Alexander Cameron Rutherford on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

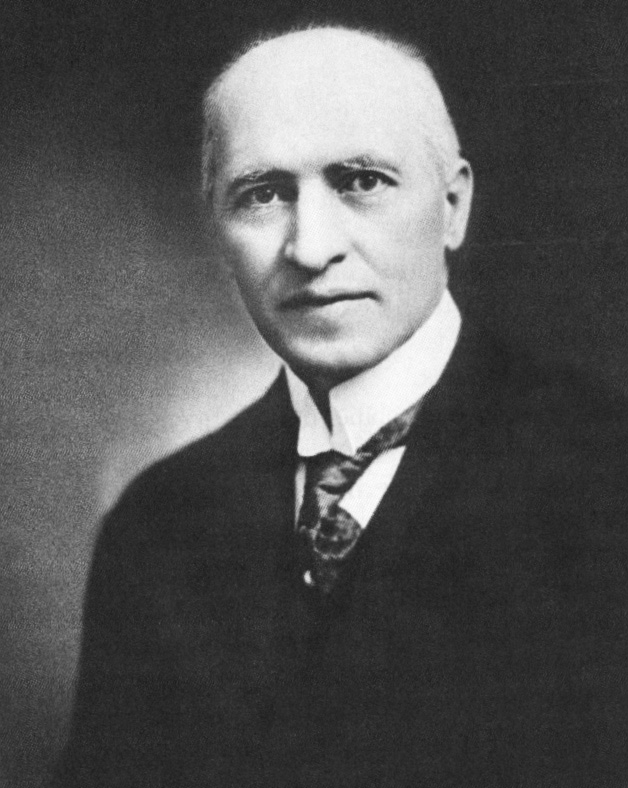

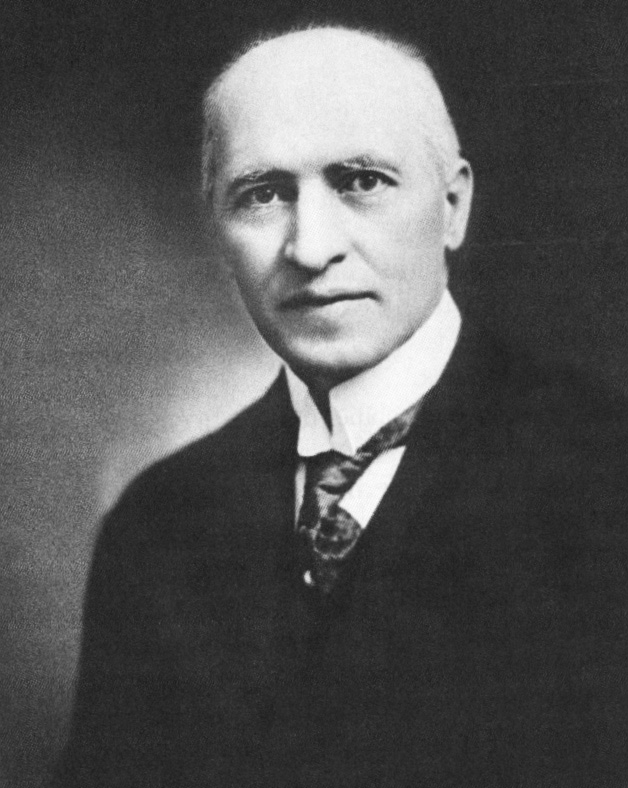

Alexander Cameron Rutherford (February 2, 1857 – June 11, 1941) was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the first

Alexander Rutherford was born February 2, 1857, near Ormond, Canada West, on his family's dairy farm. His parents, James (1817–1891) and Elspet "Elizabeth" (1818–1901) Cameron Rutherford, had immigrated from Scotland two years previous. They joined the

Alexander Rutherford was born February 2, 1857, near Ormond, Canada West, on his family's dairy farm. His parents, James (1817–1891) and Elspet "Elizabeth" (1818–1901) Cameron Rutherford, had immigrated from Scotland two years previous. They joined the

Rutherford quickly became deeply involved in the community. Among the roles he acquired during his first three years in the District of Alberta were president of the newly formed South Edmonton Football Club, secretary-treasurer of the South Edmonton School Board, president of the South Edmonton Athletic Association, vice president of the South Edmonton Literary Institute, auditor of the South Edmonton Agricultural Society, and worthy master of the Acacia Lodge, Ancient Free and Accepted Masons. He also became secretary of the Edmonton District Butter and Cheese Manufacturing Association. Rutherford also became involved in the provincial autonomy movement for the North-West Territories in 1896. He was an early advocate for the incorporation of South Edmonton, hitherto an

Rutherford quickly became deeply involved in the community. Among the roles he acquired during his first three years in the District of Alberta were president of the newly formed South Edmonton Football Club, secretary-treasurer of the South Edmonton School Board, president of the South Edmonton Athletic Association, vice president of the South Edmonton Literary Institute, auditor of the South Edmonton Agricultural Society, and worthy master of the Acacia Lodge, Ancient Free and Accepted Masons. He also became secretary of the Edmonton District Butter and Cheese Manufacturing Association. Rutherford also became involved in the provincial autonomy movement for the North-West Territories in 1896. He was an early advocate for the incorporation of South Edmonton, hitherto an

During the 1898 territorial election, Rutherford again challenged the now-incumbent McCauley. His defeat of two years previous still fresh in his mind, his platform this time included a call for a redrawing of the territory's electoral boundaries. He believed that the current Edmonton riding was

During the 1898 territorial election, Rutherford again challenged the now-incumbent McCauley. His defeat of two years previous still fresh in his mind, his platform this time included a call for a redrawing of the territory's electoral boundaries. He believed that the current Edmonton riding was

In February 1905, the federal government of

In February 1905, the federal government of

Besides the Conservatives' ties to the CPR, Rutherford's Liberals enjoyed the incumbent's advantage of controlling the levers of

Besides the Conservatives' ties to the CPR, Rutherford's Liberals enjoyed the incumbent's advantage of controlling the levers of

While the regionally-charged issues attracted much attention, they were far from the government's only initiatives during the legislature's first session. In 1906, it passed a series of acts dealing with the organization and administration of the new provincial government and incorporated the cities of

While the regionally-charged issues attracted much attention, they were far from the government's only initiatives during the legislature's first session. In 1906, it passed a series of acts dealing with the organization and administration of the new provincial government and incorporated the cities of

Rutherford's government appointed a commission in February, but it was not until May that it met. It consisted of Chief Justice Arthur Sifton, mining executive Lewis Stockett, and miners' union executive William Haysom. It began taking evidence in July. In the meantime, a May agreement saw most miners return to work at increased rates of pay. Coal supply promptly increased, as did its price. In August, the commission released its recommendations, which included a prohibition on children under 16 working in mines, the posting of inspectors' reports, mandatory bath houses at mine sites, and improved ventilation inspection. It also recommended for Albertans to keep a supply of coal on hand during the summer for winter use. The commission was silent on wages (other than to say that these should not be fixed by legislation), the operation of

Rutherford's government appointed a commission in February, but it was not until May that it met. It consisted of Chief Justice Arthur Sifton, mining executive Lewis Stockett, and miners' union executive William Haysom. It began taking evidence in July. In the meantime, a May agreement saw most miners return to work at increased rates of pay. Coal supply promptly increased, as did its price. In August, the commission released its recommendations, which included a prohibition on children under 16 working in mines, the posting of inspectors' reports, mandatory bath houses at mine sites, and improved ventilation inspection. It also recommended for Albertans to keep a supply of coal on hand during the summer for winter use. The commission was silent on wages (other than to say that these should not be fixed by legislation), the operation of

While most public works issues were handled by Public Works Minister Cushing, but after the 1909 election, Rutherford named himself as the province's first Minister of Railways.

While most public works issues were handled by Public Works Minister Cushing, but after the 1909 election, Rutherford named himself as the province's first Minister of Railways.

