inhabit the islands of Polynesia are called Polynesians. They have many things in ...

. Also included are the Malays of Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

; the Polynesians

Polynesians are an ethnolinguistic group comprising closely related ethnic groups native to Polynesia, which encompasses the islands within the Polynesian Triangle in the Pacific Ocean. They trace their early prehistoric origins to Island Sout ...

of New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

, Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; ) is an island U.S. state, state of the United States, in the Pacific Ocean about southwest of the U.S. mainland. One of the two Non-contiguous United States, non-contiguous U.S. states (along with Alaska), it is the only sta ...

, and Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

; the Torres Strait Islanders

Torres Strait Islanders ( ) are the Indigenous Melanesians, Melanesian people of the Torres Strait Islands, which are part of the state of Queensland, Australia. Ethnically distinct from the Aboriginal Australians, Aboriginal peoples of the res ...

of Australia; the non-Papuan people Papuans may refer to:

* Indonesian Papuans – the Native Indonesians of Papua-origin

* Papua New Guineans – the nationals of Papua New Guinea

* Indigenous people of New Guinea

{{Disambiguation

Language and nationality disambiguation page ...

s of Melanesia

Melanesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It extends from New Guinea in the west to the Fiji Islands in the east, and includes the Arafura Sea.

The region includes the four independent countries of Fiji, Vanu ...

and coastal New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; , fossilized , also known as Papua or historically ) is the List of islands by area, world's second-largest island, with an area of . Located in Melanesia in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is ...

; the Shibushi speakers of the Comoros

The Comoros, officially the Union of the Comoros, is an archipelagic country made up of three islands in Southeastern Africa, located at the northern end of the Mozambique Channel in the Indian Ocean. Its capital and largest city is Moroni, ...

, and the Malagasy and Shibushi speakers of Réunion

Réunion (; ; ; known as before 1848) is an island in the Indian Ocean that is an overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department and region of France. Part of the Mascarene Islands, it is located approximately east of the isl ...

. Austronesians are also found in the regions of Southern Thailand

Southern Thailand (formerly Southern Siam and Tambralinga) is the southernmost cultural region of Thailand, separated from Central Thailand by the Kra Isthmus.

Geography

Southern Thailand is on the Malay Peninsula, with an area of around , bo ...

; the Cham areas in Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

, Cambodia

Cambodia, officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. It is bordered by Thailand to the northwest, Laos to the north, and Vietnam to the east, and has a coastline ...

, and Hainan

Hainan is an island provinces of China, province and the southernmost province of China. It consists of the eponymous Hainan Island and various smaller islands in the South China Sea under the province's administration. The name literally mean ...

; and the Mergui Archipelago of Myanmar.

Additionally, modern-era migration has brought Austronesian-speaking people to the United States, Canada, Australia, the UK, mainland Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous mainland of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by so ...

, Cocos (Keeling) Islands

The Cocos (Keeling) Islands (), officially the Territory of Cocos (Keeling) Islands (; ), are an Australian external territory in the Indian Ocean, comprising a small archipelago approximately midway between Australia and Sri Lanka and rel ...

, South Africa, Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

, Suriname

Suriname, officially the Republic of Suriname, is a country in northern South America, also considered as part of the Caribbean and the West Indies. It is a developing country with a Human Development Index, high level of human development; i ...

, Hong Kong

Hong Kong)., Legally Hong Kong, China in international treaties and organizations. is a special administrative region of China. With 7.5 million residents in a territory, Hong Kong is the fourth most densely populated region in the wor ...

, Macau

Macau or Macao is a special administrative regions of China, special administrative region of the People's Republic of China (PRC). With a population of about people and a land area of , it is the most List of countries and dependencies by p ...

, and West Asian countries.

Some authors also propose further settlements and contacts in the past in areas that are not inhabited by Austronesian speakers today. These range from likely hypotheses to very controversial claims with minimal evidence. In 2009, Roger Blench

Roger Marsh Blench (born August 1, 1953) is a British linguist, ethnomusicologist and development anthropologist. He has an M.A. and a Ph.D. from the University of Cambridge and is based in Cambridge, England. He researches, publishes, and work ...

compiled an expanded map of Austronesia that encompassed these claims based on a variety of evidence, such as historical accounts, loanwords, introduced plants and animals, genetics, archeological sites, and material culture. They include areas like the Pacific coast

Pacific coast may be used to reference any coastline that borders the Pacific Ocean.

Geography Americas North America

Countries on the western side of North America have a Pacific coast as their western or south-western border. One of th ...

of the Americas, Japan, the Yaeyama Islands

The Yaeyama Islands (八重山列島 ''Yaeyama-rettō'', also 八重山諸島 ''Yaeyama-shotō'', Yaeyama: ''Yaima'', Yonaguni: ''Daama'', Okinawan: ''Yeema'', Northern Ryukyuan: ''Yapema'') are an archipelago in the southwest of Okinawa Pref ...