Besides his work as a lawyer, Alexander Rutherford was involved in a number of business enterprises. He was President of the Edmonton Mortgage Corporation and Vice President and solicitor of the Great Western Garment Company. The latter enterprise, which Rutherford co-founded, was a great success: established in 1911 with eight seamstresses, it had quadrupled in size within a year. During the

Besides his work as a lawyer, Alexander Rutherford was involved in a number of business enterprises. He was President of the Edmonton Mortgage Corporation and Vice President and solicitor of the Great Western Garment Company. The latter enterprise, which Rutherford co-founded, was a great success: established in 1911 with eight seamstresses, it had quadrupled in size within a year. During the

Convocation was not the only reason that students visited Rutherford's home. He had a wealth of both knowledge and books on Canadian subjects and welcomed students to consult his private library. The library eventually expanded beyond the room in his mansion devoted to it, to encompass the house's den, maid's sitting room, and garage as well. After his death, the collection was donated and sold to the university's library system; it was described in 1967 as "still the most important rare collection in the library".

Rutherford remained on the university's senate until 1927, when he was elected

Convocation was not the only reason that students visited Rutherford's home. He had a wealth of both knowledge and books on Canadian subjects and welcomed students to consult his private library. The library eventually expanded beyond the room in his mansion devoted to it, to encompass the house's den, maid's sitting room, and garage as well. After his death, the collection was donated and sold to the university's library system; it was described in 1967 as "still the most important rare collection in the library".

Rutherford remained on the university's senate until 1927, when he was elected

In 1911, the Rutherfords built a new house adjacent to the University of Alberta campus. Rutherford named it "Archnacarry", after his ancestral homeland in Scotland. Now known as Rutherford House, it serves as a museum. He made several trips to the United Kingdom and was invited to attend the

In 1911, the Rutherfords built a new house adjacent to the University of Alberta campus. Rutherford named it "Archnacarry", after his ancestral homeland in Scotland. Now known as Rutherford House, it serves as a museum. He made several trips to the United Kingdom and was invited to attend the

premier of Alberta

The premier of Alberta is the head of government and first minister of the Canadian province of Alberta. The current premier is Danielle Smith, leader of the governing United Conservative Party, who was sworn in on October 11, 2022.

The premi ...

from 1905 to 1910. Born in Ormond, Canada West, he studied and practiced law in Ottawa

Ottawa is the capital city of Canada. It is located in the southern Ontario, southern portion of the province of Ontario, at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the cor ...

before he moved with his family to the North-West Territories

The Northwest Territories is a federal territory of Canada. At a land area of approximately and a 2021 census population of 41,070, it is the second-largest and the most populous of the three territories in Northern Canada. Its estimated pop ...

in 1895. Besides his work as lawyer, he began a political career that would see him first serve as member of the North-West Legislative Assembly and then as Liberal MLA, Liberal party leader, and premier of Alberta. He lost the premiership in 1910 due to the Alberta and Great Waterways Railway scandal and his Legislature seat in 1913. He later was prominent in the administration of the University of Alberta, beside which he and his family lived for decades. His home, Rutherford House, is an historic site on the grounds of the University of Alberta

The University of Alberta (also known as U of A or UAlberta, ) is a public research university located in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. It was founded in 1908 by Alexander Cameron Rutherford, the first premier of Alberta, and Henry Marshall Tory, t ...

.

In keeping with the territorial custom, while NWT member, Rutherford described himself as an independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in Pennsylvania, United States

* Independentes (English: Independents), a Portuguese artist ...

but generally supported the administration of NWT Premier Frederick W. A. G. Haultain. At the federal level, however, Rutherford was a prominent Liberal.

When the Province of Alberta was formed in 1905, its Lieutenant Governor, George Bulyea, asked Rutherford to form the new province's first government. As premier, Rutherford's first task was to win a workable majority in the Legislative Assembly of Alberta

The Legislative Assembly of Alberta is the deliberative assembly of the province of Alberta, Canada. It sits in the Alberta Legislature Building in Edmonton. Since 2012 the Legislative Assembly has had 87 members, elected first past the post f ...

, which he did in that year's provincial election. His second was to organize the provincial government, and his government established everything from speed limit

Speed limits on road traffic, as used in most countries, set the legal maximum speed at which vehicles may travel on a given stretch of road. Speed limits are generally indicated on a traffic sign reflecting the maximum permitted speed, express ...

s to a provincial court system. The legislature also controversially, and with Rutherford's support, selected Edmonton

Edmonton is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Alberta. It is situated on the North Saskatchewan River and is the centre of the Edmonton Metropolitan Region, which is surrounded by Central Alberta ...

over rival Calgary

Calgary () is a major city in the Canadian province of Alberta. As of 2021, the city proper had a population of 1,306,784 and a metropolitan population of 1,481,806 making it the third-largest city and fifth-largest metropolitan area in C ...

as the provincial capital. Calgarians' bruised feelings were not salved when the government located the University of Alberta

The University of Alberta (also known as U of A or UAlberta, ) is a public research university located in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. It was founded in 1908 by Alexander Cameron Rutherford, the first premier of Alberta, and Henry Marshall Tory, t ...

, a project dear to the Premier's heart, in his hometown of Strathcona, just across the North Saskatchewan River

The North Saskatchewan River is a glacier-fed river that flows from the Canadian Rockies continental divide east to central Saskatchewan, where it joins with the South Saskatchewan River to make up the Saskatchewan River. Its water flows event ...

from Edmonton.

The government was faced with labour unrest in the coal mining industry, which it resolved by establishing a commission to examine the problem. It also set up a provincial government telephone network (Alberta Government Telephones

Alberta Government Telephones (AGT) was the telephone provider in most of Alberta from 1906 to 1991.

AGT was formed by the Liberal Party of Alberta, Liberal government of Alexander Cameron Rutherford in 1906Wilson, Kevin G., Deregulating Teleco ...

) at great expense, and tried to encourage the development of new railways. It was in pursuit of the last objective that the Rutherford government found itself embroiled in scandal. Early in 1910, William Henry Cushing

William Henry Cushing (August 21, 1852 – January 25, 1934) was a Canadian politician. Born in Ontario, he migrated west as a young adult where he started a successful lumber company and later became Alberta's first Minister of Public Works an ...

's resignation as Minister of Public Works precipitated the Alberta and Great Waterways Railway scandal, which turned many of Rutherford's Liberals against his government. Eventually, pressure from many party figures forced Rutherford to resign. He kept his seat in the legislature after resigning as premier, but he was defeated in the 1913 election by Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

Herbert Crawford.

After leaving politics, Rutherford continued his law practice and his involvement with a wide range of community groups. Most importantly, he became chancellor of the University of Alberta, whose earlier founding had been a personal project, and stayed in that position until he died of a heart attack. A University of Alberta library, an Edmonton elementary school, and Jasper National Park

Jasper National Park, in Alberta, Canada, is the largest national park within Alberta's Rocky Mountains, spanning . It was established as Jasper Forest Park in 1907, renamed as a national park in 1930, and declared a UNESCO world heritage site ...

's Mount Rutherford are named in his honour. Additionally, his home, Rutherford House, was opened as a museum in 1973, and is an Alberta provincial historic site.

Early life

Alexander Rutherford was born February 2, 1857, near Ormond, Canada West, on his family's dairy farm. His parents, James (1817–1891) and Elspet "Elizabeth" (1818–1901) Cameron Rutherford, had immigrated from Scotland two years previous. They joined the

Alexander Rutherford was born February 2, 1857, near Ormond, Canada West, on his family's dairy farm. His parents, James (1817–1891) and Elspet "Elizabeth" (1818–1901) Cameron Rutherford, had immigrated from Scotland two years previous. They joined the Baptist Church

Baptists are a denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers ( believer's baptism) and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches generally subscribe to the doctrines of ...

, and his father joined the Liberal Party of Canada

The Liberal Party of Canada (LPC; , ) is a federal political party in Canada. The party espouses the principles of liberalism,McCall, Christina; Stephen Clarkson"Liberal Party". ''The Canadian Encyclopedia''. and generally sits at the Centrism, ...

and served for a time on the Osgoode village council. Rutherford attended the local public "scotch school" and, after rejecting dairy farming as a vocation, enrolled in a Metcalfe high school. After graduating in 1874, he attended the Canadian Literary Institute, a Baptist college in Woodstock

The Woodstock Music and Art Fair, commonly referred to as Woodstock, was a music festival held from August 15 to 18, 1969, on Max Yasgur's dairy farm in Bethel, New York, southwest of the town of Woodstock, New York, Woodstock. Billed as "a ...

. He graduated from there in 1876 and taught for a year in Osgoode, having passed his teaching examination the year previous.

He moved to Montreal

Montreal is the List of towns in Quebec, largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Quebec, the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-largest in Canada, and the List of North American cit ...

to study arts and law at McGill University

McGill University (French: Université McGill) is an English-language public research university in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Founded in 1821 by royal charter,Frost, Stanley Brice. ''McGill University, Vol. I. For the Advancement of Learning, ...

. He was awarded degrees in both in 1881, and joined the Ottawa

Ottawa is the capital city of Canada. It is located in the southern Ontario, southern portion of the province of Ontario, at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the cor ...

law firm of Scott, McTavish and McCracken, where he was articled for four years under the tutelage of Richard William Scott

Sir Richard William Scott, (February 24, 1825 – April 23, 1913) was a Canadian politician and cabinet minister.

Early life

He was born in Prescott, Ontario, in 1825, a descendant of a family from County Clare. A lawyer by training, Scot ...

. Called to the Ontario bar in 1885, he became a junior partner in the firm of Hodkins, Kidd and Rutherford, with responsibility for its Kemptville

Kemptville is a community located in the Municipality of North Grenville in Eastern Ontario, Canada in the northernmost part of the United Counties of Leeds and Grenville. It is located approximately south of the downtown core of Ottawa and ...

office for ten years. He also established a moneylending business there.

Meanwhile, his social circle grew to include William Cameron Edwards. Through Edwards, Rutherford was introduced to the Birkett family, which included former Member of Parliament Thomas Birkett. Rutherford married Birkett's niece, Mattie Birkett, in December 1888. The couple had three children: Cecil (born in 1890), Hazel (born in 1893), and Marjorie (born in 1903 but died sixteen months later). Rutherford had a traditional view of gender roles and was happy to leave most childrearing responsibilities to his wife.

Move west

In November 1886 Rutherford visited the Canadian West for the first time when he travelled toBritish Columbia

British Columbia is the westernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Situated in the Pacific Northwest between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains, the province has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that ...

to investigate the disappearance of his cousin. The Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in great-circle distance, straight-line distance from the northernmost part of Western Can ...

left a great impression on him, as did the coastal climate, which he found "very agreeable". He visited again in the summer of 1894, when he took the Canadian Pacific Railway

The Canadian Pacific Railway () , also known simply as CPR or Canadian Pacific and formerly as CP Rail (1968–1996), is a Canadian Class I railway incorporated in 1881. The railway is owned by Canadian Pacific Kansas City, Canadian Pacific Ka ...

across the prairies. Upon arriving in South Edmonton, he was excited by its growth potential and pleased to find that the dry air relieved his bronchitis

Bronchitis is inflammation of the bronchi (large and medium-sized airways) in the lungs that causes coughing. Bronchitis usually begins as an infection in the nose, ears, throat, or sinuses. The infection then makes its way down to the bronchi. ...

. He resolved to settle there and did so one year later, bringing his reluctant wife and his children, who arrived by train June 10, 1895. Within ten days of their arrival, Rutherford had opened a law office, purchased four lots of land, and contracted local builder Hugh McCurdy to build him a house. In July, the family moved into their new four-room single-storey house. In 1896 Rutherford became the town's only lawyer, as his competition, Mervyn Mackenzie, had moved to Toronto

Toronto ( , locally pronounced or ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, most populous city in Canada. It is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Ontario. With a p ...

.

Rutherford quickly became deeply involved in the community. Among the roles he acquired during his first three years in the District of Alberta were president of the newly formed South Edmonton Football Club, secretary-treasurer of the South Edmonton School Board, president of the South Edmonton Athletic Association, vice president of the South Edmonton Literary Institute, auditor of the South Edmonton Agricultural Society, and worthy master of the Acacia Lodge, Ancient Free and Accepted Masons. He also became secretary of the Edmonton District Butter and Cheese Manufacturing Association. Rutherford also became involved in the provincial autonomy movement for the North-West Territories in 1896. He was an early advocate for the incorporation of South Edmonton, hitherto an

Rutherford quickly became deeply involved in the community. Among the roles he acquired during his first three years in the District of Alberta were president of the newly formed South Edmonton Football Club, secretary-treasurer of the South Edmonton School Board, president of the South Edmonton Athletic Association, vice president of the South Edmonton Literary Institute, auditor of the South Edmonton Agricultural Society, and worthy master of the Acacia Lodge, Ancient Free and Accepted Masons. He also became secretary of the Edmonton District Butter and Cheese Manufacturing Association. Rutherford also became involved in the provincial autonomy movement for the North-West Territories in 1896. He was an early advocate for the incorporation of South Edmonton, hitherto an unincorporated community

An unincorporated area is a parcel of land that is not governed by a local general-purpose municipal corporation. (At p. 178.) They may be governed or serviced by an encompassing unit (such as a county) or another branch of the state (such as th ...

. When incorporation came in 1899, as the Town of Strathcona, Rutherford became the new town's secretary-treasurer after he had acted as returning officer in its first election.

Throughout that period, he practised law, from 1899 with Frederick C. Jamieson, who later was elected as a Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

member of the Legislative Assembly of Alberta

The Legislative Assembly of Alberta is the deliberative assembly of the province of Alberta, Canada. It sits in the Alberta Legislature Building in Edmonton. Since 2012 the Legislative Assembly has had 87 members, elected first past the post f ...

. He employed single women as secretaries in an era that clerical workers were predominantly male, and he defended a First Nations person accused of murder when most lawyers refused such cases. As their practice grew, he and Jamieson also engaged in moneylending

In finance, a loan is the tender of money by one party to another with an agreement to pay it back. The recipient, or borrower, incurs a debt and is usually required to pay interest for the use of the money.

The document evidencing the debt ( ...

. Besides his law practice, Rutherford was a successful real estate investor, and he also owned an interest in gold mining

Gold mining is the extraction of gold by mining.

Historically, mining gold from Alluvium, alluvial deposits used manual separation processes, such as gold panning. The expansion of gold mining to ores that are not on the surface has led to mor ...

equipment on the North Saskatchewan River

The North Saskatchewan River is a glacier-fed river that flows from the Canadian Rockies continental divide east to central Saskatchewan, where it joins with the South Saskatchewan River to make up the Saskatchewan River. Its water flows event ...

. Several parks and neighbourhoods in the city, including Bonnie Doon (originally spelt "Bonnie Doone"), were created from land owned by Rutherford.

Early political career

In 1896, Frank Oliver, who had representedEdmonton

Edmonton is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Alberta. It is situated on the North Saskatchewan River and is the centre of the Edmonton Metropolitan Region, which is surrounded by Central Alberta ...

in the Legislative Assembly of the Northwest Territories

The Northwest Territories Legislative Assembly, or Legislative Council of the Northwest Territories (with Northwest hyphenated as North-West until 1906), is the legislature and the seat of government of Northwest Territories in Canada. It is a u ...

since 1888, resigned to pursue a career in federal politics. Several Strathcona residents urged Rutherford to run for Oliver's old seat in the ensuing by-election. Though he was originally reluctant, he agreed to stand after a 300-signature petition

A petition is a request to do something, most commonly addressed to a government official or public entity. Petitions to a deity are a form of prayer called supplication.

In the colloquial sense, a petition is a document addressed to an officia ...

urging his candidacy was presented to him. His only opponent was a former mayor of Edmonton

This is a list of mayors of Edmonton, a city in Alberta, Canada.

Edmonton was incorporated as a town on January 9, 1892, with Matthew McCauley acclaimed as its first mayor during the town's first election, held February 10, 1892. On October ...

, Matthew McCauley, who, like Rutherford, ran as an independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in Pennsylvania, United States

* Independentes (English: Independents), a Portuguese artist ...

. Rutherford campaigned on a platform of improved roads, resource development, simplification of territorial ordinances, and (in what would become a theme of his political career) increased educational funding. McCauley won the election, but Rutherford received more than forty per cent of the vote.