, the Australian coast, Sri Lanka and coastal South Asia

South Asia is the southern Subregion#Asia, subregion of Asia that is defined in both geographical and Ethnicity, ethnic-Culture, cultural terms. South Asia, with a population of 2.04 billion, contains a quarter (25%) of the world's populatio ...

, the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, mediterranean sea in West Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Arabian Sea and the larger Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.Un ...

, some Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

islands, East Africa

East Africa, also known as Eastern Africa or the East of Africa, is a region at the eastern edge of the Africa, African continent, distinguished by its unique geographical, historical, and cultural landscape. Defined in varying scopes, the regi ...

, South Africa, and West Africa

West Africa, also known as Western Africa, is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations geoscheme for Africa#Western Africa, United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Gha ...

.

List of Austronesian peoples

Austronesian peoples include the following groupings by name and geographic location (incomplete): * Formosan:Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

(e.g., Amis, Atayal, Bunun, Paiwan, collectively known as Taiwanese indigenous peoples

Taiwanese indigenous peoples, formerly called Taiwanese aborigines, are the indigenous peoples of Taiwan, with the nationally recognized subgroups numbering about 600,303 or 3% of the Geography of Taiwan, island's population. This total is incr ...

)

* Malayo-Polynesian

The Malayo-Polynesian languages are a subgroup of the Austronesian languages, with approximately 385.5 million speakers. The Malayo-Polynesian languages are spoken by the Austronesian peoples outside of Taiwan, in the island nations of Southeast ...

:

** Borneo

Borneo () is the List of islands by area, third-largest island in the world, with an area of , and population of 23,053,723 (2020 national censuses). Situated at the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, it is one of the Greater Sunda ...

groups (e.g., Kadazan-Dusun

Kadazandusun (also written as Kadazan-Dusun or Mamasok) are the largest ethnic group in Sabah, Malaysia, an amalgamation of the closely related indigenous peoples, indigenous Kadazan people, Kadazan and Dusun people, Dusun peoples. "Kadazandus ...

, Murut, Iban, Bidayuh, Dayak, Lun Bawang/Lundayeh)

** Chamic group: Cambodia

Cambodia, officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. It is bordered by Thailand to the northwest, Laos to the north, and Vietnam to the east, and has a coastline ...

, Hainan

Hainan is an island provinces of China, province and the southernmost province of China. It consists of the eponymous Hainan Island and various smaller islands in the South China Sea under the province's administration. The name literally mean ...

, Cham areas of Vietnam (remnants of the Champa

Champa (Cham language, Cham: ꨌꩌꨛꨩ, چمڤا; ; 占城 or 占婆) was a collection of independent Chams, Cham Polity, polities that extended across the coast of what is present-day Central Vietnam, central and southern Vietnam from ...

kingdom, which covered central and southern Vietnam) as well as Aceh

Aceh ( , ; , Jawi script, Jawoë: ; Van Ophuijsen Spelling System, Old Spelling: ''Atjeh'') is the westernmost Provinces of Indonesia, province of Indonesia. It is located on the northern end of Sumatra island, with Banda Aceh being its capit ...

, in northern Sumatra (e.g., Acehnese, Chams

The Chams ( Cham: , چام, ''cam''), or Champa people ( Cham: , اوراڠ چمڤا, ''Urang Campa''; or ; , ), are an Austronesian ethnic group in Southeast Asia and are the original inhabitants of central Vietnam and coastal Cambodia be ...

, Jarai, Utsuls)

** Central Luzon

Central Luzon (; ; ; ; ), designated as Region III, is an administrative region in the Philippines. The region comprises seven provinces: Aurora, Bataan, Bulacan, Nueva Ecija, Pampanga (with its capital, San Fernando City serving as the re ...

group: (e.g., Kapampangan, Sambal)

** Igorot

The indigenous peoples of the Cordillera in northern Luzon, Philippines, often referred to by the exonym Igorot people, or more recently, as the Cordilleran peoples, are an ethnic group composed of nine main ethnolinguistic groups whose domains ...

(Cordillerans): Cordilleras (e.g., Balangao, Ibaloi, Ifugao

Ifugao, officially the Province of Ifugao (; ), is a landlocked province of the Philippines in the Cordillera Administrative Region in Luzon. Its capital is Lagawe and it borders Benguet to the west, Mountain Province to the north, Isabela t ...

, Itneg, Kankanaey)

** Lumad

The Lumad are a group of Austronesian indigenous peoples in the southern Philippines. It is a Cebuano term meaning "native" or "indigenous". The term is short for Katawhang Lumad (Literally: "indigenous people"), the autonym officially ado ...

: Mindanao

Mindanao ( ) is the List of islands of the Philippines, second-largest island in the Philippines, after Luzon, and List of islands by population, seventh-most populous island in the world. Located in the southern region of the archipelago, the ...

(e.g., Kamayo, Mandaya, Mansaka, Kalagan, Manobo, Tasaday

The Tasaday () are an indigenous peoples of the Lake Sebu area in Mindanao, Philippines. They are considered to belong to the Lumad group, along with the other indigenous groups on the island. They attracted widespread media attention in 1971, ...

, T'boli)

** Malagasy: Madagascar