During the 1898 territorial election, Rutherford again challenged the now-incumbent McCauley. His defeat of two years previous still fresh in his mind, his platform this time included a call for a redrawing of the territory's electoral boundaries. He believed that the current Edmonton riding was

During the 1898 territorial election, Rutherford again challenged the now-incumbent McCauley. His defeat of two years previous still fresh in his mind, his platform this time included a call for a redrawing of the territory's electoral boundaries. He believed that the current Edmonton riding was gerrymander

Gerrymandering, ( , originally ) defined in the contexts of Representative democracy, representative electoral systems, is the political manipulation of Boundary delimitation, electoral district boundaries to advantage a Political party, pa ...

ed in McCauley's favour. He also repeated his past calls for improved roads and advocated increased taxation on the railroads. He pledged "independent support" for the nonpartisan administration of Premier Frederick Haultain, and he supported that administration's call for the creation of a single province in the southern part of NWT following the 1901 census. Rutherford criticized McCauley's past record, accusing him of silence on issues that were of concern to his constituents. Despite this, McCauley won again but by a reduced margin.

Rutherford was at last successful in the 1902 election, when he ran in the newly created riding of Strathcona. His 1902 platform was similar to his 1898 platform and supported Haultain, but he now supported a two-province division of the southern part of the Northwest Territories

The Northwest Territories is a federal Provinces and territories of Canada, territory of Canada. At a land area of approximately and a 2021 census population of 41,070, it is the second-largest and the most populous of Provinces and territorie ...

, rather than Haultain's preferred one-province approach, on the grounds that a single province covering all the western prairies would be so large as to be ungovernable. It at first looked as though he would run unopposed; however, at the last minute, local lawyer Nelson D. Mills, a prominent Conservative, publicly accused Rutherford of being not a true independent, but a dyed-in-the-wool Haultain supporter, and announced that he would run against him. Rutherford was supported by most of Strathcona's most prominent residents, including his law partner Jamieson and his future rival John R. Boyle, and won an easy victory.

Rutherford served in the Legislative Assembly of the Northwest Territories until Alberta became a province in 1905. During his tenure, he was elected deputy speaker and sat on standing committees for libraries, municipal law, and education. His legislative efforts included successful attempts to extend the boundaries of the Town of Strathcona and to empower it to borrow for construction of public works. He was considered a possible member of Haultain's executive council, likely in the post of Commissioner of Public Works, but the post instead went to George Bulyea. He joined many of his fellow MLAs in continuing to advocate for provincial status, finding that the limitations on a territory's means to raise revenue prevented the Northwest Territories from meeting its obligations.

Though Rutherford supported Haultain's vision of nonpartisan territorial administration, federally he was an avowed Liberal. In 1900, he was elected president of the Strathcona Liberal association, and was a delegate to the convention that nominated Oliver as the party's candidate in Alberta

Alberta is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Canada. It is a part of Western Canada and is one of the three Canadian Prairies, prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to its west, Saskatchewan to its east, t ...

for the 1900 federal election. He subsequently campaigned for Oliver in his successful re-election attempt. When the new federal constituency of Strathcona was formed in advance of the 1904 election, Rutherford was urged to accept the Liberal nomination but demurred. Peter Talbot was selected instead and, supported by Rutherford, was elected.

Selection as premier

In February 1905, the federal government of

In February 1905, the federal government of Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

Sir Wilfrid Laurier

Sir Henri Charles Wilfrid Laurier (November 20, 1841 – February 17, 1919) was a Canadian lawyer, statesman, and Liberal politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Canada from 1896 to 1911. The first French Canadians, French ...

introduced legislation to create two new provinces (Alberta

Alberta is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Canada. It is a part of Western Canada and is one of the three Canadian Prairies, prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to its west, Saskatchewan to its east, t ...

and Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Western Canada. It is bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and to the south by the ...

) out of part of the Northwest Territories. Though Haultain wanted the new provinces to be governed on the same nonpartisan basis as the Territories had been, the Liberal Laurier was expected to recommend a Liberal to serve as Lieutenant-Governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a " second-in-com ...

, and the Lieutenant-Governor was expected to call on a Liberal to form the new province's first government. Oliver was the province's most prominent Liberal, but he had just been named federal Minister of the Interior and was not interested in leaving Ottawa. Talbot was Laurier's preferred candidate, but he expected to be appointed to the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

and found the latter prospect more congenial than serving as Premier of Alberta. Both men supported Rutherford, but neither was enthusiastic about doing so. In August, Bulyea was appointed Alberta's first Lieutenant-Governor and later that month the Alberta Liberals selected Rutherford as their first leader.

A final barrier was removed a few days later, when Haultain, who was a Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

federally but who was thought to be a potential leader of a coalition government

A coalition government, or coalition cabinet, is a government by political parties that enter into a power-sharing arrangement of the executive. Coalition governments usually occur when no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an ...

, announced that he would stay in Regina to lead the Saskatchewan Conservatives. On September 2, Bulyea asked Rutherford to form the first government of Alberta.

After accepting the position of premier, Rutherford selected a geographically diverse cabinet on September 6: Edmonton

Edmonton is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Alberta. It is situated on the North Saskatchewan River and is the centre of the Edmonton Metropolitan Region, which is surrounded by Central Alberta ...

's Charles Wilson Cross as Attorney-General, Calgary

Calgary () is a major city in the Canadian province of Alberta. As of 2021, the city proper had a population of 1,306,784 and a metropolitan population of 1,481,806 making it the third-largest city and fifth-largest metropolitan area in C ...

's William Henry Cushing

William Henry Cushing (August 21, 1852 – January 25, 1934) was a Canadian politician. Born in Ontario, he migrated west as a young adult where he started a successful lumber company and later became Alberta's first Minister of Public Works an ...

as Minister of Public Works, Medicine Hat

Medicine Hat is a city in Southern Alberta, southeast Alberta, Canada. It is located along the South Saskatchewan River. It is approximately east of Lethbridge and southeast of Calgary. This city and the adjacent Town of Redcliff, Alberta, R ...

's William Finlay as Minister of Agriculture and Provincial Secretary, and Lethbridge

Lethbridge ( ) is a city in the province of Alberta, Canada. With a population of 106,550 in the 2023 Alberta municipal censuses, 2023 municipal census, Lethbridge became the fourth Alberta city to surpass 100,000 people. The nearby Canadian ...

's George DeVeber as Minister without Portfolio. Rutherford kept for himself the positions of Provincial Treasurer and Minister of Education.

Premier

1905 election

Rutherford was now premier but had not yet faced the people in an election and did not yet have a legislature to which he could propose legislation. Elections for the first Legislative Assembly of Alberta were accordingly fixed for November 9. TheConservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

, the young province's only other political party, had already selected R. B. Bennett as their leader. Bennett attacked the terms under which Alberta had been made a province, especially the clauses that left control of its lands and natural resources in the hands of the federal government and required the continued provincial funding of separate schools. He pointed out that Canada's older provinces had control of their own natural resources and that education was a provincial responsibility under the British North America Act

The British North America Acts, 1867–1975, are a series of acts of Parliament that were at the core of the Constitution of Canada. Most were enacted by the Parliament of the United Kingdom and some by the Parliament of Canada. Some of the a ...

. The Liberals responded to such criticisms by highlighting the financial compensation the province received from the federal government in exchange for control of its natural resources, which amounted to $375,000 per year. They further suggested that the Conservatives' concern for control of lands to be caused by desire to make favourable land concessions to the unpopular Canadian Pacific Railway

The Canadian Pacific Railway () , also known simply as CPR or Canadian Pacific and formerly as CP Rail (1968–1996), is a Canadian Class I railway incorporated in 1881. The railway is owned by Canadian Pacific Kansas City, Canadian Pacific Ka ...

, which had long been friendly with the Conservatives and for which Bennett had acted as solicitor.

patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, art patronage refers to the support that princes, popes, and other wealthy and influential people ...

, and the election's result was never really in doubt. Before the election, Talbot predicted that the government would win 18 of the province's 25 seats. Immediately after the election, it appeared that the Liberals had won 21. When all the votes had been counted, the Liberals won 23 seats to the Conservatives' two. Bennett himself was defeated in his Calgary riding. When the outcome was clear, the people of Strathcona feted Rutherford with a torchlight procession and bonfire.

First legislature and regional tensions

One of the most contentious issues facing the newly elected government was the decision of the province's capital city. The federal legislation creating the province had fixedEdmonton

Edmonton is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Alberta. It is situated on the North Saskatchewan River and is the centre of the Edmonton Metropolitan Region, which is surrounded by Central Alberta ...

as the provisional capital, much to the chagrin of Calgary

Calgary () is a major city in the Canadian province of Alberta. As of 2021, the city proper had a population of 1,306,784 and a metropolitan population of 1,481,806 making it the third-largest city and fifth-largest metropolitan area in C ...

. Neither party had taken a position on the divisive question during the campaign, but selecting a permanent capital was high on the list of the new legislature's orders of business. Calgary's case was made most enthusiastically by Minister of Public Works Cushing, Edmonton's by Attorney-General Cross. Banff and Red Deer

The red deer (''Cervus elaphus'') is one of the largest deer species. A male red deer is called a stag or Hart (deer), hart, and a female is called a doe or hind. The red deer inhabits most of Europe, the Caucasus Mountains region, Anatolia, Ir ...

were also possibilities, but motions to select each failed to find seconders. In the end, Edmonton was designated by a vote of sixteen members, including Rutherford, to eight.

A personal priority of Rutherford had been the establishment of a university. Though the '' Edmonton Bulletin'' opined that it would be unfair "that the people of the Province should be taxed for the special benefit of four per cent that they may be able to attach the cognomen of B.A. or M.A. to their names and flaunt the vanity of such over the taxpayer, who has to pay for it," Rutherford proceeded quickly. He was concerned that delay might result in the creation of denominational colleges, striking a blow to his dream of a high-quality nonsectarian system of postsecondary education. A bill establishing the university was passed by the legislature but left the government to decide the location. Calgary felt that having lost the fight to be provincial capital, it could expect the university to be established there, and it was not pleased when, a year late the government announced the founding of the University of Alberta

The University of Alberta (also known as U of A or UAlberta, ) is a public research university located in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. It was founded in 1908 by Alexander Cameron Rutherford, the first premier of Alberta, and Henry Marshall Tory, t ...

in Rutherford's hometown, Strathcona.

While the regionally-charged issues attracted much attention, they were far from the government's only initiatives during the legislature's first session. In 1906, it passed a series of acts dealing with the organization and administration of the new provincial government and incorporated the cities of

While the regionally-charged issues attracted much attention, they were far from the government's only initiatives during the legislature's first session. In 1906, it passed a series of acts dealing with the organization and administration of the new provincial government and incorporated the cities of Lethbridge

Lethbridge ( ) is a city in the province of Alberta, Canada. With a population of 106,550 in the 2023 Alberta municipal censuses, 2023 municipal census, Lethbridge became the fourth Alberta city to surpass 100,000 people. The nearby Canadian ...

, Medicine Hat

Medicine Hat is a city in Southern Alberta, southeast Alberta, Canada. It is located along the South Saskatchewan River. It is approximately east of Lethbridge and southeast of Calgary. This city and the adjacent Town of Redcliff, Alberta, R ...

, and Wetaskiwin

Wetaskiwin ( ) is a city in the province of Alberta, Canada. The city is located south of the provincial capital of Edmonton. The city name comes from the Cree word , meaning "the hills where peace was made".

Wetaskiwin is home to the Reyn ...

. It also established a speed limit

Speed limits on road traffic, as used in most countries, set the legal maximum speed at which vehicles may travel on a given stretch of road. Speed limits are generally indicated on a traffic sign reflecting the maximum permitted speed, express ...

of for motorized vehicles and set up a regime for mine inspection. Perhaps most significantly, it set up a court system, with Arthur Lewis Sifton as the province's first Chief Justice.

Though the founding of the University of Alberta was the centrepiece of Rutherford's educational policy, his activity as Minister of Education extended well beyond it. In the first year of Alberta's existence, 140 new schools were established, and a normal school was set up in Calgary to train teachers. Rutherford put great emphasis on the creation of English-language schools in the large portions of the province that were occupied primarily by Central and Eastern European immigrants. The immigrants themselves were often unable to speak English, and the provision of these schools for their children was a major factor in their rapid assimilation into Albertan society. They were also in lieu of separate religious schools for groups such as Mennonites

Mennonites are a group of Anabaptism, Anabaptist Christianity, Christian communities tracing their roots to the epoch of the Radical Reformation. The name ''Mennonites'' is derived from the cleric Menno Simons (1496–1561) of Friesland, part of ...

. While the continued existence of Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

separate schools was mandated by the terms of Alberta's admission into Confederation, the government's policy was otherwise to encourage a unified and secular public school system. Rutherford also introduced free school texts in the province but was criticized for commissioning the texts from a Toronto

Toronto ( , locally pronounced or ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, most populous city in Canada. It is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Ontario. With a p ...

publisher, which printed them in New York, rather than locally.

Labour unrest

The winter of 1906–07 was the coldest in Alberta's history and was exacerbated by a shortage of coal. One cause of this shortage was the strained relationship between coal miners and mine operators in the province. At the beginning of April 1907, the Canada West Coal and Coke Company locked out the miners from its mine near Taber. The same company was also facing a work stoppage at its mine in the Crow's Nest Pass, where miners were refusing to sign a new contract. The problem spread until by April 22, all 3,400 miners working for member-companies of the Western Coal Operators' Association were off work. Miners' demands included increased wages, a reduction in working hours to eight per day (from ten), the posting of mine inspection reports, the isolated storage of explosives, the use of non-freezing explosives, and semi-monthly rather than monthly pay. The mine operators objected to this last point on the basis that since many miners did not report to work the day after payday, it desirable to keep paydays to a minimum. Rutherford's government appointed a commission in February, but it was not until May that it met. It consisted of Chief Justice Arthur Sifton, mining executive Lewis Stockett, and miners' union executive William Haysom. It began taking evidence in July. In the meantime, a May agreement saw most miners return to work at increased rates of pay. Coal supply promptly increased, as did its price. In August, the commission released its recommendations, which included a prohibition on children under 16 working in mines, the posting of inspectors' reports, mandatory bath houses at mine sites, and improved ventilation inspection. It also recommended for Albertans to keep a supply of coal on hand during the summer for winter use. The commission was silent on wages (other than to say that these should not be fixed by legislation), the operation of

Rutherford's government appointed a commission in February, but it was not until May that it met. It consisted of Chief Justice Arthur Sifton, mining executive Lewis Stockett, and miners' union executive William Haysom. It began taking evidence in July. In the meantime, a May agreement saw most miners return to work at increased rates of pay. Coal supply promptly increased, as did its price. In August, the commission released its recommendations, which included a prohibition on children under 16 working in mines, the posting of inspectors' reports, mandatory bath houses at mine sites, and improved ventilation inspection. It also recommended for Albertans to keep a supply of coal on hand during the summer for winter use. The commission was silent on wages (other than to say that these should not be fixed by legislation), the operation of company store

A company store is a retail store selling a limited range of food, clothing and daily necessities to employees of a company. It is typical of a company town in a remote area where virtually everyone is employed by one firm, such as a coal mine. In ...

s (a sore point among the miners), and the incorporation of miners' unions, which was recommended by mine management but opposed by the unions.

The committee also made no recommendation about working hours, but Rutherford's government legislated an eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses of working time.

The modern movement originated i ...

anyway. As well, Rutherford's government also passed workers' compensation

Workers' compensation or workers' comp is a form of insurance providing wage replacement and medical benefits to employees injured in the course of employment in exchange for mandatory relinquishment of the employee's right to sue his or her emp ...

legislation designed to make such compensation automatic, rather than requiring the injured worker to sue his employer. Labour representatives criticized the bill for failing to impose fines on negligent employers, for limiting construction workers' eligibility under the program to injuries sustained while they were working on buildings more than high, and for exempting casual labourers. It also viewed the maximum payout of $1,500 as inadequate. In response to these concerns, the maximum was increased to $1,800 and the minimum building height reduced to . In response to farmers' concerns, farm labourers were made exempt from the bill entirely.

Rutherford's relationship with organized labour was never easy. Historian L.G. Thomas argued that there was little indication that Rutherford had any interest in courting the labour vote. In 1908, Labour candidate Donald McNabb was elected in a Lethbridge

Lethbridge ( ) is a city in the province of Alberta, Canada. With a population of 106,550 in the 2023 Alberta municipal censuses, 2023 municipal census, Lethbridge became the fourth Alberta city to surpass 100,000 people. The nearby Canadian ...

by-election; the riding had previously been held by a Liberal. McNabb was the first Labour MLA elected in Alberta (he was defeated in his 1909 re-election bid).

Public works

Rutherford's Liberals self-identified as the party of free enterprise, in contrast to the Conservatives, who supported public ownership Still the Liberals made a limited number of large-scale forays into government operation of utilities, the most notable of which being the creation ofAlberta Government Telephones

Alberta Government Telephones (AGT) was the telephone provider in most of Alberta from 1906 to 1991.

AGT was formed by the Liberal Party of Alberta, Liberal government of Alexander Cameron Rutherford in 1906Wilson, Kevin G., Deregulating Teleco ...

. In 1906, Alberta's municipalities legislation was passed and included a provision authorizing municipalities to operate telephone companies. Several, including Edmonton, did so, alongside private companies. The largest private company was the Bell Telephone Company

The Bell Telephone Company was the initial corporate entity from which the Bell System originated to build a continental conglomerate and monopoly in telecommunication services in the United States and Canada.

The company was organized in Bost ...

, which held a monopoly over service in Calgary. Such monopolies and the private firms' refusal to extend their services into sparsely-populated and unprofitable rural areas aroused demand for provincial entry into the market, which was effected in 1907. The government constructed a number of lines, beginning with one between Calgary and Banff, and it also purchased Bell's lines for $675,000.

Alberta's public telephone system was financed by debt, which was unusual for a government like Rutherford's, which was generally committed to the principle of " pay as you go". Rutherford's stated rationale was that the cost of such a large capital project should not.be borne by a single generation and that incurring debt to finance a corresponding asset was, in contrast to operating deficits, acceptable. Though the move was popular at the time, it would prove not to be financially astute. By focusing on areas neglected by existing companies, the government was entering into the most expensive and least profitable fields of telecommunication. Such problems would not come to fruition until Rutherford had left office, however. In the short term, the government's involvement in the telephone business helped it to a sweeping victory in the 1909 election. The Liberals won 37 of 41 seats in the newly expanded legislature.

Of equal profile was Rutherford's government's management of the province's railways. Alberta's early years were optimistic and manifested itself in a pronounced enthusiasm for the construction of new railway lines. Every town wanted to be a railway centre, and the government had great confidence in the ability of the free market to provide low freight rates to the province's farmers if sufficient charters were issued to competing companies. The legislature passed government-sponsored legislation setting out a framework for new railways in 1907, but interest from private firms in actually building the lines was limited.

In the face of public demand and support by legislators of all parties for as rapid as possible an expansion of the province's lines, the government offered loan guarantees to several companies in exchange for commitments to build lines. Rutherford justified this in part by his conviction that railways needed to expand along with population, rather than have railway expansion follow population growth, which would be the case without government intervention. The Conservatives argued that the strategy did not go far enough, and they called for direct government ownership.

While most public works issues were handled by Public Works Minister Cushing, but after the 1909 election, Rutherford named himself as the province's first Minister of Railways.

While most public works issues were handled by Public Works Minister Cushing, but after the 1909 election, Rutherford named himself as the province's first Minister of Railways.

Railway scandal

When the legislature met for the first time after the 1909 election, things seemed to be going well for Rutherford and his government. He controlled a huge majority, albeit slightly reduced from the 1905 election, and enjoyed widespread popularity. His government had achieved significant success in setting up a new province, and success looked poised to continue. Early in this new legislative session, however, two signs of trouble appeared: Liberal backbencher John R. Boyle began to ask questions about the agreement between the government and the Alberta and Great Waterways Railway Company, and Cushing resigned from cabinet over his views of this same agreement. The Alberta and Great Waterways Railway was one of several companies that had been granted charters and assistance by the legislature to build new railways in the province. The government support that it received was more generous than that received by the more established railways, such as theGrand Trunk Pacific Railway

The Grand Trunk Pacific Railway was a historic Canadian transcontinental railway running from Fort William, Ontario (now Thunder Bay) to Prince Rupert, British Columbia, a Pacific coast port. East of Winnipeg the line continued as the National ...

and the Canadian Northern Railway

The Canadian Northern Railway (CNoR) was a historic Canada, Canadian transcontinental railway. At its 1923 merger into the Canadian National Railway , the CNoR owned a main line between Quebec City and Vancouver via Ottawa, Winnipeg, and Edmonto ...

. Boyle, Cushing, and Bennett alleged favouritism or ineptitude by Rutherford and his government, and they pointed to the sale of government-guaranteed bonds in support of the company as further evidence. Because of the high interest rate they paid, the bonds were sold at above par value

In finance and accounting, par value means stated value or face value of a financial instrument. Expressions derived from this term include at par (at the par value), over par (over par value) and under par (under par value).

Bonds

A bond selli ...

, but the government received only par for them and left the company to pocket the difference.

Boyle sponsored a motion of non-confidence

A motion or vote of no confidence (or the inverse, a motion or vote of confidence) is a motion and corresponding vote thereon in a deliberative assembly (usually a legislative body) as to whether an officer (typically an executive) is deemed fit ...

against the government. Despite enjoying the support of twelve Liberals, including Cushing, the motion was defeated and the government upheld. Rutherford attempted to quell the controversy by calling a royal commission

A royal commission is a major ad-hoc formal public inquiry into a defined issue in some monarchies. They have been held in the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Norway, Malaysia, Mauritius and Saudi Arabia. In republics an equi ...

, but pressure from many Liberals, including Bulyea, led him to resign May 26, 1910. He was replaced by Arthur Sifton, hitherto the province's chief judge.

In November, the royal commission issued its report that found that the evidence did not show a conflict of interest

A conflict of interest (COI) is a situation in which a person or organization is involved in multiple wikt:interest#Noun, interests, financial or otherwise, and serving one interest could involve working against another. Typically, this relates t ...

on Rutherford's part, but the majority report was nevertheless highly critical of the former premier. A minority report was much kinder by avowing perfect satisfaction with Rutherford's version of events.

Later life

Later political career

Before the 1911 federal election, several local Liberals opposed to Frank Oliver asked Rutherford to run against him in Strathcona. Relations between Oliver and Rutherford had always been chilly. Oliver was implacably opposed to Cross and viewed him as a rival for dominance of the Liberal Party in Alberta, and his ''Edmonton Bulletin'' had taken the side of the dissidents during the railway scandal. A nominating meeting unanimously nominated Rutherford as Liberal candidate, but Oliver refused to accept its legitimacy and awaited a later meeting. Before the meeting came to pass, however, Rutherford abruptly withdrew. Historian Douglas Babcock suggested that to be caused by the Conservatives' nomination of William Antrobus Griesbach, dashing Rutherford's hopes that his popularity among Conservatives would preclude them from opposing him. Rumours at the time alleged that Rutherford had been asked to make a personal contribution of $15,000 to his campaign fund and had balked. Rutherford himself cited a desire to avoid splitting the vote on reciprocity, which he and Oliver both favoured but Griesbach opposed. Whatever the reason for Rutherford's standing aloof from the election, Oliver was nominated as Liberal candidate and was re-elected. After resigning as premier, Rutherford continued to sit as a Liberal MLA. He commanded the loyalty of many Liberals who had supported his government through the Alberta and Great Waterways issue, but the faction began increasingly to see Cross as its real leader. Rutherford opposed the Sifton government's decision to confiscate the Alberta and Great Waterways bond money and revoke its charter, and in 1913, he was one of only two Liberals to support a non-confidence motion against the government (Cross had by now joined the Sifton cabinet, which placated most members of the Cross-Rutherford faction. In the 1913 election, Rutherford was again nominated as the Liberal candidate in Edmonton South (Strathcona had been amalgamated into Edmonton in 1912), despite pledging opposition to the Sifton government and offering to campaign around the province for the Conservatives if they agreed not to run a candidate against him. At the nomination meeting, he stated that he was "not running as a Sifton candidate" and was "a good independent candidate ... and a good Liberal too". Despite his opposition to the government, Conservatives declined his offer of support and nominated Herbert Crawford to run against him. After a vigorous campaign, Crawford defeated Rutherford by fewer than 250 votes. Cross lobbied Prime Minister Laurier for Rutherford to be appointed to theSenate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

. He was unsuccessful, but Rutherford was made King's Counsel

A King's Counsel (Post-nominal letters, post-nominal initials KC) is a senior lawyer appointed by the monarch (or their Viceroy, viceregal representative) of some Commonwealth realms as a "Counsel learned in the law". When the reigning monarc ...

shortly after his electoral defeat.

Rutherford took a strong line against the Sifton government and was nominated as Conservative candidate for the 1917 provincial election but stood down after being named as Alberta director of the National Service (conscription). (EB, November 6, 1916)

In the 1921 Alberta general election

The 1921 Alberta general election was held on July 18, 1921, to elect members to the 5th Alberta Legislative Assembly. The Liberal government is replaced by the United Farmers of Alberta. It was one of only five times that Alberta has changed gov ...

, he campaigned actively for the Conservatives, including for Crawford, who had defeated him eight years earlier. Rutherford continued to call himself a Liberal but criticized the incumbent administration for the growth of the provincial debt and for letting the party fall into disarray. Calling the Charles Stewart government "rotten" and holding a grudge against cabinet minister John R. Boyle in particular, he offered voters the slogan "get rid of the barnacles and the Boyles", a homonymic reference to the parasitic growth on the side of a ship. He may have been thrilled to see the Liberal government fall in the election but probably less so when he saw that the triumphant United Farmers of Alberta

The United Farmers of Alberta (UFA) is an association of Alberta farmers that has served different roles in its 100-year history – as a lobby group, a successful political party, and as a farm-supply retail chain. As a political party, it forme ...

had also whittled the Conservatives down to only one seat.

Professional career

Once out of politics, Rutherford returned to his law practice. His partnership with Jamieson saw partners come and go. Rutherford divided his time between the original Strathcona office and the Edmonton office that he opened in 1910. His practice focused on contracts, real estate, wills and estates, and incorporations. In 1923, Rutherford's son Cecil joined the firm, along with Stanley Harwood McCuaig, who, in 1919, would marry Rutherford's daughter Hazel. In 1925, Jamieson left the partnership to establish his own firm. In 1939, McCuaig did the same. Cecil's partnership with his father continued until the latter's death. Besides his work as a lawyer, Alexander Rutherford was involved in a number of business enterprises. He was President of the Edmonton Mortgage Corporation and Vice President and solicitor of the Great Western Garment Company. The latter enterprise, which Rutherford co-founded, was a great success: established in 1911 with eight seamstresses, it had quadrupled in size within a year. During the

Besides his work as a lawyer, Alexander Rutherford was involved in a number of business enterprises. He was President of the Edmonton Mortgage Corporation and Vice President and solicitor of the Great Western Garment Company. The latter enterprise, which Rutherford co-founded, was a great success: established in 1911 with eight seamstresses, it had quadrupled in size within a year. During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, it made military uniforms and was reputed to be the largest garment operation in the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

. It was acquired by Levi Strauss & Co. in 1961 but continued to manufacture garments in Edmonton until 2004.

Rutherford also acted as director of the Canada National Fire Insurance Company, the Imperial Canadian Trust Company, the Great West Permanent Loan Company, and the Monarch Life Assurance Company.

University of Alberta

Education was a personal priority of Rutherford, as evidenced by his retention of the office of Education Minister for his entire time as Premier and by his enthusiastic work in founding theUniversity of Alberta

The University of Alberta (also known as U of A or UAlberta, ) is a public research university located in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. It was founded in 1908 by Alexander Cameron Rutherford, the first premier of Alberta, and Henry Marshall Tory, t ...

. In March 1911, he was elected by Alberta's university graduates to the University of Alberta Senate, responsible for the institution's academic affairs. In 1912, he established the Rutherford Gold Medal in English for the senior year honours English student with the highest standing; the prize still exists today as the Rutherford Memorial Medal in English. In 1912, with the university's first graduating class, Rutherford instituted a tradition of inviting convocating students to his house for tea; this tradition would last for 26 years.

Convocation was not the only reason that students visited Rutherford's home. He had a wealth of both knowledge and books on Canadian subjects and welcomed students to consult his private library. The library eventually expanded beyond the room in his mansion devoted to it, to encompass the house's den, maid's sitting room, and garage as well. After his death, the collection was donated and sold to the university's library system; it was described in 1967 as "still the most important rare collection in the library".

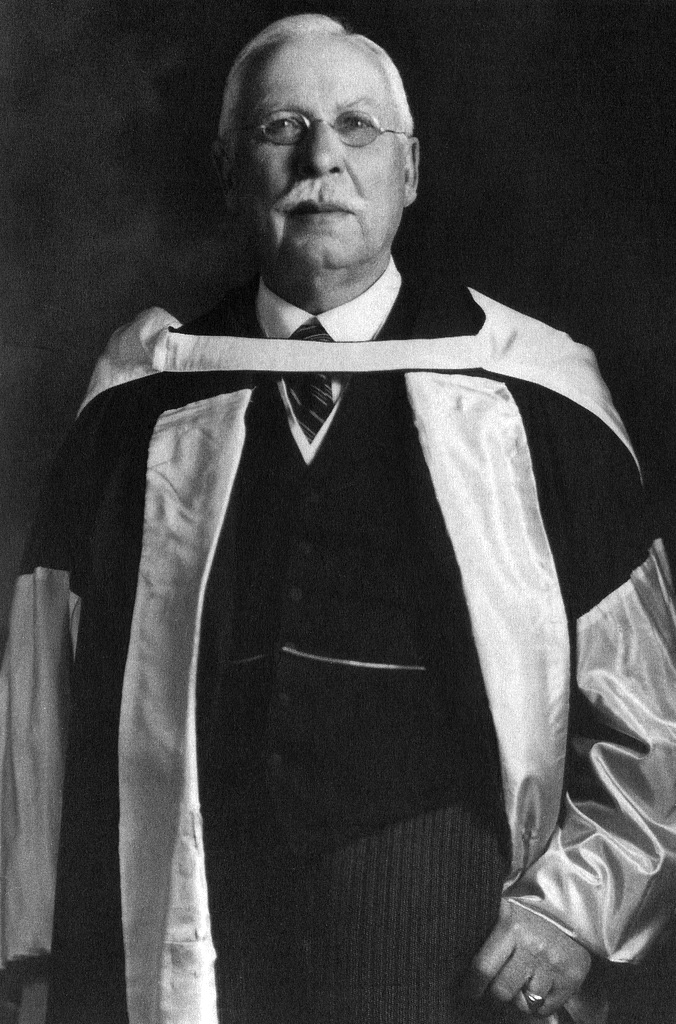

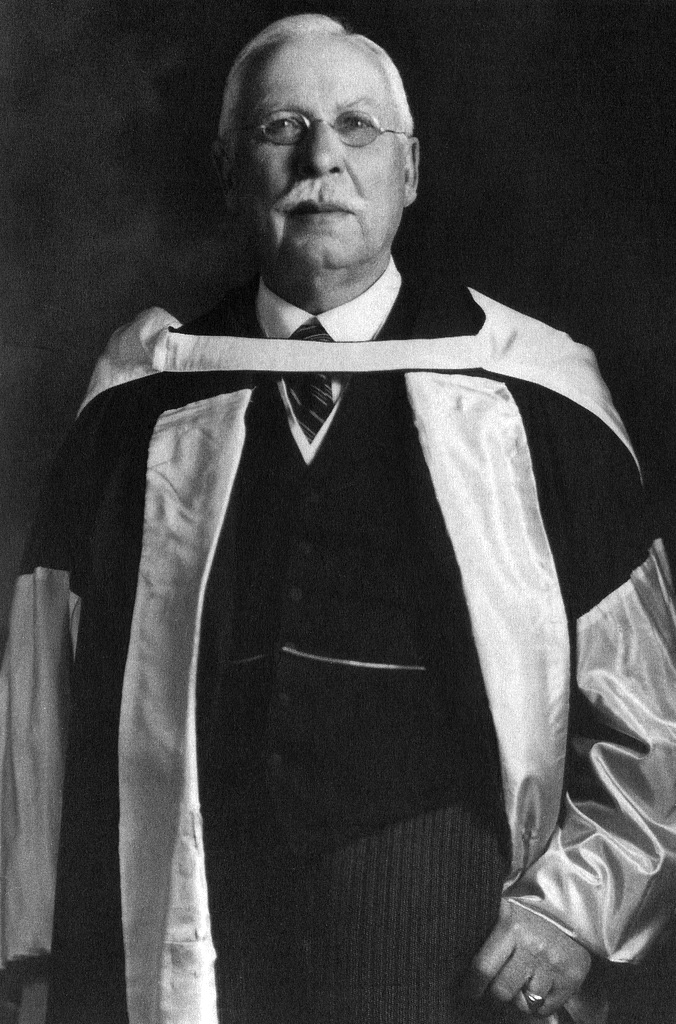

Rutherford remained on the university's senate until 1927, when he was elected

Convocation was not the only reason that students visited Rutherford's home. He had a wealth of both knowledge and books on Canadian subjects and welcomed students to consult his private library. The library eventually expanded beyond the room in his mansion devoted to it, to encompass the house's den, maid's sitting room, and garage as well. After his death, the collection was donated and sold to the university's library system; it was described in 1967 as "still the most important rare collection in the library".

Rutherford remained on the university's senate until 1927, when he was elected Chancellor

Chancellor () is a title of various official positions in the governments of many countries. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the (lattice work screens) of a basilica (court hall), which separa ...

. The position was the titular head of the university, and its primary duty was presiding over convocations. According to Rutherford biographer Douglas Babcock, it was the honour that Rutherford prized most. He was acclaimed to the position every four years until his death. It has been estimated that he awarded degrees to more than five thousand students. His final convocation, however, was marred by controversy. It 1941, a committee of the university senate recommended awarding an honorary degree to Premier William Aberhart

William Aberhart (December 30, 1878 – May 23, 1943), also known as "Bible Bill" for his radio sermons about the Bible, was a Canadian politician and the seventh premier of Alberta from 1935 to his death in 1943. He was the founder and first le ...

. Aberhart was pleased and happily accepted University President William Alexander Robb Kerr's invitation to deliver the commencement address at convocation. However, a week prior to convocation the full senate, responsible for all university academic affairs, met, and voted against awarding Aberhart a degree. Aberhart rescinded his acceptance of Kerr's invitation and later removed the senate's authority except, ironically, the authority to award honorary degrees and Kerr resigned in protest. Rutherford was mortified but presided over convocation nonetheless.

Community involvement and family life

Rutherford remained active in a wide range of community organizations well after his departure from politics. He was adeacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions.

Major Christian denominations, such as the Cathol ...

in his church until well into his dotage, was a member of the Young Women's Christian Association

The Young Women's Christian Association (YWCA) is a nonprofit organization with a focus on empowerment, leadership, and rights of women, young women, and girls in more than 100 countries.

The World office is currently based in Geneva, Swit ...

advisory board from 1913 until his death, was Edmonton's first exalted ruler of the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks

The Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks (BPOE), commonly known as the Elks Lodge or simply The Elks, is an American fraternal order and charitable organization founded in 1868 in New York City. Originally established as a social club for m ...

, and was for three years the grand exalted ruler of the Elk Order of Canada.

During World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, he was Alberta director of the National Service Commission, which oversaw conscription

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it conti ...

from 1916 until 1918, and in 1916, he was appointed Honorary Colonel of the 194th Highland Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force

The Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF; French: ''Corps expéditionnaire canadien'') was the expeditionary warfare, expeditionary field force of Canada during the First World War. It was formed on August 15, 1914, following United Kingdom declarat ...

. Rutherford served on the Loan Advisory Committee of the Soldier Settlement Board after the war, was President of the Alberta Historical Society (which had been created by his government) from 1919 to his death, was elected President of the McGill University Alumni Association of Alberta in 1922, and spent the last years of his life as honorary president of the Canadian Authors Association. He was also a member of the Northern Alberta Pioneers and Old-Timers Association, the British Association for the Advancement of Science, the Royal Colonial Institute of London, and the Masons.

He continued to play curling

Curling is a sport in which players slide #Curling stone, stones on a sheet of ice toward a target area that is segmented into four concentric circles. It is related to bowls, boules, and shuffleboard. Two teams, each with four players, take t ...

and tennis into his late fifties, and he took up golf at the age of sixty-four, becoming a charter member of the Mayfair Golf and Country Club.

In 1902, Rutherford obtained a lease for Lot 15 of Block B in Banff, Alberta

Banff is a resort town in Banff National Park, Alberta, Canada, in Alberta's Rockies along the Trans-Canada Highway, west of Calgary, east of Lake Louise, Alberta, Lake Louise, and above

Banff was the first municipality to incorporate within ...

for $15 per annum. In the spring of 1908, he hired J. Luckett to build his family a summer cottage on the lot. The cottage was a small eight-roomed cabin and water for the singular sink was provided via pipes from the Bow River. The cabin was not only for the use of the Rutherford family, but also family, friends, and faculty from the University of Alberta. The cabin was sold in December 1916 to Walter Huckvale, a wealthy rancher and politician, from Medicine Hat

Medicine Hat is a city in Southern Alberta, southeast Alberta, Canada. It is located along the South Saskatchewan River. It is approximately east of Lethbridge and southeast of Calgary. This city and the adjacent Town of Redcliff, Alberta, R ...

.

In 1911, the Rutherfords built a new house adjacent to the University of Alberta campus. Rutherford named it "Archnacarry", after his ancestral homeland in Scotland. Now known as Rutherford House, it serves as a museum. He made several trips to the United Kingdom and was invited to attend the

In 1911, the Rutherfords built a new house adjacent to the University of Alberta campus. Rutherford named it "Archnacarry", after his ancestral homeland in Scotland. Now known as Rutherford House, it serves as a museum. He made several trips to the United Kingdom and was invited to attend the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth

The coronation of the British monarch, coronation of George VI and his wife, Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, Elizabeth, as King of the United Kingdom, king and List of British royal consorts, queen of the United Kingdom and Commonwealth realm, ...

, but he had to return to Canada before the event. On December 19, 1938, the Rutherfords celebrated their fiftieth wedding anniversary

A wedding anniversary is the anniversary of the date that a wedding took place. Couples often mark the occasion by celebrating their relationship, either privately or with a larger party. Special celebrations and gifts are often given for partic ...

; tributes and well wishes arrived from across Canada.

Death and legacy

Besides hisbronchitis

Bronchitis is inflammation of the bronchi (large and medium-sized airways) in the lungs that causes coughing. Bronchitis usually begins as an infection in the nose, ears, throat, or sinuses. The infection then makes its way down to the bronchi. ...

, Rutherford developed diabetes

Diabetes mellitus, commonly known as diabetes, is a group of common endocrine diseases characterized by sustained high blood sugar levels. Diabetes is due to either the pancreas not producing enough of the hormone insulin, or the cells of th ...

in later years. His wife monitored his sugar intake, but when they were apart, Rutherford sometimes took less care than she would have liked him to. In 1938, possibly as a result of diabetes, he suffered a stroke that left him paralyzed and mute. He learned to walk again and, with the help of a grade 1 reader, got his speech back.

On September 13, 1940, Mattie Rutherford died of cancer. Less than a year later, June 11, 1941, Rutherford suffered a fatal heart attack while he was in hospital for insulin

Insulin (, from Latin ''insula'', 'island') is a peptide hormone produced by beta cells of the pancreatic islets encoded in humans by the insulin (''INS)'' gene. It is the main Anabolism, anabolic hormone of the body. It regulates the metabol ...

treatment. He was 84 years old. He was buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Edmonton, alongside his family.

Rutherford's policy legacy is mixed. L. G. Thomas concludes that he was a weak leader, unable to dominate the ambitions of his lieutenants and with very little skill at debate. Still, Thomas recognizes the Rutherford government's legacy of province building.

Douglas Babcock suggests that Rutherford, while himself honourable, left himself at the mercy of unscrupulous men who ultimately ruined his political career. Bennett, Rutherford's rival and later Prime Minister, concurred with this assessment, calling Rutherford "a gentleman of the old school ... not equipped by experience or temperament for the rough and tumble of western politics".

There is general agreement that Rutherford's greatest legacy and the one in which he took the most pride lies in his contributions to Alberta's education. As Mount Royal